Abstract

We previously described the construction and analysis of the first set of functional chimeric lentivirus integrases, involving exchange of the N-terminal, central, and C-terminal regions of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and visna virus integrase (IN) proteins. Based on those results, additional HIV-1/visna virus chimeric integrases were designed and purified. Each of the chimeric enzymes was functional in at least one oligonucleotide-based IN assay. Of a total of 12 chimeric IN proteins, 3 exhibit specific viral DNA processing, 9 catalyze insertion of viral DNA ends, 12 can reverse that reaction, and 11 are active for nonspecific alcoholysis. Functional data obtained with the processing assay indicate that the central region of the protein is responsible for viral DNA specificity. Target site selection for nonspecific alcoholysis again mapped to the central domain of IN, confirming our previous data indicating that this region can position nonviral DNA for nucleophilic attack. However, the chimeric proteins created patterns of viral DNA insertion distinct from that of either wild-type IN, suggesting that interactions between regions of IN influence target site selection for viral DNA integration. The results support a new model for the functional organization of IN in which viral DNA initially binds nonspecifically to the C-terminal portion of IN but the catalytic central region of the enzyme has a prominent role both in specific recognition of viral DNA ends and in positioning the host DNA for viral DNA integration.

Following reverse transcription, retroviral integrase (IN) catalyzes two endonuclease events that are necessary for insertion of each end of the newly synthesized viral DNA into an infected cell’s chromosomal DNA. Initially, IN places a nick after invariant CA bases typically found two nucleotides from the 3′ ends of blunt-ended linear viral DNA (33, 56); this sequence-specific reaction is referred to as processing (11, 34). Subsequently, IN inserts the nucleophilic 3′-OH group at each recessed end of the processed viral DNA into staggered sites on host DNA; this cleavage reaction, which is independent of the host DNA sequence, is referred to as DNA joining, strand transfer, or integration (11, 21, 32). Both processing and DNA joining can be mimicked in vitro, using short oligonucleotide substrates designed to resemble the U3 or U5 ends of viral DNA (11, 32, 33). Data from these and related assays have mapped the active site of the enzyme to the central region of IN (8, 13, 18, 43, 45, 47, 64, 68), which contains three highly conserved acidic amino acids that form a D,D-35-E motif (41). However, despite extensive deletion and mutagenesis studies, the portions of the protein that interact with viral DNA and host DNA have not been determined. It had been suggested that the N-terminal region, which has a conserved H-H-C-C motif that binds zinc (6, 8, 41), is responsible for specific interactions with viral DNA (8, 31, 43, 45, 52, 67). In contrast, the C-terminal region, which binds DNA nonspecifically (19, 49, 57, 68, 71, 72), has been an attractive location for sequence-independent interactions with host DNA. In this report, we present further evidence that both of these predictions are wrong.

The ability to form functional chimeras between appropriate wild-type proteins is a powerful and complementary approach to define functional domains. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and visna virus integrases are particularly well suited for domain swapping experiments because they exhibit approximately 30% amino acid identity in each region, show optimal activity under identical in vitro reaction conditions, and yield distinguishable results in reliable assays (36). We previously described the first set of chimeric lentivirus integrases, constructed by exchange of the N-terminal, central, and C-terminal regions of the HIV-1 and visna virus proteins (36). The regions chosen for making the initial chimeras were defined by HIV-1 amino acid residues 1 to 49, 50 to 186, and 187 to 288 (with the caveat discussed below), based on the ability of these regions to functionally complement each other (17) and the ability of an isolated protein fragment representing residues 50 to 186 to catalyze some polynucleotidyl transfer reactions (8). Results obtained with these six chimeric integrases (summarized in Fig. 1, sets b to d) permitted three important observations to be made (36). First, the N-terminal region of IN does not contribute to viral DNA specificity, since a protein with the N-terminal region of HIV-1 IN and the central and C-terminal regions of visna virus IN exhibited the viral DNA specificity of visna virus IN. Second, target site selection with a viral DNA terminus as the nucleophile did not map to regions of IN defined by these boundaries, since chimeric proteins gave novel patterns of strand transfer products. Third, an additional endonuclease activity of IN was discovered. We termed this activity nonspecific alcoholysis because IN was shown to use small nucleophiles such as glycerol to attack any DNA sequence at multiple sites (38). Significantly, target site preferences for nonspecific alcoholysis, which is the most robust activity exhibited by several integrases, clearly mapped to the central region of IN (36, 38).

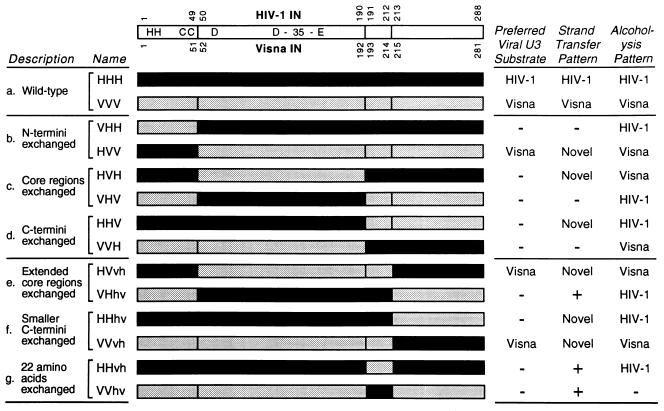

FIG. 1.

HIV-1/visna virus chimeric IN proteins. A linear representation of the IN protein is shown at the top, with the relative positions of the conserved H-H-C-C and D,D-35-E motifs indicated. The numbers above and below the linear map denote positions in the HIV-1 IN and visna virus IN proteins, respectively, that define domains utilized to form the chimeric proteins; note that amino acids 186 to 190 of HIV-1 IN are identical to residues 188 to 192 of visna virus IN. Proteins are presented schematically, with solid bars denoting fragments derived from HIV-1 and stippled bars indicating visna virus sequences. Wild-type and chimeric proteins are grouped in pairs a to g, as indicated under “Description.” Sets b to d are our original six chimeras, named with three uppercase letters. Sets e to f are new chimeras, named with two uppercase letters and two lowercase letters; the second and third letters in this series can be considered an extended core region. The results of various oligonucleotide-based IN assays are summarized at the right, where “Preferred Viral U3 Substrate” refers to processing. −, inactive in that assay; +, active for strand transfer but at too low a level to display a reproducibly discernible pattern.

Since target site selection for nonspecific alcoholysis maps to the central portion of IN, this region must participate in positioning nonviral DNA for nucleophilic attack (the limits for this domain are best defined by residues 50 and 190 because five consecutive amino acids, starting with HIV-1 IN residue 186, are identical in the two wild-type proteins). However, the ability to map target site selection to residues 50 to 190 only when IN utilizes small nucleophiles such as glycerol to attack DNA, but not when the larger viral DNA end is used as the nucleophile, suggests that residues outside numbers 50 to 190 are involved in recognizing or positioning the viral DNA end. For these and other reasons, we expanded the set of HIV-1/visna virus chimeric integrases by producing six new proteins in which the central region would now be defined by amino acid residues 50 to 212. The results map specificity during viral DNA processing, for the first time, to the central region of IN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of IN sequences.

The HIV-1HXB2 IN and visna virus IN coding regions were cloned into plasmid pQE-30 and expressed in Escherichia coli M15[pREP4] (Qiagen, Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.), as described previously (35, 36). Chimeric DNA was produced by the overlap extension PCR method (25), with all overlap primers beginning 3′ to a T to minimize the introduction of errors by any nontemplated addition of a 3′ A (62). Target sequences for amplification were the wild-type HIV-1 IN and visna virus IN cloned into pQE-30. Cassettes encoding HIV-1 IN amino acids 1 to 49 and 1 to 186 were amplified as previously described (36), and cassettes encoding residues 1 to 212, 50 to 212, 187 to 212, and 213 to 288 (Fig. 1) were amplified by the following pairs of primers, respectively: H1 and V3H2*, V1H2 and V3H2*, V2H3 and V3H2*, and V2H3* and H3. Analogous cassettes encoding visna virus IN amino acids 1 to 51 and 1 to 188 were produced as previously described (36), and cassettes encoding residues 1 to 214, 52 to 214, 189 to 214, and 215 to 281 (Fig. 1) were amplified by primer pairs V1 and H3V2*, H1V2 and H3V2*, H2V3 and H3V2*, and H2V3* and V3, respectively. Note that these crossovers correspond to DNA sequences; the resulting protein regions can be described slightly differently because amino acids 186 to 190 of HIV-1 IN are identical to residues 188 to 192 of visna virus IN (36). Sequences for H1, H3, V1, and V3, the outermost primer pairs for HIV-1 IN and visna virus IN sequences, respectively, and for overlap primers that are not named with an asterisk have been published previously (36). Sequences of the new overlap primers were as follows (HIV-1 sequences are in uppercase and visna virus sequences are in lowercase letters): V3H2*, 5′gttttgatttTTCTTTAGTTTGTATGTCTG3′; V2H3*, 5′acagcaacaaagtTTACAAAAACAAATTACAAAAATTC3′; H3V2*, 5′GTTTTTGTAAactttgttgctgtattctttg3′; and H2V3*, 5′ACAAACTAAAGAAaaatcaaaacaagaaaaaattcg3′. Products of the expected length were purified and appropriately mixed in a second round of PCR using the necessary outermost primers to yield full-length chimeras. These products were digested with BglII and SstI and ligated into the BamHI and SstI sites of pQE-30. M15[pREP4] was transformed with the ligation reaction mixtures, and colonies resistant to ampicillin and kanamycin were screened for the presence of insert DNA by restriction endonuclease digestion of plasmid DNA and for induction of IN by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), as described previously (35). The entire IN coding sequence of each construct was determined by dideoxy sequencing to ensure that expressed proteins had the correct amino acid sequence. A total of 31 clones were sequenced to obtain the complete set of 14 proteins shown in Fig. 1.

Expression and purification of integrases.

Proteins were expressed by using the QIAexpress System Type IV construct (Qiagen) and carried 16 extra N-terminal amino acids: Met-Arg-Gly-Ser-(His)6-Gly-Ser-Ile-Glu-Gly-Arg. Culturing, induction by IPTG, and purification of polyhistidine-tagged proteins from the pellets of 250-ml cultures were performed as described previously (36). Because initial purification of the VVhv protein (the nomenclature will be described later) yielded a relatively dilute product, a slightly more concentrated preparation that was purified in the presence of 10 mM 3[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), a zwitterionic detergent, was utilized for all experiments described herein. Purifications were monitored by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), using 12.5% separation gels and 3% stacking gels (acrylamide to methylenebisacrylamide ratio, 37.5:1). Protein concentrations were measured by comparison to Coomassie blue-stained standards, with quantitation by laser densitometry, as described previously (36).

Oligonucleotides.

Sequences of terminal viral DNA 18-mer oligonucleotides and substrates used for the disintegration and alcoholysis assays have been published previously (36, 38). All oligodeoxynucleotides used as assay substrates were gel purified following synthesis and again after being 5′-end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase, as described previously (36). Sequence-specific markers for gel analysis were produced by the 3′-to-5′ exonuclease activity of snake venom phosphodiesterase (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) on 5′-radiolabeled oligonucleotides, as described previously (33).

Processing, strand transfer, alcoholysis, and disintegration assays.

Double-stranded DNA substrates were prepared by annealing the labeled strand with a fourfold excess of unlabeled complementary oligonucleotide, and the disintegration assay substrate was prepared and then purified on a native 15% polyacrylamide gel, both as described previously (35). Standard 10-μl reaction mixtures contained 0.5 to 1.0 pmol of double-stranded DNA or 0.06 pmol of the disintegration assay substrate, 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM MnCl2, and 0.5 to 1.5 μl of IN or protein storage buffer. Alcoholysis assays were conducted in the presence of 40% 1,2-ethanediol (ethylene glycol), which is less viscous than glycerol but yields the same pattern of cleavage products (38). Reaction mixtures were incubated for 90 to 180 min at 37°C, and then reactions were stopped by adding 10 μl of loading buffer (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA, 0.05% bromophenol blue, 0.05% xylene cyanol) and heating at 95°C for 5 min. Aliquots were loaded onto 20% polyacrylamide (acrylamide to methylenebisacrylamide ratio, 19:1)–7 M urea denaturing gels; this was followed by electrophoresis at 75 W until the bromophenol blue dye had migrated 14 to 22 cm. Wet gels were autoradiographed at −80°C. The radioactivity of bands in wet gels was quantified with a Betascope (Betagen, Waltham, Mass.).

RESULTS

Expansion of the set of purified chimeras between HIV-1 and visna virus integrases.

Our initial set of chimeric HIV-1/visna virus integrases had crossovers after HIV-1 IN positions 49 and 190 (the alternative designation of the second crossover was discussed earlier), corresponding to visna virus IN positions 51 and 192, respectively (Fig. 1, sets b to d). We referred to the wild-type proteins as HHH and VVV and to the six chimeras as VHH, HVV, HVH, VHV, HHV, and VVH, where the three letters represent (from left to right) the N-terminal, central, and C-terminal regions, respectively, and H (for HIV-1) or V (for visna virus) indicates the source of that region. As mentioned above, analysis of the activities of these proteins in various oligonucleotide-based assays suggested that residues outside numbers 50 to 190 are involved in recognizing or positioning the viral DNA ends. Since the study of the crystallization of the core region of HIV-1 IN utilized residues 50 to 212 to define this region (15), and because this extended core region shows greater activity in some in vitro assays (8), we decided to create additional chimeric integrases utilizing similar boundaries. In particular, six new chimeric integrases were produced (Fig. 1, sets e to g). The new chimeras all have a crossover after HIV-1 IN position 212, corresponding to visna virus IN position 214 (henceforth, only HIV-1 IN position numbers will be used in this report). To be consistent with our prior nomenclature, the new chimeras are named with uppercase letters for the regions defined by residues 1 to 49 and 50 to 190. In place of the third uppercase letter, two lowercase letters are now used for regions 191 to 212 and 213 to 288, although conceptually residues 191 to 212 should be considered part of an extended central region.

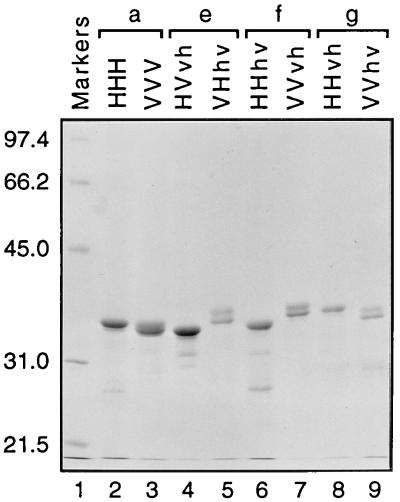

Chimeric DNA was constructed by the method of overlap extension PCR and cloned into a bacterial expression system. Polyhistidine-extended proteins were purified by metal affinity chromatography with a nickel-chelating resin. Each native purification yielded a prominent band on SDS-PAGE gels that migrated to positions appropriate for proteins of approximately 300 amino acids (Fig. 2), although the migration of the different proteins depended on the particular amino acid sequence, as seen with our prior set of chimeric integrases (36). The doublet nature of some of the products is likely due to premature termination or breakdown rather than to contaminating proteins, since similar results were obtained when purifications were performed under denaturing conditions. Densitometric scanning of a gel that included a series of protein standards for calibration indicated that the final concentrations of the purified proteins ranged from 116 ng/μl for VVhv IN (Fig. 2, lane 9) to 591 ng/μl for HVvh IN (lane 4). Thus, each of the proteins was purified to a final concentration of ≥1 pmol/μl, comparable to or exceeding that of other functional integrases (33, 63). For comparison, the wild-type HIV-1 and visna virus integrases had concentrations of 426 and 512 ng/μl, respectively (Fig. 2, lanes 2 and 3).

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE demonstrating purification of new chimeric integrases. Three microliters of each purified IN (indicated above the lanes; nomenclature as in Results) were heated in sample buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was stained with Coomassie blue. Proteins are paired (a, e, f, and g) as in Fig. 1. Molecular mass markers are in lane 1 (sizes are shown in kilodaltons at the left) and represent 200 ng per band.

Demonstration that each new chimeric IN has enzymatic activity.

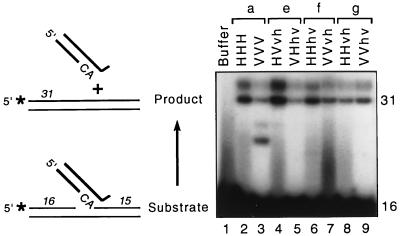

To assess whether the active site in the central region of the protein was maintained in a functional conformation, each chimera was tested for “disintegration” activity (shown schematically in Fig. 3), an in vitro phenomenon that reflects the ability of IN to reverse the strand transfer reaction (10). Of the processing, strand transfer, and disintegration activities of IN, disintegration has the least-stringent requirements for reaction conditions (30) and substrate DNA sequence (10, 59) and is detected even when the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of IN have been deleted (8, 68). The substrate used for this assay is a Y-shaped complex that represents the predicted immediate product of integration of a viral DNA terminus into host DNA. Reversal of the integration reaction yields the processed viral DNA end and a target strand in which the nick has been sealed. Incorporation of a radioactive phosphate at the 5′ end of the nonviral 16-mer in the substrate permits monitoring of this result by detection of a radioactive 31-mer product. This product presumably forms by IN-catalyzed nucleophilic attack of the juxtaposed 3′-OH of the 16-mer at a site just 3′ to the invariant CA of the viral sequence. Each of the six new chimeric integrases was active in this assay, as demonstrated by the appearance of a 31-mer product, whether the viral sequences were derived from HIV-1 (Fig. 3, lanes 4 to 9) or visna virus (data not shown). The doublet nature of the 31-mer product on this gel is likely due to residual secondary structure (10), and bands migrating between the 16- and 31-mer positions may represent breakdown products or reintegration events (67, 68). Although this assay is not able to distinguish between the sources of IN (36), it does demonstrate the integrity of the active site in the catalytic central region of each new chimeric protein.

FIG. 3.

Disintegration activity of new chimeric integrases. (Left) The substrate is a four-oligonucleotide complex representing the predicted immediate adduct of the HIV-1 U5 DNA end (thick lines) integrated into host DNA (thin lines). IN-mediated cleavage after the CA releases the viral DNA end, with concomitant joining of the juxtaposed 5′-radiolabeled 16-mer to the 15 nucleotides beyond the CA to yield a radiolabeled 31-mer product (asterisks denote 32P labels). The substrate was incubated with protein buffer or purified integrases under standard conditions for 90 min and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. (Right) An autoradiogram from a denaturing polyacrylamide gel is shown. The sizes of the labeled component of the substrate and the product are indicated (in nucleotides) at the right, aligned with the complexes at the left from which they were derived. Proteins are paired (a, e, f, and g) as in Fig. 1. The two wild-type integrases and all six new chimeric integrases were active in this assay.

Specific processing activity of new chimeras on terminal viral DNA sequences.

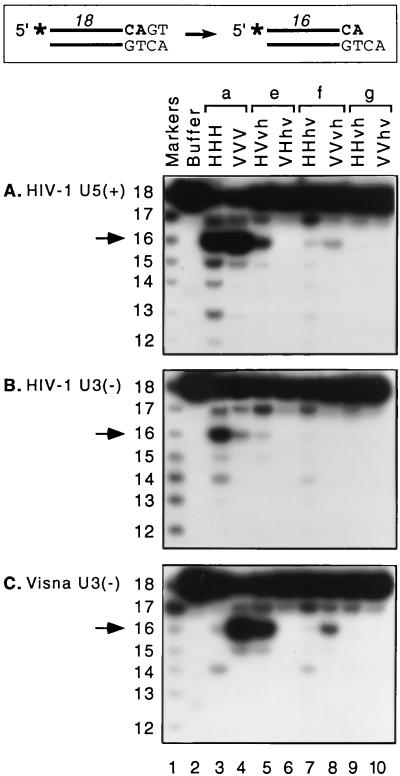

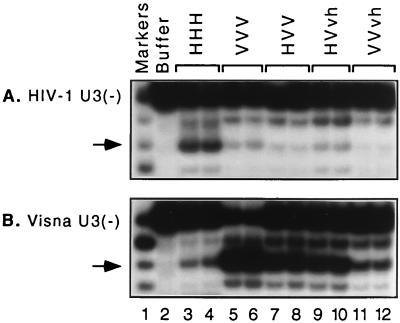

IN specifically removes two nucleotides from the 3′ end of oligonucleotide substrates designed to resemble the termini of viral DNA (shown schematically in Fig. 4) (33). Of the two ends of HIV-1 or visna virus DNA, the HIV-1 U5 terminus provides the most susceptible in vitro substrate for processing by either wild-type IN (36). Our preparations of HIV-1 IN and visna virus IN process approximately 40 and 50% of this substrate, respectively (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 and 4), as determined using a highly reproducible and conservative method to quantify the extent of specific cleavage (37). Thus, assays with the HIV-1 U5 substrate can indicate whether a chimeric protein has any processing activity. In contrast, comparison of processing activities on the two U3 substrates best distinguishes between the HIV-1 and visna virus enzymes (36, 37). In particular, each wild-type IN preferentially cleaves oligonucleotide substrates derived from its own U3 substrate (Fig. 4B and C, lanes 3 and 4).

FIG. 4.

Processing activity of new chimeric integrases. (Top) A schematic of the site-specific 3′-end processing reaction is shown. Cleavage of blunt-ended viral DNA after the invariant CA (shown in boldface) converts a radiolabeled 18-mer to a labeled 16-mer (asterisks denote 32P labels). Duplex oligonucleotide 18-mer substrates derived from the U5 or U3 termini of HIV-1 DNA or the U3 terminus of visna virus DNA and 5′ labeled on the plus or minus strand, as indicated in panels A to C, were incubated with protein buffer or purified integrases under standard conditions for 90 min and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. The region of the autoradiogram extending down to 12-mers is shown to demonstrate the specificity of the reactions. Proteins are paired (a, e, f, and g) as in Fig. 1. Biologically relevant specific cleavage products two nucleotides shorter than the substrate are indicated by arrows. Sequence-specific markers are included in lanes 1, and their sizes (in nucleotides) are indicated at the left.

Two of the six new chimeras exhibited selective cleavage following the CA two nucleotides from the 3′ end of the HIV U5 plus strand: HVvh (Fig. 4A, lane 5) and VVvh (lane 8). These proteins appeared to be more active on visna virus U3 DNA than on HIV-1 U3 DNA (Fig. 4B and C, lanes 5 and 8). To provide confirmation of this observation, we performed duplicate reactions with the two U3 substrates (Fig. 5), using the wild-type HHH and VVV proteins, the HVV protein that was previously shown to exhibit specific processing activity (36), and these two new chimeras (HVvh and VVvh). The autoradiogram shown in Fig. 5 indicates the reproducibility of these results, illustrates the ability of the U3 substrates to distinguish between the wild-type integrases, and demonstrates that each of these three chimeras was more active with the visna virus U3 substrate. Quantification of the results of six replicate reactions (performed on multiple dates) showed that the viral DNA sequence preference of each of these chimeras closely matched that of the wild-type VVV IN and was very different from that of the wild-type HHH IN, as indicated by the ratio of specific cleavage of visna U3 DNA to that of HIV-1 U3 DNA (Table 1).

FIG. 5.

Duplicate processing reactions for informative proteins. Duplex oligonucleotide 18-mer substrates derived from the U3 termini of HIV-1 (A) or visna virus (B) DNA, which best distinguish between the wild-type enzymes, were 5′ radiolabeled on the minus strand and incubated with protein buffer or selected integrases. Details are described in the legend to Fig. 4.

TABLE 1.

Specific processing activity of informative proteins

| IN | Specific cleavage ofa:

|

Ratio of specific cleavagesb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 U3 DNA | Visna virus U3 DNA | ||

| HHH | 13 ± 2 | 4 ± 1 | 0.3 |

| VVV | 5 ± 2 | 55 ± 8 | 11 |

| HVV | 1 ± 0.4 | 31 ± 2 | 31 |

| HVvh | 2 ± 0.2 | 22 ± 2 | 11 |

| VVvh | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 6 ± 2 | 20 |

Duplex substrates were incubated with IN under standard conditions for 90 min and analyzed by denaturing gel electrophoresis, and counts per minute were quantified by Betascope counting. Specific cleavage was calculated by the equation (cpm of 16-mers + cpm of >18-mers)/(total cpm in lane), with background corrections from analogous parts of a negative control lane; >18-mers are products longer than substrate length, which form only following specific cleavage (7, 11, 32). The use of total counts per minute in the denominator best reflects conversion of substrate to specific product but yields lower calculated cleavages than those that would be suggested by comparing 16-mer products with remaining 18-mer substrates. Values are means ± standard deviations for six reactions.

(Specific cleavage of visna virus U3 DNA)/(specific cleavage of HIV-1 U3 DNA).

Each of the three chimeras with processing activity provides important information. As in our prior report (36), the similar preferences of the HVV and VVV proteins indicate that the N-terminal region of IN (equivalent to HIV-1 residues 1 to 49) does not contribute to viral DNA specificity. In addition, since the HVvh chimera has the same substrate preference as the wild-type VVV IN, residues between positions 50 and 212 must be important for viral DNA specificity. Finally, the similar preferences of the VVvh and VVV proteins indicate that the C-terminal region of IN (residues 213 to 288) does not contribute to viral DNA specificity. Taken together, the three informative chimeras provide mutually consistent results: the region of IN responsible for viral DNA specificity is located between residues 50 and 212.

Target site selection using viral DNA termini as the nucleophile to nick DNA.

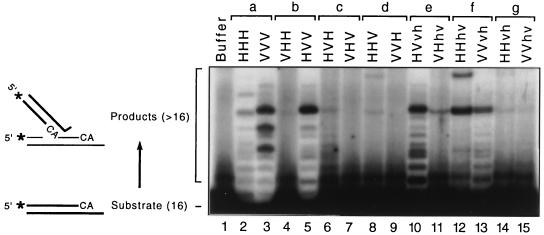

IN catalyzes insertion of the recessed 3′-OH of processed viral DNA ends into various sites along other oligonucleotides that act as surrogates for host DNA to yield a set of labeled integration products that are longer than the substrate (shown schematically in Fig. 6) (11, 32). The patterns of insertion site preferences in this assay, as demonstrated by the autoradiographic locations and intensities of the longer products, distinguish between HIV-1 IN and visna virus IN (36). Thus, purified proteins were tested for strand transfer activity on a preprocessed duplex oligonucleotide substrate derived from the visna virus U3 end, which has been shown to be readily susceptible to both enzymes (36). To facilitate comparisons of the strand transfer patterns, the two wild-type enzymes and the complete set of 12 chimeric proteins were assayed in parallel. The distinctive patterns produced by the wild-type integrases are evident (Fig. 6, lanes 2 and 3). Of the 12 chimeras, 9 had activity in this assay, but only the HVV IN (lane 5) and the HVvh IN (lane 10) had levels of activity comparable to that of wild-type. To display the patterns produced by the other chimeras, severalfold more counts per minute were loaded in the other gel lanes.

FIG. 6.

Strand transfer activity of chimeric integrases. A duplex oligonucleotide derived from the visna virus U3 end, but preprocessed by omission of the final two nucleotides from the minus strand, was used as the substrate for the complete set of 14 purified integrases during 3-h incubations, and reactions were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. An autoradiogram from the upper region of a denaturing polyacrylamide gel is shown. Insertion of the recessed 3′ terminus into various sites along other oligonucleotides (shown as thinner lines in the scheme on the left) yield longer radiolabeled products (asterisks denote 32P labels). The positions of the labeled 16-mer component of the substrate and the labeled strands of longer products are indicated to the left of the gel. Proteins are paired (a to g) as in Fig. 1. The different patterns produced by HHH IN and VVV IN are demonstrated in lanes 2 and 3. Nine of the 12 chimeras had activity in this assay, but ∼5- to 20-fold more counts per minute were loaded in lanes 4, 6 to 9, and 11 to 15 to display the patterns produced by less-active chimeras.

As in our prior study (36), three of the initial six chimeras had activity in this assay: the HVV IN (Fig. 6, lane 5) was very active and had a pattern that did not match that of either wild-type IN, the HVH protein (lane 6) created a faint but novel pattern, and the HHV protein (lane 8) produced a slowly migrating novel band visible near the top of the lane. All of the six new chimeras exhibited strand transfer activity in this assay (lanes 10 to 15). As with the first set of chimeras, none of the new proteins created a pattern that matched that of either wild-type IN. However, inspection of the entire set of strand transfer patterns revealed that the HVV, HVvh, and VVvh proteins (lanes 5, 10, and 13, respectively) created patterns that have in common a major band in the top half of the lane and several less-prominent, faster-migrating bands. These three proteins share the extended core region from visna virus IN (equivalent to HIV-1 IN residues 50 to 212). In addition, the HHhv protein (lane 12) created a novel, slower-migrating band near the top of the lane, similar to that produced by HHV IN (lane 8), which has the same N-terminal 190 amino acids. In some experiments, a similar band also was created by the VHhv and HHvh proteins (seen faintly in lanes 11 and 14).

Similar results were obtained when a longer substrate derived from the HIV-1 U5 terminus was used, as well as with an assay (24, 46) that monitors insertion of unlabeled viral DNA ends into 3′-labeled nonviral DNA (data not shown). In particular, the HVV and HVvh chimeras were very active and created strand transfer patterns that matched neither wild-type IN, although they were similar to each other. In summary, all six of the new chimeras exhibited some strand transfer activity, bringing to nine the number of HIV-1/visna virus chimeras active in this assay. However, each chimera that displayed multiple bands created novel patterns distinct from that of either wild-type IN. The results for all 14 proteins are summarized in Fig. 1.

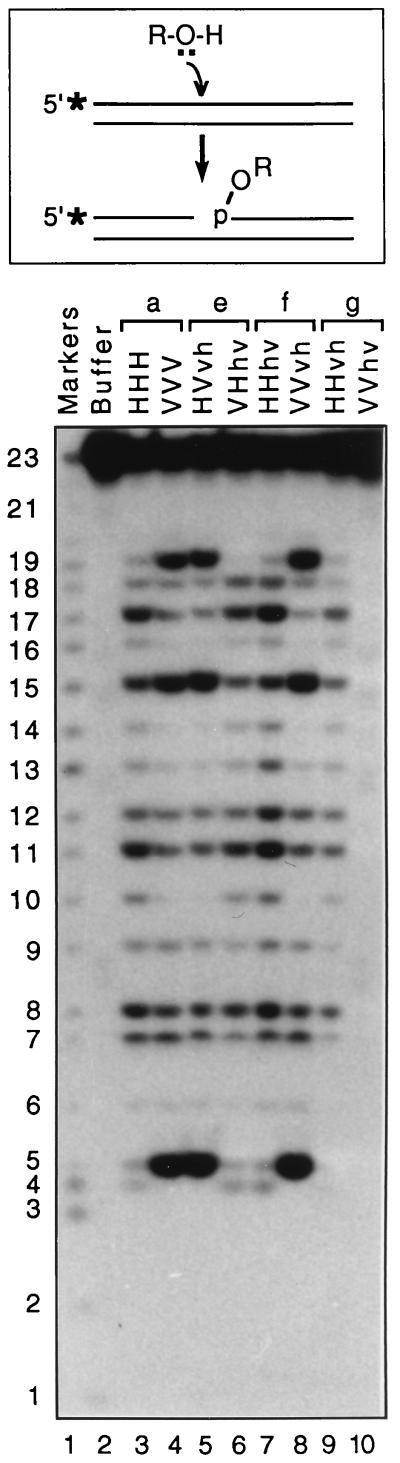

Target site selection using a small alcohol as the nucleophile to nick DNA.

We recently described a fourth enzymatic activity of several retroviral integrases, which we named nonspecific alcoholysis (36, 38). IN was shown to use small nucleophiles, such as glycerol, ethylene glycol, and propylene glycol, to attack nonviral DNA sequences at multiple sites, with concomitant joining of alcohol groups from these nucleophiles to newly exposed 5′ phosphate groups at sites of DNA nicking (shown schematically at the top of Fig. 7). Although every site in DNA substrates except those close to the ends can be nicked by IN in this assay, different integrases exhibit different target site preferences for nonspecific alcoholysis. In particular, HIV-1 IN prefers to nick at sites 17, 15, 11, and 8 nucleotides from the 5′ end of this particular substrate, whereas visna virus IN preferentially cleaves to produce 19-, 15-, and 5-mer products (Fig. 7, lanes 3 and 4). Using our first set of six chimeras, we had previously mapped the outer limits of the region that determines target site selection for this activity to residues 50 and 190 (36).

FIG. 7.

Nonspecific alcoholysis activity of the new chimeric integrases. A schematic of the reaction is shown at the top. IN catalyzes attack by nucleophilic OH groups of various alcohols (ROH) that nick and join to newly exposed 5′ phosphate groups at sites of DNA cleavage (asterisks denote 32P labels). Nicks occur at every site except those close to DNA ends, with a reproducible pattern of preferential sites that is a function of the target DNA sequence and source of IN. A 5′-labeled 23-mer of nonviral sequence was annealed to a complementary oligonucleotide, incubated for 90 min with the wild-type proteins or the new chimeras in the presence of 40% ethylene glycol, and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. A sequence-specific oligonucleotide ladder (as markers) is in lane 1, and sizes (in nucleotides) are indicated at the left. Proteins are paired (a, e, f, and g) as in Fig. 1. Equal volumes of reaction mixtures were loaded so that relative intensities reflect efficiencies of the different proteins. Five of the six chimeras created patterns that segregated clearly to the HHH pattern (chimeras VHhv, HHhv, and HHvh, in lanes 6, 7, and 9, respectively) or to the VVV pattern (chimeras HVvh and VVvh, in lanes 5 and 8, respectively). Chimera VVhv (lane 10) was repeatedly inactive in this assay.

Of the six new chimeras, five were active in this assay, and they created alcoholysis cleavage patterns that precisely matched that of one or the other wild-type IN. The patterns created by chimeras VHhv, HHhv, and HHvh (Fig. 7, lanes 6, 7, and 9, respectively) precisely matched that of wild-type HHH IN (lane 3); since residues 50 to 190 of these proteins are identical, the source of the central region must determine the alcoholysis pattern. Similarly, the cleavage patterns produced by chimeras HVvh and VVvh (Fig. 7, lanes 5 and 8, respectively) were identical to that of wild-type VVV IN (lane 4); residues 50 to 212 (HIV-1 numbering), which are identical in these proteins, encompass the smaller core region of residues 50 to 190 to which this function had already been mapped. Interestingly, the VVhv chimera did not exhibit this activity (Fig. 7, lane 10), despite being very active in the disintegration assay (Fig. 3). This protein is the first to exhibit a discrepancy between nonspecific alcoholysis and disintegration activities, two activities that have been shown to require only the central domain of IN (8, 38, 44, 50). Nonetheless, from the five new chimeras that were active in this assay, we can conclude that target site selection for the nonspecific alcoholysis activity of IN again mapped to the central region of IN, confirming our prior results.

DISCUSSION

Integrase catalyzes insertion of a double-stranded DNA copy of the retroviral genome into host cell chromosomal DNA, contributes to the pathogenesis of AIDS, and is an attractive target for specific antiretroviral therapy. Identification of the regions of IN responsible for viral DNA specificity and for binding target DNA during viral DNA insertion is critical for understanding the organization of the protein, modeling its mechanism of action, and designing inhibitors of its activity. The results described in this report, obtained with an expanded set of functional chimeric lentivirus integrases, have further refined our understanding of the organization of the IN protein.

The region of IN responsible for viral DNA specificity.

Despite early predictions, several lines of evidence indicate that the N-terminal region of IN does not contribute to viral DNA specificity. We previously reported that a chimeric protein with the N-terminal region of HIV-1 IN but the central and C-terminal regions of visna virus preferred the visna virus U3 substrate rather than the HIV-1 U3 substrate in processing assays (36); these two substrates unequivocally distinguish between the wild-type enzymes (36, 37). Similarly, a protein with the N-terminal region of HIV-1 IN but the central and C-terminal regions of human foamy virus IN was reported to process a human foamy virus DNA terminus but not an HIV-1 DNA end (53). Moreover, Rous sarcoma virus, HIV-1, and feline immunodeficiency virus IN proteins with various peptide replacements of the N-terminal region exhibit residual viral DNA processing and strand transfer activity (8, 9, 17, 41, 61).

Further localization of the region of IN responsible for viral DNA specificity has now been accomplished with our expanded set of chimeras, which brings to three the number of chimeric HIV-1/visna virus integrases that have processing activity (Fig. 1 and 5). These proteins provide mutually consistent results: the activity of the HVV protein maps viral DNA specificity to HIV-1 IN residues 50 to 288, the HVvh protein maps this function to residues 50 to 212, and the VVvh protein maps this function to residues 1 to 212 (Table 1). Thus, the region of IN responsible for viral DNA specificity must reside between residues 50 and 212 (HIV-1 numbering). This conclusion is supported by a report that the HIV-1 IN central domain, defined by residues 58 to 201, acts preferentially on cleavage-ligation substrates that contain a CA dinucleotide in an assay designed to mimic the joining of viral DNA 5′ ends to host DNA (whether IN mediates this event in vivo is unknown). The authors concluded that the central domain of IN must play a role in recognition of the CA at the viral DNA terminus (44). Our results extend that observation by mapping viral DNA recognition to the central region of IN by using the established and biologically relevant processing assay. Assignment of viral DNA specificity to the central region does not preclude accessory roles for other parts of IN, either in initial viral DNA binding (see model in Fig. 8) or in protein-protein interactions that facilitate formation of complexes with viral DNA (16).

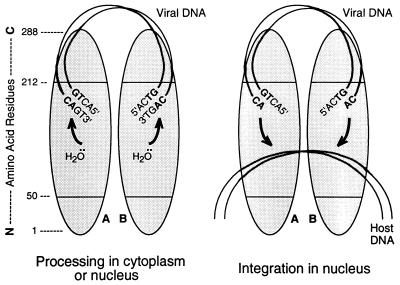

FIG. 8.

Model for the functional organization of the IN protein. Protein monomers A and B (shaded ovals) are shown as a dimer, in parallel orientations, with a linear map of amino acid positions at the extreme left, numbered from the N terminus to the C terminus. Initially (left), viral DNA is bound nonspecifically by the C-terminal region of IN. Amino acids in the central region (perhaps residues 191 to 212) recognize the terminal six positions of the viral DNA sequence (only the final four positions are shown) and position the CA bases for attack by a water molecule that is positioned by the C-terminal portion of the active site (defined by the three invariant acidic amino acids in the central region). The terminal 3′-OH of the viral DNA itself can be used instead of water to release cyclic (GT) dinucleotides (21). In the nucleus (right), host DNA is bound by other portions of the central region of IN. Following a conformational change in the protein, each processed viral DNA end is positioned by the C-terminal portion of the active site, with the aid of the residues responsible for viral DNA recognition and perhaps the C-terminal region, to attack the host DNA. During nonspecific alcoholysis, small alcohols can be used by the active site without requiring residues outside of numbers 50 to 190. The model would accommodate actions occurring in trans or involving multimers larger than dimers.

Identification of particular residues within the central region of IN that are intimately involved in viral DNA recognition awaits further study. We had initially hypothesized that residues 191 to 212 participate in viral DNA recognition, but our data are insufficient to prove or disprove this possibility, since the chimeric proteins that exchanged only these 22 residues did not have processing activity. These poorly soluble proteins were purified at low concentrations relative to the other chimeras (Fig. 2). Perhaps a single-amino-acid substitution of Lys or His for the hydrophobic Phe-185 of HIV-1 IN (corresponding to Ile-187 in visna virus IN) will permit these proteins to be more informative; similar changes increase the solubility of the wild-type HIV-1 IN substantially without disturbing enzymatic activity (20, 26, 28). Other residues in the core domain are also likely to play a role. For example, there is biochemical evidence that Lys-136 and Lys-159 can interact with viral DNA (27, 51). Moreover, recent genetic studies showed that a mutation in simian immunodeficiency virus IN at the position analogous to Lys-136 in HIV-1 IN can compensate for mutations near the viral DNA termini (14).

The region of IN that interacts with host DNA.

Although retroviral integration sites do not exhibit any sequence consensus, in vitro assays reveal preferential sites for viral DNA insertion (9, 55, 60, 63, 70). Nonspecific alcoholysis resembles viral DNA insertion in several respects, including the use of multiple sites, lack of a target site consensus, readily demonstrable cleavage site preferences that are a function of the integrase used, and avoidance of the ends of DNA targets (38). Thus, this activity offers a way to examine interactions between portions of IN and target DNA (36, 38). Our prior set of chimeric integrases mapped the selection of preferred alcoholysis sites to HIV-1 IN residues 50 to 190 (36), and the new chimeras have confirmed that result (Fig. 7). We showed elsewhere that an isolated protein fragment representing the central domain of HIV-1 IN (from residues 50 to 212) could catalyze nonspecific alcoholysis with a pattern of cleavage site preferences identical to that of the full-length protein (38). The same is true for a fragment representing residues 50 to 190 (40). Thus, the central region of IN is sufficient to position nonviral DNA for nucleophilic attack. Given the mechanistic similarities between nonspecific alcoholysis and insertion of viral DNA ends, these data suggest that the central region of IN positions host DNA for retroviral integration. A role for the central region in interactions with host DNA is supported by the finding that mutations of Asn-120 alter the integration site preferences of HIV-2 IN (64).

Given the above-detailed findings, it was surprising that the strand transfer patterns created by our prior set of chimeric integrases did not match that of either wild-type enzyme (36). These observations can be reconciled if the region bounded by residues 50 to 190 is sufficient to position target DNA and small nucleophilic alcohols, such as glycerol, but residues outside of this region are required to position the larger viral DNA terminus when it provides the nucleophilic OH group. To explore this possibility, the new chimeras were designed to have a slightly larger central region, in expectation that the extra amino acids might accommodate the viral DNA terminus. However, the patterns produced by the new chimeras in the oligonucleotide joining assay also failed to match that of either wild-type enzyme (Fig. 1 and 6). Nonetheless, analysis of the full set of 12 chimeric proteins suggests that the extended core domains are major determinants of the strand transfer patterns. In particular, the HVV, HVvh, and VVvh proteins, in which residues 50 to 212 (HIV-1 numbering) are identical, created similar patterns. Why these patterns were not identical and differed from that of the wild-type visna virus IN is unclear. Although the polyhistidine protein extension might influence strand transfer patterns (61), the dichotomy of the nonspecific alcoholysis patterns indicates that any influence of the His tag did not differ for the different proteins. A more likely explanation is that additional residues outside the central domain are involved in protein-protein or protein-DNA interactions that are important for viral DNA insertion but not for DNA cleavage using smaller nucleophiles (1, 3, 26, 48). However, such residues are unlikely to be directly involved in specific viral DNA recognition, based on our mapping of this function with the processing assay.

It should be noted that the oligonucleotide assay may not be optimal for mapping viral DNA insertion, since this assay is significantly less efficient than processing or nonspecific alcoholysis and often provides few bands for analysis. PCR-based assays that detect insertion of viral DNA ends into a plasmid DNA target (42, 55) can reveal a larger set of preferential integration sites and enhance the ability to detect integration activity (22, 60). One group has used such an assay to map target site preferences to an extensive region of HIV-1 IN defined by residues 50 to 234, which contains the central region as well as part of the C-terminal region of IN (22, 60). Our preliminary results with this assay also indicate that a region larger than that defined by residues 50 to 212 may be required to map the patterns of viral DNA insertion (39). However, additional parts of IN are unnecessary for host DNA binding, given the results obtained with the nonspecific alcoholysis assay.

A new working model for the functional organization of IN.

We propose an organization of functional domains on the IN protein that is different from prior models (Fig. 8). The key features are as follows. (i) Newly synthesized viral DNA initially binds in a nonspecific manner to the C-terminal region of IN. This suggestion is based on the nonspecific DNA binding properties of the C-terminal region, the fact that viral DNA is the only DNA present within the preintegration complex, and the ability to map target site selection for small alcohols but not for viral DNA ends to the central region of IN. (ii) Amino acids within the central region of IN (defined by residues 50 to 212) provide specificity by recognizing the viral DNA termini for the two endonuclease events that occur during integration (when viral DNA acts as the specific target for processing and then as the specific nucleophile during insertion). This new assignment is a direct result of the processing data presented here. Whether residues 191 to 212 are responsible for this function, as we initially hypothesized, awaits further evidence. Although Fig. 8 highlights only the final four viral DNA base pairs, we have shown that nucleotides in the fifth and sixth positions play dominant roles in viral DNA recognition (37) and likely interact directly with the part of IN that provides specificity for viral DNA. (iii) Host DNA binds in the central region of IN, as suggested by nonspecific alcoholysis assays. The limits of this site are defined by residues 50 and 190, based on the mapping analysis using chimeras as well as the activity of an isolated protein fragment of IN (40). (iv) Amino acids in the carboxyl half of the active site participate in positioning the nucleophile for catalysis, since residues near Asp-116 and Glu-152 influence the selection of different nucleophiles during processing (65).

The proposed model provides a conceptual framework for viewing the ordered mechanism of action of IN. Significantly, the region that imparts viral DNA specificity should be close to the proposed initial viral DNA binding site in the C-terminal domain and to the active-site residues in the central domain that are involved in positioning the nucleophile for catalysis. Thus, a small conformational change in the protein would allow the viral DNA end to act sequentially as the target for processing and then as the nucleophile for insertion, a major issue in modeling IN function. Viewed in this way, the two catalytic events can be considered a reversal of one mechanism (Fig. 8, arrows). Specificity of the two events would be determined by whether the viral DNA specificity locus or the less specific host DNA binding site acts as the functional target site for catalysis. This spatial arrangement would also explain how the 3′ end of viral DNA occasionally can act as a nucleophile during processing to release cyclic dinucleotide products (21); in this case, the 3′-OH of the viral DNA end would simply substitute for the nucleophilic water molecule (Fig. 8, left scheme).

This working model derives from functional data and must be correlated with structural information. For simplicity of presentation, the protein monomers are shown in parallel orientations in Fig. 8; crystallographic data support this orientation for a dimer of the central regions whose monomers are related by a dyad axis (5, 15). However, the native enzyme may have multiple and complex protein-protein interactions. For example, multidimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy indicates that the C-terminal regions dimerize in an antiparallel orientation (48), and competition studies using a panel of monoclonal antibodies against various parts of HIV-1 IN suggest that the C terminus is in close proximity to both the central domain and the N terminus (4). Furthermore, although the model depicts IN as a dimer in which each active site catalyzes two reactions (58, 67), IN might function in a higher-order complex (1, 3, 12, 17, 23, 26, 28, 29, 54, 73) and each active site might act only once (2, 69). Moreover, complementation between defective IN molecules indicates that reactions can involve the active site on one IN monomer and terminal protein regions of another monomer (17, 61, 66). Finally, we have suggested that residues 191 to 212 might play an important role, yet this region of HIV-1 IN includes an α-helix (positions 196 to 208) that has no clear homology in the oncovirus integrases (2, 15). However, lack of homology does not preclude a similar function, and further testing of this model is under way. Nevertheless, a prominent role for the catalytic central region of IN in positioning host DNA and in specific recognition of viral DNA ends now seems likely.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant R29 AI30759 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and by W. W. Smith Charitable Trust Research grant A9601.

We thank Lynn M. Skinner and Leslie J. Parent for helpful discussions and review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrake M D, Skalka A M. Multimerization determinants reside in both the catalytic core and C terminus of avian sarcoma virus integrase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29299–29306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrake M D, Skalka A M. Retroviral integrase, putting the pieces together. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19633–19636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barsov E V, Huber W E, Marcotrigiano J, Clark P K, Clark A D, Arnold E, Hughes S H. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase by the Fab fragment of a specific monoclonal antibody suggests that different multimerization states are required for different enzymatic functions. J Virol. 1996;70:4484–4494. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4484-4494.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bizub-Bender D, Kulkosky J, Skalka A M. Monoclonal antibodies against HIV type 1 integrase: clues to molecular structure. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:1105–1115. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bujacz G, Jaskolski M, Alexandratos J, Wlodawer A, Merkel G, Katz R A, Skalka A M. High-resolution structure of the catalytic domain of avian sarcoma virus integrase. J Mol Biol. 1995;253:333–346. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke C J, Sanyal G, Bruner M W, Ryan J A, LaFemina R L, Robbins H L, Zeft A S, Middaugh C R, Cordingley M G. Structural implications of spectroscopic characterization of a putative zinc finger peptide from HIV-1 integrase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9639–9644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bushman F D, Craigie R. Activities of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) integration protein in vitro: specific cleavage and integration of HIV DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1339–1343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bushman F D, Engelman A, Palmer I, Wingfield P, Craigie R. Domains of the integrase protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 responsible for polynucleotidyl transfer and zinc binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3428–3432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bushman F D, Wang B. Rous sarcoma virus integrase protein: mapping functions for catalysis and substrate binding. J Virol. 1994;68:2215–2223. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2215-2223.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow S A, Vincent K A, Ellison V, Brown P O. Reversal of integration and DNA splicing mediated by integrase of human immunodeficiency virus. Science. 1992;255:723–726. doi: 10.1126/science.1738845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craigie R, Fujiwara T, Bushman F. The IN protein of Moloney murine leukemia virus processes the viral DNA ends and accomplishes their integration in vitro. Cell. 1990;62:829–837. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90126-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drelich M, Haenggi M, Mous J. Conserved residues Pro-109 and Asp-116 are required for interaction of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase protein with its viral DNA substrate. J Virol. 1993;67:5041–5044. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.5041-5044.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drelich M, Wilhelm R, Mous J. Identification of amino acid residues critical for endonuclease and integration activities of HIV-1 IN protein in vitro. Virology. 1992;188:459–468. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90499-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du Z, Ilyinskii P O, Lally K, Desrosiers R C, Engelman A. A mutation in integrase can compensate for mutations in the simian immunodeficiency virus att site. J Virol. 1997;71:8124–8132. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8124-8132.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyda F, Hickman A B, Jenkins T M, Engelman A, Craigie R, Davies D R. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of HIV-1 integrase: similarity to other polynucleotidyl transferases. Science. 1994;266:1981–1986. doi: 10.1126/science.7801124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellison V, Gerton J, Vincent K A, Brown P O. An essential interaction between distinct domains of HIV-1 integrase mediates assembly of the active multimer. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3320–3326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engelman A, Bushman F D, Craigie R. Identification of discrete functional domains of HIV-1 integrase and their organization within an active multimeric complex. EMBO J. 1993;12:3269–3275. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05996.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engelman A, Craigie R. Identification of conserved amino acid residues critical for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase function in vitro. J Virol. 1992;66:6361–6369. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6361-6369.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engelman A, Hickman A B, Craigie R. The core and carboxyl-terminal domains of the integrase protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 each contribute to nonspecific DNA binding. J Virol. 1994;68:5911–5917. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5911-5917.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelman A, Liu Y, Chen H, Farzan M, Dyda F. Structure-based mutagenesis of the catalytic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J Virol. 1997;71:3507–3514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3507-3514.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engelman A, Mizuuchi K, Craigie R. HIV-1 DNA integration: mechanism of viral DNA cleavage and DNA strand transfer. Cell. 1991;67:1211–1221. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90297-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goulaouic H, Chow S A. Directed integration of viral DNA mediated by fusion proteins consisting of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase and Escherichia coli LexA protein. J Virol. 1996;70:37–46. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.37-46.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hazuda D J, Wolfe A L, Hastings J C, Robbins H L, Graham P L, LaFemina R L, Emini E A. Viral long terminal repeat substrate binding characteristics of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3999–4004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong T, Murphy E, Groarke J, Drlica K. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA integration: fine structure target analysis using synthetic oligonucleotides. J Virol. 1993;67:1127–1131. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.1127-1131.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horton R M, Ho S N, Pullen J K, Hunt H D, Cai Z, Pease L R. Gene splicing by overlap extension. Methods Enzymol. 1993;217:270–279. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)17067-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkins T M, Engelman A, Ghirlando R, Craigie R. A soluble active mutant of HIV-1 integrase: involvement of both the core and carboxyl-terminal domains in multimerization. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7712–7718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkins, T. M., D. Esposito, A. Engelman, and R. Craigie. 1997. Personal communication.

- 28.Jenkins T M, Hickman A B, Dyda F, Ghirlando R, Davies D R, Craigie R. Catalytic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase: identification of a soluble mutant by systematic replacement of hydrophobic residues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6057–6061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.6057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones K S, Coleman J, Merkel G W, Laue T M, Skalka A M. Retroviral integrase functions as a multimer and can turn over catalytically. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16037–16040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jonsson C B, Donzella G A, Roth M J. Characterization of the forward and reverse integration reactions of the Moloney murine leukemia virus integrase protein purified from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1462–1469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jonsson C B, Roth M J. Role of the His-Cys finger of Moloney murine leukemia virus integrase protein in integration and disintegration. J Virol. 1993;67:5562–5571. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5562-5571.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz R A, Merkel G, Kulkosky J, Leis J, Skalka A M. The avian retroviral IN protein is both necessary and sufficient for integrative recombination in vitro. Cell. 1990;63:87–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90290-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katzman M, Katz R A, Skalka A M, Leis J. The avian retroviral integration protein cleaves the terminal sequences of linear viral DNA at the in vivo sites of integration. J Virol. 1989;63:5319–5327. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5319-5327.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katzman M, Mack J P G, Skalka A M, Leis J. A covalent complex between retroviral integrase and nicked substrate DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4695–4699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katzman M, Sudol M. In vitro activities of purified visna virus integrase. J Virol. 1994;68:3558–3569. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3558-3569.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katzman M, Sudol M. Mapping domains of retroviral integrase responsible for viral DNA specificity and target site selection by analysis of chimeras between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and visna virus integrases. J Virol. 1995;69:5687–5696. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5687-5696.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katzman M, Sudol M. Influence of subterminal viral DNA nucleotides on differential susceptibility to cleavage by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and visna virus integrases. J Virol. 1996;70:9069–9073. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.9069-9073.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katzman M, Sudol M. Nonspecific alcoholysis, a novel endonuclease activity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and other retroviral integrases. J Virol. 1996;70:2598–2604. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2598-2604.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katzman, M., M. Sudol, and J. S. Pufnock. 1997. Unpublished data.

- 40.Katzman, M., M. Sudol, L. M. Skinner, and A. L. Morgan. 1997. Unpublished data.

- 41.Khan E, Mack J P G, Katz R A, Kulkosky J, Skalka A M. Retroviral integrase domains: DNA binding and the recognition of LTR sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:851–860. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.4.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kitamura Y, Lee Y M H, Coffin J M. Nonrandom integration of retroviral DNA in vitro: effect of CpG methylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5532–5536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kulkosky J, Jones K S, Katz R A, Mack J P G, Skalka A M. Residues critical for retroviral integrative recombination in a region that is highly conserved among retroviral/retrotransposon integrases and bacterial insertion sequence transposases. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2331–2338. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kulkosky J, Katz R A, Merkel G, Skalka A M. Activities and substrate specificity of the evolutionarily conserved central domain of retroviral integrase. Virology. 1995;206:448–456. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.LaFemina R L, Schneider C L, Robbins H L, Callahan P L, LeGrow K, Roth E, Schleif W A, Emini E A. Requirement of active human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase enzyme for productive infection of human T-lymphoid cells. J Virol. 1992;66:7414–7419. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7414-7419.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leavitt A D, Rose R B, Varmus H E. Both substrate and target oligonucleotide sequences affect in vitro integration mediated by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase protein produced in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Virol. 1992;66:2359–2368. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2359-2368.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leavitt A D, Shiue L, Varmus H E. Site-directed mutagenesis of HIV-1 integrase demonstrates differential effects on integrase functions in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2113–2119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lodi P J, Ernst J A, Kuszewski J, Hickman A B, Engelman A, Craigie R, Clore G M, Gronenborn A M. Solution structure of the DNA binding domain of HIV-1 integrase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9826–9833. doi: 10.1021/bi00031a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lutzke R A, Vink C, Plasterk R H A. Characterization of the minimal DNA-binding domain of the HIV integrase protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4125–4131. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.20.4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mazumder A, Engelman A, Craigie R, Fesen M, Pommier Y. Intermolecular disintegration and intramolecular strand transfer activities of wild-type and mutant HIV-1 integrase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1037–1043. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mazumder A, Neamati N, Pilon A A, Sunder S, Pommier Y. Chemical trapping of ternary complexes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase, divalent metal, and DNA substrates containing an abasic site: implications for the role of lysine 136 in DNA binding. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27330–27338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mizuuchi K. Transpositional recombination: mechanistic insights from studies of Mu and other elements. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:1011–1051. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.005051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pahl A, Flugel R M. Characterization of the human spuma retrovirus integrase by site-directed mutagenesis, by complementation analysis, and by swapping the zinc finger domain of HIV-1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2957–2966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pemberton I K, Buckle M, Buc H. The metal ion-induced cooperative binding of HIV-1 integrase to DNA exhibits a marked preference for Mn(II) rather than Mg(II) J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1498–1506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pryciak P M, Varmus H E. Nucleosomes, DNA-binding proteins, and DNA sequence modulate retroviral integration target site selection. Cell. 1992;69:769–780. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90289-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roth M J, Schwartzberg P L, Goff S P. Structure of the termini of DNA intermediates in the integration of retroviral DNA: dependence on IN function and terminal DNA sequence. Cell. 1989;58:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schauer M, Billich A. The N-terminal region of HIV-1 integrase is required for integration activity, but not for DNA binding. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;185:874–880. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91708-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scottoline B P, Chow S, Ellison V, Brown P O. Disruption of the terminal base pairs of retroviral DNA during integration. Genes Dev. 1997;11:371–382. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sherman P A, Dickson M L, Fyfe J A. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integration protein: DNA sequence requirements for cleaving and joining reactions. J Virol. 1992;66:3593–3601. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3593-3601.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shibagaki Y, Chow S A. Central core domain of retroviral integrase is responsible for target site selection. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8361–8369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shibagaki Y, Holmes M L, Appa R S, Chow S A. Characterization of feline immunodeficiency virus integrase and analysis of functional domains. Virology. 1997;230:1–10. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith K D, Valenzuela A, Vigna J L, Aalbers K, Lutz C T. Unwanted mutations in PCR mutagenesis: avoiding the predictable. PCR Methods Applic. 1985;2:253–257. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Gent D C, Elgersma Y, Bolk M W J, Vink C, Plasterk R H A. DNA binding properties of the integrase proteins of human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3821–3827. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Gent D C, Oude Groeneger A A M, Plasterk R H A. Mutational analysis of the integrase protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9598–9602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Gent D C, Oude Groeneger A A M, Plasterk R H A. Identification of amino acids in HIV-2 integrase involved in site-specific hydrolysis and alcoholysis of viral DNA termini. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3373–3377. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.15.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Gent D C, Vink C, Oude Groeneger A A M, Plasterk R H A. Complementation between HIV integrase proteins mutated in different domains. EMBO J. 1993;12:3261–3267. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vincent K A, Ellison V, Chow S A, Brown P O. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase expressed in Escherichia coli and analysis of variants with amino-terminal mutations. J Virol. 1993;67:425–437. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.425-437.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vink C, Oude Groeneger A A M, Plasterk R H A. Identification of the catalytic and DNA-binding region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1419–1425. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.6.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vink C, Plasterk R H A. The human immunodeficiency virus integrase protein. Trends Genet. 1993;9:433–437. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90107-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vink C, van der Linden K H, Plasterk R H A. Activities of the feline immunodeficiency virus integrase protein produced in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1994;68:1468–1474. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1468-1474.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Woerner A M, Klutch M, Levin J G, Marcus-Sekura C J. Localization of DNA binding activity of HIV-1 integrase to the C-terminal half of the protein. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:297–304. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Woerner A M, Marcus-Sekura C J. Characterization of a DNA binding domain in the C-terminus of HIV-1 integrase by deletion mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3507–3511. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.15.3507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wolfe A L, Felock P J, Hastings J C, Uncapher Blau C, Hazuda D J. The role of manganese in promoting multimerization and assembly of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase as a catalytically active complex on immobilized long terminal repeat substrates. J Virol. 1996;70:1424–1432. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1424-1432.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]