Abstract

Early positive subjective effects of cannabis predict the development of cannabis use disorder (CUD). Genetic factors, such as the presence of cytochrome P450 genetic variants that are associated with reduced Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) metabolism, may contribute to individual differences in subjective effects of cannabis. Young adults (N=54) with CUD or a non-CUD substance use disorder (control) provided a blood sample for DNA analysis and self-reported their early (i.e., effects upon initial uses) and past-year positive and negative subjective cannabis effects. Participants were classified as slow metabolizers if they had at least one CYP2C9 or CYP3A4 allele associated with reduced activity. Though the CUD group and control group did not differ in terms of metabolizer status, slow metabolizer status was more prevalent among females in the CUD group than females in the control group. Slow metabolizers reported greater past year negative THC effects compared to normal metabolizers; however, slow metabolizer status did not predict early subjective cannabis effects (positive or negative) or past year positive effects. Post-hoc analyses suggested males who were slow metabolizers reported more negative early subjective effects of cannabis than female slow metabolizers. Other sex-by-genotype interactions were not significant. These initial findings suggest that genetic variation in CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 may have sex-specific associations with cannabis-related outcomes. Slow metabolizer genes may serve as a risk factor for CUD for females independent of subjective effects. Male slow metabolizers may instead be particularly susceptible to the negative subjective effects of cannabis.

Keywords: cannabis use, subjective effects, cytochrome P450, cannabis metabolism, genetics

Graphical Abstract

1.1. Introduction

Cannabis use is prevalent among adolescents and young adults (Johnston et al., 2022; Palamar, Le, & Han, 2021), and approximately 1 in 5 people who use cannabis will develop a cannabis use disorder (CUD; Leung et al., 2020). Genetic factors and early subjective cannabis effects may be important for understanding progression to disorder. Twin studies have identified that both age of initiation and CUD are heritable (Lynskey et al., 2012; Verweij et al., 2010), and genetic factors partially account for overlap between initiation and disorder (Richmond-Rakerd et al., 2016). Refining our understanding of which genetic influences account for this overlap may allow us to better identify at-risk youth for targeted prevention and intervention.

Regarding subjective effects of cannabis, many positive and negative effects may occur following use. Positive effects include feeling relaxed and laughing easily (Davidson & Schenk, 1994; Green, Kavanagh, & Young, 2003; Tart, 1970). Negative effects include feeling paranoid, dizzy, or out of control (Davidson & Schenk, 1994; Green, Kavanagh, & Young, 2003; Tart, 1970). Reporting more positive early cannabis effects predicts use (Davidson & Schenk, 1994) and problems (Fergusson et al., 2003; Le Strat et al., 2009). Although most studies have not demonstrated positive links between negative cannabis effects and future use or problems (Daedelow et al., 2021; Davidson & Schenk, 1994; Fergusson et al., 2003), at least two have (Grant et al., 2005; Scherrer et al., 2009). A latent class analysis (LCA) found that males categorized as reactive (endorsing various positive and negative effects), adverse (experiencing mostly negative effects), and very reactive responders (experiencing virtually all effects) had higher odds of CUD than low responders (Grant et al., 2005). A second LCA found that high responders (those who experienced many positive and negative effects) had the highest frequency of use and prevalence of CUD (Scherrer et al., 2009). Thus, positive subjective cannabis effects are predictors of CUD susceptibility, but negative effects alone may not be enough to hinder development of problems, particularly if coupled with positive effects.

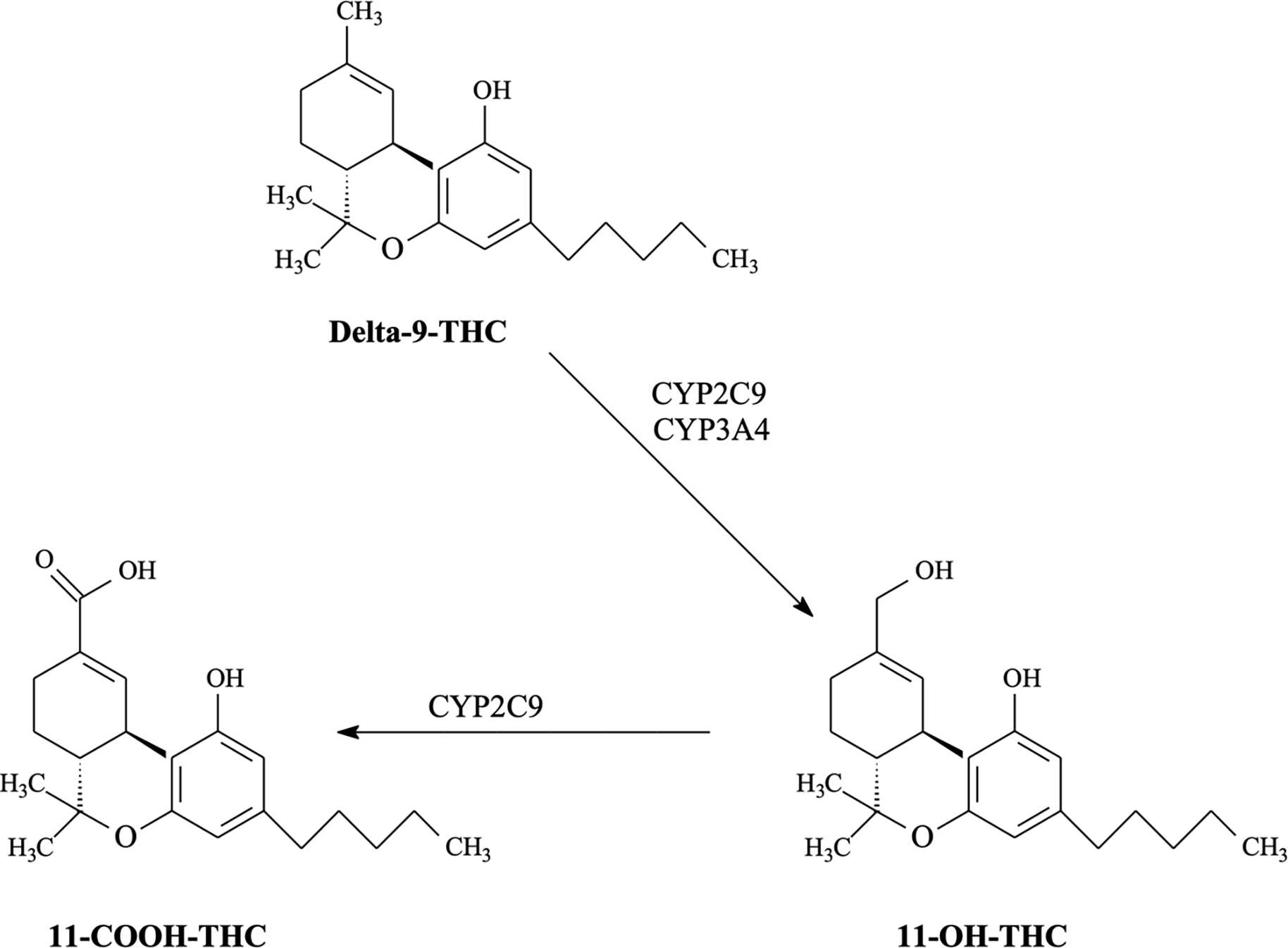

Given the role of subjective effects in predicting use and problems and the relevance of genetic factors to CUD, one promising avenue for research is examining genetic variants associated with differences in cannabis pharmacokinetics. Genetic variants associated with drug metabolism are important predictors of outcomes for alcohol (i.e., ADH1B; Justice et al., 2018; Li, Zhao, & Gelernter, 2011) and nicotine (i.e., CYP2A6; Jones et al., 2021; Malaiyandi, Sellers, & Tyndale, 2005). For cannabis, however, this has been less studied. Like many therapeutic and recreational substances, members of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family of enzymes mediate the metabolism of cannabis’s primary psychoactive component, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; Hryhorowicz et al., 2018; Zendulka et al., 2016). Two in particular (i.e., CYP2C9 and CYP3A4) encode for enzymes catalyzing THC metabolism (Hryhorowicz et al., 2018). CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 mediate the bioconversion of THC to the psychoactive metabolite 11-hydroxy-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (11-OH-THC), and CYP2C9 catalyzes the conversion of THC to an inactive metabolite, 11-Nor-9-carboxy-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (11-COOH-THC; see Figure 1). Most individuals have CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 genes that result in normal (i.e., wildtype) enzyme activity. However, genetic polymorphisms result in about 1 in 4 individuals exhibiting alleles that result in reduced enzyme activity (Zhou, Ingelman-Sundberg, & Lauschke, 2017). Decreased enzyme activity is associated with increased plasma THC levels following intravenous and oral administration of THC (Sachse-Seeboth et al., 2009; Wolowich et al., 2019). Because decreased enzyme activity leads to slower conversion of THC to other metabolites, effects may be prolonged and more pronounced for slow metabolizers. Higher THC levels produce greater ratings of drug liking, “good effect”, and “take again”, even though they also produce greater impairment (Fogel et al., 2017; Zamarripa et al., 2023). Stronger drug effects could promote subsequent use and increased risk for CUD, as higher levels of THC are associated with more rapid progression to symptom onset (Arterberry et al., 2019). However, no studies have examined associations between CYP genotypes and early subjective cannabis effects or CUD.

Figure 1.

Role of CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 enzymes in THC metabolism.

This study examined whether differences in genetic variants associated with THC metabolism were associated with subjective cannabis effects and CUD among young adults. We hypothesized that slow metabolizers (i.e., individuals with CYP2C9 alleles [e.g., *2, *3, *8, *11] and CYP3A4 alleles [e.g., *18, *22]) would report greater positive subjective effects and higher rates of CUD than those with normal CYP enzyme activity. Additionally, we hypothesized that slow metabolizers who reported earlier cannabis use would be more likely to develop CUD than normal metabolizers who engaged in earlier use.

1.2. Materials and Methods

1.2.1. Participants

Participants were 54 young adults aged 18–25 (M = 21.43, SD = 2.01) from the southeastern United States who reported using cannabis at least three times in the past year. Participants were classified into either: (1) those with CUD, including individuals with comorbid substance use disorders (SUDs) or (2) a control group who did not meet criteria for CUD but had another SUD instead. These groups were chosen to control for risk factors (including genetics) that are shared across SUDs (Young et al., 2006). Participants with significant or acutely unstable medical or psychiatric problems were excluded. Of participants with CUD, 34.21% had mild, 23.68% had moderate, and 42.11% had severe CUD. A little over half the sample (59.26%) was assigned female at birth1. Regarding race, 79.62% (n=43) of the sample identified as White, 7.41% (n=4) as Asian/Asian American, 5.56% (n=3) as Black/African American, and 7.41% (n=4) as another race. Table 1 provides additional sample characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N=54).

| Variable | % (N) or Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CUD Group | Control Groupa | Test of differences | |

| Age | 21.23 (1.82) | 21.90 (2.39) | t(52) = 1.14, p = 0.26 |

| Sex assigned at birth | χ2(1) = 4.45, p = 0.03 | ||

| Female | 68.42% (26) | 37.50% (6) | |

| Male | 31.58% (12) | 62.50% (10) | |

| Gender identity | χ2(1) = 3.72, p = 0.05 | ||

| Woman | 55.26% (21) | 37.50% (6) | |

| Man | 31.58% (12) | 62.50% (10) | |

| Nonbinary/Transgender | 9.26% (5) | 0.00% (0) | |

| Race | χ2(1) = 2.67, p = 0.10 | ||

| White | 73.68% (28) | 93.75% (15) | |

| Black/African American | 7.89% (3) | 0.00% (0) | |

| Asian/Asian American | 7.89% (3) | 6.25% (1) | |

| Other race | 10.53% (4) | 0.00% (0) | |

| Ethnicity | χ2(1) = 0.30, p = 0.59 | ||

| Non-Hispanic/Latinx | 81.58% (31) | 87.50% (14) | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 18.42% (7) | 12.50% (2) | |

| Metabolizer status | χ2(1) = 0.73, p = 0.39 | ||

| Slow metabolizer | 36.84% (14) | 25.00% (4) | |

| Normal metabolizer | 63.16% (24) | 75.00% (12) | |

| Highest education | χ2(5) = 5.12, p = 0.40 | ||

| Less than high school diploma | 2.63% (1) | 6.25% (1) | |

| High school graduate | 18.42% (7) | 12.50% (2) | |

| Some college | 55.26% (21) | 43.75% (7) | |

| Associate’s/technical degree | 2.63% (1) | 12.50% (2) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 21.05% (8) | 18.75% (3) | |

| Post-graduate education | 0.00% (0) | 6.25% (1) | |

| Age of first cannabis use | 16.57 (2.03) | 16.78 (2.68) | t(52) = 0.31, p = 0.76 |

| Age of first regular use | 18.03 (1.65) | 17.47 (2.61) | t(41) = −0.77, p = 0.44 |

| Positive early cannabis effects | 5.63 (1.53) | 3.19 (1.83) | t(52) = −5.05, p < 0.0001 |

| Negative early cannabis effects | 4.11 (2.56) | 4.31 (2.39) | t(51) = 0.27, p = 0.79 |

| Total early cannabis effects | 9.84 (3.07) | 7.5 (2.58) | t(51) = −2.66, p = 0.01 |

| Positive recent cannabis effects | 5.39 (1.59) | 3.25 (2.24) | t(52) = −4.00, p = 0.0002 |

| Negative recent cannabis effects | 2.76 (2.28) | 2.38 (2.06) | t(51) = −0.58, p = 0.57 |

| Total recent cannabis effects | 8.14 (2.71) | 5.63 (2.60) | t(51) = −3.13, p = 0.003 |

| Past-year alcohol use disorder | 36.84% (14) | 75.00% (12) | χ2(1) = 6.77 p = 0.01 |

| Past-year nicotine use disorder | 40.54 (15) | 50.00% (8) | χ2(1) = 0.41, p = 0.52 |

| Past 60-day use of cannabis | 100% (38) | 42.75% (7) | χ2(1) = 26.73, p < 0.0001 |

| Drug screen positive for cannabis | 76.32% (29) | 12.50% (2) | χ2(1) = 20.01, p < 0.0001 |

Control group consists of participants who have a non-CUD substance use disorder.

1.2.2. Procedure

Select Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) studies focused on: 1) adolescent/young adult substance use or 2) cannabis use across the lifespan participate in a shared screening protocol known as Entryway. This Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocol enrolls individuals aged 12 and older who report using substances. Participants undergo a screening assessment (Lab Visit #1 in Figure 2), including a structured diagnostic interview to assess CUD, urine sample collection to determine the presence or absence of a cannabinoid metabolite, and a substance use history interview, among other assessments. Eligibility criteria for studies are concurrently assessed, and participants provide informed consent to sharing their data with the study or studies in which they choose to enroll. Concurrently screening for multiple studies ensures a rigorous approach that reduces incentives for “guessing” eligibility criteria and modifying responses to ensure eligibility (Devine et al., 2021; Devine et al., 2013), while also safeguarding against participants enrolling in multiple studies (Devine et al., 2013) for which dual enrollment could present a safety concern or confound. Finally, Entryway prioritizes use of PhenX Toolkit measures (Conway et al., 2014) to promote data harmonization.

Figure 2.

Study procedure.

Note: A subset of participants completed four days of intensive longitudinal monitoring of cannabis use via their smart phone, but these data are not analyzed here. Lab Visits 1 and 2 could be completed on the same day if the participant and lab schedule permitted and they did not engage in intensive longitudinal monitoring.

Entryway participants who met criteria for the current study and agreed to participate signed a consent form detailing its procedures and completed additional questionnaires and a compensated blood draw (Lab Visit #2). A sub-sample of participants with CUD completed four days of intensive longitudinal monitoring of cannabis use on their mobile phones (not analyzed here). This study was conducted between April 2021-July 2022. During this time, 158 people participated in Entryway who were potentially eligible for the current study. Participation may or may not have been offered depending on participants’ preferences and other study enrollment needs.

Genotyping was performed according to the TaqMan method (Shen, Abdullah, & Wang, 2009). For each sample, 10 μl reaction volume was used in a 396-Wellplate containing 5 μl TaqMan Genotyping Mastermix (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, U.S.), 0.25 μl TaqMan SNP genotyping assay mix (20x) (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, U.S.), 2.75 μl DNA-free water (PreAnalytiX GmbH, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland) and 2 μl sample with a DNA concentration of 12 ng/μl. After samples were briefly vortex-mixed and centrifuged (2 min, 2000 rpm), PCR was performed in a Veriti® 384-well thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, U.S.). Reactions for CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, and CYP3A4*22 were incubated through 1 cycle of 95°C for 10 minutes, 45 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, and then 58°C for one minute. Reactions for CYP2C9*8, CYP2C9*11, and CYP3A4*18 were incubated through 1 cycle of 95°C for 10 minutes, 50 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, and then 58°C for one minute. Results were measured using QuantStudio 12K Flex (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, U.S.). The call rate for all SNPs was >99%.

1.2.3. Measures

Subjective effects of cannabis.

The Lyons Questionnaire (Lyons et al., 1997) was used to assess 8 positive (e.g., energetic, creative, and euphoric) and 15 negative (e.g., confused, paranoid, and anxious) subjective cannabis effects. Participants completed this questionnaire twice to assess initial and recent cannabis effects. Participants were either asked to think about the first few or the most recent times they had used cannabis and report whether they felt each effect shortly after use. Sum scores for positive and negative effects were totaled. One item from the measure included positive and negative effects (i.e., laughing or crying), but was included on the positive effects subscale after examining its correlation with other positive (r = 0.28) and negative (r = 0.02) items and comparing Cronbach’s alpha for the two subscales with and without the ambiguous variable. For early effects, the reliability was 0.67 for the positive subscale and 0.64 for the negative subscale. For recent effects, reliabilities were 0.69 and 0.67, respectively.

Age of first cannabis use.

Participants reported the age at which they first tried cannabis. The average age of onset was 16.64 (SD = 2.22, range from 12 to 25) and did not significantly differ for the CUD and control groups (Table 1).

Substance use disorders.

Diagnostic criteria for alcohol and cannabis use disorders were assessed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) using the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998). Tobacco/nicotine use disorder was assessed using the Penn State Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index (Foulds et al., 2015) and the modified version of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (Prokhorov et al., 1996). If scores on either indicated probable dependence, participants were classified as having a tobacco/nicotine use disorder (43.40%, n = 23).

Recent cannabis use.

Participants provided a urine sample in the Premier Bio-Cup (Premier Biotech), which included a test strip for detecting a THC metabolite, and 57.41% (n=31) of participants provided samples that were presumed positive for THC.

Slow vs. normal metabolizers.

Slow metabolizers were individuals who had at least one CYP2C9 allele (e.g., *2,*3,*8,*11) or CYP3A4 allele (e.g., *18,*22) associated with reduced enzyme activity (Zhou, Ingelman-Sundberg, & Lauschke, 2017). Of participants, 33.33% (n = 18) were slow metabolizers. White and non-White participants did not differ in prevalence of slow metabolizers (t(52) = −1.75, p = 0.09), nor did females and males (37.5% vs. 27.27%, respectively; t(52) = −0.77, p = 0.44).

1.2.4. Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS Studio version 3.8 (SAS Institute Inc., 2018). Correlations between study variables were examined first (Table 2). Next, we fit logistic regression models to examine the association between early cannabis subjective effects and CUD. Poisson regression analyses were conducted predicting the number of positive/negative early subjective effects of cannabis by CYP metabolizer status. We hypothesized that slow metabolizers would report greater positive subjective effects but not necessarily fewer negative effects during early use, reflecting their more pronounced responding to cannabis. The effect of metabolizer status on recent cannabis effects was also evaluated. Next, we examined whether metabolizer status predicted CUD using a logistic regression, hypothesizing that slow metabolizers would be more likely than normal metabolizers to develop CUD because of increased liking promoted by greater subjective effects. Finally, we tested whether metabolizer status moderated the association between age of first cannabis use and CUD. Sex was included as a covariate in all analyses due to potential differences in THC metabolism (Calakos et al., 2017) and subjective effects (Zamarripa, Vandrey, & Spindle, 2022). We also included race as a covariate given differences in allele frequencies across ancestry groups (Zhou, Ingelman-Sundberg, & Lauschke, 2017); however, we acknowledge that race is not always a proxy for genetic ancestry (Krainc & Fuentes, 2022). Considering this limitation, we performed sensitivity analyses removing race as a covariate. Finally, we conducted a set of post-hoc, exploratory analyses testing whether sex and metabolizer status interacted to impact subjective positive and negative cannabis effects.

Table 2.

Correlations among study variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age of first cannabis use | - | |||||||

| 2. Slow metabolizer | 0.21 | - | ||||||

| 3. Past year CUD | −0.22 | −0.06 | - | |||||

| 4. Past year AUD | 0.18 | 0.03 | −0.43 | - | ||||

| 5. Past year NUD | −0.14 | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.06 | - | |||

| 6. No. of early positive subjective effects | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.47 | −0.14 | −0.12 | - | ||

| 7. No. of early negative subjective effects | 0.17 | 0.02 | −0.17 | 0.17 | 0.08 | −0.03 | - | |

| 8. No. of recent positive subjective effects | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.49 | −0.11 | −0.05 | 0.76 | 0.02 | - |

| 9. No. of recent negative subjective effects | 0.01 | 0.22 | −0.05 | 0.25 | −0.10 | 0.11 | 0.61 | −0.07 |

Note: CUD = cannabis use disorder, AUD = alcohol use disorder, NUD = nicotine use disorder. Bold indicates significance at p < 0.05. CUD and AUD are negatively correlated as a function of study design (inclusion of a non-CUD substance use disorder control group).

1.3. Results

The most common early positive effects were feeling relaxed (94.44%), laughing or crying (83.33%), feeling creative (68.52%), sociable (61.11%), euphoric (59.26%), and confident (59.26%). The most common early negative effects were being lazy (66.04%), feeling drowsy (62.26%), and difficulty concentrating (51.85%). After recent cannabis use, almost all positive effects were endorsed by at least half the sample, except feeling energetic (27.78%) and having an increased sex drive (38.89%). Only two negative subjective effects occurred for more than half the sample recently: being lazy (53.70%) and feeling drowsy (59.26%). Each additional early positive subjective effect of cannabis experienced was associated with almost three times the odds of developing CUD (OR = 2.86 [1.53 – 5.35]). Early negative effects were not significantly related to CUD (OR = 0.93 [0.64 – 1.36]).

Metabolizer status was not a significant predictor of positive (β = −0.07, SE = 0.14, p = 0.61) or negative (β = −0.06, SE = 0.15, p = 0.69) early subjective effects of cannabis. Covariates were also not significantly associated with early effects. Metabolizer status was not associated with recent positive subjective effects (β = 0.00, SE = 0.14, p = 0.98) but was significantly associated with recent negative effects (β = −0.49, SE = 0.18, p = 0.007), such that normal metabolizers experienced fewer recent negative effects than slow metabolizers. Sex and race were not significantly associated with recent subjective effects. Metabolizer status did not predict CUD (OR = 0.47 [0.11 – 1.91]), and the interaction between metabolizer status and age of initiation predicting CUD was also not significant (β = 0.07, SE = 0.15, p = 0.67). However, all female slow metabolizers had CUD, while only 33.33% of male slow metabolizers did (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.005; Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of CYP genotypes by group and sex.

| Full Sample (N=54) | Males (n=22) | Females (n=32) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP3A4 | CUD | Control SUD | CUD | Control SUD | CUD | Control SUD |

| *1/*1 | 89.47% (34) | 100% (16) | 100% (13) | 100% (9) | 84.00% (21) | 100% (7) |

| *1/*18 | 2.63% (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.00% (1) | 0 |

| *1/*22 | 7.89% (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.00% (3) | 0 |

| CYP2C9 | ||||||

| *1/*1 | 71.05% (27) | 75% (12) | 84.62% (11) | 55.56% (5) | 64.00% (16) | 100% (7) |

| *1/*2 | 23.68% (9) | 12.50% (2) | 7.69% (1) | 22.22% (2) | 32.00% (8) | 0 |

| *2/*2 | 0 | 6.25% (1) | 0 | 11.11% (1) | 0 | 0 |

| *3/*1 | 5.26% (2) | 0 | 7.69% (1) | 0 | 4.00% (1) | 0 |

| *3/*2 | 0 | 6.25% (1) | 0 | 11.11% (1) | 0 | 0 |

Note: CUD = cannabis use disorder, Control SUD = control group with a non-CUD substance use disorder. For each gene assessed, proportions sum to 100%.

Given that a higher proportion of females in the CUD group were slow metabolizers compared to the control group (48% vs. 0%; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.03), we conducted post-hoc analyses to explore whether sex and metabolizer status interacted to impact subjective cannabis effects. There was no evidence for a significant sex*metabolizer status interaction (β = 0.03, SE = 0.27, p = 0.92) for early positive effects. However, the interaction was significant for early negative effects (β = −0.71, SE = 0.29, p = 0.01; Figure 3). Among males, normal metabolizers experienced fewer early negative cannabis effects (β = −0.49, SE = 0.23, p = 0.03) than slow metabolizers, while the effect was not significant for females (β = 0.25, SE = 0.20, p = 0.22). Regarding recent cannabis use, there was no significant sex*metabolizer interaction for positive (β = 0.00, SE = 0.28, p = 0.99) or negative (β = −0.30, SE = 0.35, p = 0.40) effects. Removing race from analyses did not affect the significance/non-significance of any effects.

Figure 3.

Significant interaction between sex and metabolizer status predicting early negative subjective effects of cannabis.

Note: Slow metabolizers were those participants with either CYP2C9 or CYP3A4 variants associated with reduced enzyme activity.

1.4. Discussion

Our hypothesis that genotypes associated with slow THC metabolism would be associated with increased CUD risk was not supported in the overall sample; however, females with slow metabolizer genotypes were more likely to be in the CUD group than the control group. Thus, reduced CYP2C9 or CYP3A4 activity may be a sex-specific risk factor for CUD in females. We also did not find support for our hypothesis that slow metabolizers would report more early positive effects. Instead, males, but not females, who were slow metabolizers endorsed more early negative effects of cannabis. Additionally, within the full sample, past year negative effects were elevated among slow metabolizers. Although we hypothesized that prolonged exposure to THC resulting from slowed metabolism would lead to greater positive effects, it may instead produce similar rates of positive effects but increase the chances of experiencing negative effects. Differences in cannabis metabolism may provide insights into potential impacts of increases in THC potency (ElSohly et al., 2021). Higher potency products lead to increased blood plasma THC levels, similar to what occurs among slow metabolizers who do not process cannabis into its metabolites as quickly. Thus, these findings suggest that slow metabolizers may be particularly vulnerable to the impacts of increasing THC potency due to their already heightened response to cannabis.

Interestingly, the greater negative effects experienced recently by slow metabolizers (M = 3.35 vs. 2.31 for normal metabolizers) did not mean they were less likely to have CUD (p = 0.29). Negative effects may be offset by the similar rates of positive effects across slow and normal metabolizers (M = 4.67 and. 4.81, respectively). Although most research on substance use focuses on negative outcomes more than positive ones, positive drug effects may be especially important for understanding future patterns of use (Davidson & Schenk, 1994; Fergusson et al., 2003; Le Strat et al., 2009). For example, young adults’ drinking behavior tends to be more influenced by positive alcohol-related experiences than negative ones (Lee et al., 2018; Park, 2004). The finding that negative effects were not sufficient to reduce CUD risk is also consistent with LCAs showing higher rates of CUD among individuals who experienced a range of cannabis effects, even when some were negative (Grant et al., 2005; Scherrer et al., 2009). Thus, efforts to characterize the etiology of CUD should consider the value of positive drug effects in addition to negative effects.

Male slow metabolizers seemed especially liable to early negative cannabis effects, while female slow metabolizers were not. However, female slow metabolizers were more likely to be in the CUD group. Thus, genotypes associated with reduced CYP2C9 and/or CYP3A4 activity were related to negative cannabis outcomes, but in a sex-specific manner. Sex differences in cannabis metabolism and sex-specific effects of CYP genotypes could help explain the telescoping phenomenon observed for CUD, whereby females exhibit faster progression from first use to CUD (Ehlers et al., 2010; Khan et al., 2013). As evidence shows higher potency THC is also associated with more rapid CUD symptom onset (Arterberry et al., 2019), experiencing stronger drug effects may partially account for an accelerated transition to disorder.

Several human and animal studies have observed sex differences in cannabis metabolism and subjective effects, although results have been inconsistent. Human studies on sex differences in subjective effects of smoked cannabis have found both that females reported greater positive effects than males (Cooper & Haney, 2009, 2014) and similar effects (Matheson et al., 2020), with results sometimes depending on dose and route of administration (Aghaei et al., 2023; Fogel et al., 2017; Sholler et al., 2021). Animal studies consistently demonstrate sex differences in cannabinoid metabolism (Narimatsu et al., 1992; Narimatsu et al., 1991; Wiley & Burston, 2014). Related to the current findings, a non-specific inhibitor of CYP450 enzymes reduced sex differences in THC-induced antinociception and catalepsy in rats, with the authors suggesting that observed sex differences in cannabis effects may be entirely explained by sex differences in metabolism (Tseng, Harding, & Craft, 2004). Given the lack of consistent human findings, research on sex differences in cannabis metabolism may benefit from incorporating information on CYP450 genotypes.

1.4.1. Limitations and Conclusions

Given the dearth of pre-existing data, this study sought to estimate the prevalence of select CYP450 genotypes in cannabis-using young adults and examine associations with subjective cannabis effects and CUD. Given the preliminary nature of this study, the sample size was small. Based on the population prevalence of CYP450 alleles, our a priori goal was to recruit 54 participants, which we attained, although we did not meet the exact proportion of CUD and control group participants that we had planned for this analysis. Our sample is considerably larger than previous studies examining effects of CYP450 genetic variants or enzyme activity (Bansal et al., 2023; Papastergiou et al., 2020). Furthermore, the prevalence of CYP2C9 alleles associated with slow metabolism in the control group (25%) was comparable to population estimates (~20%; Zhou, Ingelman-Sundberg, & Lauschke, 2017). Though no one in the control group had a genotype associated with reduced CYP3A4 activity, these alleles are also uncommon at the population-level (~5%; Zhou, Ingelman-Sundberg, & Lauschke, 2017). Thus, our control group genotypes were roughly as expected. Due to limited incidence of CYP3A4 alleles associated with reduced metabolism, our results are likely driven by differences in CYP2C9 alleles, so future work should parse these different genotypes and metabolic pathways. The control group may have had a longer recall period for recent cannabis effects than the CUD group, who used cannabis more regularly. However, all participants used cannabis at least three times in the last year, so recall for recent use would not extend beyond this year period. A similar limitation is that early subjective effects were retrospective. Longitudinal data could reduce recall biases. Finally, variation in cannabinoid content and route of administration also determine cannabis effects (Stout & Cimino, 2014; Zamarripa et al., 2023; Zamarripa, Vandrey, & Spindle, 2022). It was not possible to definitively characterize cannabinoid content of products used by participants. Regarding route of administration, the subsample who completed intensive longitudinal monitoring almost exclusively smoked cannabis, with very few instances of using edibles or vaping, although this does not provide information about early use or preclude that participants not included in this subsample primarily used other routes of administration.

An important limitation was the lack of determination of genetic ancestry, which would have required more extensive genotyping. Although self-reported race does not always correspond with genetically-determined ancestry, particularly among populations with a high degree of admixture (such as African Americans and Latino/as; Bryc et al., 2015), we included race as a covariate to provide some (albeit imperfect) control for population stratification, which can produce false positive or negative results if not considered. In sensitivity analyses excluding race, our results did not differ. Regardless, race is an imprecise proxy for genetic ancestry, and more robust controls for population stratification could affect findings.

Despite limitations, this study provides evidence for sex-specific effects of genotypes associated with cannabis metabolism on cannabis outcomes. Male slow metabolizers reported more early negative cannabis effects, and female slow metabolizers were more likely to be in the CUD group than control group. Overall, slow metabolizers reported more negative subjective effects during recent use. However, despite this, slow metabolizers were not less likely to develop CUD, suggesting an important role for co-occurring positive cannabis effects, which were equal across metabolizer groups.

Highlights.

Having more early positive cannabis effects increased risk of developing disorder.

Slower THC metabolism was associated with more past year negative effects.

Gene variants linked to THC metabolism show sex-specific relations with cannabis.

Male slow metabolizers also had more negative early subjective cannabis effects.

Role of Funding Sources

This work was supported by grants from the Medical University of South Carolina’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science (Chair’s Fund), the American Psychological Association Division 50 (Society on Addiction Psychology), and by the National Institutes of Health (K24DA038240 and UL1TR001450). Funding sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Kevin Gray has provided consultation to Jazz Pharmaceuticals and has received research support from Aelis Farma, Aimee McRae-Clark has received research support from Pleo Pharma, and Rachel Tomko has provided consultation to the American Society of Addiction Medicine on topics unrelated to the investigation reported here. The other authors have no relationships to disclose.

Sex assigned at birth matched gender identity for 49 of 54 participants, with five participants identifying as gender nonbinary or transgender.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aghaei AM, Spillane LU, Pittman B, Flynn LT, De Aquino JP, Nia AB, & Ranganathan M (2023). Sex differences in the acute Effects of oral THC: A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover human laboratory study. medRxiv, 2023.2011.2029.23299193. 10.1101/2023.11.29.23299193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arterberry BJ, Treloar Padovano H, Foster KT, Zucker RA, & Hicks BM (2019). Higher average potency across the United States is associated with progression to first cannabis use disorder symptom. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 195, 186–192. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal S, Zamarripa CA, Spindle TR, Weerts EM, Thummel KE, Vandrey R, Paine MF, & Unadkat JD (2023). Evaluation of cytochrome P450-mediated cannabinoid-drug interactions in healthy adult participants. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 114(3), 693–703. 10.1002/cpt.2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryc K, Durand EY, Macpherson JM, Reich D, & Mountain JL (2015). The genetic ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. American Journal of Human Genetics, 96(1), 37–53. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calakos KC, Bhatt S, Foster DW, & Cosgrove KP (2017). Mechanisms underlying sex differences in cannabis use. Current Addiction Reports, 4(4), 439–453. 10.1007/s40429-017-0174-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Vullo GC, Kennedy AP, Finger MS, Agrawal A, Bjork JM, Farrer LA, Hancock DB, Hussong A, Wakim P, Huggins W, Hendershot T, Nettles DS, Pratt J, Maiese D, Junkins HA, Ramos EM, Strader LC, Hamilton CM, & Sher KJ (2014). Data compatibility in the addiction sciences: An examination of measure commonality. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 141, 153–158. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ZD, & Haney M (2009). Comparison of subjective, pharmacokinetic, and physiological effects of marijuana smoked as joints and blunts. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 103(3), 107–113. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ZD, & Haney M (2014). Investigation of sex-dependent effects of cannabis in daily cannabis smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 136, 85–91. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daedelow LS, Banaschewski T, Berning M, Bokde ALW, Brühl R, Burke Quinlan E, Curran HV, Desrivières S, Flor H, Grigis A, Garavan H, Hardon A, Kaminski J, Martinot J-L, Paillère Martinot M-L, Artiges E, Murray H, Nees F, Oei NYL, . . . Heinz A (2021). Are psychotic-like experiences related to a discontinuation of cannabis consumption in young adults? Schizophrenia Research, 228, 271–279. 10.1016/j.schres.2021.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson ES, & Schenk S (1994). Variability in subjective responses to marijuana: Initial experiences of college students. Addictive Behaviors, 19(5), 531–538. 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90008-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine EG, Pingitore AM, Margiotta KN, Hadaway NA, Reid K, Peebles K, & Hyun JW (2021). Frequency of concealment, fabrication and falsification of study data by deceptive subjects. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 21, 100713. 10.1016/j.conctc.2021.100713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine EG, Waters ME, Putnam M, Surprise C, O’Malley K, Richambault C, Fishman RL, Knapp CM, Patterson EH, Sarid-Segal O, Streeter C, Colanari L, & Ciraulo DA (2013). Concealment and fabrication by experienced research subjects. Clinical Trials, 10(6), 935–948. 10.1177/1740774513492917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Gizer IR, Vieten C, Gilder DA, Stouffer GM, Lau P, & Wilhelmsen KC (2010). Cannabis dependence in the San Francisco Family Study: Age of onset of use, DSM-IV symptoms, withdrawal, and heritability. Addictive Behaviors, 35(2), 102–110. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElSohly MA, Chandra S, Radwan M, Majumdar CG, & Church JC (2021). A comprehensive review of cannabis potency in the United States in the last decade. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 6(6), 603–606. 10.1016/j.bpsc.2020.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT, & Madden PAF (2003). Early reactions to cannabis predict later dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(10), 1033. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.10.1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel JS, Kelly TH, Westgate PM, & Lile JA (2017). Sex differences in the subjective effects of oral Δ9-THC in cannabis users. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 152, 44–51. 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds J, Veldheer S, Yingst J, Hrabovsky S, Wilson SJ, Nichols TT, & Eissenberg T (2015). Development of a questionnaire for assessing dependence on electronic cigarettes among a large sample of ex-smoking e-cigarette users. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 17(2), 186–192. 10.1093/ntr/ntu204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Lyons MJ, Tsuang M, True WR, & Bucholz KK (2005). Subjective reactions to cocaine and marijuana are associated with abuse and dependence. Addictive Behaviors, 30(8), 1574–1586. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green B, Kavanagh D, & Young R (2003). Being stoned: a review of self-reported cannabis effects. Drug and Alcohol Review, 22(4), 453–460. 10.1080/09595230310001613976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hryhorowicz S, Walczak M, Zakerska-Banaszak O, Słomski R, & Skrzypczak-Zielińska M (2018). Pharmacogenetics of cannabinoids. European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics, 43(1), 1–12. 10.1007/s13318-017-0416-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick M, & E. (2022). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use 1975–2021: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. In. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Jones SK, Wolf BJ, Froeliger B, Wallace K, Carpenter MJ, & Alberg AJ (2021). Nicotine metabolism predicted by CYP2A6 genotypes in relation to smoking cessation: A systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 24(5), 633–642. 10.1093/ntr/ntab175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AC, Smith RV, Tate JP, Mcginnis K, Xu K, Becker WC, Lee K-Y, Lynch K, Sun N, Concato J, Fiellin DA, Zhao H, Gelernter J, & Kranzler HR (2018). AUDIT-C and ICD codes as phenotypes for harmful alcohol use: association with ADH1B polymorphisms in two US populations. Addiction, 113(12), 2214–2224. 10.1111/add.14374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SS, Secades-Villa R, Okuda M, Wang S, Pérez-Fuentes G, Kerridge BT, & Blanco C (2013). Gender differences in cannabis use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 130(1), 101–108. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krainc T, & Fuentes A (2022). Genetic ancestry in precision medicine is reshaping the race debate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(12), e2203033119. 10.1073/pnas.2203033119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Strat Y, Ramoz N, Horwood J, Falissard B, Hassler C, Romo L, Choquet M, Fergusson D, & Gorwood P (2009). First positive reactions to cannabis constitute a priority risk factor for cannabis dependence. Addiction, 104(10), 1710–1717. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02680.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Rhew IC, Patrick ME, Fairlie AM, Cronce JM, Larimer ME, Cadigan JM, & Leigh BC (2018). Learning from experience? The influence of positive and negative alcohol-related consequences on next-day alcohol expectancies and use among college drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(3), 465–473. 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung J, Chan GCK, Hides L, & Hall WD (2020). What is the prevalence and risk of cannabis use disorders among people who use cannabis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 109, 106479. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Zhao H, & Gelernter J (2011). Strong association of the alcohol dehydrogenase 1B gene (ADH1B) with alcohol dependence and alcohol-induced medical diseases. Biological Psychiatry, 70(6), 504–512. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Agrawal A, Henders A, Nelson EC, Madden PAF, & Martin NG (2012). An Australian twin study of cannabis and other illicit drug use and misuse, and other psychopathology. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 15(5), 631–641. 10.1017/thg.2012.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons MJ, Toomey R, Meyer JM, Green AI, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, True WR, & Tsuang MT (1997). How do genes influence marijuana use? The role of subjective effects. Addiction, 92(4), 409–417. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb03372.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaiyandi V, Sellers EM, & Tyndale RF (2005). Implications of CYP2A6 genetic variation for smoking behaviors and nicotine dependence*. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 77(3), 145–158. 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson J, Sproule B, Di Ciano P, Fares A, Le Foll B, Mann RE, & Brands B (2020). Sex differences in the acute effects of smoked cannabis: evidence from a human laboratory study of young adults. Psychopharmacology, 237(2), 305–316. 10.1007/s00213-019-05369-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narimatsu S, Watanabe K, Matsunaga T, Yamamoto I, Imaoka S, Funae Y, & Yoshimura H (1992). Cytochrome P-450 isozymes involved in the oxidative metabolism of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol by liver microsomes of adult female rats. Drug Metabolism and Disposition: The Biological Fate of Chemicals, 20(1), 79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narimatsu S, Watanabe K, Yamamoto I, & Yoshimura H (1991). Sex difference in the oxidative metabolism of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the rat. Biochemical Pharmacology, 41(8), 1187–1194. 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90657-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Le A, & Han BH (2021). Quarterly trends in past-month cannabis use in the United States, 2015–2019. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 219, 108494. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papastergiou J, Li W, Sterling C, & van den Bemt B (2020). Pharmacogenetic-guided cannabis usage in the community pharmacy: evaluation of a pilot program. Journal of Cannabis Research, 2(1), 24. 10.1186/s42238-020-00033-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL (2004). Positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students. Addictive Behaviors, 29(2), 311–321. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, Pallonen UE, Fava JL, Ding L, & Niaura R (1996). Measuring nicotine dependence among high-risk adolescent smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 21(1), 117–127. 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00048-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond-Rakerd LS, Slutske WS, Lynskey MT, Agrawal A, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Heath AC, Statham DJ, & Martin NG (2016). Age at first use and later substance use disorder: Shared genetic and environmental pathways for nicotine, alcohol, and cannabis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(7), 946–959. 10.1037/abn0000191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachse-Seeboth C, Pfeil J, Sehrt D, Meineke I, Tzvetkov M, Bruns E, Poser W, Vormfelde SV, & Brockmöller J (2009). Interindividual variation in the pharmacokinetics of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol as related to genetic polymorphisms in CYP2C9. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 85(3), 273–276. 10.1038/clpt.2008.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. (2018). SAS® Studio 3.8: User’s Guide. In. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer JF, Grant JD, Duncan AE, Sartor CE, Haber JR, Jacob T, & Bucholz KK (2009). Subjective effects to cannabis are associated with use, abuse and dependence after adjusting for genetic and environmental influences. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 105(1), 76–82. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, & Dunbar GC (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59, 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen G-Q, Abdullah KG, & Wang QK (2009). The TaqMan Method for SNP Genotyping. In Komar AA (Ed.), Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms: Methods and Protocols (pp. 293–306). Humana Press. 10.1007/978-1-60327-411-1_19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholler DJ, Strickland JC, Spindle TR, Weerts EM, & Vandrey R (2021). Sex differences in the acute effects of oral and vaporized cannabis among healthy adults. Addiction Biology, 26(4), e12968. 10.1111/adb.12968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout SM, & Cimino NM (2014). Exogenous cannabinoids as substrates, inhibitors, and inducers of human drug metabolizing enzymes: a systematic review. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 46(1), 86–95. 10.3109/03602532.2013.849268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tart CT (1970). Marijuana intoxication: Common experiences. Nature, 226(5247), 701–704. 10.1038/226701a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng AH, Harding JW, & Craft RM (2004). Pharmacokinetic factors in sex differences in Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol-induced behavioral effects in rats. Behavioural Brain Research, 154(1), 77–83. 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verweij KJH, Zietsch BP, Lynskey MT, Medland SE, Neale MC, Martin NG, Boomsma DI, & Vink JM (2010). Genetic and environmental influences on cannabis use initiation and problematic use: a meta-analysis of twin studies. Addiction, 105(3), 417–430. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02831.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, & Burston JJ (2014). Sex differences in Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol metabolism and in vivo pharmacology following acute and repeated dosing in adolescent rats. Neuroscience Letters, 576, 51–55. 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.05.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolowich WR, Greif R, Kleine-Brueggeney M, Bernhard W, & Theiler L (2019). Minimal physiologically based pharmacokinetic model of intravenously and orally administered delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in healthy volunteers. European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics, 44(5), 691–711. 10.1007/s13318-019-00559-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SE, Rhee SH, Stallings MC, Corley RP, & Hewitt JK (2006). Genetic and environmental vulnerabilities underlying adolescent substance use and problem use: general or specific? Behavior Genetics, 36(4), 603–615. 10.1007/s10519-006-9066-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamarripa CA, Spindle TR, Surujunarain R, Weerts EM, Bansal S, Unadkat JD, Paine MF, & Vandrey R (2023). Assessment of orally administered Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol when coadministered with cannabidiol on Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in healthy adults: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open, 6(2), e2254752. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.54752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamarripa CA, Vandrey R, & Spindle TR (2022). Factors that impact the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of cannabis: A review of human laboratory studies. Current Addiction Reports, 9(4), 608–621. 10.1007/s40429-022-00429-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zendulka O, Dovrtělová G, Nosková K, Turjap M, Šulcová A, Hanuš L, & Juřica J (2016). Cannabinoids and cytochrome P450 interactions. Current Drug Metabolism, 17(3), 206–226. 10.2174/1389200217666151210142051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Ingelman-Sundberg M, & Lauschke V (2017). Worldwide distribution of cytochrome P450 alleles: A meta-analysis of population-scale sequencing projects. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 102(4), 688–700. 10.1002/cpt.690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]