Abstract

Introduction

Parietal endometriosis is the most common form of extra-pelvic endometriosis. It develops on the surgical scar of c-section or hysterectomy. It is one of the causes of scar pain.

Case presentation

A 26 years old patient presents with recurring pain and swelling of a Pfannenstiel scar 6 years after a caesarean section. Physical examination revealed a firm tender subcutaneous nodule that appeared at MRI as a heterogenous parietal mass infiltrating the rectus abdominis muscles. The patient underwent a wide excision of the nodule.

Discussion

Parietal endometriosis can be the cause of debilitating scar pain even in patients with no history of deep endometriosis. It presents as firm parietal nodule that can become large and infiltrative if left untreated. Diagnosis is purely histological. Surgery remains the treatment of choice and requires a wide excision.

Conclusion

Parietal endometriosis, potentially more common due to rising number of caesarean sections, should be considered with persistent scar pain. Surgery is the preferred treatment, offering a conclusive diagnosis.

Keywords: Parietal endometriosis, Nodule, Caesarean section scar, Catamenial pain, Wide excision

Highlights

-

•

Parietal endometriosis is a rare localization of endometriosis.

-

•

It develops on gynecological and obstetrical scars and can be the cause of intense cyclical pain.

-

•

Radiological exams help characterize the extension of the endometriotic nodule. Diagnosis is purely histopathological.

-

•

Management relies on wide and radical surgical resection.

1. Introduction

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of functional endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity. It is a condition that affects 15 % of women of reproductive age [1]. While it mainly localizes in the pelvis, it can also manifest in extra-pelvic locations such as the bowel, lungs, kidneys, brain, and abdominal wall [2].

Parietal endometriosis (PE) represents the most common form of extra-pelvic endometriosis, with an incidence ranging from 0.03 % to 3.5 % [2]. It most commonly develops on the scars of gynecological and obstetrical surgeries, especially caesarean section scars. Although it lacks specific clinical signs, the diagnosis of parietal endometriosis is typically suspected when a mass adjacent to a median or Pfannenstiel scar is accompanied by catamenial pain. Imaging techniques such as ultrasound and MRI are useful for characterizing parietal endometriotic nodules and their extent, but it is surgical resection with histopathological examination that confirms the diagnosis [3].

We report a case of sizable parietal endometriosis diagnosed in a patient with a history of one caesarean section. We discuss the various diagnostic and therapeutic elements involved in its management and aim to highlight the role of a multidisciplinary approach, including gynecologists and surgeons.

Our work has been reported in line with the SCARE Guidelines 2020 criteria [4].

2. Case report

A 26-year-old patient, G1P1, with no notable pathological history, who gave birth by caesarean section 6 years ago. She presented to the obstetrics and gynaecology department for consultation because she had been experiencing, for the past 4 years, c- section scar pain worsening during menstruation.

Physical examination revealed the presence of a firm, tender subcutaneous nodule at the midline of the scar, fixed to the deeper anatomical planes, measuring 5 cm in diameter, with slight hyperpigmentation of the overlying skin (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Slight hyperpigmentation of the c-section scar.

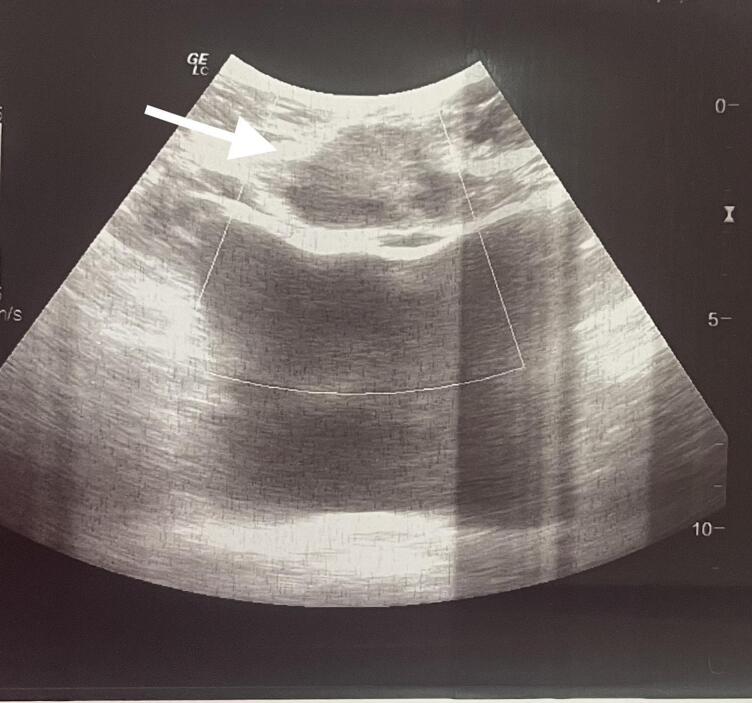

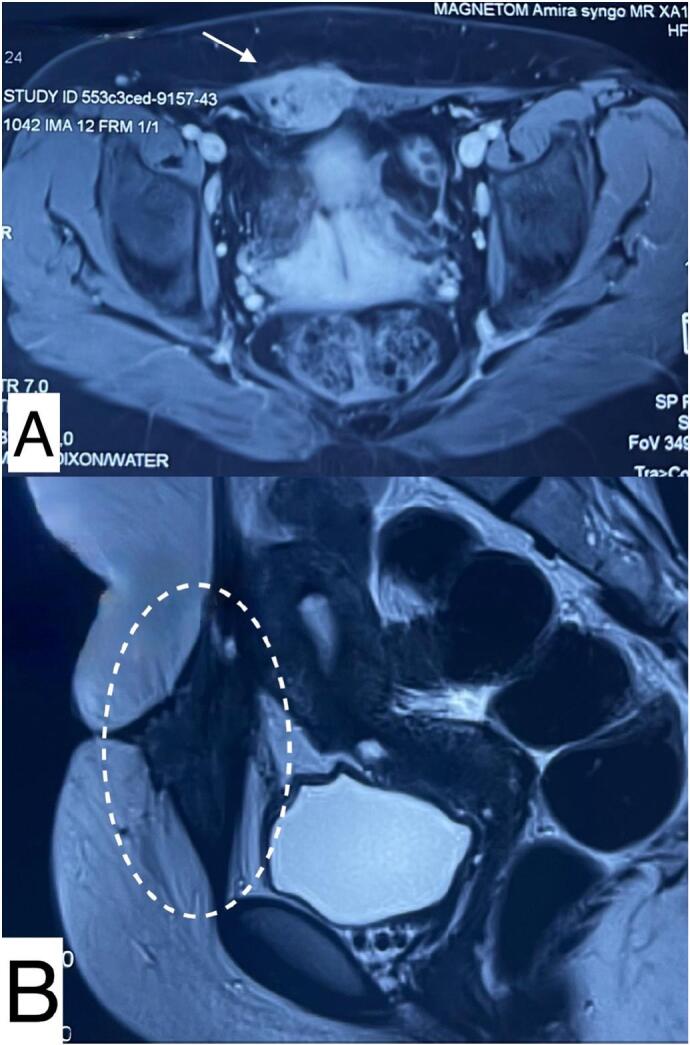

Ultrasound shows the nodule as a hypoechoic, heterogeneous lesion with indistinct borders (Fig. 2). Supplementary MRI revealed a subcutaneous, poorly defined, heterogeneous parietal mass, with irregular contours, enhanced after injection of Gadolinium, measuring 31 × 55 mm, containing liquid areas with infiltration of the rectus abdominis muscles (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Ultrasound image of the endometriotic nodule which appears hypoechoic with undistinct borders.

Fig. 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.

A. Axial view of the nodule embedded in the rectus abdominis muscles.

B. Sagittal view of a heterogenous poorly defined parietal mass containing liquid areas.

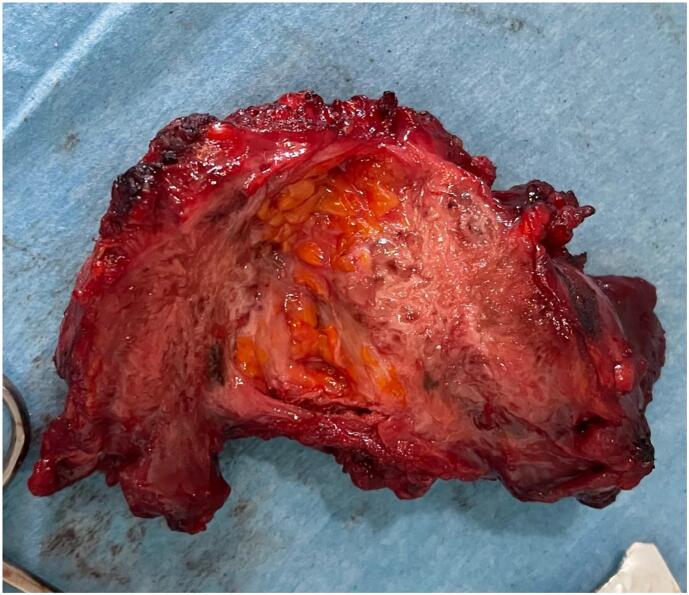

In view of these clinical and radiological findings, the diagnosis of parietal endometriosis was made and surgical treatment was indicated. We performed a wide excision of the nodule with a wedge-shaped incision of the skin and interposition of a polypropylene mesh to fill the parietal defect. Surgical exploration did not reveal deep endometriosis (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Image of the resected nodule.

Macroscopically, the nodule weighed 73 g and measured 7x6x4 cm with the presence, on section, of a fibrous, white-grey lesion measuring 5 × 3.5 cm. Histopathological examination revealed fibrous tissue with glandular structures resembling endometrial tissue, thus confirming the diagnosis of parietal endometriosis. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the 6-month follow-up showed a significant clinical improvement with complete resolution of scar pain.

3. Discussion

First described by Meyer in 1903, parietal endometriosis is defined by the presence of endometrial tissue in the abdominal wall, above the peritoneum, from the skin to the parietal muscles. It is the most common form of extra-abdominopelvic endometriosis. It occurs mainly on scars following gynecological and obstetric surgery, including hysterectomy (2 %) and caesarean section (0.1 to 0.4 %), although 20 % of cases occur spontaneously or at a distance from the scar [5]. 22 % of women of all ages are affected, especially multiparous women between 25 and 35 years old, but it can also occur in women approaching menopause [6]. It is associated with deep endometriosis in only 26 % of cases [1].

The physiopathology of parietal endometriosis can be explained according to 2 theories: the first theory suggests iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells on the abdominal wall during surgery, especially during subtotal hysterectomy exposing the endometrium to the abdominal cavity [2]. Caesarean section in particular creates a rich nutritional environment for cellular implants due to the high volume of blood and contamination of endometrial cells during dissection, all the more so if it is performed before the onset of labour [7]. The second theory of the pathogenesis of parietal endometriosis suggests dissemination through the bloodstream or lymphatic system in patients with deep pelvic endometriosis [2].

Clinical diagnosis is based on the triad described by Esquivel: catamenial pain, palpable mass and a history of caesarean section or gynecological surgery [8]. Although this triad is present in our patient, it is not always the case. In fact, the cyclical nature of the pain is not constant, just as there may be no palpable mass [1]. The interval between surgery and the onset of these symptoms varies between 6 months and 1 year [3]. Other less frequent signs may be present, such as localized hyperpigmentation of the scar, discharge or bleeding during the first part of the cycle, infertility and dyspareunia [9].

The differential diagnosis of parietal endometriosis includes hernias and eventrations, fibrosis and granulomas, abscesses, hematomas, desmotic tumors, lipomas and primary or secondary malignancies [10]. Radiological exams such as ultrasound help rule out these diagnoses: indeed, the parietal endometriotic nodule appears on ultrasound as a heterogeneous hypoechoic rounded or oval-shaped lesion with irregular hyperechoic contours, with little or no vascularity on color Doppler, located opposite the scar [3]. MRI shows a mainly hypointense or slightly hyperintense heterogeneous lesion with hyperintense areas related to hemorrhagic foci. This lesion enhances after contrast injection [11]. In our case, the lesion appeared to be in contact with the bladder, emphasizing the importance of complementing with an MRI, which provides exhaustive anatomical delineation of the nodule, allowing in particular precise localization of the lesion in relation to the rectus sheath, which is crucial for surgical planning. It also allows the detection of other foci of deep endometriosis [9].

The therapeutic strategy for parietal endometriosis is based on surgery and medical treatment. Suppressant medications such as combined oral contraceptives, Danazol, GnRH agonists, and progesterone provide only temporary relief of symptoms that tend to recur upon cessation of treatment [1]. Nevertheless, they can be used pre-operatively to reduce the size of the nodule and post-operatively to prevent recurrence, especially in patients nearing menopause [2,12]. Interventional radiology methods using minimally invasive percutaneous techniques such as radiofrequency ablation, cryoablation, sclerotherapy and high-intensity focused ultrasound may also be used, but have yet to prove their effectiveness [11].

Surgery remains the treatment of choice for parietal endometriosis, providing the final diagnosis. It consists of wide excision with safety margins of 1 cm. When the lesion size exceeds 4 cm, it is recommended to repair the aponeurotic defect in a single step by placing a retro-muscular mesh [2]. Histopathological examination of the excised nodule confirms the diagnosis of parietal endometriosis by demonstrating endometrial glands, endometrial stroma, and deposits of hemosiderin in adipose and connective tissue [3].

Recurrence is rare but possible, with rates of up to 9.1 %, especially when surgical treatment is inadequate [13].

Regarding the prevention of parietal endometriosis, preventive measures can be adopted, especially during caesarean section: exclusion of the endometrium during hysterorraphy, suturing of the visceral and parietal peritoneum, use of different needles for uterine and abdominal closure and copious washing with physiological saline [2]. However, there is currently no consensus on the ideal method of closure during caesarean section that would effectively reduce the risk of parietal endometriosis [3].

4. Conclusion

With the increasing frequency of caesarean sections, we may encounter parietal endometriosis more frequently. This diagnosis should always be considered in the presence of persistent scar pain, even in the absence of other signs of endometriosis. Surgery remains the ideal treatment and allows, through histological study, to make the final diagnosis. Finally, it is a disease whose pathogenesis has not yet been fully elucidated, and therefore progress should be made in this direction to determine at-risk populations and improve management.

Consent

A consent was obtained from the patient to publish this case report and accompanying images.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is not applicable. The case report is not containing any personal information.

Funding

No funding or grant support.

Guarantor

Hounaida Mahfoud.

Research registration number

Not applicable.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hounaida Mahfoud, Amina Lakhdar: Performed surgery, paper writing and editing.

Najia Zeraidi, Amina Lakhdar, Aziz Baidada: Literature review, supervision.

Hounaida Mahfoud, Samia Tligui, Ibtissam Bensrhir: Manuscript editing, picture editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests relevant to the content of this article.

References

- 1.Cojocari N., Ciutacu L., Lupescu I., Herlea V., Vasilescu M.E., Sirbu Boeţi M.P. Parietal endometriosis: a challenge for the general surgeon. Chirurgia (Bucur.) 2018;113(5):695. doi: 10.21614/chirurgia.113.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marras S., et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. X. Oct. 2019;4 doi: 10.1016/j.eurox.2019.100096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doroftei B., Armeanu T., Maftei R., Ilie O.-D., Dabuleanu A.-M., Condac C. Abdominal wall endometriosis: two case reports and literature review. Medicina (Mex.) Dec. 2020;56(12):727. doi: 10.3390/medicina56120727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Maria N., Kerwan A., Franchi T., Agha R.A. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int J Surg Lond Engl. 2023;109(5):1136. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horton J.D., Dezee K.J., Ahnfeldt E.P., Wagner M. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon’s perspective and review of 445 cases. Am. J. Surg. Aug. 2008;196(2):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding Y., Zhu J. A retrospective review of abdominal wall endometriosis in Shanghai, China. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Off. Organ Int. Fed. Gynaecol. Obstet. Apr. 2013;121(1):41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang P., Sun Y., Zhang C., Yang Y., Zhang L., Wang N., Xu H. Cesarean scar endometriosis: presentation of 198 cases and literature review. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0711-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esquivel-Estrada V., Briones-Garduño J.C., Mondragón-Ballesteros R. Endometriosis implant in cesarean section surgical scar. Cir. Cir. 2004;72(2):113–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coutureau J., Mandoul C., Verheyden C., Millet I., Taourel P. Acute abdominal pain in women of reproductive age: keys to suggest a complication of endometriosis. Insights Imaging. May 2023;14(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s13244-023-01433-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramdani A., Rais K., Rockson O., Serji B., El Harroudi T. Parietal mass: two case reports of rare cesarean scar endometriosis. Cureus. Feb. 2020 doi: 10.7759/cureus.6918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Feky M., Radswiki T. Radiopaedia.org; 2011. Scar Endometriosis.Radiopaedia.org10.53347/rID-15358 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kontostolis S.V., Vitsas A., Boultadakis E., Stamatiou K., Sfikakis P.G. Endometriosis of the abdominal wall. A rare, under-recognized entity causing chronic abdominal wall pain. Hell. J. Surg. Feb. 2012;84(1):76–79. doi: 10.1007/s13126-012-0008-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bektaş H., et al. Abdominal wall endometrioma; a 10-year experience and brief review of the literature. J. Surg. Res. Nov. 2010;164(1):e77–e81. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]