ABSTRACT

Pseudorabies virus (PRV) is the causative agent of Aujeszky’s disease, which is responsible for enormous economic losses to the global pig industry. Although vaccination has been used to prevent PRV infection, the effectiveness of vaccines has been greatly diminished with the emergence of PRV variants. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop anti-PRV drugs. Polyethylenimine (PEI) is a cationic polymer and has a wide range of antibacterial and antiviral activities. This study found that a low dose of 1 µg/mL of the 25-kDa linear PEI had significantly specific anti-PRV activity, which became more intense with increasing concentrations. Mechanistic studies revealed that the viral adsorption stage was the major target of PEI without affecting viral entry, replication stages, and direct inactivation effects. Subsequently, we found that cationic polymers PEI and Polybrene interfered with the interaction between viral proteins and cell surface receptors through electrostatic interaction to exert the antiviral function. In conclusion, cationic polymers such as PEI can be a category of options for defense against PRV. Understanding the anti-PRV mechanism also deepens host-virus interactions and reveals new drug targets for anti-PRV.

IMPORTANCE

Polyethylenimine (PEI) is a cationic polymer that plays an essential role in the host immune response against microbial infections. However, the specific mechanisms of PEI in interfering with pseudorabies virus (PRV) infection remain unclear. Here, we found that 25-kDa linear PEI exerted mechanisms of antiviral activity and the target of its antiviral activity was mainly in the viral adsorption stage. Correspondingly, the study demonstrated that PEI interfered with the virus adsorption stage by electrostatic adsorption. In addition, we found that cationic polymers are a promising novel agent for controlling PRV, and its antiviral mechanism may provide a strategy for the development of antiviral drugs.

KEYWORDS: pseudorabies virus, polyethylenimine, viral adsorption, electrostatic interaction

INTRODUCTION

Pseudorabies virus (PRV) is an enveloped double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily under the family Herpesviridae, which is the causative agent of Aujeszky’s disease (1, 2). PRV has a broad host range, including ruminants, carnivores, and rodents and can even overcome the species barrier to infect humans (3, 4). In addition, the pigs are the natural host and reservoir of PRV, manifested as respiratory disease, abortions, stillbirths or mummified fetuses in sows, reproductive disorders in adult pigs, and neurological symptoms with high mortality in piglets, respectively (5). Furthermore, the Aujeszky’s disease is still a vital zoonotic pathogen that causes major economic losses in the global pig industry in Asian areas, especially in China (6, 7).

So far, vaccination is an effective strategy for preventing and eradicating pseudorabies disease. Although gene-deleted PRV live vaccination such as Bartha-K61 vaccines is well implemented in most countries and the prevalence of the virus is effectively controlled, it remains an essential pathogen in the pig industry (8, 9). However, since 2011, many PRV variants have occurred along with increased virulence, and the classical Bartha-K61 vaccine could not provide complete protection against PRV variants (10, 11). Moreover, increasing numbers of studies have reported human cases of PRV infection accompanied by classic clinical symptoms of fever and inflammation, suggesting that PRV poses a significant threat to mammals and even to humans and is a growing threat to public and human health (12). Therefore, research on effective anti-PRV drugs and a deep understanding of virus-host cell interactions are imperative.

Polyethylenimine (PEI) is a cationic polymer with multiple molecular weights and linear and branched forms. Due to its excellent DNA-binding ability, PEI is a DNA transfection reagent facilitating gene entry into target cells (13). Studies have shown that PEI and its derivatives have many antibacterial and antiviral activities (14, 15). PEI has a synergistic antimicrobial effect with various antibacterial compounds and can also kill bacteria by rupturing cell membranes (16). Meanwhile, the linear 25-kDa PEI can effectively inhibit the infection of human papillomavirus (HPVs) and human cytomegalovirus (HCMVs) by inhibiting virus binding to cells (17). As reported by Wang and colleagues, the 40-kDa linear PEI inhibits porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) infection by blocking its attachment (18). The inhibitory mechanism of PEIs on virus infection is unclear. Furthermore, Larson et al. reported that N, N-dodecyl and methyl-PEI can inactivate herpes simplex viruses (HSVs) 1 and 2 (19). Thus, the effect of PEI on PRV infection and its antiviral mechanism needs further study.

Our study examined the antiviral activities of the 25-kDa PEI against PRV. We found that the PEI exhibited remarkable anti-PRV activity in vitro. Furthermore, we further explored the mechanism of inhibition of PRV infection. Our results showed that the PEI could reduce the attachment of PRV to susceptible cells to inhibit its infection. Remarkably, a variety of cationic polymers have this anti-PRV effect. In addition, we found that the inhibition of virus adsorption was related to the electrostatic interaction of virus proteins with cell surface receptors. Based on these data, we validated the anti-PRV effect of PEI and identified its potential antiviral mechanism.

RESULTS

Cytotoxicity of compounds

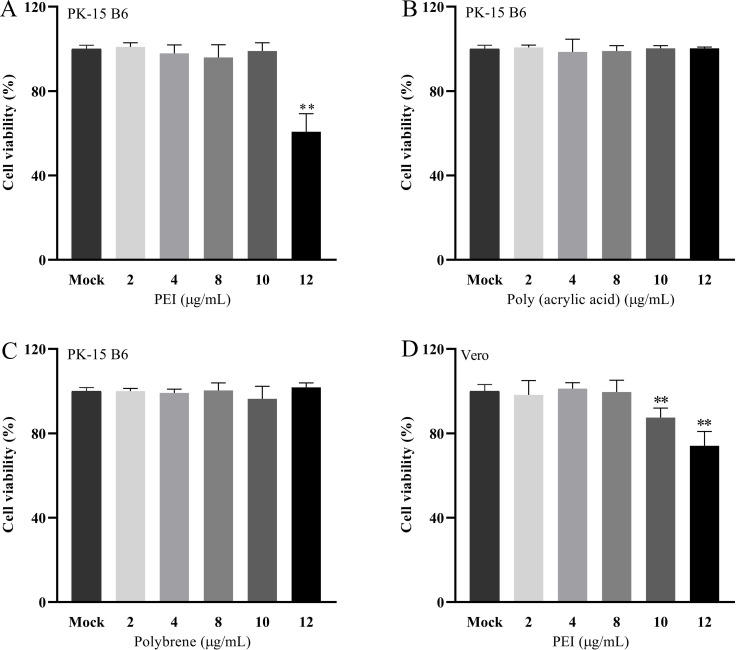

The cytotoxicity of 25-kDa linear PEI, Poly (acrylic acid), and Polybrene on PK-15 B6 or Vero cells was evaluated by CCK-8 assay with the concentrations of 2 µg/mL, 4 µg/mL, 8 µg/mL, 10 µg/mL, and 12 µg/mL, respectively. The results showed that Poly (acrylic acid) and Polybrene at concentrations 0–12 μg/mL exhibited no significant cytotoxicity to PK-15 B6 cells (Fig. 1B and C). Only the PEI showed moderate toxicity at 12 µg/mL for PK-15 B6 cells, with cell viability of approximately 60%, and over 8 µg/mL for Vero cells (Fig. 1A and D).

Fig 1.

The cell viability of the 25-kDa linear PEI, Poly (acrylic acid), and Polybrene was determined by the CCK-8 assay. A, B, C, and D correspond to cell viability of PEI, Poly (acrylic acid), and Polybrene. The results are the averages ± SD of experiments performed six times. Statistical significance is as follows: **P < 0.01.

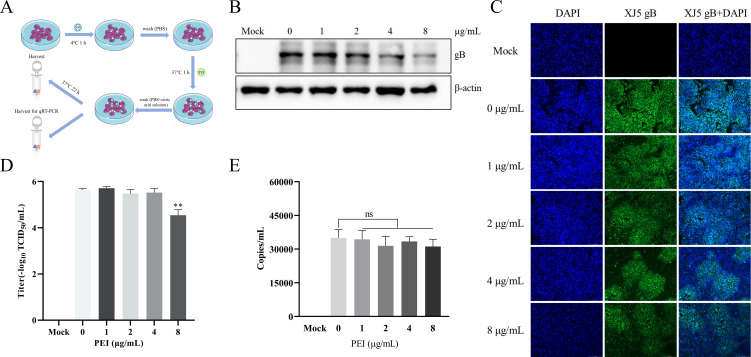

PEI specifically inhibits PRV infection in vitro

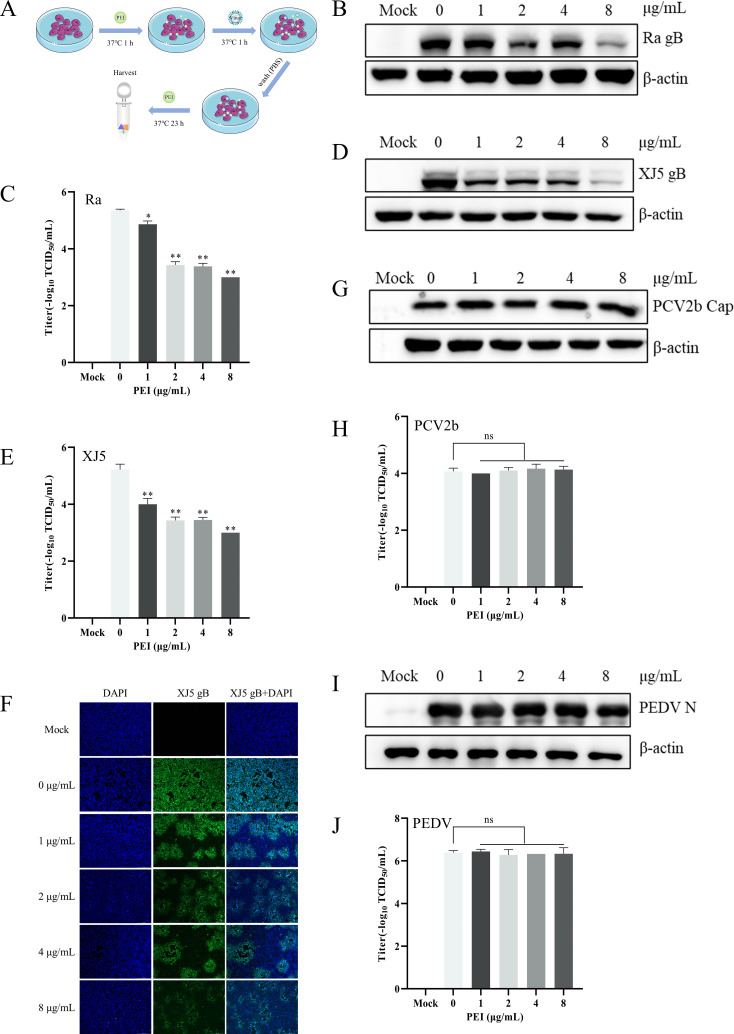

To determine whether PEI had specifically anti-PRV effects in vitro, we examined the antiviral effect of PEI as designed in Fig. 2A. PK-15 B6 cells were pretreated with different concentrations of PEI (1, 2, 4, and 8 µg/mL) for 1 h and then infected with PRV/Ra and PRV/XJ5 [0.1 multiplicity of infection (MOI)] for 24 hpi in the presence of different concentrations of PEI. The anti-PRV effects of PEI were evaluated by detecting the expression of glycoprotein B (gB) by western blotting assays. The results showed that PEI significantly reduced the expression of viral protein in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2B and D). Specifically, PEI showed the strongest inhibitory effect and almost completely inhibited the PRV infection at 8 µg/mL. Furthermore, the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) results also indicated that the production of viral particles in cell supernatants was reduced by 2.35 and 2.22 logs for strains PRV/Ra and PRV/XJ5, respectively (Fig. 2C and E). The cytopathic effect induced by PRV/XJ5 infection was significantly attenuated by treatment with the PEI (Fig. 2F). To determine whether PEI had specifically anti-PRV effects in vitro, PK-15 B6 cells were pretreated with different concentrations of PEI (1, 2, 4, and 8 µg/mL) for 1 h and then infected with PCV2b and PEDV HLJBY strains (0.1 MOI) for 24 hpi in the presence of different concentrations of PEI. The western blotting and TCID50 results showed that PEI did not interfere with the proliferation of PCV2b and PEDV (Fig. 2G through J).

Fig 2.

PEI specifically inhibited PRV infection. PK-15 B6 or Vero cells were pretreated with different concentrations of PEI for 1 h before being infected with PRV/Ra, PRV/XJ5, PCV2b, and PEDV strains (0.1 MOI) in the presence of the PEI, and then, the infected cells were incubated with the corresponding concentration of PEI for 24 hpi. (A) Schematic diagram of the infection experimental setup. B, D, G, and I correspond to the expression levels of viral proteins of the PRV/Ra, PRV/XJ5, PCV2b, and PEDV strains, respectively. (F) The detection of internalized viruses by immunofluorescent assay (IFA). C, E, H, and J correspond to virus titers in the supernatant after infection with the PRV/Ra, PRV/XJ5, PCV2b, and PEDV strains by TCID50 assay, respectively. Statistical significance is as follows: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

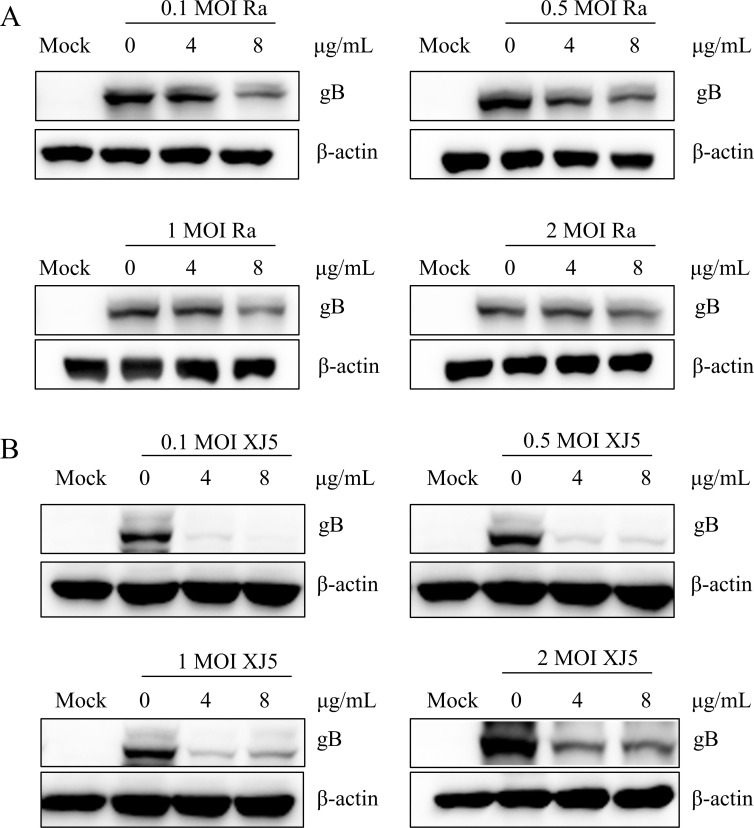

To further investigate the antiviral effects of PEI on the association with MOIs of PRV infection, PK-15 B6 cells were infected with different MOIs PRV in the presence of different concentrations of PEI (4 µg/mL, 8 µg/mL). Western blotting results revealed that PEI still had significant antiviral effects on different MOIs PRV/Ra (Fig. 3A) and PRV/XJ5 strains (Fig. 3B) (P < 0.01). These results fully prove the specific anti-PRV activity of PEI.

Fig 3.

PEI inhibited PRV infection in PK-15 B6 cells at different MOIs. A and B correspond to the expression levels of gB protein of PRV/XJ5 and PRV/Ra by western blotting, respectively.

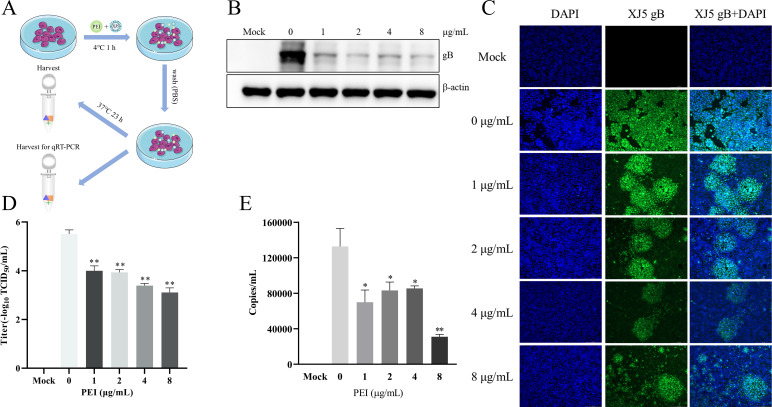

PEI inhibits PRV adsorption and entry in PK-15 B6 cells

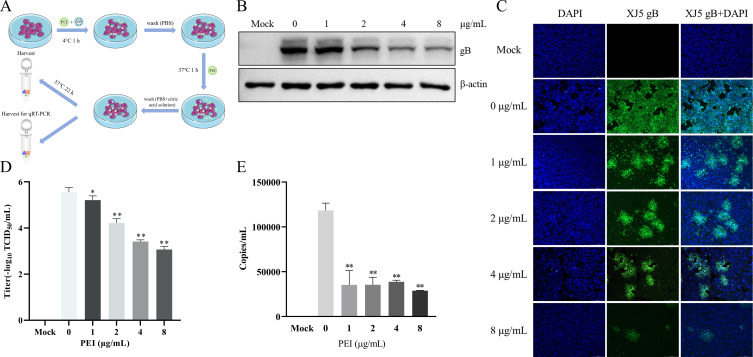

To further explore the anti-PRV mechanisms of PEI in vitro, we investigated the anti-PRV effect of PEI under different conditions, as previously described in the literature (20). In addition, we further clarified the effect of PEI on the viral adsorption and entry stages through the treatment of PK-15 B6 cells with PEI during the adsorption and entry stages of PRV infection as designed in Fig. 4A. The western blotting results showed that PEI significantly reduced intracellular gB expression with an inhibition rate of 33.7%–60.7% in a PEI dose-dependent manner (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4B). Similarly, the reduction of PRV infection in PK-15 B6 cells treated with PEI in different concentrations was visualized by IFA (Fig. 4C). The TCID50 results revealed that the PEI could significantly reduce the virus titer with approximately 2 logs compared with the PRV-only treatment group at 8 µg/mL PEI (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, we found that the viral DNA level of PEI treatment group was significantly decreased compared with the PRV-only treatment group, and the highest inhibition rate could reach 75.7% (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4E). These results demonstrated that PEI could inhibit the adsorption and entry stages of PRV infection.

Fig 4.

PEI suppressed adsorption and entry stages of PRV infection in PK-15 B6 cells. PK-15 B6 cells were infected with PRV/XJ5 at 4°C for 1 h in the presence of different concentrations of PEI, incubated with corresponding concentrations of PEI at 37°C for 1 h, and then washed off the extracellular virus, followed by incubation without PEI to 24 hpi. (A) Schematic diagram of the virus adsorption and entry experimental setup. (B) PRV/XJ5 gB protein levels were detected by western blotting. (C) The detection of internalized viruses by IFA. (D) Virus titers were determined by TCID50 assay. (E) The virus DNA was quantified by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). Statistical significance is shown as follows: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

PEI does not predominantly affect PRV entry in PK-15 B6 cells

To further understand the target stages of PEI, we first examined the effect of PEI on the entry stage of PRV infection as designed in Fig. 5A. The western blotting results showed that PEI significantly reduced intracellular gB expression at 4 µg/mL and 8 µg/mL (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5B). Only small reductions in internalized viruses caused by PRV infection were observed by IFA at 4 µg/mL and 8 µg/mL (Fig. 5C). The TCID50 results revealed that the virus titer was reduced at 8 µg/mL (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, the intracellular virus DNA level of the PEI treatment group was not significantly different (Fig. 5E). Altogether, we found that PEI inhibited virus entry only at 8 µg/mL during PRV infection.

Fig 5.

PEI effects on PRV entry in PK-15 B6 cells. PK-15 B6 cells were infected with PRV/XJ5 at 4°C for 1 h and then incubated with different concentrations of PEI for 1 h at 37°C, followed by washing off the extracellular virus and incubated without PEI for 24 hpi. (A) Schematic diagram of the virus entry experimental setup. (B) PRV/XJ5 gB protein levels were detected by western blotting. (C) The detection of internalized viruses by IFA. (D) Virus titers were determined by TCID50 assay. (E) The intracellular virus DNA was quantified by qRT-PCR. Statistical significance is as follows: **P < 0.01 and ns, not significant.

PEI prevents PRV adsorption in PK-15 B6 cells

PEI plays an essential role in the adsorption and entry stages during PRV infection. However, it plays a minor role in the viral entry stage. Therefore, we proceeded to validate the function of PEI in the adsorption stage during PRV infection as shown in Fig. 6A. Western blotting results showed significantly inhibited intracellular gB expression at each concentration (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6B). Similarly, the IFA results further validated the inhibitory effect of PEI (Fig. 6C). The viral titer decreased significantly with increasing PEI concentration, and the inhibition rate was 99.4% at 8 µg/mL (Fig. 6D). After PEI treatment, the number of viruses adsorbed on the cell surface was significantly reduced compared with the PRV-only treatment group by qRT-PCR with the decrease rate of approximately 76.6% at 8 µg/mL (Fig. 6E). These results indicated that the major antiviral target of PEI is the adsorption stage of the PRV infection.

Fig 6.

PEI blocked PRV adsorption in PK-15 B6 cells. PK-15 B6 cells were infected with PRV/XJ5 at 4°C for 1 h in the presence of different concentrations of PEI and then incubated without PEI for 24 hpi. (A) Schematic diagram of the virus adsorption experimental setup. (B) PRV/XJ5 gB protein levels were detected by western blotting. (C) The detection of internalized viruses by IFA. (D) Virus titers were determined by TCID50 assay. (E) The cell surface virus DNA was quantified by qRT-PCR. Statistical significance is as follows: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

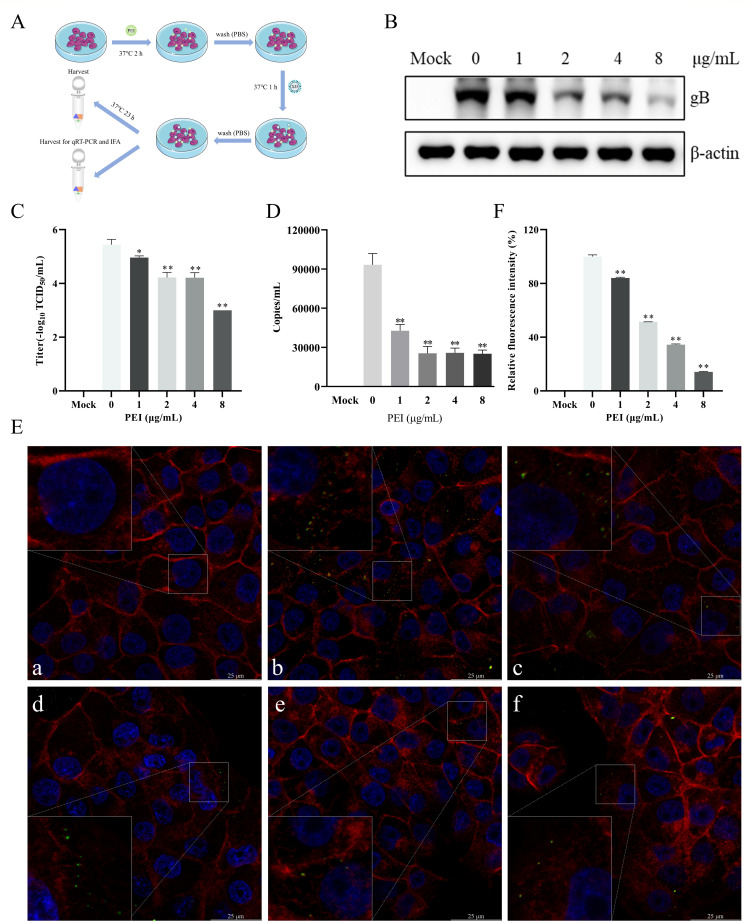

PK-15 B6 cell pretreatment inhibits PRV infection by suppressing viral adsorption

To further explore the anti-PRV mechanisms in the pretreatment stage of PEI, we examined the anti-PRV effects of PEI under different treatments as designed in Fig. 7A. Then, the gB protein expression and virus titer were measured by the western blotting and TCID50 assays, respectively. The results showed that PEI pretreatment significantly reduced intracellular gB expression (P < 0.01) (Fig. 7B) and viral titer (P < 0.01) (Fig. 7C), indicating that PEI-pretreated PK-15 B6 cells significantly inhibited PRV infection. Next, we hypothesized that PEI pretreatment inhibits PRV infection by targeting the viral adsorption stage. As expected, qRT-PCR results showed that viral DNA on adsorbed cell surfaces was significantly reduced at each concentration of PEI treatment (P < 0.01) (Fig. 7D). Moreover, we observed that PEI pretreatment blocked the attachment of PRV virions by laser scanning confocal microscope (LSCM) (P < 0.01) (Fig. 7E and F). These results suggested that PEI pretreatment targets viral attachment to exert anti-PRV activity.

Fig 7.

PEI pretreatment inhibited PRV infection. PK-15 B6 cells were pretreated with different concentrations of PEI at 37°C for 2 h and then infected with PRV/XJ5. (A) Schematic diagram of the PEI pretreatment experimental setup. (B) PRV/XJ5 gB protein levels were detected by western blotting. (C) Virus titers were determined by TCID50 assay. (D) The cell surface virus DNA was quantified by qRT-PCR. (E) The adsorbed PRV virions were observed through LSCM, and a, b, c, d, e, and f correspond to the negative control group, PRV-only treated group, and 1, 2, 4, and 8 µg/mL PEI-treated groups, respectively. The green points indicate PRV virions. (F) Relative fluorescence intensity analysis of PRV virions adsorbed to the cell surface. Statistical significance is as follows: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

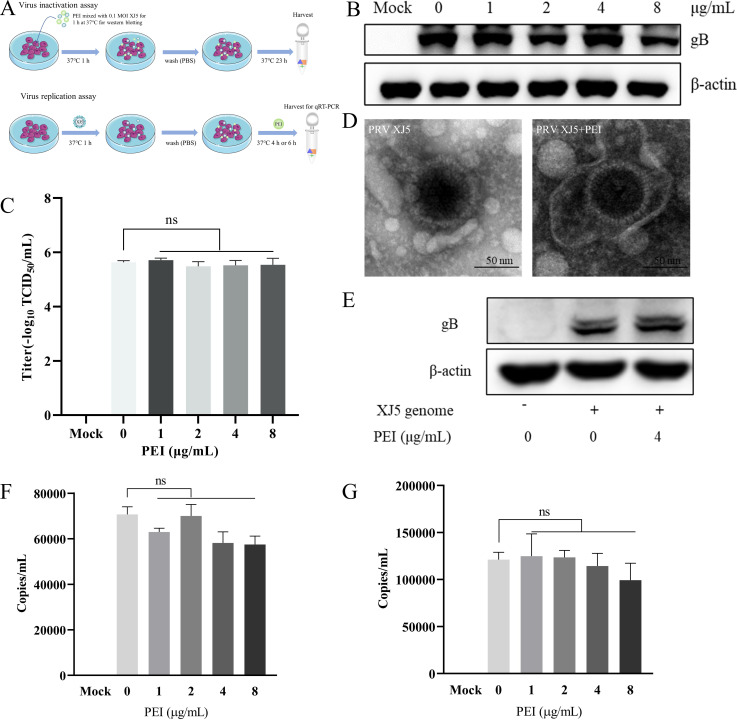

PEI does not have impact on the viral replication stage and disrupt the virion structure

Next, we investigated whether PEI treatment inhibited the viral replication stage and disrupted the PRV virion structure as shown in Fig. 8A. The western blotting and TCID50 assay results showed that PEI could not directly inhibit the PRV infection activity (Fig. 8B and C). Then, we investigated the potential capability of PEI to disrupt the structure of PRV virions via electron microscopy. The results further suggested that PEI could not directly disrupt PRV virions (Fig. 8D). In addition, at the stage of viral replication, co-incubation of the cells transfected with the PRV/XJ5 genome with PEI had no effect on the expression levels of gB protein (Fig. 8E). Meanwhile, co-incubation with PEI after PRV infected cells did not influence the amount of intracellular virus DNA by qRT-PCR (Fig. 8F and G). The results indicated that PEI does not have impact on the viral replication stage.

Fig 8.

PEI did not act on the viral replication stage and disrupt the viral virions. PK-15 B6 cells were infected with the mixture of PEI co-incubated with PRV/XJ5 or added with different concentrations of PEI within the post-infection replication stage to observe the effect on PRV replication. (A) Schematic diagram of the virus replication and inactivation experimental setup. (B) PRV/XJ5 gB protein levels were detected by western blotting. (C) Virus titers were determined by TCID50 assay. (D) The purified PRV/XJ5 virions were incubated with 4 µg/mL PEI for 1 h at 37°C. Then, virus suspensions were prepared for electron microscopy observation. (E) Vero cells were transfected with the genome of PRV/XJ5 for 36 h, and then, the cells were treated with 4 µg/mL PEI for 6 h. After treatment, the cells were collected to detect gB protein levels by western blotting. (F and G) The intracellular virus DNA were quantified by qRT-PCR at 4 and 6 hpi, respectively. Statistical significance is as follows: ns, not significant.

PEI inhibits virus adsorption during PRV infection by electrostatic interaction

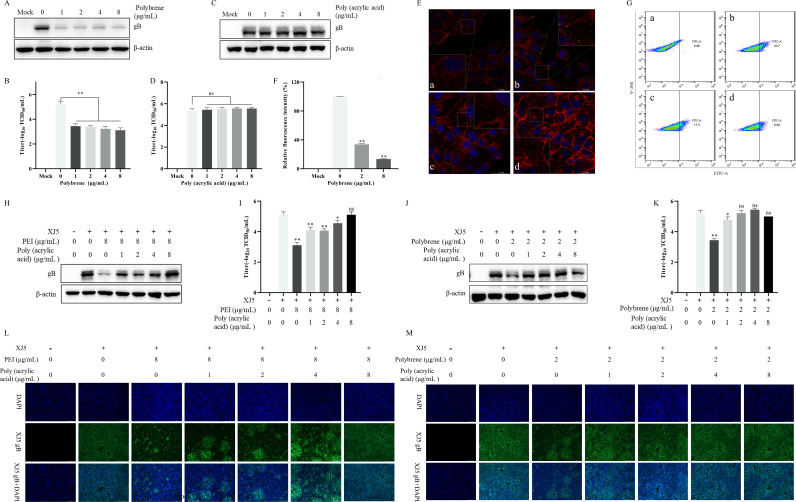

We found that the anti-PRV activity of PEI is closely related to the stage of virus adsorption. Previous studies have suggested electrostatic interactions are potential mechanisms influencing viral adsorption (17, 21–23). To confirm whether PEI exerts the antiviral mechanism, we first pretreated cells with two ionic polymers, Polybrene and Poly (acrylic acid), to explore their effects on PRV infection. Interestingly, we found the cationic polymer Polybrene inhibited PRV infection by western blotting and TCID50 assay (P < 0.01) (Fig. 9A and B). However, the anionic polymer Poly (acrylic acid) did not influence PRV infection (Fig. 9C and D). Subsequently, we investigated whether the pretreatment of Polybrene affected the adsorption of PRV virions. Similarly, a significant decrease in adsorbed PRV virions after Polybrene pretreatment was observed by LSCM (P < 0.01) (Fig. 9E and F). These results demonstrated that cationic polymers have an inhibitory effect on PRV infection by inhibiting viral adsorption. The DiBAC4(3) was applied to measure changes in cell membrane potentials (24, 25). Furthermore, we found that PEI treatment enhanced cell membrane hyperpolarization with increasing concentration (P < 0.01) (Fig. 9G). These results suggested that the potential reason for the antiviral mechanism of cationic polymers is cell membrane hyperpolarization to interfere with virus adsorption. To further validate the view, we found the co-incubation of 8 µg/mL PEI with different concentrations of Poly (acrylic acid), followed by pretreatment of cells, caused attenuation of the anti-PRV activity of PEI with increasing Poly (acrylic acid) concentration (Fig. 9H and I), which was consistent with the results of 2 µg/mL Polybrene in Fig. 9J and K. Meanwhile, co-incubation of 8 µg/mL PEI or 2 µg/mL Polybrene with different concentrations of Poly (acrylic acid) was able to significantly increase the levels of internalized viruses by IFA (Fig. 9L and M), even to the same extent as the PRV-infected group in the absence of drugs. Based on the above results, PEI inhibits virus attachment during PRV infection by electrostatic interaction.

Fig 9.

Electrostatic interaction was responsible for the anti-PRV activity of PEI by interfering with virus attachment. PK-15 B6 cells were pretreated with different concentrations of Polybrene and Poly (acrylic acid), the mixtures of 8 µg/mL PEI with different concentrations of Poly (acrylic acid), or the mixtures of 2 µg/mL Polybrene with different concentrations of Poly (acrylic acid) at 37℃ for 2 h and then infected with PRV/XJ5. A, C, H, and J correspond to the gB protein levels detected by western blotting after pretreatment of cells with different concentrations of Polybrene and Poly (acrylic acid), the mixtures of 8 µg/mL PEI with different concentrations of Poly (acrylic acid), or the mixtures of 2 µg/mL Polybrene with different concentrations of Poly (acrylic acid), respectively. B, D, I, and K correspond to virus titers determined by TCID50 assay in the supernatant after pretreatment of cells with different concentrations of Polybrene and Poly (acrylic acid), the mixtures of 8 µg/mL PEI with different concentrations of Poly (acrylic acid), or the mixtures of 2 µg/mL Polybrene with different concentrations of Poly (acrylic acid), respectively. (E) The adsorbed virus particle was observed through LSCM, and a, b, c, and d correspond to the negative control group, PRV-only treated group, 2 and 8 µg/mL Polybrene-treated groups, respectively. The green points indicate PRV virions. (F) Relative fluorescence intensity analysis of PRV virions adsorbed to the cell surface. (G) The detection of cell membrane potential in PEI-pretreated cells by flow cytometry; a, b, c, and d correspond to the blank control group, DiBAC4(3)-only-treated group, and 2 and 8 µg/mL PEI-treated groups, respectively. L and M correspond to the detection of internalized viruses by IFA after pretreatment of cells with the mixtures of 8 µg/mL PEI with different concentrations of Poly (acrylic acid) and the mixtures of 2 µg/mL Polybrene with different concentrations of Poly (acrylic acid), respectively. Statistical significance is as follows: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

DISCUSSION

PEI is a cationic polymer in linear, branched, and dendritic forms, usually used for gene delivery. It is reported that PEI can also be used to prepare vaccine adjuvants to enhance the immune response of vaccines (26, 27). At the same time, PEI and antiviral activities have also been widely proven. The linear 25-kDa PEI acting on virus adsorption to cells significantly inhibited viral infection by inhibiting the binding of HPV and HCMV to its receptor HSPG (17). Maitani et al. reported the branched 3,610-Da combined with liposomes exerts a strong antiviral effect on herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) in a mouse model (23). In this study, we attempted to investigate the anti-PRV activity and mechanism of the linear 25-kDa PEI. We found that the PEI had specific anti-PRV activity in vitro, independent of the inoculation dose, but PEI had no antiviral activity against PCV2b and PEDV (Fig. 2 and 3). We hypothesized that the difference in antiviral effect is related to the charge carried by the viral virions of PRV, PCV2, and PEDV, which intervenes in the adsorption stage of the viruses to the host cells by electrostatic interaction.

Furthermore, previous research has shown that the 40-kDa linear PEI inhibits PRRSV infection by blocking its attachment in vitro. Meanwhile, a highly cationic polyethylenimine, Epomin SP-012, was discovered to show potent activity against HSV-1 and HSV-2 via inhibiting HSV-2 adhesion to host cells and cell-to-cell spread of infection in a dose-dependent manner (28). Therefore, we explored the anti-PRV mechanism of the PEI. We found that PEI significantly inhibited viral infection after treatment at the adsorption and entry stages of viral infection (Fig. 4). Meanwhile, further research revealed that PEI mainly inhibited the adsorption stage of PRV infection rather than the entry stage (Fig. 5 and 6).

In addition, pretreatment with the PEI showed a significant anti-PRV effect in vitro via inhibiting the viral attachment, and the reduction of adsorbed PRV virions was observed by the LSCM after pretreatment (Fig. 7). This antiviral mechanism of PEI seems to be consistent with its previous observations of PRRSV (18). Moreover, intranasal administration of 25-kDa linear PEI could strongly inhibit influenza virus infection in mice (22). The CCK-8 assay showed that PEI had obvious cytotoxicity only at the concentration of 12 µg/mL but it had obvious anti-PRV activity at the concentration of 1 µg/mL, indicating that it still maintained considerable antiviral activity at a low dose (Fig. 1), which is expected to be an anti-PRV drug to prevent PRV infection. Studies have reported that PEI and its derivatives directly interact with the virus to destroy its structure and exert antiviral activity. N,N-Dodecyl, methyl-polyethyleneimine has an inactivating effect on HIV and HSV-1 or HSV-2 (19, 29). However, our study found that PEI had no direct inactivation of PRV. In brief, virus adsorption was the major target of PEI without affecting virus entry, replication stages, and direct inactivation effects (Fig. 8).

However, it has been reported that the 70-kDa branched PEI inhibited HIV-1 adsorption to cells but accelerated HIV-1 infection, and this phenomenon was associated with the influence on the cell membrane fluidity to facilitate viral entry in cells (30). Kandi et al. reported that branched polyethyleneimine promoted HIV replication in vitro (31). PEIs have various morphologies and a wide range of molecular weights, so different PEI molecules show differences in regulating viral infections. Therefore, the effects of various types of PEIs on viruses may widely diverge.

Our study found that cationic polymers PEI and Polybrene inhibited PRV infection by reducing virus adsorption. However, anionic polymer Poly (acrylic acid) exhibited no anti-PRV activity (Fig. 9). This suggests the inhibition of viral adsorption of PEI and Polybrene is closely related to the electrostatic interaction of cell membrane surface receptors with viral proteins, consistent with previous studies, which found that PEI may interfere with the interaction between viral proteins and host receptors via electrostatic interaction (17). Furthermore, we discovered that after PEI pretreatment, the cell membrane potential was hyperpolarized through flow cytometry. This result further suggests that PEI exerts antiviral activity by changing the cell membrane potential. Additionally, we found the co-incubation of PEI or Polybrene with different concentrations of Poly (acrylic acid), followed by pretreatment of cells, caused attenuation of the anti-PRV activity of PEI with increasing Poly (acrylic acid) concentration, which further demonstrates the necessary electrostatic interaction in the adsorption of virus to host cells. Meanwhile, a variety of cationic polymers, PEI and Polybrene, have anti-PRV activity, suggesting that cationic polymers can be used as an alternative class of drugs for the prevention of PRV infection and that further research can be conducted on more suitable anti-PRV cationic polymers.

In summary, our findings provided the antiviral activity of PEI and identified cationic polymers as potential drugs for defense against PRV. Subsequently, we investigated that the cationic polymers inhibited PRV infection by interfering with viral adsorption through electrostatic interaction. These data also provide new insights into the development of antiviral drugs against PRV or other viruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses

The cell lines PK-15 B6 and Vero were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Sigma) supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin, fungizone, and 4% or 6% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Lonsera) at 37°C with 5% CO2 in an incubator (Thermo). PRV/XJ5 variant, PCV2b, and PEDV HLJBY strains were isolated and preserved by the Key Laboratory of Avian Bioproduct Development, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Yangzhou University. PRV/Ra classical strain was purchased from the China Institute of Veterinary Drug Control.

Chemicals and antibodies

Polyethylenimine, Linear, MW 25000 (PEI, catalog number 23966–1) was purchased from Polysciences. Poly (acrylic acid) (catalog number GC19724) and DiBAC4(3) (catalog number GC30140) were purchased from GLPBIO. Polybrene (catalog number H8761) was purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). The citric acid solution was composed of 40 mM citric acid, 10 mM KCl, and 135 mM NaCl, and its pH was adjusted to 3.0 to remove uninternalized virus particles.

Monoclonal antibodies against the PRV gB and PCV2b Cap protein and PRV-positive sera were developed in our laboratory. β-Actin monoclonal antibody (1:1,000, catalog number HC201–01) was purchased from TRANS (Beijing, China). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (1:5,000, catalog number A0216) was from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled rabbit anti-pig IgG (1:1,000, catalog number F1638) was from Sigma. Phalloidin-568 (catalog number A12380) was purchased from Invitrogen. DAPI (catalog number C1005) and Lipo8000 transfection reagents (catalog number C0533) were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology.

Cell viability assay

The cell viability assay was performed using the CCK-8 reagent (catalog number C0038) purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology as previously described (20). Briefly, PK-15 B6 or Vero cells were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured. Next, these cells were treated with different concentrations of compounds. At 24 h post-incubation, 10 µL of CCK-8 reagent was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 1 h in an incubator. Then, the absorbance was measured at OD450 nm.

Infectivity assay

The infectivity assay was performed as previously described (32). PK-15 B6 or Vero cells were seeded in 12-well plates, inoculated with different concentrations of PEI (1 µg/mL, 2 µg/mL, 4 µg/mL, and 8 µg/mL), and infected with strains of different viruses at MOI = 0.1. At 24 h post-infection (hpi), the cells were harvested to measure the viral level further.

Virus adsorption and entry assay

PK-15 B6 cells were infected with 0.1 MOI PRV/XJ5 at 4°C for 1 h and simultaneously supplemented with different concentrations (1 µg/mL, 2 µg/mL, 4 µg/mL, and 8 µg/mL) of PEI. Unbound viruses and residual compounds were washed three times with prechilled PBS and incubated with DMEM containing a corresponding concentration of PEI for 1 h at 37°C. Next, the cells were washed with prechilled citric acid solution and PBS thrice to remove the extracellular-bound virus (21). At 24 hpi, the cells were harvested to measure viral levels further.

PK-15 B6 was handled using the method above. Next, at 2 hpi, the cells were washed thrice with prechilled citric acid solution and PBS. The viral DNA was extracted and detected by qRT-PCR.

Virus adhesion assay

PK-15 B6 cells were infected with 0.1 MOI PRV/XJ5 at 4°C for 1 h and simultaneously supplemented with different concentrations of PEI. Unbound viruses and residual compounds were washed three times with prechilled PBS. Then, the cells were incubated with 2% FBS DMEM without PEI at 37°C. At 24 hpi, the cells were harvested to measure viral levels further.

PK-15 B6 was handled using the method above. Next, at 1 hpi, the cells were washed with prechilled PBS three times, and then, the viral DNA was extracted and detected by qRT-PCR.

Virus entry assay

PK-15 B6 cells were infected with 0.1 MOI PRV/XJ5 at 4°C for 1 h without PEI. Then, the cells were washed three times with prechilled PBS and incubated with DMEM containing different concentrations of PEI for 1 h at 37°C. Next, the cells were washed with prechilled citric acid solution and PBS thrice to remove the extracellular bound virus. At 24 hpi, the cells were harvested to measure viral levels further.

PK-15 B6 was handled using the method above. Next, at 2 hpi, the cells were washed with prechilled citric acid solution and PBS three times, respectively, and then, the viral DNA was extracted and detected by qRT-PCR.

Virus replication and inactivation assay

The various concentrations of PEI (1, 2, 4, and 8 µg/mL) with 0.1 MOI PRV/XJ5 were incubated in the system of 10 µL at 37°C for 1 h. Subsequently, the mixture was infected with PK-15 B6 cells at 37°C for 1 h. After 24 hpi, the cell protein samples and supernatants were collected for western blotting and TCID50 assays. In addition, we investigated whether PEI had the ability to disrupt the structure of PRV virions by electron microscopy. First, the purified PRV virions in the concentrated supernatant were obtained by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 3 h at 4°C. Then, the purified PRV virions were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in the absence or presence of PEI. Finally, the incubated virus suspensions were dropped onto a copper mesh, used filter paper to absorb excess virus suspensions, and then visualized by 2% phosphotungstic acid negative staining. The samples were visualized using an electron microscope (Tecnai 12; Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

PK-15 B6 cells were infected with 0.1 MOI PRV/XJ5 at 37°C for 1 h without PEI. Then, the cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with 2% FBS DMEM containing the corresponding concentration of PEI at 37°C. At 4 and 6 hpi, the viral DNA was extracted and detected by qRT-PCR. Furthermore, to further determine whether the viral replication stage is the target of the PEI effect, Vero cells were transfected with the whole genome of PRV/XJ5 for 36 h, and then, the medium was replaced with medium containing 4 µg/mL PEI. After incubation for 6 h, the cell samples were collected to detect the expression levels of gB protein.

Pretreatment assay

PK-15 B6 cells were pretreated with different concentrations of drugs in DMEM at 37°C for 2 h. Then, the cells were washed thrice with PBS and infected with 0.1 MOI PRV/XJ5 at 37°C for 1 h without PEI. At 24 hpi, the cells were harvested to measure viral levels further.

Western blot analysis

Whole-cell lysates were isolated with lysis buffer (Beyotime) and boiled in 2× Protein SDS-PAGE Loading Buffer for 15 min at 96°C. Equal amounts of whole-cell proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a Pall BioTrace NT nitrocellulose transfer membrane (Pall, New York, USA). Next, the membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies. Finally, the immunoreactive bands were stained with LumiQ HRP Substrate solution (ShareBio, Shanghai, China).

DNA extraction and qRT-PCR

The intracellular and extracellular viral DNA was extracted using the phenol chloride and detected by qRT-PCR, as described previously (33). The specific primers are as follows: gB94-F: ACAAGTTCAAGGCCCACATCTAC, gB94-R: GTCCGTGAAGCGGTTCGTGAT, gBprobe: 5’-FAM -ACGTCATCGTCACGACC-TAMRA-3’.

Virus titer assays

The TCID50 assay was performed as previously described (34). Vero cells were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured overnight in 5% CO2 at 37°C. The cell suspension was 10-fold serially diluted with DMEM to infect the cells. Each dilution was repeated eight times. After 72 hpi, the cytopathic effect was observed to calculate the TCID50 using Reed-Muench’s method.

Indirect immunofluorescent assay

PK-15 B6 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and then incubated with 0.1% TritonX-100 for 10 min at 37°C. Next, the cells were sealed overnight with 5% bovine serum albumin at 4°C. After blocking, the cells were incubated with PRV-positive porcine serum with a 1:400 dilution at 37°C for 1 h and then incubated with Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled rabbit anti-pig with a 1:200 dilution at 37℃ for 1 h. Then, the cells were incubated with DAPI for 5 min at room temperature. The cells need to be washed three times with PBS between all procedures. Finally, the cells were observed using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

PK-15 B6 cells were handled using the method above; however, before DAPI staining, cells were incubated with Phalloidin-568 at 37°C for 1 h to stain the cell membrane. Finally, the virus particle was observed using the LSCM (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Membrane potential measurements by voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye

The Bis-(1,3-dibutyl barbituric acid) Trimethine oxonol [DiBAC4(3)] was used to measure changes in the cell’s membrane potential by flow cytometry as described previously (35, 36). Briefly, PK-15 B6 cells were pretreated with different concentrations of PEI (2, 8 µg/mL) in DMEM at 37°C for 2 h. Then, the cells were washed three times with DMEM and incubated with DiBAC4(3) (250 nM) for 20 min at 37°C. After removing the supernatant, the cells were digested with trypsin and resuspended in DMEM. The fluorescence was determined using a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, New York, USA) at 516 nm.

Statistical analysis

Experimental data were shown as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was conducted by the SPSS software. One-way analysis of variance and t-test were used to analyze data obtained from three independent experiments. Statistical significance is as follows: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 and ns means insignificant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32273015), the Jiangsu Provincial Natural Science Fund for Excellent Young (BK20220114), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M632399), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20210805), and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD), and it was supported by the 111 Project (D18007) and the Top-level Talents Support Program of Yangzhou University.

Contributor Information

Song Gao, Email: gsong@yzu.edu.cn.

Jae U. Jung, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

REFERENCES

- 1. Pomeranz LE, Reynolds AE, Hengartner CJ. 2005. Molecular biology of pseudorabies virus: impact on neurovirology and veterinary medicine. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 69:462–500. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.3.462-500.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferrara G, Longobardi C, D’Ambrosi F, Amoroso MG, D’Alessio N, Damiano S, Ciarcia R, Iovane V, Iovane G, Pagnini U, Montagnaro S. 2021. Aujeszky's disease in South-Italian wild boars (Sus scrofa): a serological survey. Animals (Basel) 11:11. doi: 10.3390/ani11113298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. He W, Auclert LZ, Zhai X, Wong G, Zhang C, Zhu H, Xing G, Wang S, He W, Li K, Wang L, Han GZ, Veit M, Zhou J, Su S. 2019. Interspecies transmission, genetic diversity, and evolutionary dynamics of pseudorabies virus. J Infect Dis 219:1705–1715. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang G, Zha Z, Huang P, Sun H, Huang Y, He M, Chen T, Lin L, Chen Z, Kong Z, Que Y, Li T, Gu Y, Yu H, Zhang J, Zheng Q, Chen Y, Li S, Xia N. 2022. Structures of pseudorabies virus capsids. Nat Commun 13:1533. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29250-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zheng HH, Jin Y, Hou CY, Li XS, Zhao L, Wang ZY, Chen HY. 2021. Seroprevalence investigation and genetic analysis of pseudorabies virus within pig populations in Henan province of China during 2018-2019. Infect Genet Evol 92:104835. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu Q, Kuang Y, Li Y, Guo H, Zhou C, Guo S, Tan C, Wu B, Chen H, Wang X. 2022. The epidemiology and variation in pseudorabies virus: a continuing challenge to pigs and humans. Viruses 14:1463. doi: 10.3390/v14071463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Minamiguchi K, Kojima S, Sakumoto K, Kirisawa R. 2019. Isolation and molecular characterization of a variant of Chinese gC-genotype II pseudorabies virus from a hunting dog infected by biting a wild boar in Japan and its pathogenicity in a mouse model. Virus Genes 55:322–331. doi: 10.1007/s11262-019-01659-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Freuling CM, Müller TF, Mettenleiter TC. 2017. Vaccines against pseudorabies virus (PrV). Vet Microbiol 206:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu R, Bai C, Sun J, Chang S, Zhang X. 2013. Emergence of virulent pseudorabies virus infection in northern China. J Vet Sci 14:363–365. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2013.14.3.363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jiang C, Ma Z, Bai J, Sun Y, Cao M, Wang X, Jiang P, Liu X. 2023. Comparison of the protective efficacy between the candidate vaccine ZJ01R carrying gE/gI/TK deletion and three commercial vaccines against an emerging pseudorabies virus variant. Vet Microbiol 276:109623. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2022.109623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. An TQ, Peng JM, Tian ZJ, Zhao HY, Li N, Liu YM, Chen JZ, Leng CL, Sun Y, Chang D, Tong GZ. 2013. Pseudorabies virus variant in Bartha-K61-vaccinated pigs, China, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1749–1755. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.130177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wong G, Lu J, Zhang W, Gao GF. 2019. Pseudorabies virus: a neglected zoonotic pathogen in humans? Emerg Microbes Infect 8:150–154. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2018.1563459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Longo PA, Kavran JM, Kim MS, Leahy DJ. 2013. Transient mammalian cell transfection with polyethylenimine (PEI). Methods Enzymol 529:227–240. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-418687-3.00018-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bhattacharjee B, Jolly L, Mukherjee R, Haldar J. 2022. An easy-to-use antimicrobial hydrogel effectively kills bacteria, fungi, and influenza virus. Biomater Sci 10:2014–2028. doi: 10.1039/D2BM00134A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Akif FA, Mahmoud M, Prasad B, Richter P, Azizullah A, Qasim M, Anees M, Krüger M, Gastiger S, Burkovski A, Strauch SM, Lebert M. 2022. Polyethylenimine increases antibacterial efficiency of chlorophyllin. Antibiotics (Basel) 11:10. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11101371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Milović NM, Wang J, Lewis K, Klibanov AM. 2005. Immobilized N-alkylated polyethylenimine avidly kills bacteria by rupturing cell membranes with no resistance developed. Biotechnol Bioeng 90:715–722. doi: 10.1002/bit.20454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Spoden GA, Besold K, Krauter S, Plachter B, Hanik N, Kilbinger AFM, Lambert C, Florin L. 2012. Polyethylenimine is a strong inhibitor of human papillomavirus and cytomegalovirus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:75–82. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05147-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang J, Li J, Wang N, Ji Q, Li M, Nan Y, Zhou EM, Zhang Y, Wu C. 2019. The 40 kDa linear polyethylenimine inhibits porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection by blocking its attachment to permissive cells. Viruses 11:876. doi: 10.3390/v11090876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Larson AM, Oh HS, Knipe DM, Klibanov AM. 2013. Decreasing herpes simplex viral infectivity in solution by surface-immobilized and suspended N,N-dodecyl,methyl-polyethylenimine. Pharm Res 30:25–31. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0825-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huan C, Xu Y, Zhang W, Pan H, Zhou Z, Yao J, Guo T, Ni B, Gao S. 2022. Hippophae rhamnoides polysaccharides dampen pseudorabies virus infection through downregulating adsorption, entry and oxidative stress. Int J Biol Macromol 207:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miller JL, Weed DJ, Lee BH, Pritchard SM, Nicola AV. 2019. Low-pH endocytic entry of the porcine alphaherpesvirus pseudorabies virus. J Virol 93:e01849-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01849-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. He B, Fu Y, Xia S, Yu F, Wang Q, Lu L, Jiang S. 2016. Intranasal application of polyethyleneimine suppresses influenza virus infection in mice. Emerg Microbes Infect 5:e41. doi: 10.1038/emi.2016.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maitani Y, Ishigaki K, Nakazawa Y, Aragane D, Akimoto T, Iwamizu M, Kai T, Hayashi K. 2013. Polyethylenimine combined with liposomes and with decreased numbers of primary amine residues strongly enhanced therapeutic antiviral efficiency against herpes simplex virus type 2 in a mouse model. J Control Release 166:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Klapperstück T, Glanz D, Hanitsch S, Klapperstück M, Markwardt F, Wohlrab J. 2013. Calibration procedures for the quantitative determination of membrane potential in human cells using anionic dyes. Cytometry A 83:612–626. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adams DS, Levin M. 2012. Measuring resting membrane potential using the fluorescent voltage reporters DiBAC4(3) and CC2-DMPE. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2012:459–464. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot067702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang J, Ji Y, Wang Z, Jia Y, Zhu Q. 2022. Effective improvements to the live-attenuated Newcastle disease virus vaccine by polyethylenimine-based biomimetic silicification. Vaccine 40:886–896. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.12.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang Y, Gu P, Wusiman A, Xu S, Ni H, Qiu T, Liu Z, Hu Y, Liu J, Wang D. 2020. The immunoenhancement effects of polyethylenimine-modified Chinese yam polysaccharide-encapsulated PLGA nanoparticles as an adjuvant. Int J Nanomedicine 15:5527–5543. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S252515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hayashi K, Onoue H, Sasaki K, Lee J-B, Kumar PKR, Gopinath SCB, Maitani Y, Kai T, Hayashi T. 2014. Topical application of polyethylenimine as a candidate for novel prophylactic therapeutics against genital herpes caused by herpes simplex virus. Arch Virol 159:425–435. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1829-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gerrard SE, Larson AM, Klibanov AM, Slater NKH, Hanson CV, Abrams BF, Morris MK. 2013. Reducing infectivity of HIV upon exposure to surfaces coated with N,N-dodecyl, methyl-polyethylenimine. Biotechnol Bioeng 110:2058–2062. doi: 10.1002/bit.24867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Owada T, Miyashita Y, Motomura T, Onishi M, Yamashita S, Yamamoto N. 1998. Enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection via increased membrane fluidity by a cationic polymer. Microbiol Immunol 42:97–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1998.tb02257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kandi MR, Mohammadnejad J, Abdoli A, Amiran MR, Soleymani S, Aghasadeghi MR, Zabihollahi R, Baesi K. 2019. In vitro effect of branched polyethyleneimine (bPEI) on cells infected with human immunodeficiency virus: enhancement of viral replication. Arch Virol 164:3019–3026. doi: 10.1007/s00705-019-04426-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huan C, Yao J, Xu W, Zhang W, Zhou Z, Pan H, Gao S. 2022. Huaier polysaccharide interrupts PRV infection via reducing virus adsorption and entry. Viruses 14:745. doi: 10.3390/v14040745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhou J, Li S, Wang X, Zou M, Gao S. 2017. Bartha-k61 vaccine protects growing pigs against challenge with an emerging variant pseudorabies virus. Vaccine 35:1161–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huan C, Xu W, Guo T, Pan H, Zou H, Jiang L, Li C, Gao S. 2020. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits the life cycle of pseudorabies virus in vitro and protects mice against fatal infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:616895. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.616895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yamada A, Gaja N, Ohya S, Muraki K, Narita H, Ohwada T, Imaizumi Y. 2001. Usefulness and limitation of DiBAC4(3), a voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye, for the measurement of membrane potentials regulated by recombinant large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in HEK293 cells. Jpn J Pharmacol 86:342–350. doi: 10.1254/jjp.86.342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang P, Turnbull MW. 2018. Virus innexin expression in insect cells disrupts cell membrane potential and pH. J Gen Virol 99:1444–1452. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]