Key Points

Questions

Do US government officials and their family members involved in anomalous health incidents (AHIs) differ from control participants with respect to clinical, biomarker, and research assessments?

Findings

In this exploratory study that included 86 participants reporting AHIs and 30 vocationally matched control participants, there were no significant differences in most tests of auditory, vestibular, cognitive, visual function, or blood biomarkers between the groups. Participants with AHIs performed significantly worse on self-reported and objective measures of balance, and had significantly increased symptoms of fatigue, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression compared with the control participants; 24 participants (28%) with AHIs presented with functional neurological disorders.

Meaning

In this exploratory study, there were no significant differences between individuals reporting AHIs and matched control participants with respect to most clinical, research, and biomarker measures, except for self-reported and objective measures of imbalance; symptoms of fatigue, posttraumatic stress, and depression; and the development of functional neurological disorders in some.

Abstract

Importance

Since 2015, US government and related personnel have reported dizziness, pain, visual problems, and cognitive dysfunction after experiencing intrusive sounds and head pressure. The US government has labeled these anomalous health incidents (AHIs).

Objective

To assess whether participants with AHIs differ significantly from US government control participants with respect to clinical, research, and biomarker assessments.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Exploratory study conducted between June 2018 and July 2022 at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, involving 86 US government staff and family members with AHIs from Cuba, Austria, China, and other locations as well as 30 US government control participants.

Exposures

AHIs.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Participants were assessed with extensive clinical, auditory, vestibular, balance, visual, neuropsychological, and blood biomarkers (glial fibrillary acidic protein and neurofilament light) testing. The patients were analyzed based on the risk characteristics of the AHI identifying concerning cases as well as geographic location.

Results

Eighty-six participants with AHIs (42 women and 44 men; mean [SD] age, 42.1 [9.1] years) and 30 vocationally matched government control participants (11 women and 19 men; mean [SD] age, 43.8 [10.1] years) were included in the analyses. Participants with AHIs were evaluated a median of 76 days (IQR, 30-537) from the most recent incident. In general, there were no significant differences between participants with AHIs and control participants in most tests of auditory, vestibular, cognitive, or visual function as well as levels of the blood biomarkers. Participants with AHIs had significantly increased fatigue, depression, posttraumatic stress, imbalance, and neurobehavioral symptoms compared with the control participants. There were no differences in these findings based on the risk characteristics of the incident or geographic location of the AHIs. Twenty-four patients (28%) with AHI presented with functional neurological disorders.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this exploratory study, there were no significant differences between individuals reporting AHIs and matched control participants with respect to most clinical, research, and biomarker measures, except for objective and self-reported measures of imbalance and symptoms of fatigue, posttraumatic stress, and depression. This study did not replicate the findings of previous studies, although differences in the populations included and the timing of assessments limit direct comparisons.

This study assesses whether participants with anomalous health incidents (AHIs) differ significantly from US government control participants with respect to clinical, research, and biomarker assessments.

Introduction

Since 2015, many US government personnel serving internationally have reported experiencing intrusive sounds and head pressure. For some individuals, these events were associated with the abrupt onset of disruptive symptoms including dizziness, pain, visual problems, and cognitive dysfunction. Initially, this constellation of symptoms was labeled “Havana syndrome” due to the cases mainly occurring in Cuba. However, as reports of similar events occurred in other countries, the US government labeled these events anomalous health incidents (AHIs).1

The etiologies of AHIs are unclear. A 2020 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report2 and a more recent 2022 Intelligence Community (IC) Experts Panel on Anomalous Health Incidents3 suggested pulsed microwave radiation as a plausible mechanism of injury in a subset of cases. Many other statements are less supportive of directed energy as a cause.4,5 A 2022 report from the IC cast doubts on the possibility of a “sustained global campaign by a foreign power” to cause harm.6 An extensive IC report published in 2023 by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence found it was “very” unlikely that a directed energy weapon was involved.7 Some have suggested that functional neurological disorders may be the cause for these cases.8,9,10

There have been a few clinical reports of patients experiencing an AHI.4,11,12,13,14,15,16 The 2 most comprehensive studies published were on individuals who reported an AHI while in Havana. The first study detailed the individuals’ neurocognitive and balance differences compared with a control group,11 while the second suggested differences in brain volumes, diffusion tensor imaging, and functional connectivity between the AHIs and control participants.12 While the authors of these studies were appropriately circumspect in their conclusions, the subsequent public and media narrative built around these studies was that this population has findings consistent with traumatic brain injury and that advanced imaging techniques could differentiate this group from a control population.12,16

In early 2018, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), in consultation with the Department of State (DOS) and the IC, began an investigation of AHIs. The NIH created a referral infrastructure, engaged content experts from across the NIH Intramural Research Program, and enrolled individuals in an exploratory natural history study.

This study had 3 objectives. First, the study aimed to diagnose any known disorders in this patient population that might explain the symptoms; second, identify any consistent differences between the participants with AHIs and a control group with a similar vocational background; and third, reproduce the findings of prior researchers. In this study, and the companion article17 on imaging, the findings of these investigations are reported.

Methods

Study Design and Participants With AHIs

The study was approved by the NIH Institutional Review Board. All participants gave written, informed consent. A detailed description of our methods appear in the eMethods in Supplement 1. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

US government employees and their adult family members were enrolled in a prospective cohort study between June 2018 and November 2021, and were seen at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Data collection continued for this analysis through July 2022. Patients were referred, nonconsecutively, from multiple locations including Cuba, China, Austria, and the US by the DOS Bureau of Medical Services, members of the IC, and other federal agencies. Participants were seen for a week-long initial visit and then yearly for complete repeat examinations. The inclusion criteria for the control and AHI groups included (1) referral from a US government entity, (2) age older than 18 years, and (3) ability to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included (1) medical or psychological instability such that the participant could not reasonably be expected to fulfill the study requirements and (2) pregnancy.

The participants with AHIs were separated into 2 groups (AHI 1 and AHI 2) based on whether their case was consistent with 4 core characteristics used by a US intelligence panel investigating AHIs to identify cases of concern.3 The AHI 1 group included those who had (1) acute onset of audiovestibular sensory phenomena, sometimes including sound or pressure in only 1 ear or on 1 side of the head; (2) nearly simultaneous signs and symptoms such as vertigo, loss of balance, and ear pain; (3) a strong sense of locality or directionality; and (4) the absence of known environmental or medical conditions that could have caused the reported signs and symptoms. All other cases were considered AHI 2. Directionality was considered present if the individual felt the sound was coming from a particular point in space or if the pressure was unilateral. Locality was considered present if the symptoms varied depending on the individual’s movements during the incident. Data from patient histories and DOS investigations were used to help determine these AHI groupings.

The diagnoses of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD)18 were made when participants fully met the Bárány Society criteria. PPPD is the subtype of functional neurological disorder where the most prominent symptom is chronic dizziness or unsteadiness. The diagnosis of headache subtypes was made based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders, Third edition.19 Somatic symptoms were considered clinically elevated when the t score (mean [SD], 50 [10]) was 65 or greater on the Reconstructed Clinical Scale 1, per the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–2 Restructured Form manual.20

Control Population Selection and Recruitment

Vocationally matched control participants were recruited from the US government: IC and the DOS. Twelve of the control participants had been stationed in Cuba, denied events, and were asymptomatic. Others had similar vocational backgrounds as the participants with AHIs and were preparing to deploy overseas. Inclusion criteria included employment in the US government with a history of or planned overseas deployment and good general health (detailed in the eMethods in Supplement 1).

Data Collection

The clinical assessments of hearing, vision, ocular motor, cognitive, vestibular, and balance function (eTables 1-4 in Supplement 1) and blood biomarkers (neurofilament light [NfL] and glial fibrillary acidic protein [GFAP]) were collected using standard clinical procedures. Only 2 of the participants had predeployment blood draws. All participants were generally administered all assessments and included in the analyses unless there was a clinically relevant reason to exclude the participant from a particular domain assessment (eg, known pre-existing medical condition affecting that particular domain) or the validity criteria for a particular domain were not met. However, the control population did not perform objective measures of balance (NeuroCom force plate tests) given the widely used clinical norms available. The control participants also did not have vision concerns and did not undergo ophthalmologic evaluation. Methods for collection of magnetic resonance imaging data can be found in our companion article.17 Assessors were unblinded to the AHI status of the participants.

Outcomes

The main outcome measures were differences in cognitive, auditory, vision, ocular motor, vestibular, balance, and blood biomarker (GFAP and NfL) testing between the participants with AHIs and vocationally matched US government control participants (see eMethods in Supplement 1 for details of the tests). We also assessed these measures secondarily in relation to AHI 1 and AHI 2 as well geographic location of the AHIs.

Cognitive assessments included the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV) subtests and several other measures.21 Self-reported symptoms, such as fatigue, neurobehavioral, posttraumatic stress, depression, pain catastrophizing, and quality of life, were quantified using the Fatigue Severity Scale,22 the Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory,23 the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5,24 the Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition,25 the Pain Catastrophizing Scale,26 and the Satisfaction With Life Scale,27 respectively. Details of additional neuropsychological tests as well as auditory, vision, ocular motor, and vestibular testing can be found in the eMethods and eTable 21 in Supplement 1. Balance was assessed with subjective measures, which included the self-reported Dizziness Handicap Inventory, Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale, and the clinician-rated Functional Gait Assessment, as well as objective measures that included the NeuroCom force plate Sensory Organization Test (SOT) and Limits of Stability test. The primary comparison involved AHI vs control participants, although NeuroCom tests and auditory processing assessments were scored using published normative criteria.

Statistical Analysis

When this study began in 2018, our primary comparison was all AHI vs control participants. However, in February 2022, the classification on which our AHI 1 and AHI 2 groups was based became publicly available. Because this classification was developed by the IC, we thought it was important to add these comparisons to our analyses. For comparison of AHI vs control group and AHI subcategories (AHI 1 and AHI 2), we constructed 3 different models with subcategories nested within each model. First, we fit a pair of frequentist models: a nonparametric rank-based model using the rank-based inverse normal transformation28 on the response variables due to the skewed nature of the data, followed by a linear gaussian model allowing us to control for age. Second, to better control for statistical noise in our analyses and to address the issue of multiplicity,29 we also performed bayesian analyses, using weakly informative regularization priors.30 Given the numerous tests or outcome variables in the study, we performed analyses with and without adjusting for multiplicity. We report the Tukey Honestly Significant Difference test31 (pairwise comparisons) or Šidák-adjusted32 (groupwise comparisons) P values. We report findings both unadjusted and adjusted for multiplicity. We report the frequentist statistics in the main results; the bayesian analyses results are presented in eTables 8B, 9B, 11B, 12B, 14B, 15B, and 17-20 in Supplement 1. To assess the relationship between our clinical variables and brain magnetic resonance imaging regions of interest reported previously,12 we performed Spearman rank correlation analysis between the clinical and brain imaging variables. Few individuals had missing data for some of the outcome variables and those are reported in the Table and Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4. The threshold for statistical significance was set at 2-sided P < .05. A detailed statistical analysis plan is provided in the Supplement (page 22). Statistical analyses were performed in R (version 3.0.3, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1 (GraphPad).

Table. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Participants.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anomalous health incidents | Present before anomalous health incidenta | Present during or after anomalous health incidenta | US government controls | |

| No. | 86 | 30 | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 42.1 (9.1) | 43.8 (10.1) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 42 (49) | 11 (37) | ||

| Male | 44 (51) | 19 (63) | ||

| Education from first grade, median (IQR), y | 17 (16-18) | 18 (16-18) | ||

| US government employee family member | 10 (12) | NA | ||

| Reduced capacity and/or unable to work due to anomalous health incidents | 28 (33) | NA | ||

| Time from the most recent incident to evaluation, median (IQR), d | 76 (30-537) | NA | ||

| Sound or pressure | 70 (81) | NA | ||

| Directionality and/or locality | 59 (69) | NA | ||

| Symptomsb | ||||

| Headache | 35 (41) | 64 (74) | 12 (40) | |

| Sleep dysfunction | 12 (18) | 49 (59) | 1 (3) | |

| Depression | 11 (13) | 16 (19)c | 0c | |

| Vision changes | 10 (12) | 32 (37) | 0 | |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 8 (9) | 9 (11)c | 0c | |

| Imbalance | 4 (5) | 45 (52) | 0 | |

| Cognitive | 1 (1) | 59 (69) | 0 | |

| Dizziness | 1 (1) | 32 (37) | 0 | |

| Diagnoses | ||||

| Migraine headache | 23 (27) | 31 (36) | 2 (7) | |

| Tinnitus | 14/85 (16) | 48 (56) | 0 | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 11/83 (13) | 13/84 (15) | 0 | |

| Cranial neuropathy | 5/85 (6) | 7 (8) | 0 | |

| Headache, unspecified | 4 (5) | 16 (19) | 12 (40) | |

| Cancer | 3 (4) | 5 (6) | 0 | |

| Strabismus | 2/84 (2) | 4/85 (5) | 0 | |

| Seizure disorder | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | |

| Functional neurological disorder | 1 (1) | 24 (28) | 0 | |

| Current cataract | 1/76 (1) | 21/84 (25) | 0 | |

| Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 0 | |

| New daily persistent headache | 0 | 25 (29) | 0 | |

| Tension-type headache | 0 | 3 (3) | 0 | |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Data in these columns are not mutually exclusive. If a participant had symptoms or diagnosis before the anomalous health incident and continued to have it after the anomalous health incident, they are counted in both columns.

Based on history and physical examination.

Based on screening instruments.

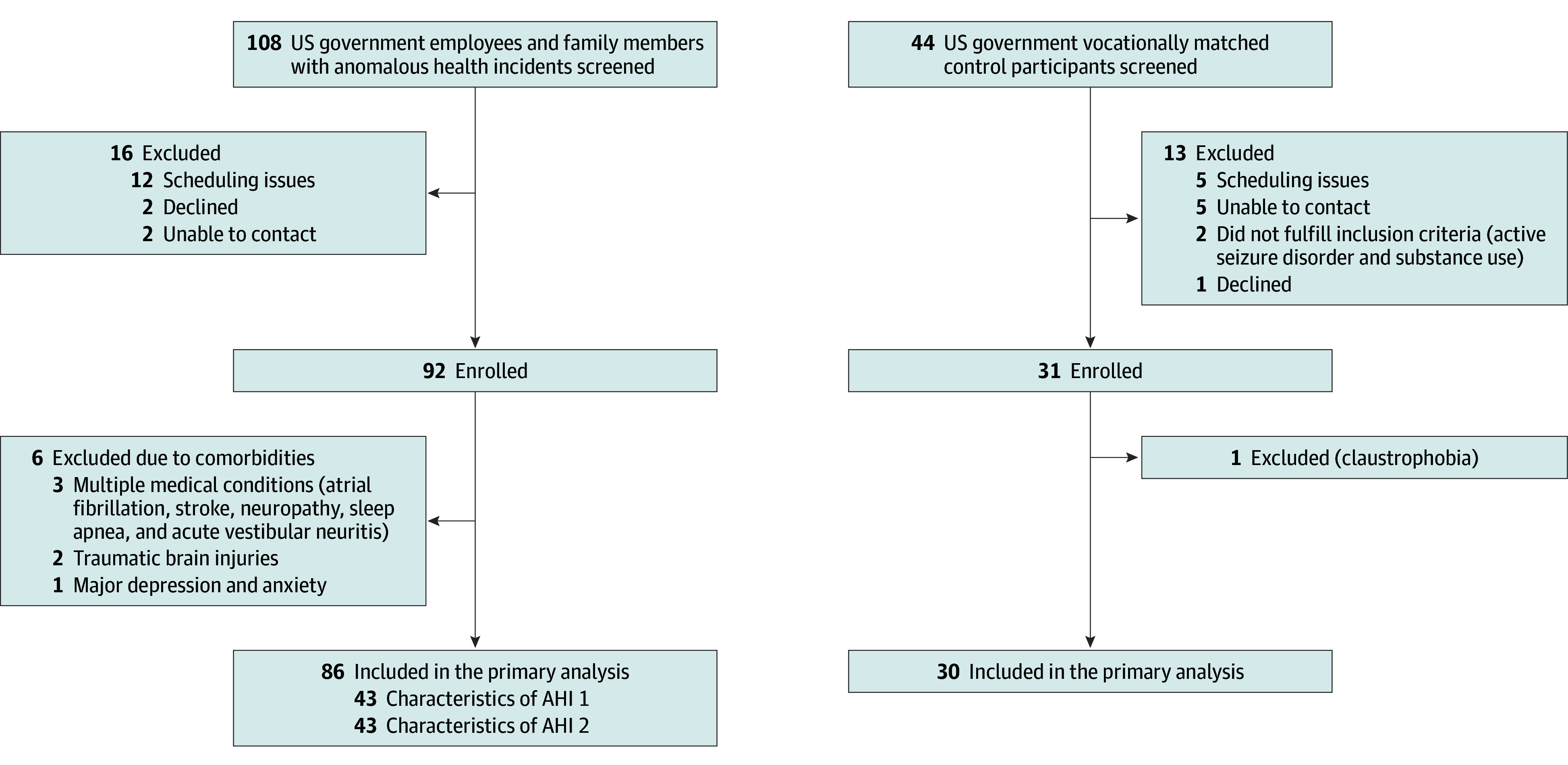

Figure 1. Overview of the Study Participants.

Characteristics of the first anomalous health incident group (AHI 1) include (1) the acute onset of audiovestibular sensory phenomena, including sound or pressure in only 1 ear or on 1 side of the head; (2) nearly simultaneous signs and symptoms such as vertigo, loss of balance, and ear pain; (3) a strong sense of locality or directionality; and (4) the absence of known environmental or medical conditions that could have caused the reported signs and symptoms. The other group, AHI 2, includes all cases that did not fulfill the above criteria.

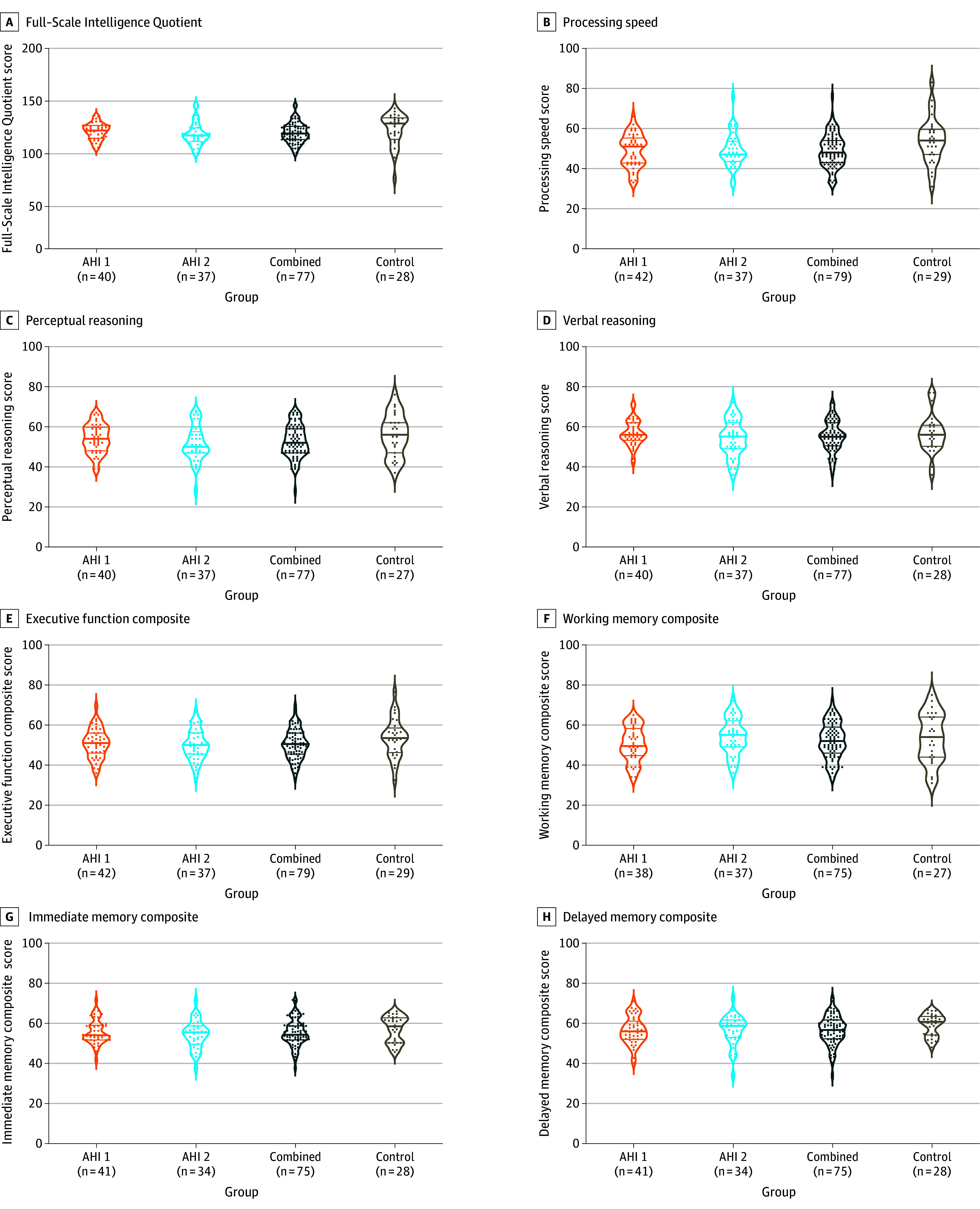

Figure 2. Cognitive Findings From the Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient.

All data shown were collected during the initial visit to the National Institutes of Health (median, 76 days [IQR, 30-537]) after the most recent anomalous health incident (AHI). The plots show density, with each dot representing an individual. The thicker, middle horizonal line in the plot indicates the median, while the other 2 lines represent the IQR. The P values are from a rank-based regression and corrected for multiple comparisons using the Šidák method (groupwise) and Tukey Honestly Significant Difference (pairwise). The Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient raw score and its subdomains (B, C, D, F, and G) are shown, as well as calculated composite scores (E, G, and H) (page 9 in Supplement 1). A lower score indicates worse performance. The AHI groups did not differ significantly from each other or compared with control participants (P > .05).

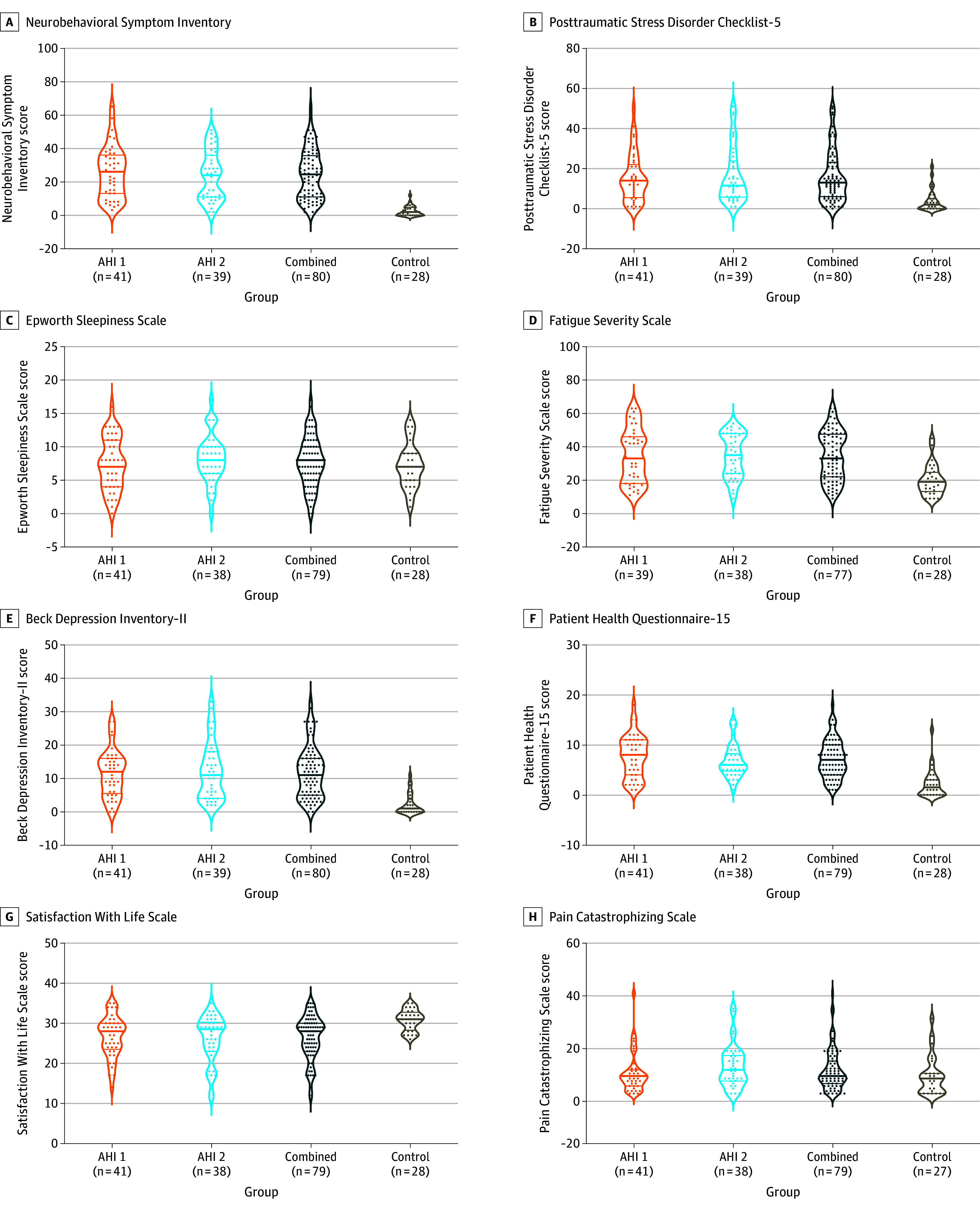

Figure 3. Self-Reports Based on Questionnaire.

All data shown were collected during the initial visit to the National Institutes of Health (median, 76 days [IQR, 30-537]) after the most recent anomalous health incident (AHI). See Figure 2 legend for details regarding interpretation of plots and P values. The self-reported (a paper-based questionnaire) measures in the AHI group compared with the vocationally matched US government control participants are shown. A higher score for all the self-report tests indicates worse performance except for Satisfaction With Life Scale, where a lower score means worse quality of life. For the combined vs control groups, P < .001; AHI 1 vs control groups, P < .001; and AHI 2 vs control groups, P < .01 for panels A, B, D, E, F, and G. There were no significant differences for any comparisons in panels C and H (P > .05).

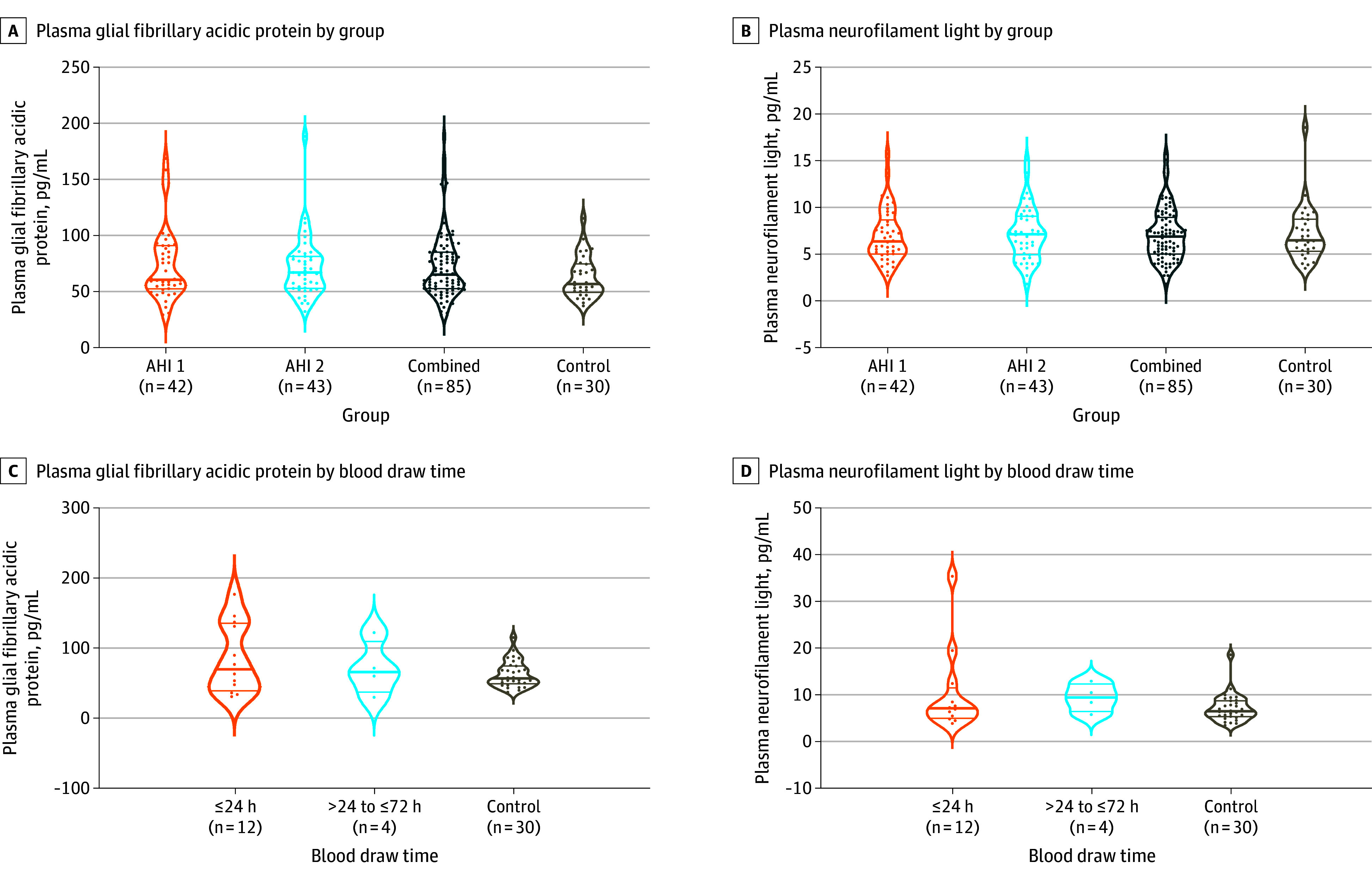

Figure 4. Blood Biomarkers of Neuronal Injury.

Glial fibrillary acidic protein (A) and neurofilament light chain (B) measured in plasma at initial visit to the National Institutes of Health (median, 76 days [IQR, 30-537]). See the Figure 2 legend for details regarding interpretation of plots. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups after correcting for multiple group comparisons using the Šidák method (groupwise) and Tukey Honestly Significant Difference (pairwise). In individuals who had acute blood draw, glial fibrillary acidic protein levels (C) and neurofilament light chain levels (D) in plasma also did not differ significantly between the anomalous health incident (AHI) and control groups.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 152 individuals (108 with AHIs and 44 US government control participants) were referred to the NIH between June 2018 and November 2021 (Figure 1; eTable 5 in Supplement 1). Of these, 86 participants with AHIs (42 women and 44 men; mean [SD] age, 42.0 [9.1] years) and 30 control participants (11 women and 19 men; mean [SD] age, 43.8 [10.1] years) were included in the final analyses. Age, sex, and education were similar between the AHI and control groups (Table). Participants with AHIs were evaluated a median of 76 days (IQR, 30-537) from the most recent incident (Table). Forty-three of the individuals were categorized as AHI 1 (consistent with core characteristics) and 43 were categorized as AHI 2 (not consistent with core characteristics) (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). Headache was the most common symptom (74%) following AHI, followed by cognitive challenges (69%), sleep disorders (59%), tinnitus (56%), imbalance (52%), dizziness (37%), and vision change concerns (37%) (Table). The most common type of headache was migraine headache (36%), followed by new daily persistent headache (29%), and unspecified headache (19%; mostly transient headache following AHI). Physical and neurological examinations were largely normal with incidental findings (eg, peripheral neuropathy), and functional signs of balance and gait disturbance, predominantly in those with PPPD. The AHI group was also separated based on location of the AHI (eTable 7 in Supplement 1). Relevant medical conditions identified in the AHI cohort and control participants are listed in the Table. Of note, 3 individuals with AHIs had cancer (different types and affecting different organs) identified while in the study. No individuals with AHIs developed multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, or other neurodegenerative conditions based on our follow-up data. Of 86 participants with AHI, 24 (28%) had a functional neurological disorder (22 PPPD, 1 functional sensory disorder, 1 functional voice disorder; Table).

Neuropsychological

Six of the participants in the AHI group and 2 in the control group who did not pass performance validity tests were excluded (page 6 of Supplement 1). There were no significant differences across all 3 groups (AHI 1, AHI 2, and controls), as well as between the AHI and control groups in the WAIS-IV Full Scale IQ (median, 116.0 [IQR, 109.0-124.0] vs 125.0 [IQR, 111.8-130.2]; P = .61), executive function (median, 51.0 [IQR, 45.5-56.1] vs 53.5 [IQR, 46.5-57.5]; P = .52), processing speed (median, 50.5 [IQR, 43.0-56.0] vs 54.0 [IQR, 47.0-59.0]; P = .17), perceptual (median, 53.0 [IQR, 47.0-60.0] vs 56.0 [IQR, 48.5-62.0]; P = .70) and verbal (median, 56.0 [IQR, 51.0-61.0] vs 56.0 [IQR, 50.8-60.3]; P > .99) reasoning, or working (median, 50.0 [IQR, 43.8-59.3] vs median, 54.0 [IQR, 44.0-64.0]; P = .57), immediate (median, 55.7 [IQR, 51.5-60.8] vs 58.5 [IQR, 50.3-62.3]; P = .88), and delayed (median, 58.3 [IQR, 53.0-62.0] vs 60.8 [IQR, 54.5-62.9]; P = .58) memory (Figure 2; eTable 8 in Supplement 1).

Individuals with AHIs reported significantly more posttraumatic stress (median, 13.0 [IQR, 6.0-22.0] vs 2.0 [IQR, 0.0-5.0]; P < .001), fatigue (median, 33.0 [IQR 21.0-47.0 vs median, 18.0 [IQR 12.3-23.5]; P < .001), and depressive (median, 11.0 [IQR, 5.0-16.0] vs 1.0 [IQR, 0.0-3.3]; P < .001) symptoms, as well as reduced satisfaction with life (median, 28.0 [IQR, 23.5-30.0] vs 31.0 [IQR, 28.8-32.3]; P < .001) compared with control participants; however, there was no significant evidence of pain catastrophizing (Figure 3; eTable 8 in Supplement 1). When clinical cutoffs were applied, 19% fulfilled the criteria for depression and 11% for posttraumatic stress disorder (Table). Eleven participants (12.8%) without functional neurological disorders reported significantly elevated somatic symptoms (eTable 16 in Supplement 1).

Ophthalmology

All participants with AHIs had an extensive ophthalmologic examination. Most of these examinations were unremarkable including acuity, pupils, Humphrey visual fields, extraocular eye movements, slit lamp, and dilated fundus assessments. No significant strabismus or lens changes were noted. Those cataracts noted were consistent with age-related changes and did not impact visual acuity. Eye examination findings included 6 participants (7%) with convergence insufficiency, 1 (1%) with hydroxychloroquine adverse effects, 2 (2%) with mild saccadic pursuit, 1 (1%) with ocular flutter, and 2 (2%) with visual field defects. Control participants did not have visual concerns warranting ophthalmologic evaluation.

Auditory

There were no statistically significant differences between the AHI vs control groups or the AHI 1 vs AHI 2 vs control groups in pure tone thresholds (250-8000 Hz) for the worse hearing ear (eFigure 1A in Supplement 1), auditory brainstem response latencies (eFigure 1B in Supplement 1), or frequency following response characteristics. Three auditory processing tests survived within-test multiplicity adjustment (eTable 9A and eFigure 1C in Supplement 1): duration pattern sequence of the right ear (AHI: median, 29.0 [IQR, 27.0-30.0] vs controls: median, 30.0 [IQR, 29.0-30.0]; P = .01) and left ear (AHI: median, 29.0 [IQR, 27.0-30.0] vs controls: median, 30.0 [IQR, 29.0-30.0]; P = .002); gaps in noise of the right ear (AHI: median, 42.0 [IQR, 37.0-44.0] vs controls: median, 44.0 [IQR, 41.0-46.0]; P = .03) and left ear (AHI: median, 40.0 [IQR, 35.0-44.0] vs controls: median, 43.0 [IQR, 39.3-46.8]; P = .002); and SCAN auditory figure ground (AHI: median, 10.0 [IQR, 8.0-11.0] vs controls: median, 10.0 [IQR, 10.0-12.0]; P = .04). The differences in the overall profile of hearing loss in each group were not statistically significant (eFigure 1A in Supplement 1). When compared with normative data, reduced performance on tests of auditory processing occurred at the same rate across groups, except for the gaps in noise test for the right ear where 15% of the AHI group had reduced performance compared with 0% of the control participants, and 27% of the AHI 2 group had reduced performance compared with 3% of the AHI 1 group (eFigure 2, eTables 9-10 in Supplement 1).

Ocular Motor and Vestibular

There were no statistically significant differences between participants with AHIs and control participants or between individuals in the AHI 1 and AHI 2 groups for any vestibular variable or for each composite vestibular severity score (rotational, otolith, vestibular) (eTables 11-14 and eFigures 3-5 in Supplement 1). Only 4 ocular motor variables (4.8%) survived within-test multiplicity adjustment (eTable 11A and eFigure 3A in Supplement 1); low-frequency (0.1 Hz) smooth pursuit latency (AHI: median, 260 ms [IQR, 210.0-330.0] vs controls: median, 225 ms [IQR, 190.0-270.0]; P = .04) and saccadic pursuit (AHI: median, 13.5% [IQR, 6.3%-25.2%] vs controls: median, 7.7% [IQR, 3.0%-13.0%]; P = .03), motor response latency for leftward target displacements (AHI: median, 0.48 seconds [IQR, 0.40-0.57] vs controls: median, 0.40 seconds [IQR, 0.35-0.49]; P = .03), and vertical saccadic peak eye velocity area (AHI: median, 9240 degrees [IQR, 8606-10 034] vs controls: median, 10 049 degrees [IQR, 9344-10 612]; P = .006).

Balance

Participants with AHIs scored worse on self-reported balance questionnaires, including the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (median, 12.0 [IQR, 2.0-30.0] vs 0.0 [IQR, 0.0-0.0]; P < .001), and Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale (median, 95.0 [IQR, 83.0- 99.0] vs 99.4 [IQR, 98.0-100.0]; P < .001). Scores on the clinician-rated Functional Gait Assessment were also worse (median, 28.0 [IQR, 25-29] vs 30.0 [IQR, 29.0-30]; P < .001) compared with control participants; however, there were no statistically significant differences in these tests between AHI 1 and AHI 2 (eFigure 6; eTable 14 in Supplement 1). The proportion of participants with AHIs scoring worse than age-referenced norms33 was 28% on the Limits of Stability–maximum excursion composite, 26% for the SOT vestibular test, 14% for the SOT somatosensory test, 13% for the SOT visual test, and 12% for the SOT composite scores; however, these measures did not differ significantly between the AHI 1 and AHI 2 groups (eFigure 7 in Supplement 1).

Plasma Biomarkers

The median time from initial event to initial blood draw was 76 days (IQR, 28-529). Initial differences in GFAP (median, 65.1 pg/mL [IQR, 52.7-85.1]) compared with control participants (median, 56.8 pg/mL [IQR, 49.3-74.7]; P = .053) did not survive adjustment for multiplicity testing (Figure 4A; eTable 15 in Supplement 1). The differences in the levels of NfL between participants with AHIs (median, 6.9 pg/mL [IQR, 5.0-8.8]) and control participants (median, 6.5 pg/mL [IQR, 5.4-8.6]; P = .96) were smaller than the magnitude for statistical significance (Figure 4B; eTable 15 in Supplement 1). Among the 12 participants with AHIs who had acute blood draw (defined as within 24 hours) and the 4 with subacute blood draw (defined as more than 24 hours but within 72 hours), the plasma NfL and GFAP values did not differ significantly from control participants (Figure 4C and D). There were 2 participants with AHIs who had pre-AHI blood samples, and GFAP and NfL levels were increased in 1 of the 2 individuals following AHIs and subsequently returned to baseline (eFigure 8 in Supplement 1).

Analysis by Geography

There were no differences in our assessments of neuropsychological (eTable 17 in Supplement 1), audiology (eTable 18 in Supplement 1), vestibular (eTable 19 in Supplement 1), or plasma (eTable 20 in Supplement 1) biomarkers based on the locations where AHIs occurred.

Individual-Level Differences and Associations Between Clinical and Imaging Findings

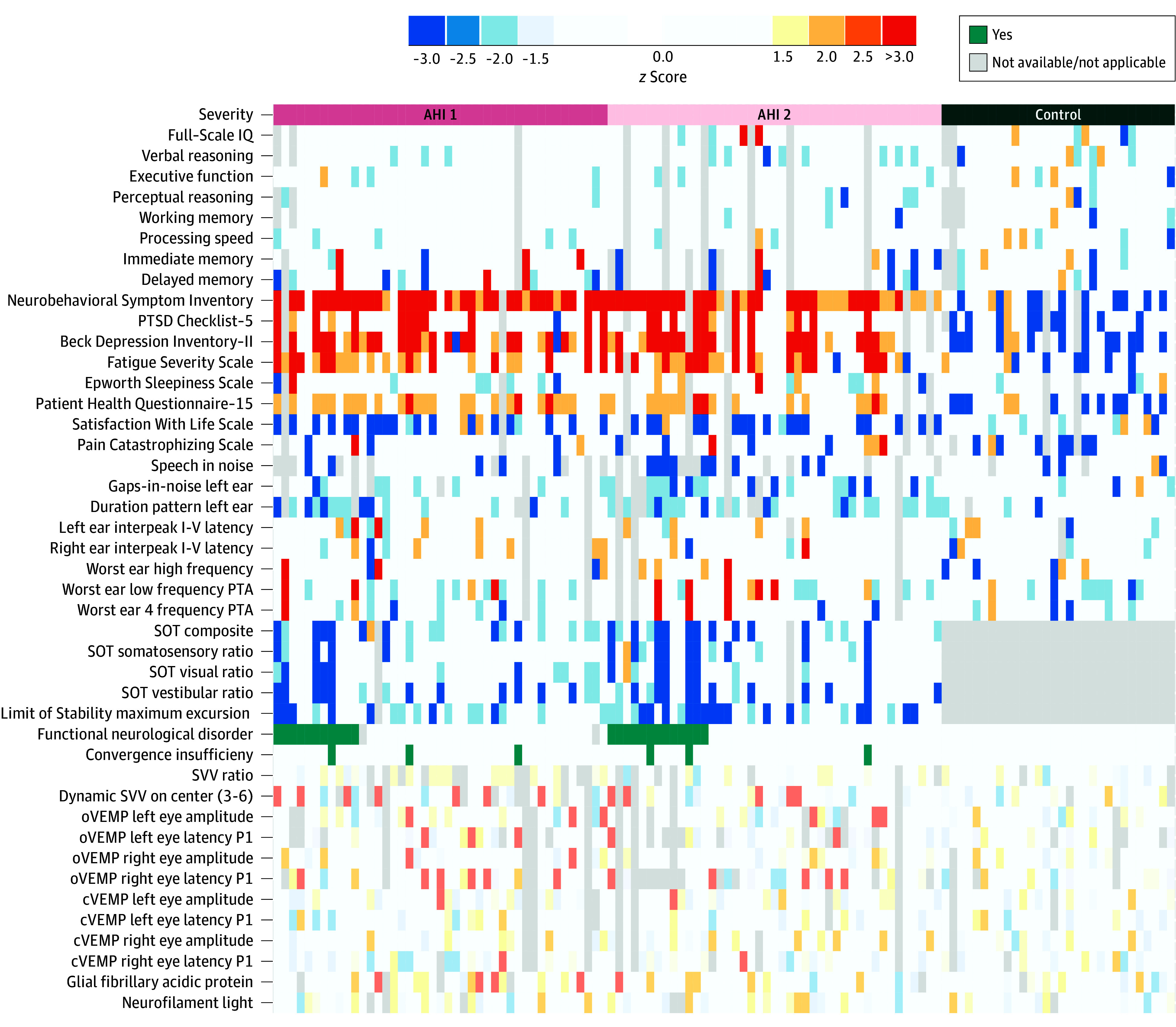

Figure 5 shows individual patient-level differences in a heat map relative to control participants. We also included the differences across these tests within the control group for comparison (eTable 21 in Supplement 1). The heat map indicates predominance of neurobehavioral, fatigue, posttraumatic stress, and balance symptoms in both AHI 1 and AHI 2 (deeper colors moving horizontally), while the differences in objective tests between the AHI 1 and AHI 2 and control groups are more scattered.

Figure 5. Summary Measures of the Blood Biomarkers, Vestibular, Balance, Hearing, and Self-Reported Symptoms and Neuropsychological Measures Across Individual Participants.

The 86 patients with anomalous health incidents (AHIs) are organized horizontally by AHI risk stratification: those consistent with core characteristics (AHI 1; left), those not consistent with core characteristics (AHI 2; middle), and then 30 vocationally matched US government control participants (right). Each group is further stratified by the presence of functional neurological disorders. The colors represent the differences between the participants with AHIs and the vocationally matched US government control group, as well as differences within the control group, with all findings from −1.5 to +1.5 z scores in white. The warmer colors indicate positive direction, and the cooler colors indicate negative direction. The z scores were calculated from percentile using the inverse normal rank transformation28 (page 25 in Supplement 1); all are based on the control group normed to 0. The data displayed in the heat map is from the initial visit to the National Institutes of Health (median, 76 days [IQR, 30-537] after most recent AHI). Light gray colors indicate not applicable or not available data point. For the balance data (all Sensory Organization Test [SOT] test and limit of stability), the individual differences were calculated compared with published normative data set (eTable 21 in Supplement 1). cVEMP indicates cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potential; oVEMP, ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potential; PTA, pure tone average; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; and SVV, subjective visual vertical.

Additionally, the correlations between previously reported brain magnetic resonance imaging regions of interest12 and the clinical assessments were assessed. Except for high correlations in expected comparisons (eg, example tests of immediate and long-term memory), correlations between different measures were weak (Spearman ρ ≤ 0.4; eFigure 9 in Supplement 1). Also, the correlation between time since the AHI and these various assessments were weak (Spearman ρ ≤ 0.3; eFigure 9 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this exploratory analysis of individuals with AHIs and matched control participants, the AHI cohort was not significantly different than the unaffected, matched comparison group in most of the assessments. These findings included clinical assessments of hearing, vision, ocular motor, cognitive function, vestibular function, and blood biomarkers as well as imaging (reported in the companion article17). These findings persisted when cases were analyzed by location of the AHIs and whether they fit the core characteristics of an AHI outlined by IC. There were also no significant correlations in related assessments as one might expect if the vestibular nerve or a specific region of the brain were consistently injured from one case to the next.

There were exceptions to these findings. First, the AHI group reported worse balance abnormalities than control participants, although this difference was certainly impacted by the presence of PPPD (almost all individuals with PPPD had abnormal Functional Gait Assessment scores). This should not be surprising because PPPD, thought to be a brain network dysfunction,34 is a common form of functional dizziness and is typically triggered by a transient vestibular disturbance or distressing episodes. It is also important to note that abnormal balance test results are not diagnostic and do not necessarily imply there has been damage to the central nervous system. Second, although few individuals fulfilled screening criteria for a formal diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder or depression when clinical cutoffs were applied, the AHI cohort expressed significantly higher posttraumatic stress disorder and depressive symptoms than the control participants. This increase is understandable given the unknown source of the symptoms, unclear prognosis, and the current media narrative that AHIs lead to brain injury.

Although the groupwise analyses failed to show significant differences in most measures, there were some specific findings that are worthy of note. First, the fact that there was little difference in the findings between the AHI 1 and AHI 2 groups suggests that the core characteristics of an AHI, currently used by some in the IC, should be used with caution. Second, 1 of 2 patients who had a baseline assessment prior to deployment overseas had transient elevations of plasma GFAP and NfL following an AHI. While these findings might suggest nervous system injury, this was observed in only 1 patient and little is known about the impact of other factors (eg, stress, dehydration, migraine headaches, COVID-19, and major depression) on the levels of GFAP and NfL.35 Third, headache was a common concern among participants with AHIs, where most developed new daily persistent headaches, and only 8 cases were diagnosed with new-onset migraines. This is important because headaches, especially migraines, could produce symptom clusters similar to some of the AHI cases, albeit the etiology could be different in these instances.36

While this study does corroborate the high rates of depression, fatigue, cognitive, and balance concerns found by other researchers,4,11,12,13,14,15,16 consistent neuropsychological, ocular motor, vestibular,13,14 or imaging abnormalities were not found.12 This discrepancy could be due to a combination of methodological and comparison group differences including the ability in the current study to recruit a vocationally matched control group.

The absence of a consistent set of abnormalities among any group in the AHI cohort suggests several things. First, if a directed energy “attack” is truly involved, it seems to create symptoms without persistent or detectable physiologic changes.2 A lack of evidence for a brain injury does not necessarily mean that no injury is present or that it did not occur at the time of the AHI. It is also possible that those with AHIs may be experiencing the results of an injury that led to PPPD and other symptoms but is no longer detectable. Alternatively, the “attack’s” physiological effects might be so varied and idiosyncratic that they cannot be identified with the current methodologies and sample size.

On the other hand, if a directed energy “attack” is not involved in the AHI cases or involved in just a few, then it is likely that the functional disorders identified may explain some of the study findings. The individuals in this cohort live in a high-stress environment and communicate frequently, which would seem an ideal circumstance for the spread of functional disorders. Some of the findings support this notion. Forty-one percent of the participants in the AHI cohort met the criteria for functional neurological disorder and/or had significant somatic symptoms.18 These cases occurred in both AHI groups and in patients from nearly every geographic location.37

It is important to note that functional neurological disorder may be the result of neurological injury and that these individuals have symptoms that are genuine, distressing, and can be quite prolonged, disabling, and difficult to treat. Efforts should be made to protect the at-risk workforce against these conditions by addressing the factors that contribute to their development, including moderating official expressions of concern to reflect an appropriate sense of risk.37

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, selection bias may have been an issue because every individual reporting an AHI was not evaluated. However, given the referral structure used for this study, many of the IC’s most concerning cases were likely enrolled. Second, recall bias may have been induced by contact between individuals as well as official communications alerting staff to be vigilant about certain symptoms. Third, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and pain can affect balance, vestibular, ocular motor, auditory processing, and cognitive testing, making abnormalities in these domains difficult to interpret. Fourth, some of the assessments used are sensitive but not specific and others are not yet in clinical use. Fifth, as an exploratory study, many domains were assessed, and the assessments were not blinded. Given the high number of tests administered, several significant differences by chance alone would be expected. Sixth, no formal psychiatric evaluations of participants with AHIs were performed. Seventh, the assessment of mass psychogenic illness was beyond the scope of this investigation. Eighth, other than assessment of 2 blood biomarkers, direct measurements of molecular or cellular function were not able to be performed. Ninth, many of the patients enrolled from 2018 through 2019 were seen months to years after their AHIs and some had experienced prolonged treatment, including convergence, vestibular, and balance training. Although this may have affected the study results, most of the patients were recruited from 2020 through 2021 and were seen within days to weeks of their AHIs, before treatment began. Thus, assessment of participants with AHIs at earlier time frames might produce different results.

Conclusions

In this exploratory study, there were no significant differences between individuals reporting AHIs and matched control participants with respect to most clinical, research, and biomarker measures, except for objective and self-reported measures of imbalance and symptoms of fatigue, posttraumatic stress, and depression. This study did not replicate the findings of previous studies, although differences in the populations included and the timing of assessments limit direct comparisons.

eMethods

eTable 1. I-PAS (Dx100) Assessment Battery

eTable 2. Applied Normative Reference Ranges

eTable 3. Rotational Vestibular Assessment Battery

eTable 4. VEMP Assessment Battery

eResults

eTable 5. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the AHI Participants

eTable 6. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the AHI Participants by Core Characteristics

eTable 7. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Participants

eTable 8. Comparison of Neurocognitive Measures Across AHI and Controls

eTable 9. Audiology Results – Comparison of Control and AHI Groups

eTable 10. Interpretation of Audiology Results – Comparison of Control and AHI Groups

eFigure 1. Comparison of AHI and Control Groups on Measures of Auditory Function

eFigure 2. Interpretation of Audiology Findings for the Control and AHI Groups on Measures of Auditory Function

eTable 11. Comparison of Ocular Motor (I-Pas/Dx100) Measures Across AHI and Controls

eFigure 3. Ocular Motor and Vestibular Findings

eFigure 4. Ocular Motor and Vestibular Findings

eTable 12. Comparison of Vestibular Measures Across AHI and Controls

eFigure 5. Rotational Findings

eTable 13. AHI VEMP Abnormalities

eFigure 6. Balance Findings

eFigure 7. Sensory Organization Test Findings

eTable 14. Comparison of Self-Report Balance Measures Across AHI and Controls

eFigure 8. Neuronal Injury Biomarkers

eTable 15. Comparison of Plasma Biomarkers Across AHI and Controls

eTable 16. Functional and Somatic Symptoms

eTable 17. Comparison Neurocognitive Measures Across Location

eTable 18. Comparison of Audiology Measures Across Location

eTable 19. Comparison of Ocular Motor and Vestibular Measures Across Location

eTable 20. Comparison of Plasma Biomarkers Across Location

eFigure 9. Correlation Between Clinical and Imaging Variables in AHI Patients

eTable 21. Scale Definition for Heatmap

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.US Department of State . Anomalous health incidents and the Health Incident Response Task Force. November 5, 2021. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.state.gov/anomalous-health-incidents-and-the-health-incident-response-task-force/

- 2.Relman DA, Pavlin JA, eds; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences; Standing Committee to Advise the Department of State on Unexplained Health Effects on US Government Employees and Their Families at Overseas Embassies . An assessment of illness in US government employees and their families at overseas embassies. 2020. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/25889/an-assessment-of-illness-in-us-government-employees-and-their-families-at-overseas-embassies [PubMed]

- 3.Office of the Director of National Intelligence . Executive summary. February 1, 2022. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/2022_02_01_AHI_Executive_Summary_FINAL_Redacted.pdf

- 4.Friedman A, Calkin C, Adams A, et al. Havana syndrome among Canadian diplomats: brain imaging reveals acquired neurotoxicity. medRxiv. Preprint posted online September 29, 2019. doi: 10.1101/19007096 [DOI]

- 5.JASON, Mitre Corp . An analysis of data and hypotheses related to the embassy incidents. February 10, 2022. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/JASON-Study-Revised_10-February-2022-Redacted_V1.1.pdf

- 6.Harris S, Ryan M. CIA finds no ‘worldwide campaign’ by any foreign power behind mysterious ‘Havana syndrome.’ Washington Post. January 20, 2022. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/cia-havana-syndrome-investigation-russia/2022/01/20/2f86d89e-795c-11ec-bf97-6eac6f77fba2_story.html

- 7.Office of the Director of National Intelligence . Updated assessment of anomalous health incidents. March 1, 2023. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/Updated_Assessment_of_Anomalous_Health_Incidents.pdf

- 8.Bartholomew RE, Baloh RW. Challenging the diagnosis of ‘Havana syndrome’ as a novel clinical entity. J R Soc Med. 2020;113(1):7-11. doi: 10.1177/0141076819877553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bokat-Lindell S. Is ‘Havana syndrome’ an ‘act of war’ or ‘mass hysteria’? New York Times. October 26, 2021. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/26/opinion/havana-syndrome-disorder.html

- 10.Baloh RW, Bartholomew RE. Havana Syndrome: Mass Psychogenic Illness and the Real Story Behind the Embassy Mystery and Hysteria. Springer; 2020. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-40746-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson RL II, Hampton S, Green-McKenzie J, et al. Neurological manifestations among US government personnel reporting directional audible and sensory phenomena in Havana, Cuba. JAMA. 2018;319(11):1125-1133. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verma R, Swanson RL, Parker D, et al. Neuroimaging findings in US government personnel with possible exposure to directional phenomena in Havana, Cuba. JAMA. 2019;322(4):336-347. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balaban CD, Szczupak M, Kiderman A, Levin BE, Hoffer ME. Distinctive convergence eye movements in an acquired neurosensory dysfunction. Front Neurol. 2020;11:469. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffer ME, Levin BE, Snapp H, Buskirk J, Balaban C. Acute findings in an acquired neurosensory dysfunction. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2018;4(1):124-131. doi: 10.1002/lio2.231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green-McKenzie J, Shofer FS, Matthei J, Biester R, Deibler M. Clinical and psychological factors associated with return to work among united states diplomats who sustained a work-related injury while on assignment in Havana, Cuba. J Occup Environ Med. 2022;64(3):212-217. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aristi G, Kamintsky L, Ross M, et al. Symptoms reported by Canadians posted in Havana are linked with reduced white matter fibre density. Brain Commun. 2022;4(2):fcac053. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcac053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierpaoli C, Nayak A, Hafiz R, et al. ; NIH AHI Intramural Research Program Team; NIH AHI Intramural Research Program Collaborators . Neuroimaging findings in US government personnel and their family members involved in anomalous health incidents. JAMA. Published March 18, 2024. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.2424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Staab JP, Eckhardt-Henn A, Horii A, et al. Diagnostic criteria for persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): consensus document of the committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society. J Vestib Res. 2017;27(4):191-208. doi: 10.3233/VES-170622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society . The International Classification of Headache Disorders, Third edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629-808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-Porath Y, Tellegen A. MMPI-2-RF: Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 Restructured Form: Manual for Administration, Scoring, and Interpretation. University of Minnesota Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Fourth Edition. Pearson; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The Fatigue Severity Scale: application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(10):1121-1123. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cicerone KD, Kalmar K. Persistent postconcussion syndrome: the structure of subjective complaints after mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1995;10(3):1-17. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199510030-00002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489-498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561-571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikemoto T, Hayashi K, Shiro Y, et al. A systematic review of cross-cultural validation of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. Eur J Pain. 2020;24(7):1228-1241. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71-75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beasley TM, Erickson S, Allison DB. Rank-based inverse normal transformations are increasingly used, but are they merited? Behav Genet. 2009;39(5):580-595. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9281-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gelman A, Hill J, Yajima M. Why we (usually) don’t have to worry about multiple comparisons. J Res Educ Eff. 2012;5(2):189-211. doi: 10.1080/19345747.2011.618213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bürkner P-C. brms: An R package for bayesian multilevel models using stan. J Stat Software. 2017;80(1):1-28. doi: 10.18637/jss.v080.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sankoh AJ, Huque MF, Dubey SD. Some comments on frequently used multiple endpoint adjustment methods in clinical trials. Stat Med. 1997;16(22):2529-2542. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Šidák Z. Rectangular confidence regions for the means of multivariate normal distributions. J Am Stat Assoc. 1967;62(318):626-633. doi: 10.2307/2283989 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobson GP, Newman CW, Kartush JM. Handbook of Balance Function Testing. Singular Publishing Group; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castro P, Bancroft MJ, Arshad Q, Kaski D. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD) from brain imaging to behaviour and perception. Brain Sci. 2022;12(6):753. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12060753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinacker P, Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein as blood biomarker for differential diagnosis and severity of major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;144:54-58. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lampl C, Thomas H, Tassorelli C, et al. Headache, depression and anxiety: associations in the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2016;17:59. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0649-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sudkamp KM, Williams HJ, Jaycox LH, Dunigan M, Young S. Trauma in the US intelligence community: risks and responses. October 2022. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PEA1000/PEA1027-1/RAND_PEA1027-1.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eTable 1. I-PAS (Dx100) Assessment Battery

eTable 2. Applied Normative Reference Ranges

eTable 3. Rotational Vestibular Assessment Battery

eTable 4. VEMP Assessment Battery

eResults

eTable 5. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the AHI Participants

eTable 6. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the AHI Participants by Core Characteristics

eTable 7. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Participants

eTable 8. Comparison of Neurocognitive Measures Across AHI and Controls

eTable 9. Audiology Results – Comparison of Control and AHI Groups

eTable 10. Interpretation of Audiology Results – Comparison of Control and AHI Groups

eFigure 1. Comparison of AHI and Control Groups on Measures of Auditory Function

eFigure 2. Interpretation of Audiology Findings for the Control and AHI Groups on Measures of Auditory Function

eTable 11. Comparison of Ocular Motor (I-Pas/Dx100) Measures Across AHI and Controls

eFigure 3. Ocular Motor and Vestibular Findings

eFigure 4. Ocular Motor and Vestibular Findings

eTable 12. Comparison of Vestibular Measures Across AHI and Controls

eFigure 5. Rotational Findings

eTable 13. AHI VEMP Abnormalities

eFigure 6. Balance Findings

eFigure 7. Sensory Organization Test Findings

eTable 14. Comparison of Self-Report Balance Measures Across AHI and Controls

eFigure 8. Neuronal Injury Biomarkers

eTable 15. Comparison of Plasma Biomarkers Across AHI and Controls

eTable 16. Functional and Somatic Symptoms

eTable 17. Comparison Neurocognitive Measures Across Location

eTable 18. Comparison of Audiology Measures Across Location

eTable 19. Comparison of Ocular Motor and Vestibular Measures Across Location

eTable 20. Comparison of Plasma Biomarkers Across Location

eFigure 9. Correlation Between Clinical and Imaging Variables in AHI Patients

eTable 21. Scale Definition for Heatmap

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement