Abstract

ADAR deaminases catalyze Adenosine-to-Inosine (A-to-I) editing on double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) substrates that regulate an umbrella of biological processes. One of the two catalytically active ADAR enzymes, ADAR1, plays a major role in innate immune responses by suppression of RNA sensing pathways which are orchestrated through the ADAR1-dsRNA-MDA5 axis. Unedited immunogenic dsRNA substrates are potent ligands for the cellular sensor MDA5. Upon activation, MDA5 leads to the induction of interferons and expression of hundreds of interferon-stimulated genes with potent antiviral activity. In this way, ADAR1 acts as a gatekeeper of the RNA sensing pathway by striking a fine balance between innate antiviral responses and prevention of autoimmunity. Reduced editing of immunogenic dsRNA by ADAR1 is strongly linked to the development of common autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. In viral infections, ADAR1 exhibits both antiviral and proviral effects. This is modulated by both editing-dependent and editing-independent functions, such as PKR antagonism. Several A-to-I RNA editing events have been identified in viruses, including in the insidious viral pathogen, SARS-CoV-2 which regulate viral fitness and infectivity, and could play a role in shaping viral evolution. Furthermore, ADAR1 is an attractive target for immuno-oncology therapy. Overexpression of ADAR1 and increased dsRNA editing have been observed in several human cancers. Silencing ADAR1, especially in cancers that are refractory to immune checkpoint inhibitors, is a promising therapeutic strategy for cancer immunotherapy in conjunction with epigenetic therapy. The mechanistic understanding of dsRNA editing by ADAR1 and dsRNA sensing by MDA5 and PKR holds great potential for therapeutic applications.

Graphical Abstract:

1. Introduction to ADAR:

A-to-I editing, one of the most pervasive modifications in RNA, refers to the deamination of adenosine (A) to inosine (I) on double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) substrates and is catalyzed by the adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) group of enzymes (Bass, 2002; Eisenberg & Levanon, 2018; Nishikura, 2010). The cellular translation machinery interprets inosine as guanosine (G) (Licht et al, 2019; Zinshteyn & Nishikura, 2009). In coding regions, A-to-I editing can lead to amino acid changes that differ from the genomically encoded sequence. There are millions of RNA editing sites in the human transcriptome – a very small fraction in protein-coding RNA sequences and the vast majority in non-coding RNA sequences within untranslated regions and introns (Nishikura, 2016; Ramaswami & Li, 2014; Eisenberg & Levanon, 2018). Non-coding RNA editing sites in humans are most frequently observed in inverted Alu repetitive elements (IR-Alu) in which two adjacent Alu elements in opposite orientation in the same transcript form dsRNAs (Chen et al, 2008; Ramaswami et al, 2012).

The ADAR protein family:

A total of three ADAR genes are found in mammals – ADAR1, 2 and 3 (Patterson & Samuel, 1995; Nishikura, 2016) - out of which ADAR3 is catalytically inactive (Figure 1). Alternative splicing of ADAR1 yields two isoforms – a long, interferon inducible isoform p150 and a short isoform p110 that is constitutively expressed (Jain et al, 2019; George et al, 2005; Samuel, 2019). The p150 mRNA can encode both the isoforms due to leaky ribosomal scanning (Sun et al, 2021). All ADARs have dsRNA binding domains, and a catalytic deaminase domain (Savva et al, 2012; Thomas & Beal, 2017; Herbert & Rich, 2001; Phelps et al, 2015). In addition, ADAR1 contains Z-DNA binding domains (Herbert et al, 1997) and ADAR3 contains a ssRNA binding domain rich in Arginine (R domain) at the N-terminus (Chen et al, 2000; Raghava Kurup et al, 2022; Barraud & Allain, 2012). ADAR1p150 contains two Z-DNA binding domains (Zα, Zβ) at the N-terminus while ADAR1p110 has one (Zβ). ADAR1p110 and ADAR2 are localized to the nucleus because of their nuclear localization sequences (Baker & Slack, 2022; Strehblow et al, 2002). On the other hand, ADAR1p150 can shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm due to having both nuclear export and localization sequences but is predominantly cytoplasmic (Zinshteyn & Nishikura, 2009). ADAR1 is widely expressed in all tissues, whereas the expression of ADAR2 and ADAR3 is mostly localized to the brain and a few other organs (Tan et al, 2017).

Figure 1. Domain organization of the ADAR protein family showing key ADAR1 mutations discussed in this review.

Created with BioRender.com

Role of ADAR1 in suppressing RNA sensing:

ADAR1 acts as a gatekeeper of the cellular RNA sensing pathway (Walkley & Li, 2017). Editing of endogenous dsRNA by ADAR1 marks it as “self”. This allows discrimination between cellular, “self” dsRNA and “non-self” dsRNA typically generated during viral infections (Liddicoat et al, 2015), a hallmark of antiviral defense. Non-self dsRNAs from viruses are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), a major component of the innate immune sensing pathway. Cytosolic PRRs of the RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) family including the retinoic acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I) and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) detect unedited dsRNA from viruses. RIG-I recognizes short dsRNA (~50–200 bp) with a 5’-tri or diphosphate (5′-ppp or 5′-pp) end (Ren et al, 2019; Pichlmair et al, 2006). On the other hand, MDA5 oligomerizes on unedited long dsRNA (>200 bp) and assembles as a filament (del Toro Duany et al, 2015; Kato et al, 2006; Peisley et al, 2012; Duic et al, 2020). This activates signaling through the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS), leading to the phosphorylation of transcription factors IRF3 and IRF7. The transcription factors, when present in the nucleus, induce the expression of Type I interferon (IFN) and of hundreds of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) that possess proinflammatory, antiviral activity. In addition, Type I IFN increases expression of MDA5 in a positive feedback loop, leading to an antiviral state (Schlee & Hartmann, 2016; Mogensen, 2009; Dias Junior et al, 2019). Specifically, the cytoplasmic ADAR1p150 isoform negatively regulates the MDA5/MAVS pathway (Pestal et al, 2015). Recent work has illuminated editing sites of ADAR1 isoforms revealing that the ADAR1p150 isoform preferentially editing 3’ UTRs while the ADAR1p110 isoform favoring intronic sites (Kleinova et al, 2023). In addition, ADAR1p150 edits a wider range of targets than ADAR1p110 (Sun et al, 2021, 2023).

ADAR1-dsRNA-MDA5 axis in innate immunity - evidence from mouse genetics:

Key experimental evidence for the role of the ADAR1-dsRNA-MDA5 axis in innate immune sensing was uncovered from mouse genetic studies. ADAR1 inactivation in mice (Adar1−/−) was found to lead to embryonic lethality around embryonic day 12.5 as a result of apoptosis of liver hematopoietic stem cells and elevated ISG expression (Hartner et al, 2009; Wang et al, 2000, 2004). This embryonic lethality was linked to ADAR1 editing activity - mice deficient in ADAR1 editing (Adar1E861A/E861A) also died in utero around embryonic day 13.5 (Liddicoat et al, 2015). Further, deletion of MDA5/MAVS but not the dsRNA sensor protein kinase R (PKR) or RIG-I was found to rescue this embryonic lethality and elevated ISG expression in Adar1 mutant mice (Liddicoat et al, 2015; Mannion et al, 2014; Pestal et al, 2015; Wang et al, 2004). Specifically, the embryonic lethal Adar1E861A/E861A mice are fully rescued to >2 years of life upon the removal of MDA5 (Liddicoat et al, 2015; Heraud-Farlow et al, 2017).

Other RNA sensors that directly suppress viral replication:

Type I IFN induction following MDA5/MAVS signaling leads to the expression of several ISGs encoding PRRs with direct antiviral functions. These include PKR, 2’-5’- oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS) and IFN-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 (IFIT1) (Kristiansen et al, 2010; Sadler & Williams, 2008; Calderon & Conn, 2018; Schwartz & Conn, 2019). OAS degrades dsRNA to produce 2′,5′-oligoadenylate, which activates RNaseL, which degrades viral and cellular RNA. This leads to translation arrest and autophagy to keep viral replication in check (Li et al, 2016). PKR and IFIT1 inhibit 5’-cap-dependent translation to directly block viral replication. Specifically, dsRNA recognition causes PKR activation which dimerizes and phosphorylates the eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), which leads to global translation shutdown and stress granule formation (Chung et al, 2018).

Editing-independent functions of ADAR1:

Although the key role of ADAR1 is A-to-I RNA editing, there are several editing-independent functions as well. Through a mechanism independent of editing, ADAR1 directly interacts with PKR and suppresses its kinase activity leading to blockage of translation arrest (Nie et al, 2007). Studies in human cells revealed that during the IFN response, ADAR1 prevents translational shutdown and apoptosis by preventing hyperactivation of PKR by endogenous RNA (Chung et al, 2018). Perhaps the best evidence of ADAR1’s editing-independent function lies in the fact that Adar1E861A/E861A Ifih1−/− mice are fully rescued to >2 years of life (Liddicoat et al, 2015; Heraud-Farlow et al, 2017), while Adar1−/− Ifih1−/− mice only live for 2 days after birth (Pestal et al, 2015). This is mediated through both ADAR1 catalytic and dsRNA-binding activities (Pfaller et al, 2018). Recently, Adar1−/− Ifih1−/− mice have been successfully rescued to adulthood by removing PKR (encoded by EIF2AK2) (Hu et al, 2023). Furthermore, Adar1p150−/− mice were completely rescued at the Mendelian ratio by concurrent knockout of both MDA5 and PKR, suggesting that MDA5 and PKR are the primary in vivo effectors accounting for the fatal autoinflammation upon the loss of ADAR1p150 (Hu et al, 2023).

ADAR1-dsRNA-MDA5 axis in human genetics:

In humans, ADAR1 functions as a checkpoint to discriminate between self and non-self dsRNA. This enables pathogen detection by the innate immune system, and dysregulation of this pathway leads to autoimmune disease. Aberrant ADAR1 editing and nucleic acid sensing are implicated in several human inflammatory and autoimmune diseases such as Aicardi-Goutières syndrome (AGS), dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (DSH), and bilateral striatal necrosis (BSN) (Pfaller et al, 2018; Weng et al, 2022; Li et al, 2022a; Rice et al, 2012; van Toorn et al, 2023). Loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in ADAR1 and gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in MDA5 (encoded by IFIH1) cause AGS in humans, characterized by chronic IFN-I production. GOF mutations in MDA5 are also implicated in Singleton-Merten syndrome(Rutsch et al, 2015) and systemic lupus erythematosus (Van Eyck et al, 2015). AGS is a well-studied, severe multi-organ inflammatory disease that is strongly linked to mutations in ADAR1, both genetically and clinically (Rice et al, 2020, 2012, 2014; Livingston & Crow, 2016). The exact cause of AGS has not been identified, however several studies shed light on the role of ADAR1 in AGS disease development. Long dsRNAs, primarily formed by inverted Alu repeats, are the primary substrate of endogenous ADAR1 (Bazak et al, 2014; Athanasiadis et al, 2004; Blow et al, 2004; Levanon et al, 2004). This leads to the hypothesis that editing of IR-Alu dsRNAs replaces A:U Watson-Crick base pairs with I:U, leading to structural destabilization or alteration. These destabilized or altered IR-Alu duplexes likely are a poor substrate for MDA5, preventing stable filament formation and MDA5 activation. As a result of insufficient A-to-I editing caused by LOF ADAR1 mutations seen in AGS pathology, MDA5 should efficiently recognize perfect IR-Alu duplexes. This would result in constitutive MDA5 activation through assembly of signaling-competent filaments on unedited, immunogenic IR-Alu dsRNAs. Further, A-to-I editing mediates numerous secondary structural changes in the human transcriptome and silencing ADAR1 increases the ratio of duplex to single stranded RNA (Solomon et al, 2017).

GOF mutations in MDA5 act through a similar mechanism by constitutive activation and over-stabilization of MDA5 filaments. Experimental evidence for this was found from RNase protection assays, where IR-Alu transcripts were found to be protected by recombinant MDA5 from ADAR1-knockout cells (Ahmad et al, 2018; Mehdipour et al, 2020). Overall, AGS disease pathology resulting from constitutive MDA5 activation occurs through loss of immunological self-tolerance to cellular dsRNAs. This points to a key role of retroelements such as IR-Alus functioning as virus-like elements to shape the innate immune system to prevent human disease (Chung et al, 2018).

Recent work by our lab has shed light on the implication of dsRNA editing and sensing in common autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (Li et al, 2022a). The genetic variants that are associated with changes of editing levels of the associated dsRNAs are highly enriched in GWAS signals for common autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, such as type 1 diabetes, psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, lupus, and coronary artery disease. The GWAS-defined risk variants generally reduce the editing of the nearby associated dsRNAs, which results in IFN responses and ISG expression. This suggests that at least a subset of patients for a given inflammatory disease, whose inflammation may be driven by the insufficient editing of cellular dsRNAs, could be mitigated by dampening the dsRNA sensing.

Role of ADAR1 in Z-RNA sensing:

Structural studies have shown that the Zα domain of ADAR1p150 binds to left-handed Z-RNA with high affinity (Koeris et al, 2005; Placido et al, 2007; Herbert et al, 1997; Schwartz et al, 1999). Noncanonical Z-RNA is typically formed in segments of alternate purine–pyrimidine (CG) sequences due to torsional stress caused by RNA polymerase moving through a gene (Schade, 1999; Barraud & Allain, 2012). Oppositely oriented Alu retroelements, their mouse counterparts - B1 and B2 SINE elements, and viral RNA are all capable of adopting the Z-conformation. Recognition of Z-RNA by the Zα domain of ADAR1p150 has been shown to regulate the A-to-I editing activity of ADAR1 (Jiao et al, 2022; de Reuver et al, 2021; Keegan et al, 2021). The Zα domain also mediates the localization of ADAR1p150 to cytoplasmic stress granules during oxidative or IFN-induced stress (Ng et al, 2013). The most common mutation in AGS patients, P193A, resides within this Zα domain of ADAR1p150 (Figure 1). Hemizygous Zα domain mutations, such as P193A mediates Type I-IFN mediated disease pathology in mice and humans (Jiao et al, 2022; Rice et al, 2012, 2017). These defects, in various mouse models, can be rescued by dsRNA sensors MDA5 or PKR (Maurano et al, 2021; Tang et al, 2021; de Reuver et al, 2021; Nakahama et al, 2021; Zillinger & Bartok, 2021).

Other than ADAR1, IFN-induced ZBP1 (Z-DNA binding protein 1) is the only other mammalian protein known to contain Zα domains. Several recent studies have implicated ZBP1 as a novel innate immune sensor that mediates cell death and inflammation in response to ADAR1 Zα domain mutations observed in AGS patients (Hubbard et al, 2022; Jiao et al, 2022; de Reuver et al, 2022). Unedited self-RNA accumulation as a result of loss of function mutations in ADAR1 is recognized by ZBP1. Activation of ZBP1 leads to inflammatory cell death through pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis (PANoptosis) (Karki et al, 2021; Kesavardhana et al, 2020). ADAR1 negatively regulates ZBP1-mediated PANoptosis by interacting with the Zα2 domain of ZBP1, thus promoting tumorigenesis (Karki et al, 2021). In addition, this leads to aberrant activation of sensors MDA5 and PKR, leading to the development of multi-organ inflammation and encephalopathies (Maurano et al, 2021). Using genetically engineered mouse models, several groups have independently shown that hemizygous mutations in ADAR1 - Zα domain mutation on one allele and ADAR null mutation on another allele show severe immunopathologies which cause death shortly after birth. Removal of ZBP1 or its Zα domain binding activity can rescue the immunopathologies caused by ADAR1 Zα domain hemizygous mutations and postnatal lethality.

These data point to a strong interplay between ADAR1 and ZBP1, and the importance of the Zα domain in regulating inflammation, innate immunity and antiviral responses (Wolf & Lee-Kirsch, 2022; Minton, 2022b, 2022a). New evidence suggests that ADAR1 suppresses endogenous Z-RNA formation which prevents ZBP1 activation (Zhang et al, 2022). However, future studies are still needed to dissect the detailed mechanism of ZBP1 in the context of different ADAR1 mutants. Efforts have been made to search for therapeutic ADAR1 inhibitors (Choudhry, 2021; Cottrell et al, 2021; Fritzell et al, 2019) although none exist currently. As an alternate strategy, a small molecule inhibitor of ZBP1, Curaxin CBL0137, has recently been identified that activates ZBP1-mediated necroptosis and reverses immune checkpoint blockade-unresponsiveness in mouse models of human cancers (Zhang et al, 2022). While research has uncovered several pathways by which ADAR1 mediated innate immune signaling, several questions remain to be answered. What Z-RNA substrates regulate ADAR1 and ZBP1? Are there common features and differences between these substrates? How do ADAR1 Zα mutations cause encephalopathies seen in AGS patients? What is the relationship between ZBP1 and other dsRNA sensors such as MDA5 and PKR?

2. Role of ADAR in viral infections, focusing on SARS-CoV-2:

Several viruses produce dsRNAs during transcription and replication, resulting in IFN induction - the first line of antiviral defense. RNA viruses have an error prone RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) which leads to intrinsically higher mutation rates (Duffy et al, 2008). A-to-I editing signatures (A-to-G substitutions) characteristic of ADAR, have been observed during both viral infection and persistence (Samuel, 2011). Depending on virus-host interactions, ADAR1 can be either antagonistic or synergistic to viral replication (Samuel, 2011; Pfaller et al, 2021). This is mediated through editing-dependent functions of ADAR1 such as specific editing of viral RNA or editing of host transcripts that modulate the cellular response. Viral transcripts are often excessively edited in a non-specific phenomenon called hyperediting (Bass et al, 1989; George et al, 2011; Figueroa et al; Kumar & Carmichael, 1997) which regulates viral pathogenesis. ADAR1 also exerts an effect on viral replication through editing independent functions such as PKR antagonism (Clerzius et al, 2009). This leads to altered viral fitness, immune escape or treatment resistance (Samuel, 2011, 2012; Piontkivska et al, 2021; Pfaller et al, 2021). Notably, Pfaller et al. have shown that ablation of ADAR1 in cells leads to immune activation which arrests viral growth. This is mediated through activation of both MDA5/MAVS and PKR - out of which the latter has a stronger effect. This can be reversed by ADAR1p150 complementation which rescues virus growth and dampens the antiviral response. In this way, several viruses use ADAR1 to their advantage to avoid innate immune recognition (Pfaller et al, 2018).

Proviral and antiviral roles of ADAR1.

ADAR1 exerts proviral, antiviral and sometimes dual roles in the context of various viral infections, as outlined below using a few specific examples:

Measles Virus (MeV):

ADAR1, primarily p150, has a proviral effect on MeV by inducing apoptosis, forming stress granules, promoting IFN production, and blocking PKR activation (Toth et al, 2009; Okonski & Samuel, 2013; Li et al, 2012; Pfaller et al, 2018). However, other research also suggests that ADAR1p150 can exert an antiviral effect in persistent MeV infection by triggering hyperediting (Ward et al, 2011).

ADAR1 increases replication of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) through RNA-editing independent mechanisms. It inhibits the kinase activity of PKR and suppresses eIF-2ɑ phosphorylation, thereby increasing VSV infection (Nie et al, 2007; Baltzis et al, 2004).

Hepatitis Delta Virus (HDV):

ADAR1 plays a complex and context-dependent role in HDV infections. Although ADAR1 p150 has an antiviral effect, site-specific editing by ADAR1 p110 at the amber UAG stop codon (W-site) has a proviral effect, promoting genome packaging (Wong & Lazinski, 2002). However, ADAR1 overexpression or IFN treatment inhibits HDV replication (Jayan & Casey, 2002). In addition, HDV employs ADAR1 p110 editing of the W-site as a tightly linked switching mechanism between the early and late stages of its life cycle (Poison et al, 1996).

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV):

ADAR1 has an antiviral activity against HCV replicons through PKR-mediated translation inhibition (Taylor et al, 2005).

Influenza A Virus (IAV):

The nuclear p110 isoform acts antivirally by restricting infection, while the cytoplasmic p150 isoform promotes viral infection by negatively regulating RIG-I signaling (Vogel et al, 2020). Human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1): ADAR1 is proviral for HIV-1 replication (Clerzius et al, 2009), likely through RNA editing independent mechanisms (Pujantell et al, 2019). Direct binding of ADAR1 to HIV-1 p55 Gag facilitates its encapsidation into virions (Orecchini et al, 2015).

Zika virus (ZIKV):

Both ADAR1 knockdown and knockout reduce viral transcription, translation, and titers. Both p150 and p110 isoforms of ADAR1 can restore ZIKV replication by suppressing IFN production and PKR activation (Zhou et al, 2019). Overall, ADAR1 displays a complex interplay of proviral and antiviral roles against different viruses, making it a potential antiviral target in specific virus-host interactions.

A-to-I RNA editing in SARS-CoV-2

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in over 628 million confirmed cases, including over 6.5 million deaths worldwide (WHO COVID-19 Dashboard, accessed November 3, 2022). Coronavirus genomes contain an error prone RdRp, but unlike most other RNA viruses, they also contain an nsp14-ExoN gene with proofreading activity, which leads to lower mutation rates (Ogando et al, 2020). Replication of SARS-CoV-2 in lung epithelial cells was found to induce a delayed IFN response, which is primarily regulated by RLRs - MDA5 and LGP2. Investigation of the molecular pathways of innate immune recognition to SARS-CoV-2 revealed IRF3, IRF5, and NF-kB/p65 as key transcription factors regulating the signaling response (Yin et al, 2021). Coronaviruses use an endoribonuclease, nonstructural protein 15 (nsp15) to evade innate RNA sensors (Deng et al, 2017). MDA5 has been identified as the primary cellular sensor for SARS-CoV-2, that results in the induction of type I and III IFNs in a lung cancer cell line upon infection. IFN induction limits SARS-CoV-2 replication but the resultant cytokine storm has been shown to lead to severe COVID-19. This IFN induction is dependent on the MDA5/MAVS/IRF3 axis.

Using transcriptomic analysis, DiGiorgio et al. identified nucleotide changes in RNA sequences obtained from SARS-CoV-2 infected patients, characteristic of RNA editing. These included both A-to-I changes characteristic of ADAR deaminases and C-to-U changes characteristic of APOBEC deaminases. SNV dataset analysis revealed an underrepresentation of A-to-I changes in viral genomes (editing levels of ~1%). This is suggestive of the fact that ADAR might be more effective than APOBEC at virus restriction (Di Giorgio et al, 2020). This study sampled the SARS-CoV-2 consensus sequences, which is the dominant viral population in a clinical sample. However, patients are most often infected with more than one viral variant. Next generation sequencing has enabled detection of additional minor viral populations in SARS-CoV-2 infected patient samples. A-to-I editing changes were detected in 0.035% of RNA sequences, which were mostly nonsynonymous. Here also, A-to-G changes were rarely observed in the major viral population. Interestingly however, it was the most found to be the common mutation in minor viral populations and also found to increase during severe disease. In minor viral populations, increased A-to-G editing was found to be inversely correlated to viral load, possibly reducing viral infectivity and fitness through antiviral pathways (Ringlander et al, 2022).

Recent studies have mapped an atlas of RNA editing sites in the SARS-CoV-2 genome from RNA-Seq data (Song et al, 2022b). The regulation of A-to-I RNA editing was found to be dynamic and editing levels were found to vary between cell/tissue types and was directly correlated with the intensity of the immune response. ADAR signatures were observed in 91 editing events in viral dsRNA intermediates. Thousands of editing sites were identified from the RNA-Seq data, of which the majority of sites were nonsynonymous and are mostly found in exons (Picardi et al, 2021). 2271 editing hotspots were observed, which included recoding editing sites in the spike protein which affects viral antigenicity and infectivity. In addition, there are 20 overlapping sites between editing hotspots and variants of concern - which strongly suggests that A-to-I editing drives viral evolution. The analysis was largely extendable to identify RNA editing sites in other RNA viruses such as MERS-CoV, Zika virus and Dengue virus as well (Song et al, 2022b). Bioinformatic analyses also independently identified several RNA editing sites in SARS-CoV-2 (Peng et al, 2022). It remains to be understood how A-to-I editing shapes SARS-CoV-2 evolution and determines viral infectivity and spread, to contain and treat the disease. As variants evolve, knowledge of editing hotspots in the spike protein will also guide the design of better vaccines against SARS-CoV-2.

3. Immuno-oncology and ADAR1: targeting players in the dsRNA-ADAR1-MDA5 axis as a therapeutic intervention for cancer:

Immunotherapy engages the immune system to encourage tumor clearance. Antibody mediated blockade of immune checkpoint molecules such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) promotes cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses against tumors and has been the most widely used immunotherapy to date. Despite the clinical success of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in the treatment of some patients, others remain refractory or fail to show durable response, prompting the need for additional therapies. Activating the innate immune system by triggering PRRs is one strategy under ongoing investigation.

The induction of type I (IFNα/β) and type II (IFN-ɣ) IFNs in the tumor microenvironment can promote tumor control by directly triggering cell death or enhancing anti-tumor immune cell activation. As a potent activator of type I IFNs, the MDA5 signaling pathway has been targeted in the tumor context through exogenous synthetic dsRNA analogues and indirectly promoting the release of endogenous dsRNAs. The stabilized version of the dsRNA analog poly-IC, Poly-ICLC, signals through TLR3 and MDA5 and have been shown to enhance cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response in tumors (Sultan et al, 2020). The expression of endogenous dsRNAs in tumors can also be indirectly induced through treatment with DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTIs). Human ovarian cancer and colorectal carcinoma cell lines treated with the DNMTIs 5-azacytidine (5-Aza) or 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (Dac) induce the expression of hypomethylated endogenous retroviral sequences (ERVs) (Chiappinelli et al, 2015; Roulois et al, 2015). This included the expression of sense and antisense ERV transcripts known to be able to form dsRNAs and correlated with the timing of ISG induction. Using the B16-F10 mouse model of melanoma the researchers demonstrated that 5-Aza treatment potentiates antibody mediated inhibition of the immune checkpoint CTLA-4 and tumor clearance. Mehdipour et al. demonstrated that IR-Alu dsRNA are the major source of immunogenic RNA induced upon Dac treatment (Mehdipour et al, 2020). In vitro DAC treatment led to ADAR1 upregulation in patient derived colorectal cancer cells, limiting ISG response. Further, by using immunodeficient NSG mice carrying ectopic human colorectal cancer tumors, they have shown that knockdown of ADAR1 and Dac treatment synergize to significantly decrease tumor burden. These observations suggest that directly targeting ADAR1, a negative regulator of MDA5 signaling, could likewise serve as a strategy to promote immune activation and tumor clearance.

ADAR1 loss leads to increased immunotherapy efficacy

The limited success of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has prompted further studies to dissect the pathways of tumor evasion of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and identify additional targets that could synergize with ICIs to potentiate immune system mediated tumor clearance. To this end, multiple labs have conducted in vitro and in vivo loss-of-function CRISPR screens, with Adar1 consistently appearing as a top hit. In an in vivo CRISPR screen, Manguso et al. compared guides depleted from B16 murine melanoma tumors grown in immunocompetent mice treated with anti-PD-1 to those present in the tumors of mice lacking T cells (Manguso et al, 2017). They have shown that defects in the sensing of and signaling by IFN-ɣ induced resistance to anti-PD-1, with Adar1 loss appearing as a top candidate boosting IC in the screen. Following up on this discovery, Ishizuka et al. examined the mechanism by which ADAR1 loss enhances ICI (Manguso et al, 2017; Ishizuka et al, 2019). They found that the loss of ADAR1 can alone slow the growth of melanoma and colorectal carcinoma tumors, with the effect significantly augmented when used in conjunction with anti-PD-1 treatment. Single cell RNA sequencing of CD45+ immune cells infiltrating into Adar1-null B16 tumors revealed significant increase in CD8+ CTL and decrease in alternatively activated immunosuppressive M2 macrophage and myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). The interplay of tumor intrinsic type I and type II IFN sensing was shown to mediate the sensitivity of Adar1-null tumors to ICI. Loss of MDA5 and PKR individually, but not simultaneously, did not affect ICI sensitivity of Adar1-null tumor cells. Loss of dsRNA sensing by PKR, but not MDA5, was shown to be the major mechanism of IFN-ɣ-dependent growth arrest in vitro. Meanwhile, loss of MDA5 abolished IFNβ secretion to a greater extent than loss of PKR in vitro. In vivo PKR-deficient, but not MDA5-deficient, Adar1-null tumors maintained CD8+ CTL enrichment and absence of MDSC, suggesting that dsRNA sensing by MDA5 is necessary for immune cell infiltration and polarization. Altogether, this detailed study provided mechanistic insight into the distinct pathways that promote ICI efficacy in the absence of ADAR1.

ADAR1 also appeared as a top hit in an in vitro genome-wide CRISPR screen of six murine cancer cell lines (melanoma, renal, breast, and colorectal carcinoma) co-cultured with activated CTLs (Lawson et al, 2020). This work identified 182 cancer intrinsic genes common to at least three of the six cell lines, which when individually perturbed, altered the cell’s sensitivity to CTL-mediated death. Among this core set of genes were negative regulators of IFN-ɣ signaling previously described by Manguso et al., including Adar1. The loss of Adar1 in cancer cells enhanced CTL response in all cell lines except for Renca renal carcinoma, where it was protective. Lawson et al. validated their findings in vivo by showing that Adar1 knockout in B16-F10 melanoma cells leads to significant decrease in tumor burden in immunodeficient NSG mice and near complete tumor regression in immunocompetent mice, highlighting the dependence of sustained tumor clearance on the presence of an intact immune system. Further, through an in vitro CRISPR screen of a murine PDAC KPC model derived cell line with CTLs, Frey et al. identified Adar1 among the top negative regulators of CTL sensitivity to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), a cancer refractory to ICIs due to effective immune evasion (Frey et al, 2022). They confirmed their findings in vivo, showing that inhibition of Adar1 in orthotopic KPC tumors enhanced their CTL mediated clearance.

ADAR1 expression is increased among many cancers

A growing body of research suggests that ADAR1 overexpression and increased ADAR1-mediated dsRNA editing are involved in many cancers and are associated with poor disease outcome (Paz-Yaacov et al, 2015; Han et al, 2015; Fumagalli et al, 2015), as exemplified below:

Multiple myeloma (MM):

Lazzari et al. found that chromosome 1q21 amplification promotes ADAR1 overexpression leading to poor clinical outcomes due to inflammatory cytokine signaling (Lazzari et al, 2017). They showed that ADAR1-mediated recoding of GL1, a player in the Hedgehog signaling and self-renewal agonist, drives malignant regeneration in MM.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

patient samples showed high ADAR1 expression compared to surrounding normal tissue. A large-scale transcriptomic analysis of HCC patient samples showed that ADAR1 overexpression and ADAR2 downregulation led to increased risk of liver cirrhosis and are linked to poor prognosis, and that ADAR1 has oncogenic ability (Chan et al, 2014; Chen et al, 2013).

Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma (PDAC):

ADAR1 is overexpressed in PDAC, leading to increased proliferation via the PI3K/AKT/c-Myc signaling pathway. In PDAC cell lines and subcutaneous tumor models, EZH2 methyltransferase inhibitors were found to regulate the expression of ADAR1 and also overcome resistance to BET inhibitors (Sun et al, 2020). There was also evidence to show that ADAR1 regulates PDAC growth and metastasis through a regulatory circuit that includes circNEIL3 and miR-432–5p (Shen et al, 2021).

Breast Cancer:

ADAR1, especially ADAR1 p150 isoform, shows elevated levels of expression in all breast cancer subtypes including the deadliest form of breast cancer, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Using TCGA breast cancer datasets, studies found that high expression of ADAR1 correlates with poor patient survival. Using TNBC cell-lines, authors have shown that ADAR1 is essential for TNBC tumorigenesis and transformation, and PKR is activated upon ADAR1 loss. ADAR1-dependent TNBC cell lines have increased ISG expression and concurrent loss of IFNAR1, rescues cell death phenotype. These data suggest that type I IFN and PKR signaling pathways might contribute to ADAR1 dependency in TNBC cell lines (Kung et al, 2021). Using immunohistochemistry, authors examined the expression of ADAR1 in 681 TNBC patients and found that 45.8% had high ADAR1 expression. These high ADAR1 expressing tumors also had higher levels of CD8+ CTL infiltration and high IFN-related protein expression like PKR. Moreover, in patient groups with lymph node metastasis, high ADAR1 expression led to poorer patient survival (Song et al, 2017).

Lung Cancer:

ADAR1 gene amplifications were found in a subset of patients with adenocarcinoma and squamous lung cancers and associated with tumor recurrence (Anadón et al, 2016; Amin et al, 2017). ADAR1 promotes cell migration and invasion through RNA editing of FAK mRNA (Amin et al, 2017). ADAR1 copy numbers were negatively correlated with predicted apoptosis and immune cell activation gene signatures in lung adenocarcinoma patients (Sharpnack et al, 2018).

Taken together, these studies suggest that ADAR1 expression promotes tumor growth through the inhibition of type I IFN signaling and RNA editing of various mRNAs that act to increase tumor fitness. It is noteworthy that the overexpression of ADAR1 does not appear to be a cause of cancer (Mendez Ruiz et al, 2023), suggesting that it is likely a consequence in the tumor microenvironment.

ADAR1 regulates IFN signaling via dsRNA sensors, leading to immunosuppressive function in tumors.

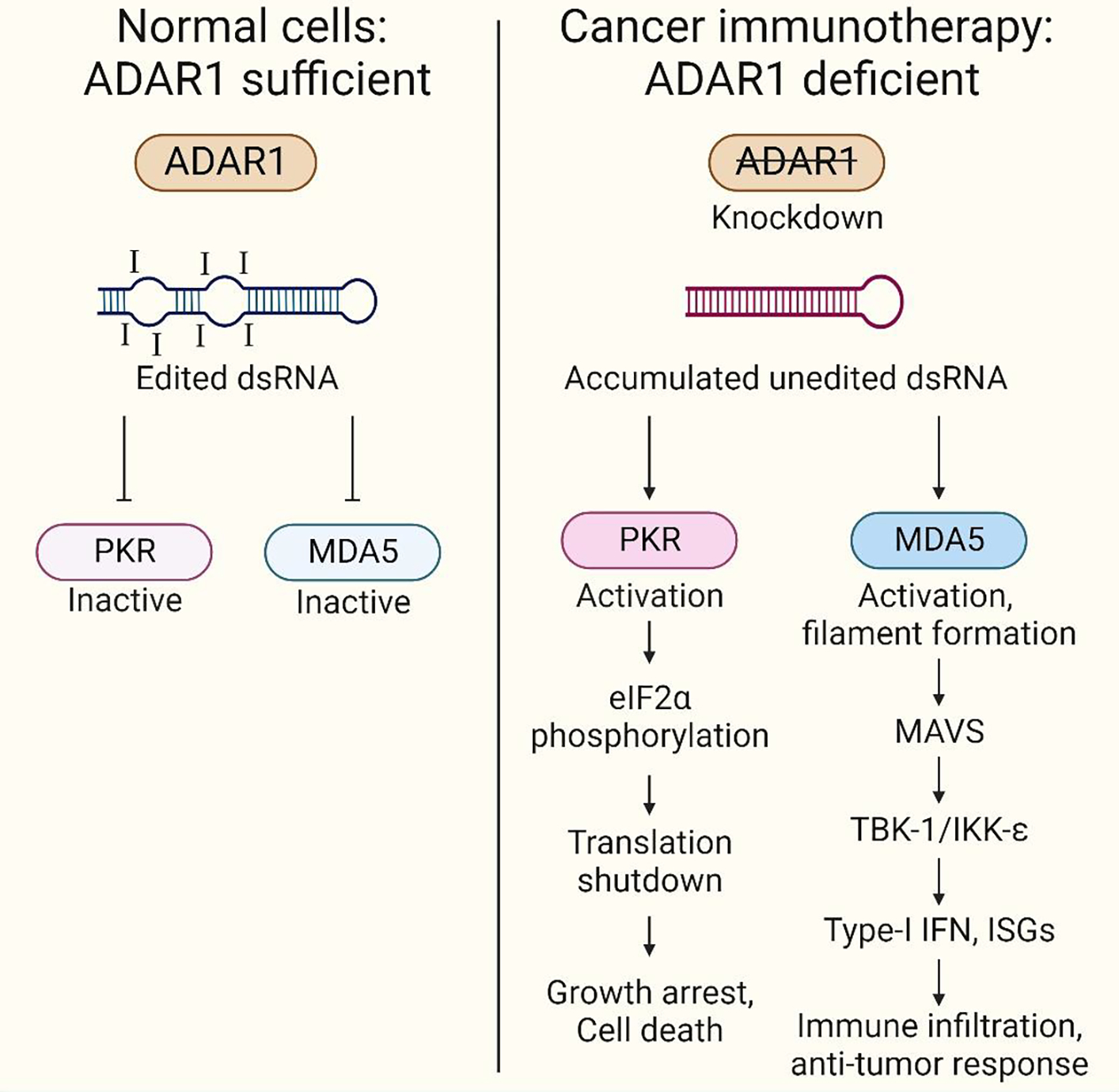

Targeting ADAR1 in tumors could sensitize them to immunotherapy (Gannon et al, 2018; Bhate et al, 2019; Ishizuka et al, 2019; Liu et al, 2019). By analyzing publicly available loss-of-function datasets, Gannon et al. found that select lung and pancreatic cancer cell lines that express high levels of ISGs are vulnerable to ADAR1 deletion. Additionally, when ADAR1 was silenced, IFN-β treatment induced cell death in cell lines that are typically insensitive to ADAR1 loss. Notably, they also found that concurrent knockout of PKR, but not MDA5 or STING, can rescue cell vulnerability to ADAR1 loss. They showed that both catalytic and non-enzymatic functions of the ADAR1 p150 isoform appear to prevent cell death by dampening PKR activation. Moreover, they found that although MDA5/MAVS signaling is not essential for ADAR1 genetic dependency in cancer cell lines, ADAR1 loss primes these cells to produce IFN-β through the pathway, thus amplifying the IFN response (Gannon et al, 2018). Liu et al. found that a subset of primary tumors, even in the absence of IFN-producing immune cell infiltration, elevated ISG expression (Liu et al, 2019). They postulated that it is the tumor cells themselves that could be the source of IFN, thus making them specifically vulnerable to ADAR1 loss (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Loss of ADAR1 in tumors enables sensing of dsRNA by MDA5 and PKR, triggering inflammation, immune infiltration, and tumor cell death as a potent cancer immunotherapy strategy.

In healthy cells, ADAR1 edits cellular dsRNA and marks them as ‘self’ (ADAR sufficiency), masking its recognition by RNA sensors. Under conditions of ADAR deficiency caused due to AGS mutations or ADAR1 inhibition in tumor cells, unedited dsRNAs that accumulate are recognized by cellular RNA sensors such as MDA5 (editing-dependent mechanisms) and PKR (editing-independent mechanisms). This triggers immune activation, including IFN induction, inflammation, and cell death. Immune cells, such as cytotoxic T-cells, dendritic cells and NK cells are drawn to the tumor site due to these signals. This immune infiltration is a crucial step in mounting an anti-tumor response. Leveraging this immune response can be harnessed as a strategy in cancer immunotherapy. Created with BioRender.com

4. Conclusions

One of the most widespread epitranscriptomic modifications, A-to-I RNA editing by ADAR enzymes orchestrates the regulation of the human transcriptome. It does so by modulating a variety of processes such as protein recoding, alternative splicing, gene expression and miRNA biogenesis (Heale et al, 2011; Kung et al, 2018; Christofi & Zaravinos, 2019; Jiang et al, 2017). ADAR1 has a dampening effect in the development of autoimmune disorders (Liddicoat et al, 2015; Mannion et al, 2014; Pestal et al, 2015), which is controlled by the ADAR1-dsRNA-MDA5 axis (Li et al, 2022b). Reduced editing of immunogenic dsRNAs by ADAR1 results in MDA5-dependent IFN induction and expression of up to hundreds of ISGs which is linked to the development of autoimmune diseases. All of these points to the therapeutic benefit of dampening the dsRNA sensing to treat inflammatory and autoimmune conditions. The MDA5-dependent innate immune response exerts an antiviral effect on self and surrounding cells, thereby restricting viral replication. Depending on the virus-host combination, ADAR1 has been shown to play either a proviral or antiviral role (Pfaller et al, 2021; Samuel, 2011) on viral growth, through editing-dependent and editing-independent mechanisms. ADAR1 expression is increased across many tumor types and associated with poor prognosis. Thus, developing potent ADAR1 inhibitors and immunomodulatory MDA5 agonists (Kasumba & Grandvaux, 2019) can be used to treat viral infections, cancers and a spectrum of other human diseases.

Despite decades of research on the subject, several questions remain to be answered: what RNA sequence and structural features regulate the immunogenicity of different MDA5 ligands such as dsRNAs formed by IR-Alu elements? Are these features generalizable or dependent on the type of viral infection? Could knowledge of editing hotspots in viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 drive the design of an effective vaccine? Could ADAR1 inhibition in stromal and immune cells promote tumor clearance? With accelerated developments in recent years, we are moving closer to tackling these challenges and capitalizing on the opportunities they present.

Further Reading.

Rewriting the transcriptome: adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing by ADARs (Walkley & Li, 2017)

The role of RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 in human disease (Song et al, 2022a)

ADAR1, inosine and the immune sensing system: distinguishing self from non-self (Liddicoat et al, 2016)

Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA (ADARs) and Viral Infections (Pfaller et al, 2021)

ADARs: viruses and innate immunity (Samuel, 2012)

ADAR1 entraps sinister cellular dsRNAs, thresholding antiviral responses (Keegan et al, 2021)

ADAR RNA Modifications, the Epitranscriptome and Innate Immunity (Quin et al, 2021)

To protect and modify double-stranded RNA – the critical roles of ADARs in development, immunity and oncogenesis (Erdmann et al, 2021)

Funding Information

The Li lab receives funding from NIH (R35 GM144100) that support work described in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Jin Billy Li is a founder of AIRNA Bio and an advisor of Risen Pharma.

References

- Ahmad S, Mu X, Yang F, Greenwald E, Park JW, Jacob E, Zhang C-Z & Hur S (2018) Breaching Self-Tolerance to Alu Duplex RNA Underlies MDA5-Mediated Inflammation. Cell 172: 797–810.e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin EM, Liu Y, Deng S, Tan KS, Chudgar N, Mayo MW, Sanchez-Vega F, Adusumilli PS, Schultz N & Jones DR (2017) The RNA-editing enzyme ADAR promotes lung adenocarcinoma migration and invasion by stabilizing FAK. Science Signaling 10: eaah3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anadón C, Guil S, Simó-Riudalbas L, Moutinho C, Setien F, Martínez-Cardús A, Moran S, Villanueva A, Calaf M, Vidal A, et al. (2016) Gene amplification-associated overexpression of the RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 enhances human lung tumorigenesis. Oncogene 35: 4407–4413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiadis A, Rich A & Maas S (2004) Widespread A-to-I RNA Editing of Alu-Containing mRNAs in the Human Transcriptome. PLoS Biology 2: e391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AR & Slack FJ (2022) ADAR1 and its implications in cancer development and treatment. Trends in Genetics 38: 821–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltzis D, Qu L-K, Papadopoulou S, Blais JD, Bell JC, Sonenberg N & Koromilas AE (2004) Resistance to Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Infection Requires a Functional Cross Talk between the Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 2α Kinases PERK and PKR. Journal of Virology 78: 12747–12761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraud P & Allain FH-T (2012) ADAR Proteins: Double-stranded RNA and Z-DNA Binding Domains. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 353: 35–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass BL (2002) RNA Editing by Adenosine Deaminases That Act on RNA. Annual Review of Biochemistry 71: 817–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass BL, Weintraub H, Cattaneo R & Billeter MA (1989) Biased hypermutation of viral RNA genomes could be due to unwinding/modification of double-stranded RNA. Cell 56: 331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazak L, Levanon EY & Eisenberg E (2014) Genome-wide analysis of Alu editability. Nucleic Acids Research 42: 6876–6884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhate A, Sun T & Li JB (2019) ADAR1: A New Target for Immuno-oncology Therapy. Molecular Cell 73: 866–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow M, Futreal PA, Wooster R & Stratton MR (2004) A survey of RNA editing in human brain. Genome Research 14: 2379–2387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon BM & Conn GL (2018) A human cellular noncoding RNA activates the antiviral protein 2′–5′-oligoadenylate synthetase 1. Journal of Biological Chemistry 293: 16115–16124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan THM, Lin CH, Qi L, Fei J, Li Y, Yong KJ, Liu M, Song Y, Chow RKK, Ng VHE, et al. (2014) A disrupted RNA editing balance mediated by ADARs (Adenosine DeAminases that act on RNA) in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 63: 832–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CX, Cho DS, Wang Q, Lai F, Carter KC & Nishikura K (2000) A third member of the RNA-specific adenosine deaminase gene family, ADAR3, contains both single- and double-stranded RNA binding domains. RNA 6: 755–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Li Y, Lin CH, Chan THM, Chow RKK, Song Y, Liu M, Yuan Y-F, Fu L, Kong KL, et al. (2013) Recoding RNA editing of AZIN1 predisposes to hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature Medicine 19: 209–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L-L, DeCerbo JN & Carmichael GG (2008) Alu element-mediated gene silencing. EMBO J 27: 1694–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappinelli KB, Strissel PL, Desrichard A, Li H, Henke C, Akman B, Hein A, Rote NS, Cope LM, Snyder A, et al. (2015) Inhibiting DNA Methylation Causes an Interferon Response in Cancer via dsRNA Including Endogenous Retroviruses. Cell 162: 974–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry H (2021) High-throughput screening to identify potential inhibitors of the Zα domain of the adenosine deaminase 1 (ADAR1). Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 28: 6297–6304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christofi T & Zaravinos A (2019) RNA editing in the forefront of epitranscriptomics and human health. Journal of Translational Medicine 17: 319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Calis JJA, Wu X, Sun T, Yu Y, Sarbanes SL, Dao Thi VL, Shilvock AR, Hoffmann H-H, Rosenberg BR, et al. (2018) Human ADAR1 Prevents Endogenous RNA from Triggering Translational Shutdown. Cell 172: 811–824.e14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerzius G, Gélinas J-F, Daher A, Bonnet M, Meurs EF & Gatignol A (2009) ADAR1 Interacts with PKR during Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection of Lymphocytes and Contributes to Viral Replication. Journal of Virology 83: 10119–10128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell KA, Soto-Torres L, Dizon MG & Weber JD (2021) 8-Azaadenosine and 8-Chloroadenosine are not Selective Inhibitors of ADAR. Cancer Research Communications 1: 56–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Hackbart M, Mettelman RC, O’Brien A, Mielech AM, Yi G, Kao CC & Baker SC (2017) Coronavirus nonstructural protein 15 mediates evasion of dsRNA sensors and limits apoptosis in macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114: E4251–E4260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giorgio S, Martignano F, Torcia MG, Mattiuz G & Conticello SG (2020) Evidence for host-dependent RNA editing in the transcriptome of SARS-CoV-2. Science Advances 6: eabb5813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias Junior AG, Sampaio NG & Rehwinkel J (2019) A Balancing Act: MDA5 in Antiviral Immunity and Autoinflammation. Trends in Microbiology 27: 75–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy S, Shackelton LA & Holmes EC (2008) Rates of evolutionary change in viruses: patterns and determinants. Nature Reviews Genetics 9: 267–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duic I, Tadakuma H, Harada Y, Yamaue R, Deguchi K, Suzuki Y, Yoshimura SH, Kato H, Takeyasu K & Fujita T (2020) Viral RNA recognition by LGP2 and MDA5, and activation of signaling through step-by-step conformational changes. Nucleic Acids Research 48: 11664–11674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg E & Levanon EY (2018) A-to-I RNA editing — immune protector and transcriptome diversifier. Nature Reviews Genetics 19: 473–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann EA, Mahapatra A, Mukherjee P, Yang B & Hundley HA (2021) To protect and modify double-stranded RNA - the critical roles of ADARs in development, immunity and oncogenesis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 56: 54–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa T, Boumart I, Coupeau D & Rasschaert D 2016. Hyperediting by ADAR1 of a new herpesvirus lncRNA during the lytic phase of the oncogenic Marek’s disease virus. Journal of General Virology 97: 2973–2988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey N, Tortola L, Egli D, Janjuha S, Rothgangl T, Marquart KF, Ampenberger F, Kopf M & Schwank G (2022) Loss of Rnf31 and Vps4b sensitizes pancreatic cancer to T cell-mediated killing. Nature Communications 13: 1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzell K, Xu L-D, Otrocka M, Andréasson C & Öhman M (2019) Sensitive ADAR editing reporter in cancer cells enables high-throughput screening of small molecule libraries. Nucleic Acids Research 47: e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli D, Gacquer D, Rothé F, Lefort A, Libert F, Brown D, Kheddoumi N, Shlien A, Konopka T, Salgado R, et al. (2015) Principles Governing A-to-I RNA Editing in the Breast Cancer Transcriptome. Cell Reports 13: 277–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon HS, Zou T, Kiessling MK, Gao GF, Cai D, Choi PS, Ivan AP, Buchumenski I, Berger AC, Goldstein JT, et al. (2018) Identification of ADAR1 adenosine deaminase dependency in a subset of cancer cells. Nature Communications 9: 5450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George CX, Gan Z, Liu Y & Samuel CE (2011) Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA, RNA Editing, and Interferon Action. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research 31: 99–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George CX, Wagner MV & Samuel CE (2005) Expression of Interferon-inducible RNA Adenosine Deaminase ADAR1 during Pathogen Infection and Mouse Embryo Development Involves Tissue-selective Promoter Utilization and Alternative Splicing. Journal of Biological Chemistry 280: 15020–15028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L, Diao L, Yu S, Xu X, Li J, Zhang R, Yang Y, Werner HMJ, Eterovic AK, Yuan Y, et al. (2015) The Genomic Landscape and Clinical Relevance of A-to-I RNA Editing in Human Cancers. Cancer Cell 28: 515–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartner JC, Walkley CR, Lu J & Orkin SH (2009) ADAR1 is essential for the maintenance of hematopoiesis and suppression of interferon signaling. Nature Immunology 10: 109–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heale BSE, Keegan LP & O’Connell MA (2011) The Effect of RNA Editing and ADARs on miRNA Biogenesis and Function. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 700: 76–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heraud-Farlow JE, Chalk AM, Linder SE, Li Q, Taylor S, White JM, Pang L, Liddicoat BJ, Gupte A, Li JB, et al. (2017) Protein recoding by ADAR1-mediated RNA editing is not essential for normal development and homeostasis. Genome Biology 18: 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert A, Alfken J, Kim YG, Mian IS, Nishikura K & Rich A (1997) A Z-DNA binding domain present in the human editing enzyme, double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94: 8421–8426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert A & Rich A (2001) The role of binding domains for dsRNA and Z-DNA in the in vivo editing of minimal substrates by ADAR1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98: 12132–12137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S-B, Heraud-Farlow J, Sun T, Liang Z, Goradia A, Taylor S, Walkley CR & Li JB (2023) ADAR1p150 Prevents MDA5 and PKR Activation via Distinct Mechanisms to Avert Fatal Autoinflammation. 2023.01.25.525475 doi: 10.1101/2023.01.25.525475 [PREPRINT] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard NW, Ames JM, Maurano M, Chu LH, Somfleth KY, Gokhale NS, Werner M, Snyder JM, Lichauco K, Savan R, et al. (2022) ADAR1 mutation causes ZBP1-dependent immunopathology. Nature 607: 769–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka JJ, Manguso RT, Cheruiyot CK, Bi K, Panda A, Iracheta-Vellve A, Miller BC, Du PP, Yates KB, Dubrot J, et al. (2019) Loss of ADAR1 in tumours overcomes resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Nature 565: 43–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M, Jantsch MF & Licht K (2019) The Editor’s I on Disease Development. Trends in Genetics 35: 903–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayan GC & Casey JL (2002) Increased RNA editing and inhibition of hepatitis delta virus replication by high-level expression of ADAR1 and ADAR2. Journal of Virology 76: 3819–3827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Crews LA, Holm F & Jamieson CHM (2017) RNA editing-dependent epitranscriptome diversity in cancer stem cells. Nature Reviews Cancer 17: 381–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao H, Wachsmuth L, Wolf S, Lohmann J, Nagata M, Kaya GG, Oikonomou N, Kondylis V, Rogg M, Diebold M, et al. (2022) ADAR1 averts fatal type I interferon induction by ZBP1. Nature 607: 776–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karki R, Sundaram B, Sharma BR, Lee S, Malireddi RKS, Nguyen LN, Christgen S, Zheng M, Wang Y, Samir P, et al. (2021) ADAR1 restricts ZBP1-mediated immune response and PANoptosis to promote tumorigenesis. Cell Reports 37: 109858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasumba DM & Grandvaux N (2019) Therapeutic Targeting of RIG-I and MDA5 Might Not Lead to the Same Rome. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 40: 116–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Matsui K, Uematsu S, Jung A, Kawai T, Ishii KJ, et al. (2006) Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature 441: 101–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan LP, Vukić D & O’Connell MA (2021) ADAR1 entraps sinister cellular dsRNAs, thresholding antiviral responses. Trends in Immunology 42: 953–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesavardhana S, Malireddi RKS, Burton AR, Porter SN, Vogel P, Pruett-Miller SM & Kanneganti T-D (2020) The Zα2 domain of ZBP1 is a molecular switch regulating influenza-induced PANoptosis and perinatal lethality during development. Journal of Biological Chemistry 295: 8325–8330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinova R, Rajendra V, Leuchtenberger AF, Lo Giudice C, Vesely C, Kapoor U, Tanzer A, Derdak S, Picardi E & Jantsch MF (2023) The ADAR1 editome reveals drivers of editing-specificity for ADAR1-isoforms. Nucleic Acids Res 51: 4191–4207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeris M, Funke L, Shrestha J, Rich A & Maas S (2005) Modulation of ADAR1 editing activity by Z-RNA in vitro. Nucleic Acids Research 33: 5362–5370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen H, Scherer CA, McVean M, Iadonato SP, Vends S, Thavachelvam K, Steffensen TB, Horan KA, Kuri T, Weber F, et al. (2010) Extracellular 2′-5′ Oligoadenylate Synthetase Stimulates RNase L-Independent Antiviral Activity: a Novel Mechanism of Virus-Induced Innate Immunity. Journal of Virology 84: 11898–11904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M & Carmichael GG (1997) Nuclear antisense RNA induces extensive adenosine modifications and nuclear retention of target transcripts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94: 3542–3547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung C-P, Cottrell KA, Ryu S, Bramel ER, Kladney RD, Bao EA, Freeman EC, Sabloak T, Maggi L Jr. & Weber JD (2021) Evaluating the therapeutic potential of ADAR1 inhibition for triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene 40: 189–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung C-P, Maggi LB & Weber JD (2018) The Role of RNA Editing in Cancer Development and Metabolic Disorders. Frontiers in Endocrinology 9: 762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson KA, Sousa CM, Zhang X, Kim E, Akthar R, Caumanns JJ, Yao Y, Mikolajewicz N, Ross C, Brown KR, et al. (2020) Functional genomic landscape of cancer-intrinsic evasion of killing by T cells. Nature 586: 120–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzari E, Mondala PK, Santos ND, Miller AC, Pineda G, Jiang Q, Leu H, Ali SA, Ganesan A-P, Wu CN, et al. (2017) Alu-dependent RNA editing of GLI1 promotes malignant regeneration in multiple myeloma. Nature Communications 8: 1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levanon EY, Eisenberg E, Yelin R, Nemzer S, Hallegger M, Shemesh R, Fligelman ZY, Shoshan A, Pollock SR, Sztybel D, et al. (2004) Systematic identification of abundant A-to-I editing sites in the human transcriptome. Nature Biotechnology 22: 1001–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Gloudemans MJ, Geisinger JM, Fan B, Aguet F, Sun T, Ramaswami G, Li YI, Ma J-B, Pritchard JK, et al. (2022a) RNA editing underlies genetic risk of common inflammatory diseases. Nature 608: 569–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Gloudemans MJ, Geisinger JM, Fan B, Aguet F, Sun T, Ramaswami G, Li YI, Ma J-B, Pritchard JK, et al. (2022b) RNA editing underlies genetic risk of common inflammatory diseases. Nature 608: 569–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Banerjee S, Wang Y, Goldstein SA, Dong B, Gaughan C, Silverman RH & Weiss SR (2016) Activation of RNase L is dependent on OAS3 expression during infection with diverse human viruses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113: 2241–2246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Okonski KM & Samuel CE (2012) Adenosine Deaminase Acting on RNA 1 (ADAR1) Suppresses the Induction of Interferon by Measles Virus. Journal of Virology 86: 3787–3794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht K, Hartl M, Amman F, Anrather D, Janisiw MP & Jantsch MF (2019) Inosine induces context-dependent recoding and translational stalling. Nucleic Acids Research 47: 3–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddicoat BJ, Chalk AM & Walkley CR (2016) ADAR1, inosine and the immune sensing system: distinguishing self from non-self. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA 7: 157–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddicoat BJ, Piskol R, Chalk AM, Ramaswami G, Higuchi M, Hartner JC, Li JB, Seeburg PH & Walkley CR (2015) RNA editing by ADAR1 prevents MDA5 sensing of endogenous dsRNA as nonself. Science 349: 1115–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Golji J, Brodeur LK, Chung FS, Chen JT, deBeaumont RS, Bullock CP, Jones MD, Kerr G, Li L, et al. (2019) Tumor-derived IFN triggers chronic pathway agonism and sensitivity to ADAR loss. Nature Medicine 25: 95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JH & Crow YJ (2016) Neurologic Phenotypes Associated with Mutations in TREX1, RNASEH2A, RNASEH2B, RNASEH2C, SAMHD1, ADAR1, and IFIH1: Aicardi-Goutières Syndrome and Beyond. Neuropediatrics 47: 355–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manguso RT, Pope HW, Zimmer MD, Brown FD, Yates KB, Miller BC, Collins NB, Bi K, LaFleur MW, Juneja VR, et al. (2017) In vivo CRISPR screening identifies Ptpn2 as a cancer immunotherapy target. Nature 547: 413–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannion NM, Greenwood SM, Young R, Cox S, Brindle J, Read D, Nellåker C, Vesely C, Ponting CP, McLaughlin PJ, et al. (2014) The RNA-Editing Enzyme ADAR1 Controls Innate Immune Responses to RNA. Cell Reports 9: 1482–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurano M, Snyder JM, Connelly C, Henao-Mejia J, Sidrauski C & Stetson DB (2021) Protein kinase R and the integrated stress response drive immunopathology caused by mutations in the RNA deaminase ADAR1. Immunity 54: 1948–1960.e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehdipour P, Marhon SA, Ettayebi I, Chakravarthy A, Hosseini A, Wang Y, de Castro FA, Loo Yau H, Ishak C, Abelson S, et al. (2020) Epigenetic therapy induces transcription of inverted SINEs and ADAR1 dependency. Nature 588: 169–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez Ruiz S, Chalk AM, Goradia A, Heraud-Farlow J & Walkley CR (2023) Over-expression of ADAR1 in mice does not initiate or accelerate cancer formation in vivo. NAR Cancer 5: zcad023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minton K (2022a) ZBP1 induces immunopathology caused by loss of ADAR1-mediated RNA editing. Nature Reviews Immunology 22: 531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minton K (2022b) ADAR1 inhibits ZBP1 activation by endogenous Z-RNA. Nature Reviews Genetics 23: 581–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen TH (2009) Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 22: 240–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahama T, Kato Y, Shibuya T, Inoue M, Kim JI, Vongpipatana T, Todo H, Xing Y & Kawahara Y (2021) Mutations in the adenosine deaminase ADAR1 that prevent endogenous Z-RNA binding induce Aicardi-Goutières-syndrome-like encephalopathy. Immunity 54: 1976–1988.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SK, Weissbach R, Ronson GE & Scadden ADJ (2013) Proteins that contain a functional Z-DNA-binding domain localize to cytoplasmic stress granules. Nucleic Acids Research 41: 9786–9799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Y, Hammond GL & Yang J-H (2007) Double-stranded RNA deaminase ADAR1 increases host susceptibility to virus infection. Journal of Virology 81: 917–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikura K (2010) Functions and regulation of RNA editing by ADAR deaminases. Annual Review of Biochemistry 79: 321–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikura K (2016) A-to-I editing of coding and non-coding RNAs by ADARs. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 17: 83–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogando NS, Zevenhoven-Dobbe JC, van der Meer Y, Bredenbeek PJ, Posthuma CC & Snijder EJ (2020) The Enzymatic Activity of the nsp14 Exoribonuclease Is Critical for Replication of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Virology 94: e01246–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonski KM & Samuel CE (2013) Stress Granule Formation Induced by Measles Virus Is Protein Kinase PKR Dependent and Impaired by RNA Adenosine Deaminase ADAR1. Journal of Virology 87: 756–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orecchini E, Federico M, Doria M, Arenaccio C, Giuliani E, Ciafrè SA & Michienzi A (2015) The ADAR1 editing enzyme is encapsidated into HIV-1 virions. Virology 485: 475–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JB & Samuel CE (1995) Expression and regulation by interferon of a double-stranded-RNA-specific adenosine deaminase from human cells: evidence for two forms of the deaminase. Molecular and Cellular Biology 15: 5376–5388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz-Yaacov N, Bazak L, Buchumenski I, Porath HT, Danan-Gotthold M, Knisbacher BA, Eisenberg E & Levanon EY (2015) Elevated RNA Editing Activity Is a Major Contributor to Transcriptomic Diversity in Tumors. Cell Reports 13: 267–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peisley A, Jo MH, Lin C, Wu B, Orme-Johnson M, Walz T, Hohng S & Hur S (2012) Kinetic mechanism for viral dsRNA length discrimination by MDA5 filaments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109: E3340–3349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Luo Y, Li H, Guo X, Chen H, Ji X & Liang H (2022) RNA editing increases the nucleotide diversity of SARS-CoV-2 in human host cells. PLOS Genetics 18: e1010130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestal K, Funk CC, Snyder JM, Price ND, Treuting PM & Stetson DB (2015) Isoforms of RNA-Editing Enzyme ADAR1 Independently Control Nucleic Acid Sensor MDA5-Driven Autoimmunity and Multi-organ Development. Immunity 43: 933–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller CK, Donohue RC, Nersisyan S, Brodsky L & Cattaneo R (2018) Extensive editing of cellular and viral double-stranded RNA structures accounts for innate immunity suppression and the proviral activity of ADAR1p150. PLOS Biology 16: e2006577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller CK, George CX & Samuel CE (2021) Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA (ADARs) and Viral Infections. Annual Review of Virology 8: 239–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps KJ, Tran K, Eifler T, Erickson AI, Fisher AJ & Beal PA (2015) Recognition of duplex RNA by the deaminase domain of the RNA editing enzyme ADAR2. Nucleic Acids Research 43: 1123–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardi E, Mansi L & Pesole G (2021) Detection of A-to-I RNA Editing in SARS-COV-2. Genes (Basel) 13: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichlmair A, Schulz O, Tan CP, Näslund TI, Liljeström P, Weber F & Reis e Sousa C (2006) RIG-I-Mediated Antiviral Responses to Single-Stranded RNA Bearing 5’-Phosphates. Science 314: 997–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piontkivska H, Wales-McGrath B, Miyamoto M & Wayne ML (2021) ADAR Editing in Viruses: An Evolutionary Force to Reckon with. Genome Biology and Evolution 13: evab240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placido D, Brown BA, Lowenhaupt K, Rich A & Athanasiadis A (2007) A Left-Handed RNA Double Helix Bound by the Zα Domain of the RNA-Editing Enzyme ADAR1. Structure 15: 395–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poison AG, Bass BL & Casey JL (1996) RNA editing of hepatitis delta virus antigenome by dsRNA-adenosine deaminase. Nature 380: 454–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujantell M, Badia R, Galván-Femenía I, Garcia-Vidal E, de Cid R, Alcalde C, Tarrats A, Piñol M, Garcia F, Chamorro AM, et al. (2019) ADAR1 function affects HPV replication and is associated to recurrent human papillomavirus-induced dysplasia in HIV coinfected individuals. Scientific Reports 9: 19848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quin J, Sedmík J, Vukić D, Khan A, Keegan LP & O’Connell MA (2021) ADAR RNA Modifications, the Epitranscriptome and Innate Immunity. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 46: 758–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghava Kurup R, Oakes EK, Manning AC, Mukherjee P, Vadlamani P & Hundley HA (2022) RNA binding by ADAR3 inhibits adenosine-to-inosine editing and promotes expression of immune response protein MAVS. Journal of Biological Chemistry 298: 102267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswami G & Li JB (2014) RADAR: a rigorously annotated database of A-to-I RNA editing. Nucleic Acids Research 42: D109–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswami G, Lin W, Piskol R, Tan MH, Davis C & Li JB (2012) Accurate identification of human Alu and non-Alu RNA editing sites. Nature Methods 9: 579–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X, Linehan MM, Iwasaki A & Pyle AM (2019) RIG-I Selectively Discriminates against 5′-Monophosphate RNA. Cell Reports 26: 2019–2027.e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Reuver R, Dierick E, Wiernicki B, Staes K, Seys L, De Meester E, Muyldermans T, Botzki A, Lambrecht BN, Van Nieuwerburgh F, et al. (2021) ADAR1 interaction with Z-RNA promotes editing of endogenous double-stranded RNA and prevents MDA5-dependent immune activation. Cell Reports 36: 109500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Reuver R, Verdonck S, Dierick E, Nemegeer J, Hessmann E, Ahmad S, Jans M, Blancke G, Van Nieuwerburgh F, Botzki A, et al. (2022) ADAR1 prevents autoinflammation by suppressing spontaneous ZBP1 activation. Nature 607: 784–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice GI, Kasher PR, Forte GMA, Mannion NM, Greenwood SM, Szynkiewicz M, Dickerson JE, Bhaskar SS, Zampini M, Briggs TA, et al. (2012) Mutations in ADAR1 cause Aicardi-Goutières syndrome associated with a type I interferon signature. Nature Genetics 44: 1243–1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice GI, Kitabayashi N, Barth M, Briggs TA, Burton ACE, Carpanelli ML, Cerisola AM, Colson C, Dale RC, Danti FR, et al. (2017) Genetic, Phenotypic, and Interferon Biomarker Status in ADAR1-Related Neurological Disease. Neuropediatrics 48: 166–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice GI, Park S, Gavazzi F, Adang LA, Ayuk LA, Van Eyck L, Seabra L, Barrea C, Battini R, Belot A, et al. (2020) Genetic and phenotypic spectrum associated with IFIH1 gain-of-function. Human Mutation 41: 837–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice GI, del Toro Duany Y, Jenkinson EM, Forte GM, Anderson BH, Ariaudo G, Bader-Meunier B, Baildam EM, Battini R, Beresford MW, et al. (2014) Gain-of-function mutations in IFIH1 cause a spectrum of human disease phenotypes associated with upregulated type I interferon signaling. Nature Genetics 46: 503–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringlander J, Fingal J, Kann H, Prakash K, Rydell G, Andersson M, Martner A, Lindh M, Horal P, Hellstrand K, et al. (2022) Impact of ADAR-induced editing of minor viral RNA populations on replication and transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119: e2112663119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roulois D, Loo Yau H, Singhania R, Wang Y, Danesh A, Shen SY, Han H, Liang G, Jones PA, Pugh TJ, et al. (2015) DNA-Demethylating Agents Target Colorectal Cancer Cells by Inducing Viral Mimicry by Endogenous Transcripts. Cell 162: 961–973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutsch F, MacDougall M, Lu C, Buers I, Mamaeva O, Nitschke Y, Rice GI, Erlandsen H, Kehl HG, Thiele H, et al. (2015) A Specific IFIH1 Gain-of-Function Mutation Causes Singleton-Merten Syndrome. The American Journal of Human Genetics 96: 275–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler AJ & Williams BRG (2008) Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nature Reviews Immunology 8: 559–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel CE (2011) Adenosine Deaminases Acting on RNA (ADARs) are both Antiviral and Proviral Dependent upon the Virus. Virology 411: 180–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel CE (2012) ADARs: viruses and innate immunity. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 353: 163–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel CE (2019) Adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR1), a suppressor of double-stranded RNA–triggered innate immune responses. Journal of Biological Chemistry 294: 1710–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savva YA, Rieder LE & Reenan RA (2012) The ADAR protein family. Genome Biology 13: 252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schade M (1999) Structure–function analysis of the Z-DNA-binding domain Zα of dsRNA adenosine deaminase type I reveals similarity to the (α + β) family of helix–turn–helix proteins. The EMBO Journal 18: 470–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlee M & Hartmann G (2016) Discriminating self from non-self in nucleic acid sensing. Nature Reviews Immunology 16: 566–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SL & Conn GL (2019) RNA regulation of the antiviral protein 2’-5’-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS). Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA 10: e1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz T, Rould MA, Lowenhaupt K, Herbert A & Rich A (1999) Crystal structure of the Zalpha domain of the human editing enzyme ADAR1 bound to left-handed Z-DNA. Science 284: 1841–1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpnack MF, Chen B, Aran D, Kosti I, Sharpnack DD, Carbone DP, Mallick P & Huang K (2018) Global Transcriptome Analysis of RNA Abundance Regulation by ADAR in Lung Adenocarcinoma. EBioMedicine 27: 167–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen P, Yang T, Chen Q, Yuan H, Wu P, Cai B, Meng L, Huang X, Liu J, Zhang Y, et al. (2021) CircNEIL3 regulatory loop promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression via miRNA sponging and A-to-I RNA-editing. Molecular Cancer 20: 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon O, Di Segni A, Cesarkas K, Porath HT, Marcu-Malina V, Mizrahi O, Stern-Ginossar N, Kol N, Farage-Barhom S, Glick-Saar E, et al. (2017) RNA editing by ADAR1 leads to context-dependent transcriptome-wide changes in RNA secondary structure. Nat Commun 8: 1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B, Shiromoto Y, Minakuchi M & Nishikura K (2022a) The role of RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 in human disease. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA 13: e1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song IH, Kim Y-A, Heo S-H, Park IA, Lee M, Bang WS, Park HS, Gong G & Lee HJ (2017) ADAR1 expression is associated with tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancer. Tumor Biology 39: 1010428317734816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, He X, Yang W, Wu Y, Cui J, Tang T & Zhang R (2022b) Virus-specific editing identification approach reveals the landscape of A-to-I editing and its impacts on SARS-CoV-2 characteristics and evolution. Nucleic Acids Research 50: 2509–2521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehblow A, Hallegger M & Jantsch MF (2002) Nucleocytoplasmic Distribution of Human RNA-editing Enzyme ADAR1 Is Modulated by Double-stranded RNA-binding Domains, a Leucine-rich Export Signal, and a Putative Dimerization Domain. MBoC 13: 3822–3835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan H, Salazar AM & Celis E (2020) Poly-ICLC, a multi-functional immune modulator for treating cancer. Seminars in Immunology 49: 101414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Rosenberg BR, Chung H & Rice CM (2023) Identification of ADAR1 p150 and p110 Associated Edit Sites. Methods Mol Biol 2651: 285–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Yu Y, Wu X, Acevedo A, Luo J-D, Wang J, Schneider WM, Hurwitz B, Rosenberg BR, Chung H, et al. (2021) Decoupling expression and editing preferences of ADAR1 p150 and p110 isoforms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118: e2021757118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Fan J, Wang B, Meng Z, Ren D, Zhao J, Liu Z, Li D, Jin X & Wu H (2020) The aberrant expression of ADAR1 promotes resistance to BET inhibitors in pancreatic cancer by stabilizing c-Myc. American Journal of Cancer Research 10: 148–163 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan MH, Li Q, Shanmugam R, Piskol R, Kohler J, Young AN, Liu KI, Zhang R, Ramaswami G, Ariyoshi K, et al. (2017) Dynamic landscape and regulation of RNA editing in mammals. Nature 550: 249–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q, Rigby RE, Young GR, Hvidt AK, Davis T, Tan TK, Bridgeman A, Townsend AR, Kassiotis G & Rehwinkel J (2021) Adenosine-to-inosine editing of endogenous Z-form RNA by the deaminase ADAR1 prevents spontaneous MAVS-dependent type I interferon responses. Immunity 54: 1961–1975.e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DR, Puig M, Darnell MER, Mihalik K & Feinstone SM (2005) New Antiviral Pathway That Mediates Hepatitis C Virus Replicon Interferon Sensitivity through ADAR1. Journal of Virology 79: 6291–6298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JM & Beal PA (2017) How do ADARs bind RNA? New protein-RNA structures illuminate substrate recognition by the RNA editing ADARs. BioEssays 39: 10.1002/bies.201600187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Toorn R, van Niekerk M, Moosa S, Goussard P & Solomons R (2023) Adar-associated Aicardi Goutières syndrome in a child with bilateral striatal necrosis and recurrent episodes of transaminitis. BMJ Case Rep 16: e252436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Toro Duany Y, Wu B & Hur S (2015) MDA5—filament, dynamics and disease. Current Opinion in Virology 12: 20–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth AM, Li Z, Cattaneo R & Samuel CE (2009) RNA-specific adenosine deaminase ADAR1 suppresses measles virus-induced apoptosis and activation of protein kinase PKR. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 284: 29350–29356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eyck L, De Somer L, Pombal D, Bornschein S, Frans G, Humblet-Baron S, Moens L, de Zegher F, Bossuyt X, Wouters C, et al. (2015) Brief Report: IFIH1 Mutation Causes Systemic Lupus Erythematosus With Selective IgA Deficiency. Arthritis Rheumatol 67: 1592–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel OA, Han J, Liang C-Y, Manicassamy S, Perez JT & Manicassamy B (2020) The p150 Isoform of ADAR1 Blocks Sustained RLR signaling and Apoptosis during Influenza Virus Infection. PLOS Pathogens 16: e1008842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkley CR & Li JB (2017) Rewriting the transcriptome: adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing by ADARs. Genome Biology 18: 205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Khillan J, Gadue P & Nishikura K (2000) Requirement of the RNA Editing Deaminase ADAR1 Gene for Embryonic Erythropoiesis. Science 290: 1765–1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Miyakoda M, Yang W, Khillan J, Stachura DL, Weiss MJ & Nishikura K (2004) Stress-induced apoptosis associated with null mutation of ADAR1 RNA editing deaminase gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry 279: 4952–4961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SV, George CX, Welch MJ, Liou L-Y, Hahm B, Lewicki H, de la Torre JC, Samuel CE & Oldstone MB (2011) RNA editing enzyme adenosine deaminase is a restriction factor for controlling measles virus replication that also is required for embryogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108: 331–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]