Key Points

Question

Can a systematic evaluation using quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) metrics identify potential brain lesions in patients who have experienced anomalous health incidents (AHIs) compared with a well-matched control group?

Findings

In this exploratory study that involved brain imaging of 81 participants who experienced AHIs and 48 matched control participants, there were no significant between-group differences in MRI measures of volume, diffusion MRI–derived metrics, or functional connectivity using functional MRI after adjustments for multiple comparisons. The MRI results were highly reproducible and stable at longitudinal follow-ups. No clear relationships between imaging and clinical variables emerged.

Meaning

In this exploratory neuroimaging study, there was no significant MRI-detectable evidence of brain injury among the group of participants who experienced AHIs compared with a group of matched control participants. This finding has implications for future research efforts as well as for interventions aimed at improving clinical care for the participants who experienced AHIs.

Abstract

Importance

US government personnel stationed internationally have reported anomalous health incidents (AHIs), with some individuals experiencing persistent debilitating symptoms.

Objective

To assess the potential presence of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)–detectable brain lesions in participants with AHIs, with respect to a well-matched control group.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This exploratory study was conducted at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center and the NIH MRI Research Facility between June 2018 and November 2022. Eighty-one participants with AHIs and 48 age- and sex-matched control participants, 29 of whom had similar employment as the AHI group, were assessed with clinical, volumetric, and functional MRI. A high-quality diffusion MRI scan and a second volumetric scan were also acquired during a different session. The structural MRI acquisition protocol was optimized to achieve high reproducibility. Forty-nine participants with AHIs had at least 1 additional imaging session approximately 6 to 12 months from the first visit.

Exposure

AHIs.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Group-level quantitative metrics obtained from multiple modalities: (1) volumetric measurement, voxel-wise and region of interest (ROI)–wise; (2) diffusion MRI–derived metrics, voxel-wise and ROI-wise; and (3) ROI-wise within-network resting-state functional connectivity using functional MRI. Exploratory data analyses used both standard, nonparametric tests and bayesian multilevel modeling.

Results

Among the 81 participants with AHIs, the mean (SD) age was 42 (9) years and 49% were female; among the 48 control participants, the mean (SD) age was 43 (11) years and 42% were female. Imaging scans were performed as early as 14 days after experiencing AHIs with a median delay period of 80 (IQR, 36-544) days. After adjustment for multiple comparisons, no significant differences between participants with AHIs and control participants were found for any MRI modality. At an unadjusted threshold (P < .05), compared with control participants, participants with AHIs had lower intranetwork connectivity in the salience networks, a larger corpus callosum, and diffusion MRI differences in the corpus callosum, superior longitudinal fasciculus, cingulum, inferior cerebellar peduncle, and amygdala. The structural MRI measurements were highly reproducible (median coefficient of variation <1% across all global volumetric ROIs and <1.5% for all white matter ROIs for diffusion metrics). Even individuals with large differences from control participants exhibited stable longitudinal results (typically, <±1% across visits), suggesting the absence of evolving lesions. The relationships between the imaging and clinical variables were weak (median Spearman ρ = 0.10). The study did not replicate the results of a previously published investigation of AHIs.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this exploratory neuroimaging study, there were no significant differences in imaging measures of brain structure or function between individuals reporting AHIs and matched control participants after adjustment for multiple comparisons.

This study assesses whether participants with anomalous health incidents (AHIs) differ significantly from US government control participants with respect to magnetic resonance imaging–detectable brain lesions.

Introduction

US government personnel and their family members, mostly located internationally, have described unusual incidents of noise and head pressure often associated with headache, cognitive dysfunction, and other symptoms. These events have caused significant disruption in the lives of those affected and have been labeled anomalous health incidents (AHIs).1,2

A previous neuroimaging study3 of patients with AHIs from Havana, Cuba, reported significant differences with respect to control participants in brain volumes, diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) metrics, and functional connectivity. Taken together, these findings suggested detectable differences in the brains of those who experienced AHIs.

The main objective of the present study was to evaluate a broad range of quantitative neuroimaging features in participants with AHIs, taking advantage of the following factors: (1) a larger cohort of participants with AHIs, (2) a group of control participants that included US government personnel with similar professional backgrounds, (3) a dedicated dMRI sequence aimed at providing high accuracy and reproducibility, (4) an evaluation of the achieved reproducibility for volumetric and diffusion metrics, and (5) the availability of deep phenotyping (reported in a companion article4) for the assessment of clinical neuroimaging correlations.

Methods

Participants

The description of participant recruitment and inclusion/exclusion criteria are described in Figure 1 and Table 1. Briefly, participants located in Cuba, China, Austria, the United States, and other locations were recruited and evaluated at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in a natural history study between June 2018 and November 2022. The study was approved by the NIH Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent. A more detailed description about the study design and cohort can be found in our companion article.4

Figure 1. Flowchart of Inclusion in the Neuroimaging Study.

Summary of selection of participants for the anomalous health incident and control groups in the neuroimaging study. For the anomalous health incident group and the government employee control group, the top shows the inclusion information common with the clinical phenotyping study and the bottom shows information unique to the neuroimaging study. NIH indicates National Institutes of Health.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants in the Neuroimaging Study.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anomalous health incidents | Present before anomalous health incidenta | Present during or after anomalous health incidenta | US government control participants | NIH control participants | |

| No. | 81 | 29 | 19 | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 42.0 (9.1) | 44 (10.1) | 41 (12.7) | ||

| Sex, No. (%) | |||||

| Female | 40 (49) | 10 (34) | 10 (53) | ||

| Male | 41 (51) | 19 (66) | 9 (47) | ||

| Education from first grade, mean (SD), y | 17.0 (1.9) | 17.8 (1.9) | 17 (2.0) | ||

| US government employee family member | 10 (12) | NA | NA | ||

| Reduced capacity and/or unable to work due to anomalous health incidents | 25 (31) | ||||

| Time from first incident to research MRI acquisition, median (range), d | 80 (14-1505) | NA | NA | ||

| Sound or pressure | 70 (86) | NA | NA | ||

| Directionality and/or locality | 57 (66) | NA | NA | ||

| Symptoms | |||||

| Headache | 33 (38) | 60 (70) | 12 (41) | 11 (58) | |

| Sleep dysfunction | 11 (17) | 47 (60) | 1 (3) | 3 (16) | |

| Depression | 11 (14)b | 18 (22)b | 0c | 1 (5)c | |

| Vision changes | 9 (11) | 30 (37) | 0 | 0 | |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 7 (9)b | 7 (9)b | 0b | 0c | |

| Imbalance | 4 (5) | 43 (53) | 0 | 1 (5) | |

| Cognitive | 1 (1) | 55 (64) | 0 | 0 | |

| Dizziness | 1 (1) | 32 (37) | 0 | 0 | |

| Diagnoses | |||||

| Migraine headache | 22 (27) | 32 (39) | 2 (7) | 4 (21) | |

| Tinnitus | 13 (16) | 45 (55) | 0 | 0 | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 9 (11) | 11 (14) | 0 | 0 | |

| Cranial neuropathy | 5 (6) | 6 (7) | 0 | 0 | |

| Headache, unspecified | 4 (5) | 13 (16) | 12 (41) | 6 (32) | |

| Cancer | 3 (4) | 5 (6) | 0 | 0 | |

| Strabismus | 2 (2) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | |

| Seizure disorder | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 | |

| Functional neurologic disorder | 1 (1) | 20 (25) | 0 | 0 | |

| New daily persistent headache | 0 | 20 (25) | 0 | 0 | |

| Current cataract | 1 (1) | 21 (26) | 0 | 1 (5) | |

| Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | |

| Tension-type headache | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Data in these columns are not mutually exclusive. If a patient had symptoms or diagnoses before the anomalous health indecent and continued to have it after the anomalous health incident, they are counted in both columns.

Based on history and physical examination.

NIH control participants were administered the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist—Civilian and a cutoff of greater than 29 was used to indicate clinically significant posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms (https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL_handoutDSM4.pdf).

For the neuroimaging study, we included participants with an AHI and unaffected government employees with similar professional background as the participants who experienced AHIs. We also recruited additional healthy volunteers to reduce age and sex imbalance and to attain a larger normative group (Figure 1 and Table 1).

The participants with AHIs were further separated into categories (AHI 1 and AHI 2) based on criteria used by a US intelligence panel categorizing AHI incident modalities.5 AHI 1 is the category consistent with the 4 core characteristics of the incident as defined by the intelligence community, and AHI 2 is all other participants. Data from histories of participants with AHIs and Department of State Diplomatic Security Service investigations were used to assign participants to these AHI subgroups. The diagnoses of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD)6 were made when participants fully met specific criteria.

MRI Acquisition

All participants had a clinical scan and resting-state functional MRI (RS-fMRI) performed using a 3T Biograph mMR scanner (Siemens), except for 1 control participant scanned using a 3T Achieva scanner (Philips). Each clinical scan (including susceptibility-weighted imaging) (eAppendix 1.1 in Supplement 1) was read by a board-certified neuroradiologist, who had access to the clinical history of the participants. On a different day, participants had a structural and dMRI research scan performed using a 3T Prisma scanner (Siemens). Acquisition and preprocessing details of structural MRI,7,8 dMRI,9,10,11,12,13 and RS-fMRI14,15 are available in eAppendixes 1, 2, and 4, respectively, in Supplement 1. Extensive testing was performed to ensure the reproducibility of the structural and dMRI data (eAppendices 1.4 and 2.5 in Supplement 1).

The options to have follow-up visits with structural and dMRI scans was offered to all participants with AHI included in the imaging study at a yearly interval. However, participants were free to decline, and the schedule was flexible to accommodate individual availability (eAppendix 3.5 in Supplement 1).

Outcomes

We computed several neuroimaging metrics to evaluate group differences between participants with AHIs and control participants. From the structural volumetric MRI, we computed voxel-wise and regional brain volumes.7,8 From the dMRI, we computed diffusion tensor metrics9,13 (fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, axial diffusivity, and radial diffusivity), mean apparent propagator metrics11 (propagator anisotropy, return-to-axis probability [RTAP], return-to-origin probability, return-to-plane probability, and non-Gaussianity), and dual-compartment metrics11 (cerebrospinal fluid signal fraction and parenchymal mean diffusivity). From the fMRI, we computed functional connectivity14,15 within each large-scale network by averaging the unique pairwise correlations between only the regions of interest (ROIs) comprising the corresponding network. We did not assess any between-network connectivity, to be consistent with the analysis performed in a previous neuroimaging study3 of AHIs. See eAppendix 7 in Supplement 1 for a more detailed description of each of these outcome measures.

Data Analysis

Given the variability in clinical presentation, timing and modalities of the AHIs, the uncertainties regarding mechanism, spatial extent, and regional distribution of the potential injury, we conducted an exploratory data analysis. We developed a comprehensive analysis plan involving multiple statistical approaches (described in detail in eAppendices 3 and 5 in Supplement 1). These included conventional nonparametric analysis both with and without Benjamini-Hochberg16 adjustment for multiple comparisons, as well as bayesian multilevel modeling, which intrinsically addresses the issue of multiplicity in the conventional model.17

For the volumetric and dMRI data (eAppendix 3.3.1 in Supplement 1), an analysis approach based on percentiles was also developed to compare individual participants with respect to the median of the control distribution18 (eAppendixes 3.3.3 and 3.3.4 in Supplement 1).

For the group comparison of RS-fMRI data, we performed the Mann-Whitney U test, followed by Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment for 13 networks derived using the same atlas19 used by Verma et al3 (see eAppendix 4.3 in Supplement 1 for methods and eAppendix 5.1.1 in Supplement 1 for the bayesian approach). For the 3-group (AHI 1, AHI 2, and control participants) comparison, see eAppendix 5.1.2 in Supplement 1 for the conventional approach and eAppendix 5.1.3 in Supplement 1 for the bayesian approach.

We evaluated the correlation between 41 clinical measures and relevant neuroimaging metrics within specific ROIs where differences between the control participants and participants with AHIs were observed at an unadjusted level. This included the first 2 principal components (eAppendix 3.3.5 in Supplement 1) obtained from 8 diffusion MRI measurements within the white matter ROIs, mean diffusivity from the gray matter ROIs, normalized volume, and functional connectivity within specific networks (eAppendix 6.1 in Supplement 1). In addition, we also evaluated the possible relationship between functional connectivity and clinical measures pertaining to dysfunction in those networks, using linear regression (eAppendix 6.2 in Supplement 1).

All voxel-wise statistical analyses were performed using the nonparametric “randomize” module in FSL20 version 6.0 at an unadjusted threshold of P < .01 (2-sided). The ROI-wise statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.2.2)21 at an unadjusted threshold of P < .05 (2-sided).

Results

Participant Demographics

The number of participants included in the primary analysis and the relevant demographics are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. Of the 86 participants included in the clinical assessment, 81 participated in the neuroimaging study. Of the 30 control participants included in the clinical assessments, 29 participated in the neuroimaging study and 19 additional participants were recruited to improve the age and sex match of the control population with the AHI population. No significant differences in age and sex were observed across any participant groups, including the control group (mean [SD] age, 43 [11] years; 42% female) and the AHI group (mean [SD] age, 42 [9] years; 49% female) and the AHI subgroups (AHI 1: mean [SD] age, 40 [9] years; 48% female, and AHI 2: mean [SD] age, 44 [9] years; 51% female). Imaging scans were performed as early as 14 days after experiencing AHIs, with a median delay interval of 80 (IQR, 36-544) days and a range of 14 to 1505 days across the entire AHI sample. For the longitudinal scans, the data presented here included participants with AHI (n = 49, with at least 2 visits) up to a fixed date (November 7, 2022), with a median interscan interval of 371 (IQR, 298-420) days (eAppendix 3.5 in Supplement 1).

Clinical MRI Findings

The majority of the brain MRI scans were unremarkable as read by clinical neuroradiologists. No evidence of acute traumatic brain injury or hemorrhage was reported for any participant in the AHI or control group. The presence of gliosis, white matter hyperintensities abnormal for age, or small vessel ischemic changes were reported in 10.7% of participants with AHIs and 14.6% of control participants. Other incidental findings included, in order of decreasing frequency: sinusitis (n = 6 AHI, n = 2 control), retention cysts (n = 4 AHI, n = 1 control), developmental venous anomalies (n = 2 AHI, n = 1 control), and other congenital anatomical abnormalities (n = 2 AHI, n = 0 control) considered of little clinical relevance.

Reproducibility Analysis Findings

Four healthy volunteers underwent 5 repeated scans for the interscan reproducibility analysis (eAppendix 1.4.1, eTable 2 in Supplement 1). The coefficient of variation (averaged over 4 volunteers) across repeated scans for the structural volumetric data showed excellent reproducibility, with less than 1% coefficient of variation for the global ROIs (eg, total parenchyma = 0.5%, total gray matter = 0.6%, and cerebral white matter = 0.6%). The median coefficient of variation across all ROIs was 2.4% (IQR, 1.1%-3.2%) (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). The interscanner reproducibility of structural volumetric data (n = 110, eAppendix 1.4.2 in Supplement 1) between the Siemens Biograph mMR and the Siemens Prisma scanners was also high, with global ROIs exhibiting a very strong correlation (r ≈ 1) between the scanners (eg, total parenchyma [R2 = 0.99], cerebral white matter [R2 = 0.98], total gray matter [R2 = 0.98], cortical gray matter [R2 = 0.97]), and approximately 86% of ROIs showing an R2 greater than 0.7 (eAppendix 3.1.2, eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

For the same 4 healthy volunteers mentioned above, the dMRI metrics also demonstrated strong reproducibility (eAppendix 3.1.3, eTable 6 in Supplement 1). For instance, the median coefficient of variation across all white matter ROIs was approximately 1% for the diffusion tensor (eg, fractional anisotropy: 0.6% [IQR, 0.5%-0.8%]; mean diffusivity: 0.6% [IQR, 0.5%-0.7%]) and mean apparent propagator (eg, propagator anisotropy: 0.2% [IQR, 0.1%-0.4%]; RTAP: 1.3% [IQR, 1.1%-1.6%]) metrics.

Cross-Sectional Diffusion and Volumetric MRI Analysis

After adjustment for multiple comparisons, no statistically significant differences between participants with AHI and control participants were found for the whole-brain voxel-wise analysis or ROI-wise analysis for both the volumetric measurements and the dMRI metrics. Therefore, when we mention “significant” results in the remainder of this article, we refer either to significant results for the bayesian analysis or to “significant results at an unadjusted level” for the conventional analysis.

Figure 2A, Figure 3A, and Figure 4A show voxel-wise magnitude effect maps for volumetrics,23,24,25,26 mean diffusivity,10 and fractional anisotropy,10 respectively. Figure 2A shows a few regions with significantly higher volume (unadjusted) in participants with AHIs, with neither apparent anatomical pattern nor left-right consistency. No regions with significantly altered mean diffusivity were observed in the brain parenchyma (Figure 3A), whereas participants with AHIs exhibited significantly lower fractional anisotropy than control participants in the corpus callosum and in regions located at the interfaces between gray matter and sulci (Figure 4A), which could arise from inconsistent interparticipant registration. No regions with significantly higher fractional anisotropy in participants with AHIs were observed. In all 3 metrics mentioned above, no clusters survived after adjustment for multiple comparisons. Differences between participants with AHIs and control participants for all other diffusion metrics were small in both magnitude and spatial extent (eFigure 3A-G in Supplement 1), and no remarkable differences emerged in the analysis of the AHI 1 and AHI 2 subgroups vs control participants (eFigure 4A-W in Supplement 1).

Figure 2. Voxel-Wise Map of Group Difference for the Volumetric Measurements Between Participants With Anomalous Health Incidents and Control Participants and ROI-Wise Heat Map of Individuals.

A, Percentage magnitude-of-difference map for volumetric measurement between 81 participants from the group with anomalous health incidents (AHIs) and 48 control participants. Each voxel in this map is an estimate of how much the median volume of the group with anomalous health incidents changed, with respect to the median volume in the control group. The percentage magnitude map was computed from a composite of 81 volumetric maps from the anomalous health incident group and 48 images from the control group. However, the values shown in this map are only for the voxels that survived the unadjusted P < .01 (2-sided) threshold from the nonparametric randomized permutation test of difference between the 2 groups. Regions with blue shades indicate significantly smaller volume in the anomalous health incident group than in control participants, while red shades indicate larger volume compared with control participants. The sagittal slice (top right) with green lines traversing from the anterior to the posterior plane of the brain is a reference to the locations of the axial slices shown. The map was superimposed on the JHU-ss-MNI atlas.22 B, Heat map of the volumetric measurement for participants with AHIs and control participants. The participants with AHIs are sorted by increasing time (in days) after AHIs. Control participants are not sorted. The dashed vertical line separates the participants from each group. Darker shades of blue and red in the color bar represent extreme negative and positive values, respectively. The P scores are comparable to z scores; therefore, an individual in the greater than 3 range (approximately) would correspond to a z score of greater than 3 from a normal distribution and vice versa for a dark blue shade. In the key, “(“ indicates a P score has values greater than the number next to it, whereas “]” indicates that the value is inclusive; eg, the label “(>2.33,3]” represents values in the range “2.33 < z ≤3” and so on for others. ROI indicates regions of interest.

Figure 3. Voxel-Wise Map of Group Difference for the Mean Diffusivity Measurements Between Participants With Anomalous Health Incidents and Control Participants and ROI-Wise Heat Map of Individuals.

A, Analysis similar to that shown in Figure 2A, but the map illustrates mean diffusivity from diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (unadjusted P < .01, 2-sided). At the chosen threshold, no voxels survive, but blue areas would represent regions with lower diffusivity in the anomalous health incident (AHI) group than in control participants, while red areas would correspond to regions with higher diffusivity compared with control participants. The map was superimposed on the average T1-weighted image of the population. B, Analysis similar to that shown in Figure 2B, but the heat map illustrates mean diffusivity. Some individual striations of red and blue are also apparent, with no systematic patterns across regions of interest (ROI). See Figure 2B legend for explanation of key.

Figure 4. Voxel-Wise Map of Group Difference for the Fractional Anisotropy Measurements Between Participants With Anomalous Health Incidents and Control Participants and ROI-Wise Heat Map of Individuals.

A, Analysis similar to that shown in Figure 2A, but the map illustrates fractional anisotropy from diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (unadjusted P < .01, 2-sided). Some clusters can be seen in the corpus callosum with small magnitude of difference (≈2%), where the anomalous health incident (AHI) group showed lower anisotropy compared with the control group. B, Analysis similar to that shown in Figure 2B, but the heat map illustrates fractional anisotropy. Some individual striations of red and blue are also apparent with no systematic patterns across regions of interest (ROI). See Figure 2B legend for explanation of key.

Table 2 summarizes the group-level ROI-wise analysis results for potential volumetric and dMRI outcomes of interest in ROIs where a difference was observed at an unadjusted threshold (P < .05, 2-sided) and a percentage difference in medians was at least 2%. The highest magnitude difference for volumetric and diffusion metrics was less than 8%. Compared with control participants, the corpus collosum at the midsagittal plane in participants with AHIs had 7% larger volume and lower RTAP (ie, increased diffusivity perpendicular to the fibers). The RTAP differences were statistically significant but of small magnitude, ranging from 2% to 7% depending on the analysis used. Decreased RTAP is in line with the reduction of fractional anisotropy found in several clusters in the corpus collosum at the voxel-wise analysis. In addition, the right superior longitudinal fasciculus showed decreased RTAP and fractional anisotropy in participants with AHIs compared with control participants, albeit with small magnitude differences (≈3%).

Table 2. ROI-Wise Group Differences From Statistical Analysis of MRI-Derived Metrics.

| Region of interesta | MRI metric | Median (IQR) | AHI vs control, difference in median, %b | Difference in location (95% CI)c | P value | Significant regions of interest that match with bayesian analysise | MRI metrics for significant regions of interest that match with bayesian analysisf | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHI (n = 81) | Control (n = 48) | AHI vs control, Mann-Whitney, unadjustedd | AHI vs control, Mann-Whitney, Benjamini-Hochberg–adjusted | ||||||

| Genu of the corpus callosum | RTAP | 0.0504 (0.0466 to 0.0566) |

0.0543 (0.0489 to 0.0590) |

−7.1 | −2.67e−03 (−5.14e−03 to −2.48e−04) |

.03 | .52 | ✓ | ✓ |

| RTOP | 1.01e-03 (9.33e-04 to 1.13e-03) |

1.08e-03 (9.87e-04 to 1.19e-03) |

−6.3 | −5.72e−05 (−7.04e−05 to −2.21e−05) |

.047 | .76 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Body of the corpus callosum | RTAP | 0.0482 (0.0452 to 0.0522) |

0.0509 (0.0464 to 0.0535) |

−5.5 | −1.98e−03 (−3.87e−03 to −7.29e−05) |

.04 | .52 | ✓ | ✓ |

| External capsule right | CSF-SF | 0.157 (0.147 to 0.169) |

0.165 (0.154 to 0.181) |

−5.3 | −9.14e−03 (−0.0159 to −2.50e−03) |

.006 | .38 | X | X |

| Superior longitudinal fasciculus right | Fractional anisotropy | 0.532 (0.512 to 0.553) |

0.549 (0.530 to 0.567) |

−3.1 | −0.0159 (−0.0270 to −4.58e−03) |

.006 | .32 | ✓ | X |

| Radial diffusivity, μm2/s | 476.77 (455.64 to 496.29) |

464.17 (446.44 to 482.70) |

2.7 | 11.07 (0.27 to 21.03) |

.047 | .90 | ✓ | X | |

| Superior longitudinal fasciculus left | Fractional anisotropy | 0.533 (0.516 to 0.547) |

0.544 (0.522 to 0.568) |

−2.0 | −0.0111 (−0.0219 to −5.12e−04) |

.04 | .58 | X | X |

| Cingulum cingulate gyrus right | RTAP | 0.0350 (0.0325 to 0.0374) |

0.0368 (0.0339 to 0.0385) |

−4.8 | −1.29e−03 (−2.63e−03 to −3.90e−05) |

.047 | .52 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Inferior cerebellar peduncle left | Axial diffusivity, μm2/s | 1291.05 (1253.76 to 1309.65) |

1264.86 (1234.69 to 1296.39) |

2.1 | 19.28 (2.02 to 37.96) |

.03 | .79 | X | X |

| CSF-SF | 0.215 (0.196 to 0.228) |

0.204 (0.186 to 0.221) |

5.4 | 9.39e−03 (2.10e−04 to 0.0179) |

.047 | .90 | X | X | |

| Mean diffusivity, μm2/s | 767.14 (750.41 to 785.36) |

750.63 (736.39 to 775.41) |

2.2 | 12.94 (2.38 to 22.85) |

.02 | .88 | X | X | |

| Corpus callosum midsagittal plane | Normalized volume | 0.262 (0.237 to 0.281) |

0.245 (0.228 to 0.266) |

7.1 | 0.012 (3.39e−04 to 0.025) |

.04 | .98 | X | X |

| Amygdala right | RTOP | 307.67 (300.57 to 317.56) |

315.42 (305.79 to 322.31) |

−2.5 | −4.41 (−9.52 to −0.04) |

.048 | .76 | ✓ | ✓ |

Abbreviations: AHI, anomalous health incident; CSF-SF, cerebrospinal fluid signal fraction; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ROI, region of interest; RTAP, return-to-axis probability; RTOP, return-to-origin probability.

Table shows regions with differences in quantitative volumetric and diffusion MRI metrics from the Mann-Whitney U (MW) test between control and AHI groups.

An estimate of how much the median of MRI metrics in participants with AHIs changed compared with the median in control participants. Computed as 100 × (median of AHI group – median of control group)/(median of control group).

A sample estimate from the Mann-Whitney U test that computed the median of the differences among all pairs of samples between the AHI and the control groups. Despite showing no significant differences after Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment, these results were highlighted to indicate potentially relevant outcome measures.

Column reports regions of interest that survived an unadjusted threshold of P < .05 (2-sided) and showed a minimum difference in median percentage of 2% or greater between the AHI and control groups.

The regions of interest that showed differences in both the nonparametric and the Bayesian analyses marked (check marks) for comparison.

The MRI metrics tested in these brain regions that matched with the Bayesian analyses were also marked (check marks) to showcase which of these potential regions of interest, and which of the MRI metrics tested, were likely to be significantly different between the AHI and the control groups if the strict penalty of multiple comparison adjustment was addressed by the Bayesian analysis.

Figure 2B, Figure3B, and Figure 4B show heat maps generated from the “Pscores”18 (eAppendixes 3.3.3 and 3.3.4 in Supplement 1), for volume, mean diffusivity, and fractional anisotropy, respectively. In these maps, since each column represents an individual, a vertical line of a given color indicates a consistent deviation from the median of the control participants in multiple brain regions for that individual. Conversely, the rows represent ROIs and a darker color in a row for the participants with AHIs and not for the control participants would suggest that ROI may be involved in the expression of AHI pathology. Moreover, a higher representation of darker colors in the group of participants with AHIs would indicate an increased presence of extreme values and therefore an increased likelihood of abnormalities in the AHI cohort. Overall, vertical striations related to interindividual differences were observed, while there were neither ROI-specific striations nor more extreme values in the AHI group, even across other diffusion metrics (eFigure 7, panels A-I in Supplement 1 for the AHI and control groups and eFigure 8, panels A-L in Supplement 1, which includes AHI subgroups).

To assess the dMRI differences between participants with AHIs and control participants globally in white matter, a principal component analysis was performed using percentiles averaged across all white matter ROIs from 8 diffusion metrics (eAppendix 3.3.5 in Supplement 1). The first 2 principal components explained more than 87% of the variance (eFigure 6B in Supplement 1). eFigure 9A in Supplement 1 shows the biplot from the principal component analysis revealing that the 95% confidence ellipses of participants with AHIs and control participants substantially overlap, indicating they have very similar global diffusion characteristics. A similar biplot including the AHI subgroups (AHI 1 and AHI 2) also shows that the 3 groups substantially overlap (eFigure 9B in Supplement 1).

Longitudinal Diffusion and Volumetric MRI Analysis

Among the individuals included in the longitudinal assessment (n = 49 [2 visits], n = 17 [3 visits], and n = 8 [4 visits]), the median interscan interval between the visits was 371 (IQR, 298-420) days (eAppendix 3.5 in Supplement 1). In the regions where differences between participants with AHIs and control participants were observed at an unadjusted level (P < .05) from the cross-sectional analysis of the first visit, the ROI measurements of the available follow-up visits were plotted. The volumetric and dMRI metrics in these ROIs showed very small changes across these follow-up visits (on average,<±1%), even for individuals with large deviations from the median of the control participants at the first visit (eFigure 10A-G in Supplement 1).

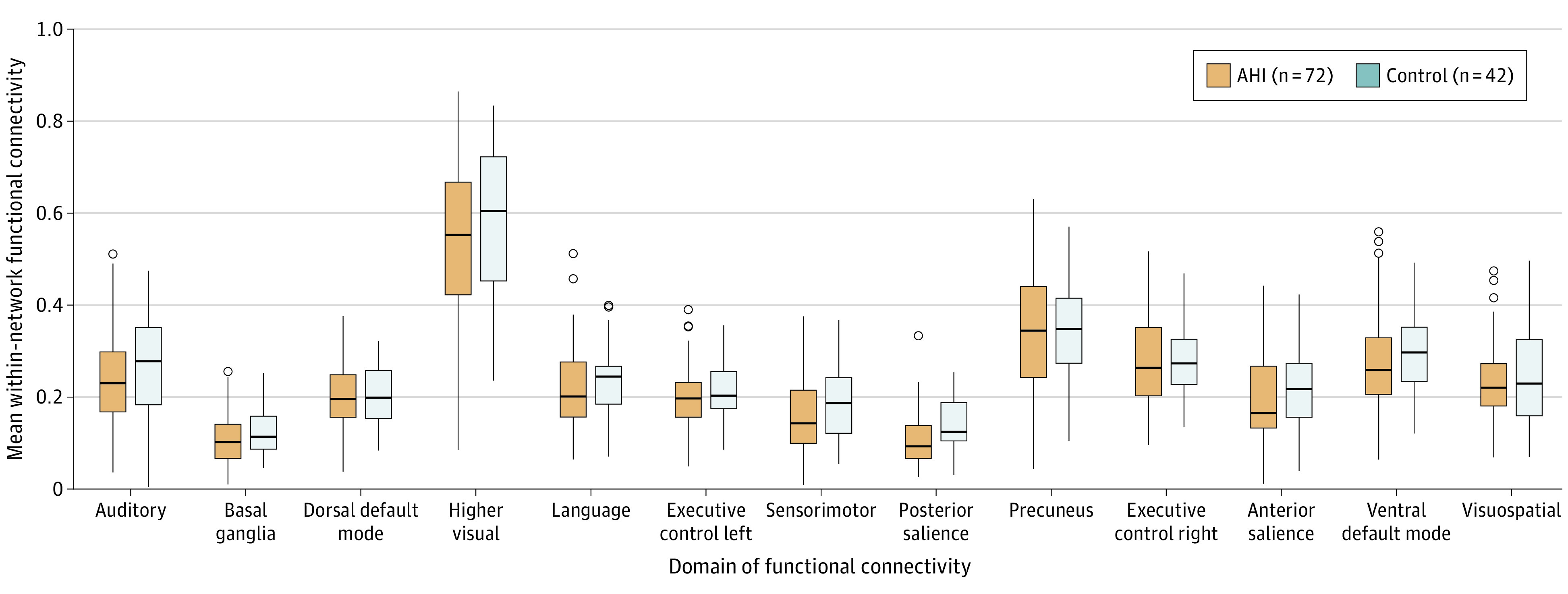

Within-Network Functional Connectivity Differences

Figure 5 shows box plots for the group of control participants and participants with AHIs for 13 resting-state networks. In general, control participants had a higher median functional connectivity in all resting-state networks compared with participants with AHIs; however, the only difference at an unadjusted level (P = .006; difference in location, −0.03 [95% CI, −0.05 to −0.01]) found in the posterior salience network did not survive Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment (P = .08). Stronger differences were observed between control participants and AHI 1 subgroup, within the posterior salience network (unadjusted P = .004; difference in location, −0.04 [95% CI, −0.06 to −0.01]; P = .03 after Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment) and the anterior salience network (unadjusted P = .002; difference in location, −0.06 [95% CI, −0.09 to −0.02]; P = .02 after Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment). See eAppendix 5.1.2 and eFigure 12 in Supplement 1 for more details on these analyses. The results from our conventional analysis also aligned with those from the Bayesian approach for both the 2-group comparison (eAppendices 5.1.1 and 5.1.3 in Supplement 1) and the 3-group comparison (eFigures 11 and 12 in Supplement 1).

Figure 5. Within-Network Functional Connectivity Between Control Participants and Participants With AHIs.

Within-network functional connectivity values (y-axis) were estimated by taking the mean of all correlations between each unique pair of region of interest (ROI) combinations comprising the corresponding large-scale resting-state networks (x-axis). For example, the posterior salience network consists of n = 12 ROIs. This would have ½ × n(n – 1) = 66 unique ROI-paired connections from which the mean functional connectivity was estimated. Horizontal lines within boxes indicate the medians in each group. Boxes indicate interquartile range; horizontal lines within boxes, median. Whiskers indicate the spread of functional connectivity values within each group, up to 1.5 times the interquartile range. Dots indicate more extreme values. Some evidence of less functional connectivity within the posterior salience network can be observed within participants with anomalous health incidents (AHIs) compared with control participants (Mann-Whitney P = .006); however, the difference is not strong enough to survive adjustment for multiple comparisons (Benjamini-Hochberg P = .08).

There was no significant relationship between functional connectivity in the salience networks and any of the clinical measurements reported in the companion article4 (eFigure 13 in Supplement 1), particularly including relationships with metrics assessing anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (eAppendix 6.2 and eFigure 15A-B in Supplement 1). Stratification of the participants into those diagnosed with PPPD and those without did not affect the functional connectivity findings (eFigure 14 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this exploratory neuroimaging study, after adjustment for multiple comparisons, there were no significant differences between participants with AHIs and control participants for any MRI modality. When we report significant differences between groups, these differences are either from an “unadjusted” analysis or from the Bayesian analysis. Global volumetrics, such as total gray matter and white matter volumes did not show any differences even in the unadjusted analysis or the Bayesian analysis. The principal component analysis of diffusion metrics across all white matter regions also showed an essential overlap of the median values for participants with AHIs and control participants. From these findings, it may be concluded that, from a structural MRI standpoint, there was no evidence of widespread brain lesions in the AHI group.

In the ROI-wise analysis, the corpus collosum at the midsagittal plane in participants with AHIs had larger volume than in control participants. This is the opposite of what would be expected in presence of axonal loss consequent to brain injury. Low anisotropy and increased diffusivity perpendicular to the fibers has been reported in Wallerian degeneration,27 but the small group differences we observed in the corpus collosum and the superior longitudinal fasciculus may not be indicative of pathology. Overall, the group-level analysis of structural and dMRI data revealed very small differences between participants with AHIs and control participants.

Lack of significant group differences may originate from a large heterogeneity in the response to the potential injury across individuals. The data were therefore also presented at the individual level using heat maps. These analyses indicated that the measurements were sensitive enough to detect differences across individuals, but they did not segregate into a clear pattern between participants with AHIs and control participants.

An important feature of this study was the longitudinal brain MRI scans, allowing evaluation of potential findings over time. This is especially important when there is a lack of predeployment brain MRI scans. Measurements across various MRI modalities were largely stable on the follow-up visits, even for participants with atypical values at initial scan, suggesting absence of evolving lesions. Lack of evolving lesions may indicate absence of an acute brain injury, since most injuries result in changes over time.

For the functional connectivity analysis, there were differences primarily in the salience networks, although most differences did not survive after adjustment for multiple comparisons. The primary regions comprising the salience networks (anterior salience, posterior salience) are the anterior and posterior insula, which are associated with sensorimotor, autonomic, emotion, and decision-making functions, among several other functions.28 The salience networks process prioritized attention stimuli and work as a switching hub between other large-scale resting-state networks such as the central executive networks (left and right executive control networks) and default-mode networks (posterior and dorsal default-mode networks).29,30 Abnormalities in salience networks have been seen in patients with functional neurologic disorders,31 but the lack of a relationship here with functional manifestations (PPPD) makes this finding of uncertain significance. Moreover, increased connectivity in the salience network has been associated with posttraumatic stress disorder32,33 and anxiety34; however, no such relationships were observed within the AHI cohort. This further adds to the uncertainty of the clinical relevance of these differences with respect to AHIs.

Even restricting the analysis to the more selective AHI 1 group, we did not find substantial differences between AHI and control groups, except for the functional connectivity in the salience networks noted above. These findings suggest that the current criteria used by the Intelligence Community Experts Panel to identify cases of interest do not correspond to distinct MRI patterns. That this study did not identify a neuroimaging signature of brain injury in this AHI cohort does not detract from the seriousness of the clinical condition.

A previous neuroimaging study3 reported significant differences with respect to control participants in regional white matter and gray matter volumes, decreased global white matter volume, decreased mean diffusivity in the cerebellar vermis, increased fractional anisotropy in the splenium of the corpus collosum, and reduced functional connectivity in the auditory and visuospatial subnetworks. The present study did not replicate any of the findings of the previous neuroimaging study on AHI for any MRI modality used.

For the dMRI component of the study, this lack of agreement could originate from experimental factors. dMRI is a powerful technique, but it is vulnerable to several potential artifacts, which may bias results.12,35 Because obtaining reliable quantitative dMRI measurements from clinical scans is problematic, we therefore had a dedicated dMRI session with an acquisition scheme designed to achieve high accuracy and reproducibility. Experimental factors, however, are unlikely to explain the lack of agreement for the volumetric and functional MRI findings. The authors of the previous study3 indicated that one limitation of their investigation was that it was not possible to obtain control participants who shared the same professional background of the exposed individuals. In this regard, the present study had a better-matched control cohort, although still with a small number of participants. An additional confounder in the previous study3 was that different MRI protocols were used to acquire data for 2 subsets of the control cohort. The occurrence of spurious systematic differences in advanced MRI findings when using different acquisition protocols is well documented in the literature.36,37,38,39 For both the previous3 and the present study, the sample size is relatively small, and it is difficult to assess the risk of having spurious positive and false-negative findings.40,41,42

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size of the control population was small, and not all control participants were matched vocationally to the participants with AHIs. On the other hand, control participants and participants with AHIs were well matched based on age and sex, and all participants were scanned with an identical imaging protocol. Second, the earliest scan for participants with AHIs was 14 days from the experienced event (median, 80 [IQR, 36-544] days; range, 14-1505 days), precluding the assessment of acute imaging abnormalities. Third, while the dMRI acquisition was designed to have very high quality, the fMRI acquisition was limited to more standard protocols. We also could not perform specific task-fMRI assessments that might help better characterize the fMRI correlates of clinical manifestations pertinent to this group. The RS-fMRI analysis was also limited to only intranetwork functional connectivity, while evaluations of both intranetwork and internetwork functional connectivity may be warranted for a comprehensive assessment.

Conclusions

This exploratory neuroimaging study, which was designed to produce highly reproducible quantitative imaging metrics, revealed no significant differences in imaging measures of brain structure or function between individuals reporting AHIs and matched control participants after adjustment for multiple comparisons. These findings suggest that the origin of the symptoms of participants with AHIs may not be linked to an MRI-identifiable injury to the brain.

eAppendix 1. Structural Volumetric and Clinical MRI

eAppendix 2. Structural Diffusion MRI

eAppendix 3. Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP)

eAppendix 4. Resting State Functional MRI (RS-fMRI)

eAppendix 5. Statistical Analysis for RS-fMRI

eAppendix 6. Assessing Relationship of Imaging Metrics With Clinical Measures

eAppendix 7. Outcome Metrics

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.US Department of State. Anomalous Health Incidents and the Health Incident Response Task Force. Published November 5, 2021. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://www.state.gov/anomalous-health-incidents-and-the-health-incident-response-task-force/

- 2.Office of the Director of National Intelligence of the National Intelligence Council . Updated Assessment of Anomalous Health Incidents. ICA 2023-02286-B. Published March 1, 2023. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://www.dni.gov https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/Updated_Assessment_of_Anomalous_Health_Incidents.pdf

- 3.Verma R, Swanson RL, Parker D, et al. Neuroimaging findings in US Government personnel with possible exposure to directional phenomena in Havana, Cuba. JAMA. 2019;322(4):336-347. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan L, Hallett M, Zalewski CK, et al. ; NIH AHI Intramural Research Program Team . Clinical, biomarker, and research tests among US government personnel and their family members involved in anomalous health incidents. JAMA. Published March 18, 2024. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.2413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of the Director of National Intelligence of the National Intelligence Council . Complementary efforts on anomalous health incidents; executive summary of the experts panel. February 1, 2022. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://www.dni.gov

- 6.Staab JP, Eckhardt-Henn A, Horii A, et al. Diagnostic criteria for persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): consensus document of the Committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society. J Vestib Res. 2017;27(4):191-208. doi: 10.3233/VES-170622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis, I: segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):179-194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy S, Butman JA, Pham DL; Alzheimers Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Robust skull stripping using multiple MR image contrasts insensitive to pathology. Neuroimage. 2017;146:132-147. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basser PJ, Mattiello J, LeBihan D. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys J. 1994;66(1):259-267. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basser PJ, Pierpaoli C. Microstructural and physiological features of tissues elucidated by quantitative-diffusion-tensor MRI. J Magn Reson B. 1996;111(3):209-219. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Özarslan E, Koay CG, Shepherd TM, et al. Mean apparent propagator (MAP) MRI: a novel diffusion imaging method for mapping tissue microstructure. Neuroimage. 2013;78:16-32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierpaoli C, Basser PJ. Toward a quantitative assessment of diffusion anisotropy. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36(6):893-906. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierpaoli C, Jezzard P, Basser PJ, Barnett A, Di Chiro G. Diffusion tensor MR imaging of the human brain. Radiology. 1996;201(3):637-648. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(4):537-541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowe MJ, Mock BJ, Sorenson JA. Functional connectivity in single and multislice echoplanar imaging using resting-state fluctuations. Neuroimage. 1998;7(2):119-132. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57(1):289-300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x11682119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen G, Xiao Y, Taylor PA, et al. Handling multiplicity in neuroimaging through bayesian lenses with multilevel modeling. Neuroinformatics. 2019;17(4):515-545. doi: 10.1007/s12021-018-9409-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hafiz R, Irfanoglu MO, Nayak A, Pierpaoli C. “Pscore”: a novel percentile-based metric to accurately assess individual deviations in non-Gaussian distributions of quantitative MRI metrics. J Magn Reason Imaging. Published online January 30, 2024. doi: 10.1002/jmri.29248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shirer WR, Ryali S, Rykhlevskaia E, Menon V, Greicius MD. Decoding subject-driven cognitive states with whole-brain connectivity patterns. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(1):158-65. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23(suppl 1):S208-S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.R: A language and environment for statistical computing [software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Published 2022. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://www.R-project.org/

- 22.Oishi K, Faria A, Jiang H, et al. Atlas-based whole brain white matter analysis using large deformation diffeomorphic metric mapping: application to normal elderly and Alzheimer's disease participants. Neuroimage. 2009;46(2):486-499. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lao Z, Shen D, Xue Z, Karacali B, Resnick SM, Davatzikos C. Morphological classification of brains via high-dimensional shape transformations and machine learning methods. Neuroimage. 2004;21(1):46-57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davatzikos C, Genc A, Xu D, Resnick SM. Voxel-based morphometry using the RAVENS maps: methods and validation using simulated longitudinal atrophy. Neuroimage. 2001;14(6):1361-1369. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldszal AF, Davatzikos C, Pham DL, Yan MX, Bryan RN, Resnick SM. An image-processing system for qualitative and quantitative volumetric analysis of brain images. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22(5):827-837. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199809000-00030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doshi J, Erus G, Ou Y, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Neuroimaging Initiative . MUSE: MUlti-atlas region Segmentation utilizing Ensembles of registration algorithms and parameters, and locally optimal atlas selection. Neuroimage. 2016;127:186-195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.11.073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierpaoli C, Barnett A, Pajevic S, et al. Water diffusion changes in Wallerian degeneration and their dependence on white matter architecture. Neuroimage. 2001;13(6, pt 1):1174-1185. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uddin LQ, Nomi JS, Hébert-Seropian B, Ghaziri J, Boucher O. Structure and function of the human insula. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;34(4):300-306. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menon V, Uddin LQ. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214(5-6):655-667. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters SK, Dunlop K, Downar J. Cortico-striatal-thalamic loop circuits of the salience network: a central pathway in psychiatric disease and treatment. Front Syst Neurosci. 2016;10:104-104. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2016.00104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sojka P, Slovák M, Věchetová G, Jech R, Perez DL, Serranová T. Bridging structural and functional biomarkers in functional movement disorder using network mapping. Brain Behav. 2022;12(5):e2576. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdallah CG, Averill CL, Ramage AE, et al. Salience network disruption in U.S. Army soldiers with posttraumatic stress disorder. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks). Published online May 15, 2019. doi: 10.1177/2470547019850467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akiki TJ, Averill CL, Abdallah CG. A network-based neurobiological model of PTSD: evidence from structural and functional neuroimaging studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(11):81. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0840-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilland E, Landrø NI, Harmer CJ, Maglanoc LA, Jonassen R. Within-network connectivity in the salience network after attention bias modification training in residual depression: report from a preregistered clinical trial. Front Human Neurosci. 2018;12:508. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierpaoli C. Artifacts in Diffusion MRI. Diffusion MRI: Theory, Methods, and Applications. Oxford University Press; 2011:303-318. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark KA, O’Donnell CM, Elliott MA, et al. Inter-scanner brain MRI volumetric biases persist even in a harmonized multi-subject study of multiple sclerosis. bioRxiv. Published online May 5, 2022. doi: 10.1101/2022.05.05.490645 [DOI]

- 37.Masdeu JC. Neuroimaging in psychiatric disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8(1):93-102. doi: 10.1007/s13311-010-0006-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker L, Chang LC, Nayak A, et al. The diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) component of the NIH MRI study of normal brain development (PedsDTI). Neuroimage. 2016;124(pt B):1125-1130. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.05.083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao N, Yuan LX, Jia XZ, et al. Intra- and inter-scanner reliability of voxel-wise whole-brain analytic metrics for resting state fMRI. Front Neuroinform. 2018;12:54. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2018.00054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson DR, Burnham KP, Gould WR, Cherry S. Concerns about finding effects that are actually spurious. Wildlife Society Bulletin (1973-2006). 2001;29(1):311-316. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3784014 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gelman A. Statistics and the crisis of scientific replication. Published 2014. Accessed February 29, 2024. http://stat.columbia.edu/~gelman/research/published/psych_crisis_minipaper.pdf

- 42.van Zwet EW, Cator EA. The significance filter, the winner’s curse and the need to shrink. Stat Neerl. 2021;75(4):437-452. doi: 10.1111/stan.12241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Structural Volumetric and Clinical MRI

eAppendix 2. Structural Diffusion MRI

eAppendix 3. Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP)

eAppendix 4. Resting State Functional MRI (RS-fMRI)

eAppendix 5. Statistical Analysis for RS-fMRI

eAppendix 6. Assessing Relationship of Imaging Metrics With Clinical Measures

eAppendix 7. Outcome Metrics

Data Sharing Statement