Abstract

This qualitative study describes the development and evaluation of a clinical pathway to facilitate the implementation of catch‐up vaccinations for children with significant needle fear, particularly in children with developmental disabilities. The Specialist Immunization Team, based at a tertiary level teaching children's hospital, participated in process mapping activities using Motivational Interviewing (MI) techniques and reflective discussions. Team members developed a clinical pathway by incorporating parental feedback from semistructured interviews and clinical expertise from within the team, facilitated by colleagues from the Child Development Unit. A process map was developed that included process strengths and touch points with an action plan that was discussed and agreed upon. A repeat process mapping activity was conducted 16 months later. Reports from parental feedback included: positive, efficient, and successful experiences of having their child undergo catch‐up vaccinations. The experience empowered families for further procedures. Team members reported improvements in triaging appropriate children for the pathway, and an increase in confidence to interact and manage behaviors of children with significant anxiety and challenging behaviors. They also reported an increase in successful vaccinations with improved clinical judgment of facilitating the sedation pathway. This study demonstrates that using group facilitation using motivational interviewing in reflective discussions and process mapping utilizing parent and staff feedback in service improvement activities results in efficient and successful service delivery with improved patient outcomes.

Keywords: developmental‐behavioral problems, quality improvement, vaccinations

1. INTRODUCTION

Children with intellectual and developmental disabilities are one of the most disadvantaged population groups in terms of timely and appropriate access to health and preventative health care such as vaccinations. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 They are also vulnerable to complications from vaccine preventable diseases. 5 In addition, vaccination causes pain, fear, and distress and adversely impacts this population, who often miss out as a result. 1 , 6 , 7 In children with severe anxiety disorders, needle phobia, intellectual and developmental disabilities, or behavioral disorders, this distress can be so severe that attempts to vaccinate are abandoned due to significant risk of injury from fearful refusal, resulting in nonadherence to the recommended immunization schedule. 7 Repeated attempts to vaccinate further exacerbate the traumatic experience and lead to future avoidance of hospital visits, even for significant illness requiring hospitalization and or interventions. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 Whilst the literature states that fear of needles tends to improve with age, the likelihood of this occurring in a pediatric population with needle fear may be less so, particularly if direct interventions that address the fear and explore ways of a more positive experience are not available or utilized. 8 , 10 Examples of common intervention strategies used to effectively manage needle fear and phobia during vaccinations include pharmacological methods like sedation, and nonpharmacological methods like distraction techniques. 12 , 13

Despite the negative consequences of missed vaccinations, impact of needle‐based distress, and availability of well‐established intervention techniques, at present there are no best practice guidelines on how to optimally manage children with needle fear without further adding to their traumatic experiences. The development of protocols that streamline the use of needle fear management techniques has been highlighted as an important area in need of further research. 8 Further, parent satisfaction with the use of such techniques remains understudied, with little published data currently available.

This study aimed to describe the development of a clinical care pathway (“Difficult to Vaccinate” pathway) to facilitate catch‐up vaccinations for children with significant needle fear, who had not successfully been vaccinated using standard immunization procedures in mainstream settings. It also aimed to evaluate the success of the pathway using qualitative analysis of parent and staff feedback.

2. METHODS

2.1. Context

This project was conducted at a tertiary level teaching children's hospital in Sydney, in collaboration with the New South Wales Immunization Specialist Service (NSWISS) from April 2018 to October 2019. Families were referred to the NSWISS where attempts to vaccinate their children in local mainstream settings had been unsuccessful due to significant needle fear, typically in the context of needle phobia, intellectual disability, or developmental disability.

2.2. Ethical considerations

This project was approved through the hospital clinical governance unit as a quality improvement project, which was deemed not to require research ethics approval. 14

2.3. Intervention

This was a quality improvement project incorporating qualitative methods using the Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act cycle. 15 Two stages were used in the process of developing and evaluating the “Difficult to Vaccinate” clinical care pathway:

Initial development and evaluation of clinical pathway

Follow‐up evaluation

2.3.1. Initial development and evaluation of clinical pathway

In the initial phase (April 2018), the chief investigator worked with staff participants to generate a draft process map that represented the patient journey from prereferral through to discharge. The sessions were facilitated by an independent staff member from the Child Development Unit and involved process mapping and motivational interviewing techniques to develop an improved clinical pathway through the NSWISS. Process mapping is a form of clinical audit that examines how the patient journey is managed by separating a process of care into a series of consecutive events. 16 It can be used to identify barriers and bottlenecks in a care pathway and allows people to analyze and agree on the most efficient routes to reengineer or improve a process. Consistent with previous research in the field, 17 group motivational interview techniques using the OARS (open ended, affirmation, reflection, and summary) strategies were used to facilitate discussion and increase motivation to implement service improvement strategies.

The usual patient service pathway in place at that time was described and broken into discrete steps. This map was drawn on a board in front of the participants, to allow them to visualize the patient journey through their service, to critically analyze the steps in the process, and to identify strengths and areas for improvement. Incorporation of reasonable adjustments for the child with intellectual or developmental disability with anxiety and behaviors of concern in the pathway were discussed and agreed upon, and an improved clinical pathway was developed.

Following the implementation of this adjusted clinical pathway for 2 months, interviews with parents of children and adolescents who had utilized the “Difficult to Vaccinate” pathway services at NSWISS were conducted. They were recruited from the referral database of the service and gave verbal consent to participate. Interviews followed a semistructured interview guide that requested participants' reported experiences accompanying their child for catch‐up immunization with the service. An interview guide is included in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Interview Brief.

|

Specialist Immunization Clinic Pathway: Difficult to vaccinate children Interview Brief |

|

Introduction and purpose of the study Confidentiality Consent |

|

|

|

|

Following the parent interviews, in June 2018, a second focus group was conducted with members of the NSWISS team, consisting of a Clinical Nurse Consultant (CNC) and two pediatric doctors. During the focus group session with staff, parent experience themes were fed back to the staff using an additional process mapping exercise, which then incorporated both staff and parent viewpoints to shape the development of the “Difficult to Vaccinate” clinical care pathway. Following this second focus group, the process map was finalized, and the revised “Difficult to Vaccinate” clinical pathway was re‐implemented at the NSWISS.

2.3.2. Follow‐up evaluation

Following an interval of 14–16 months, another group of parents whose children had been seen under the revised “Difficult to Vaccinate” clinical pathway was interviewed. Qualitative analysis was conducted on interview transcript to identify if initial themes were still present and if any of the issues raised were addressed in recent experiences. A focus group was also repeated with the same staff members and one additional doctor, to evaluate the efficacy of the strategies that had been implemented.

2.4. Analysis

The parent interviews and staff focus group discussions were voice recorded and transcribed verbatim, and field notes were also taken. The chief investigator conducted all interviews, and recruitment and interviews continued until they were satisfied that the data indicated saturation. Qualitative analysis using the Framework Method 18 was then conducted on the interview and session discussion transcripts, to identify themes within the parents' and staff feedback. The Framework Method sits within a broad family of analysis methods often termed thematic analysis or qualitative content analysis often used in social, policy and health research. These approaches look at common and discrepant codes in data leading to identifying relationships between different parts of the data then drawing on descriptive and/or explanatory conclusions aggregated into themes. Three independent clinician researchers reviewed the transcripts and used a framework analysis to code data and identify them into agreed key themes and subthemes. Results from these analyses were used to further inform the improvement of the “Difficult to Vaccinate” clinical pathway and evaluate its success in terms of parent and staff satisfaction in its first and second iteration.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants

From September 2017 to February 2020, 36 children were seen by the NSWISS. In total, 14 parents of children aged 6–15 years consented to be interviewed. Eight parents were interviewed in the initial phase of the project, and 6 were interviewed during the follow‐up phase. Parents ranged in age from 40 to 60 years of age (M = 48.36, SD = 4.98), and were more commonly mothers (n = 11) than fathers (n = 3). The most common diagnosis leading to referral was autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Other diagnoses included needle phobia, intellectual disability, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, depression, and Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Child and parent characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Age of parent and child diagnoses.

| Initial interviews | Age of Parent | Child's Diagnosis or Diagnoses |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 40, Mother | Needle Phobia |

| P2 | 50, Mother | Autism, Mild Intellectual Disability |

| P3 | 53, Father | Autism (Twins) |

| P4 | 53, Father | Autism |

| P5 | 46, Mother | Autism, Intellectual Disability |

| P6 | 46, Mother | Mild ADHD a , Needle Phobia |

| P7 | 48, Mother | ADHD a , anxiety, Needle Phobia |

| P8 | 50, Mother | Needle Phobia |

| 14–18 months post session | ||

| P9 | 60, Father | ADHD |

| P10 | 49, Mother | Autism, Intellectual Disability |

| P11 | 49, Mother | Autism |

| P12 | 40, Mother | Autism |

| P13 | 45, Mother | Autism, Generalized Anxiety |

| P14 | 48, Mother | Autism, ADHD, PTSD b , anxiety and depression. |

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

3.2. Initial evaluation of clinical pathway

Qualitative analysis of interviews of eight parents of children who had been seen at NSWISS prior to the implementation of the improved “Difficult to Vaccinate” clinical pathway generated 8 major themes and 12 subthemes. Table 3 presents these themes and subthemes.

TABLE 3.

Themes and subthemes from initial parent interviews.

| Parent Theme 1 | Very happy and relieved that child did well through the support and structure of the service |

|---|---|

| Subthemes |

|

| Theme 2 | Aspects for improvement |

| Subthemes |

|

| Theme 3 | Polarizing views on how much info and preparation suited for the child with needle phobia. |

| Subthemes |

|

| Theme 4 | Having a positive experience led to empowerment of these children. |

| Theme 5 | Need for other parents to know about the service—better advertising |

| Theme 6 | Need for Information Pack to contain location map and staff at reception and Bandaged bear to know the location of the clinic |

| Theme 7 | Parent concern about the permanence of the clinic—loss of clinic room. Need for the clinic to have their own clinical space and equipment |

| Theme 8 | Fears for the Future—concerns that the needle phobia needed to be overcome if their child needed tests or interventions done in future as adults. |

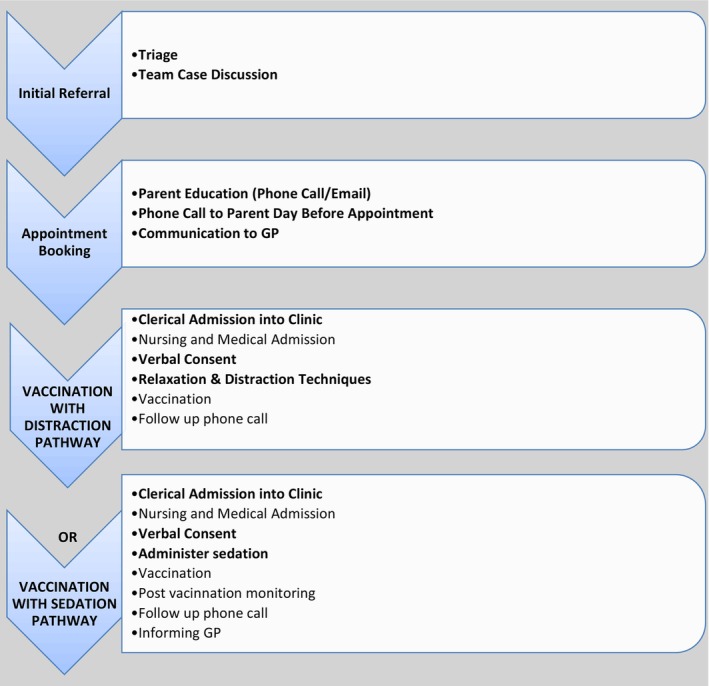

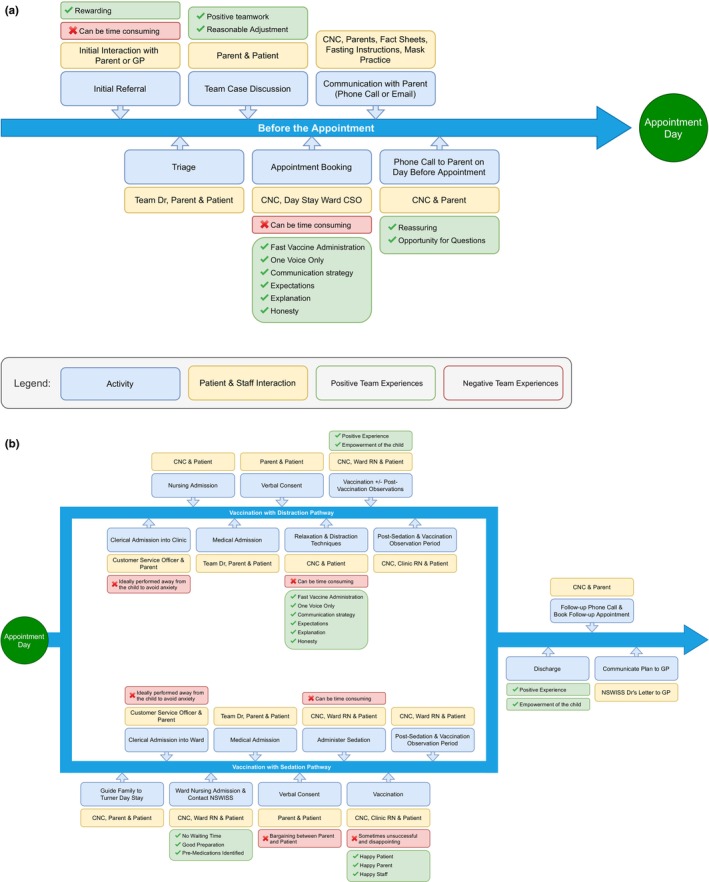

In the staff focus group, team members worked together to develop the process map, identify existing aspects of the service that worked well, identify barriers and bottlenecks in the process, incorporate parent feedback, and implement a number of service improvement strategies. The development of the final version of the “Difficult to Vaccinate” clinical pathway resulted in three key stages: initial referral, appointment booking, and vaccination (via either a distraction or sedation pathway). The entire pathway is described below and depicted in Figures 1, 2.

FIGURE 1.

Specialist Immunization Clinic pathway for “Difficult to vaccinate children”.

FIGURE 2.

Process Map from Intake to Appointment.

3.2.1. Initial referral

On receipt of a new referral, the clinic CNC calls families to obtain information regarding the medical, psychological, and developmental history of the child, history of attempts at vaccination in the community and the outcome of these, previous experience with sedation and the parents' expectations from the service. The CNC triages referrals considering factors such as impending travel requiring vaccination beforehand, and current difficulties faced by the family. The NSWISS team discusses the case, with a focus on the medical, psychological, developmental, and behavioral history of the child, and the outcome of previous attempts at vaccination. The team decides whether to attempt vaccination using relaxation and distraction techniques, or to use sedation.

3.2.2. Appointment booking

The CNC calls parents to discuss the planned approach and if relevant, provide some education and written materials via email, such as a fact sheet about procedural sedation and fasting times. They call families the day before the booking to ensure the child is well and does not have any new contraindications to the planned vaccines.

3.2.3. Vaccination

Children are vaccinated using either the distraction or sedation pathway, depending on their needs and the decision made by the NSWISS team during the initial referral stage.

Vaccination with distraction pathway

Families are admitted into the clinic. The child is reviewed, a history is taken, and the plan for the appointment is discussed with the parents. This is discussed out of earshot of the child, to minimize their anxiety. The clinic staff spend time talking to or playing with the child, to establish rapport. For distraction, the team uses a variety of techniques including toys, puzzles, and videos, singing, or conversation with the child about their interests. For relaxation, staff enlist the assistance of the parent to provide comfort, use breathing techniques, comfort objects such as soft toys, and staff ensure that only one person is speaking at a time, to maintain a calm atmosphere. The clinic staff administer multiple vaccines simultaneously where required. If the vaccination is successful, the child is observed in the clinic waiting room for 15 minutes for any immediate adverse events following immunization. Families are contacted 3 days after vaccination to enquire about any adverse events. The medical officer communicates the outcome of the appointment and the plan going forward to the general practitioner (GP). If the vaccination attempt was unsuccessful, the medical officer and CNC discuss the option of sedation with the family, which requires booking a separate appointment. Families who accept the sedation option are given a face mask to practice using at home, notified of their new appointment by phone, and provided with educational material about sedation and a plan for fasting times.

Vaccination with sedation pathway

The CNC meets the family at the main entrance to the hospital and guide them to the day stay unit. This allows the CNC to build rapport with the family and reduce their stress in navigating a new and confusing environment. Patients are clerically and medically admitted into the ward. A medical officer takes a history, examines the child, and ensures there are no contraindications to the specific vaccines that are being given. They ensure the child has appropriately fasted and taken any premedication that were required. Together with the CNC, they discuss with the parent which vaccine(s) should be prioritized, and the plan for sedation. The child is then familiarized with the sedation room, distraction techniques are used, and the parent is encouraged to sit/stand close to the child and provide ongoing physical comfort. The CNC then introduces the face mask and encourages the child and/or parent to hold it in place, before administering nitrous oxide. In some cases, midazolam is used in place of, or in addition to nitrous oxide. This is determined via clinician assessment on case‐by‐case basis. Once the child is sedated, vaccination is attempted. Where multiple vaccines are required, additional nursing staff are used so that multiple vaccines can be administered simultaneously. Parents are encouraged to provide continuous reassurance and comfort to the child. Following vaccination, children remain in the day unit for observation for 30 min to 2 h, depending on which method of sedation was used. During this time staff discuss a plan for follow‐up if required. If vaccination was successful, families are contacted 3 days after vaccination to enquire about any adverse events. Where follow‐up is required, families are notified of their appointment by phone. The medical officer communicates the outcome of the appointment and the plan going forward to the GP.

3.3. Follow‐up evaluation of clinical pathway

Qualitative analysis of interviews of six parents of children who had been seen at NSWISS following the implementation of the improved “Difficult to Vaccinate” clinical pathway generated 6 major themes and 10 subthemes. Parents did not provide any further suggestions in terms of further improvements. Concerns raised in the initial interviews were explored and not encountered in the follow‐up set of interviews. Whilst this could be related to sampling bias of the families, issues previously raised were reported to have resolved and saturation of themes were reached by the sixth interview. Parents were keen to advertise the service and wished the service was located closer to their residence. Table 4 presents these themes and subthemes.

TABLE 4.

Themes and subthemes from follow‐up parent interviews.

| Theme 1 | All parents were still very positive about their and their child's experience |

|---|---|

| Subthemes |

|

| Theme 2 | All parents had used some form of resource to prepare child mostly provided by team |

| Subthemes |

|

| Theme 3 | Child was pleased that procedure successful empowered to handle future vaccinations |

| Subthemes |

|

| Theme 4 | None of the parents had anything to suggest in terms of further improvements. |

| Theme 5 | Concerns raised in the previous interviews were explored and not encountered in this current set of interviews. |

| Theme 6 | Parent reluctance to return to GP or school for future vaccinations |

In the follow‐up focus group, staff reviewed the process map and discussed the plans for improvements from the previous session. They reflected on how they had performed as a team and if any of the discussed improvements were successfully implemented. Barriers and ongoing issues were also discussed. Detailed information regarding parent and staff categories and illustrative quotes are presented in Table S1.

4. DISCUSSION

This project describes a quality improvement activity using process mapping to develop a clinical care pathway for needle phobic children. Many of these children have comorbid intellectual or developmental disability, experience multiple hospital presentations, and are not up to date with immunizations. 1 Families were referred from areas well outside the hospital's usual catchment area, reflecting the lack of similar services in our city and lesser still from rural areas of Australia. 19 The children had also been significantly traumatized by previous repeated failed vaccination attempts with mainstream services becoming more paralyzed by their inefficacy. The children and young adults were under‐vaccinated and at risk of vaccine preventable diseases to themselves and their community. 1 In Australia, eligibility for certain welfare payments including childcare subsidization requires children to be up to date with immunizations; therefore, families of under‐vaccinated children may also be also financially impacted. 20 Additionally in some jurisdictions, such as New South Wales where the study was conducted, a child's admission to childcare or preschool is contingent on being fully vaccinated. 21 Traumatic experiences can also contribute to longer term healthcare avoidance. 22

Distraction techniques and conscious sedation are effective techniques to facilitate immunization in pediatric patients with anxiety disorders, needle phobia, developmental or behavioral disorders. 23 However, guidelines and protocols are lacking, and therefore, in our Specialist Immunization Clinic, we aimed to develop a more consistent management algorithm for these patients.

Process mapping provided a structured, reflexive, and iterative approach to making improvements using the quality improvement Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act cycle. 15 , 24 In addition, the use of parent and staff feedback provided a more holistic approach in ensuring that the adapted pathway truly met the needs of the patient population and improved staff self‐ agency and satisfaction aligned with experience based codesign methodologies. 25 , 26 Through the provision of appropriate information and support for the children and their parents, parents reported that this approach not only provided a much improved experience of the clinical pathway and vaccination process more broadly, but also brought families towards empowerment to cope with future health care visits for invasive procedures. This respects their rights to receive care that is as informed and stress‐free as possible. 27 , 28

Staff also felt that the “Difficult to Vaccinate” pathway had been a success overall and reported high levels of satisfaction. They also felt that there was an impetus to share adapted practices with the wider community through advice leaflets and customized information to build capacity of primary health services to be able to provide further catch‐up vaccinations. However, this also needs to be balanced with ensuring that the child and parent are appropriately accustomed to the strategies and preparation to achieve success once they are discharged back to the community. Issues regarding managing older adolescents above the age‐cut off for admission to the hospital, eligibility to access the service, and difficulties with adequate staffing remain challenges to overcome in future implementations of this clinical pathway.

Limitations to the study include the small sample size and the use of team member and parent reports only in the evaluation process. As this was a qualitative study based on a small subset of patients, the experiences reported by parents of the children were the primary measures used to gauge satisfaction. Unfortunately, data on the number of children successfully vaccinated using the “Difficult to Vaccinate” clinical pathway were not collected as part of this study, which would have added a valuable quantitative element to the findings. Additionally, increased triangulation of data could include the implementation of an ethnographic study to observe the interactions during a vaccination visit and eliciting feedback directly from children using developmentally appropriate strategies. Surveys to GPs and other primary care pediatricians providing care to many of these children should be explored in future research.

This reported clinical pathway and the process use to develop it have the potential to be utilized in additional contexts. As an example, from the findings of this study, one of the coauthors provided guidance to set up NSW Health facilities providing COVID‐19 vaccination for a systems‐based approach to assist vaccinations for adults and children who were difficult to vaccinate. There were specific clinics at local hospitals providing vaccination clinics for adults and at the children's hospital with children with intellectual and developmental disability.

5. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Patient satisfaction with the “Difficult to Vaccinate” clinical pathway following a process mapping quality improvement exercise was assessed through a series of semistructured interviews in the initial and post 14–16 months period. Parents reported better information provision and resources to prepare their child, many of the preparatory strategies were still maintained over time, staff communicated clearly, interacted well and were able to keep their patients calm enough for the successful completion of the vaccination. Parents also reported that children felt empowered by their positive experience to return for follow‐up vaccinations.

Team members were able to use patient and staff feedback to identify actionable strategies for improvement, which were then implemented. Team members were able to sustain the improvements and reported an increase in confidence in managing and supporting these children.

Incorporating process mapping, parent feedback and facilitated discussions in a focus group setting using motivational interview techniques in a PDSA framework was an effective way to evaluate service improvement and evaluation initiatives.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was secured for this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Sydney Children's Hospital QI review committee and deemed research ethics approval not required as QI project.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Patients were consented verbally during the interview.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIAL FROM OTHER SOURCES

None was used.

Supporting information

Table S1.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Gail Tomsic and Evelyn McLeod for their assistance in the quality improvement activities and A/Prof Natalie Silove and Dr Nicholas Wood for their approval and institutional support of the project.

Ong N, Brogan D, Lucien A, et al. The development and evaluation of a vaccination pathway for children with intellectual and developmental disability and needle fear. Paediatr Neonatal Pain. 2024;6:1‐9. doi: 10.1002/pne2.12103

REFERENCES

- 1. Emerson E, Robertson J, Baines S, Hatton C. Vaccine coverage among children with and without intellectual disabilities in the UK: cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Glasper EA. Optimising the Care of Children with intellectual disabilities in hospital. Compr Child Adolesc Nurs. 2017;40(2):63‐67. doi: 10.1080/24694193.2017.1309827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mimmo L, Harrison R, Hinchcliff R. Patient safety vulnerabilities for children with intellectual disability in hospital: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2018;2(1):e000201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oulton K, Gibson F, Carr L, et al. Mapping staff perspectives towards the delivery of hospital care for children and young people with and without learning disabilities in England: a mixed methods national study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):203. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2970-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O'Neill J, Newall F, Antolovich G, Lima S, Danchin M. Vaccination in people with disability: a review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(1):7‐15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taddio A, Chambers CT, Halperin SA, et al. Inadequate pain management during routine childhood immunizations: the nerve of it. Clin Ther. 2009;31:S152‐S167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taddio A, Ipp M, Thivakaran S, et al. Survey of the prevalence of immunization non‐compliance due to needle fears in children and adults. Vaccine. 2012;30(32):4807‐4812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng DR, Elia S, Perrett KP. Immunizations under sedation at a paediatric hospital in Melbourne, Australia from 2012–2016. Vaccine. 2018;36(25):3681‐3685. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deacon B, Abramowitz J. Fear of needles and vasovagal reactions among phlebotomy patients. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20(7):946‐960. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Orenius T, LicPsych, Säilä H, Mikola K, Ristolainen L. Fear of injections and needle phobia among children and adolescents: an overview of psychological, behavioral, and contextual factors. SAGE Open Nurs. 2018;4:2377960818759442. doi: 10.1177/2377960818759442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sokolowski CJ, Giovannitti JA, Boynes SG. Needle phobia: etiology, adverse consequences, and patient management. Dent Clin N Am. 2010;54(4):731‐744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schechter NL, Zempsky WT, Cohen LL, McGrath PJ, McMurtry CM, Bright NS. Pain reduction during pediatric immunizations: evidence‐based review and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):e1184‐e1198. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Willemsen H, Chowdhury U, Briscall L. Needle phobia in children: a discussion of aetiology and treatment options. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;7(4):609‐619. [Google Scholar]

- 14. SCHN CGU. Quality improvement activities: initiation and approval. Sydney Children's Hospitals Network 2015. https://www.schn.health.nsw.gov.au/_policies/pdf/2015‐9034.pdf

- 15. Magnuson S, Kras KR, Aleandro H, Rudes DS, Taxman FS. Using plan‐do‐study‐act and participatory action research to improve use of risk needs assessments. Corrections. 2020;5(1):44‐63. doi: 10.1080/23774657.2018.1555442 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Trebble TM, Hansi N, Hydes T, Smith MA, Baker M. Process mapping the patient journey: An introduction. BMJ. 2010;341:c4078. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ong N, Goff R, Eapen V, et al. Motivation for change in the health care of children with developmental disabilities: Pilot continuing professional development‐quality improvement project. J Paediatr Child Health. 2021;57(2):212–218. doi: 10.1111/jpc.15175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi‐disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hussain R, Tait K. Parental perceptions of information needs and service provision for children with developmental disabilities in rural Australia. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(18):1609‐1616. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.972586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance . No Jab no Play no Jab no Pay. 2022. https://www.ncirs.org.au/public/no‐jab‐no‐play‐no‐jab‐no‐pay

- 21. NSW Health . Questions and Answers about Vaccination Requirements for Child Care. 2022. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/immunisation/Pages/childcare_qa.aspx

- 22. Pate JT, Blount RL, Cohen LL, Smith AJ. Childhood medical experience and temperament as predictors of adult functioning in medical situations. Child Health Care. 1996;25(4):281‐298. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pascolo P, Peri F, Montico M, et al. Needle‐related pain and distress management during needle‐related procedures in children with and without intellectual disability. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177(12):1753‐1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Donnelly P, Kirk P. Use the PDSA model for effective change management. Educ Prim Care. 2015;26(4):279‐281. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2015.11494356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Donetto S, Tsianakas V, Robert G. Using Experience‐Based Co‐Design (EBCD) to Improve the Quality of Healthcare: Mapping where we Are Now and Establishing Future Directions. King's College London; 2014:5‐7. [Google Scholar]

- 26. The Kings Fund . Experience‐Based co‐Design Toolkit. 2013. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/ebcd

- 27. Bricher G. Children in the hospital: issues of power and vulnerability. Pediatr Nurs. 2000;26(3):277‐282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reed S, Glasper EA. Empowering children and young people and families in health care. A Textbook of Children's and Young People's Nursing‐E‐Book. 2021;431:1. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.