Abstract

Intro:

Substance use and associated problems often return following treatment for substance use disorder (SUD), which disproportionally impact Black/African American (AA) individuals. Social support and spiritual well-being are sources of recovery capital identified as particularly important among Black/AA adults. Social support and spiritual well-being are also posited mechanisms in 12-step; thus, this study tested the effects of social support and spiritual well-being on substance use outcomes over time, distinct from 12-step involvement, among Black/AA adults post-SUD treatment. The study hypothesized that social support and spiritual well-being would demonstrate significant interactions with time, respectively, on substance use frequency and substance use consequences, above the effect of 12-step involvement.

Method:

The study drew data from a study of 262 adults (95.4% Black/AA) entering residential SUD treatment (NCT#01189552). Assessments were completed at pretreatment and at 3-, 6-, and 12-months posttreatment. Two generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) tested the effects of social support and spiritual well-being, above the effect of 12-step involvement, on substance use frequency and substance use consequences over the course of 12-months posttreatment.

Results:

Higher spiritual well-being predicted significantly less frequent substance use during recovery (ß = 0.00, p =.03). Greater 12-step involvement predicted significantly fewer substance use consequences during recovery (ß = 0.00, p =.02). In post hoc analyses the effect of spiritual well-being and 12-step involvement dissipated by 3.5- and 6.6-months posttreatment, respectively. The study found no significant effects of social support over time.

Discussion:

Spiritual well-being and 12-step involvement are associated with lower substance use and substance use consequences, respectively, in the early months of posttreatment recovery among Black/AA adults. These findings contribute to the growing recovery capital literature informing paths to recovery and sources of support outside of 12-step affiliation. However, these effects diminish over time.

Keywords: Recovery capital, Substance use disorder, Treatment outcomes, Social support, Spiritual well-being, 12-step

1. Introduction

Substance use disorders (SUD), including alcohol and drug use disorders as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – 5th edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), is a public health crisis affecting up to 40 million adults in the U.S. as of 2020 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). Among adults who complete SUD treatment, between 40% and 85% report a return to substance use within a year (Brandon et al., 2007; McLellan et al., 2001). In addition, substance use consequences such as relationship conflict and physical health challenges are characteristic of meeting SUD criteria as per the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and awareness of consequences can build motivation for change (Blume et al., 2006; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Thus, substance use consequences are an important clinical outcome to consider as a metric of successful recovery (Allen, 2005; Cisler, 2005; Kiluk et al., 2013, 2020).

Black and African American (AA) individuals experience SUD at rates similar to the rest of the population (SAMHSA, 2019), yet Black/AA adults are less likely to initiate (Acevedo et al., 2012) and complete (Saloner & Lê Cook, 2013) SUD treatment compared to white individuals. This may be due in part to systemic barriers to care including lack of quality publicly funded programs for low-income individuals, which disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minorities (Saloner & Lê Cook, 2013). Black/AA adults experience higher rates of return to substance use and relapse (Chartier & Caetano, 2010) and disproportionally greater substance use consequences compared to white adults including incarceration and police violence (Cooper, 2015; Dunlap & Johnson, 1992; Edwards et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 2018). Considering these heightened threats to recovery, research investigating factors that promote better posttreatment outcomes among Black/AA adults is essential.

1.1. Social support and spiritual well-being as recovery capital

Recovery is characterized as an individual’s striving for overall functioning and wellness across psychological, physical, spiritual, and social domains while maintaining remission from problematic levels of substance use and associated symptoms (SAMHSA, 2012; Ashford et al., 2019; Best et al., 2016). Thus, measuring recovery includes not only SUD symptoms, but also the factors that to contribute to quality of life, wellness, and functioning facilitative of symptom remission. These factors are defined as recovery capital, or the key personal and social resources individuals can draw upon in their efforts to overcome their SUD (Cloud & Granfield, 2008). Examples of recovery capital include personal characteristics such as sense of purpose and coping skills, interpersonal resources such as social support, and community resources such as availability of mental and physical healthcare (Cloud & Granfield, 2008; Hennessy, 2017). Recovery capital theory provides a strengths-based approach to examine how individuals can draw on their resources to sustain positive effects of treatment on substance use and associated consequences in the long-term. Higher overall recovery capital is associated with lower SUD severity and predicts higher likelihood of SUD treatment completion (Sánchez et al., 2020), sustained recovery (Laudet et al., 2006), quality of life (Härd et al., 2022), and lower stress levels one-year post-SUD treatment (Laudet & White, 2008). Here, we focus on two psychological components of recovery capital – perceived social support and spiritual well-being – given they are also both sources of substance free reinforcement, a known factor in maintaining reductions in substance use (Field et al., 2019; McKay, 2017).

Social support has been widely studied as an important source of recovery capital. Higher social support is associated with significantly lower odds of having a SUD (Kahle et al., 2020) and several SUD correlates including lower risk of relapse (Havassy et al., 1991) and lower alcohol intake posttreatment (Dobkin et al., 2002). Higher social support is also associated with higher likelihood of treatment entry (Kelly et al., 2010) and retention (Dobkin et al., 2002), and higher abstinence self-efficacy (Stevens et al., 2015). All of these studies have been among primarily white samples; therefore, it is important to study the utility of this construct in recovery among marginalized groups with SUD. Some studies indicate a positive role of social support in recovery among Black/AA adults. Higher rates of social support gained through marriage and religious participation protect against substance use among Black/AA adults (Hearld et al., 2017). Black/AA adults in rural Mississippi report abstinence oriented social support and other close relationships as primary factors in obtaining and maintaining sobriety from cocaine (Cheney et al., 2017). Among Black sexual minority men, lower social support partially mediates their higher likelihood of SUD compared to white sexual minority men (Buttram et al., 2013). However, little research has investigated the effect of social support on trajectories of recovery outcomes among Black/AA adults undergoing SUD treatment.

Spiritual well-being is another component of recovery capital associated with achieving and sustaining recovery from SUD (Flynn et al., 2003; Geppert et al., 2007; Laudet et al., 2006; Walton-Moss et al., 2013). Spiritual well-being is defined as the general and transcendent subjective experience of life meaning and purpose, which can be either connected to or separate from a religious institution or entity (Laudet et al., 2006; Vaughan et al., 1998). Spiritual well-being is associated with better physical, psychological and emotional health (Aldwin et al., 2014; Balboni et al., 2022; Mathew et al., 1996; Matthews & Larson, 1995) and buffers individuals from life stressors such as chronic illness (Aldwin et al., 2014; Fehring et al., 1987; Landis, 1995). Spiritual well-being is overlapping but distinct from religiosity, which refers to a set of spiritual practices including overt (e.g., involvement in religious services) and covert (e.g., prayer) behaviors. Spiritual well-being also overlaps with spirituality, but uniquely incorporates an existential, agnostic dimension (i.e., a sense of purpose separate from anything sacred) in addition to more God or deity-centered spirituality (Paloutzian & Ellison, 1982; Worley, 2020). Given the overlap and general lack of distinction between spirituality and spiritual well-being in the literature, findings on spirituality will be included in summarizing supporting literature for the current paper.

Spiritual well-being can provide several psychological and emotional benefits for adults in SUD recovery (Laudet et al., 2006; Worley, 2020) including a sense of meaning, connectedness, and purpose (Flynn et al., 2003; Geppert et al., 2007; Laudet et al., 2006; Worley, 2020). Indeed, spiritual well-being is associated with concurrent abstinence (Burgess et al., 2021; Walton-Moss et al., 2013 for review) and one study found that increased spiritual well-being across six months of recovery predicts higher abstinence three months later, controlling for 12-step program involvement (Robinson et al., 2011). Two aspects of spiritual well-being – life meaning and spirituality - predict sustained recovery and better quality of life, respectively, over one year among adults in recovery from polysubstance use (Laudet & White, 2008). Higher spiritual well-being is also predictive of lower craving among adults in self-help recovery groups (Dermatis & Galanter, 2016), an association explained elsewhere by higher self-efficacy (Mason et al., 2009).

Some studies have investigated the role of spiritual well-being among Black/AA adults in SUD recovery. Among Black/AA women in recovery, those with higher spirituality have better self-concept, coping, and are more satisfied with their social support and family relationships compared to women with low spirituality (Brome et al., 2000). Among Black/AA adults in outpatient SUD treatment, higher spirituality predicts better treatment engagement and posttreatment coping ability, well-being, and fewer SUD symptoms (Piedmont, 2004), and higher likelihood of abstinence compared to white participants at 15 months posttreatment (Krentzman et al., 2010). However, the latter study tested the effect of spiritual well-being at 15-months posttreatment on a binary abstinence outcome (6-months of achieved abstinence) and did not account for 12-step involvement in the analyses. Thus, it remains untested how spiritual well-being over the course of several months of posttreatment recovery may relate to more continuous substance use outcomes beyond binary abstinence alone, and whether these associations are present even when controlling for 12-step involvement.

1.2. 12-Step as a source of social support and spiritual well-being

Literature indicates that the social supports provided by 12-step meetings and the sense of spiritual well-being incorporated in 12-step ideology are primary mechanisms of 12-step’s positive effect on recovery (Bond et al., 2003; Kelly, Stout, Magill, Tonigan, et al., 2011; Kelly et al., 2009). Changes in social network composition and increased spiritual practices and beliefs partially mediate the association between 12-step attendance and improved substance use outcomes (Kelly et al., 2011). However, 12-step programs are not helpful for everyone (Witbrodt & Kaskutas, 2005), and literature is mixed on the relative utility of 12-step among Black/AA communities. Some literature indicates few racial differences in the beneficial effects of 12-step participation on substance use consequences (Hai et al., 2019) while other literature suggests the history of 12-step in primarily white communities and the focus on powerlessness in the face of disease may contribute to lower engagement in 12-step programs in Black/AA communities (Durant, 2005; Timko, 2008). Therefore, testing the degree to which elements of recovery capital (i.e., spiritual well-being and social support) positively impact substance use and associated consequences above and beyond the influence of 12-steps is important.

1.3. The current study

SUD is a public health crisis affecting millions of people in the U.S. and most adults who receive treatment return to substance use within a year. Researchers and clinicians are increasingly focused on a holistic characterization of successful recovery: what are the types of recovery capital (e.g., social, spiritual) that contribute to an individual’s overall well-being and help maintain remission from SUD. The consequences associated with substance use disproportionally affect Black/AA individuals, rendering this population vulnerable to more factors that may hinder their recovery process. Testing associations between potential sources of recovery capital and substance use outcomes can help inform the intersection of public health, psychology, and clinical care to help patients identify how to maintain treatment progress and grow in their recovery.

The aim of the current study was to test the effect of spiritual well-being and social support on substance use frequency and related consequences from pre- to 12-months posttreatment, controlling for the effect of 12-step involvement, in a sample of primarily Black/AA adults entering SUD treatment. While 12-step programming may provide access to some of these sources of recovery capital, it is important to understand the impact of these factors distinct from 12-step alone lest we relegate individuals with SUD to a one-size-fits-all path to recovery. We hypothesized that higher spiritual well-being and higher social support would be associated with lower substance use frequency and related consequences over time, above the effect of 12-step involvement.

2. Method

2.1. Study sample & Procedure

The study drew data from a parent study of a single-site, two-arm parallel-group trial at a residential treatment facility in Washington D.C. (NCT# 01189552; Daughters et al., 2018). Patients at the residential substance use treatment facility were recruited for the parent study at treatment entry, and within a week of entry into the program all patients completed an intake interview and were assessed for eligibility, provided informed consent, and completed pretreatment measures. To enter the facility patients were either court mandated or entered treatment voluntarily with public funding support. Exclusion criteria included a) below a fifth-grade English reading level, b) psychotic symptoms, and c) initiation of psychotropic medication use in the three months prior to the pretreatment assessment. The study randomly assigned participants to one of two conditions in addition to treatment as usual provided by the residential treatment program: an experimental behavioral activation treatment for substance use or a supportive counseling control. Participants completed follow-up assessments at 3-, 6-, and 12-months posttreatment. Detailed descriptions of study procedures can be found in the primary outcome manuscript (Daughters et al., 2018).

2.2. Measures

Participant Characteristics

The study collected participants’ self-reported demographic information at the pretreatment assessment, and included race/ethnicity, age, sex, employment status, income, and whether they were court-mandated to treatment. For race/ethnicity, participants had the option to check all categories that apply (White/Caucasian, Black/African American, Asian/Southeast Asian, Hispanic/Latino, Native American/American Indian, or Other (with option to fill in the blank)). We corroborated court-mandated status by the pretrial release to treatment program provided by facility records. The study assessed posttreatment incarceration via participant self-report of number of days incarcerated at each assessment since treatment discharge. The study assessed criteria for diagnosis of DSM-IV substance dependence (cocaine, opioid, marijuana, alcohol, hallucinogen/PCP) in the past year and current psychiatric disorders at pretreatment by trained interviewers with the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID– IV) (First & Gibbon, 2004).

The number of drug classes used weekly was assessed via participant’s self-reported past-year frequency of substance use among 11 classes which was coded into a binary variable reflecting whether participants used each drug class weekly (0 = no, 1= yes).

12-step involvement

The study measured 12-step involvement using the Drug and Alcohol Problems subscale of the Treatment Services Questionnaire (McLellan 1992). Participants self-reported the number of times they attended a 12-step group session (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous) since the last assessment.

Social support

We measured social support using the Medical Outcomes Survey (MOS) Social Support scale (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991). The MOS assesses for general social support and contains 19 items across four subscales: emotional/informational support, tangible support, affectionate support, and positive social interactions. Response options for individual questions are on a six-point Likert scale ranging from “None of the time” (1) to “All of the time” (5). Total scores are then transformed to range from 0–100 with higher scores reflecting greater social support. The MOS has demonstrated high discriminant validity, good to excellent reliability (α=0.91–0.97), and good stability over the course of one year (0.72–0.78) (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991). Reliability in the current study was excellent across timepoints (α=0.98–0.99).

Spiritual well-being

The study measured spiritual well-being using the Spiritual Wellbeing Scale (SWBS) (Paloutzian & Ellison, 1982). The SWBS assesses an individual’s overall well-being and life satisfaction and includes 20 items across religious and existential well-being subscales. Response options for individual questions are on a six-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (6). Total scores range from 20–120 with higher scores reflecting a greater sense of spiritual well-being. The SWBS has demonstrated good to excellent reliability (α= 0.89–0.94) and high validity in measuring well-being (Bufford et al., 1991; Luna et al., 2017; Paloutzian & Ellison, 1982). Reliability in the current study was acceptable to good across timepoints (α=0.70–0.80).

Substance use consequences

Consequences of substance use was measured via the Short Inventory of Problems – Alcohol and Drugs (SIP-AD) (Blanchard et al., 2003). The SIP assesses the past month presence and frequency of consequences associated with substance use and includes 15 items comprising of five domains: intrapersonal problems, interpersonal problems, social problems, impulsivity, and physical problems. Response options for each item were on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “Never” (0) to “Daily or almost daily” (3). Total scores range from 0–45. The SIP has demonstrated excellent reliability in populations with SUD (α=0.95) (Kiluk et al., 2013). Reliability in the current study was excellent across timepoints (α=0.94–0.97).

Substance use

We assessed substance use frequency via the Timeline Followback (TLFB) (Sobell & Sobel, 1990), which uses a calendar method to assess participant’s retrospective self-report of daily substance use within a given timeframe. The study calculated substance use frequency as the participant’s self-reported total number of days of any substance use since the last assessment, collected at each follow-up. The TLFB is a gold standard measurement demonstrating high validity when compared to biological indicators of substance use (Hjorthøj et al., 2012).

2.3. Statistical analyses

The study analyzed all data in SPSS version 28. We examined continuous study variables for normality via visual inspection of histograms. To increase the interpretability of results, the study grand mean-centered social support, spiritual well-being, and 12-step involvement at each timepoint.

The study tested the effects of social support and spiritual well-being over time on substance use and substance use consequences, respectively, with two generalized linear mixed models (GLMM). We used GLMM instead of traditional random effects multilevel models to account for the count dependent variables with high dispersion. GLMM drops cases with any missing data at any timepoint. Models were specified with Poisson (substance use frequency) and negative binomial (substance use consequences) distributions and a log-link function. Each model included fixed effects of continuous time (in months), and time-lagged 12-step involvement, social support and spiritual well-being at Time-1 (T-1). The study used time lags to account for the retrospective report of substance use frequency and consequences to accurately model the prospective effect of 12-step, social support, and spiritual well-being. The study included two-way interactions of time by 12-step, social support, and spiritual well-being to test the primary aims. In the model predicting substance use frequency, we included number of days assessed as a covariate to account for variability in days between assessments. Significance of effects were determined by unstandardized beta coefficients, p value (<.05) and 95% confidence intervals. We calculated variance inflation factors (VIFs) for 12-step involvement, social support, and spiritual well-being to analyze the magnitude of multicollinearity of model terms, and were below 5 in each model, indicating minimal risk of multicollinearity over-inflating model estimates.

Covariate selection

Potential covariates included demographic variables (age, sex, income, court mandated status), current DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses, and substance use characteristics (substances used weekly in the past year, number of substances for which participants met dependence). To determine the associations between each set of variables and the dependent variables, six omnibus generalized linear mixed models were run predicting substance use frequency and substance use consequences, respectively, in which main effects of potential covariates were included as fixed effects. Variables with significant associations with either dependent variable at any timepoint were included as covariates in the primary analyses for that dependent variable. The study also tested all statistical models with treatment condition included as a covariate, which did not impact the results.

Post-hoc analyses

First, we conducted post-hoc analyses on significant interactions to determine meaningful points in time between slopes of “high” and “low” (+/− one standard deviation from the mean) values of the moderator. The post-hoc formula is a ratio (displayed below) that represents a meaningful point(s) in time (X) where the slopes of “high” versus “low” values of the independent variable either become or are no longer significantly different. Each coefficient represented in the formula below is determined by the model output for each aim, with the exception of the fixed variable K representing the critical value (1.96) at which a t statistic need to meet or exceed to be statistically significant.

For a given significant interaction, the following values are taken from the model output to compute the post-hoc formula: β1 equals the parameter estimate for the independent variable of interest in the significant interaction term, β3 equals the parameter estimate for the significant interaction term, equals the variance estimated for β1, equals the variance estimated for β3, and equals the covariance of β1 and β3. This formula is translated into quadratic form (squared) to account for the two points at which the slopes are estimated to be significantly different from one another (i.e., on both sides of where they are estimated to intersect) by the model. Depending on the interaction found, one or both points may be meaningful.

Simplified and solved for X2, representing the timepoint(s) at which the difference between slopes is or is no longer significant.

Second, for any significant effect found for either spiritual well-being or social support over time on substance use frequency or consequences, we conducted post-hoc analyses testing identical statistical models but with the main effect of each subscale (e.g., existential well-being and religious well-being of the SWBS) and their interactions with time, respectively to determine whether one component of this construct contributed to more variance in predicting the outcome.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

Pretreatment demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Sample means for social support, spiritual well-being, 12-step involvement, substance use frequency, and substance use consequences at pretreatment and each follow-up assessment are presented in Table 2. Correlations between study variables at each time point are presented in Supplementary Table 8. Participant retention rates were 81.7% at 3-month follow-up, 82.9% at 6-month follow-up, and 84% at 12-month follow-up. Detailed descriptions of participant attrition can be found in the primary outcome manuscript (Daughters et al., 2018).

Table 1.

Pretreatment participant characteristics.

| Variable | Total (n=262) |

|---|---|

| Age, M(SD) | 42.7 (11.8) |

| Male, n (%) | 186 (70.7) |

| Black/African American, n(%) | 249 (94.7) |

| Income, n(%) | |

| $0–$9,999 | 144 (54.8) |

| $10,000–$29,999 | 56 (21.3) |

| $30,000–$100,000 | 63 (24.0) |

| Unemployed, n(%) | 213 (81) |

| Court-mandated treatment, n(%) | 191 (72.6) |

| DSM-IV substance dependence, n(%) | |

| Cocaine | 86 (32.7) |

| Opiates | 31 (11.8) |

| Cannabis | 28 (10.6) |

| Alcohol | 81 (30.8) |

| Hallucinogens/PCP | 37 (14.2) |

| None | 66 (25.1) |

| Weekly substance use, past year, n (%) | |

| Cocaine | 55 (20.9) |

| Opiates | 26 (9.9) |

| Cannabis | 31 (11.8) |

| Alcohol | 89 (33.8) |

| PCP | 28 (10.6) |

| Methamphetamine | 1 (0.4) |

| Ecstasy | 3 (1.1) |

| Sedatives | 1 (0.4) |

| DSM-IV Psychiatric disorder diagnoses, n (%) | |

| Bipolar 1 | 10 (3.8) |

| Major depression | 9 (3.4) |

| Obsessive compulsive | 12 (4.6) |

| Panic | 4 (1.5) |

| Post-traumatic stress | 14 (5.3) |

| Social phobia | 11 (4.2) |

| Generalized anxiety | 22 (8.4) |

Note: M = mean, SD = standard deviation, n = number of individuals in sample, PCP = phenylcyclohexyl piperidine.

Table 2.

Sample means across each assessment period

| Variable | Pretreatment n=262 | 3M FU n=218 M(SD) |

6M FU n=222 |

12M FU n=225 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) missing | ||||

| 12-Step meetings | -- | 19.9 (33.6) | 24.9 (39.6) | 34.9 (55.4) |

| -- | 3 (1.4) | 4 (1.8) | 4 (1.7) | |

| Spiritual well-being | 76.2 (5.4) | 75.1 (5.8) | 74.7 (6.2) | 75.5 (6.2) |

| 0 (0) | 13 (5.9) | 9 (4.0) | 12 (5.3) | |

| Social support | 73.2 (19.2) | 71.7 (20.8) | 71.0 (20.9) | 69.9 (21.8) |

| 0 (0) | 12 (5.5) | 9 (4.0) | 12 (5.3) | |

| # Days substance use | -- | 14.6 (27.4) | 15.9 (28.2) | 16.6 (27.8) |

| -- | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (.44) | |

| Substance use consequences | 23.6 (13.8) | 11.3 (13.6) | 12.1 (13.8) | 12.3 (13.6) |

| 0 (0) | 13 (5.9) | 9 (4.0) | 12 (5.3) | |

Note: M=mean, SD= standard deviation, n = number of individuals in sample, M=month, FU=follow-up

3.2. Test of covariates

The model results testing associations among potential covariates and study outcomes are presented in Supplementary Tables 1–6. Incarceration status over time (ß = −.52, p = .03), age (ß = −.02, p = .01), and weekly alcohol use (ß = −.83, p < .001) in the past year emerged as significant predictors of substance use frequency. Male sex (ß = −.70, p = .04) emerged as a significant predictor of substance use consequences.

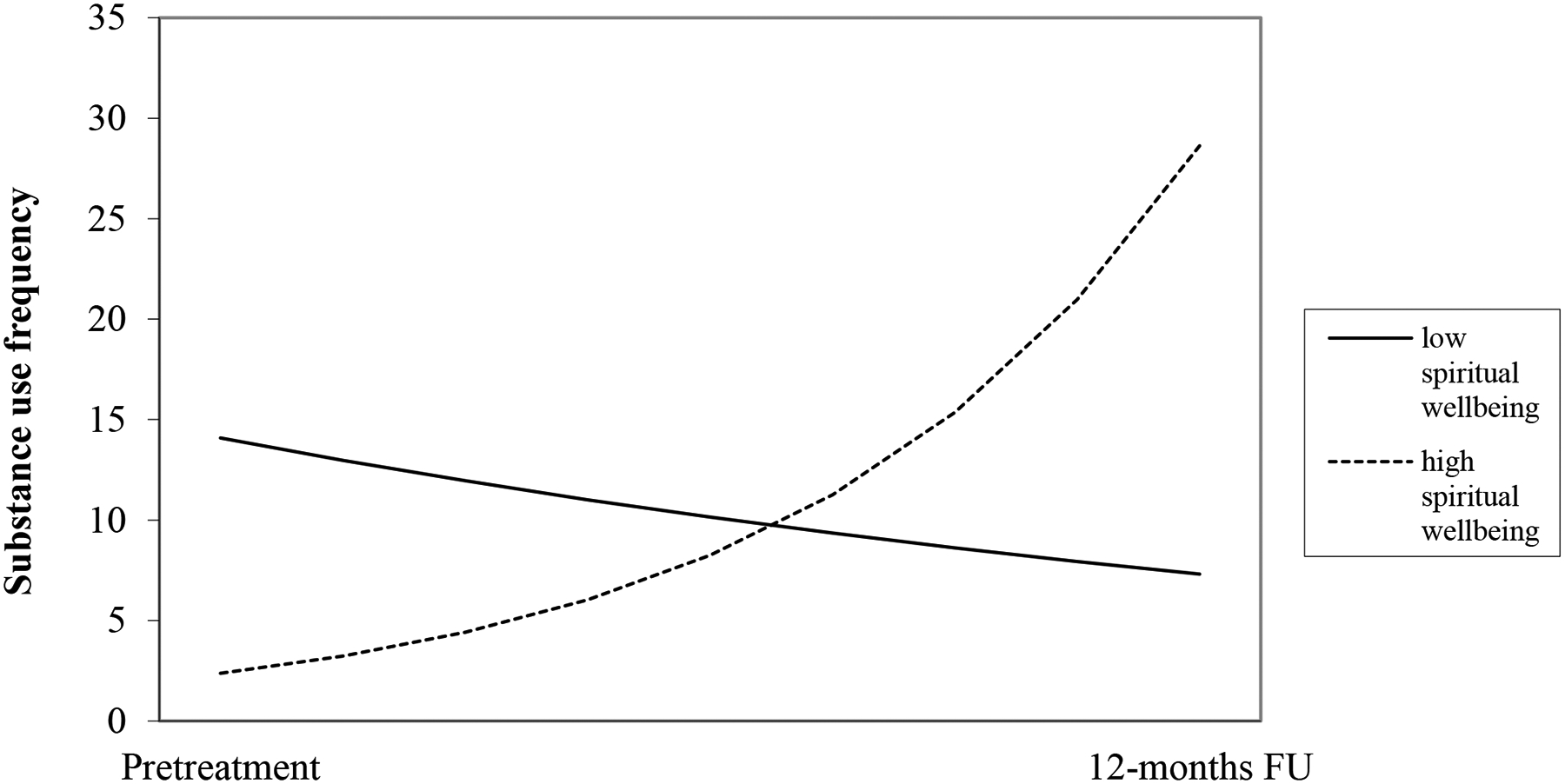

3.3. Substance use frequency

The model results predicting substance use frequency are presented in Table 3. Only the interaction of time by spiritual well-being was significant (ß = 0.00, p =.03), such that higher spiritual well-being was associated with less frequent substance use over time (Figure 1). The post-hoc test produced a solution of 3.5 and 11 months as the points in time when a change occurred in the significance between low and high (±1SD) spiritual well-being. Higher spiritual well-being significantly predicted less frequent substance use until three and a half months posttreatment, then at 11 months posttreatment was associated with more frequent substance use compared to low spiritual well-being. Post-hoc analyses testing the effects of religious and existential well-being subscales separately on substance use frequency indicated that neither subscale significantly predicted substance use frequency over time (Supplemental Table 7).

Table 3.

The effect of social support and spiritual well-being on substance use frequency from pre- to 12-months posttreatment.

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Intercept | 2.30 | 0.52 | 4.42 | <0.01 | 1.23 | 3.37 |

| Days assessed | 0.01 | 0.00 | 4.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Incarceration status | −0.31 | 0.21 | −0.15 | 0.88 | −0.51 | 0.45 |

| Age | −0.27 | 0.01 | −2.68 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 |

| Weekly alcohol use past year | −0.85 | 0.23 | −3.58 | <0.01 | −1.30 | −0.39 |

| Time | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.11 | 0.91 | −0.12 | 0.11 |

| 12-Step involvement | −0.02 | 0.01 | −1.89 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.00 |

| Spiritual well-being | −0.03 | 0.01 | −2.60 | 0.12 | −0.08 | 0.02 |

| Social support | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.73 | −0.11 | 0.12 |

| Time*12-Step involvement | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.03 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Time*social support | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.08 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Time*spiritual well-being | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.35 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

Note: ß = beta coefficient, SE = standard error

Figure 1.

The effect of spiritual well-being on substance use frequency from pre- to 12-months posttreatment.

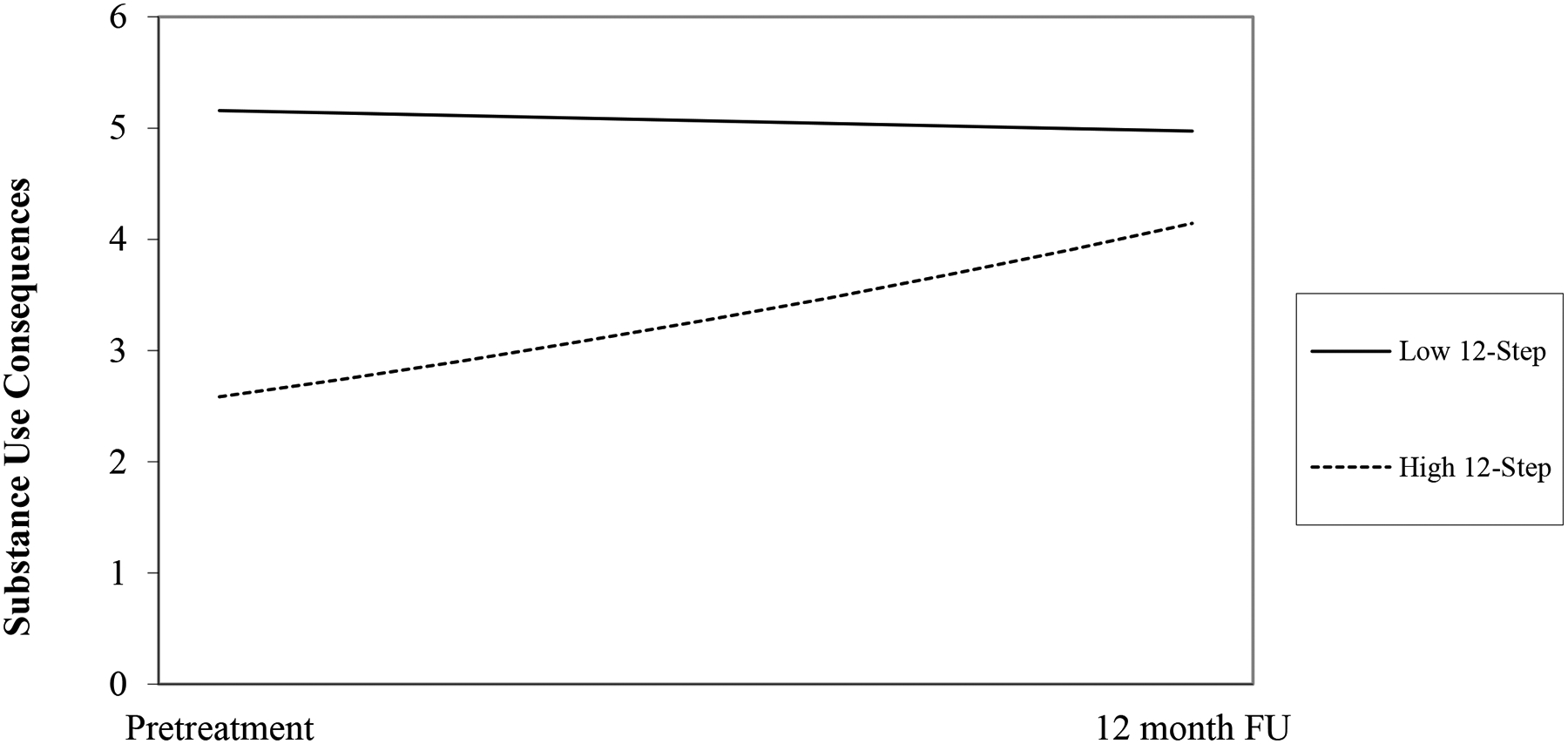

3.4. Substance use consequences

The model results predicting substance use consequences are presented in Table 4. Only the interaction of time by 12-step involvement was significantly (ß = 0.00, p = .02), with greater 12-step involvement associated with fewer substance use consequences (Figure 2). The post-hoc test produced a solution of 6.6, indicating that at ~six and a half months posttreatment having greater 12-step involvement was no longer associated with fewer substance use consequences.

Table 4.

The effect of social support and spiritual well-being on substance use consequences from pre- to 12-months posttreatment.

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Intercept | 1.28 | 0.24 | 5.33 | <0.01 | 0.80 | 1.75 |

| Sex | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.80 | −0.46 | 0.59 |

| Time | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.31 | 0.19 | −0.01 | 0.06 |

| 12-Step involvement | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.42 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.99 |

| Spiritual well-being | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.02 | <0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Social support | −0.02 | 0.01 | −2.64 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.00 |

| Time*12-Step involvement | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.37 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Time*social support | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.22 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Time*spiritual well-being | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.47 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

Note: ß = beta coefficient, SE = standard error

Figure 2.

The effect of 12-step attendance on substance use consequences from pre- to 12-months posttreatment.

4. Discussion

This study tested the effect of two sources of recovery capital – social support and spiritual well-being – on substance use outcomes over 12 months of posttreatment recovery among a sample of primarily Black/AA adults. This study found that higher spiritual well-being was associated with lower substance use frequency until three and a half months posttreatment. Contrary to hypotheses, social support did not have a significant effect on substance use frequency nor substance use consequences. Higher 12-step involvement was associated with lower substance use consequences over time, but this association deteriorated by ~six and a half months in recovery. Together, these results support and extend recovery capital literature indicating that spiritual well-being is an important factor facilitative of posttreatment recovery among Black/AA adults particularly within the first three and a half months posttreatment. These findings also broaden our understanding on how sources of recovery capital may predict components of a more holistic appreciation of substance use recovery beyond substance use alone.

4.1. Spiritual well-being and substance use in recovery

The current findings support the association between spiritual well-being and posttreatment substance use during recovery. These findings are in line with growing literature indicating that spiritual well-being plays an important role in maintaining recovery from SUD (Dermatis & Galanter, 2016; Galanter et al., 2023; Robinson et al., 2011; Walton-Moss et al., 2013) and are particularly salient in the wake of a recent call by the International Society of Addiction Medicine to increase research focus on the role of spiritual well-being in recovery trajectories of adults with SUD (Galanter et al., 2021). Considering most studies on this topic among Black/AA individuals have focused on religiosity (Bowie et al., 2006; Hodge et al., 2021; Hope et al., 2017), these findings provide novel insight into the benefits of a more trait-like sense of connection and purpose, whether God-oriented or more existential in nature, among Black/AA adults in recovery. Of note, the Spiritual Wellbeing Scale incorporates both an existential component and a more religious, God-focused component. An existential sense of purpose and life meaning may overlap closely with quality of life, reported elsewhere as an important predictor of treatment outcomes among adults with SUDs (Rand et al., 2020; Tracy et al., 2012; Vederhus et al., 2016). In contrast, attachment to a God-like figure may more closely resemble the spirituality/religiosity constructs tested in other studies (Jaramillo et al., 2022; John F. Kelly et al., 2011; Klein et al., 2006; Walton-Moss et al., 2013). In this study, post-hoc tests found that neither subscale independently predicted substance use frequency, suggesting that the holistic definition of spiritual well-being may have a greater impact on successful recovery.

Research has more often focused on the role of spiritual well-being among those with chronic physical health conditions and serious illness (Balboni et al., 2022; Puchalski, 2004; Unantenne et al., 2013) and the role of spiritual well-being in predicting clinical outcomes for mental health conditions is scarce, thought to be due to bias from practitioners and the conflating of religion and spirituality (Longo & Peterson, 2002). These findings suggest that continued investigation on the role of spiritual well-being in mental health conditions may be fruitful. Furthermore, the current finding on the effect of spiritual well-being on substance use frequency above that of 12-step involvement is particularly meaningful given that 12-step is known to facilitate a sense of spiritual well-being (Dermatis & Galanter, 2016; Kelly et al., 2011) and is associated with abstinence (Johnson et al., 2006; Lookatch et al., 2019; Witbrodt & Kaskutas, 2005). This suggests that spiritual well-being has an impact on substance use over and above the spirituality gleaned from 12-step involvement in recovery. These findings contribute to the growing recovery capital literature informing alternative paths to recovery that do not necessarily include 12-step affiliation (Mawson et al., 2016; Parlier-Ahmad et al., 2021; Pettersen et al., 2019; Sánchez et al., 2020).

The current study found that the association between spiritual well-being and substance use frequency dissipated at three and a half months posttreatment. Early in posttreatment recovery individuals may face unique challenges such as transitions to new housing, employment, and social networks, which can bring about a variety of stressors. As people’s lifestyles shift through these transitions into recovery, it may be that different sources of recovery capital become more relevant. Indeed, various recovery capital components and sustained recovery are differentially associated at a one-year follow-up among adults in multiple stages of recovery (i.e., < six months, six −18 months, > three years) (Laudet & White, 2008). 12-step involvement and life meaning (i.e., the existential subscale of the spiritual well-being scale) predicted sustained recovery at one year later across all recovery groups. Yet sustained recovery was predicted by greater stress for those with under six months of recovery, greater 12-step involvement for those with six-18 months, and greater social support for those with > three years. In the current study, it is possible that other untested recovery capital factors had a greater impact on substance use after three and a half months posttreatment. Contrary to hypotheses the study found a significant negative association between spiritual well-being and substance use frequency at 11 months posttreatment. Other variables are likely contributing to this effect that we did not account for in the current analyses. Future studies may better elucidate the change in association between spiritual well-being and substance use outcomes by incorporating other factors playing a role in recovery at different stages.

The mechanisms accounting for the association between higher spiritual well-being and less frequent substance use remains untested. Among Black/AA men, spiritual well-being is described as a source of hope, strength, and peace that helps them feel less alone during difficult moments in recovery (Heinz et al., 2010) and among Black/AA women, spiritual well-being is associated with more positive coping strategies and better family relationships (Brome et al., 2000). Studies outside of SUD literature indicate that emotion regulation mediates the association between spiritual well-being and mental health (Akbari & Hossaini, 2018), and health-related behaviors mediates the association between spiritual well-being and psychological well-being (Bożek et al., 2020). Further, adolescents’ meaning making of situations mediates the association between spiritual well-being and coping with stress (Krok, 2015). SUD recovery is characterized by multiple challenges and stressors; spiritual well-being may support recovery by providing a sense of meaning that helps facilitate effective coping skills such as emotion regulation (Laudet et al., 2006; Worley, 2020).

4.2. Social support

In this sample, social support did not emerge as a predictor of substance use frequency nor associated consequences over time during the recovery period. While social support is considered an important source of recovery capital (Dobkin et al., 2002; Havassy et al., 1991; Kahle et al., 2020), research suggests the variable nature of this construct. For example, the benefits gleaned from social support in aiding recovery may depend on the relationship type and their support for abstinence (Asta et al., 2021; Goehl et al., 1993; Manuel et al., 2007). Shifts from substance use-oriented social networks to recovery-oriented networks characterize successful recovery (Bathish et al., 2017) and is a predictor of decreased substance use (Longabaugh et al., 2010). Among participants in treatment for alcohol use, higher general and abstinence-specific social support significantly predicts lower alcohol use three months posttreatment, but only abstinence-specific social support predicts reductions in alcohol use > one year posttreatment (Beattie & Longabaugh, 1999). In a qualitative study of women’s experiences with social support in SUD recovery, 11 social support themes emerged as important in sustaining recovery, yet only “sobriety support” was explicitly related to maintaining sobriety (Tracy et al., 2010). In the current sample, it is possible that reporting on general social support without specifying whether this support is oriented toward participant’s abstinence decreased the likelihood of detecting a significant relationship between social support and posttreatment recovery outcomes. In the study referenced previously (Laudet & White, 2008), social support predicted sustained recovery only for those with >3 years of recovery at baseline. It may be that general social support, versus abstinence specific, becomes more important in sustaining recovery once individuals have maintained stable recovery for several years. Furthermore, given the significant effect found for 12-step involvement, it may be that when accounting for 12-step involvement the additional effect of social support on substance use outcomes was negligible.

4.3. 12-step involvement and substance use consequences in recovery

The present study sought to test the impact of recovery capital on substance use consequences in addition to substance use in efforts to conceptualize SUD recovery in line with a more wholistic working definition (SAMHSA, 2012; Ashford et al., 2019; Best et al., 2016). While the study found neither spiritual well-being nor social support to be associated with substance use consequences, higher 12-step involvement was associated with fewer substance use consequences from pretreatment until ~six and a half months posttreatment. This finding supports prior research demonstrating an association between 12-step involvement and decreased adverse effects of substance use (Banerjee et al., 2007) and improved quality of life during recovery (Laudet et al., 2006). The association between 12-step involvement and lower substance use consequences may be due to 12-step providing access to sources of recovery capital including more friends (general and abstinence-specific) (Humphreys et al., 1999), greater self-efficacy (Kelly et al., 2002; Morgenstern et al., 1997), and effective coping skills (Humphreys et al., 1999; Kelly et al., 2002; Morgenstern et al., 1997; Timko et al., 2005).

The lack of association between 12-step involvement and substance use frequency is in line with randomized clinical trials testing the efficacy of 12-step on substance use showing mixed results (Allen et al., 1998; Bogenschutz et al., 2014; Kelly et al., 2017; Timko et al., 2005; Walsh et al., 1991). Further, some evidence suggests that 12-step engagement, defined as active participation in 12-step community activities, but not attendance, predicts changes in substance use during recovery (Weiss et al., 2005). This may help explain the present findings, where 12-step attendance alone may provide sources of recovery capital to cope with the consequences associated with substance use but is not enough to predict changes in substance use frequency. Thus, while 12-step itself can be considered a source of recovery capital and/or connects individuals to other sources of recovery capital, the present findings suggest the importance of cultivating sources of recovery capital – specifically, spiritual well-being – distinct from 12-step involvement. These findings have implications including potentially encouraging clinicians and treatment providers to go beyond 12-step alone as adequate “after care” posttreatment and help patients broaden their repertoire of sources of recovery capital relevant to the patient’s life. Qualitative research that highlights individuals’ experiences of 12-step, the degree to which it provides sources of recovery capital (including and in addition to spiritual well-being and social support), and the impact of other sources of recovery capital on their recovery over time may be valuable.

4.4. The role of recovery capital among Black/AA adults

This study focused on a primarily Black/AA sample of adults in SUD treatment. Black/AA individuals are at a disproportionate risk of dropping out of SUD treatment (Mennis & Stahler, 2016; Saloner & Lê Cook, 2013), returning to use (Chartier & Caetano, 2010), and experiencing negative consequences of their use compared to white individuals such as higher rates of incarceration and violence (Cooper, 2015; Dunlap & Johnson, 1992; Edwards et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 2018). These disparities are thought to be due to systemic racism and inequity in the healthcare system for Black/AA individuals (Matsuzaka & Knapp, 2020), including the War on Drugs that has disproportionately targeted Black/AA communities (Cooper, 2015). This study indicates that high levels of spiritual well-being and 12-step involvement are beneficial for navigating substance use and associated consequences, respectively, across early months of posttreatment recovery for Black/AA adults. More research is needed to identify the mechanisms of these recovery capital components on outcomes for Black/AA adults and increase individual’s contact with these resources.

4.5. Strengths and limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the current study was a secondary analysis of an existing dataset, thus the variables of interest were not collected for the current study aims. Study measures of social support, spiritual well-being, and 12-step involvement may have impacted results. The MOS Social Support survey does not specify whether social support is abstinence or recovery specific, which may reduce the likelihood of finding an association between social support and lower substance use outcomes. While post-hoc analyses probed the respective effects of religious and existential subscales of spiritual well-being, further study into the respective importance of these two components of spiritual well-being in maintaining recovery is needed. 12-step involvement accounted only for meeting attendance but not engagement in 12-step content; further, it is unclear to what degree 12-step involvement facilitated sources of recovery capital. While this study acknowledged this latter consideration by controlling for 12-step involvement, it will be informative to test the degree to which adults glean recovery capital from 12-step versus from various external sources.

Lastly, when studying the association between study variables among marginalized racial groups, it is important to include constructs relevant to the importance of race as a study variable such as race-related stress or perceived discrimination. While this study provided support for the association between spiritual well-being and substance use among Black/AA adults, studies including race-related stress or perceived discrimination as predictors can test whether spiritual well-being is directly buffering against the impact of those constructs on substance use.

Despite limitations, the current study has several strengths. This study tested aims among a sample of Black/AA adults across 12-months post-SUD treatment. Few studies have tested recovery capital predictors on longitudinal substance use outcomes among non-white samples and this study contributes findings on posttreatment outcome research among an underrepresented and marginalized racial group. This study also used a rigorous statistical approach to test the impact of time-varying predictors on time-varying outcomes, accounting for autocorrelation of within-subject repeated measures with count outcomes. Post-hoc identification of when in posttreatment recovery the associations between predictors and outcomes change is also a notable contribution.

4.6. Conclusion

The current study confirmed the impact of spiritual well-being on recovery outcomes, above the effect of 12-step involvement, yet did not support an effect of social support on neither substance use outcomes. The current study has important implications for clinical settings to improve long-term outcomes among low-income Black and African American adults entering substance use treatment. For example, future work may test the extent to which recovery is improved by incorporating a more holistic perspective in which patients identify and increase access to sources of recovery capital such as spiritual well-being, in addition to or outside of 12-step involvement. It will be valuable for future work to incorporate both quantitative and qualitative assessment of how the effect of various sources of recovery capital shift during different stages in recovery.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Social support and spiritual wellbeing are important sources of recovery capital among Black/African American adults

Higher spiritual wellbeing was associated with lower substance use frequency while accounting for 12-step involvement

Treatment settings may improve substance use outcomes by helping patients increase spiritual wellbeing beyond 12-step involvement

Funding

Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 DA026424.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Drug Abuse R01DA026424 (NCT01189552).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presentations

An abstract based on this work was presented at the Collaborate Perspectives on Addiction conference, Portland, OR, April 2022.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Materials and analysis code for this study are not publicly available. We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- (SAMHSA), S. A. and M. H. S. A. (2012). SAMHSA Working Definition of Recovery: 10 Guiding Principles of Recovery. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/pep12-recdef.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- Acevedo A, Garnick DW, Lee MT, Horgan CM, Ritter G, Panas L, Davis S, Leeper T, Moore R, & Reynolds M (2012). Racial/Ethnic Differences in Substance Abuse Treatment Initiation and Engagement. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 11(1), 1–17. 10.1080/15332640.2012.652516.Racial/Ethnic [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbari M, & Hossaini SM (2018). The relationship of spiritual health with quality of life, mental health, and burnout: The mediating role of emotional regulation. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 13(1), 22–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldwin CM, Park CL, Jeong YJ, & Nath R (2014). Differing pathways between religiousness, spirituality, and health: A self-regulation perspective. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6(1), 9–21. 10.1037/a0034416 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J, Anton RF, Babor TF, Carbonari J, Carroll KM, Connors GJ, Cooney NL, Del Boca FK, DiClemente CC, Donovan D, Kadden RM, Litt M, Longabaugh R, Mattson M, Miller WR, Randall CL, Rounsaville BJ, Rychtarik RG, Stout RL, … Zweben A (1998). Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 22(6), 1300–1311. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP (2005). Measuring Outcome in Interventions for Alcohol Dependence and Problem Drinking: Executive Summary of a Conference Sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 27(10), 1657–1660. 10.1097/01.ALC.0000091223.72517.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5. 10.5555/appi.books.9780890425596.x00pre [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ashford RD, Brown A, Brown T, Callis J, Cleveland HH, Eisenhart E, Groover H, Hayes N, Johnston T, Kimball T, Manteuffel B, McDaniel J, Montgomery L, Philips S, Polacek M, Statman M, & Whitney J (2019). Defining and operationalizing the phenomena of recovery: A working definition from the Recovery Science Research Collaborative. Addiction Research and Theory, 27(3), 179–188. 10.1080/16066359.2018.1515352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asta D, Davis A, Krishnamurti T, Klocke L, Abdulla W, & Krans EE (2021). The influence of social relationships on substance use behaviors among pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 222(November 2020), 108665. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balboni TA, Vanderweele TJ, Doan-Soares SD, Long KNG, Ferrell BR, Fitchett G, Koenig HG, Bain PA, Puchalski C, Steinhauser KE, Sulmasy DP, & Koh HK (2022). Spirituality in Serious Illness and Health. Jama, 328(2), 184–197. 10.1001/jama.2022.11086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee K, Howard M, Mansheim K, & Beattie M (2007). Comparison of health realization and 12-step treatment in women’s residential substance abuse treatment programs. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 33(2), 207–215. 10.1080/00952990601174758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathish R, Best D, Savic M, Beckwith M, Mackenzie J, & Lubman DI (2017). “Is it me or should my friends take the credit?” The role of social networks and social identity in recovery from addiction. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 47(1), 35–46. 10.1111/jasp.12420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie MC, & Longabaugh R (1999). General and alcohol-specific social support following treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 24(5), 593–606. 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00120-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best D, Beckwish M, Haslam C, Haslam AS, Jetten J, Mawson E, & Lubman DI (2016). Overcoming alcohol and other drug addiction as a process of social identity transition: The social identity model of recovery (SIMOR). Addiction Research and Theory, 24(2), 111–123. 10.3109/16066359.2015.1075980 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard KA, Morgenstern J, Morgan TJ, Labouvie EW, & Bux DA (2003). Assessing Consequences of Substance Use: Psychometric Properties of the Inventory of Drug Use Consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17(4), 328–331. 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume AW, Schmaling KB, & Marlatt GA (2006). Recent drinking consequences, motivation to change, and changes in alcohol consumption over a three month period. Addictive Behaviors, 31(2), 331–338. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogenschutz MP, Rice SL, Tonigan JS, Vogel HS, Nowinski J, Hume D, & Arenella PB (2014). 12-STEP FACILITATION FOR THE DUALLY DIAGNOSED: A RANDOMIZED CLINICAL TRIAL. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(4), 403–411. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.12.009.12-STEP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond J, Kaskutas LA, & Weisner C (2003). The persistent influence of social networks and Alcoholics Anonymous on abstinence. J Stud Alcohol, 64(4), 579–588. 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie JV, Ensminger ME, & Robertson JA (2006). Alcohol-Use Problems in Young Black Adults: Effects of Religiosity, Social Resources, and Mental Health. J Stud Alcohol, 67(1), 44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bożek A, Nowak PF, & Blukacz M (2020). The Relationship Between Spirituality, Health-Related Behavior, and Psychological Well-Being. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(August). 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Vidrine JI, & Litvin EB (2007). Relapse and relapse prevention. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 257–284. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brome DR, Owens MD, Allen K, & Vevaina T (2000). An Examination of Spirituality among African American Women in Recovery from Substance Abuse. Journal of Black Psychology, 26(4), 470–486. 10.1177/0095798400026004008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bufford RK, Paloutzian RF, & Ellison GW (1991). Norms for the Spiritual Well-Being Scale. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 19(1), 56–70. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess BE, Mrug S, Bray LA, Leon KJ, & Troxler RB (2021). Predicting Substance Use from Religiosity/Spirituality in Individuals with Cystic Fibrosis. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(3), 1818–1831. 10.1007/s10943-020-01119-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttram ME, Kurtz SP, & Surratt HL (2013). Substance Use and Sexual Risk Mediated by Social Support Among Black Men. Journal of Community Health, 38, 62–69. 10.1007/s10900-012-9582-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, & Caetano R (2010). Ethnicity and Health Disparities in Alcohol Research. Alcohol Research and Health, 33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney AM, Booth BM, Borders TF, & Curran GM (2017). The Role of Social Capital in African Americans’ Attempts to Reduce and Quit Cocaine Use. Substance Use and Misuse, 51(6), 777–787. 10.3109/10826084.2016.1155606.The [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisler RA (2005). Assessing nondrinking outcomes in combined pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy clinical trials for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud W, & Granfield R (2008). Conceptualizing recovery capital: Expansion of a theoretical construct. Substance Use and Misuse, 43(12–13), 1971–1986. 10.1080/10826080802289762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HL (2015). War on Drugs Policing and Police Brutality. Substance Use and Misuse, 50(8–9), 1188–1194. 10.3109/10826084.2015.1007669.War [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Magidson JF, Anand D, Seitz-Brown CJ, Chen Y, & Baker S (2018). The effect of a behavioral activation treatment for substance use on post-treatment abstinence: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 113(3), 535–544. 10.1111/add.14049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermatis H, & Galanter M (2016). The Role of Twelve-Step-Related Spirituality in Addiction Recovery. Journal of Religion and Health, 55, 510–521. 10.1007/s10943-015-0019-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin PL, De Civita M, Paraherakis A, & Gill K (2002). The role of functional social support in treatment retention and outcomes among outpatient adult substance abusers. Addiction, 97, 347–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap E, & Johnson BD (1992). The Setting for the Crack Era: Macro Forces, Micro Consequences (1960–1992). Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 24(4), 307–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant A (2005). African-American alcoholics: an interpretive/constructivist model of affiliation with alcoholics anonymous (AA). Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 4(1), 5–21. 10.1300/J233v04n01_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards E, Greytak E, Madubuonwu B, Sanchez T, Beiers S, Resing C, Fernandez P, & Galai S (2020). A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform.

- Fehring RJ, Brennan PF, & Keller ML (1987). Psychological and spiritual well-being in college students. Research in Nursing & Health, 10(6), 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Heather N, Murphy JG, Stafford T, Tucker JA, & Witkiewitz K (2019). Recovery From Addiction: Behavioral Economics and Value-Based Decision Making. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 34(1), 182–193. 10.1037/adb0000518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, & Gibbon M (2004). The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II). In Hilsenroth MJ & Segal DL (Eds.), Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment, vol 2: Personality Assessment (pp. 134–143). John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn PM, Joe GW, Broome KM, Simpson DD, & Brown BS (2003). Looking Back on Cocaine Dependence : Reasons for Recovery. The American Journal on Addictions, 12, 398–412. 10.1080/10550490390240774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter M, Hansen H, & Potenza MN (2021). The role of spirituality in addiction medicine: a position statement from the spirituality interest group of the international society of addiction medicine. Substance Abuse, 42(3), 269–271. 10.1080/08897077.2021.1941514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter M, White WL, Khalsa J, & Hansen H (2023). A scoping review of spirituality in relation to substance use disorders: Psychological, biological, and cultural issues. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 0(0), 1–9. 10.1080/10550887.2023.2174785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppert C, Bogenschutz MP, & Miller WR (2007). Development of a bibliography on religion, spirituality and addictions. Drug and Alcohol Review, 26(4), 389–395. 10.1080/09595230701373826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehl L, Nunes E, Quitkin F, & Hilton I (1993). Social networks and methadone treatment outcome: The costs and benefits of social ties. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 19(3), 251–262. 10.3109/00952999309001617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai AH, Franklin C, Park S, DiNitto DM, & Aurelio N (2019). The efficacy of spiritual/religious interventions for substance use problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 202(February), 134–148. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härd S, Best D, Sondhi A, Lehman J, & Riccardi R (2022). The growth of recovery capital in clients of recovery residences in Florida, USA: a quantitative pilot study of changes in REC-CAP profile scores. Substance Abuse: Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 17(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s13011-022-00488-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havassy BE, Hall SM, & Wasserman DA (1991). Social support and relapse: Commonalities among alcoholics, opiate users, and cigarette smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 16(5), 235–246. 10.1016/0306-4603(91)90016-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearld KR, Badham A, & Budhwani H (2017). Statistical Effects of Religious Participation and Marriage on Substance Use and Abuse in Racial and Ethnic Minorities. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(4), 1155–1169. 10.1007/s10943-016-0330-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz AJ, Wu J, Witkiewitz K, Epstein DH, & Preston KL (2010). Marriage and Relationship Closeness as Predictors of Cocaine and Heroin Use. Addictive Behaviors, 34(3), 258–263. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy EA (2017). Recovery capital: a systematic review of the literature. Addiction Research and Theory, 25(5), 349–360. 10.1080/16066359.2017.1297990 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorthøj CR, Hjorthøj AR, & Nordentoft M (2012). Validity of Timeline Follow-Back for self-reported use of cannabis and other illicit substances - Systematic review and meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 37(3), 225–233. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge DR, Wu S, Wu Q, Marsiglia FF, & Chen W (2021). Religious service attendance typologies and African American substance use : a longitudinal study of the protective effects among young adult men and women. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56, 1859–1869. 10.1007/s00127-021-02029-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope MO, Assari S, Cole-lewis YC, & Caldwell CH (2017). Religious Social Support, Discrimination, and Psychiatric Disorders Among Black Adolescents. Race and Social Problems, 9(2), 102–114. 10.1007/s12552-016-9192-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Mankowski ES, Moos RH, & Finney JW (1999). Do enhanced friendship networks and active coping mediate the effect of self-help groups on substance abuse? Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 21(1), 54–60. 10.1007/BF02895034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo Y, DeVito EE, Frankforter T, Silva MA, Añez LM, Kiluk BD, Carroll KM, & Paris M (2022). Religiosity and Spirituality in Latinx Individuals with Substance Use Disorders: Association with Treatment Outcomes in a Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Religion and Health, 0123456789. 10.1007/s10943-022-01544-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Finney JW, & Moos RH (2006). End-of-treatment outcomes in cognitive-behavioral treatment and 12-step substance use treatment programs: Do they differ and do they predict 1-year outcomes? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 31(1), 41–50. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle EM, Veliz P, Mccabe SE, & Boyd CJ (2020). Functional and structural social support, substance use and sexual orientation from a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. Addiction, 115(3), 546–558. 10.1111/add.14819.Functional [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly John F., Kaminer Y, Kahler CW, Hoeppner B, Yeterian J, Cristello JV, & Timko C (2017). A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial Testing Integrated Twelve-Step Facilitation (iTSF) Treatment for Adolescent Substance Use Disorder. Addiction, 112(12), 2155–2166. 10.1111/add.13920.A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly John F., Meyers MG, & Brown SA (2002). Do Adolescents Affiliate with 12-Step Groups? A Multivariate Process Model of Effects. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63, 293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly John F., Stout RL, Magill M, Tonigan JS, & Pagano ME (2011). Spirituality in Recovery: A Lagged Mediational Analysis of Alcoholics Anonymous’ Principal Theoretical Mechanism of Behavior Change. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 35(3), 454–463. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01362.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly John F, Stout RL, Magill M, & Tonigan JS (2011). The role of Alcoholics Anonymous in mobilizing adaptive social network changes: A prospective lagged mediational analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 114, 119–126. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.009.The [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly John Francis, Magill M, & Stout RL (2009). How do people recover from alcohol dependence? A systematic review of the research on mechanisms of behavior change in Alcoholics Anonymous. Addiction Research and Theory, 17(3), 236–259. 10.1080/16066350902770458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Schwartz RP, Peterson JA, Wilson ME, & Brown BS (2010). The relationship of social support to treatment entry and engagement: The community assessment inventory. Substance Abuse, 31(1), 43–52. 10.1080/08897070903442640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Dreifuss JA, Weiss RD, Morgenstern J, & Carroll KM (2013). The Short Inventory of Problems – Revised (SIP-R): Psychometric properties within a large, diverse sample of substance use disorder treatment seekers. Psychol Addict Behav, 27(1), 307–314. 10.1037/a0028445.The [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Fitzmaurice GM, Strain EC, & Weiss RD (2020). What Defines a Clinically Meaningful Outcome in the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders: Reductions in Direct Consequences of Drug Use or Improvement in Overall Functioning? 114(1), 9–15. 10.1111/add.14289.What [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H, Elifson KW, & Sterk CE (2006). The Relationship between Religiosity and Drug Use among ‘“ At Risk ”‘ Women. Journal of Religion and Health, 45(1), 40–56. 10.1007/s10943-005-9005-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krentzman AR, Farkas KJ, & Townsend AL (2010). Spirituality, Religiousness, and Alcoholism Treatment Outcomes: A Comparison between Black and White Participants. Alcohol Treat Q, 28(2). 10.1080/07347321003648661.Spirituality [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krok D (2015). Religiousness, spirituality, and coping with stress among late adolescents: A meaning-making perspective. Journal of Adolescence, 45, 196–203. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis BJ (1995). Uncertainty, Spiritual Well-Being, and Psychosocial Adjustment to Chronic Illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 17(3), 217–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB, Morgen K, & White WL (2006). The role of social supports, spirituality, religiousness, life meaning and affiliation with 12-step fellowships in quality of life satisfaction among individuals in recovery from alcohol and drug problems. Spirituality and Religiousness and Alcohol/Other Drug Problems: Treatment and Recovery Perspectives, 24(1), 33–73. 10.1300/J020v24n01_04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB, & White WL (2008). Recovery Capital as Prospective Predictor of Sustained Recovery, Life satisfaction and Stress among former poly-substance users. Substance Use and Misuse, 43(1), 27–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B, Hoffman L, Garcia CC, & Nixon SJ (2018). Race and Socioeconomic Status in Substance Use Progression and Treatment Entry. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 17(2), 150–166. 10.1080/15332640.2017.1336959.Race [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Philip WW, William HZ, & Stephanie SOM (2010). Network support as a prognostic indicator of drinking outcomes: The COMBINE study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71(6), 837–846. 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo DA, & Peterson SM (2002). The role of spirituality in psychosocial rehabilitation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(4), 333–340. 10.1037/h0095004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lookatch SJ, Wimberly AS, & McKay JR (2019). Effects of social support and 12-Step involvement on recovery among people in continuing care for cocaine dependence. Substance Use and Misuse, 54(13), 2144–2155. 10.1080/10826084.2019.1638406.Effects [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna N, Gail Horton E, Sherman D, & Malloy T (2017). Exploring the Psychometric Properties of the Spiritual Well-Being Scale Among Individuals with Substance Use Disorders. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15(4), 826–841. 10.1007/s11469-017-9771-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manuel JK, McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Cook S, & Tonigan JS (2007). The pretreatment social networks of women with alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(6), 871–878. 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason SJ, Deane FP, Kelly PJ, & Crowe TP (2009). Do spirituality and religiosity help in the management of cravings in substance abuse treatment? Substance Use and Misuse, 44(13), 1926–1940. 10.3109/10826080802486723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew RJ, Georgi J, Wilson WH, & Mathew VG (1996). A retrospective study of the concept of spirituality as understood by recovering individuals. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 13(1), 67–73. 10.1016/0740-5472(95)02022-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaka S, & Knapp M (2020). Anti-racism and substance use treatment: Addiction does not discriminate, but do we? Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 19(4), 567–593. 10.1080/15332640.2018.1548323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DA, & Larson DB (1995). The Faith factor: An annotated bibliography of clinical research on spiritual subject, Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mawson E, Best D, & Lubman DI (2016). Associations between social identity diversity, compatibility, and recovery capital amongst young people in substance use treatment. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 4, 70–77. 10.1016/j.abrep.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR (2017). Making the hard work of recovery more attractive for those with substance use disorders. Addiction, 112(5), 751–757. 10.1111/add.13502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, & Kleber HD (2001). Drug dependence as a chronic medical illness. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association, 285(4), 409. 10.1001/jama.285.4.409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mennis J, & Stahler GJ (2016). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Outpatient Substance Use Disorder Treatment Episode Completion for Different Substances. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 63, 25–33. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd Editio). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Labouvie E, McCrady BS, Kahler CW, & Frey RM (1997). Affiliation with alcoholics anonymous after treatment: A study of its therapeutic effects and mechanisms of action. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 768–777. 10.1037/0022-006X.65.5.768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paloutzian RF, & Ellison CW (1982). The Spiritual Well-being Scale. Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy, 429. [Google Scholar]

- Parlier-Ahmad AB, Terplan M, Svikis DS, Ellis L, & Martin CE (2021). Recovery capital among people receiving treatment for opioid use disorder with buprenorphine. Harm Reduction Journal, 18(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12954-021-00553-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen H, Landheim A, Skeie I, Biong S, Brodahl M, Oute J, & Davidson L (2019). How Social Relationships Influence Substance Use Disorder Recovery: A Collaborative Narrative Study. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 13. 10.1177/1178221819833379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont RL (2004). Spiritual Transcendence as a Predictor of Psychosocial Outcome From an Outpatient Substance Abuse Program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(3), 213–222. 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchalski C (2004). Spirituality in health: The role of spirituality in critical care. Critical Care Clinics, 20(3), 487–504. 10.1016/j.ccc.2004.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand K, Arnevik EA, & Walderhaug E (2020). Quality of life among patients seeking treatment for substance use disorder, as measured with the EQ-5D-3L. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes, 4(92). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson EAR, Krentzman AR, Webb JR, & Brower KJ (2011). Six-Month Changes in Spirituality and Religiousness in Alcoholics Predict Drinking Outcomes at Nine Months *. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, July, 660–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner B, & Lê Cook B (2013). Blacks And Hispanics Are Less Likely Than Whites To Complete Addiction Treatment, Largely Due To Socioeconomic Factors. Health Aff (Millwood), 32(1), 135–145. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0983.Blacks [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez J, Sahker E, & Arndt S (2020). Addictive Behaviors The Assessment of Recovery Capital (ARC) predicts substance abuse treatment completion. Addictive Behaviors, 102. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, & Stewart AL (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine, 32(6), 705–714. 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, & Sobel MB (1990). Timeline Follow-Back. 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens E, Jason LA, Ram D, & Light J (2015). Investigating Social Support and Network Relationships in Substance Use Disorder Recovery. Substance Abuse, 36(4), 396–399. 10.1080/08897077.2014.965870.Investigating [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological summary and definitions. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. SAMHSA. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C (2008). Outcomes of AA for special populations. In Galanter M, Kaskutas LA, Borkman T, Zemore SE, & Tonigan JS (Eds.), Recent Developments in Alcoholism Research on Alcoholics Anonymous and Spirituality in Addiction Recovery (Vol. 18, pp. 373–392). American Society of Addiction Medicine. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Finney JW, & Moos RH (2005). The 8-year course of alcohol abuse: Gender differences in social context and coping. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(4), 612–621. 10.1097/01.ALC.0000158832.07705.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy EM, Laudet AB, Min MO, Kim HS, Brown S, Jun MK, & Singer L (2012). Prospective patterns and correlates of quality of life among women in substance abuse treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 124(3), 242–249. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy EM, Munson MR, Peterson LT, & Floersch JE (2010). Social support: A mixed blessing for women in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 10(3), 257–282. 10.1080/1533256X.2010.500970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unantenne N, Warren N, Canaway R, & Manderson L (2013). The Strength to Cope: Spirituality and Faith in Chronic Disease. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(4), 1147–1161. 10.1007/s10943-011-9554-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan F, Wittine B, & Walsh R (1998). Transpersonal psychology and the religious person. In Shafranske EP (Ed.), Religion and the clinical practice of psychology (pp. 483–509). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Vederhus J, Pripp AH, & Clausen T (2016). Quality of Life in Patients with Substance Use Disorders Admitted to Detoxification Compared with Those Admitted to Hospitals for Medical Disorders : Follow-Up Results. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 10, 31–37. 10.4137/SART.S39192.TYPE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]