Abstract

Key Clinical Message

To raise awareness about the increasing incidence of superfetation and heterotopic pregnancy in patients with ovarian induction, their insidious symptoms of abdominal pain, anemia, and hemodynamic instability in early pregnancy, and the usefulness of transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) and quantitative beta human chorionic gonadotrophin (b‐hCG) for diagnosis.

Abstract

Superfetation, occurrence of ovulation, fertilization, and implantation during an ongoing pregnancy and heterotopic pregnancy (HP) simultaneous presence of intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancies are infrequent phenomena. We report a case where both coexisted, challenges in diagnosis and management and association with the widespread use of assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs). A 32‐year‐old woman, who previously underwent ovulation induction therapy, presented with abdominal pain at 8 weeks pregnancy according to her last menstrual period. The patient had high quantitative serum beta‐human chorionic gonadotropin (b‐hCG) (30,883 mIU/mL). She was vitally stable and not anemic. Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) revealed two pregnancies at different gestational ages: an intrauterine pregnancy at 5 weeks and 3 days, and a right intact tubal ectopic pregnancy at 10 weeks and 5 days. Superfetation resulting in HP was then diagnosed. Subsequently, the patient underwent right laparoscopic salpingectomy. The intrauterine pregnancy progressed normally, resulting in delivery of a healthy full‐term neonate via Cesarean section at 38 weeks. Superfetation is typically rare from suppression of follicular development and ovulation during pregnancy. Various theories have been proposed to explain its etiology, including polyovulation, delayed blastocyst implantation, and abnormal estrogen and b‐hCG surges. In superfetation, an embryo resulting from a previous conception coexists with another embryo, either intrauterine, resulting in diamniotic dizygotic twins with significantly different gestational ages, or extrauterine resulting in HP. Despite being particularly challenging to diagnose because its presenting symptoms can overlap with those of other more common clinical conditions in early pregnancy, HP is increasingly seen with ARTs. In addition, the treatment of HP is versatile, ranging from expectant management to laparoscopic surgery. High level of suspicion for HP and superfetation is crucial in patients who, after ART, present with abdominal pain, hemodynamic instability, or anemia. Additionally, patients planning to undergo subsequent ART cycles should be thoroughly screened with b‐hCG and TVUS to exclude an ongoing intrauterine or extrauterine pregnancy.

Keywords: assisted reproductive technologies (ART), case report, heterotopic pregnancy (HP), superfetation, tubal ectopic pregnancy

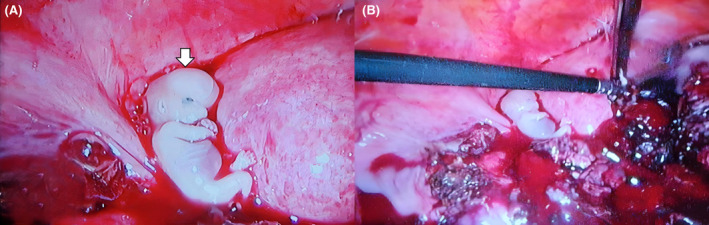

A close‐up (A) and a wider angle (B) view of the operative field during laparoscopic salpingectomy. The procedure aims to remove a right intact heterotopic tubal pregnancy, which is coexisting with an intrauterine pregnancy of differing gestational ages. This case involves a woman who underwent ovulation induction using both oral clomiphene citrate tablets and injectable recombinant human FSH.

1. INTRODUCTION

Superfetation is an exceedingly rare occurrence in which ovulation, fertilization, and implantation take place after a fetus is already present as a product of previous conception. Until 2008, there were fewer than 10 documented cases of this phenomenon. 1 However, since then, new reports have surfaced, most recently one involving a UK woman in 2021. 2 Heterotopic pregnancy (HP) is the simultaneous presence of at least two pregnancies in different implantation sites. Despite being rare in spontaneous pregnancies, HP is increasingly encountered in pregnancies achieved by assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs). 3

We present the case of a woman who came complaining of abdominal pain at 8 weeks of pregnancy after ovarian induction and was found to have a higher‐than‐expected b‐hCG and coexisting intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancies with significantly different gestational ages on TVUS. This case adds to the literature on superfetation and HP, underscores the rising incidence of these rare, and thus overlooked phenomena in the era of ARTs, including ovarian induction, and sheds light on hurdles in diagnosis and management that must be met accordingly.

2. CASE HISTORY/EXAMINATION

A 32‐year‐old female patient, gravida 6, para 1, aborta 4 (G6P1A4), presented to our emergency care unit with abdominal pain that persisted for 3 days. The patient's abdominal pain was rated as “moderate” with a four‐category verbal rating scale describing pain as nonexistent, mild, moderate, or severe. She was 8 weeks pregnant based on her last menstrual period. The patient has been married for 11 years and has only one living child, a 6‐year‐old girl. Prior to the current presentation, the patient underwent multiple cycles of ovulation induction therapy using both clomiphene citrate tablets and injectable recombinant human FSH medications. She had a surgical history of a previous Cesarean section for the delivery of her one live child and three evacuation and curettage procedures for previous first‐trimester abortions, with otherwise unremarkable medical history.

3. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS, INVESTIGATIONS, AND TREATMENT

At the time of evaluation, the patient was hemodynamically stable, with a blood pressure of 120/70 mmHg and a pulse rate of 80 bpm. Lab investigations revealed hemoglobin levels within the normal range (11.4 g/dL) and high quantitative serum b‐hCG level (30,883 mIU/mL). TVUS was immediately performed, showing an enlarged anteverted anteflexed (AVF) uterus containing two gestational sacs. The first sac was empty, while the second contained a pulsating fetal pole with a Crown Rump Length (CRL) corresponding to a gestational age of 5 weeks and 3 days. (Figure 1) Additionally, a right intact tubal ectopic pregnancy was observed, with a gestational sac containing another pulsating fetal pole, this time with a CRL corresponding to 10 weeks and 5 days, along with minimal pelvic collection. (Figure 2) Given the marked difference in gestational age between the right tubal ectopic pregnancy (10 weeks and 5 days) and the intrauterine pregnancy (5 weeks and 3 days) and the higher‐than‐expected serum quantitative b‐hCG for the 5‐week intrauterine pregnancy, a diagnosis of possible superfetation of an intrauterine pregnancy on top of a preexisting extrauterine one resulting in HP was made. The patient's blood type was O positive and cross‐matched blood was prepared in case an emergency blood transfusion became necessary or if hemodynamic instability ensued.

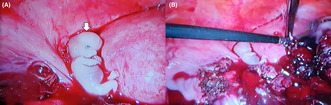

FIGURE 1.

Transvaginal ultrasound shows an enlarged anteverted anteflexed (AVF) uterus containing two gestational sacs. The first sac (asterisk) was empty, while the second contained a pulsating fetal pole (arrow) with a Crown Rump Length (CRL) corresponding to a gestational age of 5 weeks and 3 days.

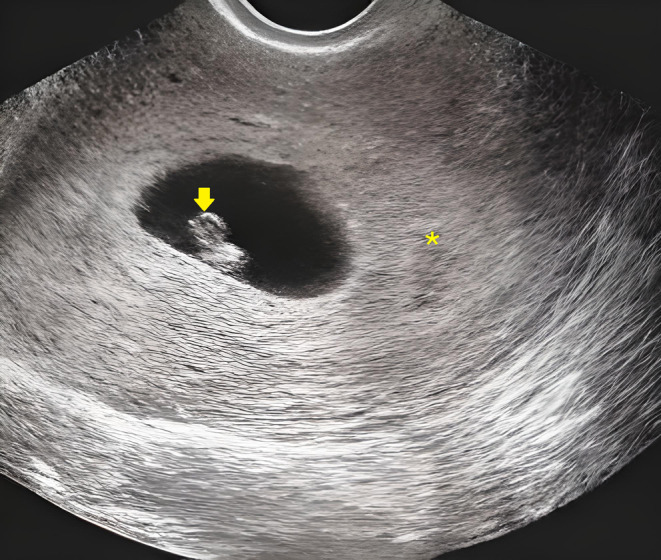

FIGURE 2.

Transvaginal ultrasound shows right intact tubal ectopic pregnancy, with a gestational sac containing another pulsating fetal pole (arrow). The fetal pole had a Crown Rump Length (CRL) corresponding to gestational age of 10 weeks and 5 days. Minimal pelvic collection was also observed.

4. OUTCOME AND FOLLOW‐UP

Subsequently, the patient underwent a right laparoscopic salpingectomy, with particular attention given to minimizing uterine manipulation to preserve the intrauterine pregnancy. (Figure 3) Her postoperative recovery was uneventful, including hemoglobin within the normal range (10.7 g/dL). The intrauterine pregnancy progressed normally, resulting in the delivery of a healthy full‐term neonate via Cesarean section at a gestational age of 38 weeks.

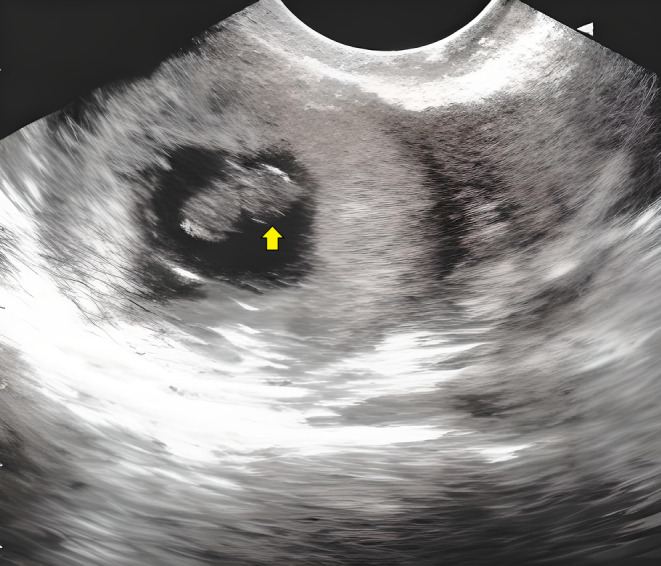

FIGURE 3.

An up‐close (A) and a wider angle (B) view of the operative field during laparoscopic salpingectomy. Laparoscopic salpingectomy was performed to remove intact right tubal pregnancy (arrow). Care was taken to perform as little uterine manipulation as possible to preserve the intrauterine pregnancy.

5. DISCUSSION

Marked by ovulation, fertilization, and implantation during an existing pregnancy, superfetation is an extremely rare phenomenon. A thorough review conducted by Pape et al. in 2008 identified fewer than 10 reported cases. 1 Subsequent reports have been published, including a case in 2010 by Lantieri et al., 4 another in 2019 by Ito et al., 5 and three in 2021: one by Alten et al., 6 one by Windaro et al., 7 and the latest by Segal et al. 2 Of these reports, three cases, ours being the fourth, report superfetation resulting in HP. 4 , 5 , 7

Superfetation is an uncommon occurrence due to the usual suppression of follicular development, halting of ovulation, and subsequently amenorrhea during pregnancy. Various theories have been proposed to elucidate this intriguing condition. One hypothesis suggests that, in the mid‐luteal phase following the ovulation that led to the initial pregnancy, an atypical increase in estrogen induces another luteinizing hormone (LH) peak, subsequently triggering secondary ovulation. 8 Another set of theories includes polyovulation followed by delayed implantation of one of the blastocysts, akin to the concept of “hibernation” observed in certain animals, or a genetically abnormal b‐hCG, qualitatively or quantitatively allowing for another ovulation and implantation within an already ongoing pregnancy. 9 Therefore, these hypotheses could clarify the phenomenon in superfetation where two fetuses with varying gestational ages share a single reported date of amenorrhea, likely corresponding to the onset of the initial pregnancy. For instance, our patient noted a single amenorrhea date at 8 weeks, yet TVUS subsequently revealed two fetuses with gestational ages of 10 weeks, 5 days, and 5 weeks, 3 days, respectively. Moreover, her reported LMP may have been inaccurately recorded, potentially influenced by implantation bleeding affecting the determination of pregnancy‐related amenorrhea.

It is crucial to distinguish between superfetation and another closely related term, superfecundation. Superfecundation is characterized by the ovulation, fertilization, and implantation of different ova within the same menstrual cycle. In this condition, fertilization of the two oocytes occurs with different sperms, possibly even from different semen (from different males). 4 This condition typically leads to a diamniotic dizygotic pregnancy with similar gestational ages and consistent development throughout.

In superfetation, an embryo resulting from a previous conception coexists with another embryo, either intrauterine or extrauterine. When superfetation occurs intrauterine atop an existing intrauterine pregnancy, it can result in diamniotic dizygotic twins with notably different gestational ages. 1 , 2 , 6 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 The diagnosis of superfetation, in this case, can be suspected by observing discordance in growth during pregnancy by serial ultrasound scans and excluding usual causes of intrauterine growth retardation, such as chronic vascular or renal diseases, severe anemia, etc. Postdelivery, examining the placenta and cords for abnormalities assessing newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), or utilizing X‐rays to determine bone age, can further support the diagnosis. 6 , 13 Interestingly, superfetation can also occur extrauterine, on top of an already existing extrauterine pregnancy, resulting in two simultaneous ectopic pregnancies (EP) in different extrauterine sites and with significantly different gestational ages, as described in a recent report of a left tubal EP presented 1 month after treatment of right ovarian EP. 7

Another scenario involves the simultaneous occurrence of intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancies, each exhibiting a significant difference in gestational age. This phenomenon arises when superfetation occurs intrauterine on top of an ectopic pregnancy or vice versa. 4 , 5 , 7 , 14 , 15 This coexistence of both intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancies is referred to as HP. 16 HP, a rare phenomenon in spontaneous pregnancies with an incidence of 1 in 30,000, has seen a noteworthy increase in occurrence due to the widespread use of ARTs. In pregnancies achieved through ART, the incidence of HP has escalated to as high as 1%. 3 , 5 , 7 , 15 , 17

The underlying causes for the stark difference in the incidence of HP between spontaneous pregnancies and those achieved through ARTs are multifaceted. Both the underlying conditions that lead individuals to resort to ART, such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), past abdominopelvic surgeries resulting in pelvic adhesions, or tubal disorders like hydrosalpinx, and the techniques employed during ART, including multiple ovulations, ovulation induction, in‐vitro fertilization, embryo transfer, or ovulation hyperstimulation syndrome, are implicated in the development of HP. These etiological factors are also commonly associated with the development of ectopic pregnancy. 3 , 7 , 16 , 17 These risk factors have been suggested to impede the progress of a fertilized ovum through the fallopian tube, thereby hindering its normal intrauterine implantation.

Overall, the diagnosis of HP is challenging due to several factors, including the presence of a falsely reassuring intrauterine pregnancy. 16 Additionally, symptoms associated with HP, such as abdominal pain—often the most frequent presentation 18 —tachycardia, hypovolemia, and anemia are commonly linked with more prevalent conditions encountered in early pregnancy, such as corpus luteum cysts or ruptured hemorrhagic cysts. These conditions can also result in pelvic collections visible on TVUS. Owing to their higher frequency compared to HP, they often impede or postpone the diagnosis of HP. 3 , 14 , 19

Another challenge in diagnosing HP lies in the technical complexities associated with conducting and interpreting both serum quantitative b‐hCG and TVUS. While TVUS is regarded as the gold standard for HP diagnosis, its sensitivity has shown variability when used alone (ranging from 26.3% to 92.4% in some reports), with its effectiveness heavily reliant on the operator's experience. 14 , 17 , 19 In our patient, TVUS revealed an intrauterine pregnancy with a gestational age of 5 weeks and 3 days and a right intact tubal ectopic pregnancy with a gestational age of 10 weeks and 5 days. Concurrently, the elevated serum quantitative b‐hCG level (30,883 mIU/mL) surpassed the expected level for the 5‐week intrauterine pregnancy. However, relying solely on b‐hCG for diagnosis is not considered reliable, and it should be complemented with TVUS. 19 Combining both diagnostic methods enhances the sensitivity of HP diagnosis.

Treatment of HP can also pose a challenge. The recommended approach is laparoscopic salpingectomy with minimal uterine manipulation, aimed at minimizing potential complications from the extrauterine pregnancy while preserving the intrauterine pregnancy. 14 , 19 Alternative management options for HP include expectant management for asymptomatic, stable patients. However, this approach has been associated with a high risk of subsequent rupture of the extrauterine pregnancy. 20 Other possibilities involve ultrasonographic embryo aspiration, though concerns about needle accessibility to the pregnancy site may arise. 19 Pharmacological treatment using methotrexate is also an option, but its use is feared due to the potential teratogenic risk to the intrauterine fetus. Some reports, however, have indicated successful outcomes with the use of methotrexate for the pharmacological treatment of HP. 21 In our patient, following the right laparoscopic salpingectomy with minimal uterine manipulation, the postoperative course was uneventful, and the intrauterine pregnancy continued to term, resulting in the delivery of a healthy neonate via Cesarean section at 38 weeks of pregnancy.

Given the marked difference in gestational age between our patient's right tubal ectopic pregnancy (10 weeks and 5 days) and the intrauterine pregnancy (5 weeks and 3 days), we arrived at a diagnosis strongly suggestive of human superfetation. This case, therefore, contributes to the very limited existing literature on human superfetation. Furthermore, the coexistence of another infrequent condition, HP, and the successful continuation of the intrauterine pregnancy to term yielding a healthy neonate makes our case unique and provides an opportunity to delve into the effect of the recent widespread use of ARTs on the encounter of these phenomena (superfetation and HP) and the challenges in diagnosis and management that need to be addressed accordingly.

We thus recommend that patients with a confirmed intrauterine pregnancy, especially those who have previously undergone ARTs and present with symptoms such as abdominal pain, anemia, and hemodynamic instability (including signs of hypovolemia and tachycardia) in the first trimester, undergo comprehensive adnexal screening through TVUS and serum quantitative b‐hCG measurement to rule out concurrent extrauterine pregnancy. It is crucial to recognize that confirming an intrauterine pregnancy alone does not eliminate the possibility of an ectopic pregnancy occurring at a different site. In addition, both TVUS and b‐hCG should also be utilized to carefully screen patients to exclude an ongoing intrauterine or extrauterine pregnancy before initiating another cycle of ovarian induction. Clinicians must consider HP as a potential differential diagnosis, especially in cases of first‐trimester abdominal pain alongside an ART‐achieved intrauterine pregnancy, and should remain vigilant, as the incidence of HP is on the rise in tandem with the increased utilization of ART.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Merhan Badran: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; methodology; project administration; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Mazed Labib: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; methodology; project administration. Omar Abouali: Data curation; software; writing – review and editing. Prakriti Pokhrel: Resources; software; supervision; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The ethical research board committee of El Shatby University Hospital for Obstetrics and Gynecology waived the ethical approval for reporting this case. Written informed consent was provided by our patient for medical care, research, and publishing. The patient is not identified. This case was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration contents.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor‐in‐Chief of this journal on request.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

Badran M, Labib M, Abouali O, Pokhrel P. Superfetation and heterotopic pregnancy: Case report of two rare phenomena coexisting and implications in the era of assisted reproductive technologies. Clin Case Rep. 2024;12:e8571. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.8571

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data included in the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pape O, Winer N, Paumier A, Philippe HJ, Flatrès B, Boog G. Superfetation: case report and review of the literature. J De Gynecol Obstet et Bio De La Rep. 2008;37(8):791‐795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nancy LS. Twins separated at birth: across a country and around the world/twin research: memorial tribute to Isaac Blickstein, MD; infanticide and sacrifice of archaic‐aged twins and triplets; prehistoric twin burials; highlights from a conference on three identical strangers /media reports: an atypical twin father; an Actor's twin brother; twin link to Tulsa, Oklahoma massacre; Superfetated twins; twin comedians and script writers; Indian Twins' loss to COVID‐19. Twin Res Human Gen. 2021;24(4):244‐250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. James JM, Jennifer J, Jessica CM, Sophia MR. Heterotopic triplet pregnancy after clomiphene citrate. Ochsner J. 2021;21(4):416‐418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lantieri T, Revelli A, Gaglioti P, et al. Superfetation after ovulation induction and intrauterine insemination performed during an unknown ectopic pregnancy. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2010;20(5):664‐666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ito A, Furukawa T, Nakaoka K, et al. Heterotopic pregnancy with suspicion of superfetation after the intrauterine insemination cycle with ovulation induction using clomiphene citrate: a case report. Clin Prac. 2019;9(1):1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alten T, Alten K. A case report of possible superfetation with evidence of ultrasound findings, gestational age calculations and postnatal complications. Obstet Gynecol Cases Rev. 2021;8:202. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Winardo DS, Wantania JJ. Heterotopic ovarian‐tubal pregnancies with possibilities of superfetation. Am J Med Case Rep. 2021;9(4):238‐240. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Juan JT, Miguel Angel G‐P, Carlos H, Antonio C. Unpredicted ovulations and conceptions during early pregnancy: an explanatory mechanism of human superfetation. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2013;25(7):1012‐1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tuppen GD, Fairs C, Chazal R, Justin CK. Spontaneous superfetation diagnosed in the first trimester with successful outcome. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;14:219‐221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Soudre G, Guettier X, Marpeau L, Larue L, Jault T, Barrat J. In utero early suspicion of superfetation by ultrasound examination: a case report. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1992;2(1):51‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baijal N, Fau Sahni M ‐ Verma N, Fau Verma N ‐ Kumar A, Fau Kumar A ‐ Parkhe N, Fau Parkhe N, Puliyel JM, Puliyel JM. Discordant Twins with the Smaller Baby Appropriate for Gestational Age—Unusual Manifestation of Superfoetation: a Case Report. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7:1471–2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harrison A, Valenzuela A, Gardiner J, Sargent M, Chessex P. Superfetation as a cause of growth discordance in a multiple pregnancy. J. Pediatr. 2005;147(2):254‐255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fadi B, Muhieddine S. Superfetation secondary to ovulation induction with clomiphene citrate: a case report. Fertil Steril. 1987;47(3):516‐518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Michal S, Monika S, Grzegorz R, Lukasz S, Olimpia S‐S. Heterotopic Pregnancy—Case Report. Wial Lek. 2020;73(4):828‐830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fuminori K, Norimasa S, Ikuo K, Yuko T, Hiroshi F, Takahide M. Spontaneous conception and intrauterine pregnancy in a symptomatic missed abortion of ectopic pregnancy conceived in the previous cycle. Hum. Reprod. 1996;11(6):1347‐1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aryan M, Noorulain K, Chandni Rajesh P, Essam E‐M. The rising incidence of heterotopic pregnancy: current perspectives and associations with in‐vitro fertilization. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;266:138‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bassem R, Elizabeth D, William JL. Ectopic pregnancy secondary to in vitro fertilisation‐embryo transfer: pathogenic mechanisms and management strategies. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13(1):1‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reece EA, Roy HP, Meredith FS, Mieczyslaw F, Todd WD. Combined intrauterine and extrauterine gestations: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;146:323‐330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ciebiera M, Słabuszewska‐Jóżwiak A, Zaręba K, Jakiel G. Heterotopic pregnancy – how easily you can go wrong in diagnosing? A case study. J Ultrason. 2018;18:355‐358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jin‐Bo L, Ling‐Zhi K, JianBo Y, et al. Management of Heterotopic Pregnancy: experience from 1 tertiary medical center. Medicine. 2016;95(5):e2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Simjanovic S, Vidosavljevic D, Stojanovic I. Methotrexate in local treatment of cervical heterotopic pregnancy with successful perinatal outcome: case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37(9):1241‐1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in the manuscript.