Abstract

Introduction and importance

Primary pancreatic hydatid cysts are exceptionally rare as they have an incidence rate ranging from 0.14 % to 2 %. Due to their extreme rarity, the patient's clinical manifestations are nonspecific. This leads to misdiagnosis and delay in treatment. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach is necessary for the proper treatment of this pathology.

Case presentation

Herewith, we present the rare case of a 46-year-old Middle Eastern female who sought medical attention at our surgical clinic complaining of an acute on-top-of chronic epigastric pain that radiated to the back. It was associated with a reported dark and pale discoloration of the urine and stool, respectively. The preoperative investigative radiological analysis identified a primary pancreatic body mass formation.

Clinical discussion

A meticulous surgical resection of the pancreatic body, tail, and the spleen was performed. Subsequent histopathological analysis of the excised specimens decisively established the diagnosis of a primary pancreatic body hydatid cyst.

Conclusion

Primary pancreatic hydatid cysts are profoundly rare, and their occurrence in the pancreatic body is even rarer. The profound scarcity of published literature on primary pancreatic body hydatid cysts highlights the imperative need for documentation, epidemiological studies, and the development of crucial interventional protocols. After a meticulous review of the published literature, we deduced that ours is the third documented case from our country of a primary pancreatic body hydatid cyst. Furthermore, no other cases beyond these three have been published from our country involving primary pancreatic hydatid cysts.

Keywords: Abdominal Surgery, Case Report, Endocrine System Surgery, Hydatid Cyst, Pancreatic Hydatid Cyst, Zoonotic Parasitic Infection

Highlights

-

•

Echinococcosis is identified as a zoonotic parasitic infection due to the parasitic tapeworm: Echinococcus.

-

•

In terms of prevalence, hydatid cysts occur in the liver (50%-77%), lungs (15%-47%), spleen (0.5%-8%), and kidneys (2%-4%).

-

•

The pancreatic involvement in hydatidosis is even rarer, with a reported incidence ranging from (0.14% to 2%) of all cases.

-

•

Half of these cysts are predominantly positioned in the pancreatic head, (24-34%) in the body and (16-19%) in the tail.

-

•

Surgery with histopathological analysis are the definitive means of therapy and diagnosis in pancreatic hydatidosis.

1. Introduction

Echinococcosis is also identified as hydatid disease and furthermore termed “Hydatidosis”. It is a zoonotic parasitic illness stemming from the parasitic tapeworm Echinococcus. It exhibits a remarkable prevalence in regions such as Mediterranean countries, the Indian subcontinent, Middle East, and South America. Those regions are contemporarily considered endemic areas for this parasitic infection [[1], [2], [3]].

This disease is attributed to four distinct Echinococcus species as all of them are accountable for hydatid disease in humans [4,5]. It is worth noting that Echinococcus Granulosus and Echinococcus Multilocularis are the most rampant culprits in these infectious occurrences. They are accountable for cystic echinococcosis and alveolar echinococcosis, respectively [4,5]. Nevertheless, human cases of Polycystic Echinococcosis are linked to the remaining two species: Echinococcus Oligarthrus and Echinococcus Vogeli.

It is vital to mark that Echinococcus Granulosus alone is responsible for approximately 95 % of the reported human cases of hydatidosis. Within the biological life cycle of hydatid disease, carnivores serve as the definitive hosts, whereas herbivores function as the intermediary hosts. We must not forget that humans themselves play no direct role in this cycle. Nevertheless, they inadvertently contract the disease through the ingestion of Echinococcus eggs found in canine feces [4,5].

This parasitic infection continues to pose substantial public health worries in regions where livestock breeding and agriculture are the primary sources of livelihood for the inhabitants. Despite the potential for hydatid cysts to manifest in almost any human tissue or organ, the liver (50 %–77 %), lungs (15 %–47 %), spleen (0.5 %–8 %), and kidneys (2 %–4 %) are the most frequently affected organs in descending order [[5], [6], [7], [8]].

In contrast, primary pancreatic hydatid cysts are exceedingly rare. Diagnosing the disease proves tricky due to its resemblance to congenital pancreatic cysts, pseudocysts or neoplastic cystic conditions within the pancreas. In endemic areas, primary pancreatic hydatid cyst cases account for a mere (0.2 %–2 %) of all hydatid disease cases [[9], [10], [11]].

A multidisciplinary approach including radiological, medical, and surgical insights is crucial in achieving a timely diagnosis and carrying out the desired treatment outcomes. This will be depicted in detail in this article.

The work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria and the revised 2023 SCARE guidelines [12].

2. Presentation of case

2.1. Patient information

In this article, we present the case of a 46-year-old Middle Eastern female patient who is a known case of Diabetes Mellitus Type II. She presented to our outpatient Surgery clinic complaining of chronic epigastric pain for 1 year before her presentation that became intolerable in the few days leading up to it. The patient reported that the pain was located in the epigastric region, dull in nature, radiated to the back, associated with a single episode of dark discoloration of the urine and pale stool, had no exacerbating or instigating factors, was partially responsive to over-the-counter analgesic medications, and had a numerical patient scale intensity of 07/10.

In the direct assessment of her gastrointestinal system, the patient reported no other symptoms, such as alterations in appetite or bowel movements, nausea, emetic episodes, early satiety, skin discolorations, or bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract.

The patient denied having any other complaints. She further denied undergoing any recent surgeries, trauma, or experiencing any recent infections. Additionally, no B-Symptoms were reported.

The patient's medical history only included the previously mentioned Diabetes Mellitus Type II disease. In relation to that, her drug history included Metformin, but was otherwise negative.

Her vaccination history is complete and she doesn't consume tobacco smoke or alcohol. As for her social history, she lives in the suburbs in a rural area where there are multiple farm animals on the house premises. Some of those animals come in direct contact with the patient on certain occasions, which would explain the results of the final diagnosis.

Her surgical and allergic histories are unremarkable. Prior to experiencing these symptoms, she denied feeling any similar symptoms.

Lastly, the patient denied any family history of congenital pancreatic cysts, pancreatic neoplasia, hydatid cysts, and her overall family history was otherwise unremarkable.

The patient's Body Mass Index at the time of her presentation was 26 Kg/m2.

2.2. Clinical findings

After obtaining the full patient history, we proceeded to conduct a comprehensive physical examination. We began by recording the patient's vital signs, which were within the normal range at that time. Subsequently, a structured examination encompassing abdominal inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation was performed.

Upon inspection, the abdomen was not distended, moved symmetrically with respiration, and the umbilicus was central. We further inspected for any specific skin discolorations, but none were observed.

Superficial palpation resulted in guarding and tenderness over the epigastric region. However, no superficial masses were palpated. On the other hand, deep palpation could not be carried out due to the pain and tenderness felt by the patient.

Percussion findings also included epigastric tenderness and guarding.

Auscultatory findings were unremarkable, and no further abnormalities were detected during the remaining physical examination.

2.3. Diagnostic assessment

During the presurgical assessment phase, the patient underwent the following evaluative radiological tests. Firstly, a transabdominal Ultrasonography (USG) examination was carried out. However, its findings were inconclusive.

Secondly, a high-resolution contrast-enhanced Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed with a pancreatic protocol. It revealed an oval-shaped mass formation with relatively well-demarcated borders. It was found originating from the pancreatic body and measured (3 × 3.5 cm). Additionally, it exhibited a slight increase in contrast material uptake. However, no calcifications were observed (Fig. 1 A-B-C). The remainder of this examination yielded no other remarkable findings as no free fluid, lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, or other lesions were detected. The possible differential diagnoses based on the previous radiological analysis included neoplastic cystic formations (i.e., Cystadenocarcinoma, cystic adenoma, neuroendocrine tumors, and vascular neoplasia). Classical radiological features of pancreatic hydatid cysts were not observed in this case. Therefore, serology to detect echinococcosis was not carried out. Subsequently, an inclusive laboratory workup was conducted. However, no abnormalities were demonstrated.

Fig. 1.

(A-B-C): Preoperative contrast-enhanced CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis revealing an oval-shaped mass formation, depicted by the Red Arrow, that appeared to be originating from the pancreatic body. It measured (3 × 3.5 cm) and its borders were relatively well-demarcated. Moreover, it exhibited slight increase in uptake of contrast material. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Based on the given information, our surgical team opted to resort to a surgical intervention to remove the detected mass.

In preparation for the surgical intervention, blood samples were drawn for blood grouping and crossmatch, and the patient was placed on a nil-per-mouth status. Adequate intravenous access sites were set up, and the necessary preoperative prophylactic antibiotics were administered.

With regard to limitations or weaknesses, we report that no perioperative challenges were encountered in any of the pre-, intra-, or postoperative phases.

2.4. Therapeutic intervention

The surgical operation took place at or specialized tertiary university hospital. We conducted the operation under general anesthesia with no anesthetic complications. In turn, the surgery was successfully accomplished by a General Surgery specialist with 10 years of experience and by a 1st and 2nd senior surgical assistants with 5 and 4 years of experience, respectively.

Through a left subcostal incision, the desired exposure of the surgical field was achieved. A well-defined round mass formation with necrotic and thick pasty material was found in the body of the pancreas. No spillage of contents was observed. The mass was infiltrating the splenic artery and vein. Unfortunately, dissection of the mass from the splenic anatomical components was not possible. For this reason, the pancreatic body, tail, and the spleen were carefully resected (Fig. 2) after meticulous isolation from their respective anatomical surroundings. The pancreatic stump was carefully divided via surgical blade and suture technique. Afterwards, the resected specimens were directly sent to our hospital's specialized Pathology laboratory for the necessary analysis to determine a conclusive diagnosis. It is worth noting that no other findings were seen intraoperatively.

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative image of the resected specimens showing the pancreatic body and tail in addition to the spleen. The location of the mass is identified by the Black Arrow.

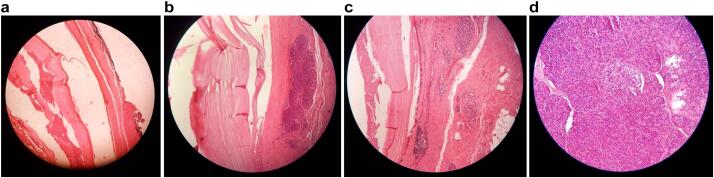

The specimens underwent extensive analysis under the microscope with the use of Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining. The pancreatic tissue was involved by a cystic lesion composed of acellular laminated membranes with an outer fibrotic layer, but no viable protoscolices were observed (Fig. 3 A-B-C-D). Furthermore, no evidence of atypia or malignancy was demonstrated within, and the splenic tissue was regular with no abnormal findings. Conclusively, these results conform to the diagnosis of a primary pancreatic hydatid cyst.

Fig. 3.

A: Histopathological image demonstrating the microscopic analysis of the resected pancreatic specimens. By means of H&E staining, we can see the presence of the acellular laminated membrane with an outer fibrotic layer.

B: Histopathological image demonstrating the microscopic analysis of the resected pancreatic specimens. By means of H&E staining, we can see the presence of the acellular laminated membrane with the normal acinar parenchyma of the pancreas.

C: Histopathological image demonstrating the microscopic analysis of the resected pancreatic specimens. By means of H&E staining, we can see that there is no cyst lining, no papillary projections or columnar mucinous cells, rather just an acellular laminated membrane and fibrotic tissue which exclude any chance of other pancreatic cysts and establish our diagnosis.

D: Histopathological image demonstrating the microscopic analysis of the resected pancreatic specimens. By means of H&E staining, we can see the presence of normal acinar parenchyma of the pancreas with Islets of Langerhans, neighboring the cyst wall.

Postoperatively, the patient successfully ambulated the day following the surgery, her vital signs were normal, and her symptoms were gone. She then received the proper postoperative fluid support and antibiotics to limit the possibility of post-splenectomy infections. Lastly, she was discharged to her home on the 4th postoperative day and was put on an oral Albendazole regimen over the course of 4 months. Furthermore, she was scheduled to receive post-splenectomy vaccines that include vaccinations for pneumococcal disease, meningococcal disease, and for Haemophilus Influenzae Type B.

She has been followed up for 5 months so far. During this period, she received regular physical, laboratory, and radiological assessments that revealed no residual findings.

3. Discussion

Hydatid cysts are theoretically capable of infiltrating any organ or anatomical structure within the human body. Predominantly, they gravitate toward the liver and the lungs. In terms of frequency in the aforementioned organs, they have a prevalence rate of approximately 70 % and 20 % among patients, respectively. With that being said, other organs play host to these cysts, but in much slighter magnitudes [13,14].

Taking the clinical studies into perspective, we deduced that the pancreatic involvement in hydatid disease is remarkably rare as it has a reported incidence ranging from (0.14 % to 2 %). Much of the ongoing clinical debate that encircles primary pancreatic hydatid cysts is related to their diagnosis, natural progression, and therapeutic methods [15].

Therefore, several hypotheses have emerged to elucidate the pathophysiology of Echinococcus Granulosus infiltrating the pancreas, with hematogenous dissemination being the most widely acknowledged pathway [16]. The 2nd postulated pathway entails the migration of cystic elements into the biliary system, which subsequently reach the pancreatic duct and tissue. The 3rd envisioned pathway involves the passage of cystic elements into lymphatic channels through the intestinal mucosa, which eventually infiltrate the pancreatic tissue. The 4th conjectured route entails the straight entry of larvae into pancreatic tissue while bypassing the liver by means of pancreatic veins. The 5th and last theoretical pathway is in the form of retroperitoneal dissemination [6,[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]].

Historical accounts from a 2012 review [19] reveal that in 90 % of cases, the cyst exists as a solitary entity within the pancreas. Furthermore, (50 %) of these cysts are predominantly positioned in the pancreatic head, with (24–34 %) were found the pancreatic body and (16–19 %) were documented in the pancreatic tail. The predilection for primary pancreatic hydatid cysts to manifest in the pancreatic head can be attributed to its incredibly rich blood supply and extensive perfusion [24].

Pancreatic cysts exhibit a gradual growth pattern as they expand at a rate ranging from (0.3 to 2 cm) per year. Moreover, their dimensions vary from mere millimeters to numerous centimeters [25,26].

In terms of presenting symptoms, the clinical presentation of affected patients is variable and this easily results in misdiagnosis. Furthermore, the presentations are chiefly conditional on the cyst's size, site, and concomitant complications. It could keep on being clinically silent. Thus, they get incidentally discovered during unrelated medical investigations [27]. Alternatively, it can present a spectrum of symptoms including left upper quadrant or epigastric pain, the presence of a palpable mass, emesis, nausea, and attacks of fever [26]. We must highlight that the clinical manifestations of the affected patients are diverse because they are contingent on the mass effect or complicating factors. Moreover, cysts positioned in the pancreatic head may, due to external compression effects on the biliary tree and common bile duct, induce obstructive jaundice. They could also sometimes be mistaken for a choledochal cyst [28,29]. Cysts residing in the pancreatic body frequently lie dormant until they reach a size adequately substantial to instigate either symptomatic compression effects on nearby anatomical organs or simply manifest as abdominal masses. In rare instances, cysts situated in the tail of the pancreas may lead to portal hypertension and splenomegaly. Potential complications encompass cystic rupture into the peritoneal cavity or the biliary tree, cholangitis, the formation of a pancreatic fistula, and abscess formation [[30], [31], [32]]. Acute pancreatitis is a rare clinical manifestation but can nonetheless transpire due to obstruction of the pancreatic duct by outside compression result from the cyst or internal blocking by scolices in case they established cyst-ductal communication. Rarer complications entail necrotizing pancreatitis, sinistral portal hypertension especially with lesions situation in the tail of the pancreas, and repeated episodes of pancreatitis [19,26].

In terms of diagnostic assessment, laboratory assessment tools in the form of serological analysis stands as a conventional technique in the identification of hydatid cysts. The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) tests for the presence echinococcal antigens has among individuals afflicted with hepatic hydatidosis a positivity rate of approximately (85 %). In contrast, the seropositive rate diminishes to (54 %) in cases of pancreatic hydatid cysts [26,33]. Yet, we must keep in mind that the negative results of this test do not exclude the presence of hydatidosis.

When discussing the accuracy of radiological assessment tools used to definitively diagnose pancreatic hydatid cysts, we must acknowledge hydatid cysts can readily masquerade as alternative cystic pathologies within the respective afflicted organ. For instance, they might be mistaken for cystic neoplasia of the pancreas or for choledochal cysts [18,34].

In the context of pancreatic cyst diagnosis, the most frequently employed radiological modalities, in descending order of prevalence, encompass Ultrasonography, Computed Tomography, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). In intricate cases warranting further in-depth investigation, diagnostic techniques such as endoscopic ultrasound and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are pursued [35]. In terms of low-risk investigations, USG emerges as not only a noninvasive diagnostic tool that also as a highly sensitive and cost-efficient advantages over the other options. Nevertheless, its utilization in evaluating pancreatic cysts is relatively limited due to the retroperitoneal positioning of the pancreas and the presence of intestinal gas. Conversely, CT scans excel in detailing aspects like cystic dimensions, spatial relationships with the pancreaticobiliary system, and determination of the existence of other cysts in adjacent anatomical structures. It proves efficacious for the surveillance of the treatment progress and uncovering any postsurgical recurrence [19]. Notably, CT scans surpass USG in clarifying the characteristics of hydatid cysts. These include their size, number, margins, configuration, potential calcifications, and anatomical site. Moreover, CT imaging of the abdomen have utility in assessing possible disease complications, such as cystic rupture into the chief pancreatic duct, and monitoring the existing lesions during therapeutic interventions [36]. On the other hand, MRI exhibits a superior ability to discern cyst attributes and complications compared to CT imaging. However, its utilization may be limited by cost considerations, especially for patients [13].

Possible differential diagnoses for hydatid cysts of the pancreas consist of a spectrum of both non-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions. The former includes congenital cysts and pseudocysts of the pancreas, whereas the latter includes cystadenocarcinoma, cystic adenoma, neuroendocrine tumors, metastatic lesions, and vascular neoplasia [22,37,38].

In terms of treatment, a surgical intervention stands as the sole definitive measure of both diagnosis and therapy in the comprehensive management of hydatid cysts of the pancreas [30,31]. Surgery is strongly advocated in the context of pancreatic hydatid cysts to preclude potential subsequent complications [39]. Surgical techniques play a pivotal role in addressing pancreatic hydatid disease, with emphasis on cysts localized in the corpus or tail of the pancreas, for which options encompass central pancreatectomy, distal pancreatectomy, and pericystectomy ∓ concurrent splenectomy [11,19].

In instances where the hydatid cysts are situated within the body or tail of the pancreas, the most sensible technique involves a spleen-conserving distal pancreatectomy [7,35]. In situations where preservation of the spleen is unattainable, fast administration of meningococcal and pneumococcal vaccinations is imperative to mitigate potential infections postsplenectomy complications [8]. Central pancreatectomy may be the desirable choice when cysts are confined to the neck or body of the pancreas [11]. A chief benefit of this technique is the safeguarding of pancreatic parenchyma. This serves to lessen the occurrence of complications such as exocrine pancreatic insufficiency or Diabetes Mellitus [11].

When we correlate between medical treatment and surgical interventions, they constitute an effective multidisciplinary approach in the management of pancreatic hydatid cysts. Pharmacological treatment plays a crucial part in mitigating the risk of cyst recurrence when utilized pre−/postoperatively. The primary therapeutic agent employed is Mebendazole. It is then followed by Albendazole and Praziquantel. However, Albendazole is notably the most efficacious among these pharmaceutical options [40].

Upon our rigorous review of the published literature, we can conclude that ours is the 3rd ever documented case from our country of a primary pancreatic body hydatid cyst with the first two cases being by M.M. Qarmo et al. [41] in 2021 and by Alsaid et al. [42] in 2018.

This case highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach including preoperative radiological analysis, intraoperative surgical technique, postoperative analysis of the histopathological specimens, and postoperative patient care.

4. Conclusion

Primary pancreatic hydatid cysts are profoundly rare. Their occurrence in the pancreatic body is even rarer to occur.

Our case highlights this exceptional scarcity through its detailed presentation and the literature review we conducted.

There is a genuine scarcity of published literature on primary pancreatic body hydatid cysts. This emphasizes the essential need for considering it as a potential differential diagnosis in similar cases. Further documentation, epidemiological studies, and the establishment of necessary interventional protocols are crucial to avoid any potential life-threatening complications.

After conducting an in-depth review of the published literature, we concluded that our case is the 3rd ever documented case of a primary pancreatic body hydatid cyst from our country. Moreover, there have been no other published cases of primary pancreatic hydatid cysts from our country apart from these three cases. This is particularly interesting because we are listed among the endemic regions for hydatidosis. However, primary pancreatic hydatid cysts are almost never seen.

Abbreviations

- USG

Ultrasonography

- CT

Computed Tomography

- H&E

Hematoxylin and Eosin

- ELISA

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- ERCP

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

Consent of patient

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Ethical approval

Institutional review board approval is not required for deidentified single case reports or histories based on institutional policies.

Funding

N/A.

Author contributions

O.A.: Conceptualization, resources, methodology, data curation, investigation, who wrote, original drafted, edited, visualized, validated, literature reviewed the manuscript, and the corresponding author who submitted the paper for publication.

G.A.: Data curation, resources, validation, visualization, reviewing, and editing the manuscript.

H.A.: Pathological analysis of resected specimens, assignment of the final histopathological diagnosis, validation, and review of the manuscript.

E.A.: 2nd surgical assistant during the operation, in addition to data curation, resources, validation, visualization, reviewing, and editing the manuscript.

A.D.: 1st surgical assistant during the operation, in addition to supervision, project administration, and review of the manuscript.

A.H.: General Surgery specialist who supervised the operation, in addition to supervision, project administration, and review of the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Guarantor

Omar Al Laham.

Research registration number

N/A.

Declaration of competing interest

N/A.

Acknowledgements

-Department of Pathology, Al Assad University Hospital, Damascus University, Damascus, (The) Syrian Arab Republic.

-Department of Radiology, Al Assad University Hospital, Damascus University, Damascus, (The) Syrian Arab Republic.

Contributor Information

Omar Al Laham, Email: 3omar92@gmail.com.

Gheed Abdul Khalek, Email: cherryblossomsss11@gmail.com.

Hazar Alboushi, Email: hazarbo94@gmail.com.

Eias Abazid, Email: Eiasabazid25@gmail.com.

Abdo Darwish, Email: Abdo.94273@gmail.com.

Ali Hamza, Email: elielavigne90@gmail.com.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the Data were obtained from the hospital computer-based in-house system. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Altinörs N, Senveli E, Dönmez T, Bavbek M, Kars Z, Sanli M. Management of problematic intracranial hydatid cysts. Infection 1995 Sep-Oct;23(5):283–7. Doi: 10.1007/BF01716287. PMID: 8557386. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Goel M.C., Agarwal M.R., Misra A. Percutaneous drainage of renal hydatid cyst: early results and follow-up. Br. J. Urol. 1995 Jun;75(6):724–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07379.x. (PMID: 7613827) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karakas E., Tuna Y., Basar O., Koklu S. Primary pancreatic hydatid disease associated with acute pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2010 Aug;9(4):441–442. (PMID: 20688612) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akbulut S, Sogutcu N, Eris C. Hydatid disease of the spleen: single-center experience and a brief literature review. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2013 Oct;17(10):1784–95. Doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2303-5. Epub 2013 Aug 15. PMID: 23949423. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Eris C., Akbulut S., Yildiz M.K., Abuoglu H., Odabasi M., Ozkan E., Atalay S., Gunay E. Surgical approach to splenic hydatid cyst: single center experience. Int. Surg. 2013 Oct-Dec;98(4):346-53. Doi doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-13-00138.1. (PMID: 24229022; PMCID: PMC3829062) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wani R.A., Wani I., Malik A.A., Parray F.Q., Wani A.A., Dar A.M. Hydatid disease at unusual sites. Int. J. Case Rep. Images. 2012 Jul 7;3(6):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trigui A., Rejab H., Guirat A., Mizouni A., Ben Amar M., Mzali R., Beyrouti M.I. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas. About 12 cases. 2013;84(2):165–170. (PMID: 23697975) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yarlagadda P, Yenigalla BM, Penmethsa U, Myneni RB. Primary pancreatic echinococcosis. Trop. Parasitol. 2013 Jul;3(2):151–4. Doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.122147. PMID: 24471002; PMCID: PMC3889094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Khiari A, Mzali R, Ouali M, Kharrat M, Kechaou MS, Beyrouti MI. Kyste hydatique du pancréas. A propos de sept observations [Hydatid cyst of the pancreas. Apropos of 7 cases]. Ann Gastroenterol Hepatol (Paris). 1994 May-Jun;30(3):87–91. French. PMID: 8067682. [PubMed]

- 10.Ismail K., Haluk G.I., Necati O. Surgical treatment of hydatid cysts of the pancreas. Int. Surg. 1991;76(3):185–188. (PMID: 1938210) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah O.J., Robbani I., Zargar S.A., Yattoo G.N., Shah P., Ali S., Javaid G., Shah A., Khan B.A. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas. An experience with six cases. JOP. 2010 Nov 9;11(6):575–581. (PMID: 21068489) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Maria N., Kerwan A., Franchi T., Agha R.A. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J.. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2023;109(5):1136. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ammann RW, Eckert J. Cestodes. Echinococcus. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 1996 Sep;25(3):655–89. Doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70268-5. Erratum in: Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1996 Dec;25(4):vii. (PMID: 8863045). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Eckert J., Gemmell M.A., Meslin F.X., Pawlowski Z.S., World Health Organization . World Organisation for Animal Health; 2001. WHO/OIE Manual on Echinococcosis in Humans and Animals: A Public Health Problem of Global Concern. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Javed A., Agarwal G., Aravinda P.S., Manipadam J.M., Puri S.K., Agarwal A.K. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas: a diagnostic dilemma. Trop. Gastroenterol. 2020 Jul 14;41(2):73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Y, Gong J, Xiong W, Yu X, Lu X. Primary pancreatic hydatid cyst: a case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021 Apr 13;21(1):164. Doi: 10.1186/s12876-021-01753-1. PMID: 33849455; PMCID: PMC8045313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Baghbanian Mahmud, et al. Pancreatic Tail Hydatid Cyst as a Rare Cause for Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Case Report (Case Report) 2013. pp. 194–198. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandelia A., Wahal A., Solanki S., Srinivas M., Bhatnagar V. Pancreatic hydatid cyst masquerading as a choledochal cyst. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2012 Nov;47(11):e41–e44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.07.054. (PMID: 23164030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makni A, Jouini M, Kacem M, Safta ZB. Acute pancreatitis due to pancreatic hydatid cyst: a case report and review of the literature. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2012 Mar 24;7(1):7. Doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-7-7. PMID: 22445170; PMCID: PMC3325852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Rayate A., Prabhu R., Kantharia C., Supe A. Isolated pancreatic hydatid cyst: preoperative prediction on contrast-enhanced computed tomography case report and review of literature. Med. J. Dr. DY Patil Univ. 2012 Jan 1;5(1):66–68. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhat N.A., Rashid K.A., Wani I., Wani S., Syeed A. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas mimicking choledochal cyst. Ann. Saudi Med. 2011 Sep-Oct;31(5):536-8. Doi doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.84638. (PMID: 21911995; PMCID: PMC3183692) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bansal V.K., Misra M.C., Krishna A., Kumar S., Garg P., Khan R.N., Loli A., Jindal V. Pancreatic hydatid cyst masquerading as cystic neoplasm of pancreas. Trop. Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct-Dec;31(4):335-7 (PMID: 21568157) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orug T., Akdogan M., Atalay F., Sakarogulları Z. Primary hydatid disease of pancreas mimicking cystic pancreatic neoplasm: report of two cases. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2010 Dec 1;30(6):2057–2060. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lada PE Termengo D., Cáceres G., Sanchez Tacone C., Caballero F., Sonzini Astudillo P. Primary hydatid cyst of the pancreas. Rev. Fac. Cien. Med. Univ. Nac. Cordoba. 2017;74(1):33–36. English. PMID: 28379129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakkaly AE, Merouane N, Dalero O, Oubeja H, Erraji M, Ettayebi F, Zerhouni H. Primary hydatid cyst of the pancreas of the child: a case report. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2017 Jul 28;27:229. Doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.27.229.12853. PMID: 28979631; PMCID: PMC5622817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Akbulut S, Yavuz R, Sogutcu N, Kaya B, Hatipoglu S, Senol A, Demircan F. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas: report of an undiagnosed case of pancreatic hydatid cyst and brief literature review. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2014 Oct 27;6(10):190–200. Doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v6.i10.190. PMID: 25346801; PMCID: PMC4208043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Kısaoğlu A., Özoğul B., Atamanalp S.S., Pirimoğlu B., Aydınlı B., Korkut E. Incidental isolated pancreatic hydatid cyst. Turkiye Parazitol. Derg. 2015 Mar;39(1):75–77. doi: 10.5152/tpd.2015.3293. (PMID: 25917590) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Köylüoğlu G., Oztoprak I. Unusual presentation of pancreatic hydatid cyst in a child. Pancreas. 2002 May;24(4):410–411. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200205000-00013. (PMID: 11961495) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saczek K., Moore S.W., de Villiers R., Blaszczyk M. Obstructive jaundice and hydatid cysts mimicking choledochal cyst. S. Afr. Med. J. 2007 Sep;97(9):831–833. (PMID: 17987705) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masoodi M.I., Nabi G., Kumar R., Lone M.A., Khan B.A., Al Sayari Naseer, K. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas: a case report and brief review. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2011 Aug;22(4):430–432. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2011.0259. (PMID: 21948577) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ousadden A, Elbouhaddouti H, Ibnmajdoub KH, Mazaz K, Aittaleb K. Primary hydatid cyst of the pancreas with a hepatic pedicule compression. Cases J. 2009 Nov 18;2:201. Doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-201. PMID: 20062706; PMCID: PMC2803866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Agrawal S., Parag P. Hydatid cyst of head of pancreas mimicking choledochal cyst. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 Jun 29;(2011) doi: 10.1136/bcr.04.2011.4087. (PMID: 22693192; PMCID: PMC3128356) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedrosa I., Saíz A., Arrazola J., Ferreirós J., Pedrosa C.S. Hydatid disease: radiologic and pathologic features and complications. Radiographics. 2000 May-Jun;20(3):795–817. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.3.g00ma06795. 10835129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibis C., Albayrak D., Altan A. Primary hydatid disease of pancreas mimicking cystic neoplasm. South. Med. J. 2009 May;102(5):529–530. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31819c3bef. (PMID: 19373169) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Derbel F., Zidi M.K., Mtimet A., Hamida M.B., Mazhoud J., Youssef S., Jemni H., Ali A.B., Hamida R.B. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas: a report on seven cases. Arab J. Gastroenterol. 2010 Dec 1;11(4):219–222. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suryawanshi P., Khan A.Q., Jatal S. Primary hydatid cyst of pancreas with acute pancreatitis. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2011;2(6):122–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.02.011. (Epub 2011 Mar 29. PMID: 22096702; PMCID: PMC3199727) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varshney M., Shahid M., Maheshwari V., Siddiqui M.A., Alam K., Mubeen A., Gaur K. Hydatid cyst in tail of pancreas. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 Nov 1;(2011) doi: 10.1136/bcr.03.2011.4027. (PMID: 22673711; PMCID: PMC3207730) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makni A., Chebb F., Jouini J., Kacem M., Ben Z.S. Left pancreatectomy for primary hydatid cyst of the body of pancreas. Ann. Afr. Surg. 2011:8. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dziri C, Dougaz W, Bouasker I. Surgery of the pancreatic cystic echinococcosis: systematic review. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017 Dec 8;2:105. Doi: 10.21037/tgh.2017.11.13. PMID: 29354762; PMCID: PMC5763016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Lo Monte A., Maione C., Napoli N., Sardo F., Giammanco M., Maniscalco A., Buscemi G. Renal hydatidosis. Discussion of a clinical case complicated by post acute pancreatitic cyst. Minerva Chir. 1998;53(7–8):659–662. (PMID: 9793358) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qarmo M.M., Aldirani A.N., Al-Boukhari L.M.J., Moussa F.M., Alkhateeb L.A. A rare case of pancreatic head hydatid cyst. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2021 Jun 30;2021(6):rjab243 doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjab243. (PMID: 34234940; PMCID: PMC8252941) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alsaid B, Alhimyar M, Rayya F. Pancreatic hydatid cyst causing acute pancreatitis: a case report and literature review. Case Rep. Surg. 2018 Mar 5;2018:9821403. Doi: 10.1155/2018/9821403. PMID: 29692941; PMCID: PMC5859870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the Data were obtained from the hospital computer-based in-house system. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.