Abstract

Background:

Immigrants to Canada count among the socially disadvantaged groups experiencing higher rates of oral disease. Culturally competent oral health care providers (OHCPs) stand to be allies for immigrant oral health. The literature reveals limited knowledge of practising OHCPs’ cultural competency, and little synthesis of the topic has been completed. A scoping review is warranted to identify and map current knowledge of OHCPs’ understanding of culturally competent care along with barriers and facilitators to developing capacity.

Methods:

This study was conducted between December 2022 and April 2023 using Arksey and O’Malley’s 5-step framework and PRISMA-ScR checklist. Four databases were searched using keywords related to 4 themes: population, provider, oral health, and cultural competence. Peer-reviewed articles published in English in the last 10 years were included.

Results:

Search results yielded 74 articles. Title and abstract review was completed and an author-developed critical appraisal tool was applied. Forty-six (46) articles were subject to full-text review and 14 met eligibility criteria: 7 qualitative and 7 quantitative. Six barriers and six facilitators at individual and systemic levels were identified, affecting oral care for immigrants and providers’ ability to work cross-culturally.

Discussion:

Lack of cultural or linguistically appropriate resources, guidance, and structural supports were identified as contributing to low utilization of services and to lack of familiarity between providers and immigrants.

Conclusion:

OHCPs’ cultural competency development is required to improve oral health care access and outcomes for diverse populations. Further research is warranted to identify factors impeding OHCPs’ capacity to provide culturally sensitive care. Intentional policy development and knowledge mobilization are needed.

Keywords: cultural competency, dental hygienist, dentist, health equity, health services accessibility, immigrants, newcomer, oral health, oral health care provider

Abstract

Contexte :

Les immigrants au Canada comptent parmi les groupes socialement défavorisés qui connaissent des taux plus élevés de maladies buccodentaires. Les fournisseurs de soins buccodentaires culturellement adaptés sont des alliés pour la santé buccodentaire des immigrants. La documentation révèle une connaissance limitée de la compétence culturelle des fournisseurs de soins buccodentaires en pratique, et peu de synthèse du sujet a été effectuée. Un examen de la portée est nécessaire pour déterminer et mettre en correspondance les connaissances actuelles des fournisseurs de soins buccodentaires sur la compréhension des soins culturellement adaptés ainsi que les obstacles et les facteurs favorables au renforcement des capacités.

Méthodes :

Cette étude a été menée entre décembre 2022 et avril 2023 à l’aide du cadre en 5 étapes d’Arksey et O’Malley et de la liste de vérification PRISMA-SCr. Pour ce faire, 4 bases de données ont été consultées à l’aide de mots clés liés à 4 thèmes : population, fournisseur, santé buccodentaire et compétence culturelle. Les articles évalués par les pairs publiés en anglais au cours des 10 dernières années ont été inclus.

Résultats :

La recherche a rapporté 74 articles. Un examen des titres et des résumés a été effectué et un outil d’évaluation critique élaboré par l’auteur a été utilisé. En tout, 46 articles ont fait l’objet d’un examen du texte intégral et 14 répondaient aux critères d’admissibilité : 7 qualitatifs et 7 quantitatifs. À partir de ces articles, 6 obstacles et 6 facteurs favorables aux niveaux individuel et systémique ont été cernés; ceux-ci ont un effet sur les soins buccodentaires des immigrants et à la capacité des fournisseurs de travailler de façon interculturelle.

Discussion :

Le manque de ressources, d’orientation et de soutien structurel culturellement ou linguistiquement appropriés a été identifié comme contribuant à une faible utilisation des services et à un manque de familiarité entre les fournisseurs et les immigrants.

Conclusion :

Le perfectionnement des compétences culturelles des fournisseurs de soins buccodentaires est nécessaire pour améliorer l’accès aux soins de santé buccodentaire et les résultats pour diverses populations. D’autres recherches sont nécessaires pour cerner les facteurs qui nuisent à la capacité des fournisseurs de soins buccodentaires de fournir des soins adaptés à la culture. L’élaboration délibérée de politiques et la mobilisation des connaissances sont nécessaires.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THIS RESEARCH.

Limited primary research is available on cultural competence capacity of practising OHCPs in Canada.

Immigrants face both personal and systemic barriers that limit access to appropriate oral health care services and hinder OHCPs’ understanding of diverse cultural needs.

Developing OHCPs’ comfort and knowledge in treating an increasingly culturally diverse population is contingent on policy development and mobilization through strategic multiagency and interdisciplinary health care networks.

INTRODUCTION

The Canadian population is on the rise, owing largely to increasing numbers of new immigrants. According to the 2022 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration, Canada saw the highest annual number of immigrants in the country’s history, with almost 406,000 arrivals that year.1 Data from 2021 show that immigrants represent 23% of the Canadian population, accounting for more than 8.3 million people and that, by 2041, the immigrant population will represent up to 34% of Canada’s population.2

Reasons for immigration to Canada are multifactorial; of immigrants who have settled in Canada since 2016, 36.6% were admitted under temporary work or study permits or as asylum claimants.2 Increases in immigration to Canada have most recently been provoked by global conflict and asylum seeking.3 Immigrants are defined as those who have settled permanently in another country by personal choice. The terms “refugee claimant” and “asylum seeker” are often used interchangeably to describe persons who are seeking protection and safety in a country other than their country of origin owing to substantiated fears of harm or racial, religious, social or political persecution in their home country.4 Upon arrival, immigrants and refugees often have minimal social supports within their new country, creating challenges in navigating basic services such as health care systems.5 Additionally, lengthy and interrupted travel routes mean many have gone without appropriate health care for extended periods.6, 7 In addition to poor systemic disease management and comorbidities, newcomers to Canada experience poor oral health.8–10

Higher rates of oral disease, including periodontitis, caries, and missing or broken teeth, are found in the immigrant and refugee populations compared to the general North American populace.11–14 Immigrant children exhibit higher dmft (decayed, missing or filled teeth) scores and higher rates of caries compared to non-immigrant children; similar differences in DMFT have been reported between immigrant and non-immigrant adults.12, 15, 16 The proportion of untreated caries was also found to be higher among immigrant and refugee populations in Canada.16 This situation suggests that, in addition to higher rates of decay, immigrant populations may also receive less treatment for their oral conditions.

Culture, race, and ethnicity are social determinants with major influence on individual perceptions and understanding of health.5, 17 Acculturation is defined as the complex, dynamic process through which beliefs, values, attitudes, and behaviours of a minority group change to become aligned and integrated with those of the majority group.18 It has been shown that immigrants often self-assess their oral health as high upon arrival, and then comparatively lower after receiving care in Canada.19, 20 While this shift in perception is often attributed to positive impacts of acculturation, including increased health education and integration into Canadian society, the prevalence of oral disease among immigrants may also reflect the challenges immigrants face in accessing the oral health care they need.20

Contributing to the poor oral health status of immigrants to Canada are barriers that limit access to oral health care and utilization of available oral health services.8 Barriers widely reported in the literature include language, literacy levels, and cultural norms.14, 21–23 Socioeconomic conditions such as housing insecurity, low employment, and income also affect the ability of immigrants to access care.8, 22, 24 Thirty-three percent (33%) of immigrants reported not visiting the dentist in the past year and 25% reported visiting only for emergencies.25 In comparison to the general Canadian populace, immigrants also typically receive fewer preventive services and more treatment for existing disease.26 Current trends in Canadian emergency room visits reflect the significance of these challenges on not only individual health, but that of the public health care system. Concerningly, the increased frequency with which emergency departments are being accessed for dental emergencies has been identified as a stressor to an already overburdened health care system.27 Treatment of oral diseases by emergency room physicians forced to work beyond their scope of practice has been identified as a contributor to oral disease mismanagement and a growing over-reliance on antibiotic prescriptions to alleviate symptoms of often preventable oral conditions.28 Socially disadvantaged groups including immigrants are reported to access this form of emergency care more often, indicating that increased education on preventive care options is warranted.26, 28

Oral health care providers (OHCPs) are poised to bridge this gap as leaders in prevention and oral health education. For OHCPs to become allies for immigrant oral health, they must be equipped with appropriate knowledge of cultural differences and culturally safe care practices. Cultural competence is framed as a set of attitudes, skills, and communication abilities that equip care providers to work effectively with diverse populations and adapt care services to meet the sociocultural and linguistic needs of individuals.29, 30 Although the concept of developing “cultural competency” has faced scrutiny in recent years, a contemporary definition of the term has been proposed, emphasizing it as a process of continual learning and self-reflection to gain deeper understanding of other cultures, values, and health beliefs that will enable culturally appropriate and sensitive care. This definition replaces outdated interpretations of the term, which alluded to an ability to “master” working with other cultures through skills development.31, 32 For OHCPs, developing personal and professional capacity for culturally competent care involves exposure to events and experiences that foster improved understanding of cultural differences, values, and perceived barriers to care that will strengthen individual and team efforts in improving oral care delivery.33 Development of cultural competency stands to improve both immigrant utilization of oral health care services and oral and overall health outcomes.34, 35 The announcement of funding for a national dental care plan in Canada responds to this urgent need.36, 37 Indeed, the introduction of a targeted dental care plan for low- to middle-income households is poised to fundamentally change the landscape of oral health care in this country, increasing opportunities for underserved populations, including immigrants, to better access oral health services.

Improved understanding of OHCPs cultural competence capacity may reveal where gaps in knowledge, policy, and practice exist—an important step in developing a system in which immigrant and refugee populations have equitable access to care. Currently, there is limited knowledge of self-assessed cultural competency of OHCPs and limited evidence to inform how capacity building may impact the oral health of immigrants. Also unknown are the most effective approaches for increasing cultural competency. Research on providers’ current knowledge of cultural competence is essential to guide understanding of their ethical responsibilities in providing equitable care to all patients.

A review of the literature shows that current understanding of OHCPs’ cultural competence is largely reliant on secondary research, and little synthesis of this topic has been done. This study aims to identify and analyse the current knowledge of OHCPs’ understanding of culturally competent care, along with barriers and facilitators to developing cultural competence capacity.

METHODS

Identifying the research question

A scoping review was conducted to synthesize literature relevant to assessing OHCPs’ cultural competence capacity. Arksey and O’Malley’s 5-stage methodological framework was followed to conduct this search.38 The 5 steps are as follows: 1) identifying the research question; 2) identifying relevant studies; 3) study selection; 4) charting the data; and 5) summarizing and reporting results.38 The PRISMA-ScR checklist for reporting scoping reviews was also followed to direct the authors’ reporting methodology.39 The review was guided by 2 questions:

What factors impact current knowledge of culturally competent care among OHCPs?

What are the barriers and facilitators to developing providers’ cultural competency and what is their significance to immigrant oral health care utilization?

Search strategies

Four electronic databases—PubMed, CINAHL, ProQuest, and EMBASE—were selected for this review conducted between December 2022 and April 2023. Terms selected for this search covered 4 main themes: population, provider, oral health, and cultural competence. Keywords that fit within these 4 themes were identified and further refined for each database. The search terms associated with each theme are shown in Table 1. For databases that use controlled vocabulary indexes (PubMed, EMBASE, and CINAHL), additional identifiers were used to search indexing tags. The Boolean operator of “and” was used between main theme terms and “or” between related keywords within themes to yield maximum results.

Identifying relevant studies

The boundaries of this review were defined by inclusion and exclusion criteria applied across all databases. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: peer-reviewed journal articles, published in the past 10 years, in English, with a focus on oral health care providers or care provision to immigrants by general health care providers. Grey literature from reputable sources was also eligible for inclusion to source credible material that could inform the research questions. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Search term strategy

|

Main theme |

Search terms |

|

Population |

Immigrant, refugeea, newcomera, asylum seekera, migranta |

|

Provider |

Oral health care provider, dentistb, dental hygienistb, dental professionalb, dental therapistb |

|

Oral health |

Oral health, dental care, oral disease, mouth disease, dental disease, tooth disease, periodontal disease, gum disease, caries, tooth decay |

|

Cultural competence |

Cultural competency, culturally competent care, acculturation, access to care |

aVariation on the term “immigrant”

bVariation on the term “oral health care provider”

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for database search

|

Inclusion criteria |

Exclusion criteria |

|

<10 years |

>10 years |

|

English |

Non-English |

|

Peer-reviewed or reputable grey literaturea |

Non-reputable sources |

|

Literature pertaining to oral/health care providers’ treatment of immigrant populations |

Literature pertaining to oral health care provider trainees/students |

aReputable grey literature is defined by the authors as non-peer reviewed sources published outside of academia. Sources agreed upon by the authors as reputable included government and health organization websites, documents, reports, clinical practice guidelines, theses, and conference abstracts.

While OHCPs were the target population of this research, literature that focused on the cultural competency of health care providers (HCPs) in their treatment of immigrant populations was reviewed to inform the gap in knowledge specific to OHCPs. However, literature focusing on OHCP students or trainees was excluded given the volume of literature on students’ cultural competence development related to experiences working with diverse populations in controlled, service-learning settings. There is little knowledge specific to cultural competency of actively practising OHCPs, establishing the focus and rationale for this review. The article by Doucette et al.40 was included owing to its focus on communication challenges and the relationship between immigrant care access and interpreters.

Publications that met eligibility criteria were retrieved and article tracking software (Covidence) was used during the screening process. Following elimination of duplicate publications, remaining articles were screened independently for title and abstract relevance by 2 authors (ED and JJ) trained in electronic database searching and literature content appraisal. Studies were considered relevant if the population included immigrants or OHCPs/HCPs and if the research focus included assessment of care or personal valuation of care providers’ cul,tural competency. The 2 authors met to review articles screened; any conflicts were discussed until a consensus was reached on articles for full-text review.

Charting the data

Full-text review was independently completed by all 3 authors (LVD, ED, and JJ) using a critical appraisal tool developed by the team for calibration (Supplementary Table S1). Finally, collaborative discussion was held among all authors to reconcile any conflicting interpretations until agreement was reached on articles for inclusion. Bibliographic citations for articles selected were imported into a shared citation management library (Zotero) and articles were organized into a summary table.

Summarizing and reporting results

General characteristics of articles retrieved were recorded in table format documenting author names/year, country of study, aims/purpose, study population and sample, methodology/intervention, key findings, and any gaps in research noted (Table 3).

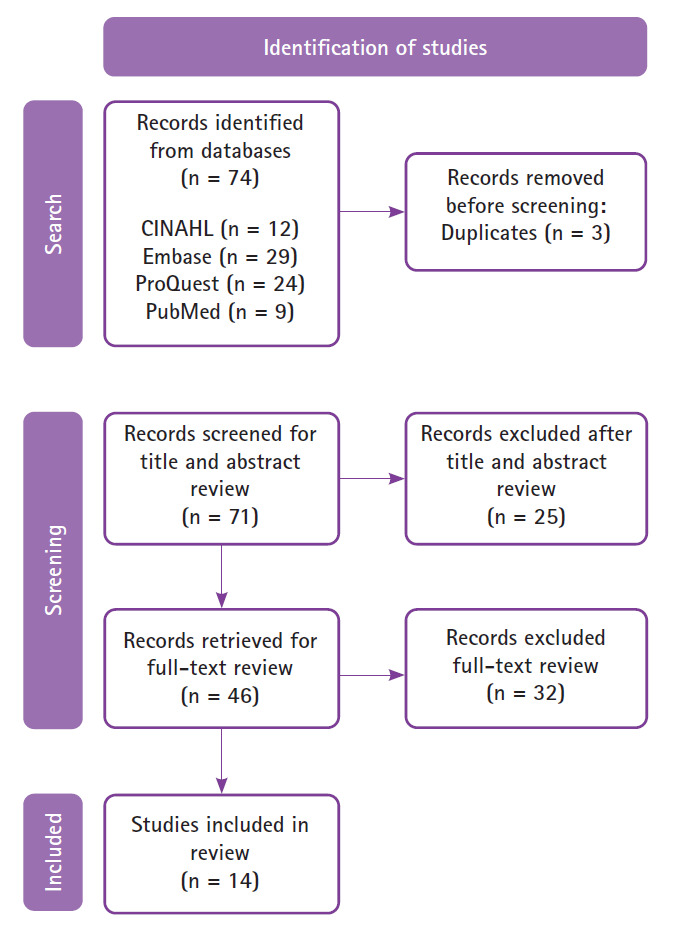

RESULTS

Database search identified 74 articles for review. After duplicates were removed (n = 3), 71 records were screened for title and abstract and 25 were excluded for failing to meet inclusion criteria. Forty-six (46) articles were subject to full-text review; 14 articles satisfied inclusion criteria and were selected for data extraction and synthesis. Seven qualitative studies employing focus groups, interviews, and interpretative and community-based participatory analysis were selected, along with 7 quantitative studies that used cross-sectional surveys and longitudinal cohort analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the literature search and review process.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of search and screening process

Thematic analysis

All authors independently reviewed articles for emergent themes and subsequently met as a team to review and discuss themes identified until consensus was reached. Within the selected articles, broad themes emerged related to the complexities of providing effective oral and overall health care to immigrant populations.

A major theme in 6 studies was that health care providers felt unprepared to deliver effective care cross-culturally.29, 40–44 The role of language interpreters has been widely reported in the literature, and studies in this review tied interpreters to themes of effective health education and communication within the patient–provider relationship.20, 29, 40, 41, 45 These studies suggest that current care models lacking the appropriate resources for effective patient–provider communication may prevent culturally competent care from being delivered.

Selected articles were also reviewed for common barriers and facilitators that impact the ability of immigrants to access care and the ways these factors impact the cultural competence of care providers and capacity of care systems to deliver quality culturally sensitive care.

Table 3.

General characteristics of studies selected

|

Study authors, year, country |

Aims/purpose |

Study population Sample size |

Methodology/ Intervention |

Key findings |

Gaps in research noted |

|

Van Midde et al. (2020)47 The Netherlands |

Explored the accessibility of voluntary dental services for undocumented migrants |

Refugees & migrants 21 |

Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

Voluntary dental care improved accessibility of oral health services for undocumented migrants. However, both migrants and dentists involved were unsatisfied with the treatment results as the level of care delivered varied widely owing to resource limitations and cultural differences. |

N/A |

|

Calvasina et al. (2015)19 Canada |

Identified self-reported barriers to oral health care among settled immigrants in Canada over a 4-year period. |

Immigrants 3976 |

Quantitative Longitudinal cohort study |

Poor oral health and barriers to care are identified as being linked to sex, low employment and income, and self-perceived discrimination. The findings support the need for policy development to improve access to dental care. Strategies that also address poverty and psychosocial stressors experienced by immigrants are crucial. |

Data on immigrants’ self-reported oral health are limited; more research from the perspective of immigrants is needed to better understand barriers to oral health and impacts of resettlement. |

|

Karnaki et al. (2022)46 Europe |

Investigated the determinants of health that influence migrants’ and refugees’ ability to access dental care. |

Refugees & migrants 1407 |

Quantitative Cross-sectional survey design |

Migrants with higher educational levels, lower age, lower sense of discrimination, and better general and mental health were found to have greater access to dental care services and improved oral health outcomes. |

Future studies could aim to investigate the impact of acculturation on diet and the dental caries prevalence and oral health status of migrants living in different settings. |

|

Charbonneau et al. (2014)41 Canada |

Investigated the experiences of dental hygienists practising in multicultural societies |

Dental hygienists 5 |

Qualitative interpretative analysis Focus group |

There is a minimal collective understanding of the details associated with culturally competent care among practising dental hygienists. Findings support the need for structured educational sessions on culturally competent care. |

Future research could focus on providing insights into the most effective manner to teach and impart information on culturally competent care for oral health providers. |

|

Paisi et al. (2022)42 England |

Investigated factors involved in dictating access to dental services and oral health behaviours of asylum seekers and refugees |

Oral health care providers 12 |

Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

Described appropriate health promotion techniques that can be implemented to address identified barriers to dental care. Initiatives suggested include providing linguistically appropriate preventive oral health education and training for health professionals to improve their ability to develop meaningful patient connections and promote effective care. |

N/A |

|

Calvasina et al. (2014)9 Canada |

Examined the predictors of unmet dental care needs for adult immigrants |

Immigrants 2126 |

Quantitative Cross-sectional analysis |

The most significant barriers to dental care were identified as a lack of dental insurance and a yearly income less than $40,000 CAD. |

N/A |

|

Nicol et al. (2014)49 Australia |

Explored current understanding of the refugee experience related to childhood oral health |

Refugees 44 |

Qualitative Community-based participatory analysis/focus groups |

Three main themes were identified that impact refugees’ experience of early oral health care: the parent experience, resettlement issues, and enablers and barriers to accessing dental services. |

N/A |

|

Ruiz-Casares et al. (2016)43 Canada |

Investigated health service providers’ knowledge of health care coverage for refugees |

Health care providers 1772 |

Quantitative Cross sectional survey analysis |

Health care providers were identified as having a minimal understanding of refugee health care coverage. Findings suggest the need for improving knowledge of policy changes to prevent confusion among health care professionals and ensure that appropriate care is given. |

N/A |

|

Doucette et al. (2018)40 Canada |

Investigated the benefits of professionally trained versus untrained language interpreters in the delivery of dental hygiene care to immigrants |

Dental hygiene students, faculty & volunteer language interpreters 22 |

Quantitative Cross-sectional survey design |

The use of language interpreters was reported as improving dental hygiene students’ confidence in providing culturally competent care. A preference for professionally trained interpreters was identified as a facilitator to reducing miscommunication of health concepts. |

Future research should investigate the impact of interpreters working alongside practising clinicians for improving cultural competency. |

|

Suurmond et al. (2013)44 The Netherlands |

Sought to identify challenges facing health care providers in their first contact with asylum-seeking/refugee populations |

Public health nurse practitioners & physicians 46 |

Qualitative Surveys and focus group interviews |

Care providers’ first contact experiences were dominated by 4 challenges: proper assessment of current health condition, assessment of health risks, providing information on the host country’s health system, and providing health education. Use of professional interpreters, sufficient time for health assessments, and improved referral pathways to other services/providers are needed to promote culturally competent care. |

Future research should include the perspectives of both health care providers and asylum seekers to inform aspects of care requiring closer attention. |

|

Subedi and Rosenberg (2014)20 Canada |

Explored socioeconomic factors and health outcomes of recent versus settled immigrants in Canada |

Immigrants 10,664 |

Quantitative Cross-sectional survey analysis |

There are statistically significant variations in health outcomes between new and established immigrants in Canada. Health status was found to deteriorate with length of time in the country owing to challenges accessing health services, language barriers, low household income, and work-related stress. |

Future research using longitudinal data may better inform mental health status of immigrants and impacts on health outcomes as well as health care challenges faced by immigrants. |

|

Jensen et al. (2013)45 Denmark |

Investigated the experience of general practitioners who provide care to refugees |

General practitioners (MD) 9 |

Qualitative content analysis Semi-structured interviews |

Care for refugees deviated from standards of care for the general populace. A lack of national policy to direct appropriate care management of refugee populations is identified as contributing to sentiments of disempowerment among providers leading to reluctance to initiate comprehensive care. |

Future research should include the refugee patient perspective to better inform how care is received. |

|

Burchill and Pevalin (2014)29 England |

Explored the experiences of nurses working with refugee and asylum-seeking families using Quickfall’s model (2004; 2010) for cultural competency assessment |

Public health nurses 14 |

Qualitative analysis In-depth interviews |

Nurse providers were found to demonstrate aspects of cultural competence within their practice but were challenged by frequent health policy changes for refugees which elicited confusion about care they could provide and resentment towards patients with high needs in the face of limited resources. |

N/A |

|

Zghal et al. (2021)48 Canada |

Explored new immigrant perceptions of the cultural competence of health care providers and its impact on their reported health-related quality of life. |

Immigrants 117 |

Quantitative Descriptive cross-sectional survey analysis |

Immigrants’ reported health-related quality of life was found to be linked to competency of care providers under the following variables: experiences of discrimination, interpreter use, and trust in the health care provider. Improvements for patient–provider communication include non-discriminatory health policy development and linguistically appropriate resources. |

Current scales to measure cultural competence may over- or underestimate discrimination and its health effects. Development of reliable instruments and engagement of immigrants in research design are required. |

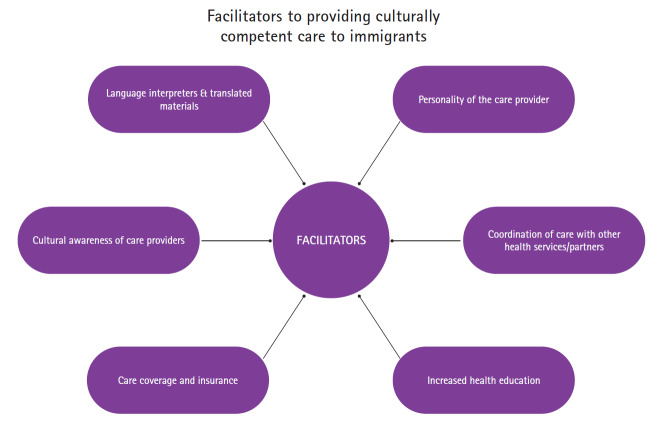

Figure 2.

Barriers to providing culturally competent care to immigrants

Figure 3.

Facilitators to providing culturally competent care to immigrants

Barriers to culturally competent care

Six barriers to providing culturally competent oral health care for immigrants were identified: 1) difficulties in communication9, 29, 40–42, 44–49; 2) lack of trust29, 44, 46–48; 3) poor cultural understanding29, 41, 42, 44, 45, 47–49; 4) differing perceptions of oral health29, 41, 42, 44, 45, 47–49; 5) challenges for funding and interpreting health policy/programs9, 20, 29, 41–47, 49; and 6) lack of accessible oral health care9, 19, 20, 29, 41, 42, 45–49 (Figure 2).

Difficulties in communication

Communication difficulties were the most commonly reported barrier to care.9, 20, 29, 41, 42, 45–49 Poor communication resulted in errors or challenges in taking health histories, obtaining informed consent, and/or ensuring patients understood recommended treatments, which compromised appropriate care delivery to immigrants.40, 42, 46, 47 Suurmond et al.44 reported that providers felt discouraged by a lack of culturally specific or appropriately translated health materials and that, when available, written translated materials did not offset sizeable differences in literacy levels among refugees and immigrants. Breakdowns in communication owing to these challenges were cited as reasons for feelings of exclusion and abandonment among immigrants as well as frustration and discomfort in treating this population among care providers.29, 41, 44, 45, 48

Lack of trust

Communication challenges were identified as a factor contributing to a lack of trust among immigrants accessing care.29, 48, 50 Burchill and Pevalin29 reported a lack of trust in the health care system among refugees, perhaps stemming from their suspicion of authorities as a result of unjust or punitive experiences in their home countries. In a study of volunteer dentists treating asylum seekers, van Midde et al.47 reported that migrants felt the dental care they received was dependent on the clinician’s personal willingness to help, and some complained they felt misunderstood or that their needs and concerns were not taken seriously. Similarly, Zghal et al.48 explored the cultural competency of care providers in Canada from the lens of immigrant respondents, 44.5% of whom disclosed experiencing discrimination related to language barriers. Miscommunication is identified as not only hindering trust between care providers and immigrants, but also reinforcing immigrants’ feelings of discrimination with negative implications for their willingness to access care in the future.44, 48

Poor cultural understanding

Poor understanding of health care systems in their new country of residence was found to affect how immigrants accessed services.20, 29, 41, 44, 45, 47–49 It was also identified that poor understanding of patient culture impacted the relationship between care providers and patients.29, 41, 45, 47 Suurmond et al.44 explained that cultural differences in the interpretation of “health” between providers and patients and limited patient knowledge of body physiology complicated care providers’ understanding of patient-reported symptoms. This situation led to increased time spent during appointments explaining health concepts.44 The study by van Midde et al.47 also reported that dentists acknowledged that immigrant patients presenting with similar oral health problems were not always treated in the same manner or to the same standard of care as others, depending on their racial or ethnic background.47 A lack of understanding and recognition of variations in cultural concepts of health and disease among OHCPs and HCPs was a noted deficiency across studies.29, 41, 42, 44, 45, 47–49

Differing perceptions of oral health

Respondents in van Midde et al.’s study47 reported feeling a lack of personal connection with or gratitude from immigrant patients after providing voluntary care services. This lack of gratitude was interpreted as arising from a lack of recognition of the significance of care received owing to cultural differences and contributed to strained relationships between immigrant patients and providers.47 OHCPs in Paisi et al.’s study42 explained that there was not enough education for immigrants on the objectives of preventive care services, resulting in differing perceptions of when care would be warranted among immigrant patients. The same study also reported that some immigrants may hold strong beliefs that traditional remedies and culturally specific oral hygiene aids are adequate measures for maintaining optimal oral health.42 Differences in cultural values and health practices may cause immigrant patients to be perceived as difficult or unwilling to accept behavioural change recommendations, causing further strain on provider–patient rapport.41, 44, 45

Challenges for funding and interpreting health policy/programs

Funding and policy constraints affect immigrants’ access to available health care services. Several studies cited limitations on the extent of treatment care providers could deliver to immigrant patients owing to low funding and restrictive health policies that set prescribed, tick-box criteria to determine eligibility for coverage.29, 44, 47 Stringent criteria were identified as a barrier for care providers in determining what oral health services and,health care supports patients were eligible to receive under public funding models. Rigid eligibility assessment criteria resulted in non-acute or complex needs being left unmet, exacerbating poor health outcomes among immigrants.29, 44, 47 Suurmond et al.44 reported that triaging urgent care needs over comprehensive care of vulnerable immigrant and refugee populations places providers in ethically compromising situations. Ethical challenges also arose for providers when assessing for other health problems, knowing that follow-up care could not be guaranteed owing to financial constraints and restrictive health policy for immigrants.29, 44, 49 Provision of appropriate, comprehensive care for immigrants was hindered by limitations in government funding allocated to immigrant health programs and inflexible parameters to confirm or deny coverage eligibility.9, 19, 29, 43, 44, 47

One study focusing on care providers’ understanding of the Canadian Interim Federal Health Program revealed that most providers had a very poor understanding of the oral health insurance coverage that provides limited, temporary coverage to recent refugees.43 As a result, providers felt less comfortable billing to these programs and were found to be less apt to deliver care under this funding model.43 In their UK-based study, Burchill and Pevalin29 reported that HCPs identified frequent changes to immigration policy as a source of confusion, making it difficult to decipher individuals’ benefit eligibility. Policy struggles, alongside the high health needs of this population and limited resources available, were cited as contributing to feelings of resentment in providing care to immigrant groups.29

Lack of accessible oral health care

The accessibility of care was described in various ways, ranging across social determinants of health and well-being.9, 19, 20, 29, 41, 45, 48–50 Multiple studies identified difficulties for immigrants in understanding how to access and navigate health care systems.9, 19, 20, 29, 41–43, 45, 48–50 Challenges such as the physical location of care services, transportation, and cost of care were all factors impeding immigrants’ access to appropriate providers and services.20, 29 Paisi et al.42 and van Midde et al.47 both identified punitive appointment booking systems as a barrier. Such systems impose additional charges or threaten termination of status as a patient for late arrivals or missed appointments. Difficulties in attending appointments were often attributed to transportation issues and poor communication of appointment times, expectations, and office policies, jeopardizing immigrants’ ability to access future care.42, 47

In Canada, Zghal et al.48 and Subedi and Rosenberg20 noted challenges for immigrants who did not speak English or French. A lack of translated materials affected care access by immigrants as well as the ability of health organizations to direct patients to appropriate adjunct care within the health system.42, 45 Barriers to care provision experienced by OHCPs included difficulties in reminding patients of appointments, providing directions to the dental clinic, and advising patients on how to use public transportation.47 Paisi et al.42 reported that intersecting personal and systemic factors influenced low access to care by immigrants. Poor understanding of the concept of, and rationale for, a dental health care system, how the system works, where to find oral health services, and the processes involved to become a patient were cited barriers.42 Additionally, systemic factors such as low knowledge of resources and supports for immigrants among care providers and administrators limited access to care services available for this population.29, 41–43, 45 Language and communication challenges were woven throughout discussions of health and oral health care accessibility in the articles reviewed.9, 20, 29, 40–42, 44, 47, 49

Facilitators to culturally competent care

Six facilitators to culturally competent care were identified in the studies selected: 1) use of language interpreters and translated materials29, 40–42, 44, 48, 49; 2) personality of the care provider41, 42, 48, 49; 3) coordination of care with other health services and partners20, 29, 44, 45, 47, 49; 4) increased health education29, 41, 42, 44–46, 48, 49; 5) care coverage and insurance9, 19, 47, 49; and 6) cultural awareness of care providers29, 41–44, 48, 49 (Figure 3).

Language interpreters and translated materials

Use of language interpreters was the most common facilitator to culturally competent care, being reported in 7 articles.29, 40–42, 44, 48, 49 The use of interpreters was recognized as a means of increasing the ability of patients to express oral health concerns, building rapport, and improving the ability of OHCPs to provide treatment information.40, 42 Qualified interpreters—those with medical or dental-specific training—improved communication of accurate information regarding diagnosis and treatment, leading to improved patient experiences and treatment outcomes when compared with interpreters without specialized medical or dental training.40, 41, 44, 48 Immigrants who use professional interpreters reported higher health-seeking behaviours and were more likely to seek out preventive services.48 Access to readily available translated materials in multiple languages in the care setting was also identified as reducing miscommunication and resulted in reported improvements in the immigrant patient experience.20, 44 Visual aids were suggested as an alternative mode of communication that could circumvent language differences when interpreters were unavailable or in circumstances of varying levels of literacy.49

Personality of care provider

The personality of the care provider was repor,ted in several studies as a major determinant of trust and communication between providers and immigrant patients.41, 42, 48, 49 Care providers exhibiting characteristics such as sensitivity, respect, empathy, and humility were identified as being better able to establish safe practice settings and trusting relationships with immigrant patients.41, 48 Providers demonstrating these traits were reportedly more successful in resolving differing interpretations of the importance of health cross-culturally and empowering patients to be partners in health improvement and maintenance.48 High levels of trust within the provider–patient relationship were correlated with improved self-reported health by immigrants, improved patient satisfaction with care received, and better adherence to health behaviour recommendations, medication use, and follow-up appointments.48

Coordination of care with other health services and partners

Several studies identified collaboration among health services as a facilitator to oral and overall health care for immigrant populations.29, 44, 45, 47, 49 To better support health outcomes for immigrants, Suurmond et al.44 identified a need for more training for care providers on common barriers that immigrants face so they may better self-assess and reflect on the boundaries of their personal scope of practice and recognize when, and with whom, collaboration in care is required. Support for increased development of interdisciplinary health clinics within community centres already accessed by immigrant groups was also identified as a means of directly reaching populations in their community of settlement.29

Multiagency teams, comprising professionals from a variety of disciplines who work together to advocate for patient needs and coordinate care with other health or social programs, were identified as critical community health supports that improved immigrants’ access to care.20, 29, 49 Multiagency teams were identified as improving immigrant patients’ ability to navigate health and social services that they might otherwise have been unaware of or lacked resources to know how to access.29, 49 The literature identifies that care providers and coordinated teams have an important responsibility to provide clear and practical i,nformation to immigrants about their new home country’s health care systems, need for timely assessments, and guidelines for disease prevention to help build familiarity and personal capacity to navigate health systems and manage their oral and health care needs independently.29, 44

Increased health education

Increased health education was strongly reported as a facilitator to culturally competent care for immigrant populations.29, 41, 42, 44–46, 48, 49 Education that helps immigrants better understand a North American, prevention-based approach to oral and overall health care was linked to improving communication and understanding between patients and providers.42 Opportunities for care providers to discuss health concepts with immigrant populations in a non-judgmental setting with linguistically appropriate resources were noted to have a positive impact both on immigrants’ knowledge of health and disease prevention behaviours and on providers’ ability to recognize alternative cultural values and approaches to caring for diverse populations.29, 41, 43, 44 Recommendations from the literature include involvement of care providers in community oral/health screenings, community-based health clinics, and education sessions to initiate discussion with immigrants.49 In addition, reaching out to local immigrant services, community programs, and professional practice associations can help to inform environmental scans of providers’ practice settings to identify barriers as well as culturally sensitive, linguistically appropriate resources required to improve care delivery in their own practices.48, 49

Care coverage and insurance

Calvasina et al.9 identified that having health and dental insurance was more significant for immigrants’ access to care services than their level of income. Access to insurance is closely linked to employment status, and low employment opportunities are a socioeconomic barrier commonly experienced by immigrants with skills and education that may not be recognized in their new country.9, 19, 20, 29, 49 Expanding public coverage or programs that link immigrants with employment that provides health and dental insurance was identified as a sizeable facilitator to increasing access to services.9, 19, 20 Additionally, expanding eligibility for insurance coverage increases exposure of care providers to culturally diverse patient families.9

Cultural awareness of care providers

Several articles reported care providers exhibiting cultural competence in their knowledge and care as a key contributor to improved access to health services.29, 41–44, 48, 49 Cultural competency of providers encompassed knowledge of diverse populations and cultural practices, and having general awareness of geography, global affairs, and barriers faced by specific ethnic or immigrant populations.29, 41–44, 48, 49 The noted intersection of facilitators identified across articles reviewed was conducive to providers’ personal capacity development and care systems that are better equipped to provide culturally safe and sensitive care, where cultural differences are recognized, respected, and reflected in care decision making and delivery to immigrants.32

DISCUSSION

This scoping review compiled current knowledge on cultural competence capacity of oral and health care providers, identifying barriers and facilitators to immigrants’ access to appropriate oral health care services. Findings suggest there are several barriers that reduce access to care for immigrant populations at both individual and systemic levels. OHCPs need to recognize and address these barriers to better understand culturally diverse health needs and develop the ability to provide culturally competent care. Levy et al.28 explain that, although health care providers may learn of social determinants of health, they may not have the experience, time or resources to properly address complex health needs due to a variety of challenges. A lack of linguistically appropriate resources for immigrant patients and supports for providers, such as translated materials and access to qualified interpreters, are sizeable deficits impacting the ability of Canadian oral and health care systems to provide culturally competent care.40, 41, 48 Other important challenges, such as limited government funding for immigrant and refugee health services and the inability of newcomers to navigate health systems in their new country, compound deficits in accessing care.9, 42, 43, 47, 49 Low utilization of assistance programs for immigrant oral health is also further complicated by OHCPs who lack thorough knowledge of publicly funded insurance coverage.43 In Canada, preventive and restorative oral health services are largely excluded from the country’s public health care system; responsibility for oral care management of immigrant populations falls to privately owned dental offices where OHCPs are less likely to receive training on or resources for implementing culturally sensitive care.28, 52 The current study suggests that a lack of guidance and structural support for OHCPs to navigate transitional health plans and complex care needs of immigrant patients contributes to a lack of familiarity in treating this population. Aversion to treating immigrant patients due to these challenges prevents the development of cultural competence capacity within the profession and may lead to a proliferation of ethically compromised care decisions and unconscious biases.41, 43–45

An important factor in improving access to care identified in this review is the use of multiagency and interprofessional teams.20, 29, 44, 49 Care coordination across providers and effective referral pathways are noted as strong predictors for both immigrant access to services and provider familiarity with culturally sensitive care. A multitiered approach is required to address this need; reducing current barriers to interprofessional health care collaboration and practice is essential. Leveraging flexible funding agreements between provinces, territories, and the federal government to support targeted geographic and population needs will support the creation of collaborative health networks that include oral health care providers.9, 19, 28, 53 Collaborative health networks are noted in the literature as facilitating immigrant populations’ integration into the care systems of their new country and fostering a sense of belonging within their new communities.20, 42, 47 Establishing interprofessional networks for care coordination allows for a variety of professions to increase their exposure to immigrant and other underserved patient populations.29, 44 Increased exposure may improve providers’ knowledge and recognition of cultural needs, which stands to contribute to the development of thoughtful strategies for culturally competent care to overcome gaps in delivery and access noted in this review. However, advocacy from members of both oral and allied health professions is required to see these networks established.28, 42

The literature also identifies that a redirection of resources to establish coordinated networks for immigrant health may circumvent current challenges faced by OHCPs in private practice settings. Health professions practising in collaborative and hospital settings are often afforded more opportunities for training, continuing education, and resource provision on topics of culturally competent care delivery and publicly available health programs than OHCPs in private settings.41, 54, 55 Collaborative models may help OHCPs become better informed on navigating government-supported programming for immigrant populations and help to alleviate noted strains on the public health care system. Increasing access to oral care through interdisciplinary channels may reduce emergency room use, decrease wait times, and lower public health care costs related to systemic disease exacerbated by poor oral health.28

This review highlights a distinct need for not only policy development for oral health and immigrant populations, but also mobilization of policy information to OHCPs. The creation of policy alone is not enough to initiate action. OHCPs require timely information from both government and their professional regulatory bodies on how new immigration policy and changes to public health programs are implicated in the delivery of oral health care to immigrant populations. Strategic policy development and targeted implementation of resources facilitating accessible systems are required from policymakers at all levels of government to address limitations in immigrant access to oral health care and OHCPs’ ability to provide culturally appropriate care.28, 42, 43, 56 Improving communication between governments, professional regulators, and care providers on health policy and programming is an urgent need identified in this review and is particularly timely due to the forecasted population growth from immigration to Canada.57 The potential impact of Canada’s new national dental care plan on these identified deficits for immigrants and OHCPs remains to be determined.

Limitations and areas for future research

Limitations to this review include the selection of articles published only in English, a limitation the authors acknowledge as important given language was an identified barrier to care. The generalizability of findings to the Canadian population may be limited by the paucity of Canadian-based studies available. In addition, few studies have sought to explore the experience of practising OHCPs and their self-reported cultural competency. This remains an area warranting further primary research. Research focusing on the self-evaluative cultural competence capacity of actively practising OHCPs is needed to better understand strengths and deficits in current capacity to inform future development strategies.

CONCLUSION

Growing cultural competence capacity within the oral health professions is of critical importance given the rapid pace of globalization and immigration to Canada. This scoping review has synthesized the limited literature available on practising OHCPs’ cultural competency and identified barriers and facilitators to capacity development that warrant further research. Provincial and territorial analyses in Canada on OHCPs’ perceived cultural competency may identify needs and supports for building OHCPs’ capacity and inform targeted funding and policy needs locally and nationally at an integral time for public oral health funding. Research focused on the expansion of linguistically diverse health care materials and their impact on oral health services uptake and compliance among immigrant populations is also required. Without research focused on bridging the gaps in oral health care access experienced by immigrants and OHCPs’ capacity to implement culturally competent care, it is likely that inequities in oral health in Canada will persist.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no known conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Leigha Rock for her feedback and mentorship and Shelley McKibbon, Health Sciences Reference Librarian, Dalhousie University for her guidance and assistance.

Footnotes

CDHA Research Agenda category: access to care and unmet needs; capacity building of the profession

References

- Immigration, Refugees, and Citizens Canada . 2022 annual report to Parliament on immigration . Ottawa (ON) : : Government of Canada ; ; 2022 . p. 62. Available from: www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/documents/pdf/english/corporate/publications-manuals/annual-report-2022-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . Immigrants make up the largest share of the population in over 150 years and continue to shape who we are as Canadians . The Daily . 26 October 2022 . Available from: www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/221026/dq221026a-eng.pdf?st=itnd4Xq9

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees . Global trends: Forced displacement in 2021 . Geneva, Switzerland : : UNHCR ; ; 2021 . Available from: www.unhcr.org/globaltrends [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Council for Refugees . Talking about refugees and immigrants: A glossary of terms . Montreal (QC) : : CCR ; ; 2010 . Available from: https://ccrweb.ca/sites/ccrweb.ca/files/static-files/glossary.PDF [Google Scholar]

- Shommu NS , Ahmed S , Rumana N , Barron GRS , McBrien KA , Turin TC What is the scope of improving immigrant and ethnic minority healthcare using community navigators: a systematic scoping review Int J Equity Health 2016 ; 15 ( 6 ): 1 – 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds J , Flahault A Refugees in Canada during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021 ; 18 ( 3 ): 1 – 16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano Y , Antabe R Regular dental care utilization: The case of immigrants in Ontario, Canada J Immigr Minor Health 2022 ; 24 ( 1 ): 162 – 169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlan R , Ghazal E , Saltaji H , Salami B , Amin M Impact of social support on oral health among immigrants and ethnic minorities: a systematic review PloS One 2019 ; 14 ( 6 ): e0218678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvasina P , Muntaner C , Quiñonez C Factors associated with unmet dental care needs in Canadian immigrants: An analysis of the longitudinal survey of immigrants to Canada BMC Oral Health 2014 ; 14 ( 1 ): 145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada & Pan-Canadian Public Health Network . Key health inequalities in Canada: a national portrait. Executive summary . Ottawa (ON) : : Government of Canada ; ; 2018 . Available from: www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/science-research-data/key-health-inequalitiescanada-national-portrait-executive-summary.html [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y Differentiation of self-rated oral health between American non-citizens and citizens Int Dent J 2016 ; 66 ( 6 ): 350 – 355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover J , Vatanparast H , Uswak G Risk determinants of dental caries and oral hygiene status in 3–15 year-old recent immigrant and refugee children in Saskatchewan, Canada: a pilot study J Immigr Minor Health 2017 ; 19 ( 6 ): 1315 – 1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson FA , Wang Y , Borrell LN , Bae S , Stimpson JP Disparities in oral health by immigration status in the United States J Am Dent Assoc 2018 ; 149 ( 6 ): 414 – 421 e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur N , Kandelman D , Potvin L Effectiveness of “Safeguard Your Smile,” an oral health literacy intervention, on oral hygiene self-care behaviour among Punjabi immigrants: a randomized controlled trial Can J Dent Hyg 2019 ; 53 ( 1 ): 23 – 32 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote S , Geltman P , Nunn M , Lituri K , Henshaw M , Garcia RI Dental caries of refugee children compared with US children Pediatrics 2004 ; 114 ( 6 ): e733 – e740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiabi E , Matthews DC , Brillant MS The oral health status of recent immigrants and refugees in Nova Scotia, Canada J Immigr Minor Health 2014 ; 16 ( 1 ): 95 – 101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Assessing Interactions Among Social, Behavioral, and Genetic Factors in Health . Genes, behavior, and the social environment: Moving beyond the nature/nurture debate . Washington (DC) : : National Academies Press ; ; 2006 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox M , Thayer Z , Wadhwa PD Acculturation and health: the moderating role of socio-cultural context Am Anthropol 2017 ; 119 ( 3 ): 405 – 421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvasina P , Muntaner C , Quiñonez C The deterioration of Canadian immigrants’ oral health: Analysis of the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2015 ; 43 ( 5 ): 424 – 432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subedi R , Rosenberg M Determinants of the variations in self-reported health status among recent and more established immigrants in Canada Soc Sci Med 2014 ; 115 : 103 – 110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucette H. Oral health disparities experienced by recent refugees. Dimens Dent Hyg [Internet]. 2022 Sep 16; Available from: https://dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/article/oralhealth-disparities-experienced-recent-refugees/

- Paisi M , Baines R , Burns L , Plessas A , Radford P , Shawe J , et al. Barriers and facilitators to dental care access among asylum seekers and refugees in highly developed countries: a systematic review BMC Oral Health 2020 ; 20 ( 1 ): 337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez R , Spinler K , Kofahl C , Seedorf U , Heydecke G , Reissmann DR , et al. Oral health literacy in migrant and ethnic minority populations: a systematic review J Immigr Minor Health 2022 ; 24 ( 4 ): 1061 – 1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritano D , Moreo G , Carinci F , Campanella V , Della Vella F , Petruzzi M Oral health status among migrants from middle- and low-income countries to Europe: a systematic review Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021 ; 18 ( 22 ): 12203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra VM , Costanian C , Khanna S , Tamim H Dental care use by immigrant Canadians in Ontario: A cross-sectional analysis of the 2014 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) BMC Oral Health 2019 ; 19 ( 1 ): 78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold KB , Patel A Use of dental services by immigrant Canadians J Can Dent Assoc 2006 ; 72 ( 2 ): 1 – 7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Academy of Health Sciences . Improving access to oral health care for vulnerable people living in Canada . Ottawa (ON) : : CAHS ; ; 2014 . Available from: https://cahs-acss.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Access_to_Oral_Care_FINAL_REPORT_EN.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Levy BB , Goodman J , Eskander A Oral healthcare disparities in Canada: filling in the gaps Can J Public Health 2022 ; 114 ( 1 ): 139 – 145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchill J , Pevalin D Demonstrating cultural competence within health-visiting practice: Working with refugee and asylum-seeking families Divers Equal Health Care 2014 ; 11 : 151 – 159 [Google Scholar]

- Health Research & Educational Trust . Becoming a culturally competent health care organization . Chicago (IL) : : HRET, in partnership with the American Hospital Association ; ; 2013 . Available from: www.aha.org/system/files/hpoe/Reports-HPOE/becoming-culturally-competent-health-care-organization.PDF [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Nurses Association . Promoting cultural competence in nursing: position statement . Ottawa (ON) : : CNA ; ; 2018 . Available from: https://hl-prod-ca-oc-download.s3-ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/CNA/2f975e7e-4a40-45ca-863c-5ebf0a138d5e/UploadedImages/documents/Position_Statement_Promoting_Cultural_Competence_in_Nursing.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Chief Public Health Officer Health Professional Forum . Common definitions on cultural safety . Ottawa (ON) : : Public Health Agency of Canada ; ; 2023 . Available from: www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/publications/health-system-services/chief-public-health-officer-health-professional-forum-common-definitions-cultural-safety/definitions-en2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Maternal and Child Survival Program, USAID. Human Capacity Development [Internet]. ©2019. Available from: https://mcsprogram.org/our-work/health-systems-strengthening-equity/human-capacity-development/

- Riggs E , Gussy M , Gibbs L , van Gemert C , Waters E , Priest N , et al. Assessing the cultural competence of oral health research conducted with migrant children Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2014 ; 42 ( 1 ): 43 – 52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari T , Albino J Acculturation and pediatric minority oral health interventions Dent Clin North Am 2017 ; 61 ( 3 ): 549 – 563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Finance, Government of Canada. Making Dental Care More Affordable: The Canada Dental Benefit [internet]. Updated September 2022. Available from: www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2022/09/making-dental-care-more-affordable-the-canada-dental-benefit.html

- Department of Finance, Government of Canada . A Made-in-Canada Plan: Strong Middle Class, Affordable Economy, Healthy Future. Budget 2023 . Ottawa (ON) : : Government of Canada ; ; 2023 . Available from: www.budget.canada.ca/2023/homeaccueil-en.html [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H , O’Malley L Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005 ; 8 ( 1 ): 19 – 32 [Google Scholar]

- Tricco AC , Lillie E , Zarin W , O’Brien K , Colquhoun H , Levac D , et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): checklist and explanation Ann Intern Med 2018 ; ( 169 ): 467 – 473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucette HJ , Haslam KS , Zelmer KC , Brillant MS The use of language interpreters for immigrant clients in a dental hygiene clinic Can J Dent Hyg 2018 ; 52 ( 3 ): 167 – 173 [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau CJ , Kelly DM , Donnelly LR Exploring the views of and challenges experienced by dental hygienists practising in a multicultural society: a pilot study Can J Dent Hyg 2014 ; 48 ( 4 ): 139 – 146 [Google Scholar]

- Paisi M , Baines R , Wheat H , Doughty J , Kaddour S , Radford PJ , et al. Factors affecting oral health care for asylum seekers and refugees in England: A qualitative study of key stakeholders’ perspectives and experiences Br Dent J 2022 ; Jun 8 : 1 – 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Casares M , Cleveland J , Oulhote Y , Dunkley-Hickin C , Rousseau C Knowledge of healthcare coverage for refugee claimants: Results from a survey of health service providers in Montreal PLoS ONE 2016 ; 11 ( 1 ): e0146798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suurmond J , Rupp I , Seeleman C , Goosen S , Strinks K The first contacts between healthcare providers and newly-arrived asylum seekers: A qualitative study about which issues need to be addressed Public Health 2013 ; 127 ( 7 ): 668 – 673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen N , Norredam M , Priebe S , Krasnik A How do general practitioners experience providing care to refugees with mental health problems? A qualitative study from Denmark BMC Fam Pract 2013 ; 14 ( 17 ): 1 – 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnaki P , Katsas K , Diamantis DV , Riza E , Rosen MS , Antoniadou M , et al. Dental health, caries perception and sense of discrimination among migrants and refugees in Europe: Results from the Mig-HealthCare Project Appl Sci 2022 ; 12 ( 18 ): 9294 [Google Scholar]

- Van Midde M , Hesse I , Heijden GJ , Duijster D , Elteren M , Kroesen M , et al. Access to oral health care for undocumented migrants: Perspectives of actors involved in a voluntary dental network in the Netherlands Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2021 ; 49 ( 4 ): 330 – 336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zghal A , El-Masri M , McMurphy S , Pfaff K Exploring the impact of health care provider cultural competence on new immigrant health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study of Canadian newcomers J Transcult Nurs 2021 ; 32 ( 5 ): 508 – 517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol P , Al-Hanbali A , King N , Slack-Smith L , Cherian S Informing a culturally appropriate approach to oral health and dental care for pre-school refugee children: a community participatory study BMC Oral Health 2014 ; 14 ( 1 ): 69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karani R , Varpio L , May W , Horsley T , Chenault J , Miller KH , et al. Commentary: Racism and bias in health professions education Acad Med 2017 ; 92 : S1 – S6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertshaw L , Dhesi S , Jones LL Challenges and facilitators for health professionals providing primary healthcare for refugees and asylum seekers in high-income countries: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research BMJ Open 2017 ; 7 ( 8 ): e015981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada, Government of Canada. Canada’s Health Care System [internet]. ©2016. Available from: www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canada-health-care-system.html

- Health Canada, Government of Canada. Working Together to Improve Health Care for Canadians [internet]. 2023 Feb 7. Available from: www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2023/02/working-together-to-improve-health-care-for-canadians.html

- Kumra T , Hsu YJ , Cheng TL , Marsteller JA , McGuire M , Cooper LA The association between cultural competence and teamwork climate in a network of primary care practices Health Care Manage Rev 2020 ; 45 ( 2 ): 106 – 116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham BA , Marsteller JA , Romano MJ , Carson KA , Noronha GJ , McGuire MJ , et al. Perceptions of health system orientation: Quality, patient centeredness, and cultural competency Med Care Res Rev 2014 ; 71 ( 6 ): 559 – 579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucette H , Yang S , Spina M The impact of culture on new Asian immigrants’ access to oral health care: a scoping review Can J Dent Hyg 2023 ; 57 ( 1 ): 33 – 43 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . Population projections for Canada (2021 to 2068), provinces and territories (2021 to 2043) . Catalogue no. 91-520-X. Release date: August 22, 2022. Available from: www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/91-520-x/91-520-x2022001-eng.htm

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.