Abstract

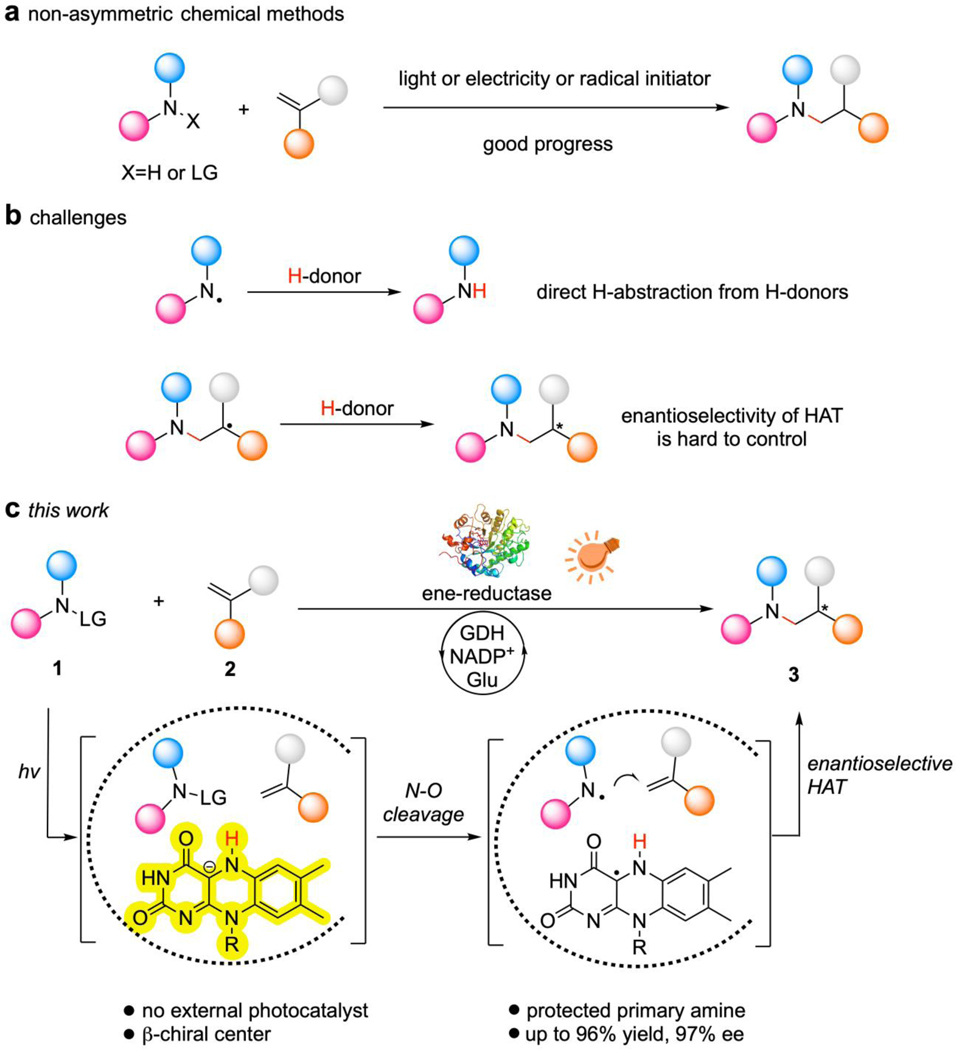

Since the discovery of Hofmann-Löffler-Freytag reaction more than 130 years ago, nitrogen-centered radicals have been widely studied in both structures and reactivities1–2. Nevertheless, catalytic enantioselective intermolecular radical hydroamination remains a challenge due to the existence of side reactions, short lifetime of nitrogen-centered radicals, and lack of understanding of the fundamental catalytic steps. In chemistry, nitrogen-centered radicals are produced with radical initiators, photocatalysts, or electrocatalysts. On the other hand, the generation and reaction of nitrogen-centered radicals are unknown in nature. Here we report a pure biocatalytic system by successfully repurposing an ene-reductase through directed evolution for the photoenzymatic production of nitrogen-centered radicals and enantioselective intermolecular radical hydroaminations. These reactions progress efficiently at room temperature under visible light without any external photocatalysts and exhibit excellent enantioselectivities. Detailed mechanistic study reveals that the enantioselectivity originates from the radical-addition step while the reactivity originates from the ultrafast photoinduced electron transfer (ET) from reduced flavin mononucleotide (FMNH-) to nitrogen-containing substrates.

Chiral amines are key building blocks in bioactive molecules, natural products, synthetic intermediates, and resolution agents and have wide applications in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and materials, as well as asymmetric catalysis3. Great progress has been made for the synthesis of chiral amines in the ground states through controlling the key nucleophilic attack step, hydride transfer step, or reductive elimination step of nitrogen-containing substrates using an organocatalyst, a transition-metal catalyst, or an enzyme4–8. Despite the success in the preparation of chiral amines in the ground states, where the reactivity primarily originates from nitrogen-containing substrates’ nucleophilicity and coordinating ability to metals, few examples have been demonstrated for the enantioselective cross-coupling reactions of nitrogen-centered radicals, of which the polarities are sometimes considered inversed compared to their corresponding amines9–10. Two major problems need to be solved before the chemistry of nitrogen-centered radicals can be controlled in an enantioselective manner: (i) nitrogen-centered radicals are highly unstable and can easily be quenched by abstracting a hydrogen atom, (ii) it is difficult to control the chirality of radical-addition of a nitrogen-centered radical to an unsaturated bonds without a binding group for an organocatalyst or a transition-metal catalyst, especially when the targeted chiral center is remote from the reaction center11–13, 1–2. To date, the existing methodologies for asymmetric addition of nitrogen-centered radicals to unsaturated bonds are limited to intramolecular systems and enantioselective intermolecular radical hydroamination remains a challenge in this field for both chemical chiral catalysts and enzymes (Fig. 1)14–16. Given the versatility of radical chemistry, the discovery of effective and clean ways to control the intermolecular reactivity of nitrogen-centered radicals in an enantioselective manner would bring more flexibility to the design of synthetic routes for chiral amines and is therefore highly desirable17.

Fig. 1 |. Catalytic enantioselective intermolecular radical hydroaminations.

a, Non-asymmetric chemical methods. b, Challenges in enantioselective intermolecular radical hydroamination reactions. c, Proposed photoenzymatic scheme for the enantioselective intermolecular radical hydroamination of protected primary amines with control over the β-chiral center. GDH, glucose dehydrogenase; NADP+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; Glu, glucose.

Nature has evolved enzymatic systems where radicals can be generated, stabilized, and controlled for a variety of biological processes such as the modification of genes, biological oxidations, and synthesis of metabolic intermediates18. These processes are efficient, selective, environmentally friendly, tunable through directed evolution, and demonstrate great potential in biomanufacturing. Enzymes with the ability to tame radicals have inspired chemists to design complementary chemo-catalysts19–20. Conversely, chemistry has inspired biologists to further engineer native enzymes or design artificial enzymes for the development of new-to-nature reactivities21–23. Within this context, photoenzymatic catalysis can access nonnatural radical chemistry via the photoinduced promiscuity of enzyme redox cofactors and is a promising platform for the discovery of abiological radical reactions24. In recent years, photoenzymatic systems featuring flavine mononucleotide (FMN)-dependent ene-reductases and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+)-dependent ketoreductases have been repurposed to carry out enantioselective intramolecular or intermolecular reductions of carbon-halogen bonds, carbon-oxygen bonds, and unsaturated carbon-carbon bonds25–29. Inspired by these studies, we hypothesized that photoenzymatic catalysis with FMN-dependent ene-reductases could potentially address the long-term challenges in enantioselective intermolecular radical hydroamination reactions by controlling the key catalytic steps including: the generation of the nitrogen-centered radical through photoinduced ET from FMNH- in its excited state to the nitrogen-containing precursor, the prevention of the highly energetically favored side reaction of hydrogen atom abstraction of photogenerated nitrogen-centered radical, the intermolecular radical-addition of the nitrogen-centered radical to the pre-anchored olefin substrate, and the enantioselective hydrogen-atom transfer (HAT) for the production of the chiral amine.

Results

Reaction discovery and condition optimization

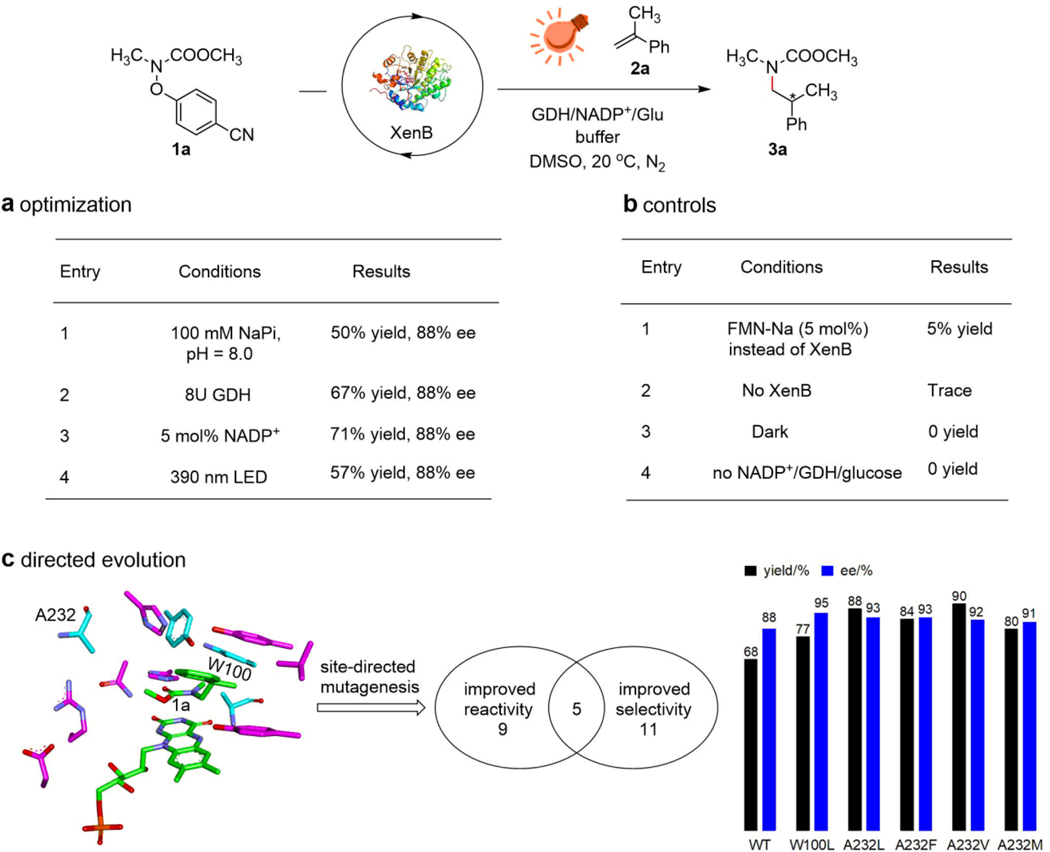

To test our hypothesis, we sought to study the photoenzymatic hydroamination reaction between carbamate 1a, a protected primary aliphatic amine pre-anchored with leaving groups bearing N‒O bonds, and ɑ-methyl styrene in sodium phosphate (NaPi) buffer (pH = 8.0) with ene-reductases, NADP+, glucose dehydrogenase (GDH), and glucose under visible-light illumination. We chose FMN-dependent ene-reductase because FMNH- in its excited state is a powerful reductant and can perform ET to the nitrogen-containing substrates directly without the need for any external photocatalyst or reductants. We chose these leaving groups because N‒O bonds are labile and can undergo homolytic cleavage upon reduction, the reduction potentials of these nitrogen-containing substrates can be easily tuned by changing the substitution groups on the leaving groups, and these leaving groups can be easily attached to the nitrogen-containing precursor from hydroxylamines30–31. We first tested the reaction using 2,4-dinitrosulfonate as the leaving group. However, we observed full consumption of the substrate but no formation of the target product. We suspected that these types of substrates are too reactive and can be reduced directly by the ene-reductases even without photoexcitation. Therefore, we decided to use phenolates as leaving groups instead. As we expected, a series of ene-reductases can produce the target product 3a enantioselectively, where XenB from Pseudomonas putida showed the best reactivity and selectivity for protected methyl amines using 4-cyanophenolate as the leaving group (Supplementary Table 1). It is worth mentioning that there is little change in the enantioselectivity as the leaving group is changed (Supplementary Table 2). We then optimized the reaction conditions using XenB (Supplementary Table 3). We found that the pH and the type of the buffer are the key factors that influence the outcome of this reaction and the reaction generally gives better yields under acidic conditions where imidazole buffer, pH = 6.5, gave the best result (68% yield, 88% enantiomeric excess (ee)). Compared to the standard conditions, the presence of more GDH or NADP+ and using a light source with shorter wavelengths show similar reactivities and the same enantioselectivity (Fig. 2a). Control experiments suggest that the presence of XenB, light, and the cofactor regeneration system is necessary for this transformation (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2 |. Reaction development.

a, Optimization of the reaction conditions. b, Control experiments. c, Directed evolution of XenB for the hydroamination reaction of substrates 1a and 2a. Standard conditions: 0.008 mmol of 1a, 0.002 mmol of 2a, 2 mol% enzyme, 2.5 mol% NADP+, 0.01 mmol of glucose, and 5U GDH in 50 mM imidazole buffer, pH = 6.5 containing 15 vol% DMSO and 15 vol% glycerol were stirred and irradiated with 540 mW 440 nm blue LED at 20 ℃ under nitrogen atmosphere for 24–48 h. Yields were determined using GC-MS. Enantiomeric excesses were determined using HPLC with chiral stationary phases. See Supplementary Fig. 1 for the photocatalysis setup. See Supplementary Table 4 for primers used in the directed evolution. See Supplementary Table 5 for the outcomes of the directed evolution.

Directed evolution of XenB

To further improve the efficiency of the photoenzymatic hydroamination reaction, we performed directed evolution on XenB (see the Supplementary Information, Section 6). In the first round of directed evolution, we found that 9 mutants show improved reactivity while 11 mutants show improved enantioselectivity (Supplementary Table 5). Among them, XenB-W100L (E1, 77% yield, 95% ee), XenB-A232L (E2, 88% yield, 93% ee), XenB-A232F (E3, 84% yield, 93% ee), XenB-A232V (E4, 90% yield, 92% ee), and XenB-A232M (E5, 80% yield, 91% ee) show both improved enantioselectivity and reactivity (Fig. 2c). Among these five mutants, E1 and E2 demonstrated the best yields and enantioselectivities and were used to expand the substrate scope.

Substrate scope

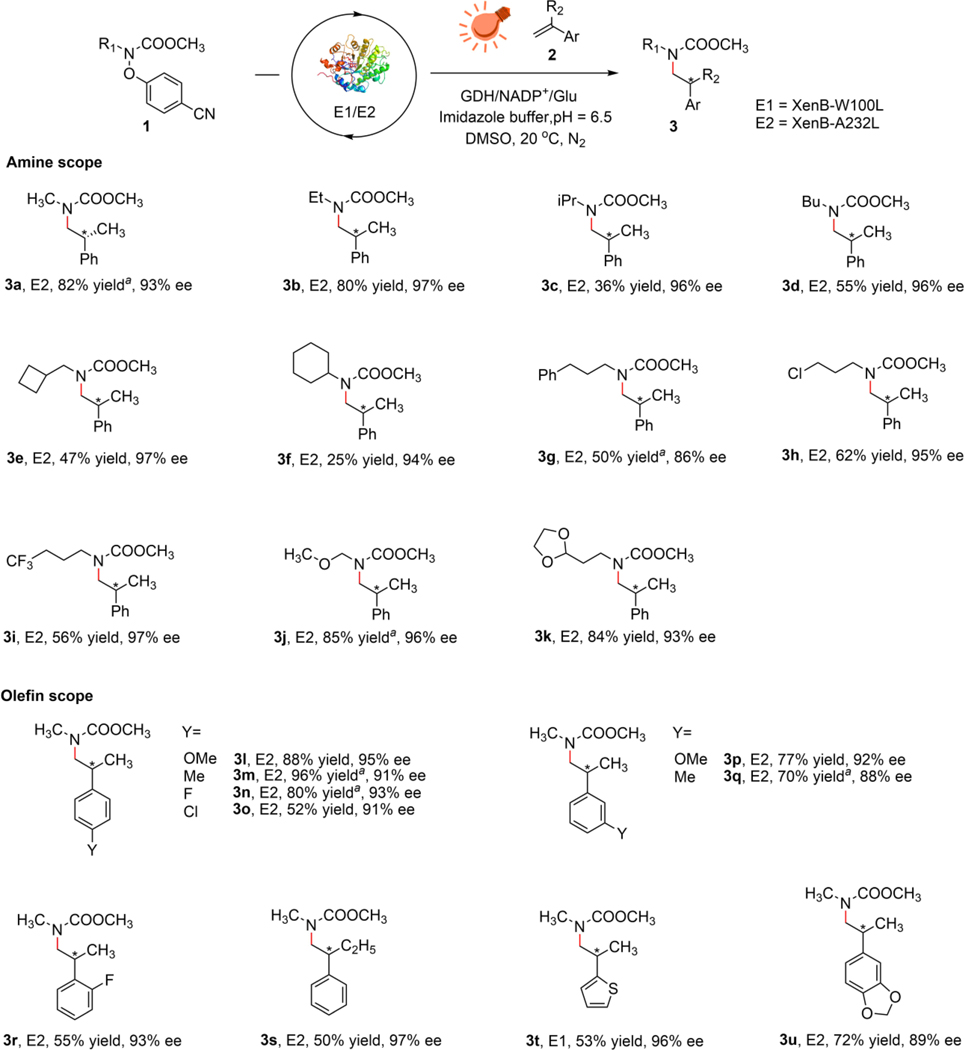

Unlike molecular catalysis where the bulkiness of functional groups on substrates usually has little effect on the efficiency of an established reaction, enzymatic catalysis is more sensitive to the sizes of substrates due to the confined active sites of the enzymes. With this in mind, we carefully examined the scope of protected primary amines in this intermolecular hydroamination reaction. In the presence of E2, aliphatic amines 1a-1k gave the product 3a-3k with 25–88% yield and 93–97% ee, with the increase in the size of the aliphatic group resulting in a decrease in the reactivity. The attachment of a phenyl ring on one side of a propyl group is also compatible with this reaction, albeit with moderate yield. The reaction progresses at 47–87% yield and 93–97% ee in the presence of pharmaceutically relevant cyclobutyl-, chloro-, trifluoromethyl-, ether-, and 1,3-dioxolane groups. To our surprise, protected aldehyde 3k was produced in 84% yield, despite the bulkiness of the dioxolane. We reasoned that this unexpected high yield of 3k originates from the better solubility of 1,3-dioxolane in aqueous media as compared to other alkyl groups due to its large polarity (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 |. Substrate scope of the photoenzymatic enantioselective intermolecular radical hydroamination.

Reactions were performed under the standard conditions described in Fig. 2. Yields were determined using GC-MS. Enantiomeric excesses were determined using HPLC with chiral stationary phases. aisolated yield with 0.08 mmol 2a.

For the olefins, substitutions on the aromatic rings with a variety of functional groups were proved to be competent and products 3l-3u were produced with 50–96% yield and 88–97% ee. Among them, electron donating groups on the para- position of the olefin gave >80% yields while electron withdrawing groups gave decreased the yields. This result is consistent with the fact that carbamyl nitrogen-centered radicals are electrophilic and have larger affinity towards electron-rich olefins. Compared to the substitution on the para- position of the olefin, substitution on the ortho- and meta- position show decreased yields. Ortho- methyl and methyloxy substituted substrates produced trace target products, probably due to unfavored binding modes of these substrates to the enzyme’s active site for the desired radical-addition to progress. In addition, disubstituted olefin, ɑ-substituted olefin and heterocycle are also compatible with this reaction. Furthermore, scaled-up reactions gave the isolated products with similar reactivity and selectivity to the standard conditions (Fig. 3) Aliphatic olefins such as 2-methylbutene or isopropenylcyclohexane are not compatible with this reaction, which is possibly due to the thermodynamic instability of the corresponding carbon-centered radicals produced in the radical-addition step.

Mechanistic studies

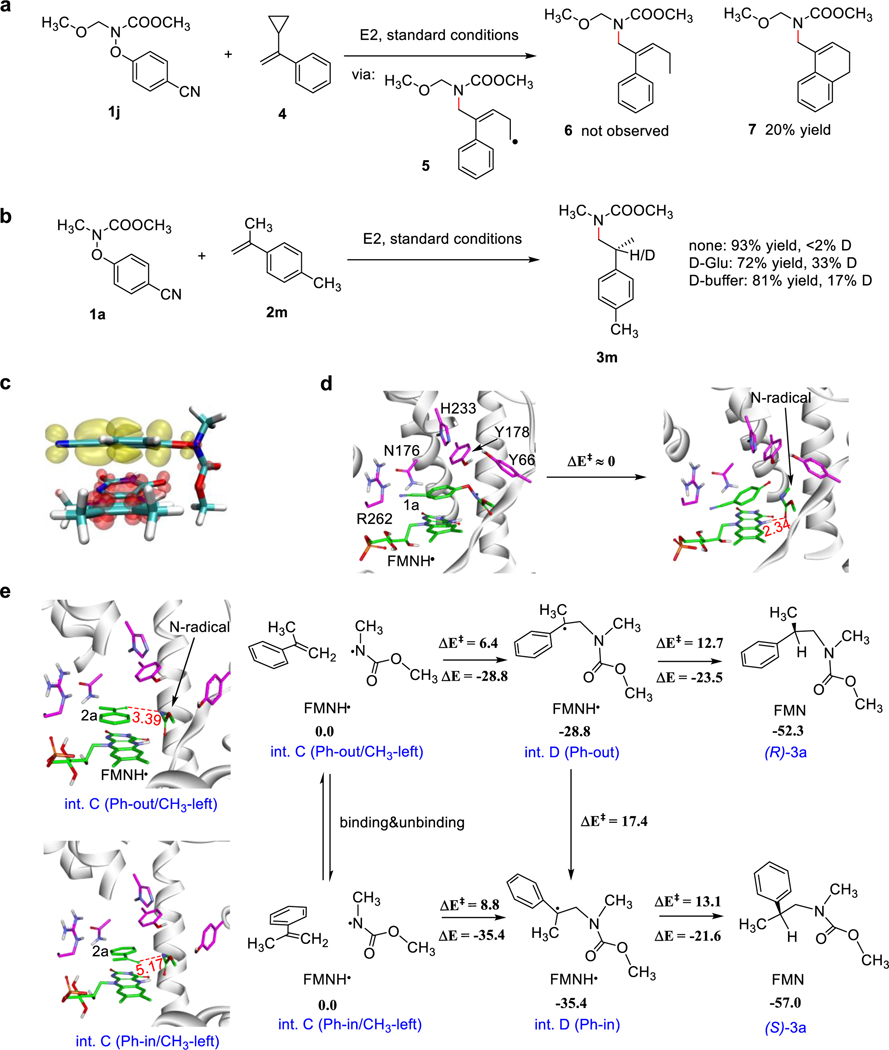

To investigate the mechanism of this reaction (Supplementary Fig. 2), we performed the radical clock experiment with substrate 1j and ɑ-cyclopropyl styrene 4 (Fig. 4a). The formation of the signature triplet signal in the olefin range of the 1H NMR spectrum of the reaction mixture supports the radical mechanism. We did not observe the formation of the desired product 6 but observed a product whose molecular weight is 2 g mol−1 smaller. We reasoned that the radical intermediate 5 undergoes intramolecular cyclization to produce the product 7 rather than hydrogen atom abstraction. We then performed the isotope-labeling experiments with substrate 1a and 2m to track the source of hydrogen atom in the HAT step (Fig. 4b). The deuterated portion is 33% with D-glucose-d and 17% with deuterated buffer. We conclude that the hydrogen atom in the chiral center of product 3 comes from FMNH• while H/D exchange between FMNH• and buffer accounts for the partial deuteration.

Fig. 4 |. Mechanistic studies.

a, Radical clock experiment. b, Isotope-labelling experiments. c, The first singlet excited state of the XenB-1a complex consisting of 1a and FMNH-. Charge density difference showing the loss (in red) and gain (in yellow) of electronic charge of the XenB-1a complex. d, Photoinduced ET to substrate 1a results in the cleavage of N‒O bond and the formation of the nitrogen-centered radical. e, Overview of the enantioselectivity-determining step to afford the prochiral radical (int. D as described in Supplementary Fig. 2) in Ph-out/CH3-left and Ph-in/CH3-left conformation, key distances are given in angstroms. QM/MM calculations show that the energy of Ph-out/CH3-left is close to that of Ph-in/CH3-left. See details in Supplementary Figs. 10-11.

To decipher the molecular mechanism for the origin of enantioselectivity in this hydroamination reaction, we performed multiscale simulations on XenB. Time-dependent density-functional theory (TDDFT) calculations suggest that the complex formed between FMNH- and substrate 1a (Fig. 4c) has a maximum absorption at 406 nm (Supplementary Table 6). Molecular dynamics (MD) and quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics-molecular dynamics (QM/MM-MD) simulations on the docked complex lead to a similar conformation, where substrate 1a is anchored in the active site via π–π stacking between its benzene ring and FMNH- (Fig. 4d, left, Supplementary Figs. 3-6)29. TDDFT and QM/MM-MD calculations on the first singlet (S1) and triplet (T1) excited state of the complex suggest that the N‒O bond cleavage is spontaneous upon reduction, producing the N-centered radical with a barrier of less than 1 kcal mol−1 (Supplementary Fig. 7), which is constrained in the active site by H-bonding between its carbonyl group and FMNH• (Fig. 4d, right).

After the formation of the N-centered radical, we assume the hydrophilic 4-cyanophenolate (∆Gsolvation = −53.2 kcal/mol) would diffuse out of the active site while its binding position be replaced by the hydrophobic olefin 2a (∆Gsolvation = −2.6 kcal/mol, Supplementary Table 7, Supplementary Fig. 8). Molecular docking indicates that 2a can adopt four representative conformations, among which Ph-in/CH3-left and Ph-out/CH3-right lead to (S)-3a while Ph-in/CH3-right and Ph-out/CH3-left lead to (R)-3a (Supplementary Fig. 9). Ph-in and Ph-out conformers have similar binding energies to XenB and we assume they can convert to each other through unbinding and binding (Supplementary Table 8, Supplementary Figs. 10-11). Although the conformational change of 2a via the flip of methyl group (CH3-left→CH3-right) is facile both kinetically and thermodynamically, the subsequent C-N couplings from the CH3-right conformations were found to have higher barriers than those from the CH3-left conformations due to the larger distances between the double bond of 2a and the N-centered radical (Supplementary Figs. 12-13). From the CH3-left conformations, the C‒N coupling from Ph-out conformation affords the prochiral radical int. D (as described in the proposed catalytic cycle Supplementary Fig. 2) with a smaller barrier (6.4 kcal mol−1) compared to that of the Ph-in conformation (8.8 kcal mol−1, Supplementary Figs. 14-16). For comparison, the direct HAT from FMNH• to the N-centered radical has a high barrier of 9.2 kcal mol−1, indicating the side-reaction to produce N-methyl methylcarbamate cannot compete with the C‒N coupling inside the active site of XenB (Supplementary Figs. 17-21).

Then, two competing pathways were investigated from the prochiral radical int. D (as described in the proposed catalytic cycle in Supplementary Fig. 2) in Ph-out/CH3-left conformation. The HAT from the adjacent FMNH• to the prochiral radical center has a lower barrier of 12.7 kcal mol−1 compared to that of the internal rotation of the prochiral radical from Ph-out to Ph-in conformation (17.4 kcal mol−1), suggesting that the formation of (R)-3a is more favored over the conformational exchange of the prochiral radical, en route to (S)-3a (Fig. 4e). From this data, we conclude that the enantioselectivity is determined by the C‒N coupling step rather than the HAT step. This conclusion is in agreement with the experimentally determined chirality of the product.

Despite the successful application of photoenzymatic catalysis with ene-reductases in organic synthesis, fundamental studies on the photoinduced ET step from ene-reductases to organic substrates remains elusive32–33. To understand the photoinduced ET step, we performed steady-state and time-resolved spectroscopic measurements on the model system composed of XenB-A232L, substrate 1k, and the cofactor regeneration system (see the Supplementary Information, section 10). We observed that the absorption features of XenB-A232L hydroquinone does not change with the substrate, indicating no formation of the electron donor-acceptor (EDA) complex, and photoinduced ET from FMNH-* to the substrate occurs in 8.5 ps and the subsequent N‒O cleavage occurs in 642 ps (Supplementary Figs. 22-23).

Discussion

In conclusion, we have successfully applied photoenzymatic catalysis to accomplish the challenging enantioselective intermolecular radical hydroamination reaction using a repurposed ene-reductase XenB. Within the enzymatic pocket, the direct hydrogen-atom-abstraction of nitrogen-centered radicals is significantly inhibited to produce the product in an enantioselective manner, which is otherwise hard to achieve through pure chemical methods. Notably, the olefin substrates can be derived from fatty acids while the resulting products β-chiral amines have broad applications in the synthesis of important molecules, thereby providing a strategy for biomass utilization and fatty acid upgrading. One limitation of this reaction for practical use is the low turnover number as compared to the enzyme’s natural reactivity, which can be attributed to (i) FMNH-’s poor absorption for visible light and low quantum yield in its excited state, (ii) the limited size of the enzyme’s active site to accommodate the substrates with bulky substitution groups, (iii) the instability of the radical intermediates, and (iv) the poor solubility of the substrates in aqueous media. Further directed evolution of the enzyme to optimize its optical properties, increase its compatibility to substrates, intermediates, and organic solvents can potentially improve the turnover number of this reaction. Another limitation is the requirement for the use of purified enzyme, which could potentially be improved by metabolic engineering of the host bacteria to minimize side reactions involving other components in the cells. This work clearly demonstrates the potential of the combination of biocatalysis and photocatalysis to solve the long-term challenges in synthetic chemistry and to bring more diversity to the development of novel synthetic methodologies.

Methods

General Procedures for Photoenzymatic Reactions

In a 4 mL glass vial containing 66 µL 600 µM XenB solution and 5U GDH-105 (purchased from Codexis) was added ~400 µL 150 mM imidazole buffer, pH = 6.5, 10 µL 3.7 mg/mL NADP+ solution, 40 µL 45 mg/mL glucose solution, 150 µL 80% vol% glycerol in water, and 120 µL DMSO solution containing 0.002 mmol olefin and 0.008 mmol carbamate under N2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was subsequently loaded on the photocatalytic setup shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 and illuminated with 540 mW 440 nm blue LED at ~20 ℃ for 24~48 h. Afterwards, dodecane was added to the reaction mixture, which was extracted with 2×1 mL EtOAc and loaded on GC-MS for characterization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Core Facilities at the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology where majority of the experiments in this project were performed. We thank the School of Chemical Sciences NMR Lab for NMR experiments at variant temperatures. We thank Dr. Xiankun Li (OSU), Dr. Maolin Li (UIUC), and Dr. Guangde Jiang (UIUC) for helpful discussions. We thank Tianhao Yu (UIUC) for designing the primers. This work was funded by the DOE Center for Advanced Bioenergy and Bioproducts Innovation (U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under Award Number DE-SC0018420 to H.Z.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 22122305 to B.W.), and the National Institute of Health (Grant GM144047 to D.Z.). NMR data were collected at the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology Core, on a 600-Mhz NMR funded by the National Institute of Health (no. S10-RR028833 to H.Z.). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Energy.

Footnotes

Competing interests The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

All data is available in the main text or the supplementary materials or from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Pratley C, Fenner S & Murphy JA. Nitrogen-Centered Radicals in Functionalization of sp2 Systems: Generation, Reactivity, and Applications in Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 122, 8181–8260 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiong T & Zhang Q. New amination strategies based on nitrogen-centered radical chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 3069–3087 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nugent TC Chiral amine synthesis: methods, developments and applications (John Wiley & Sons, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartwig JF & Stanley LM. Mechanistically driven development of iridium catalysts for asymmetric allylic substitution. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 1461–1475 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu RY & Buchwald SL. CuH-catalyzed olefin functionalization: from hydroamination to carbonyl addition. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1229–1243 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacMillan DW. The advent and development of organocatalysis. Nature. 455, 304–308 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mutti FG, Knaus T, Scrutton NS, Breuer M & Turner NJ. Conversion of alcohols to enantiopure amines through dual-enzyme hydrogen-borrowing cascades. Science. 349, 1525–1529 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seayad J & List B. Asymmetric organocatalysis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 3, 719–724 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cecere G, Konig CM, Alleva JL & MacMillan DW. Enantioselective direct alpha-amination of aldehydes via a photoredox mechanism: a strategy for asymmetric amine fragment coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11521–11524 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Z et al. Enantioselective catalytic β-amination through proton-coupled electron transfer followed by stereocontrolled radical–radical coupling. Chem. Sci. 8, 5757–5763 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J-R, Hu X-Q, Lu L-Q & Xiao W-J. Visible light photoredox-controlled reactions of N-radicals and radical ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 2044–2056 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi GJ et al. Catalytic alkylation of remote C-H bonds enabled by proton-coupled electron transfer. Nature. 539, 268–271 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu JC & Rovis T. Amide-directed photoredox-catalysed C-C bond formation at unactivated sp(3) C-H bonds. Nature. 539, 272–275 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gentry EC et al. Enantioselective Synthesis of Pyrroloindolines via Noncovalent Stabilization of Indole Radical Cations and Applications to the Synthesis of Alkaloid Natural Products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 3394–3402 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roos CB, Demaerel J, Graff DE & Knowles RR. Enantioselective Hydroamination of Alkenes with Sulfonamides Enabled by Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5974–5979 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye Y et al. Using enzymes to tame nitrogen-centred radicals for enantioselective hydroamination. Nat. Chem. 15, 206–212. (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mondal S et al. Enantioselective Radical Reactions Using Chiral Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 122, 5842–5976 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frey PA, Hegeman AD & Reed GH. Free radical mechanisms in enzymology. Chem. Rev. 106, 3302–3316 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Que L & Tolman WB. Biologically inspired oxidation catalysis. Nature. 455, 333–340 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang P-Z, Chen J-R & Xiao W-J. Hantzsch esters: an emerging versatile class of reagents in photoredox catalyzed organic synthesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 17, 6936–6951 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bloomer BJ, Clark DS & Hartwig JF. Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities with Artificial Metalloenzymes in Biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 62, 221–228 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang P-S, Boyken SE & Baker D. The coming of age of de novo protein design. Nature. 537, 320–327 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller DC, Athavale SV & Arnold FH. Combining chemistry and protein engineering for new-to-nature biocatalysis. Nat. Synth. 1, 18–23 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrison W, Huang X & Zhao H. Photobiocatalysis for Abiological Transformations. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 1087–1096 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biegasiewicz KF, Cooper SJ, Emmanuel MA, Miller DC & Hyster TK. Catalytic promiscuity enabled by photoredox catalysis in nicotinamide-dependent oxidoreductases. Nat. Chem. 10, 770–775 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biegasiewicz KF et al. Photoexcitation of flavoenzymes enables a stereoselective radical cyclization. Science. 364, 1166–1169 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emmanuel MA, Greenberg NR, Oblinsky DG & Hyster TK. Accessing non-natural reactivity by irradiating nicotinamide-dependent enzymes with light. Nature. 540, 414–417 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang X et al. Photoinduced chemomimetic biocatalysis for enantioselective intermolecular radical conjugate addition. Nat. Catal. 5, 586–593 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang X et al. Enantioselective intermolecular radical hydroalkylation. Nature. 584, 69–74 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies J, Morcillo SP, Douglas JJ & Leonori D. Hydroxylamine derivatives as nitrogen-radical precursors in visible-light photochemistry. Eur. J. Chem. 24, 12154–12163 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganley JM, Murray PRD & Knowles RR. Photocatalytic Generation of Aminium Radical Cations for C-N Bond Formation. ACS Catal. 10, 11712–11738 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kudisch B et al. Active-site environmental factors customize the photophysics of photoenzymatic old yellow enzymes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 124, 11236–11249 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandoval BA et al. Photoenzymatic reductions enabled by direct excitation of flavin-dependent “ene”-reductases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 1735–1739 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data is available in the main text or the supplementary materials or from the authors upon reasonable request.