Abstract

Subject terms: Haematological cancer, Risk factors

To the Editor:

Telomere attrition and epigenetic modifications stand out as prominent molecular characteristics of aging-related biological processes and important risk factors for the development of haematologic diseases [1]. The relationship between telomere length and the risk of haematologic diseases has been extensively studied. However, the results of these studies have been conflicting [2]. The predictions of epigenetic clocks often deviate from chronological age, leading to a phenomenon known as epigenetic age acceleration (EAA) [3]. Empirical observations indicate that EAA is linked to an elevated risk of several health conditions [4]. However, this phenomenon has yet to be systematically evaluated for haematologic diseases. The objective of our study was to conduct a Mendelian randomization (MR) investigation, utilizing germline genetic variants as instrumental variables for both telomere length and EAA, to explore whether telomere length and EAA are associated with an increased risk of various haematologic diseases, including anaemia, lymphoma, leukaemia, myeloproliferative diseases, haemostasis and coagulation diseases, and other haematological disorders.

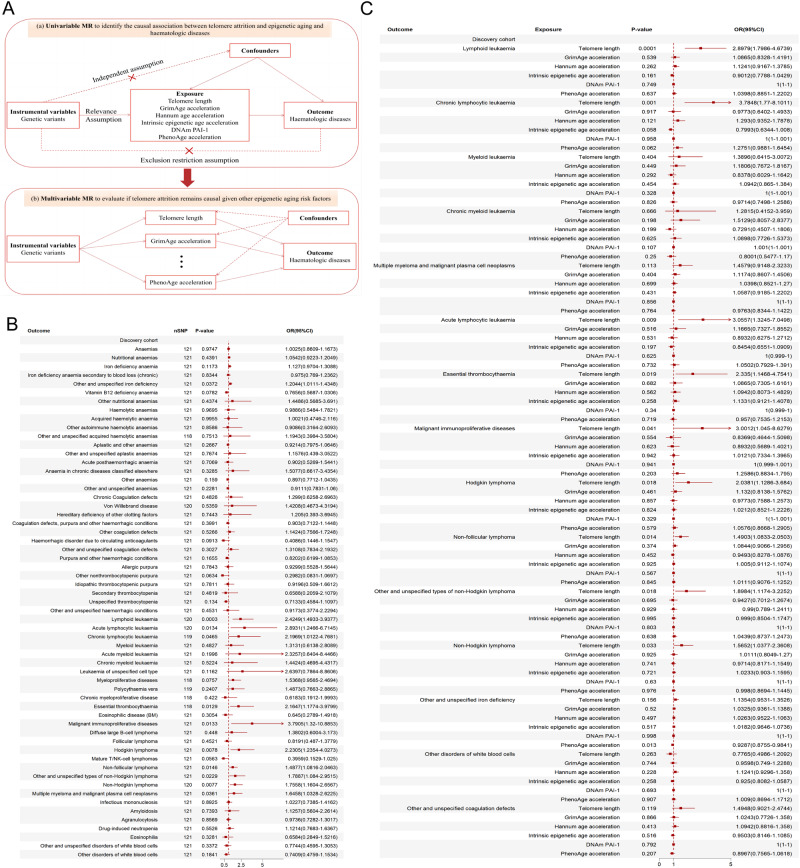

We initially conducted a two-sample single-variable MR (SVMR) study. This was then followed by verification using a validation dataset and different MR methods with different model assumptions. A series of multivariable MR (MVMR) analyses were then conducted to adjust for statistically significant risk factors. Furthermore, MVMR analysis based on Bayesian model averaging (MVMR-BMA) was performed to rank the aforementioned aging factors based on genetic evidence and assess whether telomere attrition, even in the presence of epigenetic aging, remains the true causal factor for haematologic diseases. Figure 1A presents an overview of the study design.

Fig. 1. Study design and Mendelian randomization results.

A Study design (a) The causal diagram illustrating the standard Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis with instrumental variables (IV) and the three necessary assumptions. (b) An illustrative diagram demonstrating the IV assumptions utilized in the multivariable MR model. B Two-sample single-variable Mendelian randomization results of telomere length on risk of multiple haematologic diseases in the discovery cohort. C Multivariable Mendelian randomization results of telomere length and five epigenetic age acceleration on risk of multiple haematologic diseases in the discovery cohort. MR, Mendelian randomization; IV, instrumental variable; DNAm PAI-1, DNA methylation-estimated plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; nSNP, number of single nucleotide polymorphism; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, The 95% confidence intervals.

For telomere length analysis, data sources were derived from the UK Biobank, a comprehensive population-based cohort study comprising 472,174 participants [5]. To conduct SVMR analyses, we followed a rigorous selection process to derive a final set of 121 instrumental variables (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). For epigenetic age acceleration measures, we acquired summary genetic association estimates from a recent GWAS meta-analysis of biological aging [6]. In certain cases, several SNPs were eliminated to address potential pleiotropic outliers. Specifically, we identified four independent SNPs for GrimAge, seven for HannumAge, 22 for Intrinsic HorvathAge, four for DNAm PAI-1 and 10 for PhenoAge (Supplementary Tables 3–8). Summary-level genetic association data for multiple haematologic disease outcomes were acquired from several sources (Table 1). In the discovery cohort, we obtained an extensive set of 59 GWASs from FinnGen [7]. Supplementary Fig. 1 demonstrates which specific haematologic diseases constitute each of the 59 GWAS summary statistic. In the validation cohort, GWAS data were sourced from both the UK Biobank cohort and several international consortia. In the MVMR analysis, we incorporated all the risk factors identified from the SVMR analysis, with a particular focus on assessing the significance of telomere length. To satisfy the instrumental SNP independence requirement in the MVMR-BMA, LD clumping was applied to the combination of SNPs of all aging risk factors. The detailed process of statistical analysis was provided in the Supplementary Method.

Table 1.

Characteristics of exposures and outcome.

| Variable | Source | Cases | Controls | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exopsure | ||||

| Telomere length | UK Biobank data | 472,174 | / | 472,174 |

| DNAm GrimAge acceleration | PMID: 34187551 | 34,467 | / | 34,467 |

| DNAm Hannum age acceleration | PMID: 34187551 | 34,449 | / | 34,449 |

| Intrinsic epigenetic age acceleration | PMID: 34187551 | 34,461 | / | 34,461 |

| DNAm PAI-1 | PMID: 34187551 | 34,448 | / | 34,448 |

| DNAm PhenoAge acceleration | PMID: 34187551 | 34,463 | / | 34,463 |

| Outcome of discovery cohort | ||||

| Anaemias | FinnGen data D3_ANAEMIA | 27,371 | 88,536 | 115,907 |

| Nutritional anaemias | FinnGen data D3_NUTRIANAEMIA | 7677 | 211,115 | 218,792 |

| Iron deficiency anaemia | FinnGen data D3_ANAEMIA_IRONDEF | 13,689 | 360,528 | 374,217 |

| Iron deficiency anaemia secondary to blood loss (chronic) | FinnGen data D3_ANAEMIA_IRONDEF_BLOODLOSS | 4852 | 360,528 | 365,380 |

| Other and unspecified iron deficiency | FinnGen data D3_ANAEMIA_IRONDEF_NAS | 10,208 | 360,528 | 370,736 |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency anaemia | FinnGen data D3_ANAEMIA_B12_DEF | 3351 | 360,528 | 363,879 |

| Other nutritional anaemia | FinnGen data D3_NUTRIANAEMIAOTHER | 283 | 360,528 | 360,811 |

| Haemolytic anaemias | FinnGen data D3_HAEMOLYTICANAEMIA | 838 | 376,439 | 377,277 |

| Acquired haemolytic anaemia | FinnGen data D3_ACQHAEMOLYTICANAEMIA | 606 | 376,439 | 377,045 |

| Other autoimmune haemolytic anaemias | FinnGen data D3_AIHA_OTHER | 280 | 376,439 | 376,719 |

| Other and unspecified acquired haemolytic anaemias | FinnGen data D3_ACQHAEMOLYTICANAEMIANAS | 241 | 376,439 | 376,680 |

| Aplastic and other anaemias | FinnGen data D3_APLASTICANDOTHANAEMIA | 6554 | 212,238 | 218,792 |

| Other and unspecified aplastic anaemias | FinnGen data D3_OTHERAPLASTICANAEMIA | 288 | 362,319 | 362,607 |

| Acute posthaemorrhagic anaemia | FinnGen data D3_ACUTEPOSTBLEEDANAEMIA | 976 | 362,319 | 363,295 |

| Anaemia in chronic diseases classified elsewhere | FinnGen data D3_ANAEMIAINCHRONICDISEASE | 585 | 362,319 | 362,904 |

| Other anaemias | FinnGen data D3_OTHERANAEMIA | 6005 | 212,238 | 218,243 |

| Other and unspecified anaemias | FinnGen data D3_ANAEMIANAS | 13,600 | 362,319 | 375,919 |

| Chronic Coagulation defects | FinnGen data D3_COAGDEF | 626 | 376,651 | 377,277 |

| Von Willebrand disease | FinnGen data D3_VONVILLEBRAND | 336 | 371,504 | 371,840 |

| Hereditary deficiency of other clotting factors | FinnGen data D3_HEREDOTHCLOFACTORS | 216 | 371,504 | 371,720 |

| Coagulation defects, purpura and other haemorrhagic conditions | FinnGen data D3_COAGDEF_PURPUR_HAEMORRHAGIC | 5773 | 371,504 | 377,277 |

| Other coagulation defects | FinnGen data D3_COAGOTHER | 1904 | 371,504 | 373,408 |

| Haemorrhagic disorder due to circulating anticoagulants | FinnGen data D3_HAEMORRHAGCIRGUANTICO | 267 | 371,504 | 371,771 |

| Other and unspecified coagulation defects | FinnGen data D3_COAGDEFNAS | 1217 | 371,504 | 372,721 |

| Purpura and other haemorrhagic conditions | FinnGen data D3_PURPURA_AND3_OTHER_HAEMORRHAGIC | 3900 | 371,504 | 375,404 |

| Allergic purpura | FinnGen data D3_ALLERGPURPURA | 856 | 371,504 | 372,360 |

| Other nonthrombocytopenic purpura | FinnGen data D3_OTHNONTHROMBOCYTOPENPURPURA | 214 | 371,504 | 371,718 |

| Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura |

FinnGen data D3_ITP |

810 | 371,504 | 372,314 |

| Secondary thrombocytopenia | FinnGen data D3_SCNDTHROMBOCYTOPENIA | 298 | 371,504 | 371,802 |

| Unspecified thrombocytopenia | FinnGen data D3_THROMBOCYTOPENIANAS | 1869 | 371,504 | 373,373 |

| Other and unspecified haemorrhagic conditions | FinnGen data D3_HAEMORRHAGICNAS | 404 | 371,504 | 371,908 |

| Lymphoid leukaemia | FinnGen data CD2_LYMPHOID_LEUKAEMIA_EXALLC | 1493 | 299,952 | 301,445 |

| Acute lymphocytic leukaemia | FinnGen data C3_ALL_EXALLC | 184 | 287,136 | 287,320 |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia | FinnGen data C3_CLL_EXALLC | 624 | 287,133 | 287,757 |

| Myeloid leukaemia | FinnGen data CD2_MYELOID_LEUKAEMIA_EXALLC | 674 | 299,952 | 300,626 |

| Acute myeloid leukaemia | FinnGen data C3_AML_EXALLC | 231 | 287,136 | 287,367 |

| Chronic myeloid leukaemia [CML]BCR/ABL+ | FinnGen data CML | 232 | 375,158 | 375,390 |

| Leukaemia of unspecified cell type | FinnGen data CD2_LEUKAEMIA_NAS_EXALLC | 220 | 299,952 | 300,172 |

| Myeloproliferative diseases | FinnGen data MYELOPROF_NONCML | 1887 | 375,158 | 377,045 |

| Polycythaemia vera | FinnGen data POLYCYTVERA | 942 | 286,553 | 287,495 |

| Chronic myeloproliferative disease | FinnGen data CHRONMYELOPRO | 328 | 375,158 | 375,486 |

| Essential thrombocythaemia | FinnGen data THROMBOCYTAEMIA | 967 | 286,488 | 287,455 |

| Eosinophilic disease (BM) | FinnGen data ESOSINOPHIL_DISEASE | 398 | 212,144 | 212,542 |

| Malignant immunoproliferative diseases | FinnGen data CD2_IMMUNOPROLIFERATIVE_EXALLC | 223 | 299,952 | 300,175 |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | FinnGen data C3_DLBCL_EXALLC | 1010 | 287,137 | 288,147 |

| Follicular lymphoma | FinnGen data CD2_FOLLICULAR_LYMPHOMA_EXALLC | 1081 | 299,952 | 301,033 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | FinnGen data CD2_HODGKIN_LYMPHOMA_EXALLC | 780 | 299,952 | 300,732 |

| Mature T/NK-cell lymphomas | FinnGen data CD2_TNK_LYMPHOMA_EXALLC | 335 | 299,952 | 300,287 |

| Non-follicular lymphoma | FinnGen data CD2_NONFOLLICULAR_LYMPHOMA_EXALLC | 2602 | 299,952 | 302,554 |

| Other and unspecified types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma | FinnGen data CD2_NONHODGKIN_NAS_EXALLC | 1088 | 299,952 | 301,040 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | FinnGen data C3_NONHODGKIN_EXALLC | 928 | 287,137 | 288,065 |

| Multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms | FinnGen data CD2_MULTIPLE_MYELOMA_PLASMA_CELL_EXALLC | 1249 | 299,952 | 301,201 |

| Infectious mononucleosis | FinnGen data AB1_EBV | 2353 | 367,472 | 369,825 |

| Amyloidosis | FinnGen data E4_AMYLOIDOSIS | 413 | 324,150 | 324,563 |

| Agranulocytosis | FinnGen data D3_AGRANULOCYTOSIS | 3234 | 370,400 | 373,634 |

| Drug-induced neutropenia | FinnGen data DRUGADVERS_NEUTROPENIA | 1978 | 375,299 | 377,277 |

| Eosinophilia | FinnGen data D3_EOSINOPHILIA | 182 | 215,755 | 215,937 |

| Other and unspecified disorders of white blood cells | FinnGen data D3_WHITEBLOODCELLNAS | 1077 | 370,400 | 371,477 |

| Other disorders of white blood cells | FinnGen data D3_OTHERWHITECELL | 1483 | 370,400 | 371,883 |

| Outcome of validation cohort | ||||

| Leukaemia | UK Biobank data | 1260 | 372,016 | 373,276 |

| Lymphoid leukaemia | UK Biobank data | 760 | 372,016 | 372,776 |

| Myeloid leukaemia | UK Biobank data | 462 | 372,016 | 372,478 |

| Multiple myeloma | UK Biobank data | 601 | 372,016 | 372,617 |

| Myeloproliferative neoplasms | PMID: 33057200 | 1086 | 407,155 | 408,241 |

| Lymphomas | UK Biobank data | 1752 | 359,442 | 361,194 |

The SVMR results between genetically determined telomere length and haematologic diseases are presented in Fig. 1B. Genetically increased telomere length was associated with higher ORs (95% CIs) of disease in 10 of the 21 haematological malignancies (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 3). Associations (IVW ORs; [95% CIs] per 1-SD change in genetically increased telomere length; P-value) were observed: lymphoid leukaemia (2.4249; [1.4933–3.9377]; 0.0003), acute lymphocytic leukaemia (2.8931; [1.2466–6.7145]; 0.0134), chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (2.1969; [1.0122–4.7681]; 0.0465), essential thrombocythaemia (2.1647; [1.1774–3.9799]; 0.0129), malignant immunoproliferative diseases (3.7905; [1.3200–10.8853]; 0.0133), Hodgkin lymphoma (2.2305; [1.2354–4.0273]; 0.0078), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (1.7558; [1.1604–2.6567]; 0.0077), non-follicular lymphoma (1.4877; [1.0816–2.0463]; 0.0146), other and unspecified types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (1.7887; [1.0840–2.9515]; 0.0229) and multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms (1.6458; [1.0328–2.6225]; 0.0361) (Fig. 1B). These significant results were successfully replicated in an independent validation cohort. (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

Utilizing a meta-analysis of IVW SVMR, we found no evidence of genetically predicted DNA methylation GrimAge acceleration associated with the risk of the mentioned haematologic diseases. Causal estimation showed that genetically determined Hannum age acceleration was associated with a lower risk of developing chronic myeloid leukaemia (OR = 0.5553 per year increase in Hannum age acceleration, 95% CI 0.3182–0.9690, P value = 0.0384). Our findings showed no evidence of causality between genetically predicted Intrinsic EAA and the aforementioned haematologic disorders. Genetically predicted higher levels of DNAm PAI-1 exhibited marginally significant causal associations with an increased risk of chronic myeloid leukaemia. We also found that higher PhenoAge acceleration was associated with increased risks of myeloid leukaemia (OR = 1.3018 per year increase in PhenoAge acceleration, 95% CI 1.0596–1.5994, P value = 0.0120), chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (OR = 1.2280, 95% CI 1.0118–1.4905, P value = 0.0376), and lymphoid leukaemia (OR = 1.1539, 95% CI 1.0267–1.2968, P value = 0.0163) (Supplementary Fig. 2b–f). The causal analysis of genetically determined 5 EAA in an independent validation cohort yielded similar results (Supplementary Fig. 4). The consistency of these above SVMR results was further supported by other MR methods, and no heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy were detected (Supplementary Tables 9 and 10).

Subsequently, our focus shifted to statistically significant haematological disorders identified through SVMR analysis. We conducted MVMR analysis to adjust and compare the impact of telomere length and the role of epigenetic age acceleration in the risk of these haematological disorders (Supplementary Tables 11 and 12). After adjusting for EAA using the MVMR-IVW method, telomere length was found to be associated with several haematological malignancy outcomes. In the discovery cohort, these outcomes included lymphoid leukaemia (IVW OR 2.8979, 95% CI 1.7986–4.6739, P <0.0001), chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (3.7848, 1.7700–8.1011, 0.0010), acute lymphocytic leukaemia (3.0557, 1.3245–7.0498, 0.0090), essential thrombocythaemia (2.3350, 1.1468–4.7541, 0.0190), malignant immunoproliferative diseases (3.0012, 1.0450–8.6379, 0.0410), Hodgkin lymphoma (2.0381, 1.1286–3.6840, 0.0180), non–follicular lymphoma (1.4903, 1.0833–2.0503, 0.0140), other and unspecified types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (1.8984, 1.1174–3.2252, 0.0180) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (1.5652, 1.0377–2.3608, 0.0330) (Fig. 1C). However, the significant association observed between telomere length and multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms in the SVMR model was attenuated in the MVMR model and was no longer significant (Fig. 1C). The effects of DNA methylation Hannum age acceleration and DNAm PAI-1 levels that were previously observed in the SVMR for chronic myeloid leukaemia were no longer significant in the MVMR after adjusting for other EAA and telomere length (Fig. 1C). However, in the validation cohort, after adjusting for telomere length and other EAA using MVMR-LASSO regression and MVMR-Egger, genetically predicted Hannum age acceleration remained significantly and positively associated with leukaemia, lymphoid leukaemia, myeloid leukaemia, multiple myeloma (Supplementary Table 13). Significant associations were observed between genetically predicted PhenoAge acceleration and myeloid leukaemia, other disorders of white blood cells, and other and unspecified coagulation defects in the SVMR were attenuated in the MVMR model, and the results were no longer significant (Fig. 1C). Similar results of MVMR analysis were also obtained in the validation cohort (Supplementary Fig. 5).

To prioritize aging-related risk factors for haematological diseases based on our univariable outcomes, we employed a novel multivariable approach, MVMR-BMA. During the model diagnostics, we successfully detected influential and outlying instrumental SNPs (Supplementary Fig. 6). Subsequently, we performed an analysis after eliminating influential and outlying SNPs. Supplementary Table 14 presents the top 10 models ranked by their model PP, along with the MIP and the model-averaged causal effect estimates of the six aging-related factors. Remarkably, the results revealed that telomere length had the strongest association with the risk of haematologic diseases when compared with the five EAA. Notably, analogous results were obtained when all 144 instrumental variables (IVs) were integrated into the analysis (Supplementary Table 15).

Our findings consistently align with results from prospective observational studies, which typically indicate an increased risk of lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma in individuals with longer telomeres [8–10]. However, the outcomes of an association cohort study, utilizing data from the UK Biobank, contradict our research findings. This study reveals a significantly higher prevalence of lymphoid and myeloid leukaemia in participants with shorter leukocyte telomere length [11]. These contradictory findings may be attributed to reverse causation in the retrospective studies, stemming from the absence of temporal information. Previous GWAS studies have revealed connections between longer telomeres and specific variations in multiple telomere-related genes such as TERT, TERC, and POT1 [12]. A recently published investigation highlighted that individuals with overly extended telomeres and an inherited ability to elongate telomeres due to POT1 dysfunction are more susceptible to developing lymphoid and myeloid clonal hematopoiesis [13].

The crucial role of epigenetic regulation in the development of haematologic cancers has been underscored by many studies. Our MR estimates for the association between EAA and various forms of leukaemia, namely lymphoid leukaemia, myeloid leukaemia, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and chronic myeloid leukaemia were broadly consistent with the outcomes reported in the previous studies. For example, Maegawa et al. demonstrate that methylation changes arise as a function of age in normal hematopoiesis and are accelerated in MDS and at the transition from MDS to AML [14]. Nannini et al. discovered significant connections between EAA and the time to relapse among patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia [15]. Our study findings suggest that longer telomeres are linked to a higher risk of most haematologic malignancies, but genetically predicted telomere length and EAA do not significantly influence the risk of nearly all benign haematological disorders. This indicates the potential clinical relevance of telomere length, holding promising prospects for clinical implementation.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

YL and LZ designed the study, wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JC and TS conducted statistical analyses and revised the manuscript. RFF, XFL, FX played roles in acquisition of the data and analyses. WL, YFC, MKJ, XYD and HD participated in data interpretation. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript. The guarantor confirms that all listed authors meet the authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2022-I2M-2-003, 2023-I2M-QJ-015), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82270152, 81970121, 82100151), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC2507802), Clinical Research Fund of National Center for Clinical Medical Research of Hematology Diseases (2023NCRCA0109).

Data availability

All data used in the current study are publicly available GWAS summary data.

Code availability

For original data and code, please contact zhanglei1@ihcams.ac.cn.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study utilized publicly available data from participant studies that had already received ethical approval from a committee responsible for human experimentation. No additional ethical approval was necessary for this particular study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yang Li, Jia Chen, Ting Sun.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41408-024-01035-5.

References

- 1.Ahmad H, Jahn N, Jaiswal S. Clonal Hematopoiesis and Its Impact on Human Health. Annu Rev Med. 2023;74:249–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042921-112347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nogueira BMD, Machado CB, Montenegro RC, DE Moraes MEA, Moreira-Nunes CA. Telomere Length and Hematological Disorders: A Review. Vivo. 2020;34:3093–101. doi: 10.21873/invivo.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horvath S, Raj K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19:371–84. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fransquet PD, Wrigglesworth J, Woods RL, Ernst ME, Ryan J. The epigenetic clock as a predictor of disease and mortality risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Epigenet. 2019;11:62. doi: 10.1186/s13148-019-0656-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Codd V, Wang Q, Allara E, Musicha C, Kaptoge S, Stoma S, et al. Polygenic basis and biomedical consequences of telomere length variation. Nat Genet. 2021;53:1425–33. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00944-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCartney DL, Min JL, Richmond RC, Lu AT, Sobczyk MK, Davies G, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify 137 genetic loci for DNA methylation biomarkers of aging. Genome Biol. 2021;22:194. doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02398-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurki MI, Karjalainen J, Palta P, Sipila TP, Kristiansson K, Donner KM, et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature. 2023;613:508–18. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05473-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hosnijeh FS, Matullo G, Russo A, Guarrera S, Modica F, Nieters A, et al. Prediagnostic telomere length and risk of B-cell lymphoma-Results from the EPIC cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2910–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lan Q, Cawthon R, Shen M, Weinstein SJ, Virtamo J, Lim U, et al. A prospective study of telomere length measured by monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7429–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willeit P, Willeit J, Mayr A, Weger S, Oberhollenzer F, Brandstatter A, et al. Telomere length and risk of incident cancer and cancer mortality. JAMA. 2010;304:69–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider CV, Schneider KM, Teumer A, Rudolph KL, Hartmann D, Rader DJ, et al. Association of Telomere Length With Risk of Disease and Mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:291–300. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.7804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Codd V, Nelson CP, Albrecht E, Mangino M, Deelen J, Buxton JL, et al. Identification of seven loci affecting mean telomere length and their association with disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:422–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeBoy EA, Tassia MG, Schratz KE, Yan SM, Cosner ZL, McNally EJ, et al. Familial Clonal Hematopoiesis in a Long Telomere Syndrome. N. Engl J Med. 2023;388:2422–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2300503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maegawa S, Gough SM, Watanabe-Okochi N, Lu Y, Zhang N, Castoro RJ, et al. Age-related epigenetic drift in the pathogenesis of MDS and AML. Genome Res. 2014;24:580–91. doi: 10.1101/gr.157529.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nannini DR, Cortese R, Egwom P, Palaniyandi S, Hildebrandt GC. Time to relapse in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and DNA-methylation-based biological age. Clin Epigenet. 2023;15:81. doi: 10.1186/s13148-023-01496-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used in the current study are publicly available GWAS summary data.

For original data and code, please contact zhanglei1@ihcams.ac.cn.