Abstract

Background

Emergency cases can be presented at any time of the day or night. All small animal practitioners need to have the skills to triage and stabilize common emergency cases, even if the ultimate goal is to refer the animal to another facility.

Objective and procedure

The third and final part of this 3-part review article series discusses arrhythmias typical in emergency cases and the approach to animals that are presented with an inability to stand up and walk normally. A stepwise method to categorize and stabilize these cases is outlined, along with helpful tips to optimize the referral experience, if indicated.

Results

Recognizing and knowing how to treat tachy- and bradyarrhythmias is important in stabilizing a dog’s or cat’s condition. Understanding how to differentiate the various reasons that a dog or cat is unable to stand on its own allows a veterinarian to both treat and communicate outcome expectations for those animals.

Conclusion and clinical relevance

Do not refer emergent cases before basic stabilization is completed. Many emergency cases can either be worked up by the primary veterinarian or sent to a referral clinic on an appointment basis after appropriate stabilization steps have occurred.

Résumé

Triage de base chez les chiens et les chats : Partie III

Mise en contexte

Les cas d’urgence peuvent être présentés à toute heure du jour ou de la nuit. Tous les praticiens des petits animaux doivent avoir les compétences nécessaires pour trier et stabiliser les cas d’urgence courants, même si le but ultime est de référer l’animal vers un autre établissement.

Objectif et procédure

La troisième et dernière partie de cette série d’articles de synthèse en trois parties traite des arythmies typiques des cas d’urgence et de l’approche des animaux présentant une incapacité à se lever et à marcher normalement. Une méthode par étapes pour catégoriser et stabiliser ces cas est décrite, ainsi que des conseils utiles pour optimiser l’expérience de référence, si cela est indiqué.

Résultats

Reconnaître et savoir comment traiter les tachy- et bradyarythmies est important pour stabiliser l’état d’un chien ou d’un chat. Comprendre comment différencier les différentes raisons pour lesquelles un chien ou un chat est incapable de se tenir seul permet au vétérinaire de traiter et de communiquer les attentes en matière de résultats pour ces animaux.

Conclusion et pertinence clinique

Ne référez pas les cas urgents avant que la stabilisation de base ne soit terminée. De nombreux cas d’urgence peuvent être traités par le vétérinaire initial ou envoyés à une clinique de référence sur rendez-vous après que les mesures de stabilisation appropriées ont été prises.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Introduction

Primary care veterinarians in private general and emergency practice often carry out basic triage and stabilize animals from the “red” or “orange” groups [see Figure 1 in Part I of this review (1)] before referring them for definitive diagnostics and management. This article continues our outline of the most frequently encountered emergency situations [see Figure 2 in Part I of this review (1)] leading to referral in both dogs and cats and provides guidelines for how to stabilize animals before transport.

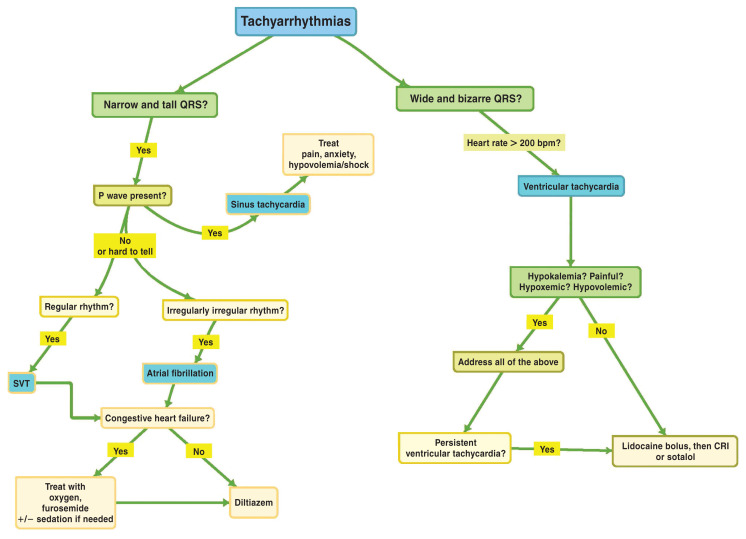

Figure 1.

Approach to tachyarrhythmias.

CRI — Constant rate infusion; SVT — Supraventricular tachycardia.

Figure 2.

Approach to bradyarrhythmias.

AVB — Atrioventricular block; UTO — Urinary tract obstruction.

Section 1: Arrhythmias

In the normal heart, electrical impulses begin in the sinoatrial (SA) node in the right atrium and travel down the SA tracts, causing atrial depolarization (P wave); these impulses terminate in the atrioventricular (AV) node in the floor of the right atrium, with the AV node controlling impulse conduction to the ventricles. After traversing the AV node, impulses spread down the bundle of His and through the right and left bundle branches, depolarizing the septum and ventricles and creating the QRS complex. The T wave is ventricular repolarization.

Electrical activity originating in the SA node creates a P wave; tall, upright QRS complexes occur when the impulse travels down through the AV node into the ventricles. If electrical activity originates from another pacemaker (at AV node or between SA and AV nodes), no P wave is generated but the QRS complex remains tall and upright. The QRS complex becomes wide and bizarre when electrical activity originates below the AV node in the ventricle.

Arrhythmias are broadly classified into bradyarrhythmias and tachyarrhythmias, based on the ausculted heart rate. Pulse rates are not reliable due to arrhythmia-related pulse deficits. Arrhythmias cause clinical signs because cardiac output is inadequate due to failure of ventricular filling (rhythm is too fast) or the heart rate is too slow.

Clinical signs in dogs and cats range from weakness, lethargy, and collapse (from arrhythmia) to anorexia, vomiting, and inappetence (decreased gastrointestinal blood flow). Dogs and cats with concurrent heart failure will have dyspnea, tachypnea, and abdominal distention attributed to concurrent left- (pulmonary edema) or right-sided congestive heart failure (2). Cats commonly have respiratory signs related to pleural effusion, plus mild hypothermia (2).

Step #1: Is breathing affected (i.e., potential left-sided congestive heart failure)?

If the animal is presented in respiratory distress with auscultable crackles (“loud auscultation”) or a “quiet auscultation” due to pleural effusion (more common in cats than dogs), stabilize the respiratory distress [see Figure 3 in Part I of this review (1)].

Figure 3.

A — Atrial fibrillation. An ECG from a 12-year-old wolfhound dog with atrial fibrillation and dilated cardiomyopathy. Note the tall, upright QRS complexes, irregularly irregular rhythm, and absence of P waves. B — Ventricular tachycardia. An ECG from a 10-year-old golden retriever with ventricular tachycardia. Note the wide and bizarre QRS complexes. C — Third-degree atrioventricular block. A 6-lead ECG from a 12-year-old dog with 3rd-degree atrioventricular block. Note the slow heart rate and P waves not associated with QRS complexes. D — Sick sinus syndrome. A 14-year-old West Highland white terrier dog was presented due to collapsing events at home. Note the tachycardia followed by severe bradycardia with pauses.

Images courtesy of T. Gerlach, DACVIM — Cardiology.

Step #2: Tachyarrhythmia versus bradyarrhythmia

Determine heart rate to decide treatment (Figures 1, 2). A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is ideal for diagnosing rhythms (e.g., differentiating supraventricular tachyarrhythmias) (3) but a 3-lead ECG is adequate for triage.

Tachyarrhythmias

Most tachyarrhythmias in dogs have a rapid heart rate (150 to 300 bpm). Take breed and size into account; some nervous, small-breed dogs may have acceptably rapid heart rates in a hospital setting, whereas normal, large-breed dogs rarely have heart rates > 150 bpm. Typical heart rates in cats with tachyarrhythmias are > 250 bpm.

Background

Tachyarrhythmias can be supraventricular (tall, upright QRS complexes) or ventricular (wide, bizarre QRS complexes). Details regarding the most common tachyarrhythmias are provided in Table 1. A summarized approach to treatment and stabilization is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the most common tachyarrhythmias in dogs and cats.

| Supraventricular tachyarrhythmia | Ventricular tachyarrhythmia | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhythm diagnosis | Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) | Atrial fibrillation (A-fib) | Ventricular tachycardia (V-tach) |

| Appearance |

|

|

|

| Heart rate | Dogs: Median 270 bpm during periods SVTa Cats: > 240 bpm |

Dogs: Typically > 200 bpm Cats: Typically > 240 bpm |

Dogs: Typically > 180 bpm Cats: Typically > 200 bpm |

| Cause |

|

|

Dogs: Originates below the AV node from within ventricles Multiple causes:

|

| Comment |

|

Dogs:

|

|

A-fib — Atrial fibrillation; AV — Atrioventricular; DCM — Dilated cardiomyopathy; HCM — Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; RCM — Restrictive cardiomyopathy; RUC — Restrictive unclassified cardiomyopathy; SA — Sinoatrial; SVT — Supraventricular tachycardia, V-tach — Ventricular tachycardia.

References

Finster TS, DeFrancesco TC, Atkins CE, Hansen BD, Keene BW. Supraventricular tachycardia in dogs: 65 cases (1990–2007). J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2008;18:503–510.

Fousse SL, Tyrrell WD, Dentino ME, Abrams FL Rosenthal SL, Stern JA. Pedigree analysis of atrial fibrillation in Irish wolfhounds supports a high heritability with a dominant mode of inheritance. Canine Genet Epidemiol 2019;6:11.

Bartoszuk U, Keene BW, Baron Toaldo M, et al. Holter monitoring demonstrates that ventricular arrhythmias are common in cats with decompensated and compensated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Vet J 2019;243:21–25.

Dogs

Tachyarrhythmias in dogs can be due to primary heart disease (e.g., dilated cardiomyopathy, infectious endocarditis, advanced congestive heart failure, cardiac neoplasia) or noncardiac causes (e.g., toxins, pancreatitis, sepsis, pheochromocytoma, splenic disease, immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, severe uremia, electrolyte abnormalities, or gastric dilation-volvulus) (2).

Cats

Tachyarrhythmias in cats are due to primary structural heart disease (left ventricular concentric hypertrophy; restrictive, dilated, or unclassified cardiomyopathy) (4) or noncardiac causes (e.g., hyperkalemia-induced ventricular tachycardia) (5).

Emergency stabilization: Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias (SVT)

Sustained atrial fibrillation (A-fib, a subset of SVT) (Figure 3 A) with clinical signs (syncope, pale gums, weakness) or peracute, sustained SVT with clinical signs requires immediate treatment.

Identify and treat electrolyte disturbances

Obtain a baseline electrolyte panel and PCV/TP to rule out severe electrolyte imbalance or anemia that needs specific treatment.

Treat the rhythm

Treatment aims to slow the heart rate and improve ventricular filling and cardiac output. Options include the following:

-

Diltiazem. This calcium channel blocker increases effective and functional refractory periods of the AV node, slowing AV node conduction and ventricular (QRS) heart rate.

— Give 0.1 mg/kg, IV (dogs only), over 3 to 5 min (or slower), preferably with continuous ECG monitoring. Repeat up to 2 times IV; wait 15 min between doses.

— Give 0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg, PO (dogs) or 7.5 mg total dose, PO (cats), up to q8h. Start low and titrate up. Wait 30 to 45 min, then give more if there is no change in heart rate and the maximum dose has not been reached.

Sotalol (cats). Give 2 mg/kg, PO, q12h (lower dose if known kidney disease) (2). Can use compounded tablets. First treat concurrent congestive heart failure. Sotalol is a beta-blocker and a potassium channel blocker used to slow ventricular heart rate.

Vagal maneuver (dogs). Apply sustained (5 to 10 s), gentle compression over the carotid sinus (caudal to dorsal aspect of the larynx) (2) or to both eyes to increase vagal nerve firing and transiently slow AV nodal conduction and heart rate (monitor with ECG). Typically only works for SVT but not for A-fib or ventricular tachycardia (V-tach).

Practice tips

If a dog or cat has left-sided congestive heart failure and is in respiratory distress, address this before transfer [see Figure 3 in Part I of this review (1)].

For all tachyarrhythmias, treatment goals are to slow heart rate and improve ventricular filling and cardiac output.

Atrial fibrillation and other SVTs usually do not convert to a sinus rhythm. Treatment slows the heart rate (ideally < 160 to 170 bpm in a dog or < 180 bpm in a cat).

In the absence of diltiazem (or sotalol, for cats), discuss case with the referral institution. If the animal is relatively stable (walking, alert, with palpable pulses ± blood pressure ≥ 80 mmHg systolic), the institution might recommend transport; if less stable, they will discuss options.

Give IV heart medications slowly while monitoring with ECG.

Emergency stabilization: Ventricular tachyarrhythmias

Treat ventricular arrhythmias (Figure 3 B) immediately if an animal is hemodynamically unstable or has sustained ventricular tachycardia (> 2 to 3 min). Hemodynamic instability is indicated by hypotension, collapse, heart rates > 180 bpm (dogs) or > 250 bpm (cats), and multiform VPCs (QRS complex appearances differ due to differing locations of impulse generation).

Identify and treat electrolyte disturbances

Obtain a baseline electrolyte panel and PCV/TP to detect severe electrolyte imbalances or anemia that needs specific treatment.

Treat the rhythm

Convert to a slower, sinus rhythm that improves cardiac output.

-

Lidocaine (first choice for dogs). Bolus 2 mg/kg, IV, slowly over 3 to 5 min while monitoring with ECG. This sodium channel blocker slows myocardial conduction velocity. Conversion should happen during or shortly after injection is complete.

— If improvement occurs, start lidocaine constant rate infusion (CRI) (40 to 80 μg/kg per minute).

— If no improvement, repeat lidocaine bolus up to 3 more times (maximum 8 mg/kg total dose) with 3 to 5 min between boluses.

-

— For cats, bolus 0.2 to 0.75 mg/kg, IV, slowly over 3 to 5 min.

Repeat bolus once or twice.

Cats are very sensitive to lidocaine; use with caution.

— If no rhythm improvement occurs in dogs with lidocaine, consider procainamide.

-

Procainamide (dogs only). Bolus 2 mg/kg, IV, slowly over 3 to 5 min. This sodium channel blocker slows myocardial conduction velocity.

— If improvement occurs, use a procainamide CRI of 25 to 40 μg/kg per minute.

— If no improvement, procainamide bolus can be repeated (maximum 16 mg/kg).

-

Sotalol (first choice for cats, dogs). Give 1 to 2 mg/kg, PO, q12h. Start immediately (cats), if other drugs are not available, or once arrhythmia is controlled with a CRI of lidocaine or procainamide. It is a beta-blocker and potassium channel blocker.

— Stock compounded 10- or 20-milligram tablets to accommodate cat body weights.

— Do not use until concurrent congestive heart failure has been treated.

If the dog or cat is hemodynamically stable, look for the underlying cause. Cats require an echocardiogram since V-tach results primarily from heart disease. In dogs, V-tach usually indicates noncardiac disease. Rule out hypoxemia, hypovolemia, pain, electrolyte imbalances, and increased vagal tone [usually due to abdominal or thoracic disease but sometimes increased intracranial pressure or intraocular pressure (IOP)].

Provide oxygen supplementation. If dog is proven or suspected hypoxemic, provide oxygen [see Part I of this review (1)].

Treat hypovolemia. Hypovolemia is corrected with crystalloids or, rarely, blood products when there is severe active bleeding [see Part II of this review (6)].

Evaluate electrolytes. Measure electrolytes with in-house analyzer. See Part II of this review (6) for hyperkalemia management; see other resources for treatment of other electrolyte abnormalities.

Treat pain. Injectable opioid pain medications (morphine, hydromorphone, buprenorphine, methadone) may be considered for pain or suspected increased IOP.

Treat elevated IOP. Consider measurement of IOP, especially if 1 or both eyes are red, buphthalmic, or painful or vision appears reduced. If IOP is > 30 mmHg, consistent with glaucoma, initiate appropriate treatment (refer to other sources for glaucoma treatment).

If all the above are addressed and the dog is still in V-tach, consider medical management with antiarrhythmics (as previously described) while obtaining imaging for abdominal, thoracic, or intrinsic cardiac disease. Further treatment is dependent on the imaging results.

Practice tips

Address left-sided congestive heart failure and respiratory distress before transferring the animal! If you lack the drugs described to treat V-tach, oxygen, furosemide, and sedation for cats and dogs in congestive heart failure will still help stabilize them during the peracute phase.

The treatment goal for all tachyarrhythmias is to slow the heart rate and improve ventricular filling and cardiac output.

Canine V-tach is more likely due to systemic versus cardiac disease.

A ventricular rhythm with heart rate < 160 bpm is termed “accelerated idioventricular rhythm” (formerly, “slow V-tach”). Its causes are the same as for V-tach but, due to its slow rate, the rhythm is cardiovascularly stable and does not need, or respond to, anti-arrhythmic drugs. Dogs with an idioventricular rhythm require a systemic workup for underlying disease.

Be aware: The IV lidocaine dose is much lower for cats, to avoid adverse effects.

Always give IV heart medications slowly while monitoring with an ECG.

Preparing to refer a dog or cat with a tachyarrhythmia

Bradyarrhythmias

Bradyarrhythmias are identified by careful cardiac auscultation and are defined as heart rate < 60 bpm (dogs) or < 140 bpm (cats). Bradyarrhythmias can be regular, irregular, continuous, or intermittent. An ECG is mandatory for differentiating bradyarrhythmias and determining treatment and prognosis (Figure 2).

Background

Bradyarrhythmias usually result from AV dysfunction (AV blocks, where impulses from the SA node are not properly communicated to the ventricles) or SA node dysfunction, causing perpetual or intermittent lack of electrical impulse generation (atrial standstill or sick sinus syndrome). An AV block manifests as prolongation between P and QRS waves as the impulse takes longer to pass the AV node (1st-degree AV block), P waves that do not pass through the AV node and result in QRS complexes (2nd-degree AV block), or separate P-wave and QRS-wave rhythms that do not coordinate (3rd-degree AV block). Atrial standstill lacks P waves. Sick sinus syndrome (SSS) most commonly occurs in West Highland white terrier and miniature schnauzer dogs; they have intermittent periods without P waves (Figure 3 C, D).

The most common clinical signs associated with bradycardia are weakness, syncope, lethargy, and anorexia due to low cardiac output and an inability to increase the heart rate in response to stress or activity. Bradyarrythmias can result from intrinsic heart disease of the SA or AV nodes or cardiac conduction systems, but cardiac medications, environmental toxicities (e.g., Digitalis plants), and painkillers/sedatives may also cause bradyarrhythmias.

Electrolyte disturbances can cause a bradyarrhythmia. Atrial standstill in dogs is predictably secondary to hyperkalemia (K > 7.7 mg/dL) (5,7) resulting from diseases such as uroabdomen, urethral obstruction, Addisonian crisis, or anuric renal failure. Atrial standstill is sometimes caused by underlying primary heart disease in English springer spaniel dogs (8), and persistent atrial standstill was reported in 1 cat (9).

In cats, complete (3rd-degree) AV block can be isolated or associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; the AV node and surrounding tissues are replaced by fibrous tissue (10,11). Cats with 3rd-degree AV block are usually middle-aged to older and have concurrent systemic diseases that might account for many of their clinical signs.

Some animals with bradyarrhythmias have congestive heart failure and are presented with respiratory distress [see Figure 3 in Part I of this review (1)].

Emergency stabilization of animals with bradyarrhythmias

Immediate treatment is needed if the animal is hemodynamically unstable or has syncopal episodes. This usually only occurs with 3rd-degree AV blocks, some 2nd-degree AV blocks with very severe bradycardia, SSS, and atrial standstill. First-degree AV blocks (prolonged P-QRS intervals only) and most 2nd-degree AV blocks (intermittently dropped QRS complexes) rarely need treatment.

Evaluate electrolytes. If available, measure electrolytes with an in-house analyzer to identify abnormalities that need treatment. See Part II of this review (6) for treatment of hyperkalemia; consult other resources for treating other electrolyte abnormalities.

Treatment: Second-degree AV block

The ECG has missing QRS complexes, either randomly or at predictable intervals. This uncommonly requires treatment.

Reverse any drugs, if applicable (e.g., sedation drugs).

Atropine may be required (0.04 mg/kg, IV) to improve severe bradycardia [heart rate < 60 bpm (dogs) or < 80 bpm (cats)].

Treatment: Third-degree AV block

The ECG has complete dissociation between P waves and QRS complexes (P wave rate is typically 80 to 100 bpm and QRS rate is 40 to 60 bpm; Figure 3 C). Emergency treatment required only if syncopal.

Pacemaker placement is definitive treatment; this reduces clinical signs but does not enhance survival (2).

Treatment: Sick sinus syndrome (dogs)

The ECG has prolonged pauses between heartbeats (few seconds) or short periods of SVT followed by bradycardia with long pauses between heartbeats. This arrhythmia is very “random” (Figure 3 D). Asymptomatic animals do not require treatment and some SSS patients can improve P wave generation or AV nodal conduction by blocking parasympathetic tone.

-

Medical management:

— Terbutaline. Give 2.5 to 5.0 mg total dose, q8 to 12 h; or SC, 0.01 mg/kg, q4h. β2 adrenergic receptor agonist blocks parasympathetic tone (increases heart rate).

— Theophylline (extended release). Give 10 mg/kg, IV, q12h. Bronchodilator with mild chronotropic effects (shortens sinus cycle length and decreases conduction time through SA node).

If medical management fails in a symptomatic SSS patient, a pacemaker is indicated.

Treatment: Atrial standstill

Bradycardia with NO P waves and tall, upright QRS complexes.

Treat hyperkalemia, if identified (see Part II of this review (6)].

Treat underlying cause (e.g., relieve urethral obstruction).

Refer animal to a cardiologist if no metabolic cause is identified.

Practice tips

-

It can be difficult to distinguish between 2nd- and 3rd-degree AV blocks or definitively diagnose SSS, especially at very slow heart rates.

Conduct an atropine response test (0.04 mg/kg atropine, IV, with ECG monitoring).

Atropine will increase heart rate in 2nd-degree AV blocks. No response is noted in 3rd-degree AV blocks or SSS because atropine cannot improve AV nodal conduction in complete AV blocks or end-stage SA nodal dysfunction.

Evaluate electrolytes in all bradyarrhythmias.

Unless the bradyarrhythmia is due to a known toxin ingestion or sedatives, both of which will resolve with supportive care and time, refer animal to a cardiologist for evaluation.

Preparing to refer a dog or cat with a bradyarrhythmia

The time to refer an animal with a bradyarrhythmia is after treating any respiratory distress from congestive heart failure [see Figure 3 in Part I of this review (1)].

Provide the referral institution with times and doses of all drugs administered, as well as ECG recordings pre- and post-medication.

If an atropine response test was done, provide ECG recordings pre- and post-treatment.

Call ahead to the referral institution to discuss the incoming case.

Section 2: Dogs or cats unable to stand or walk

These cases range from animals physically unable to those reluctant to stand (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Approach to an animal unable to stand or walk.

Step #1: Is this animal stable?

The first step is to determine cardiovascular stability. Determine pulse/heart rate, blood pressure, and mentation [see Part II of this review (6)]. Hypotension, poor perfusion, and shock will limit the ability to stand or walk. If there is shock [tachycardia or bradycardia (in cats), weak pulse quality, decreased mentation] and/or hypotension, then resuscitate [see Part II of this review (6)].

Step #2: Determine categorical reason why the animal is not standing or walking

Metabolic disease

Background

Metabolic diseases can limit mobility; animals with these usually can stand and walk but are choosing not to do so. There are numerous causes, including anemia, hypoglycemia, hepatic failure, diabetic ketoacidosis, severe renal failure, and high fever.

Emergency stabilization

See Part II of this review (6) for more information about stabilization of metabolic diseases.

Orthopedic disease

Some dogs (less commonly cats) with orthopedic disease will be presented with “not being able to walk” as the complaint. They are reluctant to walk but able to move their limbs. An orthopedic examination identifies pain on manipulation or palpation of joints or bones.

Background

Common orthopedic diseases in dogs causing reluctance to stand include fractures (limbs or pelvis), joint luxations, cranial cruciate ligament ruptures, and polyarthropathies. Cats can have limb or pelvic fractures and, if older, joint-related osteoarthritis, but cranial cruciate ligament ruptures and polyarthropathies are uncommon.

A detailed history and complete physical examination are important. Trauma implies fractures or joint luxations, whereas a fever suggests polyarthritis or another inflammatory bone or joint disease.

Dogs aged < 12 mo commonly have fractures but also skeletal diseases, such as panosteitis or hypertrophic osteodystrophy, causing long bone pain and fever. Cats aged < 12 mo commonly have traumatic fractures, but also suffer from nontraumatic spontaneous capital physeal fractures resulting from delayed physeal closure (up to ~4 y) (12).

Adult dogs and cats can have traumatic fractures and nontraumatic fractures resulting from neoplasia or pathologic bone disease. Adult dogs (and cats) more commonly suffer from cranial cruciate ligament disease and polyarthritis; the latter can be primary idiopathic, immune-mediated disease or secondary to infectious diseases (e.g., Lyme disease).

Emergency stabilization

Analgesia

Orthopedic disease requires analgesia. Hydromorphone or methadone (0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg) or buprenorphine (dog: 0.005 to 0.01 mg/kg; cat: 0.01 to 0.02 mg/kg), IV, SQ, or IM provides analgesia for 4 to 6 h. Some cats are more sensitive to full mu agonists (hydromorphone and methadone), but a single dose before referral is acceptable and is often preferred to buprenorphine since it can be reversed.

Avoid NSAIDs or steroids as they may complicate diagnostics. The NSAIDs are contraindicated with renal disease and delay the use of immunosuppressives (for polyarthritis).

Closed fractures

Fractures distal to the elbow or stifle benefit from splints, which should extend from the toes to the joint above the fracture to immobilize the limb, reduce discomfort, and lessen damage. Fractures involving the elbow or stifle or more proximally are more difficult to immobilize and are often not splinted (or may require a shoulder or hip spica splint).

Open fractures

For open fractures, treat the wound before applying a splint or bandage. Bite wound-induced fractures and weapon-related fractures are always open (13), but other trauma, especially in cats, which have less soft tissue in the distal limbs than dogs (14), can also lead to open fractures. In dogs, comminuted fractures and those affecting the tarsus, metatarsals, or phalanges are the most likely to be open (13). Cats are reported to have ~2× as many open fractures as dogs (29% versus 14%, respectively) (13). Comminuted fractures and those affecting the tarsus are the most likely to be open in cats (13).

The wound should be cleaned and lavaged thoroughly under sedation (or general anesthesia) and analgesia before applying a bandage and/or splint. Fill the wound with sterile lubricant and clip surrounding fur. Lavage with copious amounts (1 to 2 L) of 0.9% saline or other sterile isotonic fluid to remove visible debris (15). Following lavage, apply a splint (if possible) or cover the wound. If the animal is going to be referred, sedation and partial cleaning followed by application of a bandage or splint and communication with the referral clinic regarding the need for further cleaning is an acceptable approach.

Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics (1st-generation cephalosporin; e.g., cefazolin) in dogs with fresh wounds or a drug with greater anaerobic spectrum (e.g., clindamycin) for suspected tissue necrosis (15). In cats, antibiotic choices include cephalosporins for fresh wounds or a drug with greater anaerobic spectrum, such as potentiated penicillins (e.g., ampicillin-sulbactam), especially for tissue necrosis (14).

Oral fractures

These may require referral. Most oral fractures are considered open (77% in 1 canine study) (14) and commonly occur secondary to blunt trauma or bite wounds. In the study, small-breed dogs were overrepresented and > 70% of fractures involved premolars and molars (16). Cats with maxillomandibular trauma commonly have additional, non-maxillomandibular trauma or fractures (17).

Dogs and cats with oral fractures should receive antibiotics effective against oral bacteria (e.g., potentiated penicillins or clindamycin). A soft commercial muzzle or tape muzzle can temporarily stabilize fractures rostral to the premolars. Consult other sources regarding tape muzzles. If possible, lavage the mouth with saline.

Vascular disease

Background

Dogs

Vascular disease not affecting the spinal cord and causing an inability to walk is rare in dogs (representing only 7.7% of acutely paralyzed dogs) (18) and is usually due to aortic thromboembolism (ATE) causing paresis and/or ataxia in hind limbs or, rarely, all 4 limbs (19,20). In 1 study, 35/85 dogs with ATE (41%) were nonambulatory at presentation (21). In > 1/2 of these cases, a key physical examination finding was weak-to-absent femoral pulse (20–22).

Canine thromboembolic diseases are inevitably secondary to hypercoagulability induced systemic disease, most commonly hyperadrenocorticism, hypothyroidism, renal disease, cardiac disease, or neoplasia (20–22). They are typically chronic (history of limb weakness for days to weeks; median: 1.5 to 8 wk) (19,20,22), but limb paralysis is uncommon (7.7 to 20% of cases) (19,20,22).

Cats

In cats, vascular disease is relatively common, with 60% of these cats presenting emergently unable to walk (18). Feline vascular disease is usually ATE, which is a common sequela of cardiac disease (specifically, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) (18,23). Cats acutely have paresis or paralysis in affected limbs, accompanied commonly by pain and a lack of femoral pulses (23). The right front leg is sometimes affected and might lack digital pulses. Paw pads in affected limbs may be discolored and cold (23), and rectal temperatures are often low due to reduced blood flow. Traditional recommendations comparing blood glucose in blood samples taken from the affected limb and either a normal limb or the jugular vein to confirm an ATE (decreased blood glucose and increased lactate in the affected limb) have been questioned. Approximately 50% (24) to 86% (25) of cats also have dyspnea resulting from concurrent left-sided congestive heart failure (24), although affected cats may be tachypneic simply due to pain.

Emergency stabilization

Dogs

Anticoagulant therapy (heparin, clopidogrel, and/or aspirin) will be required but is initially withheld pending diagnostics. No specific, pre-hospital stabilization protocol is required, other than giving analgesia, addressing other clinical signs, and providing owners a realistic estimate for the workup.

Cats

Opioids will relieve discomfort and help to determine if increased respiratory rate and effort are due to pain or respiratory distress. Use hydromorphone or methadone (0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg) or buprenorphine (0.01 to 0.02 mg/kg), IV, IM, or SC; avoid butorphanol as its analgesic effects are short-lived and it will antagonize other opioids. If these cats have true dyspnea from congestive heart failure, then treat the respiratory distress [see Figure 3 in Part I of this review (1)].

Cats will require anticoagulant therapy plus treatment of the underlying cardiac disease; anticoagulants are usually initially withheld pending diagnostics. No specific, pre-hospital stabilization protocol is required, beyond giving pain medications and treating congestive heart failure.

Practice tips

Carefully palpate for pulses with dogs that have a history of ataxia and paresis, to diagnose vascular disease.

Educate owners that sudden onset of vascular-related paralysis or paresis in their cat is indicative of a heart problem that cannot be cured.

The right front leg in cats can be affected by an ATE when the right subclavian branch of the brachiocephalic artery is occluded by a clot leaving the heart rather than the aorta.

Neurologic disease

Dogs and cats with neurologic disease are physically unable to walk due to decreased or absent voluntary movement (weakness/paresis or paralysis) or incoordination (ataxia). Neurologic disease has 3 localizations: brain, spinal cord, and neuromuscular disease.

Background

Diseases of the brain, especially the cerebellum and brainstem (including the central vestibular system), can cause ataxia severe enough that a dog or cat appears to fall over or be unable to walk. Animals with brain disease typically can move their limbs but are nonambulatory. Brain diseases include neoplasia, vascular events, and inflammatory/infectious diseases (meningitis), but similar clinical signs can result from metabolic conditions (e.g., sodium derangements or hypoglycemia).

Dogs and cats can have peripheral vestibular disease (affecting cranial nerve VIII and/or inner ear) without concurrent brainstem disease. Just as with central vestibular disease, some animals are so “dizzy” that they have difficulty standing and walking.

Neuromuscular disorders are caused by aberrant communication between the motor neuron and the muscle, most commonly at the neuromuscular junction. Classic examples in dogs include myasthenia gravis, polyradiculoneuritis (e.g., coon-hound paralysis), and tick paralysis. These diseases are very rare in cats but include tick paralysis and tail-pull injuries. Neuromuscular disorders can cause paresis or paralysis and can affect all 4 limbs, only the hind limbs, or 1 limb, in the case of disorders affecting nerve(s) at 1 location (e.g., brachial plexus avulsion).

Spinal cord disorders can cause paresis or paralysis and affect all 4 limbs, just the hind limbs, or, rarely, 1 limb. Common diseases affecting the spinal cord in dogs include intervertebral disk disease, luxations or subluxations of the vertebrae, spinal cord inflammatory or infectious disease (e.g., meningitis or meningomyelitis), neoplasia, fibrocartilaginous embolism, and discospondylitis. Cats commonly have inflammatory or spinal cord infectious disease (e.g., meningitis or meningomyelitis) or neoplasia and, more rarely, intervertebral disk disease, luxations or subluxations of the vertebrae, or fibrocartilagenous emboli.

Emergency stabilization

Neurologic cases require emergent referral if the animals are nonambulatory paraparetic or para- or tetraplegic, or clinical signs are progressing rapidly. If you are concerned that a dog or cat has a spinal fracture or luxation, then, if possible, transfer the animal on a firm, flat surface (i.e., “back board”) to minimize movement that could worsen spinal luxations or fractures. If surgical intervention is indicated (e.g., compressive spinal cord disease), the prognosis is better with surgery before loss of motor control. Severely abnormal mentation (obtundation, stupor, or coma), irrespective of ability to walk, suggests a need for referral.

If a dog’s mentation is normal but it is painful on examination, give methadone or hydromorphone (0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg) or buprenorphine (dog: 0.005 to 0.01 mg/kg, cat: 0.01 to 0.02 mg/kg, IM, IV, or SC) before referral. Avoid steroids or NSAIDs as they may complicate diagnostics.

If mentation is abnormal (obtunded, stupor, coma), implicating brain involvement, consider giving mannitol (0.5 to 1 g/kg, through a filter over 20 to 30 min) before referral. A dog or cat with abnormal mentation and (relatively) high blood pressure (systolic pressure > 150 mmHg) with either a normal or low heart rate (< 60 bpm in dogs; < 140 bpm in cats) may have increased intracranial pressure. Mannitol will induce diuresis, reducing intravascular volume and intracranial pressure. Avoid fluid administration while giving mannitol. Avoid giving steroids, which can complicate future diagnostics.

Practice tips

Bilateral cruciate tears can mimic paraparesis. Before diagnosing a dog (or cat) with spinal cord disease or other neurologic cause of paraparesis, do a full orthopedic examination.

If you are unsure if a dog or cat with suspected spinal cord disease has motor ability, do not hesitate to refer the case. It is important not to delay treatment if motor ability has been lost and it is best to allow the referral group to schedule workup and surgery (if indicated).

If a dog (or cat) with suspected spinal cord disease has motor ability at the time of referral, advise the owners that the referral team may initially hospitalize and then reassess over time.

Vascular disease is a common cause of paresis in cats; palpate pulses and limb temperature in all cats with weakness in their hind limbs.

Preparing to refer a dog or cat that cannot stand or walk

Refer cardiovascularly stable animals only. Do not transport animals with hypotension or shock until after fluid resuscitation, or those with congestive heart failure until respiratory signs have been addressed.

Do not transport animals with untreated hypoglycemia or severe hyperkalemia. Prolonged hypoglycemia can cause seizures or other lasting neurologic signs secondary to neuroglycopenia (26), and hyperkalemia can cause death due to arrhythmias.

Carefully palpate for femoral pulses to ensure that the owners are properly informed (i.e., vascular versus orthopedic disease in cats).

Give opioids for analgesia. Avoid steroids and NSAIDs.

Clip, clean, and cover open fractures. Take a photograph of the original wound to send to the referral practice.

Consider splinting fractures distal to the elbow or stifle.

In cases involving reduced mentation, consider giving mannitol.

Discuss the case with the referral institution to obtain an estimate and establish client expectations.

Conclusion

The primary veterinarian seeing emergent cases has a very important role to play in stabilizing and optimizing the conditions of cats and dogs before referring them for more definitive diagnostics. Teamwork between primary and referral institutions optimizes communication and animal care. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (kgray@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Thomovsky E, Ilie L. Basic triage in dogs and cats: Part I. Can Vet J. 2024;65:162–172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeFrancesco TC. Management of cardiac emergencies in small animals. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2013;43:817–842. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santilli RA, Perego M, Crosara S, et al. Utility of 12-lead electrocardiogram for differentiating paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardias in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:915–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Côté E, Jaeger R. Ventricular tachyarrhythmias in 106 cats: Associated structural cardiac disorders. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:1444–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norman BC, Côté E, Barrett KA. Wide-complex tachycardia associated with severe hyperkalemia in three cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2006;6:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilie L, Thomovsky E. Basic triage in dogs and cats: Part II. Can Vet J. 2024 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tag TL, Day Thomas K. Electrocardiographic assessment of hyperkalemia in dogs and cats. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2008;18:61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonfara S, Loureiro JF, Swift S, et al. English springer spaniels with significant bradyarrhythmia-presentation, troponin I and follow-up after pacemaker implantation. J Small Anim Pract. 2010;51:155. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2009.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gavaghan BJ, Kittleson MD, McAloose D. Persistent atrial standstill in a cat. Aust Vet J. 1999;77:574–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1999.tb13192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellum HB, Stepien RL. Third-degree atrioventricular block in 21 cats (1997–2004) J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:97–103. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2006)20[97:tabic]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaneshige T, Machida N, Itoh H, Yamane Y. The anatomical basis of complete atrioventricular block in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Comp Pathol. 2006;135:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNicholas WT, Wilkens BE, Blevins WE, et al. Spontaneous femoral capital physeal fractures in adult cats: 26 cases (1996–2001) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;221:1731–1736. doi: 10.2460/javma.2002.221.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Millard RP, Weng H. Proportion of and risk factors for open fractures of the appendicular skeleton in dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;245:663–668. doi: 10.2460/javma.245.6.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corr S. Complex and open fractures: A straightforward approach to management in the cat. J Fel Med Surgery. 2012;14:55–64. doi: 10.1177/1098612X11432827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Popovitch CA, Nannos JA. Emergency management of open fractures and luxations. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2000;30:645–655. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(00)50043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitshoff AM, de Rooster H, Ferreira SM, Steenkamp G. A retrospective study of 109 dogs with mandibular fractures. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2013;26:1–5. doi: 10.3415/VCOT-12-01-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulherin BL, Snyder CJ, Soukup JW, Hetzel S. Retrospective evaluation of canine and feline maxillomandibular trauma cases: A comparison of signalment with non-maxillomandibular traumatic injuries (2003–2012) Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2014;27:192–197. doi: 10.3415/VCOT-13-06-0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi G, Stachel A, Lynch AM, Olby NJ. Intervertebral disc disease and aortic thromboembolism are the most common causes of acute paralysis in dogs and cats presenting to an emergency clinic. Vet Rec. 2020;187:e81. doi: 10.1136/vr.105844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lake-Bakaar GA, Johnson EG, Griffiths LG. Aortic thrombosis in dogs: 31 cases (2000–2010) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;241:910–915. doi: 10.2460/javma.241.7.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winter RL, Sedacca CD, Adams A, Orton EC. Aortic thrombosis in dogs: Presentation, therapy, and outcome in 26 cases. J Vet Cardiol. 2012;14:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruehl M, Lynch AM, O’Toole TE, et al. Outcome and treatments of dogs with aortic thrombosis: 100 cases (1997–2014) J Vet Intern Med. 2020;34:1759–1767. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goncalves R, Penderis J, Chnag YP, Zoia A, Mosley J, Anderson TJ. Clinical and neurological characteristics of aortic thromboembolism in dogs. J Sm Anim Pract. 2008;49:178–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2007.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassan MH, Abu-Seida, Torad FA, et al. Feline aortic thromboembolism: Presentation, diagnosis, and treatment outcomes of 15 cats. Open Vet J. 2020;10:340–346. doi: 10.4314/ovj.v10i3.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Payne JR, Borgeat K, Brodbelt DC, Connolly DJ, Luis Fuentes V. Risk factors associated with sudden death versus congestive heart failure or arterial thromboembolism in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Vet Card. 2015;17:S318–S328. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoeman JP. Feline distal aortic thromboembolism: A review of 44 cases (1990–1998) J Fel Med Surg. 1999;1:221–231. doi: 10.1053/jfms.1999.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgan RK, Cortes Y, Murphy L. Pathophysiology and aetiology of hypoglycaemic crises. J Small Anim Pract. 2018;59:659–669. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]