Abstract

Introduction and importance

Primary central nervous system (CNS) melanoma is a rare entity. Primary CNS malignant melanomas account for 1 % of melanomas and 0.07 % of intracranial tumours. These are highly aggressive and are associated with poor prognosis. Herein, we have discussed one such rare case of PIMM.

Case presentation

62-year-old man with primary CNS melanoma underwent craniotomy and resection of left temporal lesion. Postoperative MRI showed no evidence of residual disease. He received 28 fractions of radiation. Follow-up MRI showed no evidence of disease. However, he later developed worsening symptoms and repeat imaging revealed disease progression with hydrocephalus and drop metastasis to spine. He underwent VP shunting and was started on Temozolomide. He progressively declined functionally and eventually died from his disease.

Clinical discussion

Primary CNS melanoma is characterized by its rarity, challenging diagnosis, and aggressive behaviour. Current literature suggests limited treatment options, which depend on complete resection of the primary tumour. Molecular analysis may play a key role in deciding future treatment options, including immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies targeting the BRAFV600E mutation.

Conclusion

Primary intracranial malignant melanoma (PIMM) is an extremely rare tumour of CNS, and its treatment paradigm is very limited based on available literature. Currently any long-term survival depends on the complete resection of tumour. Our case is unique as it talks about the limited therapeutic options in case of rapidly declining performance status in a resource constraint setting.

Keywords: Primary intracranial malignant melanoma (PIMM), CNS melanoma, Melanoma metastasis, Immunotherapy, Chemo radiation

Highlights

-

•

This case report presents a rare primary intracranial malignant melanoma (PIMM) with limited therapeutic options due to rapid performance decline and resource constraints.

-

•

Difficulty establishing diagnosis and obtaining molecular testing due to poor functional status and financial limitations.

-

•

Temozolomide chosen based on existing research despite lack of molecular profiling, considering resource limitations and rapid decline.

-

•

Emphasizes the emotional and financial burdens of a rare diagnosis and limited treatment options in a resource-poor setting.

1. Introduction

Primary central nervous system (CNS) melanoma is a rare entity and it derives from the melanocytic precursor cells called melano-blast, in neural crest [1]. They usually arise from lepto-meninges and are present in the distribution of melanocytes. Primary CNS malignant melanomas account for 1 % of melanomas and 0.07 % of intracranial tumours [2,3]. Review of literature revealed only 26 cases of primary intracranial malignant melanoma (PIMM) to be existing till 2016 and they tend to be male pre-dominant tumours [[4], [5], [6]]. These tumours are highly aggressive and are associated with poor prognosis with median overall survival of 1 year [7]. Herein, we have discussed one such rare case of PIMM. This case aims to provide insights into the clinical characteristics and management of primary CNS melanoma. As the current literature still has too few cases to concur the best therapeutic options. Our case aims to establish the challenges of diagnosis of rare tumours and the scarcity of available therapeutic options in case of poor functional status in resource limited settings. This case report compliance by SCARE checklist [19].

2. Case preparation

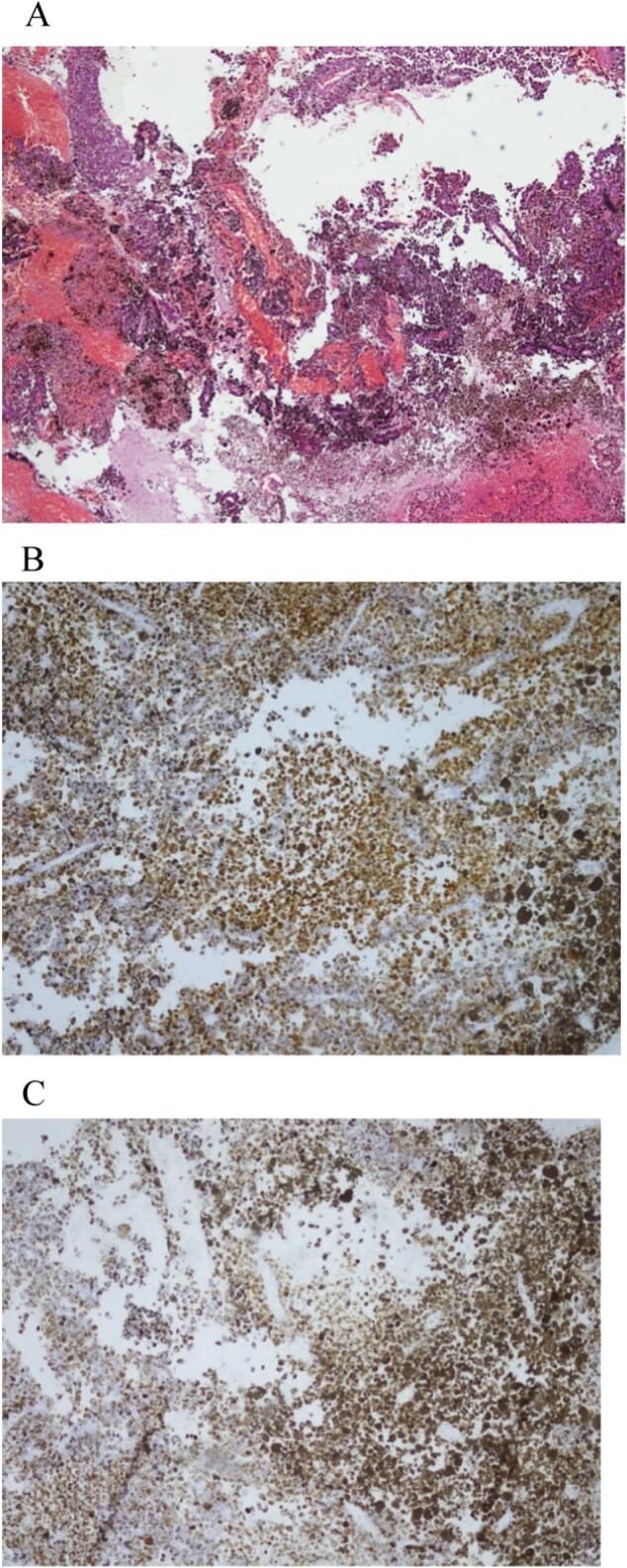

A 62-year-old gentleman presented in neurosurgery department with sudden onset headache, seizure like episode, confusion and slurring of speech in January '22, work-up revealed well defined space occupying lesion in left temporal lobe, measuring 37 × 41 × 32 mm shown in Fig. 1(A) and (B). On 31st January 2021, he underwent craniotomy and excision of left temporal lesion, intra-operatively multiple diffuse melanotic patches over skull base dura and pial surfaces over the cortex were observed, deeply pigmented soft tumour was seen. 15 cc of motor oil coloured fluid was aspirated from clot and multiple blood clots of varying ages were present. Post-operative scan showed no evidence of residual disease. Histopathology revealed Melanoma, positive for Melan A, HMB45, and Ki-67 was high and margins couldn't be assessed show in Fig. 2(A), (B), and (C). Systemic scans were done to rule out metastasis and there was no evidence of disease elsewhere in the body and it was deemed as primary CNS melanoma. He received 28 fractions of radiation. He was followed with MRI brain every three months, revealing no evidence of disease progression. He developed worsening symptoms in June '22, new imaging revealed disease progression with hydrocephalus and drop metastasis to spine with diffuse nodular enhancement of meningeal lining. He underwent VP shunting in August '22 after initially managing symptoms conservatively. He had a declining functional class and couldn't tolerate aggressive systemic treatment for his malignancy. Patient and his family didn't agree for molecular testing due to financial constraints, so he was started on Temozolomide 200 mg/m2 day 1 to 5 every 28-day cycle. He progressively declined functionally and eventually was advised for best supportive care only and succumbed to his disease in October '22.

Fig. 1.

(A) MRI brain T1 axial (B) T2 axial images showing lesion in left temporal region.

Fig. 2.

(A) Low power view showing glial tissue infiltrated by neoplastic cells with abundant melanin pigment.

(B) MELAN-A stain highlighting melanin pigment.

(C) HMB-45 antibody strongly stained cytoplasm of neoplastic cells.

3. Discussion

Primary CNS melanoma is characterized by its rarity, challenging diagnosis, and aggressive behaviour. Timely diagnosis and multimodal therapy, including surgical resection, adjuvant radiation, and systemic therapy, play vital roles in achieving favourable outcomes [8]. Diagnosis of primary CNS melanoma may pose a challenge as it requires meticulous imaging to rule out metastasis from other primary site [9]. HMB-45 is one of the antibodies which is present with a higher specificity in melanocytic tumours. Review of literature revealed that about, 86–97 % of melanocytic tumours are positive for HMB-45 antigen [2,10]. Our case was also consistent with the positivity of HMB-45 antibody. Although the prognosis for primary CNS melanoma is generally poor, long-term survival can be achieved in select cases with extensive treatment approaches. Surgical intervention remained the most important treatment modality according to the available literature [11,12]. Despite known to be radio-chemotherapy resistant, melanomas tend to respond to adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy and adjuvant whole brain radiation with Temozolomide remains an option [13]. Stereotactic radiosurgery for residual tumour can be an acceptable option [7]. In case of recurrence, aggressive surgery may still have a better role. Patients undergoing gross total resection followed by adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy had significantly higher 1-year and 5-year OS rates [14]. Dacarbazine based chemotherapy, used in other metastatic melanomas, has an effectiveness of 16–20 % [15]. While in one study, comparison between Dacarbazine and Temozolomide (TMZ) showed TMZ to be more effective in terms of response. This added benefit was attributed to more effective CNS penetration. Our case differed from other cases in terms of briskly declining performance status and hence obtaining molecular testing would be too time consuming and financially challenging for the patient, with still poorer outcome. So considering the circumstances and statistically significant outcomes, patient was managed with TMZ. BRAF kinase inhibitors, such as vemurafenib, were effective in treating cancers that carried the BRAF V600 mutation [16]. Metastatic melanomas responded well to checkpoint suppression with the anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) antibody ipilimumab and an anti-programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) antibody (pembrolizumab, nivolumab) [17]. Ipilimumab and nivolumab may also be effective in treating melanoma brain metastases, according to a systematic review [18]. However, their role in PIMM has yet to be elucidated.

4. Conclusion

Primary intracranial malignant melanoma (PIMM) is an extremely rare tumour of CNS, and its treatment paradigm is very limited based on available literature and the prognosis remains dismal. Diagnosis and management of new cases may give us better understanding of this rare CNS tumour in the era of molecular advancement. Establishing molecular diagnosis early on may provide targetable mutations and hence may improve the outcome. Yet the case signifies the poor outcomes of PIMM and the need for further therapeutic advancements to offer better result. Currently any long-term survival depends on the complete resection of tumour followed by radiotherapy.

4.1. Patient's perspective

This rare diagnosis and limited therapeutic options, posed significant challenge for the patient also. Bearing a diagnosis with rare tumour caused emotional and financial burden in a resource poor setting. It was cumbersome for the patient as well as the family to undergo repeated imaging for surveillance and after developing metastasis, he had undergone time toxicity due to management of contraindications related to disease as well as the treatment. Upon decline in functional class patient didn't want to go for further affluent testing and opted to continue with available therapeutic options.

4.2. Limitations

This case report was a single case study and patient had a protracted clinical course, hence it couldn't elaborate on the actual outcome in case further chemotherapeutic/ immunotherapy options would have been used. This study is also limited due to non-availability of appropriate molecular testing in the region that could provide valuable insight for targeted treatment options as well as tumour biology.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request - added in the revised manuscript.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was waived for this study as it was a case report and The Aga Khan University Hospital's Ethical Review Board exempts case reports for Ethical Approval Certificate.

Funding

Non-funded study.

Guarantor

Adeeba Zaki.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Warda Saleem conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and finalized the manuscript after editing.

Nida E Zehra reviewed the manuscript and revised the final editing of the manuscript.

Tasneem Dawood drafted the initial manuscript.

Yasmin A Rashid provided the scientific review and histopathology figures with details.

Adeeba Zaki critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- 1.Chandran R., Patil A., Prabhakar R., Balachandran K. Melanotic schwannoma of spine: illustration of two cases with diverse clinical presentation and outcome. Asian. J. Neurosurg. 2018;13(03):881–884. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_353_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crasto S.G., Soffietti R., Bradac G., Boldorini R. Primitive cerebral melanoma: case report and review of the literature. Surg. Neurol. 2001;55(3):163–168. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(01)00348-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byun J., Park E.S., Hong S.H., Cho Y.H., Kim Y.H., Kim C.J., et al. Clinical outcomes of primary intracranial malignant melanoma and metastatic intracranial malignant melanoma. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2018;164:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liubinas S.V., Maartens N., Drummond K.J. Primary melanocytic neoplasms of the central nervous system. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2010;17(10):1227–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnholtz-Sloan J.S., Sloan A.E., Davis F.G., Vigneau F.D., Lai P., Sawaya R.E. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22(14):2865–2872. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freudenstein D., Wagner A., Bornemann A., Ernemann U., Bauer T., Duffner F. Primary melanocytic lesions of the CNS: report of five cases. Zentralbl. Neurochir. 2004;65(03):146–153. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-816266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee P.H., Wang L.C., Lee E.J. Primary intracranial melanoma. J. Can. Res. Prac. 2017;4(1):23–26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibney G.T., Forsyth P.A., Sondak V. Melanoma in the brain: biology and therapeutic options. Melanoma Res. 2012;22(3):177–183. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e328352dbef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel J., Mansuriya R. A rare case of primary malignant melanoma in brain. Int. Arch. Integ. Med. 2019;6(7):87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brat D.J., Giannini C., Scheithauer B.W., Burger P. Primary melanocytic neoplasms of the central nervous system. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1999;23(7):745. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199907000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumagai Y., Sugiyama H., Sugiura H., Kito K., Shitara N. A case of intracranial melanoma who has been survived more than 12 years after initial craniotomy was reported (author’s transl) No To Shinkei. 1979;31(4):397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson T.C., Houser O.W., Onofrio B.M., Piepgras D.G. Primary spinal melanoma. J. Neurosurg. 1987;66(1):47–49. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.1.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balakrishnan R., Porag R., Asif D.S., Satter A., Taufiq M., Gaddam S.S. Primary intracranial melanoma with early leptomeningeal spread: a case report and treatment options available. Case Rep. Oncol. Med. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/293802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C.B., Song L.R., Li D., Weng J.C., Zhang L.W., Zhang J.T., et al. Primary intracranial malignant melanoma: proposed treatment protocol and overall survival in a single-institution series of 15 cases combined with 100 cases from the literature. J. Neurosurg. 2019;132(3):902–913. doi: 10.3171/2018.11.JNS181872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bedikian A.Y., Legha S.S., Mavligit G., Carrasco C.H., Khorana S., Plager C., et al. Treatment of uveal melanoma metastatic to the liver. A review of the MD Anderson Cancer Center experience and prognostic factors. Cancer. 1995;76(9):1665–1670. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951101)76:9<1665::aid-cncr2820760925>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J.M., Mehta U.N., Dsouza L.H., Guadagnolo B.A., Sanders D.L., Kim K.B. Long-term stabilization of leptomeningeal disease with whole-brain radiation therapy in a patient with metastatic melanoma treated with vemurafenib: a case report. Melanoma Res. 2013;23(2) doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32835e589c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larkin J., Chiarion-Sileni V., Gonzalez R., Grob J.J., Cowey C.L., Lao C.D., et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. 2015;373(1):23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Bussel M.T., Beijnen J.H., Brandsma D.J. Intracranial antitumor responses of nivolumab and ipilimumab: a pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic perspective, a scoping systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5741-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Maria N., Kerwan A., Franchi T., Agha R.A., Collaborators. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. May 1 2023;109(5):1136–1140. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. (PMID: 37013953; PMCID: PMC10389401) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]