Abstract

Research background

The role of osteocytes in maintaining bone mass has been progressively emphasized. Pip5k1c is the most critical isoform among PIP5KIs, which can regulate cytoskeleton, biomembrane, and Ca2+ release of cells and participate in many processes, such as cell adhesion, differentiation, and apoptosis. However, its expression and function in osteocytes are still unclear.

Materials and methods

To determine the function of Pip5k1c in osteocytes, the expression of Pip5k1c in osteocytes was deleted by breeding the 10-kb mouse Dmp1-Cre transgenic mice with the Pip5k1cfl/fl mice. Bone histomorphometry, micro-computerized tomography analysis, immunofluorescence staining and western blotting were used to determine the effects of Pip5k1c loss on bone mass. In vitro, we explored the mechanism by siRNA knockdown of Pip5k1c in MLO-Y4 cells.

Results

Pip5k1c expression was decreased in osteocytes in senescent and osteoporotic tissues both in humans and mice. Loss of Pip5k1c in osteocytes led to a low bone mass in long bones and spines and impaired biomechanical properties in femur, without changes in calvariae. The loss of Pip5k1c resulted in the reduction of the protein level of type 1 collagen in tibiae and MLO-Y4 cells. Osteocyte Pip5k1c loss reduced the osteoblast and bone formation rate with high expression of sclerostin, impacting the osteoclast activities at the same time. Moreover, Pip5k1c loss in osteocytes reduced expression of focal adhesion proteins and promoted apoptosis.

Conclusion

Our studies demonstrate the critical role and mechanism of Pip5k1c in osteocytes in regulating bone remodeling.

The translational potential of this article

Osteocyte has been considered to a key role in regulating bone homeostasis. The present study has demonstrated that the significance of Pip5k1c in bone homeostasis by regulating the expression of collagen, sclerostin and focal adhesion expression, which provided a possible therapeutic target against human metabolic bone disease.

Keywords: Pip5k1c, Osteocyte, Sclerostin, Bone mass

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis has become a serious public health problem globally [[1], [2], [3]]. Furthermore, a cross-sectional study revealed that the age-standardized prevalence of osteoporosis was estimated to be 33.49 % in the middle-aged and elderly Chinese permanent residents [2]. Therefore, a better understanding of mechanisms behind bone mass regulation will provide new approaches to the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis [4]. Osteocytes are the most abundant cells in bone, occupying 90–95 % of the total cells in bone [5]. In recent years, increasing number of studies have shown that osteocytes, which were considered to be metabolically inactive, play a vital role in maintaining bone homeostasis [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. Osteocytes regulate surrounding cells by both intercellular signaling through dendrites and direct connections with osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and mesenchymal stem cells [13]. In addition, osteocytes can regulate bone remodeling by secreting a variety of soluble factors, such as sclerostin (Sost), receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL), osteoprotegerin (OPG) and other factors [14]. However, the upstream signaling pathways that modulate osteocyte function and thereby bone homeostasis remain to be incompletely elucidated.

PI(4,5)P2, as a plasma membrane marker [15], is one of the key players of cytoskeletal-PM adhesion [16]. It was reported that PI(4,5)P2 is critical for maintaining the intracellular content of PI(4,5)P2 [[17], [18], [19]], which is mainly generated by type I phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5 kinases (PIP5KIs) [20]. In mammals, there are three isoforms of Pip5k1 protein, including Pip5k1a, Pip5k1b, and Pip5k1c [[21], [22], [23], [24]]. Among them, Pip5k1c plays essential functions in regulating cytoskeleton [21,[25], [26], [27], [28]], biomembrane [21,[28], [29], [30], [31], [32]] and Ca2+ release [21,25] of cells, and participating in many processes such as cell polarity, phagocytosis [21,33], adhesion [25], migration [29,34], differentiation [31], and apoptosis [35]. In humans, a mutation in the PIP5K1C gene caused lethal contractural syndrome type 3 (LCCS3), which is characterized by multiple joint contractures with severe muscle atrophy and early death after birth for respiratory insufficiency [36,37]. In mice, alterations in Pip5k1c expression or activation cause a series of organ damage and dysfunction, such as tumor metastasis [[38], [39], [40], [41], [42]], neural dysfunction [22,43,44], immune system disorder [34,45], cardiac developmental abnormality [22] and obesity [46]. Wang YF et al. reported that the absence of Pip5k1c led to embryonic lethality [22]. Zhu et al. reported that optimal Pip5k1c expression is critical for maintaining osteoclast differentiation and function via regulating the PI(4,5)P2 generation [47]. Our previous study has established a crucial role of Pip5k1c in the protection against osteoarthritis in mice [48]. Besides, the involvements of Pip5k1c in Prx1-expressing mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been well documented. Pip5k1c loss in MSCs reduced bone formation by impairing the stability of Runx2 and RANKL-mediated osteoclast formation, leading to low turnover osteoporosis [49]. However, the role of Pip5k1c in osteocytes is not reported.

In this study, we demonstrate that loss of Pip5k1c expression in the Dmp1-expressing osteocytes leads to severe bone loss with impaired bone formation and bone resorption. Pip5k1c loss reduces the expression of type I collagen and several focak adhesion (FA) proteins, promotes sclerostin production in osteocytes and osteocyte apoptosis, consequently impairing bone mass and strength.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal studies

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Southern University of Science and Technology (No. SUSTC-JY2020119) approved the animal protocols of this study. The generation of Dmp1-Cre and Pip5k1cfl/fl mice was previously described [7,49]. The experimental animals in this study were obtained using a two-step breeding strategy. The primer sequences of genotyping are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

2.2. Human samples collection

The Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University approved the procedures performed in this study (NO. [2023]176). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Human cancellous tissues were collected from the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University. Samples were collected and fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde (PFA) as previously described [50].

2.3. Femur three-point bending

After dissected the encompassing soft tissue, the femurs were stored at 1 × PBS at once and followed by the three-point bending test using ElectroForce (Bose ElectroFore 3200; EndureTEC Minnetonka, MN, USA) as previously described [11].

2.4. Micro-computerized tomography analysis

Micro-computerized tomography (μCT) analysis was performed as a previously established protocol [51]. Briefly, non-demineralized spine, femur, tibia, or skull were fixed in 4 % PFA for 24 h and then analyzed by a Bruker μCT (SkyScan 1276, Bruker) following the standards recommended by the ASBMR [52].

2.5. Confocal imaging and two-photon imaging

Confocal images were conducted by Zeiss LSM 980. To investigate collagen fibers, second-harmonic generation (SHG) and two-photon excited fluorescence imaging were conducted by two-photon Olympus FVMPE-RS microscopy [12].

2.6. Histology and immunofluorescence staining

Human and mice bone tissues were fixed for 24 h using 4 % PFA, decalcified and embedded in paraffin using standard protocols [53]. For histology, 5-μm sections were used for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining and hematoxylin and eosin (H/E) as previously described [54]. For immunofluorescence (IF) staining, after antigen-retrieval by citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.0), sections were permeabilized with 0.2 % TritonX-100 solution for 10 min at room temperature (RT). After washing in 1 × PBS with 0.1 % Tween 20, the Immunol Staining Blocking Buffer (Beyotime, P0102) was used for blocking for 1 h at RT. Then the sections were incubated with indicated primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and matched secondary antibody 1 h at RT. Antibody information is listed in Supplementary Table 2.

2.7. Calcein double labeling

Mineral apposition rate (MAR) and bone formation rate (BFR) were measured as previously described [55]. Briefly, mice were injected intraperitoneally with calcein (20 mg/kg) on days 7 and 2 before sacrifice. After being fixed in 4 % PFA for 24 h and embedded by an Osteo-Bed Bone Embedding kit (EM0200; Sigma), the femurs were sectioned at 15 μm. After obtaining images by fluorescent microscopy (Olympus, BX53). The MAR and BFR were calculated following quantities: MAR = dL.Ar/dL.Pm/5 days; BFR = MAR × (dLS + sLS/2)/BS.

2.8. Western blotting analyses

Protein samples from tissue and cell were isolated, followed by the western blotting analyses as we previously described [7]. Briefly, total protein extracted from tissues or cells was lysed with RIPA buffer (Sigma–Aldrich; R0278) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 78440). Proteins were fractionated in SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Meck Millipore Ltd). After blocking in 5 % nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 buffer, the membranes were incubated with primary antibody (4 °C, overnight), followed by incubation with corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase; and detect the bands by the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Bio-Rad; 1705040). Antibody information is listed in Supplemental Table 2.

2.9. qRT-PCR analyses

qRT-PCR analyses were performed as previously described [56]. Briefly, total RNA was extracted by the MolPure Cell/Tissue Total RNA Kit (YEASEN, 19221ES50). After reverse transcription with Hifair Ⅱ 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (YEASEN, 11119ES60). qPCR reactions were set up in a 96-well format on the CFX 96 Touch using Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, 1725125). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

2.10. Serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The serum levels of procollagen type 1 amino-terminal propeptide (P1NP), sclerostin and type I collagen cross-linked c-terminal peptide (CTX-1) were measured using the serum from mice by the Rat/Mouse PINP EIA (Immunodiagnostic Systems Limited, AC-33F1), SOST/Sclerostin Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D, MSST00) and RatLapsTM (CTX-I) EIA (Immunodiagnostic Systems Limited, AC-06F1) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

2.11. TUNEL staining

The One Step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit (Red Fluorescence) (Beyotime, C1090) was used to evaluate the cell apoptosis as previously described [57].

2.12. In vitro siRNA knockdown experiments

Mouse MLO-Y4 osteocyte-like cells were cultured in α-MEM supplemented with 10 % FBS, 1 % penicillin and streptomycin. MLO-Y4 cells were transfected with Pip5k1c siRNA and negative control siRNA using a Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Invitrogen, 13778075) as previously described [49]. As for the control group, negative control siRNA was transfected. At 48 h after siRNA transfected, proteins were extracted, followed by western blotting analysis. The siRNA sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

2.13. Flow shear stress (FSS) experiments

Fluid-induced FSS was performed as previously described [58]. Briefly, Streamer ® System STR-4000 (Flexcell International Corporation, Burlington, NC, USA) was used for experiment. MLO-Y4 cells were seed on Collagen-I pre-coated culture slips with a total cell number of 3.0 × 105 cells for 24–48 h before FSS. During FSS treatment, the culture slips were put into a flow chamber and exposed to 10 dyne/cm2 flow for 2 h. Static control MLO-Y4 cells were kept in incubator without any force stimulation. Protein samples were extracted from MLO-Y4 cells right after FSS treatment.

2.14. Statistics

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Unpaired 2-tailed Student's t-test or 2-way ANOVA was used to evaluate significant differences in the comparison between two groups or multiple groups. Statistical analyses were completed using the Prism GraphPad. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

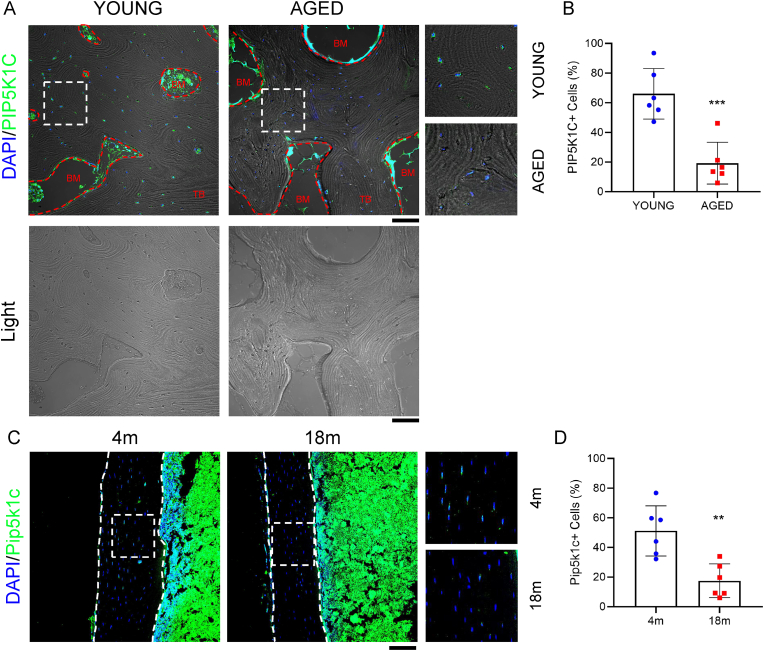

3.1. Pip5k1c expression is decreased in osteocytes in human osteoporotic bone and aged mouse bones

IF staining showed a dramatic reduction of PIP5K1C-positive cells in osteoporotic bone tissues from aged humans (66–80 years old) compared to those from young humans (27–43 years old) with normal bone mass (Fig. 1A–B). In addition, in C57bl/6 mice, the expression of Pip5k1c in osteocytes was significantly decreased in 18-month-old mice compared to 4-month-old mice (Fig. 1C–D).

Figure 1.

Pip5k1c expression is decreased in human osteoporostic and aged mouse bones. A, IF staining. Sections of cancellous samples from young and aged humans were subjected to IF staining with Pip5k1c antibody. Merge images (top) and brightfield images (bottom) were showed. White dashed boxes indicate the higher magnification images in the right panels. Bone tissue and bone marrow were labeled as trabecular bone (TB) and bone marrow (BM), with the borders delineated by a red dashed lines. Scale bars, 100 μm. B, Quantification of (A). C, IF staining. Sections of tibia samples from 4-month-old and 18-month-old male mice were subjected to IF staining with Pip5k1c antibody. White dashed boxes indicate the higher magnification images in the right panels. White dashed lines indicate the bone surfaces. Scale bars, 100 μm. N = 6 mice per group. D, Quantification of (C). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

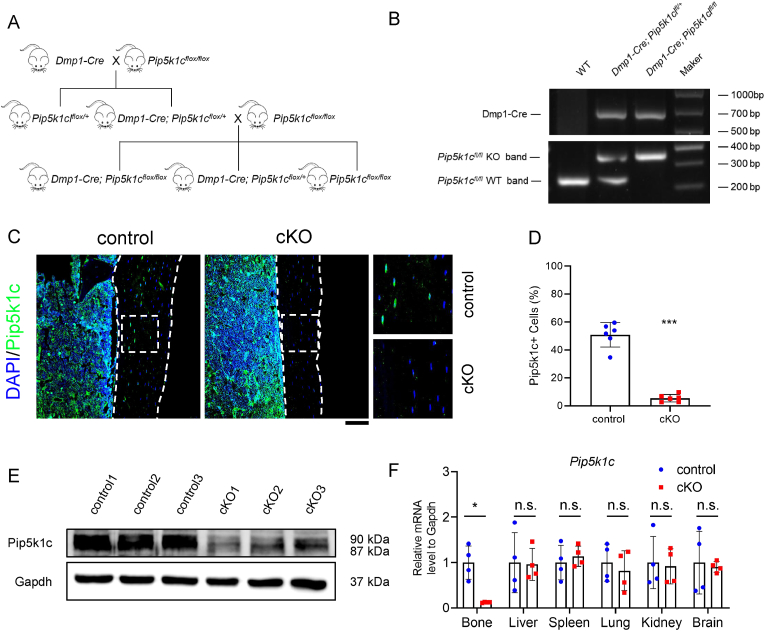

3.2. Generation of mice lacking Pip5k1c expression in osteocytes

To further investigate the role of Pip5k1c in bone, we deleted its expression in osteocytes by breeding the 10-kb mouse Dmp1-Cre transgenic mice with the Pip5k1cfl/fl mice (Dmp1-Cre; Pip5k1cfl/fl, referred as cKO hereafter) as the breeding strategy showed (Fig. 2A). PCR genotyping using mouse tail DNAs were used to confirm the deletion of Pip5k1c(Fig. 2B). IF staining (Fig. 2C–D) and western blotting analyses (Fig. 2E) showed the protein level of Pip5k1c was significantly reduced in cortical bones from cKO mice compared to that from control mice. In contrast to results from bones, the mRNA levels of Pip5k1c in the liver, spleen, lung, kidney and brain were consistent between the control and cKO group (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Genetic deletion of Pip5k1c in Dmp1-expressing osteocytes in adult mice. A, A schematic diagram of breading strategy. B, Genotyping. DNA was amplified by PCR and then subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis. Dmp1-Cre, ∼650bp; Pip5k1c flox KO band, ∼380bp; Pip5k1c flox wildtype (WT) band, ∼250bp. C, IF staining. Sections of cancellous samples from 5-month-old control and cKO male mice were subjected to IF staining with pip5k1c antibody. White dashed boxes indicate the higher magnification images in the right panels. White dashed lines indicate the bone surfaces. Scale bars: 100 μm. N = 6 mice per group. D, Quantification of (C). E, Western blot analysis. Protein samples extracted from the bone tissues of the control and cKO mice were subjected to western blot analyses with indicated antibodies. F, qPCR analyses. Total RNAs isolated from the indicated tissues of 3-month-old male control and cKO mice were used for qPCR analysis for expression of Pip5k1c gene, which was normalized to Gapdh mRNA. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). n.s.: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

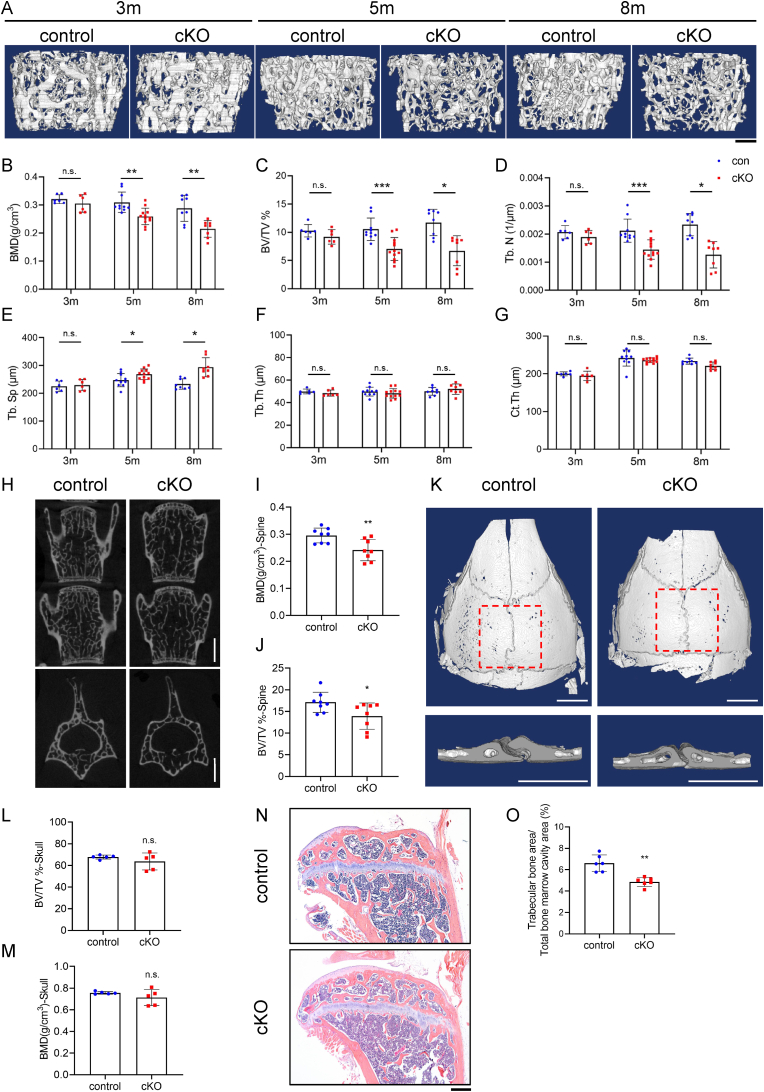

3.3. Pip5k1c loss in Dmp1-expressing osteocytes causes an osteopenic phenotype in mice

Τhe results of μCT analysis showed that Pip5k1c loss caused osteopenia in femurs from 5- and 8-month-old cKO male mice, but displayed no difference in 3-month-old between control and cKO group(Fig. 3A–G). Pip5k1c loss significantly decreased the bone mineral density (BMD) (Fig. 3A and B), bone volume fraction (BV/TV) (Fig. 3A, C) and trabecular number (Tb. N) (Fig. 3A, D) without affecting the trabecular thickness (Tb. Th) (Fig. 3A, F) and cortical thickness (Ct. Th) (Fig. 3G). The trabecular separation (Tb. Sp) (Fig. 3A, E) was increased in cKO mice compared to that in control mice. Similarly, BMD (Fig. 3H and I) and BV/TV (Fig. 3H, J) were also reduced in 8-month-old male cKO spine (L4-5) compared to those in control mice. However, there were no differences in bone mass of calvaria with Pip5k1c deletion or not(Fig. 3K-M). Consistent with the μCT analyses, cKO mice displayed less trabecular bone mass in tibia than that in control mice (Fig. 3N and O).

Figure 3.

Pip5k1c loss leads to low bone mass in long bone and spine bone. A, Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction from μCT scans of distal femurs from male control and cKO mice with the indicated ages. Scale bar, 250 μm. B-G, Quantitative analyses of BMD (B), BV/TV (C), Tb.N (D), Tb.Sp (E), Tb.Th (F), and Ct.Th (G) of femurs from control and cKO male mice with the indicated ages. H, 3D reconstruction from μCT scans of spine (L4, L5) from 8-month-old male control and cKO mice. Scale bar, 250 μm. I-J, Quantitative analyses of the BMD and BV/TV of spine from male control and cKO mice. N = 8 mice per group. K, 3D reconstruction from μCT scans of calvaria. L-M, Quantitative analyses of the BV/TV and BMD of calvaria from male control and cKO mice. N = 5 mice per group. N, H/E staining of tibial sections from 5-month-old male control and cKO mice. Scale bar, 200 μm. O, Quantitative analyses of the percentage of trabecular bone area in the total bone marrow cavity area. N = 6 mice per group. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). n.s.: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

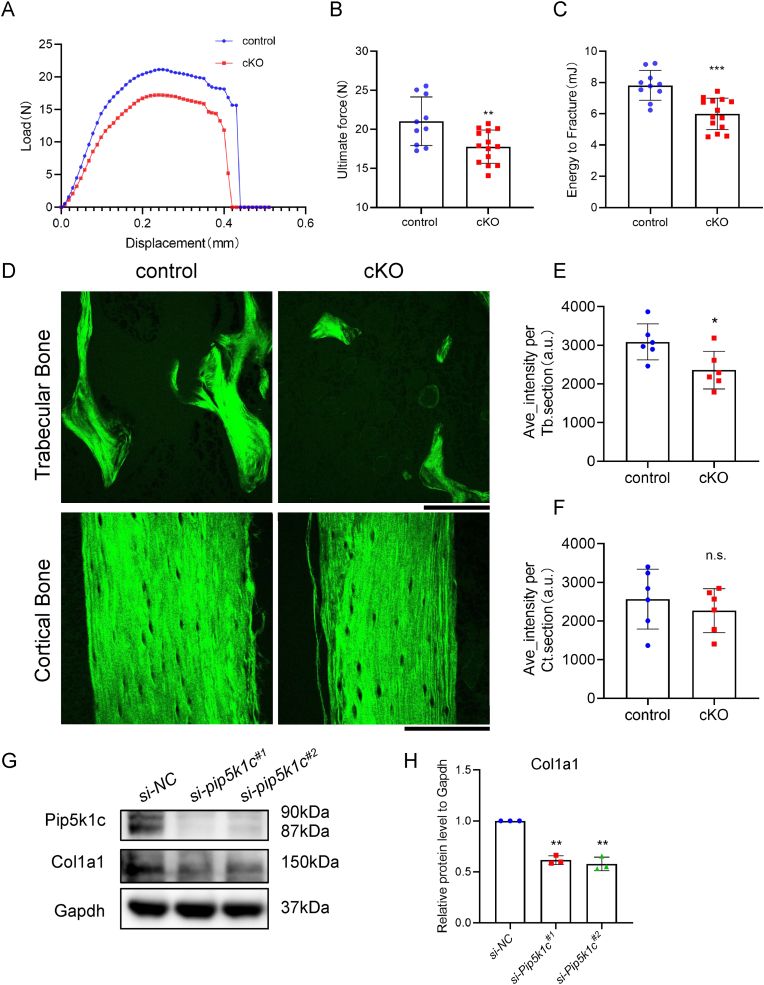

3.4. Pip5k1c loss causes decreased mechanical properties and collagen synthesis in long bones

We measured the mechanical properties of the femur by three-point-bending test, and as shown in the load–displacement curve, the femur of cKO mice could resist only a smaller bending force before fracture, accompanied by a shorter displacement of the force, compared to control mice (Fig. 4A and B). The average maximum load on the femur in the cKO group (17.77 ± 2.13 N) was lower than that in the control group (21.79 ± 3.90 N) (Fig. 4B). The energy-to-fracture for femurs was significantly lower in cKO mice (5.99 ± 1.00 mJ) than that in control mice (7.82 ± 0.96 mJ) (Fig. 4C). SHG microscopy with two-photon excited fluorescence imaging was used to detect visualize fibrillar collagen fibers. As shown in Fig. 4D, compared to the control group, the arbitrary intensity of fiber significantly decreased in the trabecular bone but not in cortical bone from 5-month-old cKO male mice (Fig. 4D–F). These results suggested that collagen 1 fibers were reduced in cKO tibia. Consistently, protein expression of type 1 collagen was detected after siRNA knockdown of Pip5k1c in MLO-Y4 cells (Fig. 4G and H).

Figure 4.

Pip5k1c loss in osteocytes decreases bone mechanical properties and collagen synthesis. A-C, Three-point-bending test. Representative load–displacement curve from 5-month-old male control and cKO mice (A). Quantitative analyses of ultimate force (B) and energy to fracture (C). N = 10 mice for control group and N = 14 for cKO group. D, Representative images of collagen fibers of trabecular bone and cortical bone in tibial sections under two-photon microscopy from 5-month-old control and cKO male mice. Scale bars, 100 μm. E-F, Quantitative analyses of collagen fiber intensity of trabecular bone (E) and cortical bone (F). N = 6 mice per group. G, Western blot analysis. Protein samples extracted from the MLO-Y4 cells were transfected with si-NC or si-Pip5k1c and subjected to western blot analyses with indicated antibodies. H, Relative protein levels of Col1a1 of (G). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). n.s.: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

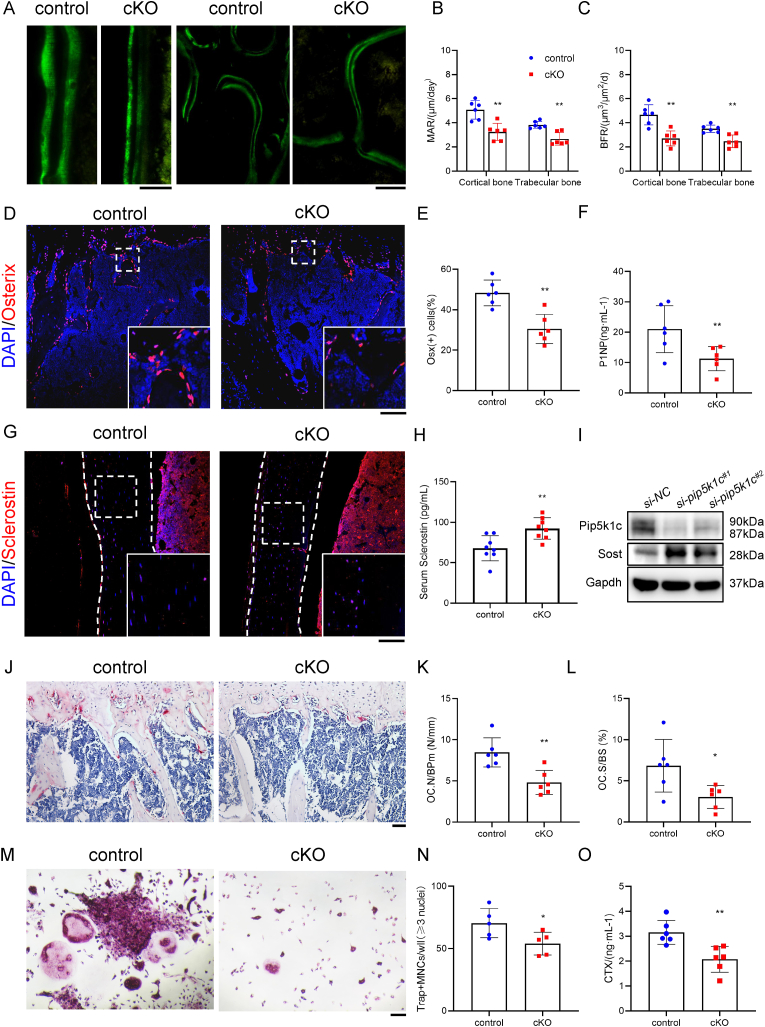

3.5. Pip5k1c loss mainly impairs bone formation and increases sclerostin expression

To further investigate the mechanism of osteopenia caused by Pip5k1c deficiency, we analyzed the bone formation and bone resorption in control and cKO mice. The calcein double-labeling experiment was used to determine bone formation, which showed that the MAR (Fig. 5A and B) and BFR (Fig. 5A, C) in both diaphyseal cortical bones and the femoral metaphyseal cancellous from cKO mice were significantly decreased, compared with those in control mice (Fig. 5A–C). Consistently, IF staining revealed that the percentage of osterix (Osx)-expressing cells on the surface of trabecular bone in the tibial epiphysis of mice was significantly reduced in cKO mice, compared to that in control mice (Fig. 5D and E). The serum level of the P1NP, a marker for osteoblast activity and bone formation, was significantly reduced in 5-month-old male cKO mice than that in age- and sex-matched control mice(Fig. 5F). The sclerostin protein expression was determined by IF staining and a significantly higher percentage of sclerostin-positive osteocytes were observed in cortical bone from 5-month-old male cKO mice. Meanwhile, the serum level of sclerostin was increased in 5-month-old male cKO mice, in comparison to that from the control mice (Fig. 5H). Moreover, Pip5k1c gene was knockdown by siRNA in MLO-Y4 cells increasing the expression of sclerostin (Fig. 5I).

Figure 5.

Pip5k1c loss in osteocytes regulates bone formation and bone resorption. A-C, Calcein double labeling. Representative images of 5-month-old control and cKO femur sections(A). Quantification of the MAR (B) and BFR (C) of trabecular bone and cortical bone. N = 6 mice per group. Scale bar, 50 μm. D, IF staining for expression of osterix of the tibial sections of 5-month-old control and cKO male mice. White dashed boxes indicate the higher magnification images in the bottom right panels. N = 6 mice per group. Scale bar, 100 μm. E, Quantification of (D). F, Serum levels of P1NP from 5-month-old control and cKO male mice. N = 6 mice per group. G, IF staining for expression of sclerostin of the tibial sections of 5-month-old control and cKO mice. White dashed boxes indicate the higher magnification images in the right panels. White dashed lines indicate the bone surfaces. N = 6 mice per group. Scale bar, 100 μm. H, Serum levels of sclerostin from 5-month-old control and cKO male mice. N = 8 mice per group. I, Western blot analysis. Protein samples extracted from the MLO-Y4 were transfected with si-NC or si-Pip5k1c and subjected to western blot analyses with indicated antibodies. J-L, TRAP staining of tibial sections from 5-month-old male mice. Quantitative analyses of Oc.N/BPm (K) and the Oc.S/BS (L) of primary spongiosa (PS) from (J). N = 6 mice per group. Scale bar, 50 μm. M, TRAP staining. BMMs from 5-month-old male control and cKO mice were cultured in osteoclast differentiation medium, followed by TRAP staining. N, Quantitative analyses of TRAP-positive MNCs with ≥3 nuclei per well of (M) were scored. N = 5 mice per group. Scale bar 50 μm. O, Serum level of CTX-1 from 5-month-old control and cKO mice. N = 6 mice per group. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

3.6. Pip5k1c loss reduces bone resorption

To further analyze the effect of Pip5k1c deletion on bone resorption, TRAP staining showed that osteoclast number/bone perimeter (OC.N/Bpm) (Fig. 5J and K) and the osteoclast surface/bone surface (OC.BS/BS) (Fig. 5J, L) in primary cancellous bone in cKO group were less than those in control group. In vitro, after isolated from mice, the primary bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMs) were induced osteoclastogenesis and fewer TRAP-positive multinucleated osteoclasts (MNCs, defined as three or more nuclei per cell) were observed in cKO group than control mice (Fig. 5M and N). Furthermore, results from ELISA assays showed a significant decrease in the serum level of CTX-1, an in vivo marker for bone resorption, in cKO mice (Fig. 5O).

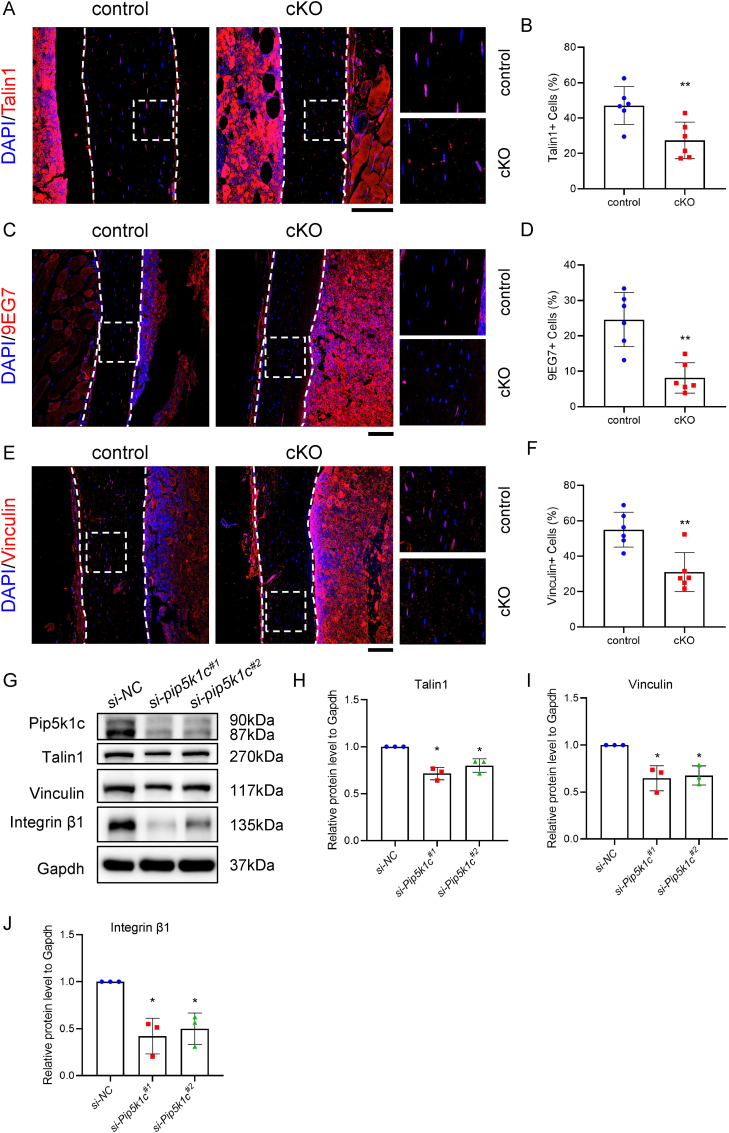

3.7. Pip5k1c loss in osteocytes reduces the expression levels of FA proteins in bones

It was reported that Pip5k1c plays an important role in controlling the FA formation [[59], [60], [61], [62]]. Meanwhile, some studies have revealed that the decrease of FA in osteocytes is related to osteoporosis [7,8,11,12]. Therefore, we determined whether Pip5k1c loss impacted the expressions of FA-related molecules. Results from IF staining showed that the proportions of talin1-, vinculin- and 9EG7-positive osteocytes were all significantly decreased in cortical bones from 5-month-old male cKO, compared with those from control mice (Fig. 6A–F). Consistently, siRNA knockdown of Pip5k1c reduced the protein expression level of talin1, integrin β1 and vinculin in MLO-Y4 cells (Fig. 6G–J).

Figure 6.

Loss of Pip5k1c in osteocytes reduces the expression of FA proteins. A, IF staining for expression of Talin1 of the tibial sections of 5-month-old control and cKO male mice. White dashed boxes indicate the higher magnification images in the right panels. White dashed lines indicate the bone surfaces. N = 6 mice per group. Scale bar, 100 μm. B, Quantification of (A). C, IF staining for expression of activated integrin β1 (9EG7) of the tibial sections from 5-month-old control and cKO male mice. White dashed boxes indicate the higher magnification images in the right panels. White dashed lines indicate the bone surfaces. N = 6 mice per group. Scale bar, 100 μm. D, Quantification of (C). E, IF staining for expression of vinculin of the tibial sections of 5-month-old control and cKO male mice. White dashed boxes indicate the higher magnification images in the right panels. White dashed lines indicate the bone surfaces. N = 6 mice per group. Scale bar, 100 μm. F, Quantification of (E). G, Western blot analysis. Protein samples extracted from the MLO-Y4 were transfected with si-NC or si-Pip5k1c and subjected to western blot analyses with indicated antibodies. H-J, Relative protein levels to Gapdh in MLO-Y4 cells transfected with NC siRNA or Pip5k1c siRNA. talin1 (H), vinculin (I) and integrin β1(J). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

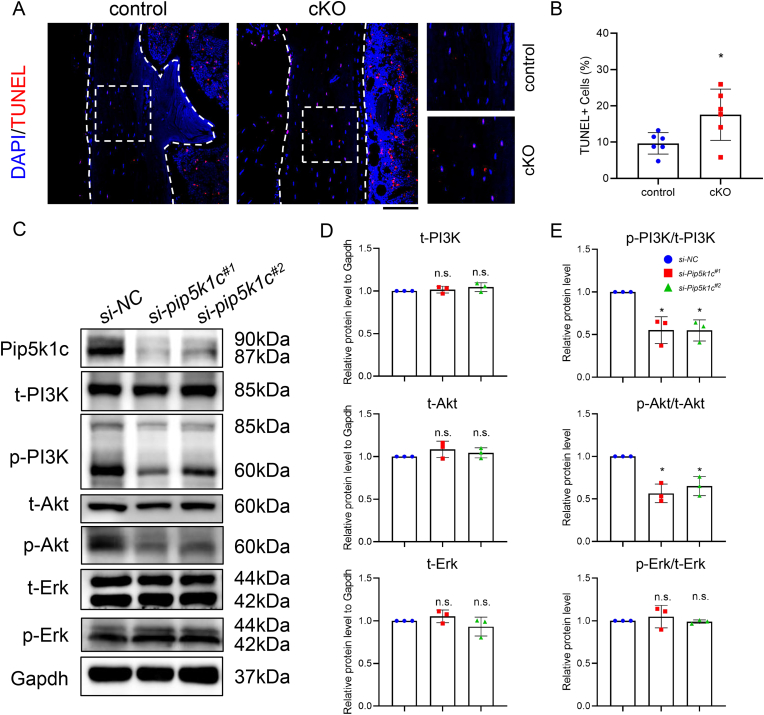

3.8. Pip5k1c loss increases osteocyte apoptosis in mice

In order to assess whether the apoptosis was affected by Pip5k1c loss. The results of TUNEL staining revealed that the percentage of apoptotic osteocytes was significantly increased in the cortical bone of cKO mice, compared to that in control mice (Fig. 7A and B). Results from in vitro studies revealed that siRNA knockdown of Pip5k1c in MLO-Y4 cells dramatically reduced the phosphorylated/total protein ratios of PI3K and Akt, without affecting the total protein levels of Akt, Erk and PI3K (Fig. 7C–E).

Figure 7.

Pip5k1c loss induces osteocyte apoptosis in mice. A, TUNEL staining of 5-month-old control and cKO of the tibial sections. White dashed boxes indicate the higher magnification images in the right panels. White dashed lines indicate the bone surfaces. Scale bar 100 μm. B, Quantification of (A). C, Western blot analysis. Protein extracts were isolated from the MLO-Y4 transfected with si-NC or si-Pip5k1c and subjected to western blot analyses with indicated antibodies. t: total; p: phosphorylated. D, Relative protein levels of t-PI3K, t-Akt and t-Erk to Gapdh in MLO-Y4 cells transfected with si-NC or si-Pip5k1c. E, Relative protein levels normalized as indicated ratio. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). n.s.: not significant, *P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we defined the key role of Pip5k1c expression in osteocytes in controlling bone remodeling. First, we observed a significant reduction of Pip5k1c in osteocytes in bones from elderly humans and aged. Second, we demonstrated that Pip5k1c deletion in Dmp1-expressing cells led to significant bone loss in the cancellous bone of both weight-bearing bones, such as the femur and lumbar vertebrae. However, the bone mass of non-weight-bearing calvaria was comparable between control and cKO mice. Third, we demonstrated that decreased bone formation was observed in Pip5k1c deletion mice, probably caused by a rise in osteocyte-expressed sclerostin. Accompanied by decreases in osteocyte formation and bone resorption, cKO mice displayed a low bone turnover osteopenia. Finally, we also demonstrated that Pip5k1c deletion reduced expression levels of several important FA proteins and, in the meantime, increased osteocyte apoptosis.

At 3 months old, the bone mass of cKO male mice was consistent with that of control mice. However, at 5 and 8 months old, cKO male mice showed significant bone loss. Compared to control mice, cKO mice displayed a 16.23 % reduction in trabecular BMD at 5 months old but a 25.43 % reduction at 8 months old. Surprisingly, there was no difference in bone mass between the control and cKO groups in female mice at 4, 6, and 12 months old (data not shown). The underlying mechanisms for this difference between the sexes deserve further investigation in future studies.

Notably, Pip5k1c deletion in Dmp1-positive cells showed inconsistent bone mass changes in non-mechanical loading versus mechanical loading bones. These results suggest that Pip5k1c may be involved in mediation of mechanotransduction in bone. Previous studies have shown that mechanical load-induced intraosseous pressure gradients may result in fluid shear stress (FSS), which could enable osteocytes to detect external mechanical signals [63]. The results from western blotting showed that after exposed to 10 dyne/cm2 flow for 2 h, the protein levels of Pip5k1c and kindlin-2 in MLO-Y4 cells were up-regulated (Supplemental Fig. 1). While this result suggests that the mechanical stress might be a key factor in regulating the level of Pip5k1c expression in osteocytes, whether or not Pip5k1c plays a role in mediating mechanotransduction in bone needs further investigation.

Pip5k1c loss resulted in reduced mechanical properties of the femur. On the one hand, the deletion of Pip5k1c in osteocytes caused low cancellous bone mass in femurs; this may suggest a decrease in mineral deposition. On the other hand, the Pip5k1c loss in MLO-Y4 cells reduced the type I collagen expression and the type I collagen content in the bone matrix.

In addition, we demonstrated that the Pip5k1c deletion in osteocytes impaired bone mass by affecting bone remodeling. Pip5k1c loss largely impaired osteoblast function and bone formation more than osteoclast formation and bone resorption, leading to low turnover osteopenia. Our results suggested that Pip5k1c loss upregulates sclerostin expression in vivo and in vitro, which may contribute to impairments in the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts in the bone marrow, ultimately affecting bone formation. The reduction of colonies in cKO group detected by CFU-F and CFU-OB analysis supports this notion (Supplemental Fig. 2).

The direct adhesion between osteocytes and the extracellular matrix (ECM) relies on the focal adhesions, linking to the actin skeleton to activate cellular responses [64,65]. Our previous studies reported the important role of focal adhesion in osteocytes in regulating bone homeostasis and bone mass, such as pinch1, pinch2, kindlin-2, integrin β3 and integrin β1 [6,7,11,12]. Besides, Pip5k1c was reported to regulate focal adhesion protein in neutrophils, articular cartilage chondrocytes and colon cancer cells [34,48,66]. In this study, we determined that the Pip5k1c loss decreased the focal adhesion protein level of vinculin, talin1 and active integrin β1 in osteocytes in cKO mice and in MLO-Y4 cells by siRNA knockdown, suggesting a possible mechanism through which Pip5k1c functions in maintaining bone mass.

Apoptosis of osteocytes can be induced by abnormal stress [67]. Reduced mechanical properties caused by Pip5k1c loss might lead to a high level of TUNEL-positive osteocytes in cKO mice. Activation of PI3K/Akt pathway can prevent MLO-Y4 cells from apoptosis [67], which suggests that the downregulation of phosphorylated AKT and phosphorylated PI3K caused by Pip5k1c loss in MLO-Y4 cells may contribute to the enhanced apoptosis.

Based on the critical role of Pip5k1c in osteocytes in the maintenance of bone homeostasis, thus, elucidation of the upstream signaling pathway of Pip5k1c is critical to identify novel approaches to control bone mass and prevent osteoporosis. Activation of Fas has been reported to promote osteocyte apoptosis and sclerostin expression in vitro [68,69]. Aurélie Rossin et al. demonstrated that Pip5k1c reduced FasL-induced cell death in colon cancer cells [70]. In addition, Pip5k1c was reported to be regulated by different posttranscriptional modifications. E3 ubiquitin ligases, such as Smurf1 and HECTD4, were shown to promote ubiquitination-mediated degradation of Pip5k1c [71,72]. Phosphorylation of Pip5k1c can be regulated by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) thereby affecting tumor cell invasion [72]. As a downstream of mTOR, S6K1 was shown to regulate Pip5k1c degradation via phosphorylation to promote cell migration and invasion [73].

Summarily, we establish the critical role of osteocyte Pip5k1c in the regulation of bone remodeling, bone mechanical properties and osteocyte survival and function. The findings of the present study provide a possible therapeutic target against human metabolic bone disease.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interest.

Author contributions

Study design: GX, SL and XZ. Study conduct and data collection: SL, CT, QY, HG, LQ, YZ, QY, PZ, JY and GX. Data analysis: SL and GX. Data interpretation: GX, SL and XZ. Drafting the manuscript: GX and SL. GX, SL and XZ take the responsibility for the integrity of the data analyses.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Core Research Facilities of SUSTech. Graphical abstract is created with Biorender.com. This work was supported by the Shenzhen Fundamental Research Program (JCYJ20220818100617036), the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants (82261160395, 82230081, 82250710175, 81991513, 82172375, 32071341), the National Key Research and Development Program of China Grants (2019YFA0906004), the Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Innovation Council Grant (2017B030301018) and the Shenzhen Municipal Science and Technology Innovation Council Grants (JCYJ20180302174246105 and ZDSYS20140509142721429).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jot.2023.10.008.

Contributor Information

Xuenong Zou, Email: zouxuen@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Guozhi Xiao, Email: xiaogz@sustech.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Foessl I., Dimai H.P., Obermayer-Pietsch B. Long-term and sequential treatment for osteoporosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023;19(9):520–533. doi: 10.1038/s41574-023-00866-9. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J., Shu B., Tang D.Z., Li C.G., Xie X.W., Jiang L.J., et al. The prevalence of osteoporosis in China, a community based cohort study of osteoporosis. Front Public Health. 2023;11 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1084005. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L., Yu W., Yin X., Cui L., Tang S., Jiang N., et al. Prevalence of osteoporosis and fracture in China: the China osteoporosis prevalence study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21106. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li H., Xiao Z., Quarles L.D., Li W. Osteoporosis: mechanism, molecular target and current status on drug development. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28(8):1489–1507. doi: 10.2174/0929867327666200330142432. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li M.C.M., Chow S.K.H., Wong R.M.Y., Qin L., Cheung W.H. The role of osteocytes-specific molecular mechanism in regulation of mechanotransduction - a systematic review. J. Ortho. Transl. 2021;29:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2021.04.005. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao H., Yan Q., Wang D., Lai Y., Zhou B., Zhang Q., et al. Focal adhesion protein Kindlin-2 regulates bone homeostasis in mice. Bone Res. 2020;8:2. doi: 10.1038/s41413-019-0073-8. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y., Yan Q., Zhao Y., Liu X., Lin S., Zhang P., et al. Focal adhesion proteins Pinch1 and Pinch2 regulate bone homeostasis in mice. JCI insight. 2019;4(22) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.131692. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu X., Zhou B., Yan Q., Tao C., Qin L., Wu X., et al. Kindlin-2 regulates skeletal homeostasis by modulating PTH1R in mice. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. 2020;5(1):297. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00328-y. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao M., Zhang W., Liu W., Mao L., Yang J., Hu L., et al. Osteocytes regulate neutrophil development through IL-19: a potent cytokine for neutropenia treatment. Blood. 2021;137(25):3533–3547. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007731. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim J., Burclaff J., He G., Mills J.C., Long F. Unintended targeting of Dmp1-Cre reveals a critical role for Bmpr1a signaling in the gastrointestinal mesenchyme of adult mice. Bone Res. 2017;5 doi: 10.1038/boneres.2016.49. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qin L., He T., Yang D., Wang Y., Li Z., Yan Q., et al. Osteocyte β1 integrin loss causes low bone mass and impairs bone mechanotransduction in mice. J. Ortho. Transl. 2022;34:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2022.03.008. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin L., Chen Z., Yang D., He T., Xu Z., Zhang P., et al. Osteocyte β3 integrin promotes bone mass accrual and force-induced bone formation in mice. J. Ortho. Transl. 2023;40:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2023.05.001. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang K., Ren Y., Lin S., Jing Y., Ma C., Wang J., et al. Osteocytes but not osteoblasts directly build mineralized bone structures. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(10):2430–2448. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.61012. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldring S.R. The osteocyte: key player in regulating bone turnover. RMD Open. 2015;1(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000049. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLaughlin S., Murray D. Plasma membrane phosphoinositide organization by protein electrostatics. Nature. 2005;438(7068):605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature04398. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheetz M.P., Sable J.E., Döbereiner H.G. Continuous membrane-cytoskeleton adhesion requires continuous accommodation to lipid and cytoskeleton dynamics. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:417–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102017. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown F.D., Rozelle A.L., Yin H.L., Balla T., Donaldson J.G. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and Arf6-regulated membrane traffic. J Cell Biol. 2001;154(5):1007–1017. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103107. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cremona O., Di Paolo G., Wenk M.R., Lüthi A., Kim W.T., Takei K., et al. Essential role of phosphoinositide metabolism in synaptic vesicle recycling. Cell. 1999;99(2):179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81649-9. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott C.C., Dobson W., Botelho R.J., Coady-Osberg N., Chavrier P., Knecht D.A., et al. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis directs actin remodeling during phagocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2005;169(1):139–149. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412162. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunz J., Fuelling A., Kolbe L., Anderson R.A. Stereo-specific substrate recognition by phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases is swapped by changing a single amino acid residue. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(7):5611–5619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110775200. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasudevan L., Jeromin A., Volpicelli-Daley L., De Camilli P., Holowka D., Baird B. The beta- and gamma-isoforms of type I PIP5K regulate distinct stages of Ca2+ signaling in mast cells. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 14):2567–2574. doi: 10.1242/jcs.048124. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y., Lian L., Golden J.A., Morrisey E.E., Abrams C.S. PIP5KI gamma is required for cardiovascular and neuronal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(28):11748–11753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700019104. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishihara H., Shibasaki Y., Kizuki N., Katagiri H., Yazaki Y., Asano T., et al. Cloning of cDNAs encoding two isoforms of 68-kDa type I phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(39):23611–23614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.23611. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishihara H., Shibasaki Y., Kizuki N., Wada T., Yazaki Y., Asano T., et al. Type I phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinases. Cloning of the third isoform and deletion/substitution analysis of members of this novel lipid kinase family. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(15):8741–8748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8741. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borbiro I., Badheka D., Rohacs T. Activation of TRPV1 channels inhibits mechanosensitive Piezo channel activity by depleting membrane phosphoinositides. Sci Signal. 2015;8(363) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005667. ra15. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ewies A.A., Elshafie M., Li J., Stanley A., Thompson J., Styles J., et al. Changes in transcription profile and cytoskeleton morphology in pelvic ligament fibroblasts in response to stretch: the effects of estradiol and levormeloxifene. Mol Hum Reprod. 2008;14(2):127–135. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gam090. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang T.Y., Jiang J., Xu R.K., Zhou L.X., Wang S.M. [Effects of different temperatures biochar on adsorption of Pb(II) on variable charge soils] Huan jing ke xue= Huanjing kexue. 2013;34(4):1598–1604. [chi] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y., Litvinov R.I., Chen X., Bach T.L., Lian L., Petrich B.G., et al. Loss of PIP5KIgamma, unlike other PIP5KI isoforms, impairs the integrity of the membrane cytoskeleton in murine megakaryocytes. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(2):812–819. doi: 10.1172/JCI34239. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Capuano C., Paolini R., Molfetta R., Frati L., Santoni A., Galandrini R. PIP2-dependent regulation of Munc13-4 endocytic recycling: impact on the cytolytic secretory pathway. Blood. 2012;119(10):2252–2262. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-324160. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baba T., Toth D.J., Sengupta N., Kim Y.J., Balla T. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate controls Rab7 and PLEKHM1 membrane cycling during autophagosome-lysosome fusion. EMBO J. 2019;38(8) doi: 10.15252/embj.2018100312. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Płóciennikowska A., Zdioruk M.I., Traczyk G., Świątkowska A., Kwiatkowska K. LPS-induced clustering of CD14 triggers generation of PI(4,5)P2. J Cell Sci. 2015;128(22):4096–4111. doi: 10.1242/jcs.173104. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fairn G.D., Ogata K., Botelho R.J., Stahl P.D., Anderson R.A., De Camilli P., et al. An electrostatic switch displaces phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases from the membrane during phagocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2009;187(5):701–714. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909025. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mao Y.S., Yamaga M., Zhu X., Wei Y., Sun H.Q., Wang J., et al. Essential and unique roles of PIP5K-gamma and -alpha in Fcgamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2009;184(2):281–296. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806121. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu W., Wang P., Petri B., Zhang Y., Tang W., Sun L., et al. Integrin-induced PIP5K1C kinase polarization regulates neutrophil polarization, directionality, and in vivo infiltration. Immunity. 2010;33(3):340–350. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.015. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halstead J.R., van Rheenen J., Snel M.H., Meeuws S., Mohammed S., D'Santos C.S., et al. A role for PtdIns(4,5)P2 and PIP5Kalpha in regulating stress-induced apoptosis. Curr Biol : CB. 2006;16(18):1850–1856. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.066. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narkis G., Ofir R., Landau D., Manor E., Volokita M., Hershkowitz R., et al. Lethal contractural syndrome type 3 (LCCS3) is caused by a mutation in PIP5K1C, which encodes PIPKI gamma of the phophatidylinsitol pathway. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):530–539. doi: 10.1086/520771. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng X., Uyar A., Sui D., Donyapour N., Wu D., Dickson A., et al. Structural insights into lethal contractural syndrome type 3 (LCCS3) caused by a missense mutation of PIP5Kγ. Biochem J. 2018;475(14):2257–2269. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20180326. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xue J., Chen C., Qi M., Huang Y., Wang L., Gao Y., et al. Type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase regulates PD-L1 expression by activating NF-κB. Oncotarget. 2017;8(26):42414–42427. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17123. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun Y., Turbin D.A., Ling K., Thapa N., Leung S., Huntsman D.G., et al. Type I gamma phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase modulates invasion and proliferation and its expression correlates with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(1):R6. doi: 10.1186/bcr2471. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu T., Chappel J.C., Hsu F.F., Turk J., Aurora R., Hyrc K., et al. Type I phosphotidylinosotol 4-phosphate 5-kinase gamma regulates osteoclasts in a bifunctional manner. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(8):5268–5277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.446054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen C., Wang X., Fang J., Xue J., Xiong X., Huang Y., et al. EGFR-induced phosphorylation of type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase promotes pancreatic cancer progression. Oncotarget. 2017;8(26):42621–42637. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16730. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cao S., Chen C., Xue J., Huang Y., Yang X., Ling K. Silencing of type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase suppresses ovarian cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Oncol Rep. 2017;38(1):253–262. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5670. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loo L., Zylka M. Conditional deletion of Pip5k1c in sensory ganglia and effects on nociception and inflammatory sensitization. Mol Pain. 2017;13 doi: 10.1177/1744806917737907. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodriguez L., Simeonato E., Scimemi P., Anselmi F., Calì B., Crispino G., et al. Reduced phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate synthesis impairs inner ear Ca2+ signaling and high-frequency hearing acquisition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(35):14013–14018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211869109. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang W., Zhang Y., Xu W., Harden T.K., Sondek J., Sun L., et al. A PLCβ/PI3Kγ-GSK3 signaling pathway regulates cofilin phosphatase slingshot2 and neutrophil polarization and chemotaxis. Dev Cell. 2011;21(6):1038–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.023. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang G., Yang C., Guo S., Huang M., Deng L., Huang Y., et al. Adipocyte-specific deletion of PIP5K1c reduces diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance by increasing energy expenditure. Lipids Health Dis. 2022;21(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12944-021-01616-4. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu T., Chappel J.C., Hsu F.F., Turk J., Aurora R., Hyrc K., et al. Type I phosphotidylinosotol 4-phosphate 5-kinase γ regulates osteoclasts in a bifunctional manner. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(8):5268–5277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.446054. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qu M., Chen M., Gong W., Huo S., Yan Q., Yao Q., et al. Pip5k1c loss in chondrocytes causes spontaneous osteoarthritic lesions in aged mice. Aging and Disease. 2023;14(2):502–514. doi: 10.14336/AD.2022.0828. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan Q., Gao H., Yao Q., Ling K., Xiao G. Loss of phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type-1 gamma (Pip5k1c) in mesenchymal stem cells leads to osteopenia by impairing bone remodeling. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(3) doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101639. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu X., Lai Y., Chen S., Zhou C., Tao C., Fu X., et al. Kindlin-2 preserves integrity of the articular cartilage to protect against osteoarthritis. Nat Aging. 2022;2(4):332–347. doi: 10.1038/s43587-021-00165-w. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang K., Qiu W., Li H., Li J., Wang P., Chen Z., et al. MACF1 overexpression in BMSCs alleviates senile osteoporosis in mice through TCF4/miR-335-5p signaling pathway. J. Ortho. Transl. 2023;39:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2023.02.003. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bouxsein M.L., Boyd S.K., Christiansen B.A., Guldberg R.E., Jepsen K.J., Müller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res : Officl J Am Soc Bone Mineral Res. 2010;25(7):1468–1486. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.141. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu H., Tan J., Sun D., Wang X., Shen J., Wang S., et al. Discovery of multipotent progenitor cells from human induced membrane: equivalent to periosteum-derived stem cells in bone regeneration. J. Ortho. Transl. 2023;42:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2023.07.004. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu X., Qu M., Gong W., Zhou C., Lai Y., Xiao G. Kindlin-2 deletion in osteoprogenitors causes severe chondrodysplasia and low-turnover osteopenia in mice. J. Ortho. Transl. 2022;32:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2021.08.005. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gao H., Zhong Y., Lin S., Yan Q., Zou X., Xiao G. Bone marrow adipoq(+) cell population controls bone mass via sclerostin in mice. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. 2023;8(1):265. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01461-0. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao H., Zhong Y., Ding Z., Lin S., Hou X., Tang W., et al. Pinch loss ameliorates obesity, glucose intolerance, and fatty liver by modulating adipocyte apoptosis in mice. Diabetes. 2021;70(11):2492–2505. doi: 10.2337/db21-0392. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao H., Zhong Y., Zhou L., Lin S., Hou X., Ding Z., et al. Kindlin-2 inhibits TNF/NF-κB-Caspase 8 pathway in hepatocytes to maintain liver development and function. Elife. 2023;12 doi: 10.7554/eLife.81792. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qin L., Fu X., Ma J., Lin M., Zhang P., Wang Y., et al. Kindlin-2 mediates mechanotransduction in bone by regulating expression of Sclerostin in osteocytes. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):402. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-01950-4. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nader G.P., Ezratty E.J., Gundersen G.G. FAK, talin and PIPKIγ regulate endocytosed integrin activation to polarize focal adhesion assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18(5):491–503. doi: 10.1038/ncb3333. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le O.T., Cho O.Y., Tran M.H., Kim J.A., Chang S., Jou I., et al. Phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase γ by Akt regulates its interaction with talin and focal adhesion dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1853(10 Pt A):2432–2443. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.07.001. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Di Paolo G., Pellegrini L., Letinic K., Cestra G., Zoncu R., Voronov S., et al. Recruitment and regulation of phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase type 1 gamma by the FERM domain of talin. Nature. 2002;420(6911):85–89. doi: 10.1038/nature01147. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ling K., Doughman R.L., Iyer V.V., Firestone A.J., Bairstow S.F., Mosher D.F., et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of type Igamma phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase by Src regulates an integrin-talin switch. J Cell Biol. 2003;163(6):1339–1349. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310067. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu X., Wang N., Wang Z., Yu W., Wang Y., Guo Y., et al. Mathematically modeling fluid flow and fluid shear stress in the canaliculi of a loaded osteon. Biomed Eng Online. 2016;15(Suppl 2):149. doi: 10.1186/s12938-016-0267-x. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen S., He T., Zhong Y., Chen M., Yao Q., Chen D., et al. Roles of focal adhesion proteins in skeleton and diseases. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13(3):998–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.09.020. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi J.U.A., Kijas A.W., Lauko J., Rowan A.E. The mechanosensory role of osteocytes and implications for bone health and disease states. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.770143. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu Z., Li X., Sunkara M., Spearman H., Morris A.J., Huang C. PIPKIγ regulates focal adhesion dynamics and colon cancer cell invasion. PLoS One. 2011;6(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024775. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ru J.Y., Wang Y.F. Osteocyte apoptosis: the roles and key molecular mechanisms in resorption-related bone diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(10):846. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-03059-8. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kratochvilova A., Ramesova A., Vesela B., Svandova E., Lesot H., Gruber R., et al. Impact of FasL stimulation on sclerostin expression and osteogenic profile in IDG-SW3 osteocytes. Biology. 2021;10(8) doi: 10.3390/biology10080757. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kogianni G., Mann V., Ebetino F., Nuttall M., Nijweide P., Simpson H., et al. Fas/CD95 is associated with glucocorticoid-induced osteocyte apoptosis. Life Sci. 2004;75(24):2879–2895. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.04.048. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rossin A., Lounnas N., Durivault J., Miloro G., Gagnoux-Palacios L., Hueber A.O. The Btk-dependent PIP5K1γ lipid kinase activation by Fas counteracts FasL-induced cell death. Apoptosis : Int J Program Cell Death. 2017;22(11):1344–1352. doi: 10.1007/s10495-017-1415-x. [eng] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li X., Zhou Q., Sunkara M., Kutys M.L., Wu Z., Rychahou P., et al. Ubiquitylation of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase type I γ by HECTD1 regulates focal adhesion dynamics and cell migration. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 12):2617–2628. doi: 10.1242/jcs.117044. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li L., Kołodziej T., Jafari N., Chen J., Zhu H., Rajfur Z., et al. Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation regulates phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase type I γ 90 activity and cell invasion. Faseb J : Offl Publ Feder Am Soc Exper Biol. 2019;33(1):631–642. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800296R. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jafari N., Zheng Q., Li L., Li W., Qi L., Xiao J., et al. p70S6K1 (S6K1)-mediated phosphorylation regulates phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase type I γ degradation and cell invasion. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(49):25729–25741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.742742. [eng] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.