Abstract

Introduction and importance

Facial skin may experience many clinical manifestations which are numerous and need accurate diagnosis to reach the best treatment immediately and effectively. Dimpling of the skin may be diagnosed improperly due to lack of information related to diseases of dental origin.

The objective of this study is to provide clarity on dental diagnosis and treatment options for extraoral dimpling caused by odontogenic infections.

Case presentation

A 19-year-old girl presented with a dimple on her facial skin developed during the last month before her consultation. The dimple was located where a vertical line from the distal canthus crosses a horizontal line from the nasal alar. No systemic disease was discovered, and the dental history revealed recurrent failure of root canal treatment in the upper first molar.

Clinical discussion

Cutaneous sinuses originating from dental issues are characterized by a connection between the skin surface and a periapical dental abscess, which is caused by a long-dated tooth infection. Due to the patient's previous dental abscess in close proximity to the skin defect, a clinical diagnosis of an odontogenic cutaneous sinus was established.

Conclusion

It is crucial to recognize that skin lesions in the face and neck area can be a result of odontogenic infections. Careful clinical and radiographic examinations should be conducted to accurately diagnose and differentiate these conditions. By identifying the tooth associated with the lesion, unnecessary medications and incorrect interventions can be avoided, ensuring the implementation of appropriate treatment.

Keywords: Odontogenic fistula, Odontogenic pathology, Cutaneous lesion, Fistula

Highlights

-

•

Odontogenic pathologiesmay lead to mismanagement of many facial skin lesions.

-

•

Accurate examinationis essential for establishing an appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

-

•

Cooperation between all specialists is essential for accurate management.

1. Introduction

Cutaneous lesions on the face, caused by dental root infections leading to sinus formation towards the face, are uncommon. As a result, these conditions are often diagnosed inaccurately during the initial presentation to the surgeon [1].

The progression of dermal lesions related to odontogenic origin is influenced by various factors such as bacterial virulence, the patient's defense mechanism, the relatively low resistance of connective tissues in the facial region, the connection between muscle attachments, and the infected tooth. Clinical manifestations of odontogenic lesions on the facial skin can often be mistaken for other clinical conditions, including skin lesions, tuberculosis, actinomyces, carcinoma, and traumatic injuries. Consequently, there is a risk of administering ineffective treatment to the patient due to misdiagnosis [2].

As a consequence of misdiagnosis, patients may undergo unnecessary treatments, such as multiple courses of antibiotics, repeated biopsies, and surgical removal of the cutaneous lesion [3].

The rarity of odontogenic cutaneous fistulas, combined with the absence of dental symptoms, often amplifies the likelihood of diagnostic errors. This is primarily due to the release of pressure from the inflammatory lesion through the fistula orifice on the skin surface. Consequently, treatment failures become more prevalent in such cases [4].

This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE Criteria [5].

This study is registered with the Research Registry by the identifying number: researchregistry(…) and the reference hyperlink is: https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#home/.

2. Case presentation

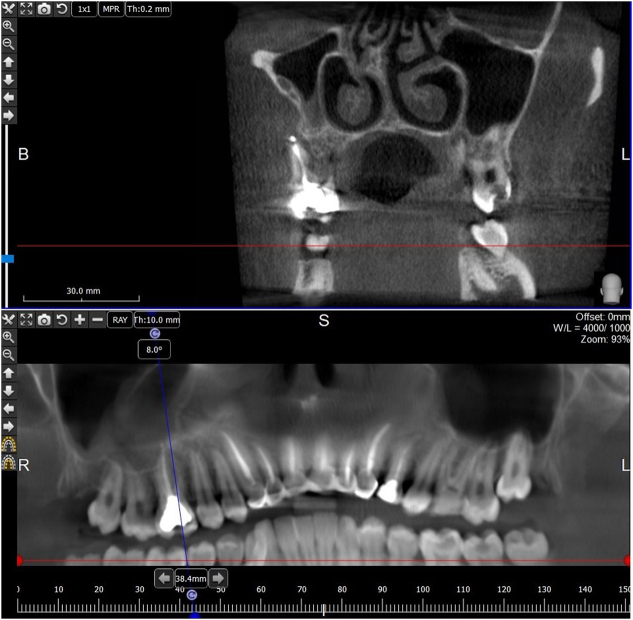

A 19-year-old girl with no systemic diseases presented to The University Hospital. The chief complaint was a decrease on the facial skin surface as shown in Fig. 1. The patient was referred to the oral & maxillofacial surgery department after clinical examination in dermatology department. The patient mentioned a previous swelling at the same site 2 weeks before the dimple appeared. A cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan clarified a considerable defect in the buccal aspect of the upper first molar where the continuity of the buccal plate was impaired (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Asymptomatic decrease on the facial skin surface without any pigmentation or pus.

Fig. 2.

CBCT scan showing bony defect at the apex of mesiobuccal root of upper first molar.

According to the medical history, recurrent endodontic treatment was done for the upper first molar. By palpation, a decrease in the skin surface at the level of the apical region of buccal roots was confirmed. Intraoral examination did not show any clinical manifestations of the bony defect.

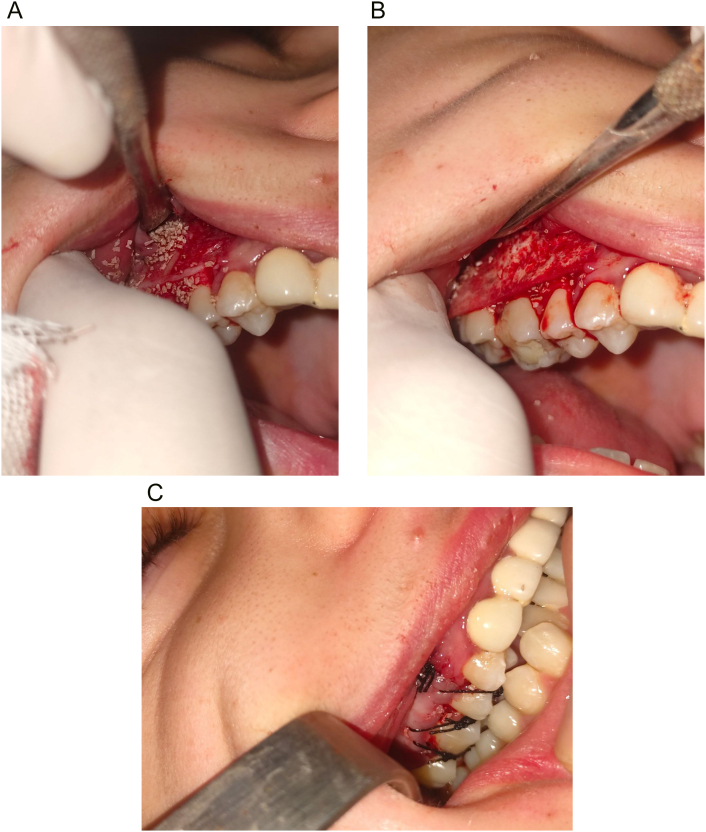

Apicoectomy of the mesiobuccal root of the upper first molar was decided to eliminate the infection (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Apicoectomy of the mesiobuccal root of upper first molar.

The author performed the surgical procedure with the patient under local anesthesia. The recipient site was anesthetized using 2 % lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine. A trapezoidal full-thickness flap was raised to fully expose the buccal aspect of the first molar. A cord like structure appeared during the surgical procedure making raising the flap more difficult. Curettage of the lesion was carried out to remove any surrounding inflammatory tissue including a possible sinus tract. Thus, promoting the healing of the buccal plate. The apex was then removed, and thorough saline irrigation was performed. Finally, the root tip was sealed using MTA®. Following the thorough curettage of the lesion, the buccal plate was augmented by adding bone graft particles derived from dendrophylliae by grinding samples using mechanical grinder (Retsch PM 400®).

After getting the particles, a hydrothermal conversion starts by adding 200 g calcium carbonate and 200 g diammonium phosphate in addition to 50 g monopotassium phosphate as a catalyst for the chemical reaction as Ye xu et al. stated in 2001 [6].

.Augmentation procedure was done to fully restore the resorption that occurred during the infection. The bone graft was covered with collagen membrane®. Interrupted sutures were placed to close the wound using 3/0 silk SURGIReal® (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

a. Application of dendrophylliae bone graft material at the bony defect. b. Coverage of bone graft material using collagen membrane. c. Closure of tension free flap.

2.1. Follow-up

Regular observation was done every 2 days until sutures removal after 7 days of surgical procedure (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Healing of surgical field and sutures removal 7 days postoperatively.

The patient was kept on systemic antibiotics for 7 days and was prescribed amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (Amoxam®) 875/125 mg, twice a day. The patient presented a very good oral health care, leading to ideal healing. The facial skin restored its normal contour without any abnormal aspects. The patient did not experience any pain after the procedure.

Clinical manifestations of the skin dimple reduced significantly after 7 days (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Significant reduction of the facial dimple on the skin surface 7 days postoperatively.

Complete healing and full recovery of the skin surface was noted 2 weeks postoperatively (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Complete disappearance of the facial dimple and full recovery 2 weeks postoperatively.

A cone-beam computed tomography scan was done 3 months postoperatively to check on the status of the graft. The CBCT scan revealed that the bony defect had fully healed, resulting in the complete repair of the discontinuity in the buccal plate (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Buccal plate repair at the apex of the mesiobuccal root.

Later follow-up confirmed full healing after 6 months postoperatively (Fig. 9, Fig. 10).

Fig. 9.

Frontal view confirming full healing 6 months postoperatively.

Fig. 10.

Lateral view confirming full healing 6 months postoperatively.

2.2. Differential diagnosis

Physical examination only is not enough is such clinical manifestations and can lead to misdiagnosis making a possible ineffective treatment. Thus, a recurrence of such clinical appearance due to odontogenic origin. Possible differential diagnosis included epidermoid cyst, parotid gland fistula, chronic osteomyelitis, cystic acne and neoplasms. All these conditions were excluded during thorough clinical and radiographic examination.

3. Discussion

Endodontic treatment is fairly predictable in nature with reported success rates up to 86–98 % [7].

Odontogenic Cutaneous Sinus, a condition originating from dental sources, is a relatively rare but extensively documented condition in medical literature. The diagnosis of Odontogenic Cutaneous Sinus remains a complex task, necessitating meticulous history-taking, clinical examination, and radiographic assessment. Physicians and dentists frequently misdiagnose such cases as skin lesions or non-odontogenic conditions. Hence, it is crucial to achieve an accurate diagnosis and employ appropriate investigative methods to facilitate prompt treatment and minimize complications such as asepsis, osteomyelitis, and patient discomfort [8].

In the case reported in this study, because of the unsuccessful root canal treatment of the upper first molar, the infection spread from the periapical region, disrupted the continuity of the cortical bone, and resulted in the formation of a big defect leading to the formation of a dimple on the facial skin. The use of Thesaurus database aided in our literature search by using the descriptors “dimple, depression”.

Chen et al. [9] stated that practitioners should pay attention to the significance of odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts, as it enables them an accurate diagnosis of this specific clinical manifestation.

Samir et al. described the classic odontogenic cutaneous fistula lesion as an erythematous, smooth, symmetric nodule of up to 2 cm in diameter, with or without drainage, and skin retraction due to healing [10].

Not to mention that other possible skin manifestations include abscesses, gummas, skin tracts, cysts, nodulocystic lesions with suppuration, scars, and ulcers [11].

The novelty concerning this clinical case is that dimpling on the facial skin was clear, not pigmented, does not have an orifice, and without any symptoms. Diagnosis was challenging although the dermatologist referred the patient to the oral and maxillofacial department immediately.

A cordlike structure representing the sinus tract was palpated and this is typical for clinical manifestations of the cutaneous portion of odontogenic sinuses. Perilesional skin can be slightly retracted producing dimpling [12].

The insufficient healing of bone occurs when connective tissue infiltrates the bone space, preventing the process of osteogenesis. To mitigate the risk of soft-tissue ingrowth, bone grafts can be employed to fill sizable bone defects. Although autogenous bone graft is the gold standard of care for treatment of bony defects, reducing the morbidity when taking autogenous grafts in such clinical cases is a must to ensure patient's comfort. The use of dendrophylliae bone graft as a new substitute could make the augmentation procedure easier and more reliable. This approach of grafting bony defect ensures the early establishment of osseous healing, enabling subsequent orthodontic and prosthodontic treatments to be safely and effectively conducted [13].

Typically, patients with facial skin lesions that require surgical intervention are often directed to plastic surgeons. These skin lesions can vary in size, presence of ulcers, discoloration, dimples, and other characteristics. Among these factors, dimples are infrequent and result from skin retraction. Dimples can be associated with conditions such as protuberant dermatofibrosis, sinus tracts of cysts, or ulcerated dimples of carcinoma [14].

Surgeons may face embarrassment if the skin lesions recur or persist after attempting to excise a dimple, suspecting the presence of the aforementioned conditions.

Recurrence of such clinical appearance is due to surgical excision of the sinus tract without management of the underlying odontogenic pathology.

4. Conclusion

it is of paramount importance to maintain a constant awareness that extraoral lesions may have a dental origin, as this knowledge can greatly impact the treatment process and its duration when diagnosed early. Considering this, collaboration among professionals in the fields of endodontics, oral and maxillofacial surgery, plastic surgery, and dermatology is essential. By working together from the initial diagnosis to long-term follow-up, these disciplines can effectively manage such clinical cases and optimize patients' outcomes.

Article citation [15].

Patient perspective

The patient realized the importance of this surgical intervention to obtain satisfying results for aesthetic and functional aims.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this study and accompanying images, a copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of International Journal of Surgery Case Reports.

Ethical approval

Board Name: Scientific Research Board Resolution- Tishreen university, latakia, Syria.

Board Status: Approved Approval no. 710/2021 (23.11.2021).

Funding

This research received no specific grant from the public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Author contribution

Dr. Ashraf Mahlobi: MSc in oral and maxillofacial surgery. The author of the manuscript including performing the surgical procedure.

Dr. Nadim Sleman: MSc in oral and maxillofacial surgery. The author of the manuscript including writing, discussion and reviewing the manuscript.

Dr. Mounzer Assad: PHD in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Supervisor of the treatment plan.

Guarantor

Dr. Ashraf Mahlobi.

Research registration number

This study is registered with the Research Registry by the identifying number: researchregistry9913 and the reference hyperlink is: https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#home/.

Conflict of interest statement

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Ashraf Mahlobi, Email: dr.ashraf.mahlobi@gmail.com.

Nadim Sleman, Email: nfs.nadim@gmail.com.

Mounzer Assad, Email: mounzer962@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Sammut S., Malden N., Lopes V. Facial cutaneous sinuses of dental origin – a diagnostic challenge. Br. Dent. J. 2013;215:55–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azizlou E., Sobhani M.A., Ghabraei S., Khoshkhounejad M., Ghorbanzadeh A., Tahan S.S. Extraoral sinus tracts of odontogenic origin: a case series. Front. Dent. Nov 12 2020;17:29. doi: 10.18502/fid.v17i29.4750. (PMID: 36042809; PMCID: PMC9375119) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mittal N., Gupta P. Management of extra oral sinus cases: a clinical dilemma. J. Endod. 2004;30(7):541–547. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200407000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen K., Liang Y., Xiong H. Diagnosis and treatment of odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts in an 11-year-old boy. Medicine. 2016;95(20) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sohrabi, Catrin BSc, PhD, MBBSa; Mathew, Ginimol BSc, MBBSb; Maria, Nicola MD, MRCSc; Kerwan, Ahmed MBBS, MScd; Franchi, Thomas MBChB, MSc, FHEA, MAcadMEde; Agha, Riaz A MBBS, MSc (Oxon), DPhil (Oxon), MRCS Eng, FHEA, FRSA, FRSPH, FRCS Glasg (Plast), FRCS (Ed), FRCS (Plast), FEBOPRASf; Collaborators. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 109(5):p 1136–1140, May 2023. 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Xu Yewei, Wang Da-zhi, Yang Lan, Tang Honggao. Hydrothermal conversion of coral into hydroxyapatite. Mater. Charact. 2001;47:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song M., Kim H.C., Lee W., Kim E. Analysis of the cause of failure in nonsurgical endodontic treatment by microscopic inspection during endodontic microsurgery. J. Endod. 2011;37:1516–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vermani Mayank, Kalia Vimal, Singh Sumita, Garg Sunny, Aggarwal Shweta, Khurana Richa, Kalra Geeta. Orocutaneous fistula or traumatic infectious skin lesion: a diagnostic dilemma. Case Rep. Dent. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/353069. (4 pages) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, Ke MS; Liang, Yun MS; Xiong, Huacui MS. Diagnosis and treatment of odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts in an 11-year-old boy: a case report. Medicine 95(20):p e3662, May 2016. | DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Samir N., Al-Mahrezi A., Al-Sudairy S. Odontogenic cutaneous fistula: report of two cases. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. Feb 2011;11(1):115–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guevara-Gutiérrez E., Riera-Leal L., Gómez-Martínez M., Amezcua-Rosas G., Chávez-Vaca C.L., Tlacuilo-Parra A. Odontogenic cutaneous fistulas: clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of 75 cases. Int. J. Dermatol. Jan 2015;54(1):50–55. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang LS. Common pitfall of plastic surgeon for diagnosing cutaneous odontogenic sinus. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2018 Dec;19(4):291–295. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2018.02110. Epub 2018 Dec 27. PMID: 30613093; PMCID: PMC6325334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Sreedevi P., Varghese N., Varugheese J.M. Prognosis of periapical surgery using bonegrafts: a clinical study. J. Conserv. Dent. Jan 2011;14(1):68–72. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.80743. (PMID: 21691510; PMCID: PMC3099119) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones K.B., Morcuende J.A., DeYoung B.R., El-Khoury G.Y., Buckwalter J.A., Dietz F.R. Unusual presentation of lipoblastoma as a skin dimple of the thigh: a report of three cases. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2004;86:1040–1046. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200405000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Maria N., Kerwan A., Franchi T., Agha R.A. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2023;109(5):1136. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]