Abstract

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) production in response to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was investigated in normal neonate monocytes. Intracellular or culture supernatant IL-1β protein levels were measured by enzyme immunoassay. The expression of mRNAs for interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1), IL-1β-converting enzyme (ICE), and IL-1β in the cells was analyzed semiquantitatively by reverse transcriptase-PCR. Before RSV exposure, some IRF-1, ICE, and IL-1β transcripts were already expressed in the monocytes. The levels of these transcripts increased significantly 2 h after RSV exposure compared with those in mock-infected cells. At that time, significantly higher intracellular IL-1β protein levels were observed in RSV-exposed cells. After 20 h of RSV exposure, quantities of soluble IL-1β secreted from RSV-exposed cells were moderately higher than those from noninfected cells. These observations suggest that RSV infection of neonatal monocytes triggers enhanced transcription and increased translation of the IL-1β gene and increased secretion of the soluble protein. The later phase of these processes may be promoted by ICE activity, which was upregulated by increased IRF-1. The increase in IRF-1 activity may also result from RSV infection.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in neonates and young infants often causes life-threatening acute bronchiolitis despite the presence of maternally transferred specific neutralizing antibody (4, 23). Immaturity of the immune system and the fragile anatomy of the infant’s bronchioles have been proposed as possible reasons for the severity of RSV disease in young infants (11, 18, 24, 29). However, the pathophysiology of RSV bronchiolitis in infants has not been fully clarified.

Recently, the participation of a wide range of inflammatory or immunoregulatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor alpha in the pathology of RSV lower respiratory tract disease has been suggested in in vivo (13, 21) and in vitro (2, 14, 20, 25) settings. It has been proposed that IL-1β produced in the respiratory tract may act as one of the main inflammatory cytokines during the acute phase of the infection, partly by activating other inflammatory cytokines, but also by activation of inflammatory cells and induction of prostaglandins (1, 19). IL-1β may also promote histamine-induced bronchoconstriction in infants during RSV infection because it is known that injection of IL-1β into mice induces formation of histidine decarboxylase, the enzyme that forms histamine, in various tissues, including lung tissue (5).

In human and mouse monocytes, IL-1β-converting enzyme (ICE) has been reported as the cysteine protease required for final IL-1β processing and secretion (28). Recently, a possible role of ICE in apoptosis has also been proposed (16). Furthermore, interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) upregulates ICE in response to mitogen or gamma interferon (26, 27), and IRF-1 is also known to be activated by viral infection in mouse cells (12). However, the precise kinetics and role of IRF-1 and ICE in IL-1β production in virus-infected human cells have not been investigated. In this study, we investigated the temporal relationship of the expression of IRF-1, the ICE gene, and IL-1β production in RSV-infected neonatal monocytes.

Heparinized (50 μg/ml) cord blood samples obtained from seven healthy neonates were sedimented over Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Mononuclear cells were collected and washed twice with RPMI 1640 medium. The cell concentration was adjusted to 1.5 × 107/ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20% human AB serum. A 300-μl sample was applied to each well of 24-well semimicro plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). The plates were precoated with human AB serum and incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then incubated for 2 h in 5% CO2 in air. The plates were washed twice with RPMI 1640 medium to remove nonadherent cells. Over 95% of adherent cells were positive for nonspecific esterase.

RSV strain Long (the prototype RSV group A strain) grown in HEp-2 cells was used for infection. The stock virus titer was 107 PFU/ml. Uninfected HEp-2 cell culture fluid was processed similarly for use in a mock infection.

Adherent monocytes were washed twice in RPMI 1640 medium and counted. Monocytes were inoculated with stock virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of about 2 for 1 h at 37°C. The same volumes and inoculation times were used for noninfected control cells. Cells were then washed with RPMI medium twice and incubated in 0.7 ml of RPMI 1640 medium with 20% fetal calf serum. Culture medium supernatants were collected 2 and 20 h after infection, centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min, and preserved. To recover the intracellular cytokines at 2 and 20 h after infection, 0.7 ml of distilled water was added to the cells in each well. Ten minutes later, the cell lysates were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min and the supernatants were collected.

To examine the expression of mRNA for IRF-1, ICE, and IL-1β, monocytes were harvested 0 h (preinfection) and 2 h after RSV exposure; monocytes were washed with PBS and treated with 0.8 ml of RNAzol B (Biotecx Laboratories, Houston, Tex.) for RNA extraction.

The IL-1β in the culture supernatants and cell lysates was measured with a quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Quantikine; R and D systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were diluted twice before assay. The detection limit of the test is 7.8 pg/ml (manufacturer’s information).

Total cellular RNA was isolated from monocytes with or without RSV infection by using RNAzol B and tested for IRF-1, ICE, or IL-1β mRNA by specific reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR as described previously (14). As an internal control, the activity of β-actin mRNA was also determined. Fifty nanograms of the total RNA was used for RT-PCR. For cDNA synthesis, 40 μl of an RNA solution (50 ng) and a random hexamer at 150 pmol/3 μl (Takara, Kyoto, Japan) were heated at 70°C for 10 min and cooled rapidly. After addition of 17 μl of 5× first-strand buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, 375 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2), 9 μl of 0.1 mM dithiothreitol (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.), 17 μl of 2.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Takara), and 200 U of Maloney murine leukemia virus RT (GIBCO BRL), the mixture was stored at 37°C for 1 h. Sequences of the PCR primer pairs and specific probes for Southern blot analysis are shown in Table 1 and were described previously (12, 17, 22). PCR primers and specific probes for ICE were chosen from the nucleotide sequence for ICE p10 (28). The PCR mixture contained 50 ng of cDNA, 10 μl of PCR buffer (500 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris, 1% Triton X-100), 8 μl of 2.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosophates (Takara), 6 μl of 25 mM MgCl2, 100 pM 5′ and 3′ primers, and distilled water for a total volume of 100 μl. After denaturing at 94°C for 10 min and cooling to 65°C, the mixture was seeded with 2.5 μl of thermostable Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Twenty-five cycles of amplification for β-actin, 28 for IRF-1, 29 for ICE, and 24 for IL-1β were carried out with a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). Each cycle consisted of warming at 95°C for 35 s, 55°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 2 min. Finally, the preparations were incubated at 72°C for 15 min. Ten-microliter samples of the RT-PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel, and the amplified products were visualized by UV fluorescence after staining with ethidium bromide. The UV fluorescence signals of specific PCR products in agarose gels were quantified by using a FluorImager SI (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). The specificity of each PCR product was confirmed by determining its predicted size on agarose gels and also by Southern blot analysis. The PCR products were transferred to a nylon membrane and probed with digoxigenin 3′-end-labeled internal oligonucleotide probes (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).

TABLE 1.

Sequences of PCR primers and specific probes used in these experiments

| mRNA (size [bp]) | Sequence (5′–3′) | Probe sequence |

|---|---|---|

| β-Actin (202) | 5′-CCTTCCTGGGCATGGAGTCCTG | 5′-AAAGACCTGTACGCCAACA |

| 3′-GGAGCAATGATCTTGATCTTC | ||

| IRF-1 (363) | 5′-AAGCATGCTGCCAAGCATGGCTGG | 5′-AAGGCCAACTTTCGCTGTGCC |

| 3′-ATCAGGCAGAGTGGAGCTGCT | ||

| ICE (221) | 5′-GCTATTAAGAAAGCCCA | 5′-ATAGAGAAGGATTTTATCGC |

| 3′-TCAGTGGTGGGCATCTG | ||

| IL-1β (388) | 5′-AAACAGATGAAGTGCTCCTTCCAGG | 5′-CACCTTCTTTCCCTTCATC |

| 3′-TGGAGAACACCACTTGTTGCTCCA |

As a positive control for mRNA for IL-1β, total RNA from normal adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells which were incubated with concanavalin A at 10 μg/ml for 3 h was used. Adult monocytes exposed to RSV were used as a source of positive controls for IRF-1 and ICE mRNAs.

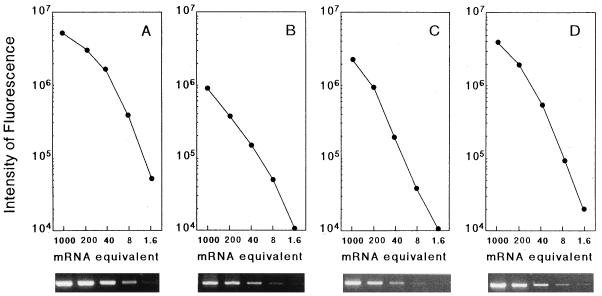

To quantify relative levels of mRNA, a standard curve was obtained by titration (1/5 dilutions) of first strands obtained from 250 ng of RNA from the positive controls described above (Fig. 1). Relative differences in mRNA expression in the test samples were obtained from the standard curves run for the same number of cycles as the unknown samples. The intensity of fluorescence of DNA amplified from first strands obtained from 250 ng of RNA was defined arbitrarily as 1,000 mRNA equivalents.

FIG. 1.

Ethidium bromide-stained gels and standard curves of β-actin (A), IRF-1 (B), ICE (C), and IL-1β (D) mRNAs generated by RT-PCR using control RNA. A 250-ng sample of total RNA was reverse transcribed, and fivefold dilutions of the first strand were amplified by PCR. The intensity of fluorescence of the DNA amplified from the first strand obtained from 250 ng of total RNA was defined arbitrarily as 1,000 mRNA equivalents.

The level of β-actin in each unknown sample was determined from the actin standard curve, and the levels generally varied less than 30% when the first strand was obtained from the same amount of total RNA (data not shown).

Statistical comparison of the mean levels of IL-1β protein or mRNA equivalents between RSV-infected and mock-infected cells was made by using the Student t test.

Twenty-four hours after exposure to RSV, no cytopathic effect was observed and approximately 30% of RSV-exposed monocytes were weakly positive for viral antigen as determined by immunofluorescent-antibody staining with anti-human RSV strain Long rabbit antibodies (DAKOPATTS, Copenhagen, Denmark) (data not shown). No difference in viability was observed between RSV-exposed and noninfected cells at 24 h after treatment (data not shown).

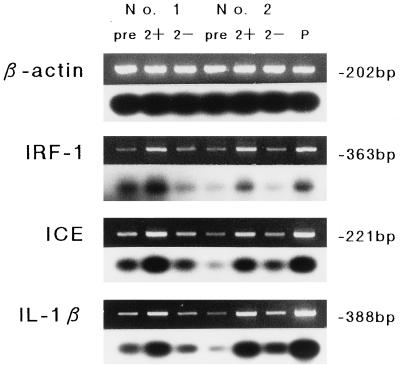

The expression of mRNA for IRF-1, ICE, and IL-1β was determined in monocyte samples at 0 h (preinfection) and 2 h after RSV exposure. Detectable mRNA levels for these three were observed in all adherent monocytes prior to treatment; however, an apparent increase in the expression of these mRNAs was observed in RSV-exposed monocytes compared to noninfected-cell controls 2 h after treatment. Figure 2 shows the ethidium bromide-stained RT-PCR products and Southern blot analysis of two representative cases. The differences of mean mRNA equivalents for these transcripts between the RSV-treated and mock-infected cells were statistically significant (IRF-1, P < 0.01; ICE, P < 0.05; IL-1β, P < 0.01) (Table 2).

FIG. 2.

β-Actin, IRF-1, ICE, and IL-1β mRNA expression determined by RT-PCR (upper) and Southern blot (lower) analyses of two cord blood monocyte samples exposed to RSV. Lane P, positive control. mRNA expression was assessed before treatment (pre) and 2 h after RSV exposure (2+) or mock infection (2−).

TABLE 2.

Semiquantitative analysis of amplified PCR products of seven neonatal monocyte samples exposed to RSV or treated with HEp-2 cell culture fluida

| mRNA | Mean amt of mRNA ± SE

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment | 2 h after:

|

||

| RSV infection | Mock infection | ||

| IRF-1 | 8.2 ± 1.6 | 91.6 ± 11.4b | 23.4 ± 8.2b |

| ICE | 27.8 ± 5.6 | 140.4 ± 43.6c | 46.1 ± 12.6c |

| IL-1β | 28.6 ± 14.2 | 72.6 ± 23.2d | 28.4 ± 16.7d |

Relative quantities of mRNA obtained from a standard curve derived from positive controls are shown. The intensity of fluorescence of DNA amplified from the first strand obtained from 250 ng of total RNA was defined arbitrarily as 1,000 mRNA equivalents. The data are for seven samples. The enhancement of each mRNA level by RSV infection was statistically significant.

P < 0.01 (paired Student t test).

P < 0.05 (paired Student t test).

P < 0.01 (paired Student t test).

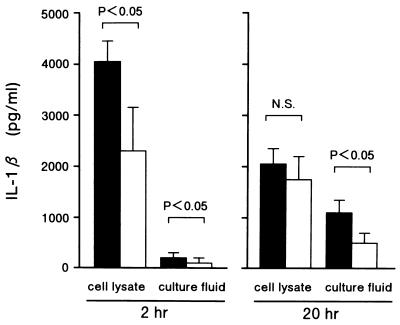

The production of IL-1β was examined 2 and 20 h after treatment in culture fluids and cell lysate (Fig. 3). Two hours after RSV exposure, significantly higher levels of intracellular IL-1β protein were observed in infected than in mock-infected cells (mean, 4,020 ± 426 [standard error] and 2,315 ± 836 pg/ml, respectively [P < 0.05]). On the other hand, after 20 h of RSV exposure, moderately higher quantities of soluble IL-1β protein were detected in cell-free supernatants of RSV-exposed cells than in those of mock-infected cells (1,066 ± 258 and 484 ± 227 pg/ml, respectively).

FIG. 3.

Immunoactive IL-1β protein concentration in RSV-treated (▪) or mock-infected (□) monocyte culture supernatants and cell lysates collected at 2 and 20 h after treatment. Mean results ± the standard errors of seven experiments with different donors are shown. Statistical comparison was made by using Student’s t test. N.S., not significant.

In this study, neonatal monocytes were exposed to RSV, which is the most important viral pathogen in neonates and young infants. Recent in vitro studies of RSV infection of adult macrophages (25), as well as immunofluorescence analysis of alveolar macrophages of infants with RSV infection (15), suggest that RSV-infected macrophages do produce IL-1β protein. Our study also confirms the prompt production of IL-1β in neonatal monocytes exposed to RSV, with regard to both gene transcription and the immunorelevant IL-1β protein. RSV-exposed neonatal monocytes expressed more IL-1β transcripts and produced more intracellular IL-1β protein than did noninfected control cells as early as 2 h after RSV infection, although there is a possibility that the IL-1β detected in cell lysates is a mixture of the unprocessed IL-1β precursor and intracellular IL-1β because it was reported that the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit used in this study detects but considerably underestimates the IL-1β precursor (9). Subsequently, 20 h after infection, significant IL-1β protein secretion from RSV-exposed cells was observed.

Although the induction of transcription of IL-1β gene occurs in cells by adherence, only limited translational activity is initiated in the absence of a second signal such as lipopolysaccharide (6, 8). In our study, monocytes isolated by adherence also expressed some IL-1β transcript. However, it was obvious that RSV exposure acted promptly, within 2 h, which is apparently the eclipse phase of infection, as a second signal to enhance transcription and to accelerate translation to protein synthesis. This observation suggests that the induction of IL-1β in RSV-treated cells does not depend on viral replication itself in the cells and that adsorption and/or penetration of the virus might trigger induction of IL-1β.

Interestingly, monocytes exposed to RSV showed significantly enhanced expression of the IRF-1 and ICE genes the same as the IL-1β gene, at 2 h after exposure. Recently, it has been shown that IRF-1 upregulates ICE gene expression in response to mitogen or gamma interferon (26, 27) and IRF-1 expression itself is activated by viral infection in mouse L929 cells (12). ICE has also been shown to be a prerequisite for final IL-1β processing and secretion (3, 7, 28). Our results include no data on interactions among IRF-1, ICE, and IL-1β; however, it might be suggested that RSV infection of neonatal monocytes initially activates IRF-1 to enhance ICE expression and that IL-1β production by RSV-exposed monocytes is enhanced in its later phase by this increased ICE activity.

This is the first report on the effects of viral infection on transcription of the IRF-1, ICE, and IL-1β genes and on the production of IL-1β protein in human cells. Such enhancement might also occur in monocytes and/or macrophages infected with other respiratory viruses. Thus, ICE and IL-1β may be considered as a target for anti-inflammatory drugs in severe viral lower respiratory tract diseases (28).

ICE and other ICE-related proteases have recently been implicated in apoptosis or programmed cell death (7, 16). IRF-1 has also been considered to be correlated with apoptosis through regulation of the ICE gene (26, 27). Miura et al. observed that overexpression of ICE in a rat fibroblast cell line caused apoptosis (16). However, in our study there were no differences in viability between RSV-exposed and mock-infected cells. This observation suggests that the degree of ICE expression able to induce prompt IL-1β excretion from RSV-exposed cells may not be associated with cell apoptosis (10).

We thank M. Akihara and A. Wakamatsu for providing human cord blood samples.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira S, Hirano T, Taga T, Kishimoto T. Biology of multifunctional cytokines: IL-6 and related molecules (IL-1 and TNF) FASEB J. 1990;4:2860–2867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker S, Quay J, Soukup J. Cytokine (tumor necrosis factor, IL-6, and IL-8) production by respiratory syncytial virus-infected human alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:4307–4312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerretti D P, Kozlosky C J, Mosley B, Nelson N, Ness K V, Greenstreet T A, March C J, Kronheim S R, Druck T, Cannizzaro L A, Huebner K, Black R A. Molecular cloning of the interleukin-1β converting enzyme. Science. 1992;256:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1373520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins P L, McIntosh K, Chanock R M. Respiratory syncytial virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, editors. Field’s virology. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1996. pp. 1313–1351. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Endo Y. Induction of histidine and ornithine decarboxylase activities in mouse tissues by recombinant interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor. Biochem Phamacol. 1989;38:1287–1292. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuhlbrigge R C, Chaplin D D, Kielly J-M, Unanue E R. Regulation of interleukin 1 gene expression by adherence and lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1987;138:3799–3802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gagliardini V, Fernandez P-A, Lee R K K, Drexler H C A, Rotello R J, Fishman M C, Yuan J. Prevention of vertebrate neuronal death by the crmA gene. Science. 1994;263:826–828. doi: 10.1126/science.8303301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haskill S, Johnson C, Eierman D, Becker S, Warren K. Adherence induces selective mRNA expression of monocyte mediators and proto-oncogenes. J Immunol. 1988;140:1690–1694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herzyk D J, Berger A E, Allen J N, Wewers M D. Sandwich ELISA formats designed to detect 17 kDa IL-1β significantly underestimate 35 kDa IL-1β. J Immunol Methods. 1992;148:243–254. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90178-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li P, Allen H, Banerjee S, Franklin S, Herzog L, Johnston C, McDowell J, Paskind M, Rodman L, Salfeld J, Towne E, Tracey D, Wardwell S, Wei F-Y, Wong W, Kamen R, Seshadri T. Mice deficient in IL-1β-converting enzyme are defective in production of mature IL-1β and resistant to endotoxin shock. Cell. 1995;80:401–411. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez F D, Morgan W J, Wright A L, Holberg C J, Taussig L M The Group Health Medical Associates. Diminished lung function as a predisposing factor for wheezing respiratory illness in infants. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1112–1117. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810273191702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maruyama M, Fujita T, Taniguchi T. Sequence of a cDNA coding for human IRF-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:3292. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.8.3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuda K, Tsutsumi H, Okamoto Y, Chiba S. Development of interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha activity in nasopharyngeal secretion of infants and children during infection with respiratory syncytial virus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2:322–324. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.3.322-324.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuda K, Tsutsumi H, Sone S, Yoto Y, Oya K, Okamoto Y, Ogra P L, Chiba S. Characteristics of IL-6 and TNF-α production by respiratory syncytial virus-infected macrophages in the neonate. J Med Virol. 1996;48:199–203. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199602)48:2<199::AID-JMV13>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Midulla F, Villan A, Panuska J R, Dab I, Kolls J K, Merolla R, Ronchetti R. Respiratory syncytial virus lung infection in infants: immunoregulatory role of infected alveolar macrophages. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1515–1519. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miura M, Zhu H, Rotello R, Hartweig E A, Yuan J. Induction of apoptosis in fibroblasts by IL-1β-converting enzyme, a mammalian homolog of the C. elegans cell death gene ced-3. Cell. 1993;75:653–660. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90486-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyamoto M, Fujita T, Kimura Y, Maruyama M, Harada H, Sudo Y, Miyata T, Taniguchi T. Regulated expression of a gene encoding a nuclear factor, IRF-1, that specifically binds to IFN-β gene regulatory elements. Cell. 1988;54:903–913. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy B R, Alling D W, Snyder M H, Walsh E E, Prince G A, Chanock R M, Hemming V G, Rodriguez W J, Kim H W, Graham B S, Wright P F. Effect of age and preexisting antibody on serum antibody response of infants and children to the F and G glycoproteins during respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:894–898. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.5.894-898.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicod L P. Cytokine 1. Overview Thorax. 1993;48:660–667. doi: 10.1136/thx.48.6.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noah T L, Becker S. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced cytokine production by a human bronchial epithelial cell line. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:L472–L478. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.265.5.L472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noah T L, Henderson F W, Wortman I A, Devlin R B, Handy J, Koren H S, Becker S. Nasal cytokine production in viral acute upper respiratory infection of childhood. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:584–592. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto Y, Kudo K, Ishikawa K, Ito E, Togawa K, Saito I, Moro I, Patel J A, Ogra P L. Presence of respiratory syncytial virus genomic sequences in middle ear fluid and its relationship to expression of cytokines and cell adhesion molecules. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1277–1281. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.5.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parrott R H, Kim H W, Arrobio J O, Hodes D S, Murphy B R, Brandt C D, Camargo E, Chanock R M. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus infection in Washington D.C. II. Infection and disease with respect to age, immunologic status, race and sex. Am J Epidemiol. 1973;98:289–300. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardson L S, Yolken R H, Belshe R B, Camargo E, Kim H W, Chanock R M. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for measurement of serological response to respiratory syncytial virus infection. Infect Immun. 1978;20:660–664. doi: 10.1128/iai.20.3.660-664.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts N J, Prill A H, Mann T N. Interleukin 1 and interleukin 1 inhibitor production by human macrophages exposed to influenza virus or respiratory syncytial virus. J Exp Med. 1986;163:511–519. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.3.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura T, Ishihara M, Lamphier M S, Tanaka N, Oishi I, Aizawa S, Matsuyama T, Mak T W, Taki S, Taniguchi T. An IRF-1-dependent pathway of DNA damage-induced apoptosis in mitogen-activated T lymphocytes. Nature. 1995;376:596–599. doi: 10.1038/376596a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamura T, Ueda S, Yoshida M, Matsuzaki M, Mohri H, Okubo T. Interferon-γ induces ICE gene expression and enhances cellular susceptibility to apoptosis in the U937 leukemia cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229:21–26. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thornberry N A, Bull H G, Calaycay J R, Chapman K T, Howard A D, Kostura M J, Miller D K, Molineaux S M, Weidner J R, Aunins J, Elliston K O, Ayala J M, Casano F J, Chin J, Ding G J F, Egger L A, Gaffney E P, Limjuco G, Palyha O C, Raju S M, Rolando A M, Salley J P, Yamin T T, Lee T D, Shively J E, MacCross M, Mumford R A, Schmidt J A, Tocci M J. A novel heterodimeric cysteine protease is required for interleukin-1β processing in monocytes. Nature. 1992;356:768–774. doi: 10.1038/356768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamazaki H, Tsutsumi H, Matsuda K, Nagai K, Ogra P L, Chiba S. Effect of maternal antibody on IgA antibody response in nasopharyngeal secretion in infants and children during primary respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2115–2119. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-8-2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]