Abstract

The trajectory of several cardiovascular diseases (CVD), including acute myocardial infarction (AMI), has been adversely impacted by COVID-19, resulting in a worse prognosis. The Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) has been found to affect certain CVD outcomes. In this cross-sectional analysis, we investigated the association between the SVI and comorbid COVID-19 and AMI mortality using the CDC databases. The SVI percentile rankings were divided into four quartiles, and age-adjusted mortality rates were compared between the lowest and highest SVI quartiles. Univariable Poisson regression was utilized to calculate risk ratios. A total of 5779 excess deaths and 1.17 excess deaths per 100,000 person-years (risk ratio 1.62) related to comorbid COVID-19 and AMI were attributable to higher social vulnerability. This pattern was consistent across the majority of US subpopulations. Our findings offer crucial epidemiological insights into the influence of the SVI and underscore the necessity for targeted therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Social vulnerability, Disparities, Epidemiology, Outcomes

COVID-19 may yield multiple cardiovascular complications, including acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and is associated with worse prognosis [1]. The social vulnerability index (SVI), a measure of resilience among United States (US) communities when confronted by external stressors, has been shown to impact a wide spectrum of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [2]. The SVI is based on four unique themes, encompassing 16 social factors, displayed in Table 1. In this study, we evaluate the impact of the SVI on comorbid COVID-19 and AMI mortality rates in the US.

Table 1.

Social vulnerability index.

| Household characteristics | Socioeconomic status | Housing Type and Transportation | Racial and ethnic minority status (one of the below) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aged 17 or younger | No high school diploma | Mobile homes | Hispanic or Latino |

| Aged 65 or older | Housing cost burden | Crowding | Black and African American |

| Civilian with a disability | Below 150 % poverty | Group quarters | American Indian and Alaska Native |

| English language proficiency | Unemployed | No vehicle | Asian |

| Single-parent households | No health insurance | Multi-unit structures | Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander |

Table depicts the four themes and 16 social factors encompassed within the SVI ranking.

Abbreviations: SVI = social vulnerability index.

SVI and US mortality data were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry and Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research databases, respectively [3,4]. Mortality information were queried through death certificates by International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revisions (ICD-10) codes, provided through the National Vital Statistics System. All deaths related to COVID-19 (ICD-10: U07.1) and AMI (ICD-10: I21) in the multiple causes of death files were obtained from January 1st 2020 to December 31st 2021, and corresponding demographic information (i.e., sex, ethnicity and race, and area of residence) were made available. Ethnicity was classified as Hispanic (all decedents with Spanish origin) or non-Hispanic populations, which cumulatively encompassed the US population unless this was classified as “Other” on their death certificates. Race was described as non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander populations. Mortality data was adjusted to age using the direct method with the 2000 US population as the standard. Absolute death counts, population sizes, and crude-mortality rates are made available in the CDC databases and are easily replicable.

SVI data were obtained in the form of overall percentile rankings from 0 to 1, with 1 being indicative of higher social vulnerability. County-level percentile rankings (3141 counties) were grouped into four quartiles, with quartile 1 (Q1) being the least socially vulnerable, and quartile 4 (Q4) being the most socially vulnerable. Excess or less deaths per 100,000 person-years were estimated by comparison of age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMR) between Q4 and Q1, and risk ratios were estimated through univariable Poisson regression analyses. Confidence intervals that did not include 1 were considered significant. Institutional review board was not necessary given the anonymized and publicly available nature of the data.

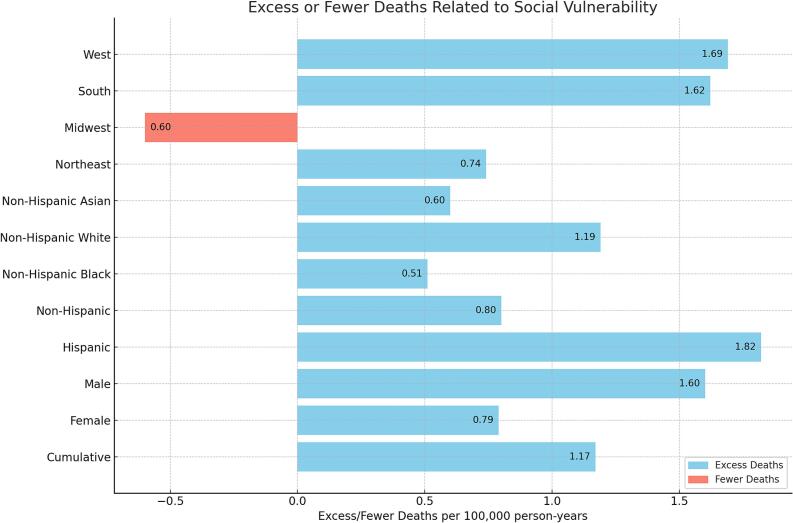

A total of 19,633 deaths related to AMI and COVID-19 were identified in 2020 and 2021. There were 2253 deaths in Q1 and 8032 deaths in Q4, with higher social vulnerability accounting for 5779 excess deaths in the US. AAMR was higher in Q4 (3.07) as compared to Q1 (1.90) and higher SVI accounted for a cumulative 1.17 excess deaths per 100,000 person-years (RR: 1.62 [95 % CI, 1.54–1.69]) (Table 2). Subgroup analyses by sex revealed similar trends. Higher SVI accounted for 1.60 and 0.79 excess deaths per 100,000 person-years in males (RR: 1.59 [95 % CI, 1.50–1.69]) and females (RR: 1.61 [95 % CI, 1.49–1.73]), respectively (Fig. 1). Both Hispanic and non-Hispanic populations were also impacted by higher AMI and COVID-19 mortality in regions with higher social vulnerability. Specifically, 1.82 and 0.80 excess deaths per 100,000 person-years were observed for Hispanic (RR: 1.64 [95 % CI, 1.32–2.03]) and non-Hispanic (RR: 1.43 [95 % CI, 1.36–1.50]) populations, respectively. These findings were consistent across non-Hispanic White (RR: 1.63 [95 % CI, 1.55–1.72]) populations but not for non-Hispanic Black (RR: 1.18 [95 % CI, 0.97–1.45]) and non-Hispanic Asian populations (RR: 1.32 [95 % CI, 0.98–1.77]). Three of the US census regions (i.e., Northeast, South, and West) were negatively impacted by higher AMI and COVID-19 mortality in regions with higher social vulnerability whereas the Midwest (RR: 0.72 [95 % CI, 0.64–0.80]) was not impacted.

Table 2.

COVID-19 and acute myocardial infarction mortality across SVI quartiles.

| Q1-AAMR (95 % CI) | Q2-AAMR (95 % CI) | Q3-AAMR (95 % CI) | Q4-AAMR (95 % CI) | RR (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative | |||||

| All | 1.9 (1.82–1.98) | 1.94 (1.88–2.00) | 2.27 (2.21–2.33) | 3.07 (3.00–3.14) | 1.62 (1.54–1.69) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 1.3 (1.22–1.39) | 1.26 (1.19–1.33) | 1.51 (1.44–1.58) | 2.09 (2.01–2.16) | 1.61 (1.49–1.73) |

| Male | 2.69 (2.54–2.83) | 2.76 (2.65–2.87) | 3.21 (3.09–3.32) | 4.29 (4.16–4.41) | 1.59 (1.50–1.69) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 2.85 (2.25–3.56) | 2.2 (1.89–2.51) | 3.38 (3.10–3.66) | 4.67 (4.48–4.86) | 1.64 (1.32–2.03) |

| Non-Hispanic | 1.87 (1.79–1.95) | 1.91 (1.85–1.97) | 2.16 (2.10–2.23) | 2.67 (2.60–2.74) | 1.43 (1.36–1.50) |

| Race | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2.79 (2.25–3.43) | 2.14 (1.88–2.41) | 2.81 (2.58–3.04) | 3.3 (3.14–3.47) | 1.18 (0.97–1.45) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.88 (1.79–1.96) | 1.98 (1.91–2.04) | 2.23 (2.16–2.30) | 3.07 (2.99–3.15) | 1.63 (1.55–1.72) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1.89 (1.39–2.50) | 1.26 (1.04–1.48) | 1.82 (1.57–2.06) | 2.49 (2.24–2.74) | 1.32 (0.98–1.77) |

| Census Region | |||||

| Northeast | 1.68 (1.53–1.84) | 1.75 (1.64–1.87) | 1.83 (1.70–1.96) | 2.42 (2.24–2.59) | 1.44 (1.29–1.61) |

| Midwest | 2.13 (2.01–2.25) | 2.47 (2.33–2.62) | 2.44 (2.28–2.59) | 1.53 (1.38–1.69) | 0.72 (0.64–0.80) |

| South | 1.84 (1.64–2.04) | 2.00 (1.90–2.11) | 2.62 (2.51–2.73) | 3.46 (3.35–3.56) | 1.88 (1.69–2.10) |

| West | 1.47 (1.24–1.70) | 1.35 (1.24–1.47) | 1.91 (1.80–2.02) | 3.16 (3.03–3.30) | 2.15 (1.84–2.52) |

Table includes all AAMRs across the SVI quartiles. Risk ratios and corresponding 95 % confidence intervals are depicted through comparison of Q4 and Q1.

Abbreviations: AAMR = age-adjusted mortality rate, AMI = acute myocardial infarction, CI = confidence interval, Q = quartile, SVI = social vulnerability index.

Fig. 1.

Excess or fewer deaths related to social vulnerability.

Bar chart depicts the excess or fewer acute myocardial infarction and COVID-19 related deaths per 100,000 person-years related to greater social vulnerability (Q4 compared to Q1).

Abbreviations: Q = quartile.

We identified the impact of higher SVI resulting in greater COVID-19 and AMI mortality, consistently across the majority of our included demographic subpopulations. These findings have important epidemiological implications and provide foundational knowledge regarding the impact of social vulnerability in the US.

SVI has been associated with a wide range of socioeconomic inequalities, translating into healthcare barriers. Regions with higher SVI often have crowded living conditions and greater number of front-line workers that work away from home, increasing risk of COVID-19 exposure [2]. Socially vulnerable communities are also exposed to a higher pollution burden, increasing risk of adverse outcomes related to COVID-19 [5]. These same areas include more challenges towards implementation of preventive measures including hygiene practices, vaccinations, and social distancing. These factors may not solely be related to infrastructure limitations, but also mistrust in the healthcare system fueled by historical systemic biases. Greater SVI may also lead to poor access to healthcare, significantly impacting outcomes [6]. SVI has also been associated with increased cardiovascular complications and poor outcomes [2]. Furthermore, COVID-19 has been shown to impact outcomes associated with AMI through reluctance of seeking early medical attention, less access to cardioprotective medications, triggering of hyperinflammatory responses, and large infarct sizes [1,7,8].

Our study includes limitations. The cross-sectional design precludes establishing causality due to the absence of a temporal sequence, potential selection bias, and a lack of adjustments for other variables. Use of death certificates to identify causes of death may also be impacted by misclassification biases given the inconsistencies in how they are completed. Furthermore, ecological fallacy remains a possibility as our population-level data may not be extrapolated to individual-level circumstances. Lastly, the lack of individual-level data in the CDC repository limited our analysis, preventing adjustments for personal comorbidities, lifestyle factors, and socioeconomic status, leading to potential residual confounding. For instance, individuals with higher socioeconomic status in areas with greater SVI values may not experience the same elevated mortality rates as those with lower socioeconomic status within the same SVI areas.

The simultaneous burden of COVID-19 in individuals with underlying AMI further complicates the healthcare landscape, increasingly for socially vulnerable populations. Our study highlights the critical need for interventions that are specifically tailored to these populations. Such interventions could include expanding telemedicine services, deploying community health workers, establishing mobile health clinics, and creating robust social support programs. Additionally, the regular reassessment of policy measures aimed at enhancing healthcare accessibility, along with increased funding for community health centers, could play a significant role in reducing social vulnerability and narrowing health disparities across the United States.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval or institutional oversight required for this project. No participant consent required. No conflicts of interest.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ramzi Ibrahim: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Hoang Nhat Pham: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Enkhtsogt Sainbayar: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. João Paulo Ferreira: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

No disclosures.

Data availability

All data are available in the CDC Databases.

References

- 1.Han L., Zhao S., Li S., Gu S., Deng X., Yang L., Ran J. Excess cardiovascular mortality across multiple COVID-19 waves in the United States from March 2020 to March 2022. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023;2:322–333. doi: 10.1038/s44161-023-00220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan S.U., Javed Z., Lone A.N., Dani S.S., Amin Z., Al-Kindi S.G., Virani S.S., Sharma G., Blankstein R., Blaha M.J., et al. Social vulnerability and premature cardiovascular mortality among US counties, 2014 to 2018. Circulation. 2021;144:1272–1279. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.054516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. CDC wonder: multiple cause of death 1999–2018. Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

- 4.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index.Accessed December 6, 2020. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html

- 5.Pozzer A., Dominici F., Haines A., Witt C., Münzel T., Lelieveld J. Regional and global contributions of air pollution to risk of death from COVID-19. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020;116:2247–2253. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson Z.M., Jain V., Chen Y.H., Kayani W., Patel A., Kianoush S., Medhekar A., Khan S.U., George J., Petersen L.A., et al. State-level social vulnerability index and healthcare access in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (from the BRFSS survey) Am. J. Cardiol. 2022;178:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2022.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lechner I., Reindl M., Tiller C., Holzknecht M., Troger F., Fink P., Mayr A., Klug G., Bauer A., Metzler B., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions on ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging study. Eur. Heart J. 2022;43:1141–1153. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Islam S.J., Malla G., Yeh R.W., Quyyumi A.A., Kazi D.S., Tian W., Song Y., Nayak A., Mehta A., Ko Y.A., et al. County-level social vulnerability is associated with in-hospital death and major adverse cardiovascular events in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: an analysis of the American Heart Association COVID-19 cardiovascular disease registry. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2022;15 doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.008612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the CDC Databases.