Abstract

Background

There are few data on sex differences in the association between schizophrenia and the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD). We sought to clarify the relationship of schizophrenia with the risk of developing CVDs and to explore the potential modification effect of sex differences.

Methods and Results

We conducted a retrospective analysis using the JMDC Claims Database between 2005 and 2022. The study population included 4 124 508 individuals aged 18 to 75 years without a history of CVD or renal replacement therapy. The primary end point is defined as a composite end point that includes myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, stroke, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and pulmonary thromboembolism. During a mean follow‐up of 1288±1001 days, we observed 182 158 composite end points. We found a significant relationship of schizophrenia with a greater risk of developing composite CVD events in both men and women, with a stronger association observed in women. The hazard ratio for the composite end point was 1.63 (95% CI, 1.52–1.74) in women and 1.42 (95% CI, 1.33–1.52) in men after multivariable adjustment (P for interaction=0.0049). This sex‐specific difference in the association between schizophrenia and incident CVD was consistent for angina pectoris, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation.

Conclusions

Our analysis using a large‐scale epidemiologic cohort demonstrated that the association between schizophrenia and subsequent CVD events was more pronounced in women than in men, suggesting the clinical importance of addressing schizophrenia and tailoring the CVD prevention strategy based on sex‐specific factors.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, epidemiology, schizophrenia, sex difference

Subject Categories: Epidemiology

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

The analysis establishes epidemiologic evidence of a significant association between schizophrenia and the risk of future cardiovascular disease events in both sexes, which is particularly pronounced in women.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Promoting physical activity, especially among women with schizophrenia, is crucial, as inactivity may have increased the risk in female participants in this study.

Health care providers should routinely screen and treat schizophrenia as part of standard clinical practice, with special attention to women.

Recognizing women's mental health as a major risk for cardiovascular disease, we need early detection and collaboration between psychiatrists and cardiologists to prevent heart disease, particularly in women.

Schizophrenia is most common of the primary psychotic disorders. Schizophrenia is a severe chronic mental illness characterized by disturbances in perception, thought, and behavior. 1 There are currently 800 000 individuals with schizophrenia in Japan, and 0.5% of the population will develop schizophrenia during their lifetimes. 2 Individuals with schizophrenia have a shorter life expectancy than the general population and tend to die an average of 25 years earlier. Not only is the suicide rate higher, but most of the risk is attributable to cardiovascular events. 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 The mortality from cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) in individuals with schizophrenia is ≈25%, higher than from cancer. 6 , 7 , 8

There are sex differences in individuals with schizophrenia, with women having a later age of onset and a lower risk of developing schizophrenia than men. 6 , 7 In addition, although it has been reported that there are sex differences in CVD risk among the general population 8 and that mortality is higher in men than in women in individuals with schizophrenia, 9 , 10 sex differences in the association between schizophrenia and CVD risk are not clear. In this study, we examined the potential modification effect of sex differences in the relationship of schizophrenia with incident CVD using a large epidemiologic database.

Methods

This study was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki’s guiding principles and the University of Tokyo’s ethical standards (approved by the university’s ethical committee; permission number 2018‐10862). Because all of the data in the JMDC Claims Database were anonymized and deidentified, the requirement for informed permission was eliminated. The JMDC Claims Database is available for anyone who would purchase it from JMDC Inc (Tokyo, Japan; https://www.jmdc.co.jp/en/). JMDC Inc is a health care venture corporation in Japan.

Study Population

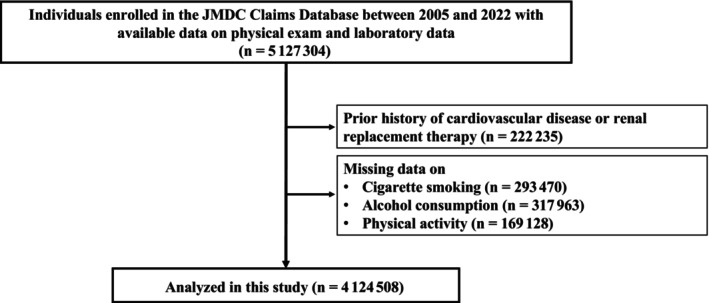

In this observational cohort study, we used the JMDC Claims Database, which is a database of health checkups and administrative claims (both outpatient and inpatient settings) in Japan. 11 , 12 , 13 The JMDC Claims Database covers people in Japan between January 2005 and May 2022, primarily employees and members of their families. The JMDC Claims Database contains administrative claims records reimbursed by insurance (eg, medical diagnoses, pharmaceutical prescriptions) from >60 insurers. Medical diagnoses are registered using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10), coding. Japan has a universal health insurance system. We identified 5 127 304 people using the physical examination and laboratory data from their health checkups. People with a history of CVD, those with renal replacement therapy, and those with missing information on cigarette smoking, alcohol use, or physical activity were all excluded from the study. Finally, we obtained 4 124 508 participants in our study (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart.

We identified 5 127 304 individuals with available health checkup data on physical examination and laboratory data at health checkup in the JMDC Claims Database. We excluded individuals with a history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, stroke, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, pulmonary embolism, and renal replacement therapy, and those with missing data on cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. Finally, we obtained 4 124 508 participants in our study.

Definition of Schizophrenia

Individuals with a history of schizophrenia were defined as those diagnosed with schizophrenia (ICD‐10 codes: F20, F21, F22, F23, F24, F25, F28, and F29) before the initial health checkup.

Variables and Measurement

At the initial health checkup for each participant, we collected the following information using standardized procedures: body mass index, blood pressure, and fasting laboratory values. Information on cigarette smoking (current or noncurrent) was self‐reported. We defined obesity as body mass index of ≥25 kg/m2. 14 Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mm Hg, or taking blood pressure–lowering medications. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose level of ≥126 mg/dL or taking glucose‐lowering medications. Dyslipidemia was defined as low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol level of ≥140 mg/dL, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol level of <40 mg/dL, triglyceride level of ≥150 mg/dL, or taking lipid‐lowering medications. Physical inactivity was defined as failing to walk for an hour each day or failing to exercise for 30 minutes at least twice per week, as we previously mentioned. 15

Outcomes

The outcome data were collected between January 2005 and May 2022. The primary outcome was a composite end point including myocardial infarction (ICD‐10 codes: I210, I211, I212, I213, I214, and I219), angina pectoris (ICD‐10 codes: I200, I201, I208, and I209), stroke (ICD‐10 codes: I630, I631, I632, I633, I634, I635, I636, I638, I639, I600, I601, I602, I603, I604, I605, I606, I607, I608, I609, I610, I611, I613, I614, I615, I616, I619, I629, and G459), heart failure (ICD‐10 codes: I500, I501, I509, and I110), atrial fibrillation (ICD‐10 codes: I480‐I484 and I489), and pulmonary embolism (ICD‐10 codes: I260 and I269). The secondary primary outcomes included myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, stroke, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and pulmonary embolism. The CVDs selected in this study were chosen with reference to the FHS (Framingham Heart Study), which is a well‐known cohort study.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted a sex‐based analysis of the study population. The data are expressed as median (interquartile range) for continuous variables or number (percentage) for categorical variables. The statistical significance of differences in clinical characteristics between participants with and without schizophrenia was assessed using Wilcoxon rank‐sum test and χ2 test, for continuous variables and for categorical variables, respectively. We performed analyses using Cox regression to examine the association between schizophrenia and incident CVD. We calculated hazard ratios (HRs) in an unadjusted model (model 1), an age‐adjusted model (model 2), and after adjustment for age, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical inactivity using the forced entry method (model 3). Multiplicative interaction terms for sex were generated to determine whether the relationship between schizophrenia and incident CVD is modified by sex. We performed a stratified subgroup analysis by age (≥50 versus <50 years), obesity, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and smoking. We performed 5 sensitivity analyses to validate our primary results. First, we set an induction period of 1 year and analyzed 3 324 934 participants. Second, we defined schizophrenia as having a diagnosis of schizophrenia and using antipsychotics (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical code: N05A). In this case scenario, participants having a diagnosis of schizophrenia without the use of antipsychotics (n=10 632) were excluded from the analysis. Third, we imputed missing data on cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical inactivity, as previously described. 16 , 17 Fourth, using the Fine‐Gray subdistribution hazard modeling, we also performed a competing risks analysis because death might be seen as a risk that competes with CVD events. 18 , 19 Fifth, we defined non‐schizophrenia as excluding psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia. For statistical significance, P<0.10 was considered significant for multiplicative interaction terms for sex, and P<0.05 was considered significant for all other analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA, version 17 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

Results

Clinical Characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. The median (interquartile range) age was 44 (36–52) years, and 57% of participants were men. The median (interquartile range) age was 44 (36–52) years in both men and women. Schizophrenia was observed in 15 248 male participants (0.64%) and 16 093 female participants (0.92%). In both men and women, the prevalence of obesity, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and physical inactivity was more common in individuals having schizophrenia.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristic | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia (−) | Schizophrenia (+) | Schizophrenia (−) | Schizophrenia (+) | |||

| (n=2 355 106) | (n=15 248) | P value | (n=1 738 061) | (n=16 093) | P value | |

| Age, y | 44 (36–52) | 44 (37–50) | <0.001 | 44 (36–52) | 44 (37–51) | 0.058 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.2 (21.2–25.6) | 24.2 (21.7–27) | <0.001 | 21 (19.2–23.4) | 22.3 (19.8–25.7) | <0.001 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 724 977 (30.8) | 6409 (42.0) | <0.001 | 278 513 (16.0) | 4766 (29.6) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 121 (112–130) | 120 (111–129) | <0.001 | 112 (102–123) | 112 (102–123) | 0.002 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 75 (68–83) | 75 (68–83) | 0.19 | 69 (62–77) | 69 (62–77) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 521 002 (22.1) | 3492 (22.9) | 0.021 | 220 486 (12.7) | 2282 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 134 299 (5.7) | 1064 (7.0) | <0.001 | 35 740 (2.1) | 662 (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 1 104 434 (46.9) | 8350 (54.8) | <0.001 | 493 907 (28.4) | 6072 (37.7) | <0.001 |

| Cigarette smoking, n (%) | 836 738 (35.5) | 5091 (33.4) | <0.001 | 197 792 (11.4) | 2618 (16.3) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 695 548 (29.5) | 2740 (18.0) | <0.001 | 212 887 (12.2) | 1352 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| Physical inactivity, n (%) | 1 199 910 (50.9) | 8127 (53.3) | <0.001 | 909 363 (52.3) | 9279 (57.7) | <0.001 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL | 93 (87–101) | 93 (87–101) | 0.001 | 89 (84–95) | 90 (85–97) | <0.001 |

| Low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 121 (101–143) | 123 (101–145) | <0.001 | 113 (94–136) | 117 (97–140) | <0.001 |

| High‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 56 (48–66) | 54 (46–64) | <0.001 | 70 (60–81) | 67 (56–78) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 95 (66–142) | 108 (72–166) | <0.001 | 64 (48–90) | 77 (55–115) | <0.001 |

Data are given as median (interquartile range) unless otherwise indicated.

Schizophrenia and CVD in Men and Women

During a mean follow‐up period of 1288±1001 days, 119 827 CVD diagnoses were recorded, and the incidence of CVD was 141.1 (95% CI, 140.3–141.9) per 10 000 person‐years in men, and 62 331 CVD events were recorded, and the incidence of CVD was 112.0 (95% CI, 111.1–112.9) per 10 000 person‐years in women. Compared with participants without schizophrenia, multivariable Cox regression analyses (model 3) demonstrated that HR of schizophrenia for CVD was 1.42 (95% CI, 1.33–1.52) in men and 1.63 (95% CI, 1.52–1.74) in women. The P value for interaction was 0.0049 in model 3, suggesting that the association of schizophrenia with incident CVD was modified by sex (Table 2). The HRs of schizophrenia in men and in women were 1.04 (95% CI, 0.78–1.40) and 1.31 (95% CI, 0.84–2.04) for myocardial infarction, 1.33 (95% CI, 1.20–1.48) and 1.53 (95% CI, 1.38–1.70) for angina pectoris, 1.49 (95% CI, 1.29–1.73) and 1.42 (95% CI, 1.21–1.66) for stroke, 1.42 (95% CI, 1.29–1.56) and 1.80 (95% CI, 1.64–1.97) for heart failure, 1.02 (95% CI, 0.82–1.27) and 1.44 (95% CI, 1.09–1.90) for atrial fibrillation, and 1.93 (95% CI, 1.23–3.04) and 2.78 (95% CI, 1.89–4.08) for pulmonary embolism, respectively. P values for interaction were significant for angina pectoris, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation.

Table 2.

Association of Schizophrenia With Risk of Developing CVD Between Men and Women

| Variable | Men | Women | P value for interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia (−) | Schizophrenia (+) | Schizophrenia (−) | Schizophrenia (+) | ||

| (n=2 355 106) | (n=15 248) | (n=1 738 061) | (n=16 093) | ||

| Composite | |||||

| Events, n | 118 935 | 892 | 61 456 | 875 | |

| Incidence | 140.8 (140.0–141.6) | 192.3 (180.1–205.3) | 111.3 (110.4–112.2) | 190.1 (177.9–203.1) | |

| Unadjusted | 1 (Reference) | 1.37 (1.29–1.47) | 1 (Reference) | 1.71 (1.60–1.83) | <0.001 |

| Age‐adjusted | 1 (Reference) | 1.49 (1.40–1.59) | 1 (Reference) | 1.72 (1.61–1.84) | 0.0027 |

| Multivariable | 1 (Reference) | 1.42 (1.33–1.52) | 1 (Reference) | 1.63 (1.52–1.74) | 0.0049 |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||

| Events, n | 7586 | 45 | 1587 | 20 | |

| Incidence | 8.7 (8.5–8.9) | 9.3 (6.9–12.4) | 2.8 (2.7–2.9) | 4.1 (2.7–6.4) | |

| Unadjusted | 1 (Reference) | 1.08 (0.81–1.45) | 1 (Reference) | 1.49 (0.96–2.31) | 0.2429 |

| Age‐adjusted | 1 (Reference) | 1.20 (0.89–1.61) | 1 (Reference) | 1.50 (0.96–2.33) | 0.4105 |

| Multivariable | 1 (Reference) | 1.04 (0.78–1.40) | 1 (Reference) | 1.31 (0.84–2.04) | 0.3937 |

| Angina pectoris | |||||

| Events, n | 51 757 | 374 | 25 560 | 348 | |

| Incidence | 60.0 (59.5–60.5) | 78.6 (71.0–86.9) | 45.6 (45.0–46.1) | 73.5 (66.2–81.6) | |

| Unadjusted | 1 (Reference) | 1.32 (1.19–1.46) | 1 (Reference) | 1.61 (1.45–1.79) | 0.0070 |

| Age‐adjusted | 1 (Reference) | 1.41 (1.27–1.56) | 1 (Reference) | 1.62 (1.46–1.80) | 0.0634 |

| Multivariable | 1 (Reference) | 1.33 (1.20–1.48) | 1 (Reference) | 1.53 (1.38–1.70) | 0.0645 |

| Stroke | |||||

| Events, n | 25 156 | 187 | 12 615 | 155 | |

| Incidence | 28.9 (28.5–29.3) | 38.8 (33.6–44.8) | 22.4 (22.0–22.7) | 32.4 (27.6–37.9) | |

| Unadjusted | 1 (Reference) | 1.36 (1.17–1.56) | 1 (Reference) | 1.45 (1.24–1.70) | 0.5424 |

| Age‐adjusted | 1 (Reference) | 1.53 (1.32–1.76) | 1 (Reference) | 1.48 (1.26–1.73) | 0.7617 |

| Multivariable | 1 (Reference) | 1.49 (1.29–1.73) | 1 (Reference) | 1.42 (1.21–1.66) | 0.6449 |

| Heart failure | |||||

| Events, n | 57 695 | 434 | 28 579 | 459 | |

| Incidence | 66.9 (66.3–67.4) | 91.0 (82.9–100.0) | 50.9 (50.4–51.5) | 97.2 (88.7–106.5) | |

| Unadjusted | 1 (Reference) | 1.38 (1.26–1.52) | 1 (Reference) | 1.91 (1.74–2.10) | <0.001 |

| Age‐adjusted | 1 (Reference) | 1.51 (1.37–1.66) | 1 (Reference) | 1.92 (1.75–2.11) | <0.001 |

| Multivariable | 1 (Reference) | 1.42 (1.29–1.56) | 1 (Reference) | 1.80 (1.64–1.97) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | |||||

| Events, n | 16 587 | 82 | 4080 | 51 | |

| Incidence | 19.0 (18.7–19.3) | 16.9 (13.6–21.0) | 7.2 (7.0–7.4) | 10.6 (8.0–13.9) | |

| Unadjusted | 1 (Reference) | 0.90 (0.72–1.12) | 1 (Reference) | 1.47 (1.12–1.94) | 0.0060 |

| Age‐adjusted | 1 (Reference) | 1.03 (0.83–1.28) | 1 (Reference) | 1.50 (1.14–1.98) | 0.0330 |

| Multivariable | 1 (Reference) | 1.02 (0.82–1.27) | 1 (Reference) | 1.44 (1.09–1.90) | 0.0567 |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | |||||

| Events, n | 1838 | 19 | 1004 | 27 | |

| Incidence | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) | 3.9 (2.5–6.1) | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) | 5.6 (3.8–8.2) | |

| Unadjusted | 1 (Reference) | 1.90 (1.21–2.99) | 1 (Reference) | 3.17 (2.17–4.65) | 0.0904 |

| Age‐adjusted | 1 (Reference) | 2.06 (1.31–3.24) | 1 (Reference) | 3.17 (2.16–4.64) | 0.1560 |

| Multivariable | 1 (Reference) | 1.93 (1.23–3.04) | 1 (Reference) | 2.78 (1.89–4.08) | 0.2301 |

Data are given as hazard ratio (95% CI) unless otherwise indicated. Multivariable analysis=adjusted for age, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical inactivity. CVD indicates cardiovascular disease.

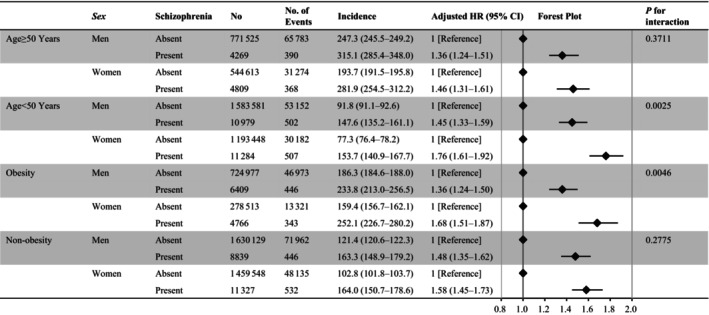

Subgroup Analysis

Compared with participants without schizophrenia, multivariable Cox regression analyses (model 3) demonstrated that schizophrenia was linked to an increased risk of CVD in both men and women, not just in those aged <50 years but also in those aged >50 years. In people who were aged <50 years, the P value for the interaction analyzing the sex difference in the relationship between incident CVD and schizophrenia was statistically significant. In obese people, there was a stronger relationship between schizophrenia and incident CVD in women than in men (Figure 2). Furthermore, the results were consistent across all other subgroups (Figures S1 and S2).

Figure 2. Subgroup analyses.

We examined the association of schizophrenia with the risk of developing cardiovascular disease between men and women stratified by age and obesity. Models were adjusted for age, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical inactivity. HR indicates hazard ratio.

Sensitivity Analyses

First, to remove people with latent CVD at baseline, we included individuals with follow‐up periods >1 year; the main findings were unaffected in this cohort (Table S1). Second, the primary findings remained the same whether schizophrenia was defined as having a diagnosis of schizophrenia and using antipsychotics (Table S2). Third, even with multiple imputations for missing data, our main findings remained consistent (Table S3). Fourth, our main findings were in line with a competing risks model (Table S4). Fifth, considering the impact of psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia on CVD, we excluded patients with psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia from the schizophrenia‐negative group, yet the main results remained consistent (Table S5).

Discussion

The current analysis uses a nationwide health checkup and claims database and provides epidemiologic evidence of a significant relationship between schizophrenia and the risk of developing future CVD events in both sexes, with a more pronounced relationship seen in women than in men. We confirmed the robustness of our primary findings through a variety of sensitivity analyses.

Various potential mechanisms could be suggested for the modification effect of sex differences in the relationship between schizophrenia and the future risk of developing CVD. Women may be more likely to experience schizophrenia during critical periods of hormonal changes, such as during pregnancy or menopause. Because pregnancy or menopause is not only known to worsen mental symptoms of schizophrenia but also to increase the risk of developing CVD, these hormonal changes in women could make a greater impact on cardiovascular health. 20 , 21 More specifically, studies have suggested that the female sex hormone estrogen may have a protective effect on CVD, and decreases in estrogen levels, such as during menopause, may increase CVD risk in women. 22 , 23 , 24 Another potential mechanism underlying the sex difference in the association between schizophrenia and CVD is related to differences in cardiovascular risk factors between men and women. For example, it has been reported that people with schizophrenia are sedentary for up to 11 hours a day, and fewer than one‐half of them meet recommended physical activity levels. 25 As shown in the Table 1, women with schizophrenia may be more likely to be physically inactive. When the relationship between schizophrenia and CVD development was adjusted for physical inactivity, the sex difference was resultantly smaller, indicating that this traditional risk factor may have contributed to our main findings. It might be critical to promote physical activity, especially among women with schizophrenia, as inactivity may have increased risk in female participants of this study.

Because the results of this study indicate that schizophrenia has a deleterious effect on the development of CVD and that this tendency is particularly strong in women, health care providers should incorporate routine screening and treatment of schizophrenia into standard clinical practice for all individuals, in particular, with greater attention to women. We highlight the importance of a thorough, sex‐focused approach to CVD prevention and treatment in light of the significant role of schizophrenia in the development of each cardiovascular outcome. The importance of CVD prevention in women has been strongly recognized in recent years. Therefore, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology have also launched the Go Red for Women campaign (https://www.goredforwomen.org/en/). From this perspective, the findings derived from this study are important from a public health perspective as well. We need to recognize women's mental health more strongly as a risk factor for CVD as well, and to make efforts for early detection; moreover, it is important to share the findings of the present study with psychiatrists who treat schizophrenia, and for psychiatrists and cardiologists to work together to prevent CVD, especially in women. Although various considerations have been made to date, the findings of this study should be validated by independent epidemiologic cohorts and prospective registries, and further research is needed to elucidate the exact mechanism of the modification effect of sex differences in the association between schizophrenia and CVD. In the context of the association between schizophrenia and a risk of developing CVD events, statistically significant differences were observed, indicating an amplified relationship in women compared with men. However, the disparity in HRs is not excessively pronounced, prompting the need for further discussion on whether this difference holds clinical significance.

Limitations

We acknowledge potential limitations in this study. This study is a retrospective observational study using an insurance claims database, and the interpretation of study results requires careful consideration. Although it would be possible to generate a hypothesis on the potential sex difference in the association of schizophrenia with incident CVD based on the findings of the present study, we also need to note that our findings do not definitively conclude the relationship or sex‐specific differences in the risk of CVD associated with schizophrenia. Although a significant difference in the HRs for CVD events in individuals with schizophrenia was observed between men and women, the magnitude of the point estimates was not substantial, warranting further discussion on the clinical significance of such differences. Further research efforts should involve different designs that would enable the collection of more detailed information, such as prospective cohort studies (registry‐based cohorts), to validate our findings. It is important to recognize that diagnoses documented in insurance claims databases are generally regarded as less rigorously validated, introducing a level of uncertainty on the accuracy of diagnoses, especially for conditions. Furthermore, the database under consideration predominantly encompasses a relatively youthful demographic, resulting in a lower occurrence of CVD events. This would raise questions about the adequacy of observed events for each distinct category of CVD. However, the incidence of CVD events in the JMDC Claims Database is comparable to that in other epidemiologic data sets in Japan. 26 , 27 Moreover, previous studies have reported high accuracy in recorded diagnoses, including those for schizophrenia and CVD, in administrative claims databases. 28 , 29 In our study, we took steps to address the uncertainty surrounding schizophrenia diagnoses. We excluded cases with suspected diagnoses and considered only confirmed cases, leading to consistent results in sensitivity analyses where we categorized cases as schizophrenia only when medication specifically prescribed for schizophrenia was noted. It is also important to emphasize that in Japan, the diagnosis of schizophrenia carries significant social and cultural significance, and it is unlikely to be assigned casually in daily clinical practice. Therefore, we believe that our data might reflect real‐world clinical settings in Japan. Given that the JMDC Claims Database mainly includes the working‐age population, whether the findings of this study could be generalized remain unclear, and further investigations using other independent data sets are needed. We should consider the possibility that individuals with severe schizophrenia are not included in this database. Because of the observational nature of this investigation, we are unable to determine whether schizophrenia causes subsequent cardiovascular events. Besides, we used ICD‐10 codes for schizophrenia, which may not be a reliable indicator of the intensity or persistence of schizophrenic symptoms. Potential confounding variables, like socioeconomic status, which may affect the relationship between schizophrenia and subsequent CVD, were not taken into consideration in our study. The difference in socioeconomic position appears to be less significant, nevertheless, given that most of the employees in our study are Japanese employees in rather large organizations. However, other biases and uncontrolled confounding variables may not be addressed. Finally, individuals with schizophrenia may have had poor adherence to treatment for conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, which could have potentially influenced the results. Unfortunately, data on medication adherence were not available for inclusion in this analysis. However, we have added subgroup analyses, as shown in Figures S1 and S2, to exclude the influence of CVD risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and smoking. The results were consistent with the main results, which showed an increased risk of CVD even in individuals without CVD risk, and that risk was higher in women than in men.

Conclusions

We found a robust relationship between schizophrenia and a subsequent risk of developing CVD, and this relationship is more pronounced in women. Our results suggest a need for greater support for individuals (particularly women) with schizophrenia. Psychiatrists, cardiologists, and general physicians should share the findings of this study and apply them to CVD prevention, especially in women.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (21AA2007) and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (20H03907, 21H03159, and 21K08123). The funding sources played no role in the current study.

Disclosures

Drs Kaneko and Fujiu report research funding and scholarship funds from Medtronic Japan CO, LTD, Boston Scientific Japan CO, LTD, Biotronik Japan, Simplex QUANTUM CO, LTD, and Fukuda Denshi, Central Tokyo CO, LTD. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S5

Figures S1–S2

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the entire staff members of our institute's Center for Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine.

This article was sent to Monik C. Jiménez, SM, ScD, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.032625

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 8.

References

- 1. Goldfarb M, De Hert M, Detraux J, Di Palo K, Munir H, Music S, Piña I, Ringen PA. Severe mental illness and cardiovascular disease: JACC state‐of‐the‐art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80:918–933. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baba K, Guo W, Chen Y, Nosaka T, Kato T. Burden of schizophrenia among Japanese patients: a cross‐sectional national health and wellness survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:410. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04044-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ösby U, Correia N, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Sparén P. Mortality and causes of death in schizophrenia in Stockholm County, Sweden. Schizophr Res. 2000;45:21–28. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(99)00191-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212–217. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.3.212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sugawara N, Yasui‐Furukori N, Sato Y, Umeda T, Kishida I, Yamashita H, Saito M, Furukori H, Nakagami T, Hatakeyama M, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among patients with schizophrenia in Japan. Schizophr Res. 2010;123:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mendrek A, Mancini‐Marïe A. Sex/gender differences in the brain and cognition in schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;67:57–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salem JE, Kring AM. The role of gender differences in the reduction of etiologic heterogeneity in schizophrenia. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18:795–819. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00008-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Neil A, Scovelle AJ, Milner AJ, Kavanagh A. Gender/sex as a social determinant of cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2018;137:854–864. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Høye A, Jacobsen BK, Hansen V. Increasing mortality in schizophrenia: are women at particular risk? A follow‐up of 1111 patients admitted during 1980‐2006 in northern Norway. Schizophr Res. 2011;132:228–232. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mortensen PB, Juel K. Mortality and causes of death in first admitted schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:183–189. doi: 10.1192/bjp.163.2.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaneko H, Yano Y, Itoh H, Morita K, Kiriyama H, Kamon T, Fujiu K, Michihata N, Jo T, Takeda N, et al. Association of blood pressure classification using the 2017 American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association blood pressure guideline with risk of heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2021;143:2244–2253. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kaneko H, Itoh H, Yotsumoto H, Kiriyama H, Kamon T, Fujiu K, Morita K, Michihata N, Jo T, Takeda N, et al. Association of isolated diastolic hypertension based on the cutoff value in the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association blood pressure guidelines with subsequent cardiovascular events in the general population. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e017963. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matsuoka S, Kaneko H, Yano Y, Itoh H, Fukui A, Morita K, Kiriyama H, Kamon T, Fujiu K, Seki H, et al. Association between blood pressure classification using the 2017 ACC/AHA blood pressure guideline and retinal atherosclerosis. Am J Hypertens. 2021;34:1049–1056. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpab074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Itoh H, Kaneko H, Kiriyama H, Yoshida Y, Nakanishi K, Mizuno Y, Daimon M, Morita H, Yatomi Y, Yamamichi N, et al. Effect of metabolically healthy obesity on the development of carotid plaque in the general population: a community‐based cohort study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2020;27:155–163. doi: 10.5551/jat.48728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaneko H, Itoh H, Yotsumoto H, Kiriyama H, Kamon T, Fujiu K, Morita K, Michihata N, Jo T, Morita H, et al. Association between the number of hospital admissions and in‐hospital outcomes in patients with heart failure. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:1385–1391. doi: 10.1038/s41440-020-0505-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaneko H, Itoh H, Yotsumoto H, Kiriyama H, Kamon T, Fujiu K, Morita K, Michihata N, Jo T, Morita H, et al. Association of body weight gain with subsequent cardiovascular event in non‐obese general population without overt cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2020;308:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yagi M, Yasunaga H, Matsui H, Morita K, Fushimi K, Fujimoto M, Koyama T, Fujitani J. Impact of rehabilitation on outcomes in patients with ischemic stroke: a nationwide retrospective cohort study in Japan. Stroke. 2017;48:740–746. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morita K, Ono S, Ishimaru M, Matsui H, Naruse T, Yasunaga H. Factors affecting discharge to home of geriatric intermediate care facility residents in Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:728–734. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133:601–609. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brzezinski‐Sinai NA, Brzezinski A. Schizophrenia and sex hormones: what is the link? Front Psych. 2020;11:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O'Kelly AC, Michos ED, Shufelt CL, Vermunt JV, Minissian MB, Quesada O, Smith GN, Rich‐Edwards JW, Garovic VD, El Khoudary SR, et al. Pregnancy and reproductive risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women. Circ Res. 2022;130:652–672. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pérez‐López FR, Larrad‐Mur L, Kallen A, Chedraui P, Taylor HS. Gender differences in cardiovascular disease: hormonal and biochemical influences. Reprod Sci. 2010;17:511–531. doi: 10.1177/1933719110367829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maas AHEM, Van Der Schouw YT, Regitz‐Zagrosek V, Swahn E, Appelman YE, Pasterkamp G, Ten Cate H, Nilsson PM, Huisman MV, Stam HCG, et al. Red alert for womens heart: the urgent need for more research and knowledge on cardiovascular disease in women. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1362–1368. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Regitz‐Zagrosek V, Oertelt‐Prigione S, Prescott E, Franconi F, Gerdts E, Foryst‐Ludwig A, Maas AHEM, Kautzky‐Willer A, Knappe‐Wegner D, Kintscher U, et al. Gender in cardiovascular diseases: impact on clinical manifestations, management, and outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:24–34. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Firth J, Solmi M, Wootton RE, Vancampfort D, Schuch FB, Hoare E, Gilbody S, Torous J, Teasdale SB, Jackson SE, et al. A meta‐review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: the role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:360–380. doi: 10.1002/wps.20773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saito I, Yamagishi K, Kokubo Y, Yatsuya H, Iso H, Sawada N, Inoue M, Tsugane S. Association between mortality and incidence rates of coronary heart disease and stroke: the Japan Public Health Center‐based prospective (JPHC) study. Int J Cardiol. 2016;222:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miura K, Nakagawa H, Ohashi Y, Harada A, Taguri M, Kushiro T, Takahashi A, Nishinaga M, Soejima H, Ueshima H. Four blood pressure indexes and the risk of stroke and myocardial infarction in japanese men and women a meta‐analysis of 16 cohort studies. Circulation. 2009;119:1892–1898. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.823112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yamana H, Moriwaki M, Horiguchi H, Kodan M, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Validity of diagnoses, procedures, and laboratory data in Japanese administrative data. J Epidemiol. 2017;27:476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.je.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fujihara K, Yamada‐Harada M, Matsubayashi Y, Kitazawa M, Yamamoto M, Yaguchi Y, Seida H, Kodama S, Akazawa K, Sone H. Accuracy of Japanese claims data in identifying diabetes‐related complications. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30:594–601. doi: 10.1002/pds.5213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S5

Figures S1–S2