ABSTRACT

As an intrinsic cellular mechanism responsible for the internalization of extracellular ligands and membrane components, caveolae-mediated endocytosis (CavME) is also exploited by certain pathogens for endocytic entry [e.g., Newcastle disease virus (NDV) of paramyxovirus]. However, the molecular mechanisms of NDV-induced CavME remain poorly understood. Herein, we demonstrate that sialic acid-containing gangliosides, rather than glycoproteins, were utilized by NDV as receptors to initiate the endocytic entry of NDV into HD11 cells. The binding of NDV to gangliosides induced the activation of a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, Src, leading to the phosphorylation of caveolin-1 (Cav1) and dynamin-2 (Dyn2), which contributed to the endocytic entry of NDV. Moreover, an inoculation of cells with NDV-induced actin cytoskeletal rearrangement through Src to facilitate NDV entry via endocytosis and direct fusion with the plasma membrane. Subsequently, unique members of the Rho GTPases family, RhoA and Cdc42, were activated by NDV in a Src-dependent manner. Further analyses revealed that RhoA and Cdc42 regulated the activities of specific effectors, cofilin and myosin regulatory light chain 2, responsible for actin cytoskeleton rearrangement, through diverse intracellular signaling cascades. Taken together, our results suggest that an inoculation of NDV-induced Src-mediated cellular activation by binding to ganglioside receptors. This process orchestrated NDV endocytic entry by modulating the activities of caveolae-associated Cav1 and Dyn2, as well as specific Rho GTPases and downstream effectors.

IMPORTANCE

In general, it is known that the paramyxovirus gains access to host cells through direct penetration at the plasma membrane; however, emerging evidence suggests more complex entry mechanisms for paramyxoviruses. The endocytic entry of Newcastle disease virus (NDV), a representative member of the paramyxovirus family, into multiple types of cells has been recently reported. Herein, we demonstrate the binding of NDV to induce ganglioside-activated Src signaling, which is responsible for the endocytic entry of NDV through caveolae-mediated endocytosis. This process involved Src-dependent activation of the caveolae-associated Cav1 and Dyn2, as well as specific Rho GTPase and downstream effectors, thereby orchestrating the endocytic entry process of NDV. Our findings uncover a novel molecular mechanism of endocytic entry of NDV into host cells and provide novel insight into paramyxovirus mechanisms of entry.

KEYWORDS: Newcastle disease virus, gangliosides, Src, virus entry

INTRODUCTION

Newcastle disease virus (NDV), designated as avian orthoavulavirus 1, is a representative member of the Paramyxoviridae family, which consists of enveloped viruses with a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome (1). NDV is a ubiquitous pathogen of bird species that represents a tremendous economic burden to the poultry industry (2). Despite decades of research into the pathogenesis of NDV, the host factors involved in the life cycle of NDV, especially the initial entry process into host cells, remain poorly understood.

The first and most essential step in the life cycle of the virus is entry into host cells. Enveloped viruses have evolved diverse strategies to enter target cells, including the direct fusion of the viral envelope with the cellular plasma membrane (PM) and receptor-mediated endocytosis (3). The best-characterized cell entry mechanism of paramyxoviruses is via direct membrane fusion triggered at the cell surface in a receptor-dependent and pH-independent manner, with both the viral attachment protein and fusion protein implicated in this process (4, 5). Notably, increasing findings have demonstrated that paramyxoviruses can also hijack a variety of cellular endocytic machinery for host cell entry and subsequently initiate viral-cell membrane fusion in an intracellular compartment, indicating a more complex mechanism of cell entry for paramyxoviruses (6–8). Recent studies have also found evidence supporting NDV endocytic entry. Moreover, caveolae-mediated endocytosis (CavME) has been found to be utilized by NDV for entry into multiple types of host cells (9–11). Our recent discovery revealed that this endocytic machinery was implicated in the entry of NDV into chicken macrophages, one of the main target cells for NDV (9–12).

CavME is a ligand-triggered event that involves complex signaling cascades and also represents a cellular intrinsic mechanism that generally involves the uptake of membrane-associated components, extracellular ligands, and bacterial toxins (13, 14). The binding of the ligand to the receptor within caveolae induces receptor clustering and in turn leads to the activation of phosphorylation cascades, which are initiated by Src family non-receptor tyrosine kinases. Subsequently, activated Src mediates the phosphorylation of caveolin-1 (Cav1) and dynamin-2 (Dyn2), which are further responsible for the formation and fission of caveolae from the PM (15). Moreover, phosphorylation-dependent rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton may be mediated by Src and is also an essential requirement for CavME, albeit the mechanisms of actin rearrangement upon activation of CavME remain poorly understood (16). In addition, although a growing number of studies have shown that CavME can be utilized by some viruses for cell entry (17–19), little is known about the detailed mechanism of the virus-induced activation of CavME. Limited information from Simian virus 40 (SV40) demonstrates that the binding of SV40 to cell surface gangliosides enriched in caveolae can induce tyrosine kinase-mediated signaling and eventually contribute to virus endocytosis via CavME (20). For NDV, sialic acid-containing gangliosides, which are the major component of the caveolae, have been identified as the attachment receptor (21). Although NDV can enter chicken macrophages via CavME, the contribution of gangliosides to NDV-induced activation of intracellular signaling cascades is still unknown. This signaling cascade led to the induction of endocytosis and the production of specific cellular factors involved in this process, which have not yet been studied in detail.

In the present study, we sought to systematically elucidate the molecular mechanism by which NDV enters into the chicken macrophages via CavME. We found that the endocytic entry of NDV into chicken macrophages depends on sialic acid-containing gangliosides, rather than glycoproteins. The binding of NDV to gangliosides resulted in the activation of Src and subsequent phosphorylation of downstream molecules, Cav1 and Dyn2, which were found to contribute to NDV endocytosis via caveolae. Additionally, our results demonstrated that actin cytoskeletal rearrangement was induced by NDV via Src and was involved in NDV entry via endocytosis, as well as direct fusion with the PM. Further analysis revealed that Src-mediated activation of unique Rho GTPases with the engagement of specific effectors was responsible for actin cytoskeletal rearrangement and NDV entry into host cells.

RESULTS

NDV endocytic entry into HD11 cells depends on the linkage of sialic acid to gangliosides

Recently, we reported that except for direct fusion of viral envelope with the PM at the cell surface, NDV can also enter HD11 cells via CavME (12). In the present study, the contribution of sialic acid linked to glycoproteins and gangliosides, which have been identified as NDV receptors involved in the entry of NDV, was investigated because CavME is a receptor-mediated pathway. First, to distinguish the entry pathways mediated by direct fusion of viral envelope with the PM and endocytosis, a quantitative internalization assay was performed by using NDV labeled with a lipophilic green fluorescent dye, DiOC (3,3′-dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate), which can be quenched by the membrane-impermeable dye trypan blue (22, 23). The confocal fluorescence microscopy demonstrated that both diffusion of green DiOC fluorescence throughout the PM and green DiOC fluorescence spots in the cytoplasm were observed, indicating the direct fusion of the viral envelope with the PM at the cell surface and the endocytosed virus, respectively. When treated with trypan blue, the green DiOC fluorescence in the PM was invisible, while green DiOC fluorescence spots still could be observed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1A, left panel). In addition, the mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) of DiOC fluorescence were about 76% of the fluorescence, which was resistant to trypan blue treatment (entry via endocytosis) and about 24% of the fluorescence, which could be quenched by trypan blue (fusion with PM). Consistent results were obtained by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 1A, right panel). These results indicated that the majority of NDV particles entered HD11 cells through the endocytic pathway. Subsequently, HD11 cells were treated with Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase (NA) to cleave sialic acid from the cell surface. The adsorption and internalization assays were performed to evaluate the effects of sialic acid in NDV entry. As shown in Fig. 1B, a significant reduction in the MFI of DiOC fluorescence was observed on the NA-treated cell surface compared to those of control cells in the adsorption assay. In the internalization assay, both the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and the endocytic entry of NDV were significantly reduced in NA-treated cells compared to control cells (Fig. 1C).

Fig 1.

Sialic acid-containing glycoprotein receptors are responsible for NDV entry into HD11 cells via direct fusion with the PM. (A) NDV entered HD11 cells mainly through the endocytic pathway. The internalization assay in HD11 cells was performed with DiOC-labeled NDV. After treatment with trypan blue, confocal microscopy was used to detect the fluorescence of DiOC-labeled NDV (left). Besides, the mean fluorescence intensities of DiOC-labeled NDV that was resistant to and quenched by trypan blue were quantified by confocal microscopy and flow cytometry analysis, respectively (right). (B and C) Treatment with NA reduced the adsorption and internalization of NDV. HD11 cells were treated with NA or PBS and then subjected to adsorption (B) and internalization (C) assays followed by treatment with trypan blue. Flow cytometry was used to determine the MFI of DiOC-labeled NDV. The MFI in reagent-treated cells was calculated relative to that of control cells (×100%). (D) Treatment with MAL and SNA reduced the adsorption and internalization of NDV. HD11 cells were treated with MAL, SNA, or PBS and then subjected to adsorption and internalization assays followed by treatment with trypan blue. Confocal microscopy was used to visualize the cells. (E and F) Treatment with trypsin and chymotrypsin reduced NDV adsorption to cells and the direct fusion of NDV with the PM without affecting the endocytic entry of NDV. HD11 cells were treated with trypsin or PBS and then subjected to adsorption (E) and internalization (F) assays followed by treatment with trypan blue. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV. the bars represent means ± standard deviations (SD) of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

To further determine whether specific sialic acid linkage is required for NDV entry, HD11 cells were pre-incubated with Maackia amurensis lectin (MAL) and Sambucus nigra lectin (SNA), which preferentially bind to α 2,3- and 2,6-linked sialic acid, respectively. Next, DiOC-labelled NDV was adsorbed onto HD11 cells, and the fluorescence was investigated by confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 1D, the pre-incubation of HD11 cells with both MAL and SNA significantly inhibited NDV adsorption. In the subsequent internalization assay, the cells were treated with trypan blue following the internalization of NDV. The results showed that the direct fusion of the viral envelope with the PM and endocytic entry of NDV in both MAL- and SNA-treated cells were significantly reduced compared to that of the control cells (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these results indicate that both 2, 3-linked and 2,6-linked sialic acid are required for NDV adsorption and further contribute to virus cell entry.

The involvement of sialic acid linked to glycoproteins and gangliosides during the entry process of various viruses, including NDV, has been reported (23, 24). In this study, to examine the contribution of glycoproteins in the entry of NDV into HD11 cells, chymotrypsin and trypsin, which catalyze the hydrolysis of peptide bonds in the polypeptide chains, were used to treat HD11 cells (25). The results demonstrated that HD11 cells treated with chymotrypsin and trypsin significantly reduced NDV adsorption (Fig. 1E) and the direct fusion of the viral envelope with the PM (Fig. 1F). In contrast, NDV endocytic entry was not significantly affected (Fig. 1F). To further examine the role of gangliosides in NDV entry, HD11 cells were treated with N-[(1R,2R)−2-hydroxy-1-(4-morpholinylmethyl)−2-phenylethyl]-decanamide, monohydrochloride (PDMP), an inhibitor of glucosylceramide synthase, which could reduce the expression of glycosphingolipids on the cell membrane (26, 27). The effect of PDMP treatment was evaluated using the internalization of cholera toxin subunit B (CTB), which was internalized via CavME using gangliosides as an endocytic receptor (15, 28). As shown in Fig. 2A and B, the adsorption and internalization of CTB in PDMP-treated cells were significantly lower than those in the control cells, indicating the reduced level of gangliosides at the cell surface. Further results demonstrated that the adsorption, direct fusion of the viral envelope with the PM, and endocytic entry of NDV were all reduced due to PDMP treatment (Fig. 2C and D). Notably, the endocytosis of NDV (55% detectable) was affected more obviously by PDMP than the fusion of the viral envelope with the PM (81% detectable). These findings suggest that sialic acid-containing glycoproteins are responsible for the direct fusion of NDV with the PM, whereas sialic acid-containing gangliosides are associated with NDV entry into host cells by direct fusion with the PM and especially endocytosis.

Fig 2.

Sialic acid-containing gangliosides as receptors for NDV endocytic entry into HD11 cells. (A and B) Treatment with PDMP reduced the adsorption and internalization of CTB. HD11 cells were treated with PDMP or ethanol and then subjected to adsorption and internalization assays of CTB. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the fluorescence of CTB. (C and D) Treatment with PDMP reduced adsorption, the direct fusion of NDV with the PM, and endocytosis of NDV. HD11 cells were treated with PDMP or ethanol and then subjected to adsorption (C) and internalization (D) assays followed by treatment with trypan blue. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV. (E) The presence of gangliosides in HD11 cells and colocalization of gangliosides with NDV. HD11 cells were inoculated with NDV, and then fixed and incubated with anti-GM1 antibody, anti-GD1a antibody, anti-GT1b antibody, and chicken anti-NDV antibody, respectively. The cells were visualized by confocal microscopy. (F and G) Exogenous GM1 and GD1a gangliosides blocked the adsorption and internalization of NDV. DiOC labelled NDV were pre-incubated with GM1, GD1a or DMSO. Adsorption (F) and internalization (G) assays of NDV followed by treatment with trypan blue were performed. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV. The bars represent means ± SD of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

Next, we sought to further investigate the role of different ganglioside subclasses in the entry of NDV into HD11 cells. To this end, the presence of representative monosialogangliosides (GM1), disialogangliosides (GD1a), and trisialogangliosides (GT1b) in HD11 cells and the colocalization of these gangliosides with NDV were examined by confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 2E, endogenous GM1 and GD1a were identified on the surface of HD11 cells, and the colocalization of NDV with GM1 and GD1a was observed. In contrast, endogenous GT1b was not detected in HD11 cells. Moreover, the ability of exogenous GM1 and GD1a to inhibit the entry of NDV was evaluated. As expected, blocking NDV with both GM1 and GD1a reduced NDV adsorption (Fig. 2F). Correspondingly, the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and the endocytic entry of NDV in HD11 cells were significantly inhibited by a blockade of NDV with GM1 and GD1a (Fig. 2G). Taken together, these findings demonstrate the role of different gangliosides, which contain α2, 3- and α2, 6-sialic acid for the entry of NDV into HD11 cells via direct fusion with the PM and endocytosis.

Src activation by NDV through binding to gangliosides contributes to NDV host cell entry

Since activation of the tyrosine kinase signaling cascade is a hallmark of CavME (16), the present study adopted Genistein, a protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor (29), to treat HD11 cells. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, no obvious effect on NDV adsorption was observed, whereas the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and endocytic entry of NDV were significantly reduced following treatment with Genistein, indicating the involvement of protein tyrosine kinase in the entry of NDV into HD11 cells. Furthermore, it is obvious that the non-receptor tyrosine kinase, Src, is a critical regulator in the initiation of tyrosine phosphorylation cascade in CavME, in which Src activation via the autophosphorylation of tyrosine on 416 (Y416) is an early and essential step (30). To investigate whether Src is implicated in the NDV entry process, the level of Y416 phosphorylation of Src was examined via Western blotting. The results showed that at 15- and 30-min post-inoculation (mpi), the level of Y416 phosphorylation of Src in NDV-inoculated cells was significantly increased when compared with the mock-inoculated cells (Fig. 3C). Moreover, after inoculation with different doses of NDV (multiplicity of infection, MOI of 5 and 10), increased Y416 phosphorylation of Src was observed in HD11 cells and primary chicken macrophages, rather than DF-1 cells (Fig. 3D). These findings suggest that the activation of Src should be exclusively involved in NDV entry into chicken macrophages, independent of the dose of NDV.

Fig 3.

NDV induces tyrosine phosphorylation of Src for entry into HD11 cells. (A and B) Treatment with Genistein inhibited internalization of NDV. HD11 cells were treated with Genistein or DMSO and then subjected to adsorption (A) and internalization (B) assays. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV. (C) Y416 phosphorylation of Src was induced by NDV during the entry process. HD11 cells were either inoculated with NDV at an MOI of 10 or mock inoculated. At each of the indicated time point, cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against p-Src (Tyr416) and Src, respectively. GAPDH was used as a control. The relative intensity of p-Src (Tyr416) and Src were normalized to GAPDH. (D) Y416 phosphorylation of Src was induced by NDV in HD11 cells and primary chicken macrophage, rather than DF-1 cells. HD11 cells, primary chicken macrophage and DF-1 cells were either inoculated with NDV at an MOI of 5 and 10 or mock inoculated. At 30 mpi with NDV, the levels of p-Src (Tyr416) and Src by Western blotting as described in Fig. 3C. (E–H) Treatment with Src inhibitors inhibited the internalization of NDV. HD11 cells were pretreated with Saracatinib (E and F) and Dasatinib (G and H), or mock-treated with DMSO, after which adsorption and internalization assays were performed. (I) Treatment with Saracatinib inhibited NDV-induced phosphorylation of Src. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or Saracatinib. The cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At 30 mpi, the levels of p-Src and Src were determined by Western blotting. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

To further verify the involvement of Src in NDV entry, two Src family kinase inhibitors, Saracatinib and Dasatinib (31), were used to treat HD11 cells, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3E, NDV adsorption was not significantly affected by the treatment of HD 11 cells with Saracatinib. In contrast, the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and endocytic entry of NDV were observed to be negatively affected (Fig. 3F). Similar effects were also observed following treatment with another inhibitor, Dasatinib (Fig. 3G and H). Furthermore, the Western blotting results demonstrated that NDV inoculation-induced Y416 phosphorylation of Src was significantly reduced when the cells were treated with Saracatinib (Fig. 3I).

To further confirm the effect of Y416 phosphorylation of Src on NDV entry into HD11 cells, plasmids expressing blue fluorescent protein (BFP)-tagged wild-type (WT) Src and phospho-defective (PD) mutant Src Y416F were transfected into HD11 cells, respectively (32). Next, an internalization assay using DiOC-labeled NDV was performed. As shown in Fig. 4A, there was an obvious reduction in the MFI of NDV quenched by trypan blue in Src Y416F-overexpressing cells (65% detectable). Moreover, the MFI of NDV resistant to trypan blue in cells overexpressing Src Y416F (45% detectable) was significantly lower than that of cells overexpressing WT Src (Fig. 4A). These data indicate that both the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and the endocytic entry of NDV are associated with the Y416 phosphorylation of Src. In addition, small interfering RNA (siRNA), which showed the efficiency of siRNA-mediated knockdown of Src, was used to knockdown the expression of Src (Fig. 4B). The adsorption and internalization assays demonstrated that knockdown of Src had no effect on the adsorption of NDV (Fig. 4C) but significantly reduced the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and the endocytic entry of NDV (Fig. 4D).

Fig 4.

NDV-activated Y416 phosphorylation of Src through binding to gangliosides is involved in the entry of NDV into HD11 cells. (A) Overexpression of a Src phospho-defective (PD) mutant reduced the internalization of NDV. HD11 cells transfected with the BFP-tagged WT Src or PD mutant Src Y416F were inoculated with DiOC-labelled NDV. Then the cells were collected, fixed and treated with trypan blue. Flow cytometry was used to determine the MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV in BFP-positive cells. (B) Knockdown of Src by siRNA. HD11 cells were transfected with siRNA targeting Src (siSrc) or a control siRNA (siNC). Western blotting was used to determine the effect of siRNA knockdown on Src expression. (C and D) Knockdown of Src inhibited the entry of NDV. After transfection with siRNA, the adsorption (C) and internalization (D) assays were performed. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV. (E) Treatment with PDMP inhibited the NDV-induced phosphorylation of Src. HD11 cells were pretreated with either ethanol or PDMP. The cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. Western blotting was used to determine the levels of p-Src and Src at 30 mpi with NDV. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

The results of the present study demonstrated that gangliosides were involved in the entry of NDV into HD11 cells (Fig. 2F and G). It was further reported that gangliosides could induce the phosphorylation of Src, which eventually leads to Src kinase activation (33). Therefore, we next examined whether gangliosides were involved in NDV-induced Y416 phosphorylation of Src. HD11 cells were pretreated with PDMP to reduce gangliosides on the cell surface, and the level of Y416 phosphorylation of Src during entry of NDV was determined by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 4E, PDMP treatment significantly reduced the level of Src Y416 phosphorylation induced by NDV inoculation. These results indicate that NDV activates Src tyrosine kinase by binding to gangliosides, which subsequently contribute to NDV entry.

Src-mediated phosphorylation of both Cav1 and Dyn2 is required for NDV endocytic entry

Activation of Src kinase and the subsequent tyrosine phosphorylation of Cav1 and Dyn2 mediated by Src are essential steps in the CavME cascade (16). Cav1, the principal scaffolding protein in caveolae, is the primary substrate of Src. Moreover, Cav1 phosphorylation on tyrosine 14 (Y14) induced by Src is indispensable for the CavME (34). Herein, we first examined the level of Cav1 phosphorylation during NDV entry into cells. An induction of phosphorylated Cav1 was observed by inoculating cells with NDV at 15 and 30 mpi (Fig. 5A), suggesting a contribution of phosphorylated Cav1 in NDV entry. To further explore whether Y14 phosphorylation of Cav1 is implicated in the endocytic entry of NDV, HD11 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding BFP-tagged WT Cav1 and PD mutant Cav1 Y14F, respectively. Next, an internalization assay using DiOC-labeled NDV was performed. As shown in Fig. 5B, no significant difference in the direct fusion of NDV with the PM was observed between cells overexpressing WT Cav1 and Cav1 Y14F. In contrast, the endocytic entry of NDV was reduced in cells overexpressing Cav1 Y14F compared to those overexpressing WT Cav1. These data suggested that Y14 phosphorylation of Cav1 was involved in the entry of NDV via endocytosis. Finally, HD11 cells were treated with Saracatinib followed by an inoculation with NDV. The Western blotting results showed that an increase in Cav1 phosphorylation induced by NDV was significantly inhibited by the treatment of cells with Saracatinib (Fig. 5C). This indicated that Cav1 phosphorylation induced by NDV was Src kinase dependent.

Fig 5.

Phosphorylation of Cav1 and Dyn2 induced by NDV via Src contributes to endocytic entry. (A) Phosphorylation of Cav1 was induced by NDV during the viral entry process. HD11 cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At each of the indicated time point, Western blotting using antibody against Cav1 was used to analyze the cell lysates. In addition, the cell lysates were precipitated with mouse anti-phospho-tyrosine antibody or normal mouse IgG as the isotype control antibody. Western blotting using an anti-Cav1 antibody was used to detect the precipitated samples. GAPDH was used as a control. (B) Overexpression of a Cav1 PD mutant reduced the level of NDV internalization. HD11 cells transfected with the BFP-tagged WT Cav1 or PD mutant Cav1 Y14F were inoculated with DiOC-labelled NDV. The internalization assay was performed as described in Fig. 4A. (C) Treatment with the Src inhibitor, Saracatinib, inhibited NDV-induced Cav1 phosphorylation. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or Saracatinib and then inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. Western blotting was used to determine the levels of p-Cav1 and Cav1 at 30 mpi with NDV as described in Fig. 5A. (D) Dyn2 phosphorylation was induced by NDV during the entry process. Detection of Dyn2 and phosphorylated Dyn2 in NDV-inoculated cells was performed with an anti-Dyn2 antibody and an anti-phospho-tyrosine antibody as described in Fig. 5A. (E) Overexpression of a Dyn2 PD mutant reduced NDV internalization. The internalization assay in HD11 cells transfected with the BFP-tagged WT Dyn2 or PD mutant Dyn2 Y231/597F was performed as described in Fig. 4A. (F) Treatment with the Src inhibitor, Saracatinib, inhibited NDV-induced phosphorylation of Dyn2. HD11 cells were treated with Saracatinib and inoculated with NDV as described in Fig. 5C. Western blotting was used to determine the levels of p-Dyn2 and Dyn2 at 30 mpi with NDV as described in Fig. 5A. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

Another substrate of Src critical for the regulation of CavME is Dyn2, which is phosphorylated on tyrosine 231 and 597 (Y231 and Y597) by Src and is responsible for the fission of caveolae from the PM (34). Thus, we next investigated whether Dyn2 phosphorylation plays a functional role in the endocytic entry of NDV. The Western blotting results in this study showed an increased level of phosphorylated Dyn2 in NDV-inoculated cells, especially at 15 and 30 mpi (Fig. 5D). To further investigate whether Dyn2 phosphorylation, which is related to the two tyrosine residues, Y231 and Y597, is involved in NDV endocytic entry, HD11 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding BFP-tagged WT Dyn2 and PD mutant Dyn2 Y231/597F, respectively. Similar results to the Cav1 were proved by an internalization assay using DiOC-labeled NDV, which showed that the direct fusion of NDV with the PM was not affected by the overexpression of Dyn2 Y231/597F, while a reduction in the endocytic entry of NDV was observed in cells overexpressing Dyn2 Y231/597F (Fig. 5E). These data further suggested that the phosphorylation of Dyn2 on Y231 and Y597 was required for the endocytic entry of NDV into cells. In addition, the phosphorylation of Dyn2 induced by an NDV inoculation was significantly inhibited by treatment with Saracatinib (Fig. 5F), indicating that NDV-induced phosphorylation of Dyn2 is Src kinase-dependent. Taken together, these findings indicate that NDV induces the tyrosine phosphorylation of Cav1 and Dyn2 via the activation of Src tyrosine kinase, which ultimately contributes to the endocytic entry of NDV into HD11 cells.

Actin cytoskeletal rearrangement induced by NDV via Src is involved in NDV entry via endocytosis and direct fusion with the PM

Although the actin cytoskeleton has been implicated in the process of CavME, the actual function of this cellular component in the entry of NDV remains poorly understood (15). In this study, confocal microscopy was used to examine whether the dynamic rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton was induced by NDV during entry into cells. NDV was added to the HD11 cells at 4°C to synchronize infection, and the cells were transferred to 37°C to initiate entry. Consistent with previous reports (35), no obvious actin stress fibers were observed in the mock-infected HD11 cells, whereas F-actin was found to be generally distributed within the cytoplasm, especially in the cortical region of the cells just beneath the PM (Fig. 6A). After the cells were inoculated with NDV, the dynamic rearrangement of F-actin was observed. Specifically, a dramatic decrease in F-actin in the cortical region was observed since 15 mpi with NDV and some F-actin bundles generated by F-actin polymerization appeared in the cytoplasmic regions. Subsequently, cortical F-actin became invisible, and a large number of F-actin bundles accumulated in the cytoplasm at 30 mpi. When the entry process of NDV was accomplished at 60 mpi (12), the distribution of F-actin returned to its normal pattern. The colocalization of NDV and F-actin was observed during the entry process, especially at 15 and 30 mpi (Fig. 6A). No filopodia and lamellipodia were observed during the NDV entry process. Given that dramatic changes in the actin cytoskeleton are known to be regulated by Src, which was activated by NDV, we further examined the potential roles of Src in the dynamic rearrangement of F-actin induced by NDV. As shown in Fig. 6A, the F-actin rearrangement induced by NDV was clearly inhibited by treatment with a Src inhibitor, Saracatinib. To further assess the straight impact of Src on F-actin rearrangement, YEEI peptide, a Src activator, was used to treat HD11 cells. As expected, obviously increased Y416 phosphorylation of Src and rearrangement of F-actin were observed upon inoculation of the YEEI peptide (Fig. 6B and C). In contrast, the knockdown of Src showed a significant inhibitory effect on the dynamic rearrangement of F-actin induced by NDV (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these data indicate that NDV can induce a dynamic rearrangement of F-actin during the entry process in a Src-dependent manner.

Fig 6.

NDV induces rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton via Src. (A) Treatment with the Src inhibitor, Saracatinib, inhibited NDV-induced actin cytoskeletal rearrangement. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or the Src inhibitor, Saracatinib. Then the cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At the indicated time points, the cells were fixed and permeabilized, and F-actin was stained with Phalloidin-iFluor 594 reagent (red). After staining with DAPI (blue), the cells were observed by confocal microscopy. (B–D) Src directly involved in the rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton induced by NDV. (B) Phosphorylation of Src was induced by inoculation of a Src activator, YEEI peptide. HD11 cells were inoculated with YEEI peptide at 37℃ for the indicated time points, the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using antibody against p-Src and Src. (C) Inoculation of YEEI peptide induced rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton. HD11 cells were inoculated with YEEI peptide at 37°C for the indicated time points, then the cells were fixed, stained with Phalloidin-iFluor 594 and observed by confocal microscopy. (D) Knockdown of Src inhibited the NDV-induced rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton. After transfection with siRNA, HD11 cells were inoculated with NDV and the dynamic of F-actin was observed by confocal microscopy as described above. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

Furthermore, to investigate whether the dynamic rearrangement of F-actin regulates NDV entry into cells, the effects of two inhibitors of actin dynamics, Cytochalasin D and Jasplakinolide, on NDV entry were determined, respectively. As shown in Fig. 7A and B, treatment with Cytochalasin D significantly inhibited the direct fusion with the PM and endocytic entry of NDV but had no effect on NDV adsorption. Similar results were also obtained following treatment with Jasplakinolide (Fig. 7C and D). It has previously been reported that actin cytoskeletal rearrangement is required for virus-mediated fusion with the cellular PM (36, 37). Hence, our results suggest that the dynamic rearrangement of F-actin induced by an inoculation of NDV via Src not only contributes to the endocytic entry of NDV but also involves in the direct fusion of the viral envelope with the PM.

Fig 7.

Rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton is involved in the NDV entry process via both endocytosis and direct fusion with the PM. Treatment with the actin dynamics inhibitors, Cytochalasin D (A and B) and Jasplakinolide (C and D), reduced NDV internalization. HD11 cells were pretreated with Cytochalasin D and Jasplakinolide or mock-treated with DMSO. Next, adsorption and internalization assays were performed. The MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV was analyzed by flow cytometry. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

Phosphorylation of LIMK1/cofilin is induced by NDV via Src in a PI3K/AKT-Rac1-PAK1 cascade-independent manner

Previous studies have shown that Src-mediated actin rearrangement is dependent on the downstream activation of Rho-family GTPases, including Ras homolog gene family member A (RhoA), Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1), and cell division cycle 42 (Cdc42), as well as the engagement of specific effectors (38–40). One of the terminal effectors of Rho GTPases signaling cascades is the F-actin severing protein, cofilin (CFN), a ubiquitous actin-binding protein that is responsible for the effective depolymerization of actin filaments. Rho GTPases can activate the LIM Domain Kinase 1 (LIMK1), which in turn increases the CFN phosphorylation of serine residue (S) at position 3, leading to inactivation of actin-depolymerizing activity of CFN and polymerization of F-actin (41–43). To identify the effect of CFN on the NDV entry of cells, the phosphorylation status of CFN was examined during the NDV entry process. As shown in Fig. 8A, the level of CFN phosphorylation was increased in cells inoculated with NDV both at 15 and 30 mpi. Correspondingly, the level of LIMK1 phosphorylation, the upstream regulator of CFN, was also increased at 15 and 30 mpi. These observations were in agreement with the dynamic changes of F-actin (Fig. 6A). To further address the role of CFN phosphorylation in NDV entry, HD11 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing BFP-tagged WT CFN and PD mutant CFN S3A, respectively. An internalization assay using DiOC-labeled NDV was performed. As shown in Fig. 8B, both the direct fusion with the PM and the endocytosis of NDV in cells overexpressing CFN S3A were significantly lower than those in cells overexpressing WT CFN. Furthermore, treatment of cells with Src inhibitor, Saracatinib, inhibited NDV-induced LIMK1 and CFN phosphorylation (Fig. 8C). These results suggest that an inoculation of NDV resulted in LIMK1 activation and subsequent phosphorylation of CFN through Src, which contributed to both the direct fusion of viral envelope with the PM and the endocytic entry of NDV.

Fig 8.

Phosphorylation of LIMK1/CFN is induced by NDV via Src in a PI3K/AKT independent manner. (A) Inoculation of NDV induced LIMK1 and CFN phosphorylation during the entry process. HD11 cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At the indicated time points, the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against p-CFN (S3), CFN, p-LIMK1 (T508) and LIMK1, respectively. GAPDH was used as a control. (B) Overexpression of a PD mutant CFN reduced the internalization of NDV. HD11 cells transfected with the BFP-tagged WT CFN or PD mutant CFN S3A were inoculated with DiOC-labelled NDV. The internalization assay was performed as described in Fig. 4A. (C) Treatment with the Src inhibitor, Saracatinib, inhibited NDV-induced phosphorylation of LIMK1 and CFN. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or Saracatinib. Then the cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At 30 mpi with NDV, the levels of p-LIMK1 (T508), LIMK1, p-CFN (S3), and CFN were determined by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a control. (D) HD11 cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At the indicated time points, the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against p-Akt (S473) and Akt, respectively. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

LIMK1-mediated phosphorylation of CFN may be activated by the upstream Rac1-p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) signaling axis. In addition, Rac1 can be activated by phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3k)/protein kinase B (Akt), one of the downstream targets of Src (40, 41, 44). Thus, we examined the potential involvement of the PI3K/Akt-Rac1-PAK1 cascade in NDV-induced LIMK1-CFN phosphorylation. PI3K activity during NDV entry was measured by an analysis of the level of Akt phosphorylation, the downstream effector of PI3K. In line with our previous report, which demonstrated that inhibitor of PI3K showed no adverse effects on NDV entry (12), this study found that the level of S473 phosphorylation of Akt did not significantly change during NDV entry (Fig. 8D).

Moreover, the GTPase activity of Rac1, a key downstream effector of PI3K and Src, did not change significantly during entry (Fig. 9A). In addition, no obvious changes were observed in the level of PAK1 phosphorylation, a main downstream effector of Rac1, which mediates LIMK1 phosphorylation (Fig. 9B). As expected, NDV-induced LIMK1/CFN phosphorylation was not impaired by treatment of cells with NSC23766 and IPA-3, inhibitors of Rac1 and PAK1, respectively (Fig. 9C). Additionally, treatment with NSC23766 (Fig. 9D and E) and IPA-3 (Fig. 9F and G) had no effect on the adsorption, the direct fusion with the PM, and the endocytosis of NDV. In conclusion, these results suggest that NDV can induce LIMK1/CFN phosphorylation via Src, which is not mediated by the PI3K/Akt-Rac1-PAK1 cascade.

Fig 9.

PI3K/AKT downstream Rac1-PAK1 signaling axis is not activated and involved in NDV entry into HD11 cells. (A) GTPase activity of Rac1 was analyzed by using the Rac1 activation assay kit, followed by Western blotting using an anti-Rac1 antibody. The level of GTP-Rac1 was normalized to the total Rac1. (B) The levels of p-PAK1 (T423) and PAK1 were analyzed by Western blotting using corresponding antibodies. GAPDH was used as a control. (C–G) Treatment with the Rac1 and PAK1 inhibitor, NSC23766 and IPA-3, showed no effect on NDV-induced LIMK1/CFN phosphorylation and entry of NDV. (C) HD11 cells were pretreated with NSC23766, IPA-3, or DMSO. Then the cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. Western blotting was used to determine the levels of p-LIMK1 (T508), LIMK1, p-CFN (S3), and CFN at 30 mpi with NDV. GAPDH was used as a control. (D–G) Treatment with the NSC23766 and IPA-3 had no effect on the adsorption and internalization of NDV. HD11 cells were pretreated with NSC23766 (D and E), IPA-3 (F and G), after which NDV adsorption and internalization assays were performed. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

RhoA-ROCK1 signaling is activated by NDV through Src to modulate the phosphorylation of LIMK1/CFN and virus entry into cells

RhoA-Rho associated kinases 1 (ROCK1) is another well-documented signaling pathway implicated in the modulation of LIMK1/CFN phosphorylation and can be activated by Src (40, 45, 46). In the present study, we tested whether the Src-RhoA-ROCK1 axis was involved in NDV-induced LIMK1/CFN phosphorylation and NDV entry into host cells. The activation of ROCK1, an upstream kinase of LIMK1, was evaluated by the determination of the expression level of this protein during NDV entry (47). The Western blotting analysis revealed that the level of ROCK1 expression was significantly increased in cells at 15 and 30 mpi with NDV (Fig. 10A), indicating the activation of ROCK1 during NDV entry. Furthermore, the effects of ROCK1 on LIMK1/CFN phosphorylation and NDV entry were assessed by treatment with Y-27632, a ROCK1 inhibitor. In contrast to those of mock-treated cells, the marked increase of ROCK1 induced by NDV was impaired following treatment with Y-27632 (Fig. 10B). In addition, the phosphorylation of LIMK1 and CFN was also significantly inhibited by treatment with Y-27632 (Fig. 10C). Correspondingly, Y-27632 treatment significantly inhibited the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and endocytic entry of NDV without influencing viral adsorption (Fig. 10D and E). These results suggest that ROCK1 activation is required for NDV-induced LIMK1/CFN phosphorylation and NDV entry into host cells.

Fig 10.

ROCK1-LIMK1/CFN signaling is activated by NDV to modulate viral entry. (A) ROCK1 was activated by NDV during the entry process. HD11 cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At the indicated time points, the cells lysate were analyzed by Western blotting using antibody against ROCK1. GAPDH was used as a control. (B and C) Treatment with the ROCK1 inhibitor Y-27632 inhibited NDV-induced the activation of ROCK1, LIMK1 and CFN. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or Y-27632. The cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At 30 mpi with NDV, the levels of ROCK1 (B), p-LIMK1 (T508), LIMK1, p-CFN (S3), and CFN (C) were determined by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a control. (D and E) Treatment with the ROCK1 inhibitor, Y-27632, reduced NDV internalization. HD11 cells were pretreated with Y-27632 or mock-treated with DMSO, after which adsorption (D) and internalization (E) assays of NDV were performed. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

Since it has been established that ROCK1 is activated by binding the GTP-bound RhoA (45), we subsequently investigated the role of RhoA in NDV-induced ROCK1-LIMK1-CFN signaling and NDV entry. A Western blotting analysis showed that the level of GTP-bound RhoA was significantly increased in cells at 15 and 30 mpi with NDV (Fig. 11A), indicating that RhoA activation was induced by an inoculation of NDV. Furthermore, treatment with the RhoA inhibitor, Rhosin, significantly reduced NDV-induced RhoA activation (Fig. 11B), as well as ROCK1 expression and LIMK1 and CFN phosphorylation (Fig. 11C). In addition, this inhibitor had an inhibitory effect on the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and endocytic entry of NDV but not on virus adsorption (Fig. 11D and E). To further validate the regulatory role of RhoA on NDV entry, the cells were transfected with plasmids expressing BFP-tagged WT RhoA and dominant-negative (DN) mutant RhoA T19N, respectively, and the internalization assay using DiOC-labeled NDV was performed. As expected, overexpression of the DN mutant RhoA T19N resulted in significant decreases in the level of the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and endocytic entry of NDV (Fig. 11F). These data suggest that RhoA is responsible for the activation of NDV-induced ROCK1-LIMK1-CFN signaling and NDV entry. In addition, treatment with the Src inhibitor, Saracatinib, significantly impaired NDV-induced activation of RhoA and ROCK1 (Fig. 11G). Taken together, these findings suggest that NDV activates the RhoA-ROCK1-LIMK1-CFN signaling axis through Src to facilitate the entry of NDV via direct fusion with the PM and endocytosis (Fig. 11H).

Fig 11.

RhoA activated by NDV via Src is responsible for the entry of NDV into HD11 cells through ROCK1-LIMK1/CFN signaling. (A) RhoA was activated by NDV during the entry process. HD11 cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At the indicated time points, the cell lysates were harvested and the GTPase activity of RhoA was analyzed using a RhoA activation assay kit, followed by a Western blotting using anti-RhoA antibody. GAPDH was used as a control. (B and C) Treatment with the RhoA inhibitor, Rhosin, inhibited NDV-induced activation of RhoA, ROCK1, LIMK1, and CFN. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or Rhosin. The cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At 30 mpi with NDV, the levels of GTP-RhoA (B), ROCK1, p-LIMK1 (T508), LIMK1, p-CFN (S3), and CFN (C) were determined by a RhoA activation assay kit and Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a control. (D and E) The RhoA inhibitor, Rhosin, reduced NDV internalization. HD11 cells were pretreated with Rhosin or mock-treated with DMSO, after which NDV adsorption (D) and internalization (E) assays were performed. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV. (F) Overexpression of a dominant-negative (DN) mutant RhoA reduced the internalization of NDV. HD11 cells transfected with the BFP-tagged WT RhoA or DN mutant RhoA T19N were inoculated with DiOC-labelled NDV. The internalization assay was performed as described in Fig. 4A. (G) Treatment with the Src inhibitor, Saracatinib, inhibited NDV-induced activation of RhoA and ROCK1. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or Saracatinib. The cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At 30 mpi with NDV, the levels of GTP-RhoA and ROCK1 were determined by a RhoA activation assay kit and Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a control. (H) Schematic of NDV-activated RhoA-ROCK1-LIMK1-CFN signaling axis during entry into HD11 cells. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments. (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

Activation of MLC by Src-mediated RhoA-ROCK1 signaling cascade contributes to NDV entry into cells

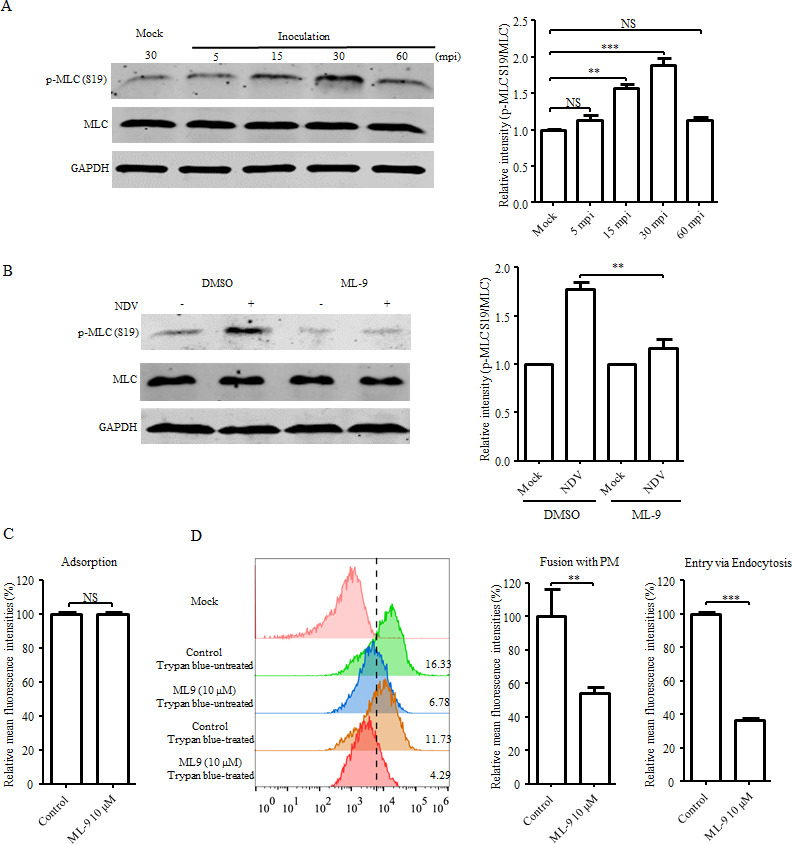

Apart from the regulatory effects on LIMK1/CFN, the RhoA-ROCK1 signaling cascade also promotes the formation of contractile actomyosin bundles through its effects on the phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain 2 (MLC) at Ser19, thereby modulating actin cytoskeleton organization and cellular contraction (45, 48). Therefore, MLC may represent a potential candidate for mediating a rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton and NDV entry. We found that the phosphorylation of MLC was obviously enhanced in cells at 15 and 30 mpi with NDV (Fig. 12A), suggesting that MLC activation was induced by NDV inoculation. Treatment with ML-9, an inhibitor of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), which mediates MLC phosphorylation, dramatically inhibited NDV-induced phosphorylation of MLC (Fig. 12B). Further results showed that the adsorption of NDV was not affected upon treatment with ML-9 (Fig. 12C), while the levels of the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and endocytic entry of NDV were dramatically reduced (Fig. 12D).

Fig 12.

MLC is activated by NDV and contributes to the entry of NDV into HD11 cells. (A) MLC phosphorylation was induced by NDV during the entry process. HD11 cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At the indicated time points, the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against p-MLC (S19) and MLC, respectively. GAPDH was used as a control. (B) Treatment with the MLCK inhibitor, ML-9, inhibited NDV-induced phosphorylation of MLC. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or ML-9. The cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At 30 mpi with NDV, the levels of p-MLC (S19) and MLC were determined by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a control. (C and D) Treatment with the MLCK inhibitor, ML-9, reduced NDV internalization. HD11 cells were pretreated with ML-9 or mock-treated with DMSO, after which NDV adsorption (C) and internalization (D) assays were performed. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments. (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

To further confirm the role of MLC phosphorylation in NDV entry, the cells were transfected with plasmids expressing BFP-tagged WT MLC and PD mutant MLC S19A, respectively, and an internalization assay using DiOC-labeled NDV was performed. As shown in Fig. 13A, both levels of the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and endocytic entry of NDV in cells overexpressing the PD mutant MLC S19A were significantly reduced. Next, to verify the involvement of the Src-mediated RhoA-ROCK1 signaling cascade in the activation of MLC, the cells were treated with Src (Saracatinib), RhoA (Rhosin), or ROCK1 (Y-27632) inhibitors and MLC phosphorylation were analyzed by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 13B, MLC phosphorylation induced by an NDV inoculation was significantly inhibited by treatment with Saracatinib, Rhosin, and Y-27632. Moreover, the result of confocal microscopy demonstrated that the F-actin rearrangement induced by NDV was obviously inhibited by treatment with ML-9 (Fig. 13C). Taken together, these data suggest that activation of MLC is induced by an inoculation of NDV through the Src-mediated RhoA-ROCK1 signaling cascade and is involved in the rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton to facilitate NDV entry (Fig. 13D).

Fig 13.

MLC activation is mediated by NDV via Src-RhoA-ROCK1 signaling and facilitates virus entry through regulating dynamics of actin cytoskeleton. (A) Overexpression of a PD mutant MLC reduced the internalization of NDV. HD11 cells transfected with the BFP-tagged WT MLC or PD mutant MLC S19A were inoculated with DiOC-labelled NDV. The internalization assay was performed as described in Fig. 4A. (B) Treatment with Src inhibitor, Saracatinib, RhoA inhibitor, Rhosin, and ROCK1 inhibitor, Y-27632, inhibited NDV-induced activation of MLC. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or Saracatinib, Rhosin, and Y-27632. The cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At 30 mpi with NDV, the levels of p-MLC (S19) and MLC were determined by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a control. (C) Treatment with ML-9 inhibited NDV-induced rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or ML-9. Then the cells were inoculated with NDV. At 30 mpi, F-actin was stained and observed by confocal microscopy as described in Fig. 6A. (D) Schematic of NDV-activated RhoA-ROCK1-MLC signaling axis during entry into HD11 cells. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

The Src downstream Cdc42-PAK2-MLC signaling axis, rather than Cdc42-N-WASP-Arp2/3, is activated by inoculation of NDV to modulate viral entry

p21 activated kinase 2 (PAK2) is another prominent upstream regulator of MLC and has been implicated in actin cytoskeleton rearrangements and cell contractility through directly phosphorylating MLC (49–51). Moreover, PAK2 activity is regulated by Rac1 or Cdc42 (49). In the present study, Rac1 was found not to be activated during NDV entry (Fig. 9A). Therefore, we next sought to investigate whether the Cdc42-PAK2 signaling axis participates in NDV-induced activation of MLC and viral entry. Western blotting results showed that the level of PAK2 phosphorylation was elevated in cells at 15 and 30 mpi with NDV (Fig. 14A). Additionally, treatment with the PAK2 inhibitor, Staurosporine, resulted in both the reduction of NDV-induced PAK2 phosphorylation and NDV-induced phosphorylation of MLC (Fig. 14B and C). This finding indicated that NDV-induced MLC phosphorylation can be mediated through upstream PAK2. Moreover, no effect of Staurosporine was observed regarding NDV adsorption (Fig. 14D), whereas the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and endocytic entry of NDV were dramatically inhibited following Staurosporine treatment (Fig. 14E). To confirm the role of PAK2 in NDV entry, the cells were transfected with plasmids expressing the BFP-tagged WT PAK2 and PD mutant PAK2 T402A, respectively, and an internalization assay using DiOC-labeled NDV was performed. As shown in Fig. 14F, the overexpression of the PD mutant PAK2 T402A led to a significant reduction of both the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and NDV endocytic entry. These data indicate that NDV-induced activation of PAK2 promotes viral entry through mediating MLC phosphorylation.

Fig 14.

PAK2 phosphorylation induced by NDV is involved in MLC activation and viral entry. (A) PAK2 phosphorylation was induced by NDV during the viral entry process. HD11 cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At the indicated time points, the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against p-PAK2 (T402) and PAK2. GAPDH was used as a control. (B and C) Treatment with the PAK2 inhibitor, Staurosporine, inhibited NDV-induced phosphorylation of PAK2 and MLC. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or Staurosporine. The cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At 30 mpi with NDV, the levels of p-PAK2 (T402), PAK2 (B), p-MLC (S19) and MLC (C) were determined by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a control. (D and E) Treatment with the PAK2 inhibitor, Staurosporine, reduced the level of NDV internalization. HD11 cells were pretreated with Staurosporine or mock-treated with DMSO, after which NDV adsorption (D) and internalization (E) assays were performed. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV. (F) Overexpression of a PD mutant PAK2 reduced the internalization of NDV. HD11 cells transfected with the BFP-tagged WT PAK2 or PD mutant PAK2 T402A were inoculated with DiOC-labelled NDV. The internalization assay was performed as described in Fig. 4A. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

To further examine whether Cdc42, an upstream regulator of PAK2, is involved in the NDV-induced activation of PAK2 and MLC, Cdc42 GTPase activity during the entry of NDV was measured by Western blotting. The results showed that the Cdc42 GTPase activity was significantly increased in cells at 15 and 30 mpi with NDV (Fig. 15A), indicating that Cdc42 activation was induced by an inoculation of NDV. Furthermore, treatment with ML141, an inhibitor of Cdc42, reduced NDV-induced activation of Cdc42 (Fig. 15B) and the phosphorylation of PAK2 and MLC (Fig. 15C), which indicated that Cdc42 functions upstream of PAK2 and MLC. Moreover, the inhibition of Cdc42 by ML141 led to a significant reduction of the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and endocytic entry of NDV but had no effect on the adsorption of NDV (Fig. 15D and E). An additional internalization assay using DiOC-labeled NDV in cells overexpressing BFP-tagged WT Cdc42 and DN mutant Cdc42 T17N suggested that the direct fusion of NDV with the PM and endocytic entry of NDV into cells were impaired due to the overexpression of DN mutant Cdc42 T17N (Fig. 15F).

Fig 15.

Cdc42 is responsible for the activation of PAK2-MLC signaling and viral entry. (A) Cdc42 was activated by NDV during the viral entry process. HD11 cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At the indicated time points, the cell lysates were harvested and the GTPase activity of Cdc42 was analyzed using a Cdc42 activation assay kit followed by Western blotting using anti-Cdc42 antibody. GAPDH was used as a control. (B and C) Treatment with Cdc42 inhibitor ML141 inhibited NDV-induced activation of Cdc42, PAK2, and MLC. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or ML141. The cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At 30 mpi with NDV, the levels of GTP-Cdc42 (B), p-PAK2 (T402), PAK2, p-MLC (S19) and MLC (C) were determined by a Cdc42 activation assay kit and Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a control. (D and E) Treatment with the Cdc42 inhibitor, ML141, reduced the level of NDV internalization. HD11 cells were pretreated with ML141 or mock-treated with DMSO, after which NDV adsorption (D) and internalization (E) assays were performed. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the MFI of DiOC-labelled NDV. (F) Overexpression of a DN mutant Cdc42 reduced the internalization of NDV. HD11 cells transfected with the BFP-tagged WT Cdc42 or DN mutant Cdc42 T17N were inoculated with DiOC-labelled NDV. The internalization assay was performed as described in Fig. 4A. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

Significantly, NDV-induced activation of Cdc42 was inhibited by the treatment of cells with the Src inhibitor, Saracatinib (Fig. 16A). NDV-induced phosphorylation of PAK2 and MLC was also inhibited by the treatment of cells with Saracatinib (Fig. 16B). These results support the conclusion that the Src-mediated Cdc42-PAK2 signaling axis contributes to NDV-induced phosphorylation of MLC and viral entry. Additionally, Cdc42 regulates the assembly and organization of F-actin and is involved in the formation of filopodia through the Cdc42-N-WASP-Arp2/3 signaling pathway (39). Herein, we found that the adsorption, the direct fusion of NDV with the PM, and endocytic entry of NDV into cells remained unaffected upon treatment with both the N-WASP inhibitor, Wiskostatin (Fig. 16C and D) and Arp2/3 inhibitor, CK-636 (Fig. 16E and F). Since no filopodia were observed during the NDV entry process (Fig. 6A), these findings further indicate that the Cdc42-N-WASP-Arp2/3 signaling pathway is not required for NDV entry into host cells. These results suggest that NDV activates the Src downstream Cdc42-PAK2-MLC signaling axis, rather than Cdc42-N-WASP-Arp2/3, to modulate rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton and the entry of NDV (Fig. 16G).

Fig 16.

NDV activates Cdc42-PAK2-MLC signaling axis via Src, rather than Cdc42-N-WASP-Arp2/3, to promote viral entry. (A and B) Treatment with Src inhibitor, Saracatinib, inhibited NDV-induced activation of Cdc42, PAK2, and MLC. HD11 cells were pretreated with either DMSO or Saracatinib. The cells were inoculated or mock inoculated with NDV. At 30 mpi with NDV, the levels of GTP-Cdc42 (A), p-PAK2 (T402), PAK2, p-MLC (S19), and MLC (B) were determined with a Cdc42 activation assay kit and Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a control. (C and D) Treatment with the N-WASP inhibitor, Wiskostatin, and (E and F) Arp2/3 complex inhibitor, CK636, had no effect on the adsorption and internalization of NDV. HD11 cells were pretreated with Wiskostatin, CK-636 or mock-treated with DMSO, and NDV adsorption and internalization assays were performed as described above. (G) Schematic of NDV-activated Cdc42-PAK2-MLC signaling axis during entry into HD11 cells. The bars represent the means ± SD from three independent experiments (*P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; NS, no significant difference).

DISCUSSION

Most of the paramyxoviruses enter host cells in a sialic acid-dependent manner (23, 52, 53). For NDV, sialic acid-containing gangliosides and glycoproteins have been suggested as primary attachment receptors and second entry receptors, which mediate viral attachment and fusion of viral envelope with the PM at the cell surface, respectively (21). However, the implication of gangliosides and glycoproteins in the endocytic entry of NDV has not been completely elucidated. With the increased knowledge of viral entry, it has become evident that, in addition to contributing to virus adsorption, virus-attachment receptor interactions can also activate specific cellular signaling cascades to facilitate virus entry via the endocytic pathways (54, 55). Gangliosides, the attachment receptors of NDV, are the major components of the caveolae. This membrane component can be utilized by several viruses as receptors for the activation of signaling cascades, which eventually leads to the endocytosis of viruses via CavME (15, 17, 20, 56). Here, we revealed that sialic acid-containing glycoproteins were exclusively involved in the entry of NDV through the direct fusion with the PM, whereas sialic acid-containing gangliosides contributed to the entry of NDV via both endocytosis and the direct fusion with the PM. Conceivably, the interaction between NDV and glycoproteins receptors directly elicited the fusion of the virus envelope with the PM. In contrast, the binding of NDV to ganglioside receptors activated Src signaling to mediate the entry of NDV via CavME. Meanwhile, the rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton that occurred during the endocytic process should affect, to a certain extent, the direct fusion of the viral envelope with the PM, as previously reported (37, 44). This result can also explain our observation that though gangliosides-activated signaling was involved in the entry of NDV via both fusion with the PM and CavME, the endocytosis of NDV was more closely related to gangliosides. These findings provide more detailed information concerning the precise features of NDV receptors. Moreover, we found that apart from the gangliosides, GM1 and GD1a, which have been identified in HD11 cells, a variety of other gangliosides (e.g., GM2, GM3, GD1b, and GT1b) can be bound by NDV. This binding occurs because the pretreatment of NDV with these gangliosides can inhibit NDV endocytosis in HD11 cells (unpublished data). This is consistent with previous reports, which have shown that there is no specific pattern of gangliosides that interact with NDV (21, 56). Thus, wide NDV cell tropism and host range may be partially explained by the ability of gangliosides to induce endocytosis independent of specific proteinaceous receptors and the universal gangliosides’ recognition activity of NDV.

CavME, triggered by ligands located in caveolae, is critically dependent on the activation of Src tyrosine kinase signaling (16). Herein, we showed that gangliosides, rather than protein receptors, were required for endocytic entry of NDV in HD11 cells. We speculated that NDV likely acted as a multivalent ligand to cross-link gangliosides, which are located in caveolae through binding to the terminal sialic acid. The clustering of gangliosides provided energy to induce membrane curvature of caveolae, which in turn led to the recruitment and activation of Src tyrosine kinases on the cytosolic leaflet (15, 57, 58). Upon activation, the critical function of Src-mediated signaling has been proposed to be responsible for the fission and internalization of caveolar vesicles (16). We demonstrated here that phosphorylation of Cav1 (Y14) and Dyn2 (Y231 and Y597) and actin cytoskeletal rearrangement were induced by NDV in a Src-dependent manner and contributed to the endocytic entry of NDV. Combining previous reports (59–61), we proposed that phosphorylation of Cav1 and Dyn2 should be responsible for the invagination and fission of NDV-containing caveolar vesicles. Meanwhile, actin cytoskeletal rearrangement induced by NDV via Src should provide the necessary mechanical force to support the caveolae release (15, 62). In addition to the direct activation of downstream effectors to regulate actin rearrangement, activated Src can also mediate the phosphorylation and activation of a receptor tyrosine kinase, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Activated EGFR may further modulate the dynamics of actin networks through activating downstream effector molecules, such as PI3K/Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (40, 63). In this study, we demonstrated that the PI3K/Akt, one of the main downstream effectors of EGFR, was not activated during NDV endocytic entry. Notably, the phosphorylation levels of EGFR and another main downstream effector of EGFR, ERK (64), were not significantly altered during the endocytic entry of NDV (data not shown). These findings indicate that the actin rearrangement required for the endocytic entry of NDV is independent of EGFR-mediated signaling pathways and reinforces the critical regulatory roles of Src in the endocytic entry of NDV into HD11 cells.

The rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton is an essential requirement for endocytosis. It has been assumed that the pushing forces generated by actin polymerization and pulling (contractile) forces produced by the movement of myosin along actin filaments are involved in the invagination and scission of endocytic vesicles (65–67). Actin polymerization is primarily manipulated by three members of Rho GTPases, RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42, with the participation of Arp2/3 and CFN. Activation of Rac1 and Cdc42 drives the formation of branched actin polymerization via Arp2/3 to induce lamellipodia and filopodia, respectively. Moreover, RhoA and Rac1 trigger the inactivation of CFN via LIMK1, which in turn supports the actin polymerization (41, 68, 69). Our results revealed that the formation of lamellipodia and filopodia had not been observed, and Arp2/3 was found to be dispensable during the endocytic entry process of NDV, whereas CFN phosphorylation mediated by RhoA-ROCK1-LIMK1 rather than the Rac1-PAK1-LIMK1 signaling cascade was required. These findings suggested that actin polymerization mediated by CFN, rather than Arp2/3, is implicated in the endocytic entry of NDV through caveolae, as previously reported (70). Moreover, as another key effector of Rho GTPases, activation of myosin II by MLC induces the formation of contractile actomyosin bundles to generate force to support membrane invagination and vesicle scission (67, 71). Here, we showed that MLC phosphorylation was induced by NDV via both RhoA-ROCK-MLC and Cdc42-PAK2-MLC signaling cascades and directly involved in the rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton and the entry of NDV. Thus, NDV should induce actin polymerization and myosin II activation through specific signaling cascades, which eventually coordinate the endocytic entry of NDV. Notably, the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton is implicated in the fusion of the viral envelope with the cell PM as well (37, 44). Consistently, our results showed that except for the endocytic entry of NDV, the direct fusion of NDV with the cell PM is also affected by the rearrangement of F-actin induced by NDV via Src. Thus, the detailed mechanism by which the actin cytoskeleton regulates NDV-mediated fusion with the PM needs to be further elucidated.

Rho GTPases are activated by guanine-exchange factors (GEFs), which stimulate the exchange of GDP for GTP on the GTPase (38). A vast number of Rho GEFs have been described in mammals, which exhibit different degrees of specificity toward Rho GTPases (72). However, the exact molecular mechanism of GEFs’ activation and which GEFs regulate each of the Rho GTPase have not been established. In contrast, it has been found that GEFs can be activated through phosphorylation mediated by Src tyrosine kinase (40, 73–75). In the present study, we showed that RhoA and Cdc42, rather than Rac1, were specifically activated in a Src-dependent manner. Hence, it is reasonable to speculate that NDV-induced Src activation mediates the phosphorylation of unique members of Rho GEFs, which in turn activates specific Rho GTPase and downstream effectors to facilitate endocytic entry. Unlike mammals, the GEFs that regulate the activity of Rho GTPase have not been well identified in chickens. Therefore, uncovering the chicken GEF counterparts responsible for the regulated activation of Rho GTPase will be beneficial for clarification of this point.

To date, the entry of NDV strains into various cell types via distinct endocytic pathways has been reported. For instance, macropinocytosis and clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) were involved in the endocytic entry into the galline embryonic fibroblast cell line (DF-1) by the velogenic strains ZJ1 and F48E9 and into murine dendritic cells (DCs) by the velogenic strain Herts/33 (11, 12, 76), while CavME was responsible for the entry into HD11 and primary chicken macrophages by the velogenic strain F48E9 and into Hela and COS-7 cells by the lentogenic strain Clone 30 (10, 12). Herein, we further demonstrated that Src activation was induced in both HD11 and primary chicken macrophages after inoculation with different doses of NDV F48E9 (5 and 10 MOI). In contrast, activation of Src was not observed in NDV F48E9-inoculated DF-1 cells. The recognition of the sialic acid receptor by hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN) protein is the initial step during the NDV entry process. Two receptor-binding sites have been identified in NDV HN, in which E401, R416, Y526, and R516 were considered key residues for receptor binding (77, 78). The amino acid sequence alignment demonstrated that these four residues were conserved in nearly all NDV isolates including ZJ1, Herts/33, F48E9, and Clone 30 (data not shown), indicating the similar receptor-binding properties of these NDVs. The differential expression patterns of gangliosides in different cells and the involvement of different gangliosides in the entry of viruses via distinct endocytic pathways have been previously revealed (20, 79–81). Therefore, it is plausible that NDV may bind to gangliosides that are preferentially presented in HD11 cells (e.g., GM1 and GD1a) to activate Src-mediated CavME, while the interactions of NDV with gangliosides that are preferentially presented in DF-1 cells (e.g., GM2 and GM3) led to the entry of NDV through macropinocytosis and CME. Based on these findings, we postulate that the specific endocytic pathway utilized by NDVs for entry should be further determined by the type of gangliosides in target cells including other antigen-presenting cells like chicken DCs.

As summarized in Fig. 17, the findings in the present study provide novel insight into the molecular mechanism of NDV endocytic entry into host cells. By binding to sialic acid-containing gangliosides, rather than glycoprotein, NDV induced the activation of Src tyrosine kinase, leading to the activation of caveolae associated Cav1 and Dyn2, as well as the specific Rho GTPase and downstream effectors, orchestrating the endocytic entry process of NDV into HD11 cells. In addition, Src-mediated actin cytoskeletal rearrangement also contributes to the direct fusion of NDV with the cell PM. Our findings highlight the significance of Src in the regulation of endocytic entry of NDV into HD11 cells and broaden our understanding of the entry mechanisms of paramyxoviruses.

Fig 17.

Schematic of NDV entry pathways into HD11 cells. (A) NDV entry through CavME. By binding to gangliosides located in caveolae, Src tyrosine kinase was activated by NDV, leading to activation of caveolae-associated Cav1 and Dyn2, as well as specific Rho GTPase, RhoA and Cdc42, and downstream effectors, CFN and MLC, orchestrating the endocytic entry of NDV. The endocytosed virus-containing caveolar vesicles were subsequently trafficked to the early endosome, where viral-cell membrane fusion occurs [12]. (B) By binding to glycoproteins, viral-cell membrane fusion occurs at the PM. Src-mediated actin cytoskeletal rearrangement also contributes to the direct fusion of the NDV with the cell PM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses

The chicken macrophage cell line, HD11, was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). Galline embryonic fibroblast cell line, DF-1, was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% FBS. The primary chicken macrophages were prepared and cultured as we previously reported (12). The virulent NDV F48E9 strain was propagated, purified, and labeled with the green fluorescent dye, DiOC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as previously described (12, 23, 82, 83). The 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of the labeled virus in HD11 cells was determined (84).

Reagents and antibodies

The proteases trypsin and chymotrypsin (Sigma, Shanghai, China) were used to disrupt cell surface proteins. Vibrio cholera neuraminidase (Sigma) was used to remove cell surface sialic acids. The Maackia amurensis lectin (MAL) and Sambucus nigra lectin (SNA) (Sigma) were used to preferentially bind to α 2,3-linked and α 2,6-linked sialic acids, respectively. Gangliosides, including monosialoganglioside (GM1) and disialoganglioside (GD1a) (Matreya LLC, Pleasant Gap, PA, USA), the inhibitors, activators, and antibodies, which targeted the cellular component involved in the endocytosis pathway, were used in this study. The detailed information is summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Inhibitors and activators used in this study

| Reagent | Specificity | Supplier | Catalog no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDMP | Lipid metabolic inhibitor | Cayman | 10178 |

| Genistein | Protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Selleck | S1342 |

| Saracatinib | Src inhibitor | Selleck | S1006 |

| Dasatinib | Src inhibitor | Selleck | S1021 |

| YEEI peptide | Src activator | Santa | sc-3052 |

| NSC23766 | Rac1 activation inhibitor | Selleck | S8031 |

| IPA-3 | PAK1 activation inhibitor | MCE | HY-15663 |

| Rhosin | RhoA activation inhibitor | MCE | HY-12646 |

| Y-27632 | ROCK-I inhibitor | MCE | HY-10071 |

| ML-9 | MLCK inhibitor | Selleck | S6847 |

| ML141 | Cdc42 activation inhibitor | MCE | HY-12755 |

| Staurosporine | PAK2 activation inhibitor | MCE | HY-15141 |

| Cytochalasin D | Actin polymerization inhibitor | MCE | HY-N6682 |

| Jasplakinolide | Actin stabilizing reagent | MCE | HY-P0027 |

| Wiskostatin | N-WASP inhibitor | Aladdin Chemical | W169157 |

| CK-636 | Arp2/3 complex inhibitor | MCE | HY-15892 |

TABLE 2.

Antibodies used in this study

| Antibody | Description | Supplier | Catalog no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| GM1 | GM1 Ganglioside antibody | Abcam | ab23943 |

| GD1a | GD1a Ganglioside antibody, clone GD1a-1 | Sigma | MAB5606Z |

| GT1b | GT1b Ganglioside antibody | Sigma | MAB5608 |

| Src | Src (36D10) antibody | CST | 2109 |

| Phospho-Src | Phospho-Src Family (Tyr416) antibody | CST | 2101 |

| Caveolin-1 | Caveolin 1 antibody | Invitrogen | PA5-17447 |

| Dynamin-2 | Dynamin 2 antibody | Santa Cruz | sc-166669 |

| Phospho-Tyrosine | Phospho-Tyrosine antibody (P-Tyr-100) | CST | 9411 |

| Cdc42 | Cdc42 Antibody | Abmart | T55951S |

| ROCK1 | ROCK1 antibody [N1N2], N-term | GeneTex | GTX113266 |

| MLC | Myosin Light Chain 2 antibody | CST | 3672 |

| Phospho-MLC | Phospho-Myosin Light Chain 2 (Ser19) antibody | CST | 3671 |

| Akt | Akt1 (C73H10) antibody | CST | 2938 |

| Phospho-Akt | Phospho-Akt (Ser473) (193H12) antibody | CST | 4058 |

| PAK1 | PAK1 antibody | Abmart | T57148 |

| PAK2 | PAK2 antibody | Abmart | TU397379 |

| Phospho-PAK | Phospho-PAK1/PAK2 (Thr423/Thr402) antibody | Abmart | TA4463 |

| LIMK1/2 | LIMK1/2 antibody | Abmart | PA3256 |

| Phospho-LIMK | Phospho-LIMK1/2 (pT508/505) antibody | Abmart | PA1685 |

| Cofilin | Cofilin antibody | Abmart | PA4598 |

| Phospho-Cofilin | Phospho-Cofilin (Ser3) antibody | Abmart | TA3232 |

| GAPDH | GAPDH antibody | Sigma | G9545 |

| Secondary antibody | Anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (DyLight 680 Conjugate) antibody | CST | 5470 |

| Anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (DyLight 680 Conjugate) antibody | CST | 5366 | |

| Anti-chicken IgY FITC-antibody | Sigma | AP194F | |

| Anti-Rabbit IgG (whole molecule)-TRITC antibody | Sigma | T6778 | |

| Anti-Mouse IgG (whole molecule)-TRITC antibody | Sigma | T7782 | |

| Anti-Rabbit IgG (whole molecule)-FITC antibody | Sigma | F7512 |

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxic effects of inhibitors on HD11 cells were evaluated by a CellTiter 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) as previously described (12). Briefly, HD11 cells cultured in 96-well plates were treated with various concentrations of corresponding reagents for 4 h. The medium was removed, the cells were washed with PBS, and 100 µL serum-free RPMI 1640 medium containing 20 µL CellTiter 96 Aqueous one solution reagent was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Each reagent treated with different concentrations was evaluated in triplicate. The absorbance was determined at 490 nm using a fluorescence microplate. The highest concentration of each reagent with no significant effect on cell viability (> 90%) was used for further study (data not shown).

Plasmid, siRNA, and transfection