Abstract

Background

We examined the association between cannabis use and cardiovascular outcomes among the general population, among never‐tobacco smokers, and among younger individuals.

Methods and Results

This is a population‐based, cross‐sectional study of 2016 to 2020 data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey from 27 American states and 2 territories. We assessed the association of cannabis use (number of days of cannabis use in the past 30 days) with self‐reported cardiovascular outcomes (coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, and a composite measure of all 3) in multivariable regression models, adjusting for tobacco use and other characteristics in adults 18 to 74 years old. We repeated this analysis among nontobacco smokers, and among men <55 years old and women <65 years old who are at risk of premature cardiovascular disease. Among the 434 104 respondents, the prevalence of daily and nondaily cannabis use was 4% and 7.1%, respectively. The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for the association of daily cannabis use and coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, and the composite outcome (coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke) was 1.16 (95% CI, 0.98–1.38), 1.25 (95% CI, 1.07–1.46), 1.42 (95% CI, 1.20–1.68), and 1.28 (95% CI, 1.13–1.44), respectively, with proportionally lower log odds for days of use between 0 and 30 days per month. Among never‐tobacco smokers, daily cannabis use was also associated with myocardial infarction (aOR, 1.49 [95% CI, 1.03–2.15]), stroke (aOR, 2.16 [95% CI, 1.43–3.25]), and the composite of coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke (aOR, 1.77 [95% CI, 1.31–2.40]). Relationships between cannabis use and cardiovascular outcomes were similar for men <55 years old and women <65 years old.

Conclusions

Cannabis use is associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, with heavier use (more days per month) associated with higher odds of adverse outcomes.

Keywords: cannabis, cardiovascular, nonsmoking

Subject Categories: Cardiovascular Disease, Epidemiology, Risk Factors

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Cannabis use is associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, with higher odds of events associated with more days of use per month, controlling for demographic factors and tobacco smoking.

Similar increases in risk associated with cannabis use are found in never‐tobacco smokers.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Patients should be screened for cannabis use and advised to avoid smoking cannabis to reduce their risk of premature cardiovascular disease and cardiac events.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BRFSS

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

Cannabis use is increasing in the US population. 1 From 2002 to 2019, past‐year prevalence of US adult cannabis use increased from 10.4% to 18.0%, whereas daily/almost daily use (300+ days per year) increased from 1.3% to 3.9%. Rising diagnoses of cannabis use disorder suggest that this increase in use is not confined to reporting of use. 2 , 3 At the same time, perceptions of the harmfulness of cannabis are decreasing. National surveys reported that adult belief in great risk of weekly cannabis use fell from 50% in 2002 to 28.6% in 2019. 4 Despite common use, little is known about the risks of cannabis use and, in particular, the cardiovascular disease risks. Cardiovascular‐related death is the leading cause of mortality, and cannabis use could be an important, unappreciated risk factor leading to many preventable deaths. 5

There are reasons to believe that cannabis use is associated with atherosclerotic heart disease. Endocannabinoid receptors are ubiquitous throughout the cardiovascular system. 6 Tetrahydrocannabinol, the active component of cannabis, has hemodynamic effects and may result in syncope, stroke, and myocardial infarction. 7 , 8 , 9 Smoking, the predominant method of cannabis use, 10 may pose additional cardiovascular risks as a result of inhalation of particulate matter. 11 Furthermore, studies in rats have demonstrated that secondhand cannabis smoke exposure is associated with endothelial dysfunction, a precursor to cardiovascular disease. 11 Past studies on the association between cannabis use and cardiovascular outcomes have been limited by the dearth of adults with frequent cannabis use. 7 , 12 , 13 Moreover, most studies have been in younger populations at low risk for cardiovascular disease, and therefore without sufficient power to detect an association between cannabis use and atherosclerotic heart disease outcomes. 7 , 12 , 14

In addition, tobacco use among adults who use cannabis is common, and small sample sizes prevented analyses on the association of cannabis use with cardiovascular outcomes among nontobacco users. Any independent effects of cannabis and tobacco in the general adult population and effects of cannabis use among those who have never smoked tobacco cigarettes is of interest, because some have questioned whether cannabis has any effect beyond that of being associated with concurrent tobacco use. 15 , 16 , 17 The National Academy of Sciences report on the health effects of cannabis use suggested that “testing the interaction between cannabis and tobacco use and performing stratified analyses to test the association of cannabis use with clinical endpoints in nonusers of tobacco” is necessary to elucidate the effect of cannabis use on cardiovascular health independent of tobacco use. 12 We performed these tests and controlled for potential confounders.

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is a national cross‐sectional survey performed annually by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Beginning in 2016, an optional cannabis module was included supporting an analysis examining the association of cannabis use with cardiovascular outcomes. 18 Although there have been 3 other studies examining the association of cannabis use with cardiovascular events using the BRFSS cannabis module, 19 , 20 , 21 our much larger sample size enabled us to investigate whether cannabis use was associated with atherosclerotic heart disease outcomes among the general adult population, among nontobacco cigarette users, and among younger adults.

Methods

Study Sample

We combined 2016 to 2020 BRFSS data from 27 American states and 2 territories participating in the cannabis module during at least 1 of these years (Table S1). BRFSS is a telephone survey that collects data from a representative sample of US adults on risk factors, chronic conditions, and health care access. 18 The BRFSS questions used are summarized in Table S2. Because this study was based on publicly available data and exempt from institutional review board review, informed consent was not obtained. The data and corresponding materials that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Our sample included those 18 to 74 years old from the BRFSS (N=434 104) who answered the question, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use marijuana or hashish?”, excluding (<1%) those who answered “Don't know” or refused to answer. We excluded adults >74 years old because cannabis use is uncommon in this population.

Measures

We quantified cannabis use as a continuous variable, days of cannabis use in the past 30 days divided by 30. Thus, daily cannabis use is scored 1, and less than daily use scores were proportionately lower. Specifically, daily use was scored as 1=30/30, 15 days per month was scored 0.5=15/30, and nonuse was scored 0=(0/30). Nonusers’ score was 0. Therefore, a 1‐unit change in our cannabis use frequency metric is equivalent to a comparison of 0 days of cannabis use within past 30 days to daily cannabis use.

Demographic variables included age, sex, and self‐identified race and ethnicity. Socioeconomic status was represented by educational attainment, categorized as less than high school, high school, some college, or college graduate.

Cardiovascular risk factors included tobacco cigarette use (never, former, current), current alcohol consumption (nonuse, nondaily use, daily use), body mass index, diabetes, and physical activity. Nicotine e‐cigarette use was similarly classified as never, former, or current.

Outcomes were assessed when respondents were asked, “Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional ever told you that you had any of the following….?”. Coronary heart disease (CHD) was assessed by: “(Ever told) you had angina or coronary heart disease?” The lifetime occurrence of myocardial infarction (MI): “(Ever told) you had a heart attack, also called a myocardial infarction?” Stroke: “(Ever told) you had a stroke?” Finally, we created composite indicator for cardiovascular disease, which included any CHD, MI, or stroke.

Statistical Analysis

Complete case‐weighted estimates of demographic and socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and chronic conditions were calculated using survey strata, primary sampling units clusters, and sampling weights for the 5 years of combined data to obtain nationally representative results for the states using the cannabis module. 22 P values for bivariate analyses were calculated by the Rao‐Scott corrected χ2 test.

We conducted 3 multivariable logistic analyses of the association of lifetime occurrence of CHD, MI, stroke, and the composite of the 3 with cannabis use ([days per month]/30) as a function of demographic and socioeconomic factors, health‐related behaviors, and other chronic conditions, accounting for the complex survey design. The first analysis included the entire sample 18 to 74 years old controlling for tobacco cigarette use and other covariates. The second was conducted among the respondents who had never used tobacco cigarettes. The third was conducted among respondents who had never used tobacco cigarettes or e‐cigarettes. In the first analysis, we tested for an interaction between current cannabis use (any cannabis use frequency between 1 and 30 days) and current tobacco cigarette use to see if there were synergistic effects of cannabis and conventional tobacco use by measuring the coefficient. An interaction was coded as present if frequency of cannabis use was at least 1 day per month, and conventional tobacco use was coded as current. In addition, we examined the variance inflation factors for the cannabis and tobacco use variables to ensure that they were quantifying statistically independent effects. An upper bound of 5 for the variance inflation factor was used for determination of independent effects. 23

We performed supplemental analyses restricting the 3 main analyses to younger adults at risk for premature cardiovascular disease, which we defined as men <55 years old and women <65 years old. The difference in age cutoff by sex is due to the protective effect of estrogen. 24 We also conducted sensitivity analyses limiting the comparison to daily versus nonusers using the same multivariate model as in the main analysis and using propensity‐score matching (details in Data S1).

We used R statistical software version 4.0 (R Core Team, 2020, Vienna, Austria) and survey package to produce complex survey‐adjusted statistics. 25 , 26 We used the package car to estimate the survey‐adjusted variance inflation factors. 27

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Among the 434 104 respondents 18 to 74 years old who answered the cannabis module, the weighted prevalence of daily cannabis use was 4.0%, nondaily use was 7.1% (median: 5 days per month; interquartile range, 2–14), and nonuse was 88.9%. The most common form of cannabis consumption was smoking (73.8% of current users). The mean age of the respondents was 45.4 years. About half (51.1%) were women, and the majority of the respondents were White (60.2%), whereas 11.6% were Black, 19.3% Hispanic, and 8.9% other race and ethnicity (eg, non‐Hispanic Asian, Native American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, and those self‐reporting as multiracial) (Table 1). Daily alcohol use and physical activity had a prevalence of 4.3% and 75.0%, respectively. Most of the sample had never used tobacco cigarettes (61.1%). The prevalence of CHD, MI, stroke, and the composite outcome of all 3 were 3.5% (N=20 009), 3.6% (N=20 563), 2.8% (N=14 922), and 7.4% (N=40 759), respectively. The percentage of missing values for each variable was <1% of the total sample size except for race (1.64%) and alcohol use (1.06%).

Table 1.

Distribution of Sociodemographic Factors, Health‐Related Behaviors, and Comorbidities Among Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Respondents 18 to 74 Years Old

| Characteristic | Total (N=434 104*) | Daily cannabis use (N=12 331*) | Nondaily cannabis use (N=23 049*) | No cannabis use (N=398 724*) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, y | |||||

| 18–34 | 30.5 (30.2–30.9) | 49.8 (48.1–51.5) | 49.8 (48.5–51.0) | 28.1 (27.8–28.5) | <0.001 |

| 35–64 | 55.0 (54.7–55.4) | 45.3 (43.6–47.0) | 43.8 (42.5–45.0) | 56.3 (56.0–56.6) | |

| 65+ | 14.5 (14.3–14.7) | 4.9 (4.3–5.5) | 6.5 (6.0–7.0) | 15.6 (15.4–15.8) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 51.1 (50.8–51.4) | 35.1 (33.5–36.7) | 40.8 (33.5–36.7) | 52.6 (52.3–53.0) | <0.001 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| White | 60.2 (59.9–60.5) | 60.6 (58.8–62.3) | 61.4 (60.1–62.7) | 60.1 (59.8–60.4) | <0.001 |

| Black | 11.6 (11.4–11.9) | 16.2 (14.7–17.6) | 13.0 (12.0–14.0) | 11.3 (11.1–11.6) | |

| Hispanic | 19.3 (19.0–19.6) | 15.7 (14.2–17.1) | 16.8 (15.8–17.9) | 19.7 (19.4–19.9) | |

| Other† | 8.9 (8.6–9.1) | 7.6 (6.8–8.5) | 8.7 (8.0–9.5) | 8.9 (8.7–9.2) | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 13.0 (12.8–13.3) | 16.2 (14.8–17.7) | 10.2 (9.3–11.1) | 13.1 (12.9–13.4) | <0.001 |

| High school | 27.6 (27.4–27.9) | 36.6 (34.9–38.2) | 27.0 (25.9–28.2) | 27.3 (27.0–27.6) | |

| Some college | 31.9 (31.6–32.2) | 34.6 (33.0–36.3) | 39.1 (37.9–40.4) | 31.2 (30.9–31.5) | |

| Graduated college | 27.4 (27.2–27.7) | 12.6 (11.7–13.5) | 23.6 (22.7–24.6) | 28.4 (28.1–28.7) | |

| Substance use | |||||

| Tobacco cigarette smoking | |||||

| Never smoker | 61.1 (60.8–61.4) | 28.6 (27.0–30.2) | 44.6 (43.4–45.9) | 63.9 (63.6–64.2) | <0.001 |

| Former smoker | 22.5 (22.3–22.8) | 26.6 (25.1–28.0) | 25.2 (24.1–26.2) | 22.1 (21.8–22.4) | |

| Current smoker | 16.4 (16.1–16.6) | 44.5 (43.1–46.6) | 30.2 (29.0–31.4) | 14.0 (13.7–14.2) | |

| Alcohol | |||||

| Nonuse | 48.1 (47.8–48.5) | 31.9 (30.4–33.4) | 22.9 (21.8–24.0) | 50.9 (50.5–51.2) | <0.001 |

| Nondaily use | 47.6 (47.3–47.9) | 58.7 (57.0–60.3) | 69.9 (68.8–71.1) | 45.3 (45.0–45.7) | |

| Daily use | 4.3 (4.1–4.4) | 9.5 (8.5–10.4) | 7.2 (6.6–7.8) | 3.8 (3.7–3.9) | |

| Chronic conditions | |||||

| Obese | 32.1 (31.8–32.4) | 25.5 (23.9–27.0) | 24.0 (23.9–26.0) | 33.0 (32.7–33.3) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 10.6 (10.4–10.8) | 6.1 (5.3–6.8) | 5.3 (4.8–5.8) | 11.2 (11.0–11.5) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity | 75.0 (74.8–75.3) | 75.6 (74.1–77.1) | 81.6 (80.7–82.6) | 74.5 (74.1–74.8) | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 3.5 (3.4–3.6) | 2.9 (2.5–3.4) | 2.5 (2.2–2.9) | 3.6 (3.5–3.7) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3.6 (3.5–3.7) | 3.6 (3.1–4.1) | 2.9 (2.6–3.3) | 3.7 (3.6–3.8) | 0.003 |

| Stroke | 2.8 (2.7–2.9) | 3.4 (2.9–3.9) | 2.5 (2.1–2.8) | 2.8 (2.7–2.9) | 0.014 |

| Composite (coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, stroke) | 7.4 (7.2–7.6) | 7.3 (6.6–8.1) | 6.0 (5.4–6.5) | 7.5 (7.4–7.7) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as weighted percent (95% CI). Percentage in each subgroup per column.

Numbers are unweighted.

Includes non‐Hispanic Asian, Native American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, and those self‐reporting as multiracial.

There were significant differences in demographics, outcomes, and tobacco and alcohol use between adults who used cannabis daily, nondaily, and not at all within the past 30 days (Table 1). There was a higher prevalence of current tobacco use and daily alcohol use among adults who use cannabis daily and nondaily compared with not at all (P<0.001 for all). There were significant differences in the distribution of CHD (P<0.001), MI (P=0.003), stroke (P=0.014), and the composite of CHD, MI, and stroke (P<0.001) between respondents reporting daily, nondaily, and nonuse of cannabis, with the lowest point estimates among the nondaily users (Table 1). However, cannabis users had a lower prevalence of other cardiovascular risk factors (less obesity, less diabetes, lower age, higher education) besides tobacco and alcohol use.

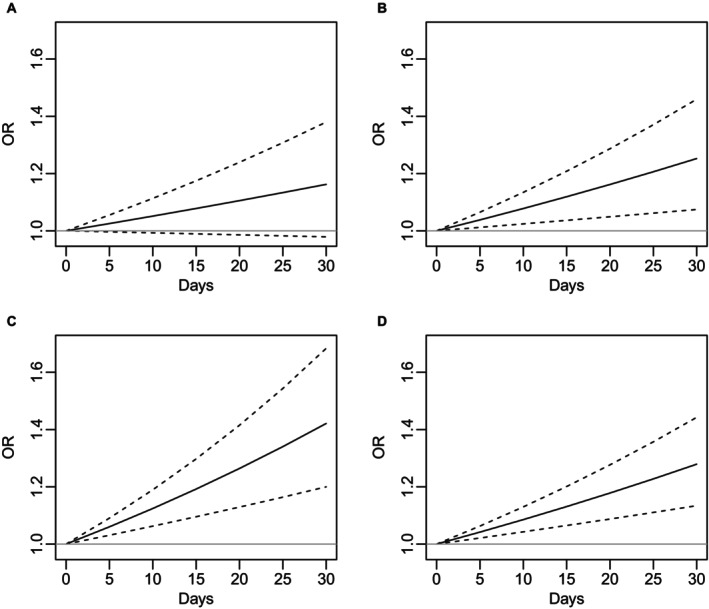

Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes in the General Population

The multivariate survey‐adjusted logistic regression analysis of the entire sample did not reach a significant association between daily cannabis use and CHD (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.16 [95% CI, 0.98–1.38]; P=0.09) (Table 2). However, there was a significant association between cannabis use and MI, with an aOR of 1.25 (95% CI, 1.07–1.46), meaning that there was a 25% increased odds of MI among adults using cannabis daily compared with nonuse, with lower odds for less than daily use. Controlling for other risk factors, cannabis use had similar dose–response relationships with stroke (aOR, 1.42 [95% CI, 1.20–1.68]) and the composite of CHD, MI, and stroke (aOR, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.13–1.44]; Table 2). The Figure shows the full dose–response fit curves and 95% CIs. When testing for the independence of current cannabis use and current tobacco cigarette use, the interaction was nonsignificant (P>0.20) for all outcomes (Table S3). The variance inflation factors for current cannabis use and current tobacco cigarette use were all <2.2.

Table 2.

Association Between Days of Cannabis Use Per 30 Days and Cardiovascular Outcomes and Covariates in Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Respondents 18 to 74 Years Old*

| Variable | CHD | MI | Stroke | Composite outcome of CHD, MI, stroke |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis use† | 1.16 (0.98–1.38) | 1.25 (1.07–1.46)‡ | 1.42 (1.20–1.68)‡ | 1.28 (1.13–1.44)‡ |

| Former smoker | 1.73 (1.60–1.87)‡ | 1.77 (1.64–1.92)‡ | 1.47 (1.34–1.61)‡ | 1.64 (1.55–1.74)‡ |

| Current smoker | 1.94 (1.75–2.16)‡ | 2.63 (2.38–2.90)‡ | 2.08 (1.89–2.30)‡ | 2.16 (2.01–2.32)‡ |

| Age per 10 y | 1.86 (1.80–1.92)‡ | 1.87 (1.81–1.93)‡ | 1.62 (1.57–1.67)‡ | 1.79 (1.75–1.83)‡ |

| Men | 1.69 (1.58–1.81)‡ | 2.07 (1.93–2.22)‡ | 1.13 (1.04–1.21)‡ | 1.56 (1.48–1.64)‡ |

| Black race | 0.71 (0.62–0.82)‡ | 0.82 (0.72–0.94)‡ | 1.51 (1.35–1.68)‡ | 1.02 (0.93–1.11) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.78 (0.69–0.88)‡ | 0.77 (0.67–0.87)‡ | 0.64 (0.55–0.75)‡ | 0.76 (0.69–0.83)‡ |

| Other§ | 0.95 (0.79–1.15) | 0.99 (0.84–1.17) | 1.07 (0.91–1.27) | 1.00 (0.89–1.14) |

| BMI | 1.02 (1.02–1.03)‡ | 1.02 (1.01–1.02)‡ | 1.01 (1.00–1.01)‡ | 1.02 (1.01–1.02)‡ |

| Diabetes | 2.40 (2.21–2.61)‡ | 2.28 (2.10–2.46)‡ | 1.98 (1.81–2.17)‡ | 2.26 (2.12–2.4)‡ |

| Nondaily alcohol use | 0.68 (0.63–0.73)‡ | 0.67 (0.63–0.73)‡ | 0.62 (0.57–0.68)‡ | 0.66 (0.63–0.70)‡ |

| Daily alcohol use | 0.74 (0.62–0.89)‡ | 0.70 (0.59–0.84)‡ | 0.72 (0.62–0.85)‡ | 0.72 (0.64–0.81)‡ |

| High school diploma | 0.80 (0.70–0.90)‡ | 0.74 (0.66–0.83)‡ | 0.75 (0.66–0.85)‡ | 0.75 (0.69–0.82)‡ |

| Some college | 0.82 (0.72–0.94)‡ | 0.69 (0.61–0.77)‡ | 0.73 (0.64–0.82) | 0.72 (0.66–0.79)‡ |

| College degree | 0.68 (0.59–0.78)‡ | 0.49 (0.44–0.56)‡ | 0.53 (0.47–0.61)‡ | 0.55 (0.50–0.60)‡ |

| Physical activity | 0.75 (0.69–0.81)‡ | 0.72 (0.67–0.78)‡ | 0.64 (0.59–0.69)‡ | 0.70 (0.66–0.74)‡ |

Data are presented as adjusted odds ratio (95% CI). BMI indicates body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; and MI, myocardial infarction.

Adjusting for tobacco cigarette use, age, sex, race, BMI, diabetes, alcohol use, educational attainment, and physical activity.

Days used in past 30 days divided by 30. Nonuse scored as 0/30=0, use 15 days/month scored as 15/30=0.5, and daily use scored 30/30=1; therefore, adjusted odds ratios correspond to risk of daily use compared with nonuse.

Statistical significance, P<0.05.

Includes non‐Hispanic Asian, Native American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, and those self‐reporting as multiracial.

Figure 1. Dose–response correlation graph of the magnitude of the OR for the association between days of cannabis use per month and adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

A, CHD. B, MI. C, Stroke. D, Composite outcome of CHD, MI, and stroke. The OR and 95% CI show that the association is significant for every outcome except CHD. CHD indicates coronary heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction; and OR, odds ratio.

As suggested by the lack of interaction between current cannabis use and tobacco use, results were similar among adults who had never used tobacco cigarettes. There were significant differences in the distribution of cardiovascular events between respondents reporting daily, nondaily, and nonuse of cannabis, with the lowest point estimates among the nondaily users (Table 3). Cannabis use was not associated with CHD but was associated with higher odds of MI (aOR, 1.49 [95% CI, 1.03–2.15]) versus tobacco‐adjusted odds in the whole sample (aOR, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.07–1.46]), stroke (aOR, 2.16 [95% CI, 1.43–3.25] versus aOR, 1.42 [95% CI, 1.20–1.68]), and the composite outcome of CHD, MI, and stroke (aOR, 1.77 [95% CI, 1.31–2.40] versus aOR, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.13–1.44]) in respondents 18 to 74 years old (Table 4).

Table 3.

Distribution of Sociodemographic Factors, Health‐Related Behaviors, and Comorbidities Among Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Respondents Who Have Never Used Tobacco Cigarettes

| Characteristic | Total (N=252497*) | Daily cannabis use (N=2892*) | Nondaily cannabis use (N=8864*) | No cannabis use (N=240741*) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, y | |||||

| 18–34 | 35.9 (35.5–36.3) | 64.0 (60.9–67.2) | 65.7 (63.9–67.4) | 33.7 (33.3–34.1) | <0.001 |

| 35–64 | 52.1 (51.6–52.5) | 31.8 (28.8=34.8) | 30.5 (28.8–32.2) | 53.7 (53.2–54.1) | |

| 65+ | 12.0 (11.8–12.2) | 4.2 (3.1–5.2) | 3.8 (3.3–4.4) | 12.6 (12.4–12.9) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 55.5 (55.0–55.9) | 36.4 (33.2–39.7) | 44.6 (42.7–46.5) | 56.5 (56.0–56.9) | <0.001 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| White | 54.3 (53.9–54.7) | 47.4 (44.0–50.8) | 52.0 (50.0–53.9) | 54.6 (54.1–55.0) | <0.001 |

| Black | 13.1 (12.7–13.4) | 22.6 (19.6–25.8) | 15.9 (14.2–17.5) | 12.7 (12.4–13.0) | |

| Hispanic | 22.5 (22.2–22.9) | 22.6 (19.5–25.8) | 22.5 (20.8–24.3) | 22.5 (22.2–22.9) | |

| Other† | 10.1 (9.8–10.4) | 7.3 (5.6–8.9) | 9.6 (8.4–10.9) | 10.2 (9.9–10.5) | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 11.2 (10.9–11.5) | 10.3 (7.9–12.7) | 4.7 (3.9–5.5) | 11.6 (11.1–11.9) | <0.001 |

| High school | 25.0 (24.7–25.4) | 33.4 (30.2–36.7) | 25.1 (23.4–26.8) | 24.8 (24.5–25.2) | |

| Some college | 30.7 (30.3–31.1) | 40.0 (36.6–43.4) | 41.7 (39.7–43.7) | 29.9 (29.5–30.3) | |

| Graduated college | 33.1 (32.7–33.4) | 16.3 (14.4–18.2) | 28.4 (26.9–30.0) | 33.7 (33.3–34.0) | |

| Substance use | |||||

| Alcohol | |||||

| Nonuse | 51.3 (50.9–51.7) | 28.5 (25.6–31.4) | 21.0 (19.4–22.7) | 53.4 (53.0–53.9) | <0.001 |

| Nondaily use | 46.3 (45.9–46.7) | 64.3 (61.1–67.5) | 75.5 (73.8–77.1) | 44.3 (43.9–44.8) | |

| Daily use | 2.4 (2.3–2.5) | 7.2 (5.5–9.0) | 3.5 (2.9–4.1) | 2.2 (2.1–2.3) | |

| Chronic conditions | |||||

| Obese | 31.0 (30.6–31.4) | 26.1 (23.1–29.0) | 23.0 (21.5–24.6) | 31.6 (31.2–32.0) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 9.0 (8.7–9.2) | 5.5 (4.1–7.0) | 3.5 (2.9–4.1) | 9.3 (9.1–9.6) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity | 77.7 (77.4–78.1) | 80.6 (77.7–83.4) | 86.8 (85.6–88.1) | 77.2 (76.8–77.5) | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 2.2 (2.1–2.3) | 2.0 (1.0–2.9) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 2.3 (2.1–2.4) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2.0 (1.9–2.1) | 1.7 (1.1–2.3) | 1.3 (0.9–1.7) | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) | 0.004 |

| Stroke | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) | 2.6 (1.6–3.5) | 1.0 (0.7–1.2) | 1.9 (1.8–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Composite (coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, stroke) | 4.8 (4.6–4.9) | 4.9 (3.5–6.2) | 2.7 (2.1–3.2) | 4.9 (4.7–5.1) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as weighted percent (95% CI). Percentage in each subgroup per column.

Numbers are unweighted.

Includes non‐Hispanic Asian, Native American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, and those self‐reporting as multiracial.

Table 4.

Association Between Days of Cannabis Use Per 30 Days and Cardiovascular Outcomes and Covariates in Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Respondents 18 to 74 Years Old Who Have Never Used Tobacco Cigarettes*

| Variable | CHD | MI | Stroke | Composite outcome of CHD, MI, stroke |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis use† | 1.45 (0.88–2.40) | 1.49 (1.03–2.15)‡ | 2.16 (1.43–3.25)‡ | 1.77 (1.31–2.40)‡ |

| Age per 10 y | 1.86 (1.77–1.95)‡ | 1.88 (1.78–1.99)‡ | 1.61 (1.53–1.69)‡ | 1.77 (1.71–1.83)‡ |

| Men | 1.71 (1.53–1.91)‡ | 1.97 (1.75–2.22)‡ | 1.11 (0.98–1.25) | 1.50 (1.39–1.63)‡ |

| Black race | 0.80 (0.66–0.98)‡ | 0.94 (0.75–1.17) | 1.63 (1.38–1.94)‡ | 1.14 (1.00–1.29)‡ |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.90 (0.75–1.07) | 0.85 (0.71–1.03) | 0.63 (0.50–0.79)‡ | 0.82 (0.72–0.93)‡ |

| Other§ | 0.90 (0.66–1.22) | 0.85 (0.64–1.13) | 0.76 (0.58–1.00)‡ | 0.87 (0.71–1.08) |

| BMI | 1.03 (1.02–1.04)‡ | 1.02 (1.01–1.03)‡ | 1.02 (1.01–1.03)‡ | 1.02 (1.02–1.03)‡ |

| Diabetes | 2.36 (2.07–2.69)‡ | 2.17 (1.91–2.47)‡ | 2.12 (1.84–2.45)‡ | 2.19 (1.99–2.41)‡ |

| Nondaily alcohol use | 0.76 (0.67–0.85)‡ | 0.74 (0.65–0.84)‡ | 0.64 (0.56–0.73)‡ | 0.71 (0.65–0.77)‡ |

| Daily alcohol use | 0.85 (0.65–1.11) | 0.72 (0.55–0.95)‡ | 0.77 (0.57–1.05) | 0.79 (0.65–0.95)‡ |

| High school diploma | 0.78 (0.61–1.01) | 0.72 (0.57–0.91)‡ | 0.77 (0.60–0.99)‡ | 0.73 (0.62–0.87)‡ |

| Some college | 0.80 (0.62–1.04) | 0.65 (0.51–0.82)‡ | 0.78 (0.61–1.00)‡ | 0.72 (0.60–0.85)‡ |

| College degree | 0.72 (0.55–0.93)‡ | 0.49 (0.39–0.62)‡ | 0.59 (0.46–0.75)‡ | 0.58 (0.49–0.69)‡ |

| Physical activity | 0.65 (0.57–0.73)‡ | 0.68 (0.59–0.77)‡ | 0.6 (0.52–0.69)‡ | 0.64 (0.58–0.70)‡ |

Data are presented as adjusted odds ratio (95% CI). BMI indicates body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; and MI, myocardial infarction.

Adjusting for tobacco cigarette use, age, sex, race, BMI, diabetes, alcohol use, educational attainment, and physical activity.

Days used in past 30 days divided by 30. Nonuse scored as 0/30=0, use 15 days/month scored as 15/30=0.5, and daily use scored 30/30=1; therefore, adjusted odds ratios correspond to risk of daily use compared with nonuse.

Statistical significance, P<0.05.

Includes non‐Hispanic Asian, Native American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, and those self‐reporting as multiracial.

Among those who had never used tobacco cigarettes and had never used e‐cigarettes, cannabis use was not associated with CHD or MI but was associated with stroke (aOR, 2.24 [95% CI, 1.31–3.83]) versus tobacco‐adjusted odds in the whole sample (aOR, 1.42 [95% CI, 1.20–1.68]), and the composite outcome of CHD, MI, and stroke (aOR, 1.63 [95% CI, 1.12–2.38] versus aOR, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.13–1.44]) in respondents 18 to 74 years old (Table S4).

Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among Younger Adults

The supplemental analyses of the respondents restricted to younger adults at risk for premature cardiovascular disease (men <55 years old and women <65 years old) demonstrated similar associations between cannabis use and cardiovascular outcomes. Cannabis use was significantly associated with CHD (aOR, 1.30 [95% CI, 1.00–1.67]), MI (aOR, 1.30 [95% CI, 1.04–1.62]), stroke (aOR, 1.56 [95% CI, 1.25–1.95]), and the composite outcome of CHD, MI, and stroke (aOR, 1.36 [95% CI, 1.16–1.61]; Table S5). When testing for the independence of current cannabis use and current tobacco cigarette use, the interaction was nonsignificant (P>0.50 for all; Table S6), and the variance inflation factors for current cannabis use and current tobacco cigarette use were <3.5.

In those who had never used tobacco cigarettes and at risk for premature cardiovascular disease (men <55 years old, women <65 years old), cannabis use was significantly associated with CHD (aOR, 2.36 [95% CI, 1.25–4.45]), stroke (aOR, 2.40 [95% CI, 1.42–4.07]), and the composite of CHD, MI, and stroke (aOR, 2.13 [95% CI, 1.44–3.13]; Table S7).

Among these younger (men <55 years old, women <65 years old) respondents who had never used tobacco cigarettes and e‐cigarettes, cannabis use was significantly associated with stroke (aOR, 2.51 [95% CI, 1.22–5.14]) and the composite outcome of CHD, MI, and stroke (aOR, 1.82 [95% CI, 1.06–3.11]; Table S8).

Association of Smoked Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes in the General Population

The sensitivity analyses that limited cannabis users to those who primarily used smoking as the method of cannabis consumption showed similar associations between smoked cannabis use and cardiovascular outcomes. Smoked cannabis use was significantly associated with MI (aOR, 1.26 [95% CI, 1.04–1.52]), stroke (aOR, 1.50 [95% CI, 1.22–1.85]), and the composite of CHD, MI, or stroke (aOR, 1.30 [95% CI, 1.12–1.51]; Table S9).

Sensitivity Analyses Limiting the Analysis to Daily Versus Nonusers

Comparing daily users to nonusers (ie, excluding nondaily users) yielded similar ORs as the main analysis that assumed a dose–response proportional to days per month used (Table S10). The results of the propensity‐matched analysis are similar to the analysis comparing daily with nonusers with the original multivariate approach described in the article, except that the OR for MI drops below statistical significance (P=0.08), probably due to the smaller sample size of the propensity‐matched sample (Table S10).

Discussion

Past 30‐day cannabis use was associated with MI, stroke, and composite outcomes of CHD, MI, and stroke among adults 18 to 74 years old, controlling for tobacco smoking status, age, sex, race and ethnicity, body mass index, diabetes, alcohol use, educational attainment, and physical activity. This effect exhibited a dose–response relationship, with more days of use associated with higher risks (Figure). Among adults at risk for premature cardiovascular disease, cannabis use was associated CHD, MI, stroke, and composite of CHD, MI, and stroke when controlling for the same variables.

We performed 6 analyses that illustrated the robustness of these findings, regardless of tobacco cigarette use. First, we investigated whether an interaction variable between current cannabis use and current tobacco cigarette use was significant for these outcomes. It was not; the interaction was nonsignificant (P>0.20 for all outcomes), and the variance inflation factors for current cannabis use and current tobacco smoking were all <2.2, indicating that current tobacco cigarette use and current cannabis use have independent associations with the cardiovascular outcomes of interest. Second, this evidence is reinforced by the finding of an association between cannabis use and cardiovascular outcomes in those who had never used tobacco cigarettes. Third, in the much smaller subgroup analysis of those who never used tobacco cigarettes and e‐cigarettes (N=176 963), cannabis use had a strong positive association with stroke and the composite outcome of CHD, MI, and stroke.

Moreover, our supplemental analyses show that the positive relationships between cannabis use and adverse cardiovascular outcomes are similar but larger for younger adults at risk of premature cardiovascular disease. Similarly, the interaction between current cannabis use and current tobacco cigarette use was not significant, and variance inflation factors were low, also demonstrating that among this younger subset of respondents, current cannabis use and current tobacco cigarette use have an independent association with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Furthermore, our sensitivity analyses restricting the sample to daily use and nonuse and implemented by the main multivariate model, as well as the propensity‐score matched analysis, show similar results.

The independent effects of cannabis and tobacco cigarette use in the general adult population and effects of cannabis use among those who never used tobacco cigarettes are notable, because some have questioned whether cannabis use has any effect beyond that of being associated with tobacco use, despite the shared mechanism of inhaling particulate matter. 15 , 16 , 17 We found that, after controlling for potential confounders, cannabis use has a strong independent effect in the general population and a strong association with cardiovascular outcomes independent of the effects of using tobacco cigarettes and e‐cigarettes. In addition, the 95% CIs for the cardiovascular risks of cannabis and tobacco use overlap both in the multivariate analysis of all respondents and the analysis of never‐tobacco cigarette smokers, suggesting that smoking cannabis and smoking tobacco have similar independent additive risks. This is particularly important, because cannabis use is increasing and conventional tobacco use is decreasing.

The associations between cannabis use and cardiovascular outcomes have generally focused on lifetime use or any use within the past year, past month, or concurrent International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) diagnostic codes for cannabis dependent and nondependent abuse. 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 Three previous studies have used pooled BRFSS data to investigate the relationship between cannabis use and stroke, MI, and the combined outcome of MI and CHD. 19 , 20 , 21 These studies found a significant association between frequent cannabis use and their 3 cardiovascular outcomes of interest. Our analysis was similar but is based on a sample 3 to 17 times larger than prior studies. In particular, our sample was large enough that we could investigate the association of cannabis use with cardiovascular outcomes in a subsample that included only those who had never used tobacco cigarettes, and a second smaller subset of those who had never used tobacco cigarettes and e‐cigarettes. We also accounted for number of days used per month as a continuous variable. This analysis is important, because it suggests that cannabis use alone may be a risk factor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Among US adults, cannabis use is increasing in both prevalence and frequency, whereas conventional tobacco smoking is declining in prevalence. 4 , 35 , 36

Limitations

First, our study is limited by its cross‐sectional design. Although prospective studies are needed to confirm our findings, reverse causality (eg, participants experienced an MI and started using cannabis) is an unlikely explanation for our findings. Multiple studies have examined reasons for cannabis use, which include chronic pain, insomnia, and anxiety. 37 Coronary heart disease, MI, and stroke are not reported as reasons for cannabis use. 37 Nevertheless, there is an urgent need for prospective cohort studies that examine the association of cannabis use and cardiovascular outcomes, accounting for frequency of use.

Second, cardiovascular conditions were evaluated by self‐report and therefore subject to recall bias, but self‐report of cardiovascular disease using similar questions has been validated against medical records. 38 , 39

Third, cannabis use is self‐reported within the BRFSS. However, this is the established standard for population observational studies on tobacco use, as concluded by the Surgeon General in 2020. 40 , 41 Self‐report using standard questions that have been validated against medical records is an accepted method used to assess substance use and is used widely in epidemiological surveys and cohort studies. 42 The agreement between self‐report and urine test for prenatal cannabis use was poor to moderate, but there is more stigma about cannabis use by pregnant women than others. 43 Agreement between self‐report of cannabis use and biochemical validation of cannabis use was much greater for those sustaining traumatic injury. 44 Moreover, any nonreported cannabis use would bias our results to the null, making our conclusions conservative.

Fourth, although we had data on several important cardiovascular risk factors (tobacco use, body mass index, diabetes), we did not have data on participants' baseline lipid profile or blood pressure.

Fifth, we compared BRFSS respondents in states that administered the optional cannabis module (in‐sample) to respondents in states that did not administer the cannabis module and found small differences (Table S11).

Sixth, because BRFSS data are anonymized, the respondents' answers cannot be linked to death records, so we cannot analyze the effect of the cannabis use on total mortality or cardiac mortality.

Seventh, the large proportion of users being young confounds this study in an important way. For atherosclerotic disease, the process evolves over decades. Therefore, the contribution of cannabis use to atherosclerosis development is likely not yet fully reflected in the BRFSS data. If the adverse impact is related to endothelial activation, then the effects are likely reversible, similar to chronic tobacco use or the impact of clean indoor air legislation on MI rates. However, if there is a contribution to atherosclerosis development, then the impact is underestimated due to the age distribution of the cohort.

Conclusions

Cannabis has strong, statistically significant associations with adverse cardiovascular outcomes independent of tobacco use and controlling for a range of demographic factors and outcomes. It remains positively associated with cardiovascular disease among the general population, and men <55 years old and women <65 years old, those who have never use tobacco cigarettes, and those who have never used tobacco cigarettes or e‐cigarettes. These data suggest that cannabis use may be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and may be a risk factor for premature cardiovascular disease. Patients and policymakers need to be informed of these potential risks, especially given the declining perception of risk associated with cannabis use.

Sources of Funding

Dr Jeffers was supported by National Cancer Institute grant T32 CA113710. Dr Jeffers and Dr Keyhani were supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant 1R01HL130484‐01A1. The funding organizations are public institutions and had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the article; and decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosures

Dr Glantz serves as a consultant to the World Health Organization outside the submitted work. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Data S1

Tables S1–S11

Acknowledgments

A.M.J.: conceptualization, methodology, software, and writing–original draft. S.G.: methodology, writing–review and editing. A.L.B.: methodology, writing–review and editing. S.K.: resources, writing–review and editing, supervision, and funding acquisition. Dr Jeffers had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

This article was sent to Kolawole W. Wahab, MD, Guest Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.030178

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

References

- 1. Carliner H, Brown QL, Sarvet AL, Hasin DS. Cannabis use, attitudes, and legal status in the U.S.: a review. Prev Med. 2017;104:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Han BH, Palamar JJ. Trends in cannabis use among older adults in the United States, 2015‐2018. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:609–611. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Sarvet AL. Time trends in US cannabis use and cannabis use disorders overall and by sociodemographic subgroups: a narrative review and new findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45:623–643. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2019.1569668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality . Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deaths and mortality . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm.

- 6. Pacher P, Steffens S, Hasko G, Schindler TH, Kunos G. Cardiovascular effects of marijuana and synthetic cannabinoids: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:151–166. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Page RL, Allen LA, Kloner RA, Carriker CR, Martel C, Morris AA, Piano MR, Rana JS, Saucedo JF, American Heart Association Clinical Pharmacology Committee and Heart Failure Transplantation Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Basic Cardiovascular Sciences; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research . Medical marijuana, recreational cannabis, and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e1–e22. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ghasemiesfe M, Ravi D, Casino T, Korenstein D, Keyhani S. Acute cardiovascular effects of marijuana use. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:969–974. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05235-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richards JR, Blohm E, Toles KA, Jarman AF, Ely DF, Elder JW. The association of cannabis use and cardiac dysrhythmias: a systematic review. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020;58:861–869. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2020.1743847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Steigerwald S, Wong PO, Cohen BE, Ishida JH, Vali M, Madden E, Keyhani S. Smoking, vaping, and use of edibles and other forms of marijuana among U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:890–892. doi: 10.7326/M18-1681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang X, Derakhshandeh R, Liu J, Narayan S, Nabavizadeh P, Le S, Danforth OM, Pinnamaneni K, Rodriguez HJ, Luu E, et al. One minute of marijuana secondhand smoke exposure substantially impairs vascular endothelial function. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003858. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine . The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. The National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Geissler KH, Kaizer K, Johnson JK, Doonan SM, Whitehill JM. Evaluation of availability of survey data about cannabis use. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e206039. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ravi D, Ghasemiesfe M, Korenstein D, Cascino T, Keyhani S. Associations between marijuana use and cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:187–194. doi: 10.7326/M17-1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Falkstedt D, Wolff V, Allebeck P, Hemmingsson T, Danielsson AK. Cannabis, tobacco, alcohol use, and the risk of early stroke: a population‐based cohort study of 45 000 Swedish men. Stroke. 2017;48:265–270. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kawada T. Letter by Kawada regarding article, "cannabis, tobacco, alcohol use, and the risk of early stroke: a population‐based cohort study of 45 000 Swedish men". Stroke. 2017;48:e132. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rana JS, Auer R, Reis JP, Sidney S. Risk of cardiovascular disease among young adults: marijuana use or the company it keeps. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1559–1560. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020.. Accessed November 4, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html

- 19. Parekh T, Pemmasani S, Desai R. Marijuana use among young adults (18‐44 years of age) and risk of stroke: a Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey analysis. Stroke. 2020;51:308–310. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.027828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shah S, Patel S, Paulraj S, Chaudhuri D. Association of marijuana use and cardiovascular disease: a Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data analysis of 133,706 US adults. Am J Med. 2021;134:614–620.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ladha KS, Mistry N, Wijeysundera DN, Clarke H, Verma S, Hare GMT, Mazer CD. Recent cannabis use and myocardial infarction in young adults: a cross‐sectional study. CMAJ. 2021;193:E1377–E1384. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. CDC . Complex Sampling Weights and Preparing 2020 BRFSS Module Data for Analysis. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2020/pdf/Complex‐Smple‐Weights‐Prep‐Module‐Data‐Analysis‐2020‐508.pdf

- 23. Glantz SASB, Neilands TB. Multicollinearity and what to do about it. In: Glantz SASB, Neilands TB, eds. Primer of Applied Regression and Analysis of Variance. McGraw Hill; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mendelsohn M, Lobo R. Cardiovascular health and the menopause–an approach for gynecologists: an overview. Climacteric. 2006;9:1–5. doi: 10.1080/13697130600916163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; 4.0. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2020. R version 4.0. The R Project for Statistical Computing. Accessed January 1, 2020. https://www.r‐project.org/.

- 26. Lumley T. Survey: Analysis of Complex Survey Samples, R package version 4.2 . 2023. https://cran.r‐project.org/web/packages/survey/index.html

- 27. Fox J, Monette G. R and S‐Plus Companion to Applied Regression. Sage Publications, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sidney S, Beck JE, Tekawa IS, Quesenberry CP, Friedman GD. Marijuana use and mortality. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:585–590. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rumalla K, Reddy AY, Mittal MK. Recreational marijuana use and acute ischemic stroke: a population‐based analysis of hospitalized patients in the United States. J Neurol Sci. 2016;364:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.01.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rumalla K, Reddy AY, Mittal MK. Association of recreational marijuana use with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hemachandra D, McKetin R, Cherbuin N, Anstey KJ. Heavy cannabis users at elevated risk of stroke: evidence from a general population survey. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40:226–230. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Winhusen T, Theobald J, Kaelber DC, Lewis D. The association between regular cannabis use, with and without tobacco co‐use, and adverse cardiovascular outcomes: cannabis may have a greater impact in non‐tobacco smokers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020;46:454–461. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2019.1676433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reis JP, Auer R, Bancks MP, Goff DC Jr, Lewis CE, Pletcher MJ, Rana JS, Shikany JM, Sidney S. Cumulative lifetime marijuana use and incident cardiovascular disease in middle age: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:601–606. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen X, Chen DG, Yu B. Investigating cumulative marijuana use and risk of cardiovascular disease in middle age with longitudinal data. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:e11–e12. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. The Health Consequences of Smoking – 50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. Atlanta, GA. 2014. Accessed online on Jan 1, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/consequences‐smoking‐exec‐summary.pdf

- 36. Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, Homa DM. Tobacco product use among adults–United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:397–405. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7111a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Azcarate PM, Zhang AJ, Keyhani S, Steigerwald S, Ishida JH, Cohen BE. Medical reasons for marijuana use, forms of use, and patient perception of physician attitudes among the US population. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1979–1986. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05800-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tretli S, Lund‐Larsen PG, Foss OP. Reliability of questionnaire information on cardiovascular disease and diabetes: cardiovascular disease study in Finnmark county. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1982;36:269–273. doi: 10.1136/jech.36.4.269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ. Agreement between self‐report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA. E‐cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: a meta‐analysis. Am J Public Health. 2021;111:230–246. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation . A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. 2020.

- 42. Murphy DA, Hser YI, Huang D, Brecht ML, Herbeck DM. Self‐report of longitudinal substance use: a comparison of the UCLA natural history interview and the addiction severity index. J Drug Issues. 2010;40:495–516. doi: 10.1177/002204261004000210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Skelton KR, Donahue E, Benjamin‐Neelon SE. Validity of self‐report measures of cannabis use compared to biological samples among women of reproductive age: a scoping review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:344. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-04677-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Salottolo K, McGuire E, Madayag R, Tanner AH II, Carrick MM, Bar‐Or D. Validity between self‐report and biochemical testing of cannabis and drugs among patients with traumatic injury: brief report. J Cannabis Res. 2022;4:29. doi: 10.1186/s42238-022-00139-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Tables S1–S11