Abstract

Fetal growth restriction (FGR) significantly contributes to neonatal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. Currently, there are no effective treatment options for FGR during pregnancy. We have developed a nanoparticle gene therapy targeting the placenta to increase expression of human insulin-like growth factor 1 (hIGF1) to correct fetal growth trajectories. Using the maternal nutrient restriction guinea pig model of FGR, an ultrasound-guided, intraplacental injection of nonviral, polymer-based hIGF1 nanoparticle containing plasmid with the hIGF1 gene and placenta-specific Cyp19a1 promotor was administered at mid-pregnancy. Sustained hIGF1 expression was confirmed in the placenta 5 days after treatment. Whilst increased hIGF1 did not change fetal weight, circulating fetal glucose concentration were 33%–67% higher. This was associated with increased expression of glucose and amino acid transporters in the placenta. Additionally, hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment increased the fetal capillary volume density in the placenta, and reduced interhaemal distance between maternal and fetal circulation. Overall, our findings, that trophoblast-specific increased expression of hIGF1 results in changes to glucose transporter expression and increases fetal glucose concentrations within a short time period, highlights the translational potential this treatment could have in correcting impaired placental nutrient transport in human pregnancies complicated by FGR.

Keywords: fetal growth restriction, insulin-like 1 growth factor, placenta, pregnancy, therapeutic

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Fetal growth restriction (FGR: estimated fetal weight <10th percentile) occurs in up to 10% of pregnancies with suboptimal fetal nutrition and uteroplacental perfusion accounting for 25%–30% of cases (Bamfo & Odibo, 2011; Resnik, 2002). Perinatal outcomes depend largely on the severity of FGR, and FGR is a leading cause of infant morbidity and mortality (Bernstein et al., 2000). Additionally, FGR has been implicated in contributing to the development of long-term health outcomes including increasing the risk for future cardiovascular and endocrine diseases such as diabetes (Crispi et al., 2018), as well as being associated with cognitive and learning disabilities (Leitner et al., 2007). At present, there is limited preventative strategies and no effective treatment options for FGR. However, advances in nanomedicine are allowing for the development of potential therapeutics to treat the placenta and correct fetal growth trajectories (Pritchard et al., 2020).

Currently, there are a number of studies being undertaken that are designed at specifically targeting the placenta to improve pregnancy outcome (Ganguly et al., 2020; Wilson & Jones, 2021a). Furthermore, advances in nanoparticle capabilities, which exploit existing cellular uptake mechanisms, are allowing for the delivery of drugs, gene therapies and other pharmacological agents with maximized efficiency in smaller doses (Bamrungsap et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2010). We are developing the use of a polymer-based nanoparticle gene therapy that facilitates nonviral gene delivery specifically to the placenta (Abd Ellah et al., 2015; R. L. Wilson et al., 2020). Using a synthetic HPMA-DMEAMA (N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide-2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate) diblock copolymer, complexed with a plasmid containing the human insulin-like 1 growth factor (hIGF1) gene under the control of placenta trophoblast specific promotors (PLAC1 and CYP19A1), we have shown efficient nanoparticle uptake into human syncytiotrophoblast ex vivo (R. L. Wilson et al., 2020) and increased placenta expression of hIGF1 that is capable of maintaining fetal growth in a surgically-induced mouse model of FGR (Abd Ellah et al., 2015). Most importantly, we have shown this technology to be safe to both mother and fetus, as both the nanoparticle and plasmid do not cross the placental syncytium, and treatment has never been associated with maternal morbidities, or increased fetal loss (Abd Ellah et al., 2015; R. L. Wilson et al., 2021b; Wilson et al., 2021c).

In pregnancies complicated by FGR, reduced placental glucose and amino acid transport capacities has consistently been shown, and animal models report downregulation of placenta transport systems before the development of FGR (Dumolt et al., 2021). Both active and passive nutrient transport systems maintain placental nutrient supply to the fetus (Jones et al., 2007). In humans, maternal-fetal exchange of oxygen, nutrients and waste occurs across the syncytiotrophoblasts (the multinucleated syncytium that serves as the primary barrier between maternal and fetal blood) and fetal capillary endothelium (Dumolt et al., 2021). Whilst the fetal capillary endothelium largely allows unrestricted transfer of small molecules and ions, it is the syncytiotrophoblasts which express the array of nutrient transporter proteins critical of mediating active transport of nutrients and waste (Burton & Fowden, 2015). Changes in nutrient transporter capabilities in the placenta are often associated with dysregulation of metabolic hormones, like IGF1, which co-ordinate the flux of glucose, amino acids and lipids. IGF1 is a secreted protein produced by the placenta throughout pregnancy (Fowden, 2003). Through binding with the IGF1 receptor (IGF1R), it regulates numerous aspects of placenta function including metabolism, mitogenesis, and differentiation (Sferruzzi-Perri et al., 2017). Furthermore, we and others have demonstrated that increased placental expression of IGF1 is capable of upregulating glucose and amino acid transport to the fetus and thus modulating fetal growth (Jones et al., 2013, 2014; Keswani et al., 2015).

Development of a treatment for FGR is made more difficult by the lack of definitive ways to predict FGR before diagnosis, and as such, effective therapies must be capable of correcting the effects of existing placental dysfunction. Guinea pigs offer a unique advantage in studying the placenta, fetal development, and reproductive health as they have similar developmental milestones to humans both throughout gestation and following birth (Kunkele & Trillmich, 1997; Morrison et al., 2018). Guinea pig placentas better reflect humans over other small animal species (Enders & Blankenship, 1999), exhibit deeper placental trophoblast invasion (Mess, 2007), and undergo changes to the maternal hormonal profile throughout pregnancy that more closely resemble humans (Hilliard, 1973). Additionally, non-invasive, maternal nutrient restriction (MNR) where dam food intake is restricted to 70% 4 weeks before pregnancy until mid-gestation and 90% thereafter, induces FGR (Elias et al., 2016; Sohlstrom et al., 1998). Here, we aimed to characterize placenta uptake of nanoparticle and the effect of increased hIGF1 expression on placenta morphology and glucose transport in the guinea pig MNR model of FGR.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Synthesis of poly(2-hydroxypropyl methacrylamide (PHPMA115-ECT))

In a 25 ml round bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar, ECT (4-cyano-4-(ethylsulfanylthiocarbonyl) sulfanylvpentanoic acid; 0.025 mmol, 0.006 g), HPMA (5 mmol, 0.715 g), and AIBN (2,2′-azo-bis-isobutyrylnitrile; 0.0025 mmol, 0.0004 g) were dissolved in DMF (dimethyl formamide; 5 ml) and sealed with septa. The solution was degassed for 30 min by purging with ultrahigh purity nitrogen and submerged into a preheated oil bath at 65°C. After 24 h, the crude polymerization mixture was purified through precipitation into cold diethyl ether. The pale-yellow color polymer was dried overnight under vacuum and the structure of the polymer was characterized by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

2.2 |. Synthesis of diblock copolymer of poly(2-hydroxypropyl methacrylamide-b-N, N-dimethyl aminoethyl methacrylate) (PHPMA115-b-PDMAEMA115)

RAFT (reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer) polymerization of DMEAMA was performed using PHPMA115-ECT as a macro-chain transfer agent (CTA) and AIBN as a free radical initiator. A solution of PHPMA115-ECT (0.031 mmol, 0.51 g), DMAEMA (4.65 mmol, 0.73 g, 0.782 ml), and AIBN (0.0031 mmol, 0.0005 g) in methanol (5 ml) was degassed for 30 min through purging with high purity nitrogen. To initiate the polymerization, the reaction flask was submerged in preheated oil at 70°C. The crude polymerization mixture was precipitated three times into cold pentane and dried under high vacuum after 24 h. The precipitated polymer was dissolved into methanol and dialyzed first against methanol for 24 h and then against deionized water for another 48 h. The dialyzed polymer was lyophilized to obtain a white powder, and formation of the diblock copolymer was confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

2.3 |. Nanoparticle formation

Nanoparticles were formed by complexing plasmids containing either the GFP or hIGF1 gene under control of placental trophoblast specific promotors PLAC1 or CYP19A1 with a nonviral PHPMA115-b-PDMEAMA115 co-polymer. All plasmids used were cloned from a pEGFP-C1 plasmid (Clonetech Laboratories), replacing the CMV promotor with either the PLAC1 or CYP19A1 promotor, and the GFP gene with hIGF1. The dialyzed polymer was resuspended in sterile water at a concentration of 10 mg/ml, then mixed with plasmid at a ratio of 1.5 μl polymer to 1 μg plasmid, and made to a total injection volume of 200 μl with sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Characterization of the physiochemical properties, and cellular safety and efficiency of the PHPMA115-b-PDMEAMA115 co-polymer complexed with the pEGFP-C1 plasmid to form the nanoparticle has been published previously (Abd Ellah et al., 2014). To initially determine nanoparticle uptake and promotor recognition in the guinea pig placenta, polymer was conjugated with a Texas Red fluorophore, described previously (R. L. Wilson et al., 2020).

2.4 |. Animal care and transuterine, intraplacental nanoparticle injections

Female (dams) Dunkin-Hartley guinea pigs were purchased (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) at 500–550 g and housed individually in a temperature-controlled facility with a 12 h light-dark cycle. Whilst acclimatizing to the facilities and for initial investigations into nanoparticle uptake in the placenta, food (LabDiet diet 5025: 27% protein, 13.5% fat, and 60% carbohydrate as % of energy) and water was provided ad libitum. Animal care and usage was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center (Protocol Number: 2017–0065) and University of Florida (Protocol Number: 202011236). See schematic S1 in Supporting Information Material for outline of experimental design.

In the initial studies to determine nanoparticle uptake and transgene expression in the guinea pig placenta, the Texas Red conjugated polymer was complexed with plasmid containing the GFP gene. Dams (n = 6; 2 sham, 2 Plac1 promotor, 2 Cyp19a1 promotor) were time mated through daily monitoring of the estrus cycle by inspecting perforation of the vaginal membrane (R. Wilson et al., 2021). Ovulation was assumed to occur when the vaginal membrane was fully perforated and designated gestational day (GD) 1. Pregnancy confirmation ultrasounds were performed at GD21. At GD30 (mid-pregnancy), dams underwent an ultrasound-guided, transuterine, intraplacental nanoparticle injection (containing 60 μg plasmid in 200 μl injection) or sham injection (200 μl of PBS) using a 32G × 1-inch needle placed into the placental labyrinth as close to the visceral cavity as possible. This time point was chosen because this is the earliest point in the guinea pig pregnancy where fetuses are growth restricted. Dams were anaesthetized using isoflurane, and their abdomen shaved and cleaned using isopropanol. Ultrasounds were performed using a Voluson I portable ultrasound machine (GE) with a 125 E 12 MHz vascular probe (GE). The abdominal cavity was scanned to determine the number and location of fetuses within the uterine horns. Where possible, the uterine horn which contained only a single fetus was chosen to receive the nanoparticle treatment. The fetuses on the opposite horn were left untreated, keeping consistent with our previous mouse studies (Abd Ellah et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2021c). On the minimal occasion that all fetuses were located in the same uterine horn, the placenta of the fetus located closest to the cervix was injected. Following injection, the placenta was briefly monitored using the ultrasound for signs of hemorrhage and fetal heart beat monitored to ensure no immediate fetal demise. Dams were then allowed to recover in a humidicrib maintained at 37°C before being return to their home cages. Euthanasia occurred 30 h after injection by carbon dioxide asphyxiation followed by cardiac puncture and exsanguination. The gravid uterus was dissected and fetuses and maternal-fetal interface weighed. Maternal and fetal organs including heart, lungs, liver, kidney and brain were collected. These tissues, along with the maternal-fetal interface, were halved and either fixed in 4% wt/vol paraformaldehyde (PFA) or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Tissues placed in PFA were left at 4°C until appropriately fixed, transferred to 30% wt/vol sucrose solution and then rapidly frozen in OCT and stored at −80°C.

To determine the effect of hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment on placental function under adverse maternal conditions, dams were weighed, ranked from heaviest to lightest, and systematically assigned to either the control diet group (n = 7) where food and water was provided ad libitum, or maternal nutrient restricted group (MNR; n = 12) so that mean weight was no different between the control and MNR groups. MNR dams were provided water ad libitum however, food intake was restricted to 70% per kilogram body weight of the control group from at least 4 weeks preconception through to mid-pregnancy (GD30), thereafter increasing to 90% (Elias et al., 2016; Sohlstrom et al., 1998). Time mating and pregnancy confirmation ultrasounds were performed as previously described; dams not confirmed pregnant were re-mated with all but one dam falling pregnant within three mating attempts. At GD30–33, dams underwent an ultrasound-guided, transuterine, intraplacental injection of hIGF1 nanoparticle (MNR + hIGF1; n = 7), or sham injection (control; n = 7 and MNR; n = 5) as previously described. Inaccessibility to surgical facilities over weekends prevented injections being performed at the exact same time point in pregnancy. Plasmid expression of hIGF1 is transient as the plasmid does not integrate into the genome. We have shown in mice placentas in vivo, a decline in the presence of nanoparticle, based on Texas-red fluorescence, with the placenta (Fry et al., 2015) but robust messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of plasmid-specific hIGF1 at 96 h after injection (Abd Ellah et al., 2015). Therefore, we chose to sacrifice all dams 5 days after injection (GD35–38) to ensure that transient expression of plasmid hIGF1 was still present within the placenta. On the day of sacrifice, dams were fasted for 4 h, weighed and then euthanized as previously described. Glucose concentrations in both maternal and fetal blood was measured using a glucometer. Tissue collection was performed as previously described, however, tissue placed in PFA was processed and paraffin embedded following standard protocols. Fetal sex was determined by examination of the gonads and confirmed using PCR as previously published (Wilson et al., 2021b).

2.5 |. Fluorescent microscopy of nanoparticle uptake

Placenta and fetal liver tissue from dams treated with the Texas Red-GFP nanoparticle were assessed microscopically for nanoparticle uptake and transgene expression. A total of 7 μm thick tissue sections were obtained, OCT was cleared by washing in ice-cold PBS, nuclei counterstained with DAPI (Invitrogen), and mounted using Prolong Gold Antifade mounting medium (Invitrogen). Texas Red and GFP fluorescence was visualized using the Nikon Eclipse Ti Inverted microscope. Exposure time was set using sham treated tissue to eliminate auto- and background fluorescence and thus, any fluorescence observed was due to the presence of nanoparticle (indicated by Texas-Red fluorescence) or plasmid expression (indicated by GFP fluorescence).

2.6 |. In situ hybridization (ISH) for plasmid-specific mRNA

ISH of plasmid-specific hIGF1 was performed on maternal-fetal interface tissue treated with nanoparticle gene therapy to confirm sustained transgene expression 5 days after injection as previously described (R. L. Wilson et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2021b). Two 5 μm thick paraffin embedded serial tissue sections were obtained. For the first section, ISH was performed using a BaseScope™ probe (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) custom designed to recognize the sequence between the stop codon and polyA signaling of the plasmid, following standard protocol. A section of human placenta explant treated with nanoparticle was included as a positive control. For the second section, immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed to confirm localization of plasmid-specific mRNA in placental trophoblast cells following standard IHC protocols. Following dewaxing and rehydrating, targeted antigen retrieval was performed using boiling 1X Targeted Retrieval Solution (Dako) for 20 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was suppressed by incubating sections in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min and then sections were blocked in 10% goat serum with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Jackson ImmunoResearch) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Anti-pan cytokeratin (Sigma C2562, 1:200 [10 μg/ml]) primary antibody was applied overnight at 4°C followed by an incubation with a biotinylated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibody (Vector BA-9200, 1:200 [10 μg/ml]) for 1 h at room temperature. The Vector ABC kit (Vector) was used to amplify staining and detected using DAB (Vector) for brown precipitate. Hematoxylin was used to counterstain nuclei. ISH was also performed on fetal liver sections to confirm the inability for plasmid to cross the placenta and enter fetal circulation 5 days after treatment. All sections were imaged using the Axioscan scanning microscope (Zeiss).

2.7 |. Placenta morphological analysis

For placenta morphometric analyses, 5 μm thick, full-face sections of maternal-fetal interface were stained with Masson’s trichrome stain and double-label IHC. Sections were de-waxed and rehydrated following standard protocols. To visualize the placenta, sub-placenta and decidual regions, Masson’s trichrome (Sigma) was performed as per manufacturers specifications. Whole section imaging was performed using the Axioscan Scanning Microscope (Zeiss) and placenta and sub-placenta/decidua areas were measured using the Zen Imaging software (Zeiss). For double-label IHC, fetal capillary endothelium and placental trophoblasts were distinguished using anti-vimentin (Dako Vim3B4, 1:100 [0.5 μg/ml]) and anti-pan cytokeratin (Sigma C2562, 1:200 [10 μg/ml]) antibodies, respectively (Sferruzzi-Perri et al., 2006) (Figure S1). Antigen retrieval was performed with 0.03% protease (Sigma) for 15 min at 37°C and endogenous peroxide activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min. The sections were then blocked with serum-free protein block (Dako) for 10 min before anti-vimentin antibody was applied to slides, diluted in 10% guinea pig serum and 1% BSA, and left overnight at 4°C. Biotinylated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Vector BA-9200, 1:200 [10 μg/ml]) was diluted in 10% guinea pig serum with 1% BSA and applied to sections for 30 min. Antibody staining was amplified using the Vector ABC kit (Vector) for 40 min and visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB; Vector) with nickel to create a black precipitate. This process, from the protein block, was then repeated for anti-pan cytokeratin, however the anti-pan cytokeratin antibody remained on the sections for 2 h at room temperature and nickel was omitted from the DAB so as to form a brown precipitate. Counterstaining occurred using hematoxylin. For detailed analysis of the labyrinthine structure, the proportion of trophoblast, fetal capillaries and maternal blood space (MBS) was calculated using point counting with an isotropic L-36 Merz grid (Roberts et al., 2003). Double-labeled sections were imaged using the Axioscan (Zeiss) and then 10 random ×40 fields of view were captured. Each field of view was then counted as described in (Roberts et al., 2003). Interhaemal distance of the MBS and between the MBS and fetal capillaries was also calculated using the Merz grid and line intercept counting. Within-assay variation of <5% was confirmed with repeated measurement.

2.8 |. RNA isolations and quantitative PCR (qPCR)

For gene expression analysis, approximately 150–200 mg of snap frozen placenta tissue was lysed in RLT-lysis buffer (Qiagen) with homogenization aided by a tissue-lyzer. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Midi kit (Qiagen), and included DNase treatment following standard manufacturers protocol. A total of 1 μg of RNA was converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) using the High-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) and diluted to 1:100. For qPCR, 2.5 μl of cDNA was mixed with 10 μl of PowerUp SYBR green (Applied Biosystems), 1.2 μl of primers (see Table S1 for primer sequences) at a concentration of 10 nM, and water to make up a total reaction volume of 20 μl. Gene expression was normalized using housekeeping genes β-actin and Rsp20. Reactions were performed using the StepOne-Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems), and relative mRNA expression calculated using the comparative CT method with the StepOne Software v2.3 (Applied Biosystems).

2.9 |. Placenta western blot

For analysis of glucose transporter protein expression, placenta tissue was homogenized in ice-cold RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors and protein concentrations determined using Pierce™ Coomassie Plus Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following standard protocol. A total of 40 μg of protein was then mixed with Nupage SDS Loading Buffer (Invitrogen) and Reducing Agent (Invitrogen) and denatured by heating at 95°C for 10 min. The lysates were then run on a 10% Tris-Bis precast gel (Invitrogen) following manufacturers protocols and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes using the Bolt Mini Electrophoresis unit (Invitrogen). A Prestain Protein ladder (PageRuler, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was included on the gels. Membranes were placed into 5% skim-milk in Tris-buffered Saline containing Tween 20 (TBS-T) and incubated overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies (Slc2A1: Abcam ab15309, 1:500 [0.5 μg/ml]; Slc2A3: Abcam ab15311, 1:200 [5 μg/ml]; Slc38A1: Abcam ab104684, 1:200 [5 μg/ml]). *Note: There were no suitable antibodies specific to guinea pig Slc38A2) were then applied for 1–2 h at room temperature, the membranes washed 3 times in fresh TBS-T, and then further incubated with a HRP conjugated secondary (Cell Signaling 7074S, 1:1000 [0.06 μg/ml]) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized by chemiluminescence using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on the Universal Imager (Bio-Rad). Signal intensity of the protein bands were calculated using Image Studio Lite (version 5.2, LI-COR) and normalized to β-actin.

Localization of Slc2A1 in the syncytiotrophoblast membranes was visualized using IHC as described in ISH for plasmid-specific mRNA section. Primary antibody for Slc2A1 (Abcam ab15309) was diluted 1:750 (0.3 μg/ml) and applied to sections overnight at 4°C, and biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Vector BA-1000, 1:200 [10 μg/ml]) also used as previously described.

2.10 |. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 26 software. Generalized estimating equations were used to determine differences between diet and nanoparticle treatment. Given the small sample size, all data was assumed to not be normally distributed and therefore, a Gamma with log link type of model was fitted. Dams were considered the subject, diet, nanoparticle treatment and fetal sex treated as main effects, and gestational age as a covariate. Litter size was also included as a covariate but removed as there was no significant effect for any of the outcomes. Statistical significance was considered at p ≤ 0.05. For statistically significant results, a Bonferroni post hoc analysis was performed. Results are reported as estimated marginal means ± 95% confidence interval.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Synthesis and characterization of PHPMA115-b-PDMAEMA115

The general schematic for the synthesis of the diblock copolymer is outlined in scheme S2 (Supporting Information Material). The molar ratio of CTA and 2,2′-azo-bis-isobutyrylnitrile (AIBN) was 10:1. 1H NMR spectra showed the presence of all characteristic peaks for PHPMA115-ECT (Figure S2). The PHPMA macro-CTA was then chain extended by RAFT (reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer) block polymerization of PDMAEMA to yield the final diblock copolymer PHPMA115-b-PDMAEMA115. The presence of all characteristic peaks for PHPMA and PDMAEMA in 1H NMR spectra confirmed successful diblock copolymer formation (Figure S2).

3.2 |. The nanoparticle is rapidly endocytosed in the guinea pig placenta but only the Cyp19a1 promotor is recognized

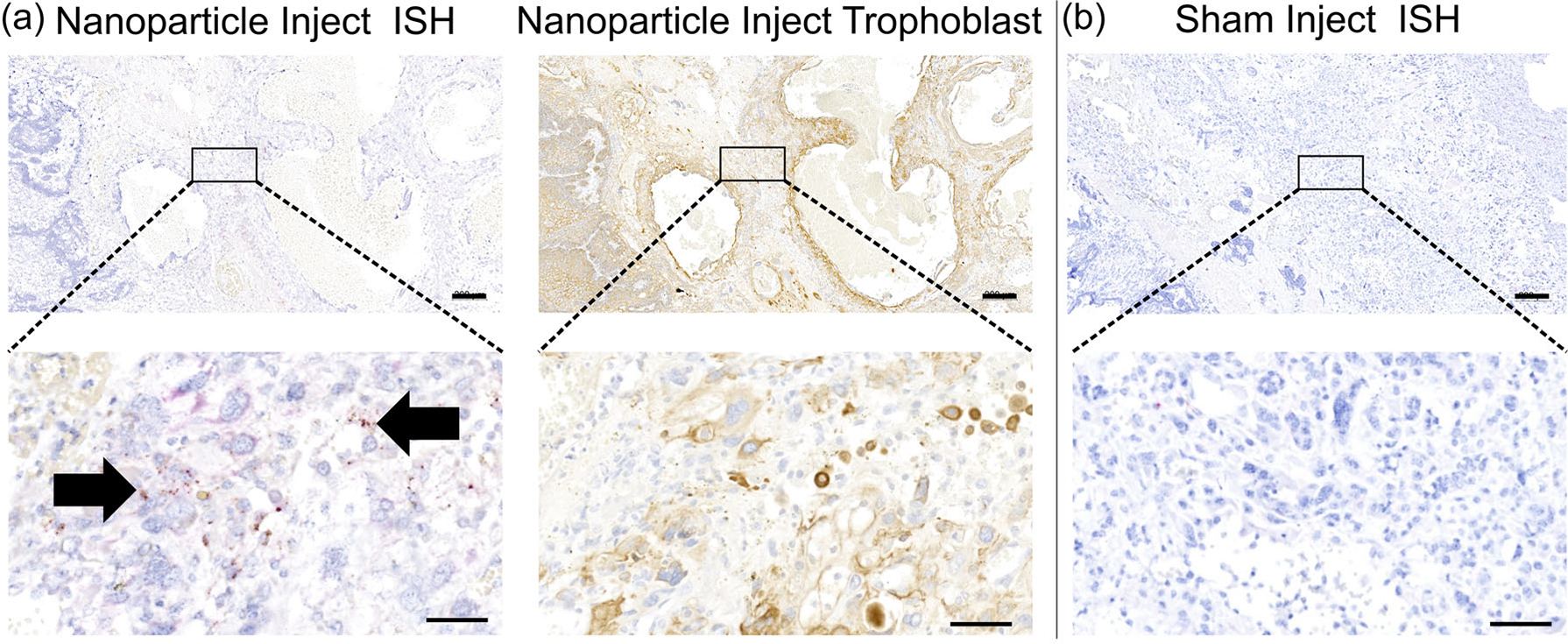

To confirm nanoparticle uptake and promotor recognition in the guinea pig placenta, a GFP plasmid was complexed with a Texas Red conjugated HPMA-DMAEMA co-polymer. Texas Red fluorescence was observed in the sub-placental/decidual region of the guinea pig placenta 30 h after treatment indicating the ability of nanoparticle to enter placental cells (Figure S3). However, GFP fluorescence was only observed in placental cells of tissue that received an inject of nanoparticle containing a plasmid with the Cyp19a1 promotor and not the Plac1 promotor (Figure S3). GFP fluorescence appeared to be localized in vesicles within the cytoplasm of cells. There was no Texas-red fluorescence observed in the fetal liver confirming the inability for the nanoparticle to enter fetal circulation. In mice, we have previously shown that maternal lung, ovary, liver and kidney are capable of nanoparticle uptake, with clearance from the maternal system by 96 h after injection (Fry et al., 2015). In this study, fluorescent analysis of maternal ovary and lung confirmed nanoparticle uptake 30 h after injection, however, there was no GFP transgene expression (Figure S4). Additionally, we have previously shown in mice placentas increased expression of hIGF1 following nanoparticle treatment using qPCR (Abd Ellah et al., 2015; R. L. Wilson et al., 2021c). Given the high degree of homology between human and guinea pig Igf1, human-specific, and therefore, nanoparticle specific, hIGF1 expression could not be determined. However, ISH analysis of placenta tissue receiving the Cyp19a1-hIGF1 nanoparticle 5 days after intraplacental injection, confirmed the presence of plasmid-specific mRNA in the trophoblasts of the sub-placenta/decidua region (Figure 1a). ISH in sham injected placentas showed no positive plasmid-specific mRNA expression, as expected (Figure 1b). Unlike in the mouse studies, in which untreated placentas in the opposite uterine horn to treated placentas did not show increased hIGF1 expression (Abd Ellah et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2021c), in the guinea pigs, plasmid-specific hIGF1 was not just confined to the placenta that received the intra-placental injection, but was found in all placentas of the litter (Figure S5). No positive plasmid-specific hIGF1 was found in the fetal liver further confirming the inability for plasmid to cross the placental barrier and enter fetal circulation after 5 days (Figure S6). Analysis of guinea pig Igf1 mRNA revealed no expression (amplification at CT > 37) in the guinea pig placenta labyrinth whilst sub-placenta/decidua expression of Igf1 was not altered by either diet or nanoparticle treatment (p > 0.05; Figure S7A). Igf1 protein, which is secreted and therefore not expected to be in the cytoplasm of cells, could not be detected in placenta tissue using IHC or Western Blot analyses (Figure S7B,C).

FIGURE 1.

Representative images of in situ hybridization (ISH) for plasmid-specific mRNA expression in the guinea pig placenta 5 days after intra-placental nanoparticle treatment. (a) ISH (first panel) confirmed plasmid-specific hIGF1 expression in the guinea pig sub-placenta/decidua 5 days after nanoparticle treatment. Serial sectioning and immunohistochemistry (second panel) confirmed plasmid-specific hIGF1 was localized to trophoblast cells. (b) Saline injected tissue was used as a negative control and no positive staining for plasmid-specific hIGF1 was observed. Representative images at low magnification (top row) and high magnification (bottom row). Arrows = the presence of red dots indicating plasmid-specific hIGF1. n = 2 sham dams and 4 nanoparticle dams. Scale bar top row = 200 μm, scale bar bottom row = 50 μm. hIGF1, human insulin-like growth factor 1; mRNA, messenger RNA

3.3 |. Short-term placenta hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment was not toxic to fetal development

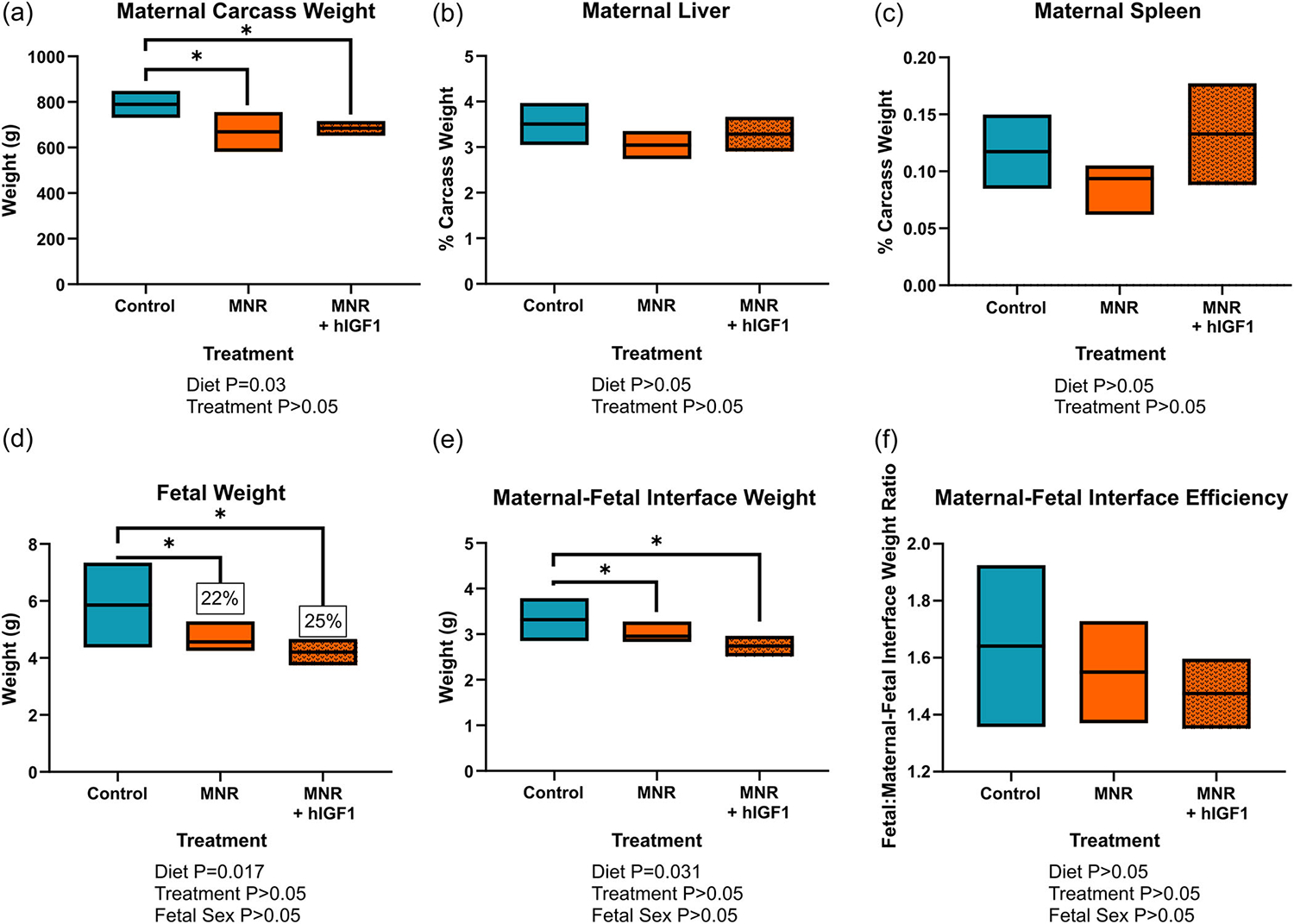

Only 1 dam (MNR, 3 viable fetuses and 1 resorption) was recorded as having a resorption. The resorption appeared as an amorphous, dark lump within the uterus indicative of early pregnancy loss not associated with hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment. Furthermore, there was no difference in litter size between the MNR dams compared to the control ad libitum fed dams (mean ± SEM: control = 3.2 ± 0.35 vs. MNR = 2.8 ± 0.24, p > 0.05). Maternal carcass weight (maternal weight minus fetal and maternal-fetal interface weight) was lower in MNR dams compared to control (p = 0.03, Figure 2a), but not different between MNR and MNR + hIGF1 treated (p > 0.05). There was also no difference in maternal liver and spleen weight as a percentage of carcass weight with either diet or hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment (Figure 2b,c, respectively). Fetal weight was approximately 22%–25% lower in the MNR females compared to the control ad libitum fed females (p = 0.017, Figure 2d). hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment did not change fetal weight of the restricted fetuses (p > 0.05), but this result is unsurprising given the relative short time period between treatment and sample collection. Furthermore, there was no significant effect of fetal sex on fetal weight, nor on any of the other outcomes measured. Maternal-fetal interface weight was lower between MNR and control dams (p = 0.031, Figure 2e), and not changed by hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment (p > 0.05). Maternal-fetal interface efficiency (fetal to maternal-fetal interface weight ratio) was not different between either diet or hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment (p > 0.05, Figure 2f).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of maternal nutrient restriction (MNR) diet and hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment on mid-pregnancy maternal, fetal and maternal-fetal interface weight. (a) At time of sacrifice, maternal carcass weight (maternal weight minus total fetal and maternal-fetal interface weight) was lower in the MNR group compared to control diet group. (b) Maternal liver weight as a percentage of carcass weight was not different with either diet or hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment. (c) Maternal spleen weight at a percentage of carcass weight was not different with either diet or hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment. (d) MNR resulted in approximately 22%–25% reduction in fetal weight at mid-pregnancy, and there was no effect of placental hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment in MNR fetuses. (e) MNR reduced maternal-fetal interface weight at mid-pregnancy, which was also not affected by hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment. (f) There was no difference in maternal-fetal interface efficiency (fetal to maternal-fetal interface weight ratio) with either MNR diet or hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment. Fetal sex was not a significant factor for any of the fetal/placental outcomes. n = 7 control dams (21 fetuses/placentas), 5 MNR dams (14 fetuses/placentas) and 7 MNR + hIGF1 dams (19 fetuses/placentas). Data are estimated marginal means ± 95% confidence interval. All p values calculated using generalized estimating equations with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. Asterix denote a significant difference of p ≤ 0.05. hIGF1, human insulin-like growth factor 1

3.4 |. hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment had no effect on gross placental morphology but reduced placental labyrinth interhaemal distance in the maternal nutrient restricted group

Analysis of mid-sagittal cross-sections of the maternal-fetal interface showed no signs of necrosis or gross placental defects with neither MNR nor hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment (Figure S8). There was also no difference in the sub-placenta/decidua area (p > 0.05; Figure S8A), placenta area (p > 0.05; Figure S8B), or total mid-sagittal area of the maternal-fetal interface (p > 0.05; Figure S8C), with either diet or hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment. Double-label IHC was used to identify placental labyrinth trophoblast and fetal capillaries (Figure S1). In the MNR placentas, trophoblast volume density was increased (p = 0.01, Figure 3a), but there was no difference in maternal blood space volume density (Figure 3b), or fetal capillary volume density (Figure 3c), when compared to control. In the MNR + hIGF1 treated placentas, trophoblast volume density was not different when compared to control (Figure 3a), but fetal capillary volume density was increased when compared to control and MNR (p = 0.004, Figure 3c). Most importantly, the interhaemal distance between maternal and fetal circulation was reduced in the MNR + hIGF1 treated placentas (p = 0.043, Figure 3d) indicating the possibility for greater oxygen diffusion.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of maternal nutrient restriction (MNR) diet and hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment on mid-pregnancy placenta microstructure. (a) Compared to control, trophoblast volume density was increased in the MNR placentas but not different in the MNR + hIGF1 placentas. (b). There was no change to the maternal blood space (MBS) volume density with either diet or hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment. (c) hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment of MNR placentas increased fetal capillary volume density compared to both control and MNR placentas. (d) There was a reduction in the interhaemal distance (distance between MBS and fetal circulation) in MNR + hIGF1 placentas compared to control and MNR placentas. There was no effect of fetal sex on any of the outcomes assessed. n = 7 control dams (21 placentas), 5 MNR dams (14 placentas) and 7 MNR + hIGF1 dams (19 placentas). Data are estimated marginal means ± 95% confidence interval. All p values calculated using generalized estimating equations with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. Asterix denote a significant difference of p ≤ 0.05. hIGF1, human insulin-like growth factor 1

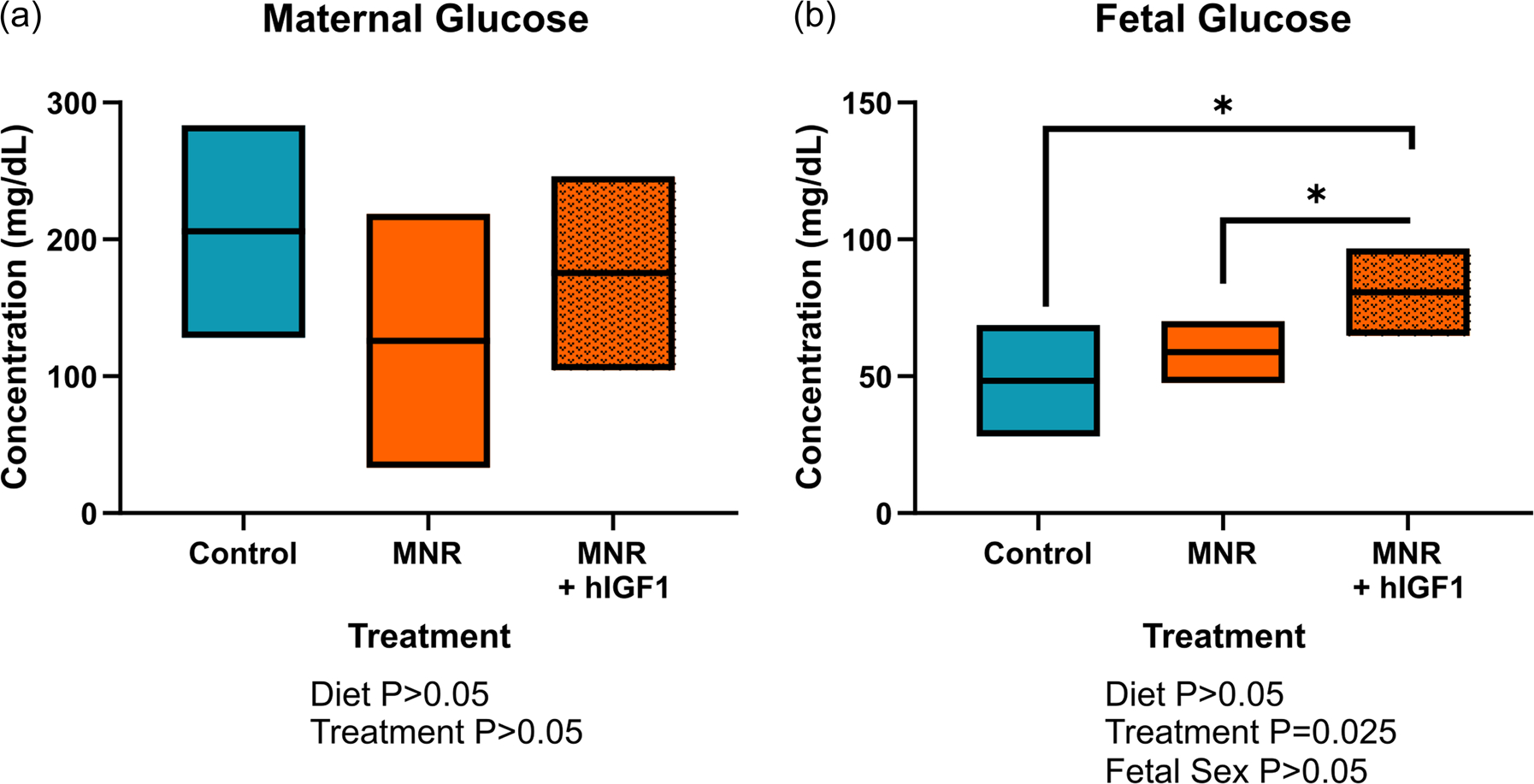

3.5 |. Placenta hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment increased fetal glucose concentrations and placenta expression of glucose and amino acid transporters

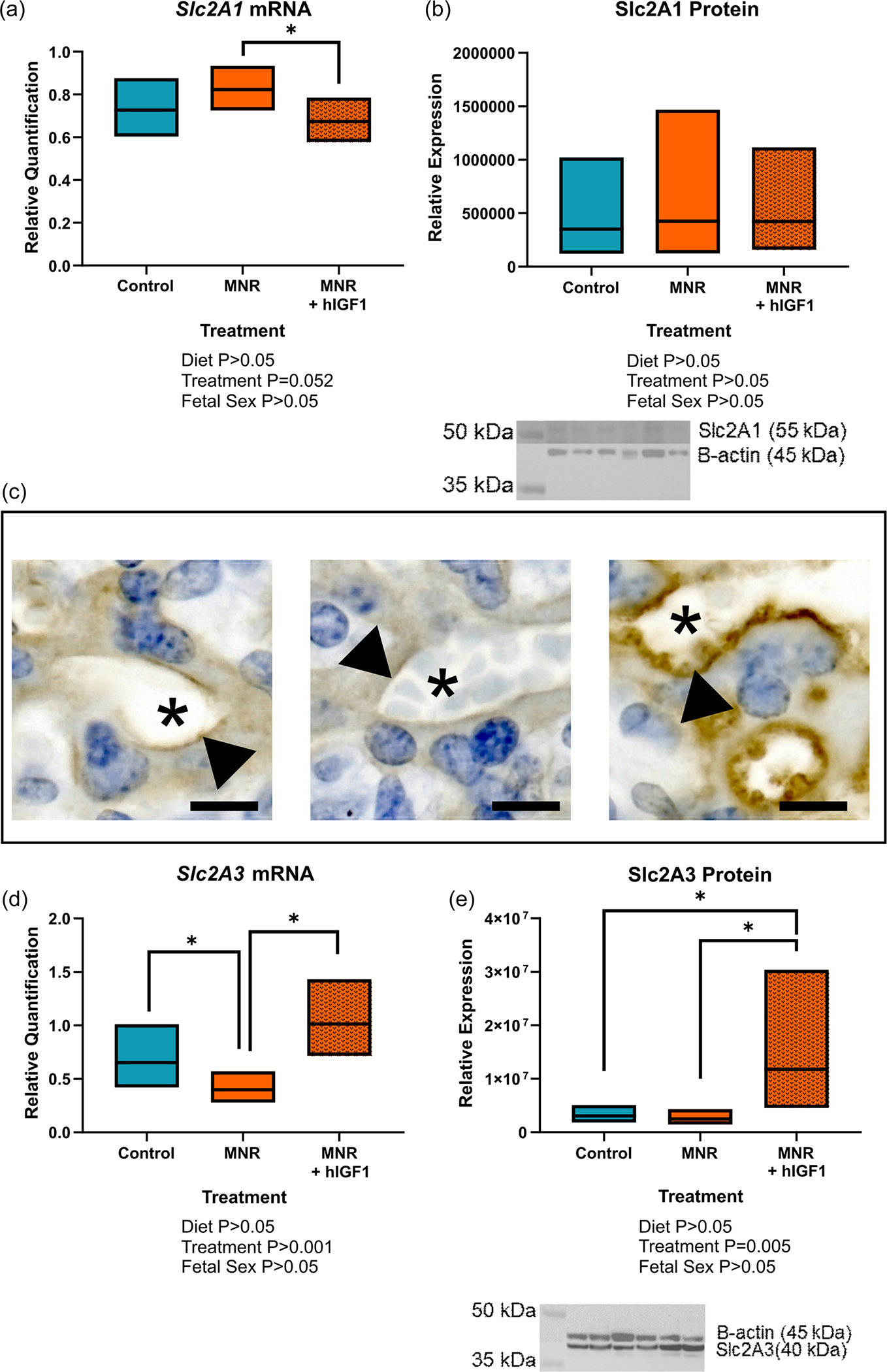

There was no difference in maternal glucose concentrations between control and MNR diet dams at time of post mortem (Figure 4a). Despite no difference in fetal weight with hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment, glucose concentrations were increased in the MNR + hIGF1 fetuses compared to control and MNR fetuses (p = 0.025, Figure 4b). In MNR placentas, mRNA expression of glucose transporters Slc2A1 was not different compared to control (Figure 5a), however, there was a reduction in expression levels between MNR + hIGF1 placentas and MNR (p = 0.049, Figure 5a). Western blot analysis of Slc2A1 protein expression showed no difference in global expression levels (Figure 5b), however immunohistochemical staining for Slc2A1 showed relocalization of Slc2A1 to the apical membrane of the syncytium in the MNR + hIGF1 treated placentas (Figure 5c). Expression of Slc2A3 was reduced in MNR placentas compared to control (p = 0.011, Figure 5d), but increased in MNR + hIGF1 treated placentas compared to restricted sham and comparable to control levels (p = 0.002, Figure 5d). There was also increased protein expression of Slc2A3 in the MNR + hIGF1 treated placentas compared to both control and MNR (p = 0.005, Figure 5d).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of maternal nutrient restriction (MNR) diet and hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment on maternal and fetal blood glucose concentrations. (a) There was no difference in maternal blood glucose concentrations at mid pregnancy with either diet or hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment. (b) Glucose concentrations were increased in MNR + hIGF1 fetuses compared to control and MNR fetuses. n = 6 control dams (14 fetuses), 5 MNR dams (10 fetuses) and 7 MNR + hIGF1 dams (17 fetuses). Data are estimated marginal means ± 95% confidence interval. All p values calculated using generalized estimating equations with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. Asterix denote a significant difference of p ≤ 0.05. hIGF1, human insulin-like growth factor 1

FIGURE 5.

Effect of maternal nutrient restriction (MNR) diet and hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment on placental glucose transporter expression. (a) mRNA expression of Slc2A1 was reduced in MNR + hIGF1 placentas compared to MNR, but not different to control. (b) There was no difference in protein expression of Slc2A1 in control, MNR or MNR + hIGF1 placentas. Representative western blot: lanes 1 and 2 = control, lanes 3 and 4 = MNR, lanes 5 and 6 = MNR+ hIGF1. (c) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for Slc2A1 showing relocalization of Slc2A1 to the apical membrane of the placental syncytium (arrow head). Image 1 = control, image 2 = MNR, image 3 = MNR + hIGF1. Asterix represents maternal blood space. (d) mRNA expression of Slc2A3 was reduced in MNR placentas compared to control, but increased back to normal levels in MNR + hIGF1 placentas. (e) There was also increased protein expression of Slc2A3 in MNR + hIGF1 placentas compared to control and MNR. Representative western blot: lanes 1 and 2 = control, lanes 3 and 4 = MNR, lanes 5 and 6 = MNR + hIGF1. n = 6 control dams (14 fetuses), 5 MNR dams (10 fetuses) and 7 MNR + hIGF1 dams (17 fetuses). Data are estimated marginal means ± 95% confidence interval. All p values calculated using generalized estimating equations with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. Asterix denote a significant difference of p ≤ 0.05. hIGF1, human insulin-like growth factor 1

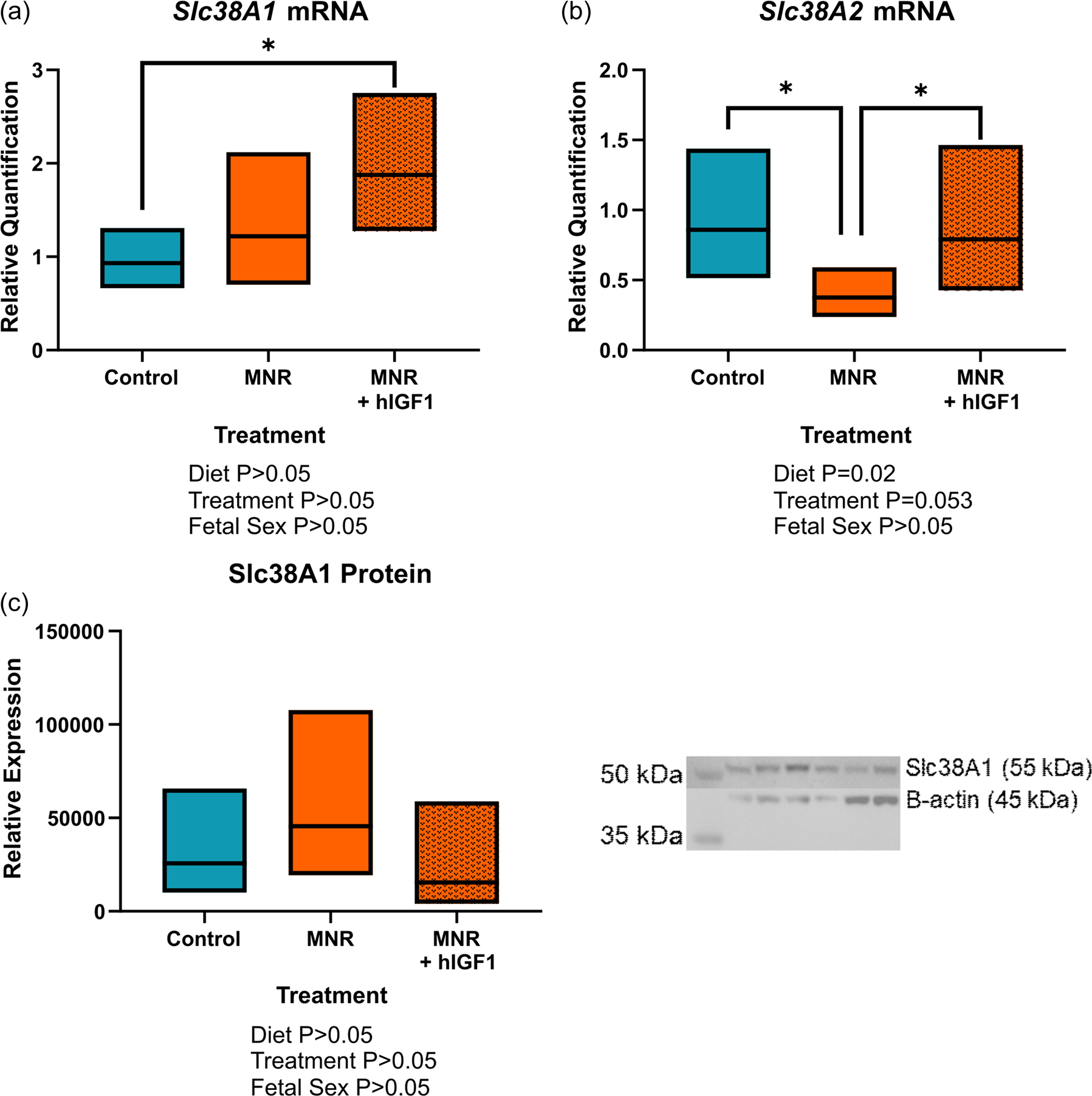

mRNA and protein expression of amino acid transporters Slc38A1 and Slc38A2 was also assessed in the placenta (Figure 6). Placenta mRNA expression Slc38A1 was not different between MNR and control placentas, but increased in MNR + hIGF1 treated placentas compared to control (p = 0.016, Figure 6a). For Slc38A2, expression was reduced in MNR placentas compared to control (p = 0.048, Figure 6b), but increased to normal levels in the MNR + hIGF1 treated placentas (p = 0.011, Figure 6b). Despite changes in gene expression, western blot analysis showed no changes to protein expression of Slc38A1 (Figure 6c), and antibodies that cross-reacted with guinea pig Slc38A2 could not be obtained.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of maternal nutrient restriction (MNR) diet and hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment placenta amino acid transporter mRNA and protein expression. (a) mRNA expression of Slc38A1 was increased in MNR + hIGF1 placentas compared to control. (b) mRNA expression of Slc38A2 was reduced in MNR placentas compared to control, but increased to normal levels in the MNR + hIGF1 placentas. (c) There was no difference in protein expression of Slc38A1 between the groups. Representative western blot: lanes 1 and 2 = control, lanes 3 and 4 = MNR, lanes 5 and 6 = MNR + hIGF1. n = 6 control dams (14 placentas), 5 MNR dams (10 placentas) and 7 MNR + hIGF1 dams (17 placentas). Data are estimated marginal means ± 95% confidence interval. All p values calculated using generalized estimating equations with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. Asterix letters denote a significant difference of p ≤ 0.05. hIGF1, human insulin-like growth factor 1

4 |. DISCUSSION

In the present study, we show efficient nanoparticle uptake in the mid-pregnancy guinea pig placenta and sustained transgene expression of hIGF1 in sub-placenta/decidua trophoblast cells 5 days after treatment. hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment was not toxic to pregnant dams as there was no difference in maternal weight or organ coefficients with treatment. Similarly, hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment was not toxic to fetuses as no nonviable fetuses, that would have been lost due to treatment, were recorded at post mortems. Fetal weight was not lowered by treatment, and morphological assessment of the placenta did not show indicators of gross morphological defects. hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment did however, increase fetal capillary volume density and reduce the interhaemal distance between maternal and fetal circulation in the MNR placenta, and increase fetal blood glucose concentrations by 37%–66%. Additionally, there was changes in the expression of major glucose and amino acid transporters in the placenta. Such changes occurred within a short 5-day time period, and indicates the potential for hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment to have a positive effect on fetal growth with a longer duration of treatment.

The importance of IGF1 in placental development and function is well established. Through binding with the IGF1 receptor, it signals to increase nutrient transport across the placenta as well as modulates placental vascular development (Fowden, 2003). In the current study, hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment did not result in significant changes to fetal weight, nor gross placental morphology. However, given that the guinea pig pregnancy is 65–70 days, the lack of significant change to fetal weight is likely explained by the short time period between treatment and collection of samples. hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment was however, capable of increasing fetal capillary volume density. Angiogenesis is an essential component of placenta growth and development and IGF1 is known to influence placental angiogenesis across gestation (Hiden et al., 2009). Furthermore, we have previously shown in the surgical ligated mouse model of FGR, increased hIGF1 expression increases the number of fetal vessels in the placenta (Abd Ellah et al., 2015). Additionally, hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment reduced the placental interhaemal distance between the maternal blood space and fetal circulation. In human term placentas, IGF1 treatment has been shown to inhibit the release of vasoconstrictors thromboxane B2 and prostaglandin F2α, indicating the ability for IGF1 to enhance placental vasodilation and allow for increased blood supply to the placenta (Siler-Khodr et al., 1995). Thus, it is possible a similar mechanism is being activated in the current study, resulting in reduced interhaemal distance worth further investigation.

Glucose is an essential nutrient and energy source for the fetus, predominantly obtained from the mother (Illsley, 2000). Thus, adequate placental transfer of glucose from maternal circulation to fetal circulation is paramount to supporting appropriate fetal growth. In the present study, direct placental hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment resulted in increased fetal glucose concentrations 5 days after administration indicating the ability to rapidly enhance placental glucose transport to the fetus within a short period of time. We have previously shown that increased hIGF1 expression in the placenta increased glucose transporter expression, either at the mRNA or protein level, in mice and human in vitro models (Jones et al., 2013; R. L. Wilson et al., 2020). Furthermore, we have shown distinct relocalization of SLC2A1 to the apical membrane of the syncytiotrophoblasts in human placenta explants treated with hIGF1 nanoparticle (R. L. Wilson et al., 2020); which has happened again with hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment in the guinea pig placenta. MNR + hIGF1 treated placentas also had increased expression of Slc2A3 in both mRNA and protein. Human placental expression of SLC2A3 is highest in first trimester (Brown et al., 2011), and is thought to function as a rapid, high volume glucose transporter under conditions where extracellular glucose is lower (Simpson et al., 2008), like in the first trimester when the placenta is absent of a fully formed maternal circulatory system. Altogether, these results provide a snapshot of how increased placental expression of hIGF1 may positively influence glucose transporter expression to enable rapid glucose uptake to the fetus.

In the placenta, amino acid transport is predominantly supported by the system A and L transporters (Dumolt et al., 2021). System A transporters include Slc38A1 and Slc38A2, which are sodium-dependent (Rosario et al., 2016). In humans, reduced placental amino acid transport has been associated with downregulation of Slc38A2 expression in FGR (Mandò et al., 2013). The present study supports this finding, as there was a reduction in mRNA expression of Slc38A2 in the MNR placentas compared to control. More importantly, hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment of the MNR placentas returned expression levels of Slc38A2 to normal, and increased mRNA expression of Slc38A1. We have consistently shown that increasing placental expression of hIGF1 impacts the expression of Slc38A1 and Slc38A2 in the human placenta trophoblast cell line—BeWo cells, and surgically ligated mice placentas (Jones et al., 2014). However in these studies, there was also change to protein expression, which in the case of Slc38A1 was not found in our study of guinea pig placentas. This outcome is again possibly due to the short time period in which hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment occurred. Never-the-less, our data indicates a positive effect on amino acid transporters with nanoparticle gene therapy likely to increase placental amino acid transport capacity under FGR conditions.

Development of an effective therapeutic to treat FGR during pregnancy is of high importance as FGR significantly contribute to the rates of stillbirth and miscarriage, and is also often associated with other fetal conditions, such as congenital heart defects (Leirgul et al., 2014). Additionally, FGR is strongly associated with the developmental programming of adult diseases (Barker & Osmond, 1986). However, the implementation of treatments for FGR is complicated by the need to ensure the health and safety of both mother and offspring. In our current study, we found no toxic effects of short-term nanoparticle gene therapy treatment on either mother or fetuses; there was no difference in maternal or fetal weigh between nanoparticle and sham treated. Furthermore, our polymer-based hIGF1 nanoparticle is designed to target the placenta which is discarded after birth, and represents the ideal site for an interventional therapy as there is no potentially long-term consequences to maternal health. Polymer-based systems have been shown to elicit less of an immune response and are safer than viral-based delivery systems (Andersen et al., 2008; Le Bon et al., 2002; Sharma et al., 2008), thus mitigating against concerns regarding immunogenicity and off-target affects (Ahi et al., 2011). Furthermore, a broad range of bioactive molecules including plasmids, siRNAs, mRNAs, proteins and oligonucleotides can be delivered with polymers (Alinejad et al., 2016; Duvall et al., 2010; Navarro et al., 2015; Teo et al., 2016) and as such, offers a promising platform for continuing to develop targeted strategies to treat the placenta and prevent FGR during pregnancy.

Our findings, that hIGF1 nanoparticle treatment results in rapid changes to glucose transporter expression and increases fetal glucose concentrations, highlights the huge translational potential this treatment could have in human pregnancies. However, in the present study, hIGF1 nanoparticle was injected directly to the placenta to maximize delivery and placental uptake. Clinically this method of delivery is suboptimal and therefore, future studies utilizing intravenous gene therapy delivery and enhancing the placental homing capabilities are required. Overall, despite no significant changes to fetal weight or growth trajectories, short-term treatment of growth restricted placentas with the hIGF1 nanoparticle resulted in increased fetal capillary volume density, reduced interhaemal distance and increased expression of glucose transporters associated with increased fetal glucose concentrations. Such outcomes indicate a potential positive effect on fetal growth worth investigating further with longer treatment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the staff of the Animal Facility Services at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center and University of Florida for their assistance. This study was funded by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) award R01HD090657 (HNJ).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/mrd.23644

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- Abd Ellah N, Taylor L, Troja W, Owens K, Ayres N, Pauletti G, & Jones H (2015). Development of non-viral, trophoblast-specific gene delivery for placental therapy. PLoS One, 10(10), e0140879. 10.1371/journal.pone.0140879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abd Ellah NH, Potter SJ, Taylor L, Ayres N, Elmahdy MM, Fetih GN, & Pauletti GM (2014). Safety and efficacy of amine-containing methacrylate polymers as nonviral gene delivery vectors. Journal of Pharmaceutical Technology & Drug Research, 3(2), 7243. [Google Scholar]

- Ahi YS, Bangari DS, & Mittal SK (2011). Adenoviral vector immunity: Its implications and circumvention strategies. Current Gene Therapy, 11(4), 307–320. 10.2174/156652311796150372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alinejad V, Hossein Somi M, Baradaran B, Akbarzadeh P, Atyabi F, Kazerooni H, Samadi Kafil H, Aghebati Maleki L, Siah Mansouri H, & Yousefi M (2016). Co-delivery of IL17RB siRNA and doxorubicin by chitosan-based nanoparticles for enhanced anticancer efficacy in breast cancer cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 83, 229–240. 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen MO, Howard KA, Paludan SR, Besenbacher F, & Kjems J (2008). Delivery of siRNA from lyophilized polymeric surfaces. Biomaterials, 29(4), 506–512. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamfo JE, & Odibo AO (2011). Diagnosis and management of fetal growth restriction. Journal of Pregnancy, 2011, 640715. 10.1155/2011/640715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamrungsap S, Zhao Z, Chen T, Wang L, Li C, Fu T, & Tan W (2012). Nanotechnology in therapeutics: A focus on nanoparticles as a drug delivery system. Nanomedicine (Lond), 7(8), 1253–1271. 10.2217/nnm.12.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, & Osmond C (1986). Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in England and Wales. Lancet, 1(8489), 1077–1081. 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91340-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein IM, Horbar JD, Badger GJ, Ohlsson A, & Golan A (2000). Morbidity and mortality among very-low-birth-weight neonates with intrauterine growth restriction. The Vermont Oxford Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 182(1 Pt 1), 198–206. 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70513-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bon B, Van Craynest N, Boussif O, & Vierling P (2002). Polycationic diblock and random polyethylene glycol- or tris(hydroxymethyl) methyl-grafted (co)telomers for gene transfer: Synthesis and evaluation of their in vitro transfection efficiency. Bioconjugate Chemistry, 13(6), 1292–1301. 10.1021/bc0255440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K, Heller DS, Zamudio S, & Illsley NP (2011). Glucose transporter 3 (GLUT3) protein expression in human placenta across gestation. Placenta, 32(12), 1041–1049. 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton GJ, & Fowden AL (2015). The placenta: A multifaceted, transient organ. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 370(1663), 20140066. 10.1098/rstb.2014.0066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispi F, Miranda J, & Gratacos E (2018). Long-term cardiovascular consequences of fetal growth restriction: Biology, clinical implications, and opportunities for prevention of adult disease. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 218(2S), S869–S879. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumolt JH, Powell TL, & Jansson T (2021). Placental function and the development of fetal overgrowth and fetal growth restriction. Obstetrics and Gynecology. Clinics, 48(2), 247–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall CL, Convertine AJ, Benoit DS, Hoffman AS, & Stayton PS (2010). Intracellular delivery of a proapoptotic peptide via conjugation to a RAFT synthesized endosomolytic polymer. Molecular Pharmaceutics, 7(2), 468–476. 10.1021/mp9002267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias AA, Ghaly A, Matushewski B, Regnault TR, & Richardson BS (2016). Maternal nutrient restriction in Guinea pigs as an animal model for inducing fetal growth restriction. Reproductive Sciences, 23(2), 219–227. 10.1177/1933719115602773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders AC, & Blankenship TN (1999). Comparative placental structure. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 38(1), 3–15. 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00003-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowden AL (2003). The insulin-like growth factors and feto-placental growth. Placenta, 24(8–9), 803–812. 10.1016/s0143-4004(03)00080-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry M, Troja W, & Jones H (2015). Localization and turnover of fluorescently-tagged nanoparticles for placental gene therapy in a mouse model of fetal growth restriction. Reproductive Sciences, 22, 188A. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly E, Hula N, Spaans F, Cooke CM, & Davidge ST (2020). Placenta-targeted treatment strategies: An opportunity to impact fetal development and improve offspring health later in ife.22 Pharmacological Research, 157, 104836. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiden U, Glitzner E, Hartmann M, & Desoye G (2009). Insulin and the IGF system in the human placenta of normal and diabetic pregnancies. Journal of Anatomy, 215(1), 60–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard J (1973). Corpus Luteum Function in Guinea Pigs, Hamsters, Rats, Mice and Rabbits1. Biology of Reproduction, 8(2), 203–221. 10.1093/biolreprod/8.2.203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Illsley N (2000). Current topic: Glucose transporters in the human placenta. Placenta, 21(1), 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones H, Crombleholme T, & Habli M (2014). Regulation of amino acid transporters by adenoviral-mediated human insulin-like growth factor-1 in a mouse model of placental insufficiency in vivo and the human trophoblast line BeWo in vitro. Placenta, 35(2), 132–138. 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HN, Crombleholme T, & Habli M (2013). Adenoviral-mediated placental gene transfer of IGF-1 corrects placental insufficiency via enhanced placental glucose transport mechanisms. PLoS One, 8(9), e74632. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HN, Powell TL, & Jansson T (2007). Regulation of placental nutrient transport—A review. placenta. Placenta, 28(8–9), 763–774. 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keswani SG, Balaji S, Katz AB, King A, Omar K, Habli M, Klanke C, & Crombleholme TM (2015). Intraplacental gene therapy with Ad-IGF-1 corrects naturally occurring rabbit model of intrauterine growth restriction. Human Gene Therapy, 26(3), 172–182. 10.1089/hum.2014.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BY, Rutka JT, & Chan WC (2010). Nanomedicine. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(25), 2434–2443. 10.1056/NEJMra0912273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkele J, & Trillmich F (1997). Are precocial young cheaper? Lactation energetics in the guinea pig. Physiological Zoology, 70(5), 589–596. 10.1086/515863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leirgul E, Fomina T, Brodwall K, Greve G, Holmstrøm H, Vollset SE, Tell GS, & Øyen N (2014). Birth prevalence of congenital heart defects in Norway 1994–2009—A nationwide study. American Heart Journal, 168(6), 956–964. 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner Y, Fattal-Valevski A, Geva R, Eshel R, Toledano-Alhadef H, Rotstein M, Bassan H, Radianu B, Bitchonsky O, Jaffa AJ, & Harel S (2007). Neurodevelopmental outcome of children with intrauterine growth retardation: A longitudinal, 10-year prospective study. Journal of Child Neurology, 22(5), 580–587. 10.1177/0883073807302605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandò C, Tabano S, Pileri P, Colapietro P, Marino MA, Avagliano L, Doi P, Bulfamante G, Miozzo M, & Cetin I (2013). SNAT2 expression and regulation in human growth-restricted placentas. Pediatric Research, 74(2), 104–110. 10.1038/pr.2013.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mess A (2007). The Guinea pig placenta: Model of placental growth dynamics. Placenta, 28(8–9), 812–815. 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JL, Botting KJ, Darby J, David AL, Dyson RM, Gatford KL, Gray C, Herrera EA, Hirst JJ, Kim B, Kind KL, Krause BJ, Matthews SG, Palliser HK, Regnault T, Richardson BS, Sasaki A, Thompson LP, & Berry MJ (2018). Guinea pig models for translation of the developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis into the clinic. Journal of Physiology, 596(23), 5535–5569. 10.1113/JP274948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro G, Pan J, & Torchilin VP (2015). Micelle-like nanoparticles as carriers for DNA and siRNA. Molecular Pharmaceutics, 12(2), 301–313. 10.1021/mp5007213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard N, Kaitu’u-Lino T. u, Harris L, Tong S, & Hannan N. (2020). Nanoparticles in pregnancy: The next frontier in reproductive therapeutics. Human Reproduction Update, 27(2), 280–304. 10.1093/humupd/dmaa049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnik R (2002). Intrauterine growth restriction. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 99(3), 490–496. 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01780-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CT, White CA, Wiemer NG, Ramsay A, & Robertson SA (2003). Altered placental development in interleukin-10 null mutant mice. Placenta, 24(Suppl A), S94–S99. 10.1053/plac.2002.0949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario FJ, Dimasuay KG, Kanai Y, Powell TL, & Jansson T (2016). Regulation of amino acid transporter trafficking by mTORC1 in primary human trophoblast cells is mediated by the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4–2. Clin Sci (Lond), 130(7), 499–512. 10.1042/CS20150554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sferruzzi-Perri AN, Owens JA, Pringle KG, Robinson JS, & Roberts CT (2006). Maternal Insulin-like growth factors-I and -II act via different pathways to promote fetal growth. Endocrinology, 147(7), 3344–3355. 10.1210/en.2005-1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sferruzzi-Perri AN, Sandovici I, Constancia M, & Fowden AL (2017). Placental phenotype and the insulin-like growth factors: Resource allocation to fetal growth. Journal of Physiology, 595(15), 5057–5093. 10.1113/JP273330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R, Lee JS, Bettencourt RC, Xiao C, Konieczny SF, & Won YY (2008). Effects of the incorporation of a hydrophobic middle block into a PEG-polycation diblock copolymer on the physicochemical and cell interaction properties of the polymer-DNA complexes. Biomacromolecules, 9(11), 3294–3307. 10.1021/bm800876v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siler-Khodr TM, Forman J, & Sorem KA (1995). Dose-related effect of IGF-I on placental prostanoid release. Prostaglandins, 49(1), 1–14. 10.1016/0090-6980(94)00001-d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson IA, Dwyer D, Malide D, Moley KH, Travis A, & Vannucci SJ (2008). The facilitative glucose transporter GLUT3: 20 years of distinction. American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism, 295(2), E242–E253. 10.1152/ajpendo.90388.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohlstrom A, Katsman A, Kind KL, Roberts CT, Owens PC, Robinson JS, & Owens JA (1998). Food restriction alters pregnancy-associated changes in IGF and IGFBP in the guinea pig. American Journal of Physiology, 274(3), E410–E416. 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.3.E410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo PY, Cheng W, Hedrick JL, & Yang YY (2016). Co-delivery of drugs and plasmid DNA for cancer therapy. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 98, 41–63. 10.1016/j.addr.2015.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RL, & Jones HN (2021a). Targeting the dysfunctional placenta to improve pregnancy outcomes based on lessons learned in cancer. Clinical Therapeutics, 43, 246–264. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RL, Owens K, Sumser EK, Fry MV, Stephens KK, Chuecos M, Carrillo M, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N, & Jones HN (2020). Nanoparticle mediated increased insulin-like growth factor 1 expression enhances human placenta syncytium function. Placenta, 93, 1–7. 10.1016/j.placenta.2020.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R, Lampe K, Matushewski BJ, Regnault TR, & Jones HN (2021). Time mating guinea pigs by monitoring changes to the vaginal membrane throughout the estrus cycle and with ultrasound confirmation. Methods and Protocols, 4, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RL, Stephens KK, Lampe K, & Jones HN (2021b). Sexual dimorphisms in brain gene expression in the growth-restricted guinea pig can be modulated with intra-placental therapy. Pediatric Research, 89, 1673–1680. 10.1038/s41390-021-01362-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RL, Troja W, Sumser EK, Maupin A, Lampe K, & Jones HN (2021c). Insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling in the placenta requires endothelial nitric oxide synthase to support trophoblast function and normal fetal growth. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 320(5), R653–R662. 10.1152/ajpregu.00250.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.