Abstract

The mechanosensitive channel of large conductance (MscL) acts as an “emergency release valve” that protects bacterial cells from acute hypoosmotic stress, and it serves as a paradigm for studying the mechanism underlying the transduction of mechanical forces. MscL gating is proposed to initiate with an expansion without opening, followed by subsequent pore opening via a number of intermediate substates, and ends in a full opening. However, the details of gating process are still largely unknown. Using in vivo viability assay, single channel patch clamp recording, cysteine cross‐linking, and tryptophan fluorescence quenching approach, we identified and characterized MscL mutants with different occupancies of constriction region in the pore domain. The results demonstrated the shifts of constriction point along the gating pathway towards cytoplasic side from residue G26, though G22, to L19 upon gating, indicating the closed‐expanded transitions coupling of the expansion of tightly packed hydrophobic constriction region to conduct the initial ion permeation in response to the membrane tension. Furthermore, these transitions were regulated by the hydrophobic and lipidic interaction with the constricting “hot spots”. Our data reveal a new resolution of the transitions from the closed to the opening substate of MscL, providing insights into the gating mechanisms of MscL.

Keywords: constriction point, gating pore, gating substate, gating transitions, mechanosensitive channel, MscL, protien–lipid interaction

1. INTRODUCTION

The mechanosensitive channel of large conductance (MscL) is gated directly by the tension in the membrane to form a nonselective channel pore. It acts as a turgor‐operated emergency valve allowing rapid solute release and homeostatic adjustment when bacteria are challenged with acute osmotic downshock (Blount & Iscla, 2020; Cox et al., 2018; Sukharev et al., 1994). Due to its tractable nature, MscL has served as a paradigm for studying the mechanism underlying the force‐from‐lipid principle (Iscla & Blount, 2012; Martinac & Kung, 2022). Recently, modified MscL channels have been engineered to gate in response to ultrasound or pH, showing the potential applications as versatile tools in neuromodulation, tumor treatment, drug delivery, and nanodevices (Qiu et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2020, 2023; Yang et al., 2018; Ye et al., 2018).

Mycobacterium tuberculosis MscL (Mt‐MscL) is the first MscL channel to be crystalized and resolved in homopentameric forms with each subunit containing two transmembrane α helices (TM1 and TM2) linked by an extracellular loop (Chang et al., 1998; Figure S1a). However, Mt‐MscL was shown in several studies to be nonfunctional at physiological ranges due to the extremely high gating threshold when heterologously expressed in E. coli (Moe et al., 1998, 2000). Another resolved crystal structure is from Staphylococcus aureus MscL (Sa‐MscL). Sa‐MscL shows a similar TM1–Loop–TM2 frame to that of Mt‐MscL. Each subunit is composed of TM1 and TM2 helices, TM1 lines the channel pore and both N‐term and C‐term are facing cytoplasmic side. However, it forms a tetramer (Liu et al., 2009; Figure S1b). Later studies demonstrated that Sa‐MscL is a pentamer in vivo but of variable stoichiometries in vitro depending on the detergent used to solubilize the protein (Dorwart et al., 2010; Gandhi et al., 2011; Iscla et al., 2011a, 2011b). MscL was first identified from Escherichia coli and most MscL studies have been performed on the E. coli MscL (Ec‐MscL) orthologue. Results from disulfide‐crosslinking experiments, molecular dynamic simulation, electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, and electrostatic repulsion studies suggest an iris‐like movement of TMs in the gating process of the Ec‐MscL channel (Betanzos et al., 2002; Deplazes et al., 2012; Jeon & Voth, 2008; Levin & Blount, 2004; Li et al., 2009; Perozo, Cortes, et al., 2002; Perozo, Kloda, et al., 2002; Sawada et al., 2012; Sukharev, Betanzos, et al., 2001; Sukharev, Durell, & Guy, 2001; Tang et al., 2006). From the closed state to an estimated open‐pore size of ~30 Å in diameter, large structural rearrangement must occur to coordinate the channel gating.

According to the crystal structure, from the periplasmic side, a water‐filled lumen leads into a pore lined with TM1 residues that narrows towards cytoplasmic side at a hydrophobic constriction region to repel the water and restricts the permeation (Figure S1c). Mutagenesis experiments and electrophysiological studies in Ec‐MscL suggested that residues from L19 to G26 in the TM1 form a constriction region (Bartlett et al., 2004, 2006). Substitutions of hydrophilic or charged residue in the constriction region have been shown to trigger Ec‐MscL channel gating at reduced tension (Yoshimura et al., 1999). Reaction of charged sulfhydryl reagents such as [2‐(trimethylammonium)ethyl] methanethiosulfonate bromide (MTSET) to engineered cysteine mutant Ec‐G26C conferred spontaneously gated channels (Batiza et al., 2002; Birkner et al., 2012; Koçer et al., 2005; Yoshimura et al., 2001). These observations demonstrated that constriction region acts as a physical barrier or “gate” to occlude channels in the closed state and plays the crucial role for the MscL gating.

A structure‐based MD model presented by Sukharev and Guy proposed that the MscL channel gating is initiated with an expansion without opening, followed by subsequent pore opening via a number of intermediate substates, and ends in a full opening (Sukharev, Durell, & Guy, 2001). In this model, the separation of the tightly packed constriction region was thought to be the central step in the process. Functional analysis of gain‐of‐function (GOF) mutants revealed that some of them may exhibit a prominent low‐conducting substate, representing conformational intermediates of the gating process (Anishkin et al., 2005). However, the coupling of the separation of the pore constriction and the specific gating transitions has not been demonstrated yet. The elucidation of the roles of construction region and constriction point in gating and the structural changes from the onset of channel activation and in subsequent intermediate states could be of utmost importance for our understanding of the gating mechanism of MscL. However, the structural rearrangements upon gating could not be accurately predicted based on structures resolved in nonconductive state (Chang et al., 1998; Li et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2009). The transitions from the closed state, though closed expanded, to the lowest sub‐conducting state, which was suggested as the major tension‐dependent step in this process, remains largely hypothetical (Chiang et al., 2004; Shapovalov & Lester, 2004; Sukharev et al., 1999). Channel gating is a continuous process, it remains somewhat challenging to capture the step of transitions experimentally.

Previous characterization of the pore constriction region of Ec‐MscL channel suggested G26 being the constriction point of the channel pore; however, little is known about the channel constriction of Sa‐MscL, an MscL homology with a sequence identity of 47% to Ec‐MscL. To determine the constriction point of Sa‐MscL channel and compare it to that of Ec‐MscL channel, may be a strategy to study the role of constriction region in the gating process of MscL channels.

In this study, we determined the constriction point of Sa‐MscL, but it is non‐conservative to that of Ec‐MscL. Then the chimeric experiments of two homologues revealed a “hot‐spot” in TMs that are involved in the stabilizing pore constricting conformation. Hydrophilic substitutions at the “hot‐spot” resulted in reduced gating tension and a cytoplasmic shift of the constriction point of Ec‐MscL. The observations led to the generation of an Ec‐MscL mutant that shows spontaneous low‐conducting substate transition. By disulfide‐crosslinking approach, we further demonstrated that the distance between the cysteine substitutions in the constriction region expands with the cytoplasmic shift of the constriction point. In addition, using tryptophan fluorescence quenching method, we revealed that the interaction of “hot‐spot” with lipids are involved in the gating process. Together, these findings present snapshots of the gating transition from the closed to open substates, which are coupled with the movement of pore constriction point and provide further insights into the gating mechanism of mechanosensitive channel.

2. RESULTS

2.1. The constriction point of Sa‐MscL is nonconservative to that of Ec‐MscL

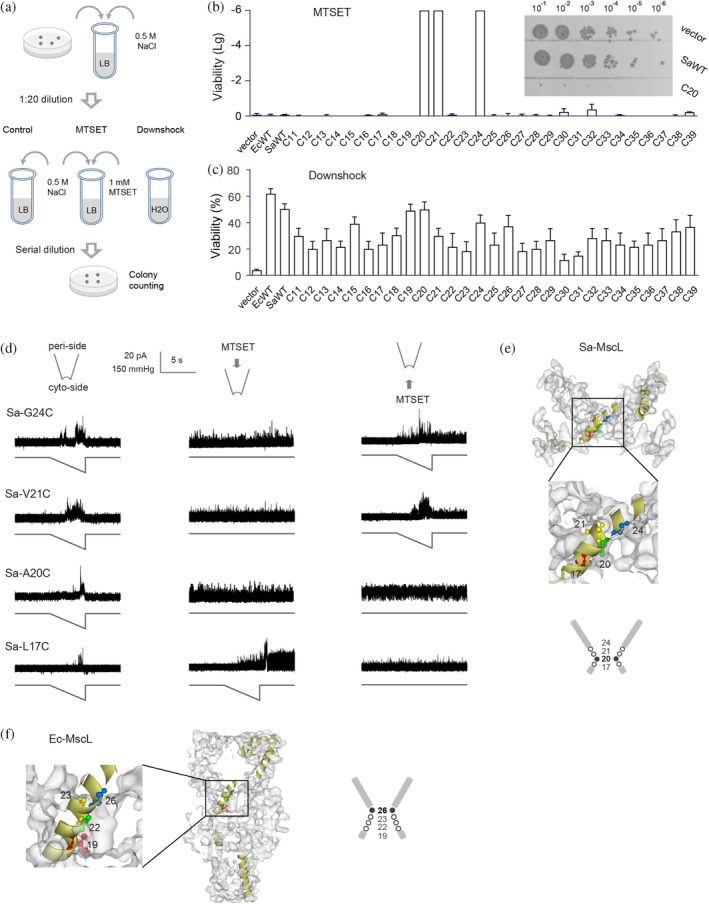

In an attempt to study the role of constriction region in the gating process of MscL channels, we determined the constriction point of Sa‐MscL channel and compared it to that of Ec‐MscL channel. An established in vivo viability assay was used to identify the residues lining the pore constriction of Sa‐MscL channel (Bartlett et al., 2004, 2006). Residues within the tight‐packed constriction are sensitive to the hydrophobic fluctuation of microenvironment. The assay is based on the fact that introduction of positively charged sulfhydryl reagent MTSET into the constriction through disulfide cross‐linking of cysteine could cause the channel to gate spontaneously. While spontaneous opening of a channel could conduct permanent leaking through the membrane which usually kills the bacteria, thus resulting in a severe GOF phenotype (Figure 1a). The x‐ray structure of Sa‐MscL indicates that the channel pore is formed by the TM1 helices (Liu et al., 2009), we then generated single cysteine mutants spanning Sa‐MscL TM1 (residues 11 to 39) and assessed for the viability when these mutants were expressed in an mscL − , mscS − , mscK − triple‐null strain (MJF465) and exposed to MTSET. The absence of endogenous cysteine residues in Sa‐MscL makes each substituted cysteine within the subunit unique. All the mutants grew normally and were functional in vivo, since expression of the mutants rescued the osmotic‐lysis phenotype of MJF465 on acute osmotic downshock alone (Figure 1c). However, when exposed to MTSET in the absence of osmotic downshock, mutants Sa‐A20C, Sa‐V21C, and Sa‐G24C exhibited extremely low viability (Figure 1b). These results outline the accessibility of MTSET within the pore area, suggesting that A20, V21, and G24 may line the constriction region and the periplasmic lumen of the pore likely ends at A20 in the closed Sa‐MscL channel.

FIGURE 1.

A20 is the constriction point of Sa‐MscL channel. (a) Schematic representation of the in vivo viability assay. Control group, MTSET group (cultured with 1 mM MTSET), and Downshock group (diluted the culture into pure water) were determined. (b) Viability of Sa‐MscL cysteine mutants grow in the presence of MTSET. Cysteine mutants within the TM1 (11–39) are tested. The insets show the representative growth of 5 μL of each tenfold dilution (10−1 to 10−6) on LB plates. The viability data of MTSET treatment relative to the control in logarithmic scale were subjected to statistical analysis. (c) Viability of Sa‐MscL cysteine mutants under osmotic downshock. Cysteine mutants within the TM1 (11–39) are tested. (d) Spontaneous channel activities are dependent on the accessibility of MTSET from the periplasmic (middle panel) or cytoplasmic (right panel) side of Sa‐MscL channel. Channel activities without MTSET treatment are shown in left panel. In each recording, upper trace is the current, and lower trace is the negative pressure. (e) The diagram of the pore constriction of Sa‐MscL is composed of G24, V21, A20, and L17. Filled circle and bold number show the constriction point of A20. Side view of Sa‐MscL (Protein Data Bank code 3HZQ) with surface schematically shows G24 (blue), V21 (yellow), A20 (green), and L17 (red) in ball and stick style on an individual subunit in yellow. (f) The diagram of the pore constriction of Ec‐MscL is composed of G26, V23, G22, and L19. Filled circle and bold number show the constriction point of G26. Side view of a modeling of Ea‐MscL structure (Sukharev, Betanzos, et al., 2001, derived from 2OAR) with surface schematically shows G26 (blue), V23 (yellow), G22 (green), and L19 (red) in ball and stick style on an individual subunit in yellow. SEM for each is shown, N = 5 independent experiments.

We then used inside‐out excised patch clamp recording from native bacteria membranes to further analyze the influences of MTSET on cysteine substitution of Sa‐MscL channel at A20, V21, and G24. Residue 17 (L17) of TM1 was also included for the study due to its proximity to the proposed constriction region that was revealed by X‐ray data (Liu et al., 2009). We found that Sa‐L17C, Sa‐A20C, Sa‐V21C, and Sa‐G24C exhibited typical pressure‐dependent MscL channel activity in the absence of MTSET (Figure 1d, left panel). However, when MTSET was applied exclusively to the periplasmic side (pipette side in the recording), spontaneous openings independent of mechanical stimulation were observed for Sa‐A20C, Sa‐V21C, and Sa‐G24C (Figure 1d, middle panel). Indeed, the loss of viability was seen for the cells expressing Sa‐A20C, Sa‐V21C, and Sa‐G24C in the in vivo viability assay (Figure 1b). In contrast, MTSET‐induced spontaneous activity in L17C could only be achieved subsequent to channel gating with pressure stimulation, suggesting that L17C is not accessible to MTSET from periplasmic side of the closed channel. The accessibility of MTSET from another side of channel was also examined (Figure 1d, right panel). Applying MTSET to the cytoplasmic side (bath side in the recording) evoked spontaneous activity after channel gating in L17C, A20C, V21C, and G24C, indicating the important role of these residues within the constriction region.

The distinct MTSET accessibility and gating properties of L17C, A20C, V21C, and G24C of Sa‐MscL confirmed the in vivo viability results and demonstrated that A20 serves as the constriction point in the channel pore of Sa‐MscL, blocking the access to MTSET for the residues that are cytoplasmic in the structure (Figure 1e).

2.2. Mutation of the residues at constricting “hot spot” in TMs leads to the movement of constriction point

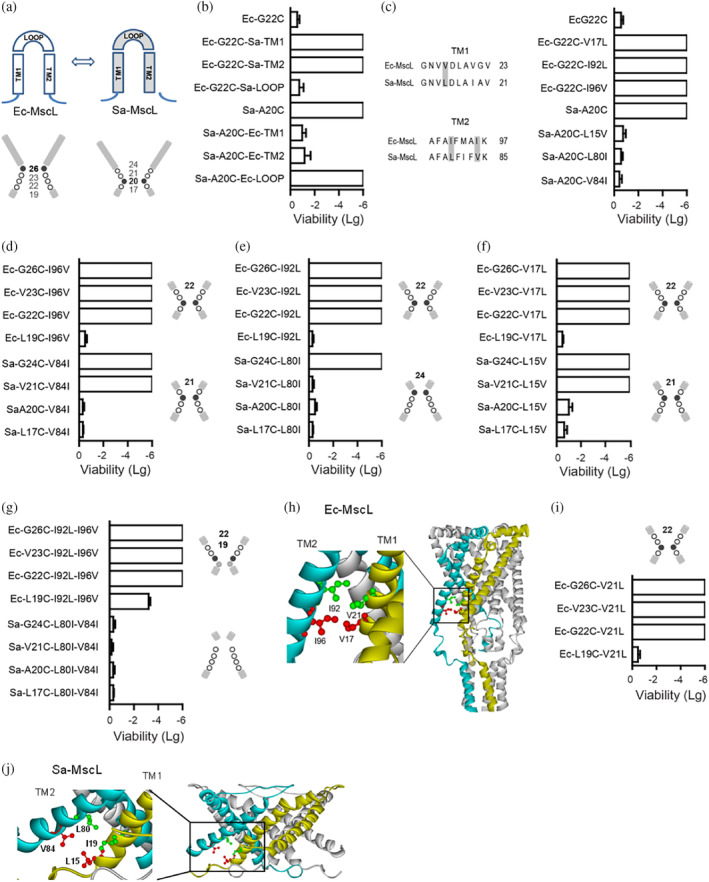

Structural modeling indicated that Ec‐MscL and Sa‐MscL share similar structural elements of TM1‐Loop‐TM2 (Figure 2a). Our studies revealed that the constricted pore region of Sa‐MscL is lined by the residues of L17–A20–V21–G24 in TM1 (Figure 1); the corresponding residues (L19–G22–V23–G26) in Ec‐MscL have been described previously to be crucial for channel gating (Bartlett et al., 2004, 2006). However, the Sa‐MscL constriction point (A20) shows a more cytoplasmic localization than that of Ec‐MscL (G26), implying that other residues beyond the constriction region may contribute to the structural organization (Figure 2a). To test this, we generated chimeras in which TM1, TM2, or Loop domains of Sa‐MscL and Ec‐MscL were exchanged, and determined the in vivo viability of the chimeric channels with single cysteine substitution (A20C in Sa‐MscL and corresponding G22C in Ec‐MscL) in the constriction region (Figure 2b). With TMs but not Loop replaced by relative Sa‐MscL domains, G22C mutated Ec‐MscL chimeras (Ec‐G22C‐Sa‐TM1 or Ec‐G22C‐Sa‐TM2) exhibited very low viability upon accessing MTSET from periplasmic vestibule in the absence of membrane tension. Similarly, the phenotype of A20C mutated Ec‐MscL chimeras (Sa‐A20C‐Ec‐TM1 and Sa‐A20C‐Ec‐TM2) converted from low viability to normal growth upon changing the TMs of Sa‐MscL with that of Ec‐MscL. These results suggest that a functional “hot spots” associated with pore constriction is located in TMs. We then exchanged individual amino acid of the TMs of two channels and identified that Ec‐V17 in TM1, Ec‐I92, and Ec‐I96 in TM2, and the corresponding residues of L15, L80, and V84 in Sa‐MscL, are involved to modify the pore constriction of MscL channels (Figure 2c).

FIGURE 2.

Identification of constricting “hot‐spots”. (a) The diagrams show the TM1, TM2, and LOOP domain (upper) and pore constriction (lower) of Ec‐MscL and Sa‐MscL, respectively. Filled cycle and bold number show the constriction point. (b) Replacements in the TMs but not LOOP domain affect the in vivo viability of the chimeras Ec‐G22C or Sa‐A20C. (c) Ec‐V17 (Sa‐L15) in the TM1, Ec‐I92, and Ec‐I96 (Sa‐L80 and Sa‐V84) in the TM2 induce the altered viability of Ec‐G22C or Sa‐A20C. (d–f) Viability assays show that exchanging the Ec‐I96 and the corresponding Sa‐V84 (d), the Ec‐I92 and the corresponding Sa‐L80 (e), the Ec‐V17 and the corresponding Sa‐L15 (f) lead to the movement of the constriction point. (g) Double mutants show further movement of the constriction point. (h) The proximity of Ec‐MscL V21 and I92, V17, and I96 revealed from a modeling of Ec‐MscL structure in closed state (Sukharev, Betanzos, et al., 2001, derived from 2OAR). V21 and V17 are shown in ball and stick style in red and green, respectively, on the subunit in yellow, and I96 and I92 on the adjacent subunit in blue, are shown in ball and stick style in red and green, respectively. (i) Substitution of Ec‐V21 to corresponding Sa‐L19 (Ec‐V21L) shifts the constriction point from G26 to G22. (j) The proximity of I19 and L80, L15, and V84 is shown in Sa‐MscL structure (Protein Data Bank code 3HZQ). I19 and L15 are shown in ball and stick style in red and green, respectively, on the subunit in yellow, and V84 and L80 on the adjacent subunit in blue, are shown in ball and stick style in red and green, respectively. Samples were exposed to 1 mM MTSET in the absence of osmotic downshock, then to analyze the viability. Data presented as mean ± SEM, n = 6 independent experiments.

We next investigated whether exchange of these residues could result in an alteration of constriction point. In vivo viability of single cysteine mutants in the constriction region (L19C, G22C, V23C, or G26C of Ec‐MscL and L17C, A20C, V21C, or G24C of Sa‐MscL) was examined for determining the constriction point of MscL channels. We found that G22C, V23C, and G26C mutants of Ec‐I96V (replace Ec‐I96 with corresponding Sa‐V84) exhibited nonviable phenotype whereas cysteine mutated Ec‐L19C–I96V grow normally, thus suggest that Valine substitution at I96 may lead to the movement of constriction point to G22 from G26, thereby blocking the accessibility of MTSET from periplasmic pore to L19C (Figure 2d). The shift of constriction point to G22 was also observed for Leucine substitutions at I92 (Ec‐I92 to Sa‐L80) and V17 (Ec‐V17 to Sa‐L15) in Ec‐MscL channel (Figure 2e,f). Interestingly, opposing to the cytoplasmic movement of constriction points in Ec‐MscL chimeric channels, an upward movement along the permeation pathway from A20 to V21 was found for Sa‐V84I, and a further periplasmically shifting to G24 was determined for Sa‐L80I. Moreover, when both 80I and V84 were mutated to Isoleucine (Sa‐L80I–V84I), all four single cysteine mutants of the double mutant exhibited normal viability, indicating that none of the residues (L17/A20/V21/G24) could act as constriction point in Sa‐L80I–V84I. Conversely, when both I92 and I96 were substituted in Ec‐MscL, a loss of viability was observed for G26C, V23C, or G22C mutated Ec‐I92L–I96V, and a low viability (−3.4 ± 0.2, compared to normal growth of other L19C mutants) for the Ec‐L19C–I92L–I96V, indicating that MTSET can be accessed beyond G22 site, and is partially accessible to L19C (Figure 2g).

In addition, the proximity of V21 and V17 to the adjacent I92 and I96 were observed from a modeling of Ec‐MscL structure in a closed state (Sukharev, Betanzos, et al., 2001), suggesting potential interactions between these residues (Figure 2h). Indeed, we found that the substitution of V21 to corresponding Sa‐L19 (Ec‐V21L) resulted in a channel with the pore constricted at G22, similar to that of mutants Ec‐I92L, Ec‐I92V, and Ec‐V17L (Figure 2i). Together, these data demonstrate that V17, V21, I92, and I96 are the constricting “hot spots” of Ec‐MscL, and modifications of the “hot spots” in TM1 or TM2 may lead to the movement of the constriction point.

2.3. The cytoplasmic movement of constriction point couples with reduced gating tension of MscL channels

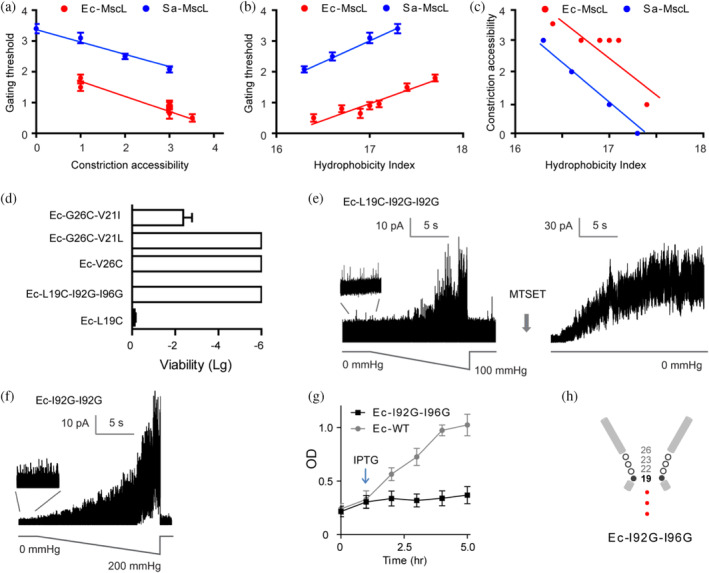

To examine whether the movement of constriction point would alter the gating property of the channel, we analyzed the mechanosensitivity of MscL channels by deriving gating threshold and constriction accessibility index for individual mutants (Table S2). The ratio of the pressure needed to open MscL channel relative to that required for control MscS channel, which is present in the same patch membrane, is defined as the MscL gating threshold. The number of residues among G26, V23, G22, and L19 in Ec‐MscL (G24, V21, A20, and L17 in Sa‐MscL) that are accessible to MTSET from periplasmic pore in the closed channel is defined as constriction accessibility index. We found that the constriction accessibility emerges into an inverse relationship with the gating threshold of McsL (Figure 3a). Thus, the deeper the constriction point located in the pore lumen toward the cytoplasma, the lower the pressure is required for channel gating. For wild‐type Ec‐MscL (constriction point at G26), the constriction accessibility index and gating threshold are 1 (G26) and 1.5 ± 0.12, respectively. With the constriction point moved to G22 in mutants such as Ec‐V17L, the constriction accessibility increases to 3 (G26, V23, and G22), whereas the gating threshold decreases to 0.65 ± 0.07. When the constriction point of double mutant Ec‐I92L‐I96V shifted further away from G26 to near L19, the constriction accessibility increased close to 4, while the gating threshold reduced to 0.5 ± 0.09, only one‐third of that of the WT‐MscL. These results suggest that the cytoplasmic movement of constriction point is in the MscL gating pathway.

FIGURE 3.

The occupation of constriction point at Ec‐L19 confers spontaneous gating. (a) MscL gates with less pressure upon the cytoplasmic shift of constriction point. (b) Hydrophilic substitution at V17, V21, I92, or I96 of Ec‐MscL increases the channel mechanosensitivity. (c) Hydrophilic substitution at V17, V21, I92, or I96 of Ec‐MscL leads to the cytoplasmic shift of the constriction point. (d) The hydrophobic substitution (V21I) rescues the viability defects of Ec‐G26C, whereas the hydrophilic substitution (I92G–I96G) causes loss of viability in Ec‐L19C. (e) Ec‐L19C–I92G–I96G shows the spontaneous activities and multiple channel openings in the presence of MTSET. (f) Ec‐I92G–I96G gates spontaneously. (g) Ec‐I92G–I96G exhibits poor liquid growth as compared to that of Ec‐MscL upon growth induction with IPTG (1 mM, indicated by arrow). (h) Schematic illustration displays the occupation of constriction point at L19 resulting in a leaking channel. Data presented as mean ± SEM, n = 6 independent experiments.

2.4. Hydrophilic substitution in “hot spots” confers a spontaneously gated channel

We further evaluated the effects of hydrophobicity of “hot spots” on the MscL channel activity. The hydrophobicity score, which is given as the sum of the hydrophobicity of the residues at the positions of 17, 21, 92, and 96 in Ec‐MscL (relative positions of 15, 19, 80, and 84 in Sa‐MscL) according to the hydrophobicity scale of Kyte and Doolittle (1982), was used for the assessment. We found that hydrophobicity score correlated positively with the gating threshold but inversely with the constriction accessibility of the channel (Figure 3b, c). For example, substitution of Valine (hydrophobicity value at 4.2) with Leucine (hydrophobicity value at 3.8) at residue 21 (Ec‐V21L) led to a decreased hydrophobicity index of 17.0 and a lower gating threshold of 0.9 ± 0.12, but an increased constriction accessibility index of 3, as compared to the Ec‐WT. Similar correlation was seen for the MscL mutant of V17L as well as I92L and I96V, suggesting that V17, V21, I92, and I96 may form a hydrophobic pocket that is involved in the gating of MscL channels.

Ec‐MscL is the most functionally characterized member of the MscL, it has been proposed as a paradigm for study on the channel gating in response to the mechanical stimuli. Many hypotheses of MscL gating as well as their potential applications have been validated in Ec‐MscL. The results of pore constriction determined from Sa‐MscL provide clues to investigate the pore constriction of Ec‐MscL. We then focused the research on the gating transitions of Ec‐MscL underlying constriction point shift. To test whether the channel gating can be changed by controlling the hydrophobicity of the constricting “hot spots”, we replaced V21 with the most hydrophobic amino acid Isoleucine (hydrophobicity value at 4.5) in Ec‐MscL (Ec‐V21I). The V to I substitution caused an increase in hydrophobicity score to 17.7. Correlated positively with hydrophobicity, the gating threshold of Ec‐V21I increased to 1.8 ± 0.09 (Table S1). Moreover, in contrast to the loss of viability of Ec‐G26C, Ec‐G26C‐V21I exhibited viable growth (−2.3 ± 0.4; Figure 3d). The impacts on gating sensitivity are likely not resulted from the size of side chain, as substitution with Leucine (V21L) caused opposite effects on channel gating threshold and cell growth, given that Isoleucine and Leucine have almost identical van der Waals volume. Hence, hydrophobic fluctuation of “hot‐spot” may confer altered mechanosensivity.

These observations allow us to make the prediction that introducing hydrophilic residues to the positions of 17, 21, 92, and I96 may give rise to channels with increased mechanosensitivity and ultimately confer spontaneous channel opening. We then test the substitution with mild hydrophilic Alanine (hydrophobicity value of 1.8) and intermediate hydrophilic Glycine (hydrophobicity value of −0.4). Double mutant of Ec‐I92A–I96A exhibited more sensitive to the pressure than that of Ec‐I92L–I96V, with the gating threshold as low as 0.3 ± 0.11 (Table S1). Ec‐I92G–I96G could gate spontaneously in the absence of any pressure stimulation (Figure 3f). Cells expressing Ec‐I92G–I96G exhibited severe growth upon induction with IPTG, suggesting that spontaneous gating of the channel may cause permanent leaking through the membrane (Figure 3g). Furthermore, the constriction point fully occupying L19 was determined for Ec‐I92G–I96G, as the mutant exhibited an inviable phenotype and spontaneous channel activities with high open probability when periplasmically exposed to MTSET (Figure 3d,e). Hence, the occupation of L19 as the constriction point conducts a spontaneously gated channel (Figure 3h).

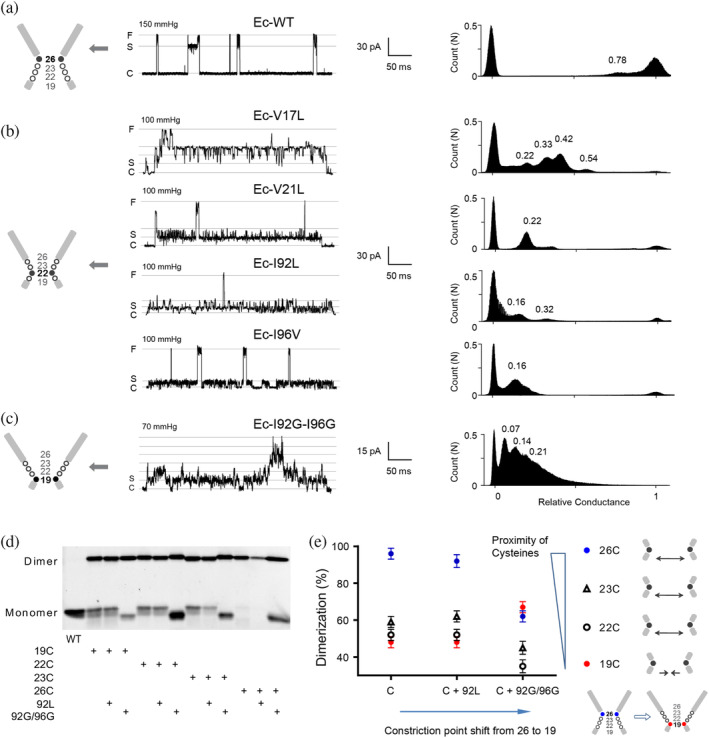

2.5. The mutant channels with altered constriction point stably occupy low‐conducting substates

Previous modeling studies proposed that the gating of MscL channels proceeds through the closed state to various intermediate low‐conducting substates followed by a transition to the fully open state (Sukharev, Durell, & Guy, 2001). The transient substates of intermediate opening with the conductance of 7%, 13%, 22%, 33%, 45%, 54%, 70%, 78%, and 93% relative to the fully open state (S0.07, S0.13, S0.22, S0.33, S0.45, S0.54, S0.70, S0.78, and S0.93) have been observed in the WT Ec‐MscL upon the application of membrane tension, but most of them rarely stay for more than 1 ms (Figure 4a,f). We found that Ec‐V17L, Ec‐V21L, Ec‐I92L, or Ec‐I96V stably occupied the low‐conducting substate of S0.16, S0.22, S0.33, and S0.42 (Figure 4b). The spontaneously gated Ec‐I92G‐I96G adopted a 0.25 nS stable substate (~S0.07), the lowest‐conducting substate observed in the WT Ec‐MscL (Figure 4c). These data demonstrate that the modification at “hot‐spot” not only results in shift of the constriction point but also altered pattern of gating transition.

FIGURE 4.

Gating transitions couple with the movement of constriction point. (a) Representative single channel current of Ec‐WT MscL recorded under negative pressure. The all‐point amplitude histogram in the right panel shows the gating substates. The peak positions shown by numbers represent the amplitude of substates relative to the amplitude of the fully open state. The diagram of the pore constriction of Ec‐MscL composed of G26, V23, G22, and L19 is shown on the left. Filled cycle and bold number show the constriction point in the diagram. C: closed state. S: substate. F: Fully open state. (b) Representative single‐channel current recorded under negative pressure and the all‐point amplitude histogram of Ec‐V17L, Ec‐V21L, Ec‐I92L, and Ec‐I96V. (c) Representative single‐channel current recorded under negative pressure and the all‐point amplitude histogram of Ec‐I92G–I96G. The multiple S0.07 substates are shown. (d) Representative western blotting showing disulfide bridge trapping of cysteine substitution at L19, G20, V23, and G26. (e) Summary analysis of percentage of dimerization in total MscL protein (Mean ± SEM, n = 6 western blotting). 26C (blue circle), 23C (black triangle), 22C (black circle), and 19C (red circle). Diagram shows the distance between cysteines changes upon the movement of constriction point. The distance between 26C, 23C, and 22C were increased upon the shift of constriction point from G26 to L19, whereas the distance between 19C was decreased.

2.6. Conformational changes couple with the cytoplasmic movement of constriction point

As it is generally accepted that integral structural rearrangement must occur to coordinate MscL gating (Betanzos et al., 2002; Perozo, Cortes, et al., 2002), we then tested whether the movement of the constriction point couples with the conformational change at pore constriction region. We used a disulfide trapping assay to assess the proximity of G26/V23/G22/L19 residues in the pentameric structure of Ec‐MscL complex. The reactivity of cysteine of mutants G26C, V23C, G22C, or L19C to its counterpart from neighboring subunits to form a dimer that occurs in vivo was examined (Figure 4d). Copper phenanthroline was used as oxidant to induce the formation of the disulfide bridges. Note that no significant dimer formation could be observed without the treatment of copper phenanthroline (Figure S2). The amount of dimerization is presented as a percentage of the dimers to total MscL protein. Ec‐WT MscL contains no endogenous cysteine and showed only monomers and no dimer formation (Figure 4d), whereas cysteine substituted at G26 (G26C) consistently formed the predominant disulfide‐bridge, resulting in a 95 ± 4.1% dimerization. I92L or I92G–I96G mutants were introduced to generate the shift of the constriction point from G26 in WT to G22 in Ec‐I92L, and further to L19 in Ec‐I92G–I96G. In parallel with the shift, the dimerization decreased slightly to 92 ± 4.2% for G26C–I92L and then dramatically to 60 ± 3.4% for G26C–I92G–I96G. This pattern was observed similarly for cysteine substitutions at V23 and G22. Interestingly, instead of a decrease, a significant increase of dimerization was seen for L19C mutated channel (48 ± 2.5% and 67 ± 3.2% for the constriction point at G26 and L19, respectively). As the amount of disulfide‐bridging is usually inversely proportional to the distances between the cysteine residues of neighboring subunits, the changes of dimerization observed upon the shift of the constriction point could be due to structural movements occurring in the gating process. Along the shift of constriction point from 26 (closed state) to 22 (expanded state induced by I92L) to 19 (leaking state induced by I92G‐I96G), G26, V23, and G22 move away from the axis of the pore in the gating transition, whereas L19 moves close to the pore, then transit into funnel‐shaped conformations.

2.7. Lipids interact with the constricting “hot spots” in the gating process

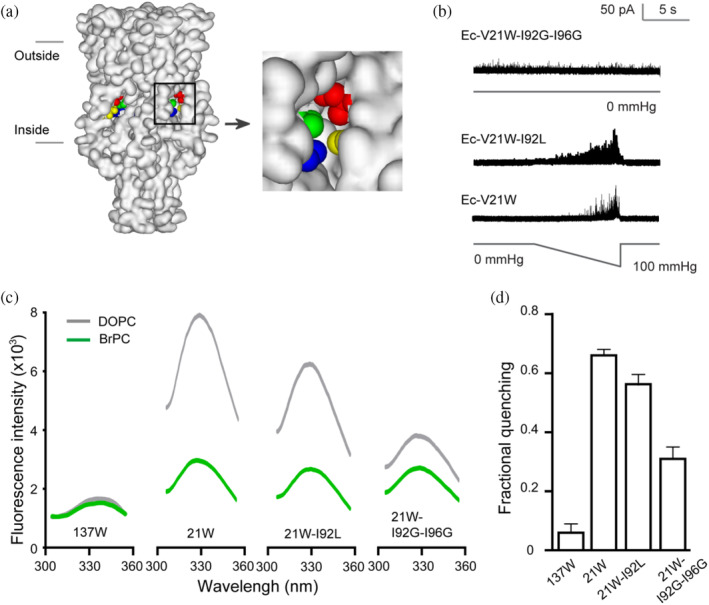

Ion channels are proteins that embedded in the membrane and the surrounded lipids play the important role for their function. For example, the exchange of phospholipid acyl chains between bilayer and TM pockets has been observed to determine the conformation of bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscS (Pliotas et al., 2015). The altered channel gating induced by lipid–protein interactions has been demonstrated in the eukaryotic K2P mechanosensitive channel TRAAK and TREK‐1 (Brohawn et al., 2012, 2014, b). For MscL, the effect of lipids component and lipids headgroup on the channel function, as well as lipids interacting residues have been reported in several studies (Bavi et al., 2016; Iscla et al., 2011a, 2011b; Moe & Blount, 2005; Powl et al., 2008a, 2008b; Wang et al., 2022; Zhong & Blount, 2013). Ec‐MscL constricting “hot spot” V17, V21, I92, and I96 locate at TM1–TM2 interface. There are small cavities around these residues in the structural surface of channel protein (Figure 5a), thus lead to the hypothesis that the transition of lipids into the hydrophobic pocket formed by V17, V21, I92, and I96 may occur upon gating. The absence of endogenous tryptophans in Ec‐MscL makes it an ideal model for the lipid interaction analysis based on tryptophan fluorescence quenching technique. Tryptophan‐mutant of MscL channels were reconstituted into the lipid vesicles with nonbrominated lipids (1,2‐dioleoyl‐sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphocholine, DOPC), or lipids that were brominated in the middle of the fatty acid chains (1,2‐di‐(9,10‐dibromo)stearoyl‐sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphocholine, BrPC). A decrease in the intensity of the tryptophan fluorescence (quenching) caused by the brominated lipids is an indication of its proximity to the hydrocarbon region (Carney et al., 2007; Pliotas et al., 2015). Single tryptophan substitution of V21 (Ec‐V21W) was chosen as the example. In addition, 137 W, in which a tryptophan was inserted at the cytoplasmic C‐terminal end of the Ec‐MscL protein, served as a control.

FIGURE 5.

Interaction of lipids and Ec‐V21W in the gating process. (a) Side view of the protein surface of Ec‐MscL in closed state (Sukharev, Betanzos, et al., 2001, derived from 2OAR). The horizontal lines show the approximate positions of two sides of the membrane. V17 (blue), V21 (green), and the adjacent I92 (red), and I96 (yellow) are shown in space‐fill style in the cavity in the enlargement of the square box. (b) Single channel recordings show the pressure‐dependent MscL activity of Ec‐V21W and EC‐V21W–I92L, and spontaneous activity of Ec‐V21W–I92G–I96G. (c) Representative tryptophan fluorescence emission of MscL mutants reconstituted in brominated lipids (BrPC, green) or nonbrominated PC (DOPC, gray). (d) I92L and I92G–I96G substitutions decrease the BrPC quenching of 21 W fluorescence intensity (Mean ± SEM, n = 5 reconstitutions).

We observed the strong peak fluorescence intensity of Ec‐V21W when reconstituted in DOPC vesicles, but BrPC drastically decreased the fluorescence intensity with a fractional quenching of 0.65 ± 0.02, suggesting that in the closed state of the channel V21W is in proximity to the bromine atom of the lipid (Figure 5b–d). The tryptophan fluorescence of I92L or I92G–I96G mutated Ec‐V21W was further examined to evaluate the lipid interactions in the gating transition state of MscL. Ec‐V21W–I92L showed a lower gating threshold (0.86 ± 0.15, compared to 1.18 ± 0.12 of Ec‐V21W) and decreased fractional quenching of BrPC (0.54 ± 0.04). For the vesicles reconstituted with spontaneously gated Ec‐V21W–I92G–I96G, the fractional quenching of BrPC was only half of that of V21W (0.32 ± 0.05). Note that there was no significant difference in the protein amount of each mutant reconstituted between DOPC and BrPC vesicles (Figure S3). These results demonstrate that the BrPC lipids are proximal to the position 21 in the closed state, however, the decreased fractional quenching observed in Ec‐V21W–I92L and Ec‐V21W–I92G–I96G MscL indicating that BrPC lipids are away from position 21 in expanded transition state and gated state, respectively.

3. DISCUSSION

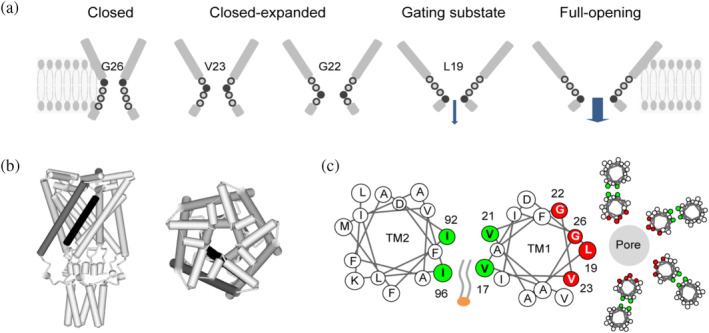

In this study, we identified the constricting “hot‐spots” in the TMs of MscL channel and demonstrated that hydrophilic substitutions of the residues in the “hot‐spots” confer mutant channels with the constriction point showing a movement alone the gating pathway. We further revealed that low‐conducting substates with increased mechanosensitivity and expanded conformation of constriction region are coupled with the movement of constriction point. These findings provide snapshots of the gating process of pore constriction in response to the mechanical force and indicate a gating transition model of Ec‐MscL (Figure 6a).

FIGURE 6.

A model of MscL gating transition. (a) Schematic illustration displays the constriction point shift in the gating process, coupled with the expansion of pore constriction region. Filled cycle and bold number show the constriction point. Arrows indicate the ion permeation. (b) Schematic representations of Ec‐MscL structure in the closed state (Sukharev, Betanzos, et al., 2001, derived from 2OAR). Left: side view of the MscL pentamer. Right: top view from the periplasmic. TM1 (black) of an individual MscL subunit, and TM2 (dark gray) of adjacent subunit are shown. (c) Helical wheel diagrams showing the lipids–protein interaction. The constriction “hot‐spots” (blue) form the hydrophobic pocket at the interfacial region of TM1–TM2. Constriction points (red) line the constriction of the pore. The penetration of lipids into the hydrophobic pocket is shown.

In the model, G26, V23, G22, and L19 of Ec‐MscL are proposed to form the aqueous face of the pore in the constriction region. The model describes that in the closed state of Ec‐MscL channel, G26 acts as the constriction point to restrict ion permeation, while V23, G22, and L19 are buried in the constriction region. Upon gating, constriction region expands and these residues are sequentially exposed to aqueous phase, thus hydrate pore constriction and reduce the energy barrier of gating. Once L19 is exposed to the periplasmic lumen, the channel permeation will be initiated. The model also indicates that constriction points shift cytoplasmically in the path of the closed‐expanded transition, and couples with the expansion of tightly packed hydrophobic constriction region to conduct ion permeation in response to the membrane tension.

G26, V23, G22, and L19 of Ec‐MscL were shown to line one surface of TM1 α helices which locate in the narrow part of the pore in the closed conformation (Chang et al., 1998). Hydrophilic substitutions at this region destabilized channels at closed state and conferred channels gated at lower tension (Yoshimura et al., 1999, 2001). Most of the severe GOF mutations of Ec‐MscL were identified in these residues. SCAM studies have further shown that modification of positive changed MTSET with the cysteine substitutions, such as G26C, V23C, G22C, and L19C resulted in Ec‐MscL channels that gate spontaneously in the absence of membrane tension (Bartlett et al., 2004, 2006). In addition, the corresponding residues of G24, V21, A20, and L19 were determined in our studies to form the constriction region of Sa‐MscL channel. Together, these results support that G26, V23, G22, and L19 form the constriction region acting as hydrophobic barrier to repel water and to block the channel permeation in the closed state.

Previous modeling studies of MscL suggested that the pore‐lining TM1 helix tilts and rotates in response to tension and it undergoes a large in‐plane area expansion during gating (Sukharev, Durell, & Guy, 2001). Accompanied by the expansion, a sequence of transitions from the closed to the fully open state, including putative nonconductive closed‐expanded states and low‐conducting substates occur. The results from thermodynamic analysis further indicated that the major expansion‐sensitive step is the transition from the closed to the low‐conducting substate, as average free energy (ΔE) and in‐plane area (ΔA) of transition from closed to fully open state were estimated to be 52 kT and 20 nm2, and from closed state to low‐conducting substate (S0.13) the estimations were about 45.6 kT ΔE and 14.8 nm2 ΔA (Chiang et al., 2004; Sukharev et al., 1999). The pore constriction separation coupled with pore hydration being the major energetic barrier for opening is supported by the reduced ΔE and ΔA determined for severe GOF mutants V23D and G22N, as these two mutants occupy the S0.13 substate which is suggested to be a pre‐expanded closed conformation. We found in our studies that mutants V17L, V21L, I92L, and I96V frequently visit a multitude of S0.13 low‐conducting substate in response to tension rather high‐conducting or fully opening states, suggesting that with the constriction point shifted from G26 to G22 the pore constriction expands, and the expansion likely lead to altered patterns of subconducting states.

The generation of a leaking MscL channel Ec‐I92G–I96G in our studies provides further insight into the channel transition to the low‐conducting substates. Upon opening, Ec‐I92G–I96G is predominantly locked into the least low‐conducting substate (S0.07), the first sub‐opening state immediately following the closed‐expanded state that is predicted from the modeling analysis. The expansion of pore constriction is experimentally determined by cysteine crosslinking experiments, from which exclusive conformational changes showing L19 moves closer to the central axis of the pore while G26, V23, and G22 of adjacent subunits move away from each other were observed. Given that the L19 is occupied as constriction point in Ec‐I92G–I96G, L19 thus may act as the critical point for the initial opening transition from closed‐expanded conformation to S0.07 substate, and the shift of constriction point from G26 to L19 is likely accordant to closed‐expanded states of MscL. Detailed structural information would be needed for elucidating the rearrangements of TM1 and TM2 that accompany these transitions. Recent studies from MD and NMR (Sharma et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2021) provide some support for the conformational transitions within the constriction region.

Recently, several reports suggested that the crystal structure of Ec‐MscL that were adopted in modeling studies reflects a “nearly closed” state and a slight rotation of TM1 is required to achieve the native closed state (Bartlett et al., 2004; Iscla et al., 2004). V23, which was suggested by crystal structure to be the constriction point of closed pore, may actually shift away from G26 in the expanded transition accompanying the movement of the TMs. On the other hand, resolved crystal structure of Sa‐MscL is generally believed to be in an expanded nonconductive intermediate state (Liu et al., 2009). Sa‐MscL channel constricted at V21 (V23 in Ec‐MscL) shows a pore diameter of 6 Å as compared to 3 Å determined from Ec‐MscL structure. We revealed that the constriction point of Sa‐MscL occupies A20 (G22 in Ec‐MscL) in the closed state, thus implicate that the Ec‐MscL with constriction point occupying G22 may present a closed‐expanded state of the channel. Moreover, the periplasmically shift of Sa‐MscL constriction point is in parallel with increased gating threshold, thereby support the cytoplasmical shift of Ec‐MscL constriction point is in the channel gating process.

The MscL activity is sensitive to the hydrophobicity of the pore (Yoshimura et al., 1999, 2001). Substitution of the residues lining the pore with polar or charged amino acids, especially in the constriction region, conferred channels with reduced gating threshold and GOF phenotype. Of the substitutions, G26S, V23D, and G22E mutations caused the most severe GOF phenotype. In our studies, substituting V17 or V21 of TM1, and I92 or I96 in TM2 with mild hydrophilic amino acids of L, V, A, and G, resulted in channels with increased mechanosensitivity and eventually spontaneously gated channels. More interestingly, we found that hydrophilic modification of the residues in the “hot spot” lead to the shift of constriction points. It is generally accepted that TM1s of Ec‐MscL form the pore, whereas TM2s surrounding the TM1s shield the channel from extensive lipids contacts (Figure 6b). We propose that G26, V23, G22, and L19 face the aqueous phase of the pore lumen and form the constriction, and V17 and V21 on the opposite face of the TM1 helix interact with I96 and I92 in the neighboring TM2 (Figure 6c). The V17, V21 in the TM1 and I92, I96 in the adjacent TM2, construct a hydrophobic pocket at TM1–TM2 interface in the closed state. The environmental fluctuation of hydrophobicity, and subsequent alterations of lipid–protein interaction in the pocket, may be involved to regulate the constriction and the channel activity. Tryptophan fluorescence quenching of Ec‐21W with BrPC demonstrated that lipids may penetrate into the pocket from cavities in the structural surface to interact with these residues. The results from Ec‐21W–I92L and spontaneously gated Ec‐21W–92G–96G suggest that lipid interactions in the pocket area change dynamically in the gating process of MscL channel. The hydrophilic substitutions at “hot spots” may disturb the stability of lipids in the pocket, thus destabilize the interactions between lipids and TMs and interfere with the movement of the TMs in the closed or closed‐expanded transition. This may ultimately lead to the shift of constriction point and decreased energy barrier of the gating, and cause channel to gate at lower tension.

Membrane proteins may meet the problems for determination of oligomeric states due to the presence of surrounded lipid, and especially the detergent molecules that are used for solubilization. In the study, we used detergent DDM for protein solubilization and proteoliposome reconstitution. Although it has been proven to be success in many cases, recently, using a new technique coined oligomer characterization by addition of mass (OCAM), the Ec‐MscL forms hexamers as well as pentamers when solubilized in DDM. To test whether there exists hexamer of Ec‐MscL in the system, we generated Ec‐V23C–I96C MscL that have been previously reported to form multimers (Li et al., 2009). Combined with the treatment of osmotically downshock and the oxidizing agent copper phenantraline, protein bands consistent with MscL multimers ending at the pentamer but not hexamer, were detected by Western blot in cells expressing Ec‐V23C–I96C MscL (Figure S5). These results indicate that there is a high possibility the purified Ec‐MscL in this study are in correct oligomeric states.

Ec‐MscL can be routinely reconstituted into lipid components, it even functions in phosphatidylcholine lipids, which are not synthesized by E. coli. However, MscL locates in the inner membrane of E. coli, which is composed of 80% of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), 10% of phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and about 10% of cardiolipin (CL). The flux assay of the fluorescent molecule calcein indicated that the addition of the anionic lipids such as native lipids PG or CL to the lipids PC resulted in increases in the amplitudes and rates of release of calcein. The 100% DOPC was used for the reconstitution in this study. Although the channel function was retained but it may have some limitations. First, the reconstituted result may not reflex the physiological environment. Second, unexpected effects of lipid PC may happen to the channel function. However, the study does support the protein‐lipid interactions that occur in the constricting “hot spots” pocket upon channel gating.

Sa‐MscL has been cloned into E. coli strains and the MscL channel activity was confirmed in E. coli and liposome (Liu et al., 2009; Moe et al., 1998; Yang et al., 2013; Zhong & Blount, 2014). Sa‐MscL has a sequence identity of 47% and similarity of 69% with Ec‐MscL; however, the Sa‐MscL has much shorter open dwell times and requires greater membrane tension to open. The ability of Sa‐MscL to rescue the viability of E coli from osmotic downshock was detected previously (Liu et al., 2009) and also in this study. Altogether, Sa‐MscL expressed in E. coli may not act exactly the same as that in Staphylococcus aureus, but it remains the major MscL function.

Together, our data reveal a new resolution of the transitions from the closed to the opening substate of MscL, providing insights into the gating mechanisms of MscL.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1. Strains

The wild‐type and mutants of EcMscL and SaMscL were inserted into pB10d plasmid (Blount et al., 1996). The E. coli strain MJF465 (mscL − , mscS − , mscK − ) was used for viability assay, liquid growth, and electrophysiological analysis. The E. coli strain PB104 (mscL − ) was used for gating threshold determinations. Cells were grown at 37°C in Lennox Broth (LB) plus 100 μg/mL ampicillin, and expression of MscL was induced by using isopropy‐d‐thiogalactoside (IPTG). 2‐(Trimethylammonium) ethyl methanethiosulfonate bromide (MTSET) was obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, ON, Canada), and all other reagents were from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO).

4.2. Viability and growth assay

The assay was performed as previously described (Bartlett et al., 2004). The overnight culture was diluted 1:50, grown for l h, and then further diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in LB with 0.5 M NaCl. The culture was induced for 1 h with 1 mM IPTG when it reached an OD600 of 0.2, and the induced cultures were diluted 1:20 into LB containing (a) 0.5 M NaCl (control); (b) 0.5 M NaCl and 1 mM MTSET (MTSET); or (c) pure water (osmotic downshock). All the cultures were grown with shaking at 37°C for 15 min, and then serially diluted (six consecutive 1:10) and plated on LB‐ampicillin agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C and the colony was counted.

4.3. Spheroplast preparation

E. coli giant spheroplasts in patch–clamp experiments were generated as described previously (Blount et al., 1999). The overnight culture was diluted 1:100, grown to an OD600 of 0.2, and then diluted 1:10 in a total of 30 mL of media with 60 mg/mL of cephalexin, an antibiotic that blocks cell separation. The culture was then incubated with shaking for 1.5–2 h, until filamentous cells reached 50–150 μm in length. The expression of MscL was then induced with 1 mM IPTG for 5–60 min, depends on the growth phenotype of different mutants. The filamentous cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 min, and then resuspended gently in 2.5 mL of 0.8 M sucrose. Then, 125 μL of Tris‐Cl (1 M, pH 8), 120 μL lysozyme (5 mg/mL), 30 μL DNase I (5 mg/mL), and 150 μL Na‐EDTA (0.125 M, pH 7.8) were added sequentially to the cultures and for 5 min at room temperature to form spheroplasts. The reaction was stopped using 1 mL of an ice‐cold solution containing 0.7 M sucrose, 20 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Tris‐Cl. After the reaction, the mixture was layered over two culture tubes containing 7 mL of an ice‐cold solution [0.8 M sucrose, 10 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Tris‐Cl (pH 8)]. The mixture was centrifuged at 4°C for 2 min at 1500 rpm, and the spheroplasts were harvested by resuspending the pellets.

4.4. Electrophysiology

MscL single‐channel current in inside‐out patches excised from giant spheroplasts was recorded at −20 mV under the symmetrical conditions in a recording buffer at pH 6.0 (200 mM KCl, 90 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM HEPES). The recording was performed at 10 kHz filtration with an Axopatch 200B amplifier, at a sampling rate of 25 kHz using Digidata 1440A data acquisition system and pCLAMP10 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Negative pressure was applied to the recording electrode using a High Speed Pressure Clamp (HSPC, ALA‐scientific). Timing and intensity of the pressure were controlled by the signals generated from Clampex.

4.5. Western blot and cysteine trapping

Cells were grown in LB medium and induced with 1 mM IPTG for 60 min at 37°C. Harvested cells were subjected to two passes through a French pressure cell (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 16,000 psi to complete lysis. The crude lysate was cleared by centrifugation for 10 min at 6000g, and the total cell membrane fraction was collected by centrifugation at 200,000g for 30 min. This membrane fraction was then incubated with or without copper phenanthroline (final concentration 150 μM) at 37°C for 20 min in the absence of downshock. Samples were immediately spun down, run on SDS‐PAGE gel, and then transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA) for Western blot. Histag anti‐body (A00186, Genscript) was used to determine the MscL protein.

4.6. Protein purification

MscL protein was purified as described previously (Moe & Blount, 2005). Harvested cells were subjected to two passes through a French pressure cell (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 16,000 psi to complete lysis. The lysates were solubilized with detergent n‐dodecyl‐d‐maltoside (1%, w/v, Anatrace) and collected the supernatant by centrifugation for 10 min at 6000g. MscL was then bound through its C‐terminal His6 tag to nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni‐NTA)‐agarose. Eluted protein was concentrated after two buffer exchanges to remove imidazole using an Amicon Ultra with 30,000‐MWCO filters (Millipore Co, Billerica, MA). Protein concentration was determined with the Micro BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

4.7. Proteoliposome reconstitution

Reconstitution was performed as described previously (Häse et al., 1995; Moe & Blount, 2005). 1,2‐Dioleoyl‐sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphocholine (DOPC) and 1,2‐stearoyl‐(6,7)‐dibromo‐sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphocholine (BrPC) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). Lipids were dissolved in chloroform was shell‐dried under argon. The lipid film was resuspended and lipid vesicles were formed by bath sonication to near‐clarity. MscL protein was then added to lipid vesicles at a protein‐to‐lipid mass ratio of 1:100 for reconstitution. Detergent was removed by dialysis against 2X 1000 mL of buffer containing Calbiosorb beads. Add 200 mg (wet weight) biobeads each time and replace every 8 h. Proteoliposomes were diluted in HEPES/EGTA buffer to a protein concentration of 90 μg/mL for tryptophan fluorescence measurement.

For electrophysiology, sedimentation and flotation methods are performed to collect the proteoliposomes. Sedimentation method: the proteoliposomes were collected by a 20‐min centrifugation at 200,000g (Beckman TLA100.2 rotor). Flotation method: 100 μL proteoliposomes were added into Beckman polycarbonate spin tube (1 mL, 11 × 34 mm), then add 100 μL of 60% sucrose in PBS to yield a 30% final sucrose concentration. Mix gently to have a homogenous solution. Overlay 250 μL of 25% sucrose and 50 μL of PBS buffer on top without disturbing the layers. Centrifuge at 174,000g for 1 h at 20°C (Beckman TLA100.2 rotor).

The collected samples were resuspended to 1.3 mg/μL in 10 mM MOPS buffer (pH 7.4) containing 5% ethylene glycol, and then desiccated under vacuum overnight at 4°C. Desiccated proteoliposomes were rehydrated for at least 2 h in buffer (150 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 μM CaCl2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.2) at a lipid concentration of 90 mg/mL, and unilamellar blisters were used for patch‐clamp recording.

Note that in flotation methods, almost all of the samples were floated on the top layer, indicating the high efficiency of protein reconstitution into the liposome. Meanwhile, using Ec‐MscL as an example, the samples from sedimentation and flotation methods were tested separately by patch‐clamp single‐channel recording. None of the differences in channel properties or the success rate of patching could be seen between the two methods (Figure S4). Sedimentation method was used to achieve the results presented in the main text.

4.8. Quenching of tryptophan fluorescence

Measurements were performed in an F‐4500 fluorescence spectrometer (Hitachi Instruments) with excitation at 295 nm and emission from 300 to 400 nm at 20°C. Excitation and emission slits were set to 3 and 5 nm, respectively, and polarizers were set at 90° and 0°, respectively. For each mutant and lipid composition, the peak intensities were measured. Background was corrected with buffer solution containing the lipid vesicles only. Fractional quenching was calculated as (F 0 − F)/F 0, where F 0 is the intensity for the sample containing 100% DOPC lipids, and F is the intensity for the sample containing 100% BrPC lipids.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mingfeng Zhang: Methodology; investigation; formal analysis. Siyang Tang: Methodology; formal analysis; investigation; validation. Xiaomin Wang: Methodology; formal analysis; validation. Sanhua Fang: Formal analysis; methodology. Yuezhou Li: Conceptualization; supervision; writing – original draft; formal analysis; methodology.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Schematic structure of MscL. (a) Mt‐MscL (Protein Data Bank code 2OAR), Left: top view, Middle: side view, Right: half‐cutting side view of the protein with surface. Red box indicates the pore constriction region. (b) Sa‐MscL (Protein Data Bank code 3HZQ), Left: top view, Middle: side view, Right: half‐cutting side view of the protein with surface. Red box indicates the pore constriction region. (c) The pore radius schemes of and along the central axes. The scheme was produced from HOLE program. (d) Schematic representations of Ec‐MscL structure in the closed state and open state (Sukharev, Betanzos, et al., 2001). An individual subunit (black) of each MscL is shown.

Table S1 The expression analysis of cysteine mutants.

Figure S2 Western blotting of cysteine mutants show that no significant dimer formation could be observed without the treatment of copper phenanthroline. Noted that 5x samples are loaded in order to detect the dimer formation.

Figure S3 Western blotting of vesicle sample of MscL mutants reconstituted inbrominated lipids (BrPC) or nonbrominated PC (DOPC). There is no significant difference in the amount of each reconstituted mutant in BrPC or DOPC vesicles.

Figure S4 Patch‐clamp recording of Ec‐WT‐MscL reconstituted into liposome through sedimentation method (a) and floatation method (b). None of the differences could be seen between the two methods.

Figure S5 Western blot showing disulfide bridge trapping of V23C/I96C. Pentamer (5X) formation is seen in cells expressing V23C/I96C that are treated with osmotic downshock in the presence of 150 μM copper phenanthroline [Cu(II)]. The multimer was reduced in the absence of osmotic downshock. WT serves as the control showing the monomer only due to lack of the cysteine.

Table S2 Analysis of MscL mutants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paul Blount at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center for the collaborative work. We are grateful to the core facilities of College of Agriculture and Biotechnology, College of Environmental and Resource Sciences of Zhejiang University for technical support. We thank Sanhua Fang from the core facilities, Zhejiang University School of Medicine for his technical support. The project was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2018YFE0112900) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31871060).

Zhang M, Tang S, Wang X, Fang S, Li Y. Mechanosensitive channel MscL gating transitions coupling with constriction point shift. Protein Science. 2024;33(4):e4965. 10.1002/pro.4965

Mingfeng Zhang, Siyang Tang, Xiaomin Wang, and Sanhua Fang contributed equally to this work.

Review Editor: John Kuriyan

REFERENCES

- Anishkin A, Chiang C, Sukharev S. Gain‐of‐function mutations reveal expanded intermediate states and a sequential action of two gates in MscL. J Gen Physiol. 2005;125:155–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett J, Levin G, Blount P. An in vivo assay identifies changes in residue accessibility on mechanosensitive channel gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10161–10165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett J, Li Y, Blount P. Mechanosensitive channel gating transitions resolved by functional changes upon pore modification. Biophys J. 2006;91:3684–3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batiza A, Kuo M, Yoshimura K, Kung C. Gating the bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscL in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5643–5648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavi N, Cortes D, Cox C, Rohde P, Liu W, Deitmer J, et al. The role of MscL amphipathic N terminus indicates a blueprint for bilayer‐mediated gating of mechanosensitive channels. Nat Commun. 2016;22:11984–11997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betanzos M, Chiang C, Guy H, Sukharev S. A large iris‐like expansion of a mechanosensitive channel protein induced by membrane tension. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:704–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkner J, Poolman B, Kocer A. Hydrophobic gating of mechanosensitive channel of large conductance evidenced by single‐subunit resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12944–12949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount P, Iscla I. Life with bacterial mechanosensitive channels, from discovery to physiology to pharmacological target. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2020;84:e00055‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount P, Sukharev S, Moe P, Martinac B, Kung C. Mechanosensitive channels of bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1999;294:458–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount P, Sukharev S, Moe P, Schroeder M, Guy H, Kung C. Membrane topology and multimeric structure of a mechanosensitive channel protein of Escherichia coli . EMBO J. 1996;15:4798–4805. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohawn S, Campbell E, MacKinnon R. Physical mechanism for gating and mechanosensitivity of the human TRAAK K+ channel. Nature. 2014;516:126–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohawn S, del Marmol J, MacKinnon R. Crystal structure of the human K2P TRAAK, a lipid‐ and mechano‐sensitive K+ ion channel. Science. 2012;335:436–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohawn S, Su Z, MacKinnon R. Mechanosensitivity is mediated directly by the lipid membrane in TRAAK and TREK1 K+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:3614–3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney J, East J, Lee A. Penetration of lipid chains into transmembrane surfaces of membrane proteins: studies with MscL. Biophys J. 2007;92:3556–3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang G, Spencer R, Lee A, Barclay M, Rees D. Structure of the MscL homolog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a gated mechanosensitive ion channel. Science. 1998;282:2220–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C, Anishkin A, Sukharev S. Gating of the large mechanosensitive channel in situ, estimation of the spatial scale of the transition from channel population responses. Biophys J. 2004;86:2846–2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C, Bavi N, Martinac B. Bacterial mechanosensors. Annu Rev Physiol. 2018;80:71–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deplazes E, Louhivuori M, Jayatilaka D, Marrink S, Corry B. Structural investigation of MscL gating using experimental data and coarse grained MD simulations. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorwart M, Wray R, Brautigam C, Jiang Y, Blount P. S. aureus MscL is a pentamer in vivo but of variable stoichiometries in vitro: implications for detergent‐solubilized membrane proteins. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi C, Walton T, Rees D. OCAM: a new tool for studying the oligomeric diversity of MscL channels. Protein Sci. 2011;20:313–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iscla I, Blount P. Sensing and responding to membrane tension, the bacterial MscL Channel as a model system. Biophys J. 2012;103:169–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iscla I, Levin G, Wray R, Reynolds R, Blount P. Defining the physical gate of a mechanosensitive channel, MscL, by engineering metal‐binding sites. Biophys J. 2004;87:3172–3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iscla I, Wray R, Blount P. An in vivo screen reveals protein‐lipid interactions crucial for gating a mechanosensitive channel. FASEB J. 2011a;25:694–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iscla I, Wray R, Blount P. The oligomeric state of the truncated mechanosensitive channel of large conductance shows no variance in vivo. Protein Sci. 2011b;20:1638–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon J, Voth G. Gating of the mechanosensitive channel protein MscL, the interplay of membrane and protein. Biophys J. 2008;94:3497–3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koçer A, Walko M, Meijberg W, Feringa B. A light‐actuated nanovalve derived from a channel protein. Science. 2005;309:755–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte J, Doolittle R. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin G, Blount P. Cysteine scanning of MscL transmembrane domains reveals residues critical for mechanosensitive channel gating. Biophys J. 2004;86:2862–2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Guo J, Ou X, Zhang M, Li Y, Liu Z. Mechanical coupling of the multiple structural elements of the large‐conductance mechanosensitive channel during expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:10726–10731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wray R, Eaton C, Blount P. An open‐pore structure of the mechanosensitive channel MscL derived by determining transmembrane domain interactions upon gating. FASEB J. 2009;23:2197–2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Gandhi CS, Rees DC. Structure of a tetrameric MscL in an expanded intermediate state. Nature. 2009;461:120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinac B, Kung C. The force‐from‐lipid principle and its origin, a ‘what is true for E. coli is true for the elephant’ refrain. J Neurogenet. 2022;36:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe P, Blount P. Assessment of potential stimuli for mechano‐dependent gating of MscL, effects of pressure, tension, and lipid headgroups. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12239–12244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe P, Blount P, Kung C. Functional and structural conservation in the mechanosensitive channel MscL implicates elements crucial for mechanosensation. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe P, Levin G, Blount P. Correlating a protein structure with function of a bacterial mechanosensitive channel. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31121–31127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perozo E, Cortes D, Sompornpisut P, Kloda A, Martinac B. Open channel structure of MscL and the gating mechanism of mechanosensitive channels. Nature. 2002;418:942–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perozo E, Kloda A, Cortes D, Martinac B. Physical principles underlying the transduction of bilayer defor‐mation forces during mechanosensitive channel gating. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2002;9:696–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliotas C, Dahl C, Rasmussen T, Mahendran K, Smith T, Marius P, et al. The role of lipids in mechanosensation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:991–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powl A, East J, Lee A. Anionic phospholipids affect the rate and extent of flux through the mechanosensitive channel of large conductance MscL. Biochemistry. 2008a;47:4317–4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powl A, East J, Lee A. Importance of direct interactions with lipids for the function of the mechanosensitive channel MscL. Biochemistry. 2008b;47:12175–12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z, Kala S, Guo J, Xian Q, Zhu J, Zhu T, et al. Targeted neurostimulation in mouse brains with non‐invasive ultrasound. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada Y, Murase M, Sokabe M. The gating mechanism of the bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscL revealed by molecular dynamics simulations, from tension sensing to channel opening. Channels (Austin). 2012;6:317–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapovalov G, Lester H. Gating transitions in bacterial ion channels measured at 3 micros resolution. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Anishkin A, Sukharev S, Vanegas J. Tight hydrophobic core and flexible helices yield MscL with a high tension gating threshold and a membrane area mechanical strain buffer. Front Chem. 2023;11:1159032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev S, Betanzos M, Chiang C‐S, Guy HR. The gating mechanism of the large mechanosensitive channel MscL. Nature. 2001;409:720–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev S, Blount P, Martinac B, Blattner FR, Kung C. A large‐conductance mechanosensitive channel in E. Coli encoded by mscL alone. Nature. 1994;368:265–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev S, Durell S, Guy H. Structural models of the MscL gating mechanism. Biophys J. 2001;81:917–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukharev S, Sigurdson W, Kung C, Sachs F. Energetic and spatial parameters for gating of the bacterial large conductance mechanosensitive channel, MscL. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:525–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Cao G, Chen X, Yoo J, Yethira A, Cui Q. A finite element framework for studying the mechanical response of macromolecules, application to the gating of the mechanosensitive channel MscL. Biophys J. 2006;91:1248–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Lane B, Kapsalis C, Ault J, Sobott F, Mkami H, et al. Pocket delipidation induced by membrane tension or modification leads to a structurally analogous mechanosensitive channel state. Structure. 2022;30:608–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X, Tang S, Hong F, Wang X, Chen S, Hong L, et al. Non‐apoptotic cell death induced by opening the large conductance mechanosensitive channel MscL in hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. Biomaterials. 2020;250:120061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X, Wang Y, Zhu Z, Guo S, Qian J, Zhu J, et al. Mechanosensitive channel MscL induces non‐apoptotic cell death and its suppression of tumor growth by ultrasound. Front Chem. 2023;11:1130563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Zheng H, Ratnakar J, Adebesin B, Do Q, Kovacs Z, et al. Engineering a pH‐sensitive liposomal MRI agent by modification of a bacterial channel. Small. 2018;14:e1704256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Zhong D, Blount P. Chimeras reveal a single lipid‐interface residue that controls MscL channel kinetics as well as mechanosensitivity. Cell Rep. 2013;3:520–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Tang S, Meng L, Li X, Wen X, Chen S, et al. Ultrasonic control of neural activity through activation of the mechanosensitive channel MscL. Nano Lett. 2018;18:4148–4155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura K, Batiza A, Kung C. Chemically charging the pore constriction opens the mechanosensitive channel MscL. Biophys J. 2001;80:2198–2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura K, Batiza A, Schroeder M, Blount P, Kung C. Hydrophilicity of a single residue within MscL correlates with increased channel mechanosensitivity. Biophys J. 1999;77:1960–1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhang Y, Tang S, Ma S, Shen Y, Chen Y, et al. Hydrophobic gate of mechanosensitive channel of large conductance in lipid bilayers revealed by solid‐state NMR spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2021;125:2477–2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong D, Blount P. Phosphatidylinositol is crucial for the mechanosensitivity of mycobacterium tuberculosis MscL. Biochemistry. 2013;52:5415–5420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong D, Blount P. Electrostatics at the membrane define MscL channel mechanosensitivity and kinetics. FASEB J. 2014;28:5234–5241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Schematic structure of MscL. (a) Mt‐MscL (Protein Data Bank code 2OAR), Left: top view, Middle: side view, Right: half‐cutting side view of the protein with surface. Red box indicates the pore constriction region. (b) Sa‐MscL (Protein Data Bank code 3HZQ), Left: top view, Middle: side view, Right: half‐cutting side view of the protein with surface. Red box indicates the pore constriction region. (c) The pore radius schemes of and along the central axes. The scheme was produced from HOLE program. (d) Schematic representations of Ec‐MscL structure in the closed state and open state (Sukharev, Betanzos, et al., 2001). An individual subunit (black) of each MscL is shown.

Table S1 The expression analysis of cysteine mutants.

Figure S2 Western blotting of cysteine mutants show that no significant dimer formation could be observed without the treatment of copper phenanthroline. Noted that 5x samples are loaded in order to detect the dimer formation.

Figure S3 Western blotting of vesicle sample of MscL mutants reconstituted inbrominated lipids (BrPC) or nonbrominated PC (DOPC). There is no significant difference in the amount of each reconstituted mutant in BrPC or DOPC vesicles.

Figure S4 Patch‐clamp recording of Ec‐WT‐MscL reconstituted into liposome through sedimentation method (a) and floatation method (b). None of the differences could be seen between the two methods.

Figure S5 Western blot showing disulfide bridge trapping of V23C/I96C. Pentamer (5X) formation is seen in cells expressing V23C/I96C that are treated with osmotic downshock in the presence of 150 μM copper phenanthroline [Cu(II)]. The multimer was reduced in the absence of osmotic downshock. WT serves as the control showing the monomer only due to lack of the cysteine.

Table S2 Analysis of MscL mutants.