Abstract

Routinely collected and linked healthcare administrative datasets could be used to monitor mortality among people with hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV). This study aimed to evaluate the concordance in records of liver‐related mortality among people with an HBV or HCV notification, between data on hospitalization for end‐stage liver disease (ESLD) and death certificates. In New South Wales, Australia, HBV and HCV notifications (1993–2017) were linked to hospital admissions (2001–2018), all‐cause mortality (1993–2018) and cause‐specific mortality (1993–2016) datasets. Hospitalization for ESLD was defined as a first‐time hospital admission due to decompensated cirrhosis (DC) or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Consistency of liver death definition of mortality following hospitalization for ESLD was compared with two death certificate‐based definitions of liver deaths coded among primary and secondary cause‐specific mortality data, including ESLD‐related (deaths due to DC and HCC) and all‐liver deaths (ESLD‐related and other liver‐related causes). Of 63,292 and 107,430 individuals with an HBV and HCV notification, there were 4478 (2.6%) post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths, 5572 (3.3%) death certificate liver disease deaths and 2910 (1.7%) death certificate ESLD deaths. Between 2001 and 2016, among HBV post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths (n = 891), 63% (562) had death certificate ESLD recorded, and 83% (741) had death certificate liver disease recorded. Between 2001 and 2016, among HCV post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths (n = 3587), 58% (2082) had death certificate ESLD recorded, and 87% (3135) had death certificate liver disease recorded. At least one‐third of death certificates with DC and HCC as cause of death had no mention of HBV, HCV or viral hepatitis. Our study identified limitations in estimating and tracking HBV and HCV liver disease mortality using death certificate‐based data only. The optimum data for this purpose is either ESLD hospitalisations with vital status information or a combination of these with cause‐specific death certificate data.

Keywords: cause‐specific ESLD‐related, cause‐specific liver disease‐related, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, mortality trends

Abbreviations

- APDC

Admitted Patient Data Collection

- AUD

alcohol‐use disorder

- COD URF

Cause of Death Unit Record File

- DC

decompensated cirrhosis

- ESLD

end‐stage liver disease

- HBV

hepatitis B

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C

- ICD‐10

International Classification of Diseases

- NCIMS

Notifiable Conditions Information Management System

- NHR

National HIV Registry

- PDC

perinatal data collection

- RBDM

Registry of Births, Deaths, and Marriages

1. INTRODUCTION

Healthcare administrative datasets are repositories of routinely collected data that have become a powerful tool for producing new insights into health status and practical disease prevention opportunities. 1 In recent years, health researchers and policymakers have increasingly used administrative health databases for disease surveillance, assessment of health resource utilization and evaluation of health outcomes. 1 , 2 , 3 Depending on available infrastructure and resources, linked or unlinked administrative datasets provide a promising avenue for evidence‐based policy development and practice; however, limitations such as lack of clinical information must be adequately addressed in research methods. 4 , 5

Hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV) are chronic viral infections and leading causes of liver‐related death and disability worldwide. 6 HBV and HCV liver deaths are primarily due to end‐stage liver disease (ESLD), including decompensated cirrhosis (DC) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). 7 , 8 In the highly effective antiviral therapies era, 8 , 9 linking administrative datasets provides information and the capacity to monitor liver‐related deaths and enhances surveillance efforts toward the World Health Organization (WHO) 2030 viral hepatitis elimination targets. 10 Initial WHO 2030 targets for HBV and HCV mortality were 65% reduction from 2015 baseline. 11 However, lack of reliable baseline data from public health surveillance systems, resource constraints and limited infrastructure for collection of strategic information, and low screening capacity in many countries has led to the proposal for alternative population‐level targets: ≤4/100,000 and ≤2/100,000 population per annum for HBV and HCV respectively. 12

Many countries will be reliant on death certificate‐based information to establish mortality monitoring systems, but this relies on inclusion of both liver disease and underlying HBV or HCV for attribution. Settings in which there are HBV and HCV notification registries and capacity to link these notifications to administrative datasets including hospitalisations and death registries have the capacity to provide more reliable monitoring of liver‐related mortality.

We propose a definition of liver‐related mortality among people with an HBV or HCV notification as records of any death (i.e. all‐cause) after a first‐time ESLD admission (‘post‐ESLD hospitalisation‐related mortality’). In New South Wales (NSW), Australia, annual linkages between HBV and HCV notifications, up‐to‐date hospital admissions and all‐cause mortality are highly feasible. 13 Considering high levels of HBV and HCV testing (68% and 79% respectively) 14 and the inclusion of most hospitals (93%) (approximately 400 facilities) 13 , 15 in data linkage, post‐ESLD hospitalization‐related mortality would be a valuable tool for monitoring HBV and HCV liver deaths in NSW.

Given the established capacity for regular data linkages in Australia, this study aimed to evaluate the concordance of mortality records following hospitalization‐based ESLD versus two death certificate‐based definitions of liver death. A further objective was to evaluate the utility of unlinked cause‐specific mortality data in monitoring HBV‐ and HCV‐related liver mortality.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Study setting, data sources and record linkages

The Public Health Act 1991 requires mandatory notification for all individuals with positive HBV and HCV serology tests in NSW. 13 The NSW Notifiable Conditions Information Management System (NCIMS) holds these records. We used the NSW Admitted Patient Data Collection (APDC) to identify people with an HBV or HCV notification, and DC or HCC diagnosis or a history of alcohol‐use disorder (AUD). APDC database covers all inpatient admissions from public and private hospitals since 2001. Each hospitalization record includes demographic, administrative and diagnostic information coded at discharge according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10). We used NSW Perinatal data collection (PDC) which records all births in NSW, and includes demographic information since 1994. To identify people with HIV coinfection, we used the National HIV Registry (NHR), which has recorded mandatory HIV notifications since 1985. 16 Finally, we used two mortality databases to characterize deceased individuals, including the Registry of Births, Deaths, and Marriages (RBDM) and Cause of Death Unit Record File (COD URF), which have recorded all deaths in NSW since 1993. 13

Data linkages occurred at two stages. First, the New South Wales Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL) 13 linked HBV and HCV notifications internally to identify people with HBV/HCV coinfection. Using demographic details (including full name, sex, date of birth and address), CHeReL probabilistically linked records between the NCIMS, APDC, RBDM and COD URF. CHeReL used deterministic data linkage between NCIMS and NHR, using 2 × 2 name codes.

2.2. Study population and period

The study population included people with an HBV and HCV notification in NSW, Australia, during 1993–2017. Linked data were extracted for the following periods: NCIMS (1 January 1993–31 December 2017); APDC (1 July 2001–30 June 2018); PDC (1 January 1994–31 December 2016); RBDM (1 January 1993–30 June 2018); COD URF (1 January 1993–31 December 2016); and NHR (1 January 1985–31 December 2017).

2.3. Study outcomes

The primary outcome was death following ESLD hospitalization, evaluated between 2001 and 2016. Post‐ESLD hospitalization mortality included any death (i.e. all‐cause) following first‐time hospitalization due to HBV‐and HCV‐related DC and HCC. We used a hospital discharge diagnosis code (ICD‐10) to infer a diagnosis of DC and HCC; coded in either the underlying and/or contributing fields of a linked inpatient hospital record (Table S1).

The secondary outcome was death certificate‐based liver mortality with a mention of viral hepatitis, evaluated between 2013 and 2016. We used ICD‐10 coding to define deaths from ESLD (DC and HCC deaths) and all liver deaths (ESLD‐related and other liver causes). Death certificate‐based definitions and mentions of viral hepatitis were evaluated among the primary and secondary causes of death (Table S1).

2.4. Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were applied as follows:

Records where the HBV or HCV notification date occurred after censoring (post‐mortem notifications),

HCV/HBV, HCV/HIV and HBV/HIV coinfection notifications and

Records where the HCC diagnosis or death date was prior to January 1, 2001.

We excluded people with coinfection, given the relatively low proportions (<5% for each group 17 ), and to focus on HBV and HCV mono‐infection, given higher risk of liver morbidity and mortality among people with coinfection. 18 , 19

2.5. Statistical analysis

The linked dataset was cleaned, edited and prepared for this study in the STATA software version 16.0 (Stata Corp). First, we calculated descriptive statistics, including medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. We described demographic characteristics among all people with an HBV and HCV notification, all deceased individuals and those who died due to liver‐related causes. Causes of liver deaths included post‐ESLD hospitalization and two death certificate‐based definitions of liver death, comprising ESLD‐related (definition one‐death certificate ESLD‐related deaths) and all‐liver deaths (definition two‐death certificate liver disease‐related deaths).

Second, we examined the concordance between HBV and HCV post‐ESLD hospitalization mortality, compared with the two death certificate‐based definitions of liver death, including definitions one and two above. We undertook the concordance evaluation among people who died between 2001 and 2016. The analysis comprised (1) evaluation of trends in post‐ESLD hospitalization mortality numbers and (2) evaluation of deaths that were jointly defined between post‐ESLD hospitalization and the two death certificate‐based definitions. We also evaluated deaths post‐DC and HCC hospitalization separately. In these analyses, first admission for each of DC and HCC was used, therefore an individual with admission for both DC and HCC (either concurrently or consecutively) during the study period contributed data for both DC‐ and HCC‐specific analyses. Finally, to further evaluate the concordance between hospitalization‐ and death certificate‐based definitions, we evaluated trends in the primary and secondary causes of death among those who died of post‐ESLD hospitalization.

Third, we evaluated mention of viral hepatitis, HBV and HCV among the death certificate‐based definitions one and two above and death certificate‐based DC and HCC deaths. We undertook this analysis among people who died between 2013 and 2016.

To ensure maximum alignment with WHO guidelines and coding rules, the Australian Bureau of Statistics introduced an automated coding software (Iris) in 2013 that incorporates the most recent significant updates to the ICD‐10 and enables the production of timely and accurate mortality data. Given the changes due to software and coding updates, we did not include mortality data prior to 2013 in this analysis. 20

2.5.1. Demographic variables

History of AUD was identified through the APDC. AUD is a standard term used to define continued drinking despite adverse mental and physical consequences. AUD was defined according to hospitalization with at least one AUD‐related admission using the primary and/or secondary fields of linked hospitalization records 21 (Table S1). Liver‐related consequences of alcohol use are not included in the definition of AUD. 21

To improve reporting of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples on administrative data collections using record linkage, a method has been developed by the NSW Ministry of Health. We used the process, termed ‘enhanced’ reporting, which relies on having independent sources of information on whether a person is Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. An algorithm was applied across NCIMS, APDC and PDC datasets to identify Indigenous Australian ethnicity (Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander). 22

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study participants

Between 1993 and 2017, there were 63,292 persons with an HBV notification in NSW. The median birth year was 1967 (interquartile range 1957–1977). Overall, 55% were male, 16% were born in Australia, 4% identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and 2% had a history of AUD. During 2001–2016, 2671 (4.2%) persons died, with number and percent of these deaths liver disease‐related varying based on liver death definition: post‐ESLD hospitalization death (891, 33.3%); death certificate‐defined ESLD (615, 23.0%); and death certificate‐defined liver disease (982, 36.7%) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics among people with an HBV notification in NSW 1993–2017, by cause of death 2001–2016, n = 63,292.

| Characteristics, n (%) | All HBV | Deceased, 2001–2016 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All HBV deaths | Post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths | Death certificate liver disease deaths | Death certificate ESLD deaths | |||||||

| n = 63,292 | % | n = 2671 | % | n = 891 | % | n = 982 | % | n = 615 | % | |

| Year of birth, median (IQR) a | 1967 (1957, 1977) | 1945 (1933, 1956) | 1948 (1938, 1957) | 1947 (1937, 1957) | 1947 (1938, 1957) | |||||

| Male sex b | 34,249 | 55 | 1894 | 71 | 705 | 79 | 778 | 79 | 503 | 82 |

| Born in Australia c | 6582 | 16 | 534 | 21 | 149 | 17 | 159 | 17 | 81 | 13 |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander d | 1605 | 4 | 145 | 6 | 45 | 5 | 52 | 5 | 22 | 4 |

| Alcohol‐use disorder | 1352 | 2 | 284 | 11 | 141 | 16 | 147 | 15 | 79 | 13 |

| Age at death, median (IQR) | – | – | 65 (54, 77) | 61 (53, 71) | 61 (53, 71) | 61 (53, 70) | ||||

13 missing values.

511 missing values.

23,003 missing values.

20,984 missing values.

Compared to all HBV deaths, those who died post‐ESLD hospitalization were younger (median birth year 1948 vs. 1945), mostly men (79% vs. 71%), less likely born in Australia (17% vs. 21%) and more likely to have a history of AUD (16% vs. 11%). Further, people who died post‐ESLD hospitalization had a younger median age at death (61 years vs. 65 years) (Table 1).

Between 1993 and 2017, there were 107,430 persons with an HCV notification in NSW. The median birth year was 1965 (interquartile range 1958–1974). Overall, 64% were male, 79% were born in Australia, 15% identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and 18% had a history of AUD. During 2001–2016, 11,280 (10.5%) persons died, with number and percent of these liver disease‐related deaths varying based on liver death definition: post‐ESLD hospitalization death (3587, 31.7%); death certificate‐defined ESLD (2295, 20.3%); and death certificate defined liver disease (4590, 40.7%) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Demographic characteristics among people with an HCV notification in NSW 1993–2017, by cause of death 2001–2016, n = 107,430.

| Characteristics, n (%) | All HCV | Deceased, 2001–2016 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All HCV deaths | Post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths | Death certificate liver disease deaths | Death certificate ESLD deaths | |||||||

| n = 107,430 | % | n = 11,280 | % | n = 3587 | % | n = 4590 | % | n = 2295 | % | |

| Year of birth, median (IQR) a | 1965 (1958, 1974) | 1957 (1949, 1964) | 1956 (1949, 1960) | 1956 (1950, 1961) | 1955 (1948, 1959) | |||||

| Male sex b | 68,033 | 64 | 7998 | 71 | 2661 | 74 | 3413 | 75 | 1747 | 76 |

| Born in Australia c | 67,997 | 79 | 7916 | 73 | 2479 | 69 | 3171 | 71 | 1501 | 66 |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander d | 12,847 | 15 | 1219 | 11 | 294 | 8 | 403 | 9 | 159 | 7 |

| Alcohol‐use disorder | 19,865 | 18 | 4004 | 36 | 1940 | 54 | 2189 | 48 | 1175 | 51 |

| Age at death, median (IQR) | – | – | 53 (45, 62) | 56 (50, 62) | 55 (49, 62) | 56 (51, 63) | ||||

54 missing values.

482 missing values.

21,327 missing values.

23,321 missing values.

Compared to all HCV deaths, those who died post‐ESLD hospitalization were older (median birth year 1956 vs. 1957), mostly men (74% vs. 71%), less likely born in Australia (69% vs. 73%), and more likely to have a history of AUD (54% vs. 36%). Further, people who died post‐ESLD hospitalization had an older median age at death (56 years vs. 53 years) (Table 2).

3.2. Concordance between post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths and definitions one and two

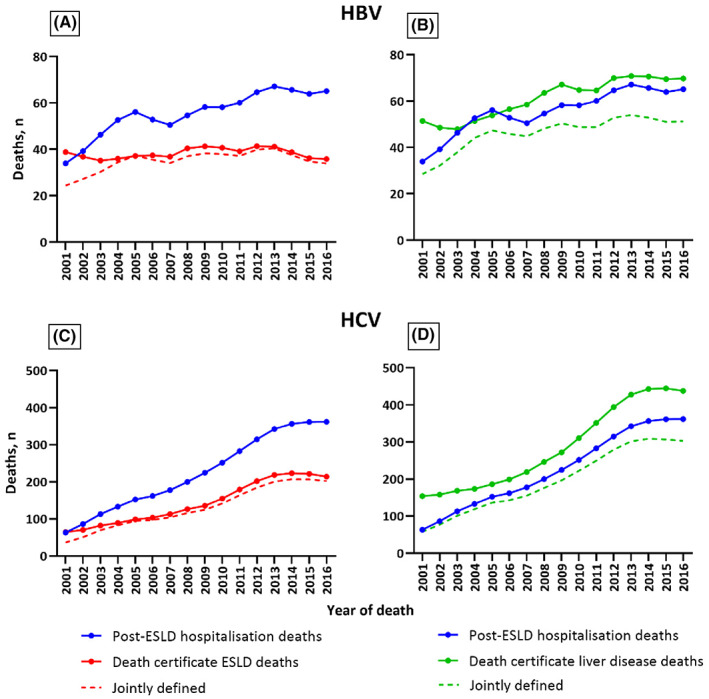

During 2001–2016, HBV post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths increased from 22 to 62 per annum. Among these post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths (n = 891), the number defined as liver deaths by death certificate was higher for all liver disease (741, 83%) than ESLD (562, 63%) (Figure 1A,B).

FIGURE 1.

Concordance between HBV and HCV post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths and death certificate‐defined ESLD (definition one) and liver disease‐related deaths (definition two) between 2001 and 2016.

During 2001–2016, HCV post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths increased from 38 to 347 per annum. Among these post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths (n = 3587), the number defined as liver deaths by death certificate was higher for all liver disease (3135, 87%) than ESLD (2082, 58%) (Figure 1C,D).

3.3. Concordance between DC component of post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths and definitions one and two

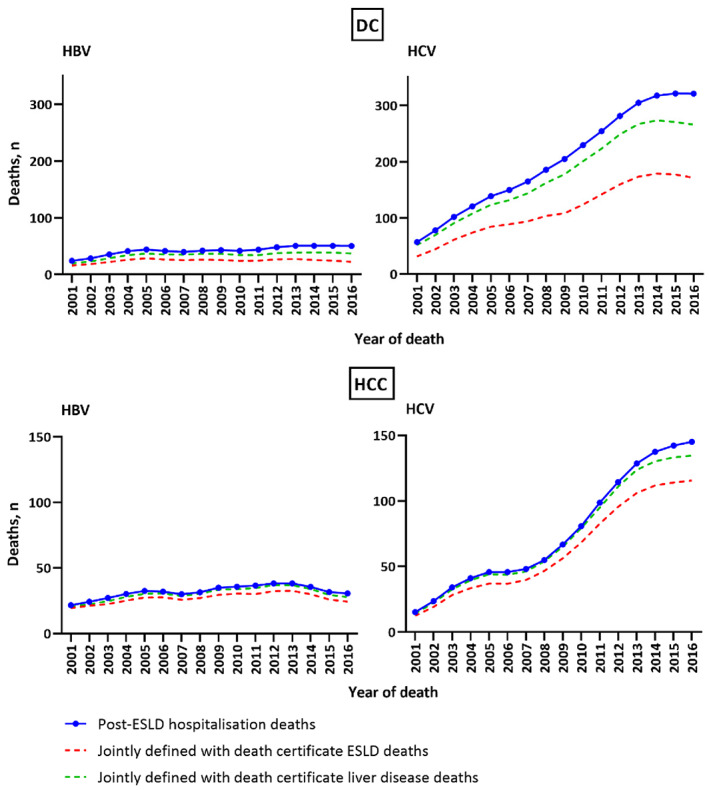

During 2001–2016, HBV post‐DC hospitalization deaths (i.e. hospital DC admission followed by all‐cause death) increased from 14 to 47 per annum. Among these post‐DC hospitalization deaths (n = 676), the number defined by death certificate was higher for all liver disease (546, 81%) than ESLD (390, 58%) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Concordance between DC and HCC component of HBV and HCV post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths and death certificate‐defined ESLD (definition one) and liver disease‐related deaths (definition two) between 2001 and 2016.

During 2001–2016, HCV post‐DC hospitalization deaths increased from 36 to 305 per annum. Among these post‐DC hospitalization deaths (n = 3236), the number defined by death certificate was higher for all liver disease (2812, 87%) than ESLD (1817, 56%) (Figure 2).

3.4. Concordance between HCC component of post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths and definitions one and two

During 2001–2016, HBV post‐HCC hospitalization deaths (i.e. hospital HCC admission followed by all‐cause death) increased from 17 to 29 per annum. Among these post‐HCC hospitalization deaths (n = 510), the number defined by death certificate was higher for all liver disease (482, 95%) than ESLD (431, 85%) (Figure 2).

During 2001–2016, HCV post‐hospitalization HCC deaths increased from 6 to 145 per annum. Among these post‐HCC hospitalization deaths (n = 1224), the number defined by death certificate was higher for all liver disease (1171, 96%) than ESLD (1007, 82%) (Figure 2).

3.5. Concordance between HBV and HCV post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths and primary and secondary causes of death

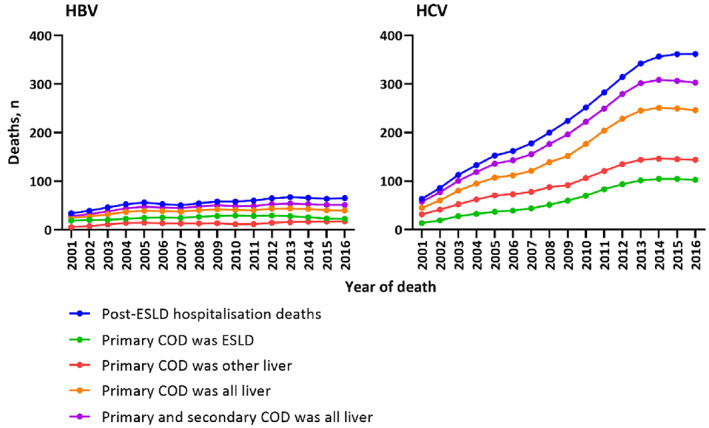

Among people with HBV notification, 891 liver deaths were identified by post‐ESLD hospitalization mortality during 2001–2016. Of these deaths, 398 (45%) and 611 (69%) recorded ESLD and liver disease as primary causes on death certificate respectively. Additionally, 741 (83%) of these deaths had liver disease as primary or secondary causes on death certificate (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Concordance between HBV and HCV post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths and primary and secondary causes of death between 2001 and 2016. COD, cause of death.

Among people with HCV notification, 3587 liver deaths were identified by post‐ESLD hospitalization mortality during 2001–2016. Of these deaths, 985 (27%) and 2511 (70%) recorded ESLD and all liver‐related deaths as primary causes on death certificate respectively. Additionally, 3135 (87%) of these deaths had liver disease as primary or secondary causes on death certificate (Figure 3).

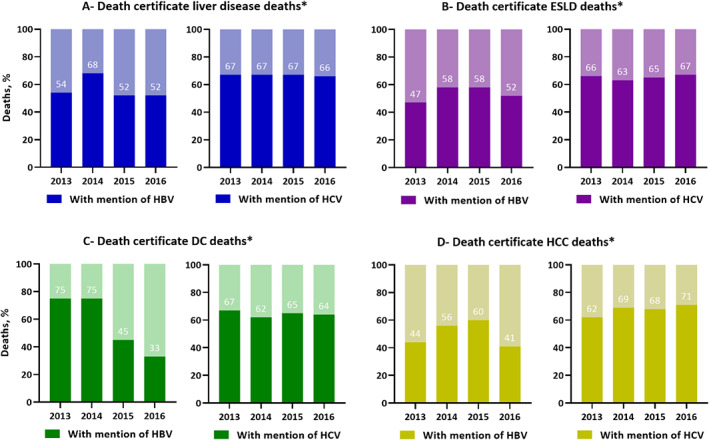

3.6. Trends in the number of death certificate‐defined liver disease, ESLD, DC and HCC deaths with a mention of viral hepatitis for HBV and HCV

During 2013–2016, mention of HBV among HBV notification‐linked death certificate deaths remained relatively stable for liver disease‐related (54%–52%), ‐ESLD‐related (47%–52%) and ‐HCC‐related (44%–41%) deaths. However, a decline from 75% to 33% for death certificate‐defined DC‐related deaths was noted (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Trends in death certificate‐defined liver disease, ESLD, DC and HCC deaths with a mention of viral hepatitis among HBV and HCV deaths between 2013 and 2016. *Data prior to 2013 is not shown, given a coding software error that existed pre‐2013 and led to under‐reporting of HBV and HCV deaths. 20

During 2013–2016, mention of HCV among HCV notification‐linked death certificate deaths remained relatively stable for liver disease‐related (67%–66%), ‐ESLD‐related (66%–67%) and ‐DC‐related (67%–64%) deaths. However, an increase from 62% to 71% for death certificate‐defined HCC‐related deaths was noted (Figure 4).

3.7. Mention of viral hepatitis, HBV and HCV among all people with HCC in their primary or secondary cause of death

Evaluation of all death certificates with HCC as cause of death with linkage to HBV or HCV notifications was undertaken. During 2013–2016, there was an increase in mention of HCV (48%–59%), and a decline in mention of HBV (10%–7%) (Figure S1).

4. DISCUSSION

Estimating and monitoring trends in HBV and HCV liver deaths is crucial to viral hepatitis elimination strategies. Our study demonstrates that liver death definitions based on hospitalization for ESLD followed by all‐cause death consistently give higher mortality than death certificate ESLD deaths, but generally lower than death certificate liver disease deaths. Temporal trends in liver deaths were similar for post‐ESLD hospitalization and death certificate liver disease categories, while death certificate ESLD demonstrated an increasing discordance over time. A large proportion of death certificate deaths, known to be linked to HBV and HCV notifications, had no mention of HBV or HCV, clearly demonstrating that monitoring of HBV and HCV liver deaths through death certificate information alone would underestimate mortality burden at the population‐level. Our methodology can also be applied to other settings and countries that have high rates of HBV and HCV diagnosis and notification and capacity to link to administrative datasets including hospital admissions and death registries.

Concordance between post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths and death certificate deaths was lower for death certificate ESLD deaths. Under‐ascertainment of HBV‐and‐HCV‐related mortality on death certificates has been demonstrated for many countries, including England, 8 Scotland, 23 Switzerland, 24 and United States. 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 Based on the post‐ESLD hospitalization liver death definition, concordance was considerably lower for death certificate DC compared to HCC deaths (58% vs. 85% for HBV and 56% vs. 82% for HCV respectively). The increasing discordance during the study period, particularly for DC (75%–33%), could in part be explained by improved antiviral therapy for HBV, 29 as reversal of DC is well described following treatment initiation. 30 , 31 Thus, many people admitted for DC with subsequent antiviral therapy initiation may have died of other causes, with this trend increasing over time. In contrast, although more effective HBV antiviral therapy has improved survival following HBV‐related HCC, 32 , 33 it is likely the vast majority of deaths following HCC remain liver‐related. Improved antiviral therapy is unlikely to provide a similar explanation for discordance between HCV post‐ESLD hospitalization and death certificate ESLD deaths, as interferon‐free direct‐acting antiviral (DAA) therapy only became broadly available in 2016 34 and interferon‐based therapy was contraindicated in patients developing ESLD. Other studies have shown it is more likely that someone with HBV‐DC hospitalization dies of another cause than HCV‐DC, certainly in the pre‐DAA era. 8 HBV antiviral therapy has improved markedly over the last two decades, with lamivudine approved in 1998, entecavir in 2005, and tenofovir in 2008. 7 , 29

Spontaneous HCV infection clearance could be the reason for some post‐ESLD hospitalization deaths where HCV was not mentioned on death certificates. In our cohort, the HCV notifications were based on either HCV antibody or HCV RNA testing. A proportion of HCV antibody‐based notifications may have had spontaneous clearance, 35 and developed advanced liver disease due to other etiologies (e.g. alcohol use), which can be a potential source of discordance between liver‐related deaths and mention of HCV.

Our study highlights ongoing concerns with sole use of death certificate‐based data to estimate and monitor trends in HBV and HCV liver deaths as shown in other studies. 25 , 27 Some studies have shown mention of ‘viral hepatitis’ on the death certificates to be relatively common in HCC cases, compared to the proportion specifically mentioning HBV or HCV. 28 But, estimates and trends are required separately for HBV and HCV liver deaths to evaluate specific strategies. We believe the optimum data for monitoring HBV and HCV liver deaths is either ESLD hospitalisations with vital status information or a combination of this information with cause‐specific death certificate data. An alternative would be to estimate the level of under‐ascertainment of HBV and HCV liver deaths through death certificate information alone and adjust these estimates to reflect population‐level mortality burden. Thus, if HCV notification linkage studies demonstrate that around half of death certificate HCC deaths have mention of HCV, monitoring using death certificate data alone would double the number of cases found. A limitation in this method is that under‐ascertainment may change over time, requiring capacity for regular estimation of its extent.

5. LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations worthy of discussion. First, in NSW, administrative data sources were available for different time periods. Hence, the study time period was restricted to improve the accuracy of trends in DC and HCC diagnosis numbers. Second, misclassification (over‐diagnosis) or missed cases (underdiagnosis) could be introduced since we relied on hospitalization coding data to diagnose DC and HCC. Previous Canadian and NSW validation studies demonstrated high (around 90%) HCC diagnostic concordance through hospitalization and administrative data; however, sensitivity analysis for validating DC events through hospital admission records has not been done in NSW. 36 , 37 , 38 Third, to study the real‐world mortality among individuals with HBV/HCV notifications in NSW, post‐ESLD hospitalization‐related mortality was based on deaths following hospital admissions for DC or HCC, thus excluding liver‐related deaths which occurred without a previous hospitalization. 39 Fourth, data collected by record linkage lacks additional information on risk factors. Fifth, continuous monitoring and evaluation of HCV‐related DC mortality in the post‐DAA era remain important to evaluate the long‐term effect of DAA and develop effective interventions, which was missing in our study. Sixth, we acknowledge that using administrative data for defining alcohol use disorder has clear limitations. Simple imputation for missing alcohol use responses creates opportunities for error and may have biased alcohol risk estimates (68% sensitivity and 97% specificity for the diagnosis of heavy alcohol intake). 40 Lastly, in Australia, HCV notifications are based on either HCV antibody or HCV RNA testing. Then it is possible that some HCV antibody‐based notifications who were not confirmed by HCV RNA had spontaneous clearance.

6. CONCLUSION

The sole use of death certificate‐based data to assess HBV‐ and HCV‐related liver disease mortality trends is of concern. Our study supports the use of ESLD hospitalisations with vital status information or a combination of ESLD hospitalisations with cause‐specific death certificate data as an efficient data source to represent HBV‐ and HCV‐related liver mortality. Assessing HBV‐ and/or HCV‐related HCC mortality without linking healthcare administrative datasets remains a challenge. A cross‐jurisdictional linkage‐based approach of utilizing post‐ESLD hospitalization and death certificate mortality datasets should be devised to unlock the full potential of administrative data. Sharing and evaluating our linkage methods will enable us to develop high‐quality, standardized, reproducible linkage systems to ensure optimal case ascertainment and improve mortality identification.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SHBUS, MA, HV and GJD contributed to study conception and design, data acquisition and analysis, interpretation of findings and drafting of the manuscript; GM and BH contributed to data acquisition and analysis and interpretation of findings.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The Kirby Institute is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health, under the agreement ID number 2‐D3X513. This publication is part of the Bloodborne viruses and sexually transmissible infections Research, Strategic Interventions and Evaluation (BRISE) program, funded by the New South Wales Ministry of Health. GD is supported by an NHMRC of Australia Program Grant (1150078) and Investigator Fellowship (2008276).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

GJD has received research support from Gilead Sciences, Merck and AbbVie. GM has received research support from Gilead Sciences and AbbVie. Other authors have no commercial relationships that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with this manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This publication involved information already collected by population‐based health administration registries; therefore, people have not been ‘recruited’ for the purposes of this research. Ethics approvals for the study were granted by the New South Wales Population & Health Services Research Ethics Committee, Cancer Institute New South Wales (reference number HREC/13/CIPHS/63), the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (reference number EO2014/3/114) and the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales (reference number 1215/6).

Supporting information

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the New South Wales Ministry of Health for the provision of HBV and HCV notifications, hospital admissions, death data and the Australian Institute for Health and Welfare (AIHW) for the provision of Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and Medicare Benefits Scheme data. We also thank the ethics committees of New South Wales Population and Health Services Research, AIHW, New South Wales Ministry of Health, and the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales for their approval of this publication. Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley ‐ University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Shah SHBU, Alavi M, Hajarizadeh B, Matthews G, Valerio H, Dore GJ. Liver‐related mortality among people with hepatitis B and C: Evaluation of definitions based on linked healthcare administrative datasets. J Viral Hepat. 2023;30:520‐529. doi: 10.1111/jvh.13824

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

This publication involved information collected by population‐based health administration registries. Data used for this research cannot be deposited on servers other than those approved by ethics committees. This publication has used highly sensitive health information by linking several administrative datasets. De‐identified linked information has been provided to the research team under strict privacy regulations. Except in the form of conclusions drawn from the data, researchers do not have permission to disclose any data to any person other than those authorised for the research project.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mazzali C, Duca P. Use of administrative data in healthcare research. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(4):517‐524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gavrielov‐Yusim N, Friger M. Use of administrative medical databases in population‐based research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(3):283‐287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Langan SM, Benchimol EI, Guttmann A, et al. Setting the RECORD straight: developing a guideline for the REporting of studies conducted using observational routinely collected data. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:29‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iburg KM, Mikkelsen L, Adair T, Lopez AD. Are cause of death data fit for purpose? Evidence from 20 countries at different levels of socio‐economic development. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mikkelsen L, Iburg KM, Adair T, et al. Assessing the quality of cause of death data in six high‐income countries: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Japan and Switzerland. Int J Public Health. 2020;65(1):17‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization . Global Hepatitis Report, 2017. World Health Organization; 2017:83. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhou K, Dodge JL, Grab J, Poltavskiy E, Terrault NA. Mortality in adults with chronic hepatitis B infection in the United States: a population‐based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52(2):382‐389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Simmons R, Ireland G, Ijaz S, Ramsay M, Mandal S. Causes of death among persons diagnosed with hepatitis C infection in the pre‐ and post‐DAA era in England: a record linkage study. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26(7):873‐880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV, Goulis J, et al. The impact of newer nucleos(t)ide analogues on patients with hepatitis B decompensated cirrhosis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28(1):109‐117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization . Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016–2021. World Health Organization; 2016:53. [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization . Global Progress Report on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2021. Accountability for the Global Health Sector Strategies 2016–2021: Actions for Impact. World Health Organization; 2021:108. [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization . Interim Guidance for Country Validation of Viral Hepatitis Elimination. World Health Organization; 2021:96. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Health N . The Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL) NSW Health. 2022. Accessed March 18, 2022. http://www.cherel.org.au/

- 14. Institute K . National Update on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmissible Infections in Australia: 2009–2018. The Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Department SR . Number of Hospitals New South Wales, Australia 2017–2018 by Type. 2022. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/651753/australia‐number‐of‐hospitals‐in‐nsw‐by‐type/#:~:text=As%20of%202018%2C%20there%20were,hospitals%20across%20New%20South%20Wales

- 16. McDonald AM, Crofts N, Blumer CE, et al. The pattern of diagnosed HIV infection in Australia, 1984‐1992. AIDS. 1994;8(4):513‐519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Valerio H, Alavi M, Law M, et al. High hepatitis C treatment uptake among people with recent drug dependence in New South Wales, Australia. J Hepatol. 2021;74(2):293‐302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Christian B, Fabian E, Macha I, et al. Hepatitis B virus coinfection is associated with high early mortality in HIV‐infected Tanzanians on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2019;33(3):465‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hernandez MD, Sherman KE. HIV/HCV coinfection natural history and disease progression, a review of the most recent literature. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6(6):478‐482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Statistics ABo . Technical Note 1 Abs Implementation of Iris Software: Understanding Coding and Process Improvements. ABS, ed. 2022.

- 21. Friedmann PD. Alcohol use in adults. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1655‐1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Division PaPH . Improved Reporting of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples on Population Datasets in New South Wales Using Record Linkage–A Feasibility Study. Evidence CfEa, ed. NSW Ministry of Health; 2012:53. [Google Scholar]

- 23. McDonald SA, Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM, et al. The growing contribution of hepatitis C virus infection to liver‐related mortality in Scotland. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(18):19562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keiser O, Giudici F, Müllhaupt B, et al. Trends in hepatitis C‐related mortality in Switzerland. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(2):152‐160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mahajan R, Xing J, Liu SJ, et al. Mortality among persons in care with hepatitis C virus infection: the chronic hepatitis cohort study (CHeCS), 2006‐2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(8):1055‐1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Manos MM, Leyden WA, Murphy RC, Terrault NA, Bell BP. Limitations of conventionally derived chronic liver disease mortality rates: results of a comprehensive assessment. Hepatology. 2008;47(4):1150‐1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bixler D, Zhong Y, Ly KN, et al. Mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis B infection: the chronic hepatitis cohort study (CHeCS). Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(6):956‐963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jiang JJ, Shiels MS, O'Brien TR. Death certificates compared to SEER‐Medicare data for surveillance of liver cancer mortality due to hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection. J Viral Hepat. 2021;28:934‐941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nguyen VH, Le AK, Trinh HN, et al. Poor adherence to guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection at primary care and referral practices. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(5):957‐967.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jang JW, Choi JY, Kim YS, et al. Effects of virologic response to treatment on short‐ and long‐term outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection and decompensated cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(12):1954‐1963.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee HW, Yip TC, Tse YK, et al. Hepatic decompensation in cirrhotic patients receiving antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(9):1950‐1958.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hui VW, Chan SL, Wong VW, et al. Increasing antiviral treatment uptake improves survival in patients with HBV‐related HCC. JHEP Rep. 2020;2(6):100152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Papatheodoridis GV, Idilman R, Dalekos GN, et al. The risk of hepatocellular carcinoma decreases after the first 5 years of entecavir or tenofovir in Caucasians with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2017;66(5):1444‐1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dore GJ, Hajarizadeh B. Elimination of hepatitis C virus in Australia: laying the foundation. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2018;32(2):269‐279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Grebely J, Page K, Sacks‐Davis R, et al. The effects of female sex, viral genotype, and IL28B genotype on spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2014;59(1):109‐120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lapointe‐Shaw L, Georgie F, Carlone D, et al. Identifying cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in health administrative data: a validation study. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Alavi M, Grebely J, Hajarizadeh B, et al. Mortality trends among people with hepatitis B and C: a population‐based linkage study, 1993‐2012. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Alavi M, Law MG, Grebely J, et al. Time to decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma after an HBV or HCV notification: a population‐based study. J Hepatol. 2016;65(5):879‐887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alavi M, Law MG, Valerio H, et al. Declining hepatitis C virus‐related liver disease burden in the direct‐acting antiviral therapy era in New South Wales, Australia. J Hepatol. 2019;71(2):281‐288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim HM, Smith EG, Stano CM, et al. Validation of key behaviourally based mental health diagnoses in administrative data: suicide attempt, alcohol abuse, illicit drug abuse and tobacco use. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Data Availability Statement

This publication involved information collected by population‐based health administration registries. Data used for this research cannot be deposited on servers other than those approved by ethics committees. This publication has used highly sensitive health information by linking several administrative datasets. De‐identified linked information has been provided to the research team under strict privacy regulations. Except in the form of conclusions drawn from the data, researchers do not have permission to disclose any data to any person other than those authorised for the research project.