Abstract

Background:

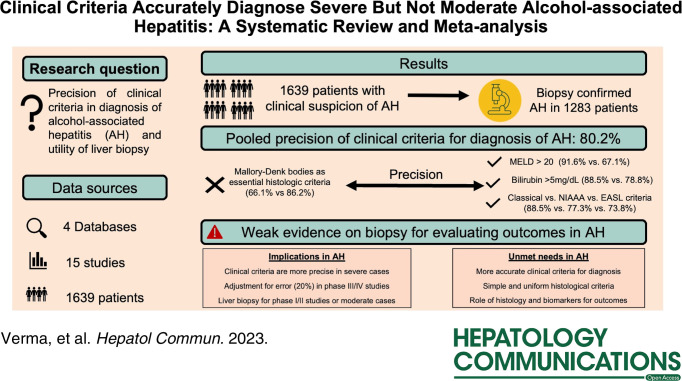

The precision of clinical criteria and the utility of liver biopsy for diagnosis or prognosis remain unclear in patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH). We systematically reviewed the literature to answer these questions.

Methods:

Four databases were searched for studies describing the precision of clinical criteria (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, European Association for Study of Liver, or classical) and the role of histology in AH. The precision(positive predictive value) of criteria was pooled through random-effects meta-analysis, and its variation was investigated through subgroups and meta-regression of study-level factors with their percent contribution to variation (R 2). The risk of bias among studies was evaluated through the QUADAS2 tool (PROSPERO-ID-CRD4203457250).

Results:

Of 4320 studies, 18 in the systematic review and 15 (10/5: low/high risk of bias, N=1639) were included in the meta-analysis. The pooled precision of clinical criteria was 80.2% (95% CI: 69.7–89.7, I 2:93%, p < 0.01), higher in studies with severe AH (mean-Model for End-Stage Liver Disease > 20) versus moderate AH (mean-Model for End-Stage Liver Disease < 20): 92% versus 67.1%, p < 0.01, and in studies with serum bilirubin cutoff 5 versus 3 mg/dL (88.5% vs.78.8%, p = 0.01). The factors contributing to variation in precision were Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (R 2:72.7%), upper gastrointestinal bleed (R 2:56.3%), aspartate aminotransferase:aspartate aminotransferase ratio (R 2:100%), clinical criteria (R 2:40.9%), bilirubin (R 2:22.5%), and Mallory body on histology (R 2:19.1%).

The net inter-pathologist agreement for histologic findings of AH was variable (0.33–0.97), best among 2 studies describing AH through simple and uniform criteria, including steatosis, ballooning, and neutrophilic inflammation. Few studies reported the utility of histology in estimating steroid responsiveness (N = 1) and patient prognosis (N = 4); however, very broad septa, pericellular fibrosis, and cholestasis were associated with mortality. Bilirubinostasis was associated with infection in 1 study.

Conclusions:

Clinical criteria are reasonably precise for diagnosing severe AH, while there is an unmet need for better criteria for diagnosing moderate AH. Histologic diagnosis of AH should be simple and uniform.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH) is the most severe form of alcohol-associated liver disease, which is associated with high short-term mortality.1,2 Until few years ago, the criteria for the clinical diagnosis of AH were variable. Often, it was defined as a recent onset of jaundice with/without other features of decompensation in a patient with ongoing alcohol abuse and/or features of steatohepatitis on liver biopsy.3,4 Further, due to the invasiveness and limited availability of liver biopsy in routine clinical practice, the diagnosis was often based on clinical and laboratory parameters alone, with liver biopsy reserved when clinical diagnosis was uncertain.3,4

Since the criteria for diagnosis of AH were heterogeneous, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) in 2016 developed clinical criteria for AH based on expert consensus.5 These criteria are the development of jaundice within the prior 8 weeks with serum bilirubin > 3 mg/dL, ongoing alcohol consumption (> 40 grams/day for females and > 60 grams/day for males) for ≥ 6 months within at least prior 60 days from onset of jaundice, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to alanine aminotransferase ratio > 1.5 with both values < 400 IU/L and AST > 50 IU/L.5. Based on these criteria,5 a patient can be stratified to have (a) definite AH when all clinical criteria are met, and the liver biopsy is consistent with AH, (b) probable AH when all clinical criteria are met without available liver histology, and (c) possible AH when one or more clinical criteria are not met due to presence of confounding factors. Based on these criteria, patients with definite and probable AH were considered candidates for steroid therapy and entry into clinical trials.5 Despite widespread use, very few studies have investigated the diagnostic role of clinical criteria for AH. Variability in diagnostic accuracy of clinical criteria and interobserver variability in the reporting of liver biopsy findings add to the heterogeneity in the clinical trial enrollment and in the clinical diagnosis of AH in practice.

Therefore, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to ascertain the precision of clinical criteria for diagnosing AH on liver histology. We also explored the utility of liver biopsy in risk stratification and predicting infection and response to steroids in patients with AH.

METHODS

Study design

We performed the study according to the PRISMA guidelines,6 and the protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD4203457250).

Outcomes of study

The primary objective was to evaluate the precision or positive predictive value (outcome) of clinical criteria of AH (index test) with liver biopsy (as reference standard) in patients (> 18 y) who consume alcohol in significant amounts per day (population). The precision in each study was calculated as the proportion of patients with clinical criteria diagnosed to have AH on histology. The other objectives of the study were to (a) evaluate the utility of liver biopsy in estimating prognosis, infection, and response to steroids and (b) examine inter-pathologist reliability for diagnosing AH.

Literature search

Three independent investigators (Nipun Verma, Rohit Mehtani, Jacob Martin Haiar) selected studies for the analysis from the list of articles retrieved through an electronic search conducted by a librarian (Pranita Pradhan) in PubMed, EBSCO, Scopus, and Embase from their inception until November 30, 2023. The search strategy used Boolean combinations of the clinical and MeSH terms, including alcohol consumers, liver biopsy, diagnosis, and prognosis, as illustrated in the Supplemental data, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A833.

Eligibility criteria

Observational or interventional studies reporting patients (>18 years) with a history of significant alcohol consumption, with clinical suspicion of AH, and availability of liver biopsy results were included in the study, and the availability of liver biopsy results. Duplicate articles, studies with insufficient data (conference proceedings, meeting abstracts, and case reports), and non-English language were excluded. Grey literature search and the references in original articles and published reviews were manually screened for additional studies. Studies reporting histological confirmation of AH in clinically suspected patients were included in the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

Three investigators (Nipun Verma, Rohit Mehtani, and Jacob Martin Haiar) independently extracted the data utilizing a pre-piloted data extraction sheet. The disagreements in study selection and data extraction were resolved through discussion with the arbitrator (Ashwani K. Singal). Clinical suspicion of AH was mainly based on rapid deterioration in liver functions, including jaundice and elevated aminotransferases in a patient with heavy alcohol use (Tables 1–3). Briefly, these clinical criteria were itemized into the European Association for Study of Liver 2012 criteria,7 Classical criteria,8 and the NIAAA criteria5 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Clinical criteria for diagnosis of alcohol-associated hepatitis

| References | Clinical presentation | Serum bilirubin (mg/dL) | Other laboratory data | Alcohol use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIAAA criteria5 | Jaundice | > 3 | AST/ALT > 1.5 and < 400 IU/L | > 40 g/d in women and > 60 g/d in men within previous at least 8 wk |

| EASL criteria7 | Recent jaundice±ascites | Not defined | Not defined | Ongoing |

| Classical criteria8 | Ascites | > 5 | AST/ALT > 2 and > 300 IU/L, neutrophilia, elevated INR | Heavy |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; EASL, European Association for Study of Liver; INR, international normalized ratio; NIAAA, National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse.

TABLE 3.

Pooled precision of clinical criteria for diagnosis of alcohol-associated hepatitis on histology in various study-level subgroups

| Attributes | Subgroup (No. studies) | Cases with clinical diagnosis | Precision | 95% CI | Heterogeneity (I 2 ) | Sub-group difference (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study characteristics | Origin of study | 0.98 | ||||

| West (11 studies)9,12,13,14,15,16,18,22,23,24,25 | 1314 | 80.2 | 70.1–87.5 | 91 | ||

| East (4 studies)17,19,20,21 | 325 | 79.9 | 43.2–95.4 | 96 | ||

| Design | 0.65 | |||||

| Prospective (9 studies)9,12,13,15,18,19,21,22,25 | 955 | 82.5 | 66.5–91.8 | 91 | ||

| Retrospective (6 studies)14,16,17,20,23,24 | 684 | 78.0 | 60.9–89.0 | 95 | ||

| Random sampling | 0.68 | |||||

| Yes | 882 | 78.3 | 62.9–88.6 | 91 | ||

| No | 757 | 82.2 | 65.4–91.9 | 94 | ||

| Population | MDF above 32 | 0.14 | ||||

| Yes (8 studies)13,15,16,17,22,23,24 | 871 | 85.1 | 78.1–90.1 | 76 | ||

| No or unclear (7 studies)9,12,18,19,20,21,25 | 768 | 72.3 | 50.6–86.9 | 93 | ||

| MELD above 20a | <0.01 | |||||

| Yes (3 studies)15,22,23 | 317 | 91.6 | 87.3–94.6 | 56 | ||

| No (4 studies)12,16,18,25 | 490 | 67.1 | 46.6–82.7 | 93 | ||

| Leucocytosis above 11000/ul | 0.97 | |||||

| Yes (5 studies)12,13,16,17,19 | 401 | 78.9 | 54.3–92.2 | 92 | ||

| No (6 studies)9,14,18,21,23,25 | 746 | 78.5 | 67.5–86.5 | 88 | ||

| Index test | Clinical criteriab | 0.04 | ||||

| EASL (6 studies)9,12,13,14,15,18 | 688 | 73.8 | 59.2–84.5 | 91 | ||

| NIAAA (4 studies)17,20,22,25 | 337 | 77.3 | 29.3–96.6 | 90 | ||

| Classical criteria (4 studies)16,19,23,24 | 493 | 88.5 | 85.2–91.1 | 47 | ||

| Unclear (1 study)21 | 121 | 88.4 | 81.3–93.5 | |||

| Bilirubin levels | 0.01 | |||||

| > 3 mg/dl or >50 μmol/L (6 studies)14,15,17,20,22,25 | 593 | 78.8 | 52.6–92.6 | 94 | ||

| > 5 mg/dl or 80 μmol/L (4 studies)16,19,23,24 | 493 | 88.5 | 85.2–91.1 | 47 | ||

| Unclear (5 studies)9,12,13,18,21 | 553 | 71.6 | 55.1–83.8 | 91 | ||

| Reference test | Biopsy criteria | |||||

| Ballooning and inflammation (8 studies)9,12,13,16,18,19,21,23 | 885 | 81.3 | 67.6–90.1 | 92 | 0.87 | |

| Steatosis, ballooning, and inflammation (7 studies)14,15,17,20,22,24,25 | 754 | 79.6 | 59.3–91.3 | 94 | ||

| Mallory-Denk bodies | 0.02 | |||||

| Essential (5 studies)9,14,17,18,20 | 570 | 66.0 | 50.2–78.9 | 92 | ||

| No or unclear (10 studies)12,13,15,16,19,21,22,23,24,25 | 1069 | 86.1 | 74.8–92.8 | 91 | ||

| Pericellular fibrosis | 0.45 | |||||

| Essential (5 studies)9,18,20,21,23 | 615 | 75.1 | 52.9–89.0 | 95 | ||

| No or unclear (10 studies)12,13,14,15,16,17,19,22,24,25 | 1024 | 82.9 | 70.0–90.9 | 90 | ||

| Reporting by 2 or more pathologists | 0.50 | |||||

| Yes (7 studies)12,18,19,22,23,24,25 | 746 | 84.9 | 62.7–95.0 | 93 | ||

| No or unclear (8 studies)9,13,14,15,16,17,20,21 | 893 | 78.0 | 65.5–86.8 | 93 | ||

| Reporting by the liver pathologist | 0.34 | |||||

| Yes (8 studies)9,13,16,18,19,21,22,25 | 936 | 84.2 | 70.9–92.2 | 89 | ||

| No or unclear (7 studies)12,14,15,17,20,23,24 | 703 | 75.3 | 56.5–87.7 | 95 | ||

| Quality of study | Risk of bias | 0.26 | ||||

| Low (10 studies)9,12,16,18,19,21,22,23,24,25 | 1194 | 83.9 | 71.1–91.7 | 92 | ||

| High (5 studies)13,14,15,17,20 | 445 | 72.6 | 51.9–86.7 | 94 |

Data on MELD score of patients meeting clinical criteria for AH available in 7 studies,

Clinical criteria: EASL 2012:7 “Recent onset of jaundice and/or ascites in a patient with ongoing alcohol misuse,” NIAAA 2016:5 “Jaundice (>3 mg/dl), within last 8weeks, with AST/ALT > 1.5, both < 400 IU/L, in patients with ongoing alcohol use > 40 g/d(females), > 60 g/day(males), excluding other acute and chronic liver diseases”, Classical criteria8 (Lucey, NEJM 2009): “Abnormal LFT with bilirubin > 5 mg/dL, AST/ALT > 2; both < 300IU/L, elevated INR, neutrophilia in patients with ascites and heavy alcohol abuse”.

Abbreviations: AH, alcohol-associated hepatitis; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; EASL, European Association for Study of Liver; INR, international normalized ratio; LFT, liver function test; MDF, Maddrey’s discriminant function; MELD, Model for End-stage Liver Disease; NIAAA, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

For each study, the following variables were extracted: (a) study details: author’s name, country, publication year, design-prospective or retrospective; (b) demographics: age and gender; (c) clinical data: cases with clinical suspicion of AH, criteria of suspicion, excluded patients, ascites, HE, and upper gastrointestinal bleed; (d) histology data: liver biopsy findings, criteria for histological diagnosis, cases with histologically confirmed AH, route, timing and interpreter(s) of liver biopsy; d) laboratory data: leukocyte count, Maddrey discriminant function, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), Child Turcotte Pugh, serum bilirubin, international normalized ratio, serum creatinine, serum AST and alanine aminotransferase, and serum albumin. Interobserver reliability (kappa coefficient) between pathologists for diagnosing AH, neutrophilic infiltration, bilirubinostasis, fibrosis stage, and megamitochondria was noted.

Alcohol-associated hepatitis histologic score (AHHS)9 (Supplemental Table S1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A833) and its utility for mortality risk assessment, infection prediction, and steroid response were recorded. As one study used the Consortium for the Study of Alcohol-related LiVer Disease in Europe (SALVE) criteria for grading (Supplemental Table S2, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A833) and staging (Supplemental Table S3, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A833), these criteria were noted with their implications for the diagnosis and prognosis of AH. Any discrepancy during data collection was resolved through discussion with an arbitrator (Ashwani K. Singal). Finally, 2 investigators (Rohit Mehtani and Nipun Verma) independently assessed the study quality using the QUADAS2 tool10 and resolution of conflicts with an arbitrator (Ashwani K. Singal). This tool evaluated the risk of bias (ROB) in 4 domains, viz., patient selection, index test, reference standard, and patient flow. To be eligible for a low ROB, a study had to score low ROB in 3 or more domains.

Statistical analysis

The mean (±SD) or number (%) were described as appropriate. A generalized linear mixed model11 was conducted to pool the estimates of diagnostic precision for each study, where estimates were logit-transformed, pooled, and retransformed to proportions during random effect meta-analysis. Restricted maximum likelihood method with Biggerstaff and Jackson method for confidence intervals and Hartung-Knapp adjustment were used for estimating between study variances. The heterogeneity in estimates was assessed by Tau2, I 2, and chi-square test (Q-statistic). The cutoffs for small, medium, and large heterogeneity (I 2) were > 25%, 50%, and 75%, respectively. A list of study-level attributes specific to design, population, index test, reference standard, and quality of study was used to investigate heterogeneity in estimates within subgroups and on meta-regression using a mixed-effects model. Outlier study assessments were performed to identify studies contributing to heterogeneity. Leave-one study-out plots were created for sensitivity analysis. The funnel plot and Egger’s regression were done to assess the asymmetry in estimates. All analysis was performed using the R studio v. 1.4.1103, and a p-value of < 0.1 was considered significant for heterogeneity and < 0.05 for subgroups and meta-regression.

RESULTS

Of the 7963 references identified, 4320 were screened after excluding duplicate records, and 49 full texts were assessed for eligibility after excluding articles based on title and abstracts. Thirty-one articles were excluded due to various reasons (Figure 1). Finally, 18 studies9,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 were included in the systematic review. Three studies26,27,28 did not provide data on the precision of clinical criteria for AH, leaving 15 studies for the quantitative meta-analysis.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

Study characteristics

Of 18 studies, 9 were retrospective,14,16,17,20,23,24,26,27,28 and 9 were prospective studies.9,12,13,15,18,19,21,22,25 Of 15 studies included in the meta-analysis, 4 studies used NIAAA criteria,17,20,22,25 4 used Classical criteria,16,19,23,24 6 used European Association for Study of Liver 2012 criteria,9,12,13,14,15,18 while 1 study did not report as to which criteria were used.21 Eight studies13,14,15,16,17,22,23,24 included patients with severe AH as defined by a discriminant function (DF ≥ 32). Criteria used to define AH on histology were also heterogeneous. Steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, and inflammation (predominantly neutrophilic) were used to diagnose AH in 7 studies,14,15,17,20,22,24,25 while 8 studies9,12,13,16,18,19,21,23 did not include steatosis as an essential criterion for diagnosis of AH. Timing of liver biopsy after admission was within 48 hours in 3 studies,9,18,24 within 3 days in 1 study,15 within 7 days in 4 studies,12,17,21,27 and not defined in 9 studies.13,14,16,19,20,22,23,25,26 A single pathologist evaluated liver biopsy in 4 studies,9,15,16,17 2 pathologists in 6 studies,12,19,22,23,25,27 more than 2 pathologists in 2 studies18,26 while this was not defined in 5 studies.13,14,20,21,24 The study characteristics are summarized in Table 2 and Supplemental Table S4, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A833.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| References, country | Design | Criteria AHa | Inclusion criteria for biopsy | Excluded patients | Biopsy criteria for AH | Cirrhosis on biopsy (%) | Route, timing, and interpreters of biopsy | Overall ROB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mookerjee12 UK | Prospective | EASL 2012 | Acute decompensation of ALD (ascites, edema, and jaundice), cirrhosis on clinical and radiology, alcohol use > 80 g/d (men), > 60 g/d (women) | < 18 or > 75 y, other etiology of liver disease, severe organ dysfunction, malignancy, and infection | Hepatocellular ballooning, ASH grading | 75.0 | Within 7 d of admission, primarily by transjugular route, by 2 pathologists, blinded | Low |

| Hardy13 UK | Prospective | EASL 2012 | Recent jaundice with excessive alcohol intake, DF ≥ 32 | Infection, SBP, UGI Bleed, Cardio-respiratory disease | Not clear | 81.0 | Route, timing not clear, 1 expert pathologist | High |

| Altamirano9 UK and USA | Prospective | EASL 2012 | Alcohol > 60 g/day, moderately elevated bilirubin, AST > ALT, elevated GGT | HCC, any other liver disease | Hepatocellular ballooning, Mallory bodies, inflammatory infiltrate (predominantly polymorphonuclear), and pericellular fibrosis | 82.0 | Within 48 hours of admission by transjugular route, 1 liver pathologist was blinded | Low |

| Rudler15 France | Prospective | EASL 2012 | Jaundice, Bilirubin> 2.9 mg/dl, excessive alcohol consumer, DF ≥ 32 | Other etiology of acute or chronic liver disease | Steatosis, ballooning, and neutrophil infiltration | 100.0 | Within 3 days of admission, the route was not clear, and a single pathologist blinded | High |

| Rudler14 France | Retrospective | EASL 2012 | Jaundice, bilirubin > 2.9 mg/dl, < 3 mo, DF ≥32, active drinking, long term alcoholism | Advanced HCC, other etiology of cirrhosis, HIV, and severe comorbidities | Neutrophil infiltrate and 1: ballooning or Mallory bodies | 100.0 | Timing not clear, transjugular route, rest not clear | High |

| Roth16 USA | Retrospective | Classical criteria | Bilirubin > 5 mg/dl, chronic alcoholism, jaundice < 3 mo, and DF ≥ 32 | Insufficient biopsy, duration > 14 d after admission, > 7 d after steroids, prior biopsy, HIV, nonalcoholic, nonhepatic causes of liver disease | Ballooning and lobular inflammation±Mallory bodies | 61.0 | Median 6 d (range: 1–14) after admission by transjugular (85%) or percutaneous (15%) routes. Liver pathologist (1), blinded | Low |

| Shetty17 India | Retrospective | NIAAA | Jaundice, 18–65 y age, alcohol intake > 50 g/day, > 6 mo, < 2 mo abstinence, DF > 32 | Other causes of liver disease viz. Infection, viral hepatitis, malignancy, AST/ALT > 400 U/l | Steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, Mallory hyaline bodies, and neutrophilic inflammation | 33.0 | Within 7 d of admission by transjugular route, 1 pathologist | High |

| Bissonnette18 France, Spain | Prospective | EASL 2012 | Alcohol consumer > 60 g/day, moderately elevated AST, ALT, GGT, AST > ALT, elevated bilirubin | HCC, active extrahepatic malignancy, prior liver transplant, prior TIPS | Hepatocellular ballooning and Mallory-Denk bodies, inflammatory infiltrate (predominantly polymorphonuclear cells), and pericellular fibrosis | NA | Within 48 h of admission, transjugular route, 3 liver histopathologists | Low |

| Shasthry19 India | Prospective | Classical criteria | Bil > 5 mg/dl, heavy alcohol consumer, within 60 days before jaundice, AST/ALT elevation, < 500 IU/mL, AST: ALT ≥ 2, INR1.5, neutrophilia | Infections, sepsis, UGIB, renal insufficiency, tuberculosis, acute viral hepatitis, DILI, nonconsenting patients | Ballooning and lobular inflammation | 100.0 | Time not clear, transjugular, by 2 liver pathologists | Low |

| Choudhary20 India | Retrospective | NIAAA | Bil > 3 mg/dl, probable AH as per NIAAA posted for transplant | Other causes of liver disease. | Steatosis, one or more ballooning degeneration, Mallory hyaline bodies, neutrophilic infiltration, and pericellular fibrosis | 95.0 | Not clear | High |

| Lee21 Korea | Prospective | Unclear | ≥ 18 y of age, alcohol > 60 g/day for men and > 40 g/day for women, elevated GGT, and AST, ALT, AST: ALT > 1 | Other etiologies of chronic liver disease | Mallory bodies, hepatocellular ballooning), inflammatory infiltrate polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and pericellular fibrosis | 76.0 | Within 7 d of admission, percutaneous or transjugular route | Low |

| Dubois22 Switzerland, Belgium | Prospective | NIAAA | Bil > 2.9 mg/dl, alcohol consumer > 60 g/day (men), > 40 g/day (women), < 90 d jaundice, DF > 32, < 60 d of abstinence, and histologic AH | Viral hepatitis, AIH, hemochromatosis, Co-infection with hepatitis A, B, C, or E | Steatosis, ballooning, and neutrophilic infiltration | 93.0 | Time, route not clear, by 2 liver pathologists | Low |

| Atkinson23 UK | Retrospective | Classical criteria | Bilirubin > 4.7 mg/dL, alcohol use (> 80 g/d for males, > 60 g/d for females), presentation in < 4 wk, longstanding alcohol misuse, clinical, laboratory, DF ≥ 32 | No other identified causes for their liver disease, abstinence > 2 mo, AST > 500, ALT > 300 IU/L | Hepatocellular ballooning, Mallory bodies, inflammatory infiltrate (predominantly polymorphonuclear cells), and pericellular fibrosis | Timing not clear, transjugular route, by 2 blinded histopathologists | Low | |

| Forrest24 UK | Retrospective | Classical criteria | Bil > 4.7 mg/dl, alcohol > 80 g/day(men), > 60 g/day (women), < 4 wk, DF ≥ 32 | Abstinence > 2 mo, jaundice > 3 mo, other liver diseases, malignancies, steroid or pentoxifylline use in last 6 weeks, AST > 500, ALT > 300, creatinine > 500mmol/L, RRT, inotropes, GI bleed, untreated sepsis, cerebral hemorrhage, extensive retinal hemorrhage, acute myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, pregnancy, and lactating women | Hepatocyte steatosis, ballooning, and inflammatory infiltration | 71.0 | Within 48 hours of admission, transjugular route, 2 blinded histopathologists. | Low |

| Avitabile25 Spain, USA | Prospective | NIAAA | Bil > 3 mg/dl, probable AH as per NIAAA | < 18 or > 85 y, previous liver or kidney transplantation, HCC, other liver diseases, sepsis, insufficient liver biopsy, and lack of consent | Steatosis (any degree), hepatocellular ballooning, and lobular inflammation | 69.0 | The timing and route are not clear. Two blinded liver pathologists | Low |

| Horvath26 USA | Retrospective | NA | Biopsy-proven AH | Not clear | Not clear | NA | Time, route not clear, by 5 blinded pathologists | NA |

| Andrade27 Portugal | Retrospective | Unclear | > 18 y, alcohol consumer > 80 g/day (men), > 60 g/day (women), AST, ALT: 5–10× ULN, AST > ALT, elevated GGT, bilirubin | Other causes of liver disease | Not clear | NA | Within 7 days of admission, transjugular, 2 liver pathologists | NA |

| Lackner28 Multicenter Europe | Retrospective | NA | Biopsy-proven ALD, compensated, decompensated, and histologic ASH | NA | SALVE grading: Ballooning and neutrophil scores >= 1 each with activity score >= 2 | NA | Time and route are not clear, at least 3 pathologists | NA |

| Pooled: 85.1% (71.6–92.9), I 2 85%, p < 0.01 |

Clinical criteria: EASL 20127: “Recent onset of jaundice and/or ascites in a patient with ongoing alcohol misuse”, NIAAA 20165: “Jaundice (> 3 mg/dl), within last 8 weeks, with AST/ALT >1.5, both < 400IU/L, in patients with ongoing alcohol use > 40 g/d(females), > 60 g/day(males), excluding other acute and chronic liver diseases”, Classical criteria8 (Lucey, NEJM 2009): “Abnormal LFT with bilirubin > 5 mg/dL, AST/ALT > 2; both < 300IU/L, elevated INR, neutrophilia in patients with ascites and heavy alcohol abuse.”

Abbreviations: AH, alcohol-associated hepatitis; AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALD, alcohol-associated liver disease; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ASH, alcohol-associated steatohepatitis; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Bil, bilirubin; DF, discriminant function; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; LFT, liver function test; NA, not available; NIAAA, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; ROB, risk of bias; SBP, pontaneous bacterial peritonitis; RRT, renal replacement therapy; UGI, upper gastrointestinal; ULN, upper limit normal.

Outcomes

Precision of clinical criteria for diagnosis of AH

Of 1639 patients from 15 studies,9,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 with clinical suspicion of AH, biopsy confirmation was documented in 1283 patients. The pooled precision was 80.2% (95% CI: 69.7–89.7, Figure 2). However, there was high heterogeneity between studies (p < 0.01; I 2 = 93%).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot showing pooled precision of clinical criteria for diagnosis of alcohol-associated hepatitis.

Heterogeneity evaluation

The pooled precision of clinical criteria was higher among studies with mean-MELD scores > 20 than those with lower MELD scores (91.6% vs. 67.1%, p < 0.01) (Table 3). Precision was also numerically higher in studies including only patients with Maddrey discriminant function scores > 32 (85.1% vs. 72.3%), although this was not significant, p = 0.14. Based on the clinical criteria, the precision was 88.5% for Classical criteria (88.5%), 77.3% for NIAAA criteria, and 73.8% for European Association for Study of Liver criteria, p = 0.04. Serum bilirubin > 5 mg/dL (80 μmol/L) versus 3 mg/dL (50 μmol/L) was also associated with improved precision of clinical diagnosis of AH (88.5% vs. 78.8%, p = 0.01). Further, including Mallory bodies in the histologic criteria of AH was associated with a lower precision of clinical diagnosis of AH (66.1% vs. 86.1%, p = 0.02). There were no differences in precision estimates based on prospective or retrospective study design, random or nonrandom patient recruitment, region, leukocytosis, biopsy criteria, reporting by 1 or 2 pathologists, or assessment by an expert liver pathologist (Table 3).

Investigating further the variation in precision of clinical criteria, we delved into relevant study-level factors (identified a-priori and through subgroup analysis) to assess their contribution to heterogeneity, both in terms of quantity (R 2) and direction (beta coefficients) through meta-regression. Our findings revealed that MELD (contribution: 72.7%), upper gastrointestinal bleed (contribution: 56.3%), AST to ALT ratio (contribution: 100%), clinical criteria (contribution: 40.9%), bilirubin (contribution: 22.5%), and Mallory bodies on histology (contribution: 19.1%) emerged as significant contributors to the variations in pooled estimates(Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Meta-regression to investigate heterogeneity in the pooled estimate of precision of clinical criteria for diagnosing alcohol-associated hepatitis

| Variable in study | R 2 (% contribution to heterogeneity) | Beta coefficient | 95% CI | p a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MELD (mean) | 72.7 | 0.261 | 0.104 to 0.418 | 0.001 |

| MDF>32 | 16.1 | 0.901 | −0.145 to 1.947 | 0.091 |

| UGI bleed (proportion) | 56.3 | 0.056 | 0.010 to 0.101 | 0.018 |

| AST: ALT ratio (mean)b | 100.0 | 4.940 | 3.374 to 6.506 | <0.001 |

| Clinical criteria | 40.9 | 0.034 | ||

| EASL7 | Ref. | |||

| NIAAA5 | −0.334 | −1.509 to 0.842 | 0.578 | |

| Classical criteria8 | 1.263 | 0.123 to 2.402 | 0.029 | |

| Baseline bilirubin | 22.5 | |||

| > 3 mg/dl or > 50 μmol/l | Ref. | |||

| > 5 mg/dl or 80 μmol/l | 1.159 | −0.126 to 2.443 | 0.077 | |

| Unclear | −0.227 | −1.400 to 0.946 | 0.704 | |

| Mallory bodies as an essential criterion | 19.1 | −1.121 | −2.191 to -0.050 | 0.040 |

Notes: R 2 quantifies the extent to which study-level factors contribute to heterogeneity in pooled estimates. Beta coefficient conveys both the strength and direction of the impact on the pooled estimates of the precision of clinical criteria for each unit change for a numerical variable or factor comparison to a reference category for categorical factors. For example, an increase of 1 U in the MELD score is associated with an increase in precision estimates by ~0.261 U, while the presence of classical criteria in comparison to EASL criteria would increase the precision estimates by 1.263 U. The presence of Mallory bodies is associated with a decrease in precision estimates by ~1.121 U.

Other variables that were nonsignificant (p > 0.05) were CTP, MDF, age, WBC, bilirubin, INR, creatinine, albumin, ascites, HE, and male gender.

Mixed effect model with restricted maximum likelihood estimator. #10 studies with available data.

Data from studies15,18,19.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CTP, Child Turcotte Pugh score; EASL, European Association for Study of Liver; INR, international normalized ratio; MDF, Maddrey’s discriminant function; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; NIAAA, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; UGI, upper gastrointestinal; WBC, white blood cell count.

Outlier analysis did not reveal any influential study (Supplemental Figure 1, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A833). Leave-one analysis showed the precision of clinical criteria after removing each study from the meta-analysis (Supplemental Figure 2, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A833).

Role of histology in risk stratification

Seven studies evaluated the role of liver biopsy in predicting patient prognosis (Table 5).9,15,16,21,22,27,28 Of these, 3 studies9,21,27,28 reported higher mortality in patients with high AHHS scores. One study reported cholestasis, cirrhosis with very broad septa, and severe pericellular fibrosis as predictors of poor survival.28 Three studies9,22,27 analyzed the response to steroids based on the AHHS score. One study27 demonstrated a better response in patients with low AHHS scores, while the other 2 studies9,22 did not show any difference. Modified AHHS predicted higher mortality in patients with MELD < 21 and age, serum bilirubin, INR, and serum creatinine - (ABIC) score class A and B.9,21 Bilirubinostasis predicted risk infection risk in 1 study9 (OR 1.57; 95% CI: 1.00–2.47; p = 0.04).

TABLE 5.

Role of histology in risk stratification of patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis

| References | Mortality risk stratification | Added value to clinical scores | Infection prediction | Response to steroids |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altamirano9 | Ninety-day survival: mild (17/17, 100%) vs. moderate AHHS (20/24, 83%) (p = 0.08) and moderate vs severe AHHS (44/68, 65%) (p = 0.007). | Patients with ABIC class B stratified by modified AHHSb into 2 risk groups for survival at 90 days: low risk (36/38, 95%) vs. high risk (94/135, 70%) (p = 0.003). In patients with MELD < 21, also stratified into 2 risk groups: low risk (52/55, 94%) vs. high risk (84/116, 72%) (p = 0.001) | Bilirubinostasis (OR 1.57, 1.00–2.47, p = 0.04). | No difference in AHHS between lille responders and nonresponders (5.2 [2.0) vs. 6.0 [2.0], p=0.20) |

| Rudler14 | Two-year survival is not different between moderate (42%) and severe AHHS (38%) (p = 0.90). | NA | NA | NA |

| Andrade27 | AHHS is associated with 90-day mortality (OR 2.78, 1.37–5.34, p < 0.001). AHHS > 7 100% sensitivity, 100% specificity, AUC 1.00, p < 0.001 | NA | NA | Steroid responders vs. nonresponders: AHHS was lower (5.4 [0.9] vs. 8.1[1.1], p=0.003). AHHS < 6: steroid responders with AUC 0.900, 0.742–1.000; sensitivity 87.5%, specificity 90%, PPV 98%, NPV 90%, (p = 0.004) |

| Roth16 | Not associated with 60-day (HR: 1.01, 0.82–1.26, p=0.86) or 180-day mortality (HR: 1.03, 0.84–1.25, p = 0.79) | NA | NA | NA |

| Dubois22 | Not associated with survival. Survival in the mild, moderate, and severe AHHS groups were 90%, 72%, and 69% at 28 days (p=0.6), 80%, 52%, and 63% at 3 mo (p=0.3), and 70%, 41% and 58% at 6 mo (p=0.3), respectively | NA | NA | Did not predict steroid response. The response was 50%, 73%, and 58% in the mild, moderate, and severe AHHS groups, respectively (p = 0.3) |

| Lee21 | Traditional AHHS scorea is not associated with survival (moderate vs mild: HR: 1.57, 0.67–3.66, p = 0.300), (severe vs. mild: HR: 2.37, 1.00–5.59, p = 0.050), and (severe vs. moderate: HR: 1.51, 0.83–2.73, p = 0.176). Modified scoreb: High vs. low risk (HR: 3.16, 1.65–6.07, p = 0.001). | Modified AHHSb did not improve the mortality prediction in patients with a MELD score ≥ 21 (p = 0.262). However, it discriminated risk of death in patients with ABIC class A and B (ABIC score < 9) (p = 0.001) and patients with MELD score < 21 (p = 0.006) | NA | NA |

| Lackner28 | Canalicular and ductular cholestasis was associated with poor 90-day survival (p = 0.029). Cirrhosis with very broad septa (SALVE stage 4C) were associated with poor 10-year (p < 0.001) and 90-day survival (p = 0.070) Severe pericellular fibrosis associated with poor survival, liver injury, inflammation, fibro-obliterative venous lesions, and cholestasis |

Cirrhosis with very broad septa (SALVE stage 4C) was independent predictor of 90-day mortality (adjusted HR: 2.16, 1.11–4.18, p = 0.023) in addition to MELD and HE | NA | NA |

Tradition score refers to AHHS mild (0–3), moderate (4–5), and severe (6–9).

Modified score refers to AHHS low risk (0–4) and high risk (5–9).

Abbreviations: ABIC, age, serum bilirubin, INR and serum creatinine; AHHS, alcohol-associated hepatitis histologic score; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Biopsy findings in patients without AH

Five studies13,16,17,18,24 reported biopsy findings in patients not confirmed to have AH on liver biopsy. The majority of these patients had alcohol-induced cirrhosis on liver biopsy. Other findings included cholestasis, hypoxic hepatitis, alcoholic foamy degeneration, steatosis with advanced fibrosis, and infectious mononucleosis hepatitis (Supplemental Table S5, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A833).

Interobserver agreement between pathologists

Four studies9,16,22,26 reported the interobserver agreement between pathologists who assessed AHHS. The net interobserver agreement ranged from 0.33 to 0.97 (Table 6). The kappa coefficient was lowest for megamitochondria (up to 0.2)26 and highest for fibrosis staging (up to 1.0).22 SALVE criteria used in 1 study28 showed an interobserver coefficient of 0.8 for fibrosis, 0.67 for neutrophilic infiltration, and 0.65–0.66 for canalicular or ductular cholestasis. Two studies,22,25 with simple histological criteria of steatosis (ballooning, and inflammation with neutrophils) had the best interobserver agreement (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Interobserver agreement between pathologists assessing histology in alcohol-associated hepatitis

| References | Pathologists | Megamitochondria | Fibrosis stage | PMN infiltrate | Bilirubinostasis | Net value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altamirano9 | One expert liver pathologist, slides cross shared between central pathologist | 0.46 (0.27–0.65) | 0.65 (0.36–0.94) | 0.6 (0.42–0.78) | 0.86 (0.75–0.97) | 0.64 (0.53–0.80) |

| Horvath26 | Three expert liver pathologists and 2 luminal GI pathologists | 0.2 (0.03–0.46) | 0.42 (0.31–0.51) | 0.52 (0.40–0.68) | 0.52 (0.36–0.72) | 0.33 (0.20–0.51) |

| Roth16 | Three expert liver pathologists | 0.65 (0.55–0.73) | ||||

| Dubois22 | Two expert liver pathologists | 0.46 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.74 | 0.67 |

| Avitabile25 | Two expert liver pathologists | 0.97 | ||||

| Lackner28 | More than 3 pathologists | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.33a, 0.65b, 0.66c |

Notes: Numerical values represent the kappa coefficient (95% CI).

Hepatocellular cholestasis.

Canalicular cholestasis.

Ductular cholestasis.

Abbreviation: GI, gastrointestinal; PMN, polymorphonuclear cells.

Quality assessments

The ROB was high in 5 studies13,14,15,17,20 and low in the remaining 10 studies9,12,16,18,19,21,22,23,24,25 included in the quantitative meta-analysis (Supplemental Table S6, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A833). There was no difference in precision estimates of clinical criteria between studies with high and low ROB (Table 3).

Publication bias

Funnel plot (Supplemental Figure 3, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A833) and Egger’s regression with SE as a predictor of log-odds of precision showed asymmetry (z = 3.6036, p = 0.0003). Further, using the study’s sample size as a predictor instead of SE abolished the asymmetry (z = 0.660, p = 0.509), suggesting a small study effect as a plausible reason for asymmetry.

DISCUSSION

Main findings

This is the first meta-analysis that identified the precision of clinical criteria for diagnosing AH. Interestingly, studies including patients with severe disease (MELD > 20) or serum bilirubin cutoff of 5 mg/dL had a higher precision than those with a lower MELD score or serum bilirubin cutoff of 3 mg/dL. Further, the inclusion of Mallory bodies as a histology criterion for AH reduced the precision estimate of the clinical diagnosis of AH.

Variations in the precision of clinical criteria for diagnosing AH and its implications

Although clinical criteria seem reasonably accurate in diagnosing AH in 92% of individuals with severe disease (MELD > 20), about a third of patients with moderate AH (MELD < 20) may not have AH on histology and would merit a liver biopsy to confirm AH. Given a significant 90 d mortality risk of up to 10%–20% in patients with moderate AH2, investigators recruit these patients in clinical trials for drug development for AH. Our study has an impact on the sample size of studies recruiting patients with moderate AH based on the clinical criteria, as there would be a need to adjust the sample size by a margin of 33%. Although previous studies16,25 showed improved precision of clinical criteria through the addition of inflammatory markers. For example, in 1 study25 performance of NIAAA criteria showed a sensitivity of 63%, specificity of 78%, and negative predictive values of 77% in AH diagnosis, and the accuracy of NIAAA criteria improved by adding c-reactive protein values. However, we did not find any difference in precision estimates based on leukocytosis. This could be due to heterogeneity of data or selection bias, as most of the included patients may have received corticosteroids, affecting the patient’s leukocyte counts. Further, given imprecision rates of about 20%–30% for clinical criteria and to avoid false discoveries, we believe patients recruited for phase I/II trials should be confirmed through biopsy before enrolment. While for the phase III/IV trials, one can adjust for error rates of 20% in sample size estimations for robust analysis.

Liver biopsy for diagnosing AH

Liver biopsy, although considered the gold standard for AH diagnosis, has its limitations including but not limited to bleeding, pain, and physician or patient reluctance. Biopsy findings considered specific for AH may also be seen in other conditions, such as ballooning and necrosis in ischemia, Mallory-Denk bodies in cholestasis, and polymorphonuclear infiltrate in sepsis.29 Further, variations in defining AH on histology and on interobserver agreement also limit its applicability. For example, in the current study, having Mallory bodies as a mandatory criterion for histologic diagnosis of AH reduced the precision of clinical criteria in diagnosing AH. Reporting by an expert liver pathologist or >1 pathologist did not impact the precision of AH diagnosis. In fact, the greater number of pathologists involved in reporting unclear histological criteria led to the poorest interobserver reliability (0.33).26 Two studies using simple histologic criteria (steatosis, ballooning of hepatocytes, and lobular inflammation with neutrophils) had the best interobserver agreement between pathologists,22,25 suggesting a need for simple and uniform criteria for defining AH on histology. The SALVE group28 also used uniform histological criteria for AH diagnosis and showed good reliability. However, the SALVE criteria are not validated in other studies.

Liver biopsy for risk stratification in AH

The role of liver biopsy for risk stratification in AH is unclear. In the current analysis, only 2 studies9,27 observed a higher short-term mortality in patients with higher AHHS scores. It has been earlier shown that AHHS may be better in the risk stratification in patients with moderate AH with MELD < 21 and/or ABIC < 9.9,21 Very broad septa and severe pericellular fibrosis were linked to mortality in patients with AH.28 Cirrhosis with very broad septa was an independent predictor of mortality with MELD and HE in patients with AH.28 Bilirubinostasis type (hepatocellular, ductal, or canalicular) and fibrosis stage were independent predictors of a poor prognosis.28 Bilirubinostasis, a surrogate marker for impaired hepatocellular bile transport and hepatic bile flow in AH, has also been associated with the development of bacterial infection and sepsis,9 which may contribute to increased mortality.

Strengths and limitations

Although our study provides novel insights into the diagnostic precision of clinical criteria and the role of liver biopsy in patients with AH, we do recognize certain limitations of our study. We showed that studies with mean-MELD > 20 had better precision; however, this was primarily derived from high bilirubin rather than international normalized ratio or creatinine levels that may independently contribute to higher MELD scores. Therefore, we believe MELD should not be used as defining criteria for AH. Heterogeneity in estimates, nonuniform diagnostic criteria, retrospective study design across studies, small study effects, and publication bias could have affected the results. Lack of information on receipt of corticosteroids before the liver biopsy in studies limited analysis of the corticosteroid treatment on the precision of clinical criteria on AH diagnosis.24,30 We could not perform multi-variable meta-regression to ascertain the interaction of multiple factors as a reason for variation in estimates due to the limited number of studies. Finally, due to limited studies, the evidence on histology for estimating prognosis, steroid response, and infection prediction in AH remains weak and dictates the need for further evidence.

CONCLUSIONS

The clinical criteria are precise in diagnosing AH in 80% of cases with better precision (92%) among severe cases with bilirubin > 5 mg/dL and/or MELD > 20, suggesting that AH is not only a histologic diagnosis. There remains an unmet need for better criteria for diagnosing AH in patients with moderate severity. Further studies are needed to (a) derive more accurate clinical criteria for diagnosing AH (b) define AH on histology through simple and uniform criteria, and (c) establish the role of histology in predicting outcomes in patients with AH. Finally, given the risks associated with liver biopsy, noninvasive tests and biomarkers are urgently needed to improve diagnosis and risk stratification in patients with AH.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AH, alcohol-associated hepatitis; AHHS, alcohol-associated hepatitis histologic score; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; NIAAA, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; ROB, risk of bias; SALVE, Consortium for the Study of Alcohol-associated LiVer disease in Europe.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.hepcommjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Nipun Verma, Email: nipun29j@gmail.com.

Rohit Mehtani, Email: rohitmehtani.14@gmail.com.

Jacob Martin Haiar, Email: jhaiar@unmc.edu.

Pranita Pradhan, Email: pranita2009@gmail.com.

Ajay Duseja, Email: ajayduseja@yahoo.co.in.

Gene Young Im, Email: gene.im@mountsinai.org.

Ashwani K. Singal, Email: ashwanisingal.com@gmail.com.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Ashwani K. Singal and Nipun Verma. Data Curation: Rohit Mehtani, Nipun Verma, and Jacob Martin Haiar. Formal analysis, Resources, Software, and Visualization: Nipun Verma. Investigation: Nipun Verma, Rohit Mehtani, Jacob Martin Haiar, and Pranita Pradhan. Methodology: Nipun Verma, Ashwani K. Singal, and Pranita Pradhan. Project administration and Supervision: Ashwani K. Singal. Validation: Nipun Verma, and Rohit Mehtani. Writing original draft: Rohit Mehtani, Nipun Verma. Writing review and editing: Nipun Verma, Rohit Mehtani, Ajay Duseja, Gene Young Im, and Ashwani K. Singal.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Gene Im consults for Corro Bio and received grants from Echosens. Ashwani Singal consults and owns stock in Pleiogenix. He advises Durect. The remaining authors have no conflicts to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, Austin A, Bowers M, Day CP, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1619–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clemente-Sánchez A, Oliveira-Mello A, Bataller R. Moderate alcoholic hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2021;25:537–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thursz M, Gual A, Lackner C, Mathurin P, Moreno C, Spahr L, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;69:154–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crabb DW, Im GY, Szabo G, Mellinger JL, Lucey MR. Diagnosis and treatment of Alcohol‐Associated Liver Diseases: 2019 Practice Guidance From the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2020;71:306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crabb DW, Bataller R, Chalasani NP, Kamath PS, Lucey M, Mathurin P, et al. Standard definitions and common data elements for clinical trials in patients with alcoholic hepatitis: Recommendation From the NIAAA Alcoholic Hepatitis Consortia. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:785–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ Published online March, 292021:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Association for the Study of Liver . EASL clinical practical guidelines: Management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:399–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucey MR, Mathurin P, Morgan TR. Alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2758–2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altamirano J, Miquel R, Katoonizadeh A, Abraldes JG, Duarte–Rojo A, Louvet A, et al. A histologic scoring system for prognosis of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1231–1239 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whiting PF. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCullagh P, Nelder J. Generalized Linear Models, 2nd ed. Chapman & Hall: CRC Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mookerjee RP, Lackner C, Stauber R, Stadlbauer V, Deheragoda M, Aigelsreiter A, et al. The role of liver biopsy in the diagnosis and prognosis of patients with acute deterioration of alcoholic cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1103–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy T, Wells C, Kendrick S, Hudson M, Day CP, Burt AD, et al. White cell count and platelet count associate with histological alcoholic hepatitis in jaundiced harmful drinkers. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudler M, Mouri S, Charlotte F, Lebray P, Capocci R, Benosman H, et al. Prognosis of treated severe alcoholic hepatitis in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. J Hepatol. 2015;62:816–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudler M, Mouri S, Charlotte F, Cluzel P, Ngo Y, Munteanu M, et al. Validation of AshTest as a non-invasive alternative to transjugular liver biopsy in patients with Suspected severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0134302; Sookoian SC, ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roth NC, Saberi B, Macklin J, Kanel G, French SW, Govindarajan S, et al. Prediction of histologic alcoholic hepatitis based on clinical presentation limits the need for liver biopsy. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1:1070–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shetty S, Venkatakrishnan L, Krishanveni J, Kumari S. Transjugular liver biopsy in severe alcoholic hepatitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2017;36:23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bissonnette J, Altamirano J, Devue C, Roux O, Payancé A, Lebrec D, et al. A prospective study of the utility of plasma biomarkers to diagnose alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 2017;66:555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shasthry SM, Rastogi A, Bihari C, Vijayaraghavan R, Arora V, Sharma MK, et al. Histological activity score on baseline liver biopsy can predict non-response to steroids in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Virchows Arch. 2018;472:667–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choudhary NS, Saigal S, Gautam D, Saraf N, Rastogi A, Goja S, et al. Good outcome of living donor liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis not responding to medical management: A single center experience of 39 patients. Alcohol. 2019;77:27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DH, Choi YI, Bae JM, Chang MS, Joo SK, Jung YJ, et al. Prognostic value of the alcoholic hepatitis histologic score in korean patients with biopsy-proven alcoholic hepatitis. Gut Liver. 2020;14:636–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubois M, Sciarra A, Trépo E, Marot A, Saldarriaga J, Moreno C, et al. Histologic parameter score does not predict short‐term survival in severe alcoholic hepatitis. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:1003–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atkinson SR, Grove JI, Liebig S, Astbury S, Vergis N, Goldin R, et al. In severe alcoholic hepatitis, serum keratin-18 fragments are diagnostic, prognostic, and theragnostic biomarkers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1857–1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forrest E Petts G Austin A Lloyd K Wright M Vergis N et al.. The diagnostic and prognostic significance of liver histology in alcoholic hepatitis. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Avitabile E, Díaz A, Montironi C, Pérez-Guasch M, Gratacós-Ginès J, Hernández-Évole H, et al. Adding inflammatory markers and refining National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Criteria improve diagnostic accuracy for alcohol-associated hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:3080–3088.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horvath B, Allende D, Xie H, Guirguis J, Jeung J, Lapinski J, et al. Interobserver variability in scoring liver biopsies with a diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41:1568–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrade P, Silva M, Rodrigues S, Lopes J, Lopes S, Macedo G. Alcoholic hepatitis histological score has high accuracy to predict 90-day mortality and response to steroids. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:656–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lackner C, Stauber RE, Davies S, Denk H, Dienes HP, Gnemmi V, et al. Development and prognostic relevance of a histologic grading and staging system for alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2021;75:810–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacSween R, Burt A. Histologic spectrum of alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 1986;6:221–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haiar J, Singal AK. Editorial: Liver biopsy in alcoholic hepatitis—more clarity on when it may be needed. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53:630–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]