Abstract

The mechanism of action (MoA) of a clickable fatty acid analogue 8-(2-Cyclobuten-1-yl)octanoic acid (DA-CB) has been investigated for the first time. Proteomics, metabolomics, and lipidomics were combined with a network analysis to investigate the MoA of DA-CB against Mycobacterium smegmatis (Msm). The metabolomics results showed that DA-CB has a general MoA related to that of ethionamide, a mycolic acid inhibitor that targets enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA), but DA-CB likely inhibits a step downstream from InhA. Our combined multi-omics approach showed that DA-CB appears to disrupt the pathway leading to the biosynthesis of mycolic acids, an essential mycobacterial fatty acid for both Msm and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). DA-CB decreased keto-meromycolic acid biosynthesis. This intermediate is essential in the formation of mature mycolic acid, which is a key component of the mycobacterial cell wall in a process that is catalyzed by the essential polyketide synthase Pks13 and the associated ligase FadD32. The multi-omics analysis revealed further collateral alterations in bacterial metabolism including the overproduction of shorter carbon-chain hydroxy- and branched chain fatty acids, alterations in pyrimidine metabolism, and a predominately down-regulation of proteins involved in fatty acid biosynthesis. Overall, the results with DA-CB suggest the exploration of this and related compounds as a new class of tuberculosis therapeutics. Furthermore, the clickable nature of DA-CB may be leveraged to trace the cellular fate of the modified fatty acid or any derived metabolite or biosynthetic intermediate.

Keywords: multi-omics, tuberculosis, mechanism of action, NMR, mass spectrometry

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb).1 In 2021, over 10 million new cases of TB were reported worldwide.2 Currently, TB treatment is a slow and tedious regimen, in which multiple drugs are prescribed over the course of many months.3–9 Moreover, non-compliance with the treatment schedule has led to the reemergence of TB in the form of both multi-drug resistant and extensive drug resistant (i.e., MDR/XDR-TB) strains.10–13 In the quest to keep pace with TB antibiotic resistance, drug discovery efforts have emphasized the identification of new drug candidates that operate by novel mechanisms of action (MoA).14 In this regard, we previously synthesized and investigated eleven fatty acid analogues, six of which showed minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values equivalent to or better than the second-line TB drug D-cycloserine (DCS).15, 16 The fatty acid motifs were based on frameworks derived from decanoic acid (C10), oleic acid or elaidic acid (both C18). Several of these fatty acid analogues displayed low micromolar MIC values against various Mtb strains, where 8-(2-Cyclobuten-1-yl)octanoic acid (DA-CB), a cyclobutene-containing analog of decanoic acid, exhibited activity similar to the TB drugs, isoniazid (INH) and ethionamide (ETH). In addition to its efficacy, DA-CB is an intriguing lead compound because a strained cyclic alkene is present. This feature enables selective addressing of DA-CB or any derived biosynthetic intermediate via a “click” reaction17–20 providing a handle with which to decipher the location of the fatty acid analogue or derived conjugates within the mycobacterial cell.

The versatility and the pathogenicity of mycobacteria are primarily due to the make-up of the cellular envelope and their ability to survive and replicate intracellularly.1 The thick cell wall provides a protective layer against a host’s immune system, assists with antibacterial resistance, and increases structural integrity.21–24 The cell wall structure also differentiates mycobacteria from other prokaryotes. Accordingly, drug candidates that target mycobacterial cell wall biosynthesis are highly desirable.22, 23 Indeed, the most commonly used TB drug treatments, INH and ETH, target the biosynthesis of mycolic acids, structurally distinct fatty acids unique to mycobacteria.25–28 These compounds differ from common fatty acids in their size (sixty to ninety carbons), the presence of two major branches, and the frequent fusion of cyclopropanes onto the backbone. The biosynthesis of mycolic acids begins with the formation of malonyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA, which are further elongated by fatty acid synthetase type I (FAS-I). Incorporation of double bonds is mediated by the activation of desaturases and fatty acid type II synthetases (FAS-II). The introduction of cyclopropanes by cyclopropane synthetase forms alpha-meroacyl-ACP, the source of alpha-mycolic acid.29 Both Mycobacterium smegmatis (Msm) and Mtb can readily take-up fatty acids and convert them into mycolic acids.27, 28 Morbidoni et al. (2012) discovered two unnatural fatty acids containing carbon-carbon triple bonds, 2-hexadecynoic acid and 2-octadecynoic acid that are active against Msm.30 The modified fatty acids or derived species might destabilize the organism by inhibiting the mycolic acid biosynthetic machinery or by changing the integrity of the cell wall.15, 30 At the outset of these studies, we hypothesized that DA-CB might well function through a similar mechanism.

Proteomics is a valuable tool for identifying potential drug candidates while also providing an initial understanding of drug target interactions.31 Similarly, metabolomics has shown enormous potential when applied to investigating drug mechanisms, disease processes and drug discovery.32, 33 In this regard, metabolomics has been used for rapidly elucidating the MoA of novel drug candidates.34–37 A specialized subdivision of metabolomics, lipidomics, has also been used to elucidate the MoA of drugs; the broadened coverage of biological pathways offered by lipidomics is of utmost importance to determine potential alterations in the lipid rich mycobacterial cell wall. 38, 39 An example can be seen in the recent use of lipidomics to elucidate the mechanism of action for the anti-trypanosomal drug miltefosine.40 The drug was a priori predicted to be affecting phospholipid metabolism due to its lipid-similar structure, and lipidomics studies revealed that miltefosine produces major alterations in phospholipid levels. Simultaneously integrating lipidomics, metabolomics, and proteomics is expected to improve the efficiency and accuracy of MoA elucidation while also enhancing our understanding of the overall biological response to an individual drug treatment.41, 42 Simply, a multi-omics approach is capable of measuring changes across a larger and more diverse set of biomolecules,while providing a more complete and system-wide picture of drug-induced cellular changes.43 This wider span of coverage enables the construction of a unified and consensus network that permits the identification of off-target or secondary perturbations that commonly confound the analysis of omics data sets.42, 44 A resulting network generated from a combined proteomics, lipidomics, and metabolomics data set facilitates the analysis of drug activities by enabling the construction of predictive models of therapeutic efficacy and the identification of the lethal protein target(s) – the cellular target of a drug whose inhibition directly leads to cell death.

Herein, we describe an investigation into the MoA of DA-CB against Msm using a multi-omics approach that includes proteomics, metabolomics, and lipidomics. DA-CB appears to disrupt the pathway leading to the biosynthesis of mycolic acids, an essential mycobacterial fatty acid for both Msm and Mtb. Our results suggest DA-CB and related molecules have the potential for development as TB therapeutics. Moreover, the clickable nature of DA-CB may be leveraged to trace the cellular fate of the modified fatty acid or any derived synthetic intermediate.20

Results and discussion

DA-CB has a similar MoA as ETH, a mycolic acid inhibitor.

Compounds with a fatty acid skeleton, including some functionalized synthetic analogs of natural fats, can be incorporated into the fatty acid biosynthetic pathways.30 The fatty acid analogue of interest, DA-CB, has a MIC value for Mtb strains lower than 100 μM. This is similar to known inhibitors of cell wall biosynthesis (e.g., DCS and INH) used to treat Mtb infections. We have hypothesized that the Msm and Mtb inhibition observed with DA-CB may result from interference with cell wall biosynthesis or by alterations in the properties of the cell wall following incorporation of the modified fatty acid.

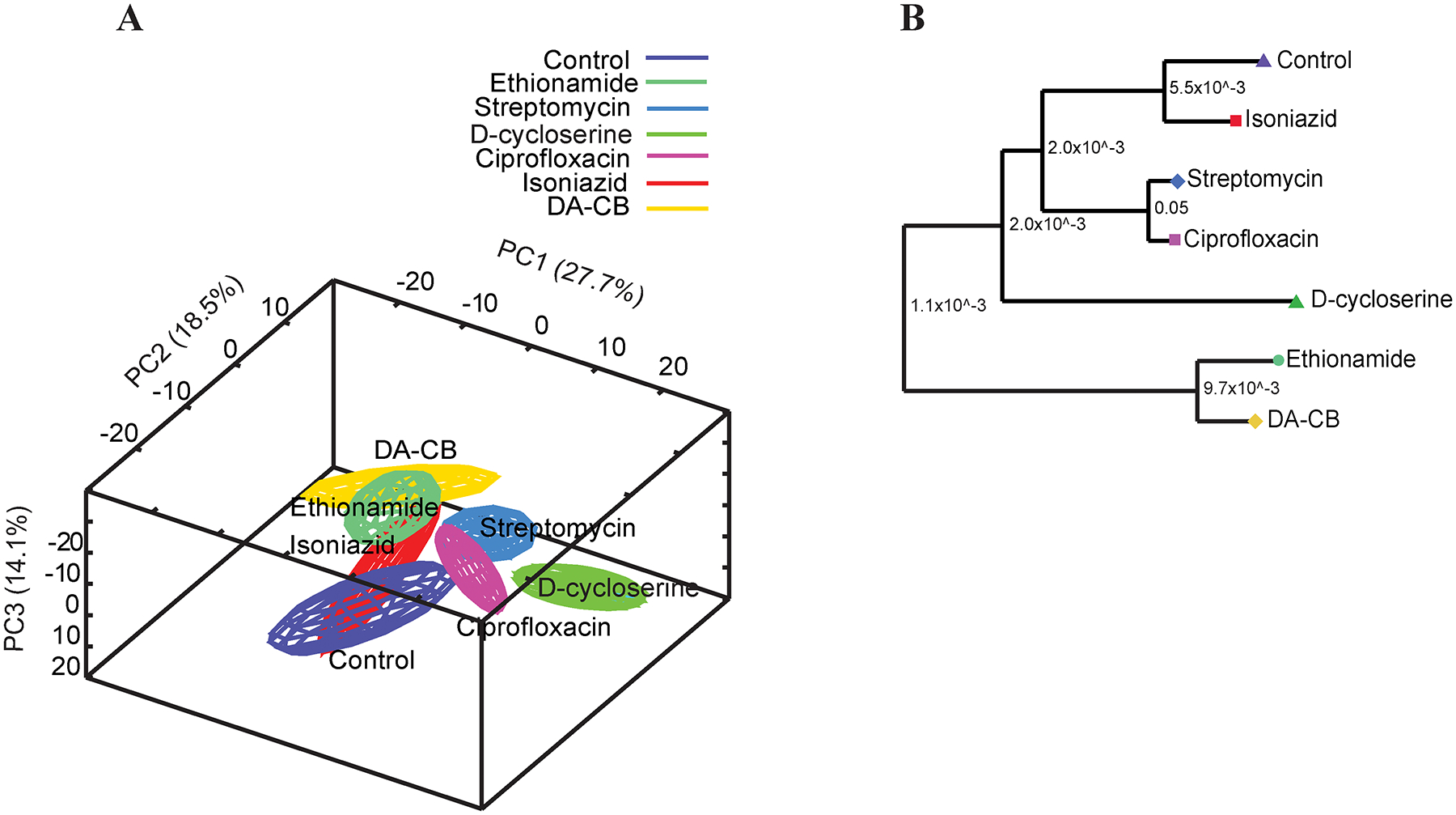

Our investigation into the MoA for DA-CB began with a comparison of the metabolic fingerprints of Msm after treatment with DA-CB or other anti-tubercular drugs with a known MoA, including known inhibitors of mycolic acid synthesis. The specific anti-tubercular drugs used in the metabolic fingerprint comparison included ciprofloxacin that inhibits DNA gyrase and prevents DNA supercoiling; DCS that prevents peptidoglycan biosynthesis; ETH and INH that both disrupt mycolic acid formation by inhibiting the enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA); and streptomycin that inhibits protein synthesis by binding to the 30S ribosomal protein S12 and 16S rRNA.36 To analyze these effects for DA-CB, we determined the concentration of DACB that inhibited growth by 50% (i.e., a sublethal drug dosage) under conditions equivalent to our metabolomics studies and as previously described.36 After these drug treatments, the Msm cells were lysed and the cellular metabolome extract was analyzed by NMR. Metabolic fingerprints obtained from one-dimensional (1D) 1H NMR data sets have been frequently employed to predict the general in vivo MoA for drug leads.35, 37 Drugs with similar MoAs would be expected to induce similar metabolic fingerprints and would cluster together in the scores plot from principal components analysis (PCA). The PCA scores plot followed by a hierarchical clustering analysis showed a close relationship between the DA-CB and ETH induced Msm metabolomes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Principal component analysis (PCA) scores plot generated from 1D 1H NMR data set using MVAPACK with 3 principal components. The PCA plot exhibits group differentiation with R2=0.755 and Q2=0.640. Untargeted metabolomics of Msm cells (purple), cells treated with isoniazid (INH, red), D-cycloserine (DCS, dark green), ethionamide (ETH, green), ciprofloxacin (magenta), streptomycin (blue) and DA-CB (yellow). Ellipsoids represent a 95% confidence limit of the normal distribution of each cluster. (B) Dendrogram generated from the PCA score plots with each Mahalanobis distance p-value represented between the nodes shows DA-CB is closely clustered with ethionamide.

An OPLS model comparing only the DA-CB treated or untreated Msm metabolomes (Figure S1A) was used to create a back-scaled loadings plot (Figure S1B) to identify the key metabolites that differentiated between the two groups. Specifically, glutamate was significantly decreased in DA-CB treated cells while alanine, AMP, glucose-1-phosphate, lactate. trehalose, and valine were increased. A follow-up two-dimensional (2D) 1H-13C heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) analysis of the 13C-carbon labeled Msm metabolomes identified over 40 metabolites derived from 13C-glucose that were significantly altered (false discover rate (FDR)-corrected p-value < 0.05) due to a DA-CB treatment. A heatmap (Figure S2A) and network map (Figure S2B) summarize these results. Overall, the preliminary NMR metabolomics analysis suggests DA-CB causes an increase in glycolysis and fatty acid metabolism, and a reduction in arginine and pyrimidine metabolism.

ETH is a second line drug commonly used to treat TB. ETH is structurally similar to INH and both are inhibitors of mycolic acid biosynthesis. Although they are both pro-drugs, the pathway of activation for ETH is distinct from INH.45 Specifically, ETH is activated by the mono-oxygenase EthA. In contrast, INH is activated by the peroxidase KatG. Both enzymes form a stable covalent adduct with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)46 that inhibits InhA, which is involved in mycolic acid biosynthesis.37, 47, 48 45

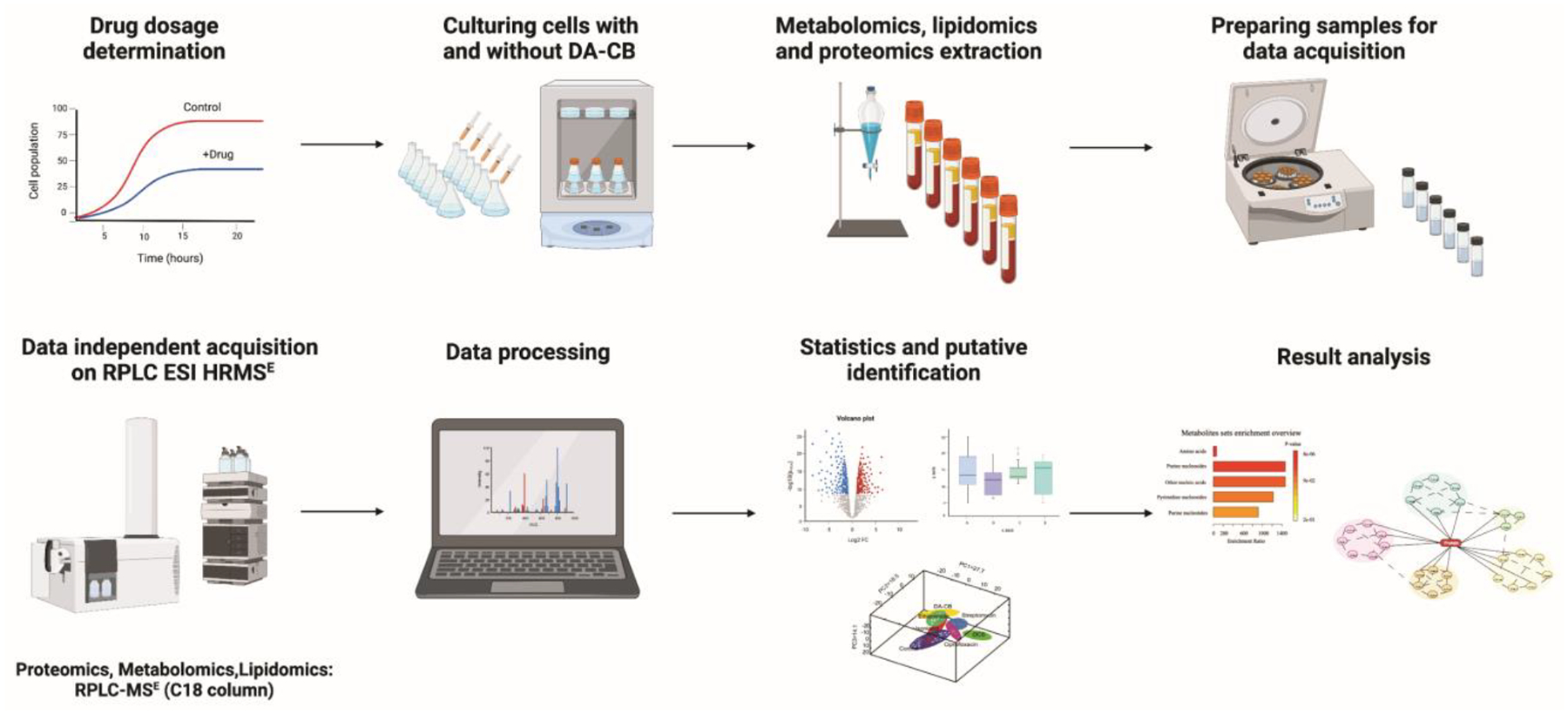

As DA-CB may also inhibit mycolic acid biosynthesis, we investigated the cellular processes that DA-CB alters by employing a multi-omics approach to characterize the metabolome, proteome, and lipidome of Msm. Statistical analysis of these individual omics data sets showed a significant alteration due to DA-CB. Msm cells were treated with DA-CB or DMSO (as a control), lysed, and the metabolome, lipidome, and proteome were extracted for reversed phase ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography mass spectrometry in a data independent acquisition mode (RP UHPLC-DIA-MS). The RP UHPLC-DIA-MS lipidomics data acquisition protocol was previously optimized to ensure complete coverage of the mycobacterial lipidome, with a special emphasis in the detection of mycolic acids.49. The lipidomics and metabolomics data were processed and analyzed with statistical software packages.50 The multi-omics protocol employed to characterize the cellular impact of DA-CB is summarized in Scheme 1.51

Scheme 1.

Workflow of multi-omics sample preparation and data acquisition using Reversed phase liquid chromatography electrospray ionization high resolution-mass spectrometry (RPLC ESI HR-MSE ) from DA-CB treated Msm. Created with BioRender.com.

Metabolomics identified amino acids, purines, pyrimidines, and fatty acyl glycosides were altered by DA-CB.

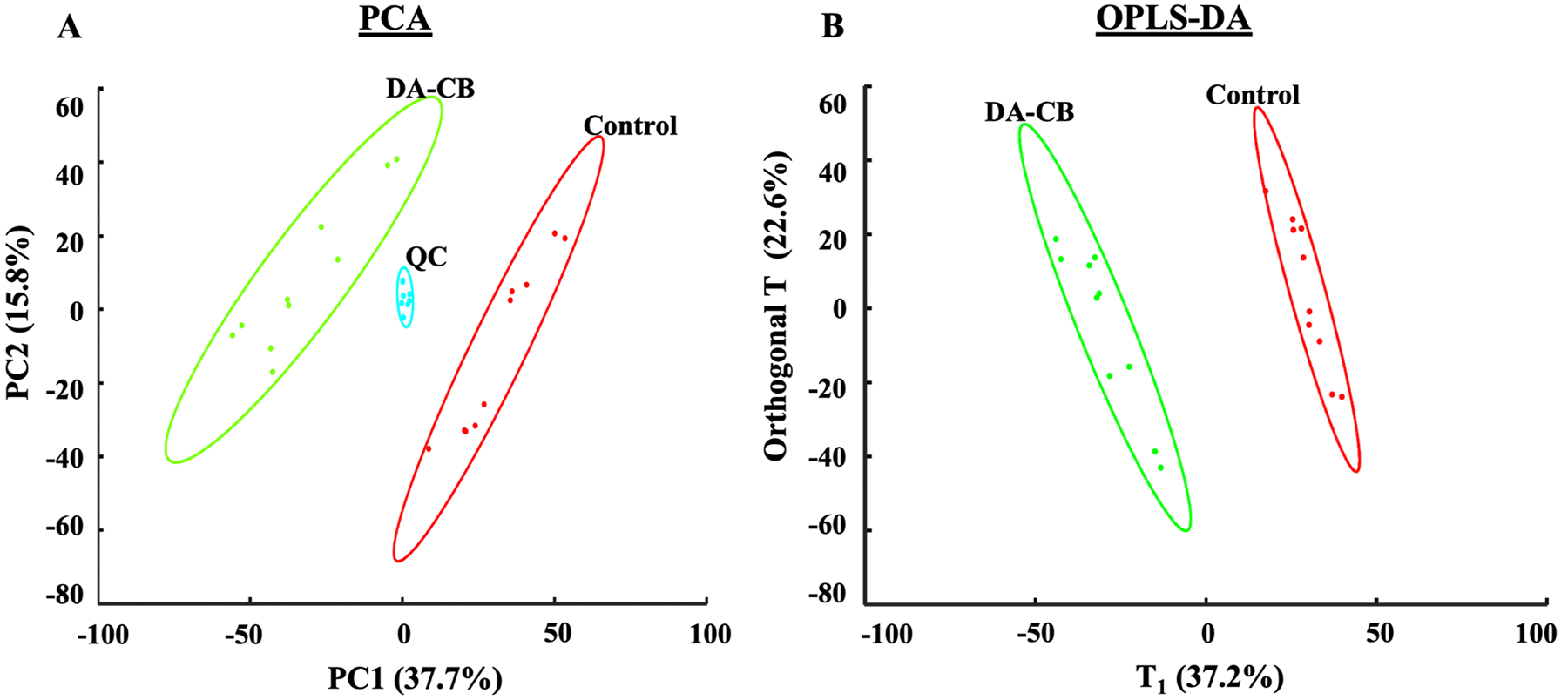

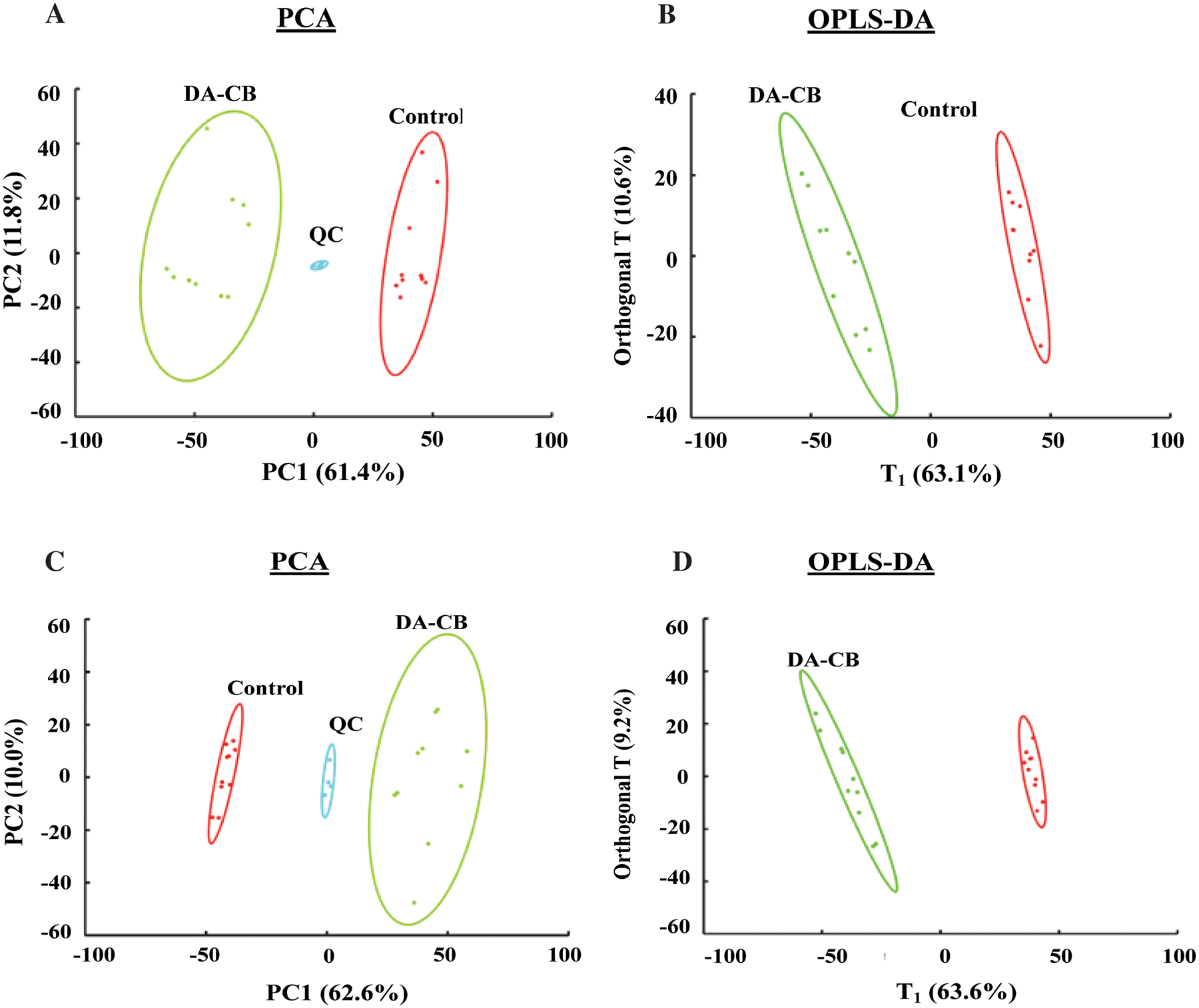

The LC-MS metabolomics data yielded 8,074 spectral features. The resulting unsupervised PCA model yielded a clear separation between the control and DA-CB treatment groups in the scores plot (Figure 2A). The tight clustering of the quality control samples in the center of the scores plot is significant, testifying to the high quality of the metabolomics data set. A supervised OPLS model (Figure 2B) yielded a similar level of group separation and identified features or metabolites that differentiated the two groups. The OPLS model was validated using a permutation test (n = 1000, p-value < 0.03) and determined to be of high quality given the R2 (0.990) and Q2 (0.959) values (Table S1). Overall, the PCA and OPLS models of the LC-MS metabolomics data set clearly demonstrate statistically significant DA-CB induced perturbations in the global cellular metabolome of Msm.

Figure 2.

(A) Principal component analysis (R2=0.535, Q2=0.391) with 5 principal components and (B) Orthogonal projection to latent structures discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA, R2=0.990, Q2=0.959, p-value < 0.03) models generated from the LC-MS metabolomics data set. Msm cells were treated with either 400 μM of DA-CB (green) or 10 μL of DMSO (Control, red). Quality control (QC) pooled samples combine 45 μL from each DA-CB and Control sample. Ellipses represent a 95% confidence limit of the normal distribution of each cluster.

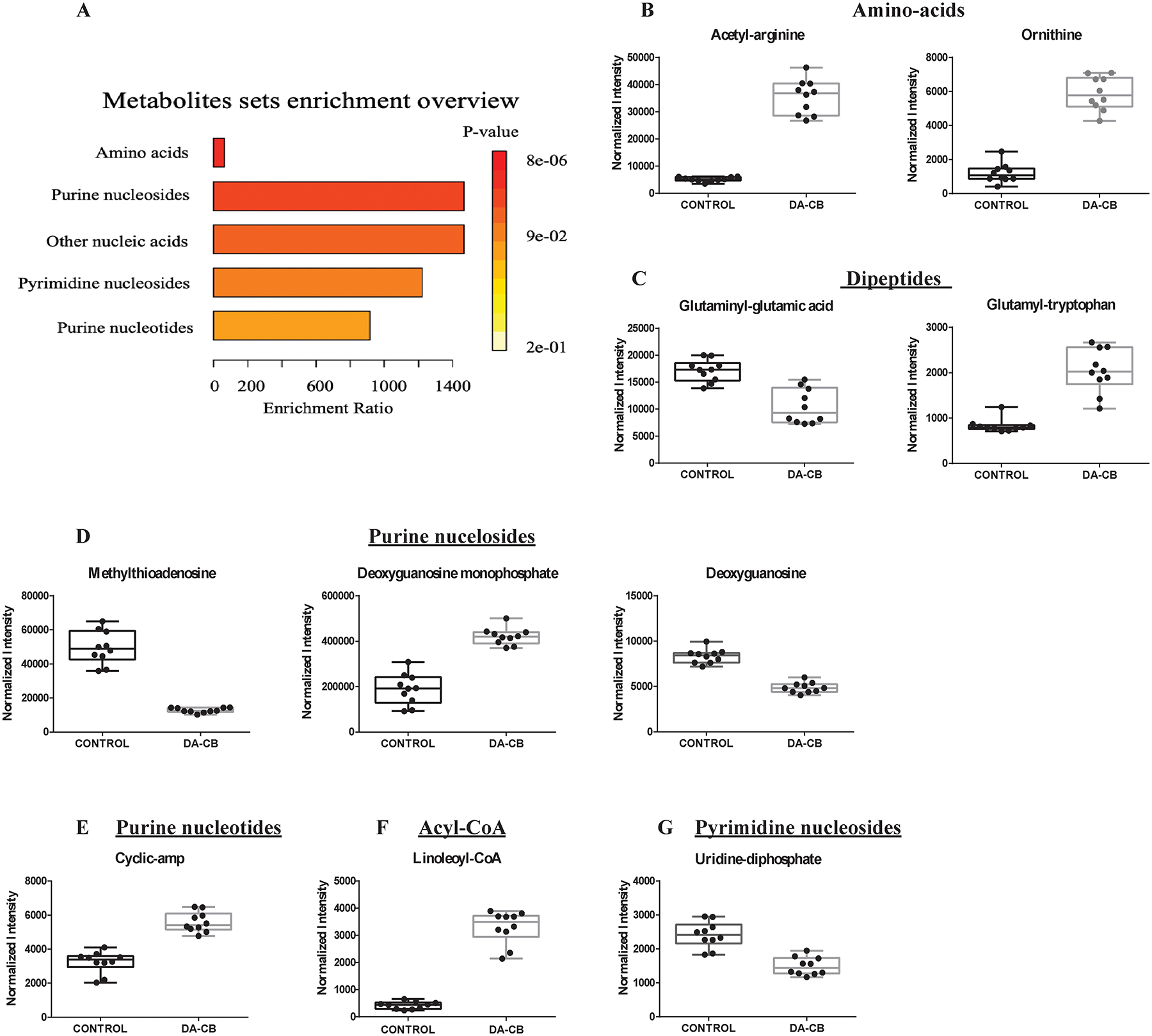

The entire LC-MS data set was curated to only include features with statistically significant group differences to identify metabolic pathways potentially affected by DA-CB. A total of 180 LC-MS features were deemed statistically significant based on a VIP score > 1.0, an FDR-corrected p-value < 0.05, and a fold change > 1.5. The exact mass, isotopic pattern, and fragmentation pattern for these 180 features were submitted to Progenesis® QI metabolomics software to identify 26 putative metabolites altered by DA-CB (Table 1). An enrichment analysis with MetaboAnalyst revealed that the top five metabolic pathway changes were related to amino acids, purine nucleosides, other nucleic acids, pyrimidine nucleosides, and purine nucleotides (Figure 3A). Box plots summarizing the relative concentration changes for the metabolites associated with these pathways are shown in Figures 3B–G. DA-CB treatment resulted in a general increase in the concentration of acyl-CoA, amino acids, dipeptides, and purines. Conversely, concentrations of uridine-diphosphate, methylthioadenosine, and deoxyguanosine monophosphate were significantly decreased. Encouragingly, the preliminary NMR metabolomics analysis were also consistent with and support these LC-MS metabolomics outcomes. NMR and MS metabolomics analysis of the same biological samples detect distinct sets of metabolites that have been previously shown to provide complementary information.52

Table 1.

Metabolites significantly altered by a DA-CB treatment.

| Pathway | Class | Subclass/direct parent | Accepted Description | VIP1 OPLS | p-value2 | FDR-corrected p-value3 |

FC4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrimidine metabolism | pyrimidine nucleotide | Pyrimidine nucleotide sugars | UDP-GlcNAc | 1.44 | 3.04E-07 | 6.74E-07 | 0.49 |

| pyrimidine nucleotside | Pyrimidine ribonucleoside | Uridine-diphosphate | 1.29 | 6.91E-06 | 9.31E-06 | 0.62 | |

| organooxygen compounds | carbohydrates and conjugates/acyl amino sugars | Beta-mannose-acetylglucosamine | 1.56 | 1.55E-05 | 2.00E-05 | 10.48 | |

| pyrimidine nucleotide | pyrimidine nucleotide sugars/same | Deoxythymidine diphosphate-l-rhamnose | 1.31 | 1.05E-06 | 1.72E-06 | 0.59 | |

| Aminoacid metabolism | carboxylic acids and derivatives | aminoacids,peptides/aminoacids | Ornithine | 1.47 | 1.23E-10 | 5.43E-10 | 4.91 |

| Acetyl-arginine | 1.59 | 1.42E-11 | 1.08E-10 | 6.82 | |||

| aminoacids,peptides/dipeptides | Glutaminylglutamic acid | 1.27 | 3.25E-05 | 3.73E-05 | 0.61 | ||

| Glutamyltryptophan | 1.59 | 5.53E-07 | 9.84E-07 | 2.45 | |||

| Hydroxyprolyl-Tyrosine | 1.43 | 3.27E-06 | 4.61E-06 | 1.85 | |||

| Tyrosyl-Hydroxyproline | 1.61 | 1.86E-11 | 1.08E-10 | 0.19 | |||

| Hydroxyprolyl-Proline | 1.52 | 2.24E-05 | 2.68E-05 | 4.81 | |||

| Amino acids, peptides, and analogues/Glutamine and derivatives | Hydroxyglutamine | 1.58 | 1.21E-06 | 1.88E-06 | 0.66 | ||

| Amino acids, peptides, and analogues / N-acyl-L-alpha-amino acids | Succinyl-diaminopimelate | 1.47 | 5.71E-07 | 9.84E-07 | 0.56 | ||

| Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis | organooxygen compounds | carbohydrates and conjugates/Aminocyclitol glycosides | Alpha-Glucosaminyl-myo-inositol | 1.58 | 5.83E-08 | 1.51E-07 | 6.43 |

| Lipid metabolism | glycerophospholipid | glycerophosphoethanolamine | LysoPE(0:0,20:4) | 1.62 | 1.07E-11 | 1.08E-10 | 7.36 |

| fatty acyls | Fatty acid esters | Hydroxyoctanoyl carnitine | 1.57 | 2.16E-03 | 2.23E-03 | 35.24 | |

| oxidation of fatty acids | fatty acyls | fatty acyl thioester/long chain fatty acyl-coa | Linoleoyl-CoA | 1.60 | 2.09E-11 | 1.08E-10 | 7.79 |

| Pantothenate and coa biosynthesis | organooxygen compoundns | alcohols/secondary alcohols | Pantothenic acid | 1.48 | 1.66E-06 | 2.45E-06 | 0.44 |

| Purine metabolism | Purine nucleosides | Purine deoxyribonucleosides | Deoxyguanosine | 1.51 | 2.17E-08 | 6.12E-08 | 0.58 |

| cyclic purine nucleotides | Cyclic AMP | 1.20 | 9.41E-08 | 2.24E-07 | 1.73 | ||

| Purine nucleotide | Purine nucleotide sugars | NADHX | 1.61 | 5.79E-14 | 1.51E-12 | 0.25 | |

| Purine deoxyribonucleotides | Deoxyguanosine-monophosphate | 1.30 | 2.17E-08 | 6.12E-08 | 2.23 | ||

| dinucleotides | dinucleotides/dinucleotides | Diadenosine diphosphate | 1.62 | 9.75E-14 | 1.51E-12 | 244.79 | |

| organooxygen compoundns | carbohydrates and conjugates/pentose phosphates | Inosine-phosphate | 1.27 | 5.82E-04 | 6.23E-04 | 2.09 | |

| deoxyribonucleosides | Purine ribonucleosides/deoxy-thionucleosides | Methylthioadenosine | 1.59 | 6.38E-10 | 2.47E-09 | 0.26 | |

| Riboflavin metabolism | pteridines and derivatives | alloxazines/flavins | Riboflavin | 1.34 | 2.95E-04 | 3.27E-04 | 0.57 |

VIP score - Variable importance in projection score from OPLS-DA model

p-value - Student’s t-test p-value,

FDR - corrected p-value using Benjamini-Hochberg method

FC - fold change calculated using the average of integrated peak area from DA-CB treatments divided by the average of the integrated peak area from control samples.

Figure 3.

(A) An enrichment analysis using the 26 metabolites with statistically significant changes in Msm cells following a DA-CB treatment. Representative box plots for significantly altered metabolites corresponding to the following enriched pathways: (B) amino acids, (C) dipeptides, (D) purine nucleosides, (E) purine nucleotides, (F) acyl-CoA and (G) pyrimidine nucleosides. DA-CB indicates DA-CB treated Msm cells and Control indicates only DMSO treated Msm cells.

Lipidomics identified DA-CB-associated alteration of wax monoesters, branched chain fatty acids, and mycolic acids.

We characterized the lipidome changes to further explore the impact of DA-CB on Msm metabolism, especially given the predicted relationship between DA-CB and the mycolic acid inhibitor ETH. We employed our previously described LC-MS lipidomics protocol to maximize the coverage of the Msm lipidome to include mycolic acids.49 The same cellular extract samples were used for both the metabolomics and lipidomics experiments. The LC-MS data set was collected in both negative and positive ionization modes, which yielded 6,033 and 5,281 spectral features, respectively. Separate PCA and OPLS models were created from the two LC-MS lipidomics data sets to maximize the identification of all the lipids altered by DA-CB and to obtain a complete picture of the impact of DA-CB on Msm. Simply, we expected and observed different sets of lipids detected in the negative and positive ionization modes. Combining both data sets into a single statistical model would likely emphasize the highly altered lipids with the potential loss of moderately changing lipids, which was not advantageous. Both PCA models showed a clear separation between the DA-CB treatment and control groups and were statistically significant as evident by average R2 and Q2 values of 0.745 and 0.644, respectively (Figure 4, Table S1). Similarly, the OPLS models were statistically valid as assessed by p-values < 0.01 from a permutation test (n = 1000) and were of high quality based on average R2 and Q2 values of 0.992 and 0.980, respectively (Figures 4B, D, Table S1).

Figure 4.

(A) Principal component analysis (PCA) (R2=0.745, Q2=0.644) with 5 principal components and (B) Orthogonal projection to latent structures discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA, R2=0.992, Q2= 0.980, p-value < 0.01) models generated from the positive ionization mode LC-MS lipidomics data set. (C) PCA (R2=0.726, Q2=0.613) and (D) OPLS-DA (R2=0.996, Q2= 0.984, p-value < 0.01) models generated from the negative ionization mode LC-MS lipidomics data set. Msm cells were treated with either 400 μM of DA-CB (green) or 10 μL of DMSO (Control, red). Quality control (QC) pooled samples combine 45 μL from each DA-CB and Control sample. Ellipses represent a 95% confidence limit of the normal distribution of each cluster.

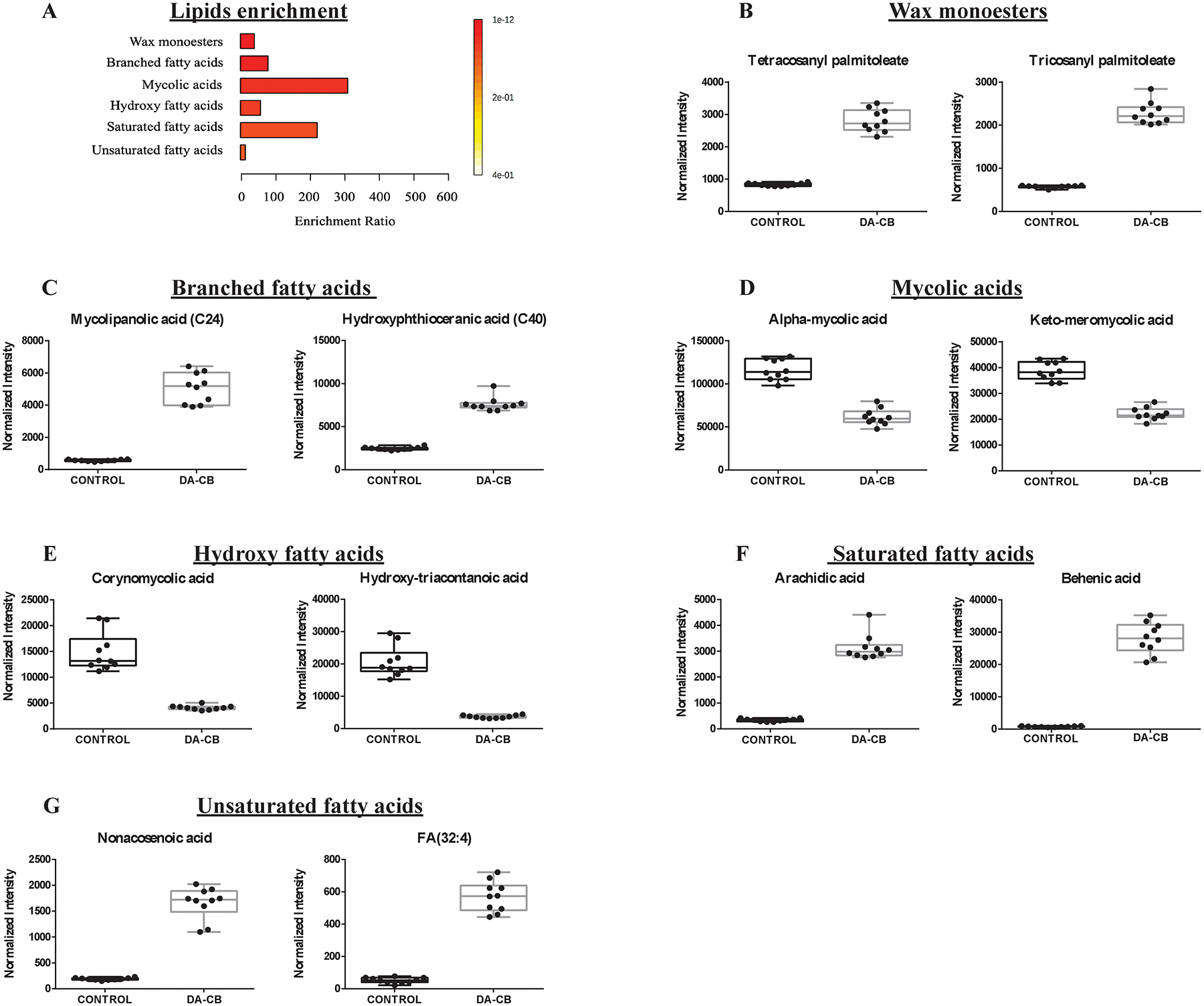

The lipidomics data set was key to the overall analysis of the metabolic impact of DA-CB and its comparison to ETH. Overall, the PCA and OPLS models for the lipidomics data sets demonstrated a significant DA-CB induced perturbations in the global cellular lipidome relative to the controls. The LC-MS features with VIP scores ≥ 1.0, FDR p-values < 0.05, and a fold change > 1.5 were selected to identify the key lipids that differentiated between the two groups. A total of 170 positive mode spectral features and 133 negative mode spectral features incurred a statistically significant change due to DA-CB. The exact mass, isotopic pattern, and fragmentation pattern for these selected features were submitted to Progenesis® QI metabolomics software to identify a total of 48 lipids. An enrichment analysis with MetaboAnalyst revealed that the top six (p-value < 0.001) lipidomic pathways, indicated with the lipid classification names were associated with wax monoesters, branched chain fatty acids, mycolic acids, and hydroxy, saturated, and unsaturated fatty acids (Figure 5A, Table 2). The representative lipid box plots summarizing the relative concentration changes for the lipids associated with these pathways are shown in Figures 5B–G. The nine wax monoesters (lipid subclass) increased substantially relative to control following DA-CB treatment (Figure 5B). Similarly, the six branched fatty acids (Figure 5C), the saturated (Figure 5F) and unsaturated fatty acids (Figure 5G) all increased because of DA-CB. Conversely, the four mycolic acids (keto-meromycolic acid [C81], alpha-mycolic acid [C80], 2-eicosyl-3-hydroxy-32-oxo-33-methyl-nonatetracontanoic acid [C70], and corynomycolic acid [C32], Figure 5D) and the hydroxy fatty acids (Figure 5E) decreased significantly compared to controls following DA-CB treatment. While the preliminary NMR metabolomics data set was limited to aqueous metabolites, changes in pre-cursor metabolites and water-soluble fatty acids still indicated a general increase in branched chain fatty acids due to DA-CB treatment consistent with these findings from the LC-MS lipidomics results.

Figure 5.

(A) An enrichment analysis using the 48 lipids with statistically significant changes in Msm cells following a DA-CB treatment. (B-G) Representative box plots for significantly altered lipids corresponding to the following enriched pathways: (B) Wax monoesters (C) branched chain fatty acids, (D) mycolic acids, and (E) hydroxy fatty acids, (F) saturated fatty acids, (G) unsaturated fatty acids. DA-CB indicates DA-CB treated Msm cells and Control indicates only DMSO treated Msm cells.

Table 2.

Lipids significantly altered by DA-CB treatment.

| Categories | Class | Subclass | Lipid maps (Common names) |

VIP OPLS1 | p-value2 | FDR-corrected p-value3 |

FC4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty acyls | Fatty acids | Branched chain fatty acids | Methyl-hexacosanoic acid | 1.25 | 2.90E-17 | 2.7748E-16 | 1609.95 |

| Diabolic acid | 1.23 | 5.05E-16 | 3.38179E-15 | 972.47 | |||

| Hydroxyphthioceranic acid (C40) | 1.25 | 1.33E-13 | 3.07911E-13 | 3.10 | |||

| Mycolipanolic acid (C24) | 1.24 | 1.45E-11 | 2.02569E-11 | 8.94 | |||

| Mycosanoic acid (C24) | 1.25 | 6.77E-16 | 3.7773E-15 | 80.14 | |||

| Hydroxy fatty acids | Corynomycolic acid | 1.18 | 4.01E-08 | 4.4431E-08 | 0.28 | ||

| Hydroxy-tetracosanoic acid | 1.17 | 4.65E-07 | 4.86822E-07 | 2.71 | |||

| Hydroxy-triacontanoic acid | 1.21 | 1.14E-09 | 1.33741E-09 | 0.18 | |||

| Lanoceric acid | 1.24 | 5.81E-14 | 1.62335E-13 | 6.77 | |||

| Mycolic acids | Eicosyl-hydroxy-oxo-methyl-nonatetracontanoic acid | 1.18 | 4.08E-06 | 4.20735E-06 | 0.58 | ||

| Tetracosyl-hydroxy-carboxy-octatriacontanoic acid | 1.18 | 1.28E-13 | 3.05092E-13 | 0.49 | |||

| Alpha-mycolic acid | 1.10 | 1.39E-09 | 1.60496E-09 | 0.53 | |||

| Keto meromycolic acid | 1.05 | 3.46E-10 | 4.37198E-10 | 0.57 | |||

| Saturated fatty acids | Arachidic acid | 1.25 | 6.52E-13 | 1.24799E-12 | 9.38 | ||

| Behenic acid | 1.25 | 5.83E-13 | 1.14791E-12 | 36.33 | |||

| Unsaturated fatty acids | Nonacosenoic acid | 1.24 | 1.24E-11 | 1.76927E-11 | 8.77 | ||

| Dotriacontenoic acid | 1.24 | 9.10E-12 | 1.32584E-11 | 3.36 | |||

| FA(28:2) | 1.24 | 1.12E-13 | 2.76861E-13 | 23.50 | |||

| FA(32:4) | 1.23 | 1.40E-12 | 2.40122E-12 | 10.91 | |||

| Fatty esters | Wax monoesters | Myristoleyl myristate | 1.25 | 2.00E-14 | 6.68573E-14 | 15.07 | |

| Myristyl linoleate | 1.25 | 2.03E-12 | 3.34994E-12 | 22.49 | |||

| Nonadecyl palmitoleate | 1.25 | 1.44E-08 | 1.63753E-08 | 46.80 | |||

| Oleyl palmitoleate | 1.25 | 4.17E-12 | 6.6483E-12 | 21.26 | |||

| Pentacosanyl palmitoleate | 1.25 | 3.25E-16 | 2.71997E-15 | 748.57 | |||

| Tetracosanyl palmitoleate | 1.24 | 6.94E-13 | 1.29192E-12 | 3.40 | |||

| Tricosanyl palmitoleate | 1.24 | 4.52E-14 | 1.31597E-13 | 3.99 | |||

| Glycerolipids | Diradylglycerols | Diacylglycerols | DG(14:1,14:1) | 1.25 | 2.32E-13 | 4.86543E-13 | 33.42 |

| DG(15:0,18:0) | 1.24 | 5.21E-10 | 6.46664E-10 | 2.09 | |||

| DG(17:1,22:0) | 1.25 | 1.15E-14 | 4.04228E-14 | 3.39 | |||

| DG(19:0,22:0) | 1.24 | 1.38E-13 | 3.07911E-13 | 2.28 | |||

| Triradylglycerols | Triacylglycerols | TG(12:0,12:0,18:3) | 1.25 | 8.19E-12 | 1.21997E-11 | 21.71 | |

| TG(12:0,12:0,18:4) | 1.25 | 3.11E-14 | 9.67007E-14 | 48.57 | |||

| TG(12:0,12:0,20:4) | 1.25 | 4.03E-11 | 5.39532E-11 | 21.09 | |||

| TG(12:0,14:1,18:4) | 1.25 | 2.97E-11 | 4.0635E-11 | 10.25 | |||

| TG(18:0,20:4,22:6) | 1.22 | 1.05E-04 | 0.000106722 | 43.49 | |||

| TG(18:2,22:3,22:6) | 1.25 | 7.93E-18 | 1.06267E-16 | 3.28 | |||

| TG(18:3,20:5,22:0) | 1.24 | 1.98E-20 | 1.32374E-18 | 16.52 | |||

| Glycerophospholipids | Glycerophosphotidicacid | Diacyl-glycerophhosphotidic acid | PA(18:1,18:4) | 1.24 | 3.53E-15 | 1.57472E-14 | 5.47 |

| Glycerophospho-choline | Diacyl-glycerophhospho-choline | PC(22:0,24:1) | 1.24 | 1.14E-19 | 2.55173E-18 | 4.50 | |

| Glycerophospho-ethanolamine | Diacyl-glycerophhospho-ethanolamie | PE(18:0,18:4) | 1.24 | 3.18E-14 | 9.67007E-14 | 402.91 | |

| PE(19:0,18:3) | 1.23 | 8.80E-11 | 1.15588E-10 | 3.08 | |||

| PE(P-16:0,20:3) | 1.23 | 6.60E-10 | 8.03472E-10 | 8.36 | |||

| Glycerophospho-inositol | Diacyl-Glycerophospho-inositol | PI(22:1,21:0) | 1.24 | 1.49E-10 | 1.91703E-10 | 21.50 | |

| Glycerophosphoserine | Diacylglycerophosphoserine | PS(20:3,0:0) | 1.21 | 8.33E-15 | 3.09983E-14 | 0.33 | |

| Oxidized glycerophospholipid | Oxidized glycerophosphates | PON-PG | 1.25 | 5.98E-15 | 2.35554E-14 | 1314.68 | |

| Saccharolipids | Acyltrehaloses | NA | AC2SGL(18:0,30:0) | 1.21 | 8.69E-13 | 1.53137E-12 | 2.55 |

| NA | DAT(16:0,24:0) | 1.25 | 1.18E-17 | 1.32219E-16 | 3.83 | ||

| NA | DAT(16:0,25:0) | 1.25 | 4.22E-20 | 1.415E-18 | 5.01 |

VIP score - Variable importance in projection score from OPLS-DA model

p-value - Student’s t-test p-value,

FDR - corrected p-value using Benjamini-Hochberg method

FC - fold change calculated using the average of integrated peak area from DA-CB treatments divided by the average of the integrated peak area from control samples.

Proteomics identified the pentose phosphate pathway, the biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids, and pyrimidine metabolism as being altered by DA-CB.

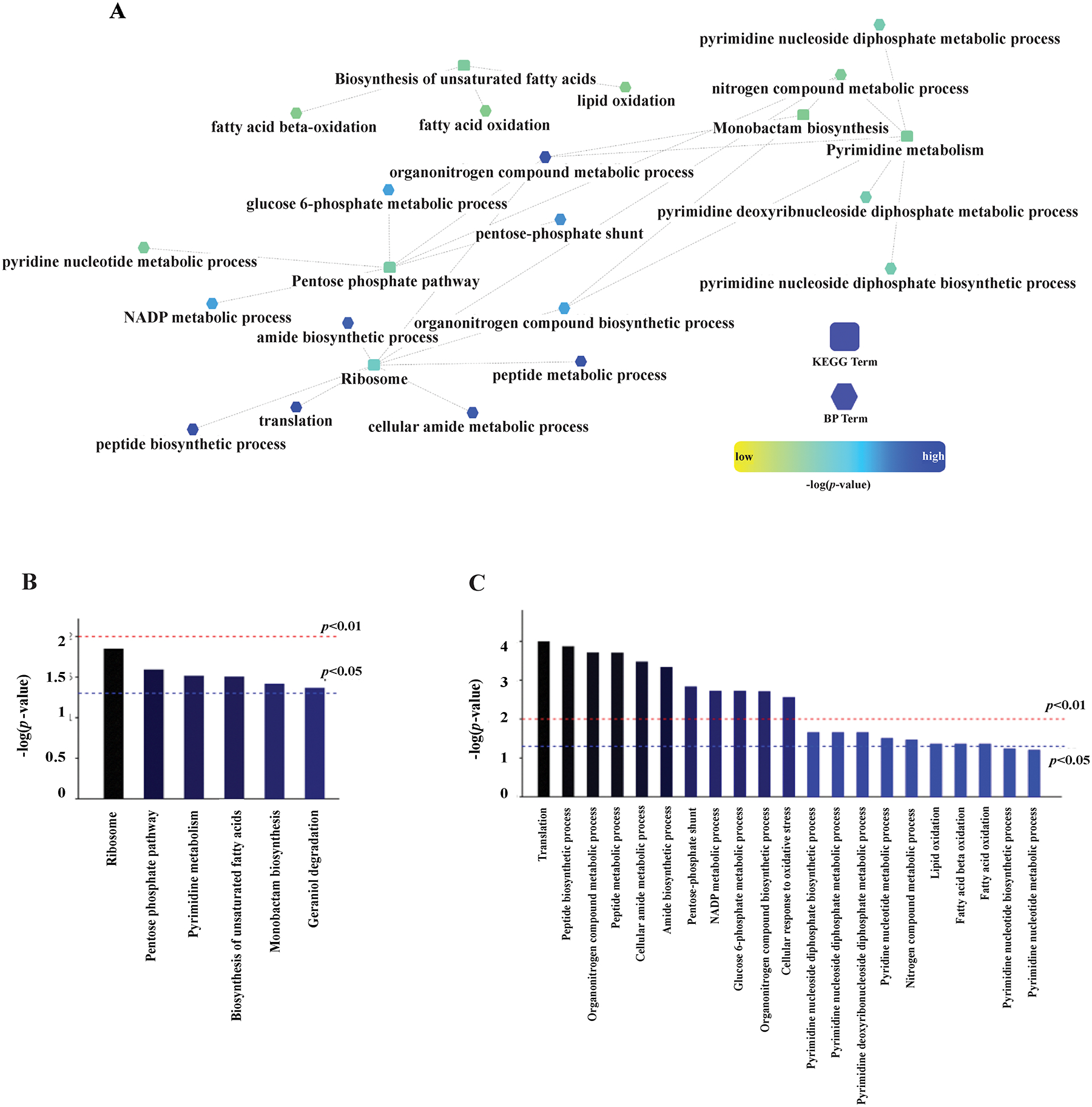

A total of 858 proteins were detected with at least one unique peptide and a 1% FDR from a label-free untargeted LC-MS proteomic profiling of Msm following DA-CB treatment. A volcano plot for all the detected proteins is displayed in Figure S3. Curation of the proteomics data set for significant changes due to DA-CB identified 123 differentially expressed proteins with fold change > 1.2 and p-value < 0.05, which included 53 proteins with an FDR corrected p-value < 0.05 (Table S2). The expression of 107 proteins decreased while 16 proteins increased due to the DA-CB treatment. A string network of the differentially expressed proteins is displayed in Figure S4. Interestingly, the upregulated proteins were primarily associated with three pathways: alpha-linolenic acid metabolism, geraniol degradation, and monobactam biosynthesis. The downregulated proteins were mainly associated with four pathways: pentose phosphate metabolism, biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids, pyrimidine metabolism, and alteration of ribosomal proteins. Importantly, a proteomic profile identifies only the relative change in the expression level of a protein and not a change in the activity of the protein. While an up- or down-regulation may suggest a corresponding change in activity, the only definitive finding is a perturbation in the pathway in response to DA-CB. While it is also tempting to interpret a correlated change between a protein and its metabolite/lipid substrate as a change in protein activity, there is still no direct experimental evidence that such a alteration has occurred.

A biological process enrichment-network map was created using the 123 proteins with significantly altered expression levels to understand the key metabolic pathways effected by DA-CB (Figure 6A). The statistically significant (p-value < 0.05) Genome Ontology-Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (GO-KEGG) term clusters included proteins from the ribosome, pentose phosphate pathway, biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids and pyrimidine metabolism (Figure 6B). The enriched biological processes (Figure 6C) also agreed with the significant alterations (p-value < 0.05) in pyrimidine and pyridine biosynthesis, pentose phosphate shunt, and fatty acid metabolism. Furthermore, the genes corresponding to the enriched GO-KEGG pathways were identified. The metabolic pathways that were also enriched in the metabolomics and lipidomics data sets are shown in bold in Table 3. The altered metabolic pathways implicated by all three omics data sets are the following: pentose phosphate pathway, pyrimidine metabolism, amino acid transport, biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids, α-linolenic acid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, biosynthesis of amino acids, pantothenate and coenzyme A (CoA) biosynthesis. The proteins associated with the pentose phosphate pathway, pyrimidine metabolism and the biosynthesis of amino acids, (i.e., Tal, HisF, HisG and GlnA) were significantly decreased. The proteins involved in the biosynthesis of fatty acids, α-linolenic acid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, fatty acid degradation, and pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis were also significantly decreased (Table 3). This decrease in proteins associated with fatty acid metabolism could be in response to the observed accumulation of various fatty acids, which has been associated with cellular toxicity.53, 54

Figure 6.

(A) A Cytoscape (https://cytoscape.org/) network generated from the 123 differentially expressed proteins in the proteomics data set and using the Msm protein database. Nodes using a square symbol indicate altered pathways from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database, while nodes with a hexagon symbol indicate altered biological processes (BP). A summary of the (B) KEGG and (C) BP terms that were significantly altered according to the network analysis of the proteomics data set.

Table 3.

TOP PROTEIN PATHWAYS AND ASSOCIATED GENES ALTERED BY DA-CB TREATMENT.1

| PATHWAY NAME | Pathway KEGG ID | Protein description | UNIPROT Gene NAMES | FC2 | p-value | FDR-corrected p-value3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIBOSOMAL PROTEINS | msm03010 | 30S ribosomal protein | rpsK | 0.55 | 2.41E-03 | 2.42E-02 |

| 30S ribosomal protein | rpsR2 | 0.58 | 2.47E-02 | 9.88E-02 | ||

| 50S ribosomal protein | rplP | 0.71 | 2.46E-02 | 9.88E-02 | ||

| 30S ribosomal protein | rpsl | 0.61 | 4.81E-03 | 3.81E-02 | ||

| 30S ribosomal protein | rpsS | 0.72 | 2.43E-02 | 9.88E-02 | ||

| 30S ribosomal protein | rpsM | 0.74 | 2.91E-02 | 1.09E-01 | ||

| PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY | msm00030 | 2-dehydro-3-deoxy-phosphogluconate aldolase | eda | 0.63 | 5.81E-03 | 4.25E-02 |

| 6-phosphogluconolactonase | pgl | 0.6 | 1.05E-02 | 6.05E-02 | ||

| Transaldolase | tal | 0.71 | 1.57E-02 | 8.09E-02 | ||

| Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase | zwf | 0.54 | 3.67E-03 | 3.22E-02 | ||

| PYRIMIDINE METABOLISM | msm00240 | Orotate phosphoribosyltransferase | pyre | 0.57 | 3.87E-02 | 1.28E-01 |

| dTMP kinase | MSMEG_1873 | 0.65 | 1.57E-02 | 8.09E-02 | ||

| Thioredoxin | trx | 0.68 | 3.05E-02 | 1.09E-01 | ||

| Cytosine deaminase | MSMEG_4687 | 0.72 | 3.70E-02 | 1.24E-01 | ||

| BIOSYNTHESIS OF UNSATURATED FATTY ACIDS | MSM01040 | Short-chain dehydrogenase | MSMEG_0779 | 0.65 | 2.11E-03 | 2.30E-02 |

| Acyl-CoA oxidase | MSMEG_4474 | 0.7 | 9.87E-03 | 5.95E-02 | ||

| MONOBACTAM BIOSYNTHESIS | msm00261 | Dihydrodipicolinate reductase | dapB | 0.67 | 1.61E-02 | 8.09E-02 |

| Sulfate adenylyltransferase subunit | cysD | 1.36 | 2.70E-02 | 1.06E-01 | ||

| GERANIOL DEGRADATION | msm00281 | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | MSMEG_1048 | 0.67 | 2.05E-02 | 9.19E-02 |

| Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | MSMEG_4715 | 1.39 | 4.46E-02 | 1.41E-01 | ||

| Acyl-coA-dehydrogenase | fadE5 | 1.87 | 2.24E-03 | 2.38E-02 | ||

| ALPHA-LINOLENIC ACID METABOLISM | msm00592 | Acyl-CoA oxidase | MSMEG_4474 | 0.7 | 9.87E-03 | 5.95E-02 |

| FATTY ACID METABOLISM | msm01212 | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | MSMEG_1048 | 0.67 | 2.05E-02 | 9.19E-02 |

| Short-chain dehydrogenase | MSMEG_0779 | 0.65 | 2.11E-03 | 2.30E-02 | ||

| Acyl-CoA oxidase | MSMEG_4474 | 0.7 | 9.87E-03 | 5.95E-02 | ||

| BIOSYNTHESIS OF AMINO ACIDS | msm01230 | Dihydrodipicolinate reductase | dapB | 0.67 | 1.61E-02 | 8.09E-02 |

| Transaldolase | tal | 0.71 | 1.57E-02 | 8.09E-02 | ||

| Imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase subunit hisF | hisF | 0.54 | 1.91E-03 | 2.15E-02 | ||

| ATP phosphoribosyltransferase | hisG | 0.57 | 3.14E-03 | 1.66E-03 | ||

| Glutamine synthetase | glnA | 0.52 | 9.43E-05 | |||

| PANTOTHENATE AND COA BIOSYNTHESIS | msm00770 | Holo-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase | acpS | 0.69 | 3.06E-02 | 1.09E-01 |

| FATTY ACID BIOSYNTHESIS | msm00061 | Short-chain dehydrogenase | MSMEG_0779 | 0.65 | 2.11E-03 | 2.30E-02 |

| FATTY ACID DEGRADATION | msm00071 | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | MSMEG_1048 | 0.67 | 2.05E-02 | 9.19E-02 |

| Acyl-CoA oxidase | MSMEG_4474 | 0.7 | 9.87E-03 | 5.95E-02 | ||

| AMINO SUGAR AND NUCLEOTIDE SUGAR METABOLISM | msm00520 | Polyphosphate glucokinase | MSMEG_2760 | 0.34 | 1.30E-05 | 3.25E-04 |

Bolded text identifies pathways that were also identified with the metabolomics data set (Table 1)

FC - fold change calculated using the average of integrated peak area from DA-CB treatments divided by the average of the integrated peak area from control samples.

FDR- corrected p-value using Benjamini-Hochberg method

Integration of metabolomics and proteomics data demonstrates DA-CB altered pathways are associated with nitrogen-containing metabolites.

Both the metabolomics and proteomics data sets revealed that pyrimidine biosynthesis was affected by DA-CB treatment (Figures 3A, 6B). The proteins involved in pyrimidine metabolism pathway orotate phosphoribosyltransferase (PyrE), thymidylate kinase (dTMP kinase, MSMEG_1873), thioredoxin (Trx), cytosine deaminase (MSMEG_4687) were significantly decreased in DA-CB treated cells compared to controls (Table 3). PyrE plays a vital role in pyrimidine biosynthesis, since it synthesizes orotidine 5′-monophosphate, which is a key precursor in the de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway.55 PyrE also catalyzes the conversion of α-D-5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate and orotate into pyrophosphate and orotidine 5′-monophosphate, respectively. The metabolomics data was also consistent with the down-regulation of PyrE since pyrimidine metabolites downstream of PyrE were significantly decreased. For example, uridine-diphosphate and UDP-GlcNAC were decreased in DA-CB treated cells (Table 1). Thus, a disruption in pyrimidine biosynthesis may contribute to the MoA of DA-CB in arresting Msm growth. Although the proteomics enrichment results did not identify purine metabolism as the most impacted pathway, the metabolomics data set did. DA-CB depleted methyl-thioadenosine and deoxyguanosine and increased cyclic AMP and deoxy guanosine-monophosphate. Proteins associated with purine metabolism, such as ATP-synthase subunit (AtbB), pyrophosphatase (RdgB), and phosphoribosylformylglycinamide cyclo-ligase (PurM) were downregulated in DA-CB treated cells. Notably, AtpB is a key component of the proton channel and an important antimycobacterial drug target.56, 57 DA-CB downregulated AtpB 1.8-fold with a p-value < 0.05. Additionally, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) was among the most altered pathways identified in the proteomics data set. The PPP provides precursors for the biosynthesis of nucleotides (i.e., purine and pyrimidine metabolism) and amino acids.58 PPP proteins such as 2-dehydro-3-deoxy-phosphogluconate aldolase (Eda), phospho-gluconolactonase (Pgl), transaldolase (Tal), and glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase (Zwf) were downregulated in the presence of DA-CB. The PPP is upstream of nucleotide production, and the overall alteration in pyrimidines and purines (i.e., nucleotide biosynthesis) could be due to the PPP depletion associated with DA-CB.

Our metabolomics data revealed that amino acid metabolism was the top enriched pathway in response to a DA-CB treatment (Figure 3A). The metabolites identified in this pathway that included acetyl-arginine and ornithine were all increased with the addition of DA-CB (Figure 3B). Some of the observed amino acid changes were also correlated with a downregulation in proteins related to the biosynthesis of amino acids, which included Tal (which also has a role in PPP), imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase subunit (HisF), ATP phosphoribosyltransferase (HisG), and glutamine synthase (GlnA) (Table 3). GlnA is an essential Msm protein with a role as a global nitrogen metabolism regulator.59 Nitrogen metabolism plays a central role in all bacteria, and our proteomics data identified the organo-nitrogen metabolic process as the third most altered biological process following treatment with DA-CB (Figure 6C). Proteins associated with ribosome, pyrimidine, purine, and amino acid biosynthesis were all altered due to DA-CB. Although major alterations of ribosomal proteins were not inferred from the metabolomic or lipidomic results, some of the affected ribosomal proteins are known to be cell wall associated in Msm.60 The 30S and 50S ribosomal proteins found in the cell wall (RpsR, RplP, RpsM) were decreased due to DA-CB treatment.

Integration of lipidomics and proteomics data demonstrates DA-CB depleted fatty acids and altered proteins involved in cell wall biosynthesis.

Alterations in fatty acid metabolism comprised the most common pathway changes inferred from the proteomics and lipidomics data sets. Evidence of an altered lipid metabolism was also present in the metabolomics data set. The biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids and fatty acid metabolism were among the most impacted pathways in the proteomics data set. Fatty acid biosynthesis and degradation were also in the enriched pathways (Table 3). The top six enhanced pathways from the lipidomics data set included five different classes of fatty acids: branched chain fatty acids, hydroxy, unsaturated, and saturated fatty acids, and mycolic acids (Figure 5). Fatty acid biosynthesis is more complicated in mycobacteria and corynebacteria compared to other bacterial species owing to the presence of both the FAS type I and type II pathways.61 In these pathways, fatty acids are synthesized by repeated cycles of transacylation.62

CoAs and acyl carrier proteins (ACPs), which are essential for priming and extending the growing acyl chain, are the two most important components in fatty-acid biosynthesis.61, 62 Indeed, our metabolomics and proteomics data showed alterations in CoA metabolites and ACPs, which suggests DA-CB may be targeting FAS components. For example, linoleoyl-CoA was increased (Figure 3F) and pantothenic acid was decreased (Table S1) in DA-CB treated cells. Pantothenic acid is the key precursor for the biosynthesis of CoA. CoA is an essential cofactor involved in a myriad of metabolic processes that includes phospholipid biosynthesis, and both the degradation and synthesis of fatty acids.63 The depletion in pantothenic acid could be attributed to alterations in acyl-CoA metabolites (i.e., accumulation of linoleoyl-CoA). ACPs are important for acyl chain elongation and fatty acid biosynthesis and are downregulated in DA-CB treated cells. Acyl-CoA oxidase (MSMEG_4474), which is involved in the utilization of fatty acids as carbon sources via beta oxidation, was also downregulated due to DA-CB. In contrast, two acyl-CoA dehydrogenases (FadE5, MSMEG_4715) were significantly upregulated in DA-CB treated cells. Acyl-CoA dehydrogenases introduces unsaturation into the carbon chains during lipid metabolism, which correlates with the observed accumulation of unsaturated fatty acids in DA-CB treated cells. Recently, Chen et al. (2020) reported that FadE5 from Mtb and Msm contributed to drug resistance.64

Our lipidomics data set showed a significantly lowered production of mycolic acids (Figure 5D, Table 2). This is consistent with our prior observation (Figure 1) that a treatment with either DA-CB or ETH was associated with similar global metabolomics changes, which, in turn, suggests a shared general MoA that includes disrupting mycolic acids biosynthesis. The depletion in mycolic acid synthesis also implicates FAS-I and FAS-II. Importantly, the FAS-II pathway is the committed step to mycolic acid biosynthesis. In total, our multi-omics data provides strong evidence that DA-CB impacts mycolic acid and cell wall biosynthesis through the inhibition of specific enzyme(s) within the FAS pathways. Nataraj et al. (2015) states that the vast majority of the genes involved in mycolic acid biosynthesis are essential for viability and virulence and therefore important targets for drug development.65–68 Indeed, changes in the structure or composition of mycolic acids have been associated with a modification in cell wall permeability and the attenuation of pathogenic mycobacterial strains.60 Type I polyketide synthase (pks13) and fatty acyl-AMP ligase (fadD32) are key proteins in the synthesis of mycolic acids and were identified as essential proteins for the viability of Msm and Mtb. The biosynthesis of mycolic acids is catalyzed by proteins encoded by the fadD32-pks13-accD4 cluster.69, 70 The observation that corynomycolic acid and keto-meromycolic acid were both decreased suggests Pks13 may be important to the MoA of DA-CB.71, 72 The accumulation of lipid intermediates and the downregulation of the corresponding enzymes as described above in detail further implicates the involvement of the Pks13 complex with the MoA of DA-CB.

Lastly, our lipidomics identified wax monoesters as the most altered lipid pathway (Figure 5A). Wax monoesters are known to be synthesized when the mycobacteria are exposed to stress (Figure 5B).73 Thus, our observed increase in wax monoesters implies a stress response in Msm cells that is induced by a DA-CB treatment, and facilitated by the accumulation of FAS-I and FAS-II metabolites that provide substrates for the stress response. In addition, our proteomics data showed that the two superoxide dismutase enzymes (SodA, MSMEG_6636) were significantly downregulated in DA-CB treated cells. The superoxide dismutases protect the cells against oxidative stress by scavenging superoxide, which contributes to bacterial pathogenicity.74 Overall, these results suggest DA-CB induces oxidative stress within mycobacteria, perhaps by downregulating superoxide dismutases that protects cells against oxidative stress.

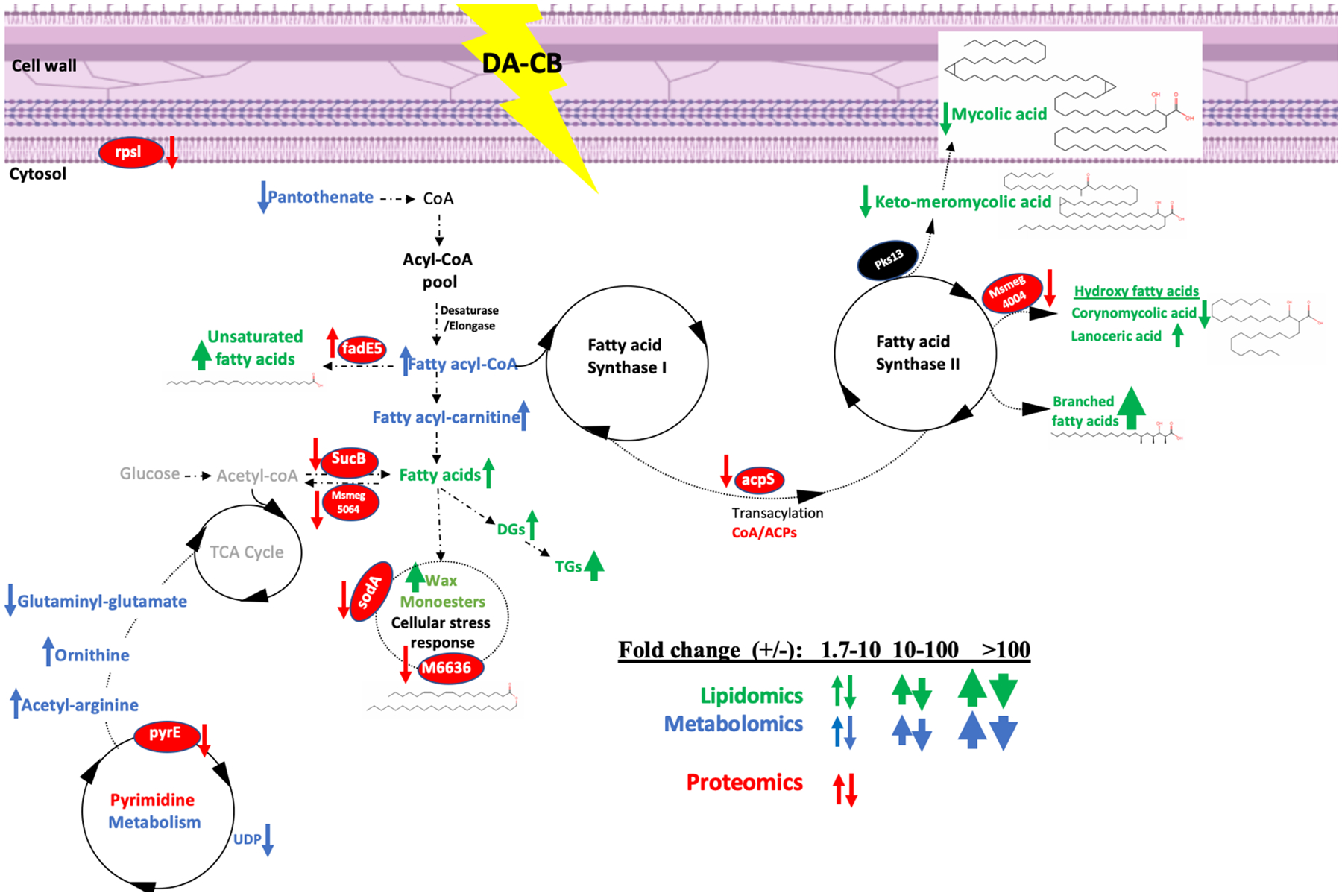

Multi-omics results show DA-CB effects fatty acid biosynthesis and pyrimidine biosynthesis.

The pathways common to the proteomics, metabolomics, and lipidomics data sets were combined into a single consensus integrated network (Figure 7). This integrated metabolic pathway provides a clear overview of the system-wide impact of a DA-CB treatment on Msm and identifies FAS metabolism as the focal point of DA-CB activity. The alteration in panthothenate-CoA biosynthesis and pyrimidine metabolism, and the downregulation of acyl carrier protein synthase (AcpS) further supports FAS metabolism as the target of DA-CB inhibition. Panthothenate-CoA biosynthesis and pyrimidine metabolism influence the fatty acyl-CoA pool, which supplies FAS-I, FAS-II, and mycolic acid biosynthesis. AcpS is also an important component of the FAS-I and FAS-II systems. Four (i.e., Rpsl, SodA, SucB, PyrE) other proteins colored red in Figure 7 have been previously identified as being encoded by essential Msm genes (Table S4).76, 77

Figure 7.

A schematic of an integrated network of the multi-omics data sets summarizing the consensus changes in the Msm lipidome (green), metabolome (blue), and proteome (red) resulting from a DA-CB treatment. An up arrow indicates an increase in DA-CB treated cells and a down arrow indicates a decrease. The relative thickness of the arrow indicates the range of the fold change for the lipid, metabolite, or protein (insert). A molecule colored black was not detected or altered by DA-CB but was included to highlight important nodes or to connect to other observed nodes.

To provide further support for our consensus integrated network (Figure 7), a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated between each of the 26 metabolites, 48 lipids, and 123 proteins that were significantly altered by DA-CB. A hierarchical clustered heatmap that summarizes the entire set of pairwise correlation coefficient is shown in Figure S5. The heatmap shows a strong positive or negative correlation between all the significantly altered metabolites, lipids, and proteins. A network map based on the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient for the 61 metabolites, lipids, and proteins depicted in Figure 7 is shown in Figure S6. The network identified 51 tightly interconnected molecules demonstrating a unified cellular response to the DA-CB treatment and the accuracy of the consensus integrated network. For example, alpha-mycolic acid is positively correlated with all other mycolic acids and negatively correlated with triacylglycerols (i.e., TG(12:0,12:0,20:4). Corynomycolic acid is positively correlated with hydroxy-triacontanoic acid (i.e., hydroxy fatty acids) and negatively correlated with PE(18:0,18:4) (i.e., diacyl-glycerophhospho-ethanolamie). UDP-GlcNAc and deoxythymidine diphosphate-1-rhamnose (i.e., pyrimidine nucleotides) are both negatively correlated with hydroxy-tetracosanoic acid (i.e., hydroxy fatty acids lipids) and myristyl myristate (i.e., a wax monoester).

Overall, our multi-omics data provides complementary lines of evidence that strongly implicates a FAS enzyme as the main inhibitory target of DA-CB in mycolic acid biosynthesis. Specifically, the terminal FAS-II Claisen condensation catalyzed by Pks13 and the associated FadD32 protein complex are potential candidates for the lethal target of DA-CB. In this regard, DA-CB may function through a direct enzyme inhibition or by the modification of the structure of a lipid precursor. A further investigation into the roles that acyl-CoA oxidase, FadE5, ACP, and cell wall ribosomal proteins (rplP, rpsM) may contribute to the MoA of DA-CB would enhance our understanding of anti-tubercular drugs that target cell wall biosynthesis. AcpS is not an essential gene; however, its downregulation affects transacylation and the further synthesis of FAS-II metabolites such as hydroxy and branched chain fatty acids that are important to mycolic acid biosynthesis (Table S4).76

Conclusion

In summary, we report the elucidation of a probable MoA for DA-CB, an antimycobacterial fatty acid analogue.15, 16 A multi-omics approach that combined lipidomics, metabolomics, and proteomics provided numerous, reinforcing and complementary results. Our integrated metabolomics, lipidomics, and proteomics analysis identified alterations in the FAS-II system, specifically in the terminal steps of mycolic acid biosynthesis. We also observed contributing alterations in pyrimidine and amino acids synthesis, and our integrated lipidomics and proteomics analysis identified alterations in FAS, specifically in mycolic acid biosynthesis. A consensus network (Figure 7) integrated these multi-omics data sets and provided a system-wide view of the cellular impact of DA-CB on the metabolome of Msm. The similarity in the global metabolic perturbations induced by both DA-CB and ETH, a known inhibitor of mycolic acid biosynthesis, provides further support for our proposed MoA.27, 78 However, the inhibited enzyme is different from InhA, the target of ETH, since we observed an overproduction (instead of a decrease) in hydroxy- and branched chain fatty acids. This outcome also confirms our original hypothesis that a fatty acid analogue like DA-CB could interrupt fatty acid synthesis or processing, which would lead to mycobacterial cell death. Our proposed MoA is expected to guide future investigations into the confirmation of the precise lethal target(s) of DA-CB. Finding the lethal target of a novel drug often requires intensive dedicated research. For example, the discovery that D-Ala-D-Ala ligase was the lethal target of DCS came 50 years after the introduction of the drug.35 However, recent developments in omics analysis may hasten this pace.

DA-CB also provides a unique opportunity to leverage click chemistry and to identify target proteins. DA-CB was selected from among a group of related analogues for further study because of its efficacy and because we and others have shown DA-CB and related cyclobutenes undergo rapid and “biorthogonal” click modification in the form of inverse electron-demand Diels-Alder cycloadditions with biotinylated 1,2,4,5-tetrazines.79 The ability to specifically address DA-CB, or any derived biosynthetic intermediates will provide a unique opportunity to study the localization and/or conjugation of the fatty acid analogues within mycobacteria by using a pull-down assay or chemical cross-linking.17 As described in the literature, labeling the fatty acid analogue enables tracking of the altered pathways.30 The same approach may be used for DA-CB, in order to track its incorporation into the fatty acid biosynthetic FAS-I and FAS-II machinery via a fatty acid CoA analogue. Furthermore, the future experiment of labelling DA-CB will enable us to determine its uptake to understand lipid synthesis changes in Msm and Mtb.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funding from the Redox Biology Center (P30 GM103335, NIGMS, RP), and the Nebraska Center for Integrated Biomolecular Communication (P20 GM113126, NIGMS, ASM, ALL, RP). The research was performed in facilities renovated with support from the National Institutes of Health (RR015468-01, ITS, ASM, ALL, DM, BWE, PHD, RP). This project was also supported by the Nebraska Agricultural Experiment Station with funding from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NEB-39-178 and NEB-39-179, RGB).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/

Experimental details, one figure displaying the interaction network of proteins altered by DA-CB treatment, and three tables listing a summary of quality and validation metrics for the PCA and OPLS-DA models, Msm protein expression significantly altered (p-value < 0.01) by a DA-CB treatment, and essentiality of genes expressing proteins that were significantly altered by DA-CB treatment.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Smith I, Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis and molecular determinants of virulence. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2003, 16 (3), 463–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geneva: World Health Organization, Global tuberculosis report 2021; WHO Press, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirzayev F; Viney K; Linh NN; Gonzalez-Angulo L; Gegia M; Jaramillo E; Zignol M; Kasaeva T, World Health Organization recommendations on the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis, 2020 update. Eur Respir J 2021, 57 (6), 2003300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caminero JA; Matteelli A; Lange C, Treatment of TB. Eur. Respir. Monogr 2012, (58), 154–166. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakaya J; Khan M; Ntoumi F; Aklillu E; Fatima R; Mwaba P; Kapata N; Mfinanga S; Hasnain SE; Katoto PDMC; Bulabula ANH; Sam-Agudu NA; Nachega JB; Tiberi S; McHugh TD; Abubakar I; Zumla A, Global Tuberculosis Report 2020 - Reflections on the Global TB burden, treatment and prevention efforts. Int. J. Infect. Dis 2021, 113 (Suppl._1), S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engelbrecht MC; Kigozi NG; Chikobvu P; Botha S; van Rensburg HCJ, Unsuccessful TB treatment outcomes with a focus on HIV co-infected cases: a cross-sectional retrospective record review in a high-burdened province of South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 2017, 17 (1), 470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leibert E; Rom WN, New drugs and regimens for treatment of TB. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther 2010, 8 (7), 801–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ormerod LP, Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB): epidemiology, prevention and treatment. Br. Med. Bull 2005, 73 and 74, 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caminero JA; Sotgiu G; Zumla A; Migliori GB, Best drug treatment for multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis 2010, 10 (9), 621–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almeida Da Silva PE; Palomino JC, Molecular basis and mechanisms of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: classical and new drugs. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2011, 66 (7), 1417–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandhi NR; Nunn P; Dheda K; Schaaf HS; Zignol M; van Soolingen D; Jensen P; Bayona J, Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: a threat to global control of tuberculosis. Lancet 2010, 375 (9728), 1830–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah NS; Wright A; Bai G-H; Barrera L; Boulahbal F; Martin-Casabona N; Drobniewski F; Gilpin C; Havelkova M; Lepe R; Lumb R; Metchock B; Portaels F; Rodrigues MF; Rusch-Gerdes S; Van Deun A; Vincent V; Laserson K; Wells C; Cegielski JP, Worldwide emergence of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Emerging Infect. Dis 2007, 13 (3), 380–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y; Yew WW, Mechanisms of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009, 13 (11), 1320–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koul A; Arnoult E; Lounis N; Guillemont J; Andries K, The challenge of new drug discovery for tuberculosis. Nature (London, U. K.) 2011, 469 (7331), 483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sittiwong W; Zinniel DK; Fenton RJ; Marshall DD; Story CB; Kim B; Lee JY; Powers R; Barletta RG; Dussault PH, Development of cyclobutene- and cyclobutane-functionalized fatty acids with inhibitory activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ChemMedChem 2014, 9 (8), 1838–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zinniel DK; Sittiwong W; Marshall DD; Rathnaiah G; Sakallioglu IT; Powers R; Dussault PH; Barletta RG, Novel Amphiphilic Cyclobutene and Cyclobutane cis-C18 Fatty Acid Derivatives Inhibit Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis Growth. Vet Sci 2019, 6 (2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knall AC; Slugovc C, Inverse electron demand Diels-Alder (iEDDA)-initiated conjugation: a (high) potential click chemistry scheme. Chem Soc Rev 2013, 42 (12), 5131–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim E; Koo H, Biomedical applications of copper-free click chemistry: in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo. Chem Sci 2019, 10 (34), 7835–7851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deb T; Tu J; Franzini RM, Mechanisms and Substituent Effects of Metal-Free Bioorthogonal Reactions. Chem Rev 2021, 121 (12), 6850–6914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang MY; Huang KH; Tu WJ; Chen YT; Pan PY; Hsiao WC; Ke YY; Tsou LK; Zhang MM, Chemoproteomic profiling reveals cellular targets of nitro-fatty acids. Redox Biol 2021, 46, 102126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhat ZS; Rather MA; Maqbool M; Lah HU; Yousuf SK; Ahmad Z, Cell wall: A versatile fountain of drug targets in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 95, 1520–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li M; Patel HV; Cognetta AB 3rd; Smith TC 2nd; Mallick I; Cavalier JF; Previti ML; Canaan S; Aldridge BB; Cravatt BF; Seeliger JC, Identification of cell wall synthesis inhibitors active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis by competitive activity-based protein profiling. Cell Chem Biol 2022. 29(5), 883–896.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu J; Fu H; Dieu M; Halloum I; Kremer L; Xia Y; Pan W; Vincent SP, Identification of inhibitors targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall biosynthesis via dynamic combinatorial chemistry. Chem Commun (Camb) 2017, 53 (77), 10632–10635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keating T; Lethbridge S; Allnutt JC; Hendon-Dunn CL; Thomas SR; Alderwick LJ; Taylor SC; Bacon J, Mycobacterium tuberculosis modifies cell wall carbohydrates during biofilm growth with a concomitant reduction in complement activation. Cell Surf 2021, 7, 100065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banerjee D; Bhattacharyya R, Isoniazid and thioacetazone may exhibit antitubercular activity by binding directly with the active site of mycolic acid cyclopropane synthase: Hypothesis based on computational analysis. Bioinformation 2012, 8 (16), 787–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quemard A; Lacave C; Laneelle G, Isoniazid inhibition of mycolic acid synthesis by cell extracts of sensitive and resistant strains of Mycobacterium aurum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1991, 35 (6), 1035–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quemard A; Laneelle G; Lacave C, Mycolic acid synthesis: a target for ethionamide in mycobacteria? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1992, 36 (6), 1316–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winder FG; Collins PB; Whelan D, Effects of ethionamide and isoxyl on mycolic acid synthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis BCG. J Gen Microbiol 1971, 66 (3), 379–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marrakchi H; Laneelle MA; Daffe M, Mycolic acids: structures, biosynthesis, and beyond. Chem Biol 2014, 21 (1), 67–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morbidoni HR; Vilcheze C; Kremer L; Bittman R; Sacchettini JC; Jacobs WR Jr., Dual inhibition of mycobacterial fatty acid biosynthesis and degradation by 2-alkynoic acids. Chem Biol 2006, 13 (3), 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran JC; Zamdborg L; Ahlf DR; Lee JE; Catherman AD; Durbin KR; Tipton JD; Vellaichamy A; Kellie JF; Li M; Wu C; Sweet SM; Early BP; Siuti N; LeDuc RD; Compton PD; Thomas PM; Kelleher NL, Mapping intact protein isoforms in discovery mode using top-down proteomics. Nature 2011, 480 (7376), 254–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Powers R, NMR metabolomics and drug discovery. Magn. Reson. Chem 2009, 47 (S1), S2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wishart DS, Emerging applications of metabolomics in drug discovery and precision medicine. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2016, 15 (7), 473–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakallioglu IT; Barletta RG; Dussault PH; Powers R, Deciphering the mechanism of action of antitubercular compounds with metabolomics. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2021, 19, 4284–4299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halouska S; Chacon O; Fenton RJ; Zinniel DK; Barletta RG; Powers R, Use of NMR metabolomics to analyze the targets of D-cycloserine in mycobacteria: role of D-alanine racemase. J Proteome Res 2007, 6 (12), 4608–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halouska S; Fenton RJ; Barletta RG; Powers R, Predicting the in vivo mechanism of action for drug leads using NMR metabolomics. ACS Chem Biol 2012, 7 (1), 166–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baptista R; Fazakerley DM; Beckmann M; Baillie L; Mur LAJ, Untargeted metabolomics reveals a new mode of action of pretomanid (PA-824). Scientific reports 2018, 8 (1), 5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dehairs J; Derua R; Rueda-Rincon N; Swinnen JV, Lipidomics in drug development. Drug Discov Today Technol 2015, 13, 33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahluwalia K; Ebright B; Chow K; Dave P; Mead A; Poblete R; Louie SG; Asante I, Lipidomics in Understanding Pathophysiology and Pharmacologic Effects in Inflammatory Diseases: Considerations for Drug Development. Metabolites 2022, 12 (4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biagiotti M; Dominguez S; Yamout N; Zufferey R, Lipidomics and anti-trypanosomatid chemotherapy. Clin Transl Med 2017, 6 (1), 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ebrahim A; Brunk E; Tan J; O’Brien EJ; Kim D; Szubin R; Lerman JA; Lechner A; Sastry A; Bordbar A; Feist AM; Palsson BO, Multi-omic data integration enables discovery of hidden biological regularities. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 13091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Selevsek N; Caiment F; Nudischer R; Gmuender H; Agarkova I; Atkinson FL; Bachmann I; Baier V; Barel G; Bauer C; Boerno S; Bosc N; Clayton O; Cordes H; Deeb S; Gotta S; Guye P; Hersey A; Hunter FMI; Kunz L; Lewalle A; Lienhard M; Merken J; Minguet J; Oliveira B; Pluess C; Sarkans U; Schrooders Y; Schuchhardt J; Smit I; Thiel C; Timmermann B; Verheijen M; Wittenberger T; Wolski W; Zerck A; Heymans S; Kuepfer L; Roth A; Schlapbach R; Niederer S; Herwig R; Kleinjans J, Network integration and modelling of dynamic drug responses at multi-omics levels. Commun Biol 2020, 3 (1), 573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X; Zhang A; Yan G; Sun W; Han Y; Sun H, Metabolomics and proteomics annotate therapeutic properties of geniposide: targeting and regulating multiple perturbed pathways. PLoS One 2013, 8 (8), e71403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang HW; Lv C; Zhang LJ; Guo X; Shen YW; Nagle DG; Zhou YD; Liu SH; Zhang WD; Luan X, Application of omics- and multi-omics-based techniques for natural product target discovery. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 141, 111833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chauhan A; Kumar M; Kumar A; Kanchan K, Comprehensive review on mechanism of action, resistance and evolution of antimycobacterial drugs. Life Sci 2021, 274, 119301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flipo M; Frita R; Bourotte M; Martinez-Martinez MS; Boesche M; Boyle GW; Derimanov G; Drewes G; Gamallo P; Ghidelli-Disse S; Gresham S; Jimenez E; de Mercado J; Perez-Herran E; Porras-De Francisco E; Rullas J; Casado P; Leroux F; Piveteau C; Kiass M; Mathys V; Soetaert K; Megalizzi V; Tanina A; Wintjens R; Antoine R; Brodin P; Delorme V; Moune M; Djaout K; Slupek S; Kemmer C; Gitzinger M; Ballell L; Mendoza-Losana A; Lociuro S; Deprez B; Barros-Aguirre D; Remuinan MJ; Willand N; Baulard AR, The small-molecule SMARt751 reverses Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance to ethionamide in acute and chronic mouse models of tuberculosis. Sci Transl Med 2022, 14 (643), eaaz6280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vale N; Gomes P; Santos HA, Metabolism of the antituberculosis drug ethionamide. Curr Drug Metab 2013, 14 (1), 151–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song Y; Wang G; Li Q; Liu R; Ma L; Li Q; Gao M, The Value of the inhA Mutation Detection in Predicting Ethionamide Resistance Using Melting Curve Technology. Infect Drug Resist 2021, 14, 329–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakallioglu IT; Maroli AS; Leite AL; Powers R, A reversed phase ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-data independent mass spectrometry method for the rapid identification of mycobacterial lipids. J Chromatogr A 2022, 1662, 462739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lloyd GR; Jankevics A; Weber RJM, Struct: an R/bioconductor-based framework for standardised metabolomics data analysis and beyond. Bioinformatics 2020, 36(22–23):5551–5552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pang Z; Chong J; Zhou G; de Lima Morais DA; Chang L; Barrette M; Gauthier C; Jacques PE; Li S; Xia J, MetaboAnalyst 5.0: narrowing the gap between raw spectra and functional insights. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49 (W1), W388–W396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhinderwala F; Wase N; DiRusso C; Powers R, Combining Mass Spectrometry and NMR Improves Metabolite Detection and Annotation. J. Proteome Res 2018, 17 (11), 4017–4022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dubos RJ, Effect of lipides and serum albumin on bacterial growth. J. Exp. Med 1947, 85, 9–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee W; Vander Ven BC; Fahey RJ; Russell DG, Intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis exploits host-derived fatty acids to limit metabolic stress. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288 (10), 6788–6800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Donini S; Ferraris DM; Miggiano R; Massarotti A; Rizzi M, Structural investigations on orotate phosphoribosyltransferase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a key enzyme of the de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis. Sci Rep 2017, 7 (1), 1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu P; Lill H; Bald D, ATP synthase in mycobacteria: special features and implications for a function as drug target. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1837 (7), 1208–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McNeil MB; Ryburn HWK; Harold LK; Tirados JF; Cook GM, Transcriptional Inhibition of the F1F0-Type ATP Synthase Has Bactericidal Consequences on the Viability of Mycobacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020, 64 (8), e00492–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stincone A; Prigione A; Cramer T; Wamelink MM; Campbell K; Cheung E; Olin-Sandoval V; Gruning NM; Kruger A; Tauqeer Alam M; Keller MA; Breitenbach M; Brindle KM; Rabinowitz JD; Ralser M, The return of metabolism: biochemistry and physiology of the pentose phosphate pathway. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2015, 90 (3), 927–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rakovitsky N; Bar Oz M; Goldberg K; Gibbons S; Zimhony O; Barkan D, The Unexpected Essentiality of glnA2 in Mycobacterium smegmatis Is Salvaged by Overexpression of the Global Nitrogen Regulator glnR, but Not by L-, D- or Iso-Glutamine. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.He Z; De Buck J, Cell wall proteome analysis of Mycobacterium smegmatis strain MC2 155. BMC Microbiol 2010, 10, 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Elad N; Baron S; Peleg Y; Albeck S; Grunwald J; Raviv G; Shakked Z; Zimhony O; Diskin R, Structure of Type-I Mycobacterium tuberculosis fatty acid synthase at 3.3 A resolution. Nat Commun 2018, 9 (1), 3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gokulan K; Aggarwal A; Shipman L; Besra GS; Sacchettini JC, Mycobacterium tuberculosis acyl carrier protein synthase adopts two different pH-dependent structural conformations. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2011, 67 (Pt 7), 657–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leonardi R; Jackowski S, Biosynthesis of Pantothenic Acid and Coenzyme A. EcoSal Plus 2007, 2 (2), 10.1128/ecosalplus.3.6.3.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen X; Chen J; Yan B; Zhang W; Guddat LW; Liu X; Rao Z, Structural basis for the broad substrate specificity of two acyl-CoA dehydrogenases FadE5 from mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117 (28), 16324–16332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Minnikin DE; Kremer L; Dover LG; Besra GS, The methyl-branched fortifications of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem Biol 2002, 9 (5), 545–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takayama K; Wang C; Besra GS, Pathway to synthesis and processing of mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005, 18 (1), 81–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bhatt A; Molle V; Besra GS; Jacobs WR Jr.; Kremer L, The Mycobacterium tuberculosis FAS-II condensing enzymes: their role in mycolic acid biosynthesis, acid-fastness, pathogenesis and in future drug development. Mol Microbiol 2007, 64 (6), 1442–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nataraj V; Varela C; Javid A; Singh A; Besra GS; Bhatt A, Mycolic acids: deciphering and targeting the Achilles’ heel of the tubercle bacillus. Mol Microbiol 2015, 98 (1), 7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gavalda S; Leger M; van der Rest B; Stella A; Bardou F; Montrozier H; Chalut C; Burlet-Schiltz O; Marrakchi H; Daffe M; Quemard A, The Pks13/FadD32 crosstalk for the biosynthesis of mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem 2009, 284 (29), 19255–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li W; Gu S; Fleming J; Bi L, Crystal structure of FadD32, an enzyme essential for mycolic acid biosynthesis in mycobacteria. Scientific reports 2015, 5, 15493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bhatt A; Molle V; Besra GS; Jacobs WR Jr.; Kremer L, The Mycobacterium tuberculosis FAS-II condensing enzymes: their role in mycolic acid biosynthesis, acid-fastness, pathogenesis and in future drug development. Mol. Microbiol 2007, 64 (6), 1442–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gande R; Gibson KJC; Brown AK; Krumbach K; Dover LG; Sahm H; Shioyama S; Oikawa T; Besra GS; Eggeling L, Acyl-CoA carboxylases (accD2 and accD3), together with a unique polyketide synthase (Cg-pks), are key to mycolic acid biosynthesis in Corynebacterianeae, such as Corynebacterium glutamicum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem 2004, 279 (43), 44847–44857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sirakova TD; Deb C; Daniel J; Singh HD; Maamar H; Dubey VS; Kolattukudy PE, Wax ester synthesis is required for Mycobacterium tuberculosis to enter in vitro dormancy. PLoS One 2012, 7 (12), e51641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu X; Feng Z; Harris NB; Cirillo JD; Bercovier H; Barletta RG, Identification of a secreted superoxide dismutase in Mycobacterium avium ssp. paratuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2001, 202 (2), 233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kuhn ML; Alexander E; Minasov G; Page HJ; Warwrzak Z; Shuvalova L; Flores KJ; Wilson DJ; Shi C; Aldrich CC; Anderson WF, Structure of the Essential Mtb FadD32 Enzyme: A Promising Drug Target for Treating Tuberculosis. ACS Infect Dis 2016, 2 (8), 579–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.DeJesus MA; Gerrick ER; Xu W; Park SW; Long JE; Boutte CC; Rubin EJ; Schnappinger D; Ehrt S; Fortune SM; Sassetti CM; Ioerger TR, Comprehensive Essentiality Analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Genome via Saturating Transposon Mutagenesis. mBio 2017, 8 (1), e02133–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dragset MS; Ioerger TR; Zhang YJ; Maerk M; Ginbot Z; Sacchettini JC; Flo TH; Rubin EJ; Steigedal M, Genome-wide Phenotypic Profiling Identifies and Categorizes Genes Required for Mycobacterial Low Iron Fitness. Scientific reports 2019, 9 (1), 11394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vadwai V; Ajbani K; Jose M; Vineeth VP; Nikam C; Deshmukh M; Shetty A; Soman R; Rodrigues C, Can inhA mutation predict ethionamide resistance? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2013, 17 (1), 129–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu K; Enns B; Evans B; Wang N; Shang X; Sittiwong W; Dussault PH; Guo J, A genetically encoded cyclobutene probe for labelling of live cells. Chem Commun (Camb) 2017, 53 (76), 10604–10607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.