Abstract

Background

Dysphagia impacts negatively on quality of life, however there is little in‐depth qualitative research on these impacts from the perspective of people with dysphagia.

Aims

To examine the lived experiences and views of people with lifelong or ongoing dysphagia on the impacts of dysphagia and its interventions on quality of life, and barriers and facilitators to improved quality of life related to mealtimes.

Methods & Procedures

Nine adults with lifelong or acquired chronic dysphagia engaged in in‐depth interviews and a mealtime observation. The observations were recorded and scored using the Dysphagia Disorders Survey (DDS). Interviews were recorded, transcribed and de‐identified before content thematic and narrative analysis, and verification of researcher interpretations.

Outcomes & Results

Participants presented with mild to severe dysphagia as assessed by the DDS. They viewed that dysphagia and its interventions reduced their quality of life and that they had ‘paid a high price’ in terms of having reduced physical safety, reduced choice and control, poor mealtime experiences, and poor social engagement. As part of their management of dysphagia, participants identified several barriers to and facilitators for improved quality of life including: being involved in the design of their meals, being adaptable, having ownership of swallowing difficulties, managing the perceptions of others and resisting changes to oral intake.

Conclusions & Implications

This research improves understanding of the primary concerns of people with dysphagia about their mealtime experiences and factors impacting on their quality of life. Clinicians working with people with dysphagia need to consider how self‐determination, autonomy and freedom of choice could be improved through involvement in food design of texture‐modified foods. It is important that future research considers the views of health professionals on how these findings could impact on policy and practice particularly in ways to address the barriers and enhance facilitators to improved quality of life for people with dysphagia.

What this paper adds

What is already known on the subject

Dysphagia impacts on quality of life, particularly as the severity of the dysphagia increases. Research to date has focused on people with dysphagia associated with an acquired health condition and has used quantitative assessment methods to measure quality of life.

What this paper adds to existing knowledge

This study provides a qualitative examination of the impacts of dysphagia on quality of life from the perspective of people with lifelong or ongoing acquired dysphagia and their supporters. This study also provides qualitative insights into the barriers and facilitators of mealtime‐related quality of life.

What are the potential or actual clinical implications of this work?

Health professionals should engage in open communication with their clients with dysphagia regarding the impacts of dysphagia on their lifestyle and quality of life. By considering these impacts, health professionals may be able to recommend interventions that are more acceptable to the person with the dysphagia which may have a positive impact on their mealtime experience.

Keywords: dysphagia, quality of life, interviews

INTRODUCTION

Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and its interventions can significantly impact on a person's physical health as well as their quality of life, participation and inclusion (Smith et al., 2022a). Dysphagia is associated with a wide range of health conditions, including developmental disabilities (e.g., cerebral palsy or intellectual disability) and acquired health conditions (e.g., stroke, Parkinson's or motor neuron disease) (Groher & Crary, 2016). Estimates suggest that approximately 8% of the world's population has dysphagia (Cichero et al., 2017; Groher & Crary, 2016), and that prevalence increases in particular populations; for example, the estimated prevalence of dysphagia in older people living in aged care facilities is 52.7% (Engh & Speyer, 2022). Despite this, the impacts of dysphagia on quality of life are under‐researched (Smith et al., 2022a). Quality of life is defined as a person's understanding of their position in life regarding their environmental and cultural context (World Health Organisation, 1998). When examining quality of life of people with dysphagia, mealtime participation should be considered, particularly to appreciate how the person with dysphagia engages in mealtime activities (e.g., choosing their meal), with different people and in different mealtime environments (Balandin et al., 2009).

The significant negative health impacts of dysphagia, for example, on respiratory health or nutrition (Broz & Hammond, 2014), can have further impacts on the person's health‐related quality of life. Dysphagia can lead to dehydration and malnutrition (Broz & Hammond, 2014), along with choking events and hospitalization (Hemsley et al., 2019). Dysphagia interventions (e.g., modifying food textures, positioning modifications, or modified equipment) are designed to reduce risk to the person's health and increase efficiency in the swallow through rehabilitation or compensation strategies (Groher & Crary, 2016; Wu et al., 2020). Texture‐modified foods are frequently recommended and used as a compensatory strategy for people with dysphagia, such that foods are softer and fluids may be thickened to reduce the risk of choking (Steele et al., 2015). Although texture‐modified food is provided to increase health and reduce the risk to nutritional or respiratory health, it may also impact on a person's quality of life. Texture‐modified foods may increase a person's mealtime‐related quality of life if they can eat meals without choking, or could decrease mealtime‐related quality of life if it restricts their access to preferred or familiar foods outside the recommended textures (Smith et al., 2022a).

Prior literature on the impacts of dysphagia on quality of life

A prior scoping literature review informed this research (Smith et al., 2022a). Following a published protocol (Smith et al., 2019), the review included 106 studies analysed according to the Health Related Quality of Life Model (HRQOL) (Ferrans et al., 2005) to examine the peer‐reviewed evidence on the impacts of dysphagia and its interventions on quality of life, participation and inclusion of people with dysphagia (Smith et al., 2019). The HRQOL model describes quality of life as being influenced by the person's functional status along with environmental and individual characteristics that shape their perceived health (Ferrans et al., 2005). The vast majority of studies reviewed related to adults with acquired conditions (n = 95, 90%) and only seven (7%) related to people with lifelong dysphagia. Furthermore, 44 of the included original research studies involved the application of quantitative assessments of quality of life and did not use qualitative methods offering in‐depth insights into the impacts of dysphagia from the perspective of people with dysphagia or their supporters.

Nonetheless, across this large body of prior research, the central finding from prior research was that dysphagia negatively impacts the affected person's quality of life, increasing as the severity of the dysphagia increased (Smith et al., 2022a). However, dysphagia interventions also impact on quality of life, with 25 of the 32 intervention studies examining the impact showing that the interventions improved quality of life, but this was not always the case. Enteral tube feeding had both positive and negative impacts as it helped maintain physical health but was also isolating (Ang et al., 2019; Stavroulakis et al., 2016). Texture‐modified food similarly had positive and negative impacts on quality of life (Seshadri et al., 2018) as the appearance of the foods made people feel self‐conscious and excluded from others (Shune & Linville, 2019).

To understand the impact of modifying food textures on perceptions of food or mealtime enjoyment, a recent narrative review of 35 studies examined how visual appeal, texture, taste, smell, temperature and mealtime environment may impact the mealtime experience for people with dysphagia (Smith et al., 2022b). The authors reported that the use of food moulds, piping bags, spherification, gelification, or 3D food printing may help improve the appeal of texture‐modified foods. However, only 17 of the 35 studies included participants with dysphagia and only one of these included people with a lifelong swallowing disability. Furthermore, only six of the studies with participants with dysphagia were qualitative studies, shedding little light on the lived experiences of people with dysphagia (Smith et al., 2022b). Consequently, further evidence is needed to determine the extent of the impacts of food design on the lived mealtime experiences of people with lifelong or ongoing dysphagia. Understanding more about how people with dysphagia view the impacts of dysphagia on quality of life will help to design person‐centred interventions (Howells et al., 2019a). To fill the gaps in the literature relating to the views of people with dysphagia and their supporters on the impact of dysphagia and its interventions on quality of life, the aims of this study were to examine the views and lived experiences of people with lifelong or ongoing dysphagia on (1) the impacts of dysphagia and its interventions on quality of life, participation, and inclusion and (2) the barriers and facilitators to HRQOL and mealtime‐related quality of life.

METHODS

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the University Human Research Ethics Committee (ETH19‐3708). An interpretive, constructivist grounded theory approach was taken to enable the exploration and integration of data from a variety of sources (Charmaz, 2017; Mills et al., 2006) in seeking to understand the impacts of dysphagia on quality of life, from the perspectives of people with dysphagia and their supporters. This approach also took into account their dysphagia severity based on an observational mealtime assessment using the Dysphagia Disorders Survey (DDS) and Dysphagia Management Staging Scale (DMSS) (Sheppard et al., 2014). The methods used in this study were selected in order to inform and integrate with future studies obtaining the views of allied health professionals on the quality‐of‐life impacts of dysphagia, as part of a larger doctoral research project of the first author. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) were used to report findings (O'Brien et al., 2014). The mixed‐methods study involved observations of each participant eating a typical meal to describe their dysphagia severity and management using the DDS and DMSS (Sheppard et al., 2014). Following this, in‐depth interviews explored participants’ views on the impacts of dysphagia and texture‐modified food on their quality of life. In addition, where available, document data analysis of the participant's mealtime plans or speech pathology reports was used to triangulate and verify information relating to their diet and dysphagia. During COVID‐19 restrictions, observations, and interviews were conducted and recorded online using Zoom (Zoom Video Communications Inc., 2011) for all but one participant (P6), who was interviewed in person at home.

Participants

Participants were eligible to take part if they were capable of giving written informed consent to participate; able to read, speak, and understand English; had dysphagia; and were on a texture‐modified diet. All the participants volunteering to participate in the study and providing informed consent were included. While all reported having had dysphagia for more than one year, five reported having had dysphagia for more than 10 years. Participants were recruited using purposeful and theoretical sampling methods by contacting local organizations supporting people with disability and older people with dysphagia and by distributing information about the study through social media networks. As it is not possible to determine how many people saw the information advertising the study, a recruitment response rate could not be determined. Cultural heritage and background of participants was not collected beyond that which they raised or referred to in their own interviews. The first author knew one participant (P2) before her involvement in the study. All participants were aware of the first author's position as a female speech and language therapist with clinical experience in dysphagia management; and as a doctoral candidate conducting qualitative research. Her experience as a speech and language therapist, as well as having reviewed the prior literature on quality of life, was acknowledged as informing her stance on participants having a lived experience that was important to gather in relation to their quality of life. Interpretive and constructivist approaches to research recognize that reality is subjective and the researchers in this study acknowledged that their experiences as speech and language therapists shaped the interpretation of the data while acting as a facilitator to gather the perspectives of participants (Mills et al., 2006). Participants were given an AU$30 gift voucher for their time.

Participants presented with dysphagia associated with a range of health conditions ranging from mild dysphagia (P1 and P9) to severe (P7) dysphagia. Demographic information about participants including age, condition associated with dysphagia, dysphagia severity and living arrangements are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Participant demographic information

| Participant ID | Gender | Age (years) | Dysphagia aetiology | Dysphagia severity (DDS) | Current diet (IDDSI) | Type of residence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | M | 30 | Klinefelter Syndrome | Mild | Soft and bite‐sized food, carbonated thin fluids | Private home |

| P2 | F | 80 | Age‐related changes and a pharyngeal pouch | Moderate–severe | Easy to chew and soft foods, thin fluids | Private home |

| P3 | F | 54 | Traumatic brain injury | Moderate–severe | Soft and bite‐sized food, thin fluids | Private home |

| P4 | F | 42 | Athetoid cerebral palsy | Moderate | Soft and bite‐sized food, thin fluids | Private home |

| P5 | F | 55 | Head and neck cancer | Moderate–severe | Soft and bite‐sized food, thin fluids | Private home |

| P6 | F | 55 | Pierre Robin Anomaly | Mild–moderate | Soft and bite‐sized food, thin fluids | Group home |

| P7 | M | 81 | Dementia and age‐related changes | Severe | Soft and bite‐sized food (diabetes), thin fluids | Aged care facility |

| P8 | M | 76 | Inclusion body myositis | Moderate | Regular/easy to chew foods and thin fluids | Private home |

| P9 | M | 77 | Inclusion body myositis | Mild | Regular foods and thin fluids | Private home |

Note: DDS, Dysphagia Disorder Survey; F, female; IDDSI, International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative; M, male; P, participant.

The nine participants were aged from 30 to 81 years with a median age of 55 years. Two participants, P8 and P9, had chronic myositis, a condition associated with dysphagia due to inflammation of muscles of the oesophagus and oropharynx which may also increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia (Oh et al., 2008). Seven participants lived in private homes in the community, one lived in a group home and one lived in an aged care facility. Of the nine participants, two were interviewed with one or more supporters present. They assisted the person with dysphagia to engage in the interview and provided any supplementary or further information on past events as requested by the participant (Lisiecka et al., 2021). Specifically, P7's spouse and P6's three supporters (a parent and two paid support workers) provided such support playing a minor part only in the interview as required.

Procedures

Mealtime observation

The observational assessment of mealtimes provided important contextual evidence of the nature and severity of participants’ dysphagia, which in turn provided context informing the views of the participants in relation to their dysphagia and its impacts on their quality of life. At a time of the participant's choosing, a member of the research team (first or last author) observed the participant eating a typical meal in their regular mealtime environment, using an iPad or mobile phone on a Zoom call for this to be viewed and recorded. While safety protocols (e.g., in the event of food choking) were in place in case of an adverse event (see Appendix A), no safety incidents occurred during or after the observations. Using the video recording taken of the meal, the DDS and DMSS were completed by the first and last authors who are both certified users, to provide a description of each participant's mealtime difficulties (Sheppard et al., 2014). The use of Zoom in this research during COVID‐19 was selected as suitable, as such telehealth procedures are reported to be a viable clinical modality for the assessment of dysphagia (Ward & Burns, 2014), particularly during COVID‐19 (Malandraki et al., 2021).

Mealtime document review

Four of the participants provided a copy of available written reports (e.g., swallowing clinical assessment report, instrumental assessment report) and mealtime plans to the researcher to include as historical and documented context to their perspectives (Patton, 2014). A document data‐extraction form was used to extract and collate relevant information about the participants (see Appendix B).

In‐depth interviews

Each of the 60 minute interviews were conducted by the first author, who had experience in conducting qualitative interviews, between September 2020 and December 2021. The interviews were designed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the participants’ views on the impacts of dysphagia on quality of life. Recognizing the diversity and heterogeneity of people with dysphagia, the researchers aimed to recruit participants until theoretical saturation was reached (Guest et al., 2006). While content themes were strong in the interviews analysed, saturation was not achieved due to difficulties with recruitment during the COVID‐19 pandemic, owing to substantial impacts on the health and disability support sectors with social distancing restrictions.

The first author conducted the conversational‐style in‐depth interviews using an interview protocol, developed on the basis of two prior literature reviews (Smith et al., 2022a, 2022b). While the interview guide was designed to ask similar questions across interviews, the conversational style of the interview meant that probing questions could be modified according to the participant's relevant lived experiences (see Appendix C). The first interview served as a pilot of the interview schedule which did not require changes and was fit for purpose as it allowed for individual responses throughout the interview. After the interview, the researcher made detailed field notes on her observations and insights gained to help guide the initial stages of analysis.

Content thematic and narrative analysis

Interviews were de‐identified and transcribed verbatim by the first author. NVivo (QSR International, 2018) was used for the coding, storage and retrieval of the data. Analysis involved thematic content analysis with open coding, identifying categories across those codes and matrix coding was conducted (Patton, 2014). Open coding, which involved identifying units of meaning within the data, was based on a reading and re‐reading of each text and identifying units of meaning, and discussing these across the research team. The authors discussed categories of meaning that connected the codes, and matrix coding which involved looking for relationships that connected the open codes, and any concepts that helped to explain the meaning both within and across the participants’ interviews. Any themes connecting the data within and across participants are referred to as ‘content themes’ that are built or constructed across the participant group (Charmaz, 2017).

A narrative analysis of the data was also undertaken to identify and fully appreciate the views and lived experiences of participants (Crossley, 2007). In this process, the researcher first located stories within the interview transcripts, identifying explanations of events and situations and any story themes that could add to the content analysis (Riessman, 2007). In their interviews, participants were encouraged to narrate mealtime events, problems and resolutions, along with explaining their own interpretation of what their experiences meant to them (Crossley, 2007; Riessman, 2007). This narrative analysis enabled participants’ stories of experience to be appreciated and highlight specific situations where their quality of life had been impacted and what they had done in response. The stories contributed an understanding of important elements of time, sequence of events, and approaches to problem‐solving around their lived experiences of dysphagia.

Field notes written by the first author after each data collection event were also used in the analysis process and added to the NVivo file for coding. Each transcript was read and re‐read by the researchers to ensure the accuracy of coding. Researchers also frequently engaged in discussion about the transcripts and to ensure they agreed that the categories and codes developed reflected the interview transcripts. The first author wrote a summary interpretation and discussed this with co‐authors to confirm interpretations and reduce researcher bias and ensure trustworthiness (Morgan et al., 1998). Each participant was emailed the written summary of the researchers’ agreed interpretations which highlighted the content themes and stories of experience to verify the researchers’ interpretations. Participants were asked to confirm the interpretations, to suggest changes or additions to better reflect their view. In total, six participants responded to confirm the information either by sending an email (n = 5) or in a short face‐to‐face online interview (n = 1).

RESULTS

At their convenience, all participants were observed eating a lunchtime meal which, for completion of the DDS, included their usual chewable food, non‐chewable food and a drink. In terms of positioning for the observed meal, P7 sat in a recliner chair, and all others were seated at a table. P6 required some assistance for eating with some hand over hand assistance provided, and P7 was mostly dependent requiring full support (i.e., unable to hold the spoon). P5 and P6 used adaptive plastic cutlery. The severity of dysphagia as determined using the DDS is presented in Table 1 and ranged from mild to severe.

Mealtime documents provided by four of the participants included instrumental barium swallow assessment reports (P1 and P2), clinical speech pathology and dietetics assessment reports (P1 and P6), and mealtime plans written by a speech pathologist (P4 and P6). Both mealtime plans and P6's clinical speech pathology assessment report provided information regarding mealtime participation and inclusion. For example, P4's plan stated ‘[Participant] knows what she can and cannot eat and will choose her own meals based on what she feels like’, while P6's mealtime plan gave recommendations for foods to avoid including bread and watermelon.

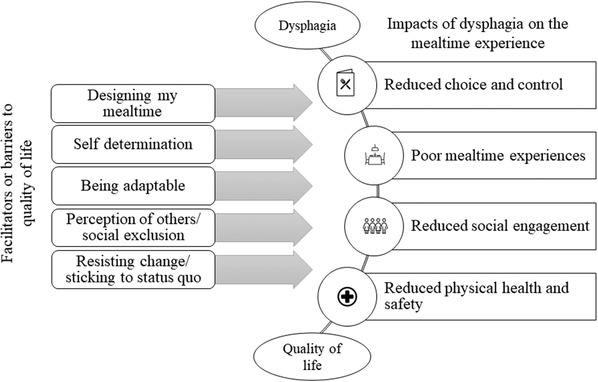

Across the interviews, and perhaps reflecting the relatively small sample size, there were two major connecting themes, one encapsulating four content themes and the other five themes. The first major connecting theme related to ‘costs on quality of life’, in that dysphagia is associated with substantial costs to mealtime‐related quality of life, and participants had to ‘pay the price’ of dysphagia in four main thematic areas, in terms of their: choice and control, mealtime experiences, social engagement, and physical health and safety. The second major connecting theme related to dysphagia management impacting on the quality of life and included themes of designing my mealtime, self‐determination of swallowing difficulties, adaptability at mealtimes, the perceptions of others, and sticking to the status quo or resisting change. The way these content themes impacted their mealtime‐related quality of life and mealtime experiences is conceptualized in Figure 1. The two overarching connecting themes and the four main content themes, along with barriers and facilitators to quality of life, are presented in detail in the following section with supporting quotes to increase the plausibility and confirmability of the findings (Patton, 2014).

FIGURE 1.

Facilitators, barriers, and impacts on quality of life

Paying the price for dysphagia: Impacts on quality of life

The cost of dysphagia on health and safety

All participants described choking or almost choking (i.e., a near miss event), often in public, reflecting the threat of dysphagia to their health and safety. P8 described a time where he choked on a chocolate bar, noting that ‘it didn't end well’. He also described the length of time it often takes to clear his throat, ‘if I get something small stuck in my throat, I go into a coughing fit and that might take me 5, 10 minutes to get over’. In comparison, P3 described choking on potato while eating at a café with colleagues and a nearby doctor administered the Heimlich manoeuvre. P3 recalled how ‘embarrassing’ the situation was, but also how ‘relieved’ she was that someone came to her aid. Such narratives illustrate the interconnected nature of the impacts of dysphagia on health and safety, social engagement in terms of choking occurring in social situations and being embarrassing, and reliance on others particularly in relation to choking rescue.

Participants described the cost of dysphagia and texture‐modified food on quality of life, when they could not maintain their physical health through an appropriate diet. P5 described the difficulties she had faced maintaining her physical health whilst facing a new dysphagia diagnosis. After chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery for head and neck cancer, P5 had difficulties maintaining weight due to her dysphagia. She reported that eating ‘takes forever, and you never put on weight cos you can't eat that much’. Similarly, gaining appropriate nutrients from food was an ongoing challenge for P7 and his wife who reported ‘I can feed P7 yeah sweets and mousses and things all, any day of the week’, however he would often refuse savoury texture‐modified food based on the smell or taste. To accommodate for this, his wife supplemented the food provided at his facility by bringing him bananas and avocados from home. P7's wife recognized that these foods did not replace the nutrients he missed from vegetables and proteins, but it was better than skipping the meal. This demonstrated the importance of the support network in supplementing a person's diet.

The cost of dysphagia on choice and control

A number of participants described times when their choice was reduced because of their swallowing difficulties. P6 did not cook her own meals and required significant support from support staff to cook appropriate food for her swallowing needs. However, P6 enjoyed helping by choosing meals and by holding the support workers hand to stir food or peel vegetables. P2 described how her choice was limited when eating out for morning tea as she would only have coffee to reduce the risk of choking in front of others. She also described ordering dessert when out for dinner with family as the dessert options were often easier to swallow than the main meals. Although her food choices were reduced in these situations, P2 had come to terms with these changes, ‘years ago I would have felt out of it if I didn't follow everyone but that doesn't even register with me anymore. I just have what I have to have’.

The loss of choice and control appeared to have a greater impact on participants who had acquired dysphagia in adulthood in comparison to those who had lived with swallowing difficulties since childhood. P7 previously enjoyed cooking and sharing food with others, his wife stated, ‘people still ring up and say to me, “oh I remember P7's curries”’. P7 loss of mealtime choice and control was not only based on the textures he could eat, he was also generally limited to foods provided by the aged‐care facility that were not always to his taste and he could not see his food due to a vision impairment. In comparison, P4, who has lifelong dysphagia, said ‘I think it has just been part of my life just like all the other fun aspects of CP [cerebral palsy]’. Although she would have preferred to have better swallowing skills, she had learned to accept that swallowing difficulties as part of her life and consequently she avoided some foods (e.g., nuts and chips).

The cost of dysphagia on food and the mealtime experience

Texture modification had a substantial impact on the mealtime experience for participants. P1 and P5 in particular reported that the visual appeal of their meal impacted on their enjoyment. As P5 stated, ‘I'm a foodie, I come from a food and wine background, and it's like I really don't want to eat vitamised Big Mac and fries, thanks very much’. She then reinforced this and stated, ‘all the food is like wet dog food’ (P5). This highlighted how limited effort was exerted in adapting foods for people who require texture‐modified food. P1 also described reheating his food during a meal due to his extended eating time. As a result of constant re‐heating, his food was often soggy and no longer maintained its original form. P8 described taking extra time to eat meals and this detracted from the mealtime experience when eating out, ‘now it takes a lot longer. Whereas before I was always first finished eating. But now having to cough up in front of people … it's something that I'd prefer not to do’. Participants also agreed that mealtimes were a ‘chore’ due to their swallowing difficulties. For example, P3 described mealtimes as a chore ‘unless I am with really good friends or family’ to cut the food up. Participants reported avoiding or restricting their access to specific foods or mealtime environments because of their swallowing difficulties. For example, P6 could no longer have her favourite meal of curry with naan bread as bread had been removed from her diet.

The cost of dysphagia on social engagement

Dysphagia impacted on participants’ feelings associated with eating with others. P2 reported she felt nervous when eating out with others and said she was ‘just super careful and you try to order something that's easy’ so she did not draw attention to herself. P4 was also careful when ordering out, but she was driven by her mother, ‘I try and order appropriate foods in order to avoid Mum's death stares’. This demonstrates the tension associated with swallowing difficulties and food choices when eating in a social environment. P1 described how his swallowing difficulties shaped how others perceived him. For example, when describing his difficulties ordering appropriate food out, he said ‘it makes me look like a drama queen’. P1 also described how the reactions of others shaped his social experiences, ‘as much as it was fun occasionally pulling things out of my nose that I'd swallowed and do my party trick … they thought it was hilarious every time cos they were laughing at me as opposed helping’.

Dysphagia also impacted on participants’ decisions regarding their attendance at social events. P3 declined event invites if the food being served was not appropriate. P3 found cocktail parties the most difficult and said there is ‘nowhere to sit and nowhere to put food’. In making these decisions, P3 also considered other comorbidities she faced including difficulties with mobility and communication. P5 was also reluctant to attend social gatherings, ‘I've missed weddings of my own family, I've missed sixtieths, fiftieths, christenings, baby I have missed them all’. P5 reported feeling ‘pressure’ when eating out and preferred trying new foods at home as she did not have to follow social etiquette (e.g., she could clear food from her mouth with a finger sweep).

Management of dysphagia

Participants described mealtime management‐related factors that could be manipulated or modified to improve or reduce mealtime quality of life, which are depicted on the left‐hand side of Figure 1. These factors can change or be adjusted to form either a barrier or a facilitator to a person's mealtime related quality of life. Factors serving as both barriers and facilitators to quality of life included the person's involvement in designing their own meal, taking ownership of their swallowing difficulties, being adaptable, the opinions of others, and resistance to changes involving skills and food.

Designing my mealtime: Autonomy and control influencing quality of life

Participants used different strategies to modify flavour, environment and assistance received in attempts to make their mealtimes more enjoyable, and a failure to implement these strategies led to reduced quality of life. P1 reported that he added herbs and spices to his meals to improve the flavour, and different colours to improve the visual appeal, ‘sometimes I put food colouring in things … sometimes I add purple carrot instead of orange’. P9 similarly discussed the importance of the food's flavour and said, ‘when it's really tasty … I almost don't think about the swallowing part of it when I'm eating’. Mealtimes for P7 were also based around the taste and smell of food due to his vision impairment. P7 reportedly refused meals based on smell and so his wife focused on flavours and smells he enjoyed to ensure he received enough nutrients. For example, P7's wife saved lunchtime sandwiches in case P7 refused his dinner. In comparison, P6 designed her mealtimes by telling the support workers or her mother what she wanted to eat, and they accommodated her requests in line with her mealtime plan. P6's group home manager encouraged these choices and said, ‘she loves helping which great because it's her meal’. P6 also chose the mealtime environment when staying with her mother, ‘she sets down little requirements like we should have dinner in the dining room not the kitchen’.

The use of different cutlery and crockery was another way for participants to design their own mealtime experience. P5 used decorative crockery to improve the visual appeal of her meals and stated, ‘I tend to err on the side of, get yourself a beautiful bowl, get yourself a beautiful plate’. By choosing crockery of different colours and sizes, P5 could moderate her portion sizes when transitioning from percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) to oral feeds. P5 also used the plastic spoon provided by the hospital speech and language therapist and Chinese soup spoons as she could not tolerate metal cutlery after chemotherapy.

P3 and P4 often relied on mealtime assistance from others to improve their mealtime experience. P3 asked restaurant wait staff to cut up her meal before bringing it to her as this gave her more time to focus on eating her meal without asking someone at her table for help. Similarly, P4 relied heavily on assistance from her mother and support workers to prepare meals. P4 accepted this assistance and was happy for someone else to be in control of meals, ‘I guess because I can't really do it and because I'm too busy thinking about other things’.

Self‐determination and ownership of swallowing difficulties

Participants with dysphagia handled ownership of swallowing difficulties and the consequences of dysphagia in different ways. P1 described how he took control and involved himself in his dysphagia management: ‘[allied health professionals] must be able to work as part of a multidisciplinary team in conjunction with me’. P9 also took ownership of his own mealtime enjoyment and said ‘the psychology works for me … [I] think about I'm really enjoying this mouthful of food. And it seems to go down easier’. P3 described re‐claiming ownership of her dysphagia management during a hospital admission, as she was placed on a texture‐modified diet that was more modified than food she typically ate. She said, ‘the catering staff on supper even refused to give me a biscuit cos of modified diet so I demanded to come off it’. If P3 had not taken this ownership, she reported her quality of life would have been reduced against her wishes.

P2 and P4 demonstrated self‐determination by refusing to let their swallowing difficulties impact on their attendance at social gatherings. P2 said ‘we don't go out that much and I do look forward to it when we do’. Hence, her decision to attend social events was not shaped by her swallowing difficulties but by the general well‐being of herself and her elderly husband. P4 similarly did not let swallowing difficulties impact on her decisions. P4 agreed that her lifelong experiences with dysphagia shaped her acceptance of her skills, and she did not decline invitations.

Participants also described their own way of living with their difficulties and managing their lifestyle. P8 engaged with other people with myositis through an Australian networking and research organization for people with myositis. P8 used the group's social media page to hear the perspectives of others who had faced similar concerns and stated ‘I found it's the only time you can ask questions … unless you can remember when you see your specialist’ (P8). P8 also attended their social gatherings where he was further able to engage with people living with the same condition. P8 used his membership as an opportunity to learn about new myositis research studies, many of which he engaged in which increased his sense of purpose and community engagement.

Being adaptable about mealtimes

Each participant described their own adaptive strategies which they viewed made mealtimes easier and safer for them to manage. P2 described pulling the crusts off her sandwiches while P7's wife described giving P7 breakfast food for dinner to ensure he ate something: ‘I just say it's a Weet‐Bix night’. P1 described how the mealtime schedule at his house was adapted so he never ate alone in case of a choking event. Participants also described being adaptable and experimental with their food and drink choices to reduce the choking risk. P3 described finding suitable alternative drink options and she often enjoyed banana milk shakes instead of coffee. Without these changes, P3 would not have been able to engage in outings. P1 and P9 also made adaptations when ordering food and would ask for food to be cooked until it was soft. P9 stated ‘when I go [out] … I say to the people I want my vegetables well done. And if they don't come well done, I send them back’.

Sticking to the status quo and resisting change

Participants with acquired dysphagia described how they tried to continue as they were before their dysphagia diagnosis to maintain their lifestyle. Maintaining a sense of normality and quality of life was particularly important for P2 who did not believe she needed to see a speech and language therapist and said, ‘our food always looks the same, if it's meat and 3 veggies, its meat and 3 veggies. If it's casserole, its casserole’. P5 similarly told researchers that she was able to eat a wide range of foods, ‘I can eat steak, I eat chips, I eat pork crackle … sometimes I like to eat like an adult’. Both participants demonstrated a desire to maintain normality by eating food that did not meet their texture‐modification needs. This may positively impact on quality of life as they can continue to engage in mealtimes as they always have, but resisting the changes in swallowing may also reduce quality of life if it impacts negatively on their health.

The perceptions of others and social exclusion

Participants explained how the perceptions of others could impact their quality of life through social inclusion or exclusion, depending on whether their needs were considered. P1 described how a lack of knowledge by other people when eating out negatively impacted on his attempts to improve his mealtime experience. P1 stated that wait staff often did not act in an accommodating manner when he asked for a meal to be modified due to a lack of understanding: ‘wait staff put it down to I'm being an arrogant person … who's trying to get away with as many changes as they can’. P4 also described being excluded when people chose a restaurant or café without considering if the food was appropriate for her needs. P4 said her colleagues ‘insisted on going to a café that only had really hard bread’ which resulted in her having a choking episode. In comparison, P4 had other positive experiences where her colleagues considered her swallowing needs, ‘one of the groups I am involved with, they have been terrific. They say here you go [participant] you can eat this, I make it especially’.

Narrative analysis: Lived experiences of the content themes

The stories narrated by participants reflected that each participant perceived and approached their diagnosis and progression of swallowing difficulties differently. Their lived experiences shaped their views on the impacts of dysphagia on quality of life as well as the barriers and facilitators that influenced their mealtimes. Their stories reflected much diversity in the approach or strategies used to adapt to and change their own mealtime circumstances. For example, P5's narrated rebuilding her lifestyle after the losses to mealtime enjoyment faced after her cancer and dysphagia diagnoses; whereas P4, who had cerebral palsy, narrated her having experienced early acceptance of having dysphagia, but also frustration at ongoing limitations ‘after 42 years I'm kind of over it!’

Participants also described finding ways to fight for themselves and others to improve their mealtime experiences. Self‐determination drove each of the participants to push for their rights to be met by others (e.g., catering services). P3, who had lived with and managed dysphagia since childhood, described lobbying for better food choices at a disability conference where the food served was inappropriate for people with swallowing difficulties. She said, ‘it was [disability organization]! … I did give feedback!’ (P3). Conference attendees were served tough meat and half cooked vegetables for dinner, so P3 put in a complaint for the quality of the food. She said, ‘sometimes when I expect better choice there is none like at the [disability organization] dinner in [city] years ago’. P3 reported the organization should have provided more appropriate foods to match people's needs, particularly as the conference aimed to support people with disability. P5 also advocated for more positive mealtime experiences and supported others in implementing positive change by writing a dysphagia‐friendly cookbook, outlining ways to create and present texture‐modified foods, to support others in their dysphagia and mealtimes journey. She narrated doing so as she could not find the resources needed to successfully self‐manage her swallowing difficulties, in particular how to transition back to oral feeds from enteral tube feeding. P5 used her experience in the food and wine industry to write the cookbook and an online training course to help other people. From this, P5 has worked with health professionals to promote her programme to others.

For all participants, regardless of cause or severity of dysphagia, they all described learning to live their difficulties. Through their mealtime experiences, participants gained their own understanding of how dysphagia impacted on their life, and they also identified barriers or facilitators that shaped their experiences. P2 learned to conceal her difficulties to maintain social etiquette, particularly in public. However, with time, she accepted the change stating, ‘it wouldn't worry me … it doesn't anymore’. For others, their experience was related to learning how they could be supported at mealtimes. P6's mother described lifelong learning to meet P6's preferences and needs as her skills changed through childhood and into adulthood. P6's support worker also described the difference in P6's swallowing recently stating, ‘it's more intense in the last couple of months than what it usually is’ highlighting the variable nature of P6's swallowing skills and the need for flexible support. This highlighted that although participants had lived with dysphagia for a number of years, they were still open to learning to meet their changing needs and to improve their mealtime experience.

DISCUSSION

This research provided an in‐depth understanding of the impacts of dysphagia and its management on quality of life for people with lifelong and ongoing acquired dysphagia, in particular the impacts on their choice and control, social engagement, experiences with food, physical health and the ways that they move to self‐manage and implement dysphagia and mealtime management strategies. This helped to close the gap identified in Smith et al. (2022b) in understanding the lived experiences of people with lifelong or ongoing dysphagia; providing insights from people with dysphagia and their supporters. In doing so, it has also highlighted barriers and facilitators that may influence the person's mealtime related quality of life and the importance of self‐advocacy. The examination of mealtime documents and the mealtime observations provided extra depth into these findings by providing the context for the issues raised in the interviews.

Past research identified in the scoping review by Smith et al. (2022a) demonstrated that quality of life, a qualitative phenomenon, is often assessed using quantitative assessments including the Swallowing Quality of Life Questionnaire (McHorney et al., 2002). By using in‐depth interviews and qualitative analysis, this research provided a greater understanding of the impacts of dysphagia on the quality of life of people with health conditions associated with dysphagia. Triangulating these views with data from observational measures of dysphagia (Sheppard et al., 2014) as used in this study was useful in terms of providing context to the views and lived experiences examined. While not intended as diagnostic measures of the person's dysphagia, the methods used in this study enabled reporting of severity of dysphagia based on the observational, online assessment (Malandraki et al., 2021; Ward & Burns, 2014). These insights demonstrate the importance of health professionals discussing a person's mealtime experiences with them and analysing this information for in‐depth personalized insights to inform their ongoing dysphagia management and improve their quality of life. These discussions were particularly important as past research has shown that texture‐modified foods (a commonly implemented intervention) are often unappealing and reduce the person's food intake, impacting on their quality of life and the mealtime experience (Seshadri et al., 2018; Shune & Linville, 2019). The findings also reflect that a person's dysphagia‐related quality of life is, as in the HRQOL model, influenced by the person's individual factors including their swallowing skills and their environment (Ferrans et al., 2005). This serves to emphasize the importance of not only considering the health‐related impacts of dysphagia, but also the personal and environmental factors, including the stories of the person learning to live with their swallowing difficulties and self‐advocacy, as influencing quality of life. This expands upon previous research by Moloney and Walshe (2018) who reported that people with dysphagia not only faced physical changes but changes to their relationships with others and their social engagement. The study by Moloney and Walshe (2018) only included people with dysphagia after a stroke, thus this research extends upon these findings to include people with dysphagia associated with other acquired and lifelong health conditions.

This study included participants with lifelong dysphagia related to developmental disabilities. This population faced the longevity and substantial experience of both the cost impact and the management needed to maintain both health and safety and quality of life as described in previous research by Balandin et al. (2009). They may have substantial need for self‐advocacy if their needs are not met in various mealtime situations, through lack of knowledge or experience of others in relation to dysphagia (Warren & Manderson, 2013). This is important as prior research including the views and perspectives of those with lifelong dysphagia is limited (Smith et al., 2022a). This research built upon the findings presented by Balandin et al. (2009) by presenting facilitators that may assist in improving quality of life for people with dysphagia of a variety of aetiologies.

This research provides further evidence for the need for health professionals to include social participation and well‐being as part of dysphagia intervention as recommended by Howells et al. (2019b). It is essential that health professionals involved in dysphagia management are aware of the impacts of dysphagia on quality of life and management factors forming barriers and facilitators to a person's dysphagia or mealtime‐related quality of life. They also need to be aware of their positioning as health professionals in perpetuating or ameliorating negative impacts on the person's quality of life brought about by assuming that dysphagia interventions would improve quality of life by improving health. Clinicians should engage in open communication with the client, eliciting stories that look beyond physical health to determine how exactly dysphagia is influencing the person's lifestyle, to allow for interventions to be implemented that maintain and improve quality of life and psychosocial well‐being (Howells et al., 2019b). By considering the impacts on quality of life outlined in this study, clinicians’ recommendations may be more acceptable to the person with dysphagia with flow‐on positive impacts on their physical health. The inclusion of facilitators to quality of life in this study also provides strategies that health professionals can encourage people with dysphagia to consider (Howells et al., 2019b). By identifying barriers, this study highlights factors that need to be addressed , often through education, to improve a person's quality of life (e.g., if a person is resisting change).

Limitations and directions for future research

This was a small study and findings should be interpreted with caution and cannot be generalized to all people with lifelong or chronic dysphagia. Although small, the in‐depth nature of the interviews and diversity of participants provided good insights into the lived experience for these participants which may be similar for people in similar situations. The findings could be used in awareness raising campaigns and inform clinical practice in terms of stimulating clinicians to ask their clients more about the quality‐of‐life impacts from their perspective, and about what improves their mealtime experiences. The requirement for participants to have access to a computer, internet, and ability to use Zoom may have meant that participants with more severe dysphagia or those without support to take part were not able to and their insights could further develop the content themes and experiences narrated in this study.

Overall, despite the relatively small sample size, the content themes and narratives identified came through strongly across the interviews. Further research should look to gain an in‐depth understanding of the impacts of dysphagia on quality of life from a larger number of people with dysphagia, from a variety of cultural backgrounds, with a range of associated communication disabilities, and a range of other lifelong or acquired health conditions than those included in this study. Given the successful use of observational online measures in this study, future qualitative research on dysphagia quality of life impacts should include observational measures of the person's dysphagia severity at the time of the interviews to give context to the findings. Research investigating the views of health professionals who work with people with dysphagia would provide important triangulating insights into the themes and concepts outlined above and also uncover further strategies for improving a person's mealtime‐related quality of life. Furthermore, research examining how clinicians’ exploration of the clients’ own lived experiences of the ‘costs’ of dysphagia influences dysphagia assessment and intervention goals is also indicated.

CONCLUSIONS

Dysphagia has several impacts on quality of life, relating both to the ‘costs’ of dysphagia and to its management. The personal stories collected also highlight the importance of self‐advocacy and the ability to learn to live with dysphagia to encourage positive mealtime experiences. People with dysphagia, whether of lifelong or acquired and ongoing origin, have lived experiences of the condition which must be explored and taken into account in any dysphagia management strategies suggested by health professionals and should continue to be included in assessment reports and mealtime plans. Dysphagia or mealtime‐management‐related impacts on quality of life shape the way that people with dysphagia engage in mealtimes. The need for people with dysphagia to strongly self‐advocate for receiving appropriate food at events hints at the fact that inclusive menus and foods should be considered at any event designed to include people with disability. This research should be used to shape policy and practice regarding (1) dysphagia assessment and management, including the design of interventions that not only improve health but also quality of life, and reduce any negative impact of interventions on quality of life; and (2) the provision of foods which the person views as being safe and enjoyable and which are of an appropriate texture for people with dysphagia. Policies and practices that support a person‐centred and inclusive approach to interventions and recognizing the many impacts outlined by participants in this study could benefit those with similar experiences to the participants in this study. Health professionals working with people with dysphagia should take the barriers and facilitators found in this study into consideration when providing assistance for swallowing difficulties. This will ensure health professionals are able to identify and reduce the impacts of the barriers to quality of life while enhancing the impacts of facilitators for their clients with dysphagia.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Open access publishing facilitated by University of Technology Sydney, as part of the Wiley ‐ University of Technology Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

APPENDIX A.

STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE FOR MEALTIME OBSERVATIONS AT HOME

Note: In the context of COVID‐19, these procedures are easily adapted to an online format by using a smart phone or iPad in the person's home, which is operated by the participant or their support worker or family member. Dysphagia assessments are currently conducted using telepractice safely in Australia, using a camera set‐up and a videoconferencing call.

The procedures outlined below are possible in person or online, and are similar regardless of format. This is because the same safety procedures apply whether the researcher is present or online.

Before the observation, the researcher will request a copy of the procedure on choking. On the day of the observation, the researcher will introduce themselves to the Site Manager and to the Participant, and remind them of the purpose of the visit.

It be organized in the participant's own home, in a location that is convenient for them. A camera will be set up (e.g., by the participant or a support person) for appropriate recording of the participant's mealtime and interview.

The participant will eat their usual meal and drinks under observation of the researcher, who will record observations in field notes and complete the Dysphagia Disorders Survey. Whether in‐person or online, the same procedures will be followed. In the observation, the researcher will instruct the participant and their support person to eat their usual foods and their usual drinks while being observed. The person will have supervision during the meal from their usual mealtime assistant (as it is a typical meal, including their typical foods and assistance provided). The assistant will remain present with the person in the event of an unusual choking incident or coughing that needs intervention (e.g., back blows). This would be rare but could happen just by chance.

If coughing occurs during the meal, the Participant and support person will be instructed that no further food will be provided until the Participant has recovered their usual breathing pattern. Coughing is protective and is a reflex to clear food away from the airway area in the throat (e.g., the larynx). If the coughing is not effective in clearing the food away (i.e., is persistent, weak, or ineffectual), or the Participant does not return to their usual breathing pattern, the support person present will be asked by the researcher to notify the site manager for their advice and to supervise first aid.

If the Participant exhibits signs of choking or any distress, or sign of allergic reaction, the mealtime observation will cease and the site's first‐aid procedures will be followed.

APPENDIX B.

TABLE B1.

Mealtime document extraction sheet

| Information to extract | Information collected |

|---|---|

| Document type (plan/report/other) | |

| What is the severity of dysphagia? | |

| What symptoms of dysphagia are reported? (e.g., coughing, food pooling in mouth) | |

| Oral diet: What textures are recommended/foods that the person can and cannot have? | |

| Position: Is there specific positioning for mealtimes (e.g., princess chair, upright in bed)? | |

| Equipment: Are assistive devices used at mealtimes, if so are all devices listed (e.g., glasses, dentures, hearing aids)? | |

| Participation: Are there any comments on the person's involvement in the decision about the plan/compliance or otherwise? | |

| Participation: Is there any description of types of food the person likes/dislikes? | |

| Participation: Is there a description of how to make meals accessible to the person during the mealtime (e.g., in their reach and visual field)? | |

| Inclusion: What environment does the participant eat their meal in (e.g., at table with others)? | |

| Compensatory strategies: Are there strategies that can be used during mealtimes to reduce risk (e.g., alternating boluses, chin tuck, extra time for each mouthful of food)? | |

| Mealtime assistance: Is assistance required during the meal (e.g., assistance in putting food on utensil and bringing to mouth, cutting food)? | |

| Mealtime assistance: What verbal directions are used at mealtimes (e.g., directing person what to do)? | |

| Mealtime assistance: What is the response to choking if it occurs during mealtime? | |

| After meal care: Does the report mention oral care required after meal, if so what is it (e.g., make sure mouth is empty)? |

APPENDIX C.

INTERVIEW GUIDE (CONVERSATIONAL INTERVIEW) FOR PEOPLE WITH DYSPHAGIA AND THEIR SUPPORTERS

As this is a conversational‐style interview, not all questions may be asked of examples of probing questions are provided to show the scope of the interview.

Q1. Tell me about your usual mealtimes, for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, what do they involve for you?

Examples of possible probing questions, depending on the responses to initial question.

-

○

Do all meals meet the texture modified diet recommendations?

-

○

Who determines food selection?

-

○

Who prepares meals? Is assistance required for cutting or opening cans/bottles?

-

○

What support do you need to cook the food?

-

○

There can be a lot of preparation in making pureed meals, how long does it take to make the meals?

-

○

Do you enjoy eating these foods?

-

○

Does the food look good, taste good, smell good, or is it served at the right temperature in comparison to food that is not pureed?

-

○

Do you consider mealtimes as a social event or a chore?

-

○

Do you make meals in bulk and then store some for another day? If so, how do you store the food?

Q2. What support do you receive from health professionals in managing your dysphagia?

Examples of possible probing questions, depending on the responses to initial question.

-

○

How did they help, what did they do?

-

○

Do you have a written mealtime management plan?

-

○

Were you involved in writing your mealtime plan (e.g., did you include your favourite foods)?

-

○

If you ask for something to be changed, do they try and change it or do they continue to follow your normal routine?

Q3. Can you explain any impact of your swallowing difficulty on your quality of life, social life, or ability to take part in social events?

Examples of possible probing questions, depending on the responses to initial question.

-

○

What are social events involving food like for you?

-

○

Do you enjoy going to social gatherings that involve a meal?

-

○

Do you have to find out the types of food that will be served before you go to an event? Is this embarrassing?

-

○

Have you ever refused an invite to a social gathering because you did not want to eat around others?

-

○

How easy is for you to get food that meets your dietary requirements when out?

-

○

If you cannot eat the foods served when out with others, how does that make you feel?

-

○

Do you require any other assistance at mealtimes (e.g., adapted cutlery)? How do you feel about using these tools when eating with other people?

Q4. How is your pureed food usually presented on the plate? What do you think of the way the foods looks in terms of being appetizing?

Examples of possible probing questions, depending on the responses to initial question.

-

○

Are the foods appetizing to you? Do they look attractive?

-

○

Do they use food moulds or piping bags?

-

○

Were these methods successful? What made it successful or unsuccessful?

-

○

What could make these food design methods more successful?

Smith, R. , Bryant, L. & Hemsley, B. (2023) The true cost of dysphagia on quality of life: The views of adults with swallowing disability. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 58, 451–466. 10.1111/1460-6984.12804

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Due to the nature of this research, participants in this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

REFERENCES

- Ang, S.Y. , Lim, M.L. , Ng, X.P. , Lam, M. , Chan, M.M. , Lopez, V. , et al. (2019) Patients and home carers' experience and perceptions of different modalities of enteral feeding. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(17–18), 3149–3157. 10.1111/jocn.14863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balandin, S. , Hemsley, B. , Hanley, L. & Sheppard, J. (2009) Understanding mealtime changes for adults with cerebral palsy and the implications for support services. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 34(3), 197–206. 10.1080/13668250903074489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz, C. & Hammond, R. (2014) Dysphagia: education needs assessment for future health‐care foodservice employees. Nutrition & Food Science, 44(5), 407–413. 10.1108/NFS-03-2013-0035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. (2017) Constructivist grounded theory. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 299–300. 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cichero, J. , Lam, P. , Steele, C.M. , Hanson, B. , Chen, J. , Dantas, R.O. , et al. (2017) Development of international terminology and definitions for texture‐modified foods and thickened fluids used in dysphagia management: the IDDSI framework. Dysphagia, 32(2), 293–314. 10.1007/s00455-016-9758-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, M. (2007) Narrative analysis. In: Coyle, A. & Lyons, E. (Eds.) Analysing qualitative data in psychology. London, England: Sage Publications Ltd, pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Engh, M.C. & Speyer, R. (2022) Management of dysphagia in nursing homes: a national survey. Dysphagia, 37(2), 266–276. 10.1007/s00455-021-10275-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrans, C. , Zerwic, J. , Wilbur, J. & Larson, J. (2005) Conceptual model of health‐related quality of life. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 37(4), 336–342. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groher, M. & Crary, M. (2016) Dysphagia: clinical management in adults and children, 2nd edition. Elsevier Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G. , Bunce, A. & Johnson, L. (2006) How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. 10.1177/1525822/05279903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley, B. , Steel, J. , Sheppard, J.J. , Malandraki, G.A. , Bryant, L. & Balandin, S. (2019) Dying for a meal: an integrative review of characteristics of choking incidents and recommendations to prevent fatal and nonfatal choking across populations. American Journal of Speech‐Language Pathology, 28(3), 1283–1297. 10.1044/2018_ajslp-18-0150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells, S.R. , Cornwell, P.L. , Ward, E.C. & Kuipers, P. (2019a) Dysphagia care for adults in the community setting commands a different approach: perspectives of speech–language therapists. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 54(6), 971–981. 10.1111/1460-6984.12499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells, S.R. , Cornwell, P.L. , Ward, E.C. & Kuipers, P. (2019b) Understanding dysphagia care in the community setting. Dysphagia, 34(5), 681–691. 10.1007/s00455-018-09971-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisiecka, D. , Kelly, H. & Jackson, J. (2021) How do people with Motor Neurone Disease experience dysphagia? A qualitative investigation of personal experiences. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(4), 479–488. 10.1080/09638288.2019.1630487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malandraki, G.A. , Hahn Arkenberg, R. , Mitchell, S. & Bauer Malandraki, J. (2021) Telehealth for dysphagia across the life span: using contemporary evidence and expertise to guide clinical practice during and after COVID‐19. American Journal of Speech–Language Pathology, 30(2), 532–550. 10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney, C.A. , Robbins, J. , Lomax, K. , Rosenbek, J.C. , Chignell, K. , Kramer, A.E. , et al. (2002) The SWAL‐QOL and SWAL‐CARE outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: III. Documentation of reliability and validity. Dysphagia, 17(2), 97–114. 10.1007/s00455-001-0109-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills, J. , Bonner, A. & Francis, K. (2006) The development of constructivist grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Moloney, J. & Walshe, M. (2018) “I had no idea what a complicated business eating is…”: a qualitative study of the impact of dysphagia during stroke recovery. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(13), 1524–1531. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1300948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D. , Krueger, R. & King, J. (1998) The focus group kit: Volume 1–6. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, B.C. , Harris, I.B. , Beckman, T.J. , Reed, D.A. & Cook, D.A. (2014) Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, T.H. , Brumfield, K.A. , Hoskin, T.L. , Kasperbauer, J.L. & Basford, J.R. (2008) Dysphagia in inclusion body myositis: clinical features, management, and clinical outcome. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 87(11), 883–889. 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31818a50e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. (2014) Qualitative research and evaluation methods, 4th edition, Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. (2018) NVivo (Version 12) [Windows]. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo‐qualitative‐data‐analysis‐software/support‐services/nvivo‐downloads/older‐versions

- Riessman, C.K. (2007) Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri, S. , Sellers, C.R. & Kearney, M.H. (2018) Balancing eating with breathing: community‐dwelling older adults’ experiences of dysphagia and texture‐modified diets. The Gerontologist, 58(4), 749–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, J. , Hochman, R. & Baer, C. (2014) The Dysphagia Disorder Survey: validation of an assessment for swallowing and feeding function in developmental disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(5), 929–942. 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shune, S.E. & Linville, D. (2019) Understanding the dining experience of individuals with dysphagia living in care facilities: a grounded theory analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 92, 144–153. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. , Hemsley, B. & Bryant, L. (2019) Systematic review of dysphagia and quality of life, participation, and inclusion experiences or outcomes for adults and children with dysphagia. PROSPERO 2019. CRD42019140246. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42019140246

- Smith, R. , Bryant, L. & Hemsley, B. (2022a) Dysphagia and quality of life, participation, and inclusion experiences and outcomes for adults and children with dysphagia: a scoping review. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 7(1), 181–196. 10.1044/2021_PERSP-21-00162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. , Bryant, L. , Reddacliff, C. & Hemsley, B. (2022b) A review of the impact of food design on the mealtimes of people with swallowing disability who require texture‐modified food. International Journal of Food Design, 7(1), 7–28. 10.1386/ijfd_00034_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stavroulakis, T. , Baird, W.O. , Baxter, S.K. , Walsh, T. , Shaw, P.J. & McDermott, C.J. (2016) The impact of gastrostomy in motor neurone disease: challenges and benefits from a patient and carer perspective. British Medical Journal Supportive & Palliative Care, 6(1), 52–59. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele, C. , Alsanei, W. , Ayanikalath, S. , Barbon, C. , Chen, J. , Cichero, J. , et al. (2015) The influence of food texture and liquid consistency modification on swallowing physiology and function: a systematic review. Dysphagia, 30(1), 2–26. 10.1007/s00455-014-9578-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, E. & Burns, C. (2014) Dysphagia management via telerehabilitation: a review of the current evidence. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Research, 3(5), 1088–1094. 10.6051/j.issn.2224-3992.2014.03.408-17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren, N. & Manderson, L. (Eds.) (2013) Reframing disability and quality of life: a global perspective. Springer Science+Business Media. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978‐94‐007‐3018‐2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . (1998) The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL). World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.S. , Miles, A. & Braakhuis, A. (2020) Nutritional intake and meal composition of patients consuming texture modified diets and thickened fluids: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Healthcare, 8(4), 579. 10.3390/healthcare8040579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoom Video Communications Inc. (2011) Zoom [Windows]. https://zoom.us/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants in this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.