Abstract

Patient: Female, 22-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Adamantinoma

Symptoms: Leg pain

Clinical Procedure: En bloc resection

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Adamantinoma is a rare low-grade malignant bone tumor, usually found in the tibial diaphysis and metaphysis, with histological similarities to mandibular ameloblastoma. The most effective treatment of recurrent adamantinoma is not yet clear. This report is of a 22-year-old woman with recurrent tibial adamantinoma treated with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor pazopanib.

Case Report:

We report the case of a 22-year-old woman who was referred to our center for a suspicious bone lesion in the right tibia. Bone biopsy findings were consistent with an adamantinoma. En bloc resection was completed successfully, with no postoperative complications. Five years later, a positive emission tomography scan revealed mildly increased tracer uptake near the area of the previous lesion and in the right inguinal lymph node. Biopsies of the lesion and inguinal lymph node confirmed recurrence of the adamantinoma. Due to abdominal and pelvic metastasis, the patient underwent surgical debulking, along with an appendectomy, right salpingooophorectomy, intraoperative radiation therapy, and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Subsequently, the patient was placed on pazopanib for 4 months; however, her tumor continued to worsen after 4 months of chemotherapy. Currently, the patient is receiving gemcitabine and docetaxel as second-line medical therapy.

Conclusions:

This report showed that pazopanib as standalone treatment does not appear to have promising role on patient outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second report of pazopanib in the treatment of adamantinoma.

Keywords: Adamantinoma, Case Reports, Neoplasm Metastasis, Pazopanib, Recurrence

Introduction

Adamantinomas are malignant low-grade bone tumors usually found in the mid shaft of long tubular bones, with the tibia being the most common site of presentation [1]. This rare neoplasm constitutes up to 0.5% of primary skeletal tumors [1]. On histopathological analysis, adamantinomas are characterized by the presence of both epithelial and osteofibrous cells [2].

Imaging studies are essential for the diagnosis of adamantinomas [1]. X-rays can reveal an osteolytic lesion or multifocal radiolucencies surrounded by round densities, which create a characteristic “soap bubble” appearance” [3]. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), 2 morphological patterns have been described: a singular lobulated focus or several small nodules within multiple foci [4].

Due to the rarity of the tumor, there are no standardized treatment guidelines for adamantinoma. Choice of treatment is largely based on the findings of case reports and case series [5]. Adamantinomas are usually treated with surgical re-sections with wide margins [5]. However, the treatment of metastatic and recurrent adamantinoma remains debated [1]. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are considered ineffective for patients with adamantinoma [1]. Recently, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as sunitinib, have been tested in the treatment of adamantinomas, with promising outcomes [6,7].

Treatment with another tyrosine kinase inhibitor, pazopanib, has also been reported [8]. Pazopanib is an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor that inhibits vascular endothelial growth factors −1, −2, and −3 [9]. Pazopanib has been approved by several government bodies for the treatment of renal cell carcinomas and soft tissue sarcomas [9,10]. Cohen et al report the case of a 34-year-old woman with metastatic adamantinoma who was treated with pazopanib as third-line therapy [8]. While pazopanib induced a partial response, the patient’s tumor continued to progress after 6 months of treatment [8]. In this article, we report the case of a 29-year-old woman who received a diagnosis of recurrent metastatic adamantinoma, which progressed on pazopanib. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second reported case of an adamantinoma treated with pazopanib. This case report is written in accordance with the CARE guidelines [11].

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was referred to our center for further evaluation and management of right leg pain suspected to be a malignant neoplasm of bone and articular cartilage. An initial X-ray revealed a destructive bone lesion at the distal tibial medial cortex with a “shark bite” appearance extending into the soft tissue (Figure 1). An MRI scan of the lower limb revealed similar findings (Figure 2). The patient was subsequently shifted to the operating room for an open biopsy of the lesion.

Figure 1.

Destructive bone lesion noted at the distal tibial medial cortex with the “shark bite” appearance (arrow) and extending into the soft tissue with calcific focus posteriorly.

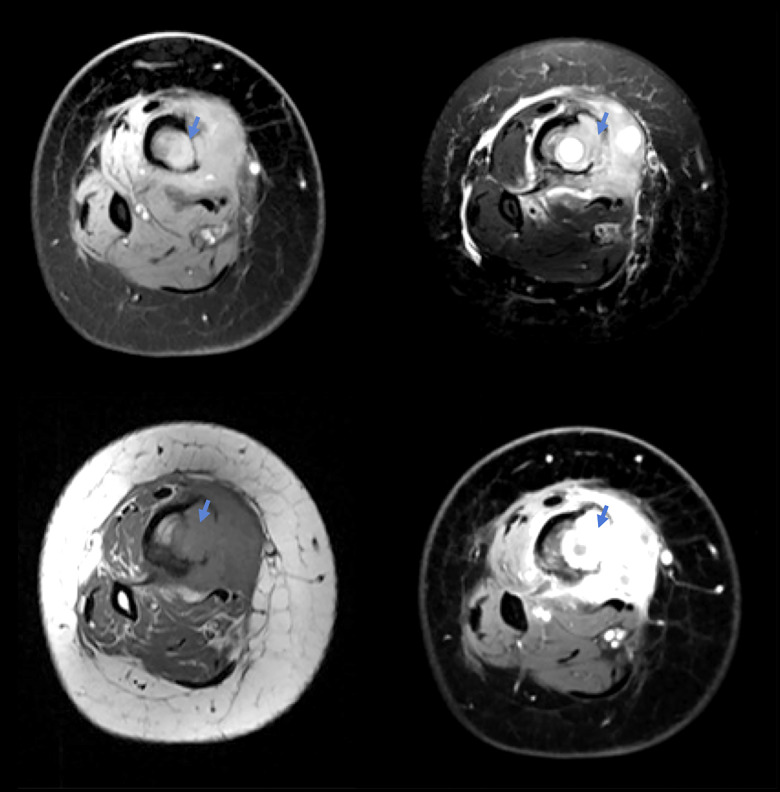

Figure 2.

Multiplanar, multi-sequential magnetic resonance imaging scan of the right femur and tibia showing in distal cuts a bone tumor (arrows).

Grossly, the tumor measured 8 cm in maximum dimension and extended along the posterior surface of the tibia. Microscopic examination was consistent with malignant adamantinoma, with hemorrhage, giant cells, and granulation tissue. Immunohistochemical studies showed that the tumor cells were positive for cytokeratins AE1/AE3 and 5/6 and tumor protein-63, further supporting and confirming the diagnosis of adamantinoma (Figure 3). The tumor was successfully excised through en bloc resection with cement reconstruction of the lesion with plate and screw fixation. There were no postoperative complications, and the patient was discharged with regular outpatient follow-ups.

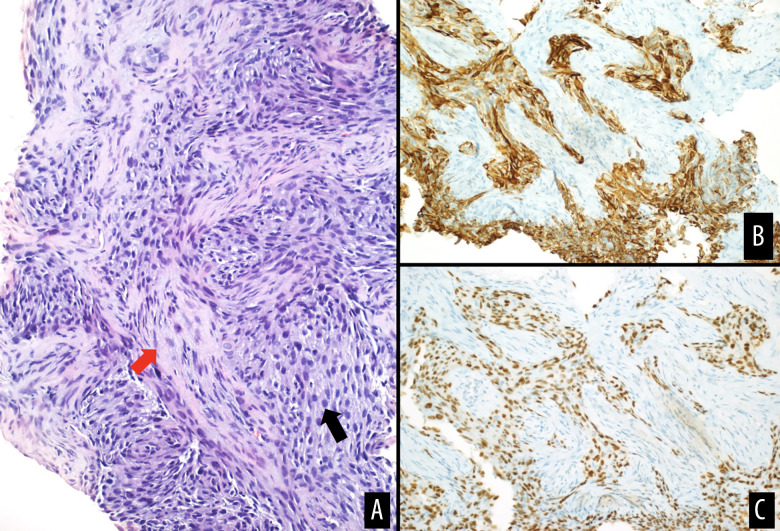

Figure 3.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained section showing atypical spindle to epithelioid cell proliferation (black arrow) with fibrotic stroma (red arrow), consistent with adamantinoma. Immunostaining for cytokeratins 5/6 (B) and p63 (C) showing positive staining in tumor cells.

Five years later, the patient presented once again to our center with acute shortness of breath, resulting from bilateral pulmonary embolism. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis (CT-CAP) revealed an incidental large, suspicious asymptomatic right pelvic mass causing severe mass effect on the pelvic organs (Figure 4). Additionally, the CT-CAP demonstrated enlarged right inguinal lymph nodes (Figure 5), bilateral pleural effusion, and a prominent supraclavicular lymph node. An excisional biopsy of the inguinal lymph node was taken, confirming the recurrence of the adamantinoma.

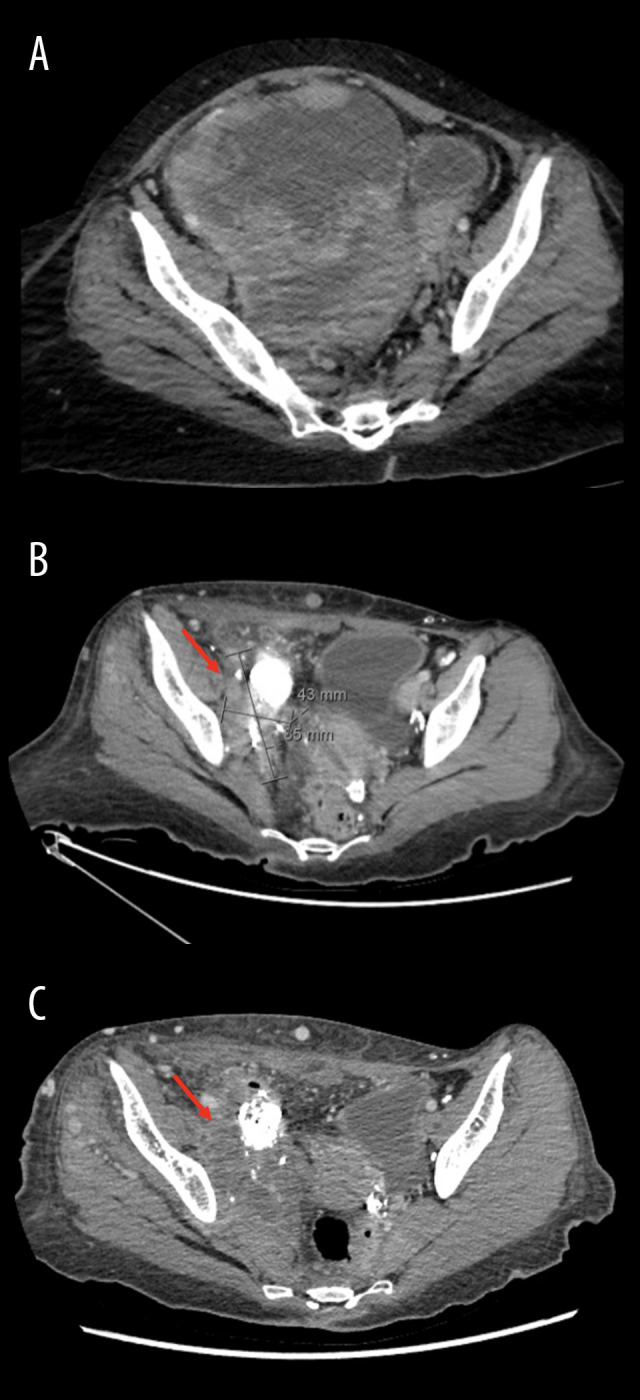

Figure 4.

Axial computed tomography revealing a large malignant pelvic mass (arrows) before surgery at presentation (A), after surgery (B), and after pazopanib (C).

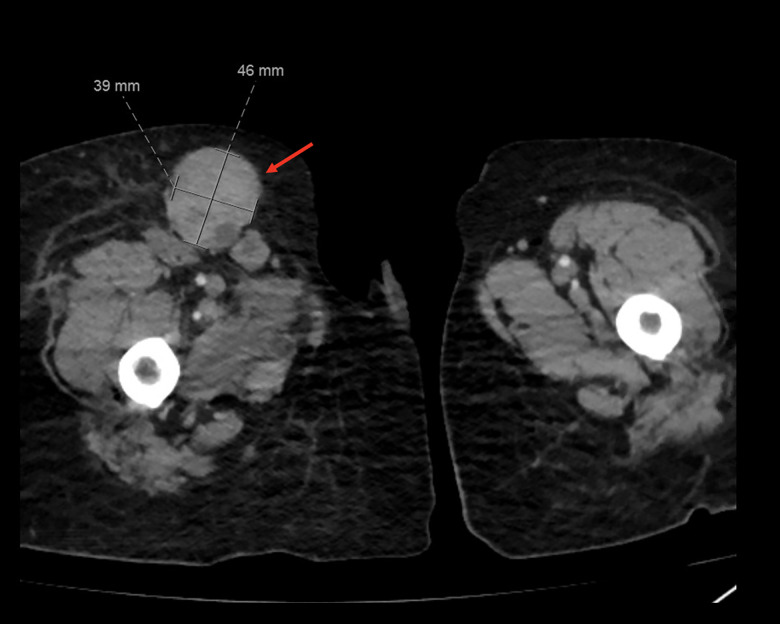

Figure 5.

Axial computed tomography showing an enlarged inguinal lymph node measuring 46×39 mm (arrow).

A positive emission tomography-CT showed increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the distal right tibia and inguinal lymph node, with no mediastinal spread. After clinical evaluation, the patient was labeled with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score of 4, indicating severe disability.

After the patient’s case was discussed with her and her family, chemotherapy was excluded due to the patient’s intolerance and the known resistance of the tumor. Radiation therapy was also ruled out due to the large size of the tumor. The team concluded that surgical debulking, along with an appendectomy, right salpingo-oophorectomy, intraoperative radiation therapy, and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, would be performed, due to the pelvic and mediastinal spread. A postoperative CT-CAP demonstrated partial response of the pelvic mass (Figure 4). However, resection of the tumor was incomplete, and there was an increase in the size of the right inguinal lymph node and adjacent areas of necrosis. The patient also developed lymphedema as a complication of the surgery.

Consequently, the patient was placed on a trial of pazopanib, based on recommendations from a previous case report [8]. We opted to reduce the dosage of pazopanib to 600 mg due to the patient’s poor ECOG performance status of 4 and concerns regarding compliance. Following the administration of 600 mg of pazopanib once daily for 4 months, there was remarkable improvement in the patient’s laboratory test results, including an increase in red blood cell count, hemoglobin, and hematocrit, as well as a decrease in alanine transaminase. Additionally, the patient’s ECOG performance score improved to 2. However, imaging revealed an increase in the size of the primary lesion, along with compression of the distal ureter, causing hydronephrosis (Figure 4). Additional findings included an increase in the metastatic and inguinal lymphadenopathy, as well as destruction of the right acetabulum. Right nephrostomy tube insertion was performed to treat the hydronephrosis. Currently, pazopanib has been stopped, and she is planned for cycle 1 of gemcitabine and docetaxel.

Discussion

In this case, we presented the clinical timeline of a patient with recurrent adamantinoma, which metastasized to the abdomen and peritoneum. Unfortunately, pazopanib did not hinder tumor progression, and the patient proceeded to second-line medical therapy.

An adamantinoma is a rare, biphasic, slow-growing malignant tumor composed of epithelial cells and osteo-fibrous tissue [1]. The tumor most commonly affects patients between the ages of 20 to 50 years [12]. The tibia remains the most common site of growth for the tumor, constituting up to 85% of cases [1,13]. Although the tumor’s origin is still unknown, the most widely accepted theory is that trapping of the skin basal epithelium in the anterior tibia during embryological development forms the origin of this neoplasm [1]. Additionally, some genetic studies have identified trisomies of chromosomes 7, 8, 9, 12, 19, and 21 in patients with adamantinoma, which is also thought to play a role in the development of the neoplasm [1].

The slow-growing characteristics of an adamantinoma allow it to have a favorable prognosis when diagnosis is made early [1]. Nonetheless, survival rates decrease substantially following metastasis of the neoplasm [1]. Prognosis after en bloc excision of the tumor with limb salvage seems promising, with 5- and 10-year survival rates reported to be 98.8% and 87.2%, respectively [1]. Local recurrence rates range between 18% and 32% of diagnosed cases [3]. Metastasis of the neoplasm occurs in 15% to 30% of patients, most frequently to the lungs and lymph nodes [3].

Due to its infrequency, adamantinoma lacks standardized therapeutic guidelines. Historically, the only treatment choice available was amputation of the severed limb [1,13]. However, the current favored treatment option is en bloc resection with limb salvage, due to prolonged postoperative survival rates [1,13]. As seen in our case, en bloc resection may have been ineffective due to the presence of residual tumor postoperatively. Therefore, authors recommend widening surgical margins during adamantinoma resection [1,13].

Chemotherapy has very limited success in the management of adamantinomas [14]. Hazelbag et al reported no benefit of chemotherapy on survival outcomes of patients [15]. Some studies have found that chemotherapy promotes disease stability for few months, before the tumor further progresses shortly after [8,16]. Lokich reported one of the only cases of response to medical treatment in patients with adamantinoma, in which the tumor showed regression on 2 separate occasions to etoposide plus cisplatin or carboplatin [17]. Recently, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as pazopanib and sunitinib, have been reportedly used as new treatment options [7,8]. Sunitinib has been used in the treatment of adamantinoma twice in the literature [6,7]. One patient demonstrated partial response [6], while the other showed stable disease at the last follow-up [7].

Only one case of pazopanib use in the treatment of adamantinoma has been reported in the literature. Cohen et al describe a case of a 34-year-old woman with metastatic adamantinoma to the lungs, which was treated with pazopanib as third-line therapy [8]. Ten weeks after initiation of the treatment, the patient demonstrated partial response [8]. However, the patient’s condition progressed both clinically and radiologically after 6 months of pazopanib treatment [8]. On the contrary, our patient received pazopanib as the first-line medical treatment. Furthermore, our patient had only peritoneal metastasis, rather than that of the lung. A similar clinical outcome was seen in our patient, demonstrating the ineffectiveness of pazopanib as standalone therapy. Further research is needed to identify novel therapeutic modalities that effectively cure adamantinomas.

Conclusions

In this article, we presented the case of a patient with a tibial adamantinoma who underwent en bloc excision of the tumor.

The patient then had recurrent metastatic adamantinoma. The patient was treated with pazopanib for 4 months and continued to worsen, despite treatment. Pazopanib does not appear to have a promising role in adamantinomas.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher

Department and Institution Where Work Was Done

Department of Medical Oncology, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Varvarousis DN, Skandalakis GP, Barbouti A, et al. Adamantinoma: An updated review. In Vivo. 2021;35(6):3045–52. doi: 10.21873/invivo.12600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dashti NK, Howe BM, Inwards CY, et al. High-grade squamous cell carcinoma arising in a tibial adamantinoma. Hum Pathol. 2019;91:123–28. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain D, Jain VK, Vasishta RK, et al. Adamantinoma: A clinicopathological review and update. DiagnPathol. 2008;3(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van der Woude HJ, Hazelbag HM, et al. MRI of adamantinoma of long bones in correlation with histopathology. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(6):1737–44. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.6.01831737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Most MJ, Sim FH, Inwards CY. Osteofibrous dysplasia and adamantinoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(6):358–66. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201006000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liman AD, Liman AK, Shields J, et al. A case of metastatic adamantinoma that responded well to sunitinib. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2016;2016:5982313. doi: 10.1155/2016/5982313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dudek AZ, Murthaiah PK, Franklin M, Truskinovsky AM. Metastatic adamantinoma responds to treatment with receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Acta Oncol. 2010;49(1):101–4. doi: 10.3109/02841860902913579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen Y, Cohen JE, Zick A, et al. A case of metastatic adamantinoma responding to treatment with pazopanib. Acta Oncologica. 2013;52(6):1229–30. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.770921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyamoto S, Kakutani S, Sato Y, et al. Drug review: Pazopanib. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48(6):503–13. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyy053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verweij J, Sleijfer S. Pazopanib, a new therapy for metastatic soft tissue sarcoma. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14(7):929–35. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2013.780030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, et al. The CARE Guidelines: Consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Glob Adv Health Med. 2013;2(5):38–43. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2013.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lou Y, Li Y, Xu L, et al. Rapidly progressive classic adamantinoma of the spine: case report and literature review. Front Oncol. 2022;12:862243. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.862243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sahito B, Jatoi NN, Kumar D, et al. Understanding the rare bone tumor “ADAMANTINOMA”. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2021;33(Suppl. 1(4):S835–S40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smyth SL, Siddiqi A, Athanasou N, et al. Adamantinoma: A review of the current literature. J Bone Oncol. 2023;41:100489. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2023.100489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hazelbag HM, Taminiau AH, Fleuren GJ, Hogendoorn PC. Adamantinoma of the long bones. A clinicopathological study of thirty-two patients with emphasis on histological subtype, precursor lesion, and biological behavior. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76(10):1482–99. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199410000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Haelst UJ, de Haas van Dorsser AH. A perplexing malignant bone tumor. Highly malignant so-called adamantinoma or non-typical Ewing’s sarcoma. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1975;365(1):63–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00439285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lokich J. Metastatic adamantinoma of bone to lung: a case report of the natural history and the use of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1994;17(2):157–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]