Abstract

Introduction and importance

Despite being the longest and containing a greater proportion of the gastrointestinal tract's mucosal surface area, the small bowel is where <2 % to 5 % of gastrointestinal cancers can occur. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is the rarest risk factor for the development of small intestinal cancers. Here we report a case of perforated poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the jejunum for which Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is identified.

Case presentation

A 25-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department with generalized peritonitis caused by a perforated jejunal mass. The patient underwent an emergency exploratory laparotomy. There was 800 ml of thin pus in the peritoneal cavity and 5 cm by 6 cm perforated mass over the jejunum which extends to the mesentery. Palpable intraluminal polyps with an inverted serosal surface for some of them were identified. The pus was sucked out, and the mass was resected with its mesenteric lymph nodes and segments containing polyps. Subsequently, end-to-end hand-sewn anastomosis was performed, and the abdomen was closed. The histopathology report showed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, stage IIIC (PT3, PN2), and Peutz-Jeghers polyps, suggesting Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

Clinical discussion

Even though small bowel malignancy is a rare entity, early detection is a challenging issue, especially when it happens below the ligaments of the trietz. Surgical resection offers the only potential cure for small bowel malignancy.

Conclusion

We conclude that patients with long-term, nonspecific abdominal complaints are good candidates for evaluation and investigation without overlooking small bowel malignancy. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome was a potential risk factor in our case.

Keywords: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, Small bowel, Case report

Highlights

-

•

Small-bowel malignancy is a rare primary gastrointestinal malignancy.

-

•

Although the presentation of small-bowel malignancy is not specific, perforation is not a common presentation.

-

•

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is one of the rarest documented risk factors for the development of small-intestinal cancers.

1. Introduction

Small bowel malignant lesions account for 2 %–5 % of all primary gastrointestinal malignancies. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is one of the rarest documented risk factors for the development of small intestinal cancers [1] [2]. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is an uncommon autosomal dominant condition characterized by gastrointestinal polyps that are hamartomatous and mucocutaneous pigmentation [3] [4] [5]. PJS hamartomatous polyps most frequently occur in the small intestine (jejunum, ileum, and duodenum, in that order of predominance), but they can develop in the stomach, large bowel, and, in rare instances, extraintestinal locations, such as the bronchus, renal pelvis, and urinary bladder [6] [7]. The incidence is one in 8300 to one in 200,000 live births [5] [8]. Patients with PJS have a nine-fold increased risk of dying from any other disease, and their relative risk of dying from gastrointestinal cancer is 13–15 times higher than that of the general population [6] [9]. Colorectal, breast, gastric, small intestine, and pancreatic cancers are the most prevalent. Additional malignancies encompass the biliary tree and gallbladder, esophagus, lungs, thyroid gland, ovary, and cervix in females, and testes in males [7]. Histological diagnosis of a Peutz-Jeghers polyp is essential for the diagnosis of PJS. Histologically, they are characterized by smooth muscle arborization within the lamina propria associated with an elongated epithelial component and cystic gland dilatation [10] [7]. In this study, we report a case of this rare entity with particular histological features in a young man who developed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the jejunum with perforation. This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE Criteria [11].

2. Case presentation

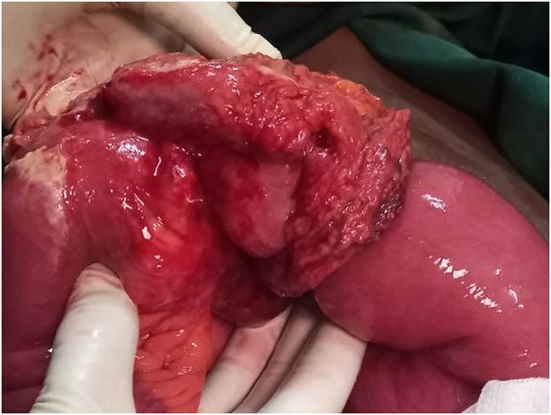

A 25-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department with a complaint of exacerbation of abdominal pain lasting one day. The patient also had the following symptoms: loss of appetite, fever, and vomiting of ingested matter in three episodes. He had abdominal discomfort and intermittent cramps for three months, for which he was treated with dyspepsia and intestinal parasites at different health institutions. He had a history of alcohol consumption but no history of cigarette smoking. He had no clear family history of a known gastrointestinal disease or mucocutaneous pigmentation. A physical examination revealed an acutely sick patient with a blood pressure of 110/79 mmHg, a pulse rate of 126 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 22 breaths per minute, and a temperature of 37.4 °C. His oxygen saturation level was 96 % in atmospheric air. The abdomen was flat, with direct and rebound tenderness over the entire abdomen. The formed stool was found on a digital rectal examination with a normal anal sphincter tone. A basic laboratory investigation was performed, and the CBC showed an increased white blood cell count of 11,200 per microliter with a neutrophil count of 81 % and a hemoglobin level of 12 mg/dl. Because of its emergent condition, other investigations, such as abdominal CT scans, were not performed. Clinically, secondary peritonitis was diagnosed, and management was initiated. The fluid resuscitation per deficit was replaced with Normal saline 0.9 %. Parenteral antibiotics (ceftriaxone and metronidazole) were administered, and an NG tube was inserted and catheterized. After obtaining informed written consent, the patient was operated upon as an emergency. Under general anesthesia, a midline vertical laparotomy incision was made, and the abdomen was explored. There was 800 ml of thin pus in the peritoneal cavity and more in the left paracolic gutter and the pelvic cavity. There was 5 cm by 6 cm of mass over the jejunum, 30 cm from the ligament of the treitz, which has an extension to the mesentery, and 0.5 cm by 0.5 cm of perforation on the anti-mesenteric side that had omental adhesion (Fig. 1). Palpable jejunal mesenteric lymphadenopathies were found. There were four palpable intraluminal polyps with an inverted serosal surface for some of them, which were identified within 10 cm proximal and 20 cm distal to the mass (Fig. 2). The abdomen was thoroughly explored, and no liver or gastrointestinal tract involvement was observed. The other organs appeared to be normal. The pus was sucked out, and the mass was resected with its mesentery at a 5 cm free margin on the mesenteric side. The resection included enlarged lymph nodes and segments containing polyps, with a total of 40 cm of jejunum. Other than palpable polyps, the lumens were visualized, and nearby small polyps were included. The end-to-end hand-sewn anastomosis was then performed. The mesenteric defect was then closed. The abdomen was lavaged with warm saline until it became clear. After checking for gauze count, the fascia and skin were closed in layers. The patient was successfully extubated and transferred to the recovery room. The resected mass was sent for histopathology. The patient started sips after 36 h, when the bowel became active and tolerated. The patient recovered and was discharged on the 5th post-operative day uneventfully.

Fig. 1.

Perforated jejunal mass on the antimesenteric side, which is wrapped with omentum.

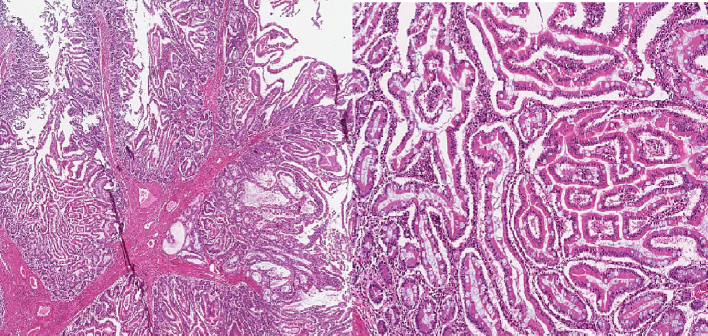

Fig. 2.

Inverted serosa of the jejunum due to polyps proximal and distal to the perforation site.

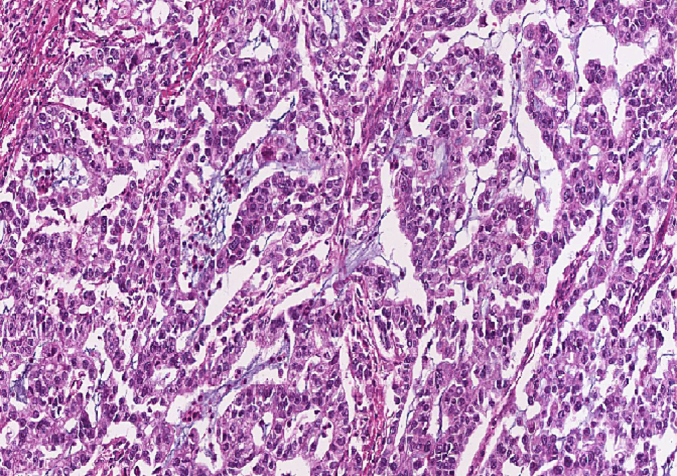

After three weeks, the histopathology report came. Gross examination: 36 cm long gray-white resected segment of small bowel with 6 cm × 4 cm matted lymph nodes at the mesenteric site. C/S: 3 cm × 3 cm × 2 cm gray-white circumferential solid mass identified, which is far from all surgical margins. Six pedunculated polyps were identified, the largest measuring 2.5 cm × 2 cm × 1 cm. Twelve lymph nodes were identified at the mesentery largest 3 cm × 1 cm, and smallest 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm. Microscopic examination: histologic section of small bowel mass shows poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma invading sub-serosa (Fig. 3). Lymphovascular invasion is also observed. Histology sections from the polyps show arborizing strands of smooth muscle and overlying non-neoplastic small bowel epithelium (Fig. 4). The tumor affected seven of the 12 lymph nodes that had been identified. All surgical margins are free. It was concluded to be poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma stage IIIC (PT3, PN2) plus Peutz-Jeghers polyps suggestive of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. No genetic testing is done because it is not available at our setup. We tried to have an upper and lower GI endoscopy and small bowel follow-through, but we couldn't succeed due to the patient's financial limitations. The patient had follow-up at 2 weeks and 6 weeks postoperatively at the surgical referral clinic, with a good recovery. At the last visit, he was linked to the oncology department for adjuvant chemotherapy. Before starting chemotherapy, he didn't have an imaging study due to financial reasons. After a basic laboratory investigation, he was started on oral 5FU: capecitabine chemotherapy, but after one year, unfortunately he lost from follow-up.

Fig. 3.

Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 4.

Hamartomatous polyps with tree-like arborizing smooth muscle cores dividing lobules of glandular villous epithelium, consistent with Peutz-Jeghers polyp adenomatous changes are seen.

3. Discussion

Despite making up 90 % of the gastrointestinal tract's mucosal surface area and 75 % of its length, the small intestine is a place where <2 % to 5 % of gastrointestinal cancers originate. However, the most frequent malignant tumors in most series include adenocarcinomas (30 %–50 %), SI-NETs (carcinoid tumors; 20 %–30 %), GISTs (15 %), and lymphomas (15 %) [1]. Consuming red meat, ingesting smoked or cured foods, having Crohn's disease, celiac sprue, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome are among the documented risk factors for developing small-intestinal cancers [2]. In our case, a poorly differentiated primary small bowel malignant tumor is detected with histologically confirmed Peutz-Jeghers polyps. Unlike duodenal cancer, which can manifest as alimentary tract, biliary, or pancreatic duct obstruction, adenocarcinoma distal to the ligament of Treitz is often asymptomatic at an early stage. Even when symptomatic, the symptoms associated with early disease are usually nonspecific (abdominal pain, malaise, bloating). The advanced disease generally produces obstructive symptoms, GI bleeding, or perforation [12]. In this reported case, the patient presented with peritonitis after tumor perforation after having nonspecific abdominal complaints for months. PJS is a very rare inherited polyposis syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentations, gastrointestinal polyposis, and an increased risk of cancer [5] [8]. The sites most commonly affected by Peutz-Jeghers polyps in the gastrointestinal tract are the jejunum, colorectal region, duodenum, and stomach, in decreasing order of frequency [5]. In a similar way, in our reported case, we found polyps in the jejunum with malignant transformation. The World Health Organization (WHO) has established the following criteria for diagnosing PJS clinically: Three or more histologically confirmed Peutz–Jeghers polyps, Any number of Peutz–Jeghers polyps with a family history of PJS, Characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation with a family history of PJS, or Any number of Peutz–Jeghers polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation [3] [10] [13] [14]. In our case, the patient had more than three histologically confirmed Peutz-Jeghers polyps. Clinical symptoms related to polyps include bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain from intussusception, obstruction, or infarction of polyps [3] [7] [10]. They frequently manifest in childhood, with 33 % of instances being detected by the time a child is ten years old. At the age of 20, 50 % of patients experience symptoms associated with polyps [3] [10]. Mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation is generally seen on the lips, around the mouth, eyes, nostrils, and on the buccal surface; which was not found in our patient [13]. Regarding the treatment of PJS, treatment is generally not necessary for mucocutaneous lesions. If however needed, laser therapy can be tried. For the intestinal polyps, endoscopic polypectomy, rather than segmental resections of the bowel, has been recommended. It is recommended to do endoscopic surveillance for polyps or gastrointestinal cancer every 1–2 years from the age of 20 years [2] [15]. Because the entire length of the gastrointestinal tract may be affected, surgery is reserved for symptoms such as obstruction or bleeding or for patients in whom polyps develop adenomatous features [2]. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome patients are at a higher risk of cancer and hence have an increased mortality rate. Patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome have a 13- to 15-fold increased tumor incidence compared to normal individuals, with a potential 20 % incidence of malignant tumors. In Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, malignancy is thought to develop in adulthood and rarely affects youngsters [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [9] [10]. Moreover, although the cancer risks for PJS patients are age dependent because the older the patient, the higher the risk of developing cancer, malignancies can also develop in PJS patients at a young age. To date, the youngest case of GI cancer in a PJS patient was a 7-year-old boy diagnosed with well-differentiated adenocarcinoma in the jejunum [16]. In patients with PJS the median age at first GI cancer diagnosis was 42 years (range 15–76 years) as compared to jejunal adenocarcinomas in the general population, which occur most commonly around the age of 60 [17] [18]. The most frequent neoplasm in patients with PJS is the colonic tumor (57 %), followed by breast (45 %), pancreas (36 %), stomach (29 %), ovary (21 %), small intestine (13 %), and uterus (10 %) tumors [8]. In our case, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma is identified with lympho-vascular involvement at the jejunum. Surgical resection offers the only potential cure once a diagnosis of small bowel malignancy is made. The surgical therapy for jejunal and ileal malignancies usually consists of a wide-local resection of the intestine harboring the lesion. For adenocarcinomas, a wide excision of the corresponding mesentery is done to achieve regional lymphadenectomy, as is done for adenocarcinomas of the colon [1] [2] [12]. Lifestyle factors and predisposing conditions such as familial adenomatous polyposis, hereditary non polyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Crohn's disease, and celiac disease are risk factors for small bowel adenocarcinoma, just as they are for colorectal cancer. Recent molecular research, however, reveals genetic variations among these cancers and points to novel therapeutic avenues [19]. Due to the increasing awareness of this uncommon malignancy, particular guidelines, such as the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (2020) and the French Intergroup Clinical Practice Guideline (2018) have been established [20] [21]. Both concur that, depending on the patient's and the tumor's characteristics, surgical excision is the most effective course of treatment. After resection, adjuvant therapy has not been examined in any trials. PRODIGE 33-BALLAD trial (NCT02502370) is a prospective worldwide Phase III research study evaluating adjuvant chemotherapy vs observation now in progress [19]. NCCN guidelines recommend MMR or MSI testing for all patients with small bowel adenocarcinoma because it can function as a prognostic and/or predictive marker and can help identify patients who should be tested for Lynch syndrome. NCCN recommendations for adjuvant therapy are applied to stage II and stage III. In stage II, the adjuvant therapy is dependent on MSI-H or dMMR and high-risk features (T4 stage, close or positive surgical margins, few lymph nodes examined <5 for duodenal or <8 for jejunal/ileal primary tumor location or tumor perforation) [20]. Adjuvant chemotherapy improved disease-free survival but not overall survival [2]. Because jejunoileal adenocarcinoma is considered radioresistant, radiation therapy is restricted to the palliative setting [12]. Many patients have intra-abdominal metastases at initial surgery, with R0 resection (i.e., no gross or microscopic disease left) achieved in only 50 % to 65 % of cases [1]. Complete resection of adenocarcinomas located in the jejunum or ileum is associated with 5-year survival rates of 20 % to 30 % [2]. Patients with locally unresectable disease may undergo neoadjuvant therapy and should be routinely monitored for conversion to resectable disease [19].

4. Conclusion

Even though small bowel malignancy is a rare entity, early detection is challenging, especially when it occurs below the ligaments of the trietz. We concluded that patients with long-term, nonspecific abdominal complaints are good candidates for evaluation and investigation without overlooking small bowel malignancy. We reported a case of poorly differentiated jejunum adenocarcinoma with perforation that resulted in generalized peritonitis. Intra-operatively detected polyps proximal and distal to the mass are found to be due to Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, which is a rare risk factor for the development of small bowel malignancies. Even though we are limited by genetic analysis, this PJS can happen without family history.

Patient perspective

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval is not required for case reports deemed not to constitute research at our institution.

Sources of funding

This case report did not receive any specific fund from organizations.

Author contribution

Fufa Miresa Benti: Operated the patient, and conceived, interpreted the findings, wrote the original manuscript, and submitted.

Badhaasaa Beyene: Reviewed and edited the manuscript, and involved in the management decisions of the patient.

Munewor Abdulhadi: Involved in decisions on the management of the patient.

Abdulaziz Mohamud: Involved on the patient operation.

Anteneh Belachew: Examined the specimen of the tissue biopsied, interpreted histopathology findings, and prepared the report.

Guarantor

Name: Dr. Fufa Miresa (MD)

Email: fufa.miresa@gmail.com

Registration of research studies

Not applicable

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zinner Michael J., Ashley Stanley W. OJH. Abdominal Operations. https://www.ptonline.com/articles/how-to-get-better-mfi-results Available from:

- 2.Cheung L.Y. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. vol. 56. 1975. Principles of surgery. 206–207 p. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shetty K.H., Shetty D., Pai M.R. Vol. 11. 2020. An Unusual Case of Peutz – Jeghers Syndrome With Polyposis-associated Adenomatous Change; pp. 1–6. (Figure 3) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duan S., Wang G., Zhong J., Ou W., Wang F., Li J. 2017. Peutz – Jeghers Syndrome With Intermittent Upper Intestinal Obstruction; pp. 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu J., Jiang W.E.I. 2015. Acute Intussusception and Polyp With Malignant Transformation in Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome: A Case Report; pp. 1008–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shakil S., Aldaher Z., Divalentin L. 14(7) 2022. Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome Presenting With Anemia: A Case Report; pp. 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tacheci I., Kopacova M., Bures J. 2021. Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. (March) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Syarifuddin E., Masadah R., Erasio R., Aboyaman J., Faruk M. CASE REPORT – OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Surgery Case Reports Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in a woman presenting as intussusception: a case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. [Internet] 2021;79:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.01.053. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reports C., Bhattacharya S., Mahapatra S.R., Nangalia R., Palit A., Morrissey J.R., et al. 2010. Melaena With Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome: A Case Report; pp. 2–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabrine D., Vladimir A.B., Ahmed J., Mahjoub E. El. 4(1) 2020. Peutz Jeghers Syndrome Revealed by Intestinal Intussuception: A Case Report and a Review of the Literature; pp. 124–129. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Maria N., Kerwan A., Franchi T., Agha R.A. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2023;109(5):1136. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuidema George D., Nyhus Lloyd, Shackelford Richard T. 2 vol. 2019. Shackelford’s Surgery of the Alimentary Tract 8th Ed; pp. 804–807. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Report C . 2022. CASE REPORT Unusual Case of Small Bowel Intussusception in Adult Revealing a Peutz- Jeghers Syndrome; pp. 13–16. (April 2021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mozaffari H.R., Rezaei F., Sharifi R., Mirbahari S.G. Vol. 2016. 2016. Case Report Seven-Year Follow-up of Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. (Figure 2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poudel P., Jahan R. 12(7) 2021. Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome: A Case Report; pp. 154–156. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z., Wang Z., Wang Y., Wu J., Yu Z., Chen C., et al. 2022. High Risk and Early Onset of Cancer in Chinese Patients With Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome; pp. 1–12. (August) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lier MGF Van, Westerman AM, Wagner A, Looman CWN, Wilson JHP, Rooij FWM De, et al. High Cancer Risk and Increased Mortality in Patients With Peutz e Jeghers Syndrome:141–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Patel J., Zhang H., Sohail C.S., Montanarella M., Butt M. 14(1) 2022. Jejunal Adenocarcinoma: A Rare Cause of Small Bowel Obstruction Case Presentation; pp. 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira R., Tojal A., Gomes A., Casimiro C., Moreira S., Vieira F., et al. 2021. Adenocarcinoma of the Jejunum: Management of a Rare Small Bowel Neoplasm; pp. 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adenocarcinoma S.B., Chen Y., Ciombor K.K., Cohen S.A., Grem L., Hoffe S.E., et al. 17(9) 2023. Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma, Version 1.2020; pp. 1109–1133. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Locher C., Batumona B., Afchain P., Carrère N., Samalin E., Cellier C., et al. Small bowel adenocarcinoma: French intergroup clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatments and follow-up (SNFGE, FFCD) Dig. Liver Dis. [Internet] 2018;50(1):15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.09.123. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]