Abstract

The impact of circadian rhythms on cardiovascular function and disease development is well established, with numerous studies in genetically modified animals emphasizing the circadian molecular clock’s significance in the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of myocardial ischemia and heart failure progression. However, translational pre-clinical studies targeting the hearts circadian biology are just now emerging and are leading to the development of a novel field of medicine termed Circadian Medicine. In this review we explore circadian molecular mechanisms and novel therapies including i) intense light, ii) small molecules modulating the circadian mechanism, and iii) chronotherapies such as cardiovascular drugs and meal timings. These promise significant clinical translation in circadian medicine for cardiovascular disease. Additionally, we address the differential functioning of the circadian mechanism in males versus females, emphasizing considering iv) biological sex, gender, and aging in circadian therapies for cardiovascular disease.

Subject Terms: Basic Science Research, Coronary Artery Disease, Genetically Altered and Transgenic Models, Myocardial Infarction

Keywords: Circadian Medicine, Myocardial Infarction, Heart Failure, Cardiovascular Disease, Chronotherapy, Nuclear Receptor Drug Targets, Light Therapy, Rest, Sex, Gender

Introduction

Biologist Franz Halberg coined the term “circadian rhythms” in 1959, defining these as approximately 24-hour biological cycles that regulate daily processes and behaviors in living organisms. He noted that these rhythms profoundly influence, or sway the balance, between health and diseases, affecting physiologic functions, disease susceptibility, and overall well-being. Despite being recognized over 60 years ago and playing a crucial role in our lives, research into therapies targeting circadian rhythms, especially in improving cardiovascular health and addressing associated diseases in clinical cardiology, has only recently gained momentum.1–8

Circadian therapeutic development is driven by genetic studies in animals. While bridging the gap between animals (mainly rodents) and human circadian rhythm functions has been challenging, recent studies translating circadian mechanisms into therapeutic applications provide evidence that animal studies offer a valuable platform for preclinical circadian research,2, 9–16

In the realm of cardiovascular health, early studies in humans revealed a profound circadian pattern in the timing of onset of acute myocardial ischemia (MI), with a higher incidence in the morning compared to the evening.17 This trend extended to the timing of onset of other adverse cardiovascular events also occurring predominantly in the early morning hours, including unstable angina, sudden death, stroke, ventricular arrhythmias, cardiogenic shock, aortic aneurysm rupture, stent thrombosis, and transient MI.4, 6–8, 17–22 Additionally, clinical studies found that MI is more severe in the early morning compared to other times of the day.23–25 While heart failure (HF) does not follow a circadian occurrence, there is ample evidence revealing a significant role in the disruption of circadian biology in its progression.26 Indeed, the impact of circadian rhythm disruption is commonly experienced due to shift work or jet lag. Studies reveal that ischemic heart disease incidence is higher in shift workers versus normal daytime workers, independent of life style factors like smoking, or age, supporting the notion that maintaining a normal circadian rhythms or sleep pattern is important for cardiovascular health, as have been extensively reviewed.3, 6–8 Moreover, in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) undergoing cardiac transplantation, a molecular change in the DCM hearts based on the ratio of circadian mechanism factors REV-ERB and BMAL1 correlated with imaging findings of lower left ventricular end-diastolic diameter and a higher likelihood of mitral regurgitation.27 A summary of these ideas is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Impact of circadian rhythms on heart ischemia or heart failure.

Data from humans indicates the role of circadian rhythms in the occurrence or severity of MI or HF. Animal studies demonstrate the role of circadian core proteins during MI or HF (BMAL1, REV-ERB, PER2) using gene targeted mice. Data from mice suggest that targeting those proteins could help to treat MI or HF progression (Circadian Medicine); mouse icon = mouse studies, manikin icon = human studies) Illustration credit: Sceyence Studios.

The terms “circadian” and “diurnal” are often used interchangeably in the literature, but we aim to use more precise terminology in this review. “Circadian” is used when discussion conditions in animals or humans that examine natural biological responses without light cues (Zeitgebers). It also refers to experimental studies in animals where components of the molecular clock mechanism are genetically disrupted, although the subsequent research is generally undertaken under light and dark conditions, unless otherwise noted. On the other hand, “diurnal” refers to a regular 24-hour light and dark day, aligning with the typical human environment. “Nocturnal” is used for rodent studies, active during the dark and resting in the light, with daily behavior opposite to humans. “Circadian disruption” or “circadian desynchrony” describes studies where innate circadian biology is disturbed, either through genetic manipulations or changes in the 24-hour light-dark environment. Despite potential confusion, the key conclusions from these studies are considered valid and reproducible. This review relies on expert work in the field, and readers are directed to the specific studies for in-depth information. The 2017 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology recognized core circadian mechanisms, and the forefront of this field now applies to clinical medicine. The cited studies focus on cutting edge cardiovascular-circadian research and state-of-the-art translational strategies to enhance cardiovascular health and human longevity.

This review will begin with an introduction to the circadian clockwork mechanism in the heart, and then explore four key areas demonstrating how circadian biology influences heart disease. Specifically, it will focus on MI reperfusion injury leading to HF, covering i) the circadian-hypoxia link leading to intense light therapy, ii) the impact of drugging the circadian mechanism with novel small molecules, iii) the exploration of chronotherapies to enhance disease outcomes, and iv) considerations on biological sex, gender, and aging in circadian therapies for cardiovascular disease.

A. The Circadian Clockwork Mechanism in the Cardiovascular System

Circadian Influences on Cardiovascular Physiology: Understanding Daily Patterns and Pathophysiological Implications:

Circadian rhythms significantly influence how our cardiovascular system operates. For example, blood pressure28 and heart rate29 – follow a distinct daily pattern, peaking during the day and dipping at night. When these patterns go awry, it often leads to worse cardiovascular disease outcomes such as MI or HF. In humans, heart rate differences between day and night were not seen in patients with HF, unlike their healthy counterparts.30 This may be putting them at a higher risk for sudden cardiac death and all-cause mortality.30, 31 Indeed, low heart rate variability has been associated with a risk of arrhythmias and arrhythmic death, unstable angina, MI, progression of HF, and atherosclerosis.32 However, the precise underlying molecular reasons are not clear, in particular because of the integrated nature of our physiology.33, 34 For instance, while the daily cycle of circulating catecholamines35 might contribute to the day/night pattern of blood pressure, this is likely a multifaceted process that includes but is not limited to contributory circadian functions of the endothelium,36–40 smooth muscles,41, 42 kidney43, adipose tissue, liver, autonomic system, and microbiome.34, 44, 45

Changes in plasma levels of activators and inhibitors of coagulation and fibrinolysis throughout the day lead to morning hypercoagulability46 which may contribute to the higher incidences of myocardial stent thrombosis in the morning hours.47 Studies have shown how morning variations in the activity of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 activity reduce fibrinolytic activity in both healthy individuals and those with coronary artery disease.48 Diurnal variation of endothelial function is another factor; studies in healthy human subjects found that brachial artery flow–mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilation is blunted in the early morning hours.49

Unveiling the Circadian Mechanism in the Heart: Insights from Animal Studies:

Initial investigations into the presence of an internal circadian mechanism in the heart, underlying cardiac physiology and pathology, used rat hearts and revealed circadian patterns of expression of early known core mechanism genes.50 These genes, in turn, regulate the induction of various output genes, particularly those in metabolic pathways.50, 51 Studies on isolated cardiomyocytes further confirmed the time-of-day dependency of metabolic pathways.52, 53 Expanding on these findings, microarray technology was used to examine the global 24-hour gene expression patterns in murine hearts. It was found that approximately 13% of rodent heart genes exhibit diurnal54 or circadian55 patterns, with some genes peaking in the animal’s day, and others at night. These circadian-regulated output genes play crucial roles in physiologic processes such as transcription, translation, cardiac growth, renewal, and metabolism. Further analyses in murine models with heart-specific genetic disruption of Clock (CCM)56 or Bmal1 (CBK),57 explored the global daily rhythmicity of the circadian mechanism and output genes. Subsequent characterization of the day/night proteome of the murine heart, using global proteomic approaches, identified critical functional pathways under daily rhythmic regulation, with a focus on metabolism, and contractility.22, 58 Additional studies confirmed that these 24-hour oscillations of core circadian genes, and output genes also occur in the human heart.59 Collectively, these findings support the existence of a core circadian mechanism within heart cells, mirroring patterns observed in other organs. They shed light on how this system critically regulates the structure and function of the heart.

Deciphering Circadian Mechanism in Cardiovascular Health: Insights from Transgenic Models and Human Correlations:

i). Light as a Zeitgeber:

Light acts as a critical regulator of our internal clock, serving as a primary factor in synchronizing our circadian rhythms.60, 61 Known as a dominant ‘Zeitgeber’ or time giver, sunlight or daily light is essential for this synchronization process. Without it, our circadian biology would revert to its internal free-running status, slightly deviating from the 24-hour day. Zeitgebers like light synchronize our internal circadian mechanism with the environment. When light hits our eyes, retinal melanopsin receptors are activated, and signals are transmitted to the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) within the hypothalamus, and interact with the molecular clockwork.62 63 Notably, melanopsin receptors are particularly sensitive to blue light, meaning exposure to this type of light can shift our circadian phase, primarily in a melanopsin-dependent manner.64 It’s worth noting that the human circadian system typically responds to light intensities higher than 180 LUX,65 with more intense light (>10,000 LUX) showing the most significant effect on aligning our internal clock.

ii). Entrainment and Heart Health:

In animal studies, disruptions to the natural 24-hour light-dark cycle have revealed significant impacts on heart function. For instance, the +/tau hamsters66, whose internal clock operates on a 22-hour schedule within a 24-hour day-night cycle, develop dilated cardiomyopathy and renal disease when their internal rhythm mismatches the external environment.66 However, when these hamsters live in a 22-hour environment that matches their internal clock, they maintain stable rhythms and do not develop cardio-renal disease.66 Surprisingly, the homozygote tau/tau hamsters with a 20-hour internal circadian mechanism are unable to synchronize with the 24-hour external cycle and are protected from heart disease.66 In a murine model of transaortic constriction (TAC) induced pressure overload in a rhythm-disruptive 20-hour versus 24-hour environment, echocardiography studies reveal increased left ventricular end-systolic and -diastolic dimensions and reduced contractility in rhythm-disturbed animals; restoration of normal diurnal schedules effective reversed the pathology.67 In a murine MI study, diurnal rhythm disruption immediately after MI, recapitulating some of the circadian disruption as might be experienced in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), impaired healing and exacerbated maladaptive cardiac remodeling.68 In a study in cardiomyopathic Syrian hamsters, continuous shifting of the light/dark cycle by a 12 hour phase shift each week significantly decreased life span.69 On the contrary, circadian amplitude enhancement via exercise or intense light demonstrates reduced MI and reperfusion injury.13

Many of these observations in animal studies correlate with findings of cardiovascular disease in humans. For example, elegant studies by Scheer and colleagues demonstrated experimentally that circadian misalignment in healthy humans affects endocrine, metabolic, and autonomic predictions of cardiovascular and other disease risks.70 Moreover, altering the diurnal cycle through shift work alters sympathetic and vagal autonomic activity,71 and diurnal BP profiles72. Collectively, physiology impaired by an altered light-dark cycle may help to explain the epidemiological findings in shift worker cohorts of increased risk of ischemic heart disease,73 coronary heart disease,74, 75 MI,76 atherosclerosis,77 and hypertension.78

Thus, synchronizing between the external environment and the internal circadian mechanism via primary zeitgebers such as the light-dark cycles in important for our physiology, and especially the cardiovascular system. There are many excellent reviews.3, 6–8, 21, 22, 79–82 Next, we detail several best-known components of the internal molecular circadian mechanism, at least with regards to cardiovascular research. These components are critical factors in the circadian mechanism transcription/translation feedback loop that cycles every ~24 in virtually all our cells including the heart and coordinates rhythmic cellular function and physiology.

iii). CLOCK and its role in the heart:

CLOCK is a core component of the positive limb of the molecular circadian mechanism. It was initially identified in 1994, by using N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea mutagenesis in mice.83 These experiments led to the discovery of the canonical ClockΔ19/Δ19 mouse, which has a longer (27.3 hour) free-running circadian period as compared to heterozygotes (24.4 hour) or wild type littermates (23.3 hour). The mutation, a single A to T transversion, was mapped to a single gene called Clock, a member of the basic helix-loop-helix family of transcription factors. The mutation occurs intron 19 and leads to alternative splicing and deletion of exon 19, resulting in a 51 amino acid deletion and consequent reduced function in the CLOCK protein.84

Studies using these mice have revealed that the circadian factor CLOCK is pivotal in cardiovascular health and disease, such as through the regulation of inflammatory pathways. For example, ClockΔ19/Δ19 mice show disrupted diurnal cycling of MI-response genes in the heart.85 Importantly, this affects the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the infarcted heart, impairing inflammatory responses crucial for cardiac repair post-MI.68 Altered inflammatory responses can exacerbate maladaptive cardiac remodeling, worsen cardiac repair, and lead to HF.68, 86 Thus CLOCK plays an important role in regulating immune responses underlying cardio protection.

ClockΔ19/Δ19 mice have been used to demonstrate that CLOCK’s role extends to other important pathways as well, such as vascular myogenic tone regulation,39 and modulation of processes like autophagy/mitophagy,87 and gut microbiome composition,44 all of which play critical roles in post-MI cardiac repair and the progression of HF.

Interestingly, despite CLOCK’s involvement in obesity and metabolic functions, ClockΔ19/Δ19 mice resist developing heart disease, even when challenged with a chronic high-fat diet88. The ClockΔ19/Δ19 mice have also been used to examine the integrated nature of CLOCK in other organs affecting the heart post-MI and in HF. For example, CLOCK influences neuron morphology and function, potentially affecting neurobiological adaptations in HF and associated depression40. Additionally, CLOCK might link to mental health factors such as alcohol consumption,89 and thus could further affect the pathophysiology of HF.

A second prominent murine model for studying CLOCK is the dominant negative Clock mutation directly in the heart (cardiomyocyte-specific circadian clock mutant, CCM).52, 56 Experiments using these animals have been especially used to highlight CLOCK’s role in regulating cardiometabolic health. Loss of CLOCK function in these mice alters diurnal gene56 and protein58 expression in the heart, and impacts fatty acid response during fasting.52 The CCM mice also have increased myocardial oxygen consumption and fatty acid oxidation rates but decreased cardiac efficiency.90 These mice also show altered responses to chronic high-fat diets, resulting in cardiac steatosis due in part to disrupted hormone-sensitive lipase activity.91 There are several excellent reviews profiling these and additional studies revealing the critical role of CLOCK in CCM mice in cardiac metabolism and pathology.22, 92–95

iv). BMAL1 and its role in the heart:

BMAL1 is also a core component of the positive arm of the mammalian circadian mechanism. BMAL1, first discovered in 1998 as an orphan bHLH-PAS transcription factor, heterodimerizes with CLOCK to form a transcriptionally active complex.96 CLOCK and BMAL1 bind to enhancer (E) box promoter elements to drive transcription of the circadian factors involved in the negative arm of the mechanism.97

Many investigations using various genetic strategies have explored the significance of BMAL1, a pivotal factor in the circadian mechanism, in cardiovascular structure and function. Mice lacking Bmal1 (Bmal1−/− knockout mice) exhibit a loss of the normal 24-hour cyclic variation in heart rate and blood pressure compared to wild-type controls.98 Bmal1-deficient mice also tend to exhibit behavioral arrhythmia, a shortened lifespan, and develop age-associated dilated cardiomyopathy. This cardiomyopathy is characterized by myofilament disorganization, including disruption of the sarcomere architecture, a shift in titin isoforms, and a decrease in systolic ventricular performance prior to the onset of overt dilated cardiomyopathy.99 In a cardiomyocyte-specific mouse knockout model (CBK), deleting bmal1 triggers diastolic dysfunction, an extracellular matrix response, and abnormal inflammatory responses in the heart.100 Notably, these CBK mice develop dilated cardiomyopathy and have a reduced life span, highlighting the critical role of BMAL1 in influencing essential functions in the heart.57 A human embryonic stem cell model with BMAL1 knockout and derived human BMAL1-deficient cardiomyocytes revealed a critical role for BMAL1 in optimizing mitochondrial and cardiac function.101 Furthermore, a murine model with heart-specific deletion of Bmal1 not only exhibited decreased heart function but also manifested systemic insulin resistance, hyperglycemia with aging, and reduced insulin-induced phosphorylation of Akt in the liver implying that loss of Bmal1 in the heart is associated with hepatic insulin resistance.102 Collectively, these studies emphasize the regulatory role of BMAL1 in the heart, and especially in critical areas of structural and functional importance.

v). REV-ERB in the accessory loop:

The orphan nuclear receptors REV-ERBa and REV-ERBb function as transcriptional repressors, binding to retinoic acid-related orphan receptor response elements (ROREs).103–105 This binding contributes to the regulation of the circadian mechanisms’ 24-hour cycling,106, 107 and regulates various molecular output molecules,108 in a time-of-day manner.103, 109 REV-ERB knockout mice, when studied in MI and reperfusion, show susceptibility to HF development, similar to their wild-type littermates.110 Consequently, they have not been extensively used to study the circadian mechanism’s effects on heart disease. However, due to the constitutive repressor activity of REV-ERB, it appears to be an ideal target within the circadian mechanism in the heart for therapeutic purposes post-MI. That is, targeting REV-ERB with small molecule modulators has shown promise in improving outcomes in murine MI and HF models. Section C of this review delves into further details on this potential strategy to enhance cardiovascular therapy by targeting REV-ERB.

vi). PER2 and its role in the heart:

PERIOD is found in the negative arm of the circadian mechanism. The discovery of the Period gene dates to 1971 when it was first identified in Drosophila through using mutagenesis experiments.111 Following this, the mammalian counterpart, Per1, was identified by two separate research groups.112, 113 This gene codes for a protein containing a PAS dimerization domain and exhibits robust circadian rhythmicity.112 Subsequently, two more mammalian Period gene were identified (Per2,114 Per3115). PERIOD production is driven by CLOCK and BMAL1 from the positive arm of the circadian mechanism, then it combines with CRYPTOCHOME in the negative arm to represses its expression and propel the circadian mechanism forward.97, 116

Various genetic rodent studies have been done to investigate the role of PERIOD, and especially PER2. It plays a role in regulating cardiac glucose and lipid metabolism, especially during MI and reperfusion injury.13, 117, 118 However, Per2−/− mice exposed to hind limb ischemia demonstrated impaired blood flow recovery and developed auto-amputation of the distal limb. This was linked to impaired endothelial progenitor cell function in Per2−/− mice.119 Further, mice with endothelial-specific Per2 knockout display increased vascular permeability and larger infarct sizes following MI and reperfusion injury.13 Further, conditional deletion of Bmal1 in the endothelium resulted in increased microvascular and macrovascular injury upon an ischemic insult.120 Interestingly, endothelial cells of Bmal1−/− or Per2−/− mice demonstrate significantly decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation and, consequently, reduced nitric oxide production and increased superoxide levels.37, 121 Further, studies have shown that PER2 overexpression improves cardiac remodeling post-MI,122 and that PER2 is essential to maintain early endothelial progenitor cell function and angiogenesis after MI in mice.123 In contrast to the above-mentioned research, two studies from the same research group found protective effects from MI in the mPer2 mutant mouse model.124, 125

vii). From rodents to humans:

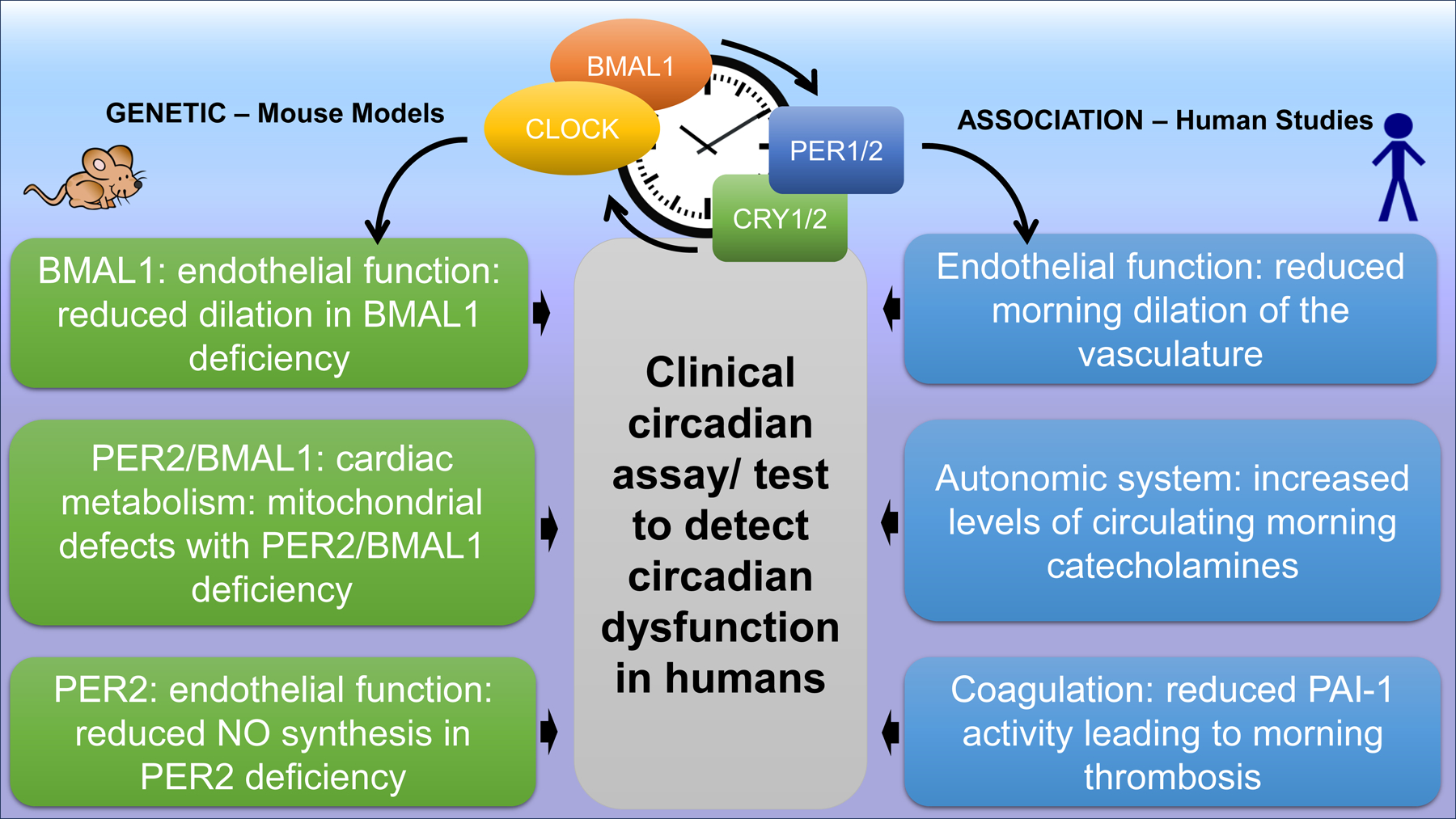

Notably, animal studies have provided significant insight into the molecular workings of the circadian mechanism of the heart and cardiovascular disease. (Figure 2). However, severalcaveats exist which need to be considered when translating circadian biology to human medicine, such as in the promising therapeutic strategies detailed below. First, rodents are nocturnal, and humans are diurnal, and thus the relative effects of light and time of day need thorough investigation. Second, although human epidemiological studies align with these animal findings, identifying a direct genetic equivalent to cardiovascular disease in humans remains elusive. Third, while a putative deficiency in circadian genes is referred to as ‘circadian disruption’ in humans, there are currently no definitive genetic or biological tests available to diagnose circadian rhythm disruption in the human cardiovascular system. Finally, it is worth noting that cardiovascular diseases such as MI remain common, morbid, and often fatal.126 New cardioprotective therapies aimed at limiting infarct size, save for reperfusion therapy, remain unrealized.127 Application of the resources of the NIH Consortium for PreclinicAL AssESsment of CARdioprotective Therapies (CAESAR)128 may help promising circadian therapies aimed at reducing infarct size reach their translation potential.

Figure 2. Impact of circadian rhythms on cardiovascular functions.

Data from genetically modified mice explain mechanistically how circadian rhythms are involved in the pathogenesis of MI or HF and explain the time-of-day dependency of ischemic events (left). Data from humans have similar phenotypic findings but there are no genetic studies that can prove causality between circadian rhythms proteins and the observed cardiovascular phenotype in humans (right). In addition, there is no clinical tool available yet to monitor and detect circadian dysfunction in humans; mouse icon = mouse studies, manikin icon = human studies) Illustration credit: Sceyence Studios

B. The Circadian-Hypoxia Link & Light as a Therapy

The evolutionary connection between circadian rhythms and hypoxia.

Sunlight and oxygen are dominating features shaping life on Earth. All organisms are equipped with molecular mechanisms to sense these critical factors. This evolutionary adaptation traces back to cyanobacteria, among the first organisms to appear on Earth.129 Cyanobacteria, being photosynthetic, adapted to the rhythmic cycles of light and darkness, and perhaps in doing so, fostered the development of an internal clock. This could have provided an evolutionary advantage over time.130, 131

Cyanobacteria’s photosynthesis increased atmospheric oxygen, triggering the ‘Great Oxygenation Event’ about 850 million years ago.129 This change spurred the development of molecular mechanisms in organisms to sense both light and oxygen.129–132 While oxygen therapy is widespread in clinical use today, light’s therapeutic potential remains underestimated. The event eliminated anaerobic bacteria, enabling organisms to sense environmental oxygen through hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs).133–136 Cellular adaptation to varying oxygen levels is crucial for survival amidst changing environmental conditions.96, 134, 136–140 In mammals, the molecular connection between light and oxygen-sensing pathways is evident, with proteins like HIF1A belonging to the same family as core circadian proteins such as PER96, 134, 141–143 This protein family acts as sensors for oxygen, light, or metabolism,96 134, 142–144 influencing diverse cellular functions.142 The 250–300 amino acid PAS domains, named after homologous regions in Drosophila genes (PER, ARNT, SIM), play key roles in signal transduction pathways142 and as transcription factors.143 Some PAS domains facilitate protein-protein interactions, enabling the formation of heterodimers and homodimers.96, 143, 144 This interaction allows PER to interact with other PAS domain-containing proteins at a molecular level.140, 143 Similarly, both PER2 and HIF1A possess PAS domains, suggesting similar functions in adapting to changes in oxygen or light conditions. While light can activate PER2, a similar mechanism might apply to HIF1A as well.61

The PER2-HIF1A connection in protecting the heart from ischemia is based on adenosine-dependent hypoxia adaptation research.

Adenosine, vital for cellular hypoxia adaptation,145–148 signals through four distinct ADORA receptors in the extracellular compartment,145, 149, 150 particularly during hypoxic conditions,151 significantly enhancing adenosine production and signaling.152–154 The adenosine signaling protects against hypoxia by inhibiting vascular leakage,155 or hypoxia-driven inflammation,156, 157 well established in cardiac protection from ischemia-reperfusion injury.158–162 Studies inhibiting adenosine production or signaling abolished the cardioprotective responses induced by cardiac ischemic preconditioning.151, 163, 164 Cardiac ischemic preconditioning, discovered in the early 1980s, significantly reduces infarct size,165 with the ADORA2B receptor playing a critical role.152

In ADORA2B-dependent heart protection, studies using microarray analysis of Adora2b−/− mouse hearts revealed PER2’s crucial role in adenosine-induced protection against MI reperfusion injury.117 Specifically, PER2 initiated a HIF1A-dependent transcriptionally induced metabolic shift in the ischemic heart, favoring oxygen-efficient glycolysis.117 Ischemic preconditioning increased cardiac PER2 in wild-type mouse hearts but not in Adora2b-deficient hearts.117 Patients with MI-induced HF had elevated per2 mRNA levels in heart tissue.117 ADORA2B signaling in human endothelial cells increased per2 mRNA via phospho-CREB binding to the PER2 E-box promoter region, preventing PER2 protein degradation through cullin-1 deneddylation.117

Research on the PER2 and HIF1A connection revealed PER2’s role as an upstream regulator of HIF1A-dependent transcription. Both Per2−/− and Adora2b−/− mice exhibit reduced levels of hif1a mRNA and its dependent genes.117 Circadian oscillation in cardiac HIF1A protein levels linked to PER2,117 alongside the circadian mechanism’s necessity for HIF1A’s oxygen-sensing ability, was indicated.166 The circadian mechanism regulates HIF1A nuclear protein level localization and oscillation.144 ChIP-seq studies revealed that BMAL1-CLOCK binds to the HIF1A promoter,167 directly linking the circadian mechanism to HIF1A regulation. These studies also reveal diurnal rhythms in oxygen levels in rodents tissues, peaking during the dark phase, impacting the circadian clock via a HIF1A-dependent process.168 142 Collectively, these findings suggest PER2’s role as an HIF1A effector within the circadian mechanism, proposing a bi-directional interaction in light and oxygen sensing pathways.

Other Circadian Mechanisms Regulating Cardiac Ischemic Tolerance.

Besides the adenosine-HIF1A-PER2 axis, evidence suggests circadian rhythms operate through various mechanisms to enhance ischemic tolerance. They regulate apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy in cardiovascular disease.3, 87 Other mechanisms promoting ischemia tolerance include circadian control of oxidative stress, SIRT1, heart-brain connection, mitochondrial metabolism, and inflammation.4, 40, 86, 169, 170 A study in humans showed that perioperative myocardial injury is transcriptionally orchestrated by the circadian mechanism in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement, and REV-ERB modulation appears as a potential pharmacological strategy for cardioprotection.171

Light Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease.

Light’s potential as a therapy, as demonstrated by animal models, is attributed to its indirect impact on peripheral tissues like the heart. This influence is driven by outputs from the SCN’s circadian mechanisms rather than direct light perception.172 62 173 Intriguingly, the intensity of light plays a role in cardio protection. Intense light stabilizes cardiac PER2, mimicking ischemic preconditioning,117 and increases adenosine levels,13 contributing to cardioprotection, a response lost in Adora2b−/− mice. Moreover, intense light increases PER2’s circadian amplitude, indicating a protective role for a robust circadian system.13

This potential for light therapy extends to treating MI reperfusion injuries. In murine models, intense light reduces infarct size post-reperfusion within 24 hours, a protective effect absent in Per2−/− mice.13 Furthermore, PER2 amplitude enhancement was abolished in blind mice.13, 174 Intense light also upregulates Angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4), regulated by HIF1A in cardiac endothelial cells,175 protecting against endothelial barrier dysfunction during myocardial injury.176 This impact is supported by Evans blue dye confirmation, revealing improved endothelial barrier function during injury, except in mice lacking endothelial Per2. Subsequent investigations show how intense light, dependent on PER2, stimulates ANGPTL4 and enhances HIF1A binding to its promoter region,177 elevating cardiac Claudin-1 and Cox4.2 mRNA levels.13 These findings emphasize the critical role of intense light-induced PER2 in regulating HIF1A-ANGPTL4 pathways, preserving vascular integrity during myocardial injury, and providing cardio protection.

In vitro studies using a lentiviral-mediated PER2 knockdown human microvascular endothelial cells178 reveal reduced HIF1A-transcription of Claudin-1, increasing cell permeability during hypoxia.13 Proteomic analysis under hypoxic conditions indicates PER2’s metabolic role in controlling mitochondrial function via mitochondrial complex 4.13 Endothelial PER2 influences mitochondrial oxygen consumption and ATP production during hypoxia.179–181 Additionally, hypoxia-induced changes in Cox4.2 mRNA, known for enhancing oxygen efficiency, were disrupted in PER2 knockdown endothelial cells, affecting ZTP levels.182 In Per2−/− mice, ischemia-induced increases in complex 4 activity were reduced.

Translation – Light Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease in Humans.

Intense light exposure [10,000 LUX], known for treating seasonal mood disorders,183 has been explored in healthy individuals.13 Intriguingly, experiments show that PER2 levels are increased with intense light, in buccal and plasma samples, with higher impact observed in the evening versus the morning. This suggests that intense light not only involves PER2 but may heighten its circadian fluctuations. Remarkably, when 20 volunteers were exposed to morning intense light over five days, their sleep patterns improved.13 Additionally, light exposure increased daytime activity levels, coinciding with the enhancement in circadian rhythm amplitude. These findings suggest that intense light therapy holds promise for bolstering circadian rhythms in humans, potentially alleviating the effects of MI and reperfusion injury in patients.

The rising burden of critical illness around the world, and the demand for more ICU beds underscore the urgency for research aiming to improve outcomes for critically ill patients184 With mortality rates around 16% in the critically ill,185 addressing disruptions in circadian rhythms - crucial to physiological homeostasis – is imperative. The ICU environment and postoperative care often disturb these rhythms due to the absence of natural cues like light, regular meals, and physical activity.1, 61, 186 Importantly, experimental studies demonstrate how disrupting rhythms during the first few days post-MI, simulating ICU conditions, can have profound adverse effects on infarct expansion and outcomes.1, 68 Providing care aligned with the patient’s natural circadian rhythms is crucial for optimal recovery. Guidelines on incorporating circadian medicine into clinical practice have been developed to improve patients’ circadian rhythms and sleep, implement patient-level changes in the ICU, and promote hospital-level changes, education and awareness to collectively enhance long-term outcomes.1

Light manipulation strategies may also work in other ways to improve healing in various health conditions. Endothelial cells and the vasculature play underlie the pathogenesis of a numerous human conditions. Vascular endothelial dysfunction is a feature of vascular diseases and involvement in stroke, cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, insulin resistance, chronic kidney failure, tumor growth, metastasis, venous thrombosis, and virus infections..187 Indeed, for patients over 45, perioperative mortality rates stand at ~1–2%, with nearly half of these deaths arising from cardiovascular issues.188 Myocardial injury during noncardiac surgeries affects approximately 20% of patients over the age of 45188 and significantly increases 1-year mortality rates. Endothelial dysfunction may be a significant contributor to this injury. Reversing endothelial dysfunction and reducing perioperative myocardial injury could profoundly better the future of healthcare, as in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The circadian-hypoxia link in cardio protection.

MI or intense light can increase cardiac adenosine levels, which then signals via the adenosine A2B receptor (ADORA2B). Cardiac ADORA2B signaling then increases PER2 protein and transcript levels via phospho-CREB or CULLIN1. Increased cardiac PER2 signaling also increases HIF1A signaling, resulting in an oxygen efficient metabolism, which is cardioprotective. Using intense light during the day increases the circadian amplitude, boosts the endothelial function, and thereby will reduce the occurrence of cardiovascular events in critically ill patients or high-risk patients undergoing surgery. Using intense light in the perioperative setting has therefore the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality. Illustration credit: Sceyence Studios

C. Unlocking Cardiovascular Therapy Potential: Targeting NLRP3 Inflammasome via Circadian Modulation

A groundbreaking therapeutic approach for mitigating MI injury and HF involves the use of novel synthetic ligands that target the circadian mechanism. These small molecule modulators show significant promise in addressing cardiovascular diseases, particularly in the context of MI and reperfusion-induced HF.110 The rationale stems from observations that although timely reperfusion therapy post-MI is a standard treatment for restoration of blood flow to infarcted heart,189, 190 it comes with a significant drawback - reperfusion injury, which worsens long-term outcomes by exacerbating infarct expansion.68, 190–194 (Figure 4A) Previous attempts to directly target the induced inflammatory response proved challenging due to the broad impact of anti-inflammatory drugs on essential immune responses for cardiac repair.195 Also, previous attempts to focus on specific immune pathways also yielded no clinical breakthrough.196–198 Recent studies identify the NLRP3 inflammasome as a critical factor in reperfusion injury,86, 110, 199–202 but direct targeting efforts in clinical trials have encountered obstacles.

Figure 4. Circadian Molecules to Medicine.

A) Reperfusion in timely-treated MI patients rescues myocardium but paradoxically leads to damage and cell death, contributing significantly to the final infarct size and long-term outcomes. Reducing reperfusion injury can improve outcomes post-MI. B) The NLRP3 inflammasome is a large intracellular signaling molecule activated with post-MI reperfusion, and it contributes to reperfusion injury by amplifying inflammation and worsening heart tissue damage, making it a prime target for strategies aimed at mitigating reperfusion injury. The circadian mechanism regulates transcription of the NLRP3 protein component of the inflammasome. Use of REV-ERB inhibitors, like the REV-ERB agonist SR9009, can block REV-ERB mediated transcription of NLRP3, thus preventing inflammasome formation and reperfusion injury after MI. Illustration credit: Sceyence Studios

Directly targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome encountered challenges such as unknown natural ligands, ambiguous drug binding sites, and difficulties optimizing drugs due to a lack of a clear biomolecular structure.203 Downstream targeting of the inflammasome, for example by treating IL-1b with canakinumab or anakinra, resulted in unintended immunosuppressive consequences.204 Various compounds aimed at the inflammasome lacked specificity in vitro (e.g. b-hydroxybutyrate,205 Bay 11–7082,206 DMSO,207 or interferon 1,208), or showed promise in animal models (CY-09209, OLT1177210 targeting NLRP3 ATPase; Tranilast211 targeting NLRP3 oligomerization; Oridonin212 targeting NLRP3 cysteine 279) but concerns about high doses and hepatotoxicity hindered clinical progress.213 While MCC950 had some of the best success in vivo, it was not successful in human trials due to high required doses and liver enzyme concerns.214–217

A novel approach emerges by focusing on circadian biology to target the NLRP inflammasome. Instead of directly targeting the inflammasome or its downstream pathways, it is possible to influence NLRP3 transcription by targeting the circadian factor REV-ERB. This strategy prevents the formation of the NLRP3 protein and, subsequently, the NLRP3 inflammasome in post-MI reperfused hearts.110

Mechanistically, following MI, REV-ERB stimulates NLRP3 transcription, translation, and inflammasome production, as demonstrated in vitro and in vivo.110 Pharmacological modulation of REV-ERB, for example with the agonist SR9009,218, 219 reduces cardiac pathology,220 prevents HF,110, 221 and improves outcomes in various cardiovascular studies.171, 222 In the MI and reperfusion specifically, administering SR9009 at the time of reperfusion in murine studies significantly reduces post-ischemic infarct size and improves cardiac repair.110 SR9009 temporarily impedes NLRP3 production, acting like a “Stop sign” holding REV-ERB to its state of repressing NLRP3 production. (Figure 4B) Studies using cardiac cells in vitro, and REV-ERB knockout mice (Nr1d1−/−) in vivo, reinforce SR9009’s specificity and its REV-ERB-dependent post-MI cardiac benefits.110 Timing of SR9009 administration exhibits flexibility, suggesting that a single dose alongside contemporary reperfusion could be a feasible clinical strategy to enhance cardiac repair and improve long-term outcomes. Ongoing research on circadian modulation using SR9009 and other small molecules holds substantial promise for novel drugs to reduce post-MI reperfusion injury, progression to HF, and benefit cardiovascular disease treatment.

D. Chronotherapy Treatments and Clinical Cardiology

Chronotherapy, a strategic approach to treatment of cardiovascular (and other) diseases, utilizes the influence of circadian biology on drug dynamics and disease patterns to optimize treatment efficacy and reduce potential side effects.223, 224 Many commonly used medications already come with specific timing recommendations, and thus qualify as chronotherapies, including recommendations for use at bedtime, or morning, aligning with our physiology.225

i). Chronotherapy for hypertension:

One well-known application of chronotherapy in heart disease is its use in addressing non-dipping nocturnal hypertension. Normally, blood pressure follows a day-night pattern, with a morning rise and a nighttime dip of about 10%. However, individuals with non-dipping patterns, particularly those with hypertension, have a greater risk of adverse cardiovascular events, including MI, and higher mortality rates.226–228 To tackle this, chronotherapies like Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEi) and other cardiovascular medications have been suggested for evening use to help induce a more typical dipping pattern, mange nighttime hypertension, and reduce associated cardiovascular risks.229, 230

Moreover, various factors such as shift work, sleep duration, meal timings, and disruptions in gut microbiome circadian rhythms, can contribute to conditions that increase the likelihood of hypertension. This elevated blood pressure, in turn raises health risks, including MI leading to HF. Recognizing the clinical significance of these factors, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) organized a workshop focusing on these aspects.231 Their aim was to explore how investigating chronotherapy for hypertension could help fill knowledge gaps and pave the way for new research directions, ultimately aiming to enhance patient outcomes.

ii). Aspirin and platelet reactivity:

Another intriguing chronotherapy application relevant to ischemic heart disease involves aspirin treatment. Recent studies suggest that patients advised to take low-dose aspirin might benefit from taking it in the evening instead of the morning.232 The rationale being that aspirin decreases platelet reactivity, which exhibits a circadian pattern.233 That is, by taking it in the evening, it can reduce platelet reactivity overnight, reducing the likelihood or severity of myocardial infarction the next morning – a time when risk of adverse cardiovascular events is at its highest.17, 79 Taking aspirin in the morning might be less effective because by then, platelets are already highly reactive. Notably, a recent clinical trial tested bedtime aspirin dosing in patients with coronary artery disease and arterial hypertension, demonstrating a significant reduction in platelet aggregation.234

iii). Targeting cardiac pathophysiology:

One fascinating but often overlooked aspect of chronotherapy in treating of cardiovascular disease is its direct impact on benefiting the heart itself, beyond just affecting blood pressure rhythms or blood clotting. In the TAC murine model of pressure-induced HF, administering the short-acting ACEi, captopril, during the animals’ sleep time, resulted in less adverse remodeling of the heart and better cardiac function compared to giving a placebo or administering this ACEi during their waking hours.235, 236 A critical factor contributing to this chronotherapeutic success was aligning the timing of ACEi with the peak activity of its intended target, rather than dosing when its effectiveness was at a low point. These findings align with trials like the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study237, 238 and the Comparison of Amlodipine vs Enalapril to Limit Occurrences of Thrombosis (CAMELOT) trial,239 where timing drug intake potentially improved cardiovascular outcomes, even when there were minimal changes in blood pressure. Recent reports also indicate that other commonly used medications, which have short half-lives and interact with circadian rhythm-related gene products, might hold potential for future chronotherapeutic applications.240 This highlights a crucial aspect: part of chronotherapy’s significant potential largely stems from its direct benefits on the pathophysiology of targeted organs.

iv). Mealtimes and Food Chronotherapy:

Aligning meal schedules with the body’s natural circadian rhythm can be a therapeutic approach, following the principles of chronopharmacology. This concept, termed food chronotherapy, holds potential to positively impact MI recovery and HF outcomes. For example, studies in mice demonstrate that changing daily food intake patterns can lead to persistent disruptions in the heart’s internal circadian mechanism.241 Mice fed only during their less active period (their subjective sleep time) develop internal circadian misalignment. While the hypothalamic SCN remains synced with the 24-hour light-dark cycle, the circadian mechanism in the liver adjusts in line with the feeding cycles opposite to the usual time of day. However, the heart clock undergoes a minor shift of only a few hours, and gene oscillations are blunted.242

Several recent studies in rodents have demonstrated a time of day of feeding and content effect on myocardial function.95, 243, 244 Additionally, research has demonstrated that the functioning of the gut, the circadian microbiome, and its short chain fatty acid metabolites can also contribute to healthy cardiac growth, renewal, and remodeling and are important for healing post-MI.44 It is tempting to speculate that consideration of food intake strategies may in the future lead to a feasible non-pharmaceutical chronotherapy to benefit patients.

In summary, exploring chronotherapies shows promise in treating cardiovascular diseases including MI and HF, by leveraging time-of-day rhythms in circadian biology, drug dynamics, and pathophysiology, to enhance treatment efficacy while reducing side effects. Notably, chronotherapies like evening medications for nocturnal hypertension, evening aspirin administration to modulate platelet reactivity, and targeted drug delivery for HF, reveal the potential of aligning therapies with the body’s natural biological rhythms. Additionally, food chronotherapy, aligning meal timing with circadian rhythms, offers a non-pharmaceutical avenue to positively impact myocardial recovery and HF outcomes. Research on gut physiology, the circadian microbiome, and their metabolites, offers new avenues for future investigation and enhancing patient outcomes and cardiovascular health.

E. Current Insights into Sex-Specific Phenotypes, Aging, and Mechanisms

Applying circadian biology to clinical cardiology faces a significant challenge due to the noticeable variations in how cardiovascular diseases manifest between men and women. The differences encompass risks, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment efficacy. Moreover, the circadian mechanism directly influences pathophysiology in a sex-dependent manner, impacting conditions like MI and other cardiovascular issues.245 Recognizing and understanding these sex-related differences is critical when integrating circadian medicine clinically. The following overview delves into biological sex in human cardiovascular disease, briefly touches on the role of gender, explores the impact of biological sex and aging using animal heart disease models, and discusses the emerging significance of circadian biology on sex-dependent responses to circadian medicine.

i). Biological Sex in Cardiovascular Disease in Humans.

While traditional perspectives and treatment for cardiovascular disease have primarily focused on older men in Western societies, the global reality is more intricate. Cardiovascular disease affects individuals across socioeconomic statuses and ethnicities, including an increasing impact on women. Although cardiovascular disease rates are lower in younger women compared to age-matched men, a significant surge in conditions such as MI and HF occurs post-menopause, equaling or surpassing rates in men.246 This early life protection observed in women is often attributed to their higher estrogen levels. In later years, while total HF rates tend to align between men and women, sexual dimorphism remains evident in the types of HF. For example, HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is twice as prevalent in women, while HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) dominates in men.247 Variations in HF types are hypothesized to partly result from the tendency for women’s hearts to remodel concentrically.248, 249 Furthermore, the underlying drivers in HF differ, with men largely affected by coronary heart disease and MI, while women are significantly impacted by conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.247

ii). Gender and Cardiovascular Disease.

The term “Gender” refers to self-representation or societal identity, while “Sex” classifies by individuals by reproductive organs or chromosomes.250 Individuals outside typical sex classifications exhibit some unique cardiovascular health findings. For example, cardiovascular disease mortality is increased in individuals with Y-chromosome polysomy.251 Another example is increased risk of ischemic heart disease in individuals with Turner Syndrome, a condition in which one of the X-chromosomes is partially or completely missing.252 Notably, gender may be a modifiable risk factor for coronary heart disease. Individuals with more feminine roles or expressed traits show an increased risk for premature acute coronary syndrome and co-morbidities such as diabetes and hypertension; conversely, a higher male-associated gender score is linked to dyslipidemia.253 Mechanisms linking gender and cardiovascular disease are not well studied and warrant future investigation.

iii). Sex in Experimental Heart Models.

While gender as a social construct does not directly apply in experimental rodent cardiovascular studies, the impact of biological sex can be further explored in these models. For example, a study involving mice lacking the enzyme CTP:phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase (PCYT2), crucial in the cell membrane, revealed that while both male and female mice developed metabolic disorders, only males went on to develop hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy.254 Other rodent heart studies revealed differences in males and females in cardiac myofilament calcium sensitivity,255 in mitochondrial biogenesis, morphology and respiratory function,256 and sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release257. These sex-related variations likely contribute to differing epidemiologic or prognostic outcomes in human heart disease.

iv). Circadian Biology Influences Cardiac Repair post-MI, Exhibiting Different Effects in Males Versus Females.

In male murine MI models, wake-time infarctions result in greater survival rates compared to sleep-time infarctions. This time-of-day dependence for MI-reperfusion tolerance is mediated by the cardiomyocyte clock, as demonstrated in experiments in CCM mice. Indeed, these animals lacked time-of-day variations in MI-reperfusion outcomes.258 This time-of-day dependence on infarct size has also been observed in patients with ST-segment elevation MI, with worse outcomes around wake-time as compared to later in the day.23, 259

Further investigations in male murine MI models reveal that wake-time MI induces early gene responses more closely linked to metabolic pathways and transcription/translation, accompanied by lower inflammatory cytokine levels in the heart and greater neutrophil infiltration, contributing to improved cardiac repair.85 Conversely, sleep-time MI triggers gene expression changes associated with inflammatory responses, higher inflammatory cytokine levels affecting cardiac contractility, and less neutrophil infiltration, collectively contributing to exacerbated cardiac remodeling and poorer outcomes.85

In contrast, female mice exhibit a different pattern compared to males. When infarcted during their wake time, females show reduced survivorship compared to those infarcted during sleep time, opposite to the observed response in males based on the time of day.85 Additionally, neutrophil response is greater at wake-time than at sleep time in female mice post-MI, coinciding with better cardiac outcomes.260 Understanding these temporal variations in cardiac repair post-MI based on biological sex is crucial for advancing circadian biology treatments to enhance outcomes.

v). Aging: Sex-specific and Circadian Mechanism:

Circadian rhythm disruption in +/tau hamsters, regardless of sex, has profound implications for aging. The +/tau hamsters with a circadian period of 22 hours,261 exhibit abnormal nocturnal activity and a reduced life span,262 along with severe cardiac and renal diseases when entrained to a 24-hour light-dark cycle.66 However, maintaining these +/tau hamsters on a 22-hour light-dark cycle restores normal day/night behavioral patterns and prevents the cardiorenal disease phenotype, highlighting the critical role of circadian organization in both sexes.66 This study reveals global asynchrony as an underlying cause of cardiac and renal diseases in aging. Additionally, aging animals with reconsolidated circadian rhythms through hypothalamic SCN tissue grafting experience increased longevity, further underscoring the importance of circadian organization in cardiovascular health and aging.66

Despite these general observations, recent investigations reveal sex-specific differences in the circadian mechanism. In male mice, the circadian factors influence healthy cardiac aging. For example, aging ClockΔ19/Δ19 mice exhibit increasing heart weight, cardiac hypertrophy, ventricular dilation, impaired contractility, and reduced myogenic responsiveness. Dysregulation mRNA and miRNA, especially in the PTEN-AKT pathway appears to be involved in this developing pathology, demonstrating CLOCK’s crucial role in the heart’s renewal with aging.220

In contrast, CLOCK regulates aging differently in female mice.263 Aging female ClockΔ19/Δ19 mice maintain normal cardiac metabolic profiles and life span compared to their aging male counterparts.263 This protection against developing cardiomyopathy in aging females is linked, in part, to differences in cardiolipin composition, as well as AKT signaling pathways in the heart. There is also a hormonal influence, as ovariectomy in ClockΔ19/Δ19 mice eliminates this protection and leads to a phenotype resembling age-dependent cardiovascular disease observed in males,263 highlighting the intricate interplay of circadian mechanisms and sex-specific factors in the biology of aging.

Other studies disrupting core circadian genetic factors further reveal the essential roles in heart and systemic aging, primarily studied in male mice to date, necessitating further investigations in the females. Bmal1 disruption prenatally in males leads to reduced life span and premature aging.264, 265 Male CBK mice show aberrant cardiac metabolism and dilated cardiomyopathy with reduced life span.57 Conditional male Bmal knockouts lacking the BMAL1 protein during adult life also exhibit accelerated aging.266 However, the aging phenotypes of prenatal versus adult-life global knockouts differ,266 indicating that the timing of circadian disruption across the life span plays a role in developing pathology, further highlighting the importance of circadian mechanism factors in aging biology.

Lastly, recent studies highlight the crucial involvement of sex-dependent circadian factors in regulating blood pressure and kidney diseases, known risks for developing cardiovascular disease.267 For example, circadian factor PER1 is identified as an aldosterone target, suggesting the circadian mechanism is involved in regulating sodium homeostasis.268 Studies using site-specific mutations within the kidneys show that male kidney-specific cadherin Cre-positive BMAL1 knockout mice exhibit lower BP, however this response is not observed in the females.269 BMAL1 within the distal segments appears to be involved in the BP responses to a salt-sensitive diet.270 Sex differences are reported in endothelin-1 receptor expression and calcium signaling in the inner medullary collecting duct.271 Further exploration of the importance of circadian biology in the regulation of hypertension in animal models and in humans is recommended in the 2021 NHLBI Workshop Report.231

vi). Challenges for Sex-Specific Circadian Medicine:

This review outlines circadian strategies in clinical cardiology, focusing on MI and HF. Early studies favored male animals, overlooking emerging findings indicating differential responses in females. In the future, circadian studies should be designed to include both male and female rodent models. Similarly, clinical research on circadian strategies for treating ischemic heart diseases should involve both men and women. A recent comprehensive review of chronobiology studies, categorized by biological sex, revealed significant differences in risk factors, disease progression, and treatment responses in women versus men.272 To unlock circadian medicine’s full potential, investigations in both sexes despite complexities and funding is needed for understanding sex-dependent resilience to cardiovascular disease and better patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Circadian rhythms play a crucial role in cardiovascular health, influencing the timing of onset and severity of cardiovascular events and contributing to the healing process from diseases. Understanding this influence reveals the intricate connection between daily physiologic patterns and disease outcomes, paving the way for innovative therapies, especially in cardiovascular conditions like MI reperfusion and HF. Animal studies examining key genes and proteins within the circadian mechanism highlight their importance in cardiac structure, function, and repair, suggesting potential applications in human medicine. Investigating circadian rhythms, oxygen sensing, and light therapy reveals potential interventions for managing myocardial injury. Most data presented in this review are from rodent studies. As such, studies in large animal models or simply humans are clearly required. Regarding intense light therapy, chronotherapy or restricted feeding are low risk strategies which should be tested sooner than later. Small molecule modulators targeting the circadian mechanism, and chronotherapies involving drugs and meal timings, offer promising strategies for managing and treating these cardiovascular conditions, potentially improving patient outcomes. Considering the circadian influences on biological sex and gender, and aging, are crucial when translating studies to the clinic. The emergence of circadian medicine holds considerable promise for promoting longer and healthier lives.

Acknowledgments

T.A.M. was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and is a Career Investigator of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Distinguished Chair in Molecular Cardiovascular Research at the University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada. T.E. was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under Award Number: R56HL156955. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Sole MJ, Martino TA. Circadian medicine: A critical strategy for cardiac care. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martino TA, Delisle BP. Cardiovascular research and the arrival of circadian medicine. Chronobiol Int. 2023;40:1–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabinovich-Nikitin I, Lieberman B, Martino TA, Kirshenbaum LA. Circadian-regulated cell death in cardiovascular diseases. Circulation. 2019;139:965–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mistry P, Duong A, Kirshenbaum L, Martino TA. Cardiac clocks and preclinical translation. Heart Fail Clin. 2017;13:657–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsimakouridze EV, Alibhai FJ, Martino TA. Therapeutic applications of circadian rhythms for the cardiovascular system. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alibhai FJ, Tsimakouridze EV, Reitz CJ, Pyle WG, Martino TA. Consequences of circadian and sleep disturbances for the cardiovascular system. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:860–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sole MJ, Martino TA. Diurnal physiology: Core principles with application to the pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of myocardial hypertrophy and failure. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009;107:1318–1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martino TA, Sole MJ. Molecular time: An often overlooked dimension to cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2009;105:1047–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prin M, Pattee J, Douin DJ, Scott BK, Ginde AA, Eckle T. Time-of-day dependent effects of midazolam administration on myocardial injury in non-cardiac surgery. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:982209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oyama Y, Shuff SR, Burns N, Vohwinkel CU, Eckle T. Intense light-elicited alveolar type 2-specific circadian per2 protects from bacterial lung injury via bpifb1. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 2022;322:L647–L661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oyama Y, Walker LA, Eckle T. Targeting circadian per2 as therapy in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. Chronobiol. Int 2021;38:1262–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyama Y, Shuff S, Maddry JK, Schauer SG, Bebarta VS, Eckle T. Intense light pretreatment improves hemodynamics, barrier function and inflammation in a murine model of hemorrhagic shock lung. Mil. Med 2020;185:e1542–e1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oyama Y, Bartman CM, Bonney S, Lee JS, Walker LA, Han J, Borchers CH, Buttrick PM, Aherne CM, Clendenen N, Colgan SP, Eckle T. Intense light-mediated circadian cardioprotection via transcriptional reprogramming of the endothelium. Cell Rep. 2019;28:1471–1484 e1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martino TA, Harrington ME. The time for circadian medicine. J Biol Rhythms. 2020;35:419–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sole MJ, Martino TA. Circadian medicine: A critical strategy for cardiac care. Nat. Rev. Cardiol 2023;20:715–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reitz CJ, Rasouli M, Alibhai FJ, Khatua TN, Pyle WG, Martino TA. A brief morning rest period benefits cardiac repair in pressure overload hypertrophy and postmyocardial infarction. JCI Insight. 2022;7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muller JE, Stone PH, Turi ZG, Rutherford JD, Czeisler CA, Parker C, Poole WK, Passamani E, Roberts R, Robertson T, et al. Circadian variation in the frequency of onset of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1315–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braunwald E On circadian variation of myocardial reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 2012;110:6–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen MC, Rohtla KM, Lavery CE, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. Meta-analysis of the morning excess of acute myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:1512–1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tofler GH, Stone PH, Maclure M, Edelman E, Davis VG, Robertson T, Antman EM, Muller JE. Analysis of possible triggers of acute myocardial infarction (the milis study). Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:22–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reitz CJ, Martino TA. Disruption of circadian rhythms and sleep on critical illness and the impact on cardiovascular events. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:3505–3511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martino TA, Young ME. Influence of the cardiomyocyte circadian clock on cardiac physiology and pathophysiology. J Biol Rhythms. 2015;30:183–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reiter R, Swingen C, Moore L, Henry TD, Traverse JH. Circadian dependence of infarct size and left ventricular function after st elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2012;110:105–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suarez-Barrientos A, Lopez-Romero P, Vivas D, Castro-Ferreira F, Nunez-Gil I, Franco E, Ruiz-Mateos B, Garcia-Rubira JC, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Macaya C, Ibanez B. Circadian variations of infarct size in acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ibanez B, Suarez-Barrientos A, Lopez-Romero P. Circadian variations of infarct size in stem1. Circ Res. 2012;110:e22; author reply e23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El Jamal N, Lordan R, Teegarden SL, Grosser T, FitzGerald G. The circadian biology of heart failure. Circ. Res 2023;132:223–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song S, Tien CL, Cui H, Basil P, Zhu N, Gong Y, Li W, Li H, Fan Q, Min Choi J, Luo W, Xue Y, Cao R, Zhou W, Ortiz AR, Stork B, Mundra V, Putluri N, York B, Chu M, Chang J, Yun Jung S, Xie L, Song J, Zhang L, Sun Z. Myocardial rev-erb-mediated diurnal metabolic rhythm and obesity paradox. Circulation. 2022;145:448–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber MA, Drayer JI, Nakamura DK, Wyle FA. The circadian blood pressure pattern in ambulatory normal subjects. The American journal of cardiology. 1984;54:115–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degaute JP, van de Borne P, Linkowski P, Van Cauter E. Quantitative analysis of the 24-hour blood pressure and heart rate patterns in young men. Hypertension. 1991;18:199–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dillier R, Zuber M, Arand P, Erne S, Erne P. Assessment of systolic and diastolic function in heart failure using ambulatory monitoring with acoustic cardiography. Ann Med. 2011;43:403–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arsenos P, Gatzoulis KA, Gialernios T, Dilaveris P, Tsiachris D, Archontakis S, Vouliotis AI, Raftopoulos L, Manis G, Stefanadis C. Elevated nighttime heart rate due to insufficient circadian adaptation detects heart failure patients prone for malignant ventricular arrhythmias. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172:e154–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh RB, Cornelissen G, Weydahl A, Schwartzkopff O, Katinas G, Otsuka K, Watanabe Y, Yano S, Mori H, Ichimaru Y, Mitsutake G, Pella D, Fanghong L, Zhao Z, Rao RS, Gvozdjakova A, Halberg F. Circadian heart rate and blood pressure variability considered for research and patient care. Int J Cardiol. 2003;87:9–28; discussion 29–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, Sun R, Jiang T, Yang G, Chen L. Circadian blood pressure rhythm in cardiovascular and renal health and disease. Biomolecules. 2021;11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costello HM, Gumz ML. Circadian rhythm, clock genes, and hypertension: Recent advances in hypertension. Hypertension. 2021;78:1185–1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turton MB, Deegan T. Circadian variations of plasma catecholamine, cortisol and immunoreactive insulin concentrations in supine subjects. Clin Chim Acta. 1974;55:389–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paschos GK, FitzGerald GA. Circadian clocks and vascular function. Circ Res. 2010;106:833–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anea CB, Zhang M, Stepp DW, Simkins GB, Reed G, Fulton DJ, Rudic RD. Vascular disease in mice with a dysfunctional circadian clock. Circulation. 2009;119:1510–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rudic RD, McNamara P, Reilly D, Grosser T, Curtis AM, Price TS, Panda S, Hogenesch JB, FitzGerald GA. Bioinformatic analysis of circadian gene oscillation in mouse aorta. Circulation. 2005;112:2716–2724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kroetsch JT, Lidington D, Alibhai FJ, Reitz CJ, Zhang H, Dinh DD, Hanchard J, Khatua TN, Heximer SP, Martino TA, Bolz SS. Disrupting circadian control of peripheral myogenic reactivity mitigates cardiac injury following myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duong ATH, Reitz CJ, Louth EL, Creighton SD, Rasouli M, Zwaiman A, Kroetsch JT, Bolz SS, Winters BD, Bailey CDC, Martino TA. The clock mechanism influences neurobiology and adaptations to heart failure in clock(19/19) mice with implications for circadian medicine. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin C, Xu L, Tang X, Li X, Lu C, Cheng Q, Jiang J, Shen Y, Yan D, Qian R, Fu W, Guo D. Clock gene bmal1 disruption in vascular smooth muscle cells worsens carotid atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42:565–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chalmers JA, Martino TA, Tata N, Ralph MR, Sole MJ, Belsham DD. Vascular circadian rhythms in a mouse vascular smooth muscle cell line (movas-1). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1529–1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnston JG, Pollock DM. Circadian regulation of renal function. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;119:93–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mistry P, Reitz CJ, Khatua TN, Rasouli M, Oliphant K, Young ME, Allen-Vercoe E, Martino TA. Circadian influence on the microbiome improves heart failure outcomes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2020;149:54–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paschos GK, FitzGerald GA. Circadian clocks and metabolism: Implications for microbiome and aging. Trends Genet. 2017;33:760–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kapiotis S, Jilma B, Quehenberger P, Ruzicka K, Handler S, Speiser W. Morning hypercoagulability and hypofibrinolysis. Circulation. 1997;96:19–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahmoud KD, Lennon RJ, Ting HH, Rihal CS, Holmes DR. Circadian variation in coronary stent thrombosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv 2011;4:183–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Angleton P, Chandler WL, Schmer G. Diurnal variation of tissue-type plasminogen activator and its rapid inhibitor (pai-1). Circulation. 1989;79:101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Otto ME, Svatikova A, Barretto RB, Santos S, Hoffmann M, Khandheria B, Somers V. Early morning attenuation of endothelial function in healthy humans. Circulation. 2004;109:2507–2510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young ME, Razeghi P, Taegtmeyer H. Clock genes in the heart - characterization and attenuation with hypertrophy. Circulation Research. 2001;88:1142–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Durgan DJ, Hotze MA, Tomlin TM, Egbejimi O, Graveleau C, Abel ED, Shaw CA, Bray MS, Hardin PE, Young ME. The intrinsic circadian clock within the cardiomyocyte. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1530–1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Durgan DJ, Trexler NA, Egbejimi O, McElfresh TA, Suk HY, Petterson LE, Shaw CA, Hardin PE, Bray MS, Chandler MP, Chow CW, Young ME. The circadian clock within the cardiomyocyte is essential for responsiveness of the heart to fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24254–24269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stavinoha MA, Rayspellicy JW, Hart-Sailors ML, Mersmann HJ, Bray MS, Young ME. Diurnal variations in the responsiveness of cardiac and skeletal muscle to fatty acids. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E878–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martino T, Arab S, Straume M, Belsham DD, Tata N, Cai F, Liu P, Trivieri M, Ralph M, Sole MJ. Day/night rhythms in gene expression of the normal murine heart. J Mol Med (Berl). 2004;82:256–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Storch KF, Lipan O, Leykin I, Viswanathan N, Davis FC, Wong WH, Weitz CJ. Extensive and divergent circadian gene expression in liver and heart. Nature. 2002;417:78–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bray MS, Shaw CA, Moore MWS, Garcia RAP, Zanquetta MM, Durgan DJ, Jeong WJ, Tsai JY, Bugger H, Zhang D, Rohrwasser A, Rennison JH, Dyck JRB, Litwin SE, Hardin PE, Chow CW, Chandler MP, Abel ED, Young ME. Disruption of the circadian clock within the cardiomyocyte influences myocardial contractile function, metabolism, and gene expression. Am J Physiol-Heart C. 2008;294:H1036–H1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Young ME, Brewer RA, Peliciari-Garcia RA, Collins HE, He L, Birky TL, Peden BW, Thompson EG, Ammons BJ, Bray MS, Chatham JC, Wende AR, Yang Q, Chow CW, Martino TA, Gamble KL. Cardiomyocyte-specific bmal1 plays critical roles in metabolism, signaling, and maintenance of contractile function of the heart. J Biol Rhythms. 2014;29:257–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Podobed P, Pyle WG, Ackloo S, Alibhai FJ, Tsimakouridze EV, Ratcliffe WF, Mackay A, Simpson J, Wright DC, Kirby GM, Young ME, Martino TA. The day/night proteome in the murine heart. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;307:R121–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leibetseder V, Humpeler S, Svoboda M, Schmid D, Thalhammer T, Zuckermann A, Marktl W, Ekmekcioglu C. Clock genes display rhythmic expression in human hearts. Chronobiol Int. 2009;26:621–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jakubcakova V, Oster H, Tamanini F, Cadenas C, Leitges M, van der Horst GT, Eichele G. Light entrainment of the mammalian circadian clock by a prkca-dependent posttranslational mechanism. Neuron. 2007;54:831–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brainard J, Gobel M, Scott B, Koeppen M, Eckle T. Health implications of disrupted circadian rhythms and the potential for daylight as therapy. Anesthesiology. 2015;122:1170–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takahashi JS, Hong HK, Ko CH, McDearmon EL. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: Implications for physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:764–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guler AD, Ecker JL, Lall GS, Haq S, Altimus CM, Liao HW, Barnard AR, Cahill H, Badea TC, Zhao H, Hankins MW, Berson DM, Lucas RJ, Yau KW, Hattar S. Melanopsin cells are the principal conduits for rod-cone input to non-image-forming vision. Nature. 2008;453:102–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pilorz V, Tam SK, Hughes S, Pothecary CA, Jagannath A, Hankins MW, Bannerman DM, Lightman SL, Vyazovskiy VV, Nolan PM, Foster RG, Peirson SN. Melanopsin regulates both sleep-promoting and arousal-promoting responses to light. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lewy AJ, Wehr TA, Goodwin FK, Newsome DA, Markey SP. Light suppresses melatonin secretion in humans. Science. 1980;210:1267–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martino TA, Oudit GY, Herzenberg AM, Tata N, Koletar MM, Kabir GM, Belsham DD, Backx PH, Ralph MR, Sole MJ. Circadian rhythm disorganization produces profound cardiovascular and renal disease in hamsters. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1675–1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martino TA, Tata N, Belsham DD, Chalmers J, Straume M, Lee P, Pribiag H, Khaper N, Liu PP, Dawood F, Backx PH, Ralph MR, Sole MJ. Disturbed diurnal rhythm alters gene expression and exacerbates cardiovascular disease with rescue by resynchronization. Hypertension. 2007;49:1104–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alibhai FJ, Tsimakouridze EV, Chinnappareddy N, Wright DC, Billia F, O’Sullivan ML, Pyle WG, Sole MJ, Martino TA. Short-term disruption of diurnal rhythms after murine myocardial infarction adversely affects long-term myocardial structure and function. Circ Res. 2014;114:1713–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Penev PD, Kolker DE, Zee PC, Turek FW. Chronic circadian desynchronization decreases the survival of animals with cardiomyopathic heart disease. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H2334–2337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scheer FA, Hilton MF, Mantzoros CS, Shea SA. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4453–4458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Furlan R, Barbic F, Piazza S, Tinelli M, Seghizzi P, Malliani A. Modifications of cardiac autonomic profile associated with a shift schedule of work. Circulation. 2000;102:1912–1916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chau NP, Mallion JM, de Gaudemaris R, Ruche E, Siche JP, Pelen O, Mathern G. Twenty-four-hour ambulatory blood pressure in shift workers. Circulation. 1989;80:341–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Knutsson A, Akerstedt T, Jonsson BG, Orth-Gomer K. Increased risk of ischaemic heart disease in shift workers. Lancet. 1986;2:89–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vetter C, Devore EE, Wegrzyn LR, Massa J, Speizer FE, Kawachi I, Rosner B, Stampfer MJ, Schernhammer ES. Association between rotating night shift work and risk of coronary heart disease among women. JAMA. 2016;315:1726–1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]