Abstract

Background:

Neuro-ICU hospitalization for an acute neurological illness is often traumatic and associated with heightened emotional distress and reduced quality of life (QoL) for both survivors and their informal caregivers (i.e., family and friends providing unpaid care). In a pilot study, we previously showed that a dyadic (survivor and caregiver together) resiliency intervention (Recovering Together [RT]) was feasible and associated with sustained improvement in emotional distress when compared with an attention placebo educational control. Here we report on changes in secondary outcomes assessing QoL.

Methods:

Survivors (n = 58) and informal caregivers (n = 58) completed assessments at bedside and were randomly assigned to participate together as a dyad in the RT or control intervention (both 6 weeks, two in-person sessions at bedside and four sessions via live video post discharge). We measured QoL domain scores (physical health, psychological, social relations, and environmental), general QoL, and QoL satisfaction using the World Health Organization Quality of Life Abbreviated Instrument at baseline, post treatment, and 3 months’ follow-up. We conducted mixed model analyses of variance with linear contrasts to estimate (1) within-group changes in QoL from baseline to post treatment and from post treatment to 3 months’ follow-up and (2) between-group differences in changes in QoL from baseline to post treatment and from post treatment to 3 months’ follow-up.

Results:

We found significant within-group improvements from baseline to post treatment among RT survivors for physical health QoL (mean difference 1.73; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.39–3.06; p = 0.012), environmental QoL (mean difference 1.29; 95% CI 0.21–2.36; p = 0.020), general QoL (mean difference 0.55; 95% CI 0.13–0.973; p = 0.011), and QoL satisfaction (mean difference 0.87; 95% CI 0.36–1.37; p = 0.001), and those improvements sustained through the 3-month follow-up. We found no significant between-group improvements for survivors or caregivers from baseline to post treatment or from post treatment to 3 months’ follow-up for any QoL variables (i.e., domains, general QoL, and QoL satisfaction together).

Conclusions:

In this pilot study, we found improved QoL among survivors, but not in caregivers, who received RT and improvements sustained over time. These RT-related improvements were not significantly greater than those observed in the control. Results support a fully powered randomized controlled trial to allow for a definitive evaluation of RT-related effects among dyads of survivors of acute brain injury and their caregivers.

Keywords: Dyads, Caregivers, Quality of life, Neurological illness, Neuro-ICU

Introduction

As biomedical advances have increased survivorship in neurocritical care settings, survivors and informal caregivers (family or friends providing support and care [1]), together called dyads, are often challenged with significant adjustments after hospitalization in a neuro-ICU for an acute neurological injury (ANI) [2-6]. Quality of life (QoL)—a multidimensional construct that includes one’s perception of physical, psychological, social, and environmental health [7]—is an important yet understudied outcome for survivors of ANI, who often report physical, cognitive, and emotional sequelae [8], as well as their informal caregivers, who are managing both survivor and personal responsibilities post ANI [9, 10].

Prior research indicates that general ICU survivors have lower QoL 1 year post hospitalization compared with age-matched and sex-matched reference populations [11]. Both personal (e.g., previous health status) [12] and hospitalization factors (e.g., length of stay) increase risk for poor QoL outcomes in survivors 12 months after discharge [13, 14]. Informal caregivers also report lower health-related QoL post discharge [9] and lower psychological QoL than what is reported in norm-based data during the first year after survivor ICU admission [15]. Limited research of QoL in neuro-ICU dyads from time of admission to past survivor discharge suggests that risk (e.g., posttraumatic stress [PTS] symptoms) [16] and resiliency (e.g., mindfulness, caregiver preparedness) [17] factors are associated with QoL outcomes in neuro-ICU survivors and informal caregivers and point to a need for more research and intervention in this acute population.

QoL is modifiable through skills-based interventions that focus on psychosocial resiliency (e.g., mindfulness, coping, intimate bond) [18], yet prior interventions in general critical care or neurocritical care have had little success in improving QoL post injury. Jensen et al. [19] found that a post-ICU nurse-led recovery program did not outperform standard care in improving ICU survivors’ QoL at 12 months post discharge. Bohart et al. [20] found no improvements in family caregivers’ health-related QoL following the survivor’s participation in the program. In contrast to these studies, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Pucciarelli et al. [21] of dyadic interventions indicates moderate support for dyadic interventions to improve survivors’ physical functioning, memory, and QoL and to decrease depression in caregivers. Overall, interventions tailored for dyads with neurocritical illness early in their course of illness show promise for addressing multiple facets of dyadic recovery from an ANI [22].

To address this clinical research gap, we developed and tested Recovering Together (RT), the first dyadic resiliency program for survivors of ANI and their informal caregivers [22, 23]. In a single-blind pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of RT versus an attention placebo educational control, we found that RT was feasible, credible, acceptable, and delivered with high fidelity by four study therapists. We also found that participation in RT was associated with clinically and statistically significant improvement in depression, anxiety, and PTS over an attention placebo educational control [24].

Here, we report on changes in secondary outcomes of QoL after participation in the RCT to determine whether RT and an attention placebo educational control resulted in within-group or between-group changes in QoL from baseline to post treatment or from post treatment to 3 months’ follow-up. We hypothesized that participation in RT, relative to an attention placebo educational control, would be associated with (1) within-group changes from baseline to post treatment and sustained improvements from post treatment to 3 months’ follow-up in QoL domains, general QoL, and QoL satisfaction for both survivors and caregivers and (2) between-group changes from baseline to post treatment and sustained improvements from post treatment to 3 months’ follow-up in QoL domains, general QoL, and QoL satisfaction for both survivors and caregivers.

Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board and pre-registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier NCT03694678). We have previously published the complete trial methodology [24]. Briefly, we recruited adult dyads in which the survivor was medically and cognitively cleared for participation by the medical team. We obtained written informed consent from 63 dyads of survivors admitted to the neuro-ICU and their informal caregivers (September 2019 to March 2020). First, we accessed the Glasgow Coma Scale [25] (score of greater than 10) from the electronic medical record and used it for initial screening prior to approaching the survivor in the neuro-ICU. Second, a member of our research team administered the Mini-Mental Status Examination [26] (score of greater than 24) to screen survivors and ensure that they were cognitively intact (e.g., oriented, understand and produce language, follow commands, and use executive functioning and memory effectively) and able to meaningfully engage with the program (e.g., use cognitive abilities to participate in the intervention and use skills from week to week). All participants were approached and screened within the first week of hospital admission.

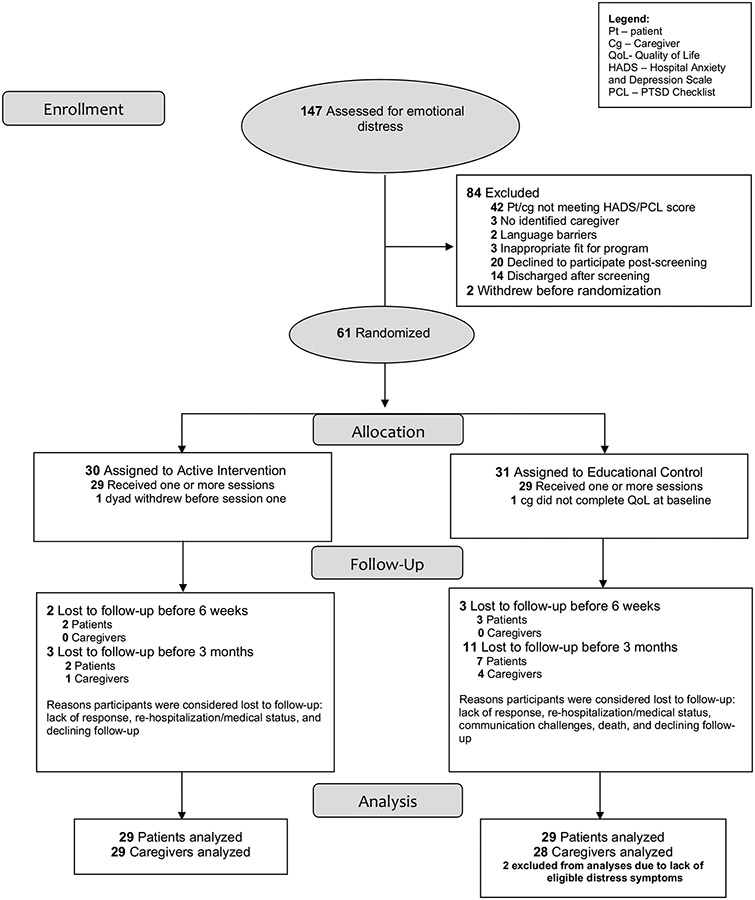

Both members of the dyad (survivor and caregiver) needed to be willing to participate in two in-person and four live video sessions and have access to high-speed internet and video interface (e.g., laptop, tablet, smartphone). At least one member of the dyad needed to endorse clinically significant symptoms of emotional distress (depression, anxiety, or PTS) consistent with our prior research [2, 3, 27, 28]. We used clinical cutoff scores for the emotional distress measures (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [29] and PTSD Checklist [30]). These cutoff scores identify the presence of clinically significant symptoms; however, we did not categorize or treat/not treat participants on the basis of their specific emotional distress scores/severity. Dyads were excluded if the survivor was anticipated to die or never become able to fully participate on the basis of clinical judgement from the medical team. Participant characteristics (Table 1) and study flow (Fig. 1) have also been previously reported [24].

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of randomly assignedized dyads, separately by survivors and caregivers

| Intervention (RT), n = 29 M (SD), Range N (%) |

Control (APC), n = 29 M (SD), Range N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Baseline survivor characteristics | ||

| Age, mean (SD), range (yr) | 49.3 (16.7), 21–83 | 50.1 (16.4), 24–81 |

| Sex, n | ||

| Female | 9 | 12 |

| Female gender (Male) | 9 (20) | 12 (17) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 25 (86.2) | 24 (82.8) |

| Black or African American | 2 (6.9) | 2 (6.9) |

| Asian | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.4) |

| More than > 1 one race | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.4) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married or /civil union | 17 (58.6) | 20 (69.0) |

| Single, never married | 5 (17.2) | 5 (17.2) |

| Divorced or separated | 3 (10.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Living with partner | 1 (3.4) | 2 (6.9) |

| Widowed | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.4) |

| Other | 2 (6.9) | 1 (3.4) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed full-time | 18 (62.1) | 12 (41.4) |

| Retired | 5 (17.2) | 8 (27.6) |

| Student (full-time or /part-time) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.4) |

| Employed part-time | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.4) |

| Unemployed | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) |

| Homemaker | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) |

| Other | 4 (13.8) | 4 (13.8) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Some high school (< 12th grade) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.9) |

| High school diploma (12th grade) | 5 (17.2) | 6 (20.7) |

| Some college or /associates degree | 9 (31.0) | 8 (27.6) |

| 4-year college | 3 (10.3) | 4 (13.8) |

| Graduate/professional | 12 (41.4) | 8 (27.6) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Vascular | 11 (19.0) | 13 (22.4) |

| Neoplasm | 8 (13.8) | 7 (12.1) |

| Spine | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.4) |

| TBI | 2 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Seizure | 2 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Myasthenia gravis | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.4) |

| Other | 5 (8.6) | 5 (8.6) |

| Cognitive status, mean (SD), range | ||

| Mini-mental state examination | 26.8 (2.0), 23–30 | 25.9 (3.1), 13–29 |

| Barthel index | 60.0 (31.7), 0–100 | 65.0 (30.0), 5–100 |

| Modified rankin scale | 3.0 (0.91), 1–5 | 3.0 (1.22), 1–5 |

| Glasgow coma scale, n (%) | ||

| 15 | 25 (86.2) | 25 (86.2) |

| 14 | 3 (10.3) | 4 (13.8) |

| 13 | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Caregiver baseline characteristics | ||

| Age, mean (SD), range (yr) | 52.4 (14.3), 20–75 | 52.1 (14.9), 25–77 |

| Relationship to survivor, n (%) | ||

| Spouse or /partner | 22 (37.9) | 24 (41.4) |

| Parent | 4 (6.9) | 3 (5.2) |

| Sibling | 2 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 22 | 17 |

| Female gender (Male) | 22 (7) | 17 (12) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 25 (86.2) | 20 (69.0) |

| Black or African American | 4 (13.8) | 3 (10.3) |

| Asian | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) |

| More than > 1 one race | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Employed full-time | 14 (48.3) | 18 (62.1) |

| Retired | 6 (20.7) | 4 (13.8) |

| Employed part-time | 3 (10.3) | 2 (6.9) |

| Homemaker | 2 (6.9) | 2 (6.9) |

| Student (full-time or /part -time) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.4) |

| Other | 3 (10.3) | 2 (6.9) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Some high school (< 12th grade) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.4) |

| High school diploma (12th grade) | 4 (13.8) | 5 (17.2) |

| Some college or /Associate degrees | 9 (31.0) | 9 (31.0) |

| 4-year college | 6 (20.7) | 7 (24.1) |

| Graduate/professional | 9 (31.0) | 7 (24.1) |

APC attention placebo control, RT recovering together, TBI traumatic brain injury

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart (CONSORT Diagram)

Treatment Arms

Eligible participants were randomly assigned to the active intervention RT or an attention placebo educational control. Both programs have six sessions (two delivered in the hospital and four delivered via live video after discharge), approximately 30 min per session and, dyads participated together weekly. RT teaches psychosocial resiliency skills for dyads to cope actively and to work toward positive cognitive, behavioral, and interpersonal changes. RT skills include mindfulness, dialectics, acceptance, self-efficacy, coping strategies, and enhancing the dyadic intimate bond. The control condition provides information on ANI-related stress and suggestions for coping without teaching skills.

Study Design

Dyads were allocated randomly (1:1) according to a computer-generated randomization scheduled constructed in permuted blocks [31] of size 2 and 4 by our biostatistician and implemented by REDCap. Dyads were blinded to intervention or control. Details on study flow are present in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram (i.e., CONSORT Diagram; Fig. 1).

Measurement

Data were collected at three time points: baseline, post treatment, and 3 months’ follow-up. The demographic questionnaire and measures were administered via paper and pencil during hospitalization and over a secure data collection platform (REDCap) for post treatment and 3 months’ follow-up. Demographics for this sample are presented in Table 1, and unadjusted means and standard deviations (SDs) for QoL for each time point for survivors and caregivers are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Unadjusted baseline, posttreatment, and 3-month follow-up mean (SD) M (SD) for survivors

| Survivor out- come |

Baseline | Post treatment | 3-month follow- up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical health QoL | |||

| RT | 13.03 (3.59)a | 15.02 (3.77)a | 15.13 (2.90)+ |

| Control | 12.41 (3.77) | 13.51 (3.69) | 13.59 (3.15) |

| Psychological QoL | |||

| RT | 14.64 (2.83) | 15.62 (3.22) | 15.01 (3.44) |

| Control | 14.60 (3.09) | 14.48 (3.76) | 13.07 (3.63) |

| Social relations QoL | |||

| RT | 15.43 (3.10) | 16.00 (2.40) | 16.10 (3.96) |

| Control | 16.07 (2.72) | 15.81 (4.16) | 14.82 (3.07) |

| Environmental QoL | |||

| RT | 16.12 (2.66)b | 17.64 (2.20)b | 17.32 (2.21)+ |

| Control | 16.59 (1.94) | 16.83 (2.18) | 16.50 (2.05) |

QoL quality of life, RT recovering together

The matching superscrtipt should be present for RT physical health baseline to posttreatment

The matching superscript should be for RT Environmental QoL

The superscript indicates sustained improvement from post test to and 3 months’ follow-up

Table 3.

Unadjusted baseline, posttreatment and 3-month follow-up M’ (SD) for caregivers

| Survivor outcome | Baseline | Post treatment | 3-month follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical health QoL | |||

| RT | 16.70 (1.82) | 16.70 (1.81) | 16.70 (3.15) |

| Control | 16.47 (3.37) | 15.65 (3.51) | 16.39 (2.71) |

| Psychological QoL | |||

| RT | 15.54 (2.50) | 15.33 (2.67) | 15.28 (3.35) |

| Control | 15.45 (2.79) | 14.744 (3.97) | 14.60 (3.27) |

| Social relations QoL | |||

| RT | 15.43 (3.06) | 15.84 (3.06) | 15.73 (2.99) |

| Control | 16.50 (2.76) | 15.49 (3.81) | 15.72 (3.25) |

| Environmental QoL | |||

| RT | 16.40 (2.46) | 16.83 (2.47) | 16.72 (2.22) |

| Control | 17.14 (2.11) | 17.04 (2.48) | 17.26 (2.02) |

QoL quality of life, RT recovering together

QoL

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Abbreviated Instrument (WHOQOL-BREF) [32] is a short version of the 100-item WHOQOL [7] and has comparable reliability and validity to the full measure. The first two items of the WHOQOL-BREF assess general QoL and QoL satisfaction on a 5-point Likert scale. Subscales of the WHOQOL-BREF include physical health QoL (seven items, including energy, daily activity, pain, and fatigue), psychological QoL (six items, including positive/negative feelings, spirituality, and self-esteem), social relationship QoL (three items, including personal relationships and social support), and environmental QoL (eight items, including safety, financial resource, time for leisure, living conditions, and access to medical care). Items in each domain are averaged to calculate a total domain score (range 4–20) [32]. The WHOQOL-BREF has good psychometric properties, has been validated in various neurological populations [33, 34], and has been used within critical care settings [17, 35, 36] and for next of kin (similar to our informal caregivers in this sample) [37]. Consistent with prior findings [32], internal consistencies estimated by Cronbach’s α were good for the physical (survivor 0.85; caregiver 0.85), psychological (survivor 0.78; caregiver 0.82), and environmental (survivor 0.76; caregiver 0.81) domains but low for social QoL (survivor 0.42; caregiver 0.64) in this sample.

The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for improvements in WHOQOL-BREF domains was interpreted by using benchmarks from another serious medical illness population (i.e., lung cancer) [38] because an MCID for neurocritical care populations has not been established. MCIDs for QoL domains are 1.55 (physical), 1.26 (psychological), 1.27 (social relations), and 1.14 (environmental) [38]. MCIDs for general QoL and QoL satisfaction do not exist. For each QoL domain, improvements from baseline to post treatment were considered clinically meaningful if mean domain change scores were above their respective MCID.

Statistical Analysis

Consistent with the statistical plan for our primary outcomes [24], these analyses were conducted by using the shared baseline approach, following intent-to-treat principles [24]. Using shared baselines, along with unstructured person-level covariance for repeated measures, allowed us to make linear adjustments for chance differences at baseline and therefore produces valid estimates of our outcomes. We used repeated-measures analyses of variance estimated by maximum likelihood in linear mixed models to estimate both within-group and between-group changes of secondary outcomes. We ran separate models for each QoL domain, as well as for both general QoL and QoL satisfaction items. All analyses were completed separately for survivors and caregivers. Inference was based on two-tailed tests at p < 0.05 without correction for multiple comparisons to broadly explore the association between group and QoL. Consistent with the aims our pilot feasibility trial [24], as well as previous psychosocial intervention trials using the WHOQOL-BREF in other neurologically ill populations [39], our sample provided adequate power (greater than 80%) to detect large effects (greater than 0.75 SD) in this secondary analysis. Importantly, the purpose of our trial was not to provide confirmatory evidence but rather proof of concept.

Results

Prior to analyses, we judged one caregiver to have incomplete data on the WHOQOL-BREF at the baseline assessment (several missing items), and the caregiver was therefore excluded from current QoL analyses. Overall, 58 survivors and 57 informal caregivers (100% sample) completed QoL measurements at baseline, 44 (76%) survivors and 52 (91%) informal caregivers completed QoL measurements at post treatment, and 44 (76%) survivors and 44 (77%) informal caregivers completed QoL measurements at follow-up. Survivor illnesses in this study included vascular (e.g., ischemic/hemorrhagic stroke, aneurysm), neoplasm (e.g., glioblastoma multiform, meningioma), spine (e.g., spinal cord injury, stenosis), traumatic brain injury (e.g., intracranial injury, hematoma), seizure (e.g., status epilepticus), myasthenia gravis, and other (e.g., shunt infection) categories. Patient diagnoses are presented in Table 1. Baseline measurements are presented in Tables 1, 2. There were no baseline differences in demographic or QoL measures between the intervention and control for survivors and caregivers.

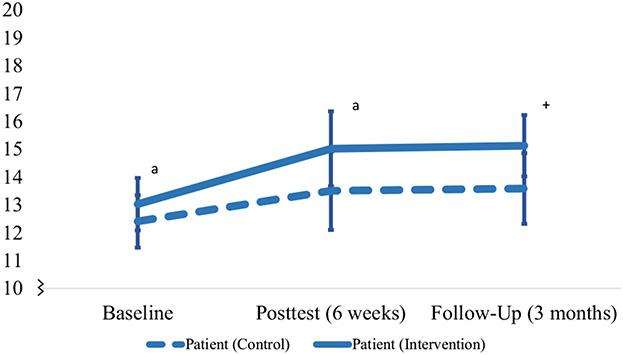

For survivors, participation in RT was associated with statistically significant and clinically meaningful within-group improvements from baseline to post treatment in physical health QoL (mean difference 1.73; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.39–3.06; p = 0.012) (Table 2, Fig. 2) and environmental QoL (mean difference 1.29; 95% CI 0.21–2.36; p = 0.020) (Table 2, Fig. 3). Participation in RT was also associated with significant within-group improvements for RT survivors for both general QoL (mean difference 0.55; 95% CI 0.13–0.973; p = 0.011) and QoL satisfaction (mean difference 0.87; 95% CI 0.36–1.37; p = 0.001). We did not observe statistically significant within-group improvements in psychological or social relations QoL for survivors in RT. There were no statistically significant or clinically meaningful within-group improvements in any QoL outcomes for RT caregivers or in the control condition (survivors or caregivers) from baseline to post treatment.

Fig. 2.

Survivor physical quality of life outcomes (baseline, post test, and 3 months’ follow-up). The superscript “a” indicates a significant within-group improvement between baseline and post test (p < 0.05). The plus sign indicates sustained improvement from post test to 3 months’ follow-up

Fig. 3.

Survivor environmental quality of life outcomes (baseline, post test, and 3 months’ follow-up). The superscript “b” indicates a significant within-group improvement between baseline and post test (p < 0.05). The plus sign indicates sustained improvement from post test to and 3 months’ follow-up

For survivors, participation in RT was associated with sustained within-group improvement from post treatment to 3 months’ follow-up for physical health QoL (mean difference 0.39; 95% CI − 0.98 to 1.75; p = 0.574) (Table 2, Fig. 2), environmental QoL (mean difference − 0.32; 95% CI − 1.53 to 0.89; p = 0.596) (Table 2, Fig. 3), general QoL (mean difference 0.15; 95% CI − 0.30 to 0.60; p = 0.499), and QoL satisfaction (mean difference − 0.20; 95% CI − 0.70 to 0.30; p = 0.427). There were no statistically significant or clinically meaningful within-group improvements from post treatment to 3 months’ follow-up in any QoL outcomes for RT or the control condition (survivors or caregivers).

Participation in RT was not associated with statistically significant or clinically meaningful between-group improvements from baseline to post treatment or post treatment to follow-up in QoL domains, general QoL, or QoL satisfaction (p > 0.05) for survivors or informal caregivers.

Discussion

We analyzed secondary QoL outcomes from a single-blind RCT of a dyadic resiliency program, RT, versus an attention placebo educational control among dyads of neuro-ICU survivors and their informal caregivers. Survivors in RT (but not the control) had statistically and clinically significant within-group improvements in physical health QoL, environmental QoL, general QoL, and QoL satisfaction from baseline to post treatment. RT-related improvements (within group) in survivors’ physical health QoL, environmental QoL, general QoL, and QoL satisfaction sustained at 3 months’ follow-up. No within-group improvements were observed for the control condition at any time point. We did not observe statistically or clinically significant between-group improvements from baseline to post treatment or from post treatment to 3 months’ follow-up for QoL domains (physical health, psychological, social relations, and environmental QoL), general QoL, or QoL satisfaction for survivors or caregivers.

Dyads in RT appeared to have nonsignificant trends toward improvement in QoL domains overtime, with survivors assigned to RT having significant and clinically meaningful within-group improvements in physical health and environmental QoL. The physical health domain assesses activities of daily living, dependence on medical aid, energy, mobility, pain/discomfort, sleep, and capacity for work, whereas the environmental domain assesses financial resources, physical safety, access to and quality of health care, safety and involvement in the living environment, and access to information [7]. Although not the totality of a successful recovery, these two domains appear to align with common measurable anchors of improvement for initial recovery after an ANI (i.e., regaining functioning and mobility, returning home), and physical functioning is, in addition to memory and QoL, noted as a broad area of improvement for survivors participating in dyadic interventions post stroke [21]. Importantly, the WHOQOL-BREF measures participants’ subjective (i.e., perceptions, self-report), as opposed to objective (i.e., factual, observed), outcomes related to QoL. Still, through resiliency-based skills (e.g., mindfulness, coping, intimate bond) and care continuity (e.g., treating dyads from admission to post discharge, monitoring progress weekly), RT may have facilitated a foundation that ultimately leads to greater improvements in survivors for these two domains, which was not seen in the control. Future fully powered research trials may benefit from examining how these QoL domains impact other survivor outcomes post ANI over time.

Given that RT is a psychosocial resiliency-based intervention, the lack of significant improvements for psychological and social relations QoL was initially surprising. However, when we examined these two domains, mean improvements tended to favor RT, whereby a larger, fully powered study might have detected within-group and between-group effects. In the parent RCT [24], we found significant improvements in emotional distress (i.e., anxiety, depression, PTS) and dyadic interpersonal interactions [24], indicating that related constructs to psychological and social relations QoL improve after RT participation. One explanation for this discrepancy is that there may be a difference between specific and general improvements (e.g., psychopathology and interpersonal discord vs. general QoL domains) in dyads post ANI. Our research suggests that levels of emotional distress and coping are interdependent after discharge and that emotional distress outcomes were correlated within dyads in the RCT [40]. Therefore, it may be that these QoL domains also exhibit interdependence in patterns of change across the course of recovery, with caregivers potentially experiencing downstream benefits from improvements in survivor QoL. Future trials will benefit from longer assessment periods to answer these empirical questions.

General QoL and QoL satisfaction improved after RT participation for survivors (within group), and survivors experienced clinically meaningful improvements from RT participation. Previous trials measuring both quantitative and qualitative QoL outcomes in adult ICU survivors have demonstrated that participation in appropriate post-hospitalization interventions was associated with subjective improvements in QoL for those at risk of post-intensive care syndrome [41]. Consistent with the primary aims of our RCT to address emotional distress before chronicity [24], future interventions will likely benefit from emphasizing psychosocial aspects (e.g., managing negative affect, tolerating uncertainty, encouraging flexibility, seeking social support and relationships) early on to enhance dyads’ overall emotional recovery and QoL after an ANI. Last, sustained improvement in physical, environmental, general QoL, and QoL satisfaction provides preliminary evidence for the potential long-term gains from a resiliency-based intervention for survivors’ QoL. As noted, future trials will benefit from longer follow-up assessment time points for survivors to witness gains in QoL occurring in tandem with other outcomes, both individually and dyadically.

Nonsignificant pretreatment to posttreatment changes (between group) in QoL variables in this sample may relate to our neuro-ICU dyads having lower QoL at baseline compared with general populations (≈1 SD lower) [42], with QoL domains of survivors and caregivers being more similar to those of survivors of significant medical illness [38]. Starting with lower QoL at the time of admission may produce a “steep climb” for dyads’ QoL improvement in the first few months of recovery after an ANI. In fact, previous research in this population suggests that baseline emotional distress in the context of an ANI, such as PTS symptoms, predicts lower QoL at 3 months’ follow-up [16]. Considering the primary results of this trial (i.e., RT participation associated with reduced emotional distress) [24], longer follow-up periods after addressing emotional distress may be needed to see improvements in QoL over time. Therefore, future fully powered trials should incorporate longer follow-up periods to fully examine the effects of RT on QoL.

The lack of significant between-group QoL improvements for survivors and caregivers is also consistent with patterns observed in small clinical trials [43] aimed at feasibility and powered to detect large (i.e., greater than 0.75 SD) effects. Despite general trends toward QoL improvement in the RT condition and not in the control, our sample size only allowed for the detection of larger-magnitude improvements. In other words, small to moderate effects, if existent, may not be detected because of the small sample size. Still, fully powered RCTs that have attempted to modify survivor and informal caregiver QoL post ICU discharge have faced challenges in demonstrating QoL improvements for both survivors and caregivers [19, 20, 44]. Different from these studies, however, our general QoL (vs. health-related QoL) baseline assessments occurred at the time of admission (vs. at discharge to 1 month follow-up), with embedded clinicians (vs. nurses) delivering assessments and intervention during the hospitalization. Research exploring QoL in critically ill populations has often assessed QoL before the onset of illness and/or at later postdischarge time points (1 month to 1 year follow-up) [45, 46], with very little research exploring QoL during an ICU admission [16, 17] and after intervention. In our study, we used early QoL assessment at the time of admission in tandem with other psychosocial outcomes to produce useful clinical data whereby baseline QoL could be immediately examined, prioritized, and improved on after an ANI. Although participation in RT was not associated with significant between-group improvements in QoL, our methodological considerations may address QoL in different ways than previous trials among dyads post ICU discharge. Given the great need for examining QoL in critical care populations [47], the current research highlights a unique approach of addressing QoL early on in dyads’ recovery after an ANI.

Strengths of this study included the following: (1) successful recruiting and retention of participants, (2) sampling from a diverse (i.e., heterogenous illnesses/diagnoses) neuro-ICU population, (3) early assessment (i.e., bedside) of QoL, (4) novel delivery of a skills-based resiliency intervention that used both bedside and virtual contact with the survivor and caregiver together, and (5) use of trained and embedded interventionists as part of the greater medical team (e.g., attended rounds, consultation/liaison). Limitations included restricted demographics (majority White, middle aged, well educated) and survivors being generally less sick given inclusion/exclusion criteria (i.e., cognitively intact, not expected to die). This may have restricted the range of QoL scores observed in our sample. Survivors in RT also had greater baseline levels of anxiety and PTS than those in the control condition, which may have influenced how these participants experienced the intervention effects. Last, we used MCIDs from another medically ill population (i.e., cancer) given the lack of ANI-specific MCIDs. Future research should continue attempting to recruit a diverse and robust sample to aid with development of MCIDs for this population.

Conclusions

Overall, these findings provide preliminary evidence that RT has the potential to deliver sustainable benefits for survivors’ physical health and environmental QoL. By providing resiliency-based interventions early on in neurocritical settings, clinicians can improve emotional distress (depression, anxiety, PTS) [24] and promote QoL in survivors over time. Taken together, these two QoL domains may be considered initial markers of progress, whereby survivors, caregivers, and care teams traditionally focused on physical and environmental improvements post ANI (e.g., functioning, transitioning back home, independence, safety) may witness these gains in survivors, along with emotional distress improvement, after RT participation.

During this time of intense adjustment, dyads can intentionally incorporate resiliency-based skills, such as mindfulness, intimate bond, and coping, to further facilitate QoL improvements for survivors early on in recovery. Intervening early can benefit survivors as they move through the recovery process together from admission to post discharge. Providing accessible interventions tailored to this population is an important next step for neuro-ICUs looking to make meaningful change for neuro-ICU dyads, and future resources should be allocated for providing such programs.

Source of support

This study was funded by a grant-in-aid from the American Heart Association, Grant 5R21 NR017979 from the National Institute of Nursing Research to Dr. Vranceanu, and the Henry and Allison McCance Center for Brain Health at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Footnotes

Ethical approval/informed consent

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Vranceanu reported receiving funding from the Department of Defense and the National Institutes of Health and serving on the scientific advisory board for the Calm application, outside of the submitted work. Dr. Macklin reported serving on the scientific advisory boards of Biogen, Cerevance, and Stoparkinson Healthcare Systems, serving on the data safety monitoring boards of Acorda Therapeutics, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and receiving grants from Acorda, Amylyx Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharmaceuticals, Ra Pharmaceuticals, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Clene Nanomedicine, and Prilenia Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. Dr. Rosand reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and OneMind and serving as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and New Beta Innovation, outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.National Alliance for Caregiving; AARP Public Policy Institute. Caregiving in the U.S. 2015. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/caregiving-in-the-united-states-2015-report-revised.pdf. Accessed 5 Sept 2019.

- 2.Meyers E, Lin A, Lester E, Shaffer K, Rosand J, Vranceanu A-M. Baseline resilience and depression symptoms predict trajectory of depression in dyads of patients and their informal caregivers following discharge from the neuro-ICU. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;62:87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyers EE, Shaffer KM, Gates M, Lin A, Rosand J, Vranceanu A-M. Baseline resilience and posttraumatic symptoms in dyads of neurocritical patients and their informal caregivers: a prospective dyadic analysis. Psychosomatics. 2020;61(2):135–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi KW, Shaffer KM, Zale EL, Funes CJ, Koenen KC, Tehan T, et al. Early risk and resiliency factors predict chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in caregivers of patients admitted to a neuroscience ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(5):713–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trevick SA, Lord AS. Post-traumatic stress disorder and complicated grief are common in caregivers of neuro-ICU patients. Neurocrit Care. 2017;26(3):436–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garton ALA, Sisti JA, Gupta VP, Christophe BR, Connolly ES Jr. Poststroke post-traumatic stress disorder: a review. Stroke. 2017;48(2):507–12. Erratum in: Stroke. 2017;48(3):e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(12):1569–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson JC, Mitchell N, Hopkins RO. Cognitive functioning, mental health, and quality of life in ICU survivors: an overview. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2015;38(1):91–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Beusekom I, Bakhshi-Raiez F, de Keizer NF, Dongelmans DA, van der Schaaf M. Reported burden on informal caregivers of ICU survivors: a literature review. Crit Care. 2016;20:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comini L, Rocchi S, Bruletti G, Paneroni M, Bertolotti G, Vitacca M. Impact of clinical and quality of life outcomes of long-stay ICU survivors recovering from rehabilitation on caregivers’ burden. Respir Care. 2016;61(4):405–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soliman IW, de Lange DW, Peelen LM, Cremer OL, Slooter AJ, Pasma W, et al. Single-center large-cohort study into quality of life in Dutch intensive care unit subgroups, 1 year after admission, using EuroQoL EQ-6D-3L. J Crit Care. 2015;30(1):181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Beusekom I, Bakhshi-Raiez F, de Keizer NF, van der Schaaf M, Termor-shuizen F, Dongelmans DA. Dutch ICU survivors have more consultations with general practitioners before and after ICU admission compared to a matched control group from the general population. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(5):e0217225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stricker KH, Cavegn R, Takala J, Rothen HU. Does ICU length of stay influence quality of life? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49(7):975–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iribarren-Diarasarri S, Aizpuru-Barandiaran F, Muñoz-Martínez T, Loma-Osorio A, Hernández-López M, Ruiz-Zorrilla JM, et al. Health-related quality of life as a prognostic factor of survival in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(5):833–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alfheim HB, Småstuen MC, Hofsø K, Tøien K, Rosseland LA, Rustøen T. Quality of life in family caregivers of patients in the intensive care unit: a longitudinal study. Aust Crit Care. 2019;32(6):479–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Presciutti A, Meyers EE, Reichman M, Vranceanu A-M. Associations between baseline total PTSD symptom severity, specific PTSD symptoms, and 3-month quality of life in neurologically intact neurocritical care patients and informal caregivers. Neurocrit Care. 2021;34(1):54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zale EL, Heinhuis TJ, Tehan T, Salgueiro D, Rosand J, Vranceanu A-M. Resiliency is independently associated with greater quality of life among informal caregivers to neuroscience intensive care unit patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;52:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vranceanu A-M, Riklin E, Merker VL, Macklin EA, Park ER, Plotkin SR. Mind–body therapy via videoconferencing in patients with neurofibromatosis: an RCT. Neurology. 2016;87(8):806–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen JF, Egerod I, Bestle MH, Christensen DF, Elklit A, Hansen RL, et al. A recovery program to improve quality of life, sense of coherence and psychological health in ICU survivors: a multicenter randomized controlled trial, the RAPIT study. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(11):1733–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bohart S, Egerod I, Bestle MH, Overgaard D, Christensen DF, Jensen JF. Recovery programme for ICU survivors has no effect on relatives’ quality of life: secondary analysis of the RAPIT-study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;47:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pucciarelli G, Lommi M, Magwood GS, Simeone S, Colaceci S, Vellone E, et al. Effectiveness of dyadic interventions to improve stroke patient–caregiver dyads’ outcomes after discharge: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2021;20(1):14–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bannon S, Lester EG, Gates MV, McCurley J, Lin A, Rosand J, et al. Recovering together: building resiliency in dyads of stroke patients and their caregivers at risk for chronic emotional distress; a feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2020;6:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCurley JL, Funes CJ, Zale EL, Lin A, Jacobo M, Jacobs JM, et al. Preventing chronic emotional distress in stroke survivors and their informal caregivers. Neurocrit Care. 2019;30(3):581–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vranceanu A-M, Bannon S, Mace R, Lester E, Meyers E, Gates M, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of a resiliency intervention for the prevention of chronic emotional distress among survivor-caregiver dyads admitted to the neuroscience intensive care unit: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2020807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;304(7872):81–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state’: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyers EE, McCurley J, Lester E, Jacobo M, Rosand J, Vranceanu A-M. Building resiliency in dyads of patients admitted to the neuroscience intensive care unit and their family caregivers: lessons learned from William and Laura. Cogn Behav Pract. 2020;27(3):321–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaffer KM, Jacobs JM, Coleman JN, Temel JS, Rosand J, Greer JA, et al. Anxiety and depressive symptoms among two seriously medically ill populations and their family caregivers: a comparison and clinical implications. Neurocrit Care. 2017;27(2):180–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Broglio K. Randomization in clinical trials: permuted blocks and stratification. JAMA. 2018;319(21):2223–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jang Y, Hsieh C-L, Wang Y-H, Wu Y-H. A validity study of the WHOQOL-BREF assessment in persons with traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(11):1890–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiu W-T, Huang S-J, Hwang H-F, Tsauo J-Y, Chen C-F, Tsai S-H, et al. Use of the WHOQOL-BREF for evaluating persons with traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23(11):1609–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilz G, Barskova T. Evaluation of a cognitive behavioral group intervention program for spouses of stroke patients. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(10):2508–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fumis RRL, Ferraz AB, de Castro I, de Oliveira HSB, Moock M, Junior JMV. Mental health and quality of life outcomes in family members of patients with chronic critical illness admitted to the intensive care units of two Brazilian hospitals serving the extremes of the socioeconomic spectrum. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9):e0221218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosán H, Ahlström G, Lexán A. Psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-BREF among next of kin to older persons in nursing homes. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Mol M, Visser S, Aerts JGJV, Lodder P de Vries J, den Oudsten BL. Satisfactory results of a psychometric analysis and calculation of minimal clinically important differences of the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF questionnaire in an observational cohort study with lung cancer and mesothelioma patients. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Funes CJ, Mace RA, Macklin EA, Plotkin SR, Jordan JT, Vranceanu A-M. First report of quality of life in adults with neurofibromatosis 2 who are deafened or have significant hearing loss: results of a live-video randomized control trial. J Neurooncol. 2019;143(3):505–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bannon et al. Emotional Distress in Neuro-ICU Survivor-Caregiver Dyads: The Recovering Together Randomized Control Trial. (2021, under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daniels LM, Johnson AB, Cornelius PJ, Bowron C, Lehnertz A, Moore M, et al. Improving quality of life in patients at risk for post–intensive care syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2018;2(4):359–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hawthorne G, Herrman H, Murphy B. Interpreting the WHOQOL-Brèf: preliminary population norms and effect sizes. Soc Indic Res. 2006;77:37–59. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans CH Jr, Ildstad ST, editors; Institute of Medicine Committee on Strategies for Small-Number-Participant Clinical Research Trials. Small clinical trials: issues and challenges. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cuthbertson BH, Roughton S, Jenkinson D, Maclennan G, Vale L. Quality of life in the five years after intensive care: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2010;14(1):R6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dowdy DW, Eid MP, Sedrakyan A, Mendez-Tellez PA, Pronovost PJ, Herridge MS, et al. Quality of life in adult survivors of critical illness: a systematic review of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(5):611–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oeyen SG, Vandijck DM, Benoit DD, Annemans L, Decruyenaere JM. Quality of life after intensive care: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(12):2386–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frick S, Uehlinger DE, Zürcher Zenklusen RM. Assessment of former ICU patients’ quality of life: comparison of different quality-of-life measures. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(10):1405–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.