Significance

Women’s health is a dramatically underserved area of medicine. The resultant lack of therapeutic options for use during pregnancy contributes to over 75,000 maternal and 500,000 fetal/infant deaths each year. As such, there is an urgent need for new therapies that maintain safety in both the pregnant (Pr) person and their fetus. Here, we describe lipid nanoparticles, akin to those used in the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, that safely deliver mRNA to the placenta and nonreproductive organs in Pr people without harming the fetus. We also provide mechanistic insight as to how the physiological and immunological changes that occur during pregnancy alter nanoparticle behavior compared to nonpregnant people.

Keywords: mRNA delivery, lipid nanoparticles, LNPs, maternal health, fetal toxicity

Abstract

Treating pregnancy-related disorders is exceptionally challenging because the threat of maternal and/or fetal toxicity discourages the use of existing medications and hinders new drug development. One potential solution is the use of lipid nanoparticle (LNP) RNA therapies, given their proven efficacy, tolerability, and lack of fetal accumulation. Here, we describe LNPs for efficacious mRNA delivery to maternal organs in pregnant mice via several routes of administration. In the placenta, our lead LNP transfected trophoblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells, with efficacy being structurally dependent on the ionizable lipid polyamine headgroup. Next, we show that LNP-induced maternal inflammatory responses affect mRNA expression in the maternal compartment and hinder neonatal development. Specifically, pro-inflammatory LNP structures and routes of administration curtailed efficacy in maternal lymphoid organs in an IL-1β-dependent manner. Further, immunogenic LNPs provoked the infiltration of adaptive immune cells into the placenta and restricted pup growth after birth. Together, our results provide mechanism-based structural guidance on the design of potent LNPs for safe use during pregnancy.

Physiological and immunological changes during pregnancy can exacerbate preexisting maternal health conditions and induce emergent conditions, thus increasing the risk of maternal medical and obstetrical complications (1). Resultant adverse events on maternal and fetal health can be devastating. For example, the hypertensive disorder, preeclampsia, affects 5 to 10% of pregnancies and causes over 75,000 maternal and 500,000 infant deaths each year (2). Additionally, pregnant (Pr) people with SARS-CoV-2 infection are twice as likely to need intensive care, ventilation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation compared to nonpregnant (NP) people (3).

Although hypertension, infections, and other conditions are often manageable in NP people, they can be life-threatening during pregnancy because relevant drugs have not been proven safe. Safety data are scarce because Pr people are commonly excluded from clinical trials (4). As of 2022, international clinical trial registries report that Pr people were included in a mere 0.15% of registered clinical trials (5). Because safety data are lacking, many commonly used drugs, including the analgesic ibuprofen, antidepressants (e.g., lorazepam), and antibiotics (e.g., ciprofloxacin), are contraindicated during pregnancy (6). Additionally, several drugs, such as the blood thinner warfarin and the antimalarial primaquine, are restricted because of off-target fetal toxicity (6). These small-molecule drugs rapidly cross the placental barrier and may impair fetal development.

One possible solution to these challenges is RNA therapy, which may improve safety in several ways. First, because they address protein dysregulation at the genetic level, they offer higher specificity than small-molecule drugs, which must interface with preexisting proteins (7). Further, their large lipid nanoparticle (LNP) packaging (~100 nm) may restrict transplacental transport (8). These LNPs are also degradable and biocompatible and rapidly clear from the bloodstream without long-term accumulation (9, 10). Additionally, they efficiently encapsulate 20- to 10,000-base-pair-long RNA modalities, including small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA) (10, 11), messenger Ribonucleic acid (mRNA) (12), self-amplifying RNA (13), circular RNA (14), Cas9 nucleases (15), and others, and deliver RNA cargos to intended cellular targets with high efficacy.

Indeed, clinical trial data suggest that the mRNA-LNP-based severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from Moderna and Pfizer–BioNTech have excellent efficacy and safety profiles in Pr people (16). Compared to unvaccinated individuals, mRNA vaccines reduced the risk of severe COVID-19 illness in Pr individuals (17) and the risk of COVID-19 hospital admission among their infants younger than 6 mo of age (18). Moreover, vaccination did not increase the risk of pregnancy-related complications, including maternal death, stillbirth, preterm birth, and postpartum hemorrhage (19).

These promising results have propelled researchers to evaluate existing and new LNP structures for placenta-specific delivery for maternal disorders (20–22). However, a better understanding of several fundamental LNP delivery processes during pregnancy is needed for clinical translation of these new therapies. Specifically, it is unclear how the state of pregnancy alters LNP biodistribution, efficacy, immunogenicity, and maternal-fetal toxicity. Equally mysterious is the effect of LNP chemistry on these same processes as well as on transplacental transport and pup/infant outcomes. To address these knowledge gaps, we examined an LNP library for mRNA delivery to Pr mice and identified particles that transfected exclusively maternal cells without fetal accumulation. Biological outcomes were structure-dependent, and immunostimulation altered LNP organ tropism and inhibited pup development. Together, these experiments establish how the state of pregnancy alters LNP behavior, identify potent LNPs for use during pregnancy, and establish criteria for next-generation LNP design.

Results

LNP Chemistry Dictates RNA Delivery Efficacy and Toxicity.

To design LNPs that deliver mRNA to the placenta, we first assessed the efficacy of an LNP library in a human choriocarcinoma cell line called BeWo b30 cells. These cells express critical differentiation markers (23) that model the placental trophoblast barrier that separates maternal and fetal blood circulations. BeWo b30 cells are a good choice to study the uptake (24), transport (25), and efflux (26) of drugs across placental trophoblasts in vitro.

Our library contained 260 LNPs formulated using ionizable lipids synthesized combinatorically from 20 amine heads and 13 acrylate tails (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). To test efficacy, we encapsulated mRNA encoding firefly luciferase (mLuc) in LNPs and added them to BeWo b30 cells. The predominant determinant of mRNA delivery potency was the ionizable lipid headgroup, with amines 306, 500, 514, and 516 producing the most protein expression (Fig. 1A).

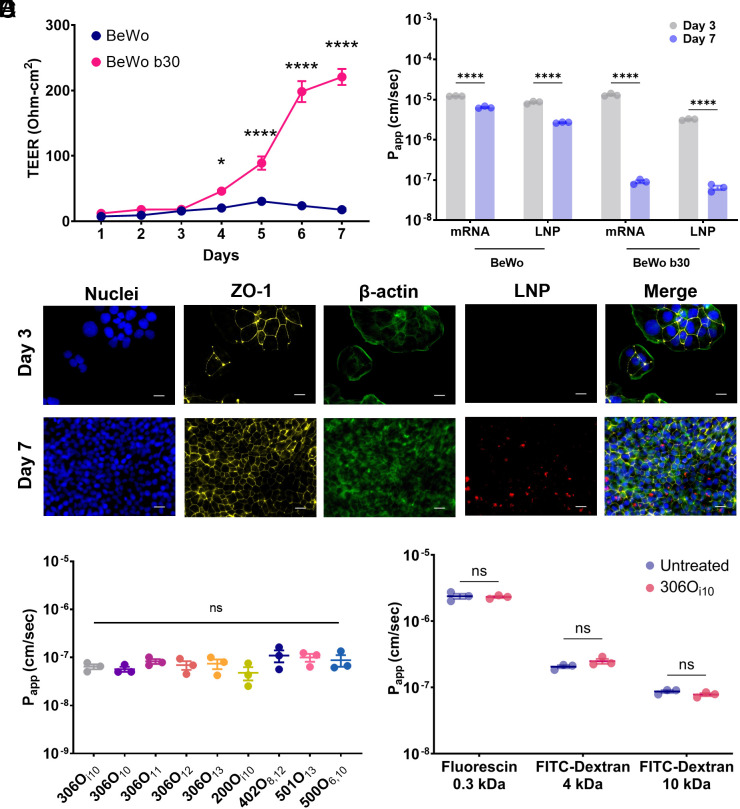

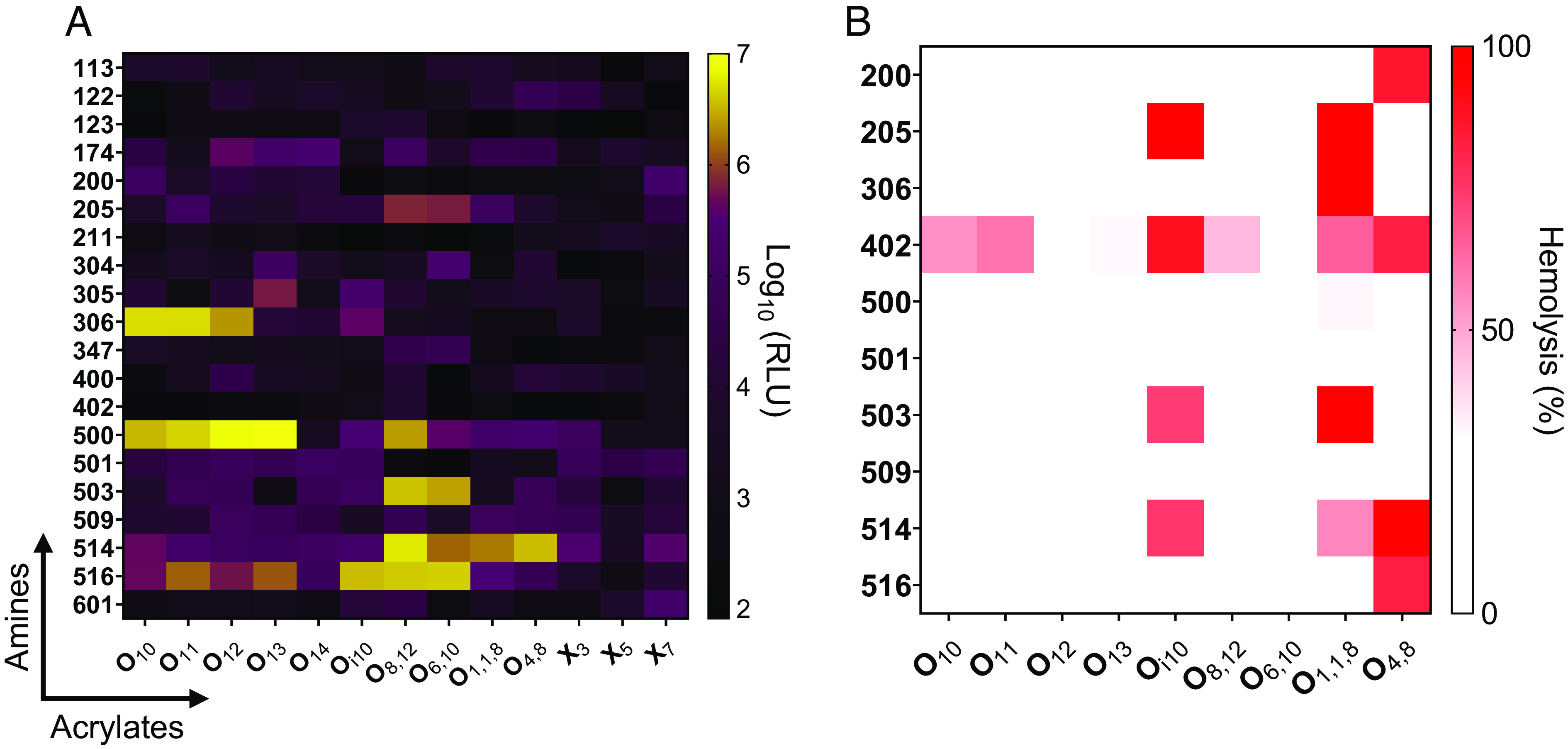

Fig. 1.

Ionizable lipid structure influences mRNA delivery in human placental trophoblasts in vitro. (A) A total of 260 ionizable lipids generated from 20 amine headgroups (y-axis) and 13 alkyl acrylate tails (x-axis) were formulated into mLuc-LNPs. Particles were incubated with placental cells for 24 h, and luminescence intensity was quantified, with brighter colors indicating better transfection. (B) Nanoparticle-induced hemolysis of human red blood cells was measured as a proxy for toxicity in the bloodstream. Cells were incubated with LNPs for 1.5 h, and hemolysis was assessed by measuring absorbance in the supernatant. In both panels, heat map colors represent median values (n = 4).

Next, we assessed toxicity with a lysis assay to rule out LNPs that destroy red blood cells. In this assay, toxic LNPs burst red blood cells at physiological pH and release the chromogenic heme complex into the supernatant, which is quantified using a spectrophotometer. We found that most LNPs did not lyse red blood cells (Fig. 1B). Hemolytic activity was structure dependent, with hemolysis induced by LNPs containing the 402 amine head group or Oi10, O1,1,8, and O4,8 tails (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, these branched tails were more likely to induce hemolysis than their linear tail counterparts (e.g., O10 and O11). To minimize safety concerns, we eliminated hemolytic LNPs from in vivo studies.

LNPs Do Not Penetrate the Trophoblast Barrier In Vitro.

Next, we gauged whether viable LNPs penetrate the trophoblast barrier. For this, we cultured BeWo b30 cells on semipermeable Transwell™ inserts until they fused together and formed a “syncytialized” trophoblast barrier (27, 28). Monolayer development was monitored over 7 d by transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER), with TEER >100 Ohm cm2 suggesting successful barrier formation in BeWo b30 cells (25) (Fig. 2A). In addition to the b30 clones, we used nonfusogenic parental BeWo cells as a negative control (28). As expected, TEER increased only for syncytium-forming BeWo b30 cells.

Fig. 2.

The placental barrier inhibits LNP transport in vitro. (A) TEER measurements confirmed that, when grown on Transwell plates, BeWo b30 clone cells formed a trophoblastic monolayer, whereas parent BeWo cells did not (n = 12). (B) Apparent permeability (Papp) was assessed for naked and LNP-encapsulated Cy5-labeled mRNA across BeWo and BeWo b30 monolayers on days 3 and 7. Fully formed BeWo b30 monolayers inhibited naked and encapsulated mRNA transport (n = 3). (C) Nanoparticle uptake by BeWo b30 monolayers was imaged using immunofluorescence microscopy: DAPI (blue); anti-ZO-1 antibody (yellow); Phalloidin (green); Cy5-tagged mRNA (red). (Scale bars, 20 μm.) (D) On day 7 of monolayer development, LNP Papp was not affected by ionizable lipid chemistry (n = 3). (E) Papp of 0.3-, 4-, and 10-kDa fluorescent marker molecules was measured in the presence or absence of 306Oi10 LNPs, which showed that LNPs did not enhance permeability (n = 3). Error bars represent SEM. ns, *, and **** represent nonsignificant, P < 0.05, and P < 0.0001, respectively, according to two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s post hoc analysis (A, B, and E) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis (D).

To test barrier function, we quantified transport kinetics by measuring the apparent permeability (Papp) of Cy5-labeled naked mRNA or mRNA-LNPs in BeWo and BeWo b30 cells. For this, we chose 306Oi10 LNPs because they are not hemolytic (Fig. 1B) and have been previously shown to be exceptionally potent in vivo (15, 29). We observed that parental BeWo cells reduced Papp by ~twofold for naked mRNA and ~fivefold for 306Oi10 LNPs between days 3 and 7 (Fig. 2B). In comparison, syncytialized BeWo b30 cells reduced mRNA and LNP transport by ~136-fold and ~192-fold, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Fluorescence microscopy revealed that BeWo b30 cells developed a confluent cell network by day 7. Compared to day 3, the monolayers robustly expressed the barrier-forming tight junction protein zonula occludens-1 (30) and took up LNPs to a greater degree (Fig. 2C). This suggests that the syncytialized BeWo b30 “catch” LNPs, preventing them from diffusing between the cells. Further, we observed that BeWo b30 cells inhibited transport regardless of the LNP structure, with nine LNPs showing no statistical differences in transport rate (Fig. 2D).

In addition to restricting fetal exposure to pathogen and foreign substances, the trophoblast barrier facilitates the exchange of molecules of varied size, ranging from small-molecule nutrients such as glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids (31) to macromolecular peptides and proteins (32). For healthy fetal development, LNPs must not hinder the flow of such molecules. To examine this, we exposed BeWo b30 cells to several marker molecules, including 300-Da fluorescein and 4- and 10-kDa FITC-Dextran. Fortunately, 306Oi10 did not alter the transport kinetics of any marker molecule (Fig. 2E). Together, these data show that LNPs do not penetrate the trophoblast barrier or hinder transport of other small- or macro-molecules in vitro.

The State of the Immune System Affects LNP Tropism in Pr Mice.

Having shown safe mRNA delivery in vitro, we asked whether LNP behavior extended in vivo. For this, we formulated 306Oi10 LNPs with mRNA and injected them intravenously (IV) in CD-1 mice on day 14 of pregnancy. Mice gestate on average for 19 to 21 d, and the placenta is functional by day 12.5 (33, 34). Therefore, day 14 corresponds to the early phases of the second trimester in human pregnancy (35). First, we assessed LNP biodistribution using Cy5-labeled mRNA. We observed that 306Oi10 LNPs distributed to the placenta and liver (Fig. 3 A and C) without increased fetal accumulation compared to naked mRNA (Fig. 3B). Further, we observed dose-dependent luciferase expression in the placenta using mLuc-LNPs (Fig. 3 D and F), with no observable signal in the fetus (Fig. 3 E and F). Among nonreproductive organs, luciferase was expressed to the greatest extent in the liver and spleen (Fig. 3G and SI Appendix, Fig. S2), and there were no shifts in organ tropism between age-matched NP and Pr mice at any dose (Fig. 3G).

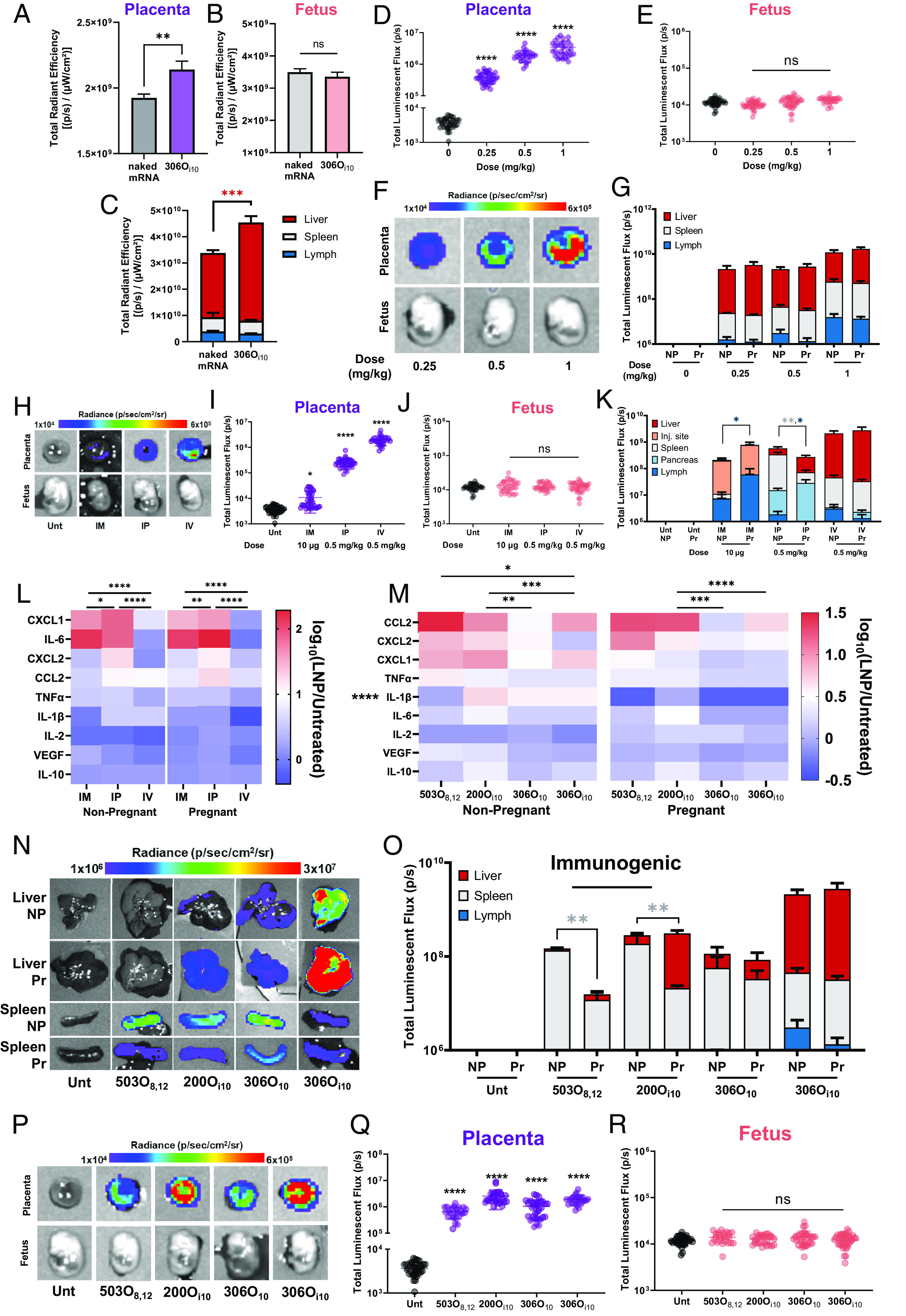

Fig. 3.

LNPs deliver mRNA to the placenta without delivery to the fetus. To examine biodistribution, 306Oi10 LNPs containing Cy5-labeled mRNA were IV-injected in Pr CD-1 mice (control = naked Cy5 mRNA) on the 14th day of pregnancy. Four hours later, mice were killed and biodistribution in (A) the placenta, (B) fetus, and (C) nonreproductive organs was measured using in vivo imaging system (IVIS). To examine efficacy, 306Oi10 LNPs encapsulating mLuc were IV-injected in NP or Pr CD-1 mice. Four hours later, mice were killed, and luminescence was quantified by IVIS in (D–F) the placenta and fetus and (G) nonreproductive organs. To examine the route of delivery, 306Oi10 mLuc-LNPs were injected IM (10 μg), intraperitoneally (IP, 0.5 mg/kg), or IV (0.5 mg/kg) in NP or Pr CD-1 mice. (H–J) Four hours later, luminescence was quantified in the placenta and fetus for Pr mice and in (K) nonreproductive organs for Pr and NP mice. (L and M) Serum cytokines and chemokines were measured, with red and blue representing high and low expression, respectively. (N and O) For two immunogenic LNPs (503O8,12 and 200Oi10) and two immunoquiescent LNPs (306O10 and 306Oi10), efficacy following IV administration was measured in nonreproductive organs as well as in (P–R) the placenta and fetus. Heatmap colors in panels E and K correspond to median values. Error bars represent SEM. n = 3 dams per treatment group, with *, **, ***, and **** representing P < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively, according to two-tailed nested t tests (A and B), nested one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis (D, E, I, J, Q, and R), two-way ANOVA with Šidák's (C), and Tukey’s (G, K, L, M, and O) post hoc analysis.

In addition to IV delivery, we considered other clinically relevant delivery routes, including intramuscular (IM) and intraperitoneal (IP) administration. IM injections are preferred for prophylactic RNA vaccines (36, 37), including the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines (38, 39), while IP injections are used clinically to deliver therapeutics to intraabdominal organs (40–42). All administration routes produced robust protein expression, with IV delivery eliciting the highest placental delivery, followed by IP and IM (Fig. 3 H and I). No route of administration produced luminescence in the fetus (Fig. 3 H and J).

As previously shown (15, 43, 44), the route of delivery in NP mice impacted organ tropism and overall efficacy (Fig. 3K). For example, most luciferase expression for lymphatic tissue, the pancreas, and the liver occurred for IM, IP, and IV delivery, respectively. These route-related differences in tropism extended to Pr mice (Fig. 3K). Interestingly, pregnancy itself did not impact organ tropism for IV delivery but did for IM and IP injections. Specifically, we found that IM delivery increased lymph node expression by eightfold in Pr dams compared to NP mice, whereas IP delivery reduced it by fourfold.

Because LNPs showed efficacy changes only in lymphoid organs of Pr mice, we wondered whether the shifts were related to the immune response elicited by different administration routes. We therefore measured the blood levels of 11 cytokines and chemokines using Luminex, 4 h post-injection. IFNγ and IL-4 were not detected in any sample. Interestingly, IM and IP routes, which had altered tropism, also intensified cytokine and chemokine production compared to IV injections in both pregnant and NP mice (Fig. 3L). Our results suggest that administration methods prone to higher degrees of immunogenicity may alter protein expression during pregnancy.

To examine whether altered tropism in Pr vs. NP mice is induced by a differential innate immune response, we asked whether immunogenic LNPs cause similar shifts in organ distribution. For this, we compared the immunogenic ionizable lipids 503O8,12 and 200Oi10 and the immunoquiescent lipids 306O10 and 306Oi10. All lipids formed monodisperse LNPs that were 100 to 120 nm in size (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) and elicited >90% mRNA encapsulation efficiency (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). Further, innate immunogenicity was determined using a Raw-Blue macrophage NF-κB reporter cell line (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

We then confirmed that 503O8,12 and 200Oi10 were immunogenic in vivo in both Pr and NP CD-1 mice following IV injection (Fig. 3M). Additionally, expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β was substantially lower in Pr dams (Fig. 3M). We found that pregnancy altered organ tropism for immunogenic lipids but not for immunoquiescent lipids (Fig. 3 N and O) and that all four lipids induced placental delivery without fetal accumulation (Fig. 3 P–R). Together, these data indicate that LNPs deliver mRNA to the placenta in mice without penetrating the placental barrier, regardless of the administration route. Further, the degree of inflammation in the mouse affected organ tropism.

LNPs Transfected Placental Trophoblasts, Endothelial Cells, and Immune Cells.

Having shown that LNPs deliver mRNA to the placenta, we next identified the transfected cell types. The mouse placenta contains three layers—decidua (Dec), junctional zone (JZ), and labyrinth (Lab) (Fig. 4B). The Dec is the mucosal lining of the maternal uterus where the embryo implants (45). The Lab is the primary site of nutrient and gas exchange and is enriched in trophoblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells (46, 47). The JZ contains glycogen cells and several trophoblast subtypes (e.g., trophoblast giant cells) and performs endocrine functions, such as hormone regulation, glucose production, and cell metabolism (46, 48). Together, trophoblasts, endothelial cells, and placental immune cells facilitate nutrient and gas exchange and protect the fetus from maternal immune response and invading pathogens.

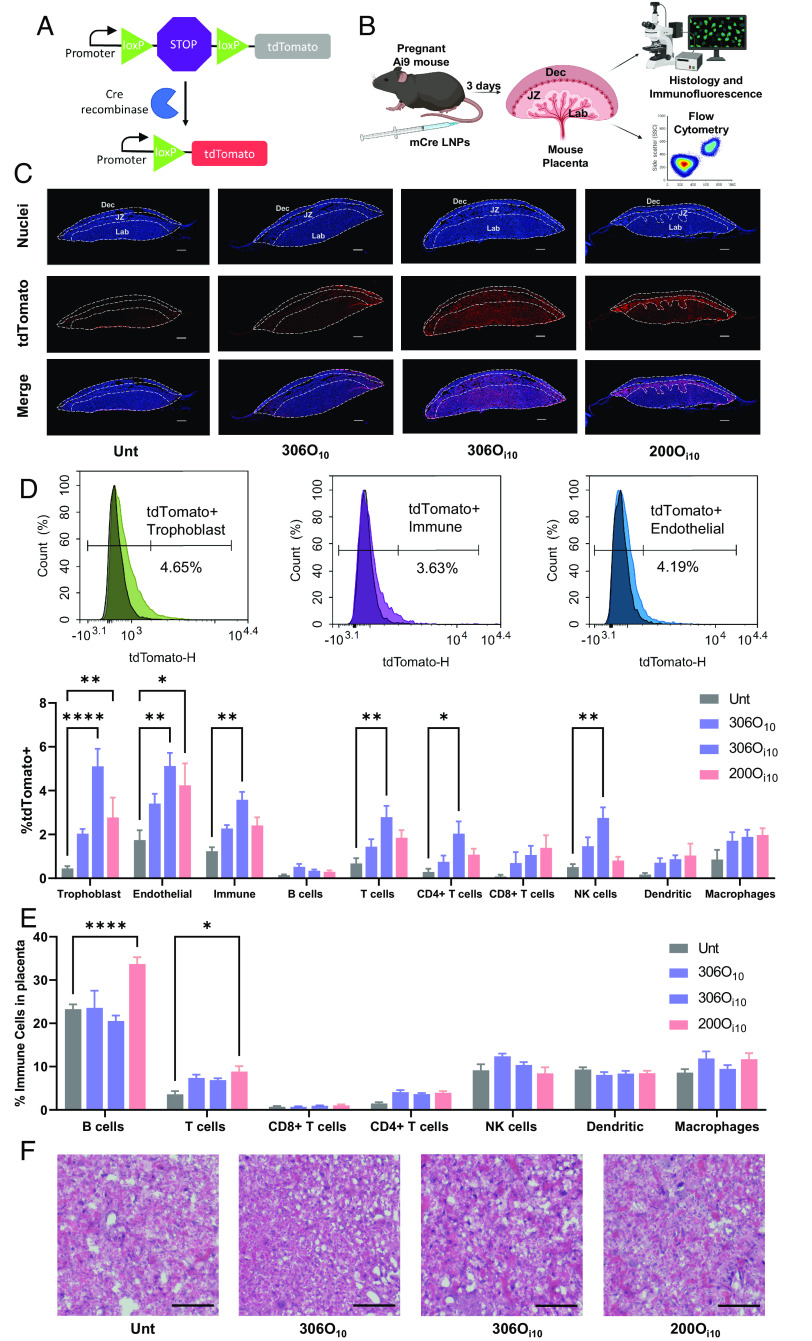

Fig. 4.

The LNP 306Oi10 delivers mRNA to placental trophoblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells in mice. (A) mCre delivery induces Cre-Lox recombination in Ai9 mice and causes tdTomato expression in transfected cells. (B) LNPs formulated with three different ionizable lipids encapsulating mCre were IV-injected in Ai9 mice at 1 mg/kg on the 14th day of pregnancy. After 3 d, mice were killed, and their placentas were analyzed using immunofluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, and histology. (C) Placentas were stained to distinguish nuclei (blue) and tdTomato (red) and visualized using an immunofluorescent microscope. The Dec, JZ, and placental Lab are shown using dotted lines. All scale bars are 0.5 mm. (D) tdTomato expression and (E) immune cell infiltration were measured in isolated placental cells using flow cytometry. (F) Placental morphology was visualized using Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining. All scale bars are 50 μm. Error bars represent SEM. n = 3 dams per treatment group, with *, **, ***, and **** representing P < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively, according to two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis.

To identify transfected placental cell layers, we used transgenic Ai9 mice. These mice carry a tdTomato gene downstream of a loxP-STOP-loxP cassette that, in naive Ai9 mice, prevents tdTomato expression. This model is useful for assessing LNP delivery when incorporating mRNA encoding the protein, Cre recombinase (mCre). In transfected cells, Cre excises the STOP cassette and induces permanent tdTomato expression (Fig. 4A). For this study, the 14th day of pregnancy, we IV-injected mCre encapsulated in the two LNPs with the lowest levels of immunogenicity. Mice were killed after 3 d, and placentae were analyzed for tdTomato expression (Fig. 4B).

First, qualitative assessment using immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that 200Oi10 and 306Oi10 elicited higher tdTomato expression than 306O10 (Fig. 4C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Interestingly, the site of protein expression differed for both LNPs. In addition, 306Oi10 showed uniform delivery to the placental Lab and JZ; however, 200Oi10 induced higher expression in the JZ, and 306O10 showed low expression levels in all areas (Fig. 4C). Flow cytometry data confirmed the superior efficacy of 306Oi10 LNPs for all cell types (Fig. 4D). Delivery via this LNP increased the fraction of tdTomato positive cells 10-, 4-, and 3-fold for trophoblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells, respectively, compared to untreated mice. Among immune cells, 306Oi10 primarily transfected CD4+ T cells and NK cells.

To assess LNP safety, we measured immune cell infiltration into placental tissue and evaluated tissue morphology. Interestingly, the 200Oi10 LNPs that prompted an innate immune response in CD-1 mice (Fig. 3M) also caused higher levels of adaptive immune cells in the placenta. Specifically, 200Oi10 LNPs caused a 1.5-fold increase in B cells and a 2.4-fold increase in T cells compared to untreated animals (Fig. 4E). The immunoquiescent LNPs 306O10 and 306Oi10 (Fig. 4E) did not alter the fraction of immune cells in the placenta. Histological staining showed no gross morphological changes or inflammation in the placental Lab, the latter of which would be evident if there were patches of purple (hemotoxylin) stain. This suggests that LNPs do not damage the placental vasculature (Fig. 4F).

306 LNPs Do Not Affect Pup Development.

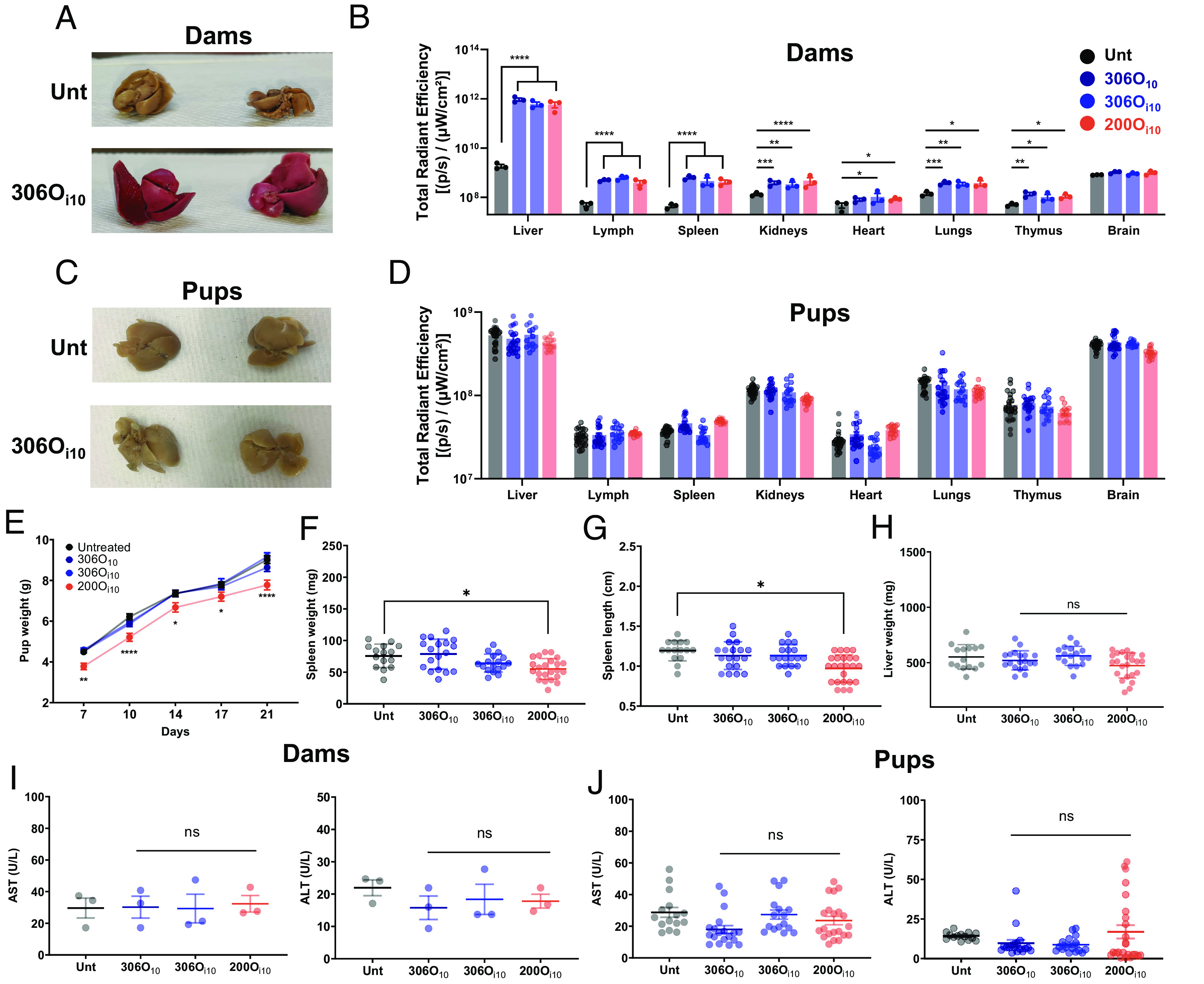

Although our data show no mRNA delivery to the fetus, it is possible that placental transfection nonetheless affects pregnancy outcomes and maternal and pup health. To assess this, we IV-injected mCre-loaded LNPs in Pr Ai9 mice and measured outcomes and monitored pup health for 3 wk post-delivery. The use of the Cre-expressing LNP also allowed us to track LNP deposition in maternal and fetal tissues.

No dam or pup mortality occurred after LNP administration, and no births were considered premature (>19-d gestation period). Mice were killed 3 wk after birth to assess LNP delivery. Strikingly, tdTomato expression in the livers of LNP-treated dams was visible to the naked eye (Fig. 5A). Quantification by IVIS showed >300-fold protein expression in the liver for all LNPs compared to untreated controls (Fig. 5B). Further, all maternal organs except for the brain expressed tdTomato. In contrast, the livers of pups born to LNP-treated dams did not visually express tdTomato (Fig. 5C), with IVIS measurements confirming no tdTomato expression in pups as a function of organ (Fig. 5D). This is consistent with our luciferase delivery data in CD-1 mice that showed no expression in fetuses (Fig. 3 E, J, and R).

Fig. 5.

Both 306O10 and 306Oi10 do not affect pup development. mCre-LNPs were injected in Pr Ai9 mice on the 14th day of pregnancy. Three weeks after birth, mice were killed, and the organs of (A and B) dams and (C and D) pups were analyzed visually or using IVIS. Pup development was assessed by measuring their (E) body weight over 3 wk, and (F) length of their spleen, and the weights of their (G) spleen and (H) liver after the mice were killed. (I and J) AST and ALT were measured in serum of dams and pups to assess hepatotoxicity. Error bars represent SEM. n = 3 dams per treatment group, and 3 to 8 pups per dam with *, **, ***, and **** representing P < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively, according to two-way ANOVA (B, D, and E), one-way ANOVA (I), and nested one-way ANOVA (F, G, H, and J) with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis compared to untreated controls.

In addition to delivery, we monitored pup health. Interestingly, inflammatory 200Oi10 LNPs slowed pup growth, as assessed by overall weight and spleen weight and length (Fig. 5 E–G). There was no reduction in liver weight (Fig. 5H). Furthermore, the ratio of the liver enzymes AST (aspartate aminotransferase) and ALT (alanine aminotransferase) was not elevated in either dams or pups (Fig. 5 I and J), indicating no signs of hepatotoxicity.

Discussion

In this work, we sought to develop safe and potent RNA delivery vehicles with the potential to treat a broad range of pregnancy-related conditions. To this end, we assessed RNA delivery efficacy, toxicity, placental transport, and immunogenicity of multiple LNP structures and clinically relevant administration routes.

Structure-efficacy screening revealed that the amine headgroup dictates delivery in placental BeWo b30 human trophoblasts (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, the headgroups 306, 500, 503, 514, and 516, which are synthetic analogs of the naturally occurring polyamines spermine and spermidine, showed highest efficacy. In mammalian cells, spermine and spermidine regulate gene expression by binding to DNA and RNA, initiating translation, and interacting with transcription factors (49, 50). Because they complex nucleic acids with high affinity, spermine- and spermidine-containing lipids have been used to deliver DNA, siRNA, and mRNA (51–53). Further, polyamine synthesis is known to be critical for fetal development and is up-regulated in the placenta (54). Thus, these polyamine-derived lipids may be a potent choice for placental delivery.

In contrast to delivery, LNP hemolytic activity was governed by the lipid tail (Fig. 1B), with methylated branches eliciting more hemolysis. Branched ionizable lipids likely disrupt red blood cell (RBC) membrane integrity by altering its mechanical properties. Branched lipids are known to disrupt lipid packing by increasing surface area per lipid and elevating membrane microviscosity by restricting lipid motion (55). In the acidic endosome, this disruption is desirable because it facilitates endosomal escape and mRNA delivery to the cytosol; however, membrane disruption in the blood at physiological pH will damage circulating cells, such as red blood cells.

In vivo, LNPs elicited route- and structure-dependent shifts in protein expression in the spleen and lymph nodes of Pr mice (Fig. 3). These therapeutic modalities may require dose adjustment in Pr people. Further, cytokine and chemokine profiles demonstrated that shifts in organ tropism correlated with immunogenic routes and structures. Particularly, intravenous LNP delivery suppressed IL-1β in Pr mice. Interleukin family cytokines, including IL-1α and IL-1β, are potent mobilizers of innate immune cells (56). Because patrolling myeloid cells are among the first cells to uptake LNPs in vivo (57), we suspect that IL-1β suppresses infiltration of transfected myeloid cells in the spleen and lymph node, reducing efficacy in these organs.

In addition to tropism, we found that disrupting immune homeostasis deleteriously affects pup development (Fig. 5). Immunogenic 200Oi10 LNPs elevated B and T cell infiltration in the placenta and impeded pup growth. Although the phenotype of these cells is not known, we suspect that these adaptive immune cells induce inflammatory responses which may adversely affect fetal development. Previously, inflammatory cytokines produced by infiltrating T cells have been shown to affect pup development (58).

Our results highlight that immune homeostasis is critical for fetal safety. Because 306Oi10 LNPs are safe during pregnancy, they can be potentially employed for myriad prophylactic and therapeutic applications. For example, mRNA vaccines encoding lethal pathogens, such as influenza, can be administered IM during pregnancy and protect fetuses from pathogen-induced congenital anomalies (59). Immune-evasive viruses, such as HIV, which elicit neutralizing antibodies in a rare fraction of infected individuals (60), might benefit from passive vaccination strategies. Here, mRNA-LNPs encoding broadly neutralizing antibodies, such as VRC01 (61, 62), BG18 (63), and PGT121 (64), can be translated by hepatocytes after IV delivery and neutralize HIV strains. Since antibodies can cross the placenta via FcRn-mediated transcytosis (65), vertically transferred maternal antibodies can protect the fetus from adverse outcomes of perinatal HIV transmission (66).

For treating maternal disorders where placental delivery is relevant, intravenous mRNA delivery may be the preferred route. We found that 306Oi10 delivered mRNA to the placental junctional and labyrinthine zone and transfected several placental cell types (Fig. 4). Therefore, its therapeutic applications can extend to disorders that involve multiple cell types, such as preeclampsia. For example, protein supplementation by delivering mRNA encoding angiogenic proteins, such as vascular endothelial growth factor or placental growth factor, can promote placental vascularization that is perturbed during preeclampsia (67, 68). Further, silencing anti-angiogenic proteins such as soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) that are overexpressed by trophoblasts during preeclampsia is an attractive therapeutic strategy (2). In this case, transient gene knockdown of sFlt-1 using CRISPRi-based approaches can suppress sFlt-1 levels in the placenta and bloodstream and ameliorate preeclampsia (69, 70).

In this study, we identified potent LNP structures that deliver mRNA to both the placenta and nonreproductive maternal organs without fetal delivery. This study provides a mechanistic basis for pharmacodynamic shifts in LNP delivery during pregnancy. Further, we demonstrate that LNP immunogenicity is a critical parameter for designing safe therapeutics for pregnancy. We anticipate that these data will propel the design of potent LNPs that will establish new pregnancy-safe treatment paradigms.

Methods

Materials.

Amines were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), CHESS Organics (Mannheim, Germany), Acros Organics (Fair Lawn, NJ), and Alfa Aesar (Haverhill, MA). Acrylates were sourced from Scientific Polymer Products (Ontario, NY), Hampford Research, Inc. (Stratford, CT), Monomer-Polymer and Dajac Labs (Trevose, PA), and Sartomer (Warrington, PA). 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) and 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (ammonium salt) (PEG-DMPE) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Cholesterol and sodium citrate were sourced from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Further, 3,500 molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) dialysis cassettes were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA). 5moU-modified mRNAs encoding Cre recombinase (mCre) and firefly luciferase (mLuc) were purchased from TriLink BioTechnologies (San Diego, CA). Cy5-labeled 5moU mRNA was purchased from TriLink BioTechnologies (San Diego, CA) or APExBIO Technologies (Houston, TX). D-Luciferin was obtained from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA). BeWo cells were obtained from ATCC, and BeWo b30 cells were a generous gift from the laboratory of Alan Schwartz (Washington University, St. Louis, MO). DMEM/F12, fetal bovine serum (FBS), donkey serum, penicillin/streptomycin, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), and HEPES were sourced from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA). Lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli 0111:B4 (LPS) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Raw Blue™ cells, Normocin™, Zeocin™, and the QUANTI-Blue™ assay kit were obtained from Invivogen (San Diego, CA). BrightGLO™ was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Human red blood cells were sourced from Innovative Research (Novi, MI), and Triton-X 100 was obtained from Alfa Aesar (Haverhill, MA). Collagenase Type I was purchased from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Lakewood, NJ), and DNAse I was purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA). Formaldehyde was sourced from VWR (Radnor, PA). Hoescht, AF488 phalloidin, AF594 anti-ZO-1, goat anti-RFP, and AF647 donkey anti-goat IgG (H+L) were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA). The Mouse Luminex Discovery Assay kit configured for CCL2, CXCL1, CXCL2, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNFα, and VEGF was purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). 10X RBC lysis buffer and antibodies used for flow cytometry were sourced from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Hematoxylin, Eosin, Scott’s Tap Water Substitute, and xylene were sourced from Millipore Sigma (Burlington, MA). 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Sodium hydroxide, L-alanine, L-aspartic acid, α-ketoglutaric acid, and sodium pyruvate were obtained from Millipore Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Nanoparticle Formulation and Characterization.

Lipids were synthesized and nanoparticles were formulated as previously described (15). Briefly, lipidoids were synthesized using Michael addition chemistry by reacting an amine with an alkyl acrylate at 90 °C for 3 d. The lipidoid, DOPE, cholesterol, and C14-PEG2000 were dissolved in ethanol (90% v/v) and 10 mM sodium citrate (10% v/v) at a molar ratio of 35:16:46.5:2.5. The mRNA was dissolved in 10 mM sodium citrate. Nanoparticles were formed by rapidly pipetting an equal volume of the lipid solution into the RNA solution. Lipids were added at a 10:1 total lipid:mRNA w/w ratio. All nanoparticles injected into mice were dialyzed in PBS for 90 min using 3,500 MWCO dialysis cassettes. Nanoparticle size and dispersity were assessed using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZSP (Malvern, UK). Further, mRNA entrapment was measured using the Quant-iT RiboGreen assay (Thermo Fisher).

In Vitro mRNA Delivery.

BeWo or BeWo b30 cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were seeded at 100,000 cells/well in white flat-bottom 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One). After 48 h, LNPs formulated with firefly luciferase mRNA were added to cells at a dose of 100 ng mRNA per well. Twenty-four hours later, luciferase activity was measured using a Bight-Glo™ Luciferase Assay System (Promega) per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Hemolysis.

Human red blood cells (Innovative Research) were diluted in PBS to make a 4% v/v RBC solution. Then, 100 μL RBC solution was seeded in clear round bottom 96-well plates (Corning), and an equal volume of blank LNPs (i.e., containing no mRNA) formulated at 0.08 mg/mL equivalent mRNA concentration (2,500 ng mRNA/well) was added to the solution. PBS and 1% Triton-X were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. The solution was incubated for 90 min at 37 °C. Cells were centrifuged at 500 RCF, and 100 μL supernatant was transferred to a transparent flat-bottom 96-well plate (Corning). Absorbance was measured at 540/640 nm using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments).

In Vitro Permeability.

BeWo or BeWo b30 cells were seeded on 0.4 μm polycarbonate Transwell® permeable supports (Corning) at 100,000 cells/well. Growth medium was changed daily, and monolayer formation was monitored by measuring TEER using a Millicell voltohmmeter (MilliporeSigma). TEER values >150 Ω cm2 indicated confluent monolayers. On the day of the experiment, Transwell® inserts were transferred into transport buffer (HBSS with 12.5 mM glucose and 25 mM HEPES) and equilibrated at 37 °C for 1 h. To assess transport, Cy5-labeled mRNA (TriLink Biotechnologies) or fluorescent marker molecules were added to the apical side of the inserts. Groups included Cy5-labeled mRNA (naked and LNP-formulated), fluorescein, and 4-kDa and 10-kDa FITC-dextrans at final concentrations of 2.5 μg/mL, 25 μM, and 100 μg/mL, respectively. Transwells® were then incubated at 37 °C and 25 RPM for 2 h in a New Brunswich™ Innova® 40 shaker (Eppendorf). Samples were collected every hour from the basolateral side. Cy-5 and fluorescein/FITC fluorescence were measured at 650/670 nm and 485/530 nm, respectively, using a plate reader. Apparent permeability (Papp) was calculated using the equation:

where Papp is the apparent permeability, ΔM is the mass of the fluorescent molecule transported into the basolateral compartment, Ca is the concentration of the fluorescent molecule on the apical side, A is the area of the insert, and Δt is the time interval.

Immunocytochemistry.

BeWo b30 monolayers were rinsed with PBS fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde. Samples were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X and blocked with 5% FBS in PBS. Monolayers were stained with 1 μg/mL Hoescht, 165 nM AF488 phalloidin, and 1 μg/mL AF594 anti-ZO-1 antibody for at least an hour. Monolayers were mounted on slides and imaged using a fluorescence microscope.

In Vivo Biodistribution.

Mouse experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Carnegie Mellon University under protocol number PROTO201600048. Pr CD-1 mice were purchased from Charles River, and 306Oi10 LNPs encapsulating Cy5-labeled luciferase mRNA (APExBIO) or naked Cy5-labeled mRNA were injected IV on the 14th day of pregnancy at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg mRNA. Four hours later, mice were killed, and organs were imaged using IVIS (PerkinElmer) at Ex/Em: 620/670 nm, and total radiant efficiency (p/s)/(μW/cm2) was calculated using region of interest analysis using Living Image® software.

In Vivo mLuc Delivery.

Pr CD-1 mice were dosed with LNPs encapsulating luciferase mRNA on the 14th day of pregnancy. Four hours after LNP injection, mice were IP-injected with 130 μL D-Luciferin (30 mg/mL in PBS). Fifteen minutes later, mice were killed, and organs and blood were collected. Organ luminescence was measured using IVIS® (PerkinElmer), and luminescent flux (photons/s) was determined using region of interest analysis using Living Image® software. Blood samples were centrifuged at 12,000 RPM for 10 min, and serum cytokines and chemokine levels were measured using Luminex per the manufacturer’s instructions.

In Vivo mCre Delivery.

Pr Ai9 mice were obtained from an institutionally managed animal colony and dosed with LNPs encapsulating mRNA encoding Cre Recombinase on the 14th day of pregnancy. For placenta delivery experiments, mice were IV-injected with 1 mg/kg LNPs. After 3 d, mice were killed, and placentae were either processed for flow cytometry or immediately fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for histological and immunofluorescence analysis. For pup growth experiments, Pr mice were IV-injected with 0.5 mg/kg LNPs. Twenty-one days postpartum, dams and pups were killed, and their organs and blood were collected. Organs were imaged using IVIS®, and total radiant efficiency (p/s)/(μW/cm2) was calculated using region of interest analysis using Living Image® software. Serum was isolated from blood and analyzed for aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase activity.

Flow Cytometry.

Placentas were harvested, placed in DMEM at 4 °C after removing the Dec, and digested for 35 min in 1 mL digestion buffer (DMEM, 500 units/mL collagenase I, and 8 units/μL DNAse I). Cells were passed through a 70-μm cell strainer, washed with cold DMEM, and centrifuged at 400 g. Red blood cells were lysed using 1X RBC lysis buffer (BioLegend). Cells were stained with fixable yellow viability dye (1:1,000 dilution) for 15 min at 4 °C as per the manufacturer’s instructions. After staining, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min and blocked with 5% FBS. Cells were stained with an antibody panel for lymphoid cells, myeloid cells, or trophoblasts. In the lymphoid panel, cells were stained with Fc block, PerCP anti-mouse CD45 (clone: 30-F11), PE-Cy7 anti-mouse CD4 (clone: GK-1.5), BV605 anti-mouse CB8a (clone: 53-6.7), BV421 anti-mouse CD19 (clone: 6D5), BV785 anti-mouse CD3 (clone: 17A2), and APC anti-mouse CD49b (clone: D × 5). In the myeloid panel, cells were stained with Fc block, PerCP anti-mouse CD45 (clone: 30-F11), APC anti-mouse CD11c (clone: N418), BV650 anti-mouse CD11b (clone: M1/70), and BV785 anti-mouse F4/80 (clone: BM8). In the trophoblast panel, cells were stained with Fc block, PerCP anti-mouse CD45 (clone: 30-F11), BV785 anti-mouse CD31 (clone: 390), and polyclonal rabbit anti-cytokeratin seven followed by goat anti-rabbit AF647 secondary. All antibodies were added at a concentration of 2 μg/mL for 35 min. After staining, cells were resuspended in 5% FBS and analyzed by flow cytometry using a NovoCyte 3000 (ACEA Biosciences). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using NovoExpress software. The gating scheme is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S6.

Immunofluorescence and Histology.

Placentas were dissected and immediately fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 2 d at 4 °C. Placentas were washed with PBS and dehydrated by incubating in 15% and 30% sucrose for 12 h each. Samples were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue Tek), snap-frozen using liquid nitrogen, and sliced into 10-μm sections on ColorFrost plus microscope slides (Fisher Scientific). For immunofluorescence imaging, samples were subject to antigen retrieval by incubating in 10 mM citrate buffer/0.05% Tween-20 (pH 6) at 95 °C followed by autofluorescence reduction in 10 mM copper sulfate/50 mM ammonium acetate at 37 °C for 20 min each. Samples were blocked and stained with 5 μg/mL anti-RFP for 12 h, washed 3× with PBS, followed by staining with 5 μg/mL AF647 donkey anti-goat IgG (H+L) for 1 h. Samples were counterstained with 100 ng/mL DAPI for 15 min, mounted on cover slides, and imaged using a fluorescent microscope. For histology, samples were stained with hematoxylin for 4 min, rinsed with 0.3% HCl in 70% EtOH, rinsed in Scott’s tap water, and stained with eosin for 2 min. Slides were washed with PBS between each step. After staining, slides were dehydrated in 95 and 100% EtOH, cleared with xylene, mounted on cover slides, and imaged using a bright-field microscope.

ALT and AST Activity.

Serum ALT and AST activities were measured using the Reitman–Frenkel method (71). Briefly, samples were diluted 1:1 with PBS, and 10 μL diluted samples were incubated with 50 μL solution containing 2 mM α-ketoglutaric acid and 200 mM amino acid at 37 °C for 60 min. L-alanine and L-aspartic acid were used as the amino acids for ALT and AST activity, respectively. Sodium pyruvate was used to generate a standard curve. After an hour, 50 μL of 1 mM 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine in 1 M hydrochloric acid was added and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 200 μL 0.4N NaOH, and absorbance was measured at 510/660 nm using a plate reader.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the NIH, grant number DP2-HD098860, the Wadhwani Foundation, and generous support from Jon Saxe and Myrna Marshall. M.L.A. was supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program award (number DGE1745016).

Author contributions

N.C., Y.S., and K.A.W. designed research; N.C., A.N.N., M.L.A., S.S.Y., S.T.L., R.D., D.M.S.P., C.M., J.S.K., B.F., T.C., and A.M. performed research; N.C., A.N.N., M.L.A., and S.S.Y. analyzed data; K.A.W. secured funding and oversight of project; and N.C., A.N.N., M.L.A., S.S.Y., Y.S., and K.A.W. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

K.A.W. is an inventor on patents related to the materials described here, including 9,227,917 and 9,439,968. K.A.W. is a consultant for several companies regarding non-viral RNA delivery.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Flow cytometry and imaging data have been deposited in Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/8342810) (72).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Nelson K. M., Irvin-Choy N. D., Hoffman M. K., Gleghorn J. P., Day E. S., Diseases and conditions that impact maternal and fetal health and the potential for nanomedicine therapies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 170, 425–438 (2020), 10.1016/j.addr.2020.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turanov A. A., et al. , RNAi modulation of placental sFLT1 for the treatment of preeclampsia. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 1164–1173 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allotey J., et al. , Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: Living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 370, m3320 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shields K. E., Lyerly A. D., Exclusion of pregnant women from industry-sponsored clinical trials. Obstet. Gynecol. 122, 1077–1081 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Y., et al. , Registered clinical trials comprising pregnant women in China: A cross-sectional study. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1043 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freyer A. M., Drugs in pregnancy and lactation 8th edition: A reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk. Obstet. Med. 2, 89 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajj K. A., Whitehead K. A., Tools for translation: Non-viral materials for therapeutic mRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17056 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figueroa-Espada C. G., Mitchell M. J., Riley R. S., Hofbauer S., Exploiting the placenta for nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery during pregnancy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 160, 244–261 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabnis S., et al. , A novel amino lipid series for mRNA delivery: Improved endosomal escape and sustained pharmacology and safety in non-human primates. Mol. Ther. 26, 1509–1519 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitehead K. A., et al. , Degradable lipid nanoparticles with predictable in vivo siRNA delivery activity. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–10 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Love K. T., et al. , Lipid-like materials for low-dose, in vivo gene silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1864–1869 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hou X., Zaks T., Langer R., Dong Y., Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 612, 1078–1094 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melo M., et al. , Immunogenicity of RNA replicons encoding HIV Env immunogens designed for self-assembly into nanoparticles. Mol. Ther. 27, 2080–2090 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qu L., et al. , Circular RNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 and emerging variants. Cell 185, 1728–1744.e16 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajj K. A., et al. , A potent branched-tail lipid nanoparticle enables multiplexed mRNA delivery and gene editing in vivo. Nano Lett. 20, 5167–5175 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellington S., Olson C. K., Safety of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 1514–1515 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadarangani M., et al. , Safety of COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy: A Canadian National Vaccine Safety (CANVAS) network cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 1553–1564 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halasa N. B., et al. , Maternal vaccination and risk of hospitalization for Covid-19 among infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 109–119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad S., et al. , Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and perinatal outcomes of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat. Commun. 131, 1–8 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young R. E., et al. , Lipid nanoparticle composition drives mRNA delivery to the placenta. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2022). 10.1101/2022.12.22.521490 (Accessed 13 October 2023). [DOI]

- 21.Swingle K. L., et al. , Ionizable lipid nanoparticles for in vivo mRNA delivery to the placenta during pregnancy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 4691–4706 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Safford H. C., et al. , Orthogonal design of experiments for engineering of lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery to the placenta. Small, 10.1002/smll.202303568 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omata W., Ackerman W. E. IV, Vandre D. D., Robinson J. M., Trophoblast cell fusion and differentiation are mediated by both the protein kinase C and a pathways. PLoS One 8, e81003 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdelkhaliq A., Van Der Zande M., Peters R. J. B., Bouwmeester H., Combination of the BeWo b30 placental transport model and the embryonic stem cell test to assess the potential developmental toxicity of silver nanoparticles. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 17, 1–16 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H., van Ravenzwaay B., Rietjens I. M. C. M., Louisse J., Assessment of an in vitro transport model using BeWo b30 cells to predict placental transfer of compounds. Arch. Toxicol. 87, 1661–1669 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nanovskaya T., et al. , Role of P-glycoprotein in transplacental transfer of methadone. Biochem. Pharmacol. 69, 1869 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vitale N., et al. , Dose-dependent fetal complications of warfarin in pregnant women with mechanical heart valves. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 33, 1637–1641 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wice B., Menton D., Geuze H., Schwartz A. L., Modulators of cyclic AMP metabolism induce syncytiotrophoblast formation in vitro. Exp. Cell Res. 186, 306–316 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hajj K. A., et al. , Branched-tail lipid nanoparticles potently deliver mRNA in vivo due to enhanced ionization at endosomal pH. Small 15, 1805097 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tornavaca O., et al. , ZO-1 controls endothelial adherens junctions, cell–cell tension, angiogenesis, and barrier formation. J. Cell Biol. 208, 821 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brett K. E., Ferraro Z. M., Yockell-Lelievre J., Gruslin A., Adamo K. B., Maternal–fetal nutrient transport in pregnancy pathologies: The role of the placenta. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 16153–16185 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandorkar G. A., Ampasavate C., Stobaugh J. F., Audus K. L., Peptide transport and metabolism across the placenta. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 38, 59–67 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossant J., Cross J. C., Placental development: Lessons from mouse mutants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 27, 538–548 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elmore S. A., et al. , Histology atlas of the developing mouse placenta. Toxicol. Pathol. 50, 60 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ander S. E., Diamond M. S., Coyne C. B., Immune responses at the maternal-fetal interface. Sci. Immunol. 4, eaat6114 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alameh M.-G., Weissman D., Pardi N., Messenger RNA-Based Vaccines against Infectious Diseases (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2020), pp. 1–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pardi N., Hogan M. J., Porter F. W., Weissman D., mRNA vaccines–a new era in vaccinology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 261–279 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corbett K. S., et al. , SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature 586, 567–571 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vogel A. B., et al. , BNT162b vaccines protect rhesus macaques from SARS-CoV-2. Nature 592, 283–289 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Smet L., Ceelen W., Remon J. P., Vervaet C., Optimization of drug delivery systems for intraperitoneal therapy to extend the residence time of the chemotherapeutic agent. Sci. World J. 2013, 720858 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dirnena-Fusini I., Åm M. K., Fougner A. L., Carlsen S. M., Christiansen S. C., Physiological effects of intraperitoneal versus subcutaneous insulin infusion in patients with diabetes mellitus type 1: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 16, e0249611 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Melamed J. R., et al. , Ionizable lipid nanoparticles deliver mRNA to pancreatic β cells via macrophage-mediated gene transfer. Sci. Adv. 9, eade1444 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderluzzi G., et al. , The role of nanoparticle format and route of administration on self-amplifying mRNA vaccine potency. J. Control. Release 342, 388 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pardi N., et al. , Expression kinetics of nucleoside-modified mRNA delivered in lipid nanoparticles to mice by various routes. J. Control. Release 217, 345–351 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mori M., Bogdan A., Balassa T., Csabai T., Szekeres-Bartho J., The decidua—The maternal bed embracing the embryo—Maintains the pregnancy. Semin. Immunopathol. 38, 635 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marsh B., Blelloch R., Single nuclei RNA-seq of mouse placental labyrinth development. Elife 9, 1–27 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson E. D., Cross J. C., Development of structures and transport functions in the mouse placenta. Physiology (Bethesda) 20, 180–193 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simmons D. G., Fortier A. L., Cross J. C., Diverse subtypes and developmental origins of trophoblast giant cells in the mouse placenta. Dev. Biol. 304, 567–578 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pegg A. E., Functions of polyamines in mammals. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 14904 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aumiller W. M., Pir Cakmak F., Davis B. W., Keating C. D., RNA-Based coacervates as a model for membraneless organelles: Formation, properties, and interfacial liposome assembly. Langmuir 32, 10042–10053 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Viola J. R., et al. , Fatty acid–spermine conjugates as DNA carriers for nonviral in vivo gene delivery. Gene Ther. 16, 1429–1440 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakamoto K., Akao Y., Furuichi Y., Ueno Y., Enhanced intercellular delivery of cRGD-siRNA conjugates by an additional oligospermine modification. ACS Omega 3, 8226–8232 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ding F., Zhang H., Cui J., Li Q., Yang C., Boosting ionizable lipid nanoparticle-mediated in vivo mRNA delivery through optimization of lipid amine-head groups. Biomater. Sci. 9, 7534–7546 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lopez-Garcia C., Lopez-Contreras A. J., Cremades A., Castells M. T., Peñafiel R., Transcriptomic analysis of polyamine-related genes and polyamine levels in placenta, yolk sac and fetus during the second half of mouse pregnancy. Placenta 30, 241–249 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hashiba K., et al. , Branching ionizable lipids can enhance the stability, fusogenicity, and functional delivery of mRNA. Small Sci. 3, 2200071 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rider P., et al. , IL-1α and IL-1β recruit different myeloid cells and promote different stages of sterile inflammation. J. Immunol. 187, 4835–4843 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lindsay K. E., et al. , Visualization of early events in mRNA vaccine delivery in non-human primates via PET–CT and near-infrared imaging. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 3, 371–380 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Graham J. J., Longhi M. S., Heneghan M. A., T helper cell immunity in pregnancy and influence on autoimmune disease progression. J. Autoimmun. 121, 102651 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chaudhary N., Weissman D., Whitehead K. A., mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: Principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 817–838 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee J. H., Crotty S., HIV vaccinology: 2021 update. Semin. Immunol. 51, 101470 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pardi N., et al. , Administration of nucleoside-modified mRNA encoding broadly neutralizing antibody protects humanized mice from HIV-1 challenge. Nat. Commun. 8, 6–13 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Corey L., et al. , Two randomized trials of neutralizing antibodies to prevent HIV-1 acquisition. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1003–1014 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sok D., Burton D. R., Recent progress in broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV. Nat. Immunol. 19, 1179–1188 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lindsay K. E., et al. , Aerosol delivery of synthetic mRNA to vaginal mucosa leads to durable expression of broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV. Mol. Ther. 28, 805–819 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roopenian D. C., Akilesh S., FcRn: The neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 715–725 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amin O., Powers J., Bricker K. M., Chahroudi A., Understanding viral and immune interplay during vertical transmission of HIV: Implications for cure. Front. Immunol. 12, 4287 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumasawa K., et al. , Pravastatin induces placental growth factor (PGF) and ameliorates preeclampsia in a mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1451–1455 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Logue O. C., Mahdi F., Chapman H., George E. M., Bidwell G. L., A maternally sequestered, biopolymer-stabilized vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) chimera for treatment of preeclampsia. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. Cardiovasc. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 6, e007216 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cox D. B. T., et al. , RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13. Science 358, 1019–1027 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qi L. S., et al. , Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell 152, 1173 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reitman S., Frankel S., A colorimetric method for the determination of serum glutamic oxalacetic and glutamic pyruvic transaminases. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 28, 56–63 (1957). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chaudhary N., et al. , Lipid nanoparticle structure and delivery route during pregnancy dictates mRNA potency, immunogenicity, and maternal and fetal outcomes. Zenodo. https://zenodo.org/records/8342810. Deposited 15 September 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

Flow cytometry and imaging data have been deposited in Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/8342810) (72).