Abstract

Background and Objective:

The reported impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on child maltreatment in the U.S. have been mixed. Encounter trends for child physical abuse within pediatric emergency departments (ED) may provide insights. Thus, this study sought to determine the change in ED rate of encounters related to child physical abuse.

Methods:

A retrospective study within the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) Registry. Encounters related to child physical abuse were identified by three methods: child physical abuse diagnoses among all ages, age-restricted high-risk injury, or age-restricted skeletal survey completion. The primary outcomes were encounter rates per day and clinical severity before (January 2018-March 2020) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (April 2020-March 2021). Multivariable Poisson regression models were fit to estimate rate ratios with marginal estimation methods.

Results:

Encounter rates decreased significantly during the pandemic for two of three identification methods. In fully adjusted models, encounter rates were reduced by 19% in the diagnosis-code cohort (Adjusted Rate Ratio [ARR] 0.81 [99% CI 0.75, 0.88], p<0.001) with greatest reduction among preschool and school-age children. Encounter rates decreased 10% in the injury cohort (ARR 0.90 [0.82,0.98], p=0.002). For all three methods, rates for lower severity encounters were significantly reduced while higher severity encounters were not.

Conclusions:

Encounter rates for child physical abuse were reduced or unchanged. Reductions were greatest for lower severity encounters and preschool and school age children. This pattern calls for critical assessment to clarify whether pandemic changes led to true reductions versus decreased recognition of child physical abuse.

Article Table of Contents Summary:

This multicenter assessment of emergency healthcare related to child physical abuse assesses for changes in encounter rate and severity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

Child abuse and neglect occur within multiple layers of risk and protective factors. Family level factors such as mental health and substance use impact the likelihood of maltreatment.1,2 Disruptive events at community and society levels, such as financial recession and natural disaster, also increase the risk for physical abuse.3–7 Thus, the early days of the SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19) pandemic prompted safety concerns for children given reports of increased mental health crises, intimate partner violence, and disruption of daily routines.8–17

Available results have been mixed with regard to the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on child maltreatment, likely related to data sources and definitions.18–21 Single-center healthcare studies have suggested increases in sentinel injuries, sexual abuse, and neglect early in the pandemic.22–26 Conversely, multicenter analyses have reported reduced hospitalizations for physical abuse, including abusive head trauma, during a similar period.27,28 Relatedly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention documented an initial precipitous decline in emergency healthcare use related to maltreatment including physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect, followed by a return to previous levels.29 Finally, child protective services (CPS) data showed substantial declines in report numbers across multiple jurisdictions, a signal reflective of all types of child maltreatment and reporting sources.30–33 Nuanced understanding of experiences of children during the pandemic is critical for proximate and future public health planning.

Emergency healthcare encounters for physical abuse can provide broad yet nuanced insights as a composite indicator impacted by injury severity and abuse recognition per the clinical experience that children with high-severity injuries receive emergency healthcare related to acute medical needs, independent of recognition interactions, while children with low-severity injuries are more likely receive emergency healthcare related to risk recognized through recognition interactions. Thus, if decreased reports to CPS result from a true decline in child physical abuse incidence, we would expect consistent decreases in emergency department (ED) encounters related to abuse concerns across severity levels. Alternatively, if decreased recognition of abuse is a primary driver of the reduction in reports to CPS, we would expect reductions in low-severity ED encounters related to child physical abuse while high-severity encounters would remain constant.

Overall, we hypothesized that the rate of ED encounters related to child physical abuse with high severity would not change during the pandemic while the rate of encounters with low severity would decrease. To expand upon prior research, we assessed a full year of pandemic clinical data from the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) Registry, allowing for multicenter analysis including clinical severity.34 Thus, our assessment of physical abuse encounter rates within emergency healthcare settings may provide additional clarity to experience of children.

Methods

Study Design:

We conducted a multicenter retrospective study using data from the PECARN Registry from January 1, 2018 through March 31, 2021.34 PECARN Registry participation was approved by the institutional review boards of all study sites and the Data Coordinating Center.

Data Source:

The PECARN Registry comprises electronic medical health record (EHR) data from every ED patient encounter at participating institutions, harmonized into a deidentified, central repository.34 Variables include standardized demographics (race, ethnicity, age, sex, insurance type), clinical care orders, laboratory and radiology results, International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coded diagnoses and dispositions. This study included nine participating institutions.

Encounter Identification:

Three methods were used to identify ED encounters related to child physical abuse: (1) diagnosis-codes: child abuse diagnosis by at least one ICD-10-CM code indicative of suspected or confirmed abuse (eTable 1), (2) injury-codes: an ICD code for injury associated with diagnosis of abuse in certain, young age groups (eTable 2), (3) skeletal-survey cohort: evaluation of potential child physical abuse by skeletal survey radiographic study in children younger than 24 months.35–38 Visits identified by the three methods were treated as separate subgroups in analyses; an encounter could be included in more than one subgroup.

For the injury-code cohort, ICD-9-CM injury-codes associated with a high specificity for child physical abuse were identified from the literature and converted to ICD-10-CM codes using general equivalence mapping.35 Using a consensus process, three authors (BHC, JNW, DML) reviewed the ICD-10-CM codes to ensure they represented injuries associated with a high risk of abuse. To increase specificity, exclusionary ICD codes representing motor vehicle crashes, birth injuries, metabolic bone diseases, bleeding disorders, or follow-up visit were applied (eTable 3).39

Encounter characteristics:

Demographic characteristics included age at encounter, insurance type (private, Medicaid, self-pay), and composite race and ethnicity. Race and ethnicity were hierarchically categorized by ethnicity (Hispanic or Non-Hispanic) and then by race within the Non-Hispanic group. Due to limited sample sizes, Non-Hispanic racial categories were analyzed as Black, White, and additional racial group (including American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Multiple Races, and Other). Race and ethnicity were included in analyses due to documented differential COVID-19 pandemic experiences by groups.40 Furthermore, the likelihood to seek emergency healthcare and for clinicians to consider abuse may differ by racial and ethnic group.41–43 Exposure to pandemic related changes was defined by date: before the pandemic (January 1, 2018 - March 31, 2020) or during the pandemic (April 1, 2020 - March 31, 2021).

Clinical severity was assessed by injury severity measures and clinical disposition. Injury severity measures included: triage acuity defined by emergency severity index (ESI), injury severity scores and disposition.44 Injury severity scores were tabulated from ICD-10-CM codes with two methods: Maximum Abbreviated Injury Score (MAIS; 0: none, 1: minor, 2: moderate, 3: serious, 4: severe, 5: critical, 6: maximum; categories analyzed as 0–2, 3–6) and Injury Severity Scale (ISS; range 0–75, sum of squares of highest AIS scores for 3 most severely injured body regions; categories analyzed as 0–8, 9–15, >16).45–48 Clinical disposition included ED visit disposition of discharged, admitted, transferred, or died; and ED or hospital disposition vital status of alive or deceased.

Statistical analysis:

Average daily rates of child abuse encounters and all PECARN Registry encounters were calculated for each calendar month and pandemic time period and plotted over time in order to visualize absolute and relative temporal patterns.

We described the number and rate per day of child abuse encounters overall as well as for each demographic and clinical characteristic of interest. For each characteristic, a “partially adjusted” multivariable Poisson regression model including an interaction between pandemic time period and the characteristic was fit to estimate rate ratios comparing pandemic rates to pre-pandemic rates while controlling for calendar month and clinical site for each of the three cohorts. The fully adjusted daily encounter rate models were generated with age, sex, race/ethnicity, primary payer, calendar month, site, ISS as severity measure, and an interaction term between ISS and pandemic time period, as well as interaction terms between pandemic time period and demographic covariates if the test for the interaction in the partially adjusted model had p<0.10. Fully adjusted rate ratios and 99% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated for overall encounters and each severity level using marginal estimation methods to average over other model covariates.34

Due to strong correlations between clinical severity measures, separate, fully adjusted models were fit for each measure of clinical severity (MAIS, triage ESI level, ED disposition, and vital status) with covariates as listed above.

Due to large sample size, we used a significance level of 0.10 for tests of interactions and 0.01 for all other tests of statistical significance. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. Encounters with missing data were excluded. We performed all analyses using SAS/STAT software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

After application of exclusion criteria, a total of 1,579,014 ED encounters were identified in the PECARN registry including 10,270 (0.7%) as possible child physical abuse (Figure 1). 315 (3.1%) of the abuse encounters were excluded due to missing data.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram.

Encounter Rates

Diagnosis-code cohort:

Encounter rates as identified by child abuse diagnosis codes (diagnosis-code cohort) decreased from 4.6 encounters per day pre-pandemic to 3.8 encounters per day during the pandemic, with month and site adjusted (“partially adjusted”) rate ratio of 0.82 (99% CI: 0.73, 0.92; p<0.001, Table 1). Differences were noted by age in partially adjusted analysis with decreased encounter rates for children aged 2 to <6 years (RR 0.70 [0.58, 0.85], p<0.001) and 6 to <13 years (RR 0.79 [0.64, 0.98], p=0.004), but no significant change for children less than 2 or greater than 13. There was also a decrease for children reported as Black Non-Hispanic (RR 0.78 [0.64, 0.96], p=0.002) and White Non-Hispanic (RR 0.80 [0.65, 0.99], p=0.006) with no change for children recorded as Hispanic. Encounters with public insurance decreased significantly (RR 0.81 [0.70, 0.93], p<0.001) without changes in rates for self-pay or private insurance encounters. Encounter trends were also variable by site with two of nine institutions having significantly reduced daily diagnosis rates. Upon full adjustment with marginal estimation to average over model covariates including ISS, the overall reduction in encounter rate during the pandemic in the diagnosis-code cohort was 19% (adjusted rate ratio [ARR] 0.81 [0.75, 0.88], p<0.001).

Table 1.

Rates of Child Abuse Encounters by Pandemic Time Period (Diagnosis-Code Cohort)

| Before Pandemic: Encounters per day (N) | During Pandemic: Encounters per day (N) | Unadjusted Rate Ratio | Partially Adjusted Rate Ratio (99% CI)1 | p-value | Fully Adjusted Rate Ratio (99% CI)2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 4.57 (3755) | 3.76 (1372) | 0.82 | 0.82 (0.73,0.92) | <.001 | 0.81 (0.75,0.88) | <.001 |

| Age | |||||||

| 0-<6 months | 0.80 (656) | 0.74 (269) | 0.93 | 0.92 (0.74,1.15) | .33 | ||

| 6-<12 months | 0.44 (365) | 0.41 (149) | 0.93 | 0.92 (0.68,1.23) | .44 | ||

| 12-<24 months | 0.53 (439) | 0.44 (160) | 0.83 | 0.82 (0.62,1.08) | .06 | ||

| 2-<6 years | 1.24 (1015) | 0.87 (317) | 0.70 | 0.70 (0.58,0.85) | <.001 | ||

| 6-<13 years | 0.98 (806) | 0.78 (284) | 0.80 | 0.79 (0.64,0.98) | .004 | ||

| 13-<18 years | 0.58 (474) | 0.53 (193) | 0.91 | 0.91 (0.70,1.18) | .37 | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 2.09 (1716) | 1.75 (638) | 0.84 | 0.83 (0.72,0.96) | .001 | ||

| Male | 2.48 (2039) | 2.01 (734) | 0.81 | 0.81 (0.71,0.92) | <.001 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 0.51 (421) | 0.45 (164) | 0.88 | 0.87 (0.60,1.28) | .36 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Additional Racial Groups | 0.42 (342) | 0.41 (151) | 0.98 | 0.99 (0.66,1.48) | .95 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.84 (1507) | 1.44 (526) | 0.78 | 0.78 (0.64,0.96) | .002 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.81 (1485) | 1.45 (531) | 0.80 | 0.80 (0.65,0.99) | .006 | ||

| Primary Payer | |||||||

| Private | 0.87 (711) | 0.82 (300) | 0.94 | 0.95 (0.72,1.24) | .60 | ||

| Public | 3.39 (2787) | 2.75 (1002) | 0.81 | 0.81 (0.70,0.93) | <.001 | ||

| Self-pay | 0.31 (257) | 0.19 (70) | 0.61 | 0.61 (0.36,1.04) | .02 | ||

| Site | |||||||

| A | 1.00 (825) | 0.71 (259) | 0.71 | 0.70 (0.55,0.90) | <.001 | ||

| B | 0.91 (750) | 0.65 (239) | 0.71 | 0.71 (0.55,0.93) | <.001 | ||

| C | 0.74 (607) | 0.56 (205) | 0.76 | 0.76 (0.57,1.01) | .012 | ||

| D | 0.56 (456) | 0.46 (169) | 0.82 | 0.83 (0.61,1.14) | .13 | ||

| E | 0.50 (407) | 0.48 (175) | 0.96 | 0.96 (0.70,1.33) | .77 | ||

| F | 0.38 (316) | 0.38 (137) | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.68,1.39) | .84 | ||

| G | 0.19 (159) | 0.22 (82) | 1.16 | 1.16 (0.72,1.86) | .43 | ||

| H | 0.21 (175) | 0.19 (71) | 0.90 | 0.91 (0.56,1.49) | .62 | ||

| I | 0.07 (60) | 0.10 (35) | 1.43 | 1.31 (0.62,2.76) | .35 | ||

| ISS | |||||||

| 0–8 | 3.94 (3234) | 3.17 (1158) | 0.80 | 0.80 (0.72,0.90) | <.001 | 0.80 (0.73,0.87) | <.001 |

| 9–15 | 0.55 (452) | 0.50 (184) | 0.91 | 0.91 (0.69,1.22) | .42 | 0.91 (0.72,1.14) | .27 |

| 16+ | 0.08 (69) | 0.08 (30) | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.48,2.00) | .93 | 0.97 (0.55,1.70) | .89 |

| MAIS | |||||||

| 0–2 | 3.97 (3257) | 3.21 (1172) | 0.81 | 0.81 (0.72,0.91) | <.001 | 0.80 (0.73,0.88) | <.001 |

| 3–6 | 0.61 (498) | 0.55 (200) | 0.90 | 0.90 (0.68,1.20) | .35 | 0.90 (0.72,1.11) | .19 |

| Triage Category | |||||||

| ESI1 | 0.18 (144) | 0.16 (58) | 0.89 | 0.90 (0.47,1.74) | .69 | 0.90 (0.60,1.34) | .49 |

| ESI2 | 1.73 (1419) | 1.43 (522) | 0.83 | 0.83 (0.67,1.02) | .02 | 0.82 (0.72,0.94) | <.001 |

| ESI3 | 1.94 (1596) | 1.67 (611) | 0.86 | 0.86 (0.70,1.05) | .05 | 0.85 (0.76,0.97) | <.001 |

| ESI4 | 0.64 (524) | 0.41 (150) | 0.64 | 0.64 (0.44,0.95) | .003 | 0.64 (0.50,0.81) | <.001 |

| ESI5 | 0.04 (29) | 0.05 (18) | 1.25 | 1.39 (0.40,4.91) | .50 | 1.38 (0.64,3.00) | .28 |

| ED Disposition 3 | |||||||

| Admitted/Transferred/Died | 1.32 (1082) | 1.14 (417) | 0.86 | 0.86 (0.71,1.06) | .06 | 0.86 (0.74,1.00) | .009 |

| Discharged | 2.83 (2327) | 2.23 (813) | 0.79 | 0.78 (0.68,0.90) | <.001 | 0.78 (0.70,0.87) | <.001 |

| Death 3 | |||||||

| No | 4.16 (3412) | 3.37 (1231) | 0.81 | 0.81 (0.72,0.91) | <.001 | 0.80 (0.74,0.88) | <.001 |

| Yes | 0.03 (27) | 0.01 (4) | 0.33 | 0.33 (0.05,2.08) | .12 | 0.33 (0.08,1.31) | .04 |

Partially adjusted estimates come from separate multivariable Poisson regression models for each characteristic, each with the following covariates: pandemic time period, site, calendar month, and an interaction between pandemic time period and the characteristic. Estimates and confidence intervals represent the contrast within each characteristic (e.g. Hispanic ethnicity) of rates during the pandemic period compared to the pre-pandemic period.

Fully adjusted estimates come from separate multivariable Poisson regression models for each severity indicator, each with the following covariates: pandemic time period, age, sex, race/ethnicity, primary payer, site, calendar month and pandemic time period interactions with site and severity. The overall estimate is reported from the multivariable ISS model.

All visits from Site F were excluded from ED disposition and death models due to incomplete disposition data.

Injury-code cohort:

Encounter rates for high-risk injuries (injury-code cohort) also had a statistically significant reduction by partial adjustment (3.28 to 2.95 encounters per day, RR 0.90 [0.81, 0.99], p=0.007, Table 2). There were no significant differences by specific demographic characteristic categories between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods. After full adjustment, the reduction in encounter rate was 10% (ARR 0.90 [0.82, 0.98], p=0.002).

Table 2.

Rates of Child Abuse Encounters by Pandemic Time Period (Injury-Code Cohort)

| Before Pandemic: Encounters per day (N) | During Pandemic: Encounters per day (N) | Unadjusted Rate Ratio | Partially Adjusted Rate Ratio (99% CI)1 | p-value | Fully Adjusted Rate Ratio (99% CI)2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 3.28 (2693) | 2.95 (1078) | 0.90 | 0.90 (0.81,0.99) | .007 | 0.90 (0.82,0.98) | .002 |

| Age | |||||||

| 0-<6 months | 2.09 (1713) | 1.88 (685) | 0.90 | 0.90 (0.79,1.01) | .02 | ||

| 6-<12 months | 0.99 (809) | 0.92 (335) | 0.93 | 0.93 (0.78,1.11) | .28 | ||

| 12-<24 months | 0.21 (171) | 0.16 (58) | 0.76 | 0.76 (0.50,1.15) | .09 | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 1.54 (1261) | 1.35 (494) | 0.88 | 0.88 (0.76,1.01) | .02 | ||

| Male | 1.74 (1432) | 1.60 (584) | 0.92 | 0.91 (0.80,1.04) | .08 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 0.50 (411) | 0.48 (175) | 0.96 | 0.95 (0.71,1.28) | .68 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Additional Racial Groups | 0.35 (290) | 0.37 (134) | 1.06 | 1.04 (0.74,1.45) | .79 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.91 (745) | 0.73 (268) | 0.80 | 0.81 (0.64,1.02) | .02 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.52 (1247) | 1.37 (501) | 0.90 | 0.90 (0.76,1.07) | .11 | ||

| Primary Payer | |||||||

| Private | 1.17 (963) | 1.13 (412) | 0.97 | 0.96 (0.80,1.15) | .55 | ||

| Public | 2.00 (1638) | 1.75 (638) | 0.88 | 0.87 (0.76,1.01) | .014 | ||

| Self-pay | 0.11 (92) | 0.08 (28) | 0.73 | 0.68 (0.35,1.32) | .13 | ||

| Site | |||||||

| A | 0.53 (435) | 0.42 (154) | 0.79 | 0.79 (0.61,1.04) | .03 | ||

| B | 0.47 (382) | 0.39 (142) | 0.83 | 0.83 (0.63,1.10) | .09 | ||

| C | 0.40 (328) | 0.36 (131) | 0.90 | 0.89 (0.67,1.20) | .33 | ||

| D | 0.58 (473) | 0.51 (185) | 0.88 | 0.88 (0.68,1.12) | .17 | ||

| E | 0.35 (291) | 0.33 (120) | 0.94 | 0.92 (0.68,1.26) | .51 | ||

| F | 0.34 (283) | 0.36 (130) | 1.06 | 1.03 (0.76,1.39) | .81 | ||

| G | 0.33 (272) | 0.35 (127) | 1.06 | 1.05 (0.77,1.42) | .71 | ||

| H | 0.14 (116) | 0.12 (43) | 0.86 | 0.83 (0.50,1.39) | .35 | ||

| I | 0.14 (113) | 0.13 (46) | 0.93 | 0.91 (0.55,1.51) | .64 | ||

| ISS | |||||||

| 0–8 | 2.01 (1650) | 1.71 (624) | 0.85 | 0.85 (0.75,0.96) | <.001 | 0.85 (0.75,0.96) | <.001 |

| 9–15 | 1.16 (951) | 1.15 (418) | 0.99 | 0.98 (0.84,1.15) | .81 | 0.98 (0.85,1.15) | .80 |

| 16+ | 0.11 (92) | 0.10 (36) | 0.91 | 0.88 (0.51,1.49) | .53 | 0.88 (0.53,1.45) | .50 |

| MAIS | |||||||

| 0–2 | 2.03 (1666) | 1.73 (633) | 0.85 | 0.85 (0.75,0.97) | .001 | 0.85 (0.75,0.96) | <.001 |

| 3–6 | 1.25 (1027) | 1.22 (445) | 0.98 | 0.97 (0.83,1.14) | .63 | 0.97 (0.84,1.12) | .60 |

| Triage Category | |||||||

| ESI1 | 0.24 (194) | 0.21 (76) | 0.88 | 0.88 (0.58,1.34) | .43 | 0.88 (0.62,1.24) | .34 |

| ESI2 | 1.05 (863) | 0.98 (358) | 0.93 | 0.93 (0.76,1.13) | .34 | 0.93 (0.79,1.09) | .25 |

| ESI3 | 1.17 (960) | 1.12 (410) | 0.96 | 0.96 (0.80,1.15) | .54 | 0.96 (0.82,1.11) | .46 |

| ESI4 | 0.65 (537) | 0.55 (199) | 0.85 | 0.83 (0.64,1.08) | .07 | 0.83 (0.67,1.03) | .03 |

| ESI5 | 0.08 (67) | 0.05 (17) | 0.63 | 0.57 (0.24,1.33) | .09 | 0.57 (0.28,1.15) | .04 |

| ED Disposition 3 | |||||||

| Admitted/Transferred/Died | 1.32 (1081) | 1.21 (441) | 0.92 | 0.92 (0.79,1.07) | .14 | 0.92 (0.79,1.06) | .12 |

| Discharged | 1.60 (1317) | 1.39 (506) | 0.87 | 0.86 (0.75,0.99) | .007 | 0.86 (0.75,0.99) | .005 |

| Death 3 | |||||||

| No | 2.91 (2388) | 2.59 (945) | 0.89 | 0.89 (0.80,0.99) | .006 | 0.89 (0.80,0.98) | .002 |

| Yes | 0.03 (22) | 0.01 (3) | 0.33 | 0.31 (0.05,1.78) | .08 | 0.31 (0.06,1.49) | .05 |

Partially adjusted estimates come from separate multivariable Poisson regression models for each characteristic, each with the following covariates: pandemic time period, site, calendar month, and an interaction between pandemic time period and the characteristic. Estimates and confidence intervals represent the contrast within each characteristic (e.g. Hispanic ethnicity) of rates during the pandemic period compared to the pre-pandemic period.

Fully adjusted estimates come from separate multivariable Poisson regression models for each severity indicator, each with the following covariates: pandemic time period, age, sex, race/ethnicity, primary payer, site, and calendar month and interactions between pandemic time period and severity. The overall estimate is reported from the multivariable ISS model.

All visits from Site F were excluded from ED disposition and death models due to incomplete disposition data.

Skeletal survey cohort:

Encounter rates for child physical abuse evaluation by skeletal survey completion (skeletal survey cohort) did not have a statistically significant reduction by partial adjustment (3.8 to 3.5 encounters per day, RR 0.92 [0.84, 1.01], p=0.03, Table 3). There were no significant differences in demographic factors between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods. After full adjustment, there was not a significant reduction in encounter rate for the skeletal-survey cohort (ARR 0.92 [0.84, 1.00], p=0.013).

Table 3.

Rates of Child Abuse Encounters by Pandemic Time Period (Skeletal-Survey Cohort)

| Before Pandemic: Encounters per day (N) | During Pandemic: Encounters per day (N) | Unadjusted Rate Ratio | Partially Adjusted Rate Ratio (99% CI)1 | p-value | Fully Adjusted Rate Ratio (99% CI)2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 3.78 (3106) | 3.48 (1270) | 0.92 | 0.92 (0.84,1.01) | .03 | 0.92 (0.84,1.00) | .013 |

| Age | |||||||

| 0-<6 months | 1.74 (1425) | 1.65 (604) | 0.95 | 0.95 (0.83,1.09) | .38 | ||

| 6-<12 months | 1.11 (914) | 1.01 (370) | 0.91 | 0.91 (0.77,1.08) | .17 | ||

| 12-<24 months | 0.93 (767) | 0.81 (296) | 0.87 | 0.87 (0.72,1.05) | .06 | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 1.68 (1377) | 1.49 (544) | 0.89 | 0.89 (0.78,1.02) | .03 | ||

| Male | 2.11 (1729) | 1.99 (726) | 0.94 | 0.95 (0.84,1.07) | .22 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 0.48 (392) | 0.49 (180) | 1.02 | 1.03 (0.75,1.43) | .79 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Additional Racial Groups | 0.42 (348) | 0.41 (148) | 0.98 | 0.96 (0.67,1.36) | .75 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.21 (992) | 1.06 (388) | 0.88 | 0.88 (0.71,1.09) | .13 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.67 (1374) | 1.52 (554) | 0.91 | 0.91 (0.76,1.09) | .17 | ||

| Primary Payer | |||||||

| Private | 0.95 (777) | 0.92 (334) | 0.97 | 0.97 (0.78,1.20) | .70 | ||

| Public | 2.69 (2212) | 2.46 (897) | 0.91 | 0.91 (0.80,1.04) | .07 | ||

| Self-pay | 0.14 (117) | 0.11 (39) | 0.79 | 0.75 (0.41,1.39) | .23 | ||

| Site | |||||||

| A | 1.08 (883) | 0.94 (342) | 0.87 | 0.87 (0.73,1.05) | .05 | ||

| B | 0.56 (459) | 0.51 (187) | 0.91 | 0.92 (0.72,1.18) | .37 | ||

| C | 0.46 (378) | 0.36 (130) | 0.78 | 0.77 (0.58,1.04) | .02 | ||

| D | 0.53 (435) | 0.48 (174) | 0.91 | 0.90 (0.70,1.16) | .29 | ||

| E | 0.39 (318) | 0.37 (134) | 0.95 | 0.95 (0.71,1.27) | .65 | ||

| F | 0.31 (251) | 0.30 (111) | 0.97 | 1.00 (0.72,1.38) | .97 | ||

| G | 0.23 (189) | 0.27 (97) | 1.17 | 1.16 (0.81,1.65) | .30 | ||

| H | 0.16 (133) | 0.15 (55) | 0.94 | 0.93 (0.59,1.47) | .69 | ||

| I | 0.07 (60) | 0.11 (40) | 1.57 | 1.50 (0.84,2.69) | .07 | ||

| ISS | |||||||

| 0–8 | 2.85 (2336) | 2.55 (932) | 0.89 | 0.90 (0.81,1.00) | .0103 | 0.90 (0.81,0.99) | .006 |

| 9–15 | 0.88 (720) | 0.87 (317) | 0.99 | 0.99 (0.82,1.20) | .90 | 0.99 (0.83,1.18) | .90 |

| 16+ | 0.06 (50) | 0.06 (21) | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.46,1.94) | .84 | 0.95 (0.48,1.85) | .83 |

| MAIS | |||||||

| 0–2 | 2.86 (2352) | 2.58 (940) | 0.90 | 0.90 (0.81,1.00) | .012 | 0.90 (0.81,0.99) | .006 |

| 3–6 | 0.92 (754) | 0.90 (330) | 0.98 | 0.99 (0.82,1.19) | .84 | 0.99 (0.83,1.17) | .82 |

| Triage Category | |||||||

| ESI1 | 0.22 (182) | 0.16 (60) | 0.73 | 0.74 (0.44,1.25) | .14 | 0.74 (0.51,1.09) | .05 |

| ESI2 | 1.26 (1034) | 1.19 (436) | 0.94 | 0.95 (0.78,1.16) | .50 | 0.95 (0.82,1.10) | .36 |

| ESI3 | 1.89 (1553) | 1.77 (647) | 0.94 | 0.94 (0.80,1.10) | .31 | 0.94 (0.83,1.06) | .17 |

| ESI4 | 0.36 (292) | 0.30 (109) | 0.83 | 0.84 (0.57,1.24) | .25 | 0.84 (0.63,1.12) | .12 |

| ESI5 | 0.04 (30) | 0.01 (5) | 0.25 | 0.38 (0.07,2.01) | .13 | 0.38 (0.11,1.30) | .04 |

| ED Disposition 3 | |||||||

| Admitted/Transferred/Died | 1.43 (1177) | 1.30 (476) | 0.91 | 0.91 (0.78,1.07) | .14 | 0.91 (0.79,1.05) | .09 |

| Discharged | 2.03 (1667) | 1.86 (679) | 0.92 | 0.92 (0.80,1.05) | .11 | 0.92 (0.82,1.03) | .06 |

| Death 3 | |||||||

| No | 3.42 (2810) | 3.10 (1132) | 0.91 | 0.91 (0.83,1.00) | .009 | 0.91 (0.83,1.00) | .007 |

| Yes | 0.05 (45) | 0.07 (27) | 1.40 | 1.35 (0.71,2.59) | .23 | 1.35 (0.72,2.53) | .21 |

Partially adjusted estimates come from separate multivariable Poisson regression models for each characteristic, each with the following covariates: pandemic time period, site, calendar month, and an interaction between pandemic time period and the characteristic. Estimates and confidence intervals represent the contrast within each characteristic (e.g. Hispanic ethnicity) of rates during the pandemic period compared to the pre-pandemic period.

Fully adjusted estimates come from separate multivariable Poisson regression models for each severity indicator, each with the following covariates: pandemic time period, age, sex, race/ethnicity, primary payer, site, calendar month and interactions between pandemic time period and severity. The overall estimate is reported from the multivariable ISS model.

All visits from Site F were excluded from ED disposition and death models due to incomplete disposition data.

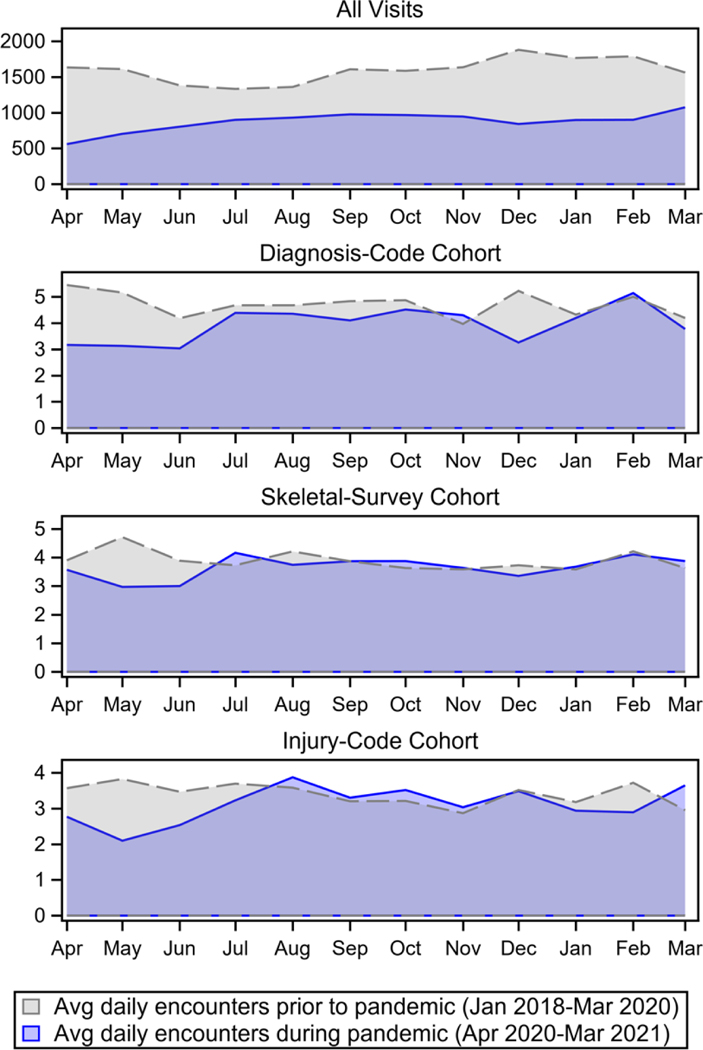

For all methods of identifying suspected child abuse, the magnitude of reduction for abuse encounter rates was smaller than the decrease in total encounters with most marked reduction in abuse encounter rates during first months of pandemic (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Average daily encounters per month in pre-pandemic (Jan 2018-March 2020) and pandemic (April 2020 – March 2021) periods. Averages represent non-adjusted total counts across institutions.

Primary Outcome: Encounter Rates by Clinical severity

In the diagnosis-code cohort, low severity presentations by ISS (0–8) were reduced in partially adjusted analysis (RR 0.80 [0.72, 0.90], p<0.001) while higher ISS category presentations did not change significantly (ISS 9–15: p=0.42, ISS 16+: p=0.93, Table 1). After full adjustment including interaction with ISS, reduction in low severity ISS presentation was 20% (ISS 0–8; ARR 0.80 [0.73, 0.87], p<0.001). Other independently modelled clinical severity measures showed similar reductions in low severity encounters in diagnosis-code cohort including MAIS (0–2, ARR 0.80 [0.73, 0.88], p<0.001), ED discharges (ARR 0.78 [0.70, 0.87], p<0.001), and hospital survival (ARR 0.80 [0.74, 0.88], p<0.001). As with ISS, there were no significant changes in the rate for encounters with higher severity for each measure (Table 1).

Patterns for clinical severity were consistent in diagnosis-code cohort, injury-code, and skeletal-survey cohorts. After full adjustment, reductions in low severity presentations by ISS were significant for both injury-code cohort (ARR 0.85 [0.75,0.96], p<0.001; Table 2) and skeletal-survey cohort (ARR 0.90 [0.81, 0.99], p=0.006; Table 3) while there were no detected changes in daily encounter rates with higher ISS scores. A similar reduction in low severity encounters was observed when modeling low MAIS (injury-code cohort: ARR 0.85 [0.75, 0.96], p<0.001; skeletal-survey cohort: ARR 0.90 [0.81, 0.99], p=0.006) and hospital survival (injury-code cohort: ARR 0.89 [0.80, 0.98], p=0.002; skeletal-survey cohort: ARR 0.91 [0.83, 1.0], p=0.007) without changes in higher severity encounter rates. ED discharges also decreased during the pandemic period in the injury-code cohort (ARR 0.86 [0.75, 0.99], p=0.005); there was no detected change ED discharges when identified by skeletal survey. There were no changes in encounters with severe disposition (ie admitted/transferred/died) for either injury-code or skeletal-survey code cohorts.

Discussion

Our results show that pediatric ED encounters concerning for child physical abuse by ICD-10-CM codes decreased by 19% during the pandemic when assessed across all ages within a multicenter pediatric ED data registry. Rates of encounters among children less than 2 years old with high-risk injuries were reduced by 10% while children with a potential concern for abuse as indicated by skeletal survey completion did not have a significant reduction. The decrease in high-risk injury identification, but not in rates of skeletal survey, implies that decreases were not due to decreased likelihood of clinicians to evaluate or identify abuse. Additionally, our data supports our hypothesis regarding clinical severity and presentation to medical care: encounter rates with lower clinical severity decreased during the pandemic while encounter rates with higher clinical severity were unchanged. This was largely consistent across identification methods and measures of severity.

While reduced or stable emergency healthcare encounters related to child physical abuse may be reassuring, critical assessment is required to further understand and contextualize these results. With regard to reduced low-severity clinical encounters without change in high-severity clinical encounters, these results can be interpreted in at least two ways. First, if reduction in low-severity clinical encounters is driven by decreased recognition while high-severity encounters continue to present for care due to medical need, our results would suggest that actual population rate of abuse may not have decreased during the pandemic. Moreover, if any proportion of severe cases were undetected within medical care related to pandemic shifts, these results may suggest that overall abuse increased. A second interpretation is that reduction in encounter rates represent a true decrease in the population rate of child physical abuse. A true decrease could result from novel protective factors within the pandemic such as having more caregivers at home, for instance older children engaged in virtual schooling or parents who became unemployed or remained home related to social-distancing.28 To explain the specific reduction within the lower severity cases of abuse, presence of additional caregivers would have to reduce children’s risk of less severe physical abuse while failing to impact higher severity occurrences. Our results are unable to distinguish between these interpretations, and further delineation will require additional, multimodal data. These findings add information to previous studies which did not find differences in severity of child abuse by several markers in the medical record.27,28 Our results may be related to using more sensitive assessments of clinical severity.

Second, these results suggest that children experienced different risks during the COVID-19 pandemic related to their age. Children less than two years had a smaller reduction in rate of emergency care for concerns for physical abuse. Specifically, the significant reductions in the diagnosis-code cohort were concentrated among preschool (2-<6 years; 30% reduction) and school-aged (6-<13 years; 20% reduction) children while the reduction among youngest children (<6 months) was only 5 to 10% across identification methods. This pattern supports the importance of school encounters for the recognition of child physical abuse, and may be consistent with importance of mandatory reporter or alternative caregiver exposures for detection in preschool-aged children as well.49 Several assessments support that a driving force for decreased reports to CPS was decreased attendance to in-person school.11,30,33 Similarly, decreased in-person healthcare use may contribute to reduced diagnosis of physical abuse.41,50–54 We included race and ethnicity in our models recognizing that these social constructs may associate with differential impact of the pandemic and evaluation patterns for child abuse.40–43 Our findings indicate that there was differential reduction by race and ethnicity within the diagnosis-code cohort but not for other cohorts.

Third, our results show institutional variability. Specifically, in the diagnosis-code cohort, two of nine sites had significant reductions while two other sites showed non-significant trends toward increases. Variability by site is consistent with previous literature that includes multiple single-site reports suggesting increases in child maltreatment and emphasizes the need for contextualization of results by granularity of inquiry.22–26 Local policy and practice such as virtual versus in-person school may influence variability by site.11,30,33 Thus, aggregate assessment across institutions is valuable for trends yet may obscure significant variation evident at higher granularity – providing one potential unifying theory for the existing variability in the literature.

Two assumptions are worth reviewing to contextualize our results. First, the identification of child physical abuse related encounters within EDs assumes this is a relevant way to understand harm experienced by children in retrospective study designs. Diagnosis codes do not represent a reference standard for diagnosis of abuse in isolation yet are frequently used to measure population trends, and, while skeletal surveys are predominantly performed in EDs related to physical abuse evaluation, other medical indications are possible.55,56 Thus, differences across three encounter identification methods may be reflective of variable sensitivity and specificity. For example, using ICD-10-CM child abuse codes seems the most restrictive by number of encounters identified. This is consistent with previous studies that have suggested low sensitivity for healthcare-assigned child abuse diagnosis codes and reiterates the importance of complementary encounter identification schema.38,57 Second, comparison of pre-pandemic to pandemic periods relies upon the assumption that hospital catchment with regard to child physical abuse evaluation and diagnosis was not specifically impacted by COVID-19 pandemic. For example, this includes the assumption that transfer patterns to participating institutions was not impacted by pandemic-related behavior changes.

Our findings are also subject to at least two limitations. First, this analysis focused on physical abuse and does not provide insight into neglect, sexual abuse, or other forms of child maltreatment though it is likely that some cases of sexual abuse were included in general abuse diagnosis codes (e.g., “child maltreatment” [T76.92XA]). Second, the collection of patients and hospitals within the PECARN Registry may not be representative of the community or other care settings. Results require replication and expansion in other datasets to clarify generalizability.

In conclusion, our results suggest pediatric emergency medical encounters related to physical abuse were reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to previous years. Further, these reductions were driven by decreases in lower severity encounters and among preschool and school age children. While a reduction could be reassuring, there was no evidence of reduction in the rates of higher severity injuries. This pattern calls for further critical assessment to clarify the role of decreased recognition and associated potential for unrecognized harm experienced by children during the COVID-19 pandemic versus true reduction related to novel protective factors.21

What’s Known on This Subject:

The SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19) pandemic prompted safety concerns for children given multiple societal stressors with simultaneous disruption of normal routines yet literature has been mixed with regard to changes in child maltreatment, including healthcare use related to physical child abuse.

What This Study Adds

In this multicenter assessment of emergency healthcare related to child physical abuse, encounter rates decreased inconsistently, with focused declines in low severity and older age group encounters. This pattern raises concern for unrecognized harm versus true reductions.

Acknowledgements:

Members of the PECARN Registry Study Group and PECARN Child Abuse Special Interest Group include:

Kathleen M. Adelgais, MD MPH, Section of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO

Lynn Babcock, MD, MS, Department of Pediatrics, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH

James M. Chamberlain, MD, Children’s National Hospital, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington D.C.

Susan Duffy, MD, MPH, Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Departments of Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics, Hasbro Children’s Hospital, Warren Alpert Medical School of Medicine at Brown University, Providence, RI

Robert W. Grundmeier, MD, Division of General Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Perelman School of Medicine, and the Center for Center for Pediatric Clinical Effectiveness, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA

Sadiqa Kendi, MD, Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Boston Medical Center, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA

E. Brooke Lerner, PhD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY

Julia N. Magana, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of California Davis Health, University of California Davis School of Medicine, Sacramento, CA

Prashant Mahajan, MD, MPH, MBA, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

Stephanie M. Ruest, MD, MPH, Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Departments of Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics, Hasbro Children’s Hospital, Warren Alpert Medical School of Medicine at Brown University, Providence, RI

Bashar S. Shihabuddin, MD, MS, Section of Emergency Medicine, Division of Pediatrics, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH

Norma-Jean E Simon, MPH, MPA, Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL

Asha Tharayil, MD, Division of Pediatrics, Emergency Medicine, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas

Danny G. Thomas, MD, MPH, Section of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI

Joseph J. Zorc, MD, MSCE, Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA

Additionally, we wish to acknowledge Cara Elsholz, BS, and Cody Olsen, MS, for their contributions to project planning and organization.

Funding Sources:

This project work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) grant R01HS020270. Salary support was provided by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health (NIH/NIMH) institutional training grant (T32 MH019112) (Dr Chaiyachati).

PECARN is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA, U03 MC33155) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), in the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB), under the Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) program through the following cooperative agreements: DCC-University of Utah, GLEMSCRN-Nationwide Children’s Hospital, HOMERUN-Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, PEMNEWS-Columbia University Medical Center, PRIME-University of California at Davis Medical Center, CHaMP node- State University of New York at Buffalo, WPEMR- Seattle Children’s Hospital, and SPARC- Rhode Island Hospital/Hasbro Children’s Hospital.

This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

A complete list of study group authors appears in the Acknowledgments.

Abbreviations:

- ARR

adjusted rate ratio

- CI

confidence intervals

- COVID-19

SARS-CoV2

- CPS

child protective services

- ED

emergency department

- ESI

emergency severity index

- HER

electronic medical health record

- ICD-10-CM

International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision Clinical Modification

- ISS

Injury Severity Scale

- MAIS

Maximum Abbreviated Injury Score

- PECARN

Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network

- RR

rate ratio

Appendix

eTable 1.

ICD10-CM Codes for suspected and confirmed child physical abuse

| Unspecified child maltreatment, confirmed | T7492XA |

| Unspecified child maltreatment, suspected | T7692XA |

| Child physical abuse, confirmed | T7412XA |

| Child physical abuse, suspected | T7612XA |

| Shaken infant syndrome | T744XXA |

eTable 2.

High-Risk Injury ICD-10 CM codes for child physical abuse

| Injury Category# | Age at Risk, months | ICD-10-CM Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Bruising/Contusion | <6 | S0003, S001, S0020, S0033, S0040, S0043, S0050, S0053, S0080, S0083, S0093, S2030, S051, S100, S200, S202, S300–303, S309, S400, S500-S502, S600-S602, S700-S701, S800-S801, S900-S903, S1080, S1083, S2010, S2030, S2040, S309, S4091-S4092, S5090–5091, S6039, S609, S709, S809, S909 |

| Oropharyngeal injury | <6 | S015, S025, S0050, S0051, S0053, S0057 |

| Femur/humerus fracture/dislocation* | <12 | S422-S424, S72 |

| Radius/ulna/tibia/fibula fracture/dislocation* | <12 | S52, S821-S829 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | <12 | S061-S068 |

| Rib fracture(s)* | <24 | S223-S225 |

| Abdominal trauma | <24 | S35-S37, S381, S383, S3981, S3991 |

| Genital injury | <24 | S302, S303, S312-S315, S380, S382, S30812-S30817, S30872-S30877, S3093-S3098 |

| Subconjunctival hemorrhage | <24 | H113 |

Non-exclusive categories as codes were included in each relevant category (eg oropharyngeal bruise included as both Bruising/Contusion and Oropharyngeal injury)

Fracture codes ending in A, B, C except S422–424 and S223-S225 which are only A,B

eTable 3.

Exclusion Codes

| Category | Description | ICD10-CM Code |

|---|---|---|

| Repeat visit | Any other than initial visit | 7th Character D, S |

| Vehicular accident | Child whose injures were sustained from MVA or automotive accident of some sort (included planes, boats, spaceships etc.) | V00-V99 |

| Birth injuries | Injuries related to birth | P10-P15, P52, P545, Z38 |

| Metabolic bone diseases | Including rickets, Vitamin D deficiency, and OI | E550, E643, M839, N250, Q780, E8330-E8339 |

| Bleeding disorders | Inclusive of specified and unspecified coagulation disorders | D66, D67, D68, D69, P53, P60, P610, P616 |

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure:

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest:

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia has received payment for the expert testimony of Drs. Chaiyachati and Wood when subpoenaed for cases of suspected abuse.

References

- 1.Sidebotham P, Golding J, The ALSPAC Study Team, Children. Child maltreatment in the “children of the nineties” a longitudinal study of parental risk factors. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25(9):1177–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubowitz H, Kim J, Black MM, Weisbart C, Semiatin J, Magder LS. Identifying children at high risk for a child maltreatment report. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35(2):96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger RP, Fromkin JB, Stutz H, et al. Abusive head trauma during a time of increased unemployment: a multicenter analysis. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider W, Waldfogel J, Brooks-Gunn J. The Great Recession and risk for child abuse and neglect. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;72:71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang MI, O’Riordan MA, Fitzenrider E, McDavid L, Cohen AR, Robinson S. Increased incidence of nonaccidental head trauma in infants associated with the economic recession. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;8(2):171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood JN, French B, Fromkin J, et al. Association of Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma Rates With Macroeconomic Indicators. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(3):224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keenan HT, Marshall SW, Nocera MA, Runyan DK. Increased incidence of inflicted traumatic brain injury in children after a natural disaster. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(3):189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of Depression Symptoms in US Adults Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Twenge JM, Joiner TE. U.S. Census Bureau-assessed prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(10):954–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silliman Cohen RI, Bosk EA. Vulnerable Youth and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baron EJ, Goldstein EG, Wallace CT. Suffering in silence: How COVID-19 school closures inhibit the reporting of child maltreatment. J Public Econ. 2020;190:104258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphreys KL, Myint MT, Zeanah CH. Increased Risk for Family Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patrick SW, Henkhaus LE, Zickafoose JS, et al. Well-being of Parents and Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawson M, Piel MH, Simon M. Child Maltreatment during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Consequences of Parental Job Loss on Psychological and Physical Abuse Towards Children. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(Pt 2):104709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffith AK. Parental Burnout and Child Maltreatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Fam Violence. 2020:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas EY, Anurudran A, Robb K, Burke TF. Spotlight on child abuse and neglect response in the time of COVID-19. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(7):e371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fry-Bowers EK. Children are at Risk from COVID-19. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020;53:A10–A12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cappa C, Jijon I. COVID-19 and violence against children: A review of early studies. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;116(Pt 2):105053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marmor A, Cohen N, Katz C. Child Maltreatment During COVID-19: Key Conclusions and Future Directions Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2021:15248380211043818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapp A, Fall G, Radomsky AC, Santarossa S. Child Maltreatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Rapid Review. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2021;68(5):991–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sege R, Stephens A. Child Physical Abuse Did Not Increase During the Pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sidpra J, Abomeli D, Hameed B, Baker J, Mankad K. Rise in the incidence of abusive head trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106(3):e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovler ML, Ziegfeld S, Ryan LM, et al. Increased proportion of physical child abuse injuries at a level I pediatric trauma center during the Covid-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020:104756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma S, Wong D, Schomberg J, et al. COVID-19: Differences in sentinel injury and child abuse reporting during a pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;116(Pt 2):104990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salt E, Wiggins AT, Cooper GL, et al. A comparison of child abuse and neglect encounters before and after school closings due to SARS-Cov-2. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;118:105132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bullinger LR, Boy A, Messner S, Self-Brown S. Pediatric emergency department visits due to child abuse and neglect following COVID-19 public health emergency declaration in the Southeastern United States. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaiser SV, Kornblith AE, Richardson T, et al. Emergency Visits and Hospitalizations for Child Abuse During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maassel NL, Asnes AG, Leventhal JM, Solomon DG. Hospital Admissions for Abusive Head Trauma at Children’s Hospitals During COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swedo E, Idaikkadar N, Leemis R, et al. Trends in U.S. Emergency Department Visits Related to Suspected or Confirmed Child Abuse and Neglect Among Children and Adolescents Aged <18 Years Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic - United States, January 2019-September 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(49):1841–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rapoport E, Reisert H, Schoeman E, Adesman A. Reporting of child maltreatment during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in New York City from March to May 2020. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;116(Pt 2):104719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barboza GE, Schiamberg LB, Pachl L. A spatiotemporal analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on child abuse and neglect in the city of Los Angeles, California. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;116(Pt 2):104740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen LH. Calculating the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on child abuse and neglect in the U.S. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;118:105136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown SM, Orsi R, Chen PCB, Everson CL, Fluke J. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Child Protection System Referrals and Responses in Colorado, USA. Child Maltreat. 2021:10775595211012476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deakyne Davies SJ, Grundmeier RW, Campos DA, et al. The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network Registry: A Multicenter Electronic Health Record Registry of Pediatric Emergency Care. Appl Clin Inform. 2018;9(2):366–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindberg DM, Beaty B, Juarez-Colunga E, Wood JN, Runyan DK. Testing for Abuse in Children With Sentinel Injuries. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christian CW, Committee on Child A, Neglect AAoP. The evaluation of suspected child physical abuse. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):e1337–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puls HT, Anderst JD, Davidson A, Hall M. Trends in the Use of Administrative Codes for Physical Abuse Hospitalizations. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hooft A, Asnes AG, Livingston N, et al. The Accuracy of ICD Codes: Identifying Physical Abuse in 4 Children’s Hospitals. Academic Pediatrics. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stavas N, Paine C, Song L, Shults J, Wood J. Impact of Child Abuse Clinical Pathways on Skeletal Survey Performance in High-Risk Infants. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(1):39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossen LM, Branum AM, Ahmad FB, Sutton P, Anderson RN. Excess deaths associated with COVID-19, by age and race and ethnicity—United States, January 26–October 3, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(42):1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaiyachati BH, Agawu A, Zorc JJ, Balamuth F. Trends in Pediatric Emergency Department Utilization after Institution of Coronavirus Disease-19 Mandatory Social Distancing. J Pediatr. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lane WG, Rubin DM, Monteith R, Christian CW. Racial differences in the evaluation of pediatric fractures for physical abuse. JAMA. 2002;288(13):1603–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jenny C, Hymel KP, Ritzen A, Reinert SE, Hay TC. Analysis of missed cases of abusive head trauma. JAMA. 1999;281(7):621–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilboy N, Tanabe P, Travers D, Rosenau AM. Emergency Severity Index (ESI): a triage tool for emergency department care, version 4. Implementation handbook. 2012;2012:12–0014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W Jr., Long WB. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;14(3):187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glerum KM, Zonfrillo MR. Validation of an ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM map to AIS 2005 Update 2008. Inj Prev. 2019;25(2):90–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine (AAAM). The Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) 2005 - Update 2008. Barrington, IL: AAAM;2008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zonfrillo MR, Macy ML, Cook LJ, et al. Anticipated resource utilization for injury versus non-injury pediatric visits to emergency departments. Inj Epidemiol. 2016;3(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puls HT, Hall M, Frazier T, Schultz K, Anderst JD. Association of routine school closures with child maltreatment reporting and substantiation in the United States; 2010–2017. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;120:105257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits—United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2020;69(23):699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santoli JM. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on routine pediatric vaccine ordering and administration—United States, 2020. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2020; 69(19);591–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dean P, Zhang Y, Frey M, et al. The impact of public health interventions on critical illness in the pediatric emergency department during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DeLaroche AM, Rodean J, Aronson PL, et al. Pediatric Emergency Department Visits at US Children’s Hospitals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics. 2021;147(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Even L, Lipshaw MJ, Wilson PM, Dean P, Kerrey BT, Vukovic AA. Pediatric emergency department volumes and throughput during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:739–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Helton JJ, Carbone JT, Vaughn MG, Cross TP. Emergency Department Admissions for Child Sexual Abuse in the United States From 2010 to 2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(1):89–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.King AJ, Farst KJ, Jaeger MW, Onukwube JI, Robbins JM. Maltreatment-Related Emergency Department Visits Among Children 0 to 3 Years Old in the United States. Child Maltreat. 2015;20(3):151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rovi S, Johnson M. Physician use of diagnostic codes for child and adult abuse. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association (1972). 1999;54(4):211–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]