ABSTRACT

The rational design of HIV-1 immunogens to trigger the development of broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) requires understanding the viral evolutionary pathways influencing this process. An acute HIV-1-infected individual exhibiting >50% plasma neutralization breadth developed neutralizing antibody specificities against the CD4-binding site (CD4bs) and V1V2 regions of Env gp120. Comparison of pseudoviruses derived from early and late autologous env sequences demonstrated the development of >2 log resistance to VRC13 but not to other CD4bs-specific bNAbs. Mapping studies indicated that the V3 and CD4-binding loops of Env gp120 contributed significantly to developing resistance to the autologous neutralizing response and that the CD4-binding loop (CD4BL) specifically was responsible for the developing resistance to VRC13. Tracking viral evolution during the development of this cross-neutralizing CD4bs response identified amino acid substitutions arising at only 4 of 11 known VRC13 contact sites (K282, T283, K421, and V471). However, each of these mutations was external to the V3 and CD4BL regions conferring resistance to VRC13 and was transient in nature. Rather, complete resistance to VRC13 was achieved through the cooperative expression of a cluster of single amino acid changes within and immediately adjacent to the CD4BL, including a T359I substitution, exchange of a potential N-linked glycosylation (PNLG) site to residue S362 from N363, and a P369L substitution. Collectively, our data characterize complex HIV-1 env evolution in an individual developing resistance to a VRC13-like neutralizing antibody response and identify novel VRC13-associated escape mutations that may be important to inducing VRC13-like bNAbs for lineage-based immunogens.

IMPORTANCE

The pursuit of eliciting broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) through vaccination and their use as therapeutics remains a significant focus in the effort to eradicate HIV-1. Key to our understanding of this approach is a more extensive understanding of bNAb contact sites and susceptible escape mutations in HIV-1 envelope (env). We identified a broad neutralizer exhibiting VRC13-like responses, a non-germline restricted class of CD4-binding site antibody distinct from the well-studied VRC01-class. Through longitudinal envelope sequencing and Env-pseudotyped neutralization assays, we characterized a complex escape pathway requiring the cooperative evolution of four amino acid changes to confer complete resistance to VRC13. This suggests that VRC13-class bNAbs may be refractory to rapid escape and attractive for therapeutic applications. Furthermore, the identification of longitudinal viral changes concomitant with the development of neutralization breadth may help identify the viral intermediates needed for the maturation of VRC13-like responses and the design of lineage-based immunogens.

KEYWORDS: HIV, bNAb, VRC13, escape, evolution, CD4bs

INTRODUCTION

Acute HIV-1 infection leads to the production of both non-neutralizing and neutralizing antibodies against the envelope glycoprotein (Env), with early autologous neutralizing responses arising within 3–12 months of infection (1). The highly error-prone process of HIV-1 replication facilitates rapid escape from antibody-mediated immunity, requiring the ongoing development of new antibody responses (1–5). This ongoing intra-host viral evolution may result in the development of heterologous antibody responses, termed broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs), which are capable of neutralizing 50% or more of multiclade heterologous HIV-1 isolates (6). Unfortunately, such highly cross-reactive antibodies develop in only 20%–30% of chronically infected HIV-1 patients, take many years to develop, and are not overtly associated with control of the autologous virus (7). However, due to their ability to provide complete protection against infection by a wide variety of heterologous strains (8–10), as well as suppress viremia and partially delay viral rebound upon removal of antiretroviral therapy (ART) (11–17), there is considerable interest in harnessing their potential for prophylactic and therapeutic purposes.

The mechanisms responsible for the development of such bNAbs are, however, complex, and their induction through vaccination has proven to be extremely challenging (18–20). Although highly conserved, their epitopes are poorly accessible, and thus, it is difficult to engender responses against these targets (21). Additionally, bNAbs generally display a high rate of affinity maturation indicative of extensive adaptation to the constantly evolving autologous Env, likely taking years to develop (22, 23). However, longitudinal studies, albeit thus far limited to only a few subjects (24–35), have suggested that focused viral diversification preceding the emergence of bNAbs might be key to their induction (24, 25, 35). For example, in characterizing the development of the CH103 bNAb, a CDRH3-dominated CD4bs bNAb, Liao et al. identified that interaction of the infecting HIV-1 Env with the unmutated common ancestor B-cell receptor resulted in intense co-evolution of both the virus and lineage members of the developing bNAb (35). The identified mutations associated with CH103 resistance found within loop D, V5, and the CD4-binding loop may, thus, help inform immunogen design targeted to induce and develop a CH103-like response (35–37). Similarly, in individual CAP256 exhibiting a V1V2 bNAb specificity, Bhiman et al. demonstrated that minority viral variants and transient mutations may be critical to priming bNAb precursor B cells leading to bNAb lineage development (25, 34). As such, the design of lineage-based immunogens requires knowledge of co-evolving sequences within the viral env and the developing bNAb lineage that serve to guide the developing antibody response (38–45). To this end, Bricault et al., through the identification of V2-targeted bNAb contact residues and escape mutations, designed HIV-1 Env immunogens capable of inducing cross-neutralizing bNAbs in guinea pigs (43). Similarly, HIV-1 Env immunogens derived from the longitudinal donor CH505 variants were shown to induce CH103-like antibodies in a macaque model, albeit with limited breadth, suggesting that induction of these responses is a reproducible phenomenon (46).

HIV-1-specific bNAbs target five distinct epitopes on Env: (i) the CD4-binding site, (ii) the V1/V2 loops or trimer apex, (iii) the glycan supersite at the base of the V3 loop, (iv) the membrane proximal external region (MPER), and (v) the gp120-gp41 interface (47). The broad and potent CD4bs bNAb VRC01 mimics CD4 in its binding to HIV-1 Env, primarily mediating Env binding through the somatically mutated VH1-2 heavy chain gene (48, 49). Other CD4bs bNAbs like 3BNC117 and NIH45-46, which also bind Env in a similar manner, are derived from the same VH1-2 germline, have a characteristically short CDRL3 (5 aa), and are, thus, grouped within the VRC01-class of bNAbs (22, 23, 50–52). Notably, all CD4bs antibodies that have advanced into clinical testing either as prophylactics or as therapeutics (3BNC117, N6, VRC01, and VRC07-523) belong to this VH1-2 subset of CD4bs bNAbs (53). However, while these VRC01-class antibodies show high potency and breadth in in vitro assays, antibody immunotherapy even with bNAbs can, nonetheless, lead to the emergence of viral escape variants and viral rebound in both animal models and clinical studies (11, 12, 15, 54). These findings have raised concerns regarding the therapeutic use of single bNAbs and pushed forth the concept of utilizing bNAbs in combination, much akin to the requirements for antiretroviral therapies to avoid the development of drug resistance.

A second group of non-VRC01 class CD4bs bNAbs are derived from the VH1-46 germline and notably bind Env gp120 at a unique angle of approach compared to the VRC01 class (52, 55). While a majority of these VH1-46 derived CD4bs bNAbs are less broad and potent than the VRC01-class, the newly discovered 1–18 antibody shows high breadth and potency and, importantly, exhibits different escape pathways than the VRC01-class antibodies (56). Finally, a third subset of CD4bs bNAbs are not VH-gene restricted but instead mediate Env binding via the antibody CDRH3 region. This group includes VRC13, VRC16, CH103, b12, and HJ16, all of which originate from distinct germline VH genes (55, 57). In particular, VRC13 shows comparable breadth (>80%) and greater potency than multiple VRC01-class bNAbs, suggesting a valuable role for this antibody in HIV-1 prevention (55, 58). Additionally, its distinct mode of antibody contact via the CDRH3, and unique mode of approach at latitudinal and longitudinal angles very similar to CD4, may influence or even restrict the development of viral escape variants in patterns distinct from those seen with VRC01-class bNAbs.

Antigen contact sites for VRC13 have been identified based on the crystal structure of HIV-1 Env bound to VRC13 (55). Similarly, the effect of some engineered HIV-1 Env modifications (e.g., changes in overall trimer glycosylation) or computationally predicted sites of escape on VRC13 neutralization have been tested (59–64). While some residues such as N386 and S395 exhibiting resistance to VRC13 neutralization were identified, these engineered mutations do not necessarily represent in vivo viral evolution. To this end, Zhou et al. conducted a comparative sequence analysis of resistant and sensitive HIV-1 strains from single time points within multiple individuals to identify Envs that are resistant to CD4bs bNAb neutralization (65). This study identified Env changes that altered recognition by multiple CD4bs bNAbs, including changes largely within loop D that led to VRC13 resistance. More importantly, this study identified mutations that affected VRC01 neutralization but had no impact on VRC13 binding, supporting the observation that the mode of Env binding is distinct for VRC01 and VRC13 (65). While these data indicate a limited number of contact residues that impact VRC13 neutralization, here, we describe env evolution in response to a VRC13-like immune response during natural infection within an individual previously identified to develop >50% neutralization breadth (66, 67). Specifically, we identify longitudinal env clones that develop resistance uniquely to VRC13, including a cluster of mutations in and around the CD4-binding loop that may provide insight into immunogen design toward the induction of VRC13 bNAb responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants

Plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples were obtained from the Acute HIV Cohort at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. PBMC and plasma samples from HIV-1 Clade B-infected individual AC53 (cohort alias 653116) were collected longitudinally up to 6.9 years post infection (ypi) prior to the start of ART. All samples used in this study were derived from time points at which the patient was not on ART and was not diagnosed with AIDS.

Viral RNA isolation and quantification

Viral RNA (vRNA) was isolated from 1 mL of plasma as previously described (68). Plasma was thawed at room temperature and centrifuged at 21,952 × g for 1.5 h at 4°C, after which the pellet was re-suspended in 140 µL of the supernatant. vRNA was isolated using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) per manufacturer’s protocol with the exception of an additional on-column DNase treatment. Specifically, after the column was washed with Buffer AW1, 10 µL of DNase (Qiagen) diluted in 70 µL of RDD Buffer (Qiagen) was added to the column and was incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The column was then washed again with Buffer AW1 prior to continuing with the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was eluted in 50 µL Elution buffer. Viral loads from the RNA isolation were determined using an HIV-1 gag qRT-PCR with primers based on the Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor test (SK145 5′-AGT GGG GGG ACA TCA AGC AGC CAT GCA AAT-3′ and SK431 5′-TGC TAT GTC ACT TCC CCT TGG TTC TCT-3′) (Roche). Quantifast SYBR Green RT-PCR (Qiagen) reagents were used per manufacturer’s instructions in a 10 µL total volume reaction and analyzed on a Lightcycler 480 (Roche).

RT and PCR amplification

cDNA was synthesized using SSIII Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Purified vRNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA in a final volume of 20 µL including 5 µL vRNA, 1 µL of a deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mixture (each at 2.5 mM), 0.5 µL antisense primer Env3Out (5′-TTGCTACTTGTGATTGCTCCATGT-3′) at 10 µM, 4 µL 5× first-strand buffer, 1 µL dithiothreitol at 100 mM, 1 µL RNaseOUT (Invitrogen), and 1 µL SuperScriptIII reverse transcriptase. The reaction mixture was incubated at 50°C for 60 min, followed by 55°C for an additional 60 min. Finally, the reaction was heat inactivated at 70°C for 15 min and then treated with 1 µL RNase H at 37°C for 20 min. cDNA was used to amplify the full-length envelope gene (env) by platinum-Taq Hi-Fi (Invitrogen) via nested PCR, using primers previously described (69). The thermocycler conditions were 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 4 min, with a final extension of 68°C for 10 min. The product of the first-round PCR was used as a template in the second-round PCR under the same conditions for 45 cycles. Successful envelope amplifications were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis, and products were purified using either QiaQuick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) or Pure Link gel extraction kit (Invitrogen), using the manufacturer’s instructions.

Single-genome amplification and subcloning

Single-genome amplification (SGA) was achieved using limiting dilutions in a nested PCR as previously described (69). Briefly, cDNA was serially diluted and amplified to identify the dilution yielding a PCR success rate of <30%, at which most of the amplicons are generated from a single copy template. The amplification reaction was performed with 1× High-Fidelity Platinum PCR buffer, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 0.2 µM each primer, and 0.5 units/μL High Fidelity Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) in a 20 µL reaction. Envelope amplicons were purified using either QiaQuick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) or Pure Link gel extraction kit (Invitrogen). These SGAs were reamplified by platinum-Taq Hi-Fi (Invitrogen) using gene-specific primers and sequenced. After verifying that these SGA sequences recapitulated diversity seen in bulk env sequencing, amplification products were gel purified and cloned into the pEMC* expression vector using In-Fusion HD cloning (Takara). In-Fusion products were transformed into Stellar Competent Cells (ClonTech) and grown overnight on agar plates with ampicillin. Selected colonies were inoculated for DNA extraction by QIAPrep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen), and successful cloning was verified by Sanger sequencing (MGH CCIB DNA Core). Plasmid DNA from Sanger-verified preps was purified using the HiSpeed Plasmid Maxi Kit (Qiagen) or PowerPrep Plasmid Purification kit (Origene) and sequenced by Illumina.

Illumina library construction and env sequencing

The following protocol was used to sequence bulk env amplifications, SGAs, and re-amplified SGAs cloned into the expression vector pEMC*: samples were prepared for Illumina MiSeq using the Nextera XT Library Prep kit (Illumina). 1–1.25 ng of purified plasmid was tagmented and indexed as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Indexed products were cleaned to remove small fragments via successive 70% and 60% SPRI using AMPure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter). The final product was quantified using a Promega Quanti-Flor fluorometer. Additionally, the sample size was evaluated using the DNA high-sensitivity assay on the Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer. Individual samples were pooled in an equimolar fashion and heat denatured and then diluted to a 12.5 pM final concentration library. The pooled library was spiked with 1% PhiX control (Illumina). The library was sequenced using the MiSeq v2 500-cycle kit (Illumina).

Illumina data analysis

The adapter sequences were trimmed, and the library was demultiplexed on the MiSeq instrument (Illumina). Paired end reads were assembled into a contig using VICUNA de novo assembler and annotated with VFAT v1.0 (68, 70). The envelope consensus sequences were then aligned to an HIV-1 Clade B reference using Mosaik 2.1.73, and variants were called using V-Phaser 2.0 (71). V-profiler was used to generate haplotype information across regions of interest and heatmap data for bulk sequencing visualization (1, 3). Sequences are deposited with SRA (accession number PRJNA630482) and GenBank (accession numbers MT023027–MT023033, MT457783–MT457814) and denoted as individual 653116 or AC53.

Visualization of HIV-1 env diversity

Circular maps of the env gene and bulk diversity data were generated using Circos 0.69 (72).

Generation of env chimeras and point mutants

Env chimeras were generated by amplification of specific regions in env with Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs) using gene-specific primers (IDT) and subcloning using In-Fusion HD cloning (Takara). For the generation of env chimeras “AC53 Frag1”–“AC53 Frag 10,” single-residue substitutions “AC53 K347G,” “AC53 T359I,” “AC53 S362N,” “AC53 N363S,” and “AC53 P369L,” and SGA01-derived constructs combining linked mutations VGINSL, GINSL, GINS, NSL, INS, and VGI, DNA fragments were generated by GenScript (www.genscript.com). These fragments were subcloned into pEMC* expression vector expressing Early Env and amplified (Q5 High-Fidelity Polymerase, New England Biolabs) using In-Fusion HD cloning (Takara) to serve as a suitable vector for the insertion of these fragments. The SGA01-derived constructs combining linked mutations NS and VG were generated through site-directed mutagenesis of the NSL and VGI-linked mutation plasmid constructs, respectively. Successful cloning was verified, and DNA was prepared as described above.

Cells, plasmids, and antibodies

HEK293T/17 cells (ATCC) and TZM-bl cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with the addition of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% l-Glutamine and 25 mM HEPES at 37°C, and 5% CO2 content. TZM-bl cells were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: TZM-bl cells (Cat# 8129) from Dr. John C. Kappes, and Dr. Xiaoyun Wu (73–77). The HIV gp160 expression vector pEMC* was a generous gift from Dr. Nancy L. Haigwood (Oregon National Primate Research Centre). The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: HIV-1 SG3 ΔEnv Non-infectious Molecular Clone from Drs. John C. Kappes and Xiaoyun Wu (2, 77), Anti-HIV-1 gp120 Monoclonal (VRC01) from Dr. John Mascola (Cat# 12033) (48), Anti-HIV-1 gp120 Monoclonal (NIH45-46 G54W) from Dr. Pamela Bjorkman (Cat# 12174) (50), Anti-HIV-1 gp120 Monoclonal (3BNC117) from Dr. Michel C. Nussenzweig (22, 78), Anti-HIV-1 gp120 Monoclonal (HJ16) from Dr. Antonio Lanzavecchia (79, 80), and Anti-HIV-1 gp120 Monoclonal (IgG1 b12) from Dr. Dennis Burton and Carlos Barbas (81–83).

HIV-1 YU2 CD4-binding site gp120 mutant and VRC13

HIV-1 YU2 (WT), HIV-1 YU2 (CD4-binding site gp120 mutant, CD4MUT) (D368R + A281R + G366R + P369R) and human IgG1 HC + LC sequences for VRC13 were constructed as synthetic DNA molecules and cloned into the mammalian expression plasmid pVRC8400 (84, 85). 293F cells grown in Freestyle media (Life Technologies) were transfected with the plasmid transfected with 500 µg/L of each construct (293fectin Reagent, Life Technologies, Cat# 12347019). At day 5 [for YU2, YU2 (D368R + A281R + G366R + P369R)] or day 6 (for VRC13), the cultures were centrifuged (2,000 × g, 10 min), and the supernatant was then filtered (VacuCap 0.2 µm filters, Fisher Scientific, Cat# 501979599). Two separate procedures for affinity purification of YU2 gp120s and VRC13 then follow. YU2, YU2 (D368R + A281R + G366R + P369R) were affinity purified on a 17B column (85). Here, the supernatant was loaded onto Protein A-agarose resin covalently coupled 17B, a CD4i antibody (see below for generation of the 17B column). The resin was washed with 6 column volumes of PBS, and the bound gp120s were eluted with 1.5 column volumes of low pH IgG elution buffer (Pierce, Cat# 21004), directly into 50 mM Tris, pH 8. The gp120 proteins were then concentrated (Amicon Ultra concentrators, 30 kDa MWCO, Millipore, Cat# UFC8030) and then were further separated by size exclusion FPLC using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (Cytiva, Cat# 289990944). To generate the 17B affinity column, 17B HC and LC plasmids (provided by James Robinson, Tulane University) were expressed in 293F cells, harvested (day 6), and affinity purified on Protein G-Agarose (Thermo Scientific, Cat# 20398) using the low pH elution and FPLC steps described above. Ten milligrams of the recombinant 17B was mixed with 5 mL of Protein A-agarose resin (Thermo Scientific, Cat# 20365) within antibody-binding buffer (50 mM sodium borate, pH 8.2, Sigma, Cat# 08059). Following 1 h room temperature incubation, the column was washed in antibody-binding buffer and the 17B was then immobilized by adding 6.5 mg disuccinimidyl suberate (Pierce Cat# 21555) per 1 mL of Protein A. After incubating for an hour at room temperature, the column was then washed with PBS (5 column columns), and non-reacted NHS-ester groups were blocked by adding 0.1 M ethanolamine (Sigma, Cat# E9508) pH 8.2 in diethyl pyrocarbonate (Sigma, Cat# D5758) (1 mL per mL of column volume). The resin was then washed (5 column volumes of low pH IgG elution buffer), and the 17B column was stored in PBS + 0.02% sodium azide (Sigma, Cat# S2002). The recombinant VRC13, harvested on day 6, was affinity purified using Protein A/G-agarose (Thermo Scientific, Cat# 20398) and further separated by size exclusion chromatography [Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (Cytiva, Cat# 289990944)] as described for 17B above. During FPLC, the antibody was buffer exchanged into PBS and then concentrated (Amicon Ultra concentrators, 30 kDa MWCO, Millipore, Cat# UFC8030).

Gp120 ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates (Costar) were coated with 2 mg/mL WT gp120 or CD4MUT gp120 and incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed twice with PBS plus 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature with shaking. Samples were washed five times with PBS-T before adding heat-inactivated plasma or fixed concentrations of VRC13 monoclonal antibody. Plates were incubated for 3 h at room temperature with shaking. Samples were washed six times with PBS-T and labeled with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Bethyl Laboratories Inc.) recognizing human IgG. Plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with shaking and then washed six times with PBS-T. Tetramethylbenzidine solution (Fisher) was added and left for 10 min at room temperature with shaking. The reaction was stopped with 2 M sulfuric acid (H2SO4). Plates were immediately read for absorbance at 450 nm with a Tecan plate reader.

Plasma depletion assays

Adsorption of CD4bs antibodies from AC53 plasma at 6.2 ypi was performed as previously described (67, 86). Recombinant YU2 WT and CD4MUT gp120 proteins were coupled to MyOne Dynabeads Tosylactivated (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Fifty milligrams of magnetic beads was bound with 1 mg protein ligand overnight at 37°C with gentle rotation. Protein-coupled magnetic beads were blocked overnight, washed, and stored as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Bead-coupled Env proteins were tested for antigenic integrity by flow cytometry using the CD4bs-targeted monoclonal antibody (mAb) VRC01 and the V2-targeted mAb PG9, followed by detection with PE-conjugated anti-human IgG antibody (Southern Biotech) before depleting plasma antibodies.

Beads were incubated with DMEM containing 10% FBS for 30 min. Two hundred and fifty microliters of heat-inactivated AC53 plasma (6.2 ypi) was diluted 1:10 in DMEM + 10% FBS and incubated with 500 µL Env-coupled beads at room temperature for 60 min with gentle rotation. The samples were then placed on a magnet, and the supernatant was collected as “depleted plasma.” Three rounds of bead adsorptions were performed per sample. Depleted plasma was centrifuged at 16,100 g for 5 min, and supernatant was transferred to a separate tube to remove any residual magnetic beads for a total of three spins. This depleted plasma was used for neutralization assays. Plasma samples treated in the same fashion with BSA-coupled beads were used as background controls.

Pseudovirus expression

Pseudotyped HIV-1 was produced by calcium phosphate transfection (Takara Bio Inc.) of HEK293T cells (T75 flask) with 3.75 µg of pEMC* expressing the specific envelope glycoprotein and 11.25 µg of an HIV expression vector lacking a functional env gene (pSG3∆Env). Transfected cells were incubated at 37°C/5% CO2. The medium was changed 12 h post-transfection and collected 48 h later. Supernatants were passed through a 0.45-µm syringe filter and stored at −80°C. For the AC53 S362N single-residue substitution pseudovirus, multiple T75 flasks were transfected as described above, and supernatants were collected 48 h post transfection, passed through a 0.45-µm syringe filter, and further concentrated with the addition of PEG-it (System Biosciences) to precipitate viral particles.

TZM-bl luciferase assay

Pseudovirus titers were determined as described (87). Briefly, pseudovirus dilutions were incubated with TZM-bl cells for 48 h at 37°C. Cells were lysed with Britelite Plus (Perkin Elmer), and luciferase was measured using a TopCount Nxt plate reader (Perkin Elmer). Pseudovirus dilutions that yielded 100,000 relative luciferase units (RLU) readings were used for neutralization assays. TZM-bl neutralization assays were performed as previously described (88). Briefly, HIV-1 pseudoviruses were preincubated with titrated amounts of antibody or heat-inactivated plasma (56°C for 45 min) in DMEM with 10% FBS for 1 h at 37°C. TZM-bl cells were detached by trypsinization, diluted in DMEM with 10% FBS, and added to the pseudovirus-inhibitor mixture at 10,000 cells/well. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. After 48 h, cells were lysed with Britelite Plus (Perkin Elmer), and luciferase was measured using a TopCount Nxt plate reader (Perkin Elmer). Percent infectivity (% infectivity) was calculated as RLU (Virus + EntryInhibitor)/RLU (VirusOnly) * 100. Fifty percent of inhibitory concentrations or dilutions (IC50s or ID50s, respectively) were determined with GraphPad Prism 8.0 software using sigmoidal four-parameter logistic curve analysis. The data in this manuscript are plotted as the mean value of the three replicates, and the error bars depict the calculated standard error of the mean.

Molecular modeling

Side-chain mutagenesis and subsequent rotamer analyses were performed using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC, with PDB 4YDJ and 3NGB as models (49, 55).

RESULTS

Development of plasma neutralization breadth in donor AC53

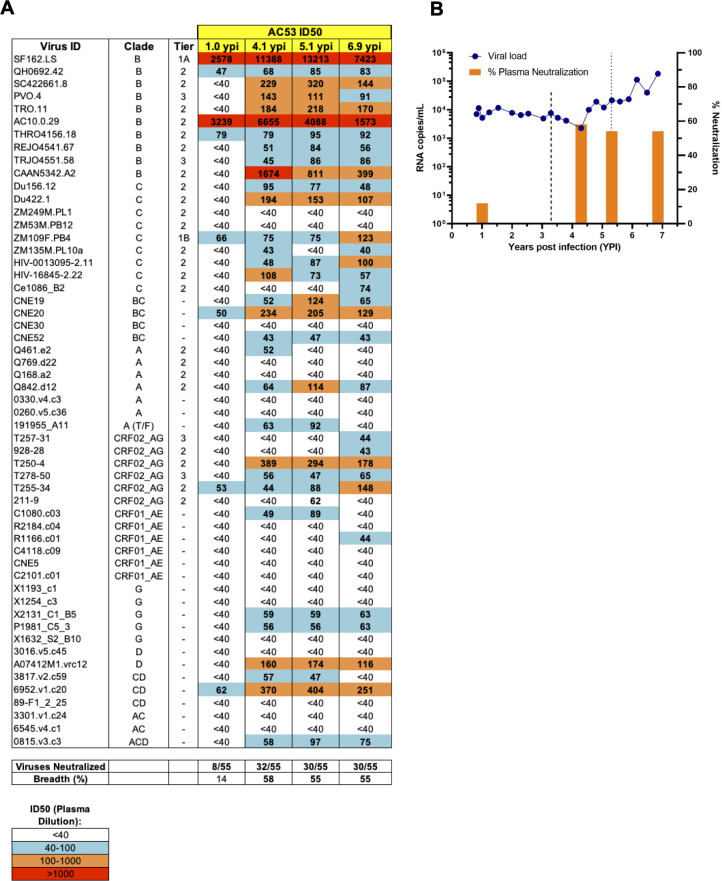

Mikell et al. previously identified a broad neutralizer AC53 who developed >50% neutralization breadth against a 20 pseudovirus panel (66, 67). We expanded this analysis to a 55-pseudovirus panel representing multiple HIV-1 clades and tiers with plasma from 1.0, 4.1, 5.1, and 6.9 years post infection (ypi). While plasma at 1.0 ypi showed weak cross-neutralization activity, we observed a significant increase in breadth at 4.1 ypi, neutralizing 58% (32/55) of the viruses tested concomitant with an increase in the general potency (plasma at higher dilutions inhibiting pseudovirus infection by 50%) (Fig. 1A). Subsequently, the breadth of cross-neutralization activity was largely maintained at 5.1 ypi (55%) and 6.9 ypi (55%) although a decrease in overall potency was observed at 6.9 ypi (Fig. 1A). Clinically, viral loads remained generally stable around 10,000 RNA copies/mL over the first 4 years of untreated infection, after which there was a progressive increase in viremia to above 100,000 RNA copies/mL along with declining CD4 + T cell counts (data not shown) necessitating ART treatment after 6.9 ypi (Fig. 1B). Mikell et al. identified the emergence of dual epitope cross-neutralizing specificities in individual AC53 over the course of infection, first against the CD4bs at 3.5 ypi and subsequently against the V1V2 region (N160-dependent) at 5.3 ypi (Fig. 1B) (66, 67). These results corroborate the previously observed development of neutralization breadth seen in donor AC53 and indicate that plasma at 5.1 ypi demonstrated peak potency and >50% breadth against a larger standardized virus panel.

Fig 1.

Development of neutralization breadth in donor AC53 over 6.9 years post HIV-1 infection. (A) ID50 values of AC53 plasma from 1.0, 4.1, 5.1, and 6.9 ypi tested against a standardized 55-pseudovirus panel. ID50 values indicate plasma dilutions that reduced maximal viral infection by 50% and are color-coded according to the legend shown at the bottom. (B) Plasma viremia is shown as HIV-1 RNA copies/mL (left y-axis, blue line), and plasma neutralization breadth is shown as % of viruses neutralized (right y-axis, orange bars) during untreated infection. The dashed lines at 3.5 and 5.3 ypi indicate cross-neutralizing CD4bs and N160-directed V1V2 specificities in AC53 plasma, respectively, as per Mikell et al. (67).

Viral evolution in HIV-1 env CD4 contact sites and the V1/V2 loop

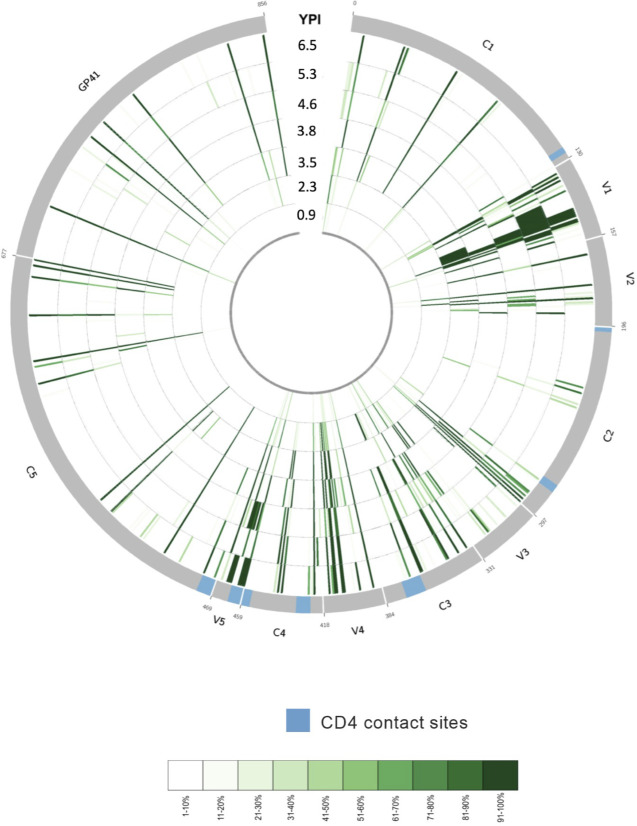

To identify viral sequence changes associated with the development of these dual epitope cross-neutralizing specificities, HIV-1 env was bulk amplified from 8 time points spanning 0.9–6.5 ypi and sequenced by next-generation sequencing. As visualized using a Circos ideogram (72), sequence diversity at baseline (0.9 ypi) was very limited as expected (Fig. 2). However, expanding diversity was observed to develop across Env over the course of infection, in particular relatively early within the V3/C3/V4 regions corresponding to the previously denoted CD4bs specificity and known CD4-contact sites (89), as well as within the V1/V2 regions corresponding to the later developing N160-directed specificity (Fig. 2). In particular, we were interested in early Env variants arising within the first 4 years post infection that would be critical to both the initiation of, and escape from, the cross-neutralizing CD4bs response that first developed (66, 67). Overall, the focused evolution within the V3/C3/V4 regions containing CD4-contact sites further supports the presence of a CD4bs-specific response.

Fig 2.

Env evolution in donor AC53 over 6.9 years post HIV-1 infection. Circos ideogram indicating Env amino acid sequence evolution from 0.9 ypi (innermost circle) to 6.5 ypi (outermost circle). Env sequences were derived using bulk PCR amplification from patient plasma and sequenced by next-generation sequencing. Green tick marks denote the presence of amino acid substitutions differing from the baseline (0.9 ypi) consensus amino acid residue at any given position and time point. A light green tick mark denotes the presence of a low-frequency amino acid variant, and a dark green tick mark denotes the presence of a high-frequency amino acid variant as depicted in the color-coded legend. The 0.9 ypi time point depicts numerous amino acid sites in the early viral population exhibiting low diversity, while later time points radiating outward illustrate increased sequence divergence from baseline as well as numerous residues evolving to fixed amino acid variants. Known CD4-contact sites are indicated in blue on the outer gray circle.

Development of resistance to a VRC13-like neutralizing antibody response

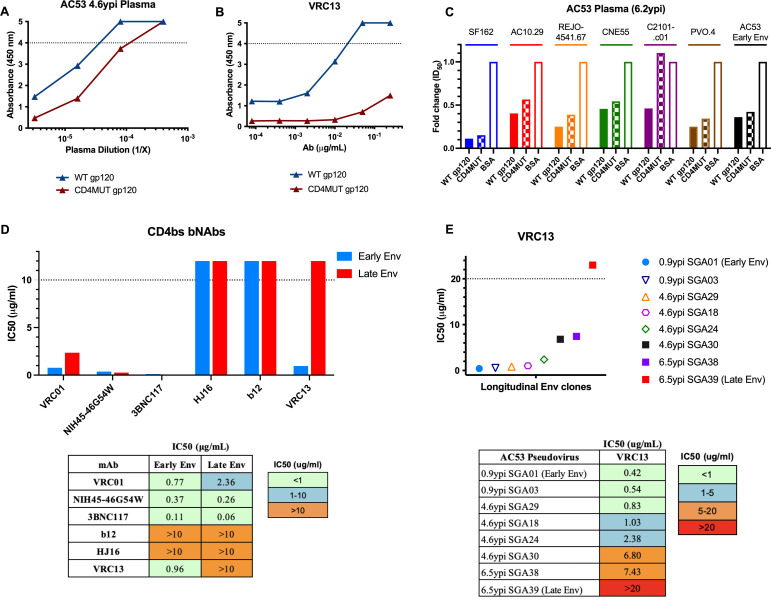

To confirm the presence of CD4bs-specific antibodies from donor AC53, we compared the levels of plasma-binding antibodies to wild-type YU2 gp120 (WT gp120) or a YU2 CD4bs mutant (CD4MUT gp120) containing four substitutions (A281R, G366R, D368R, and P369R) previously demonstrated to abrogate binding of CD4bs antibodies (55, 85). Plasma at higher concentrations bound both WT gp120 and CD4MUT gp120, presumably due to the presence of plasma antibodies targeting non-CD4bs gp120 epitopes. However, at lower plasma concentrations, we observed a >5-fold decrease in CD4MUT gp120 binding compared to WT gp120 (Fig. 3A). As a control, we verified that a known CD4bs bNAb, in this case VRC13, efficiently bound WT gp120 but exhibited dramatically reduced binding to CD4MUT gp120 (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that plasma antibodies targeting the CD4bs contributed to HIV-1 gp120 recognition in donor AC53. To further verify that donor AC53 plasma exhibits CD4bs specificity, we utilized magnetic bead-bound WT gp120 and CD4MUT gp120 to selectively deplete either all gp120-binding antibodies or all non-CD4bs gp120-binding antibodies, respectively. The neutralization activity of these depleted fractions was then tested against a panel of heterologous viral isolates. As expected, depletion of all gp120-binding antibodies from 6.2 ypi plasma with WT gp120 dramatically decreased the neutralization potency of plasma against all viral isolates tested versus BSA-depleted plasma controls. In contrast, however, depletion of plasma using the CD4MUT gp120 retained higher neutralization against these six heterologous viral isolates suggesting that a CD4bs specificity is a key component of the neutralizing potential of AC53 plasma (Fig. 3C). These data corroborate the previously published contribution of cross-neutralizing CD4bs antibodies in AC53 plasma (67). However, the ability of the CD4MUT gp120 (which does not bind CD4bs antibodies) to at least partially deplete neutralizing activity also suggests the presence of multiple epitope specificities contributing to the cross-neutralizing activity seen in donor AC53 (67).

Fig 3.

Env clones from donor AC53 exhibit resistance to a VRC13-like antibody response. The presence of CD4bs-directed antibodies determined by ELISA using (A) plasma from donor AC53 or (B) bNAb VRC13. AC53 plasma and VRC13 were tested for the presence of binding antibodies against an HIV-1 YU2 gp120 (WT gp120) or a CD4bs mutant containing four mutations (A281R, G366R, D368R, and P369R; termed CD4MUT gp120). (C) Heterologous neutralization of AC53 plasma (6.2 ypi) depleted with either WT gp120 or CD4MUT gp120 plotted as fold change in ID50 values, compared to depletion with BSA (control). IC50 values determined by TZM-bl neutralization assays of (D) a panel of CD4-binding site bNAbs against pseudoviruses expressing AC53 Early Env (SGA01 0.9 ypi) and AC53 Late Env (SGA39 6.5 ypi), with accompanying numerical values, and (E) VRC13 against pseudoviruses expressing various longitudinal AC53 SGAs over 6.5 years post infection, with accompanying numerical values. All experiments were conducted in triplicate. The dotted line in (A) and (B) indicates the maximum detectable absorbance value. The dotted line in (D) and (E) indicates the maximum tested antibody concentration of 10 µg/mL and 20 µg/mL, respectively. Values above these maximums are arbitrarily graphically represented and are not quantifiable.

To better understand the specificity of this CD4bs response, we generated a set of 39 SGA Env clones spanning 6 time points up to 6.5 ypi. Clones SGA01 (0.9 ypi) and SGA39 (6.5 ypi) were selected as representative “Early Env” and “Late Env” pseudoviruses to test for neutralization sensitivity against a panel of known CD4bs bNAbs. Both Early Env and Late Env pseudoviruses were sensitive to neutralization by the VRC01 class bNAbs VRC01, NIH45-46G54W, and 3BNC117, indicating lack of both prior exposure and viral adaptation to a VRC01-like response. In contrast, the non-VRC01 class bNAbs b12 and HJ16 both failed to neutralize either Early Env or Late Env pseudoviruses, suggesting that the viral variant establishing infection in donor AC53 was likely pre-adapted to these antibody specificities. Uniquely, however, the non-VRC01 class, CDRH3-dominated bNAb VRC13 efficiently neutralized the Early Env pseudovirus, while the Late Env pseudovirus demonstrated clear resistance to VRC13 (Fig. 3D). This specific >10-fold increase in IC50 values suggests the presence of a VRC13-like immune response in donor AC53, distinct from other VRC01-like responses, with viral evolution selecting for env escape variants over the course of infection. Extending this analysis to a more diverse array of longitudinal donor AC53 env SGA clones demonstrated a progressive increase in VRC13 resistance, suggestive of persistent env evolution to a VRC13-like antibody response (Fig. 3E). Notably, different env clones derived from the same time point, such as clones SGA24 and SGA30 (4.6 ypi), and SGA38 and SGA39 (6.5 ypi), showed differential VRC13 neutralization susceptibility. These data suggest the presence of genetic imprints of viral adaptation in response to this VRC13-like response which could facilitate the subsequent mapping and identification of prospective VRC13 escape mutations.

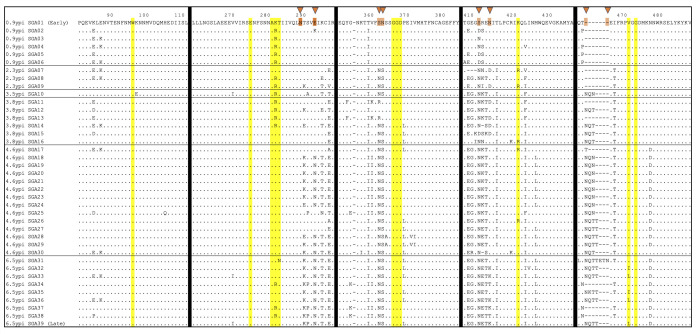

Longitudinal evolution of donor AC53 env in and around known VRC13 contact sites

To identify naturally occurring viral adaptations associated with the development of resistance to the described VRC13-like response, we compared longitudinal full-length env SGA clones from donor AC53 aligned to the VRC13-sensitive Early Env (SGA01). Utilizing discrete 15 amino acids windows flanking known VRC13 contact sites, we observed amino acid substitutions at 4 of 11 known VRC13 contact sites: K282, T283, K421, and V471 (Fig. 4). Specifically, a K282R variant was dominated at 0.9 ypi before replacement with K282 at 4.6 ypi though partial re-emergence of K282R was observed at 6.5 ypi. A rare T283N variant was also detected at 6.5 ypi. Variant K421R also transiently emerged between 2.3 and 4.6 ypi. Finally, variants V471I and V471L were first detected at 6.5 ypi though these changes did not reach fixation. However, the evolutionary changes at each of these contact sites either reflected minority variants or were transient, failing to emerge as fixed substitutions. More importantly, only variant V471L differed between the VRC13-sensitive Early Env (SGA01) and VRC13-resistant Late Env (SGA39).

Fig 4.

Longitudinal Env evolution in donor AC53 flanking known VRC13 contact sites. Amino acid sequence alignment of Env clones isolated by SGA from donor AC53. Amino acid numbering corresponds to the HIV-1 HXB2 reference strain. Each row reflects a single Env SGA clone, denoted by date post infection isolated and SGA clone number. Time points are separated by horizontal black lines. Residues highlighted in yellow indicate 11 known VRC13 contact sites. Vertical black lines denote alignment breaks between windows containing known VRC13 contact sites. Orange triangles at the top denote PNLG sites where sequence evolution was observed. Identical amino acids are shown as dots and deletions are shown as dashes. “0.9 ypi SGA01” and “6.5 ypi SGA39” denote the “Early Env” and “Late Env” pseudoviruses used in neutralization assays.

However, we did observe more predominant and fixed changes at other sites adjacent to these known contact residues. These included, among others, numerous PNLG changes at positions 289, 293, 362, 363, 412, 413, 460, and 463. The addition of glycans or slight shifts in their positions on Env can significantly impair Ab recognition and, therefore, likely reflect viral adaptations to evade neutralization. Notably, 8 of 12 PNLG sites within these windows evolved over the 6.5 years of follow-up, supportive of concerted efforts of the virus to evade immune pressures. Some additional sequence adaptations were transient in nature (i.e., E87K and I466T), potentially guiding the development of a VRC13-like response. However, more than 15 mutations became fixed over time and could represent escape from the VRC13-like antibody response. Temporally, the close proximity of shifts in PNLG sites at S362, N363, along with a P369L substitution within the CD4-binding loop, all immediately adjacent to known VRC13 contact sites, represented attractive stepwise adaptations that could be associated with the development of and/or escape from the broad CD4bs-targeted immune response (Fig. 4).

The V3 and CD4-binding loops mediate escape from bNAb VRC13

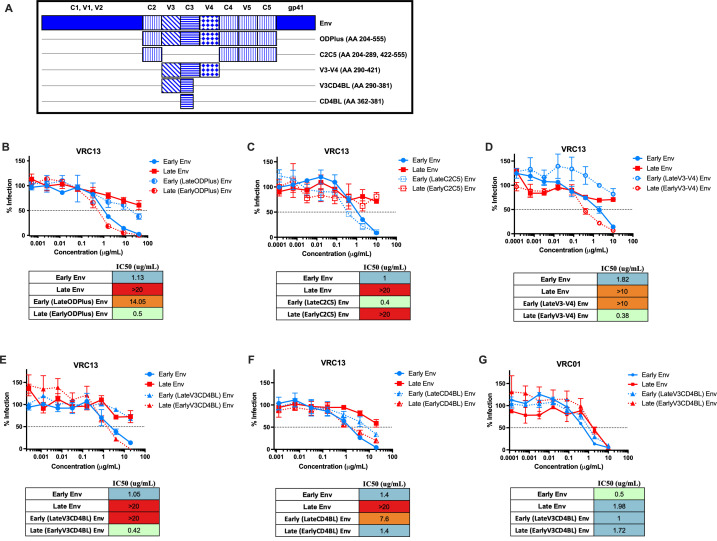

To elucidate the regions conferring escape from a VRC13-like response, we generated a series of donor AC53 env chimeras by swapping out distinct domains within C2–C5 between full-length Early Env and Late Env SGA clones (Fig. 5A). First, we examined neutralization against a chimera containing the entire C2–C5 region (termed ODPlus for Outer Domain Plus) with the VRC13 monoclonal antibody, demonstrating that the Late ODPlus region recapitulated the resistance to VRC13 seen with viruses expressing the full-length Late env sequence (Fig. 5B). In contrast, viruses expressing the Early ODPlus region in a Late Env backbone increased sensitivity to VRC13 neutralization (Fig. 5B). This indicated that the Late ODPlus region was both necessary and sufficient to confer resistance to VRC13, thus narrowing the focus of potential VRC13 escape mutations to the Late ODPlus region. We next tested the outer C2, C4, V5, and C5 regions (C2C5) which did not affect neutralization by VRC13, indicating that these Env regions did not contain potent VRC13 escape mutations (Fig. 5C). However, the remaining V3, C3, and V4 regions (V3–V4) alone completely altered the neutralization phenotype of the background Env, with Late V3–V4 chimeras demonstrating strong resistance to VRC13 and Early V3-V4 increasing recognition by VRC13 (Fig. 5D). Further narrowing these chimeric swaps down to a 90 amino acid region containing V3 and the CD4-binding loop (V3CD4BL) was also sufficient for escape from VRC13 neutralization (Fig. 5E); however, swapping just the CD4BL yielded only partial resistance to VRC13 (Fig. 5F). These data indicate that both the V3 and CD4-binding loop of Late Env contain residues responsible for the development of resistance to VRC13. Additionally, this phenotype was specific to VRC13, with no observed difference in neutralization by VRC01 (Fig. 5G).

Fig 5.

Mutations within the V3 and CD4-binding loops are responsible for escape from VRC13. Env chimeras generated between donor AC53 Early Env and Late Env SGA clones are indicated in the schematic in (A). TZM-bl neutralization assays of Env chimeras testing the (B) ODPlus, (C) C2C5, (D) V3–V4, (E) V3CD4BL, and (F) CD4BL regions against VRC13 are shown. (G) TZM-bl neutralization assays of the V3CD4BL chimeras against VRC01 are shown. The dotted line on the y-axis indicates 50% infection. All assays were conducted in triplicate. Data are shown as mean values; error bars represent SEM.

We further tested the effect of these Env chimeras on autologous neutralization (Fig. S1A). While Late ODPlus was sufficient to confer resistance to late autologous plasma (6.5 ypi) (Fig. S1B), both the C2C5 and V3–V4 chimeras resulted in ID50 values halfway between Early Env and Late Env (Fig. S1C and D). These results indicate that the ODPlus region is responsible for a significant part of autologous neutralization escape (Fig. S1B). However, not surprisingly, the autologous neutralization response also targets residues outside the V3–V4 portion of the ODPlus region (Fig. S1C and S1D) unlike the phenotype observed with VRC13 (Fig. 5).

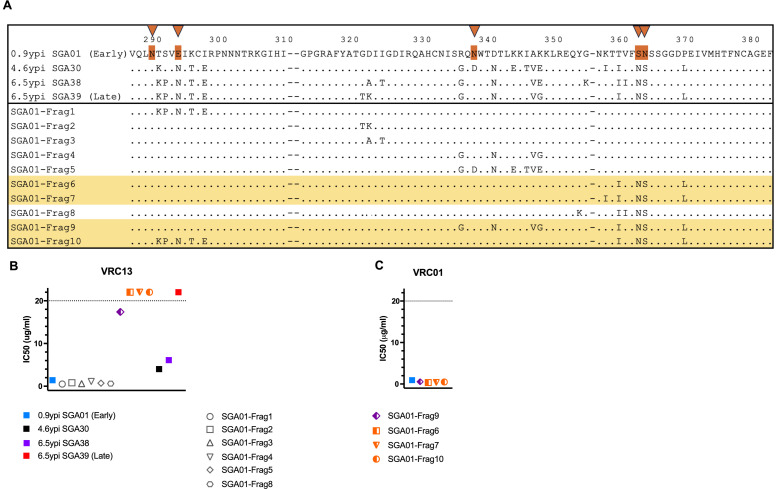

Identification of Late Env changes responsible for VRC13 escape

To more precisely identify the substitutions potentially responsible for the development of resistance to VRC13, we compared sequences across the V3CD4BL region between SGA01 (Early Env, 0.9 ypi) and three chronic AC53 Env clones that showed increased resistance to VRC13 neutralization, SGA30 (4.6 ypi), SGA38 (6.5 ypi), and SGA39 (Late Env, 6.5 ypi) (Fig. 6A). Ten distinct combinations of changes within this region were identified and incorporated into the SGA01 Env (Early Env) backbone to generate unique chimeric Envs, referred to as “SGA01-Frag1” … “SGA01-Frag10.” Testing for neutralization by VRC13 revealed that 4 of the 10 chimeras, Frag6, Frag7, Frag9, and Frag10, exhibited increased resistance to VRC13 (Fig. 6B). In contrast, these four chimeric Envs with reduced sensitivity to VRC13 inhibition were not found to alter neutralization sensitivity of VRC01, confirming specific adaptation to a VRC13-like response (Fig. 6C). These data confirmed that amino acid changes within the V3CD4BL region were necessary and sufficient to mediate escape from VRC13.

Fig 6.

AC53-specific mutations and their contribution to VRC13 neutralization in donor AC53. Env variants generated based on amino acid substitutions between donor AC53 Early Env SGA01 and Late Env SGA39 are indicated in the schematic in (A), with selected substitutions incorporated into the Early Env SGA01 backbone. Orange triangles at top denote PNLG sites where sequence evolution was observed. Graphical representation of IC50 values of chimeras indicated in (A) determined by TZM-bl neutralization assays with (B) VRC13 and (C) VRC01 are shown. Env chimeras that demonstrated resistance to VRC13 neutralization are highlighted yellow in (A). The dotted line in (B) and (C) indicates the maximum tested Ab concentration of 20 µg/mL. Values above these maximums are arbitrarily graphically represented and are not quantifiable. (B–C) Recombinant Envs are color coded to denote no resistance (gray), partial resistance (purple), or complete resistance (orange) to VRC13. Amino acid numbering corresponds to the HIV-1 HXB2 reference strain.

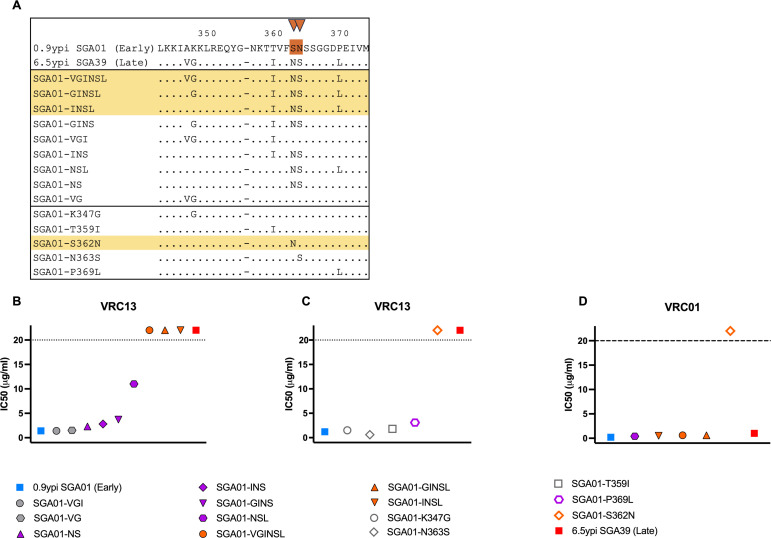

VRC13 resistance is mediated by a cluster of amino acid changes

To pinpoint the substitutions contributing to escape from a VRC13-like antibody response, we generated an additional set of 14 env chimeras (Fig. 7A), each representing different combinations of mutations implicated in resistance to VRC13 (Fig. 6B). Testing these Env chimeras for neutralization by VRC13 revealed that variants “VGI” and “VG” exhibited IC50 values of 1.4 µg/mL and 1.5 µg/mL, respectively, and thus similar sensitivity to neutralization by VCR13 as Early Env (IC50 1.4 µg/mL) (Fig. 7B). In contrast, variants “NS,” “INS,” and “GINS” exhibited slightly increased resistance to VRC13 neutralization, with IC50 values of 2.3 µg/mL, 2.8 µg/mL, and 3.7 µg/mL, respectively. These very modest increases in IC50 values suggest potential minor contributions of the K347G, T359I, S362N, and N363S substitutions to VRC13 resistance (Fig. 7B). The “NSL” chimera demonstrated more pronounced resistance, identifying substitution P369L as a key resistance adaptation. However, the most dramatic impact was observed for each of the “VGINSL,” “GINSL,” and “INSL” chimeras which demonstrated a complete lack of sensitivity to VRC13 neutralization (IC50 > 20 µg/mL), comparable to the phenotype observed with the Late Env SGA39 (6.5 ypi). These findings suggested that one or more of the “INSL” substitutions, which included T359I, S362N, N363S, and P369L, were critical to resistance to VRC13 and likely contributing to evasion from the VRC13-like Ab response.

Fig 7.

Novel VRC13 escape mutations and their contribution to autologous neutralization in donor AC53. (A) Alignment of env chimeras expressing combinations of mutations implicated in resistance to VRC13 incorporated into the Early Env SGA01 backbone. (A). Graphical representation of IC50 values of chimeras indicated in (A) as determined by TZM-bl neutralization assays with (B, C) VRC13 and (D) VRC01. Env chimeras that demonstrated complete escape from VRC13 neutralization are highlighted yellow in (A). The dotted line in (B–D) indicates the maximum tested Ab concentration of 20 µg/mL. Values above these maximums are arbitrarily graphically represented and are not quantifiable. (B–D) Recombinant Envs are color coded to denote no resistance (gray), partial resistance (purple), or complete resistance (orange) to VRC13. Amino acid numbering corresponds to the HIV-1 HXB2 reference strain.

To confirm these findings, individual amino acid variants were expressed in the Early Env SGA01 (0.9 ypi) backbone and tested for neutralization against VRC13. Here, variants K347G, N363S, and T359I individually showed similar neutralization phenotypes as Early Env (IC50 1.2 µg/mL), with IC50 values of 1.5 µg/mL, 0.6 µg/mL, and 1.8 µg/mL, respectively. In contrast, the single residue substitution P369L, which constitutes a part of the CD4-binding loop, exhibited ~3-fold decrease in sensitivity to VRC13 neutralization (IC50 3.1 µg/mL). However, the most potent effect was seen by the S362N substitution, resulting in the addition of a PNLG site, which led to complete loss of recognition by VRC13 (IC50 >20 µg/mL) (Fig. 7C). While it was somewhat surprising that the S362N exhibited such a pronounced decrease in neutralization compared to the “NS” mutant, this S362N substitution when tested alone creates a double “NN” PNLG variant (S362N-N363) not observed naturally in donor AC53. As such, this complete loss of recognition observed by the S362N “NN” substitution likely over represents the contribution of S362N to escape from VRC13. Rather, the “NS” (S362N-N363S) variant which arises simultaneously in donor AC53 could result in a flipping of the glycan, if present, from residue 363 in the Early Env (S362-N363) to residue 362 in the Late Env (S362N-N363S). Nonetheless, the dramatic impact of this artificial double PNLG variant on VRC13 indicates that these glycan sites are critical determinants of VRC13 escape. Therefore, with the exception of P369L, no other single amino acid substitution dramatically affected VRC13 resistance. Additionally, with the exception of the artificial S362N “NN” change tested, the recombinant Envs that conferred resistance to VRC13 again failed to show a change in neutralization by VRC01, confirming a VRC13-specific evolutionary pattern (Fig. 7D). Taken as a whole, these data support that the “INSL” cluster of amino acid variations, namely, T359I, S362N, N363S, and P369L present in SGA01-INSL (Fig. 7B), work in combination to effectively evade a VRC13-like response.

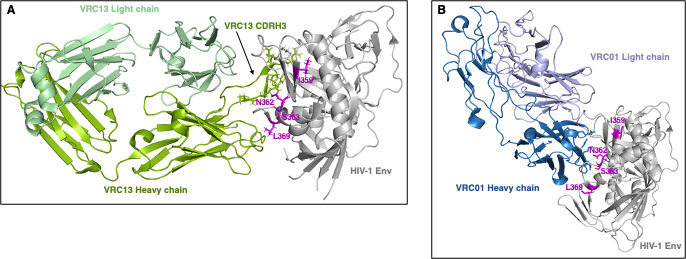

Structural modeling of potential novel VRC13 escape mutations

A structural representation of the four putative VRC13 escape substitutions T359I, S362N, N363S, and P369L was then modeled on HIV-1 Env structures bound to either the CDRH3-dominated antibody VRC13 (Fig. 8A) or the CDRH2-dominated VRC01 (Fig. 8B) (49, 55). The heavy and light chains of these antibodies are indicated, as well as the VRC13 CDRH3 loop which is critical for the interaction of VRC13 with Env. In relation to VRC13, the P369L substitution suggests potential interaction with the VRC13 heavy chain (Fig. 8A). The S362N and N363S substitutions, in turn, lie in close proximity to the CDRH3 loop of VRC13, with the side chain of S362N notably protruding out toward the CDRH3 loop. As such, migration of the PNLG site from N363 to S362 could be expected to place a glycan at this critical interface and obstruct binding by VRC13. Finally, while mutation T359I lies more distal from the antibody-Env interface, protrusion of its side chain internally toward the central alpha helix could potentially affect protein structure, in particular on the closely neighboring S362 and N363 residues harboring the PNLG substitution. Figure 8B depicts Env in a spatial orientation bound to the VH1-2 antibody VRC01 (49). As described previously, the unique angle of approach of VRC13 binding is quite distinct from VRC01, with substitutions P369L and T359I unlikely to interfere with VRC01 binding. Notably, however, the location and side chain orientation of the S362 and N363 residues does support the ability of the double PNLG variant “NN” (S362N-N363) to exhibit resistance to VRC01 as observed in Fig. 7D.

Fig 8.

Structural modeling of potential novel VRC13 escape mutations. The four potential VRC13 escape changes T359I, S362N, N363S, and P369L were modeled on previously published HIV-1 Env structures bound to either (A) VRC13 (PDB ID 4YDJ) or (B) VRC01 (PDB ID 3NGB). HIV-1 Env is denoted in gray, and (A) VRC13 heavy chain and light chains are shown in dark green and pale green, respectively. (B) VRC01 heavy chain and light chains are shown in dark blue and pale violet, respectively. Residue changes are highlighted in magenta and labeled. All images were created using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC, using PDB 4YDJ and 3NGB as template (49, 55).

DISCUSSION

Broadly neutralizing antibodies can effectively prevent viral infection and could function as successful prophylactics based on their ability to cross-neutralize HIV-1 isolates across multiple clades and tiers. The CD4bs bNAbs VRC01 and 3BNC117, among others, are currently in clinical trials to assess their efficacy in viral control (90, 91). VRC13, another CD4bs antibody, exhibits >80% neutralization breadth and higher potency than the widely tested VRC01 and, therefore, could also be a viable candidate for HIV-1 prevention (55, 58). While the effectiveness of antibody therapy via passive transfer is critically dependent on plasma levels and half-life of the administered antibody, the use of HIV-1 Env immunogens to induce these targeted responses may provide more durable protection (11, 54). However, the induction and evolution of functional bNAb responses have proven especially difficult, partly due to the inadequate data regarding critical Env adaptations required for the effective triggering and maturation of these responses (18–20). In particular, the limited information on longitudinal viral changes in response to a VRC13-like immune pressure precludes the design of immunogens to induce VRC13-like bNAbs in vivo.

Individual AC53 was previously observed to develop multiple epitope specificities at a time when neutralization breadth was identified to be >50% (66, 67). The first, a CD4bs specificity, was identified at 3.5 ypi and demonstrated cross-neutralizing activity. In line with these data, we observe the development of >50% neutralization breadth 3–4 years after infection (66, 67). The second specificity, identified at the time of peak neutralization breadth around 5.3 ypi, showed N160-dependent PG9-like properties (66, 67). It remains to be determined whether this second specificity is also cross-neutralizing in nature. Studies depleting plasma antibodies targeting the N160 glycan, as done here for the CD4MUT, may elucidate the contribution of each antibody specificity to neutralization breadth observed in AC53 plasma. We also note changes in neutralization potency from 4.1 to 6.5 ypi. Intriguingly, a decrease in potency for neutralization of some viruses (AC10.29, CAAN5342.A2) from 4.1 to 5.1 ypi, and for a majority of the viruses within the tested panel from 5.1 to 6.5 ypi, was observed (Fig. 1). A similar decrease in plasma potency while maintaining high neutralization breadth has previously been observed in longitudinal studies that led to the isolation of the V1/V2-targeted VRC26 lineage, as well as the MPER antibodies RV217-VRC42.01, -VRC43.01, and -VRC46.01 (32, 92). These data may indicate contemporary escape from the predominant plasma antibody response that specifically neutralized these viruses, or may be indicative of the emergence of multiple antibody specificities, possibly lowering the plasma concentration of the antibody response that efficiently neutralizes these viruses. This loss of neutralization potency notably occurs coincident with an upswing in viremia in AC53 from 4.3 to 6.5 ypi.

Here, we demonstrated the development of VRC13 resistance utilizing a panel of CD4bs bNAbs to identify the classification of CD4bs-targeted immune pressure. While the V1/V2 loops can also modulate binding of CD4bs-targeted antibodies (24, 93), the observed development of resistance to VRC13 by Late ODPlus and Late V3-V4 (both of which do not include the Late V1/V2 regions) suggests that the AC53 V1/V2 loops are unlikely to contain highly potent VRC13 escape mutations (Fig. 5). Nonetheless, we did observe minority variants and transient changes at known VRC13 contact sites K282, T283, K421, and V471 that may influence B-cell receptor affinity maturation and help modulate recognition of the developing VRC13-like antibody lineage (25). Rather, we demonstrate that the CD4-binding loop in the autologous Late Env contains potent escape mutations unique to VRC13, which importantly do not mediate escape from VRC01. Testing of combinations of amino acid substitutions naturally occurring in individual AC53 indicated that mutations T359I, S362N, N363S, and P369L (“INSL”) together exemplified the minimal epitope required for complete VRC13 escape. Here, it is important to note that our V3 chimera in the mapping studies encompassed flanking residues, including T359I, which likely contributed to the increased resistance of the “LateV3CD4bs” (Fig. 5E) versus the “LateCD4bs” (Fig. 5F) to VRC13. Consistent with these findings, the Late Env (SGA39 6.5 ypi) contained all four amino acid changes implicated in VRC13 resistance, while SGA38 (6.5 ypi), which exhibited only partial resistance, lacked the P369L substitution. However, partial resistance to VRC13 was also observed by SGA30 (4.6 ypi) which did contain the full array of “INSL” substitutions, suggesting a potential impact of other upstream mutations unique to SGA30 which might alter the effects of the “INSL” escape pathway (Fig. 6).

When tested individually, the S362N mutation was the only one of the four “INSL” mutations capable of conferring complete resistance to VRC13 on its own (Fig. 7). However, as noted, the S362N point mutant that generates an additional PNLG adjacent to the naturally occurring PNLG at position 363 is not naturally found in isolation in donor AC53. Rather, the PNLG shifts upstream by one amino acid through the concomitant mutation of residue S362N coupled with N363S. Interestingly, the presence of two potential glycosylation sites at residues 362 and 363 have only been observed in only 2 out of 7,590 naturally occurring HIV-1 sequences (0.03%) (94). Thus, while this substitution may favor antibody escape, the presence of the double glycan may be detrimental to viral fitness with Env unable to sustain a double glycan at this location. In contrast, the “NS” (S362N-N363S) double mutant exhibited only minimal impact alone (Fig. 7), suggesting that no individual substitution within the “INSL” array is contributing overtly to escape, but rather it is the full array of “INSL” substitutions that is required to evade VRC13. The heavy glycosylation of HIV-1 Env has previously been described as a viral evasion mechanism against neutralizing antibodies (95, 96). Specifically, the N-glycan at residue 363 has been shown to form an oligomannose glycan shield with the N392 and N386 glycans, both of which are conserved in AC53 Env (97). Of note, it is interesting that while VRC13 predominantly interacts with D368, the P369L substitution adjacent to this critical epitope did not substantially affect VRC13 neutralization when tested in isolation on Early Env (SGA01) (Fig. 7), or previously when mutated in isolation (55). Furthermore, SGA01-NSL, which contained both changes that demonstrated some level of resistance in isolation (SGA01-NS and SGA01-P369L), was insufficient to confer complete resistance to VRC13, as was the SGA01-T359I mutation in isolation. Rather, complete resistance required all four mutations to generate the “INSL” cluster, demonstrating the complex nature of this novel escape pathway.

The four single amino acid changes from this “INSL” cluster implicated in VRC13 resistance appear to emerge as linked mutations within and immediately adjacent to the CD4-binding loop. There is a stepwise process observed, with first the T359I predominating at 0.9 ypi, although whether this represents an early adaptation or was already present in the transmitted/founder virus is unknown due to a lack of earlier samples. This is followed by the simultaneous emergence of the S362N and N363S substitutions, and subsequently the P369L substitution which does not go to fixation at the last time point tested (6.5 ypi) (Fig. 4). This lack of fixation appears due to the presence of a secondary haplotype across this region expressing among other substitutions K282R, S291P, G354K, and V360I, which may be indicative of a P369L-independent pathway to escape the VRC13-like response or developing resistance to another competing nAb specificity.

It is interesting to note that the first known VRC13 contact sites were identified using a deglycosylated HIV-1 Env trimer-VRC13 complex (55). Further studies by Env mutagenesis conducted by Zhou et al. were performed by expressing Env trimers on the surface of HEK293T cells (65). It has previously been shown that trimeric Env expressed on HEK293T cells are glycosylated in a manner comparable to those expressed on primary human cells. Specifically, HEK293T cells, like T cells, exhibit an extensive heterogeneity of complex glycans, albeit with varying ratios of high mannose to complex glycans for both cell types. Importantly, the Env trimers produced in the study by Zhou et al., as well as our study, have been expressed in HEK293T cells and are, thus, likely glycosylated (98). For further studies, these Env trimers could also be produced in 293T cells that have been engineered to produce a larger proportion of N-mannose glycans, to specifically study the role of these N-glycans as VRC13 contact sites (99).

The induction of bNAbs through immunization consists of two critical steps: (i) targeting the bNAb germline precursors to activate B-cells expressing them and (ii) driving affinity maturation against bNAb epitopes. Lineage-based immunogen design borrows available information from the natural course of infection in individuals that develop these bNAb responses. Here, the premise is that the autologous founder virus can bind and prime germline bNAb precursors, while the evolving viral Envs could serve as boosts to guide the temporal development of antibody breadth. As previously noted, rational HIV-1 Env immunogen design has largely been focused on the induction and maturation of VRC01-class CD4bs bNAbs (19, 41, 42, 44, 100, 101). The emergence of VRC01 escape mutations suggests that antibody monotherapy may be inadequate to facilitate complete prevention, and combination therapy may be necessary for therapeutic (passive transfer) or prophylactic (vaccination by immunogen) modalities (11, 15, 17). For this purpose, characterizing CD4bs bNAbs susceptible to discrete escape pathways may be highly beneficial. For example, resistance mutations for VRC01-class bNAbs do not confer resistance to the broad VH1-46 antibodies 1–18 and CH235 as well as the CDRH3-dominated VRC13, indicating that successful escape pathways for different groups of CD4bs bNAbs may be distinct (56, 65, 102). Additionally, the design of lineage-based immunogens is critically dependent on the identification of viral evolutionary patterns that affect the development and escape from the relevant antibody response. The longitudinal data provided in this manuscript allows us to identify the autologous early virus, which is sensitive to VRC13 neutralization. We have further identified longitudinal viral variants that show an increasing resistance to VRC13 neutralization (Fig. 3E). These initial variants, which ultimately contributed to the four amino acid combination needed for full VRC13 resistance, could serve to drive affinity maturation of the B-cells expressing germline precursor BCRs which were initially activated by the transmitted viral variant.

The frequency of precursor B-cells expressing the VRC13-germline is yet unknown. However, both the heavy- and light-chain germlines (VH1-69 and the VL Lambda 2–14, respectively) are highly represented in the human repertoire (103–105). Importantly, the induction of VRC01-like antibodies is critically dependent on the generally low frequency (4%) of VH1-2-expressing B-cells, which in combination with a light chain with a 5-amino acid CDR3 results in an overall VRC01-class precursor frequency of 1 in 2.4 million naïve B cells (41). In contrast, CDRH3-dominated antibodies like VRC13, HJ16, b12, CH103, and VRC16 can mature from distinct V genes and may not be restricted by such low precursor frequencies of naïve B-cells. Given the high potency and breadth of VRC13, a CD4bs bNAb response that is not germline-restricted (like the VRC01-class), the novel VRC13-associated escape mutations defined here may be important to inducing VRC13-like bNAbs for lineage-based immunogens. The unique mode of VRC13 contact (via the CDRH3 versus the VH1-2 CDRH2) may influence or even restrict the development of viral escape variants in patterns distinct from those seen with the VH1-2 restricted VRC01-class bNAbs. Along those lines, a VRC13-based vaccine approach may work cooperatively with a VRC01-based vaccine approach to restrict viral escape through distinct pathways.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We also acknowledge support from the Ragon Institute of Mass General, MIT and Harvard (T.M.A.). We would like to acknowledge the participants in the MGH Acute HIV Cohort and the HIV Negative Cohort as well as Sue Bazner and Graham McGrath for providing us with plasma and PBMC samples. We would like to thank Dr. Nancy Haigwood for providing us with the pEMC* vector for Env expression.

This study was supported by funding through the Ragon Institute of Mass General, MIT and Harvard and the MGH Scholars program (TMA), and NIH grant P01 AI04715 (TMA).

This data represents part of the doctoral dissertation published by Vinita R. Joshi (2020).

Contributor Information

Todd M. Allen, Email: tallen2@mgh.harvard.edu.

Frank Kirchhoff, Ulm University Medical Center, Ulm, Germany.

ETHICS APPROVAL

All subjects gave written informed consent and the study was approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All materials described in this manuscript are available via a material transfer agreement with the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard. All data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01720-23.

Escape from VRC13 leads to partial escape from the autologous neutralizing response.

Legend for Fig. S1.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Moore JP, Cao Y, Ho DD, Koup RA. 1994. Development of the anti-gp120 antibody response during seroconversion to human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 68:5142–5155. doi: 10.1128/JVI.68.8.5142-5155.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Komarova NL, Nowak MA, Hahn BH, Kwong PD, Shaw GM. 2003. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature 422:307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cuevas JM, Geller R, Garijo R, López-Aldeguer J, Sanjuán R. 2015. Extremely high mutation rate of HIV-1 in vivo. PLoS Biol 13:e1002251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Richman DD, Wrin T, Little SJ, Petropoulos CJ. 2003. Rapid evolution of the neutralizing antibody response to HIV type 1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:4144–4149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630530100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li B, Decker JM, Johnson RW, Bibollet-Ruche F, Wei X, Mulenga J, Allen S, Hunter E, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Blackwell JL, Derdeyn CA. 2006. Evidence for potent autologous neutralizing antibody titers and compact envelopes in early infection with subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 80:5211–5218. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00201-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gray ES, Moore PL, Choge IA, Decker JM, Bibollet-Ruche F, Li H, Leseka N, Treurnicht F, Mlisana K, Shaw GM, Karim SSA, Williamson C, Morris L, CAPRISA 002 Study Team . 2007. Neutralizing antibody responses in acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C infection. J Virol 81:6187–6196. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00239-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doria-Rose NA, Klein RM, Daniels MG, O’Dell S, Nason M, Lapedes A, Bhattacharya T, Migueles SA, Wyatt RT, Korber BT, Mascola JR, Connors M. 2010. Breadth of human immunodeficiency virus-specific neutralizing activity in sera: clustering analysis and association with clinical variables. J Virol 84:1631–1636. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01482-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pegu A, Borate B, Huang Y, Pauthner MG, Hessell AJ, Julg B, Doria-Rose NA, Schmidt SD, Carpp LN, Cully MD, Chen X, Shaw GM, Barouch DH, Haigwood NL, Corey L, Burton DR, Roederer M, Gilbert PB, Mascola JR, Huang Y. 2019. A meta-analysis of passive immunization studies shows that serum-neutralizing antibody titer associates with protection against SHIV challenge. Cell Host Microbe 26:336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Corey L, Gilbert PB, Juraska M, Montefiori DC, Morris L, Karuna ST, Edupuganti S, Mgodi NM, deCamp AC, Rudnicki E, et al. 2021. Two randomized trials of neutralizing antibodies to prevent HIV-1 acquisition. N Engl J Med 384:1003–1014. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gilbert PB, Huang Y, deCamp AC, Karuna S, Zhang Y, Magaret CA, Giorgi EE, Korber B, Edlefsen PT, Rossenkhan R, et al. 2022. Neutralization titer biomarker for antibody-mediated prevention of HIV-1 acquisition. Nat Med 28:1924–1932. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01953-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lynch RM, Boritz E, Coates EE, DeZure A, Madden P, Costner P, Enama ME, Plummer S, Holman L, Hendel CS, et al. 2015. Virologic effects of broadly neutralizing antibody VRC01 administration during chronic HIV-1 infection. Sci Transl Med 7:319ra206. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad5752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Caskey M, Klein F, Lorenzi JCC, Seaman MS, West AP Jr, Buckley N, Kremer G, Nogueira L, Braunschweig M, Scheid JF, Horwitz JA, Shimeliovich I, Ben-Avraham S, Witmer-Pack M, Platten M, Lehmann C, Burke LA, Hawthorne T, Gorelick RJ, Walker BD, Keler T, Gulick RM, Fätkenheuer G, Schlesinger SJ, Nussenzweig MC. 2015. Viraemia suppressed in HIV-1-infected humans by broadly neutralizing antibody 3BNC117. Nature 522:487–491. doi: 10.1038/nature14411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bar-On Y, Gruell H, Schoofs T, Pai JA, Nogueira L, Butler AL, Millard K, Lehmann C, Suárez I, Oliveira TY, et al. 2018. Safety and antiviral activity of combination HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies in viremic individuals. Nat Med 24:1701–1707. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0186-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crowell TA, Colby DJ, Pinyakorn S, Sacdalan C, Pagliuzza A, Intasan J, Benjapornpong K, Tangnaree K, Chomchey N, Kroon E, et al. 2019. Safety and efficacy of VRC01 broadly neutralising antibodies in adults with acutely treated HIV (RV397): a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet HIV 6:e297–e306. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30053-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bar KJ, Sneller MC, Harrison LJ, Justement JS, Overton ET, Petrone ME, Salantes DB, Seamon CA, Scheinfeld B, Kwan RW, et al. 2016. Effect of HIV antibody VRC01 on viral rebound after treatment interruption. N Engl J Med 375:2037–2050. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scheid JF, Horwitz JA, Bar-On Y, Kreider EF, Lu C-L, Lorenzi JCC, Feldmann A, Braunschweig M, Nogueira L, Oliveira T, et al. 2016. HIV-1 antibody 3BNC117 suppresses viral rebound in humans during treatment interruption. Nature 535:556–560. doi: 10.1038/nature18929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mendoza P, Gruell H, Nogueira L, Pai JA, Butler AL, Millard K, Lehmann C, Suárez I, Oliveira TY, Lorenzi JCC, et al. 2018. Combination therapy with anti-HIV-1 antibodies maintains viral suppression. Nature 561:479–484. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0531-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burton DR. 2019. Advancing an HIV vaccine; advancing vaccinology. Nat Rev Immunol 19:77–78. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0103-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leggat DJ, Cohen KW, Willis JR, Fulp WJ, deCamp AC, Kalyuzhniy O, Cottrell CA, Menis S, Finak G, Ballweber-Fleming L, et al. 2022. Vaccination induces HIV broadly neutralizing antibody precursors in humans. Science 378:eadd6502. doi: 10.1126/science.add6502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moore PL. 2022. Triggering rare HIV antibodies by vaccination. Science 378:949–950. doi: 10.1126/science.adf3722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kwong PD, Doyle ML, Casper DJ, Cicala C, Leavitt SA, Majeed S, Steenbeke TD, Venturi M, Chaiken I, Fung M, Katinger H, Parren PWIH, Robinson J, Van Ryk D, Wang L, Burton DR, Freire E, Wyatt R, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA, Arthos J. 2002. HIV-1 evades antibody-mediated neutralization through conformational masking of receptor-binding sites. Nature 420:678–682. doi: 10.1038/nature01188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Ueberheide B, Diskin R, Klein F, Oliveira TYK, Pietzsch J, Fenyo D, Abadir A, Velinzon K, Hurley A, Myung S, Boulad F, Poignard P, Burton DR, Pereyra F, Ho DD, Walker BD, Seaman MS, Bjorkman PJ, Chait BT, Nussenzweig MC. 2011. Sequence and structural convergence of broad and potent HIV antibodies that mimic CD4 binding. Science 333:1633–1637. doi: 10.1126/science.1207227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu X, Zhou T, Zhu J, Zhang B, Georgiev I, Wang C, Chen X, Longo NS, Louder M, McKee K, et al. 2011. Focused evolution of HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies revealed by structures and deep sequencing. Science 333:1593–1602. doi: 10.1126/science.1207532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wibmer CK, Bhiman JN, Gray ES, Tumba N, Abdool Karim SS, Williamson C, Morris L, Moore PL. 2013. Viral escape from HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies drives increased plasma neutralization breadth through sequential recognition of multiple epitopes and immunotypes. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003738. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bhiman JN, Anthony C, Doria-Rose NA, Karimanzira O, Schramm CA, Khoza T, Kitchin D, Botha G, Gorman J, Garrett NJ, Abdool Karim SS, Shapiro L, Williamson C, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Morris L, Moore PL. 2015. Viral variants that initiate and drive maturation of V1V2-directed HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies. Nat Med 21:1332–1336. doi: 10.1038/nm.3963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sather DN, Carbonetti S, Malherbe DC, Pissani F, Stuart AB, Hessell AJ, Gray MD, Mikell I, Kalams SA, Haigwood NL, Stamatatos L. 2014. Emergence of broadly neutralizing antibodies and viral coevolution in two subjects during the early stages of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 88:12968–12981. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01816-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Umotoy J, Bagaya BS, Joyce C, Schiffner T, Menis S, Saye-Francisco KL, Biddle T, Mohan S, Vollbrecht T, Kalyuzhniy O, Madzorera S, Kitchin D, Lambson B, Nonyane M, Kilembe W, Investigators IPC, Network I, Poignard P, Schief WR, Burton DR, Murrell B, Moore PL, Briney B, Sok D, Landais E. 2019. Rapid and focused maturation of a VRC01-class HIV broadly neutralizing antibody lineage involves both binding and accommodation of the N276-glycan. Immunity 51:141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Landais E, Murrell B, Briney B, Murrell S, Rantalainen K, Berndsen ZT, Ramos A, Wickramasinghe L, Smith ML, Eren K, et al. 2017. HIV envelope glycoform heterogeneity and localized diversity govern the initiation and maturation of a V2 apex broadly neutralizing antibody lineage. Immunity 47:990–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. MacLeod DT, Choi NM, Briney B, Garces F, Ver LS, Landais E, Murrell B, Wrin T, Kilembe W, Liang C-H, Ramos A, Bian CB, Wickramasinghe L, Kong L, Eren K, Wu C-Y, Wong C-H, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Wilson IA, Burton DR, Poignard P, IAVI Protocol C Investigators & The IAVI African HIV Research Network . 2016. Early antibody lineage diversification and independent limb maturation lead to broad HIV-1 neutralization targeting the Env high-mannose patch. Immunity 44:1215–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bonsignori M, Kreider EF, Fera D, Meyerhoff RR, Bradley T, Wiehe K, Alam SM, Aussedat B, Walkowicz WE, Hwang K-K, et al. 2017. Staged induction of HIV-1 glycan-dependent broadly neutralizing antibodies. Sci Transl Med 9:eaai7514. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai7514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Simonich CA, Williams KL, Verkerke HP, Williams JA, Nduati R, Lee KK, Overbaugh J. 2016. HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies with limited hypermutation from an infant. Cell 166:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krebs SJ, Kwon YD, Schramm CA, Law WH, Donofrio G, Zhou KH, Gift S, Dussupt V, Georgiev IS, Schätzle S, et al. 2019. Longitudinal analysis reveals early development of three MPER-directed neutralizing antibody lineages from an HIV-1-infected individual. Immunity 50:677–691. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Doria-Rose NA, Landais E. 2019. Coevolution of HIV-1 and broadly neutralizing antibodies. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 14:286–293. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Doria-Rose NA, Bhiman JN, Roark RS, Schramm CA, Gorman J, Chuang GY, Pancera M, Cale EM, Ernandes MJ, Louder MK, et al. 2016. New member of the V1V2-directed CAP256-VRC26 lineage that shows increased breadth and exceptional potency. J Virol 90:76–91. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01791-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liao H-X, Lynch R, Zhou T, Gao F, Alam SM, Boyd SD, Fire AZ, Roskin KM, Schramm CA, Zhang Z, et al. 2013. Co-evolution of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody and founder virus. Nature 496:469–476. doi: 10.1038/nature12053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]