About 6.2 million adults in the United States (US) carry a diagnosis of heart failure [1]. It is difficult to estimate the incidence and prevalence of end-stage systolic heart failure (ESHF) due to the lack of formal collection of data and reporting. The life-saving therapies for ESHF include orthotopic heart transplantation (OHT) and left ventricular assist devices (LVAD). The imbalance between donor availability and the growing waitlist makes LVAD a viable strategy to improve survival in ESHF patients. Durable continuous flow LVADs were initially approved as a bridge to heart transplant in 2008, and destination therapy in 2010 [1]. This transition was driven by a shift in LVAD engineering from pulsatile to continuous flow devices, design advancements, improved device longevity, more favorable side effect profile, and increased patient satisfaction [2].

The current study was based on the data obtained from the National Inpatient Database (NIS) 2003–2019. The traditional complications of LVAD were identified using the standard International Classification of Disease, Clinical Modifications codes 9 and 10 (ICD-CM-9 and ICD-CM-10). Using a linear regression model, the annual trend of device-related complications, in-hospital mortality, heart transplant procedure, and transplant waitlist was obtained for patients with a history of LVAD implantation. The annual percentages of complications were obtained by dividing the number of events in a particular year by the total number of corresponding events from 2003 to 2019.

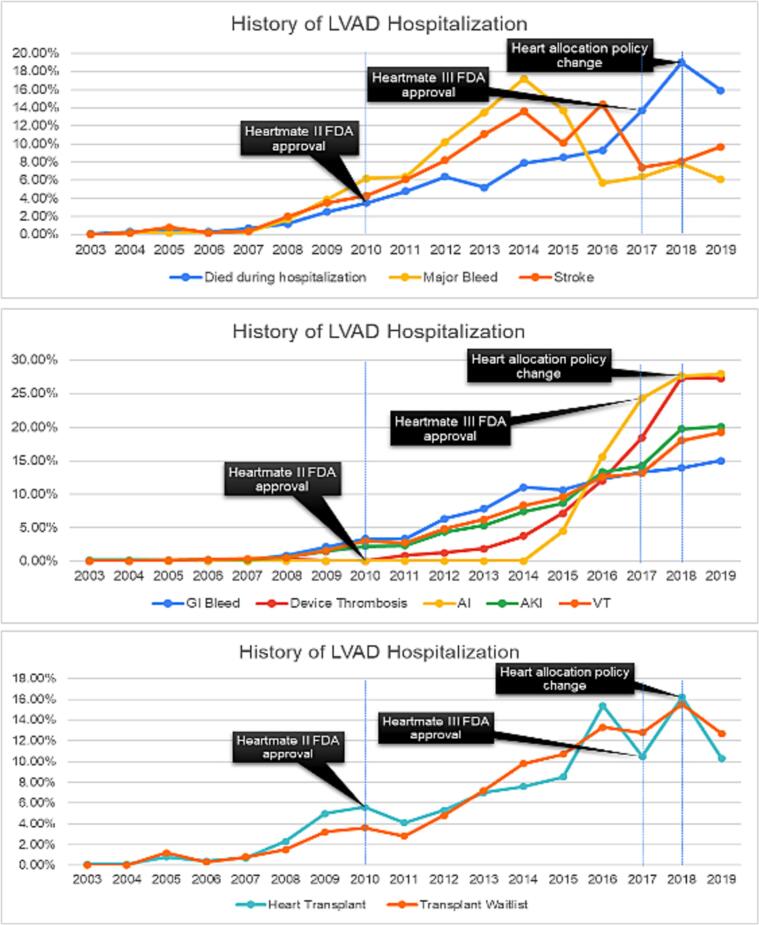

Our study shows a total of 116,326 LVAD-related weighted hospitalizations during 2003–2019. We observed a steep increase in hospitalization of patients with a prior history of LVAD implantation from 2003 to 2018 and a plateaued rate of LVAD use in 2019 (Table 1). The all-cause in-hospital mortality ran parallel with the trend of LVAD hospitalization peaking at 19 % in 2018 but declining to ∼15 % per total number of mortality in LVAD hospitalizations in 2019 (r2 = 0.83, p = 0.01). The uprising trend of major bleeding and stroke peaked at 18 % and 14 % per total number of major bleeding and stroke events in 2013 and 2016, respectively. The risk of stroke declined to 8 % in 2018 but rose by 2 % in 2019. The annual trend of aortic insufficiency and device thrombosis observed a steep increase till 2018 (25 %) but plateaued in recent years. Similarly, the risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, ventricular tachycardia, and acute kidney injury (AKI) had a gradually increasing trend till 2017, a steep increase in 2018, and a plateaued incidence in 2019. Patients with a history of LVAD had a declining trend in the heart transplant candidacy and heart transplant procedure from 2018 to 2019 (r2 = 0.76, p = 0.04) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

The total number and annual percentage of LVAD related hospitalizations during the study period.

| LVAD | LVAD percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 39 | 0.00 % |

| 2004 | 162 | 0.10 % |

| 2005 | 437 | 0.40 % |

| 2006 | 280 | 0.20 % |

| 2007 | 479 | 0.40 % |

| 2008 | 1281 | 1.10 % |

| 2009 | 2702 | 2.30 % |

| 2010 | 3659 | 3.10 % |

| 2011 | 3867 | 3.30 % |

| 2012 | 6025 | 5.20 % |

| 2013 | 7800 | 6.70 % |

| 2014 | 9875 | 8.50 % |

| 2015 | 10,880 | 9.40 % |

| 2016 | 14,550 | 12.50 % |

| 2017 | 15,295 | 13.10 % |

| 2018 | 19,350 | 16.60 % |

| 2019 | 19,645 | 16.90 % |

Fig. 1.

Trend of LVAD related complications out of total number of respective complications during the study period (AKI: acute kidney injury, AI: aortic insufficiency, VT: ventricular tachycardia), transplant waitlist and heart transplant procedure.

Since the initial approval of HeartMate Vented Electric (VE) in 1994 and HeartMate II in 2008, there has been tremendous advancement in device technology leading to the approval of HeartWare (2012) and HeartMate III (2017) [1]. Overall, the risk of device-associated thrombosis, anticoagulation, angiodysplasia-related major bleeding events, and ventricular tachycardia events was substantially higher with earlier generation LVAD devices [1]. There was a net decline in the trend of device-related complications with newer devices. HeartMate III, the latest LVAD, is currently the most commonly used device, presumably due to its safe and most efficacious functionality attributed largely to its innovative pump design, magnetically levitated rotor, wide flow paths, and an artificial pulse [3]. However, our study showed a persistently up-rising trend of device-related thrombosis from 19 % to 27 % during 2017–2018 presumably due to higher use of older devices. HeartMate III levitates magnetically with a continuous centrifugal-flow pump as compared to a mechanical-bearing continuous axial-flow pump in HeartMate II, helping to decrease shear stress on platelets and consequently resulting in a lower incidence of major bleeding and stroke [4]. In our study, a 6 % and 12 % decline in the risk of major bleeding and stroke was observed during 2017, respectively. All types of complications plateaued or slightly decreased in 2019 due to the higher utilization of HeartMate III devices.

A steady rate of device-related complications and a steep decrease in all-cause mortality, transplant candidacy, and heart transplant procedures in 2018–19 could plausibly be linked with the change in the adult heart allocation policy (AHAP) in 2018 [1]. The new policy was designed to prioritize the most critically ill heart transplant candidates, resulting in lower prioritization of stable patients with LVADs [1]. This explains a lower utilization of LVAD and a declining trend of all-cause mortality from 2018 onwards. As a sicker cohort of ESHF patients is now utilizing the temporary percutaneous mechanical circulatory support (MCS) devices as a means to qualify for status 1 and status 2 criteria of AHAP, the LVAD-associated complications started decreasing during the recent years.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Eisen H.J. Left ventricular assist devices (LVADS): history, clinical application and complications. Korean Circ. J. 2019;49(7):568–585. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2019.0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J.H., Cowger J.A., Shah P. The evolution of mechanical circulatory support. Cardiol. Clin. 2018;36(4):443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karmonik C., Partovi S., Schmack B., et al. Comparison of hemodynamics in the ascending aorta between pulsatile and continuous flow left ventricular assist devices using computational fluid dynamics based on computed tomography images. Artif. Organs. 2014;38(2):142–148. doi: 10.1111/aor.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho S.-M., Hassett C., Rice C.J., Starling R., Katzan I., Uchino K. What causes LVAD-associated ischemic Stroke? Surgery, pump thrombosis, antithrombotics, and infection. ASAIO J. 2019;65(8):775–780. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]