Abstract

Humans have lived in tenuous battle with malaria over millennia. Today, while much of the world is free of the disease, areas of South America, Asia, and Africa still wage this war with substantial impacts on their social and economic development. The threat of widespread resistance to all currently available antimalarial therapies continues to raise concern. Therefore, it is imperative that novel antimalarial chemotypes be developed to populate the pipeline going forward. Phenotypic screening has been responsible for the majority of the new chemotypes emerging in the past few decades. However, this can result in limited information on the molecular target of these compounds which may serve as an unknown variable complicating their progression into clinical development. Target identification and validation is a process that incorporates techniques from a range of different disciplines. Chemical biology and more specifically chemo‐proteomics have been heavily utilized for this purpose. This review provides an in‐depth summary of the application of chemo‐proteomics in antimalarial development. Here we focus particularly on the methodology, practicalities, merits, and limitations of designing these experiments. Together this provides learnings on the future use of chemo‐proteomics in antimalarial development.

Keywords: antimalarial, chemical probe, malaria, target engagement, target identification

Abbreviations

- ABPP

activity‐based protein profiling

- ACT

artemisinin combination therapy

- AfBPP

affinity‐based protein profiling

- ALDH1

aldehyde dehydrogenase family 1

- ALLN

N‐acetyl‐Leu‐Leu‐Norleu‐al

- ART

artemisinin

- ATC

aspartate transcarbamoylase

- AzT

TAMRA azide

- AzTB

TAMRA biotin azide

- CDK2

cyclin dependent kinase

- CEPT

choline/ethanolamine phosphotransferase

- CETSA

cellular thermal shift assay

- CK1

casein kinase

- CnBr

cyanate ester

- CQ

chloroquine

- crapOME

contaminant repository for affinity purification

- CSP

circumsporozoite protein

- CuAAC

copper‐catalyzed azide‐alkyne cycloaddition

- DARTS

drug‐affinity responsive target stability

- DFO

desferrioxamine

- DFP

deferiprone

- DHODH

dihydroorotate dehydrogenase

- DV

digestive vacuole

- emPAI

exponentially modified protein abundance index

- HA

hemagglutinin A

- HDP

hemoglobin derived products

- HEA

hydroxyethyl amine

- HKMT

histone lysine methyltransferases

- HQ

hydroxychloroquine

- ICAT

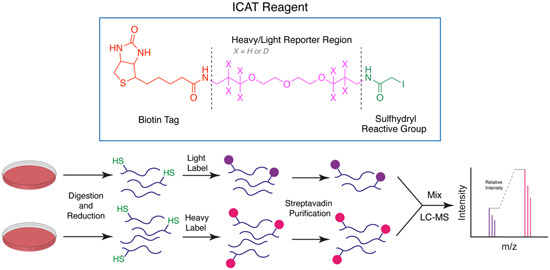

isotope‐coded affinity tagging

- IEDDA

inverse‐electron demand Diels–Alder

- ITDR

isothermal drug response

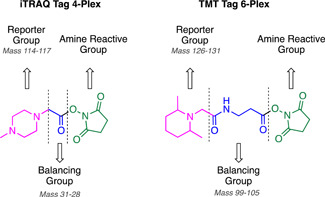

- Itraq

isobaric tagging for relative and absolute quantification

- IVE‐GWAS

in vitro evolution—genome wide association studies

- LC/MS/MS

liquid chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry

- MFQ

mefloquine

- MS

mass spectrometry

- Myr‐CoA

Myristoyl‐Coenzyme A

- NHS

N‐hydroxysuccinamide

- NMT

N‐myristoyltransferase

- PAL

photoaffinity labeling

- PfATC

Plasmodium falciparum aspartate transcarbamoylase

- PfCDPK1

Plasmodium falciparum calcium‐dependent protein kinase

- PfDHFR‐TS

Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase‐thymidylate synthase

- PfENT4

Plasmodium falciparum Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter

- PfMDR1

Plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance protein

- PfOAT

Plasmodium falciparum ornithine aminotransferase

- PfPNP

Plasmodium falciparum purine nucleoside phosphorylase

- PfPyKII

Plasmodium falciparum pyruvate kinase II

- PfSPP

Plasmodium falciparum Signal Peptide Peptidase

- PI4K

phosphatidylinositol 4‐kinase

- PKG

cGMP‐dependent kinase

- PM

plasmepsin

- PMIX

plasmepsin IX

- PMX

plasmepsin X

- PQ

primaquine

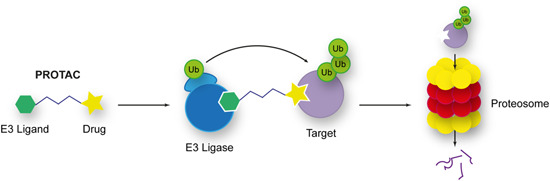

- PROTACs

proteolysis‐targeting chimeras

- QR2

quinine oxidoreductase 2

- RBC

red blood cell

- RING

really interesting new gene

- Sal A

Salinipostin A

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- SILAC

stable isotope labeling with amino acids in culture

- SPAAC

strain‐promoted azide‐alkyne cycloaddition

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- SPROX

stability of proteins from rates of oxidation

- TER

tetraethylrhodamine

- TMT

tandem mass tagging

1. INTRODUCTION

Malaria is a parasitic protozoan disease that causes a huge burden on human well‐being worldwide. 1 Over 200 million people are infected with the disease annually, resulting in approximately 619,000 deaths in 2021. 2 Restricted primarily to tropical regions, malaria is caused by the transmission of Plasmodium parasites by the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito. While a number of Plasmodium species have the potential to cause human disease, P. falciparum and P. vivax have the most significant impact on mortality and morbidity. 2 The management of malaria consists of mosquito intervention methods and antimalarial chemotherapy which collectively, have resulted in a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality over the past 20 years. 3 Unfortunately, resistance to most currently available antimalarials has been observed in P. falciparum, including the front‐line Artemisinin Combination Therapies (ACTs). 4 As such, some drug classes used to treat the disease are no longer recommended for clinical use. 5 , 6 To curb the onset of resistance, world health authorities have prescribed that new antimalarials have a novel chemotype and target a mechanism of action not previously reported. 7 More recently, a pioneering RTS,S/AS01 vaccine based on the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) has been approved for use in children in areas of high transmission. 2 However, the efficacy of the vaccine is just 36% over 4 years of monitoring. 8 Therefore, antimalarial chemotherapies will remain at the forefront of disease treatment and control.

To discover new antimalarial chemotypes, there has been an explosion in mass phenotypic high throughput screening of large compound libraries in the past 20 years. 9 , 10 , 11 These screens have been primarily performed on the asexual erythrocytic stage of P. falciparum as this form of the parasite is the most tractable in the laboratory, 12 although more recently, assays and platforms become available to screen both the sexual (both gametocyte and gamete) 13 and liver sporozoite and schizont stages of the P. falciparum lifecycle. 14 , 15 Additionally, methods have been established to screen against the latent P. vivax hypnozoite. 16 , 17 The mass phenotypic screening effort has resulted in the identification of starting points that have led to the development of several clinical candidates, such as cipargamin (KAE609), ganaplacide (KAF156), and MMV048, undergoing Phase II trials. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 While phenotypic‐based screening has become the mainstay for the identification of new antimalarial chemotypes, target‐based screening has also uncovered starting points against genetically validated targets, for example, the dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) inhibitor and Phase II clinical candidate DSM265. 22 , 23

Both phenotypic and target‐based drug discovery methods present their own unique challenges. For phenotypic drug discovery, once a hit molecule is identified, a key development task is to deconvolute the mechanism of action. 24 While antimalarials can be developed without a fully described mechanism of action, 25 establishing the target is highly desirable for the following reasons. 26 First, the target can help define the target product profile by understanding the target pharmacology, and secondly, visualizing the compound in complex with a protein target can expedite the development via structural‐based design. For target‐based drug discovery, target engagement within the parasite is important to demonstrate the compound is indeed killing the parasite via the target. Target engagement is also crucial in validating the target of the phenotypic hit once it has been uncovered by target identification methods. Nevertheless, for either target or phenotypic approaches, the process of target identification and engagement is a vital aspect of antimalarial research and development.

The most extensively used approaches toward antimalarial target identification involve omic methods, which have been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere. 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 Briefly, these include genomic, metabolomic, and proteomic methods. Genomic methods in target deconvolution involve in vitro evolution of resistance to the compound of interest followed by genome‐wide association studies (IVE‐GWAS) or nucleotide expression profiling with microarray followed by compound treatment. 33 IVE‐GWAS relies on culturing resistance to the compound of interest, which may not be possible if the compound elicits its pharmacological response via inhibition of multiple protein targets, pathways that are not genome‐encoded or host‐derived proteins. Metabolomics is another popular target deconvolution method whereby alterations to the parasite metabolome are detected following drug treatment, identifying pathways that are indirectly inhibited. 34 , 35 Generally, this method provides a top‐down analysis and requires further studies to elucidate the protein target(s). Global transcriptomics and proteomic methods follow a similar rationale with protein and mRNA levels monitored following drug treatment. 36 , 37

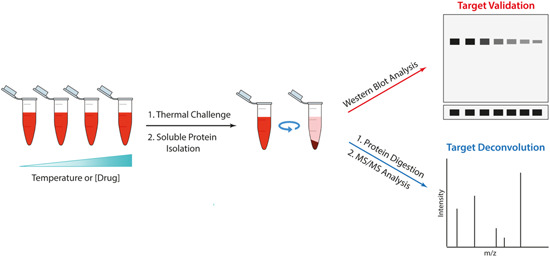

Chemo‐proteomic methods have recently emerged as a useful alternative to directly and unbiasedly detect the protein target(s) of antimalarial compounds discovered from phenotypic screening. Chemo‐proteomic techniques are an example of direct target identification methods in which the effects of compound–target interactions are measured directly, not through downstream events. Examples of such techniques include affinity binding techniques using pulldown probes and thermal stability profiling. Additionally, many of the unbiased chemo‐proteomic methods are adapted to biased methods to demonstrate compound engagement with a parasite protein target to assist with on‐target validation of the antimalarial under development.

This perspective will focus on the application of chemical biology methods in antimalarial target identification and target engagement. This appraisal of the field distinguishes itself from recent overviews 38 , 39 , 40 by providing a detailed description of key examples using chemical biology techniques in antimalarial target identification and target engagement while discussing the advantages and limitations. This review aims to act as a guide for the development and application of chemical biology techniques in antimalarial target deconvolution and more broadly in antimalarial drug development.

2. PARASITE AND HOST‐SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS IN CHEMO‐PROTEOMICS

2.1. A complex lifecycle

A unique aspect of Plasmodium biology is its complex, multi‐host lifecycle. Human infection begins with the injection of infective sporozoites from Anopheles mosquitoes and these parasites make their way to the liver and invade hepatocytes, where they undergo schizogony or form dormant hypnozoites in the case of P. vivax and P. ovale. 41 Liver schizonts release large numbers of merozoites into the bloodstream which invade red blood cells and begin the asexual blood cycle. A portion of these erythrocytic forms diverges into the sexual blood stage, forming gametocytes that can be consumed by the mosquito in a blood meal and develop in this definitive host which completes the cycle. Dramatic changes in parasite morphology and size occur across the different stages, and indeed within these stages. Consequently, the parasite proteome differs widely, as do potential drug targets. 42 The importance of developing drugs that target all of these stages has been clearly underlined therefore efficient phenotypic screening methods and henceforth target identification is essential for drug development. 43 Comparatively, proteomic sample preparation of Plasmodium is arduous and expensive in large quantities. 44 Therefore, a formidable challenge for Plasmodium proteomic research has been the development of robust culturing conditions at significant scale for quality data. 44 In the following Sections 2.1.1, 2.1.2, 2.1.3, 2.1.4, 2.1.5, parasite stage and host‐specific considerations are outlined for application in chemo‐proteomic methods.

2.1.1. Liver stage

One of the most difficult malaria lifecycle stages to study is the liver stage as the cells are not easily maintained for long periods and at scales sufficient for chemoproteomic analysis. To begin, infective sporozoites must be isolated and purified from the salivary glands of female Anopheles' mosquitoes, requiring specialized insectary facilities. 45 Additionally, the numbers of liver cells invaded by sporozoites is small and some species exhibit cell‐specific invasion. The rodent species P. berghei has been widely used to study the liver stages due to its ability to be cultured in human lung, 46 human hepatoma, 47 HeLa, 48 and mouse hepatocyte cell lines. 49 Culture of human infective species such as P. falciparum, P. vivax, and P. ovale has been achieved in primary liver hepatocytes, however, these host cells cannot be kept in continuous culture. 50 , 51 , 52 The human hepatoma cancer cell HepG2‐A16 was subsequently used as a method to culture liver stage P. vivax, but cannot support the development of P. falciparum. 53 , 54 More recently, the HC‐04 hepatocyte line has been developed to culture both P. falciparum and P. vivax liver stages. 55 , 56 To study the dormant liver stages produced by P. vivax and P. ovale, the specialized hepatocyte line imHC is used as HC‐04 hepatocytes proliferate unrestrictedly and detach from the culture dish, limiting their use for long‐term hypnozoites. 57 The lack of chemo‐proteomic studies on liver stage parasites reflects experimental challenges, for example, difficult culturing conditions and target deconvolution in the presence of abundant host cell proteins. More sensitive methods, therefore, need to be developed to study target identification/engagement in this stage. However, chemo‐proteomic experiments looking at parasite effector proteins in the host hepatocyte may be possible.

2.1.2. Asexual blood stage

The P. falciparum and P. knowlesi erythrocytic stages are the most easily maintained stage in vitro with the development of robust culturing conditions that enable continuous culture. 58 , 59 However, standard static cultures cannot be routinely kept above 10% parasitemia, therefore, considerable scale is required for large proteomic experiments. 60 In contrast, no continuous culturing conditions exist for P. vivax parasites and samples must be derived directly from human infections, further complicating the species’ chemo‐proteomic study. 61 Consequently, the majority of the chemo‐proteomic research has been performed on the P. falciparum asexual blood stages.

Continuous in vitro cultures of Plasmodium are characteristically asynchronous in their lifecycle. 58 Protein expression can be highly stage‐specific and is fundamentally linked with stage‐specific activity observed in most antimalarial compounds. Once the stage of arrest is established, the specificity of proteomic data is enhanced with samples generated from synchronized parasites obtained through a range of methods. Sorbitol ring synchronization leads to purified ring stage cultures via stage‐specific permeability pathways. 62 Mid‐trophozoite, schizonts, and gametocytes, on the other hand, can be purified using a magnetic resin that attracts the iron‐containing hemozoin complexes resulting from hemoglobin digestion in the parasite. 63 Finally, centrifugation‐based purifications such as Percoll gradients can also be used to separate these stages according to their relative density. 64

2.1.3. Transmission stages

Gametocyte culturing conditions are analogous to the asexual erythrocytic stage and therefore can also be suitable for proteomic research. 13 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 Until recently, several issues have made their production at scale more difficult. The small numbers of asexual parasites that commit to this pathway (~5%) and the progressive loss of a culture's ability to produce gametocytes have been a bottleneck to production. 70 , 71 However, a recently reported CRISPR/Cas9‐engineered gametocyte producer line enables high sexual commitment rates (75%) for larger scale production. 72 The inducible overexpression of the sexual commitment factor GDV1 greatly improves the control and yield of sexual forms for use in transmission research. 72 Methods to separate early (I–III) and late (IV and V) gametocytes have been established. 13 , 69 Therefore, as with the other stages of the lifecycle, phenotyping, and establishment of early versus late‐stage gametocyte activity should be aligned with an effective proteomic study.

In vitro methods to culture and purify the remainder of the transmission stages that occur in the mosquito have been developed but at small scales. Exflagellation, or the formation of gametes from gametocytes, can be achieved through parasite resuspension in fetal bovine serum at pH 8. 73 In vitro and ex vivo culturing of ookinetes is most common in P. berghei. 74 , 75 This is because the efficiency of conversion of P. falciparum parasites to mature ookinetes in vitro is very low compared to in vivo. 76 , 77 Maturation from ookinete to oocyst requires a complex coculture system with Drosophila cells and Matrigel substrate. 78 Overall, the chemo‐proteomic study of the mosquito stages, particularly in P. falciparum, suffers from challenges in obtaining sufficient material and at the correct stage for a sensitive quantitative study. Improvements in culturing conditions, workup, and instrument sensitivity will aid in future proteomic work.

2.1.4. Sub‐proteomics

In some cases, phenotypic indications such as timing and stage of antimalarial activity can provide clues as to the mechanism of action. For example, antimalarials with a delayed death phenotype (activity >48 h) are known to target the development of apicoplast organelles in daughter parasites. 79 , 80 , 81 If such a hypothesis is known, the resolution and specificity of chemoproteomic results can be improved by obtaining sub‐proteomic extracts from isolated organelles. This has been achieved for the analysis of the food vacuole, 82 micronemes, 83 , 84 and nucleus 85 with differential centrifugation followed by density gradient separation. There are also analogous methods to isolate the mitochondria and apicoplast through nitrogen cavitation followed by density gradient separation, but these have not yet been applied to proteomic research. 86

2.1.5. Human host erythrocytes

As an obligate parasite, a major challenge in Plasmodial proteomic research is the contamination of host proteins. The blood and liver stages are encased in their host cell as well as a parasitophorous vacuole membrane. High abundance erythrocyte proteins, in particular hemoglobin, can mask the low abundance of parasite proteins. 44 To avoid this, erythrocytic parasites can be purified with saponin lysis which selectively disrupts the erythrocyte membrane while leaving both the parasite and parasitophorous membrane. 87 However, this does not fully resolve these issues as the parasites themselves break down hemoglobin and store by‐products such as hemozoin and hemoglobin‐derived products (HDPs) which can also complicate the sensitivity of proteomic studies. 88 Therefore, for the proteomic study of Plasmodium careful consideration of protein extraction conditions should be taken. For example, traditional lysis buffers containing urea, thiourea, and DTT are thought to disrupt the food vacuole and thus release HDP, while freeze‐thaw lysis does not. 88 However, the removal of erythrocyte proteins may not always be desirable and proteomics can be performed on parasitized red blood cells to identify potential human target proteins. For example, it is predicted that around 280 proteins of parasite origin are exported to the host erythrocyte with roles in immune avoidance and host cell remodeling. 89 , 90 , 91 13%–23% of these exported proteins are known to be essential, although no drugs are known to target these proteins as of yet, these could potentially be targets of antimalarials and require target deconvolution studies. 91

3. CHEMICAL PROBES

One of the most widely applied chemical biology reagents in antimalarial target identification is the chemical probe. For the purposes of target identification, a chemical probe is a reagent used to purify or pulldown target proteins from complex mixtures by means of affinity or activity‐based protein profiling (AfBPP or ABPP). AfBPP leverages the intrinsic affinity of a compound of interest, acting like a bait. ABPP uses a slightly revised principle, relying on a reactive warhead that targets specific residues in the target active site. Often this is used to assess enzymatic families that have conserved catalytic residues, such as serine hydrolases, cysteine proteases, aspartyl, and glutamyl glycosidases. 92 Unlike AfBPP, the target protein becomes covalently linked to the reactive warhead of the ABPP chemical probe, and therefore is irreversibly modified.

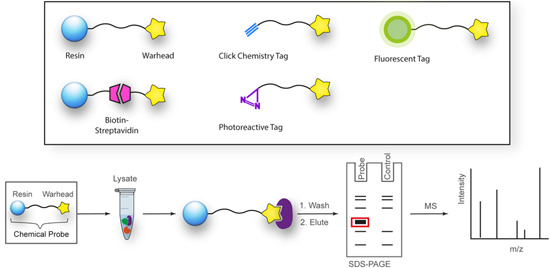

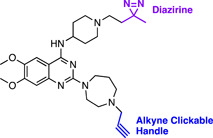

The construction of a chemical probe is achieved by conjugating a target‐interacting warhead via a linker to a solid support or functional tag (Figure 1). The sophistication of the compound conjugation or labeling method has rapidly expanded from simple resin immobilization to employing click chemistry, photo‐crosslinking, and even bioorthogonal chemistry. These methods utilize a specialized set of specific chemical reactions there are highly efficient for the conjugation of small molecules. The positioning of the linker or functional label on the compound structure is key to maintaining the target protein binding affinity or activity. 93 Typically, the correct positioning of the label requires prior knowledge of the structure–activity relationship (SAR) performed by rational design, or if the protein target is known, visualization of the compound in complex with the protein target may guide the appropriate location to append the label. Confirmation of the probe's activity is often desired; however, the addition of large linkers may preclude cellular permeability and therefore this measurement may not be useful. Instead, a lower molecular weight handle can be utilized as a surrogate to ascertain the activity of the probe.

Figure 1.

Structures and workflow of chemical probes used for target deconvolution. A range of chemical probe types can be employed for target elucidation, including resin immobilized probes, biotin‐streptavidin‐linked probes, fluorescent tag‐linked probes, and finally, probes with click chemistry and photoreactive tags. Chemical probes are constructed by linking the drug moiety to a solid support resin. The cellular lysate is applied to the resin to identify binding proteins. Rigorous washing steps reduce the levels of nonspecific, leaving only high‐affinity binders attached to the resin. The proteins are separated by SDS‐PAGE and are characterized either by western blot analysis or mass spectrometry. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Once the pulldown is complete, protein characterization methods differ depending on the level of knowledge of the target. Target validation in parasites typically utilizes a biased approach whereby an antibody to the target or an engineered parasite line expressing the labeled target is used for detection by Western blot. For unbiased approaches, these methods rely extensively on mass spectrometry and quantitative proteomics to identify targets (described in Section 5). 94 Poly‐pharmacology is a common feature of phenotypically discovered drugs, and indeed the most effective antimalarials for combatting drug resistance. 95 An unbiased approach can be used to identify such features, therefore, it is well suited for the identification of antimalarial targets. 95 Similarly, chemical probes have the ability to identify off‐target binding which can have important implications for understanding human toxicity that may be observed. 96 For example, an antimalarial chemical probe has led to a proposal for the toxicity observed with chloroquine (discussed later). 97 Chemical probes are pharmacologically relevant, concentration‐dependent, and can be used with almost any cell type.

A limitation of AfBPPs and ABPPs is the propensity toward detecting false positives. For AfBPP, since many antimalarials (and indeed most other drug‐like compounds) have some degree of hydrophobicity, they are therefore predisposed to nonspecific protein interactions. 98 Furthermore, AfBPPs and ABPPs are typically used at high concentrations that are not physiologically relevant increasing the likelihood of detecting false‐positive proteins. Distinguishing between nonspecific binding and true low‐affinity binders can be difficult, underpinning the importance of high‐affinity probes in addition to careful probe design and inclusion of appropriate vehicle and negative controls. 99 , 100 On the other hand, the reactive warhead on ABPP probes may lead to the modification of nontarget proteins. Due to these challenges, poorly characterized and nonselective probes have marred the reliability of research in this field. 101 A need for emphasis on high‐quality chemical probes prompted the release of minimum standards for chemical probes by the Chemical Probes Portal. 102 Here, it is recommended that probes should have well‐characterized in vitro activity, with a suitably structurally analogous inactive control, profiling of potential off‐target activity, and finally, evidence of cell permeability. 102 Finally, while this method is widely applicable to cell types, it is largely limited to soluble proteins. 103 While membrane proteins on rare occasions are suitable for both AfBPP and ABPP, they first require treatment of cells with an ionic nondenaturing detergent to release them from the surrounding membrane. Optimal solubilization conditions are difficult to predict without prior knowledge of the target or the parasite phenotype upon antimalarial treatment, as discussed in Section 2.

3.1. Affinity and activity based protein profiling

3.1.1. Chemical probe immobilization techniques

Resin immobilization

Resin immobilized chemical probes are the simplest and most classical design. Resins are typically polymeric solid supports such as Sepharose (agarose) functionalized with a suitable reactive group, such as N‐hydroxysuccinamide (NHS) or cyanate ester (CNBr). The warhead is covalently attached via a linker to resin beads in an orientation that allows it access to the active site of target proteins. 104 The workflow (Figure 1) generally involves the incubation of these chemical probes with cellular or tissue extracts, followed by extensive washing to remove nonspecific interactions. For AfBPP, remaining strong binders are eluted from the resin and separated by SDS‐PAGE at which point enriched protein bands can be identified compared to an inactive control probe. Elution conditions can include excess unlabeled drug to further assure the specificity of the binding proteins. ABPP results in irreversible protein binding therefore elution is not possible. Proteins are prepared for proteomics with on‐bead trypsin digestion, or alternatively, chemically, enzymatically, and photolytically cleavable linkers can be used to release the protein from its solid support.

Streptavidin immobilization

The activity of the probe may be impeded by the process of immobilization. To accommodate indirect affinity purification with such molecules, functional tags such as biotin can be used. 105 A high‐affinity interaction between biotin and streptavidin (K d ≈ 10−14 M) enables enrichment and immobilization when the latter is immobilized to an agarose resin. 106 , 107 In some cases, 108 these biotin‐labeled probes are cell permeable and can be developed for use in live cells where the probe is captured following the cellular lysis. 98

Bioorthogonal immobilization

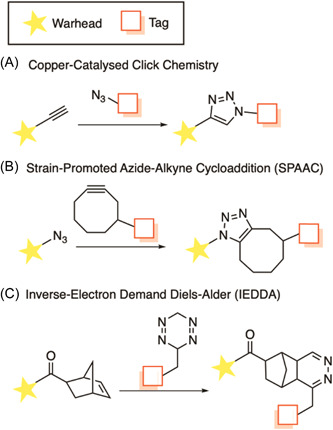

A major advancement in the field of chemical probes is the development of robust bioorthogonal reactions; those that proceed within a cellular context without altering normal biochemistry. 109 These reactions require complete chemoselectivity against a horde of cellular functional groups and must proceed rapidly at low temperatures in aqueous media. 110 Coined by Sharpless et al., 111 “click chemistry” reactions have dominated this space. These reactions “follow nature's lead” and join modular units through highly specific and biocompatible chemical reactions. 111 Common click chemistry reactions include the copper‐catalyzed azide‐alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), strain‐promoted azide‐alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC), and the inverse‐electron demand Diels–Alder (IEDDA) using a strained alkene and tetrazine. 112

The copper‐mediated CuAAC reaction uses terminal azide and alkyne functionalities to form a 1,2,3‐triazole linkage based on the Huisgen Cycloaddition (Figure 2A). However, the use of cytotoxic copper reagents can be undesirable and are therefore not applicable for use in live Plasmodium. 113 Therefore, copper‐free methods have come into prominence for this purpose. The first of these is SPAAC, which uses a strained cyclooctene ring to promote the formation of the triazole linkage (Figure 2B). 114 Other common copper‐free methods also employ facile cycloaddition chemistry, such as IEDDA reactions. An example of this type of reaction employs activated or strained alkenes such as norbornene with a tetrazines functionality (Figure 2C). 115 Bioorthogonal probes are particularly useful where steric restrictions of target binding preclude conjugation to a larger group in situ and lead to a significant reduction in probe activity. 116 A functionalized biotin molecule can be conjugated to the click chemistry partner to enable streptavidin affinity capture. 117 Fluorescent tags can also be conjugated to enable in‐gel fluorescence and live‐cell imaging. 118 Importantly, the same bioorthogonal probe can be used for both experiments, expanding its utility.

Figure 2.

Common bioorthogonal reactions used in the construction of chemical probes. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

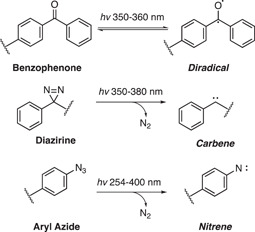

3.2. Photo‐affinity based protein profiling

A major disadvantage of traditional AfBPPs is that their effectiveness is dependent on the activity or affinity of the probe as well as the abundance of the protein target. 100 UV‐mediated covalent photo‐crosslinking or photo‐affinity labeling (PAL) has been developed as a method to circumvent this problem. 119 PAL involves adding a photo‐reactive tag to the probe structure and upon UV irradiation, a reactive radical is generated that allows covalent linkage to proteins in close proximity to the chemical probe—ideally a protein for which the probe has the highest affinity. The photo‐reactive tag consists of groups that can generate reactive diradicals, carbenes, or nitrenes yielded from benzophenones, diazirine, and aryl azide, respectively (Figure 3). 120 To allow for in‐gel fluorescence or affinity capture, often PAL ligands also feature a second functional tag such as a click chemistry handle or a biotin/streptavidin binding partner.

Figure 3.

Common photoaffinity ligands. Benzophenones, diazirines, and aryl azides generate highly reactive species upon excitation with UV light which facilitate photocrosslinking to adjacent proteins when included in a probe structure.

The choice of PAL handle comes with several caveats. Benzophenones have some distinct biochemical advantages in that they are more chemically stable than the other groups and can be handled in ambient light. 121 Additionally, the excitation is reversible in the absence of a suitable C‐H bond to insert into, therefore a sample can be repeatedly excited to improve yields. 122 However, an increase in excitation time can have implications in increasing nonspecific labeling. 123 The size of the benzophenone group can also be difficult to incorporate into the structure without diminishing affinity. 124 Therefore, the comparatively small size of aryl diazirine and aryl azide groups has led to an uptick in their usage. 105 Aryl diazirines produce better photo‐crosslinking yields than aryl azides, perhaps due to the increased reactivity of the carbene over the nitrene. 125 Benzophenones and aryl diazirines are also maximally activated at relatively high wavelengths, causing minimal damage to proteins. 126 However, unlike benzophenones, both aryl diazirines and aryl azides can be susceptible to UV‐induced rearrangement and photolysis which reduces the efficiency of labeling. 127 Nonspecific labeling can be considered a broad problem for all PAL probes as pulldowns are generally performed in great excess. 128 This becomes particularly problematic where target abundance is low, and nonspecific binding obscures its detection. 129 Demonstrating a labeling profile that is specific versus a negative control probe and is disrupted by free compound competition is very important to ensure that specific binding. 129

3.3. Affinity based protein profiling examples

AfBPP has been commonly employed for both target identification and target engagement of antimalarials under development. Reliable pull‐down of the target from parasites is typically reliant on having a highly potent and target‐selective compound as a template for the design of the AfBPP in addition to the appropriate controls to exclude promiscuous and abundant proteins. To provide confidence in the pulled‐down protein are indeed genuine, a bioorthogonal technique should be used to provide supporting evidence. Several AfBPP examples are given below that successfully pulldown the target which is confirmed by a target validation method. These examples include AfBPPs based on MMV048, purvalanol B, purfalcamine, and WM382.

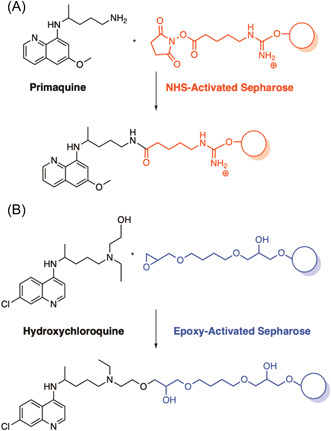

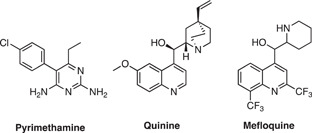

3.3.1. Quinoline antimalarials

The first published use of chemical probes in antimalarial target identification aimed to discover binding or reactive protein targets of quinoline antimalarials. Quinoline antimalarials include hydroxychloroquine (HQ), chloroquine (CQ), primaquine (PQ), and mefloquine (MFQ), 97 which have been in clinical use since the mid‐20th century without a well‐defined mechanism of action. 130 Structural similarity between the quinolines and purine nucleotides led to a hypothesis that they may target purine (ATP) interacting proteins. 97 Therefore, two types of probes were employed, a promiscuous ATP‐Sepharose probe for application in competition experiments as well as quinoline‐Sepharose conjugates. PQ was affixed with its primary amine functionality to NHS‐activated Sepharose (Figure 4A), and HQ with its free hydroxyl group to epoxy‐activated Sepharose (Figure 4B). The ATP‐Sepharose probes were incubated with infected RBC cellular extracts to pull down the RBC and P. falciparum purine proteome. Eluting with PQ, CQ, and MFQ did not result in the identification of any P. falciparum proteins. However, the drugs were highly selective for two human proteins from RBC extracts, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH1) and quinine oxidoreductase 2 (QR2). The same experiments were performed with the PQ and HQ conjugated probes, again selectively eluting only human proteins ALDH1 and QR2. Subsequent in vitro target validation identified potent inhibition of QR2 by CQ and PQ, and only weak inhibition of ALDH1 by CQ. Together, this implicated human QR2 as a probable target of CQ and PQ, whose role is the detoxification of quinones which can cause oxidative damage. 131 The malaria parasite itself is sensitive to oxidative damage, 132 and inhibition of QR2 by quinolines may create an inhospitable environment for parasite growth. While the inhibition of ALDH1 likely does not represent the quinolines' antimalarial target, the authors believe that affinity to ALDH1 may explain chloroquine's reported retinopathy. ALDH1 may have a metabolic role in protecting the eye from UV damage, 133 and treatment with chloroquine indeed results in the hyperaccumulation of retinaldehyde in the retina. 134 , 135 , 136

Figure 4.

Resin immobilized probes of the known antimalarials primaquine and hydroxychloroquine for the identification of cellular targets. Pulldown of the resin immobilized probes in infected erythrocyte lysate resulted in the enrichment of two human proteins, ALDH1 and QR2. Biochemical validation confirmed QR2 as a probable target and indicated that inhibition of ALDH1 may be the result of an off‐target effect. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3.2. MMV048

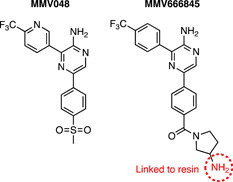

The antimalarial candidate, MMV048 (Figure 5) 137 was developed from a 2‐aminopyridine class identified from a phenotypic high‐throughput screen of the commercial SoftFocus kinase library. 19 As such the exact molecular target of MMV048 was unknown, although presumed to be a kinase. 137 For target deconvolution, a related analog MMV666845 was chosen as it possesses a primary amine functionality (Figure 5). 137 This moiety was covalently immobilized to Sepharose beads by an undisclosed method and was subsequently treated with parasite‐infected RBC lysate. Eluting bound proteins with unlabeled MMV048 identified one high‐affinity binding protein, phosphatidylinositol 4‐kinase (PI4K). 137 Similar to the quinolones, competitive inhibition with unlabeled MMV048 with “kinobeads” derivatized with a broad set of ATP competitive kinase inhibitors that covered approximately 50% coverage of the Plasmodium proteome was also performed, resulting in a dose‐dependent competitive elution of PI4K in the presence of MMV048. 137 In vitro resistance evolution experiments also identified mutations in PI4K validating it as a target. 137 More recently, kinobeads and lipid‐kinobeads with coverage of 54 P. falciparum kinases were used to uncover that sapanisertib had the strongest competition for PKG (PF3D7_1436600), PI4Kβ (PF3D7_0509800), and PI3K (PF3D7_0515300) using P. falciparum lysate. 138 PfPKG and PfPI4Kβ were confirmed as targets of sapanisertib using an ATP competitive biochemical inhibition using recombinant protein, further demonstrating the utility of kinobeads in target identification of antimalarials with kinase‐like chemotypes.

Figure 5.

A resin immobilized chemical probe of MMV048 used in the identification of Plasmodium falciparum cellular targets. An active analog of MMV048 with an amine functionality was chosen to link to the Sepharose resin. Phosphatidylinositol 4‐kinase (PI4K) was identified as a probable target, confirmed with competition experiments with MMV048 and subsequent in vitro resistance evolution. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3.3. Torin 2

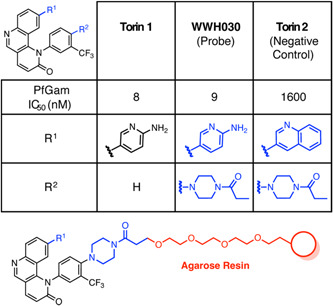

Torin 2 is a known competitive ATP inhibitor of regulatory the kinase mTOR with indications in the treatment of some cancers. 139 In a screen of known chemical entities, it was shown to have potent activity against both gametocytes and asexual P. falciparum. 140 Due to the absence of an mTOR homolog within the P. falciparum genome, target deconvolution was performed using resin immobilized AfBPP. 140 Torin 2 lacks a suitable functional group for attachment to the resin, therefore, the analog WWH030 with a piperazine carboxamide moiety which had minimal impact on gametocytocidal activity was used as the AfBPP (Figure 6A). WWH030 was conjugated to NHS Sepharose, along with a structural similar Torin 1 compound with weak parasite activity which was employed as control AfBPP (Figure 6B). Thirty‐one proteins were specifically pulled down with the Torin 2 chemical probe in gametocyte lysate which was complemented by DARTS target identification (discussed later in Section 3.2), identifying 3 common putative targets: phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase (PF3D7_1325100, ribose‐phosphate diphosphokinase), aspartate transcarbamoylase (PF3D7_1344800, PfATC) and a putative transporter (PF3D7_0914700). 140 PfATC is an enzyme involved with pyrimidine biosynthesis, a pathway targeted directly and indirectly by a number of antimalarials. To validate its role in Torin 2 antimalarial activity, dose–response assays were performed against recombinant PfATC, reported at 68 µM. 141 Transgenic parasites overexpressing ATC were used to validate Torin 2, which revealed a more than 18‐fold reduction in activity compared to the control. 141 The other two putative targets have not been further validated to date. However, Torin 2 analogs have since been developed with greater selectivity for parasites over the human mTor enzyme, improved solubility, and metabolic profile. 142 These analogs have been shown to exert antiparasitic activity through inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 4‐kinase (Pf PI4KIIIβ). 142

Figure 6.

Summary of the human mTOR inhibitor Torin 2 P. falciparum activities and AfBPP design. An equipotent and structurally related compound WWH030 was used to construct a chemical probe for Torin 2 as it possessed a suitable handle. The negative control was constructed from the significantly less active Torin 2. Pulldown in P. falciparum gametocytes revealed putative targets, including phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase, aspartate carbamoyltransferase, ATCase, and (PF3D7_0914700). [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3.4. Purvalanol B

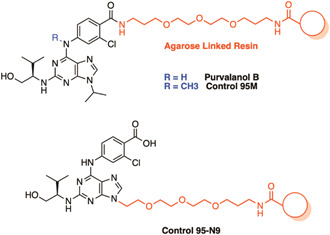

Purvalanol B was identified from a screen of a known human drug library and subsequently investigated using an AfBPP approach. 143 The drug is known to target the human cyclin‐dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), 144 a member of an important family of cell cycle regulators implicated in cancers and neurodegenerative diseases. 145 However, this compound has also been found to have an antiproliferative effect on a range of human protozoan parasites, including P. falciparum. 143 After examination of the x‐ray structure of purvalanol B in complex with human CDK2, it was established that the carboxylic acid group would make an appropriate handle for functionalization in an AfBPP as it would have minimal effect on binding (Figure 7). 144 Previous SAR indicated that the addition of a methyl group at the N6 position on analog 95 M significantly diminished CDK2 inhibitory activity so was used as a control in the AfBPP study (Figure 7). 146 The authors also found that large functionalities at N9 reduced CDK2 inhibition, therefore, they placed the linker at this position for use as an additional control (95‐N9). 146 Pulldown in P. falciparum resulted in a singular protein, casein kinase 1 (CK1). The authors found that purvalanol B did not significantly inhibit mammalian CK1, but potently inhibited PfCK1 (IC50 0.30 μM) despite the high sequence conservation. Unfortunately, this discovery has not resulted in further exploration of a CK1‐targeted antimalarial, however, the study has prompted the investigation of inhibitors in other protozoan parasitic species examined such as Leishmania and Trypanosoma. 147 , 148 , 149

Figure 7.

A resin immobilized chemical probe used in the identification of Plasmodium falciparum targets of the human cyclin‐dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) inhibitor purvalanol B. Purvalanol B and related inactive controls were immobilized via a PEG linker to an agarose resin for target identification in P. falciparum. Pulldown identified only one potential target, P. falciparum casein kinase 1 (PfCK1). [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3.5. Purfalcamine

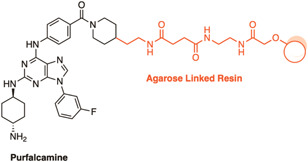

Purfalcamine was identified as a potent inhibitor of P. falciparum calcium‐dependent protein kinase 1 (PfCDPK1) from a target‐based screen of a kinase‐directed heterocyclic library. 150 To validate the parasite targets of purfalcamine, an agarose immobilized purfalcamine AfBPP was incubated with parasite lysate in the absence or presence of unlabeled purfalcamine (Figure 8). 150 The AfBPP pulled down a hypothetical protein (PF13_01116), a putative FAD‐dependent glycerol‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (PFC0275w), a conserved hypothetical protein (PFF0785w), and PfCDPK1. 150 The highly abundant pyruvate kinase was pulled down in both the competition and noncompetition conditions, therefore was not considered a specific target. Microscopic examination identified that purfalcamine caused cycle arrest at the schizont stage, 150 consistent with pfcdpk1 gene transcription supporting PfCDPK1 as the primary target. 151

Figure 8.

A resin immobilized chemical probe for validation of the cellular targets of purfalcamine. Pulldown with this probe identified several proteins with PfCDPK1 as the likely candidate. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3.6. Imidazopyridazine antimalarials

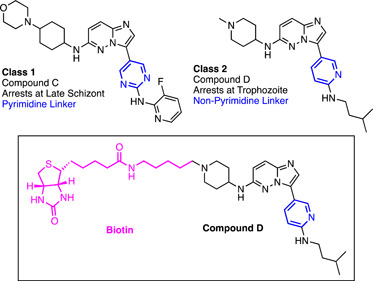

The imidazopyridazine antimalarial scaffold was discovered in another target‐based screen against PfCDPK1 employing two different compound libraries. 152 The first was a library containing a diverse set of 35,422 compounds, and the second was the BioFocus kinase library. This identified a number of scaffolds with sub‐nanomolar inhibitory activity against PfCDPK1, including the imidazopyridazine chemotype. While compounds of this class were indeed active against asexual P. falciparum parasites, the subsequent SAR studies indicated that the level of PfCDPK1 inhibition correlated poorly with the inhibition of parasite growth. 153 Subsequent chemical genetics altering the kinase sensitivity to inhibitors established that inhibition of PfCDPK1 did not alter parasite viability in asexual stages, ruling it out as a potential target. 154 This also called into question the validity of PfCDPK1 as a legitimate target for the previously mentioned 2,6,9‐purine purfalcamine. Phenotypic studies were therefore initiated on imidazopyridazine analogs, where it was discovered that two sub‐structural imidazopyridazine classes had distinct mechanisms of action depending on their aromatic linker. Compounds with a pyrimidine‐linker arrested parasites at late schizogony, whereas the non‐pyrimidine‐linker arrested parasites at trophozoite stage (Figure 9). 154

Figure 9.

Imidazopyridazine compounds identified using a target‐based screen against PfCDPK1. Two classes of imidazopyridazine compounds were identified, differing in their aromatic linker. Class 1 imidazopyridazines possessed a pyrimidine linker and arrested parasites at the late schizont stage. Class 2 imidazopyridazines are linked via nonpyrimidine aromatic rings and arrest at the trophozoite stage. Biotinylation of compound D enabled streptavidin affinity pulldown for the identification of cellular targets. The probe identified the molecular chaperone PfHSP90 as a potential target for the compound. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The authors noted the schizontocidal activity of class 1 matched phenotype of a kinase closely related to PfCDPK1, cGMP‐dependent kinase (PKG). 154 Indeed, the antiparasitic SAR of class 1 compound closely correlated with PKG IC50. 154 Additionally, chemical genetics performed on PKG identified a link between the kinase's sensitivity to the inhibitor and parasite viability. 154 For target identification of class 2 nonpyrimidine targets, an affinity pulldown approach was taken. Compound D (Figure 9) was conjugated to biotin for affinity capture of targets with streptavidin‐agarose. This pulldown only identified one significant target—HSP90, a molecular chaperone containing an ATP binding site that is essential for mediating the transition from ring to trophozoite development. 155 Recombinant PfHSP90 binding assays were subsequently used to confirm compound interaction of 6.17 μM, similar to another HSP90 inhibitor 17‐AAG which also blocks parasite development at the trophozoite stage. 154 The authors considered this to be a promising target, although could not rule out other targets not able to be pulled down in this study. Indeed, a discrepancy between the potent 360 nM cellular activity and weak protein binding points to this possibility. Heat shock proteins are well‐known promiscuous binders as a function of their role in protein folding. 156 Accordingly, HSP90 is included in the CRAPome, a repository for common nonspecific binders in AfBPP for the human and yeast proteomes. 156 Without a negative control compound or competition experiment nonspecific interactions cannot be ruled out for this target.

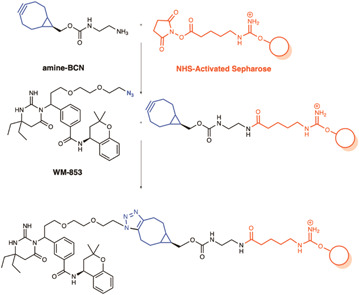

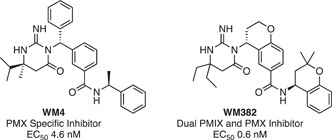

3.3.7. Plasmepsin X

Plasmepsins are aspartic proteases, some of which are essential and are potential drug targets, including plasmepsin IX and X (PMIX and PMX) which are involved in the parasite invasion and egress pathway. 157 , 158 Following a high‐throughput screen of an aspartic protease inhibitor library, it was discovered that a novel scaffold inhibited P. falciparum growth with nanomolar potency. 159 By selecting for resistance, PMX was determined as a probable target of these compounds. 159 An AfBPP approach was implemented to validate PMX as the target of these compounds. First, a hemagglutinin A (HA) tagged PMX parasite line was developed that would be used to detect the target protein by western blot with anti‐HA antibodies. 159 A click chemistry AfBPP approach was then used to construct the chemical probes (Figure 10). The solid support was first synthesized, attaching the strained cyclooctyne amine‐BCN to NHS‐Sepharose via its terminal amine. Next, the lead active compound (WM382) was modified with an azide moiety by a PEG linker to give the probe called WM853. Copper‐free click chemistry was used to attach these two hemispheres together for the final pulldown. Due to the stage‐specific expression of PMX, the pulldowns were performed using the lysate of late schizont stage saponin‐treated parasites. Western blot identified efficient pulldown of PMX which was interrupted by the presence of free excess lead compound WM382. Interestingly, WM382 also inhibits PMIX at a lower affinity than PMX, 160 but was not pulled down in this study, highlighting the requirement for high‐affinity ligands for successful pulldown of genuine targets.

Figure 10.

SPAAC probes used in the target validation of WM382 against plasmepsin X. An azide functionalized derivative of the lead compound (WM‐853) was used to attach the compound of interest to a Sepharose resin using SPAAC copper‐free conditions. These probes were incubated with lysate from an HA‐tagged PMX parasite line where PMX was identified as a binder by western blot with an anti‐HA antibody. Pulldown of PMX was competitively inhibited by the addition of the parent compound WM382. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.4. Activity based protein profiling examples

ABPPs based on antimalarials that typically covalently engage their protein targets are by their very nature reactive and therefore potentially have several targets rather than one exclusive target. These ABPPs typically pulldown many protein targets, which can be difficult to deconvolute and determine whether each protein is a genuine binding protein. A key example in the following section is the endoperoxide antimalarials which are known to mechanistically cross‐link with many proteins, and therefore using the ABPP method it has been difficult to reliably detect target proteins.

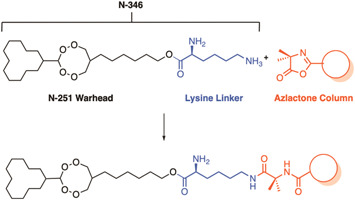

3.4.1. N‐251 and N‐89

ABPPs were implemented to identify the targets of novel endoperoxide drugs N‐251 and N‐89. 161 In the ABPP design, a lysine linker was coupled to the hydroxyl group of N‐251, termed N‐346, for conjugation to the resin functionalized with an azlactone (Figure 11). 161 PfERC, Pf14‐3‐3, and PfHSP70 were the highest enriched proteins from the pulldown with the N‐346 ABPP. Subsequently, differential protein expression analysis confirmed that the expression of these proteins was altered by treatment with N‐251 and N‐89. 161 The latter two are unlikely targets as they are known to promiscuously bind compounds in their roles as kinase regulator and molecular chaperone, respectively. 162 PfERC is an essential ER‐resident protein, important for asexual parasite egress. 163 N‐251 and ‐89, but not the related endoperoxide, artemisinin, were subsequently confirmed to bind weakly to PfERC by surface plasmon resonance (K D 1.6 × 10–4 M and 3.8 × 10–3 M). 161 The binding of these compounds may represent a mechanism for these novel endoperoxides or may be the result of nonspecific binding.

Figure 11.

A resin immobilized chemical probe for the novel endoperoxide N‐251. The novel endoperoxide N‐251 was linked to an azlactone Sepharose resin via a lysine linker to create the probe N‐346. Treatment with cellular lysate resulted in the enrichment of PfERC, Pf14‐3‐3, and PfHSP70. Weak binding of N‐251 and N‐89 to PfERC was confirmed subsequently by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

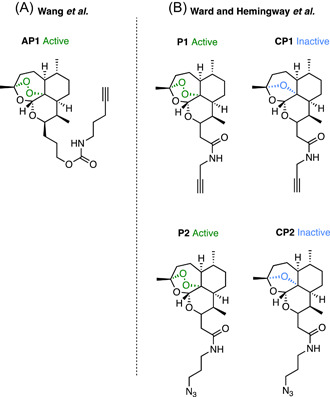

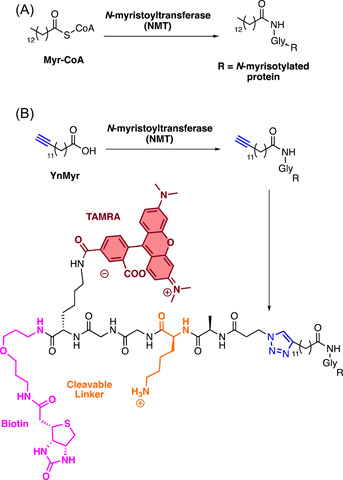

3.4.2. Artemisinin

Two concurrent seminal studies on the mechanism of Artemisinin by Wang et al. 164 and Ward and Hemingway et al. 165 utilized ABPPs with click chemistry handles. This method allowed for the in situ use of the probes which is important given the evidence of site‐specific activation of the endoperoxide moiety. 166 Both studies attached the click chemistry handles via a linker to the C10 position of the ART structure which proved not to significantly reduce antiparasitic activity. 164 , 165 Differences in linker structure and size separate the two studies (Figure 12), where Ward and Hemingway et al. denote their probes as P1 and P2 while Wang et al. denote their probe as AP1. AP1 features a much longer carbamate linker, terminating in an alkyne click chemistry handle (Figure 12A). 164 P1 and P2 feature a short amide linker, deliberately chosen by the authors to avoid issues with cytotoxicity that have been reported with longer amide linkers (Figure 12B). 167 Both alkyne and azide handles were conjugated for comparison of copper‐mediated and copper‐free click conditions due to previous studies proposing the potential for copper to activate artemisinin in a similar manner to iron in hemozoin. 168 A final difference between the two studies is the use of inactive control ABPPs by Ward and Hemingway et al. who constructed corresponding non‐peroxidic probes CP1 and CP2 which were inactive against parasites. Despite these differences, the workflow of the two studies was similar. Live parasites were exposed to the probes to allow for protein alkylation and proteins were subsequently extracted. The extracts were combined with a clickable functional group, either a fluorophore for in‐gel fluorescence analysis or biotin conjugate for streptavidin bead affinity capture. P1, P2, and AP1 all alkylated a large number of proteins by in‐gel fluorescence. 164 , 165 Control probes CP1 and CP2 did not show any alkylation by in‐gel fluorescence. 165 The authors found AP1 alkylation to be dose‐dependent, unobservable in uninfected erythrocytes, and antagonized by co‐incubation with free radical scavengers. 164 This supports the parasite‐specific activation of the scaffold and the formation of a free radical.

Figure 12.

Artemisinin‐based click chemistry probes. (A) Alkyne and azide click chemistry probes by Hemingway and Ward et al. identified 42 common proteins in an affinity pulldown, with a majority containing a glutathione binding motif which may be particularly susceptible to radical alkylation. When P1 was retested by Maser et al. with additional controls far fewer proteins were pulled down, none of which were found in the original study. (B) Alkyne probe AP1 pulled down 125 high‐confidence proteins with similar pathway coverage to the P1 and P2 probes. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

When coupled to the streptavidin beads, probes P1, P2, and AP1 similarly pulled down a wide range of targets involved in many essential pathways. 164 , 165 P1 identified 58 high‐confidence proteins, four of which were pulled down nonspecifically in low abundance by the inactive CP1 probe. 165 P2 pulled down 62 proteins, 42 of which were in common with P1, 165 while the control azide probe CP2 did not pull down any protein nonspecifically. 165 The copper‐free method with P2 appeared to detect these proteins with greater sensitivity due to the high efficiency of the strain‐promoted click reaction with the DIBO cyclooctyne. 165 P2 was also assessed with cell lysate and showed no significant difference in the labeling of proteins. 165 AP1, on the other hand, pulled down high confidence 124 protein targets, including a further 125 proteins pulled down in repeat experiments. 164 It has been suggested that the larger range of identified targets is due to the increase in linker size and thus lipophilicity. 165 This cannot be assessed without the comparison of an inactive control for AP1.

The overall coverage of parasite pathways between the ABPP types appears to be similar. Alkylated proteins converge on a subset of pathways, including glycolysis, nucleic acid biosynthesis, protein biosynthesis, invasion, protein transport, and redox antioxidant defense. 164 , 165 Notably, a substantial number of the proteases involved in hemoglobin digestive pathway in the DV were labeled, including plasmepsin I, plasmepsin II, and cathepsin D. 164 , 165 However, the incomplete labeling of proteases in this pathway (e.g., falcipain II and falcipain III) suggests a degree of selectivity to ART‐protein alkylation. 164 , 165 Analysis of targets pulled down by P1 and P2 indicated a correlation with proteins that had a glutathione binding motif. 164 The authors suggested this free thiol may be an easy target for the ART free radical which has previously been shown to form cysteine adducts. 169 The formation of these adducts may directly contribute to the specificity seen above to aspartic and cysteine proteases in the DV hemoglobin digestion pathway.

Interestingly, alkylated targets of P1 and P2 were shown to be differentially affected by the addition of the iron chelator, DFO. The plasmepsins and the majority of the glycolytic enzymes were not significantly affected by DFO treatment, whereas ornithine aminotransferase (PfOAT) was. 165 PfOAT was also identified as a target of AP1, and in vitro biochemical analysis showed that binding occurred only in the presence of added haemin. 164 This binding was further enhanced by the addition of reagents that reduced hemin to heme (Vitamin C, GSH, and Na2S2O4). 164 The addition of ferrous iron, on the other hand, had no impact on the binding of AP1 to PfOAT. 164 Additionally, the binding of AP1 to PfOAT appeared to be protein structure‐dependent as heat denaturation of PfOAT diminished binding. 164

Both studies also explored the mechanisms of ART activation. Ward and Hemingway et al. tested the effect of DFO pre‐treated cellular homogenates on P1 alkylation and found that it significantly reduced but not ablated pulled down proteins. 165 This data suggested that ART may be involved in a nonferrous iron‐mediated activation pathway, although this notion was questionable as the concentration of DFO used for chelation in live parasites and in free heme homogenates were significantly different. 170 Wang et al. then tested the effect of iron chelating agents DFO and DFP (deferiprone) in live parasites which did not result in a significant reduction in AP1 protein alkylation by in‐gel fluorescence. 164 However, a cysteine protease inhibitor N‐acetyl‐Leu‐Leu‐Norleu‐al (ALLN) that inhibits the production of heme via the parasite hemoglobin digestion pathway, 171 caused a significant decrease in the fluorescent labeling of proteins by AP1. Together, this points to heme as the predominant source of ART activation. 164 However, this fails to explain the activity of ART in the early ring stage, where hemoglobin digestion does not occur. 172 The authors surmised that hemoglobin biosynthesis that occurs at this stage could be a source of heme for ART activation. To test this, synchronized early ring parasites were pretreated with the hemoglobin synthesis inhibitor SA which proved to reduce the level of ART protein binding by AP1. 164 Hemoglobin digestion inhibitor ALLN also had no effect on AP1 alkylation in ring stages. 164

Maser et al. 173 later re‐evaluated the same probes from Ward and Hemingway et al. 165 (P1 and CP1, Figure 12B) with additional controls. The authors included a DMSO‐treated control, an ART‐treated control, the nonperoxidic control CP1 as well as multiple probe concentrations. 173 Remarkably, the proteins alkylated by this experiment had little in common with the targets identified by Ward and Hemmingway et al. 165 At a concentration of 100 ng/mL P1 alkylated 15 specific proteins, none of which were present in the original study. 173 1000 ng/mL P1 alkylated an additional eight unique proteins, only one of which was identified in the original study. 173 The targets identified by Maser et al. were more analogous to Wang et al. 164 with AP1 with 10 and 6 proteins in common for 100 and 1000 ng/mL concentrations of P1, respectively. 173 Some targets identified by the previous studies, such as DHFR, were identified in the negative controls of this study and therefore were removed from consideration. 173 The authors concluded that this variation in ART alkylation is the result of a stochastic binding pattern that may be more linked to radical proximity rather than any specificity. 173

What is clear from these studies is that the vast number of targets alkylated by ART contribute to its parasite lethality. Glutathionylated proteins appear to represent a large proportion of these targets, presumably due to their susceptibility to alkylation. The peroxide bond is responsible for its activity which is the site of free radical formation. ART also accumulates specifically in infected erythrocytes where it appears heme is responsible for the majority of its activation in later parasite stages. A limitation of these studies is that they do not explore potential noncovalent targets of ART, nor potential nonprotein targets such as heme. 173 It is also evident that the structure of the probes can vastly affect the results of the pulldowns. This highlights the importance of careful probe design and confirmation of potential targets with other means of target identification or biochemical analysis.

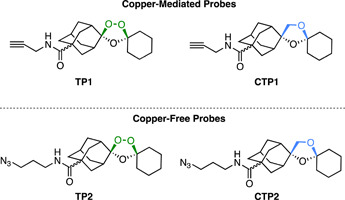

3.4.3. 1,2,4‐Trioxolanes

Based on the rational design of ART‐based probes, 165 synthetic endoperoxide 1,2,4‐trioxolane ABPPs were constructed. 174 The probes were designed with minimal linker size and thus lower lipophilicity on the basis of greater specificity and pharmacological relevance. 174 Both alkyne (TP1) and azide (TP2) functionalities were used to assess the utility of copper‐mediated and copper‐free methods (Figure 13). Finally, non‐peroxide probes were again synthesized as inactive controls (CPT1 and CPT2; Figure 13). To assess the specificity of the probes, in‐gel fluorescence was determined by clicking on an Alexa Fluor 488 tag. 174 As was previously observed with the ART probes, the azide probe TP2 had greater labeling intensity due to the efficiency of the copper‐free strain‐promoted cycloaddition reaction. 165 The protein alkylation profile of TP2 was then compared against the analogous ART probe P2 (Figure 12). 165 The results of the affinity purification were overwhelmingly similar between the two chemotypes. Of 62 total pulled down proteins, 53 of these were identical. 174 The roles of these proteins were again in heme digestion, energy supply, DNA synthesis, and antioxidant defense systems. 174 Interestingly, 70% of the proteins identified were glutathionylated, supporting the theory that the radical formed by heme activation reacts with the disulfide bond present at the site of this posttranslational modification. There were six proteins identified that appeared in one experimental replicate but not the other, 164 demonstrating the importance of experimental design in ABPP studies.

Figure 13.

Structures of ozonide click‐chemistry probes TP1 and TP2 and their inactive nonperoxidic control compounds CTP1 and CPT2 synthesized by O'Neill et al. Probes based on an alkyne handle (above) were optimized for a copper‐mediated click reaction, whereas probes with an azide handle (below) use copper‐free methods. 53 common proteins were identified between the two probes with diverse roles, although the majority were glutathionylated. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Alongside the re‐evaluation of the ART probe P1 (Figure 12), Maser et al. constructed novel alkyne functionalized 1,2,4‐trioxolanes (OZ726 and OZ727, Figure 14). 173 Stringent controls were used including DMSO pretreatment, parent compound OZ03 pretreatment and the use of a non‐peroxidic control carbaOZ727. Interestingly, the degree of overlap between the targets of OZ726 and OZ727 was only 30% (6 of 20 proteins). 173 Indeed, there was no overlap between the proteins alkylated in this study to those of TP1 and TP2 (Figure 13). 174 This again illustrates how influential the structure of probes can be to the target profile. In direct comparison with the ART probe P1, the overlap in specificity was just 17% and 13% for OZ726 and OZ727, respectively. 173 When tested at a 10‐fold higher concentration, OZ726 alkylated 9 of the 11 proteins identified by P1 at the same concentration. 173 However, an additional 16 proteins were identified by OZ726 at this concentration that were not identified in any of the previous experiments. 173 As the authors concluded with P1, the alkylation of 1,2,4‐trioxolanes appears to be random, which is consistent with the irregular cellular localization of 1,2,4‐trioxolane fluorescent probes. 170 , 175 , 176

Figure 14.

Structures of bioorthogonal ozonide probes by Maser et al. The alkyne‐based copper click chemistry probes identified stochastically alkylated targets with little overlap between similarly structured probes OZ726 and OZ727. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

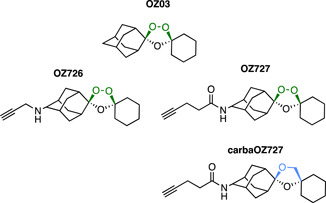

3.4.4. Salinipostin A

Salinipostin A (Sal A) is a marine natural product with low nanomolar activity against P. falciparum and has an unknown mechanism of action. Previous mechanistic studies had been unable to generate resistant parasites which suggests that the compound may act through multiple essential pathways. 177 An alkyne tag was added to a Salinipostin A analog, Sal alk, to enable a range of functionalization for ABPP and fluorescence co‐localization studies. (Figure 15). 178 First, a TAMRA fluorescent label, azide was conjugated to Sal alk via click chemistry and upon treatment with parasites confirmed that multiple targets bound to the structure by in‐gel fluorescence. 178 The labeling of many of these proteins was completed with the addition of unlabeled Sal A in a dose‐dependent manner. 178 A biotin azide was also conjugated to the alkyne handle for pulldown streptavidin‐resin using parasite lysate pre‐incubated with Sal A or vehicle control. The 10 proteins most highly enriched in these experiments, all possessed classical α/β serine hydrolase domains (Ser‐His‐Asp catalytic triad or a Ser‐Asp dyad). 178 piggyBac mutagenesis studies have determined that four of these are essential for parasite viability, 179 although have not yet been confirmed as genuine binders in subsequent studies.

Figure 15.

Multi‐functional click chemistry probes of Marine natural product Salinipostin A (Sal A). This multi‐functional probe helped to identify 10 enriched proteins with a common α/β serine hydrolase domain, 4 of which were found to be essential for parasite survival. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

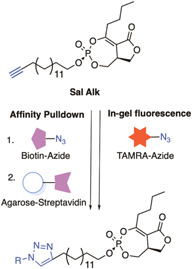

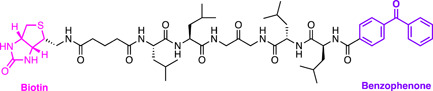

3.4.5. Myr‐CoA

The Plasmodium N‐Myristoyl Transferase (NMT) catalyzes the attachment of a myristate lipid tail from Myristoyl‐Coenzyme A (Myr‐CoA) to N‐terminal glycine on specific substrates in membrane trafficking (Figure 16A). 180 Despite its utility as a target in fungal and trypanosome infections, the genetic essentiality of NMT in P. falciparum had not yet been demonstrated. 181 , 182 Therefore, ABPPs were designed for use in an NMT substrate capture experiment. 183 The probe was constructed based on the structure of the enzyme substrate, Myr‐CoA, with an alkyne handle termed YnMyr‐CoA (Figure 16B). 183 A trifunctional capture reagent was also synthesized featuring a TAMRA fluorescent reporter, biotin affinity capture moiety, and a trypsin cleavable linker (Figure 16B). The cleavable linker allowed the specific identification of the site at which proteins were N‐myristoylated without external labeling, resulting in an unambiguous hydrophilic zwitterionic moiety that can be detected with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). 183 In‐gel imaging was employed to demonstrate that peptide tagging was dose‐dependent which could be competitively inhibited by excess free myristate. The pulldown experiments with avidin purification identified over 30 NMT substrates that have diverse functions including motility, protein transport, parasite development, and phosphorylation pathways. These included N‐myristoylated proteins that had been genetically validated for essentiality in other eukaryotes but not in P. falciparum. The wide diversity of the pulled down proteins identifies NMT as a promising drug target in P. falciparum.

Figure 16.

YnMyr probe developed for the recognition of P. falciparum N‐myristoylated protein targets. An analog of the MyrCoA with an alkyne handle (YnMyr) was constructed for capture with a trifunctional capture reagent. The terminal azide reagent contains a TAMRA fluorophore for in‐gel fluorescence, a biotin moiety for affinity capture, and a trypsin cleavable linker capable of acting as a tag for the identification of myristoylated proteins by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.5. Photo‐crosslinking probe examples

Photo‐crosslinking is generally introduced to an AfBPP or an ABPP to facilitate the covalent linkage of the probe with protein target(s) in parasites. This strategy, followed by a bioorthogonal method to validate the target, has been successfully used by several groups including examples based on the HEA class of protease inhibitors.

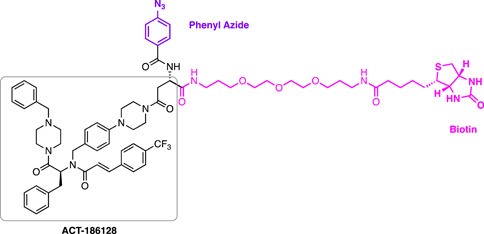

3.5.1. ACT‐186128

Photo‐crosslinking probes were also used to identify the target of the novel antimalarial ACT‐186128 discovered in a phenotypic screen. 184 A photo‐AfBPP was developed for application in live cells employing a phenyl azide photo‐crosslinking moiety and a biotin tag for both fluorescent labeling and affinity purification (Figure 17). 185 Live‐cell imaging enabled by the association of the Alexa488‐streptavidin fluorescent reporter with the biotin moiety showed localization throughout the cytoplasm in all parasite life stages, consistent with its lack of stage specificity. 185 Pulldown with streptavidin beads was performed after treatment of both intact parasitized red blood cells and saponin‐liberated parasites with the photo‐AfBPP. The pulldown with intact infected RBCs identified one target, the Pf multidrug resistance protein 1 (PfMDR1). 185 The pulldown with saponin‐isolated parasites identified over 20 targets with the highest enriched candidates being PfMDR1, Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter (PfENT4), hexose transporter, glideosome‐associated protein 50/secreted acidic phosphatase, and S‐adenosylmethionine synthetase. 185 The latter five were subsequently ruled out in biochemical validation studies, while PfMDR1 remained a viable target. 185

Figure 17.

ACT‐186128 chemical probe. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

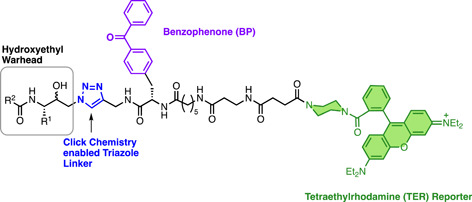

3.5.2. Aspartyl protease inhibitors

Hydroxyethyl amine (HEA)‐based inhibitors have been used to target aspartyl proteases in the Plasmodium parasite 157 , 186 , 187 and were designed as a non‐cleavable transition state mimic for the functional profiling and identification of plasmepsins. 188 At the time, just 5 of a putative 10 plasmepsins (PMs) had been identified in P. falciparum, the digestive vacuole PMs I‐IV (which are known to be non‐essential and redundant in function) 189 and plasmepsin V (which is essential for protein export to the host erythrocyte). 190 , 191 To validate that these HEA inhibitors genuinely bind to PMs, photo‐AfBPPs were developed possessing an azide click chemistry handle, benzophenone photo‐crosslinking group, and a tetramethylrhodamine (TER) fluorescent reporter (Figure 18). 188 The TER reporter enabled in‐gel fluorescent quantification and target binding was demonstrated with recombinant protein. 188 Exposure of the probes to parasite homogenates followed by two‐dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis and western blot analysis demonstrated that the probe bound to all four digestive PMs. 188

Figure 18.

Structure of multifunctional hydroxyethyl chemical probes used for the target identification. Pulldown identified all four known plasmepsins (I–IV) as targets for the hydroxyethyl warhead. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.5.3. Signal peptidase inhibitors

P. falciparum signal peptide peptidase (PfSPP) is an intra‐membrane aspartyl protease located within the parasite endoplasmic reticulum, responsible for the processing of membrane‐embedded signal peptides left behind by the secretory pathway. 192 PfSPP was hypothesized as a potential target for antimalarial therapy due to the sensitivity of P. falciparum to known human SPP and related aspartyl protease inhibitors such as (Z‐LL)2, LY‐411575, NITD679, and NITD731. 193 To validate SPP as the target protein of these inhibitors in P. falciparum, a multifunctional AfBPP was synthesized based on the peptidomimetic inhibitor (Z‐LL)2 (Figure 19). 193 The probe featured a biotin tag for affinity purification and a benzophenone moiety to facilitate covalent photo‐crosslinking. Photo‐labeling and affinity purification performed with parasite lysate successfully identified PfSPP binding via western blot analysis using anti‐PfSPP for detection. 193 Lysate pretreated with free (Z‐LL)2, LY‐411575, NITD679, and NITD731, and all demonstrated a competitive reduction in PfSPP pulldown by the probe. 193 Together, this validated that the known inhibitors of human SPP also targeted the Plasmodium homolog. 193

Figure 19.

Structure of multifunctional (Z‐LL)2 probe used for the target validation study. A benzophenone moiety enabled photoaffinity labeling, while the biotin moiety enabled affinity pulldown which could be detected via western blot for PfSPP. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

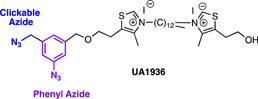

3.5.4. Albitiazolium

De novo phospholipid synthesis is an essential process for the growth and survival of Plasmodium parasites. 194 Therefore, the pathway has generated interest as a promising novel target for antimalarial chemotherapy. The primary phospholipid in P. falciparum membranes is phosphatidylcholine which consists of a choline phosphate head group that contains a quaternary ammonium moiety. 194 A series of highly potent antimalarial choline mimics, the bis‐thiazoliums, were developed based on the ability of quaternary ammonium salts to inhibit phospholipid metabolism. 195 Unfortunately, the lead compound stemming from this campaign, Albitiazolium, 196 has since been discontinued in Phase II pediatric trials due to a lack of efficacy. 197 Before this, its exact mechanism of action had been in question but was primarily considered to be impairing choline transport from the plasma. 198 Therefore, a bifunctional chemical probe UA1936 was developed featuring a phenyl azide moiety for covalent photo‐crosslinking as well as a benzyl azido which could be used as a clickable handle for affinity purification and fluorescent labeling (Figure 20). 199 An inactive AfBPP control, UA2050, was also included. 199 In live cells, fluorescent labeling using click chemistry with the benzyl azido group showed partial colocalization with ER and Golgi‐specific antibodies. 199 Pulldown was enabled with an alkyne agarose resin after incubation of the probe in whole saponin‐liberated parasites. These parasites were pretreated with either vehicle control or free Albitiazolium. 199 Two proteins were specifically enriched by the UA1936 AfBPP. One of these proteins is choline/ethanolamine phosphotransferase (CEPT) which performs the final step in phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine biosynthesis. This was unsurprising as Albitiazolium was previously found to inhibit CEPT activity. 198 The other is a protein (PFL1815c) with an uncharacterized function. Only CEPT was competitively displaced by treatment with Albitiazolium, confirming it as the target of this antimalarial compound class. 199

Figure 20.

Structure of Albitiazolium bifunctional probe. Photo‐crosslinking and click chemistry affinity purification resulted in the identification of choline/ethanolamine phosphotransferase (CEPT) as a promising target. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.5.5. Diaminoquinazoline