Abstract

Objectives

Informal carers play a critical role in supporting people with dementia. We conducted a scoping review and a qualitative study to inform the identification and development of carer‐reported measures for a dementia clinical quality registry.

Methods

Phase 1—Scoping review: Searches to identify carer‐reported health and well‐being measures were conducted in three databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Embase). Data were extracted to record how the measures were administered, the domains of quality‐of‐life addressed and whether they had been used in a registry context. Phase 2—Qualitative study: Four focus groups were conducted with carers to examine the acceptability of selected measures and to identify outcomes that were important but missing from these measures.

Results

Phase 1: Ninety‐nine carer measures were identified with the top four being the Zarit Burden Interview (n = 39), the Short‐Form12/36 (n = 14), the Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced scale and the Sense of Coherence scale (both n = 9). Modes of administration included face‐to‐face (n = 50), postal (n = 11), telephone (n = 8) and online (n = 5). No measure had been used in a registry context. Phase 2: Carers preferred brief measures that included both outcome and experience questions, reflected changes in carers' circumstances and included open‐ended questions.

Conclusions

Carer‐reported measures for a dementia clinical quality registry need to include both outcome and experience questions to capture carers' perceptions of the process and outcomes of care and services. Existing carer‐reported measures have not been used in a dementia registry context and adaption and further research are required.

Keywords: informal caregivers, dementia, quality of health care, quality of life, registries

Policy Impact.

Existing carer‐reported measures have not been used in a dementia clinical quality registry context and adaption and further research are required. Importantly, carer‐reported measures for a dementia clinical quality registry need to include both outcome and experience questions to capture carers' perceptions of the process and outcomes of care and services.

1. INTRODUCTION

Dementia is a global public health priority and represents one of the greatest challenges for health and social services across the world. 1 Worldwide, over 55 million people have dementia. 1 , 2 With population ageing, the number of people living with dementia is estimated to increase significantly, reaching 78 million in 2030 and 139 million in 2050 worldwide. 2

Informal carers play a critical role in supporting people with dementia and are a key determinant of patient outcomes such as quality of life and entry to residential aged care. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Informal carers may vary from family members to friends and neighbours, with the former identified as providing the majority of the care. 7 , 8 , 9 A report by Alzheimer's Disease International estimated that worldwide, 84% of people with dementia lived at home and an annual 82 billion hours of informal care were provided to this group, equating to 2089 h per year or 6 h per day per person with dementia. 9 Informal carers provide a wide range of support, such as assisting with activities of daily living including personal care, making decisions about care and treatment options, and organising care and services. 1 , 7 , 8 , 9 Informal carers typically know the person with dementia well and therefore provide crucial information to help develop effective personalised and need‐based interventions and care plans. 1

There is clear evidence that caring for a person living with dementia can have both positive and negative impacts on carers' lives. The positive aspects of caregiving include strengthening of the relationship, spiritual and personal growth, increasing meaning in life, and experiencing feelings of accomplishment. 10 , 11 , 12 The negative aspects include carer burden or stress, poor psychological or physical health, social isolation and financial hardship. 6 , 10 , 13 Compared with carers of people with other diseases, carers of people with dementia report higher levels of stress, burden, depression and anxiety, poorer physical health and greater financial difficulties. 14 Consequently, carers of people with dementia are sometimes referred to as ‘the invisible second patients’ in recognition of these challenges associated with the care they give. 15

1.1. Including carer‐reported measures in a dementia clinical quality registry

High‐quality clinical care can better support people with dementia and their families and improve their quality of life. 6 , 16 , 17 Yet, variations in the quality of clinical care for people with dementia are reported frequently. 18

Clinical quality registries (CQRs), that is, organisations that ‘systematically monitor the quality (appropriateness and effectiveness) of health care, within specific clinical domains, by routinely collecting, analysing and reporting health‐related information’, 19 are increasingly recognised worldwide as a valuable tool to reduce variations, and importantly, drive improvements in the provision of clinical care. Several dementia CQRs have been established internationally, such as the Swedish Dementia Registry (SveDem), Norwegian Dementia Registry (NorKog) and the Danish Dementia Registry, with evidence showing that dementia CQRs can drive quality improvements in the diagnosis, management and care of people with dementia and support for their carers, as well as reduce cost of dementia. 20 Against this background, the Australian Dementia Network (ADNeT) Registry has been established at dementia diagnostic services across Australia, to monitor and improve the quality of care and patient outcomes for people with dementia and mild cognitive impairment and their carers. 21

While the inclusion of patient‐reported measures has been emphasised in CQR data collection to provide a patient perspective on the impact and health outcomes of clinical care and to inform patient‐centred care, 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 less attention has been paid to carer‐reported measures. In this paper, a carer‐reported measure was defined as a measurement of the carers' health and well‐being‐related outcomes that are directly reported by the carer. Examples include quality‐of‐life measures, burden, stress/distress, coping strategies, satisfaction, efficacy, health rating, consequences of care or measures indicating the level of carer function and participation beyond the home. Carer‐reported measures do not include proxy‐rated measures that are completed by carers but focus on patient outcomes.

Given the vital roles that carers play in supporting people with dementia and the impact of caregiving on carers, the ADNeT Registry also includes carer‐reported measures, in addition to patient‐reported measures. 21 Including carer‐reported measures in dementia CQRs can help to understand the changes in caregiving over the course of disease and the impact of clinical care from carers' perspective. It can also inform the development of interventions that aim at improving outcomes for carers, which ultimately will help carers to provide better support to people living with dementia.

Although there have been a few reviews on quality of life or well‐being measures for informal carers of people with dementia, 26 , 27 , 28 none of these reviews have considered the use of these measures in the context of a dementia CQR. A CQR aims at enroling an entire population within a clinical domain; therefore, the carer‐reported measures need to be able to be used at scale, and by a real‐world clinical population. To our knowledge, none of the existing dementia CQRs include carer‐reported measures. To inform the identification and/or development of carer‐reported measures for the ADNeT Registry, we conducted a systematic scoping review and a qualitative study. The aim of the scoping review was to identify carer‐reported measures, which could potentially be used in a dementia CQR. The aim of the qualitative study was to examine the acceptability of carer‐reported outcome measures identified from the scoping review and to identify outcomes that were important to carers but missing from identified measures.

2. METHODS

2.1. Phase 1: A systematic scoping review

2.1.1. Research questions and study design

The key research questions guiding this review were as follows:

What carer‐reported measures have been used in dementia research?

Have the identified measures been used in a dementia CQR?

What quality‐of‐life domains were addressed in identified measures?

How were the measures administered?

A scoping review was undertaken following the methodological framework of Arksey and O'Malley (2005) due to the broad and exploratory nature of the review questions. 29 Scoping reviews are not eligible for registration with PROSPERO; however, the review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) statement.

2.1.2. Data search and selection

We completed a systematic search of three databases: Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Embase on 21st August 2018 using a combination of three groups of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH):(1) dementia, Alzheimer's disease, Cognitive dysfunction, Cogniti*, (2) Carer OR Caregiver OR Care*, (3) quality of life, well‐being, care*burden, care*stress. The search was limited to full‐text, peer reviewed articles published in English between 2008 and 2018 to identify the most current carer‐reported measures.

2.1.3. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were primary studies that (1) included adult informal carers (i.e. aged ≥18 years) for people with dementia living in the community (as they require significantly more support from informal carers compared to those living in residential aged care facilities), (2) included a carer‐reported measure as an outcome measure, (3) interventional studies that were primarily directed towards the carers (as these would measure carer health and well‐being as an outcome) and (4) conducted in Australia and countries that have similar socio‐economic status (e.g. the US, Canada, UK, European Union and New Zealand).

Exclusion criteria were (1) studies of informal carers for people with dementia in hospitals, palliative care or residential care, (2) interventional studies that were primarily directed to people with dementia as these were less likely to include carer outcomes as a primary outcome, (3) drug trials, (4) studies examining psychometric properties of a measure, (5) studies focussing on proxy reported ‘patient’ outcomes and (6) qualitative studies, commentaries, debates or editorials, economic evaluations or systematic reviews.

2.1.4. Screening

Search results were imported into and managed through Covidence software with duplicates removed. Two researchers (Authors 5 and 12) independently screened titles and abstracts against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles meeting the inclusion criteria were assessed for eligibility via full‐text review. Disagreements were discussed, with discordant decisions managed by a third reviewer (Author 3).

2.1.5. Data extraction

Data extracted included study design, country, participant demographics, dementia subtype, carer‐reported measures that were used and their administration methods.

2.1.6. Data analysis

Descriptive analysis of the study characteristics was performed. Content analysis was conducted to categorise the key attributes of the measures and the administration methods.

2.2. Phase 2: A descriptive qualitative study

2.2.1. Aims and study design

Following the scoping review, a descriptive qualitative study was conducted via focus groups with people who identified as a carer for someone with dementia.

A descriptive qualitative design 31 was chosen as our focus was on exploring the experience of caregiving and to obtain acceptability information about selected carer‐reported outcomes.

2.2.2. Participants and recruitment

Eligible participants were people who self‐identified as current informal carers of a family member with dementia and lived either at home or in residential aged care. Recruitment was through an advertisement on the website of consumer organisations, social media, word of mouth and flyers to relevant carer organisations and groups. Ethics approval was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 16840, Approval date: 15th October 2018).

After receiving expressions of interest from potential participants, a research assistant screened them to confirm eligibility. Four focus groups were conducted to suit the availability and geographical areas of participants. All participants provided verbal consent to participate (as per our ethics approval) and to the recording before the focus group commenced. The focus groups were conducted between November 2018 and March 2019 and were 82–97 min in length.

2.2.3. Data collection

Each focus group started with questions about the participants' experience of caring for someone with dementia (these results will be reported in a separate publication). Participants were then provided with selected carer‐reported measures, including the top three measures identified from the scoping review and two additional measures. These additional measures were included because none of the carer‐reported measures identified from the scoping review had been used in the context of a dementia CQR. To address this implementation gap, the researchers contacted colleagues working in the CQR registry field for carer‐reported measures that could potentially be used in a dementia CQR. The Cancer Survivors Partners Unmet Needs (CaSPUN) survey and the Carer Experience Survey (CES) were identified through this process. The CaSPUN survey was recommended because it has extensive questions specific to the impact of the disease on the relationship between the person with the disease and the carer. 31 The CES was recommended because it is brief and assesses carer quality of life beyond health. 32 As a result, five carer‐reported measures were explored in the qualitative study.

Participants were asked to complete these measures while interacting with other participants and ‘thinking aloud’. 33 They discussed (1) whether the questions in the selected measures made sense?, (2) what the questions meant to them?, (3) what they felt was missing from the measures (if anything)? and (4) any questions or words in the measures that they would like to remove or change? The number of carer‐reported measures discussed at each focus group ranged from one to three, depending on the size of the focus groups and the time available following the initial phase of the focus group discussion. All focus groups were facilitated by experienced qualitative researchers (Authors 3, 5, 12 and 14).

2.2.4. Data analysis

The focus group recording was transcribed verbatim by an author (Author 9). As per descriptive qualitative studies, 30 content analysis was conducted using deductive coding processes by two authors (Authors 9 and 14). Both authors had extensive experience in qualitative studies.

Specifically, the two authors developed a set of key codes based on the aims of this phase. These key codes included question and response wording, length of measures, instructions for completion, missing questions and overall impressions of the measures. One author (Author 9) then went through the transcript, assigned the predefined set of key codes to the transcript, and selected quotes. Finally, the two authors met and discussed the assignment of key codes and the selection of quotes until consensus was reached.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Phase 1: A systematic scoping review

3.1.1. Study characteristics

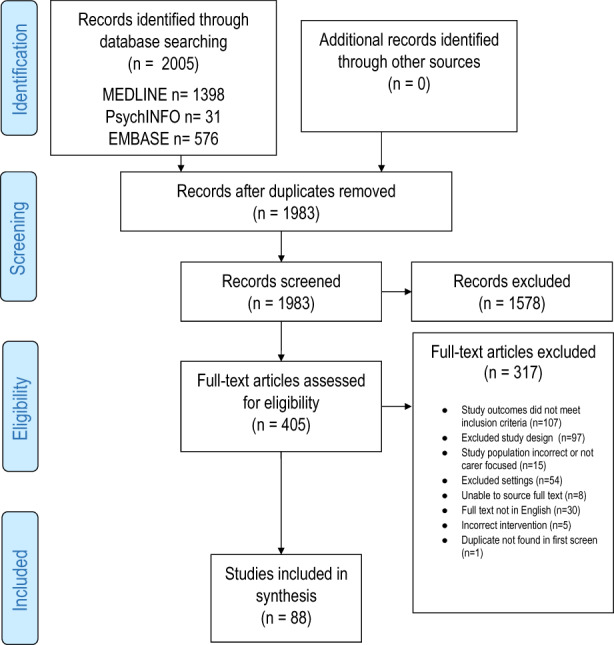

The search yielded 2005 papers with 92 meeting inclusion criteria after full‐text screening (Figure 1). These papers reported the results of 88 studies with seven papers merged into three studies as they reported data from the same cohort at different time points. 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 Twenty‐two (25%) of the studies were conducted in the United States, nine were in Spain (20%), eight were multicountry (9%), seven were in Italy (8%) and the remainder were spread across 16 individual countries. Study designs ranged from cross‐sectional (n = 69), comparative cross‐sectional (n = 6), longitudinal prospective cohort (n = 12), to one retrospective cohort study.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

A total number of 19,829 participants (carers) were included in the 88 studies. The ages of the carers ranged from 20 years 41 to 96 years. 42 The descriptors of the people they cared for included dementia (n = 45), Alzheimer's disease (n = 29) and frontotemporal dementia (n = 4). While most studies included carers of one particular type of dementia, six studies included carers of two types 8 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 and three studies included carers of all three types 41 , 48 , 49 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographics/characteristics of studies (n = 88, total participants 19,829)

| Author, year | Country | Sample size | Carer age mean (SD); range | Study design | Carer‐reported measure used | Diagnosis of person being cared for: | Delivery method | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia | AD | FTD | |||||||

| Alwin et al., 2010 | Sweden | 110 | 67.3 (12.0) | CS | SF‐12; WHOQoL‐5; EQ‐5D; COPE Index | ✓ | F2F or telephone interviews by the project research team | ||

| Andrén & Elmståhl, 2008 | Sweden | 130 |

61 (NS) 27–90 |

CS | CBS; SOC; NHP ‐ Swedish translation; EQ‐5D | ✓ | F2F at home by geriatric registered nurse | ||

| Armstrong et al., 2013 | US | 102 | NS | CS | ZBI | ✓ | ✓ | NS | |

| Bakker et al., 2014 | Netherlands | 205 |

58.4 (9.3) 20–88 |

CS | SSCQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | F2F interviews by trained researchers and research assistants |

| Bednarek et al., 2016 | Netherlands | 205 |

58.4 (9.3) 25–88 |

CS | ZBI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | F2F interviews |

| Bekhet, 2014 | US | 73 |

57.46 (NS) 25–87 |

CS | ZBI | ✓ | Delivered and collected by research assistant | ||

| Bergvall et al., 2011 | Spain, Sweden, UK and US | 866 | 60.6 (14.2) Sp | CS | ZBI; SF‐12; WHOQoL‐Brief | ✓ | F2F interview with physician or a research nurse | ||

| 70.2 (12.2) Sw | |||||||||

| 71.3 (11.7) UK | |||||||||

| 66.9 (13.6) US | |||||||||

| Borsje et al., 2016 | Netherlands | 117 |

67.3 (13.3) 32–92 |

Prospective cohort study | SCQ; GHQ‐12 | ✓ | F2F interviews at home by trained research assistant | ||

| Bremer et al., 2015 | Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden, Spain and UK | 1029 | 64.6 (13.6) | CS | GHQ‐12; EQ‐VAS (from EQ‐5D) | ✓ | F2F interviews | ||

| Bristow et al., 2008 | England | 61 | Carers 62.9 (5.9) Controls 63.3 (5.4) | Comparative CS | GHQ‐30; PSS‐10; SOS; CBS; WCQ‐R; SACL | ✓ | Questionnaire packs handed out | ||

| Brodaty et al., 2014 | Australia | 732 | 78.3 (7.4) | Prospective cohort study | ZBI | ✓ | ✓ | F2F interviews | |

| Campbell et al., 2008 | England | 74 |

67.76 (12) 37–90 |

CS | ZBI; MSQFOP | ✓ | Measures handed to carers at clinic, posted back | ||

| Chen et al., 2013 | US | 87 | NS | CS | ASA; GSS; CDS; LEE | ✓ | Postal with phone interview | ||

| Chen et al., 2014 | US | 91 | 55 (7.1) | CS | CMAI; PSS; CDS; CSS‐6 | ✓ | Postal | ||

| Conde‐Sala et al., 2014 | Spain | 330 | 59.7 (0.8) at baseline | Prospective cohort study | ZBI; SF‐12 | ✓ | F2F interview | ||

| Contador et al., 2012 | Spain | 130 | 58.62 (12.4) | CS | BEEGC‐20; ZBI | ✓ | F2F interviews | ||

| Cooper, et al., 2008 and Cooper, Owens et al., 2008 | England | 93 (83) |

63.9 (14.8) 64.2 (15.4) |

CS of a longitudinal study at TP1: 1‐year; TP2: 3.5 year | TP1: Brief COPE; HSQ‐12; SRRS; ZBI; QoL‐AD; TP2: AQ; Brief COPE; ZBI | ✓ | F2F interviews | ||

| Creese et al., 2008 | Canada | 60 |

73.65 (9.3) 49–93 |

CS | PSQI – modified; SF‐12; HPLP; S‐ZBI | ✓ | Telephone interviews | ||

| DeFazio et al., 2015 | Italy | 150 |

NS 94 > 50 years |

CS | CBI | ✓ | F2F Interviews by physicians | ||

| DeLabra et al., 2015 | Spain, Poland, Denmark | 101 |

61.25 (12.6) 25–88 |

CS | ZBI; CCS: SSQRS; RCSS | ✓ | ‐ | ||

| Di Mattei et al., 2008 | Italy | 112 |

58.94 (12.05) 32–81 |

CS | CBI; COPE ‐ Italian | ✓ | F2F on‐ward inferred, from research assistants | ||

| Diehl‐Schmid et al., 2013 | Germany | 94 |

59.11 (11.7) 24–78 |

CS | CSI | ✓ | ✓ | Pack posted, follow‐up phone call | |

| Ducharme et al., 2016 | Canada | 96 |

YOD 53.06 (10.2) OOD 63.88 (13.0) |

Comparative descriptive | PCS; RSCSE; CAMI; FCCS; PDI; PFCNS; ISSB | ✓ | ✓ | F2F by trained interviewers | |

| Epstein‐Lubow et al., 2008 | US | 33 |

No persisting burden: 65.5 (14.0) Persisting: 60.7 (8.4) |

Longitudinal cohort | ZBI | ✓ | F2F at home 6 and 12 months | ||

| Ferrara et al., 2008 | Italy | 100 |

Male 59.4 (14.3) Female 56.1 (13.3) |

Retrospective | CBI | ✓ | F2F interviews at clinic | ||

| Fonereva et al., 2012 | US | 41 |

Carers 66.4 (7.8) Non‐carers 66.4 (7.9) |

Comparative CS | PSS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Personal digital Assistant (PDA) – collected 3–4 times during the day at random |

| Gallagher et al., 2011 | Ireland | 102 |

64.4 (14) 31–87 |

CS | RUD‐Lite; Carers' checklist; DIS; ZBI; Brief COPE; SES | ✓ | F2F questionnaire | ||

| Galvin et al., 2010 | US | 962 | 55.9 (12) | CS | ZBI; informal questions | ✓ | Internet‐based survey monkey | ||

| García‐Alberca et al., 2012 | Spain | 80 | 62.15 (10.4) | CS | ZBI; STAI‐S; CSI | ✓ | F2F interviews by authors (psychiatrist, neuropsychologist, neurologist) | ||

| Garre‐Olmo et al., 2016 | Spain | 306 | 61.2 (13.9) | CS multi centre | ZBI | ✓ | F2F at clinic visit by physician or psychologist | ||

| George & Steffen, 2014 | US | 53 | 62.61 (10.5) | Longitudinal cohort | CSE‐ R; SF‐12; RSCSE | ✓ | Phone interviews 12 and 18 months after intervention | ||

| Giebel & Sutcliffe, 2018 | England | 272 | 67 (12) | CS | AC‐QOL; GHQ – 12 | ✓ | F2F or hand/postal of questionnaires (research team attended carer support groups) | ||

| González‐Abraldes et al., 2013 | Spain | 33 |

57.6 (11.3) 35–82 |

CS | ZBI – Spanish version | ✓ | Postal | ||

| Gusi et al., 2009 | Spain | 110 |

Carers 60.6 (6.6) Non‐carers 62.6 (5.6) |

Comparative CS | SF‐12 | ✓ | F2F interview at home by a trained interviewer | ||

| Harmell et al., 2011 | US | 100 | 73.8 (8.1) | CS | CSE – 13 | ✓ | F2F interview at home | ||

| Haro et al., 2014 | France, Germany, UK | 1497 | 67.3 (12) | Prospective cohort (multi centre) | ZBI; EQ‐5D; RUD | ✓ | — | ||

| Holley & Mast, 2009 | US | 80 | 60.53 (12.7) | CS | MM‐CGI; AGS; ZBI‐SF | ✓ | F2F or postal, chosen by participant | ||

| Janssen et al., 2017 | Germany, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, UK | 453 | 66.4 (13.3) | Prospective cohort | RSS; SOC‐13; LOCBS; CarerQoL | ✓ | — | ||

| Kaizik et al., 2017 | Australia | 90 |

Children (mild) 32.2 (9.7) Spouses (mild) 62.5 (11) Children (severe) 30.7 (10.1) Spouses (severe) 61.9 (9) |

CS | ZBI; SNI; IBM; DASS‐21 | ✓ | Online survey | ||

| Kaufman et al., 2010 | US | 141 |

White 53.5 (11.8) African American 49.4 (11.9) |

CS | SPMSQ; ISEL; CCI; QoLI | ✓ | Telephone interviews by trained interviewers | ||

| Kowalska et al., 2017 | Poland | 58 |

54.7 (12.6) 21–78 |

CS | CBS; BSSS; SWLS | ✓ | F2F interview by psychologist | ||

| Lo Sterzo & Orgeta, 2017 | UK | 155 |

NS 26–82 |

CS | BIPQ; SOC | ✓ | Handed out then completed at home and returned to researcher | ||

| Luchsinger et al., 2015 | US | 139 | 59.29 (10.4) | CS | ZBI | ✓ | ✓ | — | |

| Majoni & Oremus, 2017 | Canada | 200 |

Retired 68–80 Employed 51–62 |

CS | EQ‐5D‐3L | ✓ | F2F by trained interviewers | ||

| Marziali et al., 2010 | Canada | 232 | NS | CS | EPQ‐R; RSCSE; MSPSS; HSQ‐12 | ✓ | F2F Interview from trained graduate and senior undergrad allied health students | ||

| Maseda et al., 2015 | Spain | 58 |

56.3 (1.5) 28–82 |

CS | ZBI – Spanish version; STAI | ✓ | Postal | ||

| Mausbach et al., 2011 | US | 108 | 73.88 (8) | CS | PANAS; PES‐AD; WCC‐R; CSE | ✓ | F2F at home | ||

| McLennon et al., 2011 | US | 84 |

73.3 (10.5) 49–96 |

CS | ZBI; SF‐36; FMTCG | ✓ | F2F at location and time chosen by carer ‐ by chief investigator | ||

| Melo et al., 2011 | Portugal | 109 | 67.0 (12.5) | CS | ZBI; NEO‐FFI ‐ Portuguese | ✓ | F2F in own home by trained interviewer | ||

| Melo et al., 2017 | Portugal | 98 | 66.8 (12.7) | CS | ZBI; NEO‐FFI – Portuguese | ✓ | F2F at home by trained nurse | ||

| Millenaar et al., 2016 | Holland | 328 |

YOD 59.02 (9.3) OOD 64.3 (12.4) |

Longitudinal cohort | SSCQ | ✓ |

NS 6 monthly follow‐ups over 2 years |

||

| Miller et al., 2010 | US | 421 |

63.0 (15.5) 22–89 |

CS | CDS; ZBI; | ✓ | — | ||

| Molinuevo & Hernández, 2011 | Spain | 249 | 59.9 (14.9) | Prospective multicentre study | SF‐36; ZBI | ✓ | — | ||

| Mougias et al., 2015 | Greece | 197 | 59.18 (13.9) | CS | ZBI | ✓ | — | ||

| O'Dwyer et al., 2013 | Australia and US | 120 | 58.76 (10.7) | CS | SES; SF‐12; ZBI; Brief COPE; BHS; ADKS; LOT; DSSI; SBQ‐R | ✓ | Online survey using LimeSurvey | ||

| O'Dwyer et al., 2016 | Australia | 566 |

Non‐suicidal 64.14 (11.3) Suicidal 56.60 (10.1) |

CS | SES; SF‐12; ZBI; Brief COPE; BHS; ADKS; LOT; DSSI; SBQ‐R; BRLI | ✓ | Online survey or in hard copy | ||

| Orgeta & Lo Sterzo, 2013 | UK | 170 |

62.42 (11.2) 24–88 |

CS | SOC; RSS; EQ‐VAS | ✓ | — | ||

| Papastavrou et al., 2015 | Greece | 208 | Reported in age brackets and % | Comparative CS | SCQ‐G; ZBI; | ✓ | F2F interviews by trained research assistant nurse graduates at home | ||

| Papastavrou et al., 2014 | Greece | 76 | Reported in age brackets and % | CS | QOL‐AD; ZBI | ✓ | — | ||

| Papastavrou et al., 2012 | Greece | 410 |

AD 56.8 (13.3) Schiz. 56 (15.0) Cancer 50.6 (13.4) |

Comparative CS | ZBI | ✓ | F2F interviews at home/clinic | ||

| Papastavrou et al., 2011 | Greece | 172 |

56.8 (13.4) 25–88 |

CS | ZBI; WCQ‐ Greek | ✓ | F2F in own home | ||

| Pertl et al., 2017 | Ireland | 253 |

69.64 (7.8) 50–90 |

CS | PSS‐4; SES; BIPAQ | ✓ | — | ||

| Quinn et al., 2012 | UK | 447 | 68 (12.5) | CS | MECS; PAI; CCS; MICS | ✓ | Postal | ||

| Raggi et al., 2015 | Italy | 73 |

64 (IQR 52–72) |

CS | CBI | ✓ | F2F in clinic | ||

| Raivio et al., 2015 | Finland | 728 |

PWB mod/good 77.7 (5.9) Poor 78.7 (7.1) |

CS | PWB | ✓ | Postal | ||

| Riedijk et al., 2008 and Riedijk et al., 2009 | Holland | 63 | 60.7 (9.6) | CS | SF‐36; SCQ; UCL; SSL; SCL‐90‐R | ✓ | Telephone interview by trained psychologists | ||

| Roche et al., 2015 | Holland | 46 | 59.11 | CS | CSI; QoL‐AD; Brief COPE | ✓ | Postal or handed out | ||

| Roepke et al., 2009 | US | 73 |

Carers 72.16 (9.6) Non‐carers 68.41 (6.7) |

CS | MFSI‐SF; PM | ✓ | — | ||

| Romero‐Moreno et al., 2011 | Spain | 167 | 59.88 | CS | RSCSE; ZBI; POMS | ✓ | F2F interview at social or health centre | ||

| Rosa et al., 2010 | Italy | 112 | 55 (10) | CS | CBI; STAI | ✓ | F2F interview | ||

| Rosness et al., 2011 | Norway | 49 |

AD 60.8 (5.3) Non‐AD 58.5 (8.3) |

CS | QoL‐AD – Norwegian Version | ✓ | ✓ | F2F interviews in memory clinic | |

| Salgado‐García et al., 2015 | US | 642 |

Smoker 57.02 (12.7) Non‐Smoker 62.84 (13.2) |

CS | ZBI; SF‐36; PAC; Brief RCOPE | ✓ | F2F interview at home | ||

| Savundranayagam & Orange, 2011 | Canada/US | 84 |

65.64 36–90 |

CS | PCI‐DAT | ✓ | — | ||

| Scholzel‐Dorenbos et al., 2009 | Netherlands | 97 | 73.5 (7.2) | CS | SEIQoL; ZBI; SRB; SPPIC | ✓ | F2F interviews – same person | ||

| Simonelli et al., 2008 | Italy | 100 | 55–85 | CS | CBI | ✓ | F2F interview at clinic | ||

| Skarupski et al., 2010 | US | 396 |

Blacks 56.9 (13.3) Whites 61.2 (13.6) |

Longitudinal cohort | Caregiver burden (Lawton); MSPSS; PA; CSS‐5 | ✓ | F2F or phone interviews 3 monthly over 4 years | ||

| Stensletten et al., 2016 | Norway | 97 |

79 65–96 |

CS | RSS; SPS – Norwegian; SOC | ✓ | Handed out in community clinic | ||

| Sun et al., 2010 | US | 141 | 52 | CS | CCI; QoLI; COPE | ✓ | Telephone surveys | ||

| Sutcliffe et al., 2017 | Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, UK | 1223 | 64.7 (13.4) | CS | ZBI; RUD | ✓ | F2F interviews | ||

| Svendsboe et al., 2016 | Norway | 186 | 74.9 (7.8) | CS | RSS | ✓ | F2F by clinician/nurse | ||

| Torrisi et al., 2017 | Italy | 27 | 76.2 (7.1) | CS | CBI | ✓ | F2F with psychologist | ||

|

Välimäki et al., 2009 and Välimäki et al., 2014 and Välimäki et al., 2016 |

Finland | 236 |

71.6 (7.2) (48–85) |

CS |

Study1: SOC; HRQoL‐VAS; GHQ; Study2: SOC Study3: HRQoL‐VAS |

✓ | F2F trained psychologist | ||

| von Känel et al., 2014 | US | 126 | 74.2 (7.9) | Longitudinal cohort | PANAS; PSQI | ✓ | F2F in‐home by trained research staff up to 4 years | ||

| Wawrziczny et al., 2017 | France | 150 | 67.2 (6.5) | CS | CRA; PFCNS; KSS; SF‐36; ISSB; FCCS; PDI; RSCSE | ✓ | F2F at home or clinic (Choice of carer) | ||

| Wilks & Croom, 2008 | US | 229 | 45 | CS | PSS; S‐PSSS; S‐RS | ✓ | Surveys done at conferences | ||

| Wilks et al., 2011 | US | 419 | 61 | CS | CITS; RS | ✓ | Postal | ||

| Zucchella et al., 2012 | Italy | 126 | 56.11 (12.4) | CS | CBI; COPE | ✓ | F2F interviews by clinicians | ||

| Zvěřová, 2014 | Czech Republic | 30 | NS | Longitudinal cohort | ZBI | ✓ | F2F interviews 0, 4, 8, months | ||

Abbreviations: AC‐QoL, Adult Carer Quality of Life; AD, Alzheimer's disease; ADKS, Alzheimer's Disease Knowledge Scale; AGS, Anticipatory Grief Scale; AQ, Attachment Questionnaire; ASA, Attachment Script Assessment; BEEGC‐20, Battery of Generalized Expectancies of Control Scales (also known as GECSB); BHS, Beck Hopelessness Scale; BIPAQ, Brief International Physical Activity Questionnaire; BIPQ, Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire; BRLI, Brief Reasons for Living Inventory; BSSS, Berlin Social Support Scale; CAMI, Carers' Assessment of Managing Index; CarerQoL, Care‐related Quality of Life scale; CBI, Caregiver Burden Inventory (Novak); CBS, Caregiver Burden Scale; CCI, Consequences of Care Index; CCS, Caregiver Competence Scale; CDS, Caregiving Distress Scale (from the NPI); CITS, Coping in Task Situations questionnaire; CMAI, Cohen‐Mansfield Agitation Inventory; COPE Index, Coping Orientations to Problems Experienced scale (Brief‐); CRA, Caregiver Reaction Assessment; CS, cross‐sectional; CSE, Coping Self‐efficacy scale; CSI, Coping Strategies Inventory; CSS, Caregiver Satisfaction Scale (6‐items, 5‐items); DASS 21, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale‐21; DIS, Desire to Institutionalize Scale; DSSI, Duke Social Support Index; EPQ‐R, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised; EQ‐5D, Euro‐Quality of life; EQ‐VAS, EuroQol‐Visual Analogue Scale; F2F, face‐to‐face; FCCS, Family Caregiver Conflict Scale; FMTCG, Finding Meaning Through Care‐Giving; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; GHQ‐12, General Health Questionnaire 12‐tem version; 30‐item version; GSS, Gilleard Strain Scale; HPLP, Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile; HSQ‐12, Health Status Questionnaire; IBM, Intimate Bond Measure; ISEL, Interpersonal Support Evaluation List; ISSB, Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviours; KSS, Knowledge of Services Scale; LEE, Level of Expressed Emotion scale; LOCBS, Locus Of Control of Behaviour Scale; LOT, Life Orientation Test; MECS, Motivations in Elder Care Scale; MFSI‐SF, Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory‐Short Form; MM‐CGI, Marwit‐Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory; MSPSS, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; MSQFOP, Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire For Older Persons; NEO‐FFI, NEO Five Factor Inventory (personality traits); NHP, Nottingham Health Profile; NS, not stated; OOD, Older Onset Dementia; PA, Positive affect; PAC, Positive Aspects of Caregiving; PAI, Positive Affect Index; PANAS, Positive And Negative Affect Scale; PCI‐DAT, Perception of Conversation Index – Dementia of the Alzheimer's Type; PCS, Preparedness for Caregiving Scale; PDI, Psychological Distress Index; PES‐AD, Pleasant Events Schedule ‐ Alzheimer's Disease; PFCNS, Planning for Future Care Needs Scale; PM, Pearlin Mastery scale; POMS, Profile Of Mood States (Tension Subscale); PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; PSSS, Perceived Social Support Scale (‐S, Short); PWB, Psychological Well‐ Being (scale); QoL‐AD, Quality of Life – Alzheimer's Disease; QoLI, Quality of Life Inventory; RCOPE, Religious Coping measure; RCSS, Revised Caregiving Satisfaction Scale; RS, Resilience Scale (S‐ short); RSCSE, Revised Scale for Caregiving Self‐Efficacy (Steffen); RSS, Relative Stress Scale; RUD, Resource Utilisation in Dementia (‐Lite); SACL, Stress Arousal CheckList; SBQ‐R, Suicidal Behaviours Questionnaire (−R, Revised); SCL‐90‐R, Revised Symptom CheckList; SCQ – G, Social Capital Questionnaire‐Greek version; SCQ, Sense of Competence Questionnaire (‐S, Short); SEIQoL, Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life; SES, Self‐Efficacy Scale (Fortinsky); SF‐12; SF‐36, Short Form 12; 36 questions; SNI, Social Network Index; SOC, Sense Of Coherence scale (−13 item); SOS, Significant Others Scale; SPMSQ, Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire; SPPIC, Self‐Perceived Pressure from Informal Care; SPS, Social Provision Scale; SRB, Self‐Rated Burden scale; SRRS, Social Readjustment Rating Scale; SSL, Social Support List; SSQRS, Social Support Questionnaire: Short form Revised; STAI, State–Trait Anxiety Inventory; SWLS, Satisfaction With Life Scale; TP, Timepoint; UCL, Utrecht Coping List; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; WCC, Ways of Coping Checklist (−R Revised); WCQ, Ways of Coping Questionnaire (−R Revised); YOD, Younger Onset Dementia; ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview (S‐ZBI Short version).

3.1.2. What carer‐reported measures were used in dementia research?

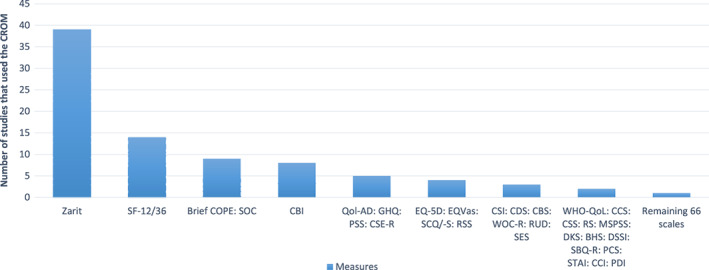

Ninety‐nine carer‐reported measures were administered in these studies. The five most commonly used scales were as follows: the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) (n = 39), the Short‐Form 12 or 36 (SF‐12/36) (n = 14), the Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced scale (Brief COPE) (n = 9), the Sense of Coherence scale (SOC) (n = 9) and the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) (n = 8). The remaining measures were utilised across one to five studies (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Number of studies for each carer measure

None of the measures identified have been used as a carer‐reported measure in a dementia CQR context.

3.1.3. What quality‐of‐life domains were addressed in identified measures?

The five most used measures were mapped across health and well‐being domains to identify similarities and differences (Table 2). Four measures collected data on emotional and social status, and three on physical and stress/burden status. Additional areas covered by these measures included coping, financial impact, motivation, pain, role functioning and time dependence. Most of these areas were covered in the remaining measures, which ranged from stress‐related, to personality coping, to emotional, mood and sleep scales.

TABLE 2.

Health domains covered in the five most used carer‐reported measures (from Scoping review)

| CROM | Main focus | Description | Validation | Emotional | Physical | Social | Stress /Burden | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZBI | Carer Burden | 22‐item self‐report. Rated from 0 (never) to 4 (nearly always) summed to an overall score. A score of ≤20 indicates little or no burden, mild–moderate burden 21–40, moderate–severe burden 41–60, and 61–88 indicates severe burden | High internal consistency (a = 0.85) and construct validity with carers of elderly people with dementia (Van Durme et al., 2012). | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Coping Financial impact |

| SF‐12/SF‐36 | Health status | 12 Items. Scorings range from yes/no, to limited a lot/limited a little, all the time/none of the time, to not all/ extremely. Summative scores are created and compared with normative data. | Reliability for the US population was stated as 0.89, and the UK as 0.88 (Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1996). | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Pain Role functioning |

|

| Brief COPE | Coping style | 28‐item self‐reported scale comprising of 14 subscales with two domains in each. Scoring incorporates a Likert scale from 1 (not doing it at all) to 4 (doing it a lot). | Moderate to high psychometric properties have previously been reported with carers of people living with dementia (internal validity a = 0.72, 0.84, 0.75, and test–retest reliability emotion‐focussed r = 0.58, problem‐focussed r = 0.72, dysfunctional r = 0.68; p < 0.001) (C. Cooper et al., 2008). | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| SOC | Purpose/Meaning in life | Self‐reported 29‐item scale. Scoring is from 1 (never have this feeling) to 7 (always have this feeling), with a higher overall score (summed and ranging from 29 to 203 points) indicating stronger coherence. | High reliability has been reported with Cronbach a = 0.83 (Orgeta & Sterzo, 2013). A shorter version SOC‐13 scale has been developed (Antonovsky, 1987) where summative scores range from 13 to 91 points with a higher score indicating a more successful adaptation to a stressful situation (Janssen et al., 2017). |

Comprehensibility (cognitive) Manageability (behavioural) Meaningfulness (motivational) |

||||

| CBI | Carer Burden | Self‐reported 24‐item scale of burden. Scoring incorporates a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never/not at all disruptive) to 4 (nearly always/very disruptive). | Internal consistency reliability is reported with a Cronbach a = 0.85 (factors 1,2), 0.86, 0.73 and 0.77 (factors 3,4,5) with all factors displaying equal importance (Novak & Guest, 1989). | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Time dependence |

Abbreviations: Brief COPE Index, Coping Orientations to Problems Experienced scale; CBI, Caregiver Burden Inventory (Novak); SF‐12, Short Form 12; SF‐36, Short Form 36; SOC, Sense Of Coherence scale; ZBI, Zarit Burden Interview.

3.1.4. How were the measures administered?

The mode of delivery for the identified carer‐reported measures varied from face‐to‐face (n = 50), to postal (n = 11), telephone (n = 8) and online (n = 5). Thirteen did not state the collection method and four used more than one method.

3.2. Phase 2: A descriptive qualitative study

3.2.1. Participant characteristics

Four focus groups were conducted with a total of 15 participants (focus group 1: n = 2; focus group 2: n = 3; focus group 3: n = 7; focus group 4: n = 3). Most of the participants were female (n = 10) and lived in metropolitan Melbourne (n = 8). Thirteen participants reported being the spouse or partner of the person living with dementia, and of them, 12 lived at home with the person with dementia and the remaining carer's spouse lived in a residential aged care facility. The other two participants were adult children caring for a parent with dementia who lived in residential aged care facilities.

3.2.2. Carer Experience Scale

Three groups (i.e. Groups 1 to 3) reviewed the CES. Participants liked the measure because it was brief and easy to complete:

It's very easy…it's more comprehensive…this one gives you an opportunity to add anything.

They also liked the inclusion of a question on activities they enjoy outside their caring role. They commented that this measure can be improved by a more personal approach, for example, the use of ‘I' instead of ‘You’ statements.

3.2.3. CaSPUN

Two groups (i.e. Groups 2 and 3) reviewed the CaSPUN. The overall comment was that the measure was too long and that the wording required significant revision:

By the time somebody gets to 35 questions, they are going to be exhausted, it's a bit long.

I just find the language up the top, like, “No unmet need is currently unmet”. I find I never like having to answer things in the negative… You finish up with a double negative and you are not sure what you have answered.

3.2.4. Zarit Burden Interview

Two groups (i.e. Groups 3 and 4) reviewed the ZBI. The ZBI had the most positive feedback. Participants found it to be clearer and more comprehensive than the other measures presented in the focus groups. They also felt that the questions helped to capture the changes in their circumstances:

These sorts of questions change depending on the stage you are at. So, in my case I've seen these questions before when [person they care for] was at home. Now he's not at home, he's in care [a residential aged care]. It becomes a totally different set of answers but yes, they are all relevant.

Participants did not like the use of the word ‘burden’ in the survey title and suggested using a more neutral term:

Dementia Questionnaire for Carers…Yeah, it's loaded you know, “Burden” … I like the Zarit with a different title.

3.2.5. Short‐Form 12 or 36

One group (i.e. Group 4) reviewed the SF‐12/36. The group felt that it was not a preferred tool for carers because it did not ask the right questions and was difficult to follow:

This would not be asking the questions that I would want to be asked…I think the other surveys get more information than this one would … This is difficult to follow and read and to work with using underlines and so on. There's nowhere where you can write additional stuff, additional “Do you have any notes to add”.

3.2.6. Brief COPE

One group (i.e. Group 4) reviewed the Brief COPE. Participants felt that the response options were unclear in terms of the subjective interpretation of the terms and that positively framed responses were easier to understand:

We've got the first scale questions, the one to four, “I haven't been doing this at all” is clear. “I've been doing this a little bit” and “a medium amount” aren't quite as clear. Maybe “I do this sometimes” or “I do this often” and then “I do this all the time” might be a better way of putting that. Do not have the negative.

Participants also suggested using present tense in the sentences so participants can relate better to the questions:

I would make it more in the present, like “I return to work to just take my mind off things” and make the person think about it more. Like I'm doing…or “currently”.

3.2.7. Carer outcomes missing from the measures

Participants were asked to identify outcomes that were important to them but missing from the pretend measures. Participants proposed outcomes in three domains: (1) carer's social needs, (2) carer health needs and (3) access to and use of services for people with dementia and their carers (see Table 3). Carers also felt that it was important to include open‐ended questions to enable the opportunity to share additional information if desired.

TABLE 3.

Additional domains suggested by carers (from Qualitative Study)

| Domain | Proposed topic | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Carer social needs |

|

|

| Carer health needs |

|

|

| Services for people with dementia and their carers |

|

|

4. DISCUSSION

Informal carers play a vital role in supporting people with dementia and are integral to the quality of life of people with dementia. 3 , 4 , 6 , 7 , 9 , 10 Given this, it is important to include carer‐reported measures in a dementia CQR, where the key objective is to monitor the quality of care and service and to drive quality improvement initiatives. This paper reports the results of a systematic scoping review and a descriptive qualitative study that were conducted to inform the identification and/or development of carer‐reported measures for a dementia CQR.

This scoping review included 88 studies, in which 99 carer‐reported measures were identified. None had been utilised in the context of a dementia CQR. Most of the identified measures were administered via face‐to‐face, followed by postal and phone administration. The five most used scales reported included the ZBI, the SF‐12/36, the Brief COPE, the SOC, and the CBI, with four collecting data on emotional and social health and three on physical health and stress/burden.

The qualitative study explored the acceptability of five carer measures, including three measures identified from the review (i.e. the ZBI, the SF‐12/36 and the Brief COPE) and two measures used in CQRs for other diseases (i.e. the CaSPUN and the CES). Of the five measures, carers preferred the ZBI and the CES. The ZBI was preferred because it was clear and comprehensive, and the questions helped to capture the changes in carers' circumstances. However, carers did not like the term ‘burden’ in the title and suggested using a more neutral term. The CES was preferred because it was brief and easy to complete, and it included a question on activities enjoyed outside their caring role. However, carers suggested using a more personal approach in the questions, such as using ‘I' instead of ‘You’ in the statements. Carers did not like the remaining three measures (i.e. the SF‐12/36, the Brief COPE and the CaSPUN) because the measures were too long, did not ask the right questions, or were difficult to complete. Overall, carers preferred a brief measure that captured activities outside of the caring roles, could be used to understand changes in carers' circumstances and included open‐ended questions for carers to provide additional information on carer outcomes and experiences.

Carers also felt that questions relating to their social and health needs and service access/usage were important to understand the impact of caregiving on carers' lives, but these were missing in some carer measures. Such questions are important to understand the impact of care and services utilisation among patients and carers and their experience of care and services, allowing a more complete picture of the patients' and carers' perceptions of both the process and the outcomes of care and services. 23 , 50

Taken together, the results from the scoping review and the qualitative study suggested that the ZBI and the CES are two carer‐reported measures that could potentially be used in a dementia CQR; however, adaption and further research exploring feasibility and acceptability via focus groups, interviews or surveys of when and how the carer‐reported measure is administered is required before being used in a dementia CQR.

4.1. Limitations and strengths

Our study has addressed an important gap in the literature in what carer‐reported measures could be implemented into dementia CQRs. The combination of a scoping review and a qualitative study provided information based on existing research evidence and reflected the end‐user's perspective.

Nonetheless, the results of this study should be considered in the light of its limitations. First, we have conducted only a scoping review, which did not include specific assessment of the quality of reviewed studies. Second, different numbers of measures were reviewed across the four focus groups and two measures (i.e. SF‐12/36 and Brief COPE) were reviewed by only one focus group. This meant that there was limited feedback from the two measures, and future studies need to consider having relatively equal number of participants and measures across focus groups to ensure that all measures had similar opportunities for consumer feedback. Third, the number of participants in the focus groups was relatively small; however, analysis indicated that 90% of themes from a study are evident in three to six focus groups. 51 The focus groups did not explore the needs of carers for people with different types of dementia or the needs of groups such as people from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities or Culturally and Linguistically Diverse communities. Future research leveraging the dementia registry data can identify population groups at different sites to inform sampling for interviews and focus groups to explore carer needs for these specific groups. Of the two preferred measures, the ZBI has undergone linguistic validation for several languages 52 ; however, the CES has not been validated in languages other than in English. 53

5. CONCLUSIONS

There has been a growing interest in and use of CQRs around the globe to drive continuous quality improvements in clinical care. The inclusion of carer‐reported measures is important for a dementia CQR to reflect carers' perspectives on the quality and outcomes of care and services. Our scoping review identified nearly 100 carer‐reported measures from earlier dementia research, but none have been used in a registry context. Our qualitative study found that carers prefer brief measures that include questions related to their social and health needs and use of services. Additionally, the measures need to reflect changes in carers' circumstances, take a personal approach when asking questions and include an open‐ended question.

Our studies suggest that the ZBI and the CES are two carer‐reported measures that potentially could be used in a dementia CQR; however, adaption and further exploration is required. Future carer‐reported measures for a dementia registry need to include both outcome and experience measures to help present a more complete picture of carers' perceptions on the process and outcomes of care and services.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The funder had no role in the conduct of this work. Open access publishing facilitated by Monash University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Monash University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest declared.

Lin X, Ward SA, Pritchard E, et al. Carer‐reported measures for a dementia registry: A systematic scoping review and a qualitative study. Australas J Ageing. 2023;42:34‐52. doi: 10.1111/ajag.13148

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . Dementia – Key facts. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/dementia

- 3. Toot S, Swinson T, Devine M, Challis D, Orrell M. Causes of nursing home placement for older people with dementia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(2):195‐208. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Belger M, Haro JM, Reed C, et al. Determinants of time to institutionalisation and related healthcare and societal costs in a community‐based cohort of patients with Alzheimer's disease dementia. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(3):343‐355. doi: 10.1007/s10198-018-1001-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cepoiu‐Martin M, Tam‐Tham H, Patten S, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB. Predictors of long‐term care placement in persons with dementia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(11):1151‐1171. doi: 10.1002/gps.4449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673‐2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng S. Dementia caregiver burden: a research update and critical analysis. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(9):64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ducharme F, Lachance L, Kergoat M‐J, Coulombe R, Antoine P, Pasquier F. A comparative descriptive study of characteristics of early‐ and late‐onset dementia family caregivers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31(1):48‐56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wimo A, Gauthier S, Prince M. on behalf of ADI’s Medical Scientific Advisory Panel and the Alzheimer’s Disease International publications team . Global estimates of informal care. Alzheimer's disease international (ADI) and Karolinska Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lindeza P, Rodrigues M, Costa J, Guerreiro M, Rosa MM. Impact of dementia on informal care: a systematic review of family caregivers' perceptions. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;bmjspcare‐2020‐002242. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carbonneau H, Caron C, Desrosiers J. Development of a conceptual framework of positive aspects of caregiving in dementia. Dementia. 2010;9(3):327‐353. doi: 10.1177/1471301210375316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Quinn C, Toms G. Influence of positive aspects of dementia caregiving on caregivers' well‐being: a systematic review. Gerontologist. 2019;59(5):e584‐e596. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gilhooly KJ, Gilhooly MLM, Sullivan MP, et al. A meta‐review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):106. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alzheimer's Association . 2020 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(3):391‐460. doi: 10.1002/alz.12068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brodaty H, Donkin M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(2):217‐228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fazio S, Pace D, Maslow K, Zimmerman S, Kallmyer B. Alzheimer's Association dementia care practice recommendations. Gerontologist. 2018;58(Suppl_1):S1‐S9. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pink J, O'Brien J, Robinson L, Longson D. Dementia: assessment, management and support: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2018;361:k2438. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cations M, Lang C, Ward SA, et al. Using data linkage for national surveillance of clinical quality indicators for dementia care among Australian aged care users. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):10674. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89646-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . Framework for Australian clinical quality registries. ACSQHC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krysinska K, Sachdev PS, Breitner J, Kivipelto M, Kukull W, Brodaty H. Dementia registries around the globe and their applications: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(9):1031‐1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin X, Wallis K, Ward SA, Brodaty H, Sachdev PS, Naismith SL, Krysinska K, McNeil J, Rowe CC, Ahern S. The protocol of a clinical quality registry for dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI): the Australian Dementia Network (ADNeT) Registry. BMC geriatrics. 2020;20(1):330. 10.1186/s12877-020-01741-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ruseckaite R, Maharaj AD, Krysinska K, Dean J, Ahern S. Developing a preliminary conceptual framework for guidelines on inclusion of patient reported‐outcome measures (PROMs) in clinical quality registries. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2019;10:355‐372. doi: 10.2147/prom.S229569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wilcox N, McNeil JJ. Clinical quality registries have the potential to drive improvements in the appropriateness of care. Med J Aust. 2016;205(S10):S21‐S26. doi: 10.5694/mja15.00921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blood Z, Tran A, Caleo L, et al. Implementation of patient‐reported outcome measures and patient‐reported experience measures in melanoma clinical quality registries: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e040751. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williams K, Sansoni J, Morris D, Grootemaat P, Thompson C. Patient‐reported outcome measures: Literature review. ACSQHC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dow J, Robinson J, Robalino S, Finch T, McColl E, Robinson L. How best to assess quality of life in informal carers of people with dementia; A systematic review of existing outcome measures. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0193398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cunningham NA, Cunningham TR, Roberston JM. Understanding and measuring the wellbeing of carers of people with Dementia. Gerontologist. 2018;59(5):e552‐e564. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Page TE, Farina N, Brown A, et al. Instruments measuring the disease‐specific quality of life of family carers of people with neurodegenerative diseases: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e013611. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19‐32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim H, Sefcik JS, Bradway C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: a systematic review. Res Nurs Health. 2017;40(1):23‐42. doi: 10.1002/nur.21768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hobbs KM, Hunt GE, Lo SK, Wain G. Assessing unmet supportive care needs in partners of cancer survivors: the development and evaluation of the Cancer Survivors' Partners Unmet Needs measure (CaSPUN). Psychooncology. 2007;16(9):805‐813. doi: 10.1002/pon.1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rand S, Malley J, Vadean F, Forder J. Measuring the outcomes of long‐term care for unpaid carers: comparing the ASCOT‐Carer, Carer Experience Scale and EQ‐5D‐3 L. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):184. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1254-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Charters E. The use of think‐aloud methods in qualitative research: an introduction to think‐aloud methods. Brock Educ J. 2003;12(2):68‐82. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cooper C, Katona C, Orrell M, Livingston G. Coping strategies, anxiety and depression in caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(9):929‐936. doi: 10.1002/gps.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cooper C, Owens C, Katona C, Livingston G. Attachment style and anxiety in carers of people with Alzheimer's disease: results from the LASER‐AD study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(3):494‐507. doi: 10.1017/S104161020700645X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Riedijk S, Duivenvoorden H, Rosso S, Van Swieten J, Niermeijer M, Tibben A. Frontotemporal dementia: change of familial caregiver burden and partner relation in a Dutch cohort of 63 patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26(5):398‐406. doi: 10.1159/000164276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Riedijk S, Duivenvoorden H, Van Swieten J, Niermeijer M, Tibben A. Sense of competence in a Dutch sample of informal caregivers of frontotemporal dementia patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27(4):337‐343. doi: 10.1159/000207447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Välimäki T, Martikainen J, Hongisto K, et al. Decreasing sense of coherence and its determinants in spousal caregivers of persons with mild Alzheimer's disease in three year follow‐up: ALSOVA study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(7):1211‐1220. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Välimäki T, Martikainen J, Hongisto K, Väätäinen S, Sintonen H, Koivisto A. Impact of Alzheimer's disease on the family caregiver's long‐term quality of life: results from an ALSOVA follow‐up study. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(3):687‐697. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1100-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Välimäki TH, Vehviläinen‐Julkunen KM, Pietilä A‐MK, Pirttilä TA. Caregiver depression is associated with a low sense of coherence and health‐related quality of life. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(6):799‐807. doi: 10.1080/13607860903046487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bakker C, de Vugt ME, van Vliet D, et al. Unmet needs and health‐related quality of life in young‐onset dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(11):1121‐1130. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McLennon SM, Habermann B, Rice M. Finding meaning as a mediator of burden on the health of caregivers of spouses with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(4):522‐530. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.543656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brodaty H, Woodward M, Boundy K, Ames D, Balshaw R. Prevalence and predictors of burden in caregivers of people with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(8):756‐765. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Armstrong N, Schupf N, Grafman J, Huey ED. Caregiver burden in frontotemporal degeneration and corticobasal syndrome. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013;36(5–6):310‐318. doi: 10.1159/000351670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Diehl‐Schmid J, Schmidt E‐M, Nunnemann S, et al. Caregiver burden and needs in frontotemporal dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2013;26(4):221‐229. doi: 10.1177/0891988713498467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Luchsinger JA, Tipiani D, Torres‐Patiño G, et al. Characteristics and mental health of hispanic dementia caregivers in New York City. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2015;30(6):584‐590. doi: 10.1177/1533317514568340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rosness TA, Mjørud M, Engedal K. Quality of life and depression in carers of patients with early onset dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(3):299‐306. doi: 10.1080/13607861003713224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bednarek A, Mojs E, Krawczyk‐Wasielewska A, et al. Correlation between depression and burden observed in informal caregivers of people suffering from dementia with time spent on caregiving and dementia severity. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(1):59‐63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fonareva I, Amen AM, Ellingson RM, Oken BS. Differences in stress‐related ratings between research center and home environments in dementia caregivers using ecological momentary assessment. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(1):90‐98. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kingsley C, Patel S. Patient‐reported outcome measures and patient‐reported experience measures. BJA Educ. 2017;17(4):137‐144. doi: 10.1093/bjaed/mkw060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Guest G, Namey E, McKenna K. How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods. 2016;29(1):3‐22. [Google Scholar]

- 52. ePROVIDE . Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI). Accessed September 20, 2022. https://eprovide.mapi‐trust.org/instruments/zarit‐burden‐interview

- 53. University of Birmingham . The Carer Experience Scale. Accessed September 20, 2022. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/activity/mds/projects/haps/he/icecap/ces/index.aspx

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.