Abstract

In this study we aimed to investigate the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in psoriasis patients, and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated risk factors. A cross-sectional survey was conducted from February 2023 to March 2023. Information was obtained with online questionnaire about psoriasis patients on demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, SARS-CoV-2 infection and outcomes, vaccination, and routine protection against COVID-19. Logistic regression analysis was used to explore risk factors with SARS-CoV-2 infection and exacerbation of psoriasis. A total of 613 participants were recruited. 516 (84.2%) were infected, and associated factors were sex, working status, routine protection against COVID-19, COVID-19 vaccination, impaired nail, infection exacerbate psoriasis, and severity of psoriasis. Among the patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, 30 (5.8%) required hospitalization, 122 (23.6%) had psoriasis exacerbation due to SARS-CoV-2 infection, and associated factors were subtype of psoriasis, discontinuation of psoriasis treatment during SARS-CoV-2 infection, response following COVID-19 vaccination, and severity of psoriasis. Booster dose vaccination contributed a low probability of COVID-19 sequelae. COVID-19 vaccine’s effectiveness was unsatisfactory, while booster dose vaccination reduced the occurrence of COVID-19 sequelae in psoriasis patients of Southwest China. Patients treated with psoriasis shown to be safe, without a higher incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19hospitalization compared to untreated patients. Stopping treatment during SARS-CoV-2 infection led to psoriasis exacerbation, so psoriasis treatment could be continued except severe adverse reaction.

Subject terms: Infectious diseases, Skin diseases, Public health

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection1, threatened the lives and health of people worldwide. Chinese government took measures to quickly control the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic which started in late 2019, then adopted the dynamic zero-COVID policy to prevent another nationwide COVID-19 outbreak2. Due to the high transmissibility of the Omicron variant and symptoms caused by Omicron variant were mostly mild and asymptomatic3, full-dose of COVID-19 vaccination rate in Chinese population was close to 90%, so on December 7, 2022, Chinese government announced the end of the dynamic zero-COVID policy and no more infected patients would be with mandatory isolation control4. Subsequently, Chinese population was subjected to a massive wave of SARS-CoV-2 infection impact, with more than 80% of the population infected5. Despite this, no studies have been conducted to determine the status of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Chinese patients with psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory skin disease with systemic implication induced by a combination of genetic and environmental factors6. Psoriasis patients who received long-term therapy including biologics and systemic immunosuppressive medication treatment have an increased risk of infection7. Nevertheless, Kwee et al.8 found that biologics or non-biologics systemic therapy did not increase the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection. COVID-19 vaccine is an important tool against SARS-CoV-2 infection, with protection effectiveness as high as 95%9, but due to breakthrough infection with variants such as Omicron, vaccination with one or more doses only provide 24.7% of effective protection10. Regarding psoriasis patients treated with immunosuppressive medications, immunogenicity of the vaccine was impaired and antibody titers decreased11. Therefore, real-world studies are required to confirm the effectiveness of vaccine in psoriasis patients confronted with Omicron.

COVID-19 is characterized by excessive host immune response, a cytokine storm due to overproduction of various pro-inflammatory factors such as interleukins (IL) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), etc12, which are common targets for inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis13, systematic treatment for these diseases may play a role in COVID-19. Since infection was a trigger factor for psoriasis14, there have been case reports about exacerbation or new onset of psoriasis due to SARS-CoV-2 infection15,16, but research with large sample sizes and analysis of associated risk factors are lacking.

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and associated factors of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a real-world setting with psoriasis patients in Southwest China, investigate the factors associated with exacerbation of psoriasis due to SARS-CoV-2 infection, and explore whether psoriasis treatment modalities and vaccination had an impact on COVID-19 to address the above paradoxical issues.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey in psoriasis patients from three hospital’s dermatology departments of Southwest China through online questionnaire. Patients visiting dermatology clinic with a definitive diagnosis of psoriasis were recruited. Informed consents were collected before conducting the survey. Through the Wen-Juan-Xing platform (Changsha Ranxing Information Technology Co., Ltd., Hunan, China), the online survey was distributed and completed. The questionnaire was conducted between February 2023 and March 2023. All the participants could submit the questionnaire only once. Fully replied questionnaire was considered valid. This study was approved by the ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China (Ref no: K2023-080).

Questionnaires

The questionnaire included information about demographic and clinical characteristics of psoriasis, SARS-CoV-2 infection and prognosis, protection methods against Covid-19. The severity of psoriasis was self-assessed according to the area of skin lesions or body surface area (BSA), and BSA ≤ 3% was classified as mild psoriasis, BSA > 3% was moderate-to-severe psoriasis. According to China SARS-CoV-2 Infection Treatment Protocol (Trial 10th Edition)17, the followings were definite as SARS-CoV-2 infection: positive rapid antigen detection (RAD) test or positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test with or without COVID-19 symptoms; participants with COVID-19 symptoms and close contact history with confirmed cases, but did not undergo RAD test or PCR test. Denial of SARS-CoV-2 infection: negative PCR test or RAD test with or without symptoms related to respiratory infection. And other undefined cases. At present, there is no consensus on the definition of COVID-19 sequelae, according to the transition from strict quarantine policy to reopening at the specific period in China, we defined COVID-19 sequelae as persistent COVID-19 symptoms for more than four weeks in this study18.

Sample size

According to the estimated infection rate of SARS-CoV-2 in Guangzhou19, we presumed that 80% of the patients had been infected with SARS-CoV-2, and about 18 variables were used to explore the risk factors related to SARS-CoV-2 infection. A sample size of 10 times the number of variables was required in the multivariate regression analysis20, so 180 participants infected with SARS-CoV-2 were needed. Considering the actual infection rate may exceed 80%, so the minimum sample size was 180/0.8 = 22521.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Student T-test were applied to evaluate the difference between groups. If the continuous variables were not subject to normal distribution, the median (interquartile range) was used, and the difference of two groups were evaluated by Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables expressed as counts (percentage), compared using Pearson's chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. For multiple comparisons of chi-square test, pairwise chi-square test was performed by Bonferroni correction for P-value. Binary multivariate logistic regression was used to investigate the factors related to SARS-CoV-2 infection and the factors related to the exacerbation of psoriasis. Adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval were used to express the effect sizes. All data were analyzed with SPSS 26 (IBM, SPSS Statistics 26) and Graphpad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China (Ref no: K2023-080) and the study process was conducted in accordance with the committee's requirements. The research process complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consents were collected before conducting the survey.

Results

Baseline features

613 valid questionnaires were collected after removing ones with repeated filling and missing information. The mean values of age and BMI was 43.0 years, 24.1 kg/m2, 65.1% were male, 400(65.2%) had full-time or part-time job, 263(42.9%) were undergraduate or above, 404(65.9%) had unhealthy lifestyle habits. Psoriasis vulgaris was the majority type (84.2%, n = 516), and patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis accounted for 78.0% (n = 478). 63.8% of participants (n = 391) used biologics (Table 1). In case of prophylaxis of COVID-19, 508(82.9%) had routine protection. 568(92.7%) received vaccination, few parts of participants (13.5%, n = 83) had undergone deterioration of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination. Among the vaccinated group (n = 568), 274(48.2%) received booster dose vaccination. 516(84.2%) were infected with SARS-CoV-2, among them, the most common symptoms were fever (71.7%, n = 370), cough (56.4%, n = 291), and myalgia (41.7%, n = 215). Most participants (70.7%, n = 365) had COVID-19 symptoms for 7 days or less. 30 (5.8%) were hospitalized or required clinical treatment, 121 (23.4%) discontinued psoriasis treatment and 122(23.6%) had exacerbation of psoriasis due to SARS-CoV-2 infection, 136(26.4%) suffered from COVID-19 sequelae. Fatigue (13.8%, n = 71) and cough (7.2%, n = 37) were the most common symptoms of COVID-19 sequela (Table s1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of psoriasis participants.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 613) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 43.0 (32.0, 56.0) |

| Male | 399 (65.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 24.1 (21.8, 26.2) |

| Working status | |

| Not working* | 180 (29.4) |

| Full-time/part-time | 400 (65.2) |

| Student | 33 (5.4) |

| Education | |

| Middle school or below | 189 (30.8) |

| High school | 161 (26.3) |

| College or above | 263 (42.9) |

| Unhealthy lifestyle habit* | |

| Yes | 404 (65.9) |

| No | 209 (34.1) |

| Subtype of psoriasis | |

| Psoriasis vulgaris | 516 (84.2) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 81 (13.2) |

| Pustular psoriasis | 7 (1.1) |

| Erythrodermic psoriasis | 9 (1.5) |

| Course of psoriasis (years) | |

| ≤ 10 | 294 (48.0) |

| > 10 | 319 (52.0) |

| Severity of psoriasis* | |

| Mild | 135 (22.0) |

| Moderate to severe | 478 (78.0) |

| Psoriasis treatment | |

| Oral systemic treatment | 86 (14.0) |

| TCM* | 42 (48.8) [of 86] |

| TYK2* | 6 (7.0) [of 86] |

| Cyclosporin | 3 (3.5) [of 86] |

| Acitretin | 26 (30.2) [of 86] |

| Methotrexate | 8 (9.3) [of 86] |

| Glucocorticosteroid | 3 (3.5) [of 86] |

| Biological treatment | 391 (63.8) |

| Anti TNF-α | 31 (8.0) [of 391] |

| Anti IL-12/23 | 79 (20.2) [of 391] |

| Anti IL-23 | 33 (8.4) [of 391] |

| Anti IL-17 | 248 (63.4) [of 391] |

| Biologics used over 6 months | |

| Yes | 280 (71.6) [of 391] |

| No | 53 (13.6) [of 391] |

| Unclear | 58 (14.8) [of 391] |

| Non-systemic treatment | 97 (15.8) |

| Not receiving treatment | 39 (6.4) |

| Nail impairment | |

| Yes | 293 (47.8) |

| No | 320 (52.2) |

| Factors exacerbate psoriasis | |

| Mental stress | 45 (7.3) |

| Infectious factor | 77 (12.6) |

Values are presented as n (%) unless stated otherwise. BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range. Unhealthy lifestyle habit*: include smoking, alcohol consumption, bad diet, unlike exercising, poor sleep quality and others. Not working: include retired, unemployed, jobless. Severity of psoriasis*: mild, BSA (body surface area) ≤ 3%; moderate to severe, BSA > 3%. TCM*: Traditional Chinese Medicine; TYK2*: TYK2, tyrosine kinase 2; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-12/23, interleukin-12 and 23; IL-23, interleukin-23; IL-17, interleukin-17.

Psoriasis patients with and without SARS-CoV-2 infection

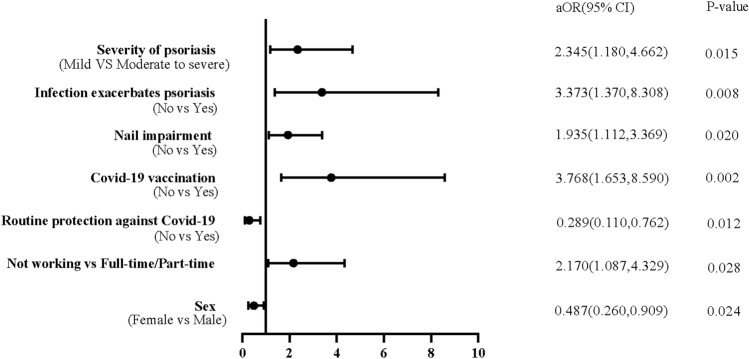

Significant differences of features between individuals with and without SARS-CoV-2 infection history were working status, severity of psoriasis, impaired nail, exacerbated psoriasis related to mental stress and infection, COVID-19 vaccination, and routine protection against COVID-19 (Table 2, s2, s3). The proportion of routine protection was higher among unvaccinated participants than vaccinated participants (93.3% vs 80.3%, p = 0.031) (Table s4).Adjusted logistic regression analysis was adopted to investigate the factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, it turned out male (aOR = 0.487; 95% CI 0.260–0.909), routine protection (aOR = 0.289; 95% CI 0.110–0.762), vaccination (aOR = 3.768; 95% CI 1.653–8.590), infection exacerbated psoriasis (aOR = 3.373; 95% CI 1.370–8.308), patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis (aOR = 2.345; 95% CI 1.180–4.662) were associated factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection, patients with full-time or part-time job were more likely be infected with SARS-CoV-2 than those who did not (aOR = 2.170; 95% CI 1.087–4.329), results shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of psoriasis Patients with clear SARS-CoV-2 infection status.

| Characteristic | SARS-CoV-2 infection (n = 516) | SARS-CoV-2 non-infection (n = 71) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtype of psoriasis | |||

| Psoriasis vulgaris | 438 (84.9) | 59 (83.1) | 0.695 |

| Other subtypes of psoriasis* | 78 (15.1) | 12 (16.9) | |

| Course of psoriasis, (years) | |||

| ≤ 10 | 240 (46.5) | 38 (53.5) | 0.267 |

| > 10 | 276 (54.5) | 33 (46.5) | |

| Severity of psoriasis* | |||

| Mild | 105 (20.3) | 22 (31.0) | 0.041 |

| Moderate to severe | 411 (79.7) | 49 (69.0) | |

| Nail impairment | |||

| Yes | 254 (49.2) | 26 (36.6) | 0.046 |

| No | 262(50.8) | 45 (63.4) | |

| Unhealthy lifestyle habits* | |||

| Yes | 334 (64.7) | 48 (67.6) | 0.634 |

| No | 182 (35.3) | 23 (32.4) | |

| Mental stress exacerbates psoriasis | |||

| Yes | 43 (8.3) | 1 (1.4) | 0.038 |

| No | 473 (91.7) | 70 (98.6) | |

| Infection exacerbates psoriasis | |||

| Yes | 130 (25.2) | 6 (8.5) | 0.002 |

| No | 386 (74.8) | 65 (91.5) | |

| Psoriasis treatment | |||

| Oral systemic treatment | 71 (13.8) | 8 (11.3) | 0.933 |

| Biological treatment | 330 (63.9) | 47 (66.2) | |

| Non-systemic treatment | 82 (15.9) | 12 (16.9) | |

| Not receiving treatment | 33 (6.4) | 4 (5.6) | |

| Biologics | |||

| Anti TNF-α | 23 (4.5) | 6 (8.5) | 0.129 |

| Anti IL-12/23 | 65 (12.6) | 13 (18.3) | |

| Anti IL-23 | 29 (5.6) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Anti IL-17 | 213 (41.3) | 27 (38.0) | |

| Oral systemic treatment | |||

| TCM* | 36 (7.0) | 3 (4.2) | 0.306 |

| TYK2* | 3 (0.6) | 2 (2.8) | |

| Cyclosporin | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Acitretin | 21 (4.1) | 3 (4.2) | |

| Methotrexate | 8 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Glucocorticosteroid | 4 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

Values are presented as n (%) unless stated otherwise. Other subtypes of psoriasis*: include Psoriasis Arthritis, Pustular Psoriasis, Erythrodermic Psoriasis. Severity of psoriasis*: mild, BSA (body surface area) ≤ 3%; moderate to severe, BSA > 3%. Unhealthy lifestyle habit*: include smoking, alcohol consumption, bad diet, unlike exercising, poor sleep quality and others. TCM*: Traditional Chinese Medicine; TYK2*: TYK2, tyrosine kinase 2; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-12/23, interleukin-12 and 23; IL-23, interleukin-23; IL-17, interleukin-17.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis: factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Factors | Unadjusted Model (Univariable analysis) | Adjusted Model (Multivariable analysis) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | aOR (95% CI) | Pa-value | |

| Age | 0.987 (0.970, 1.003) | 0.105 | 0.993 (0.971, 1.016) | 0.564 |

| BMI | 0.966 (0.907, 1.029) | 0.279 | 0.967 (0.904, 1.033) | 0.319 |

| Sex (Female vs Male) | 0.573 (0.326, 1.007) | 0.053 | 0.487 (0.260, 0.909) | 0.024 |

| Working Status | ||||

| Not working | Ref | Ref | ||

| Full-time/part-time | 1.878 (1.112, 3.170) | 0.018 | 2.170 (1.087, 4.329) | 0.028 |

| Student | 1.088 (0.387, 3.059) | 0.874 | 1.151 (0.265, 4.996) | 0.851 |

| Routine protection against COVID-19(No vs Yes) | 0.315 (0.124, 0.803) | 0.015 | 0.289 (0.110, 0.762) | 0.012 |

| COVID-19 Vaccination (No vs Yes) | 2.868 (1.371, 6.002) | 0.005 | 3.768 (1.653, 8.590) | 0.002 |

| Nail impairment (No vs Yes) | 1.678 (1.005, 2.802) | 0.048 | 1.935 (1.112, 3.369) | 0.020 |

| Infection exacerbates psoriasis (No vs Yes) | 3.649 (1.545, 8.618) | 0.003 | 3.373 (1.370, 8.308) | 0.008 |

| Mental stress exacerbates psoriasis (No vs Yes) | 6.364 (0.863, 46.948) | 0.070 | 5.075 (0.643, 40.028) | 0.123 |

| Psoriasis treatment | ||||

| Oral systemic treatment | Ref | Ref | ||

| Biological treatment | 0.791 (0.358, 1.747) | 0.562 | 0.630 (0.253, 1.569) | 0.321 |

| Non-systemic treatment | 0.770 (0.298, 1.990) | 0.589 | 0.721 (0.259, 2.006) | 0.531 |

| Not receiving treatment | 0.930 (0.261, 3.308) | 0.910 | 0.651 (0.166, 2.557) | 0.539 |

| Severity of psoriasis (Mild VS Moderate to severe) | 1.757 (1.017, 3.036) | 0.043 | 2.345 (1.180, 4.662) | 0.015 |

Adjustment variables: age, BMI, sex, working status, Routine protection against COVID-19, COVID-19 vaccination, nail impairment, infection exacerbates psoriasis, mental stress exacerbates psoriasis, psoriasis treatment, severity of psoriasis. OR, odds ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Forest plot for the multivariate regression analysis. In this figure, the position of the circles indicates the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for each significant factor, and the horizontal lines indicate the 95% CI associated with that value. Y coordinate of the corresponding calibration represents the significant factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. P-value of 0.05 or less are considered statistically significant.

Exacerbation of psoriasis due to SARS-CoV-2 infection

In univariate analysis on correlation of psoriasis exacerbation and SARS-CoV-2 infection, features significantly different between the groups were age, sex, working status, subtype and duration of psoriasis, mental stress exacerbates of psoriasis, treatment of psoriasis, biologics treatment, psoriasis treatment interrupted when COVID-19 infection, exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination (Table 4, s5, s6). Subsequently, we used adjusted logistic regression analysis, the results were shown in Table 5 and Fig. 2. Compared with other subtypes of psoriasis, psoriasis vulgaris was less likely to be aggregated (aOR = 0.452; 95% CI 0.247–0.826). Patients with discontinuation of anti-psoriasis treatment, flaring-up of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination and moderate-to-severe psoriasis were in risk of exacerbation of psoriasis under SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Table 4.

COVID-19 vaccination characteristics of psoriasis exacerbation due to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Characteristics | Exacerbation of psoriasis (n = 122) | Non-exacerbation of psoriasis (n = 394) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccination | |||

| Yes | 9 (7.4) | 22 (5.6) | 0.466 |

| No | 113 (92.6) | 372 (94.4) | |

| Dose of COVID-19 vaccination | |||

| 2-dose | 62 (50.8) | 221 (56.1) | 0.597 |

| 3-dose | 43 (35.2) | 136 (34.5) | |

| COVID-19 booster dose vaccination | |||

| Yes | 57 (46.7) | 172 (43.7) | 0.433 |

| No | 56 (45.9) | 200 (50.8) | |

| Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination | |||

| Yes | 34 (27.9) | 40 (10.2) | < 0.001 |

| No and unvaccinated | 88 (72.1) | 354 (89.8) | |

Values are presented as n (%) unless stated otherwise.

Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis: factors associated with exacerbation of psoriasis.

| Factors | Unadjusted model (Univariable analysis) | Adjusted model (Multivariable analysis) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | aOR (95% CI) | Pa-value | |

| Age | 0.980 (0.966, 0.994) | 0.006 | 0.985 (0.966, 1.005) | 0.146 |

| BMI | 0.965 (0.910, 1.023) | 0.232 | 0.997 (0.937, 1.061) | 0.921 |

| Sex (female vs male) | 0.621 (0.411, 0.938) | 0.024 | 0.876 (0.541, 1.416) | 0.588 |

| Working status | ||||

| Not working | Ref | Ref | ||

| Full-time/Part-time | 0.850 (0.537, 1.346) | 0.489 | 0.842 (0.464, 1.528) | 0.572 |

| Student | 2.892 (1.242, 6.736) | 0.014 | 2.602 (0.812, 8.336) | 0.107 |

| COVID-19 Vaccination (No vs Yes) | 0.743 (0.332, 1.658) | 0.468 | 0.610 (0.251, 1.484) | 0.276 |

| Other subtypes of Psoriasis vs Psoriasis vulgaris | 0.523 (0.311, 0.879) | 0.014 | 0.452 (0.247, 0.826) | 0.010 |

| Course of psoriasis (years)(≤ 10 vs > 10) | 0.643 (0.427, 0.967) | 0.034 | 0.828 (0.514, 1.334) | 0.438 |

| Mental stress exacerbates psoriasis (No vs Yes) | 2.292 (1.198, 4.384) | 0.012 | 1.444 (0.676, 3.084) | 0.343 |

| Psoriasis Treatment interruption (No vs Yes) | 3.159 (2.029, 4.920) | < 0.001 | 3.274 (2.011, 5.331) | < 0.001 |

| Response after COVID-19 vaccination (No response/Unvaccinated vs Psoriasis exacerbation) | 3.419 (2.046, 5.713) | < 0.001 | 2.788 (1.566, 4.964) | < 0.001 |

| Psoriasis treatment | ||||

| Oral systemic treatment | Ref | Ref | ||

| Biological treatment | 0.502 (0.285, 0.885) | 0.017 | 0.562 (0.292, 1.083) | 0.085 |

| Non-systemic treatment | 0.864 (0.434, 1.718) | 0.676 | 0.958 (0.444, 2.064) | 0.912 |

| Not receiving treatment | 1.043 (0.434, 2.511) | 0.924 | 1.071 (0.404, 2.842) | 0.890 |

| Severity of psoriasis (Mild VS Moderate to severe) | 1.131 (0.676, 1.893) | 0.639 | 1.866 (1.000, 3.479) | 0.050 |

Adjustment variables: age, BMI, sex, working status, COVID-19 vaccination, types of psoriasis, course of psoriasis, mental stress exacerbates psoriasis, psoriasis treatment interruption, response after COVID-19 vaccination, psoriasis treatment, severity of psoriasis. OR, odds ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the multivariate regression analysis. In this figure, the position of the circles indicates the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for each significant factor, and the horizontal lines indicate the 95% CI associated with that value. Y coordinate of the corresponding calibration represents the significant factors associated with psoriasis exacerbation. P-value of 0.05 or less are considered statistically significant.

SARS-CoV-2 infection in vaccinated psoriasis patients

In our cohort, the types of vaccines were mostly inactivated (2-dose) and recombinant protein (3-dose) vaccines. Vaccination was not an interfering factor in the course of COVID-19, COVID-19 hospitalization and the occurrence of COVID-19 sequelae (p > 0.05). Patients who received 2-dose of vaccine had lower probabilities of COVID-19 sequelae than those who received 3-dose (20.1% vs 33.5%, p = 0.001). Patients did not receive booster dose vaccine were more likely to have COVID-19 sequelae (p = 0.027) (Table s7–s9).

SARS-CoV-2 infection in psoriasis patients with psoriasis treatment

Among patients treated with all kinds of modalities and untreated patients, no difference in the duration of COVID-19, occurrence of sequelae or COVID-19 hospitalization (P > 0.05). In contrast, for biologics, different probability of COVID-19 sequelae occurrence correlated with certain biologics (p = 0.012), by pairwise comparisons, we concluded that the IL-23 inhibitor generated the lowest rate of COVID-19 sequelae compared to the other three biologics (p < 0.0083), which also had the advantage of preventing the deterioration of psoriasis (Table s10–s12).

Discussion

Since the end of the dynamic zero-COVID policy, the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in mainland China was skyrocketing during a short period. A large sample survey19 predicted that SARS-CoV-2 infection in mainland China would reach 80.7% on the 30th day after the shift of epidemic prevention policy, another regional study22 predicted the prevalence was 88.5%. Likewise, our study came to a close prediction, which suggests that Chinese psoriasis patients have a comparable incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection with the general population.

Previous study23 revealed risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection in the general population include advanced age, male gender, etc. In our study, females were more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection than males, however, it was still debatable whether gender affected SARS-CoV-2 infection24. SARS-CoV-2 enters the body through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), and expression level of ACE2 is higher in male than female, theoretically, male should be more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection25, whether there is modulation in ACE2 expression of both genders in patients with psoriasis? Further researches are needed to determine whether males with psoriasis are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Patients with impaired nail and moderate-to-severe psoriasis were more likely to be infected, since impaired nail often indicated severe cases of psoriasis26, suggesting that psoriasis severity is a predictor of infection risk7. Patients with severe psoriasis express high level of interferon (IFN)27, which in term promote the expression of ACE228, therefore have a higher risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2. Infection in general was an environmental factor in the exacerbation or triggering of psoriasis14, and patients who experienced exacerbation of psoriasis by infection were more likely to be contracted by SARS-CoV-2.

Our analysis came up with an interesting finding. We noticed that COVID-19 vaccine did not offer valid protection in Chinese psoriasis patients, instead it was associated with the occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 infection for possible reasons: (1) Breakthrough infection with the Omicron variant. Omicron was endemic in mainland China around the end of the dynamic zero-COVID policy29, it exhibited higher transmissibility and lower susceptibility to neutralizing antibodies induced by vaccine compared to the original strain3. At the same time, immunity stimulated by vaccine was waning over time30; (2) Lack of routine protection against COVID-19. In our cohort, ratio of routine protection was lower in vaccinated psoriasis patients than in unvaccinated patients. Our findings and previous studies31 have reached consensus routine protection against COVID-19 was a protective factor against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Therefore, we suggest that routine protection should not be neglected even under vaccinated status; (3) Low naturally acquired immunity. A study32 reported that naturally acquired immunity played more crucial roles in preventing infection than vaccination, while under the previous dynamic zero-COVID policy, the general infection rate in China was at a low level, and herd immunity in Chinese population was far from robust compared with other countries33; (4) Whether psoriasis patients were suitable for COVID-19 vaccination remains controversial. No unified conclusion on whether COVID-19 vaccine in psoriasis patients could stimulate valid specific immunity, especially in patients receiving long-term immunosuppressive therapy with impaired humoral response to the vaccine34, who constituted the majority of our cohort.

The pathogenesis of psoriasis has not been fully elucidated. Until now, the general research supports that the IL-23/T-helper cell type 17 (Th17) axis dominates the inflammation activation process, and various cytokines such as IL-17, TNF, and IL-12 are involved13, which intersects with the pro-inflammatory factors induced by SARS-CoV-235. Aram et al.15 summarized case reports of psoriasis exacerbation due to SARS-CoV-2 infection, but did not investigate factors associated with exacerbation of psoriasis. In our study, patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis were more prone to undergo exacerbation, which might due to the fact that they bear a stronger basic inflammatory process27, and when SARS-CoV-2 superimposed, it further ignited the inflammation process. Discontinuation of treatment can lead to recurrence or exacerbation of psoriasis36. Tissue-resident memory (TRM) T cells are involved in the recurrence of psoriasis after treatment discontinuation. TRM cells can be divided into CD4+ and CD8+ subsets, which respectively promote the production of IL-22 and IL-17A, contribute to an inflammatory environment in localized tissues37. SARS-CoV-2 infection also caused exacerbation of psoriasis in patients who had exacerbated after previous COVID-19 vaccination, a review38 even reported new onset of psoriasis after COVID-19 vaccination. The mechanism might be vaccination activating of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, increasing levels of INF-γ, TNF-α, IL-2 and IL-1239.

Whether psoriasis patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy were at higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and prone to COVID-19 adverse events remains unsolved. A multicenter study40 based on 11,466 patients found an increased risk of infection in psoriasis patients under TNF inhibitor therapy. However, Liu et al.41 reported no difference in SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19 hospitalization in psoriasis patients using IL-17 inhibitor compared to non-biologic agents. In our study, psoriasis treatment modalities were not associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 hospitalization. Therefore, discontinuing psoriasis treatment is not recommended in the setting of SARS-CoV-2 infection except in the case of a severe COVID-19 event, and active treatment of psoriasis is beneficial in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection and preventing exacerbation of psoriasis due to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Although our results indicated that COVID-19 vaccination (including booster dose) in little help in prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection or reduction of COVID-19 hospitalization. Booster dose vaccination did reduce the incidence of COVID-19 sequelae, the result was similar to a meta-analysis42 by Gao. Therefore, booster dose vaccination is recommended.

This is the pioneer study concerning impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on psoriasis after the end of dynamic zero-COVID policy in mainland China, in real-world examining effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccine in psoriasis population with low naturally acquired immunity, and answering the linkage between psoriasis treatment and COVID-19-related events. We also explored the risk factors for exacerbation of psoriasis due to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Because of the high variability of the SARS-CoV-2, another large-scale impact on psoriasis patients is still possible, the findings of our work may contribute to the exploration of psoriasis and SARS-CoV-2 related issues.

There are some limitations of this study. First, regarding the screening of participants, in order to best simulate the situation of SARS-CoV-2 infection at that time, and the limitation of PCR testing and lack of antigen detection kits, we lowered the criteria for confirming SARS-CoV-2 infection to screen as many SARS-CoV-2 infection as possible, which may lead to an increase in the false positive rate. Secondly, despite the fact that the research included three hospitals and some patients were spread throughout many provinces in Southwest China, the majority of them were concentrated in one area. Because some of the patients were elderly and not sure what kind of vaccine they had received, so we did not explore the association between specific vaccine subtypes and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Furthermore, the authenticity of the data may be limited by questionnaires, as psoriasis severity was based on patients' own assessment of BSA. Except that, this survey was completed online, and there might be a selective bias due to the low participation rate of geriatric and pediatric patients.

Conclusion

We found that SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with COVID-19 vaccination, while booster dose vaccination assisted in lowering the incidence of COVID-19 sequelae. Other major SARS-CoV-2 infection risk factors were female gender, employed individuals, lack of routine protection, severe cases of psoriasis. Associated factors for psoriasis exacerbation were subtypes of psoriasis, response following COVID-19 vaccination, severity of psoriasis, discontinuation of psoriasis treatment. Psoriasis treatment was unrelated to SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 hospitalization, biologics proved safety during SARS-COV-2 infection.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ying Chen for her effort in this study.

Author contributions

Y.Z., J.X. and P.W. participated in generating the data for the study and reviewed the pertinent raw data on which the results and conclusions of this study are based; Y.Z. and P.W. wrote the main manuscript text. A.C., K.H., S.Z., J.L., J.H. and J-Z.L. participated in the analysis of the data. J.X. and Y.F. participated in the language editing. Y.P. and C.L. participated in gathering and generating the data for the study. P.W. have reviewed the pertinent raw data on which the results and conclusions of this study are based. All the authors have approved the final version of this paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

National natural science foundation of China: grant number NSFC 82103733; Joint project of Chongqing Health Commission and Science and Technology Bureau: grant number 2022QNXM048.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yang Zou and Jing Xu.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-54424-y.

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burki T. Moving away from zero COVID in China. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023;11:132. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00508-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhama K, Nainu F, Frediansyah A, et al. Global emerging Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2: Impacts, challenges and strategies. J. Infect. Public Health. 2023;16:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Notice on further optimization of the implementation of measures for the prevention and control of the COVID-19 epidemic. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-12/07/content_5730443.htm (last accessed: 7 December 2022).

- 5.Chen JM, Gong HY, Chen RX, et al. Features and significance of the recent enormous COVID-19 epidemic in China. J. Med. Virol. 2023;95:e28616. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, Barker J. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeshita J, Shin DB, Ogdie A, Gelfand JM. Risk of serious infection, opportunistic infection, and herpes zoster among patients with psoriasis in the United Kingdom. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2018;138:1726–1735. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwee KV, Murk JL, Yin Q, et al. Prevalence, risk and severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections in psoriasis patients receiving conventional systemic, biologic or topical treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional cohort study (PsoCOVID) J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2023;34:2161297. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2161297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skowronski DM, De Serres G. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:1576–1577. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2036242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Z, Xu S, Liu J, et al. Effectiveness of inactivated COVID-19 vaccines among older adults in Shanghai: Retrospective cohort study. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:2009. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37673-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deepak P, Kim W, Paley MA, et al. Effect of immunosuppression on the immunogenicity of mRNA vaccines to SARS-CoV-2: A prospective cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021;174:1572–1585. doi: 10.7326/M21-1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Candia P, Prattichizzo F, Garavelli S, Matarese G. T cells: Warriors of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Trends Immunol. 2021;42:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:1475. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou S, Yao Z. Roles of infection in psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:6955. doi: 10.3390/ijms23136955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aram K, Patil A, Goldust M, Rajabi F. COVID-19 and exacerbation of dermatological diseases: A review of the available literature. Dermatol. Ther. 2021;34:e15113. doi: 10.1111/dth.15113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Essien F, Chastant L, McNulty C, Hubbard M, Lynette L, Carroll M. COVID-19-induced psoriatic arthritis: A case report. Ther. Adv. Chron. Dis. 2022;13:20406223221099333. doi: 10.1177/20406223221099333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.China SARS-CoV-2 Infection Treatment Protocol (Trial 10th edition). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/ylyjs/pqt/202301/32de5b2ff9bf4eaa88e75bdf7223a65a/files/02ec13aadff048ffae227593a6363ee8.pdf (last accessed: 9 January 2023).

- 18.Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, Young M, Edison P. Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:n1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang J, Zhao S, Chong KC, et al. Infection rate in Guangzhou after easing the zero-COVID policy: Seroprevalence results to ORF8 antigen. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023;23:403–404. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Q, Lv C, Han X, Shen M, Kuang Y. A web-based survey on factors for unvaccination and adverse reactions of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in Chinese patients with psoriasis. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021;14:6265–6273. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S341429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung K, Lau EHY, Wong CKH, Leung GM, Wu JT. Estimating the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BF.7 in Beijing after adjustment of the zero-COVID policy in November-December 2022. Nat. Med. 2022;29:579–582. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02212-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang JJ, Dong X, Liu GH, Gao YD. Risk and protective factors for COVID-19 morbidity, severity, and mortality. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023;64:90–107. doi: 10.1007/s12016-022-08921-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukherjee S, Pahan K. Is COVID-19 gender-sensitive? J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2021;16:38–47. doi: 10.1007/s11481-020-09974-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai H. Sex difference and smoking predisposition in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:e20. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30117-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long F, Zhang Z, He F, et al. Dermoscopic features of nail psoriasis: Positive correlation with the severity of psoriasis. J. Dermatol. 2021;48:894–901. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christophers E, van de Kerkhof PCM. Severity, heterogeneity and systemic inflammation in psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019;33:643–647. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziegler CGK, Allon SJ, Nyquist SK, et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell. 2020;181(1016–1035):e1019. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Branda F, Scarpa F, Ciccozzi M, Maruotti A. Is a new COVID-19 wave coming from China due to an unknown variant of concern? Keep calm and look at the data. J. Med. Virol. 2023;95:e28601. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mallapaty S. China’s COVID vaccines have been crucial—Now immunity is waning. Nature. 2021;598:398–399. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-02796-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsiang S, Allen D, Annan-Phan S, et al. The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature. 2020;584:262–267. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gazit S, Shlezinger R, Perez G, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) naturally acquired immunity versus vaccine-induced immunity, reinfections versus breakthrough infections: A retrospective cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022;75:e545–e551. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Lancet Regional Health-Western Pacific The end of zero-COVID-19 policy is not the end of COVID-19 for China. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 2023;30:100702. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liew SY, Tree T, Smith CH, Mahil SK. The impact of immune-modifying treatments for skin diseases on the immune response to COVID-19 vaccines: A narrative review. Curr. Dermatol. Rep. 2022;11:263–288. doi: 10.1007/s13671-022-00376-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elmas OF, Demirbas A, Kutlu O, et al. Psoriasis and COVID-19: A narrative review with treatment considerations. Dermatol. Ther. 2020;33:e13858. doi: 10.1111/dth.13858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yalici-Armagan B, Tabak GH, Dogan-Gunaydin S, Gulseren D, Akdogan N, Atakan N. Treatment of psoriasis with biologics in the early COVID-19 pandemic: A study examining patient attitudes toward the treatment and disease course. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021;20:3098–3102. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puig L, Costanzo A, Muñoz-Elías EJ, et al. The biological basis of disease recurrence in psoriasis: A historical perspective and current models. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022;186:773–781. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu PC, Huang IH, Wang CW, Tsai CC, Chung WH, Chen CB. New onset and exacerbations of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022;23:775–799. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00721-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahin U, Muik A, Derhovanessian E, et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and T(H)1 T cell responses. Nature. 2020;586:594–599. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2814-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: Results from the psoriasis longitudinal assessment and registry (PSOLAR) JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961–969. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu M, Wang H, Liu L, et al. Risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization and mortality in psoriasis patients treated with interleukin-17 inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1046352. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1046352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao P, Liu J, Liu M. Effect of COVID-19 vaccines on reducing the risk of long COVID in the real world: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:12422. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.