Abstract

肝炎病毒感染是肝细胞癌的主要致病因素之一。甲型肝炎病毒(HAV)通常引起急性感染,临床病理长期追踪结果显示HAV感染与肝细胞癌发生有一定联系。乙型肝炎病毒(HBV)或丙型肝炎病毒(HCV)的慢性感染可导致长期肝脏炎症和肝硬化,影响多条细胞凋亡和增殖相关信号通路,是病毒感染导致肝细胞癌的最常见诱因。HBV X蛋白(HBx)基因突变与肝细胞癌发病率密切相关,HCV核心蛋白的表达可导致肝细胞脂质积累,促进肿瘤发生。临床丁型肝炎病毒(HDV)感染常伴随HBV的共感染,从而增加慢性肝炎风险。戊型肝炎病毒(HEV)感染通常呈急性,近年HEV在器官移植和免疫缺陷患者中慢性感染增多。HEV慢性感染易导致肝硬化而增加肝细胞癌风险。本文概述了近年来肝炎病毒感染导致肝脏免疫应答异常和肝细胞癌发生的研究进展,以期有助于寻找病毒感染的早期检测、有效干预和疫苗接种的措施。

Keywords: 肝细胞癌, 肝炎病毒, 病毒性肝炎, 肝硬化, 慢性感染, 综述

Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a serious neoplastic disease with increasing incidence and mortality, accounting for 90% of all liver cancers. Hepatitis viruses are the major causative agents in the development of HCC. Hepatitis A virus (HAV) primarily causes acute infections, which is associated with HCC to a certain extent, as shown by clinicopathological studies. Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections lead to persistent liver inflammation and cirrhosis, disrupt multiple pathways associated with cellular apoptosis and proliferation, and are the most common viral precursors of HCC. Mutations in the HBV X protein (HBx) gene are closely associated with the incidence of HCC, while the expression of HCV core proteins contributes to hepatocellular lipid accumulation, thereby promoting tumorigenesis. In the clinical setting, hepatitis D virus (HDV) frequently co-infects with HBV, increasing the risk of chronic hepatitis. Hepatitis E virus (HEV) usually causes acute infections. However, chronic infections of HEV have been increasing recently, particularly in immuno-compromised patients and organ transplant recipients, which may increase the risk of progression to cirrhosis and the occurrence of HCC. Early detection, effective intervention and vaccination against these viruses may significantly reduce the incidence of liver cancer, while mechanistic insights into the interplay between hepatitis viruses and HCC may facilitate the development of more effective intervention strategies. This article provides a comprehensive overview of hepatitis viruses and reviews recent advances in research on aberrant hepatic immune responses and the pathogenesis of HCC due to viral infection.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Hepatitis virus, Viral hepatitis, Liver cirrhosis, Chronic infection, Review

肝细胞癌占原发性肝癌的90%。由于其早期诊断困难,往往出现明显症状时已经是中晚期,最终影响治疗的有效性[1]。临床统计数据表明,病毒性肝炎持续性感染导致的慢性肝炎和肝硬化是引发肝细胞癌的主要因素[2]。在五种不同的肝炎病毒中,HBV和HCV在肝细胞癌的致病因素中最为重要[2-3]。全球范围内,由HBV感染导致的肝细胞癌占45%[4];在我国,由HBV所致的肝细胞癌更是占到了84%[5]。由于受到免疫微环境的压力筛选,随着HBV感染时间的推移,其基因序列突变也随之增加,这不仅增加了癌症发生的相关风险,同时也增加了HBV感染预防和治疗的难度[6]。我国HCV慢性患者约450万人,其中有20%左右的患者会发展为肝硬化甚至肝细胞癌[7]。HAV感染不会直接导致肝细胞癌的发生,但其对免疫细胞的影响是多方面的,包括影响免疫细胞的侵袭、干扰信号转导和诱导凋亡等,从而削弱免疫应答,增加肝细胞癌发生风险[8]。HDV可以与HBV共感染,加剧肝脏损伤,使肝炎更易呈慢性化发展,因此HDV的潜在危害不可忽视[9]。HEV是导致急性肝炎的主要病原体。近些年,免疫缺陷人群中HEV慢性感染造成肝硬化的病例日益增多,其感染导致肝细胞癌发生的潜在风险也日益增大[10]。此外,肝炎病毒急性感染会间接促进肝细胞癌的发生,肝炎病毒急性感染介导的组织损伤可能进一步发展为自身免疫性肝炎,并随后发展为肝硬化甚至肝细胞癌,这是一个病毒和宿主动态互作的过程[11]。“癌症进化发育学”为肝炎病毒感染导致肝癌的机制给出了完整的理论框架:以HBV为代表的肝炎病毒在感染宿主的过程中,一方面,病毒会在宿主的免疫微环境压力下发生突变以适应宿主;另一方面,宿主会在病毒诱导下使体内原来沉默的原癌基因再次表达[12]。肝炎病毒感染在宿主细胞内触发一系列分子事件,如表观遗传修饰、介导NF-κB、Wnt和p53等信号通路的激活与肝细胞癌的风险密切相关[13]。本文对五种肝炎病毒直接诱导肝细胞癌或通过调控宿主因子导致肝细胞癌的相关研究进展进行总结,以期为肝炎病毒感染导致肝细胞癌发生的临床和基础研究提供参考。

1. 甲型肝炎病毒感染导致肝细胞癌发生的免疫机制

HAV为小RNA病毒科嗜肝病毒属,是单股正链RNA病毒,基因组大小为7.8 kb,病毒呈二十面体立体对称结构,直径约27 nm,存在无囊膜和类囊膜两种病毒形式[14]。HAV基因组编码的结构蛋白为组成病毒颗粒的主要成分,包括VP1、VP2、VP3和VP4;非结构蛋白参与病毒的复制和转录过程,主要包括聚合酶和其他辅助蛋白[14]。

过去一直认为HAV感染与肝细胞癌的发展无关[15],但统计结果显示,感染HAV会削弱患者的抵抗力,从而增加感染HCV的概率,而HCV与肝细胞癌密切相关[16]。此外,HAV能介导组织损伤,这意味着其可能可以间接促进肝细胞癌的发生[16]。研究显示,HAV相关性组织损伤并非由病毒本身直接导致,而是通过引发强烈的CD8+ T细胞免疫反应介导,非HAV特异的CD8+ T细胞、NK细胞和NKT细胞等其他免疫细胞也参与其中[8]。此外,在HAV感染小鼠模型中,由MAVS激活信号介导的固有凋亡似乎是肝炎的原因之一[17]。宿主和病毒因子的遗传变异也可以影响HAV感染的严重程度,如T细胞免疫球蛋白1和IL-18结合蛋白的基因变异与HAV感染的严重程度有关[8]。此外,HAV急性感染患者可能发展为自身免疫性肝炎,进而发展为肝硬化和肝细胞癌[18-19]。这些机制并不是相互排斥的,而是能单独或共同作用,导致患者肝脏损伤,增加肝细胞癌发生的潜在风险。

综上所述,HAV感染导致免疫失调或肝脏损伤对肝细胞癌的发病、进展和预后产生潜在影响,需要进行更大规模的研究以深入了解这一过程。

2. 乙型肝炎病毒和丁型肝炎病毒感染导致肝细胞癌发生的免疫机制

2.1. HBV感染

HBV为嗜肝DNA病毒科正嗜肝DNA病毒属,病毒颗粒直径约为42 nm,是一种能引发慢性肝炎的常见病原体[20]。HBV慢性感染是肝细胞癌发生的主要诱因,超过50%的肝细胞癌患者是HBV携带者。并且,HBV携带人群其终生肝细胞癌发病风险比非感染人群高25~37倍[21]。

HBV慢性感染引发持续性炎症反应导致的肝细胞损伤和修复是肝细胞癌发展的基础。此外,HBV的基因组可以整合到肝细胞的基因组中,该过程可能会导致基因组的变异和不稳定,进而导致肝细胞的恶性转化[22]。临床上,与其他肝炎病毒感染的肝细胞癌患者比较,更多HBV感染的肝细胞癌患者在没有肝硬化的情况下表现出肝细胞癌的症状[23]。与其他非病毒因素肝细胞癌患者比较,HBV感染的肝细胞癌患者肝硬化比例较低,表明HBV可能通过直接激活细胞中某些信号通路来影响细胞增殖或抑制细胞凋亡,从而影响肝细胞癌进展。

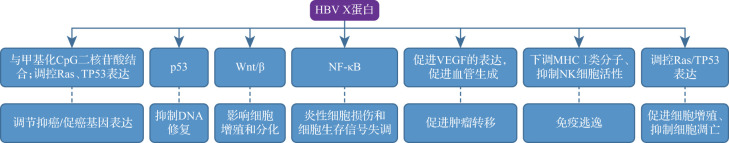

HBV通过激活NF-κB、Wnt/β-catenin和p53等细胞信号转导通路来促进细胞增殖或抑制凋亡[22]。来源于病毒X基因的HBx在HBV感染的发病机制和病毒转录过程中扮演着关键角色,其与肝细胞癌的发生具有一定相关性[24],见图1。NF-κB在炎症和免疫反应中发挥着关键作用,其过度活化会导致炎症性细胞损伤和细胞生存信号的失衡[25-26]。有研究显示,HBx可能通过激活NF-κB信号通路促进肝细胞恶性增殖,最终导致肝细胞癌[27]。Wnt/β信号通路在肝炎病毒感染过程中也扮演着重要角色。该通路在正常情况下调控细胞的增殖和分化,但其异常激活与多种癌症类型相关。有研究发现,HBx可以通过激活NF-κB上调β-catenin的表达,最终激活Wnt信号通路[27-28],从而促进肝细胞癌形成。p53是重要的肿瘤抑制蛋白,其对DNA损伤的监测和修复起着关键作用。当DNA受到损伤时,p53会激活细胞内的一系列基因,这些基因可以促进细胞凋亡或使细胞停止分裂,并进行DNA修复[29]。HBx通过与p53结合干扰其功能,阻止p53与DNA的结合,从而抑制其对DNA损伤的监测和修复功能,同时还促进p53的降解[30]。研究显示,HBx能与甲基化CpG二核苷酸结合,促进甲基化过程并调节基因表达[31]。HBx可以促进血管生成,即形成新血管,从而帮助肝癌细胞生长和扩散[32]。HBx还可以抑制NK细胞活性,并下调MHCⅠ类分子的表达,使肝癌细胞不易被T淋巴细胞识别和攻击[33]。此外,HBx参与调控Ras蛋白和TP53等多种癌症发生相关蛋白[34]。HBx在HBV相关肝癌发病中起着核心作用,是肝细胞癌抑制治疗极具潜力的靶点。

图1. HBV X蛋白诱导肝细胞癌发生的机制及靶点示意图.

HBV:乙型肝炎病毒;NF-κB:核因子κB;VEGF:血管内皮生长因子;MHC:主要组织相容性复合体.

此外,HBV感染引发的炎症因子会刺激APOBEC3B显著上调[35]。与APOBEC3A比较,APOBEC3B诱发基因变异的能力相对温和,其诱导的变异水平仍然在细胞耐受范围内而不会导致细胞凋亡,因此促进APOBEC3B上调的遗传多态性会增加肝细胞癌在内的多种癌症的发生风险[36]。

总的来说,一方面,HBV感染会导致肝硬化,增加肝细胞癌发生风险;另一方面,HBV感染可调控NF-κB、Wnt/β和p53等多个信号通路,且这些信号调控并不是独立的,其复杂互动导致了细胞失去正常的生长控制和DNA损伤修复机制,最终推动肝细胞癌发展。

2.2. HDV与HBV共感染

HDV为小核糖核酸病毒,病毒颗粒呈球形,直径约36 nm;其基因组为环状单股负链RNA,全长1679 bp,编码核心蛋白和包膜蛋白;其复制需要借助HBV的包膜蛋白才能完成装配[37]。HBV对HDV的组装、释放、保护和吸附等多方面均有辅助作用[38]。HDV主要通过输血、注射及性接触进行传播。据估计,全球乙型肝炎表面抗原携带合并HDV感染者有2000万例[39]。在临床上,如果检测到HDV感染,一定伴有HBV感染。因临床上HBV感染较为多见,常掩盖或漏诊HDV感染,故临床HDV感染诊断率不高。当病情较重或突然加重,应警惕HDV与HBV的共感染[40]。研究显示,HDV和HBV共感染会促进肝硬化形成[41]。同时,肝硬化是否发展为肝细胞癌与患者体内HDV血症水平相关[41]。

目前,HDV在肝细胞癌发生中的作用仍存在争议,更多人认为HDV与HBV共感染加重了HBV相关临床症状或促进了肝硬化进程,从而间接导致了肝细胞癌发生。HDV是否可以独立诱导肝细胞癌的产生,及其在肝癌发生中的潜在作用仍需进一步研究。

3. 丙型肝炎病毒感染导致肝细胞癌发生的免疫机制

HCV是单股正链RNA病毒,基因组长度约为9.5 kb,属于黄病毒科,由Houghton团队于1989年发现[42]。HCV基因组编码三种结构蛋白(core、E1和E2)和六种结构蛋白(NS2、NS3、NS4A、NS4B、NS5A和NS5B)[43]。HCV是RNA病毒,较易变异,不同地区的分离株只有68.1%~91.8%的核苷酸相同[44]。HCV主要通过母婴、血液和性接触等进行传播。全球HCV慢性感染者有1.3亿~1.7亿[45]。HCV感染者中有60%~80%会发展为慢性感染,后者中15%~30%在20年内出现肝硬化,一部分患者可能进一步发展为肝细胞癌[46]。与非HCV感染人群比较,HCV感染者中肝细胞癌的发病率增加15~20倍[47]。HCV感染与酒精、吸烟以及伴随糖尿病的肥胖症共同作用,通过促进肝纤维化及肝硬化进程增加肝细胞癌的风险[48-51]。HBV或HIV与HCV共同感染增加了HCV慢性感染患者发生肝细胞癌的风险[13, 52]。

HCV感染或病毒编码的毒力蛋白导致免疫细胞对肝细胞的持续性损伤、改变肝细胞凋亡信号以及TGF-β诱导的肝纤维化等潜在因素在HCV慢性感染进展为肝细胞癌的过程中发挥了重要作用(图2)。通常情况下,由于天然免疫及细胞免疫(炎症反应)作为一种机体自我保护机制,可以抵抗病毒感染,其对宿主是有益的。然而,HCV对人体免疫系统来说非常狡猾。一方面,先天免疫中由于HCV NS3蛋白质通过切割负责诱导Ⅰ型干扰素的MAVS来抑制天然免疫的激活[53]。这是HCV难以被先天免疫清除从而产生慢性感染的重要原因之一。另一方面,在HCV感染过程中,特异性T细胞会攻击HCV阳性细胞,且招募的肝巨噬细胞分泌的TGF-β会促进肝纤维化发生[54]。这意味着HCV慢性感染导致的肝细胞损伤在很大程度上是由于针对病原体及其特异性抗原的免疫反应引起的[55-56]。此外,HCV E2蛋白通过抑制NK细胞促进免疫逃避和慢性感染的建立[57]。

图2. HCV诱导肝细胞癌发生的机制及靶点示意图.

HCV诱导肝细胞癌发生的机制主要包括NS3切割MAVS抑制天然免疫、下调抑癌基因p21的表达、Core等通过与p53或Rb互作扰乱细胞周期、Core或NS2激活TGFβ、Core和NS5A增加活性氧化物质或调控脂滴代谢等途径介导肝脏损伤. TGF:转化生长因子;MAVS:线粒体抗病毒信号蛋白;Rb:视网膜母细胞瘤蛋白;HCV:丙型肝炎病毒.

HCV可以通过调控多种与细胞增殖和凋亡密切相关的细胞信号转导通路导致肝细胞癌发生。其中,NS5A蛋白作为转录因子激活剂,与包括细胞周期/凋亡、脂质代谢在内的各种信号通路相互作用[58-59]。NS5A通过阻止Smad蛋白核转位抑制TGF-β信号传导,导致肝癌细胞系中肿瘤抑制因子p21表达下调[60-61]。Rb和p53蛋白对细胞周期的调控具有重要作用,是重要的抑癌蛋白。HCV Core、NS2、NS5A和NS5B与肿瘤抑制蛋白p53和Rb相互作用,导致其功能紊乱[62-65]。这些相互作用可以促进HCV感染的肝细胞增殖和肿瘤形成,从而增加肝硬化和肝癌风险。HCV感染除了通过调节细胞增殖和凋亡外,还通过调节细胞代谢、活性氧产生和影响DNA修复等途径诱导肝细胞癌发生[66-68]。

4. 结语

肝炎病毒是诱导肝细胞癌发生的主要致病因素。肝炎病毒感染导致肝细胞癌的发生在机制方面存在一些共性,如病毒性肝炎慢性感染导致肝脏的纤维化和肝硬化,诱发肝细胞癌的产生。同时,不同肝炎病毒在诱发肝细胞癌方面也有各自的特点,如HBV和HCV分子通过各自的病毒蛋白,通过影响细胞的凋亡和增殖,从而诱发肝细胞癌。多种肝炎病毒感染导致肝细胞癌发生的过程中存在着许多共性。一方面,肝病患者常伴随持续性的肝脏炎症、肝纤维化以及肝细胞异常再生,这些异常的生理过程不仅导致了肝硬化的形成,还在TP53等基因和表观遗传学层面上引发了一系列的改变。这些变化最终导致异常增生结节(肿瘤癌前病变)的形成,进而发展为肝细胞癌[4]。以HBV为例,在病毒长期慢性感染导致肝细胞癌的过程中,伴随着肝炎病毒突变积累,病毒自身的突变使得病毒能够更好地在人体内生存和繁殖;肝细胞也会发生一系列基因组变化,包括基因扩增、缺失、重排等。这些变化使得肝细胞失去了正常的生长控制和分化能力,进而形成肝癌[69]。癌症进化发育学通过建立完整的理论体系解释了肝炎病毒慢性感染过程中病毒突变和肝癌发生的进程,认为肝癌的发生是一个多阶段、多步骤的过程。在病毒感染初期,免疫系统会识别并攻击病毒,但病毒会通过突变不断逃逸。随着时间的推移,不仅病毒基因组的突变会累积,肝细胞癌发生密切相关基因变异同样会积累,如TP53、CTNNB1、AXIN1等。这些基因变异影响了细胞生长、分化和凋亡的调控,促进了肝细胞癌的发展[70]。另一方面,病毒通过其自身的蛋白(如HBV的HBx以及HCV的Core和NS2等)调节与细胞增殖和凋亡密切相关的细胞信号转导通路,使异常增生细胞获得增殖、侵袭性和生存优势,并最终完成到成熟肝细胞癌的转变[22, 29, 62-65]。这些病毒蛋白对细胞信号转导通路的改变促进肝细胞的恶性转化,从而加速了肝细胞癌的发展。

同时,不同的肝炎病毒感染导致肝细胞癌发生的过程也存在一些差异。如在HBV感染患者中,肝细胞癌也可以发生于不存在肝硬化或明显炎症的慢性肝病患者中,这表明HBV感染有直接致癌作用[23]。然而,在HCV感染者中,如果不伴有重度肝纤维化,则肝细胞癌很少发生[46]。此外,相较于其他肝炎病毒,HCV还可导致脂肪性肝炎,从而加速肝纤维化和肝硬化的进程[58-59]。HEV在器官移植和获得性免疫缺陷综合征等免疫缺陷人群中的慢性感染是其特殊的临床问题[71-72]。尽管鲜有HEV感染导致细胞增殖和凋亡相关的细胞信号通路激活从而诱导肝细胞癌发生的报道,已有流行病学和临床研究提示HEV慢性感染可能是导致肝细胞癌发生的因素之一[73]。

这些共性和差异反映了各种肝炎病毒感染导致肝细胞癌发生的特征和风险因素,对理解和管理这些疾病具有重要意义。

Acknowledgments

研究得到浙江省自然科学基金(LQ22H190003, LQ22C070001)、国家自然科学基金(31830052)、国家重点研发计划(2021YFA1301401)支持. 浙江大学生命科学研究院尚卫娜老师在本文修改中提供帮助

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LQ22H190003, LQ22C070001), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31830052) and National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1301401). SHANG Weina from the Life Sciences Institute, Zhejiang University, provided assistance in the revision of this article

[缩略语]

乙型肝炎病毒(hepatitis B virus,HBV);丙型肝炎病毒(hepatitis C virus,HCV);甲型肝炎病毒(hepatitis A virus,HAV);丁型肝炎病毒(hepatitis D virus,HDV);戊型肝炎病毒(hepatitis E virus,HEV);核因子κB(nuclear factor-κB,NF-κB);线粒体抗病毒信号蛋白(mitochondrial antiviral signaling,MAVS);HBV X蛋白(HBV X protein,HBx);主要组织相容性复合体(major histocompatibility complex,MHC);载脂蛋白B mRNA编辑酶催化多肽(apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide,APOBEC);人类免疫缺陷病毒(human immunodeficiency virus,HIV);转化生长因子(transforming growth factor,TGF);Sma和Mad相关蛋白(Sma- and Mad-related protein,Smad);视网膜母细胞瘤蛋白(retinoblastoma protein,Rb)

利益冲突声明

所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests

参考文献(References)

- 1.FORNER A, REIG M, BRUIX J. Hepatocellular carci-noma[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10127): 1301-1314. 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30010-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.REHERMANN B, NASCIMBENI M. Immunology of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2005, 5(3): 215-229. 10.1038/nri1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.YUEN M F, CHEN D S, DUSHEIKO G M, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2018, 4: 18035. 10.1038/nrdp.2018.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.RUMGAY H, ARNOLD M, FERLAY J, et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040[J]. J Hepatol, 2022, 77(6): 1598-1606. 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.国际肝胆胰协会中国分会, 中国抗癌协会肝癌专业委员会, 中国研究型医院学会肝胆胰外科专业委员会, 等. 乙型肝炎病毒相关肝细胞癌抗病毒治疗中国专家共识[J]. 中华消化外科杂志, 2023, 22(1): 29-41. [Google Scholar]; The Chinese Chapter of International Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association, Chinese Society of Liver Cancer, Society for Hepato-pancreato-biliary Surgery of Chinese Research Hospital Association, et al. Chinese expert consensus on antiviral therapy for hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma (2023 edition)[J]. Chinese Journal of Digestive Surgery, 2023, 22(1): 29-41. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 6.YIN J, LI N, HAN Y, et al. Effect of antiviral treatment with nucleotide/nucleoside analogs on postoperative prognosis of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a two-stage longitudinal clinical study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2013, 31(29): 3647-3655. 10.1200/jco.2012.48.5896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FERNANDEZ C J, ALKHALIFAH M, AFSAR H, et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and chronic viral hepatitis: the interlink[J]. Pathogens, 2024, 13(1): 68. 10.3390/pathogens13010068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WANG M, FENG Z. Mechanisms of hepatocellular injury in hepatitis A[J]. Viruses, 2021, 13(5): 861. 10.3390/v13050861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.TAYLOR J M. Infection by hepatitis delta virus[J]. Viruses, 2020, 12(6): 648. 10.3390/v12060648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.KAMAR N, LHOMME S, ABRAVANEL F, et al. Treatment of HEV infection in patients with a solid-organ transplant and chronic hepatitis[J]. Viruses, 2016, 8(8): 222. 10.3390/v8080222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NISHIYAMA R, KANAI T, ABE J, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma associated with autoimmune hepatitis[J]. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg, 2004, 11(3): 215-219. 10.1007/s00534-003-0878-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.曹广文. “癌症进化发育学”理论的关键功能分子及其在恶性肿瘤防治中的作用[J]. 中国癌症防治杂志, 2023, 15(2): 118-128. [Google Scholar]; CAO Guangwen. Key functional molecules supporting “Cancer Evo-Dev” and their roles in the prophylaxis and treatment of cancer[J]. Chinese Journal of Oncology Prevention and Treatment, 2023, 15(2): 118-128. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 13.ARZUMANYAN A, REIS H M, FEITELSON M A. Pathogenic mechanisms in HBV- and HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2013, 13(2): 123-135. 10.1038/nrc3449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.FENG Z, HENSLEY L, MCKNIGHT K L, et al. A pathogenic picornavirus acquires an envelope by hijacking cellular membranes[J]. Nature, 2013, 496(7445): 367-371. 10.1038/nature12029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.TABOR E, TRICHOPOULOS D, MANOUSOS O, et al. Absence of an association between past infection with hepatitis A virus and primary hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 1980, 9(3): 221-223. 10.1093/ije/9.3.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SHIN E C, SUNG P S, PARK S H. Immune responses and immunopathology in acute and chronic viral hepatitis[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2016, 16(8): 509-523. 10.1038/nri.2016.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.HIRAI-YUKI A, WHITMIRE J K, JOYCE M, et al. Murine models of hepatitis A virus infection[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2019, 9(1): a031674. 10.1101/cshperspect.a031674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SINGH G, PALANIAPPAN S, ROTIMI O, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis triggered by hepatitis A[J]. Gut, 2007, 56(2): 304. 10.1136/gut.2006.111864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MANIVANNAN A, MAZUMDER S, AL-KOURAINY N. The role of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in autoimmune hepatitis[J/OL]. Cureus, 2020, 12(10): e11269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.KARAYIANNIS P. Hepatitis B virus: virology, molecular biology, life cycle and intrahepatic spread[J]. Hepatol Int, 2017, 11(6): 500-508. 10.1007/s12072-017-9829-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.SUNG W K, ZHENG H, LI S, et al. Genome-wide survey of recurrent HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Nat Genet, 2012, 44(7): 765-769. 10.1038/ng.2295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LEVRERO M, ZUCMAN-ROSSI J. Mechanisms of HBV-induced hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Hepatol, 2016, 64(1 Suppl): S84-S101. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.HASSAN M M, HWANG L Y, HATTEN C J, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma: synergism of alcohol with viral hepatitis and diabetes mellitus[J]. Hepatology, 2002, 36(5): 1206-1213. 10.1053/jhep.2002.36780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.YANG S, LIU Y, FENG X, et al. HBx acts as an oncogene and promotes the invasion and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma both in vivo and vitro [J]. Dig Liver Dis, 2021, 53(3): 360-366. 10.1016/j.dld.2020.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.KEKULÉ A S, LAUER U, WEISS L, et al. Hepatitis B virus transactivator HBx uses a tumour promoter signalling pathway[J]. Nature, 1993, 361(6414): 742-745. 10.1038/361742a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.SUN B, KARIN M. NF-kappaB signaling, liver disease and hepatoprotective agents[J]. Oncogene, 2008, 27(48): 6228-6244. 10.1038/onc.2008.300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ZHANG X D, WANG Y, YE L H. Hepatitis B virus X protein accelerates the development of hepatoma[J]. Cancer Biol Med, 2014, 11(3): 182-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.BOYAULT S, RICKMAN D S, DE REYNIÈS A, et al. Transcriptome classification of HCC is related to gene alterations and to new therapeutic targets[J]. Hepatology, 2007, 45(1): 42-52. 10.1002/hep.21467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.HOLLSTEIN M, SIDRANSKY D, VOGELSTEIN B, et al. p53 mutations in human cancers[J]. Science, 1991, 253(5015): 49-53. 10.1126/science.1905840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WANG X W, FORRESTER K, YEH H, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein inhibits p53 sequence-specific DNA binding, transcriptional activity, and association with transcription factor ERCC3[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1994, 91(6): 2230-2234. 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LEE S M, LEE Y G, BAE J B, et al. HBx induces hypomethylation of distal intragenic CpG islands required for active expression of developmental regulators[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014, 111(26): 9555-9560. 10.1073/pnas.1400604111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LEE S W, LEE Y M, BAE S K, et al. Human hepatitis B virus X protein is a possible mediator of hypoxia-induced angiogenesis in hepatocarcinogenesis[J]. Bio-chem Biophys Res Commun, 2000, 268(2): 456-461. 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.GUAN Y, LI W, HOU Z, et al. HBV suppresses expression of MICA/B on hepatoma cells through up-regulation of transcription factors GATA2 and GATA3 to escape from NK cell surveillance[J]. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(35): 56107-56119. 10.18632/oncotarget.11271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.STAIB F, HUSSAIN S P, HOFSETH L J, et al. TP53 and liver carcinogenesis[J]. Hum Mutat, 2003, 21(3): 201-216. 10.1002/humu.10176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LIU W, WU J, YANG F, et al. Genetic polymorphisms predisposing the interleukin 6-induced APOBEC3B-UNG imbalance increase HCC risk via promoting the generation of APOBEC-signature HBV mutations[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2019, 25(18): 5525-5536. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-18-3083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LIU W, JI H, ZHAO J, et al. Transcriptional repression and apoptosis influence the effect of APOBEC3A/3B functional polymorphisms on biliary tract cancer risk[J]. Int J Cancer, 2022, 150(11): 1825-1837. 10.1002/ijc.33930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CHEN P J, WU H L, WANG C J, et al. Molecular biology of hepatitis D virus: research and potential for application[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 1997, 12(9-10): S188-S192. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00500.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.CASEY J L. Hepatitis delta virus: molecular biology, pathogenesis and immunology[J]. Antivir Ther, 1998, 3(Suppl 3): 37-42. 10.1142/9781848160934_0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.RIZZETTO M. Hepatitis D virus: introduction and epidemiology[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2015, 5(7): a021576. 10.1101/cshperspect.a021576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.WEDEMEYER H, MANNS M P. Epidemiology, pathogenesis and management of hepatitis D: update and challenges ahead[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2010, 7(1): 31-40. 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.FATTOVICH G, STROFFOLINI T, ZAGNI I, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors[J]. Gastroenterology, 2004, 127(5 Suppl 1): S35-S50. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.CHOO Q L, KUO G, WEINER A J, et al. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome[J]. Science, 1989, 244(4902): 359-362. 10.1126/science.2523562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.YANG J, WANG D, LI Y, et al. Metabolomics in viral hepatitis: advances and review[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2023, 13: 1189417. 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1189417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.THOMAS D L, ASTEMBORSKI J, RAI R M, et al. The natural history of hepatitis C virus infection: host, viral, and environmental factors[J]. JAMA, 2000, 284(4): 450-456. 10.1001/jama.284.4.450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MOHD HANAFIAH K, GROEGER J, FLAXMAN A D, et al. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence[J]. Hepatology, 2013, 57(4): 1333-1342. 10.1002/hep.26141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.HOOFNAGLE J H. Hepatitis C: the clinical spectrum of disease[J]. Hepatology, 1997, 26(3 Suppl 1): 15S-20S. 10.1002/hep.510260703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.CASTELLO G, SCALA S, PALMIERI G, et al. HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma: from chronic inflam-mation to cancer[J]. Clin Immunol, 2010, 134(3): 237-250. 10.1016/j.clim.2009.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.JAIN D, CHAUDHARY P, VARSHNEY N, et al. Tobacco smoking and liver cancer risk: potential avenues for carcinogenesis[J]. J Oncol, 2021, 2021: 5905357. 10.1155/2021/5905357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.SZABO G, WANDS J R, EKEN A, et al. Alcohol and hepatitis C virus—interactions in immune dysfunctions and liver damage[J]. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2010, 34(10): 1675-1686. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01255.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.NEGRO F. Residual risk of liver disease after hepatitis C virus eradication[J]. J Hepatol, 2021, 74(4): 952-963. 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.SUN B, KARIN M. Obesity, inflammation, and liver cancer[J]. J Hepatol, 2012, 56(3): 704-713. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.STERLING R K, LISSEN E, CLUMECK N, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection[J]. Hepatology, 2006, 43(6): 1317-1325. 10.1002/hep.21178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.LI X D, SUN L, SETH R B, et al. Hepatitis C virus protease NS3/4A cleaves mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein off the mitochondria to evade innate immunity[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005, 102(49): 17717-17722. 10.1073/pnas.0508531102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DEWIDAR B, MEYER C, DOOLEY S, et al. TGF-β in hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrogenesis-updated 2019[J]. Cells, 2019, 8(11): 1419. 10.3390/cells8111419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.AGRATI C, NISII C, OLIVA A, et al. Lymphocyte distribution and intrahepatic compartmentalization during HCV infection: a main role for MHC-unrestricted T cells[J]. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz), 2002, 50(5): 307-316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MIROUX C, VAUSSELIN T, DELHEM N. Regulatory T cells in HBV and HCV liver diseases: implication of regulatory T lymphocytes in the control of immune response[J]. Expert Opin Biol Ther, 2010, 10(11): 1563-1572. 10.1517/14712598.2010.529125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.TSENG C T, KLIMPEL G R. Binding of the hepatitis C virus envelope protein E2 to CD81 inhibits natural killer cell functions[J]. J Exp Med, 2002, 195(1): 43-49. 10.1084/jem.20011145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.ALVISI G, MADAN V, BARTENSCHLAGER R. Hepatitis C virus and host cell lipids: an intimate connection[J]. RNA Biol, 2011, 8(2): 258-269. 10.4161/rna.8.2.15011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.KASPRZAK A, ADAMEK A. Role of hepatitis C virus proteins (C, NS3, NS5A) in hepatic oncogenesis[J]. Hepatol Res, 2008, 38(1): 1-26. 10.1111/j.1872-034x.2007.00261.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.LEE M N, JUNG E Y, KWUN H J, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein represses the p21 promoter through inhibition of a TGF-beta pathway[J]. J Gen Virol, 2002, 83(Pt 9): 2145-2151. 10.1099/0022-1317-83-9-2145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.CHENG P L, CHANG M H, CHAO C H, et al. Hepatitis C viral proteins interact with Smad3 and differentially regulate TGF-beta/Smad3-mediated trans-criptional activation[J]. Oncogene, 2004, 23(47): 7821-7838. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.SIAVOSHIAN S, ABRAHAM J D, KIENY M P, et al. HCV core, NS3, NS5A and NS5B proteins modulate cell proliferation independently from p53 expression in hepatocarcinoma cell lines[J]. Arch Virol, 2004, 149(2): 323-336. 10.1007/s00705-003-0205-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.YAMANAKA T, KODAMA T, DOI T. Subcellular localization of HCV core protein regulates its ability for p53 activation and p21 suppression[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2002, 294(3): 528-534. 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00508-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.CHO J, BAEK W, YANG S, et al. HCV core protein modulates Rb pathway through pRb down-regulation and E2F-1 up-regulation[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2001, 1538(1): 59-66. 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00137-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.AFTAB A, AFZAL S, IDREES M, et al. p53 and rb promoter methylation in hepatitis C virus-related chronic hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Future Virology, 2021, 16(1): 15-25. 10.2217/fvl-2020-0154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.DENG L, CHEN M, TANAKA M, et al. HCV upre-gulates Bim through the ROS/JNK signalling pathway, leading to Bax-mediated apoptosis[J]. J Gen Virol, 2015, 96(9): 2670-2683. 10.1099/jgv.0.000221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.KRUPA R, CZARNY P, WIGNER P, et al. The relationship between single-nucleotide polymorphisms, the expression of DNA damage response genes, and hepatocellular carcinoma in a polish population[J]. DNA Cell Biol, 2017, 36(8): 693-708. 10.1089/dna.2017.3664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.GANESAN M, TIKHANOVICH I, VANGIMALLA S S, et al. Demethylase JMJD6 as a new regulator of interferon signaling: effects of HCV and ethanol meta-bolism[J]. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018, 5(2): 101-112. 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.LIU W B, WU J F, DU Y, et al. Cancer evolution-development: experience of hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocarcinogenesis[J/OL]. Curr Oncol, 2016, 23(1): e49-56. 10.3747/co.23.2836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.LIU W, DENG Y, LI Z, et al. Cancer evo-dev: a theory of inflammation-induced oncogenesis[J]. Front Immunol, 2021, 12: 768098. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.768098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.BALAYAN M S, FEDOROVA O E, MIKHAILOV M I, et al. Antibody to hepatitis E virus in HIV-infected individuals and AIDS patients[J]. J Viral Hepat, 1997, 4(4): 279-283. 10.1046/j.1365-2893.1997.00050.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.NELSON K E, KMUSH B, LABRIQUE A B. The epidemiology of hepatitis E virus infections in developed countries and among immunocompromised patients[J]. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther, 2011, 9(12): 1133-1148. 10.1586/eri.11.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.YIN X, KAN F. Hepatitis E virus infection and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis [J]. Cancer Epidemiol, 2023, 87: 102457. 10.1016/j.canep.2023.102457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]