Abstract

Purpose of review

To summarize the recent findings about the roles of scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) in immunity and discuss the underlying mechanisms by which SR-BI prevents immune dysfunctions.

Recent findings

SR-BI is well known as a high-density lipoprotein (HDL) receptor playing key roles in HDL metabolism and in protection against atherosclerosis. Recent studies have indicated that SR-BI is also an essential modulator in immunity. SR-BI deficiency in mice causes immune dysfunctions, including increased atherosclerosis, elevated susceptibility to sepsis, impaired lymphocyte homeostasis, and autoimmune disorders. SR-BI exerts its protective roles through a variety of HDL-dependent and HDL-independent mechanisms. SR-BI is also involved in hepatitis C virus cell entry. A deficiency of SR-BI in humanized mice has been shown to decrease hepatitis C virus infectivity.

Summary

SR-BI regulates immunity via multiple mechanisms and its deficiency causes numerous diseases. A comprehensive understanding of the roles of SR-BI in protection against immune dysfunctions may provide a therapeutic target for intervention against its associated diseases.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, dysfunctions, HDL, immunity, inflammation, sepsis, SR-BI

INTRODUCTION

Scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI or Scarb1) is a transmembrane protein most abundantly expressed in liver and steroidogenic tissues. SR-BI has a horse-shoe-like structure with two short cytoplasmic domains, two transmembrane domains, and a large extracellular loop [1]. Initially found able to bind ligands including modified low-density lipoprotein (LDL), naïve LDL, and anionic phospholipids [2,3], SR-BI was identified as a physiological high-density lipoprotein (HDL) receptor [4-6]. It modulates the selective uptake of cholesteryl ester from HDL, which plays a key role in HDL metabolism and reverse cholesterol transportation (RCT) [4,7-10,11■]. SR-BI also facilitates free cholesterol efflux from peripheral cells to HDL [12-15]. Furthermore, SR-BI participates in the HDL transport between blood and interstitial fluid. For instance, SR-BI is involved in the transcytosis of lipid-poor HDL across aortic endothelial cells to the periphery [16]. Likewise, in the process of HDL returning from the periphery to the blood via lymph [17■■,18■■], SR-BI plays a key role in mediating the transcytosis of HDL to enter lymphatic vessels [17■■]. Given the critical roles of SR-BI in regulating HDL metabolism, it is not surprising that SR-BI plays a protective role in atherosclerosis [19,20■■] (Fig. 1). Mutations in human SR-BI cause elevated plasma HDL concentration and are associated with female infertility and changes in cholesterol metabolism in macrophages and platelets, indicating a role of SR-BI in human diseases [21-24].

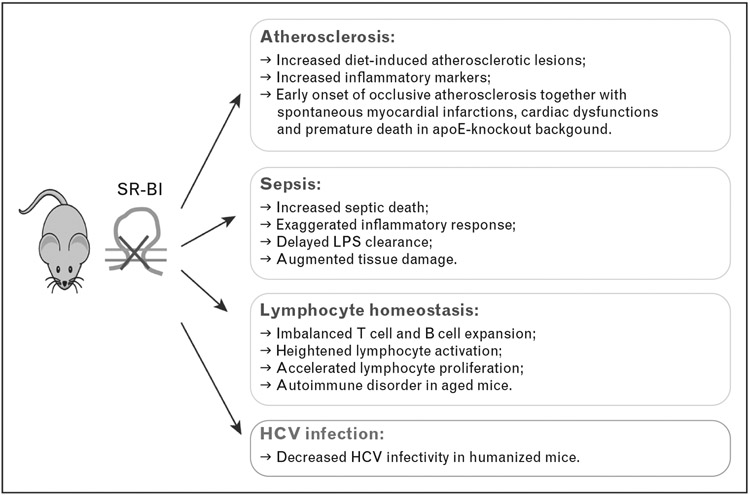

FIGURE 1.

Major immune phenotypes of SR-BI-deficient mice. SR-BI deficiency leads to immune dysfunctions, including increased atherosclerosis, elevated susceptibility to septic death, and impaired lymphocyte homeostasis. However, absence of SR-BI suppresses HCV infection. HCV, hepatitis C virus; SR-BI, scavenger receptor BI.

A body of evidence indicates that SR-BI is a multifunctional protein. In addition to mediating intracellular cholesterol uptake from HDL, SR-BI has been shown to activate endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in endothelial cells [25-28], induce apoptosis [29,30], modulate erythrocyte development [31,32] and platelet function [33-36], protect against lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced endotoxemia and polymicrobial bacteria-induced sepsis [37-39], and regulate lymphocyte homeostasis and autoimmunity [40]. Moreover, SR-BI is involved in pathogenesis of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection [41,42]. This review will focus on the types of SR-BI deficiency-induced immune dysfunctions and their underlying mechanisms (Fig. 1).

ROLE OF SCAVENGER RECEPTOR CLASS B TYPE I IN ATHEROSCLEROSIS

Atherosclerotic lesions represent a chronic inflammatory response against multiple risk agents such as cholesterol and oxidized LDL (oxLDL) [43-45]. Thus, atherosclerosis can be considered a disease of altered immunity. The protective role of SR-BI in atherosclerosis has been convincingly demonstrated, as shown by the findings that attenuation or ablation of SR-BI expression increases atherosclerosis in different atherosclerotic mouse models [46-49]; and SR-BI overexpression decreases the development of diet-induced fatty streak lesions [50]. The atheroprotective effects of SR-BI are largely attributed to the ability of hepatic SR-BI to mediate RCT. Hepatic overexpression of SR-BI accelerates RCT and reduces atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed LDL receptor-knockout mice [51,52]. Liver-specific deficiency or knockdown of SR-BI blocks RCT and accelerates atherosclerosis [53,54■,55]. Paradoxically, extremely high levels of overexpressed SR-BI in liver are also proatherogenic in mice; however, the underlying mechanisms remain to be clarified [50].

Numerous studies have shown that lacking SR-BI expression in hematopoietic cells contributes to elevated atherosclerosis, although this does not alter circulating cholesterol concentrations in mice [14,47,56,57■,58]. It is believed that the atheroprotective effects of hematopoietic SR-BI are primarily provided by macrophage SR-BI, as evidenced by impaired cholesterol homeostasis [59] and exaggerated cytokine secretion in SR-BI-deficient macrophages [38,39,57■]. Meanwhile, SR-BI-facilitated bidirectional cholesterol efflux influences foam cell formation. Though hematopoietic SR-BI deficiency does not cause foam cell accumulation alone, it exaggerates foam cell accumulation when hematopoietic adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter A1 is absent, suggesting that SR-BI may perform a compensatory route of cholesterol efflux to decrease foam cell formation [58,60].

In addition, SR-BI may be involved in HDL-mediated atheroprotective pathways. HDL can protect against atherosclerosis through its anti-oxidation properties, which are mainly attributed to two HDL-bound antioxidative enzymes, paraoxonase 1 (PON1) and platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH) [61-63]. SR-BI deficiency decreases PON1 and PAF-AH activity, causing an increased oxidative stress in mice [64]. SR-BI is also involved in the pathway in which PON1 directly dampens macrophage inflammatory responses [65■]. These data suggest that SR-BI deficiency may increase atherosclerosis by impairing anti-oxidation properties of HDL. Furthermore, SR-BI expression in endothelial cells may contribute to protection against atherosclerosis. Endothelial SR-BI mediates HDL-induced endothelial cell migration and repair [66], and activates eNOS to induce anti-atherogenic nitric oxide production in the presence of HDL [25-28].

ROLE OF SCAVENGER RECEPTOR CLASS B TYPE I IN SEPSIS

Sepsis is an exacerbated systemic inflammatory response induced by infections [67■]. It is a major health issue, claiming over 215 000 lives in the USA annually with a death rate exceeding 30% [68-70]. Our group first reported a protective role of SR-BI in sepsis [37,39]. LPS was shown to induce 90% fatality in SR-BI-deficient mice, whereas all wildtype littermates survived [37]; similarly, cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) induces 100% fatality in SR-BI-deficient mice, compared with only 21% fatality in wildtype littermates [39]. Associated with the increased septic death, SR-BI-deficient mice display uncontrolled inflammatory cytokine production, delayed LPS clearance, and augmented tissue damage [38,39]. These findings establish SR-BI as a critical protective molecule in sepsis. Findings from our laboratory and others further demonstrate that SR-BI exerts its protective functions through multiple mechanisms which are discussed below.

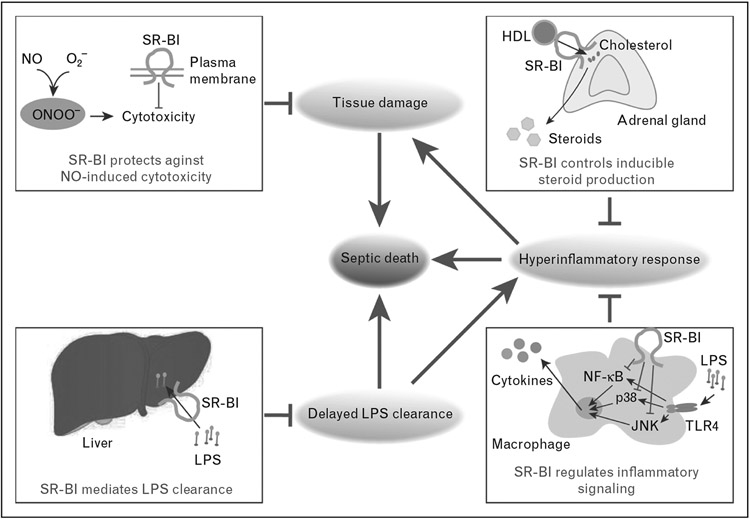

Scavenger receptor class B type I protects against nitric-oxide-induced cytotoxicity

In response to infections, the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase is markedly upregulated to generate high levels of nitric oxide, which are required for fighting against pathogens. However, excess nitric oxide is highly cytotoxic, causing cell damage and tissue injury [71]. Our earlier study demonstrated that SR-BI protects against nitric oxide-induced cytotoxicity: in cell lines, expression of SR-BI protects against sodium nitroprusside-induced cell death [37]; and in mice, absence of SR-BI leads to increased tyrosine nitrated proteins, representing more nitric oxide-induced damage [37]. The lack of SR-BI-mediated protection against nitric oxide-induced cytotoxicity is likely partly responsible for the increased tissue damage during sepsis in SR-BI-deficient mice (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Multiple protective roles of SR-BI in sepsis. SR-BI-deficient mice show elevated susceptibility to septic death associated with uncontrolled inflammatory response, delayed LPS clearance, and increased tissue injury. A number of possible mechanisms may contribute to the protective effects of SR-BI in sepsis. First, SR-BI protects against NO-induced cytotoxicity (up left), which prevents tissue damage. Second, adrenal SR-BI mediates the uptake of cholesterol ester from HDL to provide cholesterol for inducible steroid synthesis (up right), which keeps inflammatory responses under control. Third, macrophage SR-BI inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory signaling involving TLR4, JNK, p38, and NF-κB pathways (bottom right), which controls inflammatory cytokine production. Finally, hepatic SR-BI mediates LPS uptake and facilitates LPS clearance (bottom left), which alleviates inflammatory response. HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NO, nitric oxide; SR-BI, scavenger receptor BI.

Scavenger receptor class B type I mediates inducible glucocorticoid production

Glucocorticoids are markedly induced in response to septic stress and serve as potent inflammatory modulators during sepsis [72]. An earlier study demonstrated that SR-BI-mediated selective uptake of cholesterol from HDL is an essential pathway for adrenal glands to acquire cholesterol for glucocorticoid synthesis [73]. Notably, this pathway is critical for inducible glucocorticoid production: SR-BI-deficient mice exhibit normal physiological glucocorticoid concentrations but fail to produce inducible glucocorticoids in response to LPS [38], CLP [39], or prolonged fasting [74,75■■]. Given the potent effect of glucocorticoids in suppressing inflammatory response, it is plausible that the lack of inducible glucocorticoid production in SR-BI-deficient mice is responsible for the exaggerated inflammation and elevated septic death. Using an LPS endotoxic model, Cai et al. [38] showed that supplementation of corticosterone in drinking water 8h prior to LPS treatment suppresses LPS-induced cytokine production and protects against LPS-induced endotoxic animal death in SR-BI-deficient mice. Unexpectedly, supplementation of corticosterone following the same regimen fails to rescue SR-BI-deficient mice from CLP-induced septic death [39]. Corticosterone supplementation may have failed because glucocorticoids are a heterogeneous group of molecules with varied potency, half-life, and function [76,77], which work together to produce complementary effects. Simply supplementing one type of glucocorticoids may not effectively provide protection in sepsis. To test this speculation, we generated adrenal-specific SR-BI-null mice by adrenal transplantation. We found that the adrenal SR-BI wildtype mice are significantly more resistant to CLP-induced septic death than adrenal SR-BI-null mice (unpublished observation). Thus, SR-BI-mediated inducible glucocorticoid production plays a critical protective role in sepsis (Fig. 2).

Scavenger receptor class B type I modulates inflammatory response in macrophages

Macrophages are a major cell type responsible for cytokine production. SR-BI appears to play a role in modulating inflammatory signaling in macrophages (Fig. 2). Using bone marrow-derived macrophages and a HEK-Blue cell system, it has been shown that the expression of SR-BI suppresses inflammatory cytokine production in LPS-stimulated macrophages by modulating the TLR4–NF-κB pathway [39]. Further study demonstrated that the regulation of SR-BI involves JNK and P38 signaling pathways [78■]. Using a bone marrow transplantation mouse model, it was reported that hematopoietic SR-BI deficiency causes higher cytokine production in response to LPS, suggesting that macrophage SR-BI helps to control inflammatory response in vivo [78■]. The inhibitory effects of SR-BI on the macrophage inflammatory response may contribute to protection against septic death – for instance, overexpression of SR-BIC323G (a mutant SR-BI lacking activity for glucocorticoid generation but capable of suppressing TLR4–NF-κB signaling) in SR-BI-deficient mice significantly improves their survival under CLP challenge [39].

Scavenger receptor class B type I mediates lipopolysaccharide clearance

Like other scavenger receptors, SR-BI not only scavenges unwanted self-molecules, but also recognizes and mediates the removal of nonself molecules [79-82]. LPS is one of the nonself ligands of SR-BI [83]. More than recognizing LPS, SR-BI is able to mediate the uptake of LPS [83]. SR-BI-deficient hepatocytes display decreased ability to uptake LPS in vitro, and SR-BI-deficient mice have decreased hepatic LPS uptake and increased plasma LPS retention after LPS injection [38]. The delayed LPS clearance is also observed in the CLP model in SR-BI-deficient mice [39] (Fig. 2). Interestingly, during the early stage of sepsis, SR-BI-deficient mice display lower plasma LPS concentrations than wildtype mice, suggesting that SR-BI-mediated LPS uptake may be essential for transporting the LPS from the inflammation site to circulation [39]. In addition to LPS, SR-BI can also mediate the uptake of Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria, and lipoteichoic acid, the key component of Gram-positive cell walls [84]. In one report, it was claimed that when glucocorticoids and mineralcorticoids are supplemented in the presence of antibiotics, SR-BI-deficient mice show reduced bacterial load associated with an increase in survival upon CLP [85]. However, this study seems to be problematic because of its inappropriate experimental approaches [86]. For example, C57BL/6N mice, which are much more susceptible to CLP-induced septic death than mice in mixed background, were used as controls of SR-BI-deficient mice in C57BL/6J/129 mixed background [86]. In addition, dexamethasone was administered 24h prior to CLP, which completely abolishes adrenal SR-BI expression in wildtype controls [87]. This study essentially compared two groups of mice that are different in background, but both lack adrenal SR-BI expression when challenged with CLP. Nevertheless, further investigation is required to determine the contribution of SR-BI-mediated uptake of bacteria in sepsis.

ROLE OF SCAVENGER RECEPTOR CLASS B TYPE I IN LYMPHOCYTE HOMEOSTASIS AND AUTOIMMUNITY

In the recent years, several players in RCT have been identified as modulators in adaptive immunity [62,88-92]. The roles of SR-BI in adaptive immunity were also revealed using SR-BI-deficient mice [40]. SR-BI-deficient mice display splenomegaly and significant splenic lymphocyte expansions. Interestingly, the lymphocyte expansions are imbalanced, as shown by a 30% decrease in T/B cell ratio. SR-BI deficiency also causes lymphocyte hyperactivation and hyperproliferation. As a consequence of impaired lymphocyte homeostasis, the aged SR-BI-deficient mice exhibit profound autoimmune disorders [40]. These findings demonstrate that SR-BI is essential in maintaining lymphocyte homeostasis and preventing autoimmune disorders.

The adaptive immune defects in SR-BI-deficient mice are at least partly attributed to their abnormal HDL particles, which are larger in size and characterized by the accumulation of free cholesterol [6]. Functionally, SR-BI-deficient HDL shows reduced ability to mediate selective cholesterol uptake [93], as well as decreased antioxidative enzyme activity [64], and it is responsible for female infertility [94,95]. This dysfunctional HDL partly loses its ability to inhibit anti-CD3-stimulated T-cell proliferation and LPS-induced B-cell proliferation, suggesting that SR-BI can modulate lymphocyte function by regulating HDL properties [40]. Intriguingly, we recently found that HDL promotes glucocorticoid-induced thymocyte apoptosis, but HDL from SR-BI-deficient mice completely loses this regulatory activity, providing another piece of evidence that SR-BI modulates adaptive immunity through regulating HDL functions (unpublished observation).

ROLE OF SCAVENGER RECEPTOR CLASS B TYPE I IN HEPATITIS C VIRUS INFECTION

Recent studies revealed that SR-BI mediates HCV entry [41], which questions whether SR-BI is always a beneficial molecule. The involvement of SR-BI in HCV entry was demonstrated by that down-regulating or blocking human SR-BI decreases HCV infectivity in cell lines [96-100]. In vivo, SR-BI was confirmed as an HCV entry factor: in mice genetically humanized for HCV infection, SR-BI deficiency reduces HCV infection [101]; and in mice with humanized livers, antibodies against SR-BI inhibit HCV infection [102■,103■]. Therefore, SR-BI is regarded as a potential target to treat HCV infection [104].

Initially, it was thought that SR-BI mediates HCV entry by binding HCV. However, later research indicated that binding of SR-BI to HCV may not be necessary for HCV entry (although human SR-BI is able to bind soluble E2 glycoprotein from HCV [105], it fails to recognize natural serum-derived HCV [106]; and mouse SR-BI, which is able to mediate HCV entry [101], cannot bind HCV [107]). Instead, the lipid transfer function of SR-BI seems to be essential in this process [41]. On one hand, HDL can enhance HCV cell entry, which is suppressed by blocking SR-BI-mediated lipid transfer [108,109]. On the other hand, very low-density lipoprotein and oxLDL, the other two ligands of SR-BI, inhibit HCV cell entry in an SR-BI-dependent manner [106,110]. Notably, SR-BI may also be important in initiating the host defense against HCV, as dendritic cells also depend on SR-BI to uptake HCV [111]. The detailed roles of SR-BI in HCV infection warrant further investigation.

CONCLUSION

SR-BI acts as a critical modulator of both innate and adaptive immunity, and its deficiency alters its immune response in a variety of diseases, including atherosclerosis, sepsis, and autoimmune disorders. It is worth noting that, in addition to directly modulating immunity, SR-BI may participate indirectly in modulating immunity through its role in regulating HDL metabolism, and a lack of SR-BI-mediated HDL metabolism may render HDL dysfunctional. Given the diversity of cell types that express SR-BI and the multiple ligands recognized by SR-BI that are yet uninvestigated, our understanding of the functions of SR-BI is just emerging. Further efforts are warranted to better understand the roles of SR-BI in regulating immunity and preventing immune dysfunction.

KEY POINTS.

SR-BI is well known as a HDL receptor playing key roles in HDL metabolism and in protection against atherosclerosis.

SR-BI is an essential immune modulator and its deficiency causes immune dysfunctions, including elevated susceptibility to sepsis, impaired lymphocyte homeostasis, and autoimmune disorders.

SR-BI is required for HCV infectivity.

Acknowledgements

Funding sources: This publication was made possible by the grant numbers R01GM085231, R01GM085231-2S1, and R01GM085231-5S1 from NIGMS or NIH. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS or NIH. This work was also supported by a grant from the Children’s Miracle Network.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

■ of special interest

■■ of outstanding interest

- 1.Krieger M. Scavenger receptor class B type I is a multiligand HDL receptor that influences diverse physiologic systems. J Clin Invest 2001; 108:793–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acton SL, Scherer PE, Lodish HF, Krieger M. Expression cloning of SR-BI, a CD36-related class B scavenger receptor. J Biol Chem 1994; 269:21003–21009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rigotti A, Acton SL, Krieger M. The class B scavenger receptors SR-BI and CD36 are receptors for anionic phospholipids. J Biol Chem 1995; 270:16221–16224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acton S, Rigotti A, Landschulz KT, et al. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science 1996; 271:518–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kozarsky KF, Donahee MH, Rigotti A, et al. Overexpression of the HDL receptor SR-BI alters plasma HDL and bile cholesterol levels. Nature 1997; 387:414–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigotti A, Trigatti BL, Penman M, et al. A targeted mutation in the murine gene encoding the high density lipoprotein (HDL) receptor scavenger receptor class B type I reveals its key role in HDL metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94:12610–12615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trigatti BL, Krieger M, Rigotti A. Influence of the HDL receptor SR-BI on lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2003; 23:1732–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoekstra M, Van Berkel TJ, Van Eck M. Scavenger receptor BI: a multipurpose player in cholesterol and steroid metabolism. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16:5916–5924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Out R, Hoekstra M, Spijkers JA, et al. Scavenger receptor class B type I is solely responsible for the selective uptake of cholesteryl esters from HDL by the liver and the adrenals in mice. J Lipid Res 2004; 45:2088–2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brundert M, Ewert A, Heeren J, et al. Scavenger receptor class B type I mediates the selective uptake of high-density lipoprotein-associated cholesteryl ester by the liver in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005; 25:143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meyer JM, Graf GA, van der Westhuyzen DR. New developments in selective cholesteryl ester uptake. Curr Opin Lipidol 2013; 24:386–392. ■ This review discusses the current findings on selective lipid uptake.

- 12.Ji Y, Jian B, Wang N, et al. Scavenger receptor BI promotes high density lipoprotein-mediated cellular cholesterol efflux. J Biol Chem 1997; 272:20982–20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jian B, de la Llera-Moya M, Ji Y, et al. Scavenger receptor class B type I as a mediator of cellular cholesterol efflux to lipoproteins and phospholipid acceptors. J Biol Chem 1998; 273:5599–5606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Eck M, Bos IS, Hildebrand RB, et al. Dual role for scavenger receptor class B, type I on bone marrow-derived cells in atherosclerotic lesion development. Am J Pathol 2004; 165:785–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vergeer M, Korporaal SJ, Franssen R, et al. Genetic variant of the scavenger receptor BI in humans. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohrer L, Ohnsorg PM, Lehner M, et al. High-density lipoprotein transport through aortic endothelial cells involves scavenger receptor BI and ATP-binding cassette transporter G1. Circ Res 2009; 104:1142–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lim HY, Thiam CH, Yeo KP, et al. Lymphatic vessels are essential for the removal of cholesterol from peripheral tissues by SR-BI-mediated transport of HDL. Cell Metab 2013; 17:671–684. ■■ This study reports that HDL leaves the peripheral tissues and reaches blood via lymphatic vessels, and SR-BI mediates the HDL transport through lymphatic endothelium in that process.

- 18. Martel C, Li W, Fulp B, et al. Lymphatic vasculature mediates macrophage reverse cholesterol transport in mice. J Clin Invest 2013; 123:1571–1579. ■■ This study demonstrates that HDL leaves the peripheral tissues and reaches blood via lymphatic vessels.

- 19.Trigatti B, Covey S, Rizvi A. Scavenger receptor class B type I in high-density lipoprotein metabolism, atherosclerosis and heart disease: lessons from gene-targeted mice. Biochem Soc Trans 2004; 32:116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mineo C, Shaul PW. Functions of scavenger receptor class B, type I in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol 2012; 23:487–493. ■■ This article reviews the multiple functions of SR-BI in protecting against atherosclerosis.

- 21.Brooke AM, Kalingag LA, Miraki-Moud F, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) replacement reduces growth hormone (GH) dose requirement in female hypopituitary patients on GH replacement. Clin Endocrinol 2006; 65:673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casson PR, Santoro N, Elkind-Hirsch K, et al. Postmenopausal dehydroepiandrosterone administration increases free insulin-like growth factor-I and decreases high-density lipoprotein: a six-month trial. Fertil Steril 1998; 70:107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhavnani BR, Cecutti A, Dey MS. Biologic effects of delta-8-estrone sulfate in postmenopausal women. J Soc Gynecol Invest 1998; 5:156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunham LR, Tietjen I, Bochem AE, et al. Novel mutations in scavenger receptor BI associated with high HDL cholesterol in humans. Clin Genet 2011; 79:575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li XA, Titlow WB, Jackson BA, et al. High density lipoprotein binding to scavenger receptor, class B, type I activates endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in a ceramide-dependent manner. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:11058–11063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuhanna IS, Zhu Y, Cox BE, et al. High-density lipoprotein binding to scavenger receptor-BI activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nat Med 2001; 7:853–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mineo C, Yuhanna IS, Quon MJ, Shaul PW. High density lipoprotein-induced endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activation is mediated by Akt and MAP kinases. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:9142–9149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gong M, Wilson M, Kelly T, et al. HDL-associated estradiol stimulates endothelial NO synthase and vasodilation in an SR-BI-dependent manner. J Clin Invest 2003; 111:1579–1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li XA, Guo L, Dressman JL, et al. A novel ligand-independent apoptotic pathway induced by scavenger receptor class B, type I and suppressed by endothelial nitric-oxide synthase and high density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:19087–19096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng H, Guo L, Gao H, Li XA. Deficiency of calcium and magnesium induces apoptosis via scavenger receptor BI. Life Sci 2011; 88:606–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holm TM, Braun A, Trigatti BL, et al. Failure of red blood cell maturation in mice with defects in the high-density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI. Blood 2002; 99:1817–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meurs I, Hoekstra M, van Wanrooij EJ, et al. HDL cholesterol levels are an important factor for determining the lifespan of erythrocytes. Exp Hematol 2005; 33:1309–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dole VS, Matuskova J, Vasile E, et al. Thrombocytopenia and platelet abnormalities in high-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008; 28:1111–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valiyaveettil M, Kar N, Ashraf MZ, et al. Oxidized high-density lipoprotein inhibits platelet activation and aggregation via scavenger receptor BI. Blood 2008; 111:1962–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brodde MF, Korporaal SJ, Herminghaus G, et al. Native high-density lipoproteins inhibit platelet activation via scavenger receptor BI: role of negatively charged phospholipids. Atherosclerosis 2011; 215:374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korporaal SJ, Meurs I, Hauer AD, et al. Deletion of the high-density lipoprotein receptor scavenger receptor BI in mice modulates thrombosis susceptibility and indirectly affects platelet function by elevation of plasma free cholesterol. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011; 31:34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li XA, Guo L, Asmis R, et al. Scavenger receptor BI prevents nitric oxide-induced cytotoxicity and endotoxin-induced death. Circ Res 2006; 98:e60–e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cai L, Ji A, de Beer FC, et al. SR-BI protects against endotoxemia in mice through its roles in glucocorticoid production and hepatic clearance. J Clin Invest 2008; 118:364–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo L, Song Z, Li M, et al. Scavenger receptor BI protects against septic death through its role in Mmodulating inflammatory response. J Biol Chem 2009; 284:19826–19834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng H, Guo L, Wang D, et al. Deficiency of scavenger receptor BI leads to impaired lymphocyte homeostasis and autoimmune disorders in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011; 31:2543–2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burlone ME, Budkowska A. Hepatitis C virus cell entry: role of lipoproteins and cellular receptors. J Gen Virol 2009; 90:1055–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Popescu CI, Dubuisson J. Role of lipid metabolism in hepatitis C virus assembly and entry. Biol Cell 2010; 102:63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ross R. Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease. Am Heart J 1999; 138:S419–S420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansson GK, Robertson AK, Soderberg-Naucler C. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2006; 1:297–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galkina E, Ley K. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms of atherosclerosis (*). Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27:165–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huszar D, Varban ML, Rinninger F, et al. Increased LDL cholesterol and atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice with attenuated expression of scavenger receptor B1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000; 20:1068–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Covey SD, Krieger M, Wang W, et al. Scavenger receptor class B type I-mediated protection against atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-negative mice involves its expression in bone marrow-derived cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2003; 23:1589–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Eck M, Twisk J, Hoekstra M, et al. Differential effects of scavenger receptor BI deficiency on lipid metabolism in cells of the arterial wall and in the liver. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:23699–23705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Braun A, Trigatti BL, Post MJ, et al. Loss of SR-BI expression leads to the early onset of occlusive atherosclerotic coronary artery disease, spontaneous myocardial infarctions, severe cardiac dysfunction, and premature death in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circ Res 2002; 90:270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ueda Y, Gong E, Royer L, et al. Relationship between expression levels and atherogenesis in scavenger receptor class B, type I transgenics. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:20368–20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kozarsky KF, Donahee MH, Glick JM, et al. Gene transfer and hepatic overexpression of the HDL receptor SR-BI reduces atherosclerosis in the cholesterol-fed LDL receptor-deficient mouse. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000; 20:721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arai T, Wang N, Bezouevski M, et al. Decreased atherosclerosis in heterozygous low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice expressing the scavenger receptor BI transgene. J Biol Chem 1999; 274:2366–2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.El Bouhassani M, Gilibert S, Moreau M, et al. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein expression partially attenuates the adverse effects of SR-BI receptor deficiency on cholesterol metabolism and atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:17227–17238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Picataggi A, Lim GF, Kent AP, et al. A coding variant in SR-BI (I179N) significantly increases atherosclerosis in mice. Mamm Genome 2013; 24:257–265. ■ This study shows that a decrease of hepatic SR-BI expression reduces RCT and increases atherosclerosis.

- 55.Huby T, Doucet C, Dachet C, et al. Knockdown expression and hepatic deficiency reveal an atheroprotective role for SR-BI in liver and peripheral tissues. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:2767–2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang W, Yancey PG, Su YR, et al. Inactivation of macrophage scavenger receptor class B type I promotes atherosclerotic lesion development in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation 2003; 108:2258–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pei Y, Chen X, Aboutouk D, et al. SR-BI in bone marrow derived cells protects mice from diet induced coronary artery atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction. PLoS One 2013; 8:e72492. ■ This study provides new data supporting SR-BI in BMCs is protective against atherosclerosis.

- 58.Zhao Y, Pennings M, Hildebrand RB, et al. Enhanced foam cell formation, atherosclerotic lesion development, and inflammation by combined deletion of ABCA1 and SR-BI in bone marrow-derived cells in LDL receptor knockout mice on western-type diet. Circ Res 2010; 107:e20–e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yancey PG, Jerome WG, Yu H, et al. Severely altered cholesterol homeostasis in macrophages lacking apoE and SR-BI. J Lipid Res 2007; 48:1140–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao Y, Pennings M, Vrins CL, et al. Hypocholesterolemia, foam cell accumulation, but no atherosclerosis in mice lacking ABC-transporter A1 and scavenger receptor BI. Atherosclerosis 2011; 218:314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fisher EA, Feig JE, Hewing B, et al. High-density lipoprotein function, dysfunction, and reverse cholesterol transport. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012; 32:2813–2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu X, Parks JS. New roles of HDL in inflammation and hematopoiesis. Annu Rev Nutr 2012; 32:161–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barter PJ, Nicholls S, Rye KA, et al. Antiinflammatory properties of HDL. Circ Res 2004; 95:764–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Eck M, Hoekstra M, Hildebrand RB, et al. Increased oxidative stress in scavenger receptor BI knockout mice with dysfunctional HDL. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007; 27:2413–2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Aharoni S, Aviram M, Fuhrman B. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) reduces macrophage inflammatory responses. Atherosclerosis 2013; 228:353–361. ■ This study elucidates that PON1 directly inhibits macrophage inflammatory response in an SR-BI-dependent manner.

- 66.Seetharam D, Mineo C, Gormley AK, et al. High-density lipoprotein promotes endothelial cell migration and reendothelialization via scavenger receptor-B type I. Circ Res 2006; 98:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:840–851. ■ This review nicely summarizes the features and current treatment strategies of sepsis.

- 68.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001; 29:1303–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Riedemann NC, Guo RF, Ward PA. The enigma of sepsis. J Clin Invest 2003; 112:460–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Korhonen R, Lahti A, Kankaanranta H, Moilanen E. Nitric oxide production and signaling in inflammation. Current drug targets. Inflamm Allergy 2005; 4:471–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Annane D, Bellissant E, Bollaert PE, et al. Corticosteroids in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults: a systematic review. JAMA 2009; 301:2362–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Temel RE, Trigatti B, DeMattos RB, et al. Scavenger receptor class B, type I (SR-BI) is the major route for the delivery of high density lipoprotein cholesterol to the steroidogenic pathway in cultured mouse adrenocortical cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94:13600–13605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hoekstra M, Meurs I, Koenders M, et al. Absence of HDL cholesteryl ester uptake in mice via SR-BI impairs an adequate adrenal glucocorticoid-mediated stress response to fasting. J Lipid Res 2008; 49:738–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hoekstra M, van der Sluis RJ, Van Eck M, Van Berkel TJ. Adrenal-specific scavenger receptor BI deficiency induces glucocorticoid insufficiency and lowers plasma very-low-density and low-density lipoprotein levels in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013; 33:e39–e46. ■■ This study demonstrates the importance of adrenal SR-BI in glucocorticoid production in response to stress using adrenal transplantation model.

- 76.Han A, Marandici A, Monder C. Metabolism of corticosterone in the mouse. Identification of 11 beta, 20 alpha-dihydroxy-3-oxo-4-pregnen-21-oic acid as a major metabolite. J Biol Chem 1983; 258:13703–13707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Raubenheimer PJ, Young EA, Andrew R, Seckl JR. The role of corticosterone in human hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis feedback. Clin Endocrinol 2006; 65:22–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Cai L, Wang Z, Ji A, et al. Macrophage SR-BI regulates pro-inflammatory signaling in mice and isolated macrophages. J Lipid Res 2012; 53:1472–1481. ■ This study demonstrates that SR-BI regulates inflammatory signaling in macrophages.

- 79.Greaves DR, Gordon S. The macrophage scavenger receptor at 30 years of age: current knowledge and future challenges. J Lipid Res 2009; 50 (Suppl.):S282–S286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stephen SL, Freestone K, Dunn S, et al. Scavenger receptors and their potential as therapeutic targets in the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Int J Hypertens 2010; 2010:646929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Canton J, Neculai D, Grinstein S. Scavenger receptors in homeostasis and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2013; 13:621–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Areschoug T, Gordon S. Scavenger receptors: role in innate immunity and microbial pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol 2009; 11:1160–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vishnyakova TG, Bocharov AV, Baranova IN, et al. Binding and internalization of lipopolysaccharide by Cla-1, a human orthologue of rodent scavenger receptor B1. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:22771–22780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vishnyakova TG, Kurlander R, Bocharov AV, et al. CLA-1 and its splicing variant CLA-2 mediate bacterial adhesion and cytosolic bacterial invasion in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:16888–16893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leelahavanichkul A, Bocharov AV, Kurlander R, et al. Class B scavenger receptor types I and II and CD36 targeting improves sepsis survival and acute outcomes in mice. J Immunol 2012; 188:2749–2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guo L, Zheng Z, Ai J, et al. Comment on ‘Class B scavenger receptor types I and II and CD36 targeting improves sepsis survival and acute outcomes in mice’. J Immunol 2012; 189:501; author reply 502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rigotti A, Edelman ER, Seifert P, et al. Regulation by adrenocorticotropic hormone of the in vivo expression of scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI), a high density lipoprotein receptor, in steroidogenic cells of the murine adrenal gland. J Biol Chem 1996; 271:33545–33549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sorci-Thomas MG, Thomas MJ. High density lipoprotein biogenesis, cholesterol efflux, and immune cell function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012; 32:2561–2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wilhelm AJ, Zabalawi M, Grayson JM, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I and its role in lymphocyte cholesterol homeostasis and autoimmunity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009; 29:843–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wilhelm AJ, Zabalawi M, Owen JS, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I modulates regulatory T cells in autoimmune LDLr−/−, ApoA-I−/− mice. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:36158–36169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Armstrong AJ, Gebre AK, Parks JS, Hedrick CC. ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 negatively regulates thymocyte and peripheral lymphocyte proliferation. J Immunol 2010; 184:173–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bensinger SJ, Bradley MN, Joseph SB, et al. LXR signaling couples sterol metabolism to proliferation in the acquired immune response. Cell 2008; 134:97–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brundert M, Heeren J, Bahar-Bayansar M, et al. Selective uptake of HDL cholesteryl esters and cholesterol efflux from mouse peritoneal macrophages independent of SR-BI. J Lipid Res 2006; 47:2408–2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Miettinen HE, Rayburn H, Krieger M. Abnormal lipoprotein metabolism and reversible female infertility in HDL receptor (SR-BI)-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 2001; 108:1717–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yesilaltay A, Morales MG, Amigo L, et al. Effects of hepatic expression of the high-density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI on lipoprotein metabolism and female fertility. Endocrinology 2006; 147:1577–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bartosch B, Vitelli A, Granier C, et al. Cell entry of hepatitis C virus requires a set of co-receptors that include the CD81 tetraspanin and the SR-B1 scavenger receptor. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:41624–41630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zeisel MB, Koutsoudakis G, Schnober EK, et al. Scavenger receptor class B type I is a key host factor for hepatitis C virus infection required for an entry step closely linked to CD81. Hepatology 2007; 46:1722–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Catanese MT, Graziani R, von Hahn T, et al. High-avidity monoclonal antibodies against the human scavenger class B type I receptor efficiently block hepatitis C virus infection in the presence of high-density lipoprotein. J Virol 2007; 81:8063–8071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Grove J, Huby T, Stamataki Z, et al. Scavenger receptor BI and BII expression levels modulate hepatitis C virus infectivity. J Virol 2007; 81:3162–3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lavillette D, Tarr AW, Voisset C, et al. Characterization of host-range and cell entry properties of the major genotypes and subtypes of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2005; 41:265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dorner M, Horwitz JA, Robbins JB, et al. A genetically humanized mouse model for hepatitis C virus infection. Nature 2011; 474:208–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Lacek K, Vercauteren K, Grzyb K, et al. Novel human SR-BI antibodies prevent infection and dissemination of HCV in vitro and in humanized mice. J Hepatol 2012; 57:17–23. ■ This study shows that in mice with humanized liver, antibodies against SR-BI can prevent HCV infection.

- 103. Meuleman P, Catanese MT, Verhoye L, et al. A human monoclonal antibody targeting scavenger receptor class B type I precludes hepatitis Cvirus infection and viral spread in vitro and in vivo. Hepatology 2012; 55:364–372. ■ This study shows that in mice with humanized liver, antibodies against SR-BI can prevent HCV infection.

- 104.Rice CM. New insights into HCV replication: potential antiviral targets. Top Antivir Med 2011; 19:117–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Scarselli E, Ansuini H, Cerino R, et al. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J 2002; 21:5017–5025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Maillard P, Huby T, Andreo U, et al. The interaction of natural hepatitis C virus with human scavenger receptor SR-BI/Cla1 is mediated by ApoB-containing lipoproteins. FASEB J 2006; 20:735–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Catanese MT, Ansuini H, Graziani R, et al. Role of scavenger receptor class B type I in hepatitis C virus entry: kinetics and molecular determinants. J Virol 2010; 84:34–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dreux M, Pietschmann T, Granier C, et al. High density lipoprotein inhibits hepatitis C virus-neutralizing antibodies by stimulating cell entry via activation of the scavenger receptor BI. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:18285–18295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Voisset C, Callens N, Blanchard E, et al. High density lipoproteins facilitate hepatitis C virus entry through the scavenger receptor class B type I. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:7793–7799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Von Hahn T, Lindenbach BD, Boullier A, et al. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein inhibits hepatitis C virus cell entry in human hepatoma cells. Hepatology 2006; 43:932–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Barth H, Schnober EK, Neumann-Haefelin C, et al. Scavenger receptor class B is required for hepatitis C virus uptake and cross-presentation by human dendritic cells. J Virol 2008; 82:3466–3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]