Abstract

Cellulosomes are intricate cellulose‐degrading multi‐enzymatic complexes produced by anaerobic bacteria, which are valuable for bioenergy development and biotechnology. Cellulosome assembly relies on the selective interaction between cohesin modules in structural scaffolding proteins (scaffoldins) and dockerin modules in enzymes. Although the number of tandem cohesins in the scaffoldins is believed to determine the complexity of the cellulosomes, tandem dockerins also exist, albeit very rare, in some cellulosomal components whose assembly and functional roles are currently unclear. In this study, we characterized the structure and mode of assembly of a tandem bimodular double‐dockerin, which is connected to a putative S8 protease in the cellulosome‐producing bacterium, Clostridium thermocellum. Crystal and NMR structures of the double‐dockerin revealed two typical type I dockerin folds with significant interactions between them. Interaction analysis by isothermal titration calorimetry and NMR titration experiments revealed that the double‐dockerin displays a preference for binding to the cell‐wall anchoring scaffoldin ScaD through the first dockerin with a canonical dual‐binding mode, while the second dockerin module was unable to bind to any of the tested cohesins. Surprisingly, the double‐dockerin showed a much higher affinity to a cohesin from the CipC scaffoldin of Clostridium cellulolyticum than to the resident cohesins from C. thermocellum. These results contribute valuable insights into the structure and assembly of the double‐dockerin module, and provide the basis for further functional studies on multiple‐dockerin modules and cellulosomal proteases, thus highlighting the complexity and diversity of cellulosomal components.

Keywords: binding affinity, NMR, protein complex, protein–protein interaction, scaffolding protein, tandem modules, X‐ray crystallography

1. INTRODUCTION

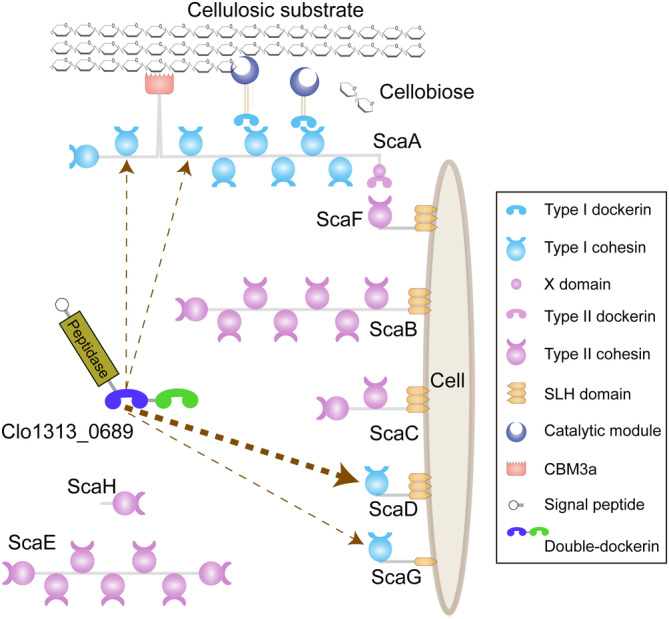

Lignocellulose is composed of various types of recalcitrant polysaccharides, notably cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, that form a rigid, recalcitrant substrate. Nevertheless, lignocellulose is the most widely distributed renewable carbon source in the world. Microbial conversion of lignocellulosic biomass to simple sugars is a key step in the development of renewable energy and carbon recycling (Liu et al., 2020). One of the most efficient systems in the bioconversion paradigm is the cellulosome complex, which comprises an elaborate and sophisticated multi‐enzymatic nanomachine, produced mainly by anaerobic cellulolytic bacteria (Artzi et al., 2017; Bayer et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2017). The assembly of the cellulosome, as exemplified in Clostridium thermocellum, normally includes the integration of dockerin (Doc)‐bearing enzymes into a non‐catalytic primary scaffolding protein (scaffoldin) that contains tandem cohesin (Coh) modules, which is further integrated into a secondary, cell‐wall anchoring scaffoldin (Fontes & Gilbert, 2010; Hong et al., 2014; Rincon et al., 2010; Smith & Bayer, 2013) (Figure 1). The architectural diversity of cellulosomes therefore relies on the variety and abundance of the scaffoldins and cellulosomal enzymes, thus resulting in distinct molecular arrangements among different bacterial species in terms of complexity and diversity (Alves et al., 2021; Bayer et al., 2008; Gilbert, 2007; Himmel et al., 2010; Rincon et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2017). Some mesophilic bacteria, including Clostridium cellulovorans, Clostridium cellulolyticum, and Clostridium josui, contain only one primary scaffoldin protein, forming simple cellulosomes (Bayer et al., 2008; Fontes & Gilbert, 2010; Smith et al., 2017). In contrast, the cellulosomes of mesophilic Ruminococcus flavefaciens and Acetivibrio cellulolyticus exhibit a higher degree of complexity, even than that of C. thermocellum, due to the presence of adaptor scaffoldins and additional cellulosomal components (Bensoussan et al., 2017; Bule et al., 2016; Hamberg et al., 2014; Israeli‐Ruimy et al., 2017). In addition to the cellulolytic enzymes and scaffoldins, cellulosomes also contain a range of dockerin‐bearing components that are not directly involved in substrate degradation, such as the expansin‐like domain (Chen et al., 2016; Cosgrove, 2017), the subtilisin‐like serine protease and papain‐like cysteine protease (Cuív et al., 2013; Levy‐Assaraf et al., 2013), the serpin superfamily of serine protease inhibitor (Cuív et al., 2013; Meguro et al., 2011), and the CotH‐like domain (Artzi et al., 2014), resulting in even more complexity of cellulosomal function and regulation.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the cellulosome from C. thermocellum DSM1313. The proposed binding position of Clo1313_0689 on scaffoldins are indicated by dashed arrows and the thickness of arrow lines indicate the experimentally determined differences in binding affinities.

Coh‐Doc complexes involved in the integration of cellulosomal enzymes are classified as type I (Pinheiro et al., 2009), while type II Coh‐Doc interactions are engaged in the attachment of cellulosomes onto the cell surface (Artzi et al., 2017; Bayer et al., 2008; Currie et al., 2012), with the exception of B. cellulosolvens, wherein the roles of the two Coh‐Doc types are reversed (Bayer et al., 2008; Noach et al., 2005). The structure of the type I cohesin is composed of a nine‐stranded flattened β‐barrel with jelly‐roll topology. Type I dockerins contain a pair of 22‐residue segment that is organized into an F‐hand calcium‐binding motif and an α‐helix (Pages et al., 1997). Each segment displays an identical overall structure as reflected by the internal twofold symmetry in the dockerin (Carvalho et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2014), and generally presents two similar Coh‐binding interfaces supporting a dual‐binding mode (Carvalho et al., 2007; Flint et al., 2008). Although the type II C. thermocellum dockerin (Adams et al., 2006) interacts with its cohesin in a single‐mode binding mechanism, some type II cohesin‐dockerin pairs exhibit a dual‐binding mode (Duarte et al., 2021). In general, cellulosomal scaffoldins consist of several tandem cohesin modules which bind to a multiplicity of enzymes, most of which contain only a single dockerin. Therefore, the structural complexity of the cellulosome is mainly determined by the number and type(s) of cohesins in the scaffolding proteins (Carvalho et al., 2007).

Interestingly, though very rare, double‐ and multiple‐dockerin modules have also been found in some cellulosome‐producing bacteria. Most double‐dockerin‐bearing proteins either contain a protease module or contain only the double‐dockerin alone, without attachment to another type of module (Chen et al., 2019). In C. thermocellum DSM1313, the double‐dockerins are present in Clo1313_0689, which includes an additional S8 family serine protease domain (Figure 1), and Clo1313_2944, which contains only the double‐dockerin pair (Chen et al., 2019; Schwarz & Zverlov, 2006). These two proteins are conserved in all sequenced C. thermocellum strains and have been previously identified in transcriptomic and proteomic studies (Raman et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2013). In addition, multiple‐dockerin modules have been found in some strains of Ruminococcus flavefaciens, which contain cellulosomal proteins with triple and septuple dockerin‐containing modules (Dassa et al., 2014), as well as Oscillospiraceae bacterium J5864_00540, which contains a protein with six dockerin modules (GenBank no. MBP0960610.1). These double‐ and multiple‐dockerin proteins will potentially result in a more complex assembly of cellulosome architectures, but their structure and function have not yet been elucidated. The conformation of these multi‐dockerin regions will not only increase our knowledge of cellulosomes but also provide new components for synthetic biology and biotechnology (Bayer et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2022; Fierer et al., 2023).

In this study, we investigate the structure of the double‐dockerin of Clo1313_0689 (dDoc_0689) from C. thermocellum and its interactions with various cohesins using biophysical techniques, thus providing insight into the assembly and function of this unconventional cellulosomal component.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. DNA cloning and plasmid construction

The genes of dDoc_0689 (residues 464–605 of Clo1313_0689) and Coh_ScaA2 (residues 183–322 of Clo1313_0627) were cloned into the pET30a and pET28a vectors, respectively. The protein expression and purification procedures have been described previously (Chen et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2020). Like dDoc_0689, the DNA fragments of Doc1_0689 (residues 464–535 of Clo1313_0689) and Doc2_0689 (residues 536–605 of Clo1313_0689) were cloned into the pET30a vector between the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites for protein expression. Similar to Coh_ScaA2, the DNA fragments of Coh_ScaA3 (residues 554–698 of Clo1313_0627), Coh_ScaD (residues 31–175 of Clo1313_0630), Coh_ScaG (residues 107–263 of Clo1313_1768), and Coh_CipC (residues 283–430 of Ccel_0728) were inserted into the pET28a vector between the EcoR I and Xho I restriction sites. All recombinant plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in Table S1.

2.2. Protein expression and purification

All recombinant plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells, which were then cultured either in LB medium or M9 minimal media at 37°C. For dDoc_0689 and Doc1_0689, isopropyl‐β‐D‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added at a concentration of 0.5 mM when the optical density at 600 nm reached ~1.2, and culturing of the cells was continued for another 4–6 h at 37°C. After ultrasonication of the harvested cells, the inclusion body was dissolved in a buffer containing 6 M urea and initially purified using a Histrap column (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) under denaturing conditions (buffers containing 6 M urea), followed by dilution renaturation and gel filtration using a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). For other proteins, the timing for adding IPTG was set when the culture reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.8–1.0. These proteins were expressed in soluble form and purified using the Histrap and the Superdex 75 columns without the denaturation and renaturation steps. The purity of the target proteins was judged to be >95% by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Figure S1).

2.3. NMR structure determination

Samples for NMR structure determination consisted of ~0.6 mM dDoc_0689 in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.9) with 90% H2O/10% D2O (v/v), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 3 mM DTT, 0.02% (w/v) sodium 2,2‐dimethylsilapentane‐5‐sulfonate (DSS), and 0.2× EDTA‐free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). All NMR experiments were performed at 298 K on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a z‐gradient triple‐resonance TCI cryoprobe.

NMR structure calculation procedures were similar to those previously described (Chen et al., 2023; Wei et al., 2019). Initial dDoc_0689 structures were calculated using the CYANA (Herrmann et al., 2002) software with the NOE peak lists from the 3D 15N‐edited and 13C‐edited NOESY HSQC spectra and dihedral angle restraints derived from the chemical shifts using the program TALOS‐N (Shen & Bax, 2015). Based on the initial structures and the NOE peak lists, distance restraints were derived and refined by the programs SANE (Duggan et al., 2001), and the final structures were refined using CNS (Brunger et al., 1998) and RECOORDScripts (Nederveen et al., 2005). Hydrogen‐bond and Ca2+ restraints were introduced in the late refinement stages of the structure calculations. The final structures were analyzed using PROCHECK_NMR (Laskowski et al., 1996), and WHAT_CHECK (Hooft et al., 1996). All of the structure figures were generated using PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org/).

2.4. Crystal structure determination

Crystallization conditions were set up using the sitting‐drop vapor diffusion method with a crystallization robot NT8 (Formulatrix, USA), and were screened by using commercial screening kits at 18°C. The concentration of purified dDoc_0689 protein used for the initial screens was approximately 10 mg/mL. The final crystallization condition was 0.1 M bis‐Tris, 25% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 3350, pH 5.5. Diffraction data were collected at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), beamline BL19U, in a 100‐K nitrogen stream. Data indexing, integration, and scaling were conducted using X‐ray Detector Software (XDS) (Kabsch, 2010). Initial structures were determined by molecular replacement using the dockerin structure in PDB 1OHZ (Carvalho et al., 2003) as the search model in the PHENIX program Phaser‐MR (Adams et al., 2010). Refinements of the structures were iteratively performed using the programs COOT (Emsley et al., 2010) and PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010).

2.5. NMR titration

NMR titration experiments were performed at 298 K on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a cryoprobe. All protein samples used for the NMR titration experiments were eventually dissolved in Tris Buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 3 mM DTT). The 15N‐labeled protein samples contained 0.1 or 0.2 mM dockerin proteins, 10% D2O, and 0.02% DSS. For titration, cohesin proteins were gradually added to the 15N‐labeled proteins until the ratio of their concentrations reached 1:2.

2.6. Isothermal titration calorimetry measurements

The affinities of dockerins and cohesins were measured by using the isothermal titration calorimeter MicroCal PEAQ‐ITC (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, UK) at 25°C. Before the ITC experiments, all protein samples were dialyzed against Tris buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 3 mM DTT). The sample cell was loaded with 280 μL of dockerin samples (50 μM), and the syringe was filled with 50 μL of cohesin samples (500 μM). Titrations were carried out by adding 0.8 mL of cohesin proteins for the first injection and 2 μL for each of the subsequent 19 injections, with stirring at 750 rpm. Binding parameters were determined by fitting the experimental binding isotherms using a single‐site model.

3. RESULTS

3.1. The sequence of dDoc_0689 deviates from other known dockerins

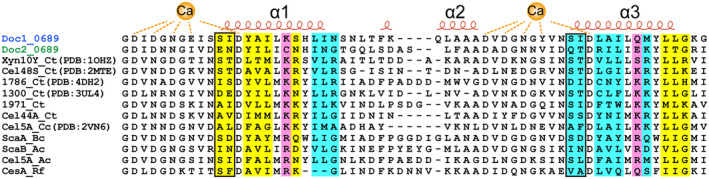

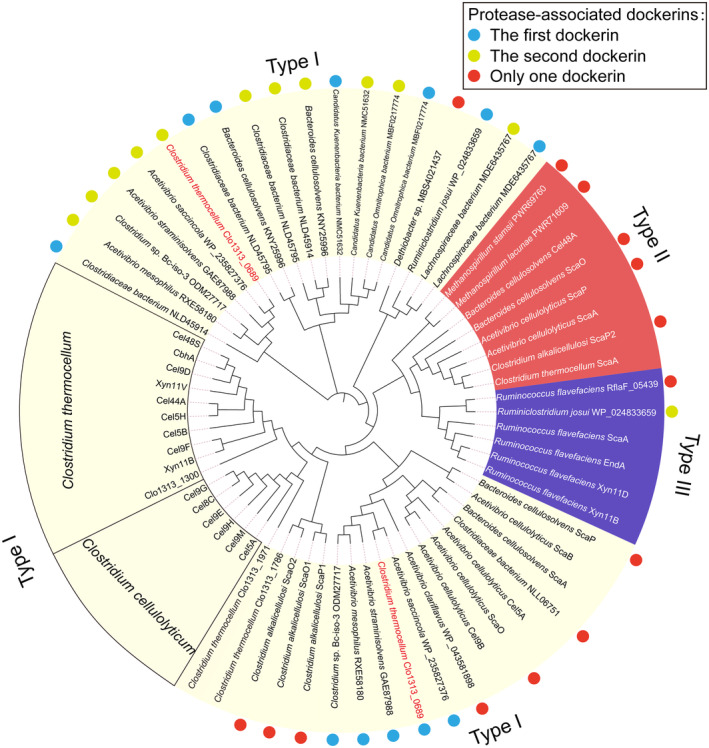

Clo1313_0689 is conserved in all sequenced C. thermocellum strains, and homologues also exist in several other cellulosome‐producing bacteria according to a Blast search in the NCBI GenBank database (Figure S2). Sequence analysis showed that each dockerin module of dDoc_0689, namely Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689, belongs to the type I dockerin module (DocI) containing two nearly repetitive α‐helices and conserved calcium binding F‐hand motif (Figure 2). However, Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689 exhibit certain variations compared to other characterized DocIs. The canonical “recognition motif,” ST in the typical C. thermocellum DocIs, such as Doc_Xyn10Y (PDB: 1OHZ) and Doc_Cel48S (PDB: 2MTE), is substituted by SI in Doc1_0689, and EN and QT in Doc2_0689, respectively (Pages et al., 1997). Additionally, other putative residues involved in Coh‐binding are also altered to varying degrees, as revealed by sequence alignment (Figure 2). Furthermore, the sequences and putative Coh‐binding residues of Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689 also differ from the special non‐canonical DocIs found in C. thermocellum ATCC27405, including Doc_258, Doc_435, Doc_Cel44A, and Doc_918 (Pinheiro et al., 2009), which correspond to Clo1313_1971, Clo1313_1786, Clo1313_1604 (Cel44A), and Clo1313_1300 in C. thermocellum DSM1313, respectively (Figure 2). These observations would indicate that the specificity of interaction of Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689 would differ from that of the canonical interaction with type I C. thermocellum cohesins and would also differ between themselves. Moreover, an evolutionary tree analysis shows that both Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689 are notably distinct from the DocIs of other well‐studied cellulosome‐producing species, such as C. cellulolyticum, A. cellulolyticus, and R. flavefaciens, as well as type II and type III dockerins (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Sequence alignments of type I dockerins. Secondary structure elements of Doc_Xyn10Y (PDB: 1OHZ) are shown at the top of the alignment. The putative residues involved in Coh‐binding are highlighted with yellow background (for the N‐terminal binding site), cyan background (for the C‐terminal binding site), or magenta background (for both the N‐terminal and C‐terminal binding sites) according to the interaction of Doc_Xyn10Y and Coh_ScaA2 (Carvalho et al., 2003). The characteristic key residues are indicated by black rectangles.

FIGURE 3.

Molecular evolutionary tree of dockerin modules. All protease‐associated dockerins from several species are labeled by colored dots. The light blue and yellow green dots represent the first and second dockerin modules of the double‐dockerin modules connected to the protease domains, respectively. The red dots denote the single dockerin module of the protease‐containing proteins. Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689 are highlighted with species names in red. The type I, II, and III dockerin modules are shaded in light yellow, red, and purple, respectively.

Besides the double‐dockerin‐containing cellulosomal proteases, there are also other cellulosomal proteases that contain only a single dockerin module (Figure S2), some of which are also connected to cohesin modules and thus serve as scaffoldin proteins as well (Dassa et al., 2012; Phitsuwan et al., 2019; Zhivin et al., 2017). Sequence and molecular evolutionary tree analyses reveal that the majority of the dockerin modules connected with proteases are classified as DocIs. However, these particular dockerin modules are primarily grouped into two large branches within the evolutionary tree of dockerins, which are closely related to Doc1_0689 or Doc2_0689, but remain distant from those of C. thermocellum and C. cellulolyticum. Additionally, a small number of protease‐associated dockerins have been categorized as type II and ruminococcal type III dockerin modules (Figure 3), thereby providing further diversity to the dockerin dataset. In summary, dDoc_0689 and most of the protease‐connected dockerins exhibit a distinct composition of two special tandem DocIs, whose key motif and other putative residues involved in cohesin binding are significantly different from those identified in previous studies. A few remaining cellulosomal proteases contain only one unconventional DocI, or type II/III dockerin modules. Their distinct composition and sequences imply that they may play specialized roles in the parent cellulosome complex.

3.2. Structure of dDoc_0689

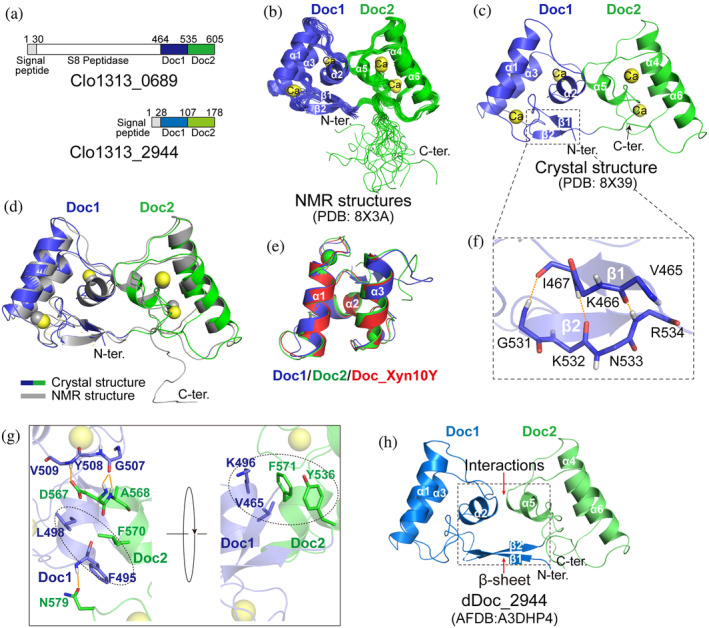

To provide a structural basis for understanding the function of dDoc_0689 in C. thermocellum, we solved both the NMR and crystal structures of dDoc_0689 (residues 464–605 of Clo1313_0689) (Figure 4a–c, Tables S2 and S3). Two dDoc_0689 structures are observed in one asymmetric unit of the crystal (Figure S3A). The overall NMR and crystal structures are similar to each other (Figure 4d), with the backbone RMSDs of 0.916 Å between them, indicating that the overall topology of dDoc_0689 is not a consequence of the crystallization process. The structure of dDoc_0689 comprises two tandem DocIs connected by a short linker segment of approximately 4 residues (residues 72–76). Each of the dockerin modules, Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689, possesses the remarkable properties of the DocIs, including the anti‐parallel α‐helices H1 and H3 (H1 of Doc1_0689: residues 478–489, H3 of Doc1_0689: residues 511–522, H1 of Doc2_0689: residues 549–560, H3 of Doc2_0689: residues 583–594), the connecting α‐helix H2 (H2 of Doc1_0689: residues 495–501, H2 of Doc2_0689: residues 567–573), and the two characteristic calcium‐binding F‐hand motifs (with a typical n, n + 2, n + 4, n + 6, n + 11, plus a water molecule, pattern of coordination) (Figure 4c). Overall, the separate structures of Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689 can be superimposed well with each other (backbone RMSD is 0.849 Å), as well as with the typical DocI DocI_Xyn10Y of C. thermocellum (PDB: 1OHZ) with RMSD values of 0.672 and 0.625 Å, respectively (Figure 4e). Two short anti‐parallel β‐strands are formed between residues 465–467 at the N‐terminus and residues 531–534 at the C‐terminus of Doc1_0689 (Figure 4f), thus forming an intricate type of intramolecular clasp, which has not been found in other dockerins to our knowledge.

FIGURE 4.

Structure of dDoc_0689. (a) Schematic representation of the composition of the double‐dockerin‐containing proteins of C. thermocellum. (b, c) Ribbon representation of the ensemble of 20 NMR structures (b) and the crystal structure (c) of dDoc_0689. Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689 are colored in blue and green, respectively. (d) Superposition of the NMR (gray) and crystal (blue for Doc1_0689 and green for Doc2_0689) structures of dDoc_0689. (e) Superposition of the crystal structures of separated Doc1_0689 (blue), Doc2_0689 (green), and DocI_Xyn10Y (red, PDB: 1OHZ‐B). (f) Representation of the intramolecular clasp formed by the anti‐parallel β‐sheet of Doc1_0689, which is enlarged from panel (c) into the dashed box. The residues involved in the formation of the intramolecular clasp are shown as sticks. (g) Interactions between Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689 in dDoc_0689. The residues involved in the interactions are shown as blue (Doc1_0689) and green (Doc2_0689) sticks. (h) AlphaFold2 structural model of dDoc_2944.

There is no significant flexibility between the two dockerin modules, as evidenced by a backbone RMSD of only 0.543 Å for the ensemble of the NMR structures (Figure 4b, Table S2). Besides the covalent linker between the two dockerins Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689, the two dockerins are packed together by hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds (Figure 4g). Specifically, one hydrophobic interaction is formed by the side chains of F495, L498 of Doc1_0689 and F570 of Doc2_0689, while another interaction involves V465, K496 of Doc1_0689 and F571, Y536 of Doc2_0689. Three hydrogen bonds are formed between NH of F495 and the side‐chain carboxyl of N579, NH of V509 and the side‐chain CO of D567, and between the CO of G507 and NH of A568. Consistently, in the crystal structure, the B‐factors of the linker and the interface residues between Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689 are relatively low (Figure S3B). However, when Doc1_0689 or Doc2_0689 is superposed between the two molecules of the asymmetric unit in the crystal structure of dDoc_0689, a slight shift (2–3 Å) can be observed in the other dockerin module (Figure S4), suggesting the existence of minor flexibility between the two dockerin modules. Despite the observed interaction between Doc1 and Doc2, it is noteworthy that the interface of this interaction does not have an impact on the exposure of the cohesin‐binding sites of each dockerin in dDoc_0689 (Figure S5).

The purification of another double‐dockerin‐containing protein Clo1313_2944 (Figure 4a) in C. thermocellum was unsuccessful. We therefore analyzed the AlphaFold2 structure model of dDoc_2944 and found that its two dockerin modules exhibit similar interactions to those observed in dDoc_0689 (Figure 4h). Furthermore, Doc1_2944 also displays similar but even longer anti‐parallel β‐sheet between the N‐ and C‐termini (Figure 4h). Therefore, the inter‐dockerin interactions and the intramolecular β‐sheet clasp could potentially represent two common characteristics of double‐dockerins.

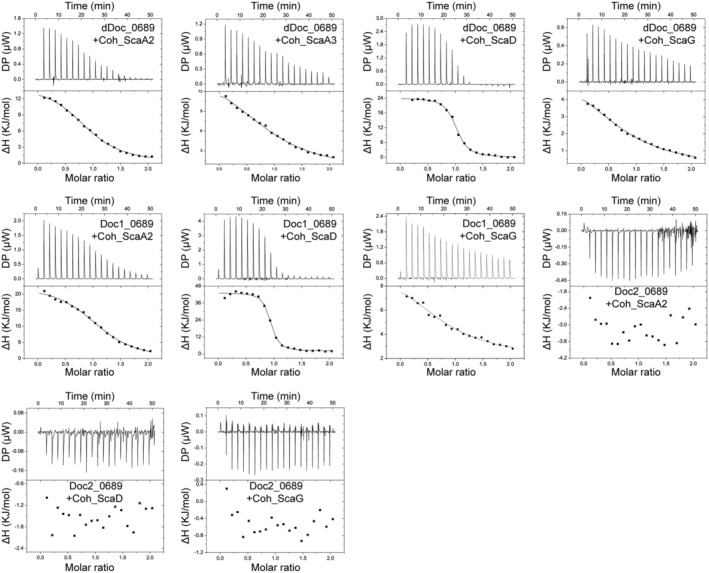

3.3. dDoc_0689 exhibits a preference for binding to Coh_ScaD in C. thermocellum

Due to the unique composition and sequence characteristics of dDoc_0689, it is speculated to play a special role in the assembly of the cellulosome. Therefore, we analyzed the interactions of dDoc_0689 with various cohesin modules using NMR titration and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) methods. There are three scaffoldin proteins that contain type I cohesins in C. thermocellum: the primary scaffoldin protein ScaA (Clo1313_0627) that contains nine highly‐homologous tandem cohesins, and two cell‐bound scaffoldins, ScaD (Clo1313_0630) and ScaG (Clo1313_1768), each of which contains only one cohesin (Yoav et al., 2017). The results of ITC and NMR titration experiments showed that dDoc_0689 interacts with all tested type I cohesin modules with varying affinities (Figure 5 and Figure S6). Among them, dDoc_0689 shows a clear preference for binding to the cohesin of ScaD (Coh_ScaD) with a K D of 0.54 μM, one to two orders of magnitude higher than that detected for other type I cohesins (Figure 5, Table 1).

FIGURE 5.

Representative ITC data for titrations of various cohesins into dockerins. ITC traces are shown on top, and integrated binding isotherms are shown on the bottom. The curve represents the best fit to a single‐site‐binding model. The dockerin and cohesin proteins used for the titrations are shown in each ITC trace. All ITC experiments were carried out at 298 K.

TABLE 1.

Thermodynamic parameters determined by ITC measurements.

| Dockerin | Cohesin | N (site) | K D (μM) | ΔH (kJ/mol) | ΔG (kJ/mol) | −TΔS (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dDoc_0689 | Coh_ScaA2 | 0.94 ± 0.015 | 7.39 ± 0.802 | 14.7 ± 0.496 | −29.3 | −44.0 |

| Coh_ScaA3 | 1.00 ± 0.057 | 21.1 ± 6.48 | 16.1 ± 2.30 | −26.7 | −42.8 | |

| Coh_ScaD | 0.977 ± 0.006 | 0.54 ± 0.066 | 24.1 ± 0.360 | −35.8 | −59.9 | |

| Coh_ScaG | 0.864 ± 0.038 | 26.4 ± 7.61 | 6.46 ± 1.03 | −26.2 | −32.6 | |

| Coh_CipC | 0.975 ± 0.006 | 0.003 ± 0.002 | −28.0 ± 0.592 | −48.9 | −20.9 | |

| Doc1_0689 | Coh_ScaA2 | 1.14 ± 0.037 | 6.70 ± 1.23 | 23.1 ± 1.34 | −29.6 | −52.7 |

| Coh_ScaD | 0.896 ± 0.007 | 0.27 ± 0.054 | 41.2 ± 0.752 | −37.6 | −78.7 | |

| Coh_ScaG | 0.883 ± 0.088 | 87.2 ± 54.0 | 7.99 ± 2.47 | −23.2 | −31.2 | |

| Coh_CipC | 0.866 ± 0.003 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | −31.1 ± 0.434 | −49.1 | −18.0 | |

| dDoc‐S478E/I479N | Coh_ScaD | 1.07 ± 0.013 | 1.37 ± 0.197 | 25.5 ± 0.619 | −33.5 | −59.0 |

| dDoc‐S511E/I512N | Coh_ScaD | 1.18 ± 0.021 | 1.47 ± 0.316 | 19.5 ± 0.768 | −33.3 | −52.8 |

3.4. The first dockerin module dominates the interaction of dDoc_0689 with the cohesins

Sequence alignment shows that both Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689 exhibit two putative cohesin‐binding segments (Figure 2), suggesting a potential dual‐binding mode of each dockerin module. Importantly, the individual cohesin‐binding surface is not impacted by the interaction between Doc1_0689 and Doc2_0689 (Figure S5). Therefore, dDoc_0689 is predicted to possess four potential cohesin‐binding sites. However, the two alternative cohesin‐binding positions on the same dockerin module would clash (Figure S7), similar to previous observations for the dual‐binding mode interactions, in which each dockerin module can only bind one cohesin in one orientation (Carvalho et al., 2007; Pinheiro et al., 2008). To investigate these potential binding events, we constructed isolated dockerins and detected their interaction with various cohesins. The results showed that Doc2_0689 (residues 536–605 of Clo1313_0689) failed to bind any of the tested cohesins. The NMR 1H–15N HSQC spectrum showed well‐dispersed peaks indicated that the Doc2_0689 construct is indeed properly folded, and the presence of characteristic peaks located in the downfield region of the spectrum confirmed that the construct also successfully binds the calcium ion (Figure S6), ruling out the possibility that the lack of binding to cohesins observed for Doc2_0689 was attributed to misfolding of the construct. Doc1_0689 (residues 464–535 of Clo1313_0689) displayed Coh binding properties and affinities similar to the entire dDoc_0689 (Figure 5, Figure S6, Table 1), indicating that Doc1_0689 is the primary factor for the binding of dDoc_0689 to the cohesins tested. These results indicate that the putative cohesin‐binding motifs of Doc2_0689 (EN for the first site, and QT for the second site) cannot bind to any of the tested cohesins, while the SI motifs of Doc1_0689 can still work with the tested type I cohesins although they differ from the canonical ST motif of DocIs in C. thermocellum.

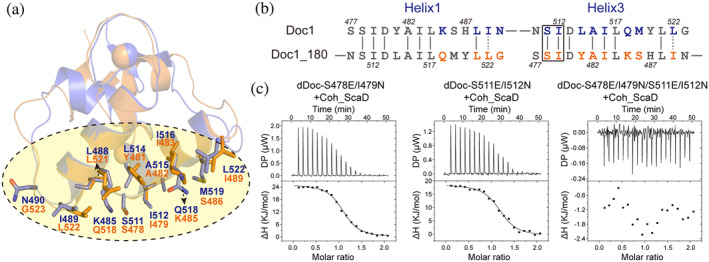

3.5. Doc1_0689 exhibits the dual‐binding mode

The majority of DocIs, such as Doc_Xyn10Y and Doc_Cel5A (Carvalho et al., 2007; Pinheiro et al., 2008), display internal symmetry, resulting in the presence of the dual‐binding mode for cohesin binding (Nash et al., 2016). Some unusual dockerins, such as Doc_1300 and Doc_1786 from C. thermocellum, lack structural symmetry and exhibit a special single‐binding mode (Brás et al., 2012). The two putative Coh‐binding surfaces of Doc1_0689 share the same key binding residues SI, and some of the other residues in the two Coh‐binding surfaces also exhibit symmetry (Figure 6a,b), suggesting that Doc1_0689 may possess a dual‐binding mode. To verify this, we mutated each of the two key binding sites of Doc1_0689 in dDoc_0689 to EN, which corresponds to the first binding motif of Doc2_0689. Both mutants were unchanged in their binding capacity with Coh_ScaD, compared to that of the wild‐type dDoc_0689 in ITC experiments (Figure 6c, Table 1). However, when both SI motifs were mutated to EN, the mutant no longer bound Coh_ScaD (Figure 6c). These results indicated that destroying only one cohesin‐binding site does not affect the binding between Doc1_0689 and Coh_ScaD, while destroying both key sites eliminates the ability of Doc1_0689 to bind to cohesin. Therefore, the interaction between Doc1_0689 and cohesins exhibits the canonical dual‐binding mode.

FIGURE 6.

Identification of the “dual binding mode” of Doc1_0689. (a) Structural superposition of Doc1_0689 (blue) and a 180°‐rotated Doc1_0689 (orange). The putative residues involved in C‐ and N‐terminal cohesin binding sites are shown as blue and orange sticks, respectively. (b) Sequence alignment of α‐helix 1 and 3 of Doc1_0689 and its rotated state. The key sites for species specificity are indicated by a black rectangle. (c) ITC titration of the mutants of dDoc_0689 with Coh_ScaD.

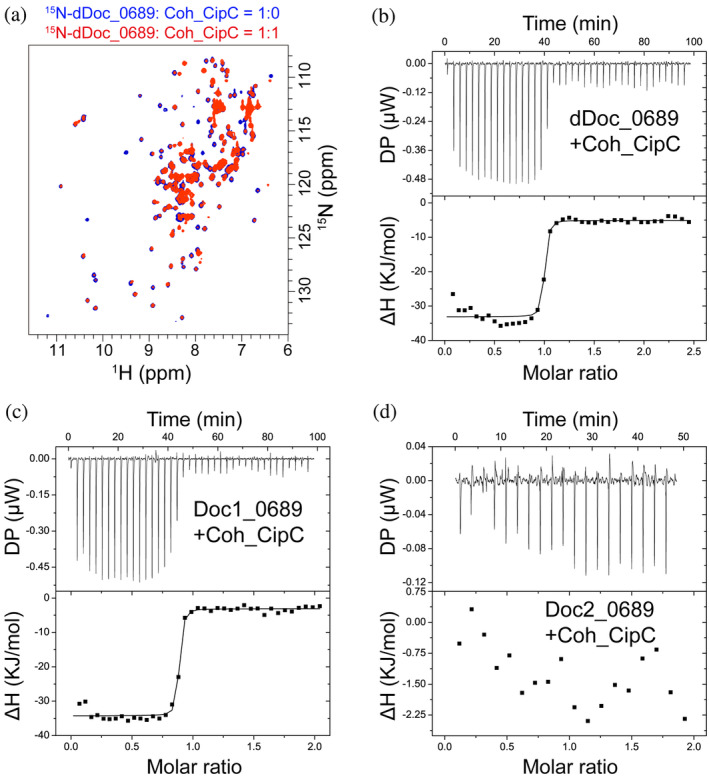

3.6. Doc1_0689 exhibits high affinity for the cohesin from C. cellulolyticum

The putative cohesin‐binding residues of Doc1_0689 display higher hydrophobicity compared to other C. thermocellum DocIs. In particular, the key binding motif “ST” is substituted with “SI” in Doc1_0689, and the main polar residues “KR” are replaced by “QM” or “KS” in Doc1_0689 (Figure 2). Moreover, our results showed that dDoc_0689 and Doc1_0689 exhibit stronger affinity toward Coh_ScaD, which has been demonstrated to engage in more hydrophobic interactions with dockerins compared to Coh_ScaA2 (Brás et al., 2012). Thus, these features provide valuable insight into the possible significance of hydrophobic interactions in the specific recognition between Doc1_0689 and its cohesin partner. In addition, it is well‐known that in C. cellulolyticum, hydrophobic interactions dominate the interaction between the cohesin modules of CipC, the primary scaffoldin in this bacterium that contains eight similar type I cohesins, and the dockerins which commonly have the key hydrophobic binding motifs “AI” or “AL” (Mechaly et al., 2001; Pinheiro et al., 2008). Indeed, previous studies showed that a single mutation from threonine to leucine in the key binding motif “ST” of dockerins from C. thermocellum allows its dockerin mutant to bind to the cohesins from C. cellulolyticum with high affinity (Mechaly et al., 2001). We therefore suspected that dDoc_0689 would also bind to the CipC cohesins from C. cellulolyticum. We thus investigated the interaction between dDoc_0689 and the first cohesin of the scaffoldin CipC (Coh_CipC) from C. cellulolyticum using ITC and NMR titration experiments. Surprisingly, we found that dDoc_0689 not only recognizes Coh_CipC but also exhibits a much stronger binding affinity with Coh_CipC than all other tested cohesins (Figure 7, Table 1). The K D for this interaction is around 3 nM, as derived from ITC measurements (Table 1), indicating an affinity similar to those of the canonical intraspecies cohesin‐dockerin interactions (with K D values ranging from sub‐nM to several nM as determined by ITC) in either C. cellulolyticum or C. thermocellum (Pinheiro et al., 2008, 2009; Schaeffer et al., 2002).

FIGURE 7.

The interaction of dDoc_0689 and the cohesin of C. cellulolyticum Coh_CipC. (a) NMR titration of dDoc_0689 with Coh_CipC. Overlaid 1H–15N HSQC spectra of 15N‐labeled dDoc_0689 without and with unlabeled Coh_CipC are shown in blue and red, respectively. (b–d) ITC titrations of dDoc_0689 and its two individual dockerins with Coh_CipC. ITC traces are shown at the top, and integrated binding isotherms are shown at the bottom. The curve represents the best fit to a single‐site‐binding model. All NMR titration and ITC experiments were carried out at 298 K.

4. DISCUSSION

The intricate assembly and diverse composition of cellulosomes confer the remarkable capacity to efficiently degrade lignocellulosic substrates (Artzi et al., 2017; Bule et al., 2018; Li et al., 2023; Moraïs et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2017; Smith & Bayer, 2013). Advancements in omics‐based data mining have unveiled numerous novel cellulosomal components that likely play significant roles in assembly, regulation, and substrate degradation (Artzi et al., 2014, 2017; Ben David et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016; Cosgrove, 2017; Izquierdo et al., 2012; Zverlov et al., 2005).

In this study, we focused on the unusual double‐dockerin module dDoc_0689 of a cellulosomal S8 protease component from C. thermocellum. We showed that its two DocIs, connected by a linker, possess an extensive interface comprising hydrophobic interactions and H‐bonds, with limited mobility between them. The structures of dDoc_0689 revealed that both dockerins have canonical calcium ion binding sites and well‐folded overall structures that resemble those of other DocIs. Two short anti‐parallel β‐strands are formed between the N‐ and C‐termini residues of Doc1_0689, representing a novel type of intramolecular clasp. Intramolecular clasps, typically created by a pair of residues at the two termini of dockerin, are a defined characteristic of dockerin structures with a stabilizing effect on the functional integrity of the dockerin module (Slutzki et al., 2013). However, of the numerous C. thermocellum type I cohesins, dDoc_0689 exhibits a preference for binding to the cohesin of the cell‐bound scaffoldin ScaD, although it retains a relatively weak ability to interact with all type I cohesins (Figure 1). Additionally, our findings revealed that the first dDoc_0689 dockerin module dominates the interaction through a dual‐binding mode, while the function of the second dockerin module Doc2_0689 remains unclear as it fails to bind to any of the tested cohesins. Nonetheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that Doc2_0689 binds to another, currently unidentified cohesin, which would enable dDoc_0689 to bridge together its protease S8 and the latter protein at the cell surface via its interaction with ScaD.

dDoc_0689 shows weak interactions with the cohesins of the primary enzyme‐integrating scaffoldin ScaA, suggesting that the protein Clo1313_0689 may not function as a primary component of the complex cellulosomes. Instead, dDoc_0689 is more inclined to bind to the cell wall‐binding scaffoldin ScaD, indicating that direct attachment to the cell surface may be more advantageous for the functional properties of its associated protease component. This is somewhat similar to previous observations that the cysteine peptidase associated with a C‐terminal X‐dockerin modular dyad from R. flavefaciens was found to functionally bind to the surface‐anchoring ScaE cohesin of this rumen bacterium (Levy‐Assaraf et al., 2013). Similarly, the ScaOs and ScaPs from A. cellulolyticus, B. cellulosolvens, and C. alkalicellulosi, contain at least one predicted peptidase, a dockerin, and one or more cohesins. The latter scaffoldins were also suggested to mainly assemble onto cell‐bound scaffoldins, through sequential and experimental analysis (Hamberg et al., 2014; Phitsuwan et al., 2019; Zhivin et al., 2017).

Our analysis shows that many double dockerin‐containing proteins have a protease domain in various species (Figure 3). In addition to the unique assembling module of Clo1313_0689, the precise physiological function of its protease domain also remains unclear. Our attempts to purify the S8 protease domain of Clo1313_0689 were unsuccessful, owing, perhaps, to its toxicity to E. coli. This prevented us from experimentally analyzing the function of the protease. However, considering the binding characteristics of the tandem dockerins to various scaffoldins, it can be proposed that the cellulosomal peptidases may not be directly involved in biomass degradation per se. Instead, it may serve in cellulosomal posttranslational processing or cellular nitrogen recycling from secreted proteins. Moreover, the affinity between dDoc_0689 to ScaD is quite weak in comparison with the canonical intraspecies cohesin‐dockerin interactions, which might promote targeting of the S8 protease to its preferred proteinaceous substrate and allow it to be readily released from ScaD and the cell‐wall. In any event, the precise function of the proteases and the relationship between their precise function and specific location within the cellulosome require further experimental verification.

One interesting observation in this study is that dDoc_0689 showed a much stronger affinity to the heterologous C. cellulolyticum cohesin than to the endogenous cohesins of C. thermocellum. For the majority of type I cellulosomal dockerins, it has been well established that the dockerin from different species generally have specific interactions with their cognate cohesins (Artzi et al., 2017; Gilbert, 2007), although some exceptions have been reported. Two Xyn‐borne dockerins and Doc_44A of C. thermocellum were shown to recognize the cross‐specific cohesins from C. josui and C. cellulolyticum (Barak et al., 2005; Haimovitz et al., 2008; Jindou et al., 2004; Pinheiro et al., 2009; Sakka et al., 2009, 2011), although the observed binding was clearly weaker than the intraspecies interaction. The biological significance of this lack of species specificity is not clear. One possibility is that the cellulosomes of a particular species may employ this mechanism to recruit enzymes with advantageous or specialized functions from other organisms. This strategy would enable such a species to harness the unique capabilities of enzymes provided by different organisms without investing energy and resources into synthesizing them internally, assuming of course that the two species occupy the same ecosystem (Haimovitz et al., 2008). Therefore, the cellulosomal protease may also be beneficial for the regulation of the assembly of cellulosomes in other species by utilizing this strategy. Another physiologically relevant inter‐species cohesin‐dockerin interaction would be the potential assembly of “symbiotic cellulosomes” within a microbial community. Sequence analysis has shown that the dockerins and cohesins of various mesophilic cellulosome‐producing species share high sequence similarity, and the canonical motif Ala/Leu (Ile) of dockerins is also conserved. This phenomenon would suggest that there are more cross‐species recognition events among these cellulosomal clostridial mesophiles, thereby introducing the concept of the pan‐cellulosome (Dassa et al., 2017). Likewise, in the rumen microbiota, Ruminococcus albus—a prominent cellulose‐degrading bacterium—contains many dockerin‐bearing CAZymes but lacks scaffold proteins for enzyme aggregation within its own genome. Nevertheless, it has been argued that the rich rumen ecosystem could provide appropriate scaffoldins in an interspecies manner (e.g., those of R. flavefaciens) that may accept appropriate dockerin‐borne enzymes in a symbiotic manner (Dassa et al., 2014). Our study of Clo1313_0689 and its double dockerin provides yet another possible example of “symbiotic cellulosomes.”

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Chao Chen: Investigation; writing – original draft; visualization; methodology; funding acquisition. Hongwu Yang: Investigation. Sheng Dong: Investigation. Cai You: Investigation; funding acquisition. Sarah Moraïs: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Edward A. Bayer: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Ya‐Jun Liu: Writing – review and editing; funding acquisition. Jinsong Xuan: Writing – review and editing; funding acquisition. Qiu Cui: Writing – review and editing; funding acquisition. Itzhak Mizrahi: Funding acquisition; writing – review and editing. Yingang Feng: Conceptualization; investigation; visualization; funding acquisition; writing – review and editing; supervision.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting Information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFC3402300 to Y.F.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32070125 to Y.F., 32200030 to C.Y., 32170051 to Q.C., 32171203 to S.D., 32070028 to Y.‐J.L.), QIBEBT International Cooperation Project (Grant No. QIBEBT ICP202304 to Y.F.), the State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology Open Projects Fund (Grant No. M2022‐01 to Y.F.), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. ZR2016CB09 to C.C.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. FRF‐DF‐20‐09), Training Program for Young Teaching Backbone Talents, USTB (Grant No. 2302020JXGGRC‐005), and Major Education and Teaching Reform Research Project, USTB (Grant No. JG2021ZD01).

Chen C, Yang H, Dong S, You C, Moraïs S, Bayer EA, et al. A cellulosomal double‐dockerin module from Clostridium thermocellum shows distinct structural and cohesin‐binding features. Protein Science. 2024;33(4):e4937. 10.1002/pro.4937

Chao Chen and Hongwu Yang contributed equally to this work.

Review Editor: Aitziber L. Cortajarena

REFERENCES

- Adams JJ, Pal G, Jia Z, Smith SP. Mechanism of bacterial cell‐surface attachment revealed by the structure of cellulosomal type II cohesin‐dockerin complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:305–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python‐based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves VD, Fontes C, Bule P. Cellulosomes: highly efficient cellulolytic complexes. Subcell Biochem. 2021;96:323–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artzi L, Bayer EA, Moraïs S. Cellulosomes: bacterial nanomachines for dismantling plant polysaccharides. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artzi L, Dassa B, Borovok I, Shamshoum M, Lamed R, Bayer EA. Cellulosomics of the cellulolytic thermophile Clostridium clariflavum . Biotechnol Biofuels. 2014;7:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak Y, Handelsman T, Nakar D, Mechaly A, Lamed R, Shoham Y, et al. Matching fusion protein systems for affinity analysis of two interacting families of proteins: the cohesin‐dockerin interaction. J Mol Recognit. 2005;18:491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer EA, Lamed R, White BA, Flint HJ. From cellulosomes to cellulosomics. Chem Rec. 2008;8:364–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben David Y, Dassa B, Borovok I, Lamed R, Koropatkin NM, Martens EC, et al. Ruminococcal cellulosome systems from rumen to human. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:3407–3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensoussan L, Moraïs S, Dassa B, Friedman N, Henrissat B, Lombard V, et al. Broad phylogeny and functionality of cellulosomal components in the bovine rumen microbiome. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19:185–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brás JL, Alves VD, Carvalho AL, Najmudin S, Prates JA, Ferreira LM, et al. Novel Clostridium thermocellum type I cohesin‐dockerin complexes reveal a single binding mode. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:44394–44405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse‐Kunstleve RW, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bule P, Alves VD, Leitão A, Ferreira LM, Bayer EA, Smith SP, et al. Single binding mode integration of hemicellulose‐degrading enzymes via adaptor scaffoldins in Ruminococcus flavefaciens cellulosome. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:26658–26669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bule P, Pires VM, Fontes CM, Alves VD. Cellulosome assembly: paradigms are meant to be broken! Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2018;49:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AL, Dias FM, Nagy T, Prates JA, Proctor MR, Smith N, et al. Evidence for a dual binding mode of dockerin modules to cohesins. P Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3089–3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AL, Dias FM, Prates JA, Nagy T, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ, et al. Cellulosome assembly revealed by the crystal structure of the cohesin‐dockerin complex. P Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13809–13814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Cui Z, Song X, Liu YJ, Cui Q, Feng Y. Integration of bacterial expansin‐like proteins into cellulosome promotes the cellulose degradation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:2203–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Cui Z, Xiao Y, Cui Q, Smith SP, Lamed R, et al. Revisiting the NMR solution structure of the Cel48S type‐I dockerin module from Clostridium thermocellum reveals a cohesin‐primed conformation. J Struct Biol. 2014;188:188–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Dong S, Yu Z, Qiao Y, Li J, Ding X, et al. Essential autoproteolysis of bacterial anti‐σ factor RsgI for transmembrane signal transduction. Sci Adv. 2023;9:eadg4846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Yang H, Xuan J, Cui Q, Feng Y. Resonance assignments of a cellulosomal double‐dockerin from Clostridium thermocellum . Biomol NMR Assign. 2019;13:97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Microbial expansins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2017;71:479–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuív PO, Gupta R, Goswami HP, Morrison M. Extending the cellulosome paradigm: the modular Clostridium thermocellum cellulosomal serpin PinA is a broad‐spectrum inhibitor of subtilisin‐like proteases. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:6173–6175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie MA, Adams JJ, Faucher F, Bayer EA, Jia Z, Smith SP. Scaffoldin conformation and dynamics revealed by a ternary complex from the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:26953–26961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassa B, Borovok I, Lamed R, Henrissat B, Coutinho P, Hemme CL, et al. Genome‐wide analysis of Acetivibrio cellulolyticus provides a blueprint of an elaborate cellulosome system. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassa B, Borovok I, Lombard V, Henrissat B, Lamed R, Bayer EA, et al. Pan‐cellulosomics of mesophilic clostridia: variations on a theme. Microorganisms. 2017;5:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassa B, Borovok I, Ruimy‐Israeli V, Lamed R, Flint HJ, Duncan SH, et al. Rumen cellulosomics: divergent fiber‐degrading strategies revealed by comparative genome‐wide analysis of six ruminococcal strains. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte M, Viegas A, Alves VD, Prates JAM, Ferreira LMA, Najmudin S, et al. A dual cohesin‐dockerin complex binding mode in Bacteroides cellulosolvens contributes to the size and complexity of its cellulosome. J Biol Chem. 2021;296:100552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan BM, Legge GB, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. SANE (structure assisted NOE evaluation): an automated model‐based approach for NOE assignment. J Biomol NMR. 2001;19:321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Liu Y‐J, Cui Q. Research progress in cellulosomes and their applications in synthetic biology. Synth Biol J. 2022;3:138–154. [Google Scholar]

- Fierer JO, Tovar‐Herrera OE, Weinstein JY, Kahn A, Moraïs S, Mizrahi I, et al. Affinity‐induced covalent protein‐protein ligation via the SpyCatcher‐SpyTag interaction. Green Carbon. 2023;1:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Flint HJ, Bayer EA, Rincon MT, Lamed R, White BA. Polysaccharide utilization by gut bacteria: potential for new insights from genomic analysis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes CM, Gilbert HJ. Cellulosomes: highly efficient nanomachines designed to deconstruct plant cell wall complex carbohydrates. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:655–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert HJ. Cellulosomes: microbial nanomachines that display plasticity in quaternary structure. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:1568–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haimovitz R, Barak Y, Morag E, Voronov‐Goldman M, Shoham Y, Lamed R, et al. Cohesin‐dockerin microarray: diverse specificities between two complementary families of interacting protein modules. Proteomics. 2008;8:968–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberg Y, Ruimy‐Israeli V, Dassa B, Barak Y, Lamed R, Cameron K, et al. Elaborate cellulosome architecture of Acetivibrio cellulolyticus revealed by selective screening of cohesin‐dockerin interactions. Peer J. 2014;2:e636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann T, Guntert P, Wuthrich K. Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE assignment using the new software CANDID and the torsion angle dynamics algorithm DYANA. J Mol Biol. 2002;319:209–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmel ME, Xu Q, Luo Y, Ding S‐Y, Lamed R, Bayer EA. Microbial enzyme systems for biomass conversion: emerging paradigms. Biofuels. 2010;1:323–341. [Google Scholar]

- Hong W, Zhang J, Feng Y, Mohr G, Lambowitz AM, Cui GZ, et al. The contribution of cellulosomal scaffoldins to cellulose hydrolysis by Clostridium thermocellum analyzed by using thermotargetrons. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2014;7:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooft RW, Vriend G, Sander C, Abola EE. Errors in protein structures. Nature. 1996;381:272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israeli‐Ruimy V, Bule P, Jindou S, Dassa B, Moraïs S, Borovok I, et al. Complexity of the Ruminococcus flavefaciens FD‐1 cellulosome reflects an expansion of family‐related protein‐protein interactions. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo JA, Goodwin L, Davenport KW, Teshima H, Bruce D, Detter C, et al. Complete genome sequence of Clostridium clariflavum DSM 19732. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;6:104–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindou S, Soda A, Karita S, Kajino T, Béguin P, Wu JH, et al. Cohesin‐dockerin interactions within and between Clostridium josui and Clostridium thermocellum: binding selectivity between cognate dockerin and cohesin domains and species specificity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9867–9874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Rullmannn JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK‐NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy‐Assaraf M, Voronov‐Goldman M, Rozman Grinberg I, Weiserman G, Shimon LJ, Jindou S, et al. Crystal structure of an uncommon cellulosome‐related protein module from Ruminococcus flavefaciens that resembles papain‐like cysteine peptidases. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhang H, Li D, Liu YJ, Bayer EA, Cui Q, et al. Structure of the transcription open complex of distinct σI factors. Nat Commun. 2023;14:6455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Li B, Feng Y, Cui Q. Consolidated bio‐saccharification: leading lignocellulose bioconversion into the real world. Biotechnol Adv. 2020;40:107535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechaly A, Fierobe HP, Belaich A, Belaich JP, Lamed R, Shoham Y, et al. Cohesin‐dockerin interaction in cellulosome assembly: a single hydroxyl group of a dockerin domain distinguishes between nonrecognition and high affinity recognition. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9883–9888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meguro H, Morisaka H, Kuroda K, Miyake H, Tamaru Y, Ueda M. Putative role of cellulosomal protease inhibitors in Clostridium cellulovorans based on gene expression and measurement of activities. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:5527–5530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraïs S, Stern J, Artzi L, Fontes C, Bayer EA, Mizrahi I. Carbohydrate depolymerization by intricate cellulosomal systems. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2657:53–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash MA, Smith SP, Fontes CM, Bayer EA. Single versus dual‐binding conformations in cellulosomal cohesin‐dockerin complexes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2016;40:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nederveen AJ, Doreleijers JF, Vranken W, Miller Z, Spronk CA, Nabuurs SB, et al. RECOORD: a recalculated coordinate database of 500+ proteins from the PDB using restraints from the BioMagResBank. Proteins. 2005;59:662–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noach I, Frolow F, Jakoby H, Rosenheck S, Shimon LW, Lamed R, et al. Crystal structure of a type‐II cohesin module from the Bacteroides cellulosolvens cellulosome reveals novel and distinctive secondary structural elements. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pages S, Belaich A, Belaich JP, Morag E, Lamed R, Shoham Y, et al. Species‐specificity of the cohesin‐dockerin interaction between Clostridium thermocellum and Clostridium cellulolyticum: prediction of specificity determinants of the dockerin domain. Proteins. 1997;29:517–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phitsuwan P, Moraïs S, Dassa B, Henrissat B, Bayer EA. The cellulosome paradigm in an extreme alkaline environment. Microorganisms. 2019;7:347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro BA, Gilbert HJ, Sakka K, Sakka K, Fernandes VO, Prates JA, et al. Functional insights into the role of novel type I cohesin and dockerin domains from Clostridium thermocellum . Biochem J. 2009;424:375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro BA, Proctor MR, Martinez‐Fleites C, Prates JA, Money VA, Davies GJ, et al. The Clostridium cellulolyticum dockerin displays a dual binding mode for its cohesin partner. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18422–18430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman B, McKeown CK, Rodriguez M Jr, Brown SD, Mielenz JR. Transcriptomic analysis of Clostridium thermocellum ATCC 27405 cellulose fermentation. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincon MT, Dassa B, Flint HJ, Travis AJ, Jindou S, Borovok I, et al. Abundance and diversity of dockerin‐containing proteins in the fiber‐degrading rumen bacterium, Ruminococcus flavefaciens FD‐1. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakka K, Kishino Y, Sugihara Y, Jindou S, Sakka M, Inagaki M, et al. Unusual binding properties of the dockerin module of Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase CelJ (Cel9D‐Cel44A). FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;300:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakka K, Sugihara Y, Jindou S, Sakka M, Inagaki M, Sakka K, et al. Analysis of cohesin‐dockerin interactions using mutant dockerin proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;314:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer F, Matuschek M, Guglielmi G, Miras I, Alzari PM, Beguin P. Duplicated dockerin subdomains of Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase CelD bind to a cohesin domain of the scaffolding protein CipA with distinct thermodynamic parameters and a negative cooperativity. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2106–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz WH, Zverlov VV. Protease inhibitors in bacteria: an emerging concept for the regulation of bacterial protein complexes? Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1323–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Bax A. Protein structural information derived from NMR chemical shift with the neural network program TALOS‐N. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1260:17–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutzki M, Jobby MK, Chitayat S, Karpol A, Dassa B, Barak Y, et al. Intramolecular clasp of the cellulosomal Ruminococcus flavefaciens ScaA dockerin module confers structural stability. FEBS Open Bio. 2013;3:398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SP, Bayer EA. Insights into cellulosome assembly and dynamics: from dissection to reconstruction of the supramolecular enzyme complex. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:686–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SP, Bayer EA, Czjzek M. Continually emerging mechanistic complexity of the multi‐enzyme cellulosome complex. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;44:151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Chen C, Liu YJ, Dong S, Li J, Qi K, et al. Alternative σI/anti‐σI factors represent a unique form of bacterial σ/anti‐σ complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:5988–5997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CM, Rodriguez M Jr, Johnson CM, Martin SL, Chu TM, Wolfinger RD, et al. Global transcriptome analysis of Clostridium thermocellum ATCC 27405 during growth on dilute acid pretreated Populus and switchgrass. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Chen C, Wang Y, Dong S, Liu YJ, Li Y, et al. Discovery and mechanism of a pH‐dependent dual‐binding‐site switch in the interaction of a pair of protein modules. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabd7182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoav S, Barak Y, Shamshoum M, Borovok I, Lamed R, Dassa B, et al. How does cellulosome composition influence deconstruction of lignocellulosic substrates in Clostridium (Ruminiclostridium) thermocellum DSM 1313? Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhivin O, Dassa B, Moraïs S, Utturkar SM, Brown SD, Henrissat B, et al. Unique organization and unprecedented diversity of the Bacteroides (Pseudobacteroides) cellulosolvens cellulosome system. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2017;10:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zverlov VV, Kellermann J, Schwarz WH. Functional subgenomics of Clostridium thermocellum cellulosomal genes: identification of the major catalytic components in the extracellular complex and detection of three new enzymes. Proteomics. 2005;5:3646–3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting Information.