Abstract

A granuloma is a discrete collection of activated macrophages and other inflammatory cells. Hepatic granulomas can be a manifestation of localized liver disease or be a part of a systemic process, usually infectious or autoimmune. A liver biopsy is required for the detection and evaluation of granulomatous liver diseases. The prevalence of granulomas on liver biopsy varies from 1% to 15%. They may be an incidental finding in an asymptomatic individual, or they may represent granulomatous hepatitis with potential to progress to liver failure, or in chronic disease, to cirrhosis. This review focuses on pathogenesis, histological features of granulomatous liver diseases, and most common etiologies, knowledge that is essential for timely diagnosis and intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Granulomas are a collection of activated macrophages and other inflammatory cells and may be the result of a variety of conditions, usually infectious or autoimmune. Granulomas are found in diseases isolated to the liver or may reflect systemic illness, and the disease severity may range from an asymptomatic state to severe granulomatous hepatitis with portal hypertensive complications.

Diagnosis of hepatic granulomas relies on liver biopsy and the most common scenario leading to the discovery of granulomas is that of a liver biopsy performed for the workup of abnormal liver enzymes or for confirmation of hepatic involvement in a systemic process that shows granulomas. When granulomas are found incidentally, there is often a diagnostic challenge; a comprehensive history and physical exam are crucial for making the correct underlying diagnosis. The physician’s role is to stratify the risks and to decide whether the incidental finding of granulomas requires further investigation. This review details pathogenesis, established common and emerging causes of granulomatous liver diseases (GLD), and histological features.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of granulomas on liver biopsy ranges from 1% to 15%.1,2 It is challenging to make accurate estimates of the real prevalence of hepatic granulomas since not every patient evaluated by a hepatologist undergoes a liver biopsy. The etiologies of hepatic granulomas differ geographically. While in the Western world, noninfectious autoimmune conditions such as primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) are prevalent, in the Middle East and Asia infections remain the leading causes of hepatic granulomas. Tuberculosis (TB), leishmaniasis, and viral hepatitis account for the most frequent causes in the developing world (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Top etiologies of hepatic granulomas in cohorts from different countries

| References | Top cause | Other |

|---|---|---|

| United States3 | Idiopathic (50%) | Sarcoidosis (22%), drug-related (6%), PBC (5%), histoplasmosis (5%), and TB (3%). |

| Pakistan4 | TB (88.9%) | Sarcoidosis (7.4%), PBC (3.7%). |

| Iran5 | TB (53%) | Visceral leishmaniasis (8.3%), visceral larva migrans, PBC, and hepatitis C (4.2% each). |

| Saudi Arabia6 | TB (42.6%) | Hepatitis C (14.8%), idiopathic (14.8%), schistosomiasis (5%), sarcoidosis (5%). |

| Greece7 | PBC (62%) | Sarcoidosis (7.5%), hepatitis B and C (7.5%), autoimmune hepatitis (6%), idiopathic (6%). |

| Turkey8 | PBC (44.2%) | Infections - mycobacterial, echinococcal, and hepatitis C (39.5%) malignancy—HCC, cholangiocarcinoma, and others (5.8%), sarcoidosis (4.7%), and foreign body (3.5%). |

| Portugal9 | TB (35.8%) | PBC (15.0%), idiopathic (12.5%), hepatitis C (6.3%). |

| Germany10 | PBC (48.6%) | Undiagnosed/idiopathic (36%), sarcoidosis (8.4%). |

| Ireland11 | PBC (23.8%) | Sarcoidosis (11.1%), idiopathic (11.1%), hepatitis C (9.5%), drug-related (7.9%), PBC/autoimmune hepatitis overlap (6.3%), Hodgkin disease (6.3%), autoimmune hepatitis (4.8%), TB (4.8%). |

| Australia12 | Chronic liver disease: alcoholic hepatitis/cirrhosis, hepatitis B, secondary hemochromatosis (20%) | Sarcoidosis (12%), infections - cytomegalovirus, Q fever, hepatitis B, Coxsackie B (12%), malignancy (8%), drug-related (7%), TB (7%). |

| India13 | TB (55%) | Leprosy (17.6%), Hodgkin’s disease (3.6%). |

Abbreviations: PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; TB, tuberculosis.

The prevalence and etiology differ among different patient subpopulations, especially those who are predisposed to hepatic granulomas by virtue of an underlying condition, usually an inborn or acquired immunodeficiency or immunosuppression. GLD was found in about one-third of the patients infected with HIV, who had a liver biopsy as a workup of hepatomegaly, fever of unknown origin (FUO), or elevated transaminases.14,15 Opportunistic infection with various mycobacteria, especially Mycobacterium tuberculosis, remains the leading cause of liver granulomas in patients with HIV prior to and during the antiretroviral therapy eras.14,15,16,17 In a single-center study of 301 patients with HIV, hepatic granulomatous inflammation was present in 29% of the patients, with more than half having TB immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.18 In another study, the prevalence of granulomas in solid organ and hemopoietic stem cell transplant recipients was explored. Hepatic granulomas were found in 0.8% of all recipients of transplantation, with most of them thought to be noninfectious (72%). Eighty-nine percent were found in recipients of liver transplant with the most frequent underlying cause being graft-versus-host disease and idiopathic, presumed noninfectious.19

PATHOGENESIS

Exposure to a foreign body, bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, or antigenic stimuli triggers an initial immune response and recruitment of inflammatory cells. Granulomas are a manifestation of inflammation, most often part of an effort to biochemically degrade a foreign substance, bacteria, or persistent antigenic stimulus. The latter may be exemplified by sarcoidosis or DILI.1,2,20 The pathophysiological cascade in GLD involves innate and adaptive immunity and consists of several steps: initial innate immune response, macrophage activation, T-cell and B-cell activation, and finally, granuloma formation, all of which may eventually result in hepatic fibrosis.

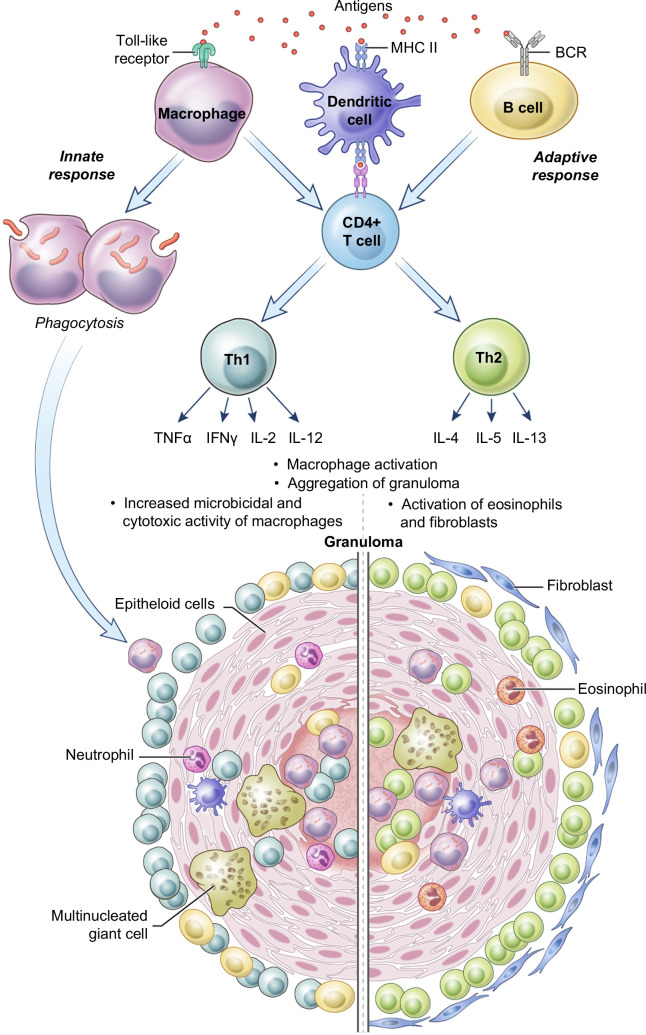

Granuloma formation represents helper T-cell–mediated delayed hypersensitivity reaction, and the two primary components of this process are resident macrophages and CD4+ T-cells.20 Antigenic stimulus through toll-like receptors attracts macrophages to the site of inflammation as a part of an innate immune response. Macrophages engulf and try to destroy the invader through phagocytosis. Macrophages, B-cells, and dendritic cells serve as Ag-presenting cells in the generation of the adaptive immune response and play a role in CD4+ T helper cell modulation and initiation of CD4+ T helper type 1 (Th1) and 2 (Th2) cytokine responses. Activation of macrophages by cytokines is further required for granuloma formation (Figure 1). Th1 activation dominates in granulomatous inflammation that usually involves intracellular pathogens such as mycobacteria, leishmania, or idiopathic inflammatory diseases like sarcoidosis. It is mainly facilitated by pro-inflammatory cytokines interferon-gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and IL-2, IL-6, and IL-12. Th2 cytokine response with IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 is most prominent in parasitic infections, such as schistosomiasis.21 Interestingly, in schistosomiasis the initial response is Th1, then ova Ags promote the switch to Th2 response shortly after an infection. In schistosomiasis, the ova cause the most pronounced granulomatous response, and the Th2 response helps to prevent further inflammation. An additional source of IL-4 in parasitic infections is eosinophils.22 Interferon-gamma-γ may play a protective role against fibrosis in schistosomiasis, while IL-10 may control excessive Th1 and Th2 polarization of granulomatous response.23 In animal studies, levels of IL-13 correlate with collagen deposition, fibrosis, and the severity of portal hypertension in schistosomiasis.24

FIGURE 1.

Pathogenesis of granuloma formation. Bacteria or any foreign organism can be phagocytosed by macrophages as a part of the innate immune response. In the adaptive response, antigen is presented to the CD4+ T-cells through Ag-presenting cells: macrophages, dendritic cells, and B-cells. The Th1 pathway involves the release of TNF-α, INF-γ, IL-2, IL-12, and other pro-inflammatory cytokines and it is critical in sarcoidosis and tuberculosis. The Th2 response is mediated through IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, and it plays a role in helminth infections such as schistosomiasis. Abbreviations: INF-γ, interferon-gamma; Th2, T helper type 2; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha).

Activated macrophages further aggregate to form organized granulomas. Granulomas are dynamic structures, and they may undergo fibrosis, a common outcome, or necrosis as they mature. Fibrosis is facilitated through the secretion of growth factors and extracellular matrix proteins by macrophages, and it may occur in both noninfectious settings, such as foreign body granulomas, and in infection-related granulomas.25 In schistosomiasis, the fibrotic response is coordinated by HSC, which secrete a range of profibrotic chemokines, including chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2.26 Granulomas, especially those of infectious etiology, can undergo necrosis. One of the remarkable examples is the caseating tuberculous granuloma, where necrosis is associated with increased bacterial proliferation. Proteomic analysis of necrotic foci has shown large amounts of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids, such as leukotriene B4, and prostanoids, such as cyclooxygenase-1 and 2. Animal models have shown an abundance of TNF-α and reactive oxygen species within necrotic foci, which play microbicidal roles, but also may be destructive to the tissues.27

A genetic predisposition may contribute to susceptibility to granulomatous disease. Human leukocyte Ag DRB1 was recognized as a marker of predisposition to sarcoidosis.28 Analysis of familial and sporadic cases of sarcoidosis identified a variant of butyrophilin-like 2 gene BTNL2 that is a risk factor for sarcoidosis independent of Human leukocyte Ag predisposition.29 Whole exome sequencing in patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) has shown that patients with identifiable underlying monogenic causes (about 30% of CVID cases) are more likely to have complicated courses, including granulomatous infiltrates, rather than infections only.30 Potential genes associated with hepatic granulomas in CVID include, but are not limited to, recombination-activating gene 1 and nuclear factor kappa B subunit 1.31

HISTOPATHOLOGY

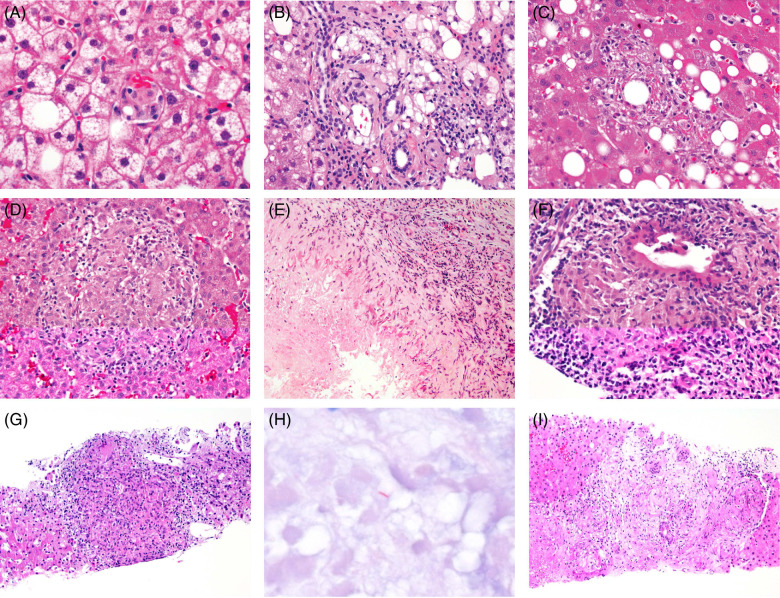

Liver biopsy plays a pivotal role in the diagnosis of GLD. It can be done for investigation of a systemic disorder with liver involvement, or an isolated hepatic process. The histological term used for activated macrophages, “epithelioid histiocyte,” is based on their appearance and it is reflected in the names of some types of granulomas (Table 2 and Figure 2). Compared to the inactive macrophages, the epithelioid histiocytes have more cytoplasm with fewer lysosomes, a regular elongated shape, and sometimes multiple, peripherally-located nuclei.32,33 They also lose their pseudopods, giving the cell a smooth outline. The location of granulomas in the liver depends on the etiology. Suture granulomas are found in the vicinity of prior surgery, while talc granulomas are most of the time located in portal areas. Sarcoidosis, PBC, and infectious granulomas often spread diffusely in the liver affecting portal, intra-acinar, periductal, and ductal areas.32 The peri-granulomatous liver tissue may be unchanged, or it may show increased lymphocytic inflammation.1

TABLE 2.

Histological types of granulomas and the associated conditions

| Type of granuloma | Associated disease |

|---|---|

| Microgranuloma | Nonspecific |

| Lipogranuloma | Steatotic liver disease, hepatitis C |

| Fibrin-ring granuloma | Q fever (Coxiella), leishmaniasis, toxoplasmosis, Hodgkin disease, ICIs-related granulomas |

| Epithelioid necrotizing granuloma | TB, nocardiosis, fungal infections |

| Epithelioid non-necrotizing granuloma | Sarcoidosis, hepatitis C, PBC, DILI |

Abbreviations: ICIs, immune checkpoint inhibitors; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; TB, tuberculosis.

FIGURE 2.

Histological features of hepatic granulomas. (A) Microgranuloma in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis, H&E, ×600. (B) Lipogranuloma in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis, H&E, ×400. (C) Fibrin-ring granuloma in drug-induced injury due to the ICIs ipilimumab and nivolumab, H&E, ×400. (D) Non-necrotizing epithelioid granuloma in autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, H&E, ×400. (E) Necrotizing epithelioid granuloma in eosinophilic hepatitis, H&E, ×200. (F) Florid duct lesion of primary biliary cholangitis, H&E, ×400. (G) Mycobacterial granuloma, H&E, ×200. (H) Mycobacterium tuberculosis on acid-fast bacilli stain, ×600. (I) Granulomas in sarcoidosis, H&E, ×200. Abbreviations: H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Microgranulomas are small collections of macrophages, only 3 to 7 cells in cross-section, and they represent a nonspecific reaction to a liver injury.20 They are frequently seen in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease, PBC, and DILI. They do not have independent significance and are unlikely to be associated with major parenchymal abnormalities.12

Lipogranulomas represent a collection of vacuolated fat droplets, and they were initially considered an incidental finding without clinical significance. The use of mineral oil in the food industry was thought to be responsible for the increased incidence of lipogranulomas in liver biopsies.34 It was subsequently shown that lipogranulomas are associated with steatosis of any etiology, including metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease, and less frequently, alcohol.35 They are usually located within portal or acinar areas, especially adjacent to hepatic veins. Large portal lipogranulomas may lead to portal expansion and give a false impression of “fibrosis.” Variable amounts of collagen fibers may be seen within and around lipogranulomas, as well as rare eosinophils.32,36,37 In 58 patients with lipogranulomas on the liver biopsy, the most frequent underlying etiology was either hepatitis C or steatotic liver disease.38 Lipogranulomas were evident in 19% of biopsies done for the workup of DILI.39

Fibrin-ring granulomas were initially described in association with granulomatous hepatitis in Coxiella burnetii infection (Q fever) by Bernstein.40 Their distinct feature is the presence of a central round fat vacuole surrounded by a fibrin ring and an outer layer of histiocytes. They are usually small in size and intralobular. Masson trichrome stain is useful for staining the eosinophilic fibrin ring.20,41 Although highly suggestive of Q fever, they are found in other etiologies as well. In a study of 23 biopsies with evidence of fibrin-ring granulomas, Q fever accounted for 43% of the cases, followed by visceral leishmaniasis in 22% and boutonneuse fever, caused by various species of Rickettsia, in 13%. A smaller proportion of cases were associated with toxoplasmosis, allopurinol-induced liver injury, and Hodgkin’s disease.41 Association with autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus and giant cell arteritis are also reported.42,43 The current focus has shifted from infections toward DILI: fibrin-ring granulomas are reported in patients with granulomatous hepatitis due to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), both anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-L1.44,45

Epithelioid granulomas are mostly composed of epithelioid cells but may also contain lymphocytes and other inflammatory cells and fibroblasts. They are often associated with specific infectious and noninfectious disorders, and they are categorized as non-necrotizing and necrotizing. Necrosis is found in the center of the epithelioid granuloma. “Caseating necrosis” is a term to describe the macroscopic picture associated with complete loss of tissue structure, with TB being a classic example.46 Necrotizing epithelioid granulomas are prevalent in infections such as nocardiosis, fungal infections, including histoplasmosis, and fascioliasis; an association with DILI has been reported as well.47,48,49,50 Non-necrotizing epithelioid granulomas may be either poorly or well-formed. Well-formed granulomas are seen in sarcoidosis and infections like hepatitis C.20,51 Poorly formed granulomas are infiltrated by lymphocytes, which can obscure the normal cohesive granuloma structure. They may be found in immune-mediated conditions, PBC, DILI, or T-cell–mediated rejection after a liver transplant.2,52 “Granulomatous inflammation” refers to an inflammatory reaction involving epithelioid cells when granulomas fail to form.32 Epithelioid granulomas that are not associated with a known etiology should be stained for infectious organisms.

ETIOLOGY

The etiologies of hepatic granulomas can be broadly categorized as infectious and noninfectious (Table 3). The diagnosis of idiopathic granuloma is made when no underlying cause can be identified. In this section, the focus is made on the most common etiologies.

TABLE 3.

Most common etiologies of hepatic granulomas

| Infectious etiologies | Noninfectious etiologies |

|---|---|

| Bacterial infections | Autoimmune disease |

| Nocardiosis47 | Sarcoidosis53 |

| Mycobacterial infections, including M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. avium 17,54 | Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis55 |

| Brucellosis56 | Giant cell arteritis57 |

| Q fever (Coxiella burnettii)12 | Granulomatosis with polyangiitis58 |

| Cat-scratch disease (Bartonellosis)59 | Crohn’s disease60 |

| Syphilis61 | Primary biliary cholangitis62 |

| Actinomycosis63 | Immunodeficiencies, inborn and acquired |

| Fungal infections | Common variable immunodeficiency64 |

| Histoplasmosis65 | Chronic granulomatous disease66 |

| Blastomycosis67 | Human immunodeficiency virus infection18 |

| Coccidioidomycosis68 | Medications |

| Candidiasis (in the setting of neutropenia)69 | Acetaminophen70 |

| Viral infections | Allopurinol71 |

| Hepatitis A, B, C6,51,72 | Albendazole73 |

| Epstein-Barr virus74 | Amoxicillin-clavulanate75 |

| Cytomegalovirus76 | Diltiazem77 |

| Parasitic infections: | Etanercept78 |

| Helminthic infections: | Infliximab79 |

| Ascaridosis80 | Ipilimumab81 |

| Fascioliasis82 | Mebendazole83 |

| Schistosomiasis, including S. japonicum and S. mansoni 67 | Mesalamine84 |

| Protozoal infections: | Nivolumab81 |

| Toxoplasmosis85 | Vemurafenib86 |

| Leishmaniasis87 | Rosiglitazone88 |

| Sulfasalazine89 | |

| Quinidine90 | |

| Hodgkin’s disease91 | |

| Foreign body | |

| Talc20 | |

| Surgical material92,93 | |

| Prosthetic devices94 | |

| Implants95 | |

| Idiopathic granulomas |

Foreign body granuloma

Granuloma formation is a localized inflammatory response that occurs in an attempt to react and isolate exogenous material. It includes materials like sutures, sponges, implants, or other particles that enter the body during an injury.92,93 Hepatic and splenic granulomas containing microscopic metallic particles were found in 38% of the autopsies of patients with a history of hip or knee replacement. Foreign body granulomas may also cause hepatitis with fatigue, jaundice, and weight loss.94 Isolated elevation of alkaline phosphatase and non-necrotizing granulomas containing silicone material are described in patients with ruptured breast implants.95

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disorder, mostly prevalent in women of young and middle age between 20 and 50 years. The pathogenesis of sarcoidosis is poorly understood, and it is thought to develop due to a combination of factors, including genetic predisposition, environmental, and even bacterial triggers.96 It usually affects the lungs and mediastinal lymph nodes, but it can also involve the liver in 6%–18% of the cases with the majority of the patients being asymptomatic.97,98 Having hepatic involvement at the time of diagnosis is a predictor of chronic disease in sarcoidosis.98 Symptomatic patients often present with nonspecific complaints such as fatigue, night sweats, and fever. Hepatic symptoms often resemble cholestatic liver disease, PBC, or primary sclerosing cholangitis, manifesting with pruritus, jaundice, anorexia, and elevated alkaline phosphatase.99 Sarcoidosis may involve up to 90% of the liver volume, which can lead to intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary obstruction. Non-necrotizing granulomas are a predominant feature of hepatic sarcoidosis, although bile duct injury, chronic portal inflammation, and vascular changes, such as sinusoidal dilation and nodular regenerative hyperplasia, may also be seen on the biopsy.100 Fibrosis and cirrhosis are encountered in 20–29% of the biopsies,100,101 and may eventually become complicated by portal hypertension (PH). In a case series of 12 patients with PH due to sarcoidosis, 7 patients died, 6 of them due to complications of PH, and 2 patients received liver transplants.102 Sarcoidosis is also a known cause of noncirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH);99 reversal of NCPH in sarcoidosis with steroid treatment has been reported.103

Primary biliary cholangitis

PBC, formerly known as primary biliary cirrhosis or nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis, is an autoimmune slowly progressive, cholestatic liver disease associated with inflammation and destruction of the small bile ducts. Granulomas are usually evident in early disease, characterized by portal inflammation, sometimes called the florid duct lesion stage.62 The florid duct lesion is a diagnostic histological feature of PBC and represents a damaged bile duct, surrounded by lymphocytes and plasma cells, with adjacent granulomas. Granulomas are mostly epithelioid, non-necrotizing, and are poorly formed, with many infiltrating lymphocytes that disrupt the structure. As the disease evolves, granulomas become less prominent.104 Immunological studies showed that dendritic cells and immunoglobulin M are key factors in the formation and evolution of granulomas in PBC.105 The presence of granulomas is thought to be associated with better patient survival;106 this is likely explained by the fact that the granulomas are an early finding in PBC. While granulomas are a hallmark of PBC, in primary sclerosing cholangitis they are usually an incidental finding.20

Inborn errors of immunity

Advancements in medicine and the use of prophylactic antibiotics have dramatically increased survival in patients with inborn errors of immunity, and as a result, recognition of hepatic disorders. Hepatic granulomas are a signature of CVID and chronic granulomatous disease (CGD).107 CVID refers to a spectrum of disorders typically associated with adult-onset antibody deficiency, but a subgroup of cases have granulomas in the lung, liver, and spleen. Liver disease has been associated with higher mortality in CVID.108 Up to 22% of the patients with CVID may develop granulomas, with about one-third of them located in the liver. Hepatic granulomatosis in CVID is frequently associated with nodular regenerative hyperplasia. These conditions altogether lead to NCPH, the most common and morbid sequela of which are variceal bleeding, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.64,109,110 CGD is due to defects in the NADPH oxidase complex, which is required for the production of reactive oxygen species by phagocytes. CGD leads to impaired innate and adaptive immune responses and with resulting susceptibility to infection with organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus, Serratia marcescens, Burkholderia cepacia complex, Nocardia species, and Aspergillus and other fungi.66 Along with liver abscesses, non-necrotizing granulomas are the most common histological finding in CGD and are found in up to 74% of the patients. Granulomas may alter the architecture of small portal veins and lead to an obliterative portal venopathy and nodular regenerative hyperplasia, and as a result lead to NCPH.111,112

Inflammatory bowel disease

Abnormal liver enzymes have been reported in up to 30% of all patients with inflammatory bowel disease, with chronic liver disease developing only in 6% of the patients.113 GLD is an infrequent complication that is encountered more in Crohn’s disease than in ulcerative colitis. Hepatic granulomas have been reported in 6% of liver biopsies of patients with Crohn’s disease.60 In a study from Northern Ireland, only 1.8% of GLD was accounted for by Crohn’s disease. Well-circumscribed epithelioid granulomas within portal tracts were a characteristic feature found on biopsy.114 Symptomatic patients usually present with signs of cholestasis. Granulomatous hepatitis may also be induced by sulfasalazine or mesalamine therapies used for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease.84,89

Drug-induced liver injury

Granulomas due to DILI are suspected when there is a temporal association with exposure to a drug and other, more common causes of GLD have been excluded. Several medications have been linked to GLD, the most common are mentioned in Table 2. Granulomatous injury may have acute or delayed onset and it may be accompanied by features of hypersensitivity such as rash, eosinophilia, and fever. Liver enzymes are often elevated in a cholestatic pattern. Drug-induced granulomas are usually non-necrotizing, epithelioid, and located in portal areas, and they may lead to vascular or duct injury. The presence of eosinophils supports a drug etiology.20,115 In the study by Kleiner et al, the finding of granulomas and eosinophils in DILI was linked to mild cases.39

Several cases of GLD have been reported in association with the anti-TNF modulators, infliximab, and etanercept, used for psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis, among other diseases; discontinuation of the medications led to normalization of liver function.78,79,116 At the same time, infliximab has been successfully used for off-label treatment in sarcoid granulomatosis and idiopathic granulomatous hepatitis.117,118 Variations in pro-inflammatory and immunoregulatory TNF properties in different diseases may correlate with the variability in the response to anti-TNF therapies.

Iatrogenic granulomatous hepatitis was reported after injection of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), a live attenuated Mycobacterium bovis used for vaccination against TB and also as immunotherapy for bladder cancer and melanoma.119,120,121 Mutations in genes responsible for the generation and response to INF-gamma and IL-12 are associated with an increased risk of disseminated BCG infection.122 Animal studies showed that liver injury in BCG infection is likely mediated through TNF-receptor 1.123 In the case of disseminated infection following BCG instillation for bladder cancer, granulomatous hepatitis is usually an early complication with occurrence after a median of 1 week, compared to cardiovascular and bone injury that develops after a year. Up to 18% of all cases of disseminated BCG infection after use for bladder cancer involve the liver.54

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors and ICIs are medications of current interest in DILI research. They improve survival in patients with melanoma, head and neck cancer, non-small-cell lung cancer, and many others, but at the same time, they are associated with immune-mediated adverse events. ICI treatment in particular may be complicated by systemic granulomatous sarcoid-like reactions.124 Granulomatous hepatitis was reported in association with the tyrosine kinase inhibitors vemurafenib, and the ICIs nivolumab and ipilimumab.81,86 The granulomatous injury with ICIs may present in hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed patterns.125 The presence of pre-existing antinuclear antibodies along with granulomas on histology may serve as potential markers of ICI-related hepatitis.126

Bacterial infections

Granuloma formation is a distinct feature of multisystem mycobacterial infections like TB or leprosy. TB remains a global health challenge: the estimated death toll in 2021 was 1.6 million people.127 It usually presents as a pulmonary infection, with hepatic TB in an extrapulmonary location. Up to 85% of hepatic TB occurs as part of systemic infection, and rarely as an isolated finding. Symptomatic patients present with fever, weight loss, jaundice, and hepatosplenomegaly, sometimes associated with portal hypertension.128,129 Hepatic TB can be disseminated, miliary, or focal in the form of tuberculoma or abscess; the main histological feature of both forms is the epithelioid necrotizing granuloma.17 Its function is to contain infection: in TB the inner part of granuloma has a pro-inflammatory environment, while the outside layer is anti-inflammatory. The balance between these two is thought to be responsible for the host’s ability to isolate infection and prevent dissemination.27 The histological diagnosis is confirmed with acid-fast bacilli stain and culture, although the acid-fast bacilli stain cannot distinguish between the different types of mycobacteria. PCR and the PCR-based MTB/RIF assay are more sensitive in the diagnosis of pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB than acid-fast bacilli stain alone.130

Hepatic granulomas are associated with many other bacterial infections. Fibrin-ring granulomas are typical lesions of Coxiella burnettii infection or Q fever, although granulomas without characteristic annular arrangement or fibrinoid material can be also found.131 Up to half of the patients with liver disease due to brucellosis present with tender hepatomegaly and increased serum liver enzymes. In the study by Cervantes et al, non-necrotizing granulomas were found in 70% of the liver biopsies and most of them had disease durations less than 100 days. This suggests that granulomas in brucellosis may be a feature of acute disease.56 Cat-scratch disease, due to Bartonella henselae, is usually a self-limiting disease, although rare cases of granulomatous hepatitis have been reported in children and young adults. Positive Bartonella serologies and bacteria visible on the silver stain confirm the diagnosis.59,132 Actinomycosis is typically associated with cervicofacial infections, but it also causes abdominal disease with the liver being involved in 15%–20% of cases as abscesses or granulomas mimicking metastasis.63,124,133 Poorly formed non-necrotizing granulomas are found in 36% of the patients with hepatic involvement in secondary syphilis. Granulomas are also associated with a hepatic fibroinflammatory mass lesion, which may represent early gumma or granuloma of tertiary syphilis.61

Viral infections

Granulomas are occasionally reported in association with hepatotropic viruses like hepatitis A, B, and C.7,9,12 Transient fibrin-ring granulomas were observed in a patient with acute hepatitis A and disappeared during the recovery phase.72 Transient epithelioid granulomas were found in 2% of the patients with hepatitis C; the authors had explored the possible association of granulomas with interferon-alpha treatment; however, only 1 patient of the 5 identified had granulomas on posttreatment biopsy and lacking specific features of DILI.51 Another study reported 2 cases of granulomatous hepatitis likely caused by interferon-alpha treatment, 1 in hepatitis C and another in hepatitis B, which led to treatment cessation in both.134 The advent of direct-acting antiviral agents for hepatitis C has led to a marked decrease in interferon treatment. Nonhepatotropic viruses like cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr may lead to granulomatous hepatitis and fulminant liver failure, particularly in immunocompromised hosts.74,76 Although the knowledge of hepatic involvement with SARS-CoV-2 is still limited, GLD has not been reported in association with this infection.135

Fungal infections

Fungal infections predominantly impact immunocompromised hosts. In the case of invasive candidiasis in acute leukemia, hepatosplenic involvement may be seen in up to 29% of patients. The most common hepatic lesions are granulomas and microabscesses.69,136 Histoplasma and Coccidioides enter the host by inhalation of the spores and usually result in asymptomatic pulmonary infection. In approximately half of infected immunocompromised individuals, histoplasmosis may disseminate. Patients with hepatic histoplasmosis present with fever and hepatomegaly, as well as diarrhea and abdominal pain due to gastrointestinal involvement. Granulomas are seen in both portal and lobular areas and are found in 19% of the patients with hepatic histoplasmosis.65 In a study of 7 patients with hepatic coccidioidomycosis, all presented with febrile illness and had multiple granulomas containing spherules on liver biopsy.68 Disseminated fungal infections usually lead to fatal outcomes if untreated.

Parasitic infections

Schistosomiasis is a tropical disease that impacts more than 250 million individuals worldwide, with the majority of those infected living in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is caused by Schistosoma species such as S. mansoni and S. japonicum; the typical source of larvae is contaminated water. The parasites penetrate the skin and reach the liver via hematogenous spread. The eggs induce an immunological cascade in the portal tracts causing granuloma formation and fibrosis, resulting in partial or complete obliteration of portal veins. Early infection presents in an acute form, also called Katayama fever, with fever, pruritic rash, myalgias, and tender hepatosplenomegaly.67 Untreated infection may progress to advanced fibrosis, complicated by PH and risk for HCC. Schistosomiasis is the main cause of NCPH in endemic-developing countries.137 Granulomatous disease and complications of PH such as variceal bleeding and encephalopathy are included in a predictive model to estimate 1-year mortality in advanced S. japonicum infection.138

GLD is reported with fascioliasis, another type of liver fluke, which spreads to the liver after ingestion and penetration of the intestinal wall by immature worms. Untreated acute infection is characterized by right upper quadrant pain, fever, and hepatomegaly, and is followed by a chronic phase with necrotic granulomas and the growth of worms within the biliary tree leading to cholestasis and recurrent cholangitis.67 The macroscopic appearance of the liver shows scarring and yellow nodules that may mimic metastasis.82 Helminth infections require systemic treatment; paradoxically, granulomatous hepatitis has been reported in association with mebendazole and albendazole.73,83

The most common protozoal organisms associated with GLD are Leishmania species, although rare cases of hepatic granulomas are also reported in toxoplasmosis and giardiasis.85,139 Leishmaniasis is endemic to Asia, the Middle East, East Africa, and the Mediterranean region. Patients with visceral leishmaniasis present primarily with fever, weight loss, and hepatosplenomegaly. Infection may cause extensive granulomatous hepatitis with fibrin-ring granulomas being the predominant lesions.87,140

Workup of fever of unknown etiology

GLD may be found when a liver biopsy is pursued for the workup of FUO. An early study by Simon et al found granulomatous hepatitis in 6.5% of the patients with prolonged fever; a definite diagnosis, Hodgkin’s disease, was made in only 1 patient.141 In the study by Holtz et al, 4 out of 24 liver biopsies done for FUO were diagnostic (16.7%); they found 3 cases of histoplasmosis and 1 case of TB.142 In another study, the diagnosis was established in 26% of cases of FUO: those patients had Coxiella (Q fever), mycobacterial infection, and histoplasmosis.143

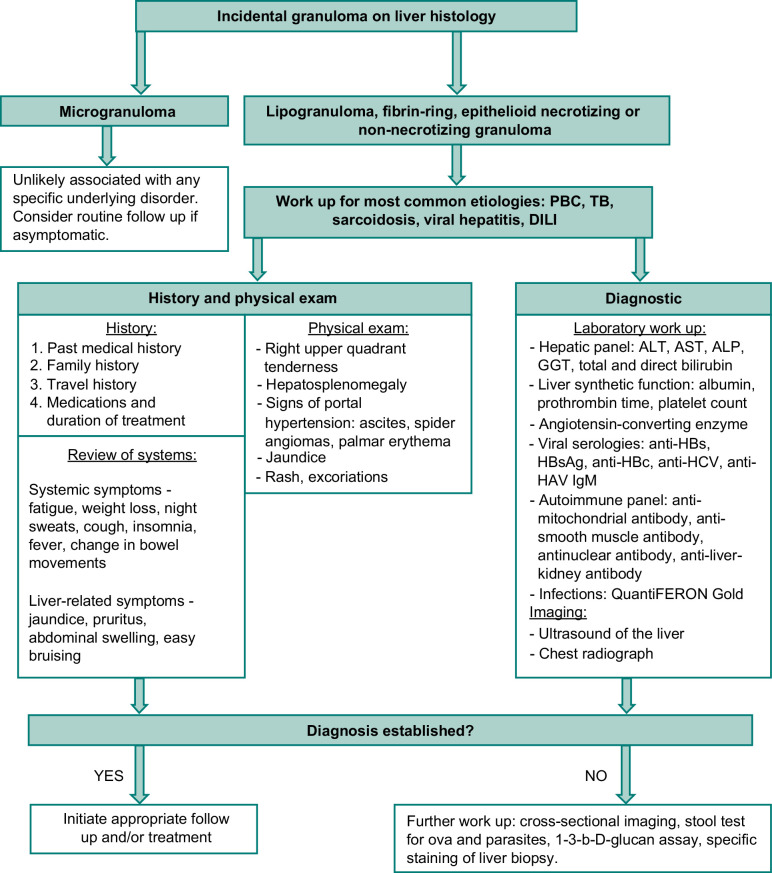

DIAGNOSIS

Unexplained biochemical liver abnormalities or unexplained systemic symptoms are the 2 commonest scenarios leading to the suspicion of GLD. Liver histology is required for diagnosis, in combination with thorough history taking, physical exam, concurrent laboratory tests, and imaging techniques (Figure 3). Travel history or being born in endemic regions for parasitic infections or TB, family or personal history of autoimmune disease or immunodeficiency, temporal association with medication use—all of these may hint at certain types of GLD. Most common etiologies, such as sarcoidosis or TB should be considered first. The presentation usually depends on the underlying etiology, but the diagnosis may be challenging because of the nonspecificity of the symptoms. Some patients may be asymptomatic, while others may exhibit fatigue, abdominal pain, fever, and pruritus, which are seen in both noninfectious and infectious etiologies.128,144

FIGURE 3.

Workup of incidental granuloma on the liver biopsy. Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; TB, tuberculosis.

Although there is no specific pattern of liver enzyme abnormalities in GLD, a cholestatic picture with elevation in alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) is the most common, followed by a mixed pattern characterized by elevation of alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, as well serum aminotransferases. In hepatic sarcoidosis, most patients have either a cholestatic or a mixed picture of liver enzyme abnormalities.145 Similar trends are observed in DILI;39 however, in ICI-related granulomatous hepatitis equal numbers of patients had either cholestatic or hepatocellular injury.125 Liver enzyme elevation in hepatic sarcoidosis may correlate with the severity of granulomatous inflammation and the degree of fibrosis.145 Disease-specific tests may point toward certain etiologies: angiotensin-converting enzyme elevation in sarcoidosis, 1,3-β-D-glucan levels, blood/biopsy cultures in fungal infection, viral serologies in viral infections, and autoimmune panel in PBC.

Imaging augments the laboratory workup in the diagnosis of GLD. Cross-sectional methods such as computerized tomography (CT) or MRI are helpful in the evaluation of hepatic lesions and the complications of portal hypertension. While many GLDs present with nonspecific findings, such as increased liver echogenicity on ultrasound, or liver nodularity on cross-sectional imaging, some have pathognomonic features. The presence of calcified septa perpendicular to the capsule on CT in a “turtleback” pattern is a distinct feature of schistosomiasis, which becomes more prominent as the disease advances. In a study by Araki et al, calcifications on CT correlated with the degree of fibrosis in schistosomiasis; calcifications were also found in those who developed HCC.146 In schistosomiasis, ultrasound is useful to assess the degree of periportal fibrosis and to monitor the response to treatment.147 Healed mycobacterial or fungal granulomas may also present as calcifications on CT.148 The contrast-enhanced ultrasound is useful in the diagnosis of infectious granulomas: 93% of lesions present as hypoechoic and irregular in shape, and 60% demonstrate hyperenhancement in the arterial phase.149 Granulomas can exhibit increased metabolic activity mimicking metastasis on the positron-emission tomography CT.150,151

TREATMENT AND FOLLOW-UP

Treatment is guided by the underlying disorder and its severity. Hepatic granulomas in infections should be treated with appropriate antimicrobial, antifungal, antiviral, or antiprotozoal medications. Patients with hepatic TB demonstrate excellent response to anti-TB drug regimens: in a study by Liu et al, all 25 patients who completed treatment had resolution of lesions on the CT and improvement in symptoms.128 In the case of DILI, the offending medication should be withheld; rechallenge is offered if clinically necessary and only after normalization of liver function. Patients with hepatitis due to DILI may be treated with steroids and ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA).110,125,152 UDCA is a first-line therapy for PBC, and it has been shown to improve transplant-free survival.153 Asymptomatic patients with hepatic sarcoidosis often do not require treatment and the disease may be self-limiting. If cholestatic liver disease or signs of PH develop, prompt treatment with steroids, UDCA, antimetabolites, or anti-TNF medications is indicated.53,117 In the study by Graf et al, patients with hepatic sarcoidosis demonstrated similar biochemical responses to both steroids and UDCA.144

In patients with an incidental finding of granulomas on biopsy, periodic monitoring of liver enzymes and synthetic function every 6–12 months is reasonable. Patients with chronic forms of GLD should be approached as any other patient with chronic liver disease including appropriate vaccination and screening. If the patient progresses to cirrhosis, noninvasive tests to evaluate for PH and imaging every 6 months to screen for HCC are indicated. A liver transplant should be considered in case of decompensated liver disease. Disease recurrence in the transplanted liver is reported in CVID, sarcoidosis, and PBC.102,154,155 There is not enough evidence to link the presence of TB granulomas in the pretransplant with the development of TB in the posttransplant period.156 Patients with inborn errors of immunity should be considered for hematopoietic stem cell transplant before liver disease progresses.107

CONCLUSION

Granulomas are commonly found in histological liver specimens. A systematic approach allows for accurate diagnosis and management. The ability to identify histological features, distinguish between granuloma types, and understand the manifestations of GLD and common etiologies of GLD are crucial for proper diagnosis and intervention. GLD is often a part of a systemic process; timely initiation of treatment is essential for the prevention of associated morbidity and mortality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Nancy Terry from the NIH Library for helping them in the literature search for the review article and Alan Hoofring from the NIH Medical Arts Design Section for the artwork.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BCG, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin; CGD, chronic granulomatous disease; CT, computerized tomography; CVID, common variable immunodeficiency; FUO, fever of unknown origin; GLD, granulomatous liver diseases; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitors; NCPH, noncirrhotic portal hypertension; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; PH, portal hypertension; TB, tuberculosis; Th1, T helper type 1; Th2, T helper type 2; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; US, ultrasound.

Contributor Information

Maria Mironova, Email: maria.mironova@nih.gov.

Harish Gopalakrishna, Email: harishkumar.gopalakrishnapillai@nih.gov.

Gian Rodriguez Franco, Email: gian.rodriguezfranco@nih.gov.

Steven M. Holland, Email: SHOLLAND@niaid.nih.gov.

Christopher Koh, Email: christopher.koh@nih.gov.

David E. Kleiner, Email: kleinerd@mail.nih.gov.

Theo Heller, Email: theoh@intra.niddk.nih.gov.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made a substantial contribution to this work. All authors provided approval for the final submitted version of the manuscript. Individual contributions are listed as follows: Maria Mironova —study concept and design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript draft. Harish Gopalakrishna—data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation. Gian Rodriguez Franco—data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation. Steven M. Holland—data acquisition. Christopher Koh—data acquisition. David E. Kleiner—data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation. Theo Heller—study concept and design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript draft.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work is supported by the NIDDK Intramural Research Program.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almadi MA, Aljebreen AM, Sanai FM, Marcus V, Almeghaiseeb ES, Ghosh S. New insights into gastrointestinal and hepatic granulomatous disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:455–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matheus T, Muñoz S. Granulomatous liver disease and cholestasis. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8:229–246; ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sartin JS, Walker RC. Granulomatous hepatitis: A retrospective review of 88 cases at the Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:914–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaikh S, Shaikh RB, Rab SM. Granulomatous hepatitis: Analysis of twenty seven patients. Article. J Coll Phys Surgeons Pak. 1997;7:235–236. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geramizadeh B, Jahangiri R, Moradi E. Causes of hepatic granuloma: A 12-year single center experience from southern Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2011;14:288–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanai FM, Ashraf S, Abdo AA, Satti MB, Batwa F, Al‐Husseini H, et al. Hepatic granuloma: Decreasing trend in a high-incidence area. Liver Int. 2008;28:1402–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dourakis SP, Saramadou R, Alexopoulou A, Kafiri G, Deutsch M, Koskinas J, et al. Hepatic granulomas: A 6-year experience in a single center in Greece. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turhan N, Kurt M, Ozderin YO, Kurt OK. Hepatic granulomas: A clinicopathologic analysis of 86 cases. Pathol Res Pract. 2011;207:359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaspar R, Andrade P, Silva M, Peixoto A, Lopes J, Carneiro F, et al. Hepatic granulomas: A 17-year single tertiary centre experience. Histopathology. 2018;73:240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drebber U, Kasper HU, Ratering J, Wedemeyer I, Schirmacher P, Dienes HP, et al. Hepatic granulomas: Histological and molecular pathological approach to differential diagnosis--a study of 442 cases. Liver Int. 2008;28:828–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaya DR, Thorburn D, Oien KA, Morris AJ, Stanley AJ. Hepatic granulomas: A 10 year single centre experience. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:850–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson CS, Nicholls J, Rowland R, LaBrooy JT. Hepatic granulomas: A 15-year experience in the Royal Adelaide Hospital. Med J Aust. 1988;148:71–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabharwal BD, Malhotra N, Garg R, Malhotra V. Granulomatous hepatitis: A retrospective study. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1995;38:413–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terzic D, Brmbolic B, Singer D, Dupanovic B, Korac M, Selemovic D, et al. Liver enlargement associated with opportunistic infections patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Gastrointest Liver Diss. 2008;17:401–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira GH, Yamagutti DC, Mendonça JS. Evaluation of the histopathological hepatic lesions and opportunistic agents in Brazilian HIV patients. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010;43:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Comer GM, Mukherjee S, Scholes JV, Holness LG, Clain DJ. Liver biopsies in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: Influence of endemic disease and drug abuse. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1525–1531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickey AJ, Gounder L, Moosa MY, Drain PK. A systematic review of hepatic tuberculosis with considerations in human immunodeficiency virus co-infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonderup MW, Wainwright H, Hall P, Hairwadzi H, Spearman CW. A clinicopathological cohort study of liver pathology in 301 patients with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Hepatology. 2015;61:1721–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nussbaum EZ, Patel KK, Assi R, Raad RA, Malinis M, Azar MM. Clinicopathologic features of tissue granulomas in transplant recipients. A single center study in a nontuberculosis endemic region. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021;145:988–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleiner DE. Granulomas in the liver. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2006;23:161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pagan AJ, Ramakrishnan L. The formation and function of granulomas. Annu Rev Immunol. 2018;36:639–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bica I, Hamer DH, Stadecker MJ. Hepatic schistosomiasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2000;14:583–604; viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henri S, Chevillard C, Mergani A, Paris P, Gaudart J, Camilla C, et al. Cytokine regulation of periportal fibrosis in humans infected with Schistosoma mansoni: IFN-gamma is associated with protection against fibrosis and TNF-alpha with aggravation of disease. J Immunol. 2002;169:929–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pereira TA, Borthwick L, Machado M, Teixeira Vidigal P, Voieta I, Resende V, et al. Interleukin-13 activated hedgehog signaling regulates pathogen driven inflammation and fibrosis. Conference Abstract. Hepatology. 2017;66:234A. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:86–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carson JP, Ramm GA, Robinson MW, McManus DP, Gobert GN. Schistosome-induced fibrotic disease: The role of hepatic stellate cells. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34:524–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marakalala MJ, Raju RM, Sharma K, Zhang YJ, Eugenin EA, Prideaux B, et al. Inflammatory signaling in human tuberculosis granulomas is spatially organized. Nat Med. 2016;22:531–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossman MD, Thompson B, Frederick M, Maliarik M, Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, et al. HLA-DRB1*1101: A significant risk factor for sarcoidosis in blacks and whites. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:720–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valentonyte R, Hampe J, Huse K, Rosenstiel P, Albrecht M, Stenzel A, et al. Sarcoidosis is associated with a truncating splice site mutation in BTNL2. Nat Genet. 2005;37:357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abolhassani H, Hammarstrom L, Cunningham-Rundles C. Current genetic landscape in common variable immune deficiency. Blood. 2020;135:656–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abolhassani H, Wang N, Aghamohammadi A, Rezaei N, Lee YN, Frugoni F, et al. A hypomorphic recombination-activating gene 1 (RAG1) mutation resulting in a phenotype resembling common variable immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1375–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denk H, Scheuer PJ, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, Groote JD, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and interpretation of hepatic granulomas. Histopathology. 1994;25:209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamps LW. Hepatic granulomas, with an emphasis on infectious causes. Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15:309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dincsoy HP, Weesner RE, MacGee J. Lipogranulomas in non-fatty human livers. A mineral oil induced environmental disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1982;78:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakano M, Fukusato T. Histological study on comparison between NASH and ALD. Hepatol Res. 2005;33:110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathologic patterns and biopsy evaluation in clinical research. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Carpenter DH, Rinella M, Harrison SA, Loomba R, et al. NAFLD: Reporting histologic findings in clinical practice. Hepatology. 2021;73:2028–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu H, Bodenheimer HC, Jr., Clain DJ, Min AD, Theise ND. Hepatic lipogranulomas in patients with chronic liver disease: Association with hepatitis C and fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5065–5069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kleiner DE, Chalasani NP, Lee WM, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, et al. Hepatic histological findings in suspected drug-induced liver injury: Systematic evaluation and clinical associations. Hepatology. 2014;59:661–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernstein M, Edmondson HA, Barbour BH. The liver lesion in Q fever. Clinical and pathologic features. Arch Intern Med. 1965;116:491–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marazuela M, Moreno A, Yebra M, Cerezo E, Gómez-Gesto C, Vargas JA. Hepatic fibrin-ring granulomas: A clinicopathologic study of 23 patients. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:607–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy E, Griffiths MR, Hunter JA, Burt AD. Fibrin-ring granulomas: A non-specific reaction to liver injury? Histopathology. 1991;19:91–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Bayser L, Roblot P, Ramassamy A, Silvain C, Levillain P, Becq-Giraudon B. Hepatic fibrin-ring granulomas in giant cell arteritis. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:272–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Everett J, Srivastava A, Misdraji J. Fibrin ring granulomas in checkpoint inhibitor-induced hepatitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:134–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Martin E, Michot JM, Papouin B, Champiat S, Mateus C, Lambotte O, et al. Characterization of liver injury induced by cancer immunotherapy using immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Hepatol. 2018;68:1181–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi EK, Lamps LW. Granulomas in the liver, with a focus on infectious causes. Surg Pathol Clin. 2018;11:231–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh S, Verma Y, Pandey P, Singh UB. Granulomatous hepatitis by Nocardia species: An unusual case. Article Internat J Infect Dis. 2019;81:97–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hassan HA, Majid RA, Rashid NG, Nuradeen BE, Abdulkarim QH, Hawramy TA, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatous gastrointestinal and hepatic abscesses attributable to basidiobolomycosis and fasciolias: A simultaneous emergence in Iraqi Kurdistan. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Björnsson E, Olsson R, Remotti H. Norfloxacin-induced eosinophilic necrotizing granulomatous hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3662–3664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saw D, Pitman E, Maung M, Savasatit P, Wasserman D, Yeung CK. Granulomatous hepatitis associated with glyburide. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:322–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okuno T, Arai K, Matsumoto M, Shindo M. Epithelioid granulomas in chronic hepatitis C: A transient pathological feature. Article J Gastroenterol Hepatol (Australia). 1995;10:532–537. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rais R, Chatterjee D, McHenry S, Byrnes K. Poorly formed hepatic granulomas: A rare manifestation of acute T cell-mediated rejection. Histopathology. 2020;77:847–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sollors J, Schlevogt B, Schmidt HJ, Woerns MA, Galle PR, Qian Y, et al. Management of hepatic sarcoidosis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2022;31:323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cabas P, Rizzo M, Giuffrè M, Antonello RM, Trombetta C, Luzzati R, et al. BCG infection (BCGitis) following intravesical instillation for bladder cancer and time interval between treatment and presentation: A systematic review. Urol Oncol. 2021;39:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guillevin L, Ronco P, Verroust P. Circulating immune complexes in systemic necrotizing vasculitis of the polyarteritis nodosa group. Comparison of HBV-related polyarteritis nodosa and Churg Strauss Angiitis. J Autoimmun. 1990;3:789–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cervantes F, Bruguera M, Carbonell J, Force L, Webb S. Liver disease in brucellosis. A clinical and pathological study of 40 cases. Postgrad Med J. 1982;58:346–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee S, Childerhouse A, Moss K. Gastrointestinal symptoms and granulomatous vasculitis involving the liver in giant cell arteritis: A case report and review of the literature. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:2316–2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holl-Ulrich K, Klass M. Wegener s granulomatosis with granulomatous liver involvement. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(1 Suppl 57):88–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malatack JJ, Jaffe R. Granulomatous hepatitis in three children due to cat-scratch disease without peripheral adenopathy: An unrecognized cause of fever of unknown origin. Article. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:949–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eade MN, Cooke WT, Williams JA. Liver disease in Crohn’s disease. A study of 100 consecutive patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1971;6:199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Malvar G, Cardona D, Pezhouh MK, Adeyi OA, Chatterjee D, Deisch JK, et al. Hepatic secondary syphilis can cause a variety of histologic patterns and may be negative for treponeme immunohistochemistry. Am J Surg Pathol. 2022;46:567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chatzipantelis P, Giatromanolaki A. Early histopathologic changes in primary biliary cholangitis: does ‘minimal change’ primary biliary cholangitis exist? A pathologist’s view. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;33:e7–e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mongiardo N, De Rienzo B, Zanchetta G, Lami G, Pellegrino F, Squadrini F. Primary hepatic actinomycosis. J Infect. 1986;12:65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ho HE, Cunningham-Rundles C. Non-infectious complications of common variable immunodeficiency: Updated clinical spectrum, sequelae, and insights to pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lamps LW, Molina CP, West AB, Haggitt RC, Scott MA. The pathologic spectrum of gastrointestinal and hepatic histoplasmosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang AH, Sullivan B, Zerbe CS, De Ravin SS, Blakely AM, Quezado MM, et al. Gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of chronic granulomatous disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11:1401–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dancygier H. Bacterial liver abscess and other bacterial infections. clinical hepatology, Vol 2: Principles and practice of hepatobiliary. Diseases. 2010:831–842. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Howard PF, Smith JW. Diagnosis of disseminated coccidioidomycosis by liver biopsy. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1335–1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rammaert B, Desjardins A, Lortholary O. New insights into hepatosplenic candidosis, a manifestation of chronic disseminated candidosis. Mycoses. 2012;55:e74–e84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lindgren A, Aldenborg F, Norkrans G, Olaison L, Olsson R. Paracetamol-induced cholestatic and granulomatous liver injuries. J Intern Med. 1997;241:435–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iqbal U, Siddiqui HU, Anwar H, Chaudhary A, Quadri AA. Allopurinol-Induced granulomatous hepatitis: A case report and review of literature. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2017;5:2324709617728302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamamoto T, Ishii M, Nagura H, Miyazaki Y, Miura M, Igarashi T, et al. Transient hepatic fibrin-ring granulomas in a patient with acute hepatitis A. Liver. 1995;15:276–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marin Zuluaga JI, Marin Castro AE, Perez Cadavid JC, Restrepo Gutierrez JC. Albendazole-induced granulomatous hepatitis: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nenert M, Mavier P, Dubuc N, Deforges L, Zafrani ES. Epstein-Barr virus infection and hepatic fibrin-ring granulomas. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:608–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aggarwal A, Jaswal N, Jain R, Elsiesy H. Amoxicillin-clavulanate-induced granulomatous hepatitis: Case report and review of the literature. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2019;7:280–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Da Cunha T, Wu GY. Cytomegalovirus hepatitis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2021;9:106–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sarachek NS, London RL, Matulewicz TJ. Diltiazem and granulomatous hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1985;88(5 Pt 1):1260–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peixoto A, Martins Rocha T, Santos-Antunes J, Aguiar F, Bernardes M, Vaz C, et al. Etanercept-induced granulomatous hepatitis as a rare cause of abnormal liver tests. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2019;82:93–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Almeida DE, Costa E, Neves JS, Cerqueira M, Ribeiro AR. Cutaneous vasculitis and granulomatous hepatitis as paradoxical adverse events of Infliximab. Acta Reumatol Port. 2020;45:156–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kakihara D, Yoshimitsu K, Ishigami K, Irie H, Aibe H, Tajima T, et al. Liver lesions of visceral larva migrans due to Ascaris suum infection: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zen Y, Chen YY, Jeng YM, Tsai HW, Yeh MM. Immune-related adverse reactions in the hepatobiliary system: Second-generation check-point inhibitors highlight diverse histological changes. Histopathology. 2020;76:470–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Acosta-Ferreira W, Vercelli-Retta J, Falconi LM. Fasciola hepatica human infection. Histopathological study of sixteen cases. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1979;383:319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Colle I, Naegels S, Hoorens A, Hautekeete M. Granulomatous hepatitis due to mebendazole. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:44–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Braun M, Fraser GM, Kunin M, Salamon F, Tur-Kaspa R. Mesalamine-induced granulomatous hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1973–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weitberg AB, Alper JC, Diamond I, Fligiel Z. Acute granulomatous hepatitis in the course of acquired toxoplasmosis. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1093–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Spengler EK, Kleiner DE, Fontana RJ. Vemurafenib-induced granulomatous hepatitis. Hepatology. 2017;65:745–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moreno A, Marazuela M, Yebra M, Hernández MJ, Hellín T, Montalbán C, et al. Hepatic fibrin-ring granulomas in visceral leishmaniasis. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1123–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dhawan M, Agrawal R, Ravi J, Gulati S, Silverman J, Nathan G, et al. Rosiglitazone-induced granulomatous hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:582–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Namias A, Bhalotra R, Donowitz M. Reversible sulfasalazine-induced granulomatous hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1981;3:193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eybel CE. Induction of granulomatous hepatitis by quinidine. J Cardiovasc Med. 1980;5:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bergter W, Fetzer IC, Sattler B, Ramadori G. Granulomatous hepatitis preceding hodgkin’s disease (Case-Report and Review on Differential Diagnosis). Pathol Oncol Res. 1996;2:177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ojha S, Gall T, Sodergren MH, Jiao LR. A case of gossypiboma mimicking intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:e14–e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim SW, Shin HC, Kim IY, Baek MJ, Cho HD. Foreign body granulomas simulating recurrent tumors in patients following colorectal surgery for carcinoma: A report of two cases. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:313–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Urban RM, Jacobs JJ, Tomlinson MJ, Gavrilovic J, Black J, Peoc’h M. Dissemination of wear particles to the liver, spleen, and abdominal lymph nodes of patients with hip or knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:457–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hudacko R, Anand K, Gordon R, John T, Catalano C, Zaldana F, et al. Hepatic silicone granulomas secondary to ruptured breast implants: A report of two cases. Case Reports Hepatol. 2019;2019:7348168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Esteves T, Aparicio G, Garcia-Patos V. Is there any association between Sarcoidosis and infectious agents?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16:165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ungprasert P, Crowson CS, Simonetto DA, Matteson EL. Clinical characteristics and outcome of hepatic sarcoidosis: A population-based study 1976-2013. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1556–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mañá J, Rubio-Rivas M, Villalba N, Marcoval J, Iriarte A, Molina-Molina M, et al. Multidisciplinary approach and long-term follow-up in a series of 640 consecutive patients with sarcoidosis: Cohort study of a 40-year clinical experience at a tertiary referral center in Barcelona, Spain. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e7595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Blich M, Edoute Y. Clinical manifestations of sarcoid liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:732–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Devaney K, Goodman ZD, Epstein MS, Zimmerman HJ, Ishak KG. Hepatic sarcoidosis. Clinicopathologic features in 100 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:1272–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kennedy PTF, Zakaria N, Modawi SB, Papadopoulou AM, Murray-Lyon I, du Bois RM, et al. Natural history of hepatic sarcoidosis and its response to treatment. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:721–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fauter M, Rossi G, Drissi-Bakhkhat A, Latournerie M, Gerfaud-Valentin M, Durieu I, et al. Hepatic sarcoidosis with symptomatic portal hypertension: A report of 12 cases with review of the literature. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:995042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yardeni D, Hercun J, Rodriguez GV, Fontana JR, Kleiner DE, Koh C, et al. Reversal of clinically significant portal hypertension after immunosuppressive treatment in a patient with sarcoidosis. ACG Case Rep J. 2022;9:e00874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Scheuer PJ. Primary biliary cirrhosis: Diagnosis, pathology and pathogenesis. Postgrad Med J. 1983;59(Suppl 4):106–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.You Z, Wang Q, Bian Z, Liu Y, Han X, Peng Y, et al. The immunopathology of liver granulomas in primary biliary cirrhosis. J Autoimmun. 2012;39:216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lee RG, Epstein O, Jauregui H, Sherlock S, Scheuer PJ. Granulomas in primary biliary cirrhosis: A prognostic feature. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:983–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sharma D, Ben Yakov G, Kapuria D, et al. Tip of the iceberg: A comprehensive review of liver disease in Inborn errors of immunity. Hepatology. 2022;76:1845–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Resnick ES, Moshier EL, Godbold JH, Cunningham-Rundles C. Morbidity and mortality in common variable immune deficiency over 4 decades. Blood. 2012;119:1650–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ardeniz O, Cunningham-Rundles C. Granulomatous disease in common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Immunol. 2009;133:198–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Malamut G, Ziol M, Suarez F, Beaugrand M, Viallard JF, Lascaux AS, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia: The main liver disease in patients with primary hypogammaglobulinemia and hepatic abnormalities. J Hepatol. 2008;48:74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hussain N, Feld JJ, Kleiner DE, Hoofnagle JH, Garcia-Eulate R, Ahlawat S, et al. Hepatic abnormalities in patients with chronic granulomatous disease. Hepatology. 2007;45:675–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Feld JJ, Hussain N, Wright EC, Kleiner DE, Hoofnagle JH, Ahlawat S, et al. Hepatic involvement and portal hypertension predict mortality in chronic granulomatous disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1917–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mendes FD, Levy C, Enders FB, Loftus EV, Jr., Angulo P, Lindor KD. Abnormal hepatic biochemistries in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.McCluggage WG, Sloan JM. Hepatic granulomas in Northern Ireland: A thirteen year review. Histopathology. 1994;25:219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ishak KG, Zimmerman HJ. Drug-induced and toxic granulomatous hepatitis. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1988;2:463–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Farah M, Al Rashidi A, Owen DA, Yoshida EM, Reid GD. Granulomatous hepatitis associated with etanercept therapy. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:349–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sebode M, Weidemann S, Wehmeyer M, Lohse AW, Schramm C. Anti-TNF-α for necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis of the liver. Hepatology. 2017;65:1410–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kapoor SR, Snowden N. The use of infliximab in a patient with idiopathic granulomatous hepatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kubota E, Katano M, Katsuki T, et al. Granumolatous hepatitis as a late complication of BCG immunotherapy for stage III malignant melanoma patient. Report of a case. Article. J Japan Soc Cancer Therapy. 1995;30:791–798. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Freundlich E, Suprun H. Tuberculoid granulomata in the liver after BCG vaccination. Isr J Med Sci. 1969;5:108–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Desmet M, Moubax K, Haerens M. Multiple organ failure and granulomatous hepatitis following intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin instillation. Acta Clin Belg. 2012;67:367–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kerner G, Rosain J, Guérin A, Al-Khabaz A, Oleaga-Quintas C, Rapaport F, et al. Inherited human IFN-gamma deficiency underlies mycobacterial disease. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:3158–3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chavez-Galan L, Vesin D, Blaser G, Uysal H, Benmerzoug S, Rose S, et al. Myeloid cell TNFR1 signaling dependent liver injury and inflammation upon BCG. Sci Rep. 2019;9:95297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ávila F, Santos V, Massinha P, Pereira JR, Quintanilha R, Figueiredo A, et al. Hepatic actinomycosis. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2015;22:19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hountondji L, Ferreira De Matos C, Lebossé F, Quantin X, Lesage C, Palassin P, et al. Clinical pattern of checkpoint inhibitor-induced liver injury in a multicentre cohort. JHEP Rep. 2023;5:100719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kondo Y, Akahira J, Morosawa T, Toi Y, Endo A, Satio H, et al. Anti-nuclear antibody and a granuloma could be biomarkers for iCIs-related hepatitis by anti-PD-1 treatment. Sci Rep. 2022;12:3669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Bagcchi S. WHO’s Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. Lancet Microbe. 2023;4:e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Saiduo S, Wei W, Jichan J, Xinchun, Hongye, Ning, et al. Clinical manifestation, imaging features and treatment follow-up of 29 cases with hepatic tubercolosis. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2022;14:e2022063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Otoukesh S, Shahsafi MR, Poorabdollah M, Mojtahedzadeh M, Rahvari SK, Sajadi MM, et al. Case report: portal hypertension secondary to isolated liver tuberculosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:162–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Li T, Wang J, Yang Y, Wang P, Zhou G, Liao C, et al. Evaluation of Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in Southwest China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17:e0011403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pellegrin M, Delsol G, Auvergnat JC, Familiades J, Faure H, Guiu M, et al. Granulomatous hepatitis in Q fever. Hum Pathol. 1980;11:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.De Keukeleire S, Geldof J, De Clerck F, Vandecasteele S, Reynders M, Orlent H. Prolonged course of hepatic granulomatous disease due to Bartonella henselae infection. Article. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2016;79:497–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ha HK, Lee HJ, Kim H, Ro HJ, Park YH, Cha SJ, et al. Abdominal actinomycosis: CT findings in 10 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161:791–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Propst A, Propst T, Dietze O, Kathrein H, Judmeier G, Vogel W. Development of granulomatous hepatitis during treatment with interferon-α(2b) [1]. Letter Diges Dis Sci. 1995;40:2117–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wang Y, Liu S, Liu H, Li W, Lin F, Jiang L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection of the liver directly contributes to hepatic impairment in patients with COVID-19. J Hepatol. 2020;73:807–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lewis JH, Patel HR, Zimmerman HJ. The spectrum of hepatic candidiasis. Hepatology. 1982;2:479–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Strauss E, Valla D. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension--concept, diagnosis and clinical management. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014;38:564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Liu XF, Li Y, Ju S, Zhou YL, Qiang JW. Network analysis and nomogram in the novel classification and prognosis prediction of advanced schistosomiasis japonica. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023;108:569–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Roberts-Thomson IC, Anders RF, Bhathal PS. Granulomatous hepatitis and cholangitis associated with giardiasis. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:480–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Khanlari B, Bodmer M, Terracciano L, Heim MH, Fluckiger U, Weisser M. Hepatitis with fibrin-ring granulomas. Infection. 2008;36:381–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Simon HB, Wolff SM. Granulomatous hepatitis and prolonged fever of unknown origin: A study of 13 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1973;52:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Holtz T, Moseley RH, Scheiman JM. Liver-biopsy in fever of unknown origin - A reappraisal. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;17:29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zoutman DE, Ralph ED, Frei JV. Granulomatous hepatitis and fever of unknown origin. An 11-year experience of 23 cases with three years’ follow-up. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Graf C, Arncken J, Lange CM, Willuweit K, Schattenberg JM, Seessle J, et al. Hepatic sarcoidosis: Clinical characteristics and outcome. Jhep Reports. 2021;3:100360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Cremers J, Drent M, Driessen A, Nieman F, Wijnen P, Baughman R, et al. Liver-test abnormalities in sarcoidosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Araki T, Hayakawa K, Okada J, Hayashi S, Uchiyama G, Yamada K. Hepatic schistosomiasis japonica identified by CT. Radiology. 1985;157:757–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Araújo I, Miranda RG, De Jesus AR, Carvalho EM, Bacellar M, Miranda DG, et al. Morbidity associated with Schistosoma mansoni infection determined by ultrasound in an endemic area of Brazil, Caatinga do Moura. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Alvarez SZ. Hepatobiliary tuberculosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Liu GJ, Lu MD, Xie XY, Xu HX, Xu ZF, Zheng YL, et al. Real-time contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging of infected focal liver lesions. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Li T, Fan M, Shui R, Hu S, Zhang Y, Hu X. Pathology-confirmed granuloma mimicking liver metastasis of breast cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2014;29:e93–e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Sarathy V, Kothandath Shankar RK, Mufti SS, Naik R. FOLFOX and capecitabine-induced hepatic granuloma mimicking metastasis in a rectal cancer patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:e232628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Wree A, Dechêne A, Herzer K, Hilgard P, Syn WK, Gerken G, et al. Steroid and ursodesoxycholic Acid combination therapy in severe drug-induced liver injury. Digestion. 2011;84:54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Lammers WJ, van Buuren HR, Hirschfield GM, Janssen HLA, Invernizzi P, Mason AL, et al. Levels of alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin are surrogate end points of outcomes of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis: An international follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1338–49 e5; quiz e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Lipson EJ, Fiel MI, Florman SS, Korenblat KM. Patient and graft outcomes following liver transplantation for sarcoidosis. Clin Transplant. 2005;19:487–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Ferrell LD, Lee R, Brixko C, Bass NM, Lake JR, Roberts JP, et al. Hepatic granulomas following liver transplantation. Clinicopathologic features in 42 patients. Transplantation. 1995;60:926–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Olithselvan A, Rajagopala S, Vij M, Shanmugam V, Shanmugam N, Rela M. Tuberculosis in liver transplant recipients: experience of a South Indian liver transplant center. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:960–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]