Abstract

Micheliolide (MCL) is a chief constituent of plants such as Magnolia grandiflora L., Michelia compressa (Maxim.) Sarg. and Michelia champaca L. It is known to exhibit significant anticancer activity by various scientific investigations. This review aims to emphasize the anticancer and antiinflammatory activities of MCL. In this review, we summarized the published data in peer-reviewed manuscripts published in English. Our search was based on the following scientific search engines and databases: Scopus, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Springer, PubMed, and SciFinder, MCL possesses a broad spectrum of medicinal properties like other sesquiterpene lactones. The anticancer activity of this compound may be attributed to the modulation of several signaling cascades (PI3K/Akt and NF-κB pathways). It also induces apoptosis by arresting the cell cycle at the G1/G0 phase, S phase, and G2/M phase in many cancer cell lines. Very little data is available on its modulatory action on other signaling cascades like MAPK, STAT3, Wnt, TGFβ, Notch, EGFR, etc. This compound can be potentiated as a novel anticancer drug after thorough investigations in vitro, in vivo, and in silico-based studies.

Keywords: Micheliolide, A sesquiterpene lactone, Magnolia grandiflora L, Anticancer, Anti-inflammatory

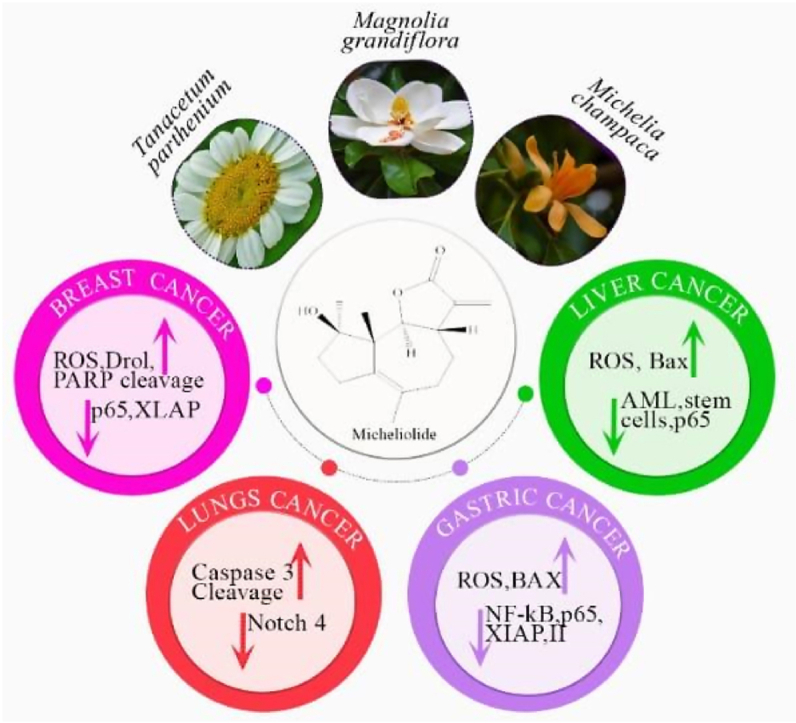

Graphical abstract

Graphical abstract depicting the biological resources, chemical structure, and mechanism of action of Micheliolide.

1. Introduction

Nature has always endeavored mankind with the extensive and infinite treasure of molecular entities, which can be utilized enormously to develop newer drug candidates, pharmacophores, and chemical scaffolds to develop novel drugs for treating many diseases with different origins [1,2]. The chemical entities extracted from natural resources can be termed “Natural Products” (NPs) and are referred to as the end products of gene expression, i.e., secondary metabolites from natural sources [3,4]. NPs are the most persistently successful sources of drug innovation and have been the backbone of conventional remedies worldwide [2]. They have also been an intrinsic part of culture and history [1,5]. NPs from minerals, microbes, plants, and animals have long been anticipated as remedies against diseases for human beings [4]. NPs from plants have long been valuable sources of medicinal components, and up till now, numerous pharmacological products have plant-based origins [6]. Screenings of therapeutic plants have led to the discovery of potent sources of antioxidants [7], anti-cancer [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12]], anti-inflammatory [13], and neuroprotective mediators [14]. A vast family of plant-based compounds, “Sesquiterpene Lactones (SLs),” shows significant pharmacological properties, including the eradication of cancer as well as controlling inflammation [15,16]. Guaianolides is a subdivision of SLs with a tricyclic 5,7,5-ring system [17].

MCL is a potentially stable sesquiterpene lactone [18], which can be isolated from Magnolia grandiflora L., Michelia champaca L., and Michelia compressa (Maxim.) Sarg. MCL and its Michael adduct dimethylaminomicheliolide (DMAMCL) display significant cytotoxicity against tumors [[18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]]. MCL is known to be firstly isolated by Ogura, Cordell [25] from Michelia compressa (Maxim.) Sarg. as a cytotoxic active component. MCL is also a main biologically active constituent of Michelia champaca L. [23,[26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]], Magnolia grandiflora L. [20], Tanacetum parthenium Sch. Bip. [34], Anthemis scrobicularis Yavin [35], and Michelia compressa (Maxim.) Sarg [8,23,[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]]. as shown in Fig. 1. Magnolia or Michelia is a genus with 90 species belonging to the family Magnoliaceae [20]. Chinese traditional medicines also use an alternative cancer treatment [36,37]. Indigenous people in China use Michelia species to cure certain cancers [27], e.g., Magnolia champaca var. champaca has been utilized to cure leukemia and Aldama hypoleuca (S.F.Blake) E.E.Schill. & Panero is used for the treatment of carcinomatous sores.

Fig. 1.

Natural sources of Micheliolide.

Moreover, Michelia champaca L. has been used for curing abdominal lumps in India [38]. Magnolia kobus DC., Michelia compressa (Maxim.) Sarg and Magnolia grandiflora L have shown anticancer activity against several tumor systems in several scientific studies [39]. Table 1 shows some common sources of MCL along with their pharmacological efficacy in the case of different diseases. The plant-derived sesquiterpene lactone MCL was recently found to possess promising antileukemic activity, including the ability to target and kill leukemia stem cells.

Table 1.

Biological sources of Micheliolide and their efficacy in case of several diseases.

| Botanical name | English name | Parts used | Extraction solvent | Disease/Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnolia grandifloraL | Southern Magnolia or bull bay | Leaves | Acetone | Used to treat headache, hypertension, fever, diarrhea, and rheumatism. Anticancer |

[20] |

| Michelia compressa (Maxim.) Sarg. | Root bark | Chloroform fraction of methanol extract | Anticancer, antineoplastic | [8,23,[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]] | |

| Michelia Champaca L. | Golden Champa | Root wood, Stem bark | Ethanol, | Anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antifungal, antipyretic, antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-thrombotic, Hepatoprotective, anti-hyperglycemic, anti-fertility, dysmenorrhea, fever, ulcers, wounds, and skin diseases | [23,[26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]] |

| Anthemis cretica subsp. cretica L. | – | Aerial parts | Methanol | Antifungal, schistosomicidal, antioxidant, antiplasmodial, antitumor, anthelminthic, cytotoxic, analgesic activities, phytotoxic | [35] |

| Tanacetum parthenium Sch.Bip. | Feverfew | – | – | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal | [34] |

Nature-derived biologically active guaniolide sesquiterpene lactone, MCL, has exhibited numerous therapeutic properties such as anticancer, antioxidant, allosteric activation, anti-inflammatory, immune-modulatory, anticancer, antifertility activities, and rheumatoid arthritis. (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Biological activities of the Micheliolide.

Until now, no one has summed up MCL's anticancer and antiinflammatory activities in the form of a review article. Thus, this review aims to summarize MCL's anticancer and antiinflammatory activities.

2. Anti-inflammatory activity of MCL

Inflammation is a complicated system arising in retort to tissue injury or damage caused by some infection. This process is associated with the onset of different pathological states like cancer development, cardiovascular ailments, and autoimmune diseases [40,41]. Sepsis is a multifaceted metabolic and physiological reaction to infection followed by multiple organ failure leading to death [42]. Despite the better result of sepsis due to more and timely usage of glucocorticosteroids, antibiotics, and compassionate care, the prevalence of severe sepsis is still on the rise [43,44]. Primary sepsis-causing microorganisms are gram-negative (G-) bacteria. The main part of G-bacteria's cell wall, lipopolysaccharide, is a ligand of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4); and provokes an unrestrained inflammatory response, even leading to death [45]. Currently, there is no clinically available auspicious therapeutic substance [46]. Although lipopolyamines [47] and synthetic anti-lipopolysaccharide peptides (SALPs) [48,49] exhibit tremendous neutralizing character against LPS, there is also an urgent need for immunomodulatory substances to resist the devastating inflammatory response in septic patients. Harmful side effects associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) provoke an urge to discover harmless substitutes [50]. MCL has been described to show anti-inflammatory activity and reduces LPS-stimulated synthesis of interferon β (IFN-β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), Interleukin 6 (IL-6), Interleukin 10 (IL-10), and IFN-β in dendritic cells, Monocyte/macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7), human monocytic cell, human CD14+ monocytes THP-1 (leukemia cell line) and primary peritoneal macrophages [51].

MCL has been found to mitigate PI3K/Akt/p70S6K and Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) stimulation, specially obstructing the addition of phosphate to p70S6K (Thr389), Akt (Ser473), and IκBα (Ser32/36) [26]. These results give a different insight into regulating LPS-induced inflammatory reactions indicating an auspicious anti-septic character of MCL in the severe peritonitis mouse model. Hence, to cure lethal LPS-induced septic shock, MCL is a promising drug aspirant to develop potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive substances.

MCL mitigated inflammatory responses and accumulation of lipids in LM (lipid molecule)-influenced L02 and AML12 cells via up-regulating Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) and reducing p–NF–κB/p65 and Anti-phosphorylated-IκBα (p-IкBα), thus decreasing lipotoxicity by obstructing the NF-κB pathway. MCL improves hepatic steatosis via upregulation of PPAR-γ expression, thus deterring NF-κB-induced inflammation and triggering AMPK/mTOR-reliant autophagy [52]. MCL distinctly promotes HO-1 (heme oxygenase-1, an antioxidant protein) expression via enhancement of Nrf2 (NF-E2- related factor 2) activity which implies that MCL may work as a neuroprotective substance in neurodegenerative disorders related to neuroinflammation [33]. MCL has been ascribed to deter DSS (dextran sodium sulphate)-mediated rheumatic arthritis [53], inflammatory enteric ailment, and colitis-associated tumors [54]. Still, the role of MCL in sepsis and microbial infection is uncertain. More efforts are required to screen the accurate molecular targets of MCL.

3. Anti-cancer activities of MCL

Cancer is a complicated condition that arises due to the combination of metabolic, signaling, genetic, and epigenetic anomalies that severely disturb cell growth's normal controls and programmed cell death [55]. The etiological process of cancer cell proliferation is assisted by specific chemical reaction pathways or sequences [56,57]. Compounds obtained from natural sources could effectively kill cancerous cells and act as therapeutic agents [58]. Nature is a good source of antitumor drugs extracted from natural sources [59,60]. This might be due to some vital phytochemicals having the capability of inhibiting many pathways and preventing metastasis, in addition to their key roles in the inhibition of cancerous cells [60,61]. Drugs are obtained in trace amounts from natural products; therefore, some other natural products can serve as a precursor for the partial chemical synthesis of the target drug. Chemoprevention of cancer by natural biochemically active agents like minerals, vitamins, and phytochemicals has emerged as a realistic and auspicious realm to reduce the cancer burden. This method is getting attention steadily. These natural compounds are multitargeted, unlike monotargeted pharmaceutical medicines, which regulate cell proliferation and growth [62]. At present, >60% of commercially available anticancer drugs have a natural origin encompassing plants, marine organisms, and microorganisms [63]. Plant secondary metabolites like terpenes, alkaloids, and polyphenols have been acknowledged well for their cytotoxic potential against various cancers [[64], [65], [66]]. Out of 55,000 (approx.) terpenes isolated up till now, only a narrow fraction has cancer eradication potential. Sesquiterpene lactones (SLs) as a prime group of terpenes, have been screened cytotoxic against a diverse array of cancers [67]. Terpenoid sesquiterpene lactones belong to the Asteraceae family which are known to possess multiple biological activities such as anti-bacterial, antimalarial, anti-cancer, antiviral, antioxidant, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory [15,68,69]. The anticancer activity of MCL was reported by different groups. Selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase was identified as an important cellular target of MCL, and MCL may target the redox system in cancer cells. Junmin Zhang et al. reported that targeting thioredoxin reductase by MCL contributes to radiosensitizing and inducing apoptosis of HeLa cells [70]. Zhongren Xu et al., investigated that MCL elicits ROS-mediated ERS-driven immunogenic cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma [71]. Jianshuang Guo et al., showed A rational foundation for MCL-based combination strategy by targeting redox and metabolic circuits in cancer cells [72]. ACT001, a fumarate salt form of MCL, also known as dimethylaminomicheliolide, i.e., DMAMCL converts to MCL consistently under physiological conditions. Li Q et al. investigated the role of ACT001 in glioblastoma cell lines, the study concludes that ACT001 directly binds to IKKβ and inhibits its phosphorylation also modulates the NF-κB/MnSOD/ROS axis by targeting IKKβ to inhibit glioblastoma cell growth [73]. Hou Y et al. studied the targeting of glioma stem-like cells with ACT001 through inhibition of AEBP1/PI3K/AKT signaling [74]. DMAMCL sensitized cancer cells to a single fraction of radiotherapy in vitro by inducing apoptosis and DNA double-strand breaks. The combination of DMAMCL-sensitized radiotherapy with anti-PD-L1 ICB significantly enhanced antitumor efficacy by increasing tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and establishing immune memory [18].

3.1. Micheliolide and cell cycle arrest

Natural biologically active mitosis inhibitors or cell cycle controllers are reported to be potential candidates for cancer treatments [75,76]. As cancerous cells are characterized by prompt and unrestrained cell division [77], these naturally derived compounds are auspiciously capable of deterring the activity of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases, together with several protein factors and enzymes, regulating the cell cycle, helping cells to attain a controlled state [78].

MCL has been recognized in human lung cancer cells to arrest the cell cycle at S and G1/G0 phases. In humans, Mouse Tumor-Associated Fibroblasts (H460) cells MCL causes arrest at the S + G1/G0 checkpoint, downregulating the Protein coding gene (Notch4) and upregulating cleaved caspase3 expression [79].

An adduct of MCL, DMAMCL, has been reported to arrest the cell cycle in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) cell lines at G2/M and SubG1 phase respectively. DMAMCL increased the number of HCC cells at the G2/M stage. Downregulation of cyclin B1 and cyclin D and tumor metastasis proteins MMP-9 and MMP-2 suggest that DMAMCL arrests the cell cycle at the G2/M stage, inhibiting the cell invasion and migration in HCC (LO2, Hepatoblastoma cell line (HepG2), Human hepatoma cell line (SMMC-7721), Human hepatoma cell line (Hep3B), Human hepatoma cell line (Huh7) cells [80].

3.2. Micheliolide and apoptosis

Apoptosis or programmed cell death ensues through specific pathways; mitochondrial or intrinsic pathway and death receptor or extrinsic pathway [81]. Pioneering caspases get prompted by these pathways and activate effector caspases, essential executioners of planned cell death [82]. Cumulative indications by scientific researchers suggest that nature-derived compounds can induce apoptosis while leading cancer cells to death by tempering different cellular factors in intrinsic or extrinsic apoptotic pathways [11,12].

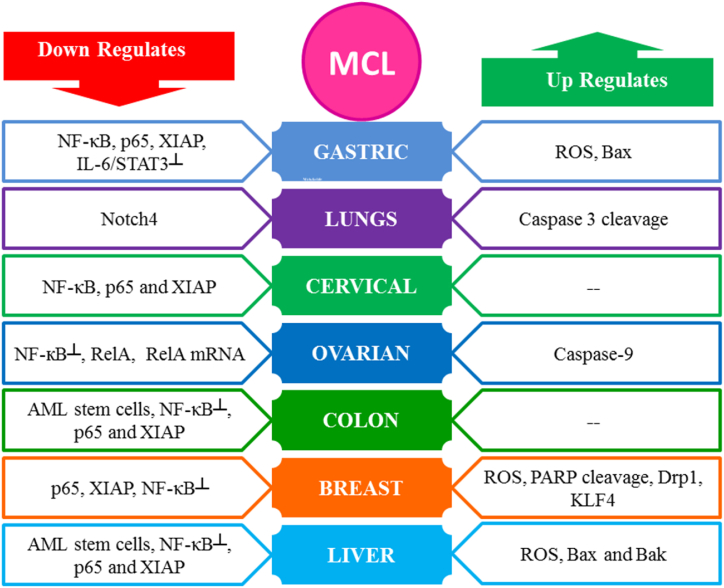

MCL has emerged as a novel paradigm due to its multi-targeted chemotherapeutic properties. Anti-cancer property of MCL has been stated to be associated with the inhibition of cell proliferation and apoptosis stimulation by oxidative stress/ROS accumulation [21,24,80,[83], [84], [85]], caspase family activation [21,24,79,80,83], down-regulation of anti-apoptotic proteins: Mcl-1 [86], and Bcl-2 [19,80], activation of pro-apoptotic proteins: Bax [19,21,30,80] and Bak [80], the downregulating expression level of Notch4 [79], inhibiting IL-6/STAT3 [86] and NF-κB pathway [20,23], downregulating PI3K/Akt/mTOR, JNK, Transcription factor (p65) and XIAP [20,21,80], inhibiting F-actin organization, enhancing PARP cleavage [83,84], activating PKM2 [85] and causing overexpression of Drp1 [84]. Table 2 shows the mechanism of action behind the cytotoxic activity of MCL, while the summary of the molecular targets is shown in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Cytotoxic effects attributed to Micheliolide in the case of certain cell lines and their molecular action mechanism.

| Cancer | Cell Lines | Treatment Conditions |

EC50/IC50 | Molecular Targets | Cell Cycle Arrest | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of Cells/Well | Time (hours) | ||||||

| Lung | H460 | ____ | 48,72,96 | 30,60,90 (μmol/L) | Expression level of notch4 ↓, cleaved caspase3↑ | G2/M, S phase and G1/G0 | [79] |

| Liver | Hep G2, QGY-7703, Bel-7404, Hep3B, Huh7 and PLC/PRF/5 | 5 × 106 | 24, 72 | (30, 60) μM | ROS↑, F-actin organization┴, cleaved caspase-3↑, cleaved PARP↑ | – | [83] |

| Hep G2 | 104 | 24, 48 | 9.61 (μg/ml) | NF-κB ┴, p65 and XIAP↓ | ____ | [20,35] | |

| Colon | HCT 116 | 104 | 24, 48 | 8.34 (μg/ml) | ____ | ____ | [35] |

| 1 × 105 cells/mL | 12, 48 | 12.68 μM | NF-κB┴, p65 and XIAP↓ | ____ | [20] | ||

| Breast | MDA-MB-468 | 1 × 105 cells/mL | 12, 48 | 6.61 μM | NF-κB┴, p65 and XIAP↓ | ____ | [20] |

| MDA-MB-231 | 10.79 μM | ____ | |||||

| MDA-MB-231, MCF-7 | 3 × 105 | 24, 48 | 10 μM | Drp1↑, mitochondrial fission↑, ROS↑, PARP cleavage↑, | _____ | [84] | |

| MCF-7 | 104 | 24, 48 | 18.25 (μg/ml) | ____ | ____ | [35] | |

| Ovarian | HeyA8, | ___ | 72 | (9.8 ± 2.2) μmol/L | NF-кB┴, caspase-9↑, RelA↓, RelA mRNA ↓, | ____ | [87] |

| SKOV3 | (12.0 ± 2.1) μmol/L | ||||||

| A2780/DDP | (12.8 ± 1.8) μmol/L | ||||||

| Gastric | N87 | 5 × 104 | 48 | 20 μM | IL-6/STAT3 ┴, IL-6↓, Bax ↑, XIAP↓, p-STAT3↓, cyclinD1↓, Mcl-1↓, MMP2↓, Ki67↓ and PCNA expression↓ | _____ | [86] |

| AGS | |||||||

| 1 × 105 cells/mL | 12, 48 | 11.75 μM | p65↓, XIAP↓, NF-κB pathway, and transcriptional activity┴ | _____ | [20] | ||

| Cervical | Hela | 1 × 105 cells/mL | 12, 48 | 10.24 μM | p65↓, XIAP↓, NF-κB pathway, and transcriptional activity┴ | _____ | [20] |

| AML | HL-60 | _____ | _____ | 5.5 ± 1.4 μM | _____ | _____ | [18] |

| HL-60/A | 6.2 ± 2.2 μM | ||||||

| Glioblastoma | U118MG | 4 × 103 | 24,48, 72 | 4.2 μM | ROS↑, Akt/mTOR┴, PKM2Act | ____ | [85] |

| U251MG | 14.5 μM | ||||||

| SF126 | 11.1 μM | ||||||

Fig. 3.

Diagrammatic illustration of anticancer activity of Micheliolide via interactions with multiple signaling pathways.

3.3. Micheliolide and PI3K/Akt/NF-κB pathways

NF-κB is a family of transcription factors controlling the expression of several genes responsible for angiogenesis, survival, proliferation, immune responses, development, invasion, and metastasis. It is generally endorsed as the most common signaling regulator for the instigation and progress of cancer, supporting tumor cell growth through the expression of several growth regulator genes like Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), cyclin D1, D2, D3, and cyclin E. Therefore, modulation of the NF-κB pathway can be a novel paradigm for fighting cancer [88]. Phytochemicals can modulate the transcription factor NF-κB, hence, stimulating apoptosis [89]. A recent study showed that MCL can form a stable covalent bond with the cysteine residues of STAT3 and STAT5 to suppress their activation, thus inhibiting JAK/STAT signaling. MCL can weaken the NFκB pathway activity and inflammatory responses and increase cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) to induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [90]. Zeng et al. synthesized derivatives of parthenolide and MCL and evaluated these compounds for in vivo anticancer activity in mice. The MCL derivative 9-oxomicheliolide showed promising anticancer activity. The mechanism studies revealed that 9-oxomicheliolide exhibited an inhibition effect against NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways, as well as induction effects of cell apoptosis [91]. Juan Yang et al., investigated the antitumor effect of the novel agent MCL/ACT001 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), inducing cell apoptosis, cell migration, and ROS accumulation in vitro. Overall, their mechanistic investigations revealed that MCL exerted its antitumor activity via regulation of the EGFR-Akt-Bim signaling pathway, thus inducing Bim expression both in vitro and in vivo [93].

MCL inhibits NF-κB expression in leukemic cells. The two-fold elevated level of NF-κB was observed in primary acute myeloid leukemia (AML) mononuclear cells (MNCs) compared to normal MNCs collected from umbilical cord blood. Selectively induced NF-κB in leukemia stem cells (LSCs) was significantly intimidated after MCL treatment. Hence, NF-κB suppression is necessary for MCL-induced apoptotic death [23].

MCL downregulated the activity of NF-κB subunit p65, raised the p-PTEN level, and simultaneously mitigated the caspase-3, cardiac PI3K, phosphorylated Bad, and phosphorylated Akt intensities. Furthermore, the gene expressions of IL-1β (interleukin 1 beta), TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-alpha), and tissue levels of MDA (malondialdehyde) were also downregulated after MCL treatment [94].

4. Other biological activities of MCL

Yaqin et al., presented their work that MCL competitively inhibited the binding of Interleukin-11 (IL-11) with Interleukin-11 Receptor-Alpha (IL-11Rα1), suppressing the activation of STAT3 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2-metatherian pathways, ultimately inhibiting renal tubular EMT and interstitial fibrosis induced by IL-11 [92]. Ziyang Gan et al., showed that MCL treatment may inhibit excessive osteoclast bone resorption without affecting bone formation in estrogen deficiency mice, and additionally, MCL could inhibit osteoclast formation via inhibiting P38 MAPK signaling pathway, and P79350 (a P38 agonist) could rescue this effect [95]. Shuting Li et al., reported that MCL impeded Brahma-related gene 1 (BRG1) from recognizing and attaching to histone H3 lysine 14 acetylation by binding to the asparagine (N1540) of BRG1, thus restraining fibrotic responses and TGF-β1-Smad2/3 signaling pathway. Their study showed that MCL targeting the N1540 residue of BRG1 may be a novel therapeutic strategy to combat PD-related peritoneal fibrosis [96]. Luo X. et al., reported that MCL attenuates atherosclerosis by suppressing macrophage ferroptosis via targeting KEAP1/NRF2 interaction [97]. Yang et al., reported that MCL attenuates neuroinflammation to improve cognitive impairment of Alzheimer's disease by inhibiting NF-κB and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways [98]. Luo et al. studied ACT001 which is a prodrug of MCL and may ameliorate ionizing radiation-induced lung injury by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway [99]. A study reported the MCL treatment significantly ameliorated radiation-induced intestinal tissue damage, inflammatory cell infiltration, and proinflammatory cytokine release. Furthermore, MCL-mediated induction of autophagy can ameliorate radiation-induced enteropathy [100]. Ackun-Farmmer et al. synthesized MCL analogs in bone-targeted polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) to improve bone marrow delivery. Following the treatment with MCL-based NPs therapies, a 13% improvement in median survival was seen with a 34-fold decrease in bone marrow leukemic stem cells as compared to controls [101]. A study published in 2020 by Alwaseem et al., provides insights into the biomolecular targets and mode of action of MCL in leukemia cells. This work highlights the usefulness of the current P450-mediated C–H functionalization approach for speeding up late-stage diversification and clarifying the biomolecular targets of MCL [102].

5. Conclusion

This review article aims to signify the pharmacological properties of this biologically active constituent from the plant family Magnoliaceae. This compound's most eminent medicinal properties are due to its anti-inflammatory and anticancer potential. Several scientific investigations suggest it modulates signaling cascades like PI3K/Akt and NF-κB. It is also an effective apoptosis inducer and arrests the cell cycle at G1/G0, S, and G2/M phases. The research area in cell cycle arrest also lacks evidence about cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Moreover, exact action mechanisms should also be investigated by various techniques as well as experimental studies. The efficacy of Micheal's adducts of MCL and DMAML, suggests that its pharmacological potential may be enhanced by making its various derivatives and investigating their potential against many diseases especially cancer, the second deadliest malignancy worldwide. According to our suggestions, toxicological profiling of MCL is also needed to potentiate it as a novel anticancer and anti-inflammatory agent in clinical trials.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Jalal Uddin: Supervision, Funding acquisition. Mehwish Fatima: Writing – original draft. Ammara Riaz: Supervision, Conceptualization. Ghulam Mustafa Kamal: Writing – review & editing. Abdullatif Bin Muhsinah: Funding acquisition. Abdul Razzaq Ahmed: Funding acquisition. Ramsha Iftikhar: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through a large group Research Project under grant number RGP.1/169/44.

Contributor Information

Jalal Uddin, Email: jalaluddinamin@gmail.com.

Ghulam Mustafa Kamal, Email: mustafa.kamal@kfueit.edu.pk.

List of Abbreviations

- PI3K/Akt pathway

Phosphoinositide-3-kinase–protein kinase B/Akt

- NF-κB pathway

Nuclear factor kappa B

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

- NSAIDs

Non-steroidal type anti-inflammatory drugs

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- IL-10

Interleukin 10

- IFN-β

Interferon β

- RAW 264.7

Monocyte/macrophage cell line

- CD14+

Cluster of differentiation 14

- THP-1

Human leukemia monocytic cell line

- AML12

Alpha mouse liver 12

- PPAR-γ

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- p-IкBα

Anti-phosphorylated-IκBα

- AMPK/mTOR

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase/Mammalian target of rapamycin

- HO-1

Heme oxygenase-1

- Nrf2

NF-E2- related factor 2

- H460

Mouse Tumor-Associated Fibroblasts

- HepG2

Hepatoblastoma cell line

- SMMC-7721

Human hepatoma cell line

- Hep3B

Human hepatoma cell line

- Huh7

Human hepatoma cell line

- Bax

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- Bak

Proapoptotic effector Bcl-2 proteins

- Notch4

Protein Coding gene

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinases

- p65

Transcription factor

- XIAP

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

- PARP

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases

- PKM2

Pyruvate kinase M2

- PTEN

Phosphatase and tensin homologue

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- Wnt

Wingless and Int-1 (secreted factors that regulate cell growth, motility, and differentiation during embryonic development

- TGFβ

Transforming growth factor-β

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

References

- 1.Veeresham C. Wolters Kluwer--Medknow Publications; 2012. Natural Products Derived from Plants as a Source of Drugs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey A.L. Natural products in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today. 2008;13(19–20):894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasul A., et al. Pinocembrin: a novel natural compound with versatile pharmacological and biological activities. BioMed Res. Int. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/379850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shinde P., Banerjee P., Mandhare A. Marine natural products as source of new drugs: a patent review (2015–2018) Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2019;29(4):283–309. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2019.1598972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhai J.-D., et al. Biomimetic semisynthesis of arglabin from parthenolide. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77(16):7103–7107. doi: 10.1021/jo300888s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atanasov A.G., et al. Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: a review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015;33(8):1582–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmad R., Ahmad M., Jahan N. Phytochemical screening and anti-oxidant activity of the two plants Ziziphus oxyphylla Edgew and Cedrela serrata Royle. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014;27(5) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang C., et al. Altholactone inhibits NF-κB and STAT3 activation and induces reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis in prostate cancer DU145 cells. Molecules. 2017;22(2):240. doi: 10.3390/molecules22020240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan M., et al. Alantolactone induces apoptosis in glioblastoma cells via GSH depletion, ROS generation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. IUBMB Life. 2012;64(9):783–794. doi: 10.1002/iub.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan M., et al. Pseudolaric Acid B induces caspase-dependent and caspase-independent apoptosis in u87 glioblastoma cells. Evid. base Compl. Alternative Med. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/957568. Article ID 957568, 11 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasul A., et al. Magnolol, a natural compound, induces apoptosis of SGC-7901 human gastric adenocarcinoma cells via the mitochondrial and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Int. J. Oncol. 2012;40(4):1153–1161. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasul A., et al. Xanthoxyletin, a coumarin induces S phase arrest and apoptosis in human gastric adenocarcinoma SGC-7901 cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP. 2011;12(5):1219–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Younis T., et al. Fraxinus xanthoxyloides leaves reduced the level of inflammatory mediators during in vitro and in vivo studies. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2016;16(1):230. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1189-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aggarwal B.B., Harikumar K.B. Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009;41(1):40–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghantous A., et al. What made sesquiterpene lactones reach cancer clinical trials? Drug Discov. Today. 2010;15(15–16):668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheikh I.A., et al. Lessons learned from the discovery and development of the sesquiterpene lactones in cancer therapy and prevention. Expet Opin. Drug Discov. 2022;17(12):1377–1405. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2023.2147920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schall A., Reiser O. Synthesis of biologically active Guaianolides with a trans‐annulated lactone moiety. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2008;2008(14):2353–2364. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y., et al. Dimethylaminomicheliolide sensitizes cancer cells to radiotherapy for synergistic combination with immune checkpoint blockade. Adv. Ther. 2022;5(1) doi: 10.1002/adtp.202100160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.An Y., et al. Micheliolide derivative DMAMCL inhibits glioma cell growth in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2015;10(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding, et al. Cytotoxic sesquiterpenoids from the leaves of Magnolia grandiflora. Phytochemistry. 2018;155:182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y., et al. ROS generation and autophagosome accumulation contribute to the DMAMCL-induced inhibition of glioma cell proliferation by regulating the ROS/MAPK signaling pathway and suppressing the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. OncoTargets Ther. 2019;12:1867. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S195329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin X.H., et al. ACT001 can prevent and reverse tamoxifen resistance in human breast cancer cell lines by inhibiting NF‐κB activation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019;120(2):1386–1397. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji Q., et al. Antineoplastic effects and mechanisms of micheliolide in acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7(40) doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu N., et al. The anti-tumor growth effect of a novel agent DMAMCL in rhabdomyosarcoma in vitro and in vivo. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1107-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogura M., Cordell G.A., Farnsworth N.R. Anticancer sesquiterpene lactones of Michelia compressa (Magnoliaceae) Phytochemistry. 1978;17(5):957–961. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin X., et al. Micheliolide inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory response and protects mice from LPS challenge. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep23240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng F., et al. Micheliolide ameliorates renal fibrosis by suppressing the Mtdh/BMP/MAPK pathway. Lab. Invest. 2019;99(8):1092–1106. doi: 10.1038/s41374-019-0245-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma W.-W., et al. Synthesis of micheliolide derivatives and their activities against AML progenitor cells. Molecules. 2013;18(5):5980–5992. doi: 10.3390/molecules18055980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alves J.C., Fantini E.C. Chemical transformations of eremanthine: synthesis of micheliolide and 1 (R), 10 (R)-dihydromicheliolide. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2005;16(4):749–755. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang X., et al. Micheliolide inhibits gastric cancer growth in vitro and in vivo via blockade of the IL-6/STAT3 pathway. Die Pharmazie-An Int. Res. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2019;74(3):175–178. doi: 10.1691/ph.2019.8816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding, et al. The application of Heck reaction in the synthesis of guaianolide sesquiterpene lactones derivatives selectively inhibiting resistant acute leukemic cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23(22):6087–6092. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Гришаева Л. Проблемы лингвистической прогностики. 2004. Прогнозирование дискурсивной деятельности коммуникантов и языковая личность; pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun Z., et al. Micheliolide suppresses LPS-induced neuroinflammatory responses. PLoS One. 2017;12(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao Y., et al. Sesquiterpene lactones inhibit advanced oxidation protein product-induced MCP-1 expression in podocytes via an IKK/NF-κB-dependent mechanism. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/934058. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaghloul A.M., et al. New cytotoxic sesquiterpene lactones from Anthemis scrobicularis. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2014;16(9):922–929. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2014.931377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao Z., et al. Indirubin and meisoindigo in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia in China. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2002;43(9):1763–1768. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000006295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao Z., et al. Meisoindigo for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2000;111(2):711–712. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartwell J.L. Plants used against cancer. A survey.[Continued.] Lloydia. 1970;33:97–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farnsworth N.R., et al. Potential value of plants as sources of new antifertility agents II. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 1975;64(5):717–754. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600640504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu Y., et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying chronic inflammation-associated cancers. Cancer Lett. 2014;345(2):164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chillar A., et al. A profile of NSAID-targeted arachidonic acid metabolisms in human embryonic stem cells (hESCs): implication of the negative effects of NSAIDs on heart tissue regeneration. Int. J. Cardiol. 2011;150(3):253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angus D.C., Van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:840–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaieski D.F., et al. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit. Care Med. 2013;41(5):1167–1174. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen J., Opal S., Calandra T. Sepsis studies need new direction. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012;12(7):503–505. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Savva A., Roger T. Targeting toll-like receptors: promising therapeutic strategies for the management of sepsis-associated pathology and infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 2013;4:387. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fink M.P., Warren H.S. Strategies to improve drug development for sepsis. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13(10):741–758. doi: 10.1038/nrd4368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sil D., et al. Biophysical mechanisms of the neutralization of endotoxins by lipopolyamines. Open Biochem. J. 2013;7:82. doi: 10.2174/1874091X01307010082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gutsmann T., et al. New antiseptic peptides to protect against endotoxin-mediated shock. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54(9):3817–3824. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00534-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heinbockel L., et al. Preclinical investigations reveal the broad-spectrum neutralizing activity of peptide Pep19-2.5 on bacterial pathogenicity factors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57(3):1480–1487. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02066-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sostres C., et al. Adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, aspirin and coxibs) on upper gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010;24(2):121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qin X., et al. Micheliolide inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory response and protects mice from LPS challenge. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep23240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhong J., et al. Micheliolide alleviates hepatic steatosis in db/db mice by inhibiting inflammation and promoting autophagy via PPAR-γ-mediated NF-кB and AMPK/mTOR signaling. Int. Immunopharm. 2018;59:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu H., et al. Therapeutic effects of micheliolide on a murine model of rheumatoid arthritis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015;11(1):489–493. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viennois E., et al. Micheliolide, a new sesquiterpene lactone that inhibits intestinal inflammation and colitis-associated cancer. Lab. Invest. 2014;94(9):950–965. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khan M., et al. Killing cancer with platycodin D through multiple mechanisms. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2016;20(3):389–402. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pike M.C., et al. Estrogens, progestogens, normal breast cell proliferation, and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol. Rev. 1993;15(1):17. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamane K., et al. PLU-1 is an H3K4 demethylase involved in transcriptional repression and breast cancer cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. 2007;25(6):801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shoeb M. Anti-cancer agents from medicinal plants. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2006;1(2):35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Newman D.J., Cragg G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75(3):311–335. doi: 10.1021/np200906s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Somasundaram S., et al. Dietary curcumin inhibits chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in models of human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62(13):3868–3875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sharifi-Rad J., et al. Natural products and synthetic analogs as a source of antitumor drugs. Biomolecules. 2019;9(11):679. doi: 10.3390/biom9110679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khan M., et al. Targeting apoptosis and multiple signaling pathways with icariside II in cancer cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2015;11(9):1100. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.11595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dall'Acqua S. Natural products as antimitotic agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2014;14(20):2272–2285. doi: 10.2174/1568026614666141130095311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spatafora C., Tringali C. Natural-derived polyphenols as potential anticancer agents. Anti Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2012;12(8):902–918. doi: 10.2174/187152012802649996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rawat D.S., Singh R. Plant derived secondary metabolites as anti-cancer agents. Anti Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2013;13(10):1551. doi: 10.2174/187152061310131206154445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li Y.-X., Himaya S., Kim S.-K. Triterpenoids of marine origin as anti-cancer agents. Molecules. 2013;18(7):7886–7909. doi: 10.3390/molecules18077886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu T., Ma R., Yu L. Structure-activity relationship of tubeimosides in anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and antitumor-promoting effects. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2001;22(5):463–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoffmann H., Rabe J. Synthesis and biological activity of α‐methylene‐γ‐butyrolactones. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1985;24(2):94–110. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Picman A.K. Biological activities of sesquiterpene lactones. Biochem. Systemat. Ecol. 1986;14(3):255–281. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang J., Chen Y., Fang J. Targeting thioredoxin reductase by micheliolide contributes to radiosensitizing and inducing apoptosis of HeLa cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022;186:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu Z., et al. Mecheliolide elicits ROS-mediated ERS driven immunogenic cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma. Redox Biol. 2022;54 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo J., et al. A rational foundation for micheliolide-based combination strategy by targeting redox and metabolic circuit in cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022;200 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li Q., et al. ACT001 modulates the NF-κB/MnSOD/ROS axis by targeting IKKβ to inhibit glioblastoma cell growth. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 2020;98(2):263–277. doi: 10.1007/s00109-019-01839-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hou Y., et al. Targeting of glioma stem-like cells with a parthenolide derivative ACT001 through inhibition of AEBP1/PI3K/AKT signaling. Theranostics. 2021;11(2):555–566. doi: 10.7150/thno.49250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nagle A., Hur W., Gray N.S. Antimitotic agents of natural origin. Curr. Drug Targets. 2006;7(3):305–326. doi: 10.2174/138945006776054933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ranjan A., et al. Modulation of signal transduction pathways by natural compounds in cancer. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2015;13(10):730–742. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(15)30073-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Asghar U., et al. The history and future of targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14(2):130–146. doi: 10.1038/nrd4504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bailon-Moscoso N., et al. Natural compounds as modulators of cell cycle arrest: application for anticancer chemotherapies. Curr. Genom. 2017;18(2):106–131. doi: 10.2174/1389202917666160808125645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meng W., Yao K. The anti-tumor effect and underlying mechanism of micheliolide on H460 lung cancer by notch4 signal pathway. Journal of Medical Postgraduates. 2017;30(9):932–936. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yao S., et al. Cancer Letters; 2020. DMAMCL Exerts Antitumor Effects on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Both in Vitro and in Vivo. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matthews G.M., Newbold A., Johnstone R.W. Intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathway signaling as determinants of histone deacetylase inhibitor antitumor activity. Adv. Cancer Res. 2012;116:165–197. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394387-3.00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zaman S., Wang R., Gandhi V. Targeting the apoptosis pathway in hematologic malignancies. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2014;55(9):1980–1992. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.855307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yu L., et al. Micheliolide inhibits liver cancer cell growth via inducing apoptosis and perturbing actin cytoskeleton. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019;11:9203–9212. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S216870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jia Y., et al. Dynamin-related protein 1 is involved in micheliolide-induced breast cancer cell death. OncoTargets Ther. 2015;8:3371–3381. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S91805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guo J., et al. Dimethylaminomicheliolide (DMAMCL) suppresses the proliferation of glioblastoma cells via targeting pyruvate kinase 2 (PKM2) and rewiring aerobic glycolysis. Front. Oncol. 2019;9:993. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tang X., et al. Micheliolide inhibits gastric cancer growth in vitro and in vivo via blockade of the IL-6/STAT3 pathway. Pharmazie. 2019;74(3):175–178. doi: 10.1691/ph.2019.8816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Qi Z., et al. [Study of effects of micheliolide on ovarian cancer cell lines and its mechanism] Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2016;51(9):688–692. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-567X.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vazquez-Santillan K., et al. NF-kappaB signaling in cancer stem cells: a promising therapeutic target? Cell. Oncol. 2015;38(5):327–339. doi: 10.1007/s13402-015-0236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lou C., et al. Identification of Hirsutine as an anti-metastatic phytochemical by targeting NF-kappaB activation. Int. J. Oncol. 2014;45(5):2085–2091. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huang H., et al. Micheliolide exerts effects in myeloproliferative neoplasms through inhibiting STAT3/5 phosphorylation via covalent binding to STAT3/5 proteins. Blood Sci. 2023;5(4):258–268. doi: 10.1097/BS9.0000000000000168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zeng B., et al. Design, synthesis and in vivo anticancer activity of novel parthenolide and micheliolide derivatives as NF-κB and STAT3 inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2021;111 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.104973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li Y., et al. Renal fibrosis is alleviated through targeted inhibition of IL-11-induced renal tubular epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Am. J. Pathol. 2023;193(12):1936–1952. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2023.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang J., et al. The antitumor effect of the novel agent MCL/ACT001 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023;149(9):5717–5728. doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-04542-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kalantary-Charvadeh A., et al. Micheliolide protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in mice by regulating PI3K/Akt/NF-kB signaling pathway. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2019;19(4):297–305. doi: 10.1007/s12012-019-09511-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gan Z., et al. Micheliolide prevents estrogen deficiency-induced bone loss via inhibiting osteoclast bone resorption. Aging (Albany NY) 2023;15(19):10732–10745. doi: 10.18632/aging.205111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Li S., et al. Brahma-related gene 1 acts as a profibrotic mediator and targeting it by micheliolide ameliorates peritoneal fibrosis. J. Transl. Med. 2023;21(1):639. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-04469-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Luo X., et al. MCL attenuates atherosclerosis by suppressing macrophage ferroptosis via targeting KEAP1/NRF2 interaction. Redox Biol. 2024;69 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2023.102987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang G., et al. Micheliolide attenuates neuroinflammation to improve cognitive impairment of Alzheimer's disease by inhibiting NF-κB and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Heliyon. 2023;9(7) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Luo H., et al. ACT001 Ameliorates ionizing radiation-induced lung injury by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023;163 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wu Dong-Ming, et al. Autophagy induced by micheliolide alleviates acute irradiation-induced intestinal injury via inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;12 773150 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.773150. 18 Jan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ackun-Farmmer, Marian A., et al. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of micheliolide analogs to eliminate leukemic stem cells in the bone marrow. Advanced therapeutics. 2022;5(1) doi: 10.1002/adtp.202100100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Alwaseem Hanan, et al. Comprehensive structure-activity profiling of micheliolide and its targeted proteome in leukemia cells via probe-guided late-stage C-H functionalization. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021;7(5):841–857. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]