Significance

A mechanistic understanding of many autoimmune and inflammatory diseases is currently lacking. Recent work has shown that cell-free DNA bound to biological microparticles is linked to systemic lupus erythematosus and related conditions. However, the heterogeneity and technical challenges associated with biological particles have hindered a mechanistic understanding of their role in this disease. We have created a model system of DNA–particles and used these particles to understand the cellular response to DNA–particle complexes. These findings are important for considering inflammation in response to DNA on particle surfaces and providing a model system for further study of the role of particles in immune-mediated disease.

Keywords: nanoscience, corona, autoimmune disease, DNA, inflammation

Abstract

Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases are highly complex, limiting treatment and the development of new therapies. Recent work has shown that cell-free DNA bound to biological microparticles is linked to systemic lupus erythematosus, a prototypic autoimmune disease. However, the heterogeneity and technical challenges associated with the study of biological particles have hindered a mechanistic understanding of their role. Our goal was to develop a well-controlled DNA–particle model system to understand how DNA–particle complexes affect cells. We first characterized the adsorption of DNA on the surface of polystyrene nanoparticles (200 nm and 2 µm) using transmission electron microscopy, dynamic light scattering, and colorimetric DNA concentration assays. We found that DNA adsorbed on the surface of nanoparticles was resistant to degradation by DNase 1. Macrophage cells incubated with the DNA–nanoparticle complexes had increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6). We probed two intracellular DNA sensing pathways, toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING), to determine how cells sense the DNA–nanoparticle complexes. We found that the cGAS-STING pathway is the primary route for the interaction between DNA–nanoparticles and macrophages. These studies provide a molecular and cellular-level understanding of DNA–nanoparticle–macrophage interactions. In addition, this work provides the mechanistic information necessary for future in vivo experiments to elucidate the role of DNA–particle interactions in autoimmune diseases, providing a unique experimental framework to develop novel therapeutic approaches.

DNA is a polymeric macromolecule conventionally localized in the nucleus and mitochondria of cells. Recent studies, however, have highlighted the importance of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) found in circulation (1–3). CfDNA in the bloodstream is generated as cells undergo apoptosis, necrosis, or other forms of cell death (1–5). CfDNA is also generated during the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps by a process known as NETosis (3, 5, 6). In addition to these cellular sources, cfDNA is produced during infection from bacteria or viruses (3, 7) CfDNA released by cells undergoing apoptosis is highly fragmented with an average size of 100 to 200 base pairs, corresponding to the length of nucleosomal DNA (3, 4, 8). CfDNA from necrotic cells has been reported to be longer, in the range of multiple kilo base pairs (3, 4, 8). CfDNA generally has a short half-life in circulation ranging from several minutes to hours (1, 4, 9). Much work on cfDNA has focused on its use as a marker for cancer (1, 10, 11). It is also used to identify chromosomal abnormalities during pregnancy (12–14). Recent work has shown that cfDNA also serves as a biomarker for autoimmune disease including rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and may play a direct role in pathogenesis (4, 8, 15).

While DNA in the blood is termed “cell-free,” a significant proportion (up to ~90%) is associated with exosomes (16), a class of extracellular vesicle (1, 6). Extracellular vesicles are classified by size, molecular composition, and presumed cellular origin (17–19). Microparticles are a class of extracellular vesicle that range from 100 nm to 1,000 nm in diameter (17, 20, 21). They are released by the outward blebbing from cells during apoptosis and during the activation of platelets (17, 20, 22). Similar to cfDNA, increased levels of microparticles in the blood have been linked to autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, and inflammatory bowel disease (21, 23).

In previous studies, our laboratory investigated the role of microparticles in the pathogenesis of SLE (24). SLE is a prototypic autoimmune disease that displays diverse systemic manifestations in association with the production of antibodies to nuclear molecules (15, 25, 26). A major class of pathogenic antibodies in SLE, anti-DNA antibodies, bind to microparticles (20, 24, 27). The ability of an antibody to bind suggests that at least some portion of DNA is present on the microparticle surface. In SLE patients, microparticles have significantly more antibody bound to their surface compared to those from healthy individuals, suggesting that DNA-coated microparticles may contribute the immune complexes that underlie immunological events in SLE (20, 21, 27–29).

Determining the role of DNA–microparticles in SLE, and possibly other autoimmune diseases, requires elucidating the mechanisms by which DNA–microparticle complexes affect cells. DNA adsorbed on a microparticle surface could activate novel cell surface receptors; cells could internalize the DNA–microparticles giving DNA access to endocytic or cytosolic nucleic acid sensors or alter the half-life of cfDNA in circulation by changing the ability of DNA-degrading enzymes to access the cfDNA. For example, macrophages treated with microparticles isolated from rheumatoid arthritis and SLE patients adopt a pro-inflammatory phenotype (30).

There are significant technical difficulties in studying these naturally occurring microparticles obtained from blood or tissue culture fluid. The microparticles are highly heterogeneous in terms of size and composition of DNA, RNA, and proteins, making isolation of well-defined samples difficult (3, 21). Despite exciting advances in the use of nanoparticle tracking analysis to characterize particles present in the plasma of SLE patients (31), these challenges have hindered mechanistic studies, providing a strong motivation for a well-controlled model system. The goal of this research was to create a model system of synthetic particles to characterize the interaction of DNA with particles and the cellular response to DNA–particle complexes. For this purpose, we used synthetic polystyrene nanoparticles (NPs) with well-controlled diameters (200 nm and 2 µm) with two different lengths of Escherichia coli DNA (short DNAS ~500 to 800 base pairs, long DNAL ~10,000 base pairs) adsorbed on the NP surface. These NP diameters represent the extremes of the range of microparticle diameters (100 nm to 1,000 nm) (17, 18, 22). The lengths of DNA were chosen to mimic the small fragments of cfDNA that serve as autoimmune disease biomarkers (~100 to 200 bps) and the larger DNA fragments that are released during necrosis (>1,000 bps) (3, 4, 8) E. coli DNA has a known immunostimulatory effect that allows a focus on particle-dependent responses (32–36). Our previous work has shown that DNA adsorbs electrostatically on the surface of polystyrene NPs forming a “DNA corona,” (37) analogous to the “protein corona” formed on the surface of NPs in biological environments (38–44). Macrophages (RAW 264.7 and THP-1) were selected for cellular studies due to their previous use in evaluating the cellular response to nanomaterials (45, 46). The majority of our experiments used murine macrophages (RAW 264.7).

In this work, we first characterize the adsorption of DNA on the surface of polystyrene NPs using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), dynamic light scattering (DLS), and colorimetric DNA concentration assays. We examined the effect of DNase 1 activity on surface-adsorbed DNA. We then measured the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) by macrophage cells in response to these DNA–NP complexes. We probed two intracellular DNA sensing pathways, toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) to determine how cells respond to the DNA–NP complexes. We find that the cGAS-STING pathway is the primary sensing system for the stimulation of macrophages by DNA–NPs. These studies provide a molecular and cellular-level understanding of DNA–NP–macrophage interactions. In addition, this work provides the mechanistic information necessary for future in vivo experiments that will elucidate the role of DNA–particle interactions in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, providing a unique experimental framework to develop novel therapeutic approaches.

Results and Discussion

DNA Forms a Corona on NPs.

To create model DNA–particles with surface-adsorbed DNA, NPs were incubated with either short (sheared) DNA [DNAS, ~500 to 800 base pairs (bps)] or long (unsheared) DNA (DNAL, ~10,000 bps) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1A). For the 200 nm NPs (NP200 nm), TEM images and DLS show significant aggregation with the addition of the DNA corona (Fig. 1 B and C). The DLS measurements show a significant increase in hydrodynamic diameter from 198 ± 3 nm for NP200 nm to 2,735 ± 283 nm for DNAS–NP200 nm and 45,633 ± 2,746 nm for DNAL–NP200 nm (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of NPs and the DNA corona. (A) Preparation of DNA coronas. The structure of the DNA on the NP surface is not known. This schematic is only illustrative. (B) TEM images of NPs with and without DNA coronas comparing short (DNAS, sheared) and long (DNAL, unsheared) DNA. (C) Hydrodynamic diameter (left y axis) and polydispersity index (PDI; right y axis) of NPs with DNAS and DNAL coronas. Significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison post hoc. (D) Concentration of DNAS and DNAL adsorbed on the surface of NPs. The NP concentration was normalized to 500 pM to allow for comparison between NP diameters. Error bars reflect ±1 SD. Significance was determined using unpaired t tests. ****P < 0.0001, ns = not significant. n = 3 distinct samples.

We did not observe the same aggregation of DNA–NP2 µm by TEM or DLS (Fig. 1 B and C). We observed a slight increase in the hydrodynamic diameter of the 2 µm NPs from 1,982 ± 93 nm to 2,562 ± 81 nm and 3,269 ± 267 nm with DNAS and DNAL coronas, respectively. The average length of DNA strands is estimated to be 0.34 nm per base pair (47). Based on this number, we estimate the average length of DNAS to be 170 to 272 nm, and DNAL to be ~3,400 nm. For the NP200 nm, the DNAL is an order of magnitude longer than the diameter of the NPs which results in aggregates when a DNA corona is present. We did not observe any aggregation of the NP2 µm, (Fig. 1 B and C). The NP200 nm aggregate when they have a DNAS corona even though the DNA is on the same size scale as the NPs (Fig. 1 B and C).

We next measured the concentration of DNA present on the NP surface (Fig. 1D). NP200 nm had significantly more DNAS (14.9 ± 0.3 µg) than DNAL (6.9 ± 0.4 µg) adsorbed on the surface (Fig. 1D). We observed no significant difference between the amount of DNAS (2,219 ± 405 µg) and DNAL (2,664 ± 117 µg) on the surface of NP2 µm (Fig. 1D).

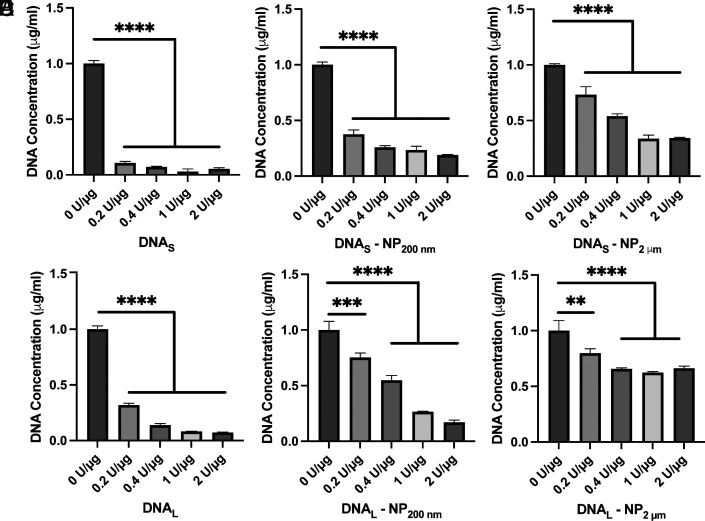

NPs Limit DNase 1 Digestion of DNA.

Studies of SLE have demonstrated that a deficiency of DNase enzymes contributes to pathogenesis by promoting autoreactivity (48–50). To further characterize the interaction of DNA with the NP surface, we treated DNA–NPs with increasing concentrations (0.2 U/µg to 2 U/µg) of DNase 1 (Fig. 2). Unbound DNA in solution was used as a control. As expected, DNAS and DNAL were nearly completely degraded in solution (Fig. 2 A and D). In comparison, the NPs limit the degradation of DNA present in the corona (Fig. 2 B, C, E, and F). This effect is especially pronounced for DNAL–NP2 µm (Fig. 2F). Even at the highest concentration of DNase (2 U/µg), there is only a 33% decrease in DNA concentration. Previous work has shown that DNA oligonucleotides conjugated with a thiol linker to gold NPs (13 nm) are also resistant to DNase 1 activity (51). Detailed studies of these NPs showed that a high local concentration of salts at the NP surface led to decreased enzymatic activity (51), suggesting a possible mechanism underlying our observation. Of note, our assays used the PicoGreen reagent, which detects DNA fragments ≥4 bps so all DNA considered degraded is at most 3 bps (52). Gel electrophoresis shows that, although the surface-bound DNA is not fully degraded by DNase 1 (Fig. 2), a substantial portion of DNA is degraded to fragments <50 bps in length (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Concentration of DNA present following treatment of DNA–NPs with DNase 1 (0.2 U/µg to 2 U/µg; 30 min, 37 °C). (A) DNAS (B) DNAS–NP200 nm (C) DNAS–NP2 µm (D) DNAL (E) DNAL–NP200 nm (F) DNAL–NP2 µm. Error bars reflect ±1 SD. Significance was measured using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, nonsignificant comparisons are not displayed. n = 3 distinct samples.

DNA–NPs Are Internalized by Macrophages.

To probe the interaction of DNA–NPs with macrophages (RAW 264.7), we incubated cells with NPs or DNA–NPs (24 h, 37 °C). We imaged the cells using TEM, as described in Materials and Methods. Since serum proteins used for cell culture can form a protein corona on DNA–NPs (37), we used Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium (Opti-MEM) with no serum added for all cellular experiments to avoid the formation of a protein corona (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

After a 24-hr incubation with macrophages, vacuoles are visible within the NP- and DNA–NP-treated cells (Fig. 3 A and B), similar to previous research examining the interaction of polystyrene NPs with liver cells (53). In comparison, untreated cells do not have vacuoles (Fig. 3 C, i). It is important to note that the TEM staining process does not stain the polystyrene NPs (Fig. 3 C, ii and iii). For the NP200 nm, we observed larger vacuoles when a DNA corona is present (Fig. 3A), corresponding to the DNA–NP200 nm aggregates observed by cell-free TEM and DLS (Fig. 1 B and C). For the NP2 µm, we do not see major differences in vacuole sizes for NP2 µm and DNA–NP2 µm (Fig. 3B), corresponding to the lack of aggregation for these NPs with the formation of DNA coronas (Fig. 1 B and C).

Fig. 3.

Representative TEM images of macrophages incubated with NPs and DNA–NPs (200 nm and 2 µm; 24 h at 37 °C). (A) Cells incubated with 200 nm NPs (bare) or DNAS and DNAL coronas. (B) Cells incubated with 2 µm NPs (bare) or DNAS and DNAL coronas. (C) i. Representative image of an untreated cell used as a control. ii, 200 nm NPs and iii, 2 µm NPs prepared and stained for TEM using the same embedding, staining, and microtoming method as used for the cells. We also observed internalization of NPs and DNA–NPs using confocal microscopy (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

DNA Corona Leads to Increased Cytokine Release.

To determine whether the DNA corona affects the stimulation of the cellular immune response, we measured cytokine release (TNF-α and IL-6) from macrophages (RAW 264.7) following incubation (24 h, 37 °C) with DNA–NPs (Fig. 4). Free DNA in the absence of NPs and NPs in the absence of DNA were used as controls. DNA concentrations (12 ng/mL to 3 µg/mL) were chosen to provide a broad range of responses. The amount of DNA on the DNA–NPs was used to match concentrations of free DNA and DNA–NPs for all experiments. TNF-α and IL-6 have both been found to be elevated in serum of patients with lupus and other inflammatory diseases (54, 55), motivating our choice of these cytokines for measurement. NPs (200 nm and 2 µm), in the absence of DNA, do not elicit TNF-α or IL-6 release (Fig. 4). DNAS and DNAL, in the absence of NPs, do lead to TNF-α release (Fig. 4 A and B). There was no significant difference in the response to DNAS or DNAL. Of note, there was no IL-6 release in response to free DNA (Fig. 4 C and D).

Fig. 4.

TNF-α and IL-6 release by macrophages incubated with DNA–NPs (24 h at 37 °C). (A) TNF-α release measured after incubation of cells with short (S; sheared) DNA (green filled circles), DNAS–NP200 nm (blue filled squares), and DNAS–NP2 μm (magenta filled triangles), and NPs in the absence of DNA (blue and magenta unfilled squares and triangles). (B) TNF-α release measured after incubation of cells with long (L; unsheared) DNA (green filled circles), DNAL–NP200 nm (blue filled squares), and DNAL–NP2 μm (magenta filled triangles), and NPs in the absence of DNA (blue and magenta unfilled squares and triangles). Similar results were observed with human macrophage-like cells (THP-1; SI Appendix, Fig. S5). (C) IL-6 release measured after incubation of cells with short (S; sheared) DNA (green filled circles), DNAS–NP200 nm (blue filled squares), and DNAS–NP2 μm (magenta filled triangles), and NPs in the absence of DNA (blue and magenta unfilled squares and triangles). (D) IL-6 release measured after incubation of cells with long (L; unsheared) DNA (green filled circles), DNAL–NP200 nm (blue filled squares), and DNAL–NP2 μm (magenta filled triangles), and NPs in the absence of DNA (blue and magenta unfilled squares and triangles). Error bars reflect ±1 SEM. Significance was measured using a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc. ****P < 0.0001, nonsignificant comparisons are not displayed. n = 3 distinct samples.

In comparison with these controls, DNA–NPs led to significantly greater production of both TNF-α and IL-6 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4). We found that the larger DNA–NPs led to a greater release of TNF-α and IL-6 for both the DNAS and DNAL across treatments, especially at lower DNA concentrations. We see a significant difference in the TNF-α release by cells treated with DNAS–NP200 nm vs. DNAL–NP200 nm, with DNAL–NPs having a higher cell response across most treatment concentrations (Fig. 4 A and B). This difference was not observed for DNAS and L–NP2 µm or DNAS and L alone.

We observed a large increase in TNF-α release by macrophage cells in response to DNA adsorbed on the surface of NPs (Fig. 4 A and B). The change in release of IL-6 was even greater, with no release in response to free DNA, but significant IL-6 release in response to DNA–NPs. To probe this result, we measured the cytokine release from cells with DNA and NPs added to cells separately, without a pre-formed corona (DNA + NP) (Fig. 5). When NPs and DNA were added to cells separately, there was an increase in TNF-α release in comparison to DNA alone for the DNAS and L+NP200 nm and 2 µm (Fig. 5 A and B). We see a significant increase in the TNF-α release for all treatments between DNA–NPs and DNA + NPs except for DNAS–NP200 nm vs. DNAS + NP200 nm. There was no IL-6 release in response to DNA and NPs added to cells separately (Fig. 5 C and D). A direct comparison of TNF-α in response to DNA–NPs and DNA+NPs shows that a pre-formed corona (DNA–NPs) increases cellular response (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

TNF-α and IL-6 release by macrophages incubated (24 h at 37 °C) with NPs and DNA added separately (DNA + NPs) to cells. (A) TNF-α release measured after incubation of cells with short (S; sheared) DNAS (green filled circles), DNAS + NP200 nm (blue filled squares), and DNAS + NP2 µm (magenta filled triangles). (B) TNF-α release measured after incubation of cells with long (L; unsheared) DNAL (green filled circles), DNAL + NP200 nm (blue filled squares) and DNAL + NP2 µm (magenta filled triangles). (C) IL-6 release measured after incubation of cells with DNAS (green filled circles), DNAS + NP200 nm (blue filled squares), and DNAS + NP2 µm (magenta filled triangles). (D) IL-6 release measured after incubation of cells with DNAL (green filled circles), DNAL + NP200 nm (blue filled squares), and DNAL + NP2 µm (magenta filled triangles). Error bars reflect ±1 SEM. Significance was measured using a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc. ****P < 0.0001, nonsignificant comparisons are not displayed. n = 3 distinct samples.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of TNF-α release by cells treated with DNA + NPs (3 µg/mL DNA) separately, DNA–NPs (3 µg/mL DNA), and DNA (3 µg/mL). Data is a repeat of Figs. 4 and 5. Error bars reflect ±1 SEM. Significance was measured using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns = not significant. n = 3 distinct samples.

To explore these results, we hypothesized that the increased cellular response to DNA–NPs compared to free DNA or DNA+NPs may be partially due to differences in degradation of DNA. To investigate the effect of DNA degradation on the cellular response, we added 2 U/µg or 5 U/µg of DNase 1 to cells incubated with DNA and DNA–NPs (Fig. 7 A and B). We found for DNAS and DNAL, the presence of 2 U/µg and 5 U/µg of DNase 1 significantly reduced the TNF-α response in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7 A and B). For the DNAS–NP200 nm, we observed a slight dose-dependent decrease in TNF-α release (Fig. 7A). For all other DNA–NPs (DNAL–NP200 nm, DNAS–NP2 μm, and DNAL–NP2 μm), there was no significant change in TNF-α release with DNase 1 present (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

TNF-α release by macrophages in response to DNA and DNA–NPs treated with DNase 1 (0 to 5 U/µg) (24 h at 37 °C). (A) DNAS and DNAS–NPs (1 µg/mL). (B) DNAL and DNAL–NPs (1 µg/mL). Error bars reflect ±1 SEM. Significance was measured using one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons post hoc. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns = not significant. n = 3 distinct samples.

This insensitivity of TNF-α release in response to DNase 1 suggests a correlation with the ability of the NPs to limit the DNase 1-mediated degradation of DNA on the surface of NPs (Fig. 2). DNA adsorbed on NP2 µm is the most resistant to DNase 1 degradation and results in the largest TNF-α release by cells (Figs. 2 C and F and 4 A and B). It is possible that NP-protected DNA leads to prolonged simulation of cells and the increased TNF-α release.

TNF-α Release in Response to DNA–NPs Is Independent of TLR9.

To probe the pathway by which DNA–NPs promotes cytokine release (Figs. 4–6), we measured cytokine release following inhibition of TLR9. TLR9 is an intercellular receptor stimulated by unmethylated CpG DNA (56). We used a TLR9 antagonist (ODN 2088) to determine whether TLR9 was a factor in the observed cytokine response. ODN 2088 is a 15 bp oligonucleotide that binds to TLR9 and blocks the activity of stimulatory DNA (57).

We compared TNF-α release for cells treated with DNA and DNA–NPs in the presence and absence of the ODN 2088 inhibitor (Fig. 8). Free DNA, in the absence of NPs, was used to determine a baseline for the response. For both DNAS and DNAL, the TLR9 inhibitor led to a significant decrease in the TNF-α release, as expected (Fig. 8) (57, 58). For DNA–NPs, we observed no decrease in TNF-α release for either DNAS or DNAL adsorbed on NP200 nm and NP2 µm (Fig. 8). This result suggests that DNA–NPs stimulate cells through a mechanism that does not depend on TLR9.

Fig. 8.

TNF-α release by macrophages incubated with free DNA (1 µg/mL) and DNA–NPs (1 µg/mL) in the presence of ODN 2088 (0.1 µM), a TLR9 inhibitor. (A) DNAS and DNAS–NPs. (B) DNAL and DNAL–NPs. Error bars reflect ±1 SEM. Significance was measured using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons post hoc. **P < 0.01, nonsignificant comparisons are not displayed. n = 3 distinct samples.

Inhibition of cGAS-STING Decreases TNF-α Release by Cells Treated with DNA–NPs.

In addition to TLR9, cells can respond to exogenous and endogenous DNA through the cGAS-STING pathway, which detects intracellular foreign and host DNA and plays a role in autoimmune disease (59–62). Activation of the cGAS-STING pathway has previously been used to confirm delivery of DNA into the cytoplasm by lipid-spherical nucleic acid NPs (63). To determine whether cGAS-STING mediates cytokine release stimulated by DNA–NPs (Fig. 4), we tested two separate inhibitors of the cGAS-STING pathway; a small-molecule cGAS inhibitor that binds to the cGAS protein (RU.521) and an irreversible small molecule STING inhibitor (H-151) that covalently binds to the STING protein. The use of RU.521 (10 µg/mL) led to almost complete inhibition of TNF-α release from cells incubated with DNA–NPs (Fig. 9 A and B). We observed this same effect for free DNAS and DNAL (Fig. 9 A and B). At a H-151 concentration of 5 µM, we saw a significant reduction in TNF-α release for both DNAS and DNAL adsorbed on 200 nm and 2 µm NPs (Fig. 9 C and D), as well as free DNAS and DNAL. The response to H-151 was concentration-dependent (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B). In combination with the results using the TLR9 inhibitor (Fig. 8), these findings suggest that DNA–NPs stimulate the cells through the cGAS-STING signaling cascade in a TLR9-independent process (Fig. 10). This is supported by cell confocal images (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), which show that DNA–NPs are not localized in the lysosomes. Other work has shown that exogenous DNA can lead to cross-sensing between the TLR9 and cGAS-STING pathways (64), which is supported by the observed decrease in TNF-α seen using both TLR-9 and cGAS-STING inhibitors (Figs. 8 and 9).

Fig. 9.

TNF-α release by macrophages incubated with free DNA (1 µg/mL) and DNA–NPs (1 µg/mL) (24 h at 37 °C) in the presence of cGAS-STING inhibitors [RU.521 (10 µg/mL) and H-151 (5 µM)]. The inhibitors were added to cells 24 h prior to the DNA or DNA–NPs and remained present during experiments. (A) DNAS and DNAS–NPs with RU.521. (B) DNAL and DNAL–NPs with RU.521. (C) DNAS and DNAS–NPs with H-151. (D) DNAL and DNAL–NPs with H-151. Error bars reflect ±1 SEM. Significance was measured using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons post hoc. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. n = 3 distinct samples.

Fig. 10.

Schematic representation of DNA and DNA–NPs stimulating cells via the cGAS-STING and TLR9 pathways. DNA can be internalized into endosomes and stimulate immune cells through a TLR9-dependent process or enter the cytosol and interact through a cGAS-STING-dependent pathway. Our data suggests that DNA–NPs, stimulate cells though a cGAS-STING-dependent pathway. The stimulation of cells results in the release of cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6.

In conclusion, the adsorption of DNA on a NP surface dramatically changes the biochemical and immunochemical properties of the adsorbed DNA including an increased immunostimulatory response in comparison to free DNA. The surface-adsorbed DNA is resistant to degradation by DNase 1 compared to free DNA in solution (Fig. 2). TEM and fluorescence microscopy show that DNA–NPs are internalized by macrophage cells (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Treatment of murine macrophage and human macrophage-like cells with DNA–NPs leads to increased TNF-α [Figs. 4–6 (murine) and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 (human)] and IL-6 (Figs. 4 and 5; murine) production. Since much of the DNA in the blood is associated with particles (16), these findings suggest that extracellular DNA may exert immunostimulatory activities beyond what would be expected by the measured concentration of DNA. TNF-α production is not altered by the presence of DNase 1 (Fig. 7), in agreement with the DNase 1 resistance observed in solution (Fig. 2). We evaluated two possible pathways by which the DNA–NPs could stimulate cells: TLR9 and cGAS-STING (Figs. 8–10). TLR9 inhibition had no effect on TNF-α production by cells treated with DNA–NPs (Fig. 8). In comparison, cGAS and STING inhibition significantly decreased TNF-α production (Fig. 9).

This current work establishes the immunostimulatory response of a well-studied murine macrophage cell line to DNA–NPs. Initial experiments in human macrophage-like cells point toward a similar response. Future work will extend these studies to patient plasma samples. This future work will include a protein corona (40, 42, 43, 65, 66), which has been shown to vary for even identical polystyrene NPs (67). Increasing biological complexity will introduce additional heterogeneity into this system. The current work using synthetic NPs, in the absence of a protein corona, provides a good model system, with NPs of standard diameter and composition, for future experiments with increasing complexity. Overall, these findings are important for considering the mechanisms of inflammation in response to DNA on particle surfaces and provide a model system for further study of autoimmune disease.

Materials and Methods

Nanoparticle (NP) Characterization.

Cationic, amine-modified, polystyrene NPs (0.2 µm and 2 µm, #37356 and #37366 Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) were used for all experiments. Prior to use, NP stock solutions were vortexed briefly and sonicated with a cup-horn sonicator (50 s ON/10 s OFF, 30% amplitude: Q500 Sonicator, Q Sonica Sonicators, Newtown, CT). The hydrodynamic diameter, polydispersity index, and zeta potential were measured using dynamic light scattering (DLS; Malvern Zetasizer, Nano-Z, Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, England). Measurements were carried out in triplicate (25 pM in water). Each measurement consisted of 30 runs. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Tecnai G2 TWIN, FEI, Hillsboro, OR) was also used to measure NP diameter. NPs (500 pM in water) were drop cast onto a carbon-coated grid (#FCF200-Cu, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and blotted with filter paper after 5 min. NPs were imaged at 160 kV. Particle size was determined using ImageJ/FIJI (68).

DNA Corona Formation and Characterization.

Our DNA corona formation method has been described previously (37). In brief, DNA coronas were formed by incubating NPs (500 pM) with E. coli DNA (0.25 mg/mL, #J14380, Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH), in Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS; pH 7.3-7.5, #28374, Thermo Fisher). The DNA and NPs were mixed by pipetting up and down and then incubated at room temperature (RT) for 45 min. Then, 1 µL of 1M hydrochloric acid was added to the 2 µm NPs when incubating with DNA to protonate the amine functional groups. Unbound DNA was removed by centrifugation (18,000 rcf) and resuspension in PBS (×3). Removal of unbound DNA using this washing process was confirmed previously (37). The resulting NPs with a DNA corona were characterized with DLS and TEM in the same way as the bare NPs, as described above. The concentration of DNA in the corona was measured using the PicoGreen DNA quantification assay (#P7589, Thermo Fisher), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fluorescence intensity (Ex: 480 nm, Em: 520 nm) was measured with a plate reader (SpectraMax iD3, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). The background signal from the bare NPs was subtracted from the overall signal.

DNA Degradation by DNase 1.

DNA–NPs were prepared in PBS containing magnesium and calcium (#14040133, Thermo Fisher), which are necessary for DNase 1 activity. DNase 1 (#4716728001, Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA) was added to solutions of DNA and DNA–NPs at increasing concentrations (0.2 U/µg of DNA, 0.4 U/µg, 1 U/µg and 2 U/µg) and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. DNase 1 was heat-inactivated by incubating the sample at 75 °C for 10 min before DNA concentration was quantified using the PicoGreen Assay.

Cell Culture.

A murine (male) macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7, ATCC, Manassas, VA) was used for the majority of experiments. RAW 264.7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; pH 7.4, #12100046, Thermo Fisher) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, #10437028, Thermo Fisher) at 5% CO2 at 37 °C. RAW 264.7 cells were passaged upon reaching 80% confluency with a maximum passage number of 20 after thawing from supplier stocks. The total passage number of RAW 264.7 cells is not known.

A human (male) monocyte cell line (THP-1, ATCC) was used to determine whether TNF-α release in response to DNA–NPs was similar for murine (RAW 264.7) and human (THP-1) cells. THP-1 cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 Medium (RPMI, #11875093, Thermo Fisher) supplemented with 10% FBS at 5% CO2 and 37 °C. THP-1 cells were passaged upon reaching a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL with a maximum passage number of 10 after thawing from supplier stocks. The total passage number for THP-1 cells is not known. The differentiation of THP-1 cells into adherent, macrophage-like cells is described in SI Appendix (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

FBS was removed from cells prior to NP incubations to avoid the formation of a protein corona.

TEM of NP Internalization.

DNA–NPs were prepared using the protocol described above. Cells were seeded onto six-well plates (Nunc 6-well multidishes, #140675, Thermo Fisher) and grown overnight. Cells were incubated with NPs and DNA–NPs (25 pM for 200 nm NPs and 0.06 pM for 2 µm NPs) for 24 h at 37 °C in Opti-MEM. Cells were rinsed (×3) in PBS and fixed in Karnovsky fixative overnight. Cells were rinsed (×3) in sodium cacodylate (#100504-840, VWR, Radnor, PA), scraped from the wells, and placed in eppendorf tubes. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min (1000 rcf). Samples were stained in a 1% solution of osmium tetroxide (#201030, Millipore Sigma) for 1 h and washed (×5) in PBS. Samples were dehydrated through a series of ethanol concentrations (50%, 70%, 90%, and 100%) for 5 min at each concentration. Samples were then embedded in an epoxy resin and sliced with a diamond knife. Samples were stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 30 min and imaged (Tecnai G2 TWIN, FEI) at the Hooker Imaging Core facility at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Control samples of NPs alone, in the absence of cells, were processed using an identical staining and imaging procedure.

Quantification of TNF-α and IL-6 Release.

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded onto sterile 96-well plates (#3595, Corning, Corning NY) at a density of 50,000 cells per well. The cells were cultured overnight and then incubated with DNA, NPs, or DNA–NP complexes. Experiments were carried out in triplicate. DNA treatments had a maximum DNA concentration of 3 µg/mL. Cell treatments were carried out in Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Media (#31985062, Thermo Fisher). After a 24-h incubation, the cell media was harvested and centrifuged at 3,000 rcf for 15 min to remove any cell debris. The supernatant was collected and stored at −20 °C. TNF-α and IL-6 release were measured using ELISAs according to the manufacturer’s instructions [Mouse TNF-α DuoSet ELISA (#DY410) and Mouse IL-6 DuoSet ELISA (#DY406), R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN]. Experimental details for the THP-1 cell experiments are provided in SI Appendix, Fig. S5.

Inhibition of TLR9 with ODN 2088.

Cells were seeded onto sterile 96-well plates as described above. The cells were cultured overnight in media containing ODN 2088 (1 µM, #tlrl-2088, InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) and then incubated with DNA or DNA–NP complexes. Experiments were carried out in triplicate. DNA treatments had a DNA concentration of 1 µg/mL. Cell treatments were carried out in Opti-MEM containing 1 µM ODN 2088. After a 24-h incubation, the cell media was harvested and centrifuged at 3,000 rcf for 15 min to remove any cell debris. The supernatant was collected and stored at −20 °C until the ELISA was conducted.

Inhibition of cGAS-STING with RU 521 and H-151.

Cells were seeded onto sterile 96-well plates as described above. The cells were cultured overnight in media containing various concentrations of RU 521 (0.2 µg/mL, 1 µg/mL, 2 µg/mL, and 10 µg/mL, #inh-ru521, InvivoGen) or H-151 (0.5 µM, 1 µM, 5 µM, and 10 µM, #inh-h 151, InvivoGen) and then incubated with DNA or DNA–NP complexes. Experiments were carried out in triplicate. DNA treatments had a DNA concentration of 1 µg/mL. Cell treatments were carried out in Opti-MEM containing respective concentrations of RU 521 and H-151. After a 24-h incubation, the cell media was harvested and centrifuged at 3,000 rcf for 15 min to remove any cell debris. The supernatant was collected and stored at −20 °C until the ELISA was conducted.

Statistical Analysis.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or mean ± SEM as noted in the text. The statistical significance of the data was measured using one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA with post hoc tests detailed in each figure caption. All data were analyzed using commercially available software (GraphPad Prism 10, San Diego, CA).

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Grant 1R21-AI175926. We thank Diane Spencer and Dr. Nathan Rayens for assistance with experiments. A portion of this work was performed in part at the Duke University Shared Materials Instrumentation Facility (SMIF), a member of the North Carolina Research Triangle Nanotechnology Network (RTNN), which is supported by the NSF (award number ECCS-2025064) as part of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI). Cellular transmission electron microscopy was performed at the UNC Hooker Imaging Core Facility, supported in part by P30 CA016086 Cancer Center Core Support Grant to the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. Fig. 1A was created with Biorender.com. Fig. 10 is adapted from the Biorender template “cGAS-STING DNA Detection” (2023).

Author contributions

F.A., D.A.M., D.S.P., and C.K.P. designed research; F.A. and D.A.M. performed research; F.A. and D.A.M. analyzed data; and F.A., D.S.P., and C.K.P. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Kustanovich A., Schwartz R., Peretz T., Grinshpun A., Life and death of circulating cell-free DNA. Cancer Biol. Ther. 20, 1057–1067 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pisetsky D. S., The origin and properties of extracellular DNA: From PAMP to DAMP. Clin. Immunol. 144, 32–40 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aucamp J., Bronkhorst A. J., Badenhorst C. P. S., Pretorius P. J., The diverse origins of circulating cell-free DNA in the human body: A critical re-evaluation of the literature. Biol. Rev. 93, 1649–1683 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mondelo-Macía P., Castro-Santos P., Castillo-García A., Muinelo-Romay L., Diaz-Peña R., Circulating free DNA and its emerging role in autoimmune diseases. J. Pers. Med. 11, 151 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murao A., Aziz M., Wang H., Brenner M., Wang P., Release mechanisms of major DAMPs. Apoptosis 26, 152–162 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grabuschnig S., et al. , Putative origins of cell-free DNA in humans: A review of active and passive nucleic acid release mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 8062 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleischhacker M., Schmidt B., Circulating nucleic acids (CNAs) and cancer—A survey. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1775, 181–232 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duvvuri B., Lood C., Cell-free DNA as a biomarker in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Front. Immunol. 10, 502 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Celec P., Vlková B., Lauková L., Bábíčková J., Boor P., Cell-free DNA: The role in pathophysiology and as a biomarker in kidney diseases. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 20, e1 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volik S., Alcaide M., Morin R. D., Collins C., Cell-free DNA (cfDNA): Clinical significance and utility in cancer shaped by emerging technologies. Mol. Cancer Res. 14, 898–908 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz L. A., Bardelli A., Liquid biopsies: Genotyping circulating tumor DNA. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 579–586 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bianchi D. W., Chiu R. W. K., Sequencing of circulating cell-free DNA during pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 464–473 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gil M. M., et al. , Screening for trisomies by cfDNA testing of maternal blood in twin pregnancy: Update of The Fetal Medicine Foundation results and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 53, 734–742 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mennuti M. T., Chandrasekaran S., Khalek N., Dugoff L., Cell-free DNA screening and sex chromosome aneuploidies. Prenat. Diagn. 35, 980–985 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soni C., Reizis B., Self-DNA at the epicenter of SLE: Immunogenic forms, regulation, and effects. Front. Immunol. 10, 1601 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernando M. R., Jiang C., Krzyzanowski G. D., Ryan W. L., New evidence that a large proportion of human blood plasma cell-free DNA is localized in exosomes. PLoS One 12, e0183915 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doyle L. M., Wang M. Z., Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells 8, 727 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szatanek R., et al. , The methods of choice for extracellular vesicles (EVs) characterization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1153 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alberro A., Iparraguirre L., Fernandes A., Otaegui D., Extracellular vesicles in blood: Sources, effects, and applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 8163 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mobarrez F., Svenungsson E., Pisetsky D. S., Microparticles as autoantigens in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 48, e13010 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rother N., Yanginlar C., Pieterse E., Hilbrands L., Van Der Vlag J., Microparticles in autoimmunity: Cause or consequence of disease? Front. Immunol. 13, 822995 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raposo G., Stoorvogel W., Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 200, 373–383 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turpin D., et al. , Role of extracellular vesicles in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 15, 174–183 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mobarrez F., et al. , Microparticles in the blood of patients with SLE: Size, content of mitochondria and role in circulating immune complexes. J. Autoimmun. 102, 142–149 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pisetsky D. S., Anti-DNA antibodies—Quintessential biomarkers of SLE. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 12, 102–110 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaul A., et al. , Systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2, 1–21 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pisetsky D. S., Lipsky P. E., New insights into the role of antinuclear antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 16, 565–579 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X., Wang Q., Platelet-derived microparticles and autoimmune diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 10275 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartl J., et al. , Autoantibody-mediated impairment of DNASE1L3 activity in sporadic systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Exp. Med. 218, e20201138 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burbano C., et al. , Proinflammatory differentiation of macrophages through microparticles that form immune complexes leads to T- and B-cell activation in systemic autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 10, 2058 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juul-Madsen K., et al. , Characterization of DNA–protein complexes by nanoparticle tracking analysis and their association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2106647118 (2023), 10.1073/pnas.2106647118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pisetsky D. S., Immune activation by bacterial DNA: A new genetic code. Immunity 5, 303–310 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wloch M. K., Pasquini S., Ertl H. C. J., Pisetsky D. S., The influence of DNA sequence on the immunostimulatory properties of plasmid DNA vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 9, 1439–1447 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neujahr D. C., Reich C. F., Pisetsky D. S., Immunostimulatory properties of genomic DNA from different bacterial species. Immunobiology 200, 106–119 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krieg A. M., CpG motifs in bacterial DNA and their immune effects. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20, 709–760 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipford G. B., Heeg K., Wagner H., Bacterial DNA as immune cell activator. Trends Microbiol. 6, 496–500 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffith D. M., Jayaram D. T., Spencer D. M., Pisetsky D. S., Payne C. K., DNA-nanoparticle interactions: Formation of a DNA corona and its effects on a protein corona. Biointerphases 15, 051006 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ke P. C., Lin S., Parak W. J., Davis T. P., Caruso F., A decade of the protein Corona. ACS Nano 11, 11773–11776 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleischer C. C., Payne C. K., Nanoparticle-cell interactions: Molecular structure of the protein corona and cellular outcomes. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 2651–2659 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Payne C. K., A protein corona primer for physical chemists. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 130901 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lynch I., et al. , The nanoparticle–protein complex as a biological entity; a complex fluids and surface science challenge for the 21st century. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 134–135, 167–174 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walczyk D., Bombelli F. B., Monopoli M. P., Lynch I., Dawson K. A., What the cell “sees” in bionanoscience. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5761–5768 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomak A., Cesmeli S., Hanoglu B. D., Winkler D., Oksel Karakus C., Nanoparticle-protein corona complex: Understanding multiple interactions between environmental factors, corona formation, and biological activity. Nanotoxicology 15, 1331–1357 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monopoli M. P., Åberg C., Salvati A., Dawson K. A., Biomolecular coronas provide the biological identity of nanosized materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 779–786 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Figueiredo Borgognoni C., Kim J. H., Zucolotto V., Fuchs H., Riehemann K., Human macrophage responses to metal-oxide nanoparticles: A review. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 46, 694–703 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin H., Song Z., Bianco A., How macrophages respond to two-dimensional materials: A critical overview focusing on toxicity. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 56, 333–356 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson J. D., Crick F. H. C., Molecular structure of nucleic acids: A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature 171, 737–738 (1953). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martínez Valle F., Balada E., Ordi-Ros J., Vilardell-Tarres M., DNase 1 and systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun. Rev. 7, 359–363 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kenny E. F., Raupach B., Abu Abed U., Brinkmann V., Zychlinsky A., Dnase1-deficient mice spontaneously develop a systemic lupus erythematosus-like disease. Eur. J. Immunol. 49, 590–599 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Mayouf S. M., et al. , Loss-of-function variant in DNASE1L3 causes a familial form of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Genet. 43, 1186–1188 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seferos D. S., Prigodich A. E., Giljohann D. A., Patel P. C., Mirkin C. A., Polyvalent DNA nanoparticle conjugates stabilize nucleic acids. Nano Lett. 9, 308–311 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dragan A. I., et al. , Characterization of picogreen interaction with dsDNA and the origin of its fluorescence enhancement upon binding. Biophys. J. 99, 3010–3019 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szule J. A., et al. , Early enteric and hepatic responses to ingestion of polystyrene nanospheres from water in C57BL/6 mice. Front. Water 4, 925781 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yap D. Y. H., Lai K. N., Cytokines and their roles in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus: From basics to recent advances. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 1–10 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lourenço E. V., Cava A. L., Cytokines in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Curr. Mol. Med. 9, 242–254 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumagai Y., Takeuchi O., Akira S., TLR9 as a key receptor for the recognition of DNA. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 60, 795–804 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Almarhoumi R., et al. , Microglial cell response to experimental periodontal disease. J. Neuroinflammation 20, 142 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seebach E., Kraus F. V., Elschner T., Kubatzky K. F., Staphylococci planktonic and biofilm environments differentially affect osteoclast formation. Inflamm. Res. 72, 1465–1484 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Motwani M., Pesiridis S., Fitzgerald K. A., DNA sensing by the cGAS–STING pathway in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 657–674 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen Q., Sun L., Chen Z. J., Regulation and function of the cGAS–STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. Nat. Immunol. 17, 1142–1149 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wan D., Jiang W., Hao J., Research advances in how the cGAS-STING pathway controls the cellular inflammatory response. Front. Immunol. 11, 615 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Skopelja-Gardner S., An J., Elkon K. B., Role of the cGAS–STING pathway in systemic and organ-specific diseases. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18, 558–572 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sinegra A. J., Evangelopoulos M., Park J., Huang Z., Mirkin C. A., Lipid nanoparticle spherical nucleic acids for intracellular DNA and RNA delivery. Nano Lett. 21, 6584–6591 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amadio R., Piperno G. M., Benvenuti F., Self-DNA sensing by cGAS-STING and TLR9 in autoimmunity: Is the cytoskeleton in control? Front. Immunol. 12, 657344 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ke P. C., et al. , Implications of peptide assemblies in amyloid diseases. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 6492–6531 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mahmoudi M., Landry M. P., Moore A., Coreas R., The protein corona from nanomedicine to environmental science. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 422–438 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sheibani S., et al. , Nanoscale characterization of the biomolecular corona by cryo-electron microscopy, cryo-electron tomography, and image simulation. Nat. Commun. 12, 573 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schindelin J., et al. , Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.