Abstract

Aims

Muscle biopsy techniques range from needle muscle biopsy (NMB) and conchotome biopsy to open surgical biopsy. It is unknown whether specific biopsy techniques offer superior diagnostic yield or differ in procedural complication rates. Therefore, we aimed to compare the diagnostic utility of NMB, conchotome and open muscle biopsies in the assessment of neuromuscular disorders.

Methods

A systematic literature review of the EMBASE and Medline (Ovid) databases was performed to identify original, full‐length research articles that described the muscle biopsy technique used to diagnose neuromuscular disease in both adult and paediatric patient populations. Studies of any design, excluding case reports, were eligible for inclusion. Data pertaining to biopsy technique, biopsy yield and procedural complications were extracted.

Results

Sixty‐four studies reporting the yield of a specific muscle biopsy technique and, or procedural complications were identified. Open surgical biopsies provided a larger tissue sample than any type of percutaneous muscle biopsy. Where anaesthetic details were reported, general anaesthesia was required in 60% of studies that reported open surgical biopsies. Percutaneous biopsies were most commonly performed under local anaesthesia and despite the smaller tissue yield, moderate‐ to large‐gauge needle and conchotome muscle biopsies had an equivalent diagnostic utility to that of open surgical muscle biopsy. All types of muscle biopsy procedures were well tolerated with few adverse events and no scarring complications were reported with percutaneous sampling.

Conclusions

When a histological diagnosis of myopathy is required, moderate‐ to large‐gauge NMB and the conchotome technique appear to have an equivalent diagnostic yield to that of an open surgical biopsy.

Keywords: diagnosis, muscle biopsy, myopathy, neuromuscular disease

A variety of muscle biopsy techniques have been reported in the literature. In this systematic review, muscle biopsies performed with a moderate‐ to large‐gauge needle or conchotome forceps were found to have equivalent clinical utility to open surgical biopsies.

Key points.

Muscle biopsy remains an important diagnostic test for patients with muscle weakness of unknown aetiology.

Various muscle biopsy techniques exist, including needle muscle biopsy, conchotome muscle biopsy and open surgical biopsy. The diagnostic equivalence of each biopsy technique has not previously been compared.

The moderate‐ to large‐gauge needle and conchotome biopsies have an equivalent diagnostic yield to an open surgical biopsy, with the advantage of requiring only local anaesthesia, with or without light sedation.

Muscle biopsies, irrespective of the technique, are safe and well tolerated with few adverse events reported.

INTRODUCTION

A muscle biopsy has long been considered the cornerstone of the diagnosis of myopathy [1]. Despite advances in serological and genetic evaluation of myopathies, histopathological evaluation of skeletal muscle remains an important diagnostic test in patients with quantifiable weakness of uncertain aetiology [2]. Evaluation of muscle tissue through biopsy may permit a specific diagnosis, support or exclude a diagnosis made on clinical grounds and provide invaluable material for functional studies, molecular analyses or biobanking. Muscle biopsies are generally targeted to muscles that are suspected to be affected by disease; either because of clinical weakness, evidence of active myopathy on electromyography (EMG) studies or imaging changes detected by ultrasound (US) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [2]. Deltoid, biceps and quadriceps muscles are commonly biopsied, as established norms for fibre type percentages and muscle fibre size of these muscle groups exist [2]. The volume of muscle tissue obtained in a given biopsy sample is important because a yield of at least 200–250 muscle fibres in a well‐oriented transverse section is generally required to confidently diagnose or exclude a myopathic process on histological grounds [3]. Sample volume is also an important consideration for nonmorphological diagnostic tests, such as mitochondrial studies.

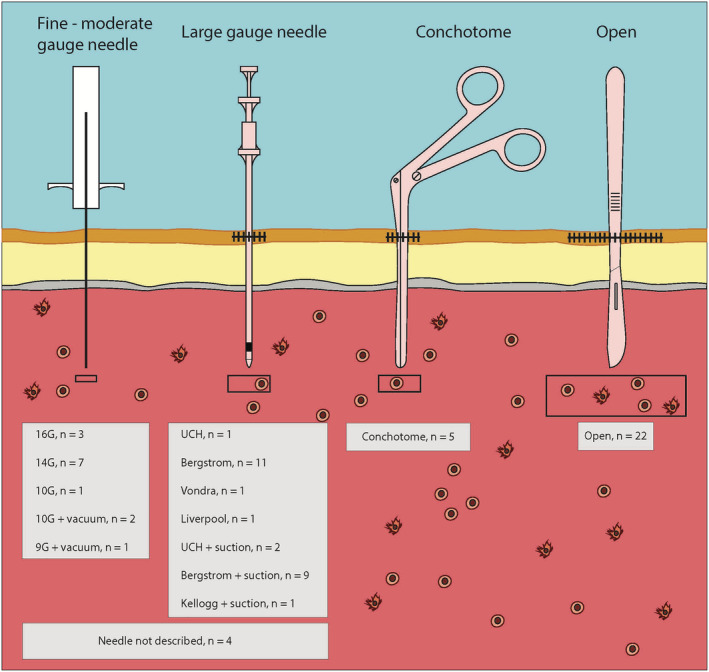

Various muscle biopsy techniques exist (Figure 1). Based upon institutional experience, preference is given to either open surgical biopsy, needle muscle biopsy (NMB) or conchotome biopsy. Open muscle biopsies require a surgical team, with or without general anaesthesia, and an incision through the skin, subcutaneous tissue and muscle fascia, to obtain a sample that is characteristically 1 cm × 0.5 cm in size [2]. Needle muscle biopsies are performed with needles of various gauges, commonly under local anaesthesia or light sedation, and can be performed at the bedside. A specialised muscle biopsy needle, the Bergström needle was developed in the 1960s, when percutaneous NMB was reintroduced to routine clinical practice [4]. This needle, constructed of two parallel cylinders of up to 5 mm in diameter, can yield sufficient muscle tissue without the need for an open incision. While NMB has the advantage of not requiring general anaesthesia or a large incision, the tissue yield of an NMB is smaller [5]. Insufficient yield of tissue from an NMB has been considered a limitation of this procedure, leading to the introduction of suction NMB to increase the volume of tissue obtained with each procedure [3]. The Well–Blakesley conchotome forceps (alligator forceps that open with a scissor grip [3]) are an alternative to the Bergström needle for percutaneous muscle biopsy, again allowing for bedside muscle biopsy under local anaesthesia. A conchotome biopsy is thought to yield a similar volume of tissue as an NMB, but the conchotome forceps may allow for more precise placement of the forceps compared with percutaneous needle puncture, which may be advantageous in diagnosing focal rather than diffuse myopathic changes [3].

FIGURE 1.

Types of muscle biopsy. Note: n = number of studies of each muscle biopsy technique included in this review.

The diagnostic equivalence of various muscle biopsy techniques has not been systematically compared. Given the potential benefits of an NMB or conchotome biopsy, it is of clinical importance to establish whether an NMB has equivalent diagnostic utility to an open surgical biopsy. Therefore, we performed a systematic literature review of NMB, conchotome and open muscle biopsies, both in relation to the volume of muscle tissue obtained and the diagnostic yield of each procedure.

METHODS

This study was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) checklist [6]. A systematic literature search of the EMBASE and Medline (Ovid) databases from January 1970 to July 2021 was performed to identify original research articles that described the muscle biopsy technique used to diagnose neuromuscular disease in either adult or paediatric patients. Keywords used in the search were (muscle, muscles or muscular), (biopsy, biopsies, microbiops*), (percutaneous or needle or needles), conchotome (diagnosis or diagnostic or pathology or sensitivity or specificity or classification or safety or complication).

After de‐duplication, all retrieved abstracts were reviewed by a single author (JD) to identify relevant studies for full‐text review. If there was any uncertainty about study eligibility, it was included for full‐text review. Two authors (LR and JD) independently reviewed the full text of all eligible abstracts. Each author independently assessed the eligibility of all full‐text articles and uncertainty was resolved by consensus. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were original research articles that provided information about muscle biopsy technique and described the muscle biopsy sample size, diagnostic yield or complications of the procedure. Human studies of any neuromuscular condition published in English were eligible for inclusion. Studies were excluded if combined nerve and muscle biopsies were performed. Studies including both adult and paediatric populations were eligible. Case reports and scientific meeting abstracts were excluded from the review. The same two authors independently extracted information regarding the study design and patient population, muscle biopsy technique and biopsy yield and procedure complications according to a prespecified template (see Data S1). An open surgical muscle biopsy was defined as a biopsy requiring an incision through the skin and subcutaneous tissue and excision of muscle tissue using a scalpel. A fine‐needle biopsy (FNB) was defined as a percutaneous diagnostic procedure performed using a 14‐ to 16‐gauge needle. A moderate‐gauge NMB was defined by the use of a 9‐ to 10‐gauge needle, and a large‐gauge NMB was defined by the use of <9‐gauge needle to perform a percutaneous procedure. Descriptive statistics were used to present the study results. Owing to the heterogeneity of study methodology and outcome, it was not possible to perform a meta‐analysis of the data extracted. Abstracts were screened using the citation management software Covidence (www.covidence.org), and full‐text articles were managed using the bibliographic manager EndNote X9.3.3 (Thomas Reuters). Ethical approval was not required for this study.

RESULTS

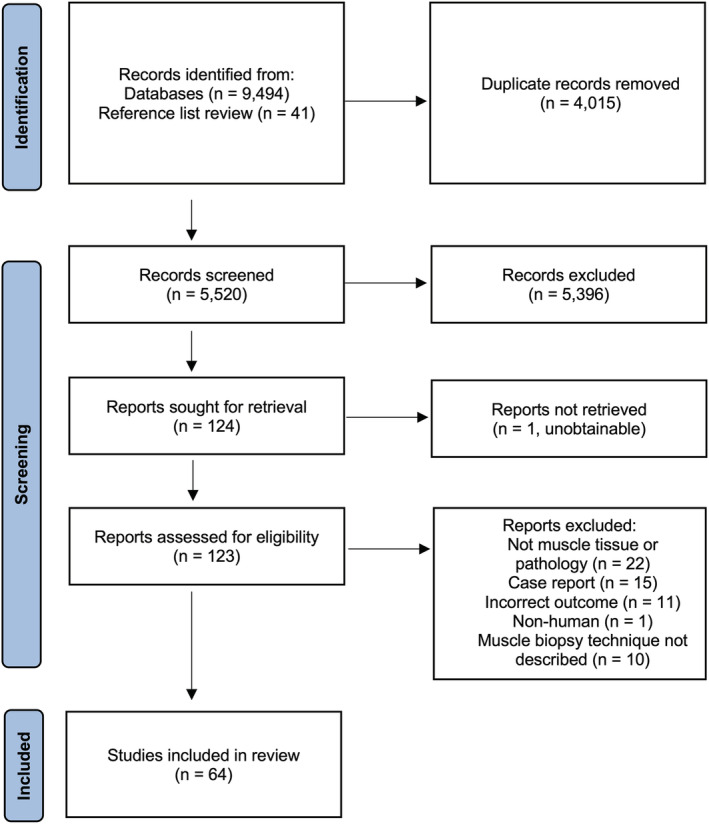

The search identified 9536 citations which after de‐duplication left 5479 references for review. The full text of 124 studies was reviewed. A further 41 references were identified through manual searching of study reference lists. A total of 64 studies met the prespecified criteria for inclusion in the final review (Figure 2). The study characteristics of all studies included in the final review are detailed in Table 1 and Figure 1.

FIGURE 2.

PRISMA flowchart of study selection process.

TABLE 1.

Study characteristics.

|

Author Year Country |

Study type | Diagnosis/suspected diagnosis | Inclusion criteria | Population | Mean age (years) (range) | Number of patients | Number of biopsies | Biopsy type | Biopsy setting | Incision size (cm) | Anaesthesia used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open surgical biopsy (OSB) | |||||||||||

|

Aburahma [7] 2019 USA |

Retrospective case series | Myopathy | Repeat muscle biopsy | A | 16 (18–80) | 78 | 143 | OSB | Operating theatre | NR | General anaesthesia |

|

Buchthal [8] 1982 Denmark |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsies | A/P | NR | 188 | 348 | OSB | NR | NR | NR |

|

Constantinides [9] 2018 Greece |

Retrospective case series | Documented EMG and biopsy data | Suspected myopathy | NR | NR | 123 | 123 | OSB | NR | NR | Local anaesthesia |

|

Gibertoni [10] 1987 Italy |

Case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive patients | NR | NR | 53 | NR | OSB | NR | NR | NR |

|

Gibreel [11] 2014 USA |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive surgical muscle biopsies | P | 7 (9 days to 18 years) | 169 | 169 | OSB | Operating theatre | NR | General anaesthesia |

|

Goutman [12] 2013 USA |

Retrospective case series | Myopathy | Consecutive patients undergoing repeat muscle biopsy | A/P | Median: 41.6 (0.48–79.4) | 66 | 149 | OSB | NR | NR | NR |

|

Jamshidi [13] 2008 USA |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive biopsies | P | 5.3 (8 days to 21 years) | 127 | 127 | OSB | NR | NR | NR |

|

Kokotis [14] 2016 Greece |

Retrospective case series | Elevated creatine kinase for investigation | Asymptomatic elevated serum creatine kinase | A | 18–76 | 19 | 10 | OSB | NR | NR | Local anaesthesia |

|

Laguno [15] 2002 Spain |

Retrospective case–control study | Muscle disorders of elderly |

Consecutive muscle biopsies from individuals >65 years Control group: biopsies in patients <65 years |

A |

Cases: 72.1 ± 5 years Controls: 40 ± 16 years |

239 | 478 | OSB | Outpatient clinic | NR | Local anaesthesia |

|

Lai [16] 2010 USA |

Retrospective case series | Myopathy | Consecutive muscle biopsies; excluding autopsy studies or combined muscle and nerve biopsy | A/P | 47 ± 22 (2 weeks to 84 years) | 258 | 258 | OSB | NR | NR | NR |

|

Reynolds [17] 1999 USA |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsies | P | NR | 153 | 153 | OSB | Operative theatre | 2–3 cm | General anaesthesia |

|

Shaibani [18] 2015 USA |

Retrospective case series | Myopathy | Consecutive muscle biopsy | A | 55.32 ± 15.55 | 698 | 720 | OSB | NR | NR | NR |

|

Shapiro [19] 2016 USA |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsy | P | <1 month to 19 years | 877 | 877 | OSB | Operative theatre | 1.2–1.8 cm | General anaesthesia |

|

Sujka [20] 2018 USA |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsy | P | Median: 5 (2–10) | 90 | 90 | OSB | NR | NR | NR |

|

Tenny [21] 2018 USA |

Retrospective case series | Myopathy | Consecutive muscle biopsy | A |

57.4 ± 16.9 Range: 21–86 |

106 | 106 | OSB | Operative theatre | NR | NR |

|

Thavorntanaburt [22] 2018 Thailand |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsy | P | 7.1 ± 4.2 | 92 | 94 | OSB | Operating theatre | 2 cm | General anaesthesia |

|

Van de Vlekkert [23] 2015 The Netherlands |

Prospective cohort study | Idiopathic inflammatory myositis | Suspected subacute inflammatory myositis | A | 50 ± 14 | 48 | 47 | OSB | NR; MRI triage of biopsy site | NR | Local anaesthesia |

|

Yang [24] 2019 USA |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsy | P | 7.7 | 220 | 220 | OSB | Operating theatre | NR | General anaesthesia |

| Fine‐needle biopsies | |||||||||||

|

Agten [25] 2018 Belgium |

Prospective pilot study | Chronic low back pain | Nonspecific chronic low back pain | A | 45.60 ± 8.81 | 15 | 30 | 16G NMB | Ultrasound landmarking of biopsy site | Needle puncture | Local anaesthesia |

|

Tobina [26] 2009 Japan |

Prospective case series | Feasibility study | Research volunteers | A |

Young males: 23.8 ± 2.3 Older males: 52.9 ± 7.7 Older females: 61.1 ± 8.4 |

40 | 40 | 16G NMB | NR | Needle puncture | Local anaesthesia |

|

Campellone [27] 1997 USA |

Retrospective case series | Idiopathic inflammatory myositis | All patients with suspected IIM | A | NR | 55 | 66 | 14G NMB | Hospital ward, EMG laboratory | Needle puncture | Local anaesthesia |

|

Cote [28] 1992 USA |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsies | A/P | NR | 105 | NR | 14G NMB | NR | Needle puncture | Local anaesthesia |

|

Lindequist [29] 1990 Denmark |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsies | A/P |

Males: 37.7 Females: 39.7 |

24 | 28 | 14G NMB | Ultrasound targeted biopsy | ‘Small’ | Local anaesthesia |

|

Magistris [30] 1998 Switzerland |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsies | A/P | NR | 220 (211 adults, 9 children) | 220 | 14G NMB | NR | 0.1–0.2 cm | Local anaesthesia; Sedation for 3 children |

|

Paoli [31] 2010 Italy |

Prospective pilot study | Feasibility study | Healthy volunteers | A | NR | 18 | 18 | 14G NMB | NR | Needle puncture | Local anaesthesia |

| Moderate‐gauge needle biopsies | |||||||||||

|

Barthelemy [32] 2020 USA |

Retrospective case series | Duchenne muscular dystrophy or Becker muscular dystrophy | Healthy individuals and individuals with Duchenne muscular dystrophy or Becker muscular dystrophy | A/P | 12.9 (2–66) | 94 | 471 | 10G NMB with vacuum | Research setting, clinic, hospital ward, OT; Ultrasound guided | 0.3 cm | Local anaesthesia Sedation with IV fentanyl and propofol (children only) |

|

Bylund [33] 1981 Sweden |

Retrospective case series | Compartment syndrome | NR | NR | NR | 12 | 36–48 | 10G NMB | NR | 0.3–0.4 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Gallo [34] 2018 Canada |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive percutaneous muscle biopsies | A | 55 (17–88) | 92 | 102 | 10G NMB with vacuum | NR | 1 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Lassche [35] 2018 The Netherlands |

Case series | FSHD | Genetically confirmed FSHD and enrolled in separate clinical study | NR | NR | 13 | 12 | 9G NMB with vacuum | MRI guided; MRI table | 0.4 cm | Local anaesthesia |

| Large‐gauge needle biopsies | |||||||||||

|

Cotter [36] 2013 USA |

Prospective case series | Feasibility study | Participants enrolled in exercise study | A | 21.4 ± 2.9 | 45 | 84 | 6G UCH NMB with suction | Outpatient clinic | 0.5–0.6 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Derry [37] 2009 United Kingdom |

Retrospective case series | Myopathy and neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsies | A/P | Median age: 51 (1–86) | 870 | 900 | 6 mm Bergström NMB | Bedside | 1 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Di Liberti [38] 1983 USA |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders or Reye syndrome | Consecutive muscle biopsies | P | 1 week to 15 years | 77 | 86 | 3 to 5 mm Bergström NMB | Outpatient clinic, ward | 0.5–0.8 cm | Local anaesthesia Sedation if age <8 years |

|

Edwards [39] 1973 United Kingdom |

Retrospective case series | Myopathy | Patients with muscular symptoms | A/P | 42.4 (10–68) | 31 | 32 | 4.5 mm Bergström NMB | Outpatient clinic, ward | 0.4–0.5 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Evans [40] 1982 USA |

Prospective pilot study | Volunteers from clinical study | NR | A | NR | 30 | 60 | 4–5 mm Bergström NMB with suction | NR | NR | NR |

|

Hennessey [41] 1997 USA |

Case series | NR | Volunteers from human growth hormone in frail elderly study | A | NR | 46 | 83 | 4–6 mm Bergström NMB with suction | NR | 0.6–0.9 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Highstead [42] 2005 USA |

Retrospective case series | Healthy individuals | Healthy volunteers | A | 18–76 years | 161 | 1301 | 5 mm Bergström NMB with suction | Research laboratory | 2 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Iachettini [43] 2015 Italy |

Prospective case–control | Myotonic dystrophy type I | Known patients and healthy controls | A | Patients: 29.8 (21–42) |

5 patients 5 controls |

10 | 5 mm UCH NMB with suction | NR | 1 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Kirby [44] 1982 Canada |

Prospective cohort study | Healthy athletes & clinically suspected muscle disease | Consecutive biopsies | A/P | 6–79 years | 60 | 444 | 4–5 mm Bergström NMB; various manoeuvres to fill needle window performed | NR | 0.5–0.7 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Leong [45] 1993 Singapore |

Case series | Myopathy | Consecutive muscle biopsies | A | 44 (range 20–69) | 24 | 24 | Bergström NMB | NR | NR | Local anaesthesia |

|

Maunder‐Sewry [46] 1981 United Kingdom |

Prospective case–control study | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Genetically obligate carriers, possible carriers, healthy volunteers | A/P | 2–61 | 65 | 75 | Bergström NMB | NR | NR | Local anaesthesia |

|

Melendez [47] 2007 USA |

Case series | No neuromuscular disease | Volunteers from other clinical studies | A | 50 ± 4.5 | 55 | 55 | 6 mm Bergström NMB with suction | NR | 3 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Mubarak [48] 1992 USA |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive percutaneous NMB | A/P |

1 week to 75 years 92% aged <18 years |

379 | 379 | 5 mm Bergström NMB with suction |

≥12 years: outpatient clinic <12 years: operating theatre |

‘Small stab wound’ |

≥12 years: local anaesthesia <12 years: general anaesthesia |

|

Neves [49] 2012 Brazil |

Retrospective case series | No neuromuscular disease |

Clinical study participants Healthy volunteers (n = 168) Individuals with chronic illness (n = 106) |

A |

Healthy subjects: 24 ± 8 years Subjects with chronic illness: 55 ± 8 years |

274 | 496 | 5 mm Bergström NMB with suction | NR | NR | Local anaesthesia |

|

Pamphlett [50] 1985 Australia |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive NMB | A/P | 9–75 | 70 | 75 | 5 mm Kellogg NMB with suction | NR | 0.5 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Raithatha [51] 2020 United Kingdom |

Retrospective case series | Myopathy | Consecutive patients unable to have a surgical biopsy | NR | NR | 10 | 11 | 5 mm Bergström NMB with suction | Ultrasound guided, MRI triage of the biopsy site | NR | Local anaesthesia |

|

Schwarz [52] 1980 United Kingdom |

Retrospective case series | Idiopathic inflammatory myositis | Consecutive muscle biopsies | A/P | 7–81 years | 30 | 30 | Bergström NMB | NR | 0.5 cm | NR |

|

Sengers [53] 1980 The Netherlands |

Retrospective case series | Muscle disease, cardiomyopathy, other | Consecutive muscle biopsies | P | 2 months to 17.5 years | 95 | 98 | Vondra NMB | Ward, outpatient clinic | 0.3 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Tarnopolsky [54] 2011 Canada |

Retrospective case series | Myopathy | Consecutive muscle biopsy | A/P | NR | NR | 13,914 | 5 mm Bergström NMB with suction | NR | 0.4–0.5 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Wang [55] 2019 USA |

Prospective case–control study | FSHD | Genetically confirmed FSHD (n = 33) and healthy controls (n = 9) | A | 54 (20–75) | 42 | 42 | UCH or Bergström NMB | NR | NR | NR |

| Needle size not described | |||||||||||

|

Billakota [56] 2016 USA |

Prospective pilot study | Myopathy | Consecutive patients referred for muscle biopsy | A | 55.7 ± 15.7 | 40 | NR | NMB; size not described | Ultrasound landmarking of biopsy site | NR | NR |

|

Curless [57] 1975 USA |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Children <5 years | P | 9 weeks to 3 years | 14 | 15 | NMB; size not described | NR | 0.5 mm | Sedation (chloral hydrate) |

|

Hafner [58] 2019 United Kingdom |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Definite or probable myopathy or neurogenic disorder or no neuromuscular disorder diagnosed | P | 6.8 | 171 | 171 | NMB; size not described | NR | NR | General anaesthesia |

| Conchotome muscle biopsies (CMBs) | |||||||||||

|

Dorph [59] 2001 Sweden |

Retrospective case series | Idiopathic inflammatory myositis | Consecutive muscle biopsies | A/P | Median: 56 (16–85) | 122 | 149 | CMB | Outpatient clinic, ICU | 0.5–1 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Henriksson [60] 1979 Sweden |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsies | A/P | <1–89 years | 959 | 959 | CMB | NR | 0.3–0.5 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Patel [61] 2011 United Kingdom |

Prospective cohort study (feasibility study) | Sarcopenia | Male participants in Hertfordshire Cohort Study ref | A | 72 (68–77) | 102 | 102 | CMB | Research laboratory (overnight stay) | 0.5–1 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Poulsen [62] 2005 Denmark |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsies | A/P | 10–81 | 157 | 160 | CMB | NR | 1–2 cm | Local anaesthesia and IM opiate analgesia |

| Comparative studies | |||||||||||

|

Dengler [63] 2014 Germany |

Prospective case–control study | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | Participants in adjunct clinical study | A | 63 ± 8 | 33 | 66 | 5 mm Bergström NMB vs OSB | Operating theatre |

0.5 cm NMB 3–4 cm OSB |

Local anaesthesia |

|

Dietrichson [64] 1987 United Kingdom |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsies | A/P | 32.4 (8 days to 70 years) | 292 | 436 | CMB (n = 222) vs Liverpool NMB (n = 330) | Ward, outpatient clinic, ICU, research laboratory |

CMB: 0.5 cm NMB: NR |

Local anaesthesia |

|

Fukuyama [65] 1981 Japan |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive muscle biopsies | A/P | 2 months to 35 years | 75 |

NMB: 3–4 biopsies/patient Open: 1 biopsy/patient |

OSB (n = 33) vs 14G NMB (n = 75) | NR |

NMB: 0.1 cm OSB: NR |

NMB: local anaesthesia Open: general anaesthesia |

|

Greig [66] 1985 USA |

Retrospective case–control | NR | Consecutive muscle biopsies | NR | NR | 37 | 84 | 5 mm Bergström NMB with suction vs 5 mm Bergström NMB without suction | NR | 0.6–1.3 cm | Local anaesthesia |

|

Hayot [67] 2005 Canada |

Prospective cohort study | COPD | COPD confirmed by RFT and healthy controls | A |

COPD: 69 ± 5 Controls: 27–29 |

17 COPD 4 controls | 42 | 16G NMB vs 6 mm Bergström NMB | Exercise physiology laboratory |

16G NMB: needle puncture Bergström NMB: 1 cm |

Local anaesthesia |

|

Heckmatt [68] 1984 United Kingdom |

Retrospective case series | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive NMB over a 5‐year period | A/P | Children: 1 day to 17 years | 700 | 700 | 5 mm Bergström NMB vs OSB (n = 24) | Ward, outpatient clinic | NR |

Local anaesthesia Sedation with chloral hydrate for children aged 12 months‐8 yrs. No sedation if age <12 months or >8 years |

|

O′Rourke [69] 1994 USA |

Retrospective case–control study | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive NMB and open muscle biopsy | A |

NMB: 45.9 Open: 52.5 Range: 19–84 |

121 | 121 | NMB (n = 30); size not described vs OSB (n = 91) | NR |

NMB:0.5 cm OSB: NR |

NMB: Local anaesthesia Some patients received IV midazolam sedation Open: NR |

|

O′Sullivan [70] 2006 Ireland |

Prospective case series (NMB) vs historical controls (OSB) | Neuromuscular disorders | Consecutive referrals for muscle biopsy | A | 56 (35–70) | 80 | 80 | 14G NMB (n = 40) vs OSB (n = 40) | Ultrasound guided, Radiology Department |

NMB: 0.3–0.4 cm OSB: NR |

Local anaesthesia |

Note: Grey shaded boxes = data not reported in the study.

Abbreviations: A, adult study population; CMB, conchotome muscle biopsy; EMG, electromyography; FSHD, facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy; ICU, intensive care unit; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NMB, needle muscle biopsy; NR, not reported; OSB, open surgical biopsy; P, paediatric study population; UCH, university college hospital; USA, United States of America.

Studies considered the role of muscle biopsy in the evaluation of suspected neuromuscular disorders (n = 26), myopathy not further specified (n = 13), muscular dystrophies (n = 5), idiopathic inflammatory myositis (n = 4), healthy volunteers (n = 8) and other diagnoses (n = 8). Most studies (n = 43 [67%]) were retrospective analyses. Data from adult patients were presented in 48 (75%) studies. Paediatric data were presented in 32 (43%) studies. Twenty‐two (34%) studies reported open surgical biopsy results, 26 (41%) reported large‐gauge NMB results, 10 (16%) studies reported results of FNB, four (6%) studies reported moderate‐gauge NMB results and five (8%) studies reported conchotome biopsy findings. Eight (13%) studies compared two different biopsy techniques. Ten open surgical biopsies studies reported the type of anaesthesia used, with general anaesthesia used in 6/10 (60%) studies. Of these six studies, five were in a paediatric population and thus only one adult study reported the use of general anaesthesia during open biopsy. Needle biopsies and conchotome biopsies were generally performed under local anaesthesia (n = 40 [95%]) and commonly in outpatient or bedside settings.

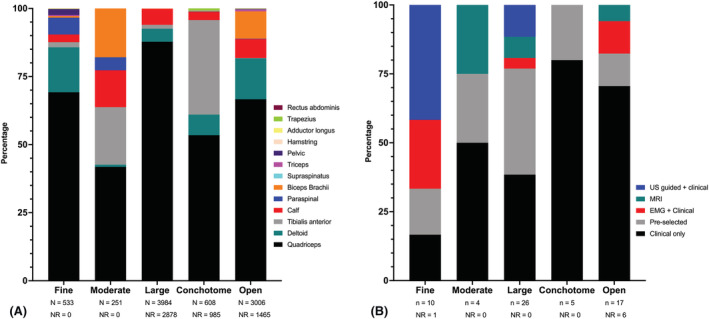

Muscle selection

Quadriceps muscles were the most commonly biopsied site, representing more than 50% of muscle biopsy sites for all types of muscle biopsy except moderate‐gauge NMB. The range of muscles sampled is illustrated in Figure 3A. Across all studies, 11 different muscle groups were sampled surgically, nine using FNB, eight using conchotome and seven using moderate‐ to large‐gauge needles. The site of muscle biopsy was selected based on imaging in only a minority of studies, with only three (4.69%) studies using MRI results to guide the selection of muscle biopsy sites and a further two (3.13%) studies using US to landmark the biopsy site. A further six (9.39%) studies used US to guide NMB for safety rather than muscle selection. An FNB was the most likely biopsy type to be image guided, typically using US (Figure 3B). The site of conchotome and open muscle biopsies performed as part of clinical care, outside of clinical trials, were selected based on clinical examination and EMG findings. There was little data evaluating the role of imaging to guide or inform muscle biopsies, based on radiological evidence of active myopathy. An uncontrolled series reported a diagnostic yield of 93% from US‐targeted biopsies [29]. The results from the single study to compare US‐targeted biopsies to those guided by clinical and EMG findings alone suggested US targeting of muscle sites was not superior to the selection of muscles on clinical and/or EMG findings alone [56]. Inclusion of MRI as part of the diagnostic evaluation for idiopathic inflammatory myopathies showed that sampling a muscle of intense T2‐weighted signal reduced the false negative biopsy rate to 0.19 compared with the overall cohort false negative biopsy rate of 0.23 [23]. One small study suggested a 100% diagnostic yield of biopsies from sites selected by positive MRI and additional targeting of biopsy site using US at the time of the procedure [51].

FIGURE 3.

Site of muscle biopsy. (A) The range of muscles sampled using various muscle biopsy techniques. (B) Muscle selection strategies employed for various muscle biopsy techniques. ‘Fine’, ‘moderate’ and ‘large’ refer to needle biopsy size. Cohorts in which the needle size was not described have been excluded. N: number of biopsies; n: number of studies; NR: not reported.

Sample yield

Thirty‐eight studies quantified the yield of muscle tissue from the biopsy technique under investigation; however, results were variably reported (Table 2). Thirty‐nine studies reported the rate of inadequate tissue sampling to permit histological analysis. Not unexpectedly, the largest tissue samples were obtained from open surgical biopsies. There was a graded relationship between the size of the needle used for NMB and the frequency of inadequate tissue sampling. However, only FNB had an inadequate tissue sample frequency of more than 4%.

TABLE 2.

Muscle biopsy sample yield.

| Biopsy type | Sample yield | Rate of inadequate sampling for histological analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume | Fibres per section | Weight (mg) | Range | Percentage | |

| Open [8, 9, 11, 14, 17, 18, 22, 24, 63, 65, 69, 70] |

1–3 × 1 cm3 pieces n = 6 studies |

NR | NR |

0% to 5% n = 10 studies |

4/1294 (0.3%) |

| Fine‐gauge needle [25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 65, 67, 70] |

2 × 0.2 cm3 pieces n = 1 study |

min: 144 (38–286) a max: 500 n = 5 studies |

min: 4.2 ± 2.7 mg d max: 55 ± 17 mg d n = 5 studies |

0% to 15% n = 7 studies |

68/598 (11.4%) |

| Moderate‐gauge needle; no vacuum [33] | NR |

125 (80–40) a n = 1 study |

12–28 mg b n = 1 study |

NR | NR |

| Moderate‐gauge needle with vacuum [32, 34, 35] | NR | NR |

min: 190 mg (80–500 mg) c max: 377–550 mg b n = 2 studies |

0% to 8% n = 3 studies |

8/242 (3.3%) |

| Large‐gauge needle; no vacuum [37, 38, 39, 40, 44, 45, 46, 52, 53, 55, 66, 67, 68] | NR |

min: 400–1200 b max (infants): 5000–10,000 b max (adults): 1060–1350 b n = 4 studies |

min: 37 ± 3 mg e max: 217 ± 89 mg d n = 8 studies |

0% to 8.3% n = 9 studies |

39/2312 (1.7%) |

| Large‐gauge needle with vacuum [36, 41, 42, 43, 47, 48, 50, 51, 54, 64] |

2 × 0.5–1 cm3 pieces n = 1 study |

425 (288–623) c n = 1 study |

min: 61.5 ± 15.7 mg d max: 233 ± 41.6 mg d n = 8 studies |

0% to 8% n = 8 studies |

29/14,027 (0.2%) |

| Conchotome [59, 60, 61, 62, 64] | NR |

500 (100–2000) c n = 1 study |

min: 23–123 mg b max: 500–1000 mg b n = 5 studies |

0% to 3% n = 4 studies |

26/1500 (1.8%) |

Note: Grey shaded boxes = data not reported for specific biopsy type.

Abbreviations: max, maximum; mg, milligrams; min, minimum; NR, not reported.

Median (IQR).

Range.

Mean (range).

Mean ± SD.

Mean ± SE.

Diagnostic yield

Thirty‐four (53%) studies provided data on the diagnostic yield of the muscle biopsies (Table 3). Muscle biopsy findings contributed to a clinical diagnosis in 31% to 100% of procedures. The tests performed on muscle tissue were not standardised across studies, which may have contributed to the variable diagnostic yield observed. Only 11 studies reported isolating genetic material from muscle tissue for analysis; the majority of these were published after 2007 and performed targeted gene profiling [11, 12, 18, 24, 26, 30, 36, 43, 47, 54, 55]. There was no observed difference in the diagnostic yield of muscle biopsy between specific neuromuscular disorders.

TABLE 3.

Diagnostic yield of muscle biopsy procedures.

| Biopsy type | Frequency of diagnostic tests performed on muscle | Biopsy contributed to the diagnosis a | Specific pathological findings observed | Normal histological findings | Nonspecific or nondiagnostic findings observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open [8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 69, 70] |

MS and HC (100%) IHC (70%) EM (60%) Western blot (10%) Metabolic studies (30%) |

34% to 91% n = 9 studies N = 1317 total biopsies |

23% to 80% n = 10 studies N = 2573 total biopsies |

9% to 41% n = 11 studies N = 1917 total biopsies |

9% to 53% n = 13 studies N = 3038 total biopsies |

| Fine‐gauge needle [25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 65, 67, 70] |

MS and HC (100%) IHC (0%) EM (33%) Western blot (0%) Metabolic studies (33%) |

43% to 80% n = 4 studies N = 327 total biopsies |

67% n = 1 study N = 55 biopsies |

13% to 30% n = 2 studies N = 260 total biopsies |

13% to 48% n = 4 studies N = 417 total biopsies |

| Moderate‐gauge needle with vacuum [34] | NR |

38% n = 1 study N = 102 biopsies |

NR |

17% n = 1 study N = 102 biopsies |

36% n = 1 study N = 102 biopsies |

| Large‐gauge needle; no suction [37, 39, 45, 50] |

MS and HC (100%) IHC (0%) EM (100%) Western blot (0%) Metabolic studies (100%) |

31% to 100% n = 2 studies N = 56 total biopsies |

49% to 58% n = 2 studies N = 940 total biopsies |

18% to 28% n = 3 studies N = 972 total biopsies |

23% to 41% n = 2 studies N = 932 total biopsies |

| Large‐gauge with suction [51, 54] |

MS and HC (100%) IHC (100%) EM (0%) Western blot (0%) Metabolic studies (0%) |

54% to 91% n = 2 studies N = 164 total biopsies |

35% n = 1 study N = 153 biopsies |

8% n = 1 study N = 153 biopsies |

9% to 37% n = 2 studies N = 164 total biopsies |

| Conchotome [59, 60, 62] |

MS and HC (100%) IHC (100%) EM (50%) |

NR |

26% to 56% n = 3 studies N = 1268 total biopsies |

21% to 34% n = 3 studies N = 1268 total biopsies |

13% to 40% n = 3 studies N = 1268 total biopsies |

Note: Grey shaded boxes = data not reported for specific biopsy type. Only studies that reported the diagnostic yield of initial diagnostic muscle biopsies are presented. Studies evaluating the yield of repeat muscle biopsies are excluded from this table.

Abbreviations: EM, electron microscopy; HC, histochemistry; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MS, morphological stains; n, number of studies; N, number of biopsies; NR, not reported.

All analyses performed on biopsied tissue, not limited to histological findings.

A comparison between the diagnostic yield of various muscle biopsy techniques was performed in eight studies. One study compared conchotome biopsy to a large‐gauge NMB, with both procedures performed in all study participants under local anaesthetic. Study results indicated equivalent diagnostic utility for both procedures but less pain resulting from a conchotome biopsy [64]. Two studies made a direct comparison between the diagnostic yield of NMB, one study comparing FNB and the second comparing large‐gauge NMB to open surgical biopsies performed in the same patient. These studies both demonstrated equivalent diagnostic information can be gained from both procedures [65, 68]. Retrospective chart review of the diagnostic yield of FNB compared with open biopsy at two different centres suggested a reduced sensitivity (80% to 83%) of FNB for the detection of neuromuscular disorders compared with open biopsy (95% to 98%). However, in these studies, both procedures were not performed in each patient, and the diagnostic yield of each respective procedure was calculated from tissue samples taken from different patients [69, 70].

The clinical utility of repeat muscle biopsy was investigated in single‐centre retrospective studies [7, 12, 59]. Repeat muscle biopsy secured a diagnosis in 24% of patients and supported treatment decisions in a further 45% of patients in one series [12]. A second case series found that 47% of repeat muscle biopsies demonstrated different findings compared with initial biopsy results [7]. Repeat biopsy findings were more likely to be clinically relevant if the procedure was performed in a patient with a definite abnormal and inflammatory initial biopsy, ongoing proximal muscle weakness without myalgia and if the follow‐up biopsy showed evidence of polymyositis or inclusion body myositis [7].

Complications

Muscle biopsy, irrespective of the biopsy technique, was generally well tolerated with a complication rate of less than 3% for all complications except haematoma or ecchymosis (Table 4). Haematoma or ecchymoses were reported in up to one‐third of patients undergoing large‐gauge NMB [44]. However, these results are from a study that actively screened for postprocedure bleeding complications with US [44]. Twenty‐one (33%) studies that included 2713 biopsies reported zero complications from any type of muscle biopsy procedure. There were no complications reported in any studies that performed a moderate‐gauge NMB without vacuum. Wound infections were most commonly reported in open surgical muscle biopsy studies, affecting between 1% and 5% of biopsy sites [70] as compared with up to 0.5% of biopsy sites with large‐gauge NMB [42, 49, 54]. Where reported, surgical incisions were ≥2 cm in length for 75% of open biopsy studies [17, 19, 22, 63] and ≤1 cm for 89% of percutaneous biopsy studies [25, 26, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 41, 42, 43, 44, 47, 48, 50, 52, 53, 54, 56, 57, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 69, 70]. Persistent adverse events following muscle biopsy were uncommonly reported, with a 3.1% rate of keloid scarring reported in one open surgical biopsy study [15], and persistent sensory disturbance at biopsy site reported in 0.03% to 1.8% NMB studies [27, 42, 54, 59]. Ongoing weakness was reported in 2.3% of patients in one study following conchotome biopsy [60].

TABLE 4.

Complications of muscle biopsy.

| Open | Needle not described | Fine gauge | Moderate gauge with vacuum | Large gauge; no vacuum | Large gauge with vacuum | Conchotome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haematoma or ecchymosis |

2.3% n = 1 [15] N = 479 |

NR |

1% to 2% N = 318 |

23% n = 1 [35] N = 13 |

36% n = 1 [44] N = 11 |

0.01% to 1.4% N = 16,090 |

0.6% to 1.2% N = 395 |

| Bleeding | NR | NR | NR |

0.7%–2.9% N = 230 |

NR |

0.01% to 0.4% N = 15,711 |

NR |

| Vascular injury |

0.6% n = 1 [11] N = 169 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Keloid scar |

3.1% n = 1 [15] N = 479 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Persistent skin erythema (>3 days) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

1.27% n = 1 [49] N = 496 |

NR |

| Wound infection |

1% to 5% n = 2 [70] N = 519 |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

0% to 0.5% N = 15,711 |

NR |

| Malignant hyperthermia |

0% to 1.1% N = 967 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Persistent pain (>3 days) or excessive intraprocedural pain | NR | NR |

1% n = 1 [28] N = 98 |

0% n = 1 [32] N = 128 |

0.5% n = 1 [44] N = 444 |

0.03% to 2.4% N = 15,794 |

0.7% to 2.3% N = 326 |

| Persistent numbness or hyperesthesia at the biopsy site | NR | NR |

1.8% n = 1 [27] N = 55 |

NR | NR |

0.03% to 0.15% N = 15,215 |

0.7% n = 1 [59] N = 149 |

| Persistent weakness | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

2.3% n = 1 [60] N = 86 |

| Anxiety or panic episode | NR |

5% n = 1 [56] N = 40 |

NR | NR | NR |

0.8% n = 1 [49] N = 496 |

NR |

| Presyncope or syncope | NR | NR |

0.5% n = 1 [30] N = 220 |

NR |

1.4% n = 1 [44] N = 444 |

0.2% n = 1 [48] N = 379 |

1.3% n = 1 [62] N = 160 |

Note: Grey shaded boxes = complication not reported for specific muscle biopsy procedure. Data presented from studies that explicitly reported complications from the procedure.

Abbreviations: n, number of studies; N, number of biopsies across all indicated studies; NR, not reported.

In general, muscle biopsies were well tolerated by patients, with periprocedure pain being the most frequently reported adverse event. Numerical rating scores of periprocedure pain were between 3.2 and 5.2 (maximum score 10), for various muscle biopsy techniques [25, 26, 35, 63, 67]. Pain persisting for longer than 14 days was infrequently reported [28, 60, 61]. Of the few studies that evaluated the patient experience of the muscle biopsy, a large‐gauge needle biopsy was reported to be more painful than an open surgical biopsy [63], conchotome biopsy [64] and FNB [67].

DISCUSSION

The results of this systematic literature review demonstrate that muscle biopsy is a safe and generally well‐tolerated investigation that aids the diagnosis of many neuromuscular disorders. Various percutaneous techniques have been reported, and all except the fine‐needle approach yield sample sizes sufficient for histological analysis. Moreover, the diagnostic yield of a moderate‐ to large‐gauge NMB or conchotome biopsy appears equivalent to that of an open surgical biopsy. These findings have important implications for clinical practice in that percutaneous muscle biopsy can be safely performed at the bedside with only local anaesthesia or light sedation. Cardiorespiratory complications of neuromuscular disease are common, and a diagnostic procedure that does not require general anaesthesia reduces the overall risk to the patient. Repeat biopsies to reassess the diagnosis or monitor response to therapy have been demonstrated to be of clinical utility. The rare persistent adverse event following muscle biopsy suggests that serial assessment of muscle histology may be a viable method of monitoring response to therapy either in clinical practice or clinical trials.

The overall diagnostic yield of each muscle biopsy technique was not possible to calculate because of the heterogeneous data available. Heterogeneous study methodologies and patient selection as well as variable outcomes presented precluded any meta‐analysis. Moreover, the medical and surgical specialities involved in requesting, performing and interpreting muscle biopsies vary within and between institutions and this heterogeneity in personnel may influence the diagnostic outcome of muscle biopsy. Variability in muscle processing protocols between laboratories—for instance, the use of a dissection microscope to orient fibres—may additionally affect the quality of the muscle sample. Importantly, more recent diagnostic advances such as genetic and molecular analyses are likely to improve upon the diagnostic yield of muscle biopsies reported in early studies. While the ‘clinical utility’ of biopsies was a frequent endpoint, the definition of a useful test is highly variable depending on the clinical context and question. Measurement of utility based upon a change in diagnosis ignores other important indications for obtaining a tissue sample. These may include confirmation of diagnosis, exclusion of potentially progressive and fatal myopathic conditions, assigning pathogenicity to molecular variants using RNA sequencing, providing functional insights by linking genetic abnormalities to morphological phenotypes and biobanking for research. The few comparative studies included in this review suggest a reduced sensitivity of FNB for the detection of muscle pathology. However, the diagnostic utility of conchotome and moderate‐ to large‐gauge needle techniques appears equivalent to open surgical biopsy.

Few studies included in this review systematically evaluated the role of imaging to select muscle biopsy sites. Certain myopathies, particularly idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, are characterised by patchy muscle involvement, and false negative biopsies may occur as a result of sampling error. Whether imaging may be used to select a representative muscle for histological examination and hence improve the diagnostic utility of muscle biopsies is thus of interest. One study included in this review concluded that a biopsy of an MRI hyperintense muscle had a lower false negative rate than a biopsy of an MRI negative muscle [23]. This concurs with an earlier study of 25 patients (not included in this review because the muscle biopsy technique was not described) that showed the false negative rate of a muscle biopsy is reduced when the biopsy site is selected on the basis of abnormal MRI findings [71]. Aside from MRI, there is growing interest in the role of novel US techniques to identify muscle pathology [72]. Another benefit of sonographically guided biopsy is that critical structures may be visualised in real time, potentially permitting a wider range of muscles to be safely sampled. Larger prospective studies are needed to definitively demonstrate that image‐directed biopsies are superior to biopsies guided by clinical or EMG findings.

This review has limitations. We intentionally used a comprehensive and inclusive search strategy to capture as many articles that reported muscle biopsy techniques as possible. It is possible this review strategy did not identify studies that did not list muscle biopsy in the abstract or keywords. Our review was limited to English‐language studies and full‐length texts, so it is possible that this study did not include pertinent articles published in other languages or data published in conference proceedings. Additionally, the heterogeneous nature of the studies evaluated prevented meta‐analysis of data and pooling of study results. Importantly, the published literature may not reflect real‐world practice or the diagnostic utility of muscle biopsy; therefore, clinical recommendations regarding specific clinical scenarios cannot be made as a result of this systematic literature review alone. To ensure this review was as representative of clinical practice as possible, we elected to include case series and observational studies. Future endeavours may wish to audit institutional practices worldwide to ascertain a truer representation of the scope of muscle sampling techniques. The strength of our conclusions is limited by the heterogeneity of the data available. However, to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of muscle biopsy techniques and is the largest and most comprehensive comparison of the utility and complications of muscle biopsies to date.

What does the future hold for muscle biopsies?

Despite the advancements in genetic profiling, autoantibody testing and the increasing sophistication of muscle imaging techniques, muscle biopsy continues to play an important role in the evaluation of myopathies. Additionally, while this review did not specifically evaluate the diagnostic role of genetic and molecular analysis of muscle tissue, it is recognised the advent of high‐throughput, integrative omics technologies has further accelerated our ability to interrogate tissues to an extraordinary level of molecular detail. Although a diagnosis of specific myopathies such as muscular dystrophy or dermatomyositis may no longer require a muscle biopsy [1, 73], it is likely that analysis of affected tissues obtained via muscle biopsy will play an increasingly important role in the era of personalised, omics‐informed neuromuscular medicine. It is foreseeable that molecular signatures obtained from muscle tissue will be increasingly used to understand disease pathogenesis, guide therapeutic decisions and inform individual patient prognostics.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results demonstrate that the clinical utility of moderate‐ to large‐gauge NMB and conchotome biopsies appears equivalent to that of open surgical biopsies. All muscle biopsy techniques are safe and well tolerated. NMB and conchotome biopsies have the additional benefit of being procedures that can be performed under local anaesthetic at the bedside and do not require a large incision, a surgical team or theatre time. Therefore, given the apparent diagnostic equivalence of all biopsy techniques, NMB or conchotome biopsy could be considered when histopathological evaluation is indicated in cases of suspected myopathy.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Laura Ross and Jessica Day are responsible for the study conception and design. Laura Ross, Huon Wong and Jessica Day are responsible for the data collection and analysis. Laura Ross, Penny McKelvie, Katrina Reardon, Huon Wong, Ian Wicks and Jessica Day presented the data. Laura Ross and Jessica Day prepared the first draft of the manuscript. Laura Ross, Penny McKelvie, Katrina Reardon, Huon Wong, Ian Wicks and Jessica Day edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No authors have any conflict of interest to declare.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval was not required for this study.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/nan.12888.

Supporting information

Data S1. Index 1: Data extraction template

Ross L, McKelvie P, Reardon K, Wong H, Wicks I, Day J. Muscle biopsy practices in the evaluation of neuromuscular disease: A systematic literature review. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2023;49(1):e12888. doi: 10.1111/nan.12888

Funding information LR is supported by an Arthritis Australia—Australian Rheumatology Association (Victoria) Fellowship. JD is the recipient of the Sylvia and Charles Viertel Charitable Foundation Clinical Investigator Award, the John T Reid Charitable Trusts Centenary Fellowship, the RACP Australian Rheumatology Association & D.E.V Starr Research Establishment Fellowship and the Royal Melbourne Hospital Victor Hurley Medical Research Grant in Aid. IW is the recipient of a National Health and Medical Research Council Medical Research Future Fund Practitioner Fellowship (1154325) and receives research support from the John T Reid Charitable Trusts.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schoser B. Diagnostic muscle biopsy: is it still needed on the way to a liquid muscle pathology? Curr Opin Neurol. 2016;29(5):602‐605. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Joyce NC, Oskarsson B, Jin LW. Muscle biopsy evaluation in neuromuscular disorders. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2012;23(3):609‐631. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ekblom B. The muscle biopsy technique. Historical and methodological considerations. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27(5):458‐461. doi: 10.1111/sms.12808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bergström J. Percutaneous needle biopsy of skeletal muscle in physiological and clinical research. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1975;35(7):609‐616. doi: 10.3109/00365517509095787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nix JS, Moore SA. What every neuropathologist needs to know: the muscle biopsy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2020;79(7):719‐733. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlaa046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Br Med J. 2009;339(jul21 1):b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aburahma SK, Wicklund MP, Quan D. Take two: utility of the repeat skeletal muscle biopsy. Muscle Nerve. 2019;60(1):41‐46. doi: 10.1002/mus.26484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buchthal F, Kamieniecka Z. The diagnostic yield of quantified electromyography and quantified muscle biopsy in neuromuscular disorders. Muscle Nerve. 1982;5(4):265‐280. doi: 10.1002/mus.880050403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Constantinides VC, Papahatzaki MM, Papadimas GK, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of muscle biopsy and electromyography in 123 patients with neuromuscular disorders. In Vivo. 2018;32(6):1647‐1652. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gibertoni M, Colombo A, Schoenhuber R, et al. Muscle CT, biopsy and EMG in diagnosis of neuromuscular diseases. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1987;8(1):51‐53. doi: 10.1007/BF02361435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gibreel WO, Selcen D, Zeidan MM, Ishitani MB, Moir CR, Zarroug AE. Safety and yield of muscle biopsy in pediatric patients in the modern era. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49(9):1429‐1432. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.02.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goutman SA, Prayson RA. Role of repeat skeletal muscle biopsy: how useful is it? Muscle Nerve. 2013;47(6):835‐839. doi: 10.1002/mus.23697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jamshidi R, Harrison MR, Lee H, Nobuhara KK, Farmer DL. Indication for pediatric muscle biopsy determines usefulness. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(12):2199‐2201. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.08.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kokotis P, Papadimas GK, Zouvelou V, Zambelis T, Manta P, Karandreas N. Electrodiagnosis and muscle biopsy in asymptomatic hyperckemia. Int J Neurosci. 2016;126(6):514‐519. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2015.1038534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laguno M, Miro O, Perea M, Picon M, Urbano‐Marquez A, Grau JM. Muscle diseases in elders: a 10‐year retrospective study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(6):M378‐M384. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.6.M378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lai CH, Melli G, Chang YJ, et al. Open muscle biopsy in suspected myopathy: diagnostic yield and clinical utility. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(1):136‐142. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02765.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reynolds EM, Thompson IM, Nigro MA, Kupsky WJ, Klein MD. Muscle and nerve biopsy in the evaluation of neuromuscular disorders: the surgeon's perspective. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34(4):588‐590. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(99)90080-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shaibani A, Jabari D, Jabbour M, Arif C, Lee M, Rahbar MH. Diagnostic outcome of muscle biopsy. Muscle Nerve. 2015;51(5):662‐668. doi: 10.1002/mus.24447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shapiro F, Athiraman U, Clendenin DJ, Hoagland M, Sethna NF. Anesthetic management of 877 pediatric patients undergoing muscle biopsy for neuromuscular disorders: a 20‐year review. Paediatr Anaesth. 2016;26(7):710‐721. doi: 10.1111/pan.12909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sujka JA, Le N, Sobrino J, et al. Does muscle biopsy change the treatment of pediatric muscular disease? Pediatr Surg Int. 2018;34(7):797‐801. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4285-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tenny SO, Schmidt KP, Follett KA. Association of preoperative diagnosis with clinical yield of muscle biopsy. Cureus. 2018;10(10):e3449. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thavorntanaburt S, Tanboon J, Likasitwattanakul S, et al. Impact of muscle biopsy on diagnosis and management of children with neuromuscular diseases: a 10‐year retrospective critical review. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53(3):489‐492. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van De Vlekkert J, Maas M, Hoogendijk JE, De Visser M, Van Schaik IN. Combining MRI and muscle biopsy improves diagnostic accuracy in subacute‐onset idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Muscle Nerve. 2015;51(2):253‐258. doi: 10.1002/mus.24307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang K, Iannaccone S, Burkhalter LS, Reisch J, Cai C, Schindel D. Role of nerve and muscle biopsies in pediatric patients in the era of genetic testing. J Surg Res. 2019;243:27‐32. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.04.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Agten A, Verbrugghe J, Stevens S, et al. Feasibility, accuracy and safety of a percutaneous fine‐needle biopsy technique to obtain qualitative muscle samples of the lumbar multifidus and erector spinae muscle in persons with low back pain. J Anat. 2018;233(4):542‐551. doi: 10.1111/joa.12867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tobina T, Nakashima H, Mori S, et al. The utilization of a biopsy needle to obtain small muscle tissue specimens to analyze the gene and protein expression. J Surg Res. 2009;154(2):252‐257. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Campellone JV, Lacomis D, Giuliani MJ, Oddis CV. Percutaneous needle muscle biopsy in the evaluation of patients with suspected inflammatory myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(10):1886‐1891. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cote AM, Lissette J, Adelman LS, Munsat TL. Needle muscle biopsy with the automatic Biopty instrument. Neurology. 1992;42(11):2212‐2213. doi: 10.1212/WNL.42.11.2212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lindequist S, Larsen C, Schrøder HD. Ultrasound guided needle biopsy of skeletal muscle in neuromuscular disease. Acta Radiol. 1990;31(4):411‐413. doi: 10.1177/028418519003100417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Magistris MR, Kohler A, Pizzolato G, et al. Needle muscle biopsy in the investigation of neuromuscular disorders. Muscle Nerve. 1998;21(2):194‐200. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Paoli A, Pacelli QF, Toniolo L, Miotti D, Reggiani C. Latissimus dorsi fine needle muscle biopsy: a novel and efficient approach to study proximal muscles of upper limbs. J Surg Res. 2010;164(2):e257‐e263. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.05.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barthelemy F, Woods JD, Nieves‐Rodriguez S, et al. A well‐tolerated core needle muscle biopsy process suitable for children and adults. Muscle Nerve. 2020;62(6):688‐698. doi: 10.1002/mus.27041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bylund P, Eriksson E, Jansson E, Nordberg L. A new biopsy needle for percutaneous biopsies of small skeletal muscles and erector spinae muscles. Int J Sports Med. 1981;2(2):119‐120. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1034595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gallo A, Abraham A, Katzberg HD, Ilaalagan S, Bril V, Breiner A. Muscle biopsy technical safety and quality using a self‐contained, vacuum‐assisted biopsy technique. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28(5):450‐453. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lassche S, Janssen BH, Ijzermans T, et al. MRI‐guided biopsy as a tool for diagnosis and research of muscle disorders. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2018;5(3):315‐319. doi: 10.3233/JND-180318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cotter JA, Yu A, Kreitenberg A, et al. Suction‐modified needle biopsy technique for the human soleus muscle. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2013;84(10):1066‐1073. doi: 10.3357/ASEM.3632.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Derry KL, Nicolle MN, Keith‐Rokosh JA, Hammond RR. Percutaneous muscle biopsies: review of 900 consecutive cases at London Health Sciences Centre. Can J Neurol Sci. 2009;36(2):201‐206. doi: 10.1017/S0317167100006569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Di Liberti JH, D'Agostino AN, Cole G. Needle muscle biopsy in infants and children. J Pediatr. 1983;103(4):566‐570. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(83)80585-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Edwards RH, Lewis PD, Maunder C, Pearse AG. Percutaneous needle biopsy in the diagnosis of muscle diseases. Lancet. 1973;2(7837):1070‐1071. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(73)92672-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Evans WJ, Phinney SD, Young VR. Suction applied to a muscle biopsy maximizes sample size. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14(1):101‐102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hennessey JV, Chromiak JA, Della Ventura S, Guertin J, MacLean DB. Increase in percutaneous muscle biopsy yield with a suction‐enhancement technique. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82(6):1739‐1742. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.6.1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Highstead RG, Tipton KD, Creson DL, Wolfe RR, Ferrando AA, Wolfe RR. Incidence of associated events during the performance of invasive procedures in healthy human volunteers. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98(4):1202‐1206. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01076.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Iachettini S, Valaperta R, Marchesi A, et al. Tibialis anterior muscle needle biopsy and sensitive biomolecular methods: a useful tool in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Eur J Histochem. 2015;59(4):251‐257. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2015.2562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kirby RL, Bonen A, Belcastro AN, Campbell CJ. Needle muscle biopsy: techniques to increase sample sizes, and complications. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1982;63(6):264‐268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Leong KH, Boey ML, Poh WT, et al. Clinical usefulness of needle muscle biopsy in twenty‐four patients with proximal weakness. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22(3):316‐318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maunder‐Sewry CA, Dubowitz V. Needle muscle biopsy for carrier detection in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Sci. 1981;49(2):305‐324. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(81)90087-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Melendez MM, Vosswinkel JA, Shapiro MJ, et al. Wall suction applied to needle muscle biopsy—a novel technique for increasing sample size. J Surg Res. 2007;142(2):301‐303. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mubarak SJ, Chambers HG, Wenger DR. Percutaneous muscle biopsy in the diagnosis of neuromuscular disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12(2):191‐196. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199203000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Neves JM, Barreto G, Boobis L, et al. Incidence of adverse events associated with percutaneous muscular biopsy among healthy and diseased subjects. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2012;22(2):175‐178. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01264.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pamphlett R, Harper C, Tan N, Kakulas BA. Needle muscle biopsy: will it make open biopsy obsolete? Aust N Z J Med. 1985;15(2):199‐202. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1985.tb04005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Raithatha A, Ashraghi MR, Lord C, Limback‐Stanic C, Viegas S, Amiras D. Ultrasound‐guided muscle biopsy: a practical alternative for investigation of myopathy. Skeletal Radiol. 2020;49(11):1855‐1859. doi: 10.1007/s00256-020-03484-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schwarz HA, Slavin G, Ward P, Ansell BM. Muscle biopsy in polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a clinicopathological study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1980;39(5):500‐507. doi: 10.1136/ard.39.5.500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sengers RCA, Stadhouders AM, Notermans SLH. Percutaneous needle biopsy of skeletal muscle in childhood. Eur J Pediatr. 1980;135(1):21‐29. doi: 10.1007/BF00445888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tarnopolsky MA, Pearce E, Smith K, Lach B. Suction‐modified Bergström muscle biopsy technique: experience with 13,500 procedures. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43(5):717‐725. doi: 10.1002/mus.21945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang LH, Friedman SD, Shaw D, et al. MRI‐informed muscle biopsies correlate MRI with pathology and DUX4 target gene expression in FSHD. Hum Mol Genet. 2019;28(3):476‐486. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Billakota S, Dejesus‐Acosta C, Gable K, Massey EW, Hobson‐Webb LD. Ultrasound in EMG‐guided biopsies: a prospective, randomized pilot trial. Muscle Nerve. 2016;54(4):786‐788. doi: 10.1002/mus.25201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Curless RG, Nelson MB. Needle biopsies of muscle in infants for diagnosis and research. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1975;17(5):592‐601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hafner P, Phadke R, Manzur A, et al. Electromyography and muscle biopsy in paediatric neuromuscular disorders—evaluation of current practice and literature review. Neuromuscul. 2019;29(1):14‐20. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dorph C, Nennesmo I, Lundberg IE. Percutaneous conchotome muscle biopsy. A useful diagnostic and assessment tool. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(7):1591‐1599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Henriksson KG. “Semi‐open” muscle biopsy technique. A simple outpatient procedure. Acta Neurol Scand. 1979;59(6):317‐323. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1979.tb02942.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Patel HP, Syddall HE, Martin HJ, Cooper C, Stewart C, Sayer AA. The feasibility and acceptability of muscle biopsy in epidemiological studies: findings from the Hertfordshire Sarcopenia Study (HSS). J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(1):10‐15. doi: 10.1007/s12603-011-0006-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Poulsen MB, Bojsen‐Moller M, Jakobsen J, Andersen H. Percutaneous conchotome biopsy of the deltoid and quadriceps muscles in the diagnosis of neuromuscular disorders. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2005;7(1):36‐41. doi: 10.1097/01.cnd.0000177424.88495.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dengler J, Linke P, Gdynia HJ, et al. Differences in pain perception during open muscle biopsy and Bergstroem needle muscle biopsy. J Pain Res. 2014;7:645‐650. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S69458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dietrichson P, Coakley J, Smith PEM, Griffiths RD, Helliwell TR, Edwards RH. Conchotome and needle percutaneous biopsy of skeletal muscle. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50(11):1461‐1467. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.11.1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Fukuyama Y, Suzuki Y, Hirayama Y, et al. Percutaneous needle muscle biopsy in the diagnosis of neuromuscular disorders in children. Histological, histochemical and electron microscopic studies. Brain Dev. 1981;3(3):277‐287. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(81)80050-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Greig PD, Askanazi J, Kinney JM. Needle biopsy of skeletal muscle using suction. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;160(5):467‐468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hayot M, Michaud A, Koechlin C, et al. Skeletal muscle microbiopsy: a validation study of a minimally invasive technique. Eur Respir J. 2005;25(3):431‐440. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00053404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Heckmatt JZ, Moosa A, Hutson C, Maunder‐Sewry CA, Dubowitz V. Diagnostic needle muscle biopsy. A practical and reliable alternative to open biopsy. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59(6):528‐532. doi: 10.1136/adc.59.6.528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. O'Rourke KS, Blaivas M, Ike RW. Utility of needle muscle biopsy in a university rheumatology practice. J Rheumatol. 1994;21(3):413‐424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. O'Sullivan PJ, Gorman GM, Hardiman OM, Farrell MJ, Logan PM. Sonographically guided percutaneous muscle biopsy in diagnosis of neuromuscular disease: a useful alternative to open surgical biopsy. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25(1):1‐6. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schweitzer ME, Fort J. Cost‐effectiveness of MR imaging in evaluating polymyositis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165(6):1469‐1471. doi: 10.2214/ajr.165.6.7484589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Albayda J, van Alfen N. Diagnostic value of muscle ultrasound for myopathies and myositis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020;22(11):82. doi: 10.1007/s11926-020-00947-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lundberg IE, Tjarnlund A, Bottai M, et al. 2017 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(12):2271‐2282. doi: 10.1002/art.40320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Index 1: Data extraction template

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.