Abstract

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous condition with varied clinical and pathophysiological characteristics. Although there is increasing evidence that COPD in low-income and middle-income countries may have different clinical characteristics from that in high-income countries, little is known about COPD phenotypes in these settings. We describe the clinical characteristics and risk factor profile of a COPD population in Uganda.

Methods

We cross sectionally analysed the baseline clinical characteristics of 323 patients with COPD aged 30 years and above who were attending 2 national referral outpatient facilities in Kampala, Uganda between July 2019 and March 2021. Logistic regression was used to determine factors associated with spirometric disease severity.

Results

The median age was 62 years; 51.1% females; 93.5% scored COPD Assessment Test >10; 63.8% modified medical research council (mMRC) >2; 71.8% had wheezing; 16.7% HIV positive; 20.4% had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis (TB); 50% with blood eosinophilic count >3%, 51.7% had 3 or more exacerbations in the past year. Greater severity by Global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage was inversely related to age (aOR=0.95, 95% CI 0.92 to 0.97), and obesity compared with underweight (aOR=0.25, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.82). Regarding clinical factors, more severe airflow obstruction was associated with SPO2 <93% (aOR=3.79, 95% CI 2.05 to 7.00), mMRC ≥2 (aOR=2.21, 95% CI 1.08 to 4.53), and a history of severe exacerbations (aOR=2.64, 95% CI 1.32 to 5.26).

Conclusion

Patients with COPD in this population had specific characteristics and risk factor profiles including HIV and TB meriting tailored preventative approaches. Further studies are needed to better understand the pathophysiological mechanisms at play and the therapeutic implications of these findings.

Keywords: COPD epidemiology, COPD exacerbations, COPD pathology

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous condition with the greatest burden in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) yet there is limited understanding of disease characteristics in this setting.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

A cohort of patients with COPD recruited in hospital clinics in Uganda showed a high burden of disease with frequent exacerbations—86% were GOLD category D. The cohort had a high exposure to biomass smoke and only 38% were past or present smokers.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE, OR POLICY

There is need for more research into effective strategies to prevent and treat COPD in LMICs—it cannot be assumed that guidelines derived in high-income countries will apply.

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous lung condition characterised by chronic respiratory symptoms (dyspnoea, cough, expectoration and/or exacerbations) due to abnormalities of the airways (bronchitis, bronchiolitis) and/or alveoli (emphysema) that cause persistent, often progressive, airflow obstruction.1 COPD is the third leading cause of death and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) globally, with 90% of these deaths occurring in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).2 3 In 2019, 3.3 million deaths and 74.4 million DALYs were attributed to COPD.4 Furthermore, the COPD burden is projected to keep increasing due to increased ageing of the population and continued exposure to risk factors.5 COPD is a complex syndrome with numerous pulmonary and extrapulmonary components. It is not yet clearly known how different patterns of exposures affect the clinical presentation, physiology, imaging, response to therapy, lung function decline and survival.6 7 Recent research in COPD has been aimed at better understanding the heterogeneity across different groups of patient with COPD and phenotyping patients with COPD for better understanding of this condition.8 These phenotypes are also aimed at categorising those with similar clinical characteristics and their response to treatments, to better guide management approaches.9 10

The most widely known risk factor for the development of COPD is tobacco smoke exposure, and most of the knowledge about COPD has been based on tobacco-exposed populations. In sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence of COPD is high, with a pooled prevalence of 8%, and associated risk factors include increasing age, smoking, history of pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) and biomass smoke exposure.11 12 Significantly, indoor, and outdoor air pollution, occupational exposures and infections have also emerged as risk factors.13 14 These varied risk factors have a different pathway of effect on the lung compared with tobacco smoke.15 Unique host factors including nutritional status, high HIV prevalence and previous pulmonary TB also contribute to the risk of developing the airflow obstruction that is characteristic of COPD in LMICs. Little is known about how the different patterns of noxious exposures and other risk factors affect the pathological and clinical phenotypes. Additionally, there is scarcity of data concerning patient populations with COPD from LMICs. Van Gamert et al, following a cross-sectional study in Uganda, found that people with COPD were younger (30–40 years) compared with those in high-income countries (HICs) who are usually older than 40 years, and presented more commonly with wheeze compared with COPD in HICs.16 Soriano et al found that 70% of COPD in HICs was attributed to tobacco smoking, while environmental exposures accounted for 60% of COPD in LMICs.17 These findings allude to potential variation between COPD in HICs and LMICs and there is insufficient data from LMICs to provide robust management advice.18 Further region-specific research is needed to bridge this knowledge gap and better guide management approaches. This is especially true for LMICs where resources are limited and the burden of COPD is high. The objective of the current analysis was to describe the clinical characteristics of a population with COPD in Uganda.

Methods

Study design and setting

We enrolled a cohort of 323 patients with COPD, who presented at the chest clinic outpatient department of Mulago National referral hospital, Kiruddu referral hospital and the Lung Institute clinic, all situated in Kampala, Uganda.

The Lung Institute Clinic is a specialist outpatient chest clinic situated within the College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Given these are referral facilities, they attract patients from across the country.

We enrolled participants who were aged 30 years and above, who consented to participate in the study, and with the aim of being followed up for 1 year to evaluate the frequency and predictors of exacerbations among these patients. The sample size was calculated using the primary objective of the COPD Attack (COPA) study, and with a sample size of 323 patients, we had power of 94% of estimating at least 10 percentage unit difference in proportion of frequent exacerbation among the patients with COPD than the 50% estimated from the Uganda Registry of Asthma and COPD data with a 95% CI.19 20

Study procedures

We diagnosed COPD using quality assured spirometry according to ATS standards in patients who had a supporting history of dyspnoea, chronic cough, sputum production and a history of exposure to risk factors for the disease.21

We included participants with a diagnosis of COPD aged 30 years and above who provided informed consent. We excluded participants who had active PTB and other comorbid diseases likely to affect participation or outcomes, such as lung cancer and asthma as deemed by the investigational team. Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions slowed patient enrolment and follow-up due to the travel restrictions and fear of hospital settings.

Spirometry was conducted by trained technicians, using the Vitalograph Pneumotrac spirometer with Spirotrac software (Vitalograph; Buckingham, UK). It measured the forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), the FEV1/FVC ratio and flow-volume curves. We obtained three acceptable maneuvers in accordance with American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) guidelines.22 A COPD diagnosis was defined as a postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio below 0.7 together with appropriate symptoms, such as dyspnoea, chronic cough, sputum production, wheezing/chest tightness, recurrent chest infections in the context of a history of risk factors, following Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines. GOLD staging was performed using postbronchodilator spirometry data, an assessment of dyspnoea using the modified MRC dyspnoea scale and the exacerbation history. We staged COPD using the GOLD criteria based on lung function using the Global Lung Initiative mixed ethnic reference equations.23 Exacerbations were defined as the number of times patients experienced worsening of respiratory symptoms that warranted additional medication, and this often resulted in a visit to a health facility or pharmacy.

At enrolment, all consenting participants underwent a respiratory focused clinical evaluation using a case report form to collect data on demographics, symptoms, exposures to outdoor and indoor pollutants, maternal exposures, childhood medical history, exposure to known COPD risk factors, tobacco smoking, biomass smoke exposure, psychosocial issues including dysfunctional breathing, comorbidities (allergies, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, diabetes mellitus), impact of COPD on the person’s life using the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) and Clinical COPD Questionaire, inhaler technique, vital signs and respiratory system physical signs. Baseline venous blood and induced sputum samples were collected.

Patient and public involvement statement

There was no patient and public involvement in the development of this research.

Statistical analysis

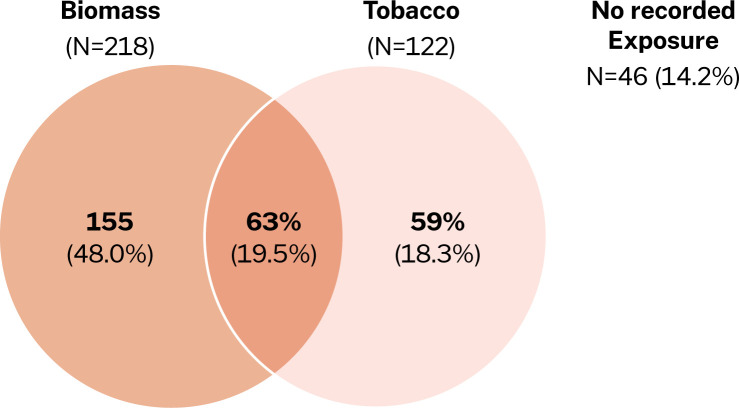

Patients’ baseline characteristics were summarised using proportions for categorical data, and mean (SD) or median (IQR) for continuous variables. The study outcome was the patients’ GOLD stage defined as binary outcome derived by grouping GOLD stages I and II into one category (mild–moderate) and GOLD stages III and IV into another category (severe–very severe). Biomass exposure was cross tabulated with tobacco smoking history and results were presented in a Venn diagram. A χ2 test was used to determine the association between biomass exposure and tobacco smoking. Logistic regression was used to determine factors associated with disease severity. All factors with p values less than 0.2 at a bivariable analysis (simple logistic regression) were subjected to a multivariable logistic regression, checked for multicollinearity and model building done using Akaike Information Criteria (AIC). Results from the final fit are presented as adjusted OR (aOR) with 95% CI. For all associations, a p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. STATA V.15 was used for all analyses.

Results

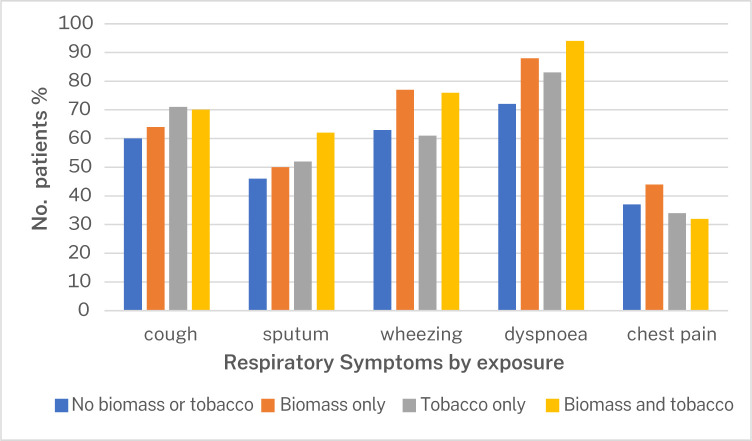

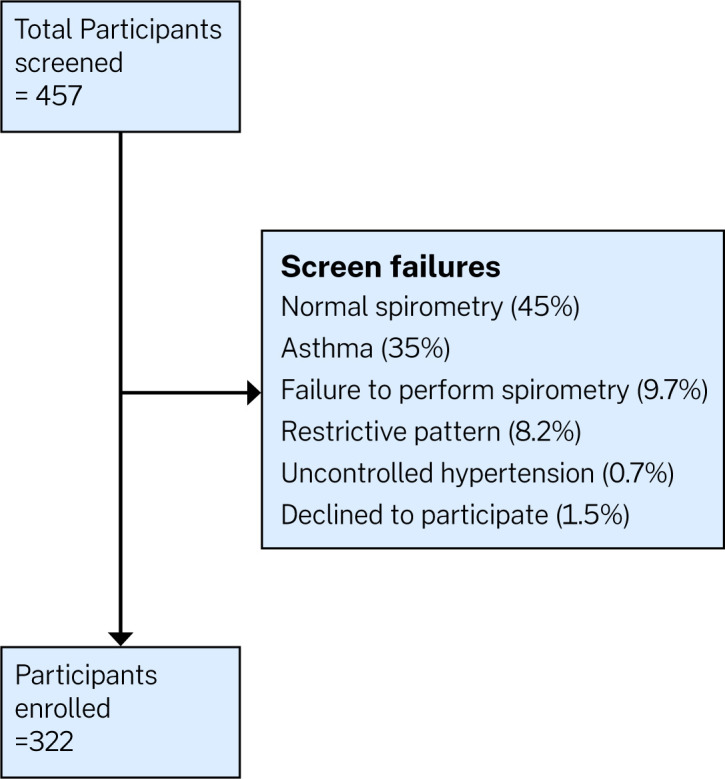

We screened 457 participants with spirometry who had presented to the health facilities with cough, wheeze, dyspnoea, chest tightness and/or sputum/phlegm production. 323 were eligible and consented to participate in the study, while 134 failed screening. Reasons for failing screening include asthma (35%), normal spirometry findings (45%), having restrictive pattern on spirometry (8.2%), failure to complete the spirometry procedure (9.7%), uncontrolled blood pressure (0.7%) and 1.5% of them simply declined to participate in study (figure 1). We enrolled a total of 323 participants, with a spirometry diagnosis of COPD between July 2019 and March 2021. The mean age of the participants was 62.9 years, and 51.1% were women. The symptom burden of the participants at presentation was high, with 93.5% having a CAT score of 10 and higher, and 63.8% scoring 2 and above on the modified medical research council (mMRC) dyspnoea score (table 1). The most significant exposure was biomass (figure 2), although there was no association between exposure history and patient presentation (figure 3).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with COPD presenting to a pulmonary centre in Kampala (n=323)

| Female, n (%) | 165 (51.1) |

| Age in years | |

| Mean (SD) | 62.9 (13.6) |

| Min, max | 30, 95 |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single | 8 (2.5) |

| Married | 171 (52.9) |

| Separated | 57 (17.7) |

| Widowed | 87 (26.9) |

| Education, highest level, n (%) | |

| None | 68 (21.1) |

| Some/completed primary | 159 (49.2) |

| Some/completed secondary | 56 (17.3) |

| Tertiary | 40 (12.4) |

| Persistent respiratory symptoms, n (%) | |

| Cough | 212 (65.6) |

| Sputum | 169 (52.3) |

| Wheezing | 232 (71.8) |

| Dyspnoea | 277 (85.8) |

| Chest pain | 119 (36.8) |

| Risk factors and comorbid conditions, n (%) | n=323 |

| No biomass or tobacco | 46 (14.2) |

| Biomass only | 155 (48.0) |

| Tobacco only | 59 (18.3) |

| Biomass and tobacco | 63 (19.5) |

| Ever been treated for TB, yes | 66 (20.4) |

| HIV status | n=317 |

| Positive | 53 (16.7) |

| Body mass index (BMI), kg/m2 | n=323 |

| Median (IQR) | 21.2 (18–25.7) |

| Underweight, that is, BMI<18.5 kg/m2, n (%) | 98 (30.3) |

| Normal weight, that is, BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, n (%) | 134 (41.5) |

| Overweight, that is, BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, n (%) | 55 (17.0) |

| Obese, that is, BMI ≥30 kg/m2, n (%) | 36 (11.2) |

| Hypertension diagnosis | 111 (34.4) |

| SPO2, %; Median (IQR) | 93 (90–96) |

| Severity of COPD Gold stage by FEV1 (post bronchodilator) | n=321 (%) |

| I | 93 (29.0) |

| II | 132 (41.1) |

| III | 71 (22.1) |

| IV | 25 (7.8) |

| Severity of COPD by ABCD Gold stage | n=225 (%) |

| A (<2 exacerbation and mMRC <2 and CAT <10) | 5 (2.2) |

| B (<2 exacerbations and mMRC≥2 and CAT ≥10) | 11 (4.9) |

| C (≥ 2 exacerbations and mMRC <2 and CAT <10) | 15 (6.7) |

| D (≥2 exacerbations and mMRC ≥2 and CAT ≥10) | 194 (86.2) |

| Medications for COPD (yes) | |

| Any medications for COPD | 66 (20.4%) |

| Salbutamol inhaler | 60 (18.5) |

| Salbutamol tablets | 27 (8.5) |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 27 (8.6) |

| Combination inhalers | 24 (7.4) |

| CAT score | n=323 |

| ≥10 | 302 (93.5) |

| <10 | 21 (6.5) |

| mMRC | |

| ≥2 | 206 (63.8) |

| <2 | 117 (36.2) |

| CCQ total score | n=322 |

| <1 | 13 (4.0) |

| 1–<2 | 47 (14.6) |

| 2–<3 | 174 (54.0) |

| ≥3 | 88 (27.3) |

| Complete blood count | |

| Eosinophil count (%) | n=314 |

| ≥3 | 157 (50%) |

| <3 | 157 (50%) |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | n=316 |

| ≥10 | 310 (98.1) |

| <10 | 6 (1.9) |

| Number of exacerbations | n=323 |

| Median (IQR)/year | 3 (1–10) |

| 0 | 62 (19.2) |

| 1–2 | 94 (29.1) |

| >2 | 167 (51.7) |

| Severity of exacerbations | n=323 |

| Mild (never visited health facility) | 62 (19.2) |

| Moderate (visited facility but not admitted) | 188 (58.2) |

| Severe (admitted) | 73 (22.6) |

Biomass refers to wood and charcoal (typically used for cooking purposes).

BMI, body mass index; CBC, complete blood count; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC, forced vital capacity; mMRC, modified medical research council; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SPO2, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation; TB, tuberculosis.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram showing numbers and percentages of 323 participants with a history of smoking and biomass exposure.

Figure 3.

Presenting symptoms in relation to biomass exposure status of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in this cohort (n=323).

Participants in GOLD stage III and IV were more often hypoxic, underweight and had a higher symptom burden (table 2). They also reported a history of more frequent and more severe exacerbations compared with those in GOLD I/II. Interestingly, participants in GOLD stages III and IV were younger than those in GOLD stages I and II. On assessment of comorbidities, hypertension was the most prevalent comorbidity with 34% of the participants having a history of hypertension. 22% of the participants reported a history of PTB, and there was a high prevalence of HIV in this population, with 16.7% of the participants who were eligible and enrolled being HIV positive.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics associated with disease severity defined according to GOLD stage (I and II vs III and IV) for patients presenting to referral Hospital clinics in Kampala

| Characteristics | Gold stage I and II | Gold stage III and IV | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | P value |

| Sex, n (%) | n=225 | n=96 | ||||

| Male | 102 (45.3) | 56 (58.33) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 123 (54.67) | 40 (41.67) | 0.59 (0.37 to 0.96) | 0.034 | 0.55 (0.25 to 1.23) | 0.146 |

| Age in years | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 65.2 (13.8) | 59.4 (12.6) | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.99) | 0.001 | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.97) † | <0.001 |

| Min, max | 30, 95 | 31, 91 | ||||

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||||

| Single | 4 (1.78) | 4 (4.17) | 2.15 (0.52 to 8.9) | 0.292 | ||

| Married | 116 (51.6) | 54 (56.3) | 1.00 | |||

| Separated | 36 (16.0) | 21 (21.9) | 1.25 (0.67 to 2.35) | 0.481 | ||

| Widowed | 69 (30.64) | 17 (17.7) | 0.53 (0.28 to 0.99) | 0.045 | ||

| Education, highest level, n (%) | ||||||

| None | 47 (20.9) | 21 (21.9) | 1.00 | |||

| Some/completed primary | 119 (52.9) | 38 (39.6) | 0.71 (0.38 to 1.34) | 0.297 | ||

| Some/completed secondary | 35 (15.6) | 21 (21.9) | 1.34 (0.63 to 2.83) | 0.439 | ||

| Tertiary | 24 (10.7) | 16 (16.7) | 1.49 (0.66 to3.37) | 0.336 | ||

| Respiratory symptoms, n (%) | ||||||

| Cough | 144 (64.3) | 67 (69.8) | 1.23 (0.76 to 2.14) | 0.341 | ||

| Sputum | 112 (49.8) | 56 (58.3) | 1.41 (0.88 to 2.28) | 0.161 | ||

| Wheezing | 159 (70.7) | 72 (76.8) | 1.30 (0.75 to 2.23) | 0.351 | ||

| Dyspnoea | 186 (82.7) | 89 (92.7) | 2.67 (1.14 to 6.19) | 0.023 | 1.68 (0.57 to 4.95) | 0.346 |

| Chest pain | 77 (34.4) | 41 (42.7) | 1.42 (0.87 to 2.32) | 0.158 | 1.50 (0.82 to 2.74) | 0.187 |

| Number of exacerbations in the past year | n=196 | n=127 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–8.5) | 1.6 (1–10) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) | 0.324 | ||

| 0 | 46 (20.4) | 24 (18.9) | 1.00 | |||

| 1–2 | 71 (31.6) | 31 (24.4) | 0.93 (0.45 to 1.95) | 0.850 | ||

| >2 exacerbations | 108 (48.0) | 72 (56.7) | 1.52 (0.79 to 2.92) | 0.211 | ||

| Admitted in the past 1 year due to exacerbations | n=194 | n=127 | ||||

| Yes | 40 (17.9) | 33 (34.4) | 2.41 (1.40 to 4.15) | 0.001 | 2.64 (1.32 to 5.25) | 0.006 |

| Past exacerbation severity | n=196 | n=127 | ||||

| Mild (never visited health facility) | 46 (20.4) | 16 (16.7) | 1.00 | |||

| Moderate (visited facility but not admitted) | 139 (61.8) | 47 (48.9) | 0.97 (0.50 to 1.88) | 0.933 | ||

| Severe (admitted) | 40 (17.8) | 33 (34.4) | 2.37 (1.14 to 4.93) | 0.021 | ||

| HIV status | n=191 | n=126 | ||||

| Positive | 35 (16) | 18 (18.7) | 1.21 (0.65 to 2.27) | 0.546 | ||

| Body mass index (BMI), kg/m2 | n=196 | n=127 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 21.5 (18.6–26.6) | 21.0 (17.0–25.1) | 0.94 (0.90 to 0.99) | 0.012 | ||

| Underweight, that is, BMI<18.5 kg/m2 | 56 (24.9) | 42 (43.75) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Normal, that is, BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 101 (44.9) | 31 (32.3) | 0.41 (0.23 to 0.72) | 0.020 | 0.59 (0.29 to 1.17) | 0.132 |

| Overweight, that is, BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 | 40 (17.8) | 15 (15.63) | 0.50 (0.24 to 1.02) | 0.058 | 0.47 (0.18 to 1.21) | 0.116 |

| Obese, that is, BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 28 (12.4) | 8 (8.3) | 0.38 (1.57 to 0.92) | 0.032 | 0.25 (0.07 to 0.82) | 0.022 |

| History of hypertension | 80 (35.6) | 30 (31.3) | 0.82 (0.49 to 1.37) | 0.457 | ||

| Clinical and biometric characteristics | ||||||

| SPO2 <93% | 72 (32.0) | 59 (61.5) | 3.39 (2.06 to 5.57) | <0.001 | 3.79 (2.05 to 7.00) | <0.001 |

| mMRC ≥2 | 128 (56.9) | 77 (80.2) | 3.07 (1.74 to 5.42) | <0.001 | 2.21 (1.08 to 4.53) | 0.030 |

| Eos % ≥2 | 159 (72.6) | 60 (64.5) | 0.69 (0.41 to 1.15) | 0.154 | 0.62 (0.33 to 1.17) | 0.139 |

| Smoking and biomass exposure | ||||||

| No biomass or tobacco | 25 (11.1) | 20 (20.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Biomass only | 116 (51.6) | 38 (39.6) | 0.41 (0.20 to 0.82) | 0.012 | 0.31 (0.12 to 0.83) | 0.020 |

| Tobacco only | 40 (17.8) | 19 (19.8) | 0.59 (0.27 to 1.32) | 0.203 | 0.32 (0.11 to 0.91) | 0.032 |

| Biomass and tobacco | 44 (19.6) | 19 (19.8) | 0.54 (0.24 to 1.20) | 0.129 | 0.29 (0.10 to 0.83) | 0.021 |

*Adjusted for sex, age, dyspnoea, chest pain, history of admission due to exacerbation, BMI, SPO2, mMRC, eosinophilic count and smoking and biomass exposure.

†Centred around the mean due to multicollinearity.

BMI, body mass index; mMRC, modified medical research council.

Table 2 shows relationships between baseline participants’ characteristics and disease severity (stage III or IV vs stage II or III). The factors significantly associated with severe disease and their aOR (95% CI) were age aOR=0.95 (0.92 to 0.97); exposure to biomass and tobacco smoke, that is, biomass only aOR=0.31 (0.12 to 0.83), tobacco only aOR=0.32 (0.11 to 0.91), and both biomass and tobacco aOR=0.29 (0.10 to 0.83) (reference to no biomass or tobacco); being obese (compared with normal weight) aOR=0.25 (0.07 to 0.82); SPO2 less than 93% aOR=3.79 (2.05 to 7.00); number of exacerbation in the past 1 year aOR=1.01 (1.003 to 1.01); and hospital admission in the past 1 year aOR=2.64 (1.32 to 5.25). The factors which were associated with disease severity but became statistically insignificant after adjusting for other factors were sex (female vs male) unadjusted OR, uOR (95% CI) = 0.59 (0.37 to 0.96); and severity of past exacerbations, that is, having a history of admission uOR (95% CI) = 0.59 (0.37 to 0.96) compared with mild (never visited health facility).

Discussion

In this observational study of 323 patients with COPD who presented to two outpatient health facilities in Uganda, we found that the population with COPD was young, predominantly female, with patients having a high exacerbation frequency, symptom burden and a high HIV prevalence. Biomass exposure was the most ubiquitous risk factor, although tobacco smoke and Pulmonary Tuberculosis (PTB) were also common. Dyspnoea was the most prevalent symptom, followed by wheezing. Regarding disease severity, patients with severe disease had dyspnoea as the most frequent presenting symptom, while those with mild and moderate disease presented with cough as the most prevalent symptom. There was equal distribution concerning the peripheral blood eosinophil count with 50% of the participants having eosinophilia of >3%.

The older, and the patients with obesity had less severe airflow obstruction compared with the younger, and underweight patients. Factors associated with more severe disease were oxygen saturation <93% by oximetry, younger age, mMRC ≥2 and having a history of hospitalisation due to exacerbations.

The clinical characteristics of this cohort seem to differ from those seen in studies from HICs, although direct comparison with cohorts from HICs are difficult. First, there are differences in the healthcare systems, treatment availability and referral processes. Second, there are relatively few studies published on patients with COPD recruited from outpatient clinics in HIC. However, overall populations with COPD from general population studies in HIC recruited from primary care settings report low rates of exacerbations with a majority having GOLD A disease. For example, a study in the UK primary care of over 9000 patients found a mean exacerbation rate of 0.89/year, and the exacerbation rate 1.2/year the ECLIPSE (Evaluation of COPD longitudinally to identify Predicitive Surrogate Endpoints) study.24However, Donaldson et al, in a study population in East London, found a median exacerbation rate of 2.5/year which is comparable to the rate in this cohort, although they relied on diary card recording which usually gives higher results.25 Regarding the distribution of patients by the newer GOLD categories, there was a significant difference in patient distribution in comparison to a UK patient cohort, with this patient cohort having the largest proportion falling under subgroup D (86.2%), and the least proportion in category A (2.2%), while the UK patient cohort had the biggest proportion of their participants falling under group A (36%) and only 25% in group D.24 Additionally, in a study of the combined populations in the ECLIPSE, the COPD gene and the COCOMICS (multicomponent indices to predict survival in COPD study) cohorts: the severity distribution was group A: 32%, group B: 21%, group C: 10% and group D: 37%.26

Regarding patient presentation, wheezing was the second most prevalent presenting symptom after dyspnoea in this cohort, compared with chronic cough and chronic sputum which are the most prevalent presenting symptoms in COPD in HIC where tobacco smoking COPD is predominant. The high prevalence of wheezing is suggestive of an airway predominant phenotype in this population,27 which has been found to be associated with worse symptoms, more exacerbations and worse lung function.28

Paradoxically, in this population, we found that younger age was associated with more severe disease, and this could be because of behavioural-related comorbidities in the young, that contribute to more disease severity.29 Alternatively, this may also be reflective of a survivor effect in older people with milder disease.

The higher proportion of females in this population is akin to findings by Van Gemert et al in a rural setting in Uganda, where women tend to be the primary cooks, and likely have more prolonged and intense exposure to biomass smoke.16This finding is nonetheless like the recent global trends.30 In general, the above findings, ie, young age and disease severity are not entirely unexpected in this population, and may allude to the early life factors that may be at play in the develpment of this case.

Regarding risk factors, biomass smoke was the most prevalent risk factor in this population, and this supports findings from prior studies in Uganda,16 19 and as has been demonstrated by the patterns and trends of COPD in LMICs in relation to HICs.31 14.2% of the participants with COPD reported no history of exposure to tobacco smoke or biomass smoke, and in these cases other factors could be relevant, such as outdoor air pollution, occupational exposures, poor lung growth, childhood infections and poverty and malnutrition.32

The HIV prevalence of 16.7% in this population with COPD was 3 times the current national HIV prevalence in Uganda, and higher than some previous studies conducted among people in Uganda. A meta-analysis of studies in the global setting found that around 10% of people with HIV had COPD.33 As the population with HIV survives longer, thanks to antiretroviral therapy, COPD is more likely to occur. HIV also predisposes the patient with HIV to acute and chronic respiratory tract infections.34

A history of PTB was present in 22% of participants, and PTB being associated with obstructive lung disease, could be the underlying risk factor for COPD in this patient group.35 36 This would thus place them under the COPD-1 aetiotype as per the GOLD 2023 taxonomic classification.1 This is supported by findings from studies conducted prior in this setting, evaluating the burden of COPD in both rural and urban Uganda conducted by Kayongo et al and Ddungu et al, respectively.37 38 Similar findings have been demonstrated globally,36 and highlight the need for TB control as a strategy for alleviating the burden of COPD in this setting where the TB prevalence is high.39

The inhaler therapy use in this population was low when compared with the HIC setting in Refs 40 41. This is not surprising given the low availability of both monotherapies and combination inhaler therapies in this setting, with less than 50% availability in most health facilities and pharmacies.42 These medications are also largely unaffordable to these patients as it costs up to 3 days wages to afford the monthly cost of treating COPD.43 This highlights the need to find affordable treatment options for these patients, or policy-level interventions to subsidise inhaler costs in this setting.

The main limitation of the study is the cross-sectional design of the analysis. For logistic reasons, we did not use imaging or evaluate full lung function tests to evaluate aspects like reduced lung volumes in the aetiology of COPD in this patient cohort. The other limitation is that the participants enrolled were from tertiary facilities and as such, they may not be entirely representative of the general population of patients with COPD. Also, we were not able to take a detailed history of exposures and exposures in childhood and to the fetus, which may be relevant.

Conclusion

Patients with COPD in this Ugandan referral hospital population have specific characteristics including younger patient age, presentation with dyspnoea and wheeze, frequent exacerbations and biomass smoke being the most prevalent exposure than seen in HIC settings. HIV infection and a history of Pulmonary Tuberculosis are common among these patients, and therefore more attention should be accorded to COPD screening and COPD care by HIV and TB healthcare providers in this setting. More research is needed to better understand interplay of early life factors and poverty in the development of COPD in this setting, the pathophysiological mechanisms at play in view of the unique risk factor profile, and how these translate to the preventative and therapeutic approaches in this COPD phenotype.

bmjresp-2023-001816supp001.pdf (50.6KB, pdf)

Acknowledgments

Dr Jalia Nanyonga who led the clinic team that participated in the study. Rogers Sekibira who helped with the data management. The patients that participated in this COPD study.

Footnotes

Twitter: @alupo_patricia

Contributors: PA, BK and RJ conceived the work and designed the work. LM and JN helped with statistical methods and data analysis and interpretation, PA and WK were involved in data acquisition and interpretation. PA drafted the first manuscript draft, and BK, RJ and JH critically reviewed the first draft. BK, RJ, JH, LM, WK, AK, JN and TS critically reviewed subsequent versions, and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript. PA is acting as the guarantor of the study.

Funding: The study was funded by GSK (GSK Africa NCD open Lab), grant number 8868.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Mulago Hospital Research and Ethics Committee MHREC 1451, and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS 2483). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Agustí A, Celli BR, Criner GJ, et al. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease 2023 report: GOLD executive summary. Eur Respir J 2023;61:2300239. 10.1183/13993003.00239-2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The top 10 causes of death, Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death

- 3. Meghji J, Mortimer K, Agusti A, et al. Improving lung health in low-income and middle-income countries: from challenges to solutions. Lancet 2021;397:928–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00458-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Safiri S, Carson-Chahhoud K, Noori M, et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMJ 2022;378:e069679. 10.1136/bmj-2021-069679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoo SH, Lee JH, Yoo KH, et al. Different pattern of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test score between chronic Bronchitis and non-chronic Bronchitis patients. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2018;81:228–32. 10.4046/trd.2017.0088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Calle M, et al. Spanish guideline for COPD (gesEPOC). Archivos de Bronconeumología (English Edition) 2014;50:1–16. 10.1016/S1579-2129(14)70070-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Han MK, Agusti A, Calverley PM, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes: the future of COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:598–604. 10.1164/rccm.200912-1843CC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miravitlles M, Calle M, Soler-Cataluña JJ. Clinical phenotypes of COPD: identification, definition and implications for guidelines. Archivos de Bronconeumología (English Edition) 2012;48:86–98. 10.1016/j.arbr.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Agusti A, Bel E, Thomas M, et al. Treatable traits: toward precision medicine of chronic airway diseases. Eur Respir J 2016;47:410–9. 10.1183/13993003.01359-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Awokola BI, Amusa GA, Jewell CP, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2022;26:232–42. 10.5588/ijtld.21.0394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Njoku CM, Hurst JR, Kinsman L, et al. COPD in Africa: risk factors, Hospitalisation, readmission and associated outcomes—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2023;78:596–605. 10.1136/thorax-2022-218675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adeloye D, Song P, Zhu Y, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and Modelling analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2022;10:447–58. 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00511-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hurst JR, Siddharthan T. Global burden of COPD. In: Haring R, Kickbusch I, Ganten D, et al., eds. Handbook of Global Health. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020: 1–20. 10.1007/978-3-030-05325-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mehra D, Geraghty PM, Hardigan AA, et al. A comparison of the inflammatory and proteolytic effects of dung Biomass and cigarette smoke exposure in the lung. PLoS One 2012;7:e52889. 10.1371/journal.pone.0052889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Gemert F, Kirenga B, Chavannes N, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and associated risk factors in Uganda (FRESH AIR Uganda): a prospective cross-sectional observational study. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e44–51. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70337-7 Available: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70337-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Tabyshova A, Hurst JR, Soriano JB, et al. Gaps in COPD guidelines of low-and middle-income countries: a systematic Scoping review. Chest 2021;159:575–84. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.09.260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alupo P, Wosu AC, Mahofa A, et al. Incidence and predictors of COPD mortality in Uganda: A 2-year prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2021;16:e0246850. 10.1371/journal.pone.0246850 Available: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. The Uganda Registry for asthma and COPD (URAC) project.

- 21. Miller MR. ATS/ERS task force: Standardisation of Spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38. 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Graham BL, Steenbruggen I, Miller MR, et al. Standardization of Spirometry 2019 update: An Official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society Technical Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;200:e70–88. 10.1164/rccm.201908-1590ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for Spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1324–43. 10.1183/09031936.00080312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hurst JR, Anzueto A, Vestbo J. Susceptibility to exacerbation in COPD. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5:S2213-2600(17)30307-7. 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30307-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Donaldson GC, Seemungal TAR, Bhowmik A, et al. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2002;57:847–52. 10.1136/thorax.57.10.847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marin JM, Alfageme I, Almagro P, et al. Multicomponent indices to predict survival in COPD: the COCOMICS study. Eur Respir J 2013;42:323–32. 10.1183/09031936.00121012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Camp PG, Ramirez-Venegas A, Sansores RH, et al. COPD phenotypes in Biomass smoke-versus tobacco smoke-exposed Mexican women. Eur Respir J 2014;43:725–34. 10.1183/09031936.00206112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang W-C, Tsai Y-H, Wei Y-F, et al. Wheezing, a significant clinical phenotype of COPD: experience from the Taiwan obstructive lung disease study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:2121–6. 10.2147/COPD.S92062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Divo MJ, Marin JM, Casanova C, et al. Comorbidities and mortality risk in adults younger than 50 years of age with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res 2022;23:267.:267. 10.1186/s12931-022-02191-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Somayaji R, Chalmers JD. Just breathe: a review of sex and gender in chronic lung disease. Eur Respir Rev 2022;31:163.:210111. 10.1183/16000617.0111-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hurst JR, Siddharthan T. Global burden of COPD: prevalence, patterns, and trends. Handbook of Global Health 2020;1–20. 10.1007/978-3-030-05325-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mahmood T, Singh RK, Kant S, et al. Prevalence and Etiological profile of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Nonsmokers. Lung India 2017;34:122–6. 10.4103/0970-2113.201298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bigna JJ, Kenne AM, Asangbeh SL, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the global population with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e193–202. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30451-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Asiki G, Reniers G, Newton R, et al. Adult life expectancy trends in the era of antiretroviral treatment in rural Uganda (1991-2012). AIDS 2016;30:487–93. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Byrne AL, Marais BJ, Mitnick CD, et al. Tuberculosis and chronic respiratory disease: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis 2015;32:138–46. 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fan H, Wu F, Liu J, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis as a risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med 2021;9:390. 10.21037/atm-20-4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kayongo A, Wosu AC, Naz T, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevalence and associated factors in a setting of well-controlled HIV, a cross-sectional study. COPD 2020;17:297–305. 10.1080/15412555.2020.1769583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ddungu A, Semitala FC, Castelnuovo B, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevalence and associated factors in an urban HIV clinic in a low income country. PLoS One 2021;16:e0256121. 10.1371/journal.pone.0256121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Foo CD, Shrestha P, Wang L, et al. Integrating tuberculosis and Noncommunicable diseases care in low-and middle-income countries (Lmics): A systematic review. PLoS Med 2022;19:e1003899. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Calverley PMA. Meeting the GOLD standard: COPD treatment in the UK today. EClinicalMedicine 2019;14:3–4. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raluy-Callado M, Lambrelli D, MacLachlan S, et al. Epidemiology, severity, and treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the United kingdom by GOLD 2013. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:925–37. 10.2147/COPD.S82064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kibirige D, Kampiire L, Atuhe D, et al. Access to affordable medicines and diagnostic tests for asthma and COPD in sub Saharan Africa: the Ugandan perspective. BMC Pulm Med 2017;17:179. 10.1186/s12890-017-0527-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Siddharthan T, Robertson NM, Rykiel NA, et al. Availability, Affordability and access to essential medications for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in three low-and middle-income country settings. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022;2:e0001309. 10.1371/journal.pgph.0001309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjresp-2023-001816supp001.pdf (50.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.