Abstract

Although sucrose is widely administered to hospitalized infants for single painful procedures, total sucrose volume during the entire neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) stay and associated adverse events are unknown. In a longitudinal observation study, we aimed to quantify and contextualize sucrose administration during the NICU stay. Specifically, we investigated the frequency, nature, and severity of painful procedures; proportion of procedures where neonates received sucrose; total volume of sucrose administered for painful procedures; and incidence and type of adverse events. Neonates <32 weeks gestational age at birth and <10 days of life were recruited from four Canadian tertiary NICUs. Daily chart reviews of documented painful procedures, sucrose administration, and any associated adverse events were undertaken. One hundred sixty‐eight neonates underwent a total of 9093 skin‐breaking procedures (mean 54.1 [±65.2] procedures/neonate or 1.1 [±0.9] procedures/day/neonate) during an average NICU stay of 45.9 (±31.4) days. Pain severity was recorded for 5399/9093 (59.4%) of the painful procedures; the majority (5051 [93.5%]) were heel lances of moderate pain intensity. Sucrose was administered for 7839/9093 (86.2%) of painful procedures. The total average sucrose volume was 5.5 (±5.4) mL/neonate or 0.11 (±0.08) mL/neonate/day. Infants experienced an average of 7.9 (±12.7) minor adverse events associated with pain and/or sucrose administration that resolved without intervention. The total number of painful procedures, sucrose volume, and incidence of adverse events throughout the NICU stay were described addressing an important knowledge gap in neonatal pain. These data provide a baseline for examining the association between total sucrose volume during NICU stay and research on longer‐term behavioral and neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Keywords: analgesia, infant, intensive care units, neonatal, newborn, pain, sucrose

1. INTRODUCTION

Approximately 15 million preterm infants are born annually, accounting for 11% of all births. 1 Preterm infants are commonly admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for several weeks or months where they undergo multiple painful skin‐breaking (SB) and non‐SB procedures 2 , 3 , 4 for diagnostic and treatment purposes. Inadequately treated procedural pain while in the NICU coincides with a critical period of brain development. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Syntheses of research on the effectiveness of sweet solutions, alone or combined with non‐nutritive sucking (NNS) 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 and other nonpharmacologic strategies, 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 for the prevention and treatment of procedural pain in infants, have been undertaken. Yet, implementation of this knowledge is often inadequate and treatment is suboptimal. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 Evidence‐informed guidelines to treat procedural pain do not necessarily guarantee high‐quality pain practices. 22 , 23 , 24

Most randomized controlled trials (RCT) summarized in systematic reviews 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 focus on sucrose effectiveness during single painful procedures, with little information on sucrose administration practices or volumes during the full NICU stay and/or immediate and cumulative adverse events. We aimed to describe, for the infant's full NICU stay, the (a) frequency, nature, and severity of painful procedures, (b) proportion of all procedures where neonates received sucrose, (c) total volume of sucrose administered for painful procedures, and (d) type and incidence of adverse events associated with pain and sucrose administration.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and settings

A prospective longitudinal observational study was undertaken between March 2016 and October 2019 in four level III university‐affiliated NICUs in central and eastern Canada.

2.2. Participants

Infants who were hospitalized in the NICU, <32 weeks gestational age (GA) at birth and <10 days of life (DOL) were eligible for inclusion. Infants were excluded if they had contraindications for sucrose administration.

2.3. Procedures for data collection

Following Research Ethics Board (REB) approval, parents of eligible infants were approached by a research nurse who explained the study and obtained written consent. Bedside nurses, caring for the infant, were asked to administer the minimally effective dose of 0.12 mL (three drops) of 24% sucrose 25 with all SB and non‐SB procedures. They were also asked to document the type of procedure, whether sucrose was accompanied by NNS and/or any other nonpharmacologic interventions, and any associated adverse events. The research nurse at each site reconciled the sucrose doses administered for all infants every 24 h. Sucrose was administered 2 min prior to the procedure onto the anterior portion of the tongue. A pacifier was offered if the infant could hold it in their mouth independently. Sucrose rescue doses (0.12 mL) were administered at the nurse's discretion if the infant's pain response was severe and/or the procedure was lengthy. No maximum procedural, daily, or cumulative sucrose dose limit was established.

Painful procedures were classified according to pain severity using the system developed by Laudiano‐Dray et al., 26 which includes both SB and non‐SB procedures. Estimates of pain severity were created by averaging neonatal scores derived from the literature and performing a hierarchical cluster analysis, resulting in five categories: mild, mild to moderate, moderate, severe, and extremely severe. Although gastric tube insertion and naso/oropharyngeal suctioning are included in this inventory, sucrose was not routinely administered for these non‐SB procedures at any of the participating sites and therefore were not reported as painful procedures in this study.

Infants were monitored by the bedside nurse for immediate adverse events related to sucrose administration (e.g., choking/gagging), and adverse events related to pain (e.g., tachycardia, bradycardia, oxygen desaturations, and apnea). 27 , 28 Adverse events and any required intervention were recorded.

Given there was a noted delay in DOL in recruiting neonates into the study at birth, we also reviewed the medical record in an attempt to determine a comprehensive total number of painful procedures and sucrose doses prior to study enrollment. These data did not specify the nature of the painful procedures or the amount of sucrose that was administered (only yes or no to question about administration). Given these limitations, these data are reported separately from postenrollment data in this paper.

Data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools 29 , 30 hosted at the institution of the PI. Data monitoring and logistic checks were performed regularly during the data collection.

2.4. Sample size

Although there is no precise formula for calculating sample size for a longitudinal study, we estimated that approximately 40 infants per site would adequately represent pain practices at the site and meet the study goals in this study design. We also attempted to oversample by 10% to account for loss to follow‐up. A total of 172 infants were recruited with 168 available for analyses. There were 7711 patient days of assessment following recruitment. These data represent one of the largest observations to date of sucrose administration for infant pain during the full NICU stay.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The frequency and type of painful procedures and the amount of sucrose administered across the 168 participants were summarized using descriptive statistics. Outcomes were compared across sites using chi‐squared tests of association for categorical data and ANOVA for continuous data. Analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4.

3. RESULTS

The demographic characteristics of the participating 168 infants are included in Table 1. There were significant differences between study sites; infants from one site were of lower birth weight (BW) and higher Scores for Neonatal Acute Physiology with Perinatal Extension‐II (SNAPPE‐II). In addition, there were significant differences in the DOL at study enrollment and the number of painful procedures and sucrose doses administered prior to study enrollment across sites.

TABLE 1.

Infant characteristics (n = 168).

| Characteristics | Overall | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of infants | 168 | 52 | 72 | 23 | 21 | |

| GA at birth b | 28.4 (2.3) | 28.0 (2.3) | 29.1 (2.2) | 26.9 (1.8) | 29.0 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| BW b | 1104.0 (380.9) | 1048.6 (304.9) | 1194.1 (333.5) | 821.0 (376.0) | 1239.9 (522.4) | 0.005 |

| Sex a | ||||||

| F | 71 (42.5) | 27 (52.9) | 32 (44.4) | 6 (26.1) | 6 (28.6) | 0.086 |

| M | 96 (57.5) | 24 (47.1) | 40 (55.6) | 17 (73.9) | 15 (71.4) | |

| SNAPPE‐II b | 20.2 (19.3) | 23.5 (20.8) | 17.6 (18.8) | 27.6 (19.2) | 11.7 (12.4) | 0.026 |

| DOL b | 5.89 (2.8) | 3.96 (2.5) | 6.13 (1.7) | 7.68 (3.2) | 8.00 (3.01) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BW, birth weight in grams; DOL, days of life; F, female; GA, gestational age in weeks; M, male; SNAPPE‐II, score for neonatal acute physiology perinatal extension‐II.

Values expressed as N (%)

Values expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD).

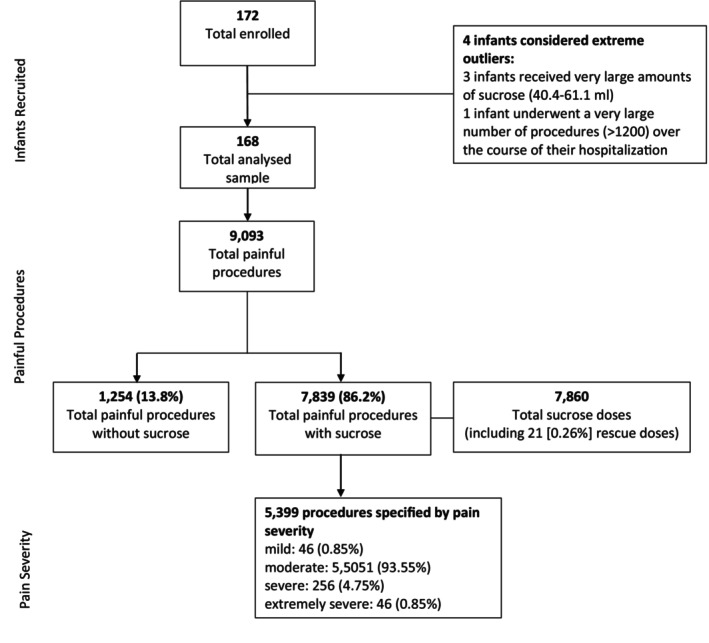

The frequency and types of painful procedures, proportion of infants who received sucrose, and pain severity are summarized in Figure 1 and Tables 2 and 3.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram.

TABLE 2.

Frequency of painful procedures (n = 168).

| Painful procedures | Overall | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of procedures | 9093 | 2664 | 3370 | 1820 | 1239 | ‐ |

| NICU days assessed a | 45.9 (31.4) | 43.6 (34.5) | 52.7 (26.8) | 46.2 (34.9) | 27.9 (28.1) | 0.013 |

| Procedures per infant a | 54.1 (65.2) | 51.2 (47.7) | 46.8 (46.5) | 79.1 (62.0) | 59.0 (129.7) | 0.210 |

| Procedures per infant per day a | 1.1 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.7) | 0.8 (0.6) | 1.9 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Min: 0.0 | Min: 0.0 | Min: 0.2 | Min: 0.3 | Min: 0.6 | ||

| Max 6.4 | Max: 4.5 | Max: 3.2 | Max: 5.5 | Max: 6.4 |

Values expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD).

TABLE 3.

Frequency of painful procedures documented prior to study enrollment (n = 160).

| Painful procedures | Overall | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of procedures | 4275 | 649 | 1362 | 1752 | 512 | ‐ |

| NICU days assessed prior a | 5.9 (2.8) | 4.0 (2.5) | 6.1 (1.7) | 7.7 (3.2) | 8.0 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Procedures per infant a | 26.2 (28.8) | 13.8 (9.9) | 18.9 (16.9) | 76.2 (41.2) | 24.4 (14.0) | <0.001 |

| Procedures per infant per day a | 4.6 (4.1) | 4.7 (3.1) | 3.3 (3.4) | 9.8 (5.6) | 3.21 (1.4) | <0.001 |

Values expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD).

The frequency by type of painful procedure during the NICU stay study period is described in Tables 2 and 3. Where recorded, additional data for painful procedures conducted on study infants during 1373 days prior to the study enrollment were collected (Table 3).

Sucrose was administered for 7839/9093 (86%) of painful procedures. A total of 7860 sucrose doses (including 21 recorded rescue doses) were offered to the 168 infants in the study (Figure 1; Table 4). Data on sucrose administration on the DOL prior to study enrollment were available for 160/168 infants and are displayed in Table 5.

TABLE 4.

Frequency and volume of sucrose administration with painful procedures (n = 168).

| Sucrose administration | Overall | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total procedures/infant with sucrose a | 45.4 (52.4) | 49.2 (62.9) | 44.2 (43.5) | 55.0 (51.3) | 29.7 (53.3) | 0.400 |

| Total procedures/infant without sucrose a | 8.7 (35.4) | 2.1 (34.4) | 2.6 (3.6) | 24.2 (20.6) | 29.3 (77.1) | 0.001 |

| Total average sucrose volume/infant/NICU stay (mL) a | 5.5 (5.4) | 5.1 (4.2) | 5.8 (5.6) | 6.6 (6.3) | 4.0 (6.2) | 0.420 |

| Average sucrose volume/infant/day assessed (mL) a | 0.11 (0.08) | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.10 (0.07) | 0.14 (0.11) | 0.13 (0.10) | 0.110 |

Values expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD).

TABLE 5.

Frequency of sucrose administration documented with painful procedures prior to study enrollment.

| Sucrose administration prior to study enrollment | Overall | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total doses sucrose delivered | 1125 (n = 160) | 207 (n = 45) | 682 (n = 71) | 145 (n = 23) | 91 (n = 21) | ‐ |

| Average doses sucrose/infant a | 7.0 (5.7) (n = 160) | 4.6 (4.2) (n = 45) | 9.6 (5.3) (n = 71) | 6.3 (7.3) (n = 23) | 4.3 (3.7) (n = 21) | <0.001 |

| Average doses sucrose/infant/day a | 1.3 (1.1) (n = 156) | 1.4 (1.3) (n = 44) | 1.7 (1.0) (n = 71) | 0.8 (0.7) (n = 21) | 0.6 (0.7) (n = 20) | 0.085 |

Values expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD).

The types of procedures performed were recorded by the bedside nurse for 5399/9093 (59.4%) of the total number of procedures in the study data (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Frequency and nature of painful procedures by pain severity a (n = 168).

| Pain severity | Overall [N (%)] | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild to moderate | 46 (0.85%) | 11 | 29 | 6 | 0 |

| Urinary catheterizations | 46 | 11 | 29 | 6 | 0 |

| Moderate | 5051 (93.55%) | 1035 | 2757 | 757 | 502 |

| Capillary blood collection (heel lance) | 2923 | 528 | 1481 | 536 | 378 |

| Tape removal | 577 | 140 | 322 | 98 | 17 |

| Eye exam b | 487 | 67 | 384 | 21 | 15 |

| Peripheral IV line | 468 | 147 | 209 | 77 | 35 |

| Venous blood collection | 206 | 14 | 147 | 25 | 20 |

| Subcutaneous injection | 172 | 1 | 138 | 0 | 33 |

| Blood collection (no specification) | 129 | 127 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ostomy bag change b | 72 | 0 | 69 | 0 | 3 |

| Injection no specification | 14 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Vascular attempts no specification | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Severe | 256 (4.75%) | 59 | 145 | 35 | 17 |

| Long lines/peripherally inserted central catheter | 98 | 21 | 66 | 3 | 8 |

| Intramuscular injection | 79 | 11 | 41 | 25 | 2 |

| Arterial blood collection | 39 | 21 | 11 | 7 | 0 |

| Peripheral arterial line | 38 | 4 | 27 | 0 | 7 |

| Bladder tap | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Extremely severe | 46 (0.85%) | 15 | 25 | 2 | 4 |

| Lumbar puncture | 45 | 15 | 25 | 2 | 3 |

| Chest tube insertion or removal | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 5399 (100%) | 1120 | 2956 | 800 | 523 |

Pain severity classified as described by Laudiano‐Dray et al. (2020). 26

Although eye examinations and ostomy bag change do not usually cause skin breaking, these procedures are invasive and stressful so were included in the study.

The presence or absence of adverse events was noted for 5404 of the 7860 sucrose doses administered. No adverse event data (present or absent) were recorded for 2435 procedures. There were 7.9 events associated with sucrose administration and/or pain per infant during the entire NICU stay. All adverse events were noted to resolve spontaneously without any required intervention (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Adverse events associated with sucrose administration and pain during the NICU stay (n = 168).

| Adverse events | Overall | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apnea a | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.7 (1.3) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.002 |

| Bradycardia a | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.8 (1.4) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.7 (1.1) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.024 |

| Choking/Gagging a | 0.5 (1.2) | 0.8 (1.3) | 0.2 (0.7) | 1.00 (2.0) | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.007 |

| Tachycardia a | 2.6 (4.8) | 2.2 (4.6) | 2.0 (4.7) | 5.0 (6.2) | 2.5 (3.5) | 0.079 |

| O2 Desaturation a | 4.2 (8.4) | 5.3 (7.7) | 3.0 (7.6) | 7.2 (12.3) | 2.2 (6.3) | 0.091 |

| Total/infant a | 7.9 (12.7) | 9.3 (11.8) | 5.6 (11.2) | 14.5 (19.2) | 5.5 (8.0) | 0.017 |

Values expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) per infant.

4. DISCUSSION

Neonates experienced an average of 54.1 procedures during their NICU stay or 1.1 procedures/day; the majority of procedures were heel lances that were classified as moderate pain intensity. Sucrose was administered for 86.2% of the procedures. The total documented mean volume of sucrose per infant was 5.5 mL or approximately 0.11 mL/day. Infants, on average, experienced 7.95 adverse events associated with sucrose administration or pain related to the painful procedure. All adverse events resolved spontaneously without healthcare intervention.

Differences across sites were observed in terms of infants' characteristics, the number of painful procedures, and sucrose doses. In site 3, for example, infants were born at lower gestational age, had lower birth weight, and higher risk of mortality as demonstrated by the SNAPPE‐II scores. These factors were associated with a higher number of painful procedures and sucrose doses administered per infant in this particular site.

One painful procedure/day of NICU admission, on average, is a significant decrease in the incidence of painful procedures from a systematic review by Cruz et al. 21 who reported an average of 7.5–17.3 painful procedures/day/neonate, including SB and potentially SB procedures. The definition of non‐SB procedures may vary, most notably suctioning and tube insertions, which some may not consider painful. If these procedures are included in totals, the number of procedures increases substantially, thus accounting at least partially for the difference in frequency of reported painful events. Other studies reporting on the epidemiology of pain in NICUs present results that are more consistent with our findings. In a Canadian study of 242 neonates, 10 469 SB and potentially SB procedures were documented, with a median of 43 procedures per hospital stay or an average of 1.46 procedures/infant/day. 31 In two NICUs in Brazil, 140 infants experienced over 21 000 stressful and painful procedures, with 3160 (15%) considered as invasive procedures (e.g., heel lances, venipunctures, tube insertions, and removals). Their daily estimate was 1.0 painful procedure/day/infant for the hospital stay. 4 However, the time interval when data are collected or the number of days included in these estimates may also vary. Despite the variability of the frequency of procedures reported and time intervals for data collection considered, recent publications seem to indicate an overall downward trend in the daily frequency of painful procedures. The need for further information on the nature and frequency of these procedures within the context of full NICU stay is warranted.

The burden of pain for hospitalized infants is typically determined by global estimates of the frequency of painful procedures either by DOL or over a defined period of time. However, frequency does not necessarily equate with the severity of pain or burden of pain associated with repeated painful events or attempts to successfully complete the procedure at a given point in time. Recently, Laudiano‐Dray et al. 26 determined and validated estimates of procedural pain severity, based on pain reactivity scores used to quantify an individual neonate's NICU pain burden. While this platform improves the understanding of the severity of procedural pain, it may still need further refinement. For example, Disher et al., 32 from a meta‐analysis, suggested that eye examination is associated with severe pain while Laudiano‐Dray et al. 26 reported this procedure as moderate pain. Adding information on procedural pain intensity and burden of pain in epidemiological studies in neonates can contribute to an enhanced understanding of the immediate and repeated pain and its consequences.

The majority of painful procedures in this study were associated with moderate acute pain (e.g., heel lance and venipuncture) where treatment with sucrose had been shown in many studies and systematic reviews to be effective and appropriate. Rescue doses were administered in a small proportion (0.26%) of procedures, indicating the importance of careful assessment of pain throughout the procedure. Of the procedures documented, 86.2% were treated using sucrose. Data from a subset of 5399 babies on the type of procedure associated with sucrose administration or whether complementary NNS were also explored. NNS has been shown, in a recent systematic review, to complement sucrose resulting in lower pain intensity outcomes. 10 Using this combination of strategies to reduce pain during the entire NICU stay and their effect of outcomes requires further investigation.

The average total dose of sucrose of 5.5 mL during the full NICU stay or 0.11 mL per infant per day was consistent with the recommended minimally effective dose. 25 There is high variability in repeated sucrose doses reported in published papers, ranging from 0.1 to 2 mL per dose or from 0.2 to 0.5 mL/kg of sucrose per dose. 33 There is also a general lack of recorded detail on the total amount of sucrose administered for preterm infants during an entire NICU stay. In this study, there were limited data on the volume of sucrose administered on DOL prior to study enrollment, and more complete sucrose volumes for the full NICU stay were not available. Considering the minimal dose of sucrose administered was relatively standard in the participating NICUs, we do not anticipate that these volumes would have increased substantially from the study protocol. However, the use of antenatal recruitment strategies to ensure the entry of the infant into the study from the first day of life should be investigated.

Concerns have been posed on the relationship between sugar consumption and dopamine and/or acetylcholine release, and opioid stimulation and its effects on related brain structures and functions. 34 Tremblay et al. 35 observed widespread long‐term alterations in adult white and gray matter brain volumes in mice repeatedly exposed to sucrose in the first week of life. Nuseir et al. 36 , 37 described the protective effects of sucrose on short and long‐term memory in mice, whereas Ranger et al. 38 found memory in adult mice was poorer, irrespective of sucrose treatment for repeated procedural pain. In addition, Ramírez‐Contreras et al. 39 suggested repeated sucrose administered to mice in early life altered growth and liver methionine and choline metabolism in adulthood. As animals were randomized into different treatment groups in most of these preclinical studies, their results suggest sucrose may affect metabolism, liver growth, and neurodevelopment. 35 , 38 , 39 However, an important limitation is that there is no control of nutrition intake, which might interfere with the total amount of sugar consumption.

There have been only a few studies on human neonates, documenting the administration of sucrose prior to single heel lances 40 and prior to repeated painful procedures from 3rd to 7th day following birth 41 that resulted in higher oxidative stress and energetic demand in comparison with placebo and glucose. Johnston et al. 42 found that higher amounts of sucrose predicted poorer neurobehavioral development measured by the Neuro‐Biological Risk Score (NBRS 43 ) for preterm infants (<31 weeks of GA) who received 0.1 mL of sucrose for every invasive procedure performed during a 7‐day period. Infants who received ≤10 doses of sucrose/day were at lower risk for poorer neurodevelopment measured by the Neurobehavioral Assessment of the Preterm Infant (NAPI 44 , 45 ) at 32, 36, and 40 weeks GA. Stevens et al. 28 compared the effects of sucrose and pacifier, water and pacifier, and standard care administered prior to all painful procedures in the NICU stay during the first 28 DOL. There were no differences in NBRS scores across the three study groups at 28 days of age. Banga et al. 46 compared the effects of 0.5 mL of 24% sucrose and water, administered to all painful procedures performed in the first 7 DOL of 93 infants, and found no differences on NAPI scores at 40 weeks of corrected GA. Finally, Campbell‐Yeo et al. 47 reported no differences in NAPI scores for preterm infants (<37 weeks of GA) assessed at 32 and 36 weeks of corrected GA who received sucrose, skin‐to‐skin care, or sucrose combined with skin‐to‐skin care for all painful procedures performed during the entire hospitalization. We found no studies examining longer‐term neurodevelopment related to total sucrose volume for the NICU stay beyond the neonatal period, thus identifying an important knowledge gap to be addressed.

The occurrence of adverse events associated with sucrose administration has been reported as very low, with a high proportion of minor, self‐resolved adverse events and no major events. 10 Desaturation was the most commonly reported adverse event in this study and may be associated with the clinical characteristics of the included infants (i.e., prematurity) when under stress due to handling or experiencing pain. Changes in heart rate were also commonly reported. Although tachycardia is an indicator of neonatal pain, it has also been described in association with the administration of sweet‐tasting solutions. 48 Thus, it is challenging to determine whether increased heart rate is related to the infant's pain response, the administration of sucrose, or both.

5. LIMITATIONS

The current study was conducted in four Level 3 NICUs with a strong focus on pain prevention and management within a highly resourced country, which could limit the generalizability of our findings. DOL at study enrollment were greater than anticipated, as was the imprecise reporting of painful procedures and sucrose administration prior to study enrollment; both could have influenced the total frequency of painful procedures and sucrose administered. However, even if we were to include procedures prior to enrolment of infants in the study, the increase in the daily average would only be approximately 0.25 procedures, which does not change the total number significantly.

Imprecise and incomplete documentation about SB and non‐SB painful procedures and treatment with sucrose and nonpharmacologic interventions such as NNS in medical records is a common issue that precluded further evaluation of data in relation to pain severity. Nursing documentation does not always accurately reflect practice 49 and thus has the potential to underestimate the frequency of different types of procedures performed in the NICUs. However, direct observation may inhibit the comfort and usual practices of bedside nurses. Future research should consider alternative data collection methods (e.g., using continuous video) to compare to nursing documentation to account for the severity of procedural pain for individual or repeated events rather than solely relying on frequency.

6. CONCLUSION

Few studies have reported detailed information on the frequency and type of painful procedures, total volume of sucrose administered, and associated adverse events of painful procedures during the full NICU stay. In this study, there were fewer painful procedures performed daily and in total in preterm hospitalized infants compared with some previous studies and the majority were of moderate severity. The total and daily volumes of sucrose for the full NICU stay were consistent with the number of painful procedures and the minimally effective recommended dose of sucrose. The adverse events were characterized as minor and self‐resolving. These data provide a baseline for further examination of how total volumes of sucrose administered for repeated procedures of predominantly moderate pain intensity are associated with immediate adverse events and longer‐term outcomes.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr Bueno contributed to data analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Drs Gibbins, Harrison, Campbell‐Yeo, Ms McNair, and Ms Riahi contributed to the conceptualization and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. Drs Ballantyne, Estabrooks, Squires, Synnes, Taddio, and Yamada critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. Mr Victor planned and carried out the data analyses in collaboration with Drs Bueno and Stevens. Dr Stevens conceptualized and designed the study, obtained study funds, oversaw data collection and analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the final manuscript submitted, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)—MOP‐126167. The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by SickKids Research Ethics Board (REB), approval number 1000051066. Written consent was obtained from parents of enrolled infants following a face‐to‐face verbal explanation of the study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to Dr Megha Rao for the assistance with literature searches and review, and with formatting early versions of this work.

Bueno M, Ballantyne M, Campbell‐Yeo M, et al. A longitudinal observational study on the epidemiology of painful procedures and sucrose administration in hospitalized preterm neonates. Paediatr Neonatal Pain. 2024;6:10‐18. doi: 10.1002/pne2.12114

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author (BS) upon reasonable request and with a valid data‐sharing agreement.

REFERENCES

- 1. Harrison M, Goldenberg R. Global burden of prematurity. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;21(2):74‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cong X, Wu J, Vittner D, et al. The impact of cumulative pain/stress on neurobehavioral development of preterm infants in the NICU. Early Hum Dev. 2017;108:9‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McNair C, Campbell‐Yeo M, Johnston C, Taddio A. Nonpharmacologic management of pain during common needle puncture procedures in infants: current research evidence and practical considerations: an update. Clin Perinatol. 2019;46(4):709‐730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramos M, Korki de Candido L, Costa T, et al. Painful procedures and analgesia in hospitalized newborns: a prospective longitudinal study. J Neonatal Nurs. 2019;25(1):26‐31. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Duerden E, Grunau R, Guo T, et al. Early procedural pain is associated with regionally specific alterations in thalamic development in preterm neonates. J Neurosci Res. 2018;38(4):878‐886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fumagalli M, Provenzi L, de Carli P, et al. From early stress to 12 month development in very preterm infants: preliminary findings on epigenetic mechanisms and brain. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0190602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Williams M, Lascelles B. Early neonatal pain—a review of clinical and experimental implications on painful conditions later in life. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moultrie F, Slater R, Hartley C. Improving the treatment of infant pain. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2017;11(2):112‐117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stevens B, Yamada J, Ohlsson A, Haliburton S, Shorkey A. Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;7(7):CD001069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li Q, Tan X, Li X, et al. Efficacy and safety of combined oral sucrose and nonnutritive sucking in pain management for infants: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5):e0268033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bueno M, Stevens B, de Camargo P, Toma E, Krebs V, Kimura A. Breast milk and glucose for pain relief in preterm infants: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):664‐670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harrison D, Larocque C, Bueno M, et al. Sweet solutions to reduce procedural pain in neonates: a meta‐analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20160955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang R, Xie R, Wen S, et al. Sweet solutions for analgesia in neonates in China: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Can J Nurs Res. 2019;51(2):116‐127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shah P, Herbozo C, Aliwalas L, Shah V. Breastfeeding or breast milk for procedural pain in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD004950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pillai Riddell R, Racine N, Gennis H, et al. Non‐pharmacological management of infant and young child procedural pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(12):CD006275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Benoit B, Martin‐Misener R, Latimer M, Campbell‐Yeo M. Breast‐feeding analgesia in infants: an update on the current state of evidence. J Perinat Neonat Nurs. 2017;31(2):145‐159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnston C, Campbell‐Yeo M, Disher T, et al. Skin‐to‐skin care for procedural pain in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2(2):CD008435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shomaker K, Dutton S, Mark M. Pain prevalence and treatment patterns in a US children's hospital. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(7):363‐370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Courtois E, Droutman S, Magny J, et al. Epidemiology and neonatal pain management of heelsticks in intensive care units: EPIPPAIN 2, a prospective observational study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;59:79‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Courtois E, Cimerman P, Dubuche V, et al. The burden of venipuncture pain in neonatal intensive care units: EPIPPAIN 2, a prospective observational study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;57:48‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cruz M, Fernandes A, Oliveira C. Epidemiology of painful procedures performed in neonates: a systematic review of observational studies. Eur J Pain. 2015;20(4):489‐498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stevens B, Gastaldo D, Gisore P. Procedural pain in neonatal units in Kenya. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99(6):F464‐F467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Friedrichsdorf S, Goubert L. Pediatric pain treatment and prevention for hospitalized children. Pain Rep. 2019;5(1):e804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eccleston C, Fisher E, Howard R, et al. Delivering transformative action in paediatric pain: a lancet child & adolescent health commission. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(1):47‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stevens B, Yamada J, Campbell‐Yeo M, et al. The minimally effective dose of sucrose for procedural pain relief in neonates: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Laudiano‐Dray M, Riddell R, Jones L, et al. Quantification of neonatal procedural pain severity: a platform for estimating total pain burden in individual infants. Pain. 2020;161(6):1270‐1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gibbins S, Stevens B, Hodnett E, Pinelli J, Ohlsson A, Darlington G. Efficacy and safety of sucrose for procedural pain relief in preterm and term neonates. Nurs Res. 2002;51(6):375‐382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stevens B, Yamada J, Beyene J, et al. Consistent management of repeated procedural pain with sucrose in preterm neonates: is it effective and safe for repeated use over time? Clin J Pain. 2005;21(6):543‐548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harris P, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde J. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377‐381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harris P, Taylor R, Minor B, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Orovec A, Disher T, Caddell K, Campbell‐Yeo M. Assessment and management of procedural pain during the entire neonatal intensive care unit hospitalization. Pain Manag Nurs. 2019;20(5):503‐511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Disher T, Cameron C, Mitra S, Cathcart K, Campbell‐Yeo M. Pain relieving interventions for retinopathy of prematurity: a meta‐analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20180401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gao H, Gao H, Xu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of repeated oral sucrose for repeated procedural pain in neonates: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;62:118‐125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Holsti L, Grunau R. Considerations for using sucrose to reduce procedural pain in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):1042‐1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tremblay S, Ranger M, Chau CMY, et al. Repeated exposure to sucrose for procedural pain in mouse pups leads to long‐term widespread brain alterations. Pain. 2017;158(8):1586‐1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nuseir K, Alzoubi K, Alabwaini J, Khabour OF, Kassab M. Sucrose‐induced analgesia during early life modulates adulthood learning and memory formation. Physiol Behav. 2015;145:84‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nuseir K, Alzoubi K, Alhusban A, Bawaane A, Al‐Azzani M, Khabour O. Sucrose and naltrexone prevent increased pain sensitivity and impaired long‐term memory induced by repetitive neonatal noxious stimulation: role of BDNF and β‐endorphin. Physiol Behav. 2017;179:213‐219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ranger M, Tremblay S, Chau C, Holsti L, Grunau R, Goldowitz D. Adverse behavioral changes in adult mice following neonatal repeated exposure to pain and sucrose. Front Psychol. 2019;9:2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ramírez‐Contreras CY, Mehran AE, Salehzadeh M, et al. Sex‐specific effects of neonatal oral sucrose treatment on growth and liver choline and glucocorticoid metabolism in adulthood. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2021;321(5):R802‐R811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Asmerom Y, Slater L, Boskovic D, et al. Oral sucrose for heel lance increases adenosine triphosphate use and oxidating stress in preterm neonates. J Pediatr. 2013;163(1):29‐35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Angeles D, Boskovic D, Deming D, et al. A pilot study on the biochemical effects of repeated administration of 24% oral sucrose vs. 30% oral dextrose on urinary markers of adenosine triphosphate degradation. J Perinatol. 2021;41(12):2761‐2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Johnston C, Filion F, Snider L, et al. Routine sucrose analgesia during the first week of life in neonates younger than 31 weeks' postconceptional age. Pediatrics. 2002;110(3):523‐528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brazy JE, Eckerman CO, Oehler JM, Goldstein RF, O'Rand AM. Nursery neurobiologic risk score: important factors in predicting outcome in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 1991;118:783‐792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Korner AF, Kraemer HC, Reade EP, Forrest T, Dimiceli S, Thom VA. A methodological approach to developing an assessment procedure for testing the neurobehavioral maturity of preterm infants. Child Dev. 1987;58:1478‐1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Korner AF, Constantinou J, Dimiceli S, Brown BW Jr, Thom VA. Establishing the reliability and developmental validity of a neurobehavioral assessment for preterm infants: a methodological process. Child Dev. 1991;62(5):1200‐1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Banga S, Datta V, Rehan H, Bhakhri B. Effect of sucrose analgesia, for repeated painful procedures, on short‐term neurobehavioral outcome of preterm neonates: a randomized controlled trial. J Trop Pediatr. 2016;62(2):101‐106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Campbell‐Yeo M, Johnston C, Benoit B, et al. Sustained efficacy of kangaroo care for repeated painful procedures over neonatal intensive care unit hospitalization: a single‐blind randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2019;160(11):2580‐2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gradin M, Schollin J. The role of endogenous opioids in mediating pain reduction by orally administered glucose among newborns. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):1004‐1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang N, Hailey D, Yu P. Quality of nursing documentation and approaches to its evaluation: a mixed‐method systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(9):1858‐1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author (BS) upon reasonable request and with a valid data‐sharing agreement.