Abstract

Background

Improving quality of care provided to short-stay patients with dementia in nursing homes is a policy priority. However, it is unknown whether dementia-focused care strategies are associated with improved clinical outcomes or lower utilization and costs for short-stay dementia patients.

Methods

We performed a national survey of nursing home administrators in 2020–2021, asking about the presence of three dementia-focused care services used for their short-stay patients: (1) a dementia care unit; (2) cognitive deficiency training for staff; and (3) dementia-specific occupational therapy. Using Medicare claims, we identified short-stay episodes for beneficiaries residing in surveyed skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) with and without dementia. We compared clinical, cost, and utilization outcomes for dementia patients in SNFs which did and did not offer dementia-focused care services. As a counterfactual control, we compared these differences to those for non-dementia patients in the same facilities. Our primary quantity of interest was an interaction term between a patients’ dementia status and the presence of a dementia-focused care tool.

Results

The study population included 102,860 Medicare episodes of care from 377 SNF survey respondents in 2018–2019. In adjusted comparisons of the interaction between dementia status and presence of each dementia-focused care tool, dementia care units were associated with a 1.5 day increase in healthy days at home in the 90-days following discharge (p=0.01) and a 3.1% decrease in the likelihood of a subsequent SNF admission (p=0.001). Cognitive deficiency training was also associated with a 2.0% increase in antipsychotics (p=0.03) while dementia-specific occupational therapy was associated with a 1.2% increase in falls (p=0.01) per patient-episode.

Conclusions

Self-reported use of dementia care units for short-stay patients was associated with modestly better performance in some, but not all, outcome measures. This provides hypothesis-generating evidence that dementia care units could be a promising mechanism to improve care delivery in nursing homes.

Keywords: dementia, short-stay patients, nursing home

Introduction

Over 30% of short-stay patients in U.S. nursing homes have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia,1 conditions that are associated with greater risk of adverse outcomes and higher costs of care.2 Improving the quality of care provided to this population in nursing homes has been a policy priority for decades.3,4 Nursing home quality is a critical facet of the health care system for older Americans given that by the time an individual reaches age 80, approximately 75% of those diagnosed with dementia will reside in a nursing home compared to just 4% in the general population.3 However, providing care for patients with dementia is difficult given patients’ cognitive and communicative impairments, including disruptive behaviors such as wandering, agitation, and aggression.5 This may contribute to significant rates of low-value care in nursing homes such as overuse of antipsychotics, feeding tubes, and high rates of avoidable hospitalization.6,7

Person-centered dementia care is a promising approach to improve quality that emphasizes the use of non-pharmacological interventions such as consistent staff assignments, increased exercise or time spent outdoors, management of acute and chronic pain, and incorporation of personalized activities.4,8 Person-centered dementia care also includes investment in specialized nursing home beds known as dementia “special care units,” defined as a dedicated unit, wing, or floor in a nursing home specially designed, staffed, and programmed to provide a supportive social and physical environment for individuals with dementia.3,6 These units can include additional features not typically found in a traditional nursing home, such as noise reduction programs, use of private rooms or smaller unit sizes, and provision of increased natural light.9 They are also designed to promote patient safety, decrease the use of physical restraints and antipsychotic medication, and provide more flexible patient routines.10,11

Prior efforts have primarily focused on the use of special care units for long-term care, with research finding that dementia special care units were associated with improved quality of life,10,12 better social interaction and integration,13 and lower hospitalization rates.6 Evidence is mixed on the association with clinical outcomes, such as physical restraints, feeding tubes, and use of antipsychotics, for long-stay patients.6,14 However, it is unclear whether dementia special care units are associated with improved outcomes for patients with dementia because of the unique features of the unit or the result of having additional and better trained staff.10,15 Additionally, there is little research on how special care units might be used for short-stay skilled nursing facility (SNF) patients. Less is also known about the use of other dementia-focused care for short-stay patients, such as dementia-focused occupational therapy and staff trainings to care for patients with cognitive deficiency, as recommended by the Alzheimer’s Association.16

We performed a national survey of U.S. SNFs linked with Medicare claims to test the hypothesis that the use of dementia-focused care in nursing homes would be associated with lower cost and improved clinical outcomes for short-stay patients with dementia.

Methods

Survey Administration

We conducted a national survey of U.S. SNFs to understand their care delivery approaches and perceived barriers to reducing spending or improving care, specifically targeting services used for SNF short-stay patients; details of survey administration have been published previously.17 Briefly, the survey was designed by researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH) and Washington University in St. Louis and was conducted from October 15, 2020 to May 16, 2021. Facilities were contacted by a survey firm using a sequential mixed mode approach through mail, web, and telephone. Along with a personalized pre-notification form explaining the study and sponsorship, a $100 check was sent as a financial incentive for the individual completing the survey (e.g., Executive Director or Nurse Administrator) at the facility. We obtained survey responses from 377 SNFs out of a sample of 693 for a 54% response rate (377/693). Although the survey focused broadly on the current care delivery approaches and barriers to reduce spending or improve care used by SNFs for their short-stay patients, it also included three dementia-focused care questions. SNFs were asked whether the following tools or strategies were currently used for their short-stay residents: (1) a specific physical unit for short-stay patients with dementia (referred to as a “special care unit” in prior literature); (2) cognitive deficiency training for staff; and (3) dementia-specific occupational therapy (full survey instrument available in Supplementary Survey S1). Among survey respondents, the item-response rate for the dementia-focused care questions was 358 out of 377 SNFs (95% item response rate). This study was approved as exempt from review by HSPH’s Institutional Review Board.

Survey Data Linkage

We linked survey data with 2018–2019 Medicare fee-for-service claims for Medicare beneficiaries with and without dementia residing in SNFs which responded to our survey to identify our sample and clinical outcomes, such as readmission rates and healthy days at home. We also used 2018–2019 nursing home resident assessment information from the Minimum Data Set 3.0 to identify additional quality outcomes.18 We obtained patient characteristics from the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File,19 facility characteristics from the Certification and Survey Provider Enhanced Reporting System (CASPER)20 and Nursing Home Care Compare,21 and county characteristics from the Area Health Resource File.22

Study Sample

Our sample included Medicare beneficiaries aged 18 and older who were continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B for their entire episode of care (defined below). We identified beneficiaries who had been discharged in the previous 30 days from an acute care hospital to a SNF survey respondent using Medicare Part A SNF claims (N SNFs=377; N patients=102,860). The short-stay episode began at hospital discharge and included the subsequent 90 days in the SNF,23 with some outcomes measured 90-days post-admission to the SNF (e.g., mortality) and others measured at 90-days post-discharge from the SNF.

We identified patients with dementia based on validated ICD-10 diagnosis codes24 within the previous year in Medicare inpatient and outpatient claims.

Study Exposures

Our key exposure was the presence of any of three dementia-focused care services used for short-stay patients: a dementia care unit, cognitive deficiency training, and dementia occupational therapy. Survey respondents were provided with the following instructions:

“Below is a list of initiatives focused on patients with cognitive impairment or dementia that SNFs might pursue. Please indicate whether each tool or strategy is currently used by your SNF for short-stay residents. Please record a response for each item below” (Supplementary Survey S1, Question 7). Respondents were asked if they offered a dementia care unit, such as a specific physical unit, for their short-stay residents with dementia. While a facility might use a dementia care unit for multiple purposes, we found that 85% of surveyed facilities reported using a dementia care unit for both their short and long-stay patients.

The cognitive deficiency training survey question asked whether the facility utilized special training for staff caring for patients with cognitive decline. This specialized training could involve learning to take an assessment of a resident’s cognitive ability, provide tailored care planning, and determine targeted strategies for addressing patient’s behavioral and communication challenges.16

The final dementia-focused survey question asked whether facilities provided enhanced occupational therapy for patients with dementia, such as a kitchen simulation environment. Occupational therapy can help residents engage in skill-appropriate activities to improve their physical and mental health as well as their ability to perform activities of daily living, such as bathing, mobility, and eating.16,25 In addition to analyzing each dementia-focused care tool individually, we also created combinations of these measures (any two of the dementia-focused care tools used or all three tools used).

Study Outcomes

We measured cost (based on the total standardized payments by Medicare Part A and Part B) and measures of utilization within 90-days of discharge from the SNF, including hospital readmission rate, healthy days at home,26 and emergency department visit rate. As a sensitivity analysis, we also included measures of the hospital readmission rate and emergency department visit rate measured within 90 days of discharge from the hospital. We also calculated the likelihood of a subsequent SNF admission and length of stay (Medicare covered days, non-Medicare covered days, and cumulative length of stay). Clinical outcomes included 90-day post-admission mortality rate as well as antipsychotic use, pressure ulcers, falls, and physical restraints (Table S1). The use of antipsychotics, pressure ulcers, falls, and restraints are all included as quality measures on CMS’ Nursing Home Care Compare website.27

Study Covariates

Patient characteristics obtained from Medicare claims included age, sex, race and ethnicity (white, Black, Hispanic, or other) and indicators for dual-eligibility status (eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid) and disability status (based on the reason for Medicare eligibility).19 We also included indicators for patients who were frail using a previously validated algorithm,28 the number of chronic conditions using the flags for individual diagnoses from the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse research database, and the Major Diagnostic Categories.29,30 We obtained SNF characteristics such as ownership type (for-profit, non-profit, government), census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), urban location (urban/rural), chain membership (yes/no) and whether the facility was part of a hospital from CASPER.20 Measures of case-mix adjusted staffing hours per resident per day (total, registered nurse, licensed practical nurse, and certified nursing assistant) and star ratings (overall, quality, staffing, and health inspection) were obtained from CMS’ Care Compare website.21 County-level counts of the number of facilities and Medicare Advantage penetration were obtained from the Area Health Resource File.22

Statistical Analyses

We compared outcomes for patients with dementia receiving short-stay care in SNFs which did and did not use these three dementia-focused care tools for their short-stay patients. As a counterfactual control, we compared these differences to those for non-dementia patients in the same facilities, who theoretically would have less (or no) direct benefit from the presence of these services in their facility. To assess the association between dementia-focused care and outcomes, we used a difference-in-differences-based estimator with linear regression models for each outcome. The key quantity of interest in these models was an interaction term between a patients’ dementia status and the presence/absence of a dementia-focused care tool, representing the association of the care tool for those with dementia beyond the “expected” difference for those without dementia.

We estimated unadjusted and adjusted linear regression models with nursing home random effects for each outcome, including controls for the observable study variables listed above. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 and R Studio version 1.4.110. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. However, given the use of multiple comparisons, we regard our findings as exploratory.

Results

Patient and Facility Characteristics

We identified 102,860 short-stay care episodes for 68,347 Medicare beneficiaries receiving care from 377 SNFs from 2018–2019. Among the 102,860 episodes, there were 21,108 episodes for patients who met the criteria for dementia and 81,752 episodes for patients without a dementia diagnosis in our sample. There were linkable resident assessments in the MDS for 91,907 of these episodes (17,572 episodes for patients with dementia).

71 facilities reported using a dementia care unit for their short-stay patients. There were few statistically significant differences between SNFs with and without such units, except that they were less likely to be in the West census region (9.9% vs. 21.6%, p=0.02) (Table 1). A total of 307 SNFs indicated that they provided cognitive deficiency training to their staff and 217 facilities indicated that they provided dementia-specific occupational therapy. There were no statistically significant facility-level differences between facilities with or without cognitive deficiency training, while facilities offering dementia-specific occupational therapy were more likely to be for-profit (80.6% vs. 69.5%, p=0.01) or located in the Northeast census region (24.9% vs. 13.5%, p=0.01) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Facility Characteristics

| Facility Characteristics | Dementia Care Unit | Cognitive Deficiency Training | Dementia Occupational Therapy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +Tool | −Tool | p-value | +Tool | −Tool | p-value | +Tool | −Tool | p-value | |

| N | 71 | 287 | 307 | 51 | 217 | 141 | |||

| Ownership Type (%) | |||||||||

| For-Profit | 81.7% | 74.9% | 0.23 | 76.2% | 76.5% | 0.97 | 80.6% | 69.5% | 0.01 |

| Non-Profit | 11.3% | 20.2% | 0.08 | 18.2% | 19.6% | 0.82 | 15.2% | 23.4% | 0.05 |

| Government | 7.0% | 4.9% | 0.47 | 5.5% | 3.9% | 0.63 | 4.1% | 7.1% | 0.22 |

| Urban (%) | 70.4% | 78.0% | 0.17 | 77.2% | 72.5% | 0.47 | 78.3% | 73.8% | 0.32 |

| Certified Beds (mean) | 130.4 | 111.0 | 0.10 | 116.9 | 102.5 | 0.28 | 121.4 | 104.8 | 0.08 |

| Chain Membership (%) | 67.6% | 66.2% | 0.82 | 65.5% | 72.5% | 0.33 | 69.1% | 62.4% | 0.19 |

| In Hospital (%) | 1.4% | 2.8% | 0.51 | 2.6% | 2.0% | 0.79 | 2.8% | 2.1% | 0.71 |

| Census Region (%) | |||||||||

| Northeast | 23.9% | 19.5% | 0.41 | 20.5% | 19.6% | 0.88 | 24.9% | 13.5% | 0.01 |

| Midwest | 31.0% | 31.7% | 0.91 | 31.3% | 33.3% | 0.77 | 27.2% | 38.3% | 0.03 |

| South | 35.2% | 27.2% | 0.18 | 29.0% | 27.5% | 0.82 | 30.4% | 26.2% | 0.39 |

| West | 9.9% | 21.6% | 0.02 | 19.2% | 19.6% | 0.95 | 17.5% | 22.0% | 0.29 |

| Overall Star Rating (mean) | 2.9 | 3.2 | 0.12 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 0.60 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 0.38 |

Within facilities, patients with dementia differed from those without. For example, in facilities using a dementia care unit for short-stay patients, those with dementia were more likely to be white (84.3% vs. 79.0%, p<0.0001) and less likely to be dual-eligible (20.1% vs. 22.6%, p<0.0001) (Table S2).

Patient Outcomes by Dementia-Focused Care Offered

Patient outcomes differed in facilities that did or did not offer certain dementia-focused care services. The unadjusted 90-day readmission rate among short-stay patients with dementia was 31.8% for those who received care in a facility using a dementia care unit and 34.1% for those in a facility without such a unit compared to 34.5% vs. 34.8%, respectively, for patients without dementia (Table 2). There were several other differences in both unadjusted and unadjusted outcomes between facilities with and without dementia care units used for patients with and without dementia (Table S3, Table S4), such as longer cumulative length of stay for patients with dementia in facilities which did and did not use a dementia care unit for their short-stay patients. Facilities offering the other two dementia-specific services (staff training or occupational therapy), had differences in other patient outcomes, such as higher total costs and slightly lower antipsychotic use for patients with dementia (Table S3, S5).

Table 2:

Adjusted estimates for each dementia-focused care tool, by dementia-status

| Dementia Tool | Outcome | Dementia Patients | Non-Dementia Patients | Interaction | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +Tool | −Tool | Diff | p-value | +Tool | −Tool | Diff | p-value | DiD | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Dementia Care Unit Used For Short-Stay Residents | Part B Total Cost ($) | 27859 | 29189 | −1330 | 0.13 | 28779 | 29400 | −620 | 0.44 | −710 | (−1662, 243) | 0.14 |

| Readmission Rate (90d) | 32.3% | 34.5% | −2.2% | 0.04 | 34.6% | 35.1% | −0.6% | 0.47 | −1.7% | (−3.6%, 0.3%) | 0.09 | |

| Mortality Rate (90d) | 18.4% | 18.1% | 0.3% | 0.73 | 19.0% | 18.4% | 0.6% | 0.39 | −0.3% | (−1.8%, 1.2%) | 0.70 | |

| Healthy Day at Home (90d) | 75.2 | 74.5 | 0.8 | 0.37 | 73.8 | 74.5 | −0.7 | 0.31 | 1.5 | (0.4, 2.6) | 0.01 | |

| ED visit Rate (90d) | 27.3% | 26.8% | 0.6% | 0.65 | 28.3% | 25.9% | 2.4% | 0.02 | −1.8% | (−3.6%, 0.0%) | 0.05 | |

| Subsequent SNF Admission | 28.6% | 32.1% | −3.5% | 0.001 | 26.9% | 27.3% | −0.4% | 0.56 | −3.1% | (−4.9%,1.2%) | 0.001 | |

| Cumulative SNF Length of Stay | 33.6 | 31.1 | 2.5 | 0.08 | 28.2 | 27.8 | 0.4 | 0.77 | 2.1 | (1.0, 3.3) | 0.0003 | |

| Cognitive Deficiency Training | Part B Total Cost ($) | 29042 | 27892 | 1150 | 0.27 | 29225 | 29530 | −304 | 0.74 | 1454 | (269, 2639) | 0.02 |

| Readmission Rate (90d) | 34.3% | 32.1% | 2.2% | 0.09 | 35.1% | 34.3% | 0.8% | 0.36 | 1.4% | (−1.0%,3.8%) | 0.27 | |

| Mortality Rate (90d) | 18.3% | 17.0% | 1.3% | 0.23 | 18.6% | 18.1% | 0.4% | 0.59 | 0.9% | (−1.0%, 2.8%) | 0.37 | |

| Healthy Day at Home (90d) | 74.6 | 74.2 | 0.4 | 0.69 | 74.3 | 74.5 | −0.2 | 0.85 | 0.6 | (−0.8, 2.0) | 0.43 | |

| ED visit Rate (90d) | 27.0% | 26.6% | 0.4% | 0.79 | 26.5% | 25.3% | 1.3% | 0.28 | −0.9% | (−3.1%, 1.4%) | 0.44 | |

| Subsequent SNF Admission | 31.5% | 30.9% | 0.6% | 0.66 | 27.4% | 25.8% | 1.6% | 0.07 | −1.0% | (−3.3%, 1.3%) | 0.38 | |

| Cumulative SNF Length of Stay | 31.6 | 31.7 | −0.2 | 0.92 | 27.8 | 28.6 | −0.9 | 0.58 | 0.7 | (−0.7, 2.1) | 0.35 | |

| Dementia Occupational Therapy | Part B Total Cost ($) | 29190 | 28446 | 744 | 0.30 | 29276 | 29245 | 31 | 0.96 | 713 | (−58, 1484) | 0.07 |

| Readmission Rate (90d) | 34.1% | 34.0% | 0.1% | 0.91 | 34.6% | 35.8% | −1.2% | 0.05 | 1.3% | (−0.2%, 2.9%) | 0.09 | |

| Mortality Rate (90d) | 18.2% | 18.0% | 0.2% | 0.79 | 18.5% | 18.5% | 0.1% | 0.90 | 0.1% | (−1.1%, 1.4%) | 0.84 | |

| Healthy Day at Home (90d) | 74.7 | 74.4 | 0.3 | 0.65 | 74.4 | 74.3 | 0.1 | 0.87 | 0.2 | (−0.7, 1.1) | 0.65 | |

| ED visit Rate (90d) | 27.0% | 26.8% | 0.3% | 0.77 | 26.1% | 26.9% | −0.8% | 0.32 | 1.1% | (−0.3%, 2.6%) | 0.13 | |

| Subsequent SNF Admission | 31.9% | 30.6% | 1.3% | 0.12 | 27.3% | 27.1% | 0.3% | 0.65 | 1.0% | (−0.5%, 2.5%) | 0.18 | |

| Cumulative SNF Length of Stay | 31.8 | 31.2 | 0.5 | 0.65 | 27.8 | 28.1 | −0.4 | 0.73 | 0.9 | (0.0, 1.8) | 0.06 | |

Notes: ED is emergency department; SNF is skilled nursing facility; Diff measures the difference in outcomes between patients receiving care in facilities with and without each tool; 95% CI is 95% Confidence Interval. DiD is difference-in-differences.

Interaction between Dementia-Focused Care and Dementia Status

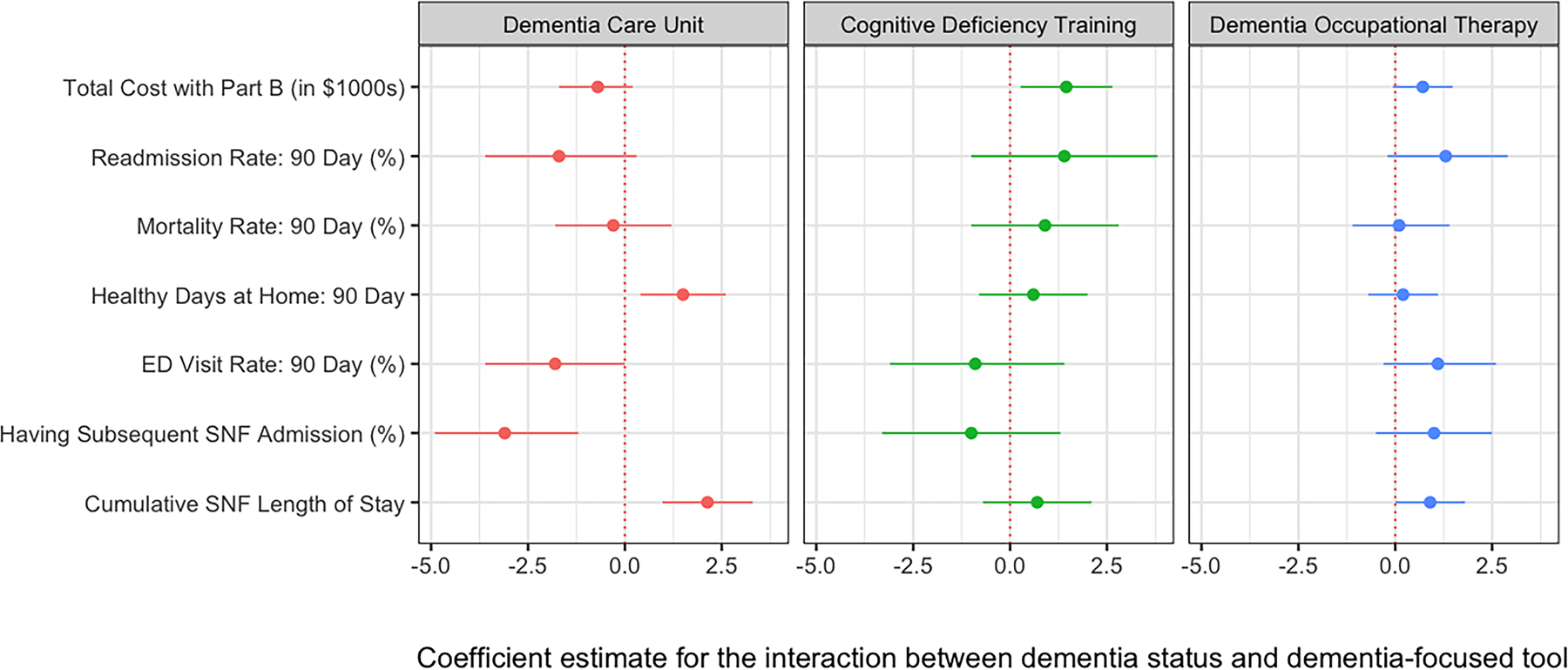

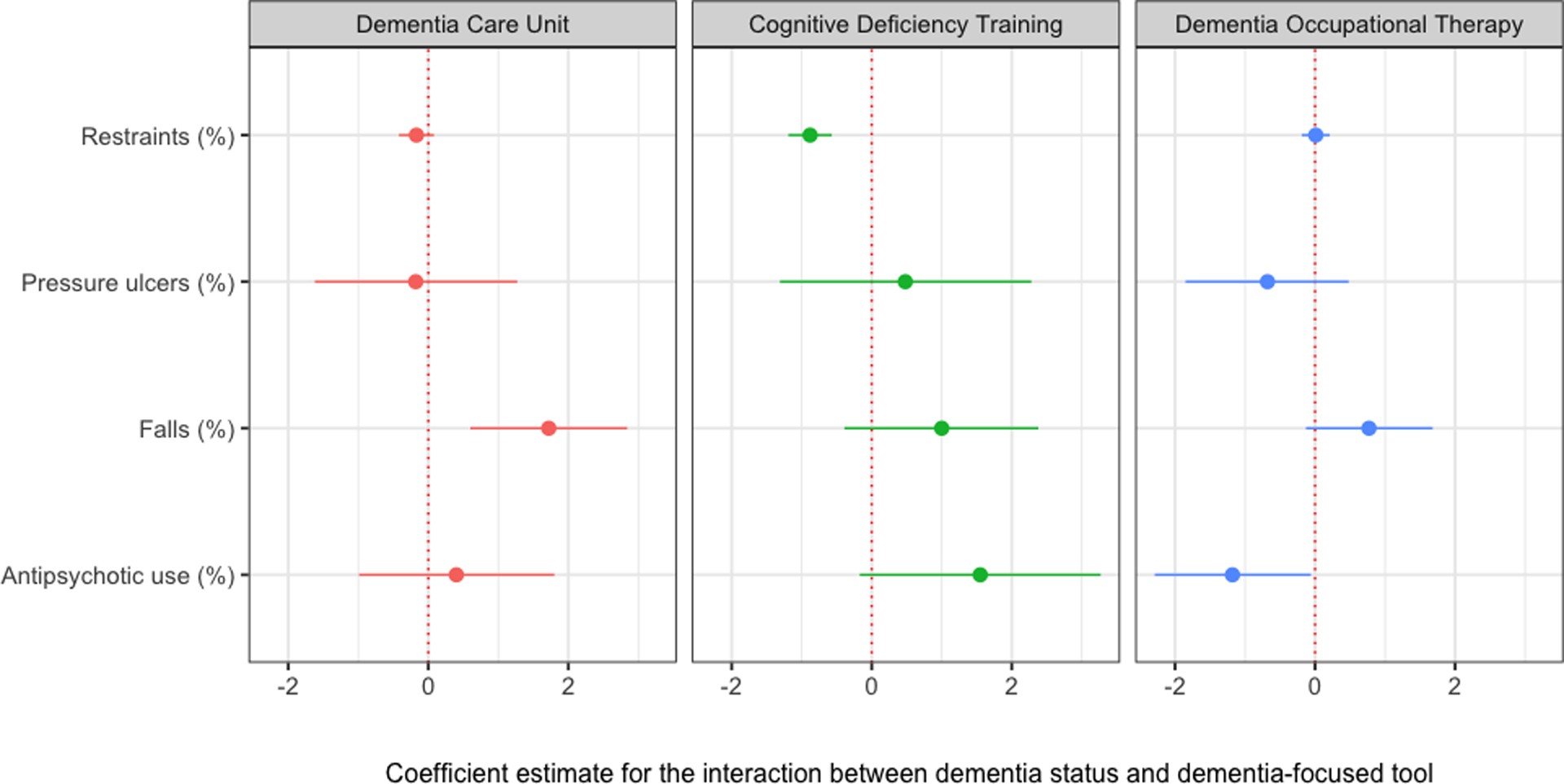

In adjusted comparisons of the interaction between a patient’s dementia status and receiving care at a facility offering one of the dementia-focused tools, the use of a dementia care unit for short-stay patients was associated with a 1.5 day greater healthy days at home (p=0.01) and a 3.1% lower likelihood of a subsequent SNF admission (p=0.001) for patients with dementia relative to the counterfactual control of non-dementia patients receiving care at these same facilities (Figure 1). Dementia care units were also associated with a 2.1 day longer cumulative length of stay (p=0.0003) (Figure 1, Table S4) and a 2.8% lower readmission rate in the 90-days from hospital discharge (p=0.005) (Table S6). The adjusted difference of receiving care in a facility which did and did not use a dementia care unit for short-stay dementia patients compared to that for non-dementia patients was associated with a 1.7% higher prevalence of falls per episode (p=0.01) (Figure 2).

Figure 1:

Adjusted difference in claims-based outcome measures for patients with and without dementia with short-stays in SNFs with and without dementia-focused care tools

The point and bars represent the coefficient estimate and 95% confidence interval from the adjusted regression results comparing outcomes for the interaction of dementia status (with vs. without dementia) and the presence of each of the dementia-focused care tools used for short-stay patients (dementia care unit, dementia occupational therapy, cognitive deficiency training). Negative coefficient estimates are generally associated with better outcomes (e.g., lower costs and lower readmission rates are good outcomes) while positive values are associated with worse outcomes. The exception is healthy days at home, for which higher numbers are better.

Figure 2:

Adjusted difference in MDS outcome measures for patients with and without dementia with short-stays in SNFs with and without dementia-focused care tools.

The point and bars represent the coefficient estimate and 95% confidence interval from the adjusted regression results comparing outcomes for the interaction of dementia status (with vs. without dementia) and the presence of each of the dementia-focused care tools used for short-stay patients (dementia care unit, dementia occupational therapy, cognitive deficiency training). Negative coefficient estimates are generally associated with better outcomes while positive values are associated with worse outcomes.

Offering cognitive deficiency training to their staff by dementia status was associated with higher total cost to Medicare of $1,454 (p=0.02) (Figure 1) and slightly higher antipsychotic use (2.0% higher per episode, p=0.03) comparing patients with and without dementia (Figure 2) while occupational therapy was associated with a higher rate of falls (1.2% higher per episode, p=0.01).

Offering two dementia-focused care tools was associated with slightly higher total cost including Part B ($819 higher, p=0.04) while offering all three dementia-focused care tools was associated with 2.5 days greater healthy days at home (p=0.0001), a 2.7% decreased likelihood of a subsequent SNF admission (p=0.01), but also a 2.2 day longer stay (p=0.001) and an increase in falls of 2.8% per episode (p< 0.0001) (Table S5, Table S7).

Discussion

In this national study of dementia-focused care tools in SNFs, we found that the use of a dementia care unit for short-stay patients was associated with modestly better performance in multiple outcomes for patients with dementia. In contrast, cognitive deficiency training and dementia-specific occupational therapy had mixed associations with the measured outcomes. Regardless of these associations, results from our survey respondents provide encouraging evidence that many SNFs have adopted innovative care delivery tools to address the needs of their short-stay patients with dementia. Building off promising prior evidence on the role of special care units for long-term care,6,7,31 our findings on dementia care units used for short-stay patients suggest that this care delivery strategy is worth more detailed study as a new care model to improve avoidable hospitalizations and optimize time at home.

These hypothesis-generating results can inform investment in future care delivery changes in SNFs. This study contributes to the existing literature by utilizing results from a national survey focusing specifically on the use of innovative care delivery models for short-stay patients. Also, this study addresses confounding between SNFs by using a counterfactual control of patients without dementia receiving care in the same facilities that did and did not offer each dementia-focused care tool.

We observed that dementia patients who received care from a facility using a dementia care unit for their short-stay patients had several improved outcomes compared to that of non-dementia patients, with lower levels in the likelihood of having a subsequent SNF admission and increases in healthy days at home. These findings were also consistent when assessing facilities which offered all three dementia-focused care tools, suggesting that our findings were driven by the use of dementia care units for short-stay patients. Though the dementia care units were not positively associated with all of our measured outcomes, differences in care needs between patients with and without dementia32,33 suggest that nursing home patients with dementia might benefit from a longer length of stay in a dementia care unit to adequately address their care needs. These positive findings are somewhat tempered by a negative association of dementia care units with an increase in falls, which may be associated with longer length of stay (more time for falls to happen) or potentially better documentation of falls in the MDS.34 Another explanation concerns the tradeoff between mobilizing patients and keeping them in bed, as patients in dementia care units may receive more rehabilitation and assistance with their mobility, which increases the risk of incidental falls but may not necessarily be a negative outcome. Overall, our findings complement prior studies finding that dementia-focused units for long-stay patients were associated with better quality and greater satisfaction with care for long-stay patients with dementia,7 including being less likely to have bed rails or be tube fed31 alongside reductions in inappropriate antipsychotics use, physical restraints, pressure ulcers, and hospitalizations.6

Results for cognitive deficiency training and dementia occupational therapy were less positive. There were many negative associations observed for dementia patients residing in facilities offering these two dementia-focused care services, including statistically significant higher total cost, increased falls, and higher antipsychotic use. These negative associations contrast with prior literature finding greater patient satisfaction in facilities which utilized specialized workers trained in domains related to dementia, including managing and addressing depression, pain, behavioral symptoms, and ambulation.35 The mixed findings in this study could be explained by variation among survey respondents in implementation, as person-centered dementia care strategies must be tailored to each patient’s circumstance and involve flexible problem-solving approaches.16

Though this study is cross-sectional and cannot causally link any dementia-focused care tools with benefits for short-stay patients with dementia, our findings permit hypothesis generation to guide future research to improve SNF care delivery, which has been an elusive, but high priority goal.4,36,37 Given the positive associations identified for short-stay dementia patients receiving care from a facility using dementia care units, our findings suggest that there may be some additive benefit from offering a tailored physical environment for those with dementia. Further research should focus on understanding the mechanisms behind the positive associations identified for dementia-focused physical units and improved outcomes.

Our study has limitations. As mentioned above, this is a cross-sectional study that cannot address the causality of the observed associations and should be interpreted as exploratory hypothesis generation. The decision to receive care in a SNF with dementia-focused services is not random, so selection bias could influence our results. Also, we identified facilities using the three dementia-focused care tools based on self-reported responses to our national survey. As a result, facilities may have interpreted the use of dementia-focused services differently. The survey required closed form responses (yes, no, don’t know), so we were not able to assess the magnitude or frequency of how often these tools were utilized. Additionally, even if a facility reported that they used the dementia-focused tool for their short-stay patients, we do not know for certain if a patient with dementia necessarily received these specialized services or if the use of a dementia care unit was specifically for short-stay patients receiving post-acute care or also longer-stay patients who might have received care in the unit temporarily. We were also unable to differentiate between heterogeneous improvement in our outcome measures which may be the result of unmeasured differences in quality, as patients with dementia might benefit more than other patients from receiving care from a high quality facility, versus the direct result of receiving specialized dementia care for patients with dementia.

Due to concerns about confounding because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we utilized Medicare claims and the MDS from 2018–2019 to identify our sample and assess patient costs, utilization, and clinical outcomes prior to pandemic. We assumed that facilities which reported using dementia-focused care during our 2020–2021 survey also had these services in 2018–2019 as it is unlikely that SNFs started implementing them during the pandemic. However, because our outcomes were measured prior to the administration of the survey, we could not determine whether the differences in outcomes between facilities with and without the dementia-focused care tools were driven by practice change from using these tools or the result of worsening outcomes among patients with dementia. Additionally, our survey sample size included a small share (n=377) of nursing homes in the U.S., which may limit the generalizability of our findings, and we are unable to assess whether our response rate was hampered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, this study focused on outcomes for the Medicare fee-for-service population and does not necessarily reflect associations that would be observed for other populations such as Medicare Advantage or Medicaid.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional study, the use of a dementia care unit was associated with modestly better performance in healthy days at home and decreased likelihood of a subsequent SNF admission compared to a counterfactual control of patients without dementia. In contrast, dementia occupational therapy or cognitive deficiency training were not associated with any positive improvements in the quality or utilization measures. While the clinical significance is small, these results provide hypothesis-generating evidence that using dementia care units could be a mechanism to improve care delivery for short-stay patients with dementia.

Supplementary Material

Key Points:

Dementia care units were associated with small decreases in the likelihood of a SNF readmission alongside modest increases in healthy days at home.

Results for cognitive deficiency training and dementia occupational therapy were more mixed, with increased total costs and some worsened clinical measures.

Why does this paper matter?

Hypothesis-generating results suggest the use of dementia care units for short-stay patients may be a promising mechanism to improve care delivery in nursing homes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conflicts of Interest

This work was supported by grants K23 AG058806 (Barnett) and R01 AG060935 from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (Epstein, Grabowski, Orav, and Joynt Maddox). Dr. Epstein receives compensation from the New England Journal of Medicine. Dr. Joynt Maddox receives or has received compensation from the Journal of the American Medical Association, Centene Corporation, and Humana Inc. Dr. Grabowski receives compensation from AARP, Analysis Group, GRAIL, and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Dr. Barnett receives compensation as an expert witness through Greylock McKinnon Associates.

Sponsor’s Role

The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Burke RE, Xu Y, Ritter AZ. Outcomes of post‐acute care in skilled nursing facilities in Medicare beneficiaries with and without a diagnosis of dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(10):2899–2907. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):729–736. doi: 10.7326/M15-0381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer’s Association. 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures.; 2022.

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS ANNOUNCES PARTNERSHIP TO IMPROVE DEMENTIA CARE IN NURSING HOMES. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Published 2012. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-announces-partnership-improve-dementia-care-nursing-homes [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahn H, Horgas A. The relationship between pain and disruptive behaviors in nursing home residents with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joyce NR, McGuire TG, Bartels SJ, Mitchell SL, Grabowski DC. The Impact of Dementia Special Care Units on Quality of Care: An Instrumental Variables Analysis. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(5):3657–3679. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cadigan RO, Grabowski DC, Givens JL, Mitchell SL. The quality of advanced dementia care in the nursing home: the role of special care units. Med Care. 2012;50(10):856–862. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31825dd713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes. Published 2022. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/surveycertificationgeninfo/national-partnership-to-improve-dementia-care-in-nursing-homes

- 9.Chaudhury H, Cooke HA, Cowie H, Razaghi L. The Influence of the Physical Environment on Residents With Dementia in Long-Term Care Settings: A Review of the Empirical Literature. The Gerontologist. 2018;58(5):e325–e337. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrahamson K, Lewis T, Perkins A, Clark D, Nazir A, Arling G. The influence of cognitive impairment, special care unit placement, and nursing facility characteristics on resident quality of life. J Aging Health. 2013;25(4):574–588. doi: 10.1177/0898264313480240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coleman EA, Barbaccia JC, Croughan-Minihane MS. Hospitalization rates in nursing home residents with dementia. A pilot study of the impact of a special care unit. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(2):108–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03470.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abrahamson K, Clark D, Perkins A, Arling G. Does cognitive impairment influence quality of life among nursing home residents? The Gerontologist. 2012;52(5):632–640. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbott KM, Sefcik JS, Van Haitsma K. Measuring social integration among residents in a dementia special care unit versus traditional nursing home: A pilot study. Dementia. 2017;16(3):388–403. doi: 10.1177/1471301215594950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruneir A, Lapane KL, Miller SC, Mor V. Does the presence of a dementia special care unit improve nursing home quality? J Aging Health. 2008;20(7):837–854. doi: 10.1177/0898264308324632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palan Lopez R, Hendricksen M, McCarthy EP, et al. Association of Nursing Home Organizational Culture and Staff Perspectives With Variability in Advanced Dementia Care: The ADVANCE Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(3):313. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.7921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alzheimer’s Association. Dementia Care Practice Recommendations for Assisted Living Residences and Nursing Homes. Alzheimer’s Association; 2009. https://www.alz.org/media/documents/dementia-care-practice-recommend-assist-living-1-2-b.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen AC, Epstein AM, Joynt Maddox KE, Grabowski DC, Orav EJ, Barnett ML. Care delivery approaches and perceived barriers to improving quality of care: A national survey of skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. Published online March 14, 2023:jgs.18331. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long Term Care Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0 | ResDAC. Accessed April 21, 2022. https://resdac.org/cms-data/files/mds-30 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Research Data Assistance Center. Data Documentation: Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF) Base. ResDAC. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://resdac.org/cms-data/files/mbsf-base/data-documentation [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) Quality Reporting Program (QRP) Public Reporting. U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Published 2023. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Skilled-Nursing-Facility-Quality-Reporting-Program/SNF-Quality-Reporting-Program-Public-Reporting [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Provider Data Catalog. CMS. Accessed April 29, 2022. https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/dataset/4pq5-n9py

- 22.Area Health Resources Files. Accessed April 21, 2022. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf

- 23.Barnett ML, Joynt Maddox KE, Orav EJ, Grabowski DC, Epstein AM. Association of Skilled Nursing Facility Participation in a Bundled Payment Model With Institutional Spending for Joint Replacement Surgery. JAMA. 2020;324(18):1869–1877. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moura LMVR, Festa N, Price M, et al. Identifying Medicare beneficiaries with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(8):2240–2251. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolanowski A, Litaker M, Buettner L, Moeller J, Costa PT. A randomized clinical trial of theory-based activities for the behavioral symptoms of dementia in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(6):1032–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03449.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burke LG, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Jha AK. Healthy Days at home: A novel population-based outcome measure. Healthcare. 2020;8(1):100378. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2019.100378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Quality Measures | CMS. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Published January 4, 2022. Accessed December 23, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/nursinghomequalityinits/nhqiqualitymeasures [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim DH, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Lipsitz LA, Rockwood K, Avorn J. Measuring Frailty in Medicare Data: Development and Validation of a Claims-Based Frailty Index. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73(7):980–987. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse. Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://www2.ccwdata.org [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnett ML, Waken RJ, Zheng J, et al. Changes in Health and Quality of Life in US Skilled Nursing Facilities by COVID-19 Exposure Status in 2020. JAMA. 2022;328(10):941. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.15071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gruneir A, Lapane KL, Miller SC, Mor V. Is dementia special care really special? A new look at an old question. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(2):199–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabbagh MN, Silverberg N, Majeed B, et al. Length of stay in skilled nursing facilities is longer for patients with dementia. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2003;5(1):57–63. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bardenheier BH, Rahman M, Kosar C, Werner RM, Mor V. Successful Discharge to Community Gap of FFS Medicare Beneficiaries With and Without ADRD Narrowed. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(4):972–978. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mintz J, Lee A, Gold M, Hecker EJ, Colón-Emeric C, Berry SD. Validation of the Minimum Data Set items on falls and injury in two long-stay facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(4):1099–1100. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Williams CS, et al. Dementia care and quality of life in assisted living and nursing homes. The Gerontologist. 2005;45 Spec No 1(1):133–146. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konetzka RT. The Challenges of Improving Nursing Home Quality. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1920231. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grabowski DC, Chen A, Saliba D. Paying for Nursing Home Quality: An Elusive But Important Goal. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(2):342–348. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.